Abstract

The present study assessed the effectiveness of the combined administration of tranexamic acid (TXA) plus low‐dose epinephrine in primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA). We searched the following Chinese electronic databases: China National Knowledge Infrastructure and WanFang Data. We also searched the following English electronic databases: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Central Register of Controlled Trials. To search for additional eligible studies, we also used Google's search engine. All randomized controlled trials (RCT) comparing TXA plus low‐dose epinephrine (Combined group) and TXA alone in TKA were systematically searched. The primary outcomes were total blood loss, hidden blood loss, the requirement for transfusion, maximum hemoglobin (Hb) drop, and deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Drainage volume, operation time, length of stay, hospital for special surgery (HSS) score, and range of motion (ROM) were considered as secondary outcomes. Subgroup analyses were performed to assess the benefits of using a tourniquet and the application routes of topical or intravenous TXA between the two groups. Statistical analysis was assessed using RevMan 5.3 software. Four independent RCT were included involving 426 patients, with 213 patients in the Combined group and 213 patients in the TXA alone group. In the Combined group there was significant reduction in total blood loss (MD, 204.70; 95% CI, −302.76 to −106.63; P < 0.0001), hidden blood loss (MD, 185.63; 95% CI, −227.56 to −143.71; P < 0.00001), drainage volume (MD, 93.49; 95% CI, −117.24 to −69.74; P < 0.00001), and maximum Hb drop (MD, 5.33, 95% CI, −6.75 to −3.91; P < 0.00001). No statistical differences were found postoperatively in terms of the requirement for transfusion (risk ratio, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.26–1.04; P = 0.06), operation time (MD, 0.85; 95% CI, −2.62 to 4.31; P = 0.63), length of stay (MD, −0.02; 95% CI, −0.52 to 0.47; P = 0.93), HSS score (MD, 0.78; 95% CI, −0.36 to 1.92; P = 0.18), and ROM (MD, 1.40; 95% CI, −1.01 to 3.81; P = 0.26), and not increasing the risk of DVT (risk ratio, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.33 to 3.02; P = 1.00) in the two groups. This meta‐analysis demonstrated that the administration of tranexamic acid plus low‐dose epinephrine is a safe and efficacious treatment to reduce total blood loss, hidden blood loss, drainage volume, and maximum Hb drop in primary TKA, without increasing the risk of DVT in primary THA.

Keywords: Blood loss, Low‐dose epinephrine, Total knee arthroplasty, Tranexamic acid

Introduction

As the aging population increases, the demand for primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) by 2030 is expected to grow by 673% to 3.48 million in the United States1. Substantial perioperative blood loss occurs due to high fibrinolysis caused by surgical trauma and tourniquet enhancement is still an important factor in delaying the recovery of patients2, 3, 4, 5.

Tranexamic acid (TXA), a fibrinolytic inhibitor, can effectively and safely reduce perioperative blood loss and transfusion requirements in patients with primary TKA, although the optimal dosage and method of application is still controversial6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. As a new strategy for reducing blood loss, adrenaline has also been used recently to reduce perioperative blood loss.

Some studies have shown that low‐dose epinephrine administration reduces perioperative blood loss in TKA without increasing the incidence of complications. As previously reported, low‐dose epinephrine can effectively promote platelet aggregation and spleen contraction by activating a‐adrenoreceptors, immediately increasing platelet counts by 20%–30%12, 13, 14. In addition, several randomized controlled trials (RCT) have investigated the combined application of TXA and low‐dose epinephrine; however, to our knowledge, few meta‐analyses have compared the benefits of a combination strategy of these two hemostatic agents in primary TKA15, 16. Thus, the advantages of combining TXA with low‐dose epinephrine are not clear. In this meta‐analysis of RCT, the hypothesis suggests that the combined use of TXA + low‐dose epinephrine in primary TKA will result in a reduction of blood loss compared with patients receiving TXA alone. In addition, we also compared the requirement for transfusion and complications, including the incidence of deep venous thrombosis (DVT). We performed a subgroup analysis on the basis of whether or not to use a tourniquet and the application routes of topical or intravenous (IV) TXA.

