Abstract

Background

Dynamic changes in circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) levels may predict long-term outcome. We utilised samples from a phase I/II randomised trial (BEECH) to assess ctDNA dynamics as a surrogate for progression-free survival (PFS) and early predictor of drug efficacy.

Patients and methods

Patients with estrogen receptor-positive advanced metastatic breast cancer (ER+ mBC) in the BEECH study, paclitaxel plus placebo versus paclitaxel plus AKT inhibitor capivasertib, had plasma samples collected for ctDNA analysis at baseline and at multiple time points in the development cohort (safety run-in, part A) and validation cohort (randomised, part B). Baseline sample ctDNA sequencing identified mutations for longitudinal analysis and mutation-specific digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) assays were utilised to assess change in ctDNA abundance (allele fraction) between baseline and 872 on-treatment samples. Primary objective was to assess whether early suppression of ctDNA, based on pre-defined criteria from the development cohort, independently predicted outcome in the validation cohort.

Results

In the development cohort, suppression of ctDNA was apparent after 8 days of treatment (P = 0.014), with cycle 2 day 1 (4 weeks) identified as the optimal time point to predict PFS from early ctDNA dynamics. In the validation cohort, median PFS was 11.1 months in patients with suppressed ctDNA at 4 weeks and 6.4 months in patients with high ctDNA (hazard ratio = 0.20, 95% confidence interval 0.083–0.50, P < 0.0001). There was no difference in the level of ctDNA suppression between patients randomised to capivasertib or placebo overall (P = 0.904) nor in the PIK3CA mutant subpopulation (P = 0.071). Clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) was evident in 30% (18/59) baseline samples, although CHIP had no effect on tolerance of chemotherapy nor on PFS.

Conclusion

Early on-treatment ctDNA dynamics are a surrogate for PFS. Dynamic ctDNA assessment has the potential to substantially enhance early drug development.

Clinical registration number

Keywords: breast cancer, circulating tumour DNA, capivasertib, BEECH trial

Key Message

Our prospective study demonstrated that early circulating tumour DNA dynamics predict progression-free survival with high accuracy in an independent validation series of metastatic breast cancer (mBC) patients on paclitaxel with or without capivasertib. We show early dynamics anticipated the outcome of the randomised study, correctly refuting the hypothesis that PIK3CA mutant ER+ mBC would have higher sensitivity to capivasertib in combination with Paclitaxel.

Introduction

Dynamic changes in the level of circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) early on treatment have the potential to act as a surrogate for treatment response across multiple tumour types [1–3]. The level of ctDNA is principally a function of two factors, tumour bulk and tumour cell turnover [4–8], which results in the level of ctDNA falling rapidly in tumours responding to treatment. Prior research has shown that early changes in ctDNA levels may predict response and progression-free survival (PFS) [9–11], including targeted therapies encompassing CDK4/6 inhibitors [12], human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-targeted therapies [13], and chemotherapy [14]. The assessment of early ctDNA dynamics is to potentially identify, before radiographic change in tumour size, which cancers are not responding adequately to therapy and allow adaption of treatment to avoid symptomatic progression [15–17]. Dynamic assessment may also facilitate early drug development, providing an early assessment of drug efficacy and identification of biomarkers of response [7, 18, 19].

Predicting the outcome of therapy early would allow adaptive changes to treatment to improve outcome. Prior work using circulating tumour cells (CTC) counts, applying a fixed cut-off [20], failed to identify a patient population who would benefit from a change in chemotherapy [21]. Interrogating ctDNA gives substantially greater dynamic range and sensitivity than CTC enumeration [1] allowing more exact definition of which patients are resistant to therapy, in part allowing comparison of on-treatment levels with baseline to allow for the substantial variation in baseline ctDNA levels.

Here, we assessed the potential of dynamic ctDNA change in a randomised placebo-controlled phase II study. In the development cohort, we identified the optimal early time-point and cut-off to predict PFS on the first-line paclitaxel chemotherapy given in combination with the AKT inhibitor capivasertib (AZD5363). We subsequently validated these criteria in the randomised part of the study, demonstrating that early ctDNA dynamics was a strong surrogate for PFS and that early ctDNA change analysis predicted there was no difference between the treatment arms reported by Turner et al. [22].

