Abstract

Background

Novel second-line treatments are needed for patients with advanced urothelial cancer (UC). Interim analysis of the phase III KEYNOTE-045 study showed a superior overall survival (OS) benefit of pembrolizumab, a programmed death 1 inhibitor, versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced UC that progressed on platinum-based chemotherapy. Here we report the long-term safety and efficacy outcomes of KEYNOTE-045.

Patients and methods

Adult patients with histologically/cytologically confirmed UC whose disease progressed after first-line, platinum-containing chemotherapy were enrolled. Patients were randomly assigned 1 : 1 to receive pembrolizumab [200 mg every 3 weeks (Q3W)] or investigator’s choice of paclitaxel (175 mg/m2 Q3W), docetaxel (75 mg/m2 Q3W), or vinflunine (320 mg/m2 Q3W). Primary end points were OS and progression-free survival (PFS) per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1) by blinded independent central radiology review (BICR). A key secondary end point was objective response rate per RECIST v1.1 by BICR.

Results

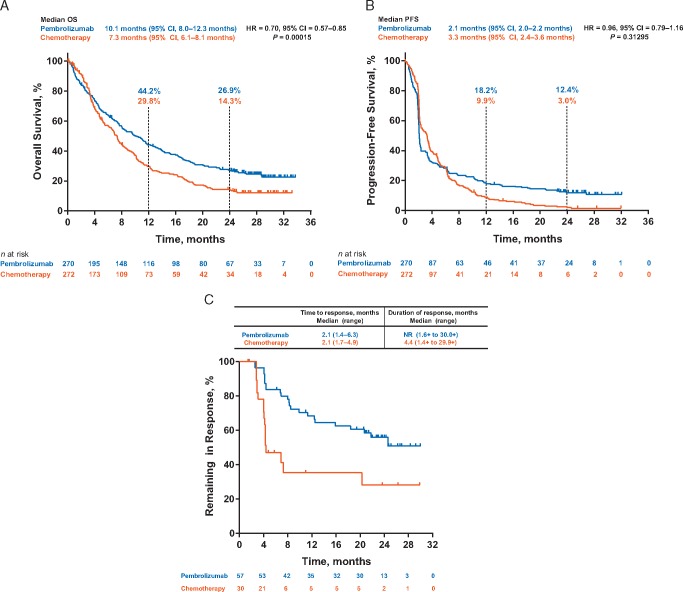

A total of 542 patients were enrolled (pembrolizumab, n = 270; chemotherapy, n = 272). Median follow-up as of 26 October 2017 was 27.7 months. Median 1- and 2-year OS rates were higher with pembrolizumab (44.2% and 26.9%, respectively) than chemotherapy (29.8% and 14.3%, respectively). PFS rates did not differ between treatment arms; however, 1- and 2-year PFS rates were higher with pembrolizumab. The objective response rate was also higher with pembrolizumab (21.1% versus 11.0%). Median duration of response to pembrolizumab was not reached (range 1.6+ to 30.0+ months) versus chemotherapy (4.4 months; range 1.4+ to 29.9+ months). Pembrolizumab had lower rates of any grade (62.0% versus 90.6%) and grade ≥3 (16.5% versus 50.2%) treatment-related adverse events than chemotherapy.

Conclusions

Long-term results (>2 years’ follow-up) were consistent with those of previously reported analyses, demonstrating continued clinical benefit of pembrolizumab over chemotherapy for efficacy and safety for treatment of locally advanced/metastatic, platinum-refractory UC.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02256436.

Keywords: PD-L1, PD-1, pembrolizumab, urothelial cancer

Key Message

The clinical benefit of pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy in advanced, platinum-refractory urothelial cancer is durable. After a median follow-up of 27.7 months, 1- and 2-year overall survival rates were higher with pembrolizumab (44.2% and 26.9%) than with chemotherapy (29.8% and 14.3%). Treatment-related adverse events (any grade and grade ≥3) were lower with pembrolizumab than with chemotherapy.