Methods

This systematic review follows the preferred reporting project of the system assessment and meta‐analysis (PRISMA) guidelines, and institutional review boards were not needed because the data is drawn from other studies17.

Search Methods

Search Sources

We searched the following Chinese electronic databases: China National Knowledge Infrastructure (February 2018) and WanFang Data (February 2018). We also searched the following English electronic databases: PubMed (1966 to February 2018), Embase (1974 to February 2018), Web of Science (1990 to February 2018), and the Central Register of Controlled Trials (February 2018). To search for additional eligible studies, we also used the Google search engine (February 2018).

Search Strategy

We used a specific set of keywords to search the above databases: (Epinephrine OR Adrenaline) AND (Tranexamic acid OR TXA OR TA) AND (total knee arthroplasty OR total knee replacement OR TKA OR TKR). There is no restriction on language and region.

Search strategy of PubMed and Embase:

#1 Total Knee Arthroplasty;

#2 Total Knee Replacement;

#3 TKA;

#4 TKR;

#5 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4;

#6 Epinephrine;

#7 Adrenaline;

#8 #6 OR #7;

#9 #5 AND #8.

Selection Criteria

Inclusion criteria: (i) studies were RCT; (ii) participants underwent primary TKA; (iii) the interventions included the TXA + low‐dose epinephrine in the Combined group and the TXA group in the control group; (iv) each RCT included adequate sample size; and (v) one of the following results was reported: total blood loss, hidden blood loss, drainage volume, the requirement for transfusion, operation time, length of stay, maximum hemoglobin (Hb) drop, hospital for special surgery (HSS) score, range of motion (ROM), and DVT.

Exclusion criteria: single abstracts, the case reported or studies without full text available.

Disputes were resolved through consultation, or by consulting a third reviewer.

Assessment of Methodological Quality

Two reviewers (Yuan‐gang Wu, Yi Zeng) independently assessed the methodological quality using the Cochrane Collaboration for Systematic Reviews18. It included seven items: random sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcomes assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias. The overall methodological quality of each included study was characterized as “Yes” (low risk of bias), “No” (high risk of bias), or “Unclear” (unclear risk of bias). In addition, two reviewers (Qin‐sheng Hu, Xian‐chao Bao) independently assessed the risk of bias using the modified Jadad scale19. Studies obtaining 4 or more points (up to 8 points) were considered to be of high quality. Disagreements were resolved by consensus and, if necessary, a third reviewer (Bin Shen) was consulted.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes were total blood loss, hidden blood loss, the requirement for transfusion, maximum hemoglobin drop, and DVT. Drainage volume, operation time, length of stay, HSS score, and ROM were considered as secondary outcomes.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers (Yuan‐gang Wu and Hua‐zhang Xiong) independently extracted patient characteristics in all studies, including the author, date of publication, age, gender, number of participants, methods of intervention, DVT prophylaxis, DVT screening, and transfusion protocols. All data were entered into an electronic spreadsheet. If the study reported different follow‐up times, we chose longer follow‐up to avoid duplication. If necessary, we contacted the original authors of eligible studies by email to obtain adequate information.

Data Synthesis

RevMan 5 software (version 5.3, Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) was used to evaluate statistical analysis. Continuous data were calculated by mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Dichotomous data were calculated by risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). χ2‐tests and I 2‐statistics were used to assess statistical heterogeneity. If the χ2‐test > 0.1 or I 2 <50%, then the fixed‐effects model was adopted. Otherwise, a random‐effects model was adopted.