Materials and methods

Study design

The BEECH study (NCT01625286) was a phase I/II trial consisting of part A, a safety run in of capivasertib in combination with paclitaxel in women with advanced or metastatic breast cancer and part B, a randomised double-blind phase II study of capivasertib or placebo in combination with paclitaxel in women with advanced or metastatic ER+/HER2- breast cancer receiving chemotherapy for the first time in the metastatic setting. Maintenance endocrine therapy was not allowed. Treatment regimens are reported in the related article by Turner et al. [22]. Patients were allocated to the PIK3CA+ stratum if a mutation was identified either in tissue or ctDNA by the cobas®PIK3CA mutation test (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland, Basel, Switzerland).

Sample collection + processing

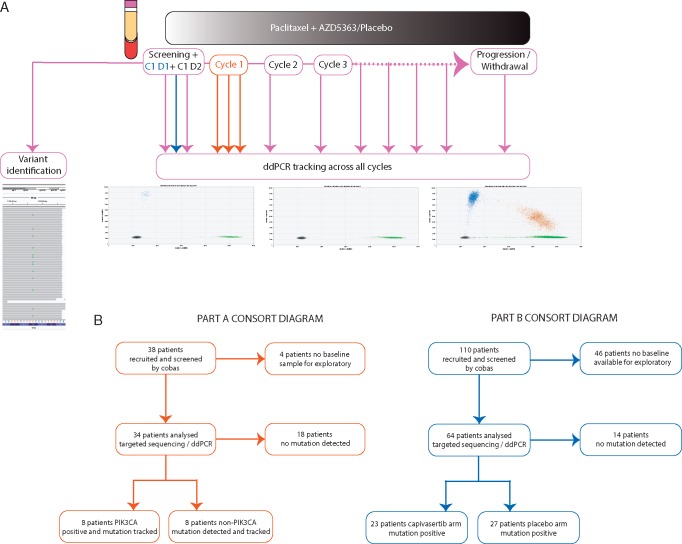

Five millilitre blood was collected for exploratory ctDNA analysis at designated timepoints throughout the study (Figure 1). Plasma was separated within 2 hours of venesection and stored at −80°C. Extracted DNA was quantified by digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) using a Taqman copy number reference assay for RNAse P (Thermo Scientific, UK) as described previously [17] and stored at −20°C before analysis.

Figure 1.

Overview of BEECH study exploratory analysis. (A) Schema of plasma collection during the BEECH trial for both development part A and validation part B cohorts. Red arrows indicate part A sampling only, blue part B sampling only and purple part A and B shared timepoint sampling. Tracking samples were collected on day 1 of each treatment cycle. (B) CONSORT diagrams of part A and part B exploratory plasma baseline analysis.

Baseline plasma mutation identification

Baseline samples [screening and/or cycle 1 day 1 (C1 D1) and/or cycle 1 day 2 (C1 D2)] from patients who consented to ctDNA analysis was subject to sequencing for mutations to subsequently track in plasma samples on treatment. Sequencing also validated PIK3CA mutations identified by the cobas®PIK3CA mutation test with high agreement (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Full sequencing methodology available in supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online along with the targeted panel details for part A (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online) and the targeted capture panel details for part B (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Personalised digital PCR assay design and tracking

From baseline ctDNA sequencing, we identified likely somatic driver mutations and designed primers and probes for digital PCR analysis. Full assay design details (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online) and digital PCR methods available in supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Circulating tumour DNA ratio analysis

For on-treatment digital PCR, the circulating tumour DNA ratio (CDR). Between on-treatment mutation fraction and baseline/screening mutation allele fraction was calculated for all timepoints. In part A, the optimal time-point to predict PFS within the first 4 weeks of treatment was established (supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology).

