Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the quality of communication between hospitals and home health care (HHC) clinicians and patient preparedness to receive HHC in a statewide sample of HHC nurses and staff.

Design

A web-based 48-question cross-sectional survey of HHC nurses and staff in Colorado to describe the quality of communication after hospital discharge and patient preparedness to receive HHC from the perspective of HHC nurses and staff. Questions were on a Likert scale, with optional free-text questions.

Setting and Participants

Between January and June 2017, we sent a web-based survey to individuals from the 56 HHC agencies in the Home Care Association of Colorado that indicated willingness to participate.

Results

We received responses from 50 of 122 individuals (41% individual response rate) representing 14 of 56 HHC agencies (25% agency response rate). Half of respondents were HHC nurses, the remainder were managers, administrators, or quality assurance clinicians.

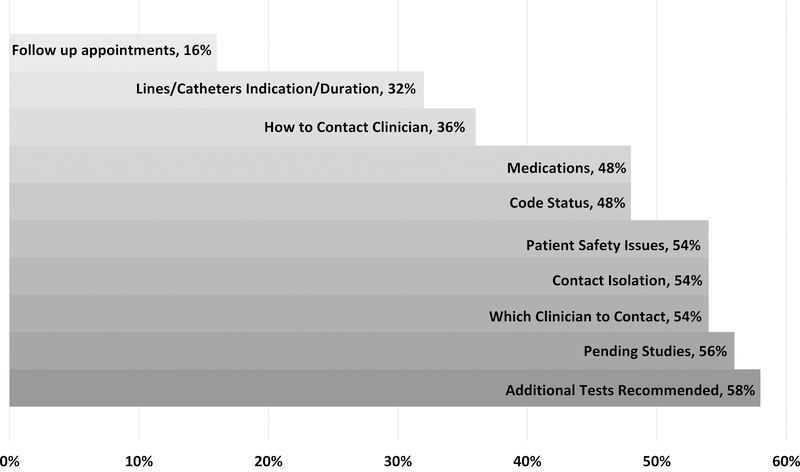

Among respondents, 60% (n=30) reported receiving insufficient information to guide patient management in HHC and 44% (n=22) reported encountering problems related to inadequate patient information. “Additional tests recommended” by hospital clinicians was the communication domain most frequently identified as insufficient (58%).

Over half of respondents (52%) indicated that patient preparation to receive HHC was inadequate with patient expectations frequently including extended-hours caregiving, housekeeping, and transportation, which are beyond the scope of HHC.

Respondents with electronic health record (EHR) access for referring providers were less likely to encounter problems related to a lack of information (27% versus 57% without EHR access, p=0.04). Respondents with EHR access were also more likely to have sufficient information about medications and contact isolation.

Conclusion/Implications

Communication between hospitals and HHC is suboptimal, and patients are often not prepared to receive HHC. Providing EHR access for HHC clinicians is a promising solution to improve the quality of communication.

Keywords: Home Health, Communication, Care Transitions

Introduction

New policies and payment models are encouraging health systems and hospitals to work with post-acute care (PAC) providers to improve patient outcomes after discharge.1–3 However, exchange of clinical information between hospitals and PAC providers, including skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and home health care (HHC) agencies, is frequently inadequate.4–6 In a survey study of SNF clinicians and staff in Missouri, investigators found problematic communication between the hospital and SNF, with information about medications and orders frequently incomplete or missing.6 In a survey study, our group also found that exchange of information between the hospital and SNF setting was not timely or complete, and that information about the hospitalist clinician contact, pending studies, and indication/duration for lines and catheters are often missing.7

In multiple qualitative studies, HHC clinicians have described challenges similar to those encountered in the SNF setting including lack of access to hospital records, incomplete records, challenges connecting with hospital clinicians, and medication list inaccuracies.8–10 The finding that 94–100% of medication lists have at least one discrepancy between referring provider and HHC medication lists has concerning implications for patient safety.11,12 Although providing PAC clinicians with access to referring clinicians’ electronic health records (EHR) has been suggested as a solution to address communication challenges, little is known about how this access influences the timeliness or completeness of communication.

Finally, both patients and hospital-based clinicians may have an incomplete understanding of what PAC services provide, which likely contributes to a mismatch of expectations for HHC.8,10,13,14 Much of the prior work to evaluate communication and preparation during hospital to HHC transitions has been qualitative, and little is known about the experience of HHC clinicians in a broader geographic area. The aims of this study were to (1) evaluate the quality of communication (i.e., timeliness and completeness of information) after hospital discharge, (2) assess perceptions of patient preparedness to receive HHC after discharge, and (3) evaluate the effect of access to referring providers’ EHRs from the perspective of HHC nurses and staff throughout Colorado.