Results

Search Results

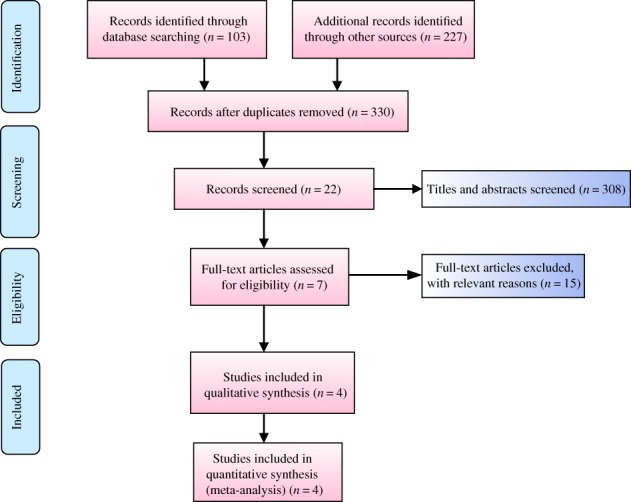

The steps involved in the study are shown in Fig. 1. A total of 330 potentially relevant studies were screened, 308 were excluded as irrelevant or duplicates based on titles and abstracts, and the full texts of the remaining 22 studies were read. After reading the full texts, 18 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Consequently, 4 RCT15, 16, 20, 21 were finally included on the basis of the selection criteria.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of inclusion and exclusion for included studies.

Study Characteristics and Quality Assessment

The total sample size of 426 patients in primary TKA comprised 213 patients in the Combined group and 213 patients in the TXA alone group. The sample size of included trials ranged from 48 to 59, and the average age of participants ranged from 59.66 to 69.7 years. The dose of topical TXA ranged from 1 to 3 g, and the dose of low‐dose epinephrine was 0.25 mg in all studies. All but 1 study16 involved surgery under the tourniquet; 308 patients used tourniquets, accounting for 72.3% of the total. A drainage tube was used in 2 studies20, 21, in which 208 patients used tourniquets, accounting for 48.8% of the total. All patients included in the study were given chemical DVT prophylaxis, such as rivaroxaban15, low molecular weight heparin20, 21, or low molecular weight heparin and rivaroxaban16. Table 1 summarizes the basic characteristics of all studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Authors (date) | Age | Gender (F/M) | Number of participants | Methods of intervention | DVT prophylaxis | DVT screening | Tourniquet | Transfusion | Modified Jadad score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined group | TXA group | Combined group | TXA group | Combined group | TXA group | Combined group | TXA group | ||||||

| Gao et al. (2015)15 |

68.5 | 67.4 | 11/39 | 13/37 | 50 | 50 | Topical 3 g TXA + 0.25 mg LDE | Topical 3 g TXA | Rivaroxaban and stockings | Doppler | Yes | Hb < 70 g/L, 70–100 g/L with anemia symptoms | 7 |

| Wei et al. (2016)20 |

68.6 | 67 | 19/29 | 17/31 | 48 | 48 | Topical 1 g TXA + 0.25 mg LDE | Topical 1 g TXA | LMWH | Doppler | Yes | Hb < 80 g/L | 5 |

| Zeng et al. (2018)16 | 59.66 | 61.54 | 21/38 | 20/39 | 59 | 59 | 10 mg/kg TXA iv. + topical 3 g TXA + 0.25 mg LDE | 10 mg/kg TXA iv. + topical 3 g TXA | LMWH | Doppler | No | Hb < 70 g/L, 70–100 g/L with anemia symptoms | 7 |

| Wu et al. (2017)21 | 69.7 | 68.9 | 22/34 | 20/36 | 56 | 56 | Topical 1 g TXA + 0.25mg LDE | Topical 1 g TXA | LMWH | Doppler | Yes | Hb < 70 g/L, 70–100 g/L with anemia symptoms | 6 |

DVT, deep venous thrombosis; Hb, hemoglobin; iv., intravenous; LDE, low‐dose epinephrine; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; TXA, tranexamic acid.