The primary analysis of the study was, in the independent part B validation cohort, to compare PFS between patients with CDR28 (CDR at cycle 2 day 1, 28 days on treatment identified in part A) greater than the cut-off identified in part A (high ctDNA) and those with CDR28 lower than the cut-off (suppressed ctDNA). Analysis was conducted by Kaplan–Meier survival, with median comparison using the log rank test and hazard ratios from Cox proportional hazards model. Additional secondary analyses were to compare CDR28 between treatment arms, overall and in the PIK3CA mutant sub-population, with Mann–Whitney U test.

Lead-time on on-treatment ctDNA tracking

We established a ‘rise from nadir’ criteria to assess lead time by ctDNA from on-treatment tracking in patients who had initial ctDNA suppression. Patients defined as CDR28 high were determined to have a lead time from day 28 as they did not experience ctDNA suppression. A ‘rise towards baseline’ criteria was also devised. Full details for both criteria are available in supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology.

Results

Development of criteria for early assessment of response

To develop criteria for the early dynamic ctDNA assessment, we intensively sampled 16 patients during the first 4 weeks of therapy on paclitaxel and capivasertib in part A of the BEECH trial (Figure 1). Suppression of ctDNA in patients with long PFS became apparent after only 8 days of treatment (Figure 2A), and C2D1 was identified as the optimal time-point for ctDNA change to discriminate patients with a long versus short PFS (Figure 2A). In the part A development cohort, using a CDR threshold of 0.25 (established in Methods), the patients with a CDR <0.25 had a substantially improved PFS compared with those without suppressed ctDNA (Figure 2B, P = 0.0003 log rank test). Tracking mutations through sequential samples, in patients with ctDNA suppression, at the start of each cycle demonstrated further falls to a nadir that was frequently undetectable, before a rise with lead-time over clinical progression (Figure 2C). Conversely, in patients without ctDNA suppression, ctDNA remains high across the tracking samples before clinical progression, which occurred before the 12-week scan (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Identification of optimal circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) early timepoint for prediction of progression-free survival (PFS) length in the development cohort. (A) Circulating tumour DNA ratios (CDRs) at designated timepoints in the first 4 weeks of study treatment, separated by short and long PFS in study part A. Differing numbers in the long and short groups reflect missed sample collection timepoints in some patients. Long and short PFS was determined by a scan at 12 weeks on study, the time-point of the first scan in part A. C2D1 (CDR28) was the strongest predictive timepoint P = 0.0007, P value Mann–Whitney U test. (B) PFS for development part A patients split by CDR28 suppressed (CDR28<0.25) versus CDR28 high. P value log rank test. (C) Longitudinal tracking of a PIK3CA c.1624G>A (p.E542K) mutation in a patient classified as a long PFS by ctDNA demonstrating successful suppression of ctDNA before rise before progression. (D) Longitudinal tracking of a TP53 c.815T>C (p.V272A) mutation in a patient classified as a short PFS by ctDNA demonstrating failure to suppress ctDNA in the first 4 weeks of treatment.