Introduction

Until recently, only a few chemotherapies were available for second-line treatment of patients with platinum-refractory bladder cancer, leaving an urgent unmet need in this population. Programmed death 1 (PD-1) and its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, have become a focus of cancer research as targets for immunotherapy, culminating in development of monoclonal antibody immune checkpoint inhibitors. Phase I studies with the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab showed clinical antitumor activity in several solid tumor types, including previously treated urothelial cancer (UC) [1, 2]. KEYNOTE-045 (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02256436) is an ongoing, international, randomized, active-controlled, phase III trial of second-line pembrolizumab versus investigator’s choice of docetaxel, paclitaxel, or vinflunine in patients with recurrent advanced UC that has progressed with platinum-based chemotherapy [3]. Significant overall survival (OS) benefit relative to chemotherapy with a concomitant improvement in tumor response and a favorable adverse event (AE) profile were reported at the second interim analysis [3]. This was the first demonstration of survival benefit of any agent over chemotherapy in this patient population and was the basis for expansion of indications for pembrolizumab to include patients with locally advanced or metastatic UC with progressive disease (PD) during or after platinum-containing chemotherapy [4]. Further analysis of patient-reported outcomes measures in KEYNOTE-045 revealed that pembrolizumab significantly prolonged time to deterioration in global health status and health-related quality-of-life score compared with chemotherapy, possibly contributing to the reported cost-effectiveness of this treatment in the USA [5, 6]. Long-term safety and efficacy outcomes of KEYNOTE-045 are reported herein; median follow-up was 27.7 months.

Methods

Study design and patient population

This study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards or ethics committees of all participating sites. All patients provided written informed consent to participate before enrollment.

More detailed methodology is published elsewhere [3]. In brief, adult patients were enrolled with previously treated (two or fewer lines of systemic chemotherapy for advanced disease) UC of the renal pelvis, ureter, bladder, or urethra, with predominantly transitional cell features, that had progressed after first-line, platinum-containing chemotherapy for advanced disease. All patients had at least one measurable lesion according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1) [7] and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) score of 0, 1, or 2.

Treatment and assessments

Patients were randomly assigned (1 : 1) to receive either pembrolizumab 200 mg intravenously (i.v.) every 3 weeks (Q3W) or the investigator’s choice of paclitaxel (175 mg/m2 i.v. Q3W), docetaxel (75 mg/m2 i.v. Q3W), or vinflunine (320 mg/m2 i.v. Q3W). Randomization was stratified according to the ECOG PS score (0 or 1 versus 2), the presence of liver metastases (yes versus no), hemoglobin concentration (<10 versus ≥10 g/dl), and time since the last dose of chemotherapy (<3 versus ≥3 months). Treatment was open-label and continued until PD per RECIST v1.1, unacceptable toxicity, patient or investigator decision to discontinue treatment, or 2 years of pembrolizumab treatment. The original protocol did not allow patient crossover from chemotherapy to pembrolizumab [3]; however, positive findings of the second interim analysis [3] led to amendment of the protocol to allow crossover to pembrolizumab treatment of patients in the chemotherapy arm who experienced investigator-defined PD per RECIST v1.1 while receiving study treatment or who, after stopping study treatment, started subsequent anticancer therapy and then experienced progression.

Tumor response was assessed per RECIST v1.1 by blinded independent central radiology review (BICR) at week 9, every 6 weeks thereafter during the first year, and every 12 weeks thereafter. Patients were contacted every 12 weeks for survival assessment. Full assessment schedules for efficacy and safety are provided elsewhere [3]. All AEs of unknown etiology thought to be associated with pembrolizumab exposure were evaluated to determine whether they were of potentially immunologic etiology [i.e. immune-mediated AEs (imAEs)].

Study end points

Primary end points were OS and progression-free survival (PFS) per RECIST v1.1 by BICR in all patients and in patients with PD-L1-expressing disease according to two thresholds [combined positive score (CPS) ≥1 and CPS ≥10, determined using the PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx assay (Agilent Technologies)]. Secondary end points were safety and tolerability of pembrolizumab, objective response rate, and duration of response (DOR) per RECIST v1.1.