Methods

We completed a cross-sectional survey of HHC nurses and staff at 56 HHC agencies between January and June 2017. HHC agencies were current members of the Home Care Association of Colorado, an association which represents the HHC industry in Colorado. We first emailed leadership for each agency, who identified clinicians and staff potentially willing to participate. Participants were sent a web-based, 48-question survey; sample questions are available in Appendix 1.

Several survey questions were modified from a previously-validated publicly available instrument, the PREPARED survey, which was designed to measure the quality of information transfer from the hospital to community providers.15 Additional questions were modified to the HHC context from a survey our group developed to assess the completeness and timeliness of information provided from the hospital to SNF.7 Specific completeness domains adopted from this prior survey included: medications, lines/catheters, contact isolation, additional tests recommended, pending tests, follow up appointments, occupational/physical therapy needs, code status, and clinician contact (i.e., who and how to contact). An additional completeness domain of patient safety was added because it had been identified as a theme in prior qualitative work with HHC nurses.10 Questions were also developed to assess referring clinician understanding of HHC services, a theme also identified in prior qualitative work.10 Survey questions were validated through semi-structured interviews with 5 HHC nurses.

Survey questions were on a 4-point Likert scale, with optional free text comments following Likert-scale responses. For analysis, we collapsed 4-point Likert responses into dichotomous variables (e.g., sufficient vs. insufficient; timely vs. not timely). Survey responses were de-identified by individual and by agency for analysis. We performed univariate analyses and bivariate analyses (chi-squared) to evaluate the association between HHC agency access to hospital electronic health records (EHRs) and completeness of data using Stata version 12.1 (College Station, TX). A two-sided p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We also completed content analysis of free text data to contextualize responses related to key results. We analyzed free text questions related to completeness of information (questions 2a, 13a), patient preparedness and expectations for HHC services (questions 17a, 19), and access to electronic health record data for hospitals (questions 46c, 47a). Two team members reviewed free text responses for individual questions, developed a code list, applied the codes the text, and developed themes from the codes using Atlas.ti version 7.5.17 (Berlin, Germany). A third team member was involved to resolve any coding discrepancies. This study was reviewed and approved by the Colorado Institutional Review Board (protocol 16–2732).

Results

We received responses from 50 of 122 individuals (41% response rate for individuals) representing 14 of 56 HHC agencies (25% response rate for agencies). Responses were received from agencies in all 5 geographic regions of Colorado. Among the agencies, the number of responses ranged from 1–6 responses per agency with the average number of 3.6 responses/agency. Two of the 50 surveys included in the analysis were partially completed. Characteristics of respondents and HHC agencies are outlined in Table 1. Most of the respondents were non-Hispanic white women age 50 and above. Half of respondents were HHC nurses, the remainder were managers, administrators, and quality assurance clinicians. Most respondents worked at for-profit agencies and nearly half described their agency as stand-alone. Regarding delivery of HHC services, 38% worked in rural areas, 30% in suburban, 24% in urban areas, and 8% in multiple settings. Most respondents (74%) reported that over half of HHC patients cared for in their agency were originally referred after a hospitalization. Although 90% described using an EHR in their clinical practice, fewer than half had access to the EHR for referring hospitals or clinics.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Respondents and Home Health Care Agencies

| Respondent Characteristics | Respondents (n=50) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 20–39 | 9 (18%) |

| 40–49 | 12 (24%) |

| 50–59 | 15 (30%) |

| 60 and above | 14 (28%) |

| Women | 48 (96%) |

| Race, Ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 44 (88%) |

| White, Hispanic | 3 (6%) |

| Other (Asian or more than one race) | 3 (6%) |

| Position | |

| Nurse | 25 (50%) |

| Manager | 16 (32%) |

| Administrator | 7 (14%) |

| Quality Assurance Clinician | 2 (4%) |

| Years working at HHC agency | |

| < 1–5 years | 26 (52%) |

| 5–10 years | 13 (26%) |

| >10 years | 11 (22%) |

| Working at least 40 hours/week at agency | 35 (70%) |

| Agency Characteristics | |

| Agency funding | |

| For-profit | 31 (65%) |

| Non-profit | 13 (27%) |

| Government or Other | 4 (8%) |

| Agency structure | |

| Stand alone | 23 (46%) |

| Part of regional or national chain | 17 (34%) |

| Hospital-affiliated | 8 (16%) |

| Other | 2 (4%) |

| Use EHR at practice | 45 (90%) |

| Access to EHR for referring hospitals or clinics | 22 (44%) |

Timeliness and Completeness of Information from Hospitals

With respect to how promptly respondents received patient information from hospitals, termed “timeliness” of information receipt, 96% (n=48) expressed a preference to receive discharge information either before or at the time of discharge, and 76% (n=38) reported receiving information within this timeframe.