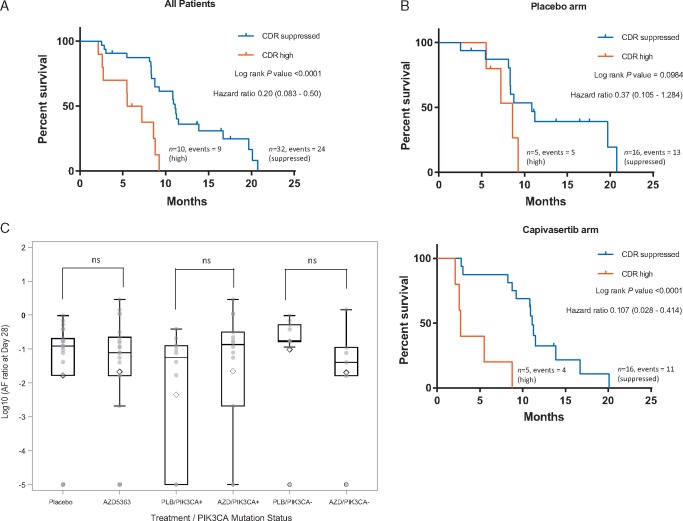

Validation of ctDNA ratio to predict PFS

We independently validated early prediction of outcome from ctDNA dynamics, in the randomised part B of the BEECH study in 42 patients. Samples for ctDNA analysis were taken at screening and at C2D1, identified in part A as the optimal time point for early response assessment using ctDNA (CDR28). Mutation-specific ddPCR had excellent correlation with AZ300 panel allele fractions for mutations identified by sequencing (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology). In the independent validation cohort, patients with a suppressed CDR28 had a median PFS 11.1 months and patients with a high CDR28 has a median PFS 6.4 months (hazard ratio = 0.20, 95% confidence interval 0.083–0.50, P < 0.0001, log rank test, Figure 3A). We separately investigated patients randomised to paclitaxel and placebo, and paclitaxel and capivasertib, with no evident difference in prediction of PFS between both groups (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Early ctDNA dynamics are a surrogate for progression-free survival (PFS) in the independent validation cohort. (A) PFS for validation cohort part B split by CDR28 suppressed (CDR28<0.25) versus CDR28 high. P value log rank test. (B) PFS for high versus suppressed CDR28, stratified for placebo (top) and capivasertib (bottom) treatment arms. (C) Box plot of CDR28 by treatment arm for all patients and CDR28 for treatment arms subdivided by PIK3CA mutation status. Patients with undetectable ctDNA at C2 D1 were assigned an arbitrary low value for statistical analysis. P value from Mann–Whitney U test, not significant across the groups.

Early ctDNA change predicted outcome of treatment randomisation

We next assessed the effect of capivasertib on CDR28, and the interaction with PIK3CA mutation status. Overall there was no difference in ctDNA suppression CDR28 between patients randomised to capivasertib and placebo, in the overall population (median CDR28 0.08 versus 0.12 respectively, P = 0.904), nor in the PIK3CA mutant sub-population (CDR28 0.14 versus 0.06 respectively, P = 0.071) (Figure 3C, supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). Similarly, there was no difference in PFS between patients randomised to capivasertib and placebo, overall and in the PIK3CA mutant subpopulation (reported in the related article by Turner et al.).

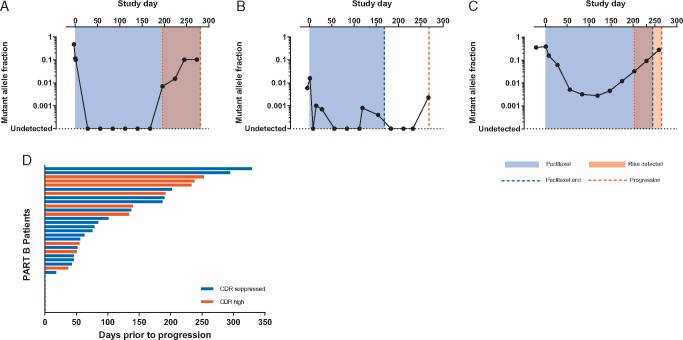

Lead-time of sequential ctDNA tracking

Sequential ctDNA tracking through treatment may identify, in patients with initial treatment response, the time at which the tumour develops resistance to treatment anticipating clinical progression. In 50 patients in the part B randomised study, with sequential samples available for analysis, we tracked ctDNA mutations every 4 weeks throughout treatment to progression (Figure 4A–C). Diverse dynamics were observed through treatment. In several patients ctDNA fell to a nadir at or below the limit of detection, before a clear rise in ctDNA occurred marking the development of resistance, with substantial lead-time over clinical progression (Figure 4A). However, ctDNA dynamics were not easy to interpret in other patients, including patients with fluctuations around the nadir that made identification of the true rise challenging (‘bumping along the bottom’, Figure 4B), and patients who had a slow rise from nadir making identification of the exact point of rise challenging (‘slow rise’, Figure 4C). The ‘bumping along the bottom’ pattern likely reflected stochastic sampling issues with only relatively minor differences in total plasma DNA between timepoints (supplementary Table S6, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 4.

Circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) dynamics during treatment and lead-time over clinical progression. (A) Longitudinal tracking of a PIK3CA c.1633G>A (p.E545K) mutation in a patient who demonstrates a clear fall to a sustained nadir and a clear rise before clinical progression. (B) Longitudinal tracking of a PIK3CA c.3140 A>G (p.H1047R) mutation in a patient who demonstrates a fall in ctDNA which then fluctuates at a low level across multiple timepoints. (C) Longitudinal tracking of a PIK3R1 DelCTGAGA (p.L573_R574del) deletion in a patient who demonstrates a clear fall in ctDNA but a gradual rise over subsequent cycles before clinical progression. (D) Distribution of lead-time of calculated molecular progression before confirmed clinical progression (range 0–329 days).

We defined criteria for ctDNA progression incorporating both ‘rise from nadir’ (Figure 4) and ‘rise towards baseline’ (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online) criteria (see Materials and methods). The rise from nadir criteria identified a median 3.1-month lead-time, whereas the alternative rise towards baseline formula identified a 2.6 median month lead time (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). A lead-time over clinical progression was apparent in the majority of patients 74% (26/35) (Figure 4D, supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online), although it did not report a lead-time over relapse in 26% (9/35) patients.

Clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential is frequent in advanced breast cancer

To identify mutations to track in the validation cohort, plasma was sequenced with the AZ300 assay. Using this approach, 30% (18/59) of patients were classified as having evidence of detectable clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) (Figure 5A). CHIP was strongly suspected if a mutation was identified in the following genes: DNMT3A, ASXL1, TET2, JAK2, SF3B1, CBL, GNAS, and IDH2 [23–25]. TP53 was not included in this analysis as this gene is commonly mutated in breast cancer, despite also being CHIP associated (supplementary Figure S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). Buffy coat germline DNA was not available to validate the CHIP variants. We investigated the clinical factors that associated with detection of potential CHIP, with prior anthracycline chemotherapy showing limited evidence of being positively associated with detection of CHIP (odds ratio 2.5; 95% confidence interval 0.69–8.9, Figure 5B, P = 0.155). The presence of CHIP had no effect on on-treatment nadir leukocytes (CHIP detected median 3.71 versus CHIP not detected median 3.05, P = 0.12) nor nadir neutrophil count (CHIP detected median 1.63 versus CHIP not detected median 1.70 P = 0.27). In a PIK3CA mutation-positive patient, we tracked a DNMT3A CHIP mutation through treatment demonstrating no change in allele fraction during treatment (Figure 5C), despite a clear response in the PIK3CA mutation. PFS was similar in patients with baseline CHIP and without detected CHIP (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) is frequently detected in advanced breast cancer. (A) Clonal haematopoiesis variants detected by sequencing of baseline plasma in part B. (B) Clinical and pathological associations of CHIP detection in baseline plasma. (C) Longitudinal tracking of a PIK3CA c.3140 A>G (p.H1047R) mutation and a DNMT3A CHIP splice site donor c.25236935 C>T variant in the same patient. (D) Progression-free survival by baseline detection of CHIP for the whole study population, capivasertib and placebo treatment arms. P values from log rank test.

Discussion

Circulating tumour DNA dynamics may present a more rapid way to assess efficacy of treatment than conventional cross-sectional imaging [1–3, 18, 19]. In this study, we prospectively validated early ctDNA dynamics as a marker of treatment efficacy, demonstrating that early dynamics is a surrogate for PFS. We subsequently show that early ctDNA assessment predicted the results of the randomised phase II trial and correctly predicted that PIK3CA mutations did not identify ER+/HER2- cancers that were sensitive to AKT inhibition with capivasertib when combined with paclitaxel.

We show patients who suppress ctDNA after 4 weeks of treatment with paclitaxel with or without capivasertib have substantially improved PFS (Figure 3A, supplementary Figure S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). For patients with high ctDNA, this allows the identification of those patients who may benefit from an adaption in treatment. A few (approximately 9% 4/42) patients derived longer benefit from paclitaxel (>200 days) despite high on-treatment ctDNA (high CDR28). In these patients, stopping paclitaxel on the basis of high CDR28 could conceivably be detrimental, and adaption to add in additional treatment may be more appropriate. Prospective randomised trials are required to assess whether early on-treatment treatment adaption has clinical utility.