Statistical analysis

Details of statistical analyses are presented elsewhere [3]. The primary efficacy end points were analyzed using data from the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, whereas data from the all-patients-as-treated (APaT) population (all randomly assigned patients who received at least one dose of study treatment) were analyzed for safety data. Median follow-up was calculated as median duration from randomization date to data cut-off date. An exploratory analysis evaluated OS and PFS by best overall response. The data cut-off date was 26 October 2017. Safety and tolerability (assessed by clinical review of AEs, laboratory tests, vital signs, and electrocardiography) were analyzed descriptively.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

Among the ITT population (N = 542), 270 patients received pembrolizumab and 272 received chemotherapy; of those, 266 pembrolizumab and 255 chemotherapy patients composed the APaT (safety) population (N = 521). None of the 255 patients in the chemotherapy arm completed 2 years of therapy; 26 of the 266 (9.8%) pembrolizumab-treated patients completed 2 years of therapy and 240 (90.2%) had discontinued treatment at the time of data cut-off (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). One patient in the chemotherapy arm and 10 patients in the pembrolizumab arm discontinued treatment before 2 years because they achieved complete response (CR). PD was the primary reason for discontinuation of pembrolizumab and chemotherapy (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Baseline characteristics of the patients were similar between the two treatment arms [3] (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Efficacy: overall population

OS and PFS

The median OS was 10.1 months (95% CI 8.0–12.3 months) with pembrolizumab and 7.3 months (95% CI 6.1–8.1 months) with chemotherapy [hazard ratio (HR) 0.70; 95% CI 0.57–0.85; P < 0.001]. After a median follow-up of 27.7 months, the 1-year OS rates were 44.2% and 29.8% and the 2-year OS rates were 26.9% and 14.3% for pembrolizumab and chemotherapy, respectively (Figure 1A). Pembrolizumab continued to demonstrate an OS benefit over chemotherapy in all subgroups examined (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online), including those with visceral disease and liver metastases, and across the different levels of PD-L1 expression (i.e. CPS <1, CPS ≥1, CPS <10, and CPS ≥10) and risk groups. Of patients in the chemotherapy arm still alive at 24 months, including those who received pembrolizumab per protocol crossover (6/33; 18.2%), 60.6% (20/33) received an immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier Estimates. (A) Overall survival. (B) Progression-free survival in all patients (intention-to-treat population) with advanced urothelial carcinoma treated with pembrolizumab (n = 270) or chemotherapy (n = 272). (C) Time to response and median response duration in all patients (intention-to-treat population) who achieved objective response (complete or partial). Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NR, not reached; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

There was no statistically significant difference in PFS between the pembrolizumab and chemotherapy arms (Figure 1B): 2.1 months (95% CI 2.0–2.2 months) versus 3.3 months (95% CI 2.4–3.6 months), respectively (HR 0.96; 95% CI 0.79–1.16; P = 0.31295). However, the 24-month PFS rates were greater in pembrolizumab-treated patients (12.4%) than in chemotherapy-treated patients (3.0%).

Objective response

The objective response rate was higher in the pembrolizumab arm (21.1%) than in the chemotherapy arm (11.0%), as were the rates of CR (9.3% versus 2.9%) and partial response (PR; 11.9% versus 8.1%; Table 1). Results for patients with CPS ≥10 were 20.3% for pembrolizumab and 6.7% for chemotherapy. Rates of stable disease (SD) were lower with pembrolizumab than with chemotherapy (17.4% versus 33.8%). The median DOR was longer with pembrolizumab than with chemotherapy [not reached (NR; range 1.6+ to 30.0+ months) versus 4.4 months (range 1.4+ to 29.9+ months); Figure 1C]. Furthermore, a greater proportion of pembrolizumab-treated patients had responses (CR or PR) lasting ≥6 months [84% (n = 46) versus 47% (n = 8)] and ≥12 months [68% (n = 35) versus 35% (n = 5)].

Table 1.

Best overall response assessed based on RECIST v1.1 by blinded central radiology review

| Best overall response | Pembrolizumab |

Chemotherapy |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 270 |

n = 272 |

|||

| n | % (95% CI)a | n | % (95% CI)a | |

| Objective response rate (CR+PR) | 57 | 21.1 (16.4–26.5) | 30 | 11.0 (7.6–15.4) |

| CR | 25 | 9.3 (6.1–13.4) | 8 | 2.9 (1.3–5.7) |

| PR | 32 | 11.9 (8.2–16.3) | 22 | 8.1 (5.1–12.0) |

| SD | 47 | 17.4 (13.1–22.5) | 92 | 33.8 (28.2–39.8) |

| Disease control rate (CR+PR+SD) | 104 | 38.5 (32.7–44.6) | 122 | 44.9 (38.8–51.0) |

| Progressive disease | 131 | 48.5 (42.4–54.7) | 90 | 33.1 (27.5–39.0) |

| No assessment | 31 | 11.5 (7.9–15.9) | 52 | 19.1 (14.6–24.3) |

| Nonevaluableb | 4 | 1.5 (0.4–3.7) | 8 | 2.9 (1.3–5.7) |

Based on binomial exact CI method.