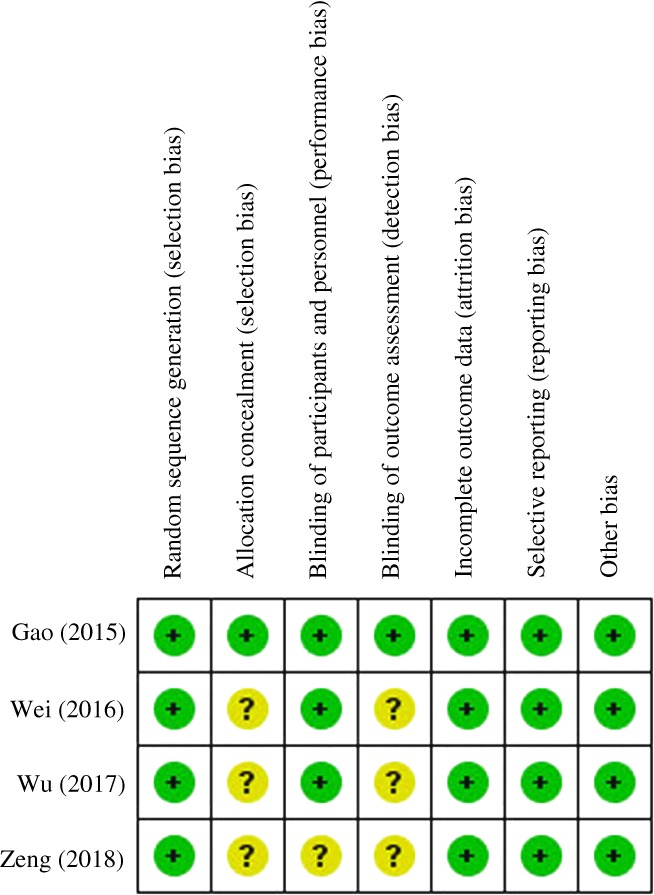

Figure 2 summarizes the methodological quality; all studies were relatively well designed. Randomized methods were performed in all studies and 3 RCT15, 20, 21 clearly reported blinding. The modified Jadad score showed a lower risk of bias (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary.

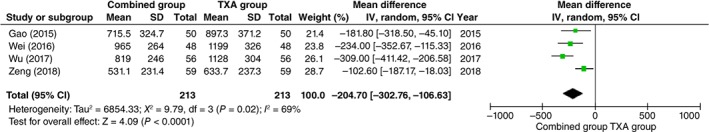

Meta‐analysis of Total Blood Loss

All studies15, 16, 20, 21 reported data on total blood loss (213 and 213 patients in the Combined and TXA groups, respectively). Pooling the data demonstrated that the combined administration of tranexamic acid plus low‐dose epinephrine significantly reduced the total blood loss by a mean of 204.70 mL compared with the TXA group (95% CI, −302.76 to −106.63; P < 0.0001). The pooled data showed statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.02, I 2 = 69%); therefore, the random‐effects model was adopted (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Funnel plots of total blood loss.

Meta‐analysis of Hidden Blood Loss

A total of 3 studies15, 20, 21 reported data on hidden blood loss (154 and 154 patients in the Combined and TXA groups, respectively). Pooling the data demonstrated that the combined administration of tranexamic acid plus low‐dose epinephrine significantly reduced hidden blood loss by a mean of 185.63 mL compared with the TXA group (95% CI, −227.56 to −143.71; P < 0.00001). The pooled data did not show statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.57, I 2 = 0%); therefore, the fixed model was adopted (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical results of meta‐analysis

| Clinical results | Studies | Number of participants | Incidence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Combined group | TXA group | P | MD/RR | 95% CI | Heterogeneity P (I 2) | Model | ||

| Hidden blood loss* | 3 | 308 | 154 | 154 | 0.00001 | −185.63 | −227.56 to −143.71 | 0.57 (0%) | Fixed |

| The requirement for transfusion† | 4 | 426 | 213 | 213 | 0.06 | 0.52 | 0.26 to 1.04 | 0.50 (0%) | Fixed |

| Maximum Hb drop* | 3 | 308 | 154 | 154 | <0.00001 | −5.33 | −6.75 to −3.91 | 0.96 (0%) | Fixed |

| Drainage volume* | 2 | 208 | 104 | 104 | <0.00001 | −93.49 | −117.24 to −69.74 | 0.18 (45%) | Fixed |

| Length of stay* | 2 | 218 | 109 | 109 | 0.93 | −0.02 | −0.52 to 0.47 | 0.36 (0%) | Fixed |

| Operation time* | 2 | 196 | 98 | 98 | 0.63 | 0.85 | −2.62 to 4.31 | 0.55 (0%) | Fixed |

| HSS score* | 2 | 218 | 109 | 109 | 0.18 | 0.78 | −0.36 to 1.92 | 0.41 (0%) | Fixed |

| ROM* | 2 | 218 | 109 | 109 | 1.40 | 0.26 | −1.01 to 3.81 | 0.78 (0%) | Fixed |

| DVT† | 4 | 426 | 213 | 213 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.33 to 3.02 | 0.43 (0%) | Fixed |