Our data suggest that early ctDNA dynamics also represent a surrogate of targeted therapy efficacy when added to standard therapy. The BEECH study demonstrated that capivasertib added to paclitaxel did not improve PFS reported by Turner et al. [22] in this population, and equally capivasertib did not result in greater early ctDNA suppression than placebo. In contrast, early ctDNA assessment in the PALOMA3 phase III study of fulvestrant and palbociclib or placebo demonstrated substantially improved PFS and ctDNA suppression with the addition of palbociclib. Therefore, early ctDNA dynamics has the potential to considerably improve decision making in early drug development, evaluating drug efficacy early, and assessing whether a biomarker (here PIK3CA mutation) predicts for targeted therapy efficacy.

Tracking ctDNA through treatment identifies a diversity of patterns of ctDNA progression. Patients with a sharp initial drop in ctDNA often demonstrate a clear rise that would appear to signify an event in the tumour that promotes resistance. However, identifying the rise in other patients is challenging due to variation along the nadir in responding tumours, largely reflecting stochastic sampling issues, or a slow rise from the nadir in other tumours. Developing a robust criterion to predict ctDNA rise and molecular resistance, essential for interventional studies triggered by ctDNA rise, was challenged by this diversity of ctDNA tracking patterns. Although the tracked mutations in this study are commonly clonal, we cannot account for the possibility that we tracked sub-clonal mutations that may show divergent dynamics during treatment compared with clonal mutations. Tracking multiple mutations could potentially resolve this but availability of material for further mutational analysis is limiting in this study [8, 12, 26, 27].

Our work identified frequent clonal haematopoiesis through ctDNA sequencing and identified prior adjuvant anthracycline chemotherapy exposure as a factor for the high prevalence in advanced breast cancer. Tolerance of chemotherapy was unaffected by CHIP, as was PFS [28], suggesting that CHIP had no clinical consequence in these patients. Age was not a significant factor in our cohort, likely reflecting the dominant effect of prior chemotherapy in this cohort, in contrast with the effect of age in healthy volunteers reports [23, 24]. CHIP mutations remained constant tracking throughout treatment (Figure 5C), emphasising the importance of not inadvertently tracking the dynamics of a CHIP mutation in an individual patient.

In summary, we show that early ctDNA dynamics is a strong surrogate end point for PFS and also provide a surrogate assessment of efficacy of add-on targeted therapies. Early ctDNA dynamics have the potential to inform individual treatment decisions and improve early drug development due to the potential to act as a surrogate of trial outcome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participated in the BEECH trial and the investigators and study staff who supported the trial.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from Breast Cancer Now and AstraZeneca (no grant numbers apply). We also acknowledge National Institute for Health Research funding to the Royal Marsden and Institute of Cancer Research Biomedical Research Centre. No grant numbers are applicable for any of the above funding sources.

Disclosure

IK, RM, JR, RM, THC, ECB and GS are employees of AstraZeneca. MO received grant/research support (to the Institution) from AstraZeneca, Boehringe-Ingelheim, Cascadian Therapeutics, Celldex, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Immunomedics, Novartis, Seattle Genetics, Philips Healthcare, Piqur, PUMA Biotechnology, Roche and Sanofi; consultant fees from GSK, PUMA Biotechnology and Roche; honoraria from Roche and travel grants from GP Pharma, Grüenthal, Novartis, Pierre-Fabre and Roche. NCT has received advisory board honoraria and research funding from AstraZeneca and research funding from BioRad. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Notes: This study was partially previously presented at: AACR 106th Annual Meeting 2015, 18–22 April 2015, Philadelphia, PA, USA (abstract number CT331) and ESMO 2017 Congress, 8–12 September 2017, Madrid, Spain (abstract number 241PD).