Patients had postbaseline imaging; best overall response was determined as nonevaluable per RECIST v1.1.

CR, complete response; PR, partial response; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; SD, stable disease.

OS and PFS by objective response

An exploratory analysis evaluating OS by objective response showed that OS was prolonged among patients with CR or PR to pembrolizumab compared with those who responded to chemotherapy (supplementary Figure S3A, available at Annals of Oncology online). Among patients with an objective response, median OS was NR for pembrolizumab-treated patients and 16.4 months for chemotherapy-treated patients at data cut-off (supplementary Figure S3A, available at Annals of Oncology online). Among patients with SD as best response, median OS was greater with pembrolizumab than with chemotherapy (supplementary Figure S3B, available at Annals of Oncology online). The difference in the median OS of patients with PD as best response did not seem meaningful between the arms (supplementary Figure S3C, available at Annals of Oncology online). Additionally, PFS (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online) was longer for those with an objective response to pembrolizumab than for those who responded to chemotherapy. No differences were observed in PFS between treatment arms for those with SD or no response.

Safety

Treatment-related AEs occurred less frequently among patients receiving pembrolizumab (62.0%) than among those receiving chemotherapy (90.6%). The most common (>15% of patients) were pruritus for the pembrolizumab arm and alopecia, fatigue, anemia, nausea, constipation, decreased appetite, and neutropenia for the chemotherapy arm (Table 2). Treatment-related serious AEs (SAEs) were reported by 32 (12.0%) patients treated with pembrolizumab and 57 (22.4%) treated with chemotherapy. None of the treatment-related SAEs in the pembrolizumab arm occurred with a frequency of >2%; the most frequently occurring (in >1% of patients) were colitis (1.9%), pneumonitis (1.9%), and interstitial lung disease (1.1%). The most frequently occurring treatment-related SAEs in the chemotherapy arm were febrile neutropenia (6.3%), constipation (2.7%), anemia (2.0%), intestinal obstruction (2.0%), neutropenia (2.0%), and urinary tract infection (1.6%) (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). When evaluated by duration of exposure to treatment (up to 12 months), patients in the chemotherapy group had a higher incidence of any grade and grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs than patients in the pembrolizumab group (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 2.

Treatment-related AEs of any grade and grade 3–5 occurring in >5% of patients (in either treatment arm): all-patients-as-treated population

| Treatment-related AEs, n (%) | Pembrolizumab |

Chemotherapy |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 266 |

n = 255 |

|||

| Any grade | Grade 3–5a | Any grade | Grade 3–5a,b | |

| Any | 165 (62.0) | 44 (16.5) | 231 (90.6) | 128 (50.2) |

| Pruritus | 52 (19.5) | 8 (3.1) | ||

| Fatigue | 37 (13.9) | 71 (27.8) | ||

| Nausea | 30 (11.3) | 62 (24.3) | ||

| Decreased appetite | 25 (9.4) | 43 (16.9) | ||

| Diarrhea | 24 (9.0) | 33 (12.9) | ||

| Rash | 23 (8.6) | 10 (3.9) | ||

| Hypothyroidism | 19 (7.1) | 0 | ||

| Asthenia | 17 (6.4) | 36 (14.1) | ||

| Pyrexia | 17 (6.4) | 9 (3.5) | ||

| Vomiting | 12 (4.5) | 25 (9.8) | ||

| Arthralgia | 9 (3.4) | 17 (6.7) | ||

| Anemia | 8 (3.0) | 2 (0.8) | 64 (25.1) | 24 (9.4) |

| Constipation | 7 (2.6) | 52 (20.4) | ||

| Stomatitis | 5 (1.9) | 21 (8.2) | ||

| Mucosal inflammation | 4 (1.5) | 17 (6.7) | ||

| Dysgeusia | 3 (1.1) | 14 (5.5) | ||

| Pain in extremity | 3 (1.1) | 13 (5.1) | ||

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 2 (0.8) | 28 (11.0) | ||

| Neutrophil count decreased | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 37 (14.5) | 31 (12.2) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 1 (0.4) | 27 (10.6) | ||