CI, confidence interval; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; HSS, hospital for special surgery; MD, mean difference; ROM, range of motion; RR, risk ratio; TXA, tranexamic acid

Values presented as mean difference and 95% confidence interval

Values presented as risk ratio and 95% confidence interval.

Meta‐analysis of the Requirement for Transfusion

A total of 4 studies15, 16, 20, 21 reported data on the requirement for transfusion. Transfusions were reported in 13 of 213 patients (6.1%) in the Combined group, compared with 24 of 213 patients (11.3%) in the TXA group. Pooling the data demonstrated that patients in the Combined group had similar benefits for transfusion requirements compared with the patients in the TXA group (risk ratio, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.26–1.04; P = 0.06). The pooled data did not show statistical heterogeneity; therefore, the fixed model was adopted (P = 0.50, I 2 = 0%) (Table 2).

Meta‐analysis of Maximum Hb Drop

A total of 3 studies15, 20, 21 reported data on maximum Hb drop (154 and 154 patients in the Combined and TXA groups, respectively). Pooling the data demonstrated that the combined administration of tranexamic acid plus low‐dose epinephrine significantly reduced the maximum Hb drop by a mean of 5.33 g/L compared with the TXA group (95% CI, −6.75 to −3.91; P < 0.00001). The pooled data did not show statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.96, I 2 = 0%); therefore, the fixed model was adopted.

Meta‐analysis of Drainage Volume

A total of 2 studies20, 21 reported data on drainage volume (104 and 104 patients in the Combined and TXA groups, respectively). Pooling the data demonstrated that the combined administration of tranexamic acid plus low‐dose epinephrine significantly reduced the drainage volume by a mean of 93.49 mL compared with the TXA group (95% CI, −117.24 to −69.74; P < 0.00001). The pooled data did not show statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.18, I 2 = 45%); therefore, the fixed model was adopted.

Meta‐analysis of the Length of Stay

A total of 2 studies15, 16 reported data on length of stay (109 and 109 patients in the Combined and TXA groups, respectively). Pooling the data demonstrated no significant difference in the two groups (MD, −0.02; 95% CI, −0.52 to 0.47; P = 0.93). The pooled data did not show statistical heterogeneity; therefore, the fixed model was adopted (P = 0.36, I 2 = 0%) (Table 2).

Meta‐analysis of Operation Time

A total of 2 studies15, 20 reported data on operation time (98 and 98 patients in the Combined and TXA groups, respectively). Pooling the data demonstrated no significant difference in the two groups (MD, 0.85; 95% CI, −2.62 to 4.31; P = 0.63). The pooled data did not show statistical heterogeneity; therefore, the fixed model was adopted (P = 0.55, I 2 = 0%) (Table 2).

Meta‐analysis of Hospital for Special Surgery Score

A total of 2 studies15, 16 reported data on HSS scores (109 and 109 patients in the Combined and TXA groups, respectively). Pooling the data demonstrated no significant difference in the two groups (MD, 0.78; 95% CI, −0.36 to 1.92; P = 0.18). The pooled data did not show statistical heterogeneity; therefore, the fixed model was adopted (P = 0.41, I 2 = 0%) (Table 2).

Meta‐analysis of Range of Motion

A total of 2 studies15, 16 reported data on ROM (109 and 109 patients in the Combined and TXA groups, respectively). Pooling the data demonstrated no significant difference in the two groups (MD, 1.40; 95% CI, −1.01 to 3.81; P = 0.26). The pooled data did not show statistical heterogeneity; therefore, the fixed model was adopted (P = 0.78, I 2 = 0%) (Table 2).