When asked about completeness of information available from hospitals at the time of discharge, 60% (n=30) reported insufficient information to guide patient management for HHC. Additionally, 44% (n=22) reported that they often (34%), or almost always (10%) encounter problems directly related to not having adequate information about a recently-discharged patient. The most frequent insufficient domain was additional tests recommended following discharge (58% of respondents). The proportions of information domains identified as insufficient are shown in Figure 1. Of note, no respondents reported insufficient occupational or physical therapy information. Within free text responses, respondents described additional insufficient information domains including: wound care needs (n=4, 8%), primary care provider knowledge of the hospitalization (n=4, 8%), and medical history details (e.g., ejection fraction for heart failure, n =3, 6%)

Figure 1:

Frequency of Insufficient Information, By Domain Proportion of Respondents Identifying Domains as Insufficient

In addition, 78% (n = 39) of respondents reported that reaching the appropriate clinician with questions was somewhat to extremely difficult. In free text, respondents further described making multiple calls while not receiving timely responses (n=3, 6%), as in the following quote: “I often have to call multiple times. I am often ignored and don’t get calls back from anyone.”

Patient Preparation and Expectations for HHC

When asked how adequately discharging hospitals prepare patients and their families to receive HHC, over half of the HHC respondents (52%, n = 26) indicated that patient preparation was inadequate. Respondents noted that patients had expectations for HHC that were beyond the scope of skilled HHC “occasionally” (38%), “often” (36%), or “almost always” (14%).

In free text, many respondents described encountering expectations for extended-hours caregiving (e.g., multiple hours, daily, overnight, 62%, n = 31). Respondents also described expectations for assistance with housekeeping/cleaning (32%, n = 16), transportation (28%, n = 14), food preparation or grocery shopping (14%, n = 7), more frequent wound care than can be provided (8%, n=4), and help with picking up medications (6%, n=3). One respondent wrote “[Patients/caregivers expect] that we will be there every day for hours at a time and we can stay overnight, seems like some patients and their families are totally clueless what home health provides and it seems like hospital workers and doctors are also clueless what we provide.”

Electronic access to records

Most respondents reported using EHRs at their HHC agency. While almost all (96%) indicated that internet-based access to a patient’s hospital medical record would be at least somewhat useful, fewer than half reported having access to EHRs for referring hospitals or clinics (Table 1). To assess the relationship between access to EHRs for referring providers and timeliness/completeness of information available, we found that HHC nurses with EHR access were more likely to have sufficient information about medications and contact precautions from the hospital than those without EHR access (Table 2). HHC nurses with EHR access were also less likely to encounter problems related to a lack of information from hospitals (27% versus 57% without EHR access, p=0.04). Of interest, EHR access was not associated with difficulty reaching a clinician after discharge; 79% without EHR access and 78% with EHR access had at least some difficulty reaching a clinician (p=0.91).

Table 2:

Sufficiency of information received by home health care, by EHR access for hospitals/clinics

| Sufficient information, by item | No EHR access (n = 28) | EHR access (n = 22) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information to create plan of care | 15 (54%) | 14 (64%) | 0.474 |

| Information to guide management | 9 (32%) | 11 (50%) | 0.201 |

| Timeliness | |||

| Information available at or before time of discharge | 21 (75%) | 17 (77%) | 0.852 |