| Edema peripheral | 1 (0.4) | 19 (7.5) | ||

| Leukocyte count decreased | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 19 (7.5) | 13 (5.1) |

| Neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 40 (15.7) | 35 (13.7) |

| Alopecia | 0 | 96 (37.6) | ||

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 19 (7.5) | 19 (7.5) |

Cells are left blank if the frequency of occurrence was <5% in both treatment arms.

There was just one grade 5 event (pneumonitis), which occurred in the pembrolizumab arm (0.4%).

AE, adverse event.

Fewer patients receiving pembrolizumab (6.8%, n = 18) than patients receiving chemotherapy (12.5%, n = 32) discontinued study treatment because of a treatment-related AE. These events were most commonly pneumonitis (1.9%, n = 5) and interstitial lung disease (0.8%, n = 2) with pembrolizumab and peripheral sensory neuropathy (2.0%, n = 5) and peripheral neuropathy (1.6%, n = 4) with chemotherapy.

Immune-mediated AEs were reported by 52 (19.5%) and 17 (6.7%) patients in the pembrolizumab and chemotherapy arms, respectively, and most were grade 1 or 2 for both treatment arms (69.2% and 88.2%, respectively). One grade 5 imAE, pneumonitis, was considered treatment related and resulted in the death of a patient in the pembrolizumab arm. Study discontinuation because of imAEs occurred in nine (3.4%) patients in the pembrolizumab arm and two (0.8%) patients in the chemotherapy arm. Treatment-related serious imAEs occurred in 16 (6.0%) patients in the pembrolizumab arm and resulted in treatment discontinuation in 7 (2.6%) patients; no treatment-related serious imAEs occurred in the chemotherapy arm. Median time to onset of the first imAE was longer with pembrolizumab than with chemotherapy [105 days (range 1–647 days) versus 21 days (range 1–70 days)], and the average number of imAE episodes per patient was similar between the treatment arms (1.48 versus 1.29). Four patients in each treatment arm (<2%) died of what were considered treatment-related AEs: pneumonitis, urinary tract obstruction, malignant neoplasm progression, and cause unknown (n = 1 each) with pembrolizumab and septic shock (n = 1), sepsis (n = 2), and cause unknown (n = 1) with chemotherapy.

Discussion

Until recently, the only approved chemotherapeutic agents available as second-line therapy were vinflunine, which is associated with very limited clinical benefit and severe side-effects, and gemcitabine and taxane, the use of which is supported by consensus guidelines [8–11]. Although advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors has improved the outlook for this patient population, pembrolizumab is the only one for which there is level 1 evidence from the KEYNOTE-045 study of improved survival, safety, and quality-of-life compared with chemotherapy [12]. Findings of the current analysis show continued OS benefit and superior safety of pembrolizumab over chemotherapy in second-line UC after >2 years of follow-up. The 24-month OS rate for the pembrolizumab arm was 26.9%. Of note, 60.6% of patients in the chemotherapy arm alive at 24 months received a checkpoint inhibitor, which might account for the 24-month OS rate of 14.3% and flattening of the Kaplan–Meier curve for that arm, which historically has not been observed with chemotherapy (Figure 1A). Tumor response is greater with pembrolizumab than with chemotherapy (objective response rate, 21.1% versus 11.0%). Remarkably, after this extended follow-up, median DOR was still not yet reached with pembrolizumab and was just 4.4 months with chemotherapy.