Meta‐analysis of Complications

A total of 4 studies15, 16, 20, 21 reported data on DVT. DVT was reported in 5 of 213 patients (2.3%) in the Combined group, compared with 5 of 213 patients (2.3%) in the TXA group. The total rate of DVT was 2.3%. Pooling the data demonstrated that the risk of DVT was similar in the two groups (risk ratio, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.33 to 3.02; P = 1.00). The pooled data did not show statistical heterogeneity; therefore, the fixed model was adopted (P = 0.43, I 2 = 0%) (Table 2).

Subgroup Analysis

Subgroup analyses were performed to assess the benefits of using a tourniquet and the application routes of topical or IV) TXA between the two groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of the meta‐analysis

| Clinical results | Studies | Number of participants | Incidence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Combined group | TXA group | P | MD/RR | 95% CI | Heterogeneity P (I 2) | Model | ||

| Total blood loss* | |||||||||

| Tourniquet | 3 | 312 | 156 | 156 | <0.00001 | −253.55 | −320.54 to −186.55 | 0.32 (13%) | Fixed |

| Non‐tourniquet | 1 | 118 | 59 | 59 | 0.02 | −102.60 | −187.17 to −18.03 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Topical TXA | 3 | 312 | 156 | 156 | <0.00001 | −253.55 | −320.54 to −186.55 | 0.32 (13%) | Fixed |

| IV TXA | 1 | 118 | 59 | 59 | 0.02 | −102.60 | −187.17 to −18.03 | n.s. | n.s. |

| The requirement for transfusion† | |||||||||

| Tourniquet | 3 | 308 | 154 | 154 | 0.18 | 0.59 | 0.27 to 1.28 | 0.42 (0%) | Fixed |

| Non‐tourniquet | 1 | 118 | 59 | 59 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.07 to 1.58 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Topical TXA | 3 | 308 | 154 | 154 | 0.18 | 0.59 | 0.27 to 1.28 | 0.42 (0%) | Fixed |

| IV TXA | 1 | 118 | 59 | 59 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.07 to 1.58 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Length of stay* | |||||||||

| Tourniquet | 1 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 0.38 | −0.60 | −1.93 to 0.73 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Non‐tourniquet | 1 | 118 | 59 | 59 | 0.80 | 0.07 | −0.47 to 0.61 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Topical TXA | 1 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 0.38 | −0.60 | −1.93 to 0.73 | n.s. | n.s. |

| IV TXA | 1 | 118 | 59 | 59 | 0.80 | 0.07 | −0.47 to 0.61 | n.s. | n.s. |

| HSS score* | |||||||||

| Tourniquet | 1 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 0.26 | 2.70 | −1.99 to 7.39 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Non‐tourniquet | 1 | 118 | 59 | 59 | 0.27 | 0.66 | −0.51 to 1.83 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Topical TXA | 1 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 0.26 | 2.70 | −1.99 to 7.39 | n.s. | n.s. |

| IV TXA | 1 | 118 | 59 | 59 | 0.27 | 0.66 | −0.51 to 1.83 | n.s. | n.s. |

| ROM* | |||||||||

| Tourniquet | 1 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 0.56 | 2.60 | −6.11 to 11.31 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Non‐tourniquet | 1 | 118 | 59 | 59 | 0.31 | 1.30 | −1.21 to 3.81 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Topical TXA | 1 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 0.56 | 2.60 | −6.11 to 11.31 | n.s. | n.s. |

| IV TXA | 1 | ||||||||

| DVT† | |||||||||

| Tourniquet | 3 | 308 | 154 | 154 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.22 to 2.92 | 0.26 (22%) | Fixed |

| Non‐tourniquet | 1 | 118 | 59 | 59 | 0.50 | 3.05 | 0.12 to 72.18 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Topical TXA | 3 | 308 | 154 | 154 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.22 to 2.92 | 0.26 (22%) | Fixed |

| IV TXA | 1 | 118 | 59 | 59 | 0.50 | 3.05 | 0.12 to 72.18 | n.s. | n.s. |

CI, confidence interval; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; HSS, hospital for special surgery; IV, intravenous; MD, mean difference; n.s., not state; ROM, range of motion; RR, risk ratio; TXA, tranexamic acid

Values presented as mean difference and 95% confidence interval

Values presented as risk ratio and 95% confidence interval.