| Completeness | |||

| Medications | 10 (36%) | 16 (73%) | 0.009* |

| Lines and catheters | 14 (50%) | 13 (59%) | 0.522 |

| Contact precautions | 6 (21%) | 15 (68%) | 0.004* |

| Additional tests recommended | 10 (36%) | 11 (50%) | 0.310 |

| Tests pending at discharge | 9 (32%) | 13 (59%) | 0.057 |

| Follow up appointments recommended | 21 (75%) | 17 (77%) | 0.852 |

| OT/PT | 28 (100%) | 22 (100%) | NA |

| Patient safety issues | 11 (39%) | 12 (55%) | 0.283 |

| Code status | 13 (46%) | 13 (59%) | 0.374 |

| Clinician contact – which clinician | 11 (39%) | 12 (55%) | 0.283 |

| Clinician contact – how to reach | 11 (39%) | 14 (64%) | 0.087 |

Statistically significant

When asked how electronic access to other clinical settings has influenced patient care and what types of information they could access, respondents described accessing specific types of information such as notes, orders, lab and radiology results, and referrals placed (16%, n=8). One respondent wrote that electronic access to the hospital record has been: “Very influential. We often find that the [discharge] planner is not aware of some of the patient issues because they have not read all the information that we have read.” In addition, 6 respondents (12%) favorably described accessing a regional information health exchange, the Colorado Regional Health Information Organization (CORHIO, www.corhio.org), to acquire clinical information. Within free text responses, participants described being able to access CORHIO for information about hospital admissions to any participating hospital. One participant elaborated in free text about CORHIO: “The cost is modest and the access is invaluable.”

Discussion

In this cross-sectional survey of HHC clinicians and staff in Colorado, respondents indicated receiving insufficient information from hospitals to provide optimal transitional care and that reaching clinicians to resolve questions is difficult. In addition, patients are not optimally prepared by the hospital to receive HHC services after discharge, which likely contributes to misalignment between patient expectations and the scope of skilled HHC services. Of interest, access to a referring provider’s EHR was associated with encountering fewer problems related to lack of information from the hospital.

In our study, HHC nurses and staff identified multiple domains of information as insufficient, which is similar to findings from a recent mixed-methods study in which investigators reviewed all information received by HHC nurses at the time of admission to HHC.9 In this study, information about advance directives, next of kin, and patient caregivers were frequently missing. In another recent qualitative study, investigators noted process failures for information during the hospital-to-home transition that included information overload, underload, scatter (i.e., information in multiple places), conflict, and errors.8 In this study, medication discrepancies were noted as one example of information conflict. Notably, additional studies have found extremely high rates of medication discrepancies (94–100%) when referring provider and HHC medication lists are compared.11,12 This is of particular concern because medication errors frequently contribute to hospital readmissions and ED revisits.16,17 The difficulty HHC clinicians report when attempting to communicate with physicians with clinical questions likely contribute to safety issues related to medication errors.

Our findings also suggest that hospitals often do not adequately prepare patients to receive skilled HHC and that patient expectations for HHC often extend beyond what might be covered through their insurance. In a recent qualitative study of older hospitalized adults, Sefcik and colleagues found that older adults desired practical information about post-acute care services and the specific relevance of such services.18 In addition, patients described wanting opportunities to understand their post-acute care options. In a separate study of why patients decline PAC services, one of the reasons cited by older adults was a lack of understanding and preconceived ideas about PAC.14 Patients in this study described wanting information tailored to their personal situation so that they could independently assess how PAC might benefit them.

In order to make informed decisions about PAC including HHC, patients and caregivers must understand what to expect from available services. Lack of patient preparation may reflect a lack of hospital clinician and staff knowledge about the nature and scope of PAC services. Thus, targeted education of hospital clinicians and staff is likely needed.19 In addition to education, PAC decision-support tools may help to appropriately identify, refer, and prepare patients for PAC services, which may improve patient outcomes.20 Finally, hospital-initiated screening of older adults referred for HHC to determine patient-centered non-medical needs including extended caregiving, help with housework, transportation, and food preparation could be informative. Ideally patients screening positive would receive referrals to community organizations to address their non-medical needs.

A novel finding from this survey is that having access to a referring provider’s EHR could decrease problems related to insufficient information and improve access to information about medications and contact isolation. In addition, accessing a regional health information exchange (HIE) was noted to be a valuable way to acquire additional clinical information from all hospitals participating in the exchange. This is an innovative model for accessing information about patient hospital readmissions or ED visits, which frequently occur in a hospital separate from the initial hospitalization.21 Further work to evaluate if rates of medication discrepancies or hospital readmissions could be reduced through EHR/HIE access would be of great interest.