To date, KEYNOTE-045 is the only phase III study of immunotherapy that has more than 2 years of follow-up data to show a survival benefit over chemotherapy. Analyses of other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have provided follow-up of >2 years; however, they have been limited to phase I/II studies [13–15]. Atezolizumab (PD-L1 inhibitor) monotherapy initially showed promising efficacy in an expansion cohort of a phase I study of predominantly heavily pretreated patients with metastatic UC (median follow-up, 37.8 months) [15] and in the phase II IMvigor210 trial (median follow-up, 29–33 months) [14]. However, these results were not confirmed in the phase III IMvigor211 study in which atezolizumab did not show a statistically significant difference in OS compared with chemotherapy (11.1 versus 10.6; HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.63–1.21; P = 0.41) after a median follow-up of 17.3 months [15]. Nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) monotherapy also showed promising efficacy after a follow-up of >2 years in the phase I/II CheckMate-032 study [13]; however, these results have not yet been confirmed in a phase III trial. In the KEYNOTE-045 study, OS benefit with pembrolizumab was seen consistently across all subgroups, including in patients with liver or visceral metastasis, all PD-L1 expression levels (i.e. CPS <1, CPS ≥1, CPS <10, and CPS ≥10), all chemotherapies (paclitaxel, docetaxel, and vinflunine), and all across risk groups (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). OS in patients with CPS ≥10 was significantly longer with pembrolizumab than with chemotherapy (8.0 versus 4.9 months; P = 0.00122), and DOR was comparable with that in the ITT population (NR versus 4.4 months for both populations).

Role of PD-L1 expression as second-line therapy for UC is uncertain. Direct comparison between these PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors is precluded by use of different assays to establish PD-L1 positivity [3, 15–17]. PD-L1 expression seemed to predict a greater response to nivolumab and to durvalumab in single-arm phase I/II studies [16, 17]. PD-L1 enrichment reported for atezolizumab in this indication was confirmed in a phase I study [15] but was not confirmed in the subsequent phase III IMvigor211 study [18]. Superior objective response rate was observed with pembrolizumab over chemotherapy in patients whose tumors expressed PD-L1 CPS ≥10 (20.3% versus 6.7%) and was similar to that in the overall ITT population. Findings of the KEYNOTE-045 study have shown that, although tumor response in terms of objective response rate was similar across all PD-L1 subgroups treated with pembrolizumab, response rates were higher than was achieved with chemotherapy. Additional studies comparing pembrolizumab monotherapy, chemotherapy, and combination treatment with pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy should elucidate the role of PD-L1 expression in bladder cancer.

Consistent with data from previous pembrolizumab studies, pembrolizumab was well tolerated in patients with advanced UC and had a more favorable tolerability profile than chemotherapy. Treatment-related AEs were more frequent with chemotherapy (90.6%) than with pembrolizumab (62.0%). Most frequently observed treatment-related AEs with pembrolizumab in the current trial occurred in <20% of patients, whereas many of those observed with chemotherapy occurred in >20% of patients. Treatment-related SAEs also occurred more frequently with chemotherapy (22.4%) than with pembrolizumab (12.0%). The discontinuation rate from treatment-related AEs in the chemotherapy arm (12.5%) was almost double that in the pembrolizumab arm (6.8%).

With >2 years of follow-up, pembrolizumab continues to demonstrate superior survival over chemotherapy in patients with advanced UC after failure of platinum-based therapy, irrespective of PD-L1 status. These data are consistent with those underlying approval of pembrolizumab in this patient population by health authorities in >60 countries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families and all investigators and site personnel. Medical writing and/or editorial assistance was provided by Jacqueline Kolston, PhD, and Matthew Grzywacz, PhD, of the ApotheCom pembrolizumab team (Yardley, PA, USA). This assistance was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Data sharing statement: Merck & Co., Inc.’s data sharing policy, including restrictions, is available at http://engagezone.msd.com/ds_documentation.php. Requests for access to the clinical study data can be submitted through the EngageZone site or via email to dataaccess@merck.com.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA representatives and academic advisors designed the study. Authors and sponsor representatives analyzed and interpreted the data. An external data monitoring committee monitored the interim data and made recommendations to the executive oversight committee about the overall risk and benefit to trial participants. Authors and representatives of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA, analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors had access to the data (no grant numbers apply).