Total Blood Loss

The outcome revealed that patients in the TXA plus low‐dose epinephrine group had significantly reduced total blood loss compared with the TXA alone group whether or not using a tourniquet and topical or IV TXA.

The Requirement for Transfusion

The outcome revealed that patients in the TXA plus low‐dose epinephrine group there was no significant difference in the requirement for transfusion compared with the TXA alone group whether or not using a tourniquet and topical or IV TXA.

Length of Stay

The outcome revealed that patients in the TXA plus low‐dose epinephrine group had no significant difference in length of stay compared with the TXA alone group whether or not using a tourniquet and topical or IV TXA.

Hospital for Special Surgery Score

The outcome revealed that patients in the TXA plus low‐dose epinephrine group had no significant difference in HSS score compared with the TXA alone group whether or not using a tourniquet and topical or IV TXA.

Range of Motion

The outcome revealed that patients in the TXA plus low‐dose epinephrine group had no significant difference in ROM compared with the TXA alone group whether or not using a tourniquet and topical or IV TXA.

Deep Venous Thrombosis

The outcome revealed that patients in the TXA plus low‐dose epinephrine group had no significant difference in DVT compared with the TXA alone whether or not using a tourniquet and topical or IV TXA.

Discussion

In light of the new blood management strategy, it is crucial to reduce postoperative blood loss and complications and to enhance recovery of patients after surgery. Therefore, we attempted to analyze the highest possible evidence from Level I trials using tranexamic acid and a low‐dose epinephrine in the primary TKA. The main finding of the meta‐analysis is that the combined administration of TXA + low‐dose epinephrine could significantly reduce total blood loss by a mean of 204.70 mL, hidden blood loss by a mean of 185.63 mL, and drainage volume by a mean of 93.49 mL, as well as decrease the maximum Hb drop by a mean of 5.33 g/L compared with the TXA group alone. We found no significant increase in the complication rates of DVT, while all studies demonstrated similar benefits in the requirements for transfusion, operation time, length of stay, HSS score, and ROM. The subgroup analysis also shows similar results between the two groups on the basis of the tourniquet and the application routes of TXA.

Similar studies have evaluated the effectiveness of the new strategy in the arthroplasty field. Among these, a randomized total hip arthroplasty trial demonstrated a 180‐mL decrease in blood loss while obtaining similar intraoperative blood loss, postoperative Hb concentration, and operation time22. Another RCT15 in TKA has also evaluated these results, which found that blood loss and transfusion rates were significantly reduced without increasing the risk of thromboembolic complications.

A recent meta‐analysis by Yu et al.23 published in Medicine assessed the combined use of tranexamic acid and epinephrine in the total joint arthroplasty. The authors included 3 studies comparing TKA15, 20, 24 and 2 studies22, 25 comparing THA. The primary outcome measures in their meta‐analysis were total blood loss and need for transfusion as they both included TKA and THA in their analysis and did not consider that the two types of surgery were different. We also found that a study24 did not meet the inclusion criteria for interventions with the control group, and the inclusion criteria needed to be strictly applied. Consequently, we carried out an updated meta‐analysis to help orthopaedic surgeons make wiser clinical decisions, and we believe that our meta‐analysis is a better way to assess the combined administration strategy of tranexamic acid and low‐dose epinephrine and to determine whether they can bring additional benefits in the primary TKA.

Many studies9, 10, 21 have been published on the use of TXA in total joint arthroplasty, and have produced positive clinical results. A retrospective cohort study26 involved 872 416 patients who had total hip or knee arthroplasty in 510 US hospitals by 2006–2012, and the results demonstrated that patients receiving TXA (vs those who did not) showed lower rates of allogeneic or autologous transfusion (7.7% vs 20.1%), while not having increased risk of thromboembolic complications (0.6% vs 0.8%). Similarly, a systematic review and meta‐analysis27 of 16 RCT comparing patients who received topical versus intravenous TXA in primary TKA indicated that both topical TXA and intravenous TXA are effective in reducing blood loss (P = 0.50) and transfusion rates