Although access to EHR/HIEs may help to improve communication from hospital to HHC, respondents with EHR access still reported insufficient information across multiple domains. To address this challenge with completeness of information in the EHR, current tools used to reduce acute care hospitalizations in nursing home residents could be adapted to improve hospital to HHC transitions.22

A limitation of this study includes our sampling strategy, in which clinical leadership within agencies identified clinicians and staff who were willing to participate, which may have introduced bias. The total number and characteristics of clinicians and staff who were approached and did not express interest in the survey are unknown. The study was limited to agencies actively participating in a statewide organization in Colorado. Results may not be generalizable beyond this context. However, our sample, which was 96% female is comparable to the national HHC services workforce, which is 89% female.23 In addition, the similarity between themes identified in our prior qualitative study with HHC nurses and results from this statewide survey suggests that deficiencies in timeliness and completeness of information transfer, and patient preparedness for HHC is potentially a widespread problem. Strengths of this study include use of questions from a previously-validated survey, and development of items from a qualitative study with HHC nurses.10

Conclusion

Financial incentives for hospitals and HHC agencies to collaborate towards improving patient outcomes are increasing. For hospitals and HHC agencies seeking strategies to improve communication, this study can provide targets for improvement. Future interventions to improve communication between the hospital and HHC should aim to improve preparation of patients and caregivers to ensure they know what to expect from HHC and to provide access to EHR information for HHC agencies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sponsor’s Role:

• Dr. Jones is supported by grant number K08HS024569 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Funding sources: Dr. Jones is supported by grant number K08HS024569 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report

References

- 1.cms.gov. Home Health Value-Based Purchasing Model. 2016; https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/home-health-value-based-purchasing-model. Accessed February 2, 2018.

- 2.cms.gov. IMPACT Act of 2014 & Cross Setting Measures. 2015. Accessed October 21, 2017.

- 3.CMS.gov. Readmissions Reduction Program. 2016; http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed December 21, 2017, 2016.

- 4.King BJ, Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Roiland RA, Polnaszek BE, Bowers BJ, Kind AJ. The consequences of poor communication during transitions from hospital to skilled nursing facility: a qualitative study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(7):1095–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foust JB, Vuckovic N, Henriquez E. Hospital to home health care transition: patient, caregiver, and clinician perspectives. West J Nurs Res. 2012;34(2):194–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popejoy L, Galambos C, Vogelsmeier A. Hospital to nursing home transition challenges: perceptions of nursing home staff. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014;29(2):103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones CD, Cumbler E, Honigman B, et al. Hospital to Post-Acute Care Facility Transfers: Identifying Targets for Information Exchange Quality Improvement. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(1):70–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arbaje AI, Hughes A, Werner N, et al. Information management goals and process failures during home visits for middle-aged and older adults receiving skilled home healthcare services after hospital discharge: a multisite, qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sockolow P, Wojciechowicz C, Holmberg A, et al. Home Care Admission Information: What Nurses Need and What Nurses Have. A Mixed Methods Study. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2018;250:164–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones CD, Jones J, Richard A, et al. “Connecting the Dots”: A Qualitative Study of Home Health Nurse Perspectives on Coordinating Care for Recently Discharged Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(10):1114–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brody AA, Gibson B, Tresner-Kirsch D, et al. High Prevalence of Medication Discrepancies Between Home Health Referrals and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Home Health Certification and Plan of Care and Their Potential to Affect Safety of Vulnerable Elderly Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):e166–e170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hale J, Neal EB, Myers A, et al. Medication Discrepancies and Associated Risk Factors Identified in Home Health patients. Home Healthc Now. 2015;33(9):493–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke RE, Lawrence E, Ladebue A, et al. How Hospital Clinicians Select Patients for Skilled Nursing Facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(11):2466–2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sefcik JS, Ritter AZ, Flores EJ, et al. Why older adults may decline offers of post-acute care services: A qualitative descriptive study. Geriatr Nurs. 2017;38(3):238–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimmer K, Moss J. The development, validity and application of a new instrument to assess the quality of discharge planning activities from the community perspective. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001;13(2):109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(4):317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sefcik JS, Nock RH, Flores EJ, et al. Patient Preferences for Information on Post-Acute Care Services. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2016:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowles KH, Foust JB, Naylor MD. Hospital discharge referral decision making: a multidisciplinary perspective. Appl Nurs Res. 2003;16(3):134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowles KH, Chittams J, Heil E, et al. Successful electronic implementation of discharge referral decision support has a positive impact on 30- and 60-day readmissions. Res Nurs Health. 2015;38(2):102–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burke RE, Jones CD, Hosokawa P, Glorioso TJ, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Influence of Nonindex Hospital Readmission on Length of Stay and Mortality. Med Care. 2018;56(1):85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouslander JG, Bonner A, Herndon L, Shutes J. The Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) quality improvement program: an overview for medical directors and primary care clinicians in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(3):162–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avalere. Home health chartbook 2015: Prepared for the Alliance for Home Health Quality and Innovation. 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.