Disclosure

YF has been a consultant/advisor for Merck, Astellas Pharma, Roche, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Sanofi; has received travel expenses from Roche and Sanofi; and has received research funding from Astellas Pharma. JB has been a consultant/advisor for Pierre Fabre, Astellas Pharma, Pfizer, Merck, Genentech, Novartis, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Bristol-Myers Squibb; has received travel expenses from Pfizer, MSD Oncology; and has received research funding (institution) from Millennium and Sanofi. DJV has received research funding for clinical trials from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche/Genentech, Astellas and has been a consultant/advisor for Merck. JLL has been a consultant/advisor for Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Eisai; has received honoraria from Pfizer, Astellas Pharma, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb; has received research funding from Pfizer, Janssen, Novartis, Exelixis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche/Genentech. LF has been a consultant/advisor for Atreca, IDEAYA Biosciences, MIODx; has received research funding (institution) from Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Roche/Genentech, Janssen Oncology, Merck, Nektar. NJV has been an employee of US Oncology; has been a consultant/advisor for Amgen, Pfizer, Bayer, Genentech/Roche, HERON, AstraZeneca, Caris Life Sciences, Fujifilm, Tolero Pharmaceuticals; has served on a speakers' bureau for Bayer, Sanofi, Genentech/Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Exelixis, AstraZeneca/MedImmune; has received travel, accommodations, expenses from Genentech/Roche, US Oncology, Pfizer, Bayer/Onyx, Exelixis, AstraZeneca/MedImmune; has stock and other ownership interests in Caris Life Sciences; has received honoraria from UpToDate, Pfizer; has received research funding (institution) from US Oncology, Endocyte, Merck, Kintor. MAC has received honoraria from Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer, Astellas Pharma, Sanofi, Pfizer, Novartis; has been a consultant/advisor for Janssen, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Astellas Pharma, Bayer; has received travel, accommodations, expenses from Astellas Pharma, Janssen, Pfizer. DPP has been a consultant/advisor for Bayer, Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, Dendreon, Johnson & Johnson, Exelixis, Ferring, Millennium, Medivation, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Tyme Pharmaceuticals; has provided expert testimony for Celgene, Sanofi; owns stock and other ownership interests in Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, Tyme, Inc.; has received research funding from Oncogenex, Progenics, Johnson & Johnson, Dendreon, Sanofi, Endocyte, Genentech, Merck, Astellas, Medivation, Novartis, Agensys, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Lilly, Innocrin Pharma, MedImmune, Millennium, Pfizer, Roche, Sotio, Seattle Genetics. TKC has received honoraria from and has been a consultant/advisor for AstraZeneca, Alexion, Sanofi/Aventis, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cerulean, Eisai, Foundation Medicine Inc., Exelixis, Genentech, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Peloton, Pfizer, Prometheus Labs, Corvus, Ipsen, UpToDate, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Analysis Group, Michael J. Hennessy (MJH) Associates, Inc. (Healthcare Communications Company with several brands such as OnClive and PER), L-path, Kidney Cancer Journal, Clinical Care Options, Platform Q, Navinata Healthcare, Harborside Press, American Society of Medical Oncology (ASCO), New England Journal of Medicine, Lancet Oncology; has received research funding (institutional and personal) from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cerulean, Eisai, Foundation Medicine, Inc., Exelixis, Ipsen, Tracon, Genentech, Roche, Roche Products Limited, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Peloton, Pfizer, Prometheus Labs, Corvus, Calithera, Analysis Group, Takeda; has served on a speakers’ bureau, has stock, has been employed by, has given expert testimony for NCI GU Steering Committee (unpaid); has been past chairman of Medical and Scientific Steering Committee at the Kidney Cancer Association (unpaid); has received travel, accommodations, expenses in relation to honoraria, consulting, and advisory boards and follows the outside entities guidelines for reimbursement. AN has no conflicts to disclose. WG has been a consultant/advisor for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Aglaia BioMedical Ventures, Astellas Pharma, Bayer, Janssen-Cilag; has received research funding from Astellas Pharma, Bayer, Janssen-Cilag; has received travel, accommodations, expenses from Amgen, Bayer. HG has been a consultant/advisor for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ipsen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, AstraZeneca; has received travel, accommodations, expenses from Astellas Pharma, Sanofi; has received honoraria from Roche, Astellas Pharma; has received research funding (institution) from Pfizer. DIQ has been a consultant/advisor for Astellas Pharma, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Piramal Life Science, Bayer, Exelixis, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Dendreon, Peloton Therapeutics, EMD Serono; has received honoraria from Bayer, Astellas Pharma, Pfizer, Genentech/Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Merck Serono, Piramal Life Science, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Dendreon, Exelixis, Peloton Therapeutics, Sanofi, EMD Serono; has received research funding (institution) from Millennium, Genentech/Roche, Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline. SC has been a consultant/advisor for Roche, Janssen; has received research funding from Astellas Pharma, Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme; has received travel, accommodations, expenses from Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Janssen. CNS has been a consultant for Merck, Clovis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Incyte, AstraZeneca; has received research funding (institution) from Janssen. KN, TLF, and RFP are employees and stockholders of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. RdW has been a consultant/advisor for Sanofi, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Lilly, Roche/Genentech; has received honoraria from Sanofi, Lilly, Roche/Genentech, Merck Sharp & Dohme; has received research funding (institution) from Sanofi. DFB has been a consultant/advisor for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Roche/Genentech, Merck, Genentech, Roche, Lilly, Fidia Farmaceutici S. p. A., Eisai, Urogen Pharma, Pfizer, EMD Serono; has received travel, accommodations, expenses from Roche/Genentech, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lilly, Urogen Pharma; has received honoraria from Merck Sharp & Dohme; has received research funding (institution) from Dendreon, Novartis, Amgen, Genentech/Roche, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb.