References

- 1. Dawson SJ, Tsui DW, Murtaza M. et al. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(13): 1199–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murtaza M, Dawson SJ, Tsui DW. et al. Non-invasive analysis of acquired resistance to cancer therapy by sequencing of plasma DNA. Nature 2013; 497(7447): 108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Forshew T, Murtaza M, Parkinson C. et al. Noninvasive identification and monitoring of cancer mutations by targeted deep sequencing of plasma DNA. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4: 136ra168.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ. et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6: 224ra224.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Diehl F, Schmidt K, Choti MA. et al. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat Med 2008; 14(9): 985–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thierry AR, Mouliere F, Gongora C. et al. Origin and quantification of circulating DNA in mice with human colorectal cancer xenografts. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38(18): 6159–6175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parkinson CA, Gale D, Piskorz AM. et al. Exploratory analysis of TP53 mutations in circulating tumour DNA as biomarkers of treatment response for patients with relapsed high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma: a retrospective study. PLoS Med 2016; 13: e1002198.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abbosh C, Birkbak NJ, Wilson GA. et al. Phylogenetic ctDNA analysis depicts early-stage lung cancer evolution. Nature 2017; 545(7655): 446–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tie J, Kinde I, Wang Y. et al. Circulating tumor DNA as an early marker of therapeutic response in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2015; 26(8): 1715–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sanmamed MF, Fernandez-Landazuri S, Rodriguez C. et al. Quantitative cell-free circulating BRAFV600E mutation analysis by use of droplet digital PCR in the follow-up of patients with melanoma being treated with BRAF inhibitors. Clin Chem 2015; 61(1): 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hyman DM, Smyth LM, Donoghue MTA. et al. AKT inhibition in solid tumors with AKT1 Mutations. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(20): 2251–2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O'Leary B, Hrebien S, Morden JP. et al. Early circulating tumor DNA dynamics and clonal selection with palbociclib and fulvestrant for breast cancer. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ma CX, Bose R, Gao F. et al. Neratinib efficacy and circulating tumor DNA detection of HER2 mutations in HER2 non-amplified metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23(9): 5687–5695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen YH, Hancock BA, Solzak JP. et al. Next-generation sequencing of circulating tumor DNA to predict recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer patients with residual disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. NPJ Breast Cancer 2017; 3: 24.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cabel L, Riva F, Servois V. et al. Circulating tumor DNA changes for early monitoring of anti-PD1 immunotherapy: a proof-of-concept study. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(8): 1996–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marchetti A, Palma JF, Felicioni L. et al. Early prediction of response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors by quantification of EGFR mutations in plasma of NSCLC patients. J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10(10): 1437–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garcia-Murillas I, Schiavon G, Weigelt B. et al. Mutation tracking in circulating tumor DNA predicts relapse in early breast cancer. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7(302): 302ra133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Frenel JS, Carreira S, Goodall J. et al. Serial next-generation sequencing of circulating cell-free DNA evaluating tumor clone response to molecularly targeted drug administration. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21(20): 4586–4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xi L, Pham TH, Payabyab EC. et al. Circulating tumor DNA as an early indicator of response to T-cell transfer immunotherapy in metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22(22): 5480–5486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ. et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351(8): 781–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smerage JB, Barlow WE, Hortobagyi GN. et al. Circulating tumor cells and response to chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer: SWOG S0500. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(31): 3483–3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Turner NC, Alarcón E, Armstrong AC. et al. BEECH: a dose-finding run-in followed by a randomised phase II study assessing the efficacy of AKT inhibitor capivasertib (AZD5363) combined with paclitaxel in patients with estrogen receptor-positive advanced or metastatic breast cancer, and in a PIK3CA mutant sub-population. Ann Oncol 2019; 30(5): 774–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Genovese G, Kahler AK, Handsaker RE. et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(26): 2477–2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J. et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(26): 2488–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Acuna-Hidalgo R, Sengul H, Steehouwer M. et al. Ultra-sensitive sequencing identifies high prevalence of clonal hematopoiesis-associated mutations throughout adult life. Am J Hum Genet 2017; 101(1): 50–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Newman AM, Bratman SV, To J. et al. An ultrasensitive method for quantitating circulating tumor DNA with broad patient coverage. Nat Med 2014; 20(5): 548–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, Horswell S. et al. Detection of ubiquitous and heterogeneous mutations in cell-free DNA from patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2016; 27(5): 862–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jongen-Lavrencic M, Grob T, Hanekamp D. et al. Molecular minimal residual disease in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(13): 1189–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.