References

- 1. Seiwert TY, Burtness B, Mehra R. et al. Safety and clinical activity of pembrolizumab for treatment of recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-012): an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17(7): 956–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Plimack ER, Bellmunt J, Gupta S. et al. Safety and activity of pembrolizumab in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer (KEYNOTE-012): a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18(2): 212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ. et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(11): 1015–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.KEYTRUDA®(Pembrolizumab) for Injection, for Intravenous Use [prescribing information]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vaughn DJ, Bellmunt J, Fradet Y. et al. Health-related quality-of-life analysis from KEYNOTE-045: a phase III study of pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously treated advanced urothelial cancer. JCO 2018; 36(16): 1579–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sarfaty M, Hall PS, Chan KKW. et al. Cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab in second-line advanced bladder cancer. Eur Urol 2018; 74(1): 57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009; 45(2): 228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Witjes JA, Lebret T, Comperat EM. et al. Updated 2016 EAU guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. Eur Urol 2017; 71: 462–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Resch I, Shariat SF, Gust KM.. PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors after platinum-based chemotherapy or in first-line therapy in cisplatin-ineligible patients: dramatic improvement of prognosis and overall survival after decades of hopelessness in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer. Memo 2018; 11(1): 43–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bellmunt J, Orsola A, Leow JJ. et al. Bladder cancer: ESMO practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2014; 25(Suppl 3): iii40–iii48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Houédé N, Locker G, Lucas C. et al. Epicure: a European epidemiological study of patients with an advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (UC) having progressed to a platinum-based chemotherapy. BMC Cancer 2016; 16(1): 752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines): bladder cancer (Version 3.2019), 23 April 2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bladder.pdf (25 April 2019, date last accessed).

- 13. Sharma P, Callahan MK, Bono P. et al. Nivolumab monotherapy in recurrent metastatic urothelial carcinoma (CheckMate 032): a multicentre, open-label, two-stage, multi-arm, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17(11): 1590–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Balar AV, Dreicer R, Loriot Y. et al. Atezolizumab (atezo) in first-line cisplatin-ineligible or platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer (mUC): long-term efficacy from phase 2 study IMvigor210. JCO 2018; 36(Suppl 15): 4523. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Petrylak DP, Powles T, Bellmunt J. et al. Atezolizumab (MPDL3280A) monotherapy for patients with metastatic urothelial cancer: long-term outcomes from a phase 1 study. JAMA Oncol 2018; 4(4): 537–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sharma P, Retz M, Siefker-Radtke A. et al. Nivolumab in metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum therapy (CheckMate 275): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18(3): 312–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Powles T, O'Donnell PH, Massard C. et al. Efficacy and safety of durvalumab in locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma updated results from a phase 1/2 open-label study. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(9): e172411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Powles T, Duran I, van der Heijden MS. et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor211): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 391(10122): 748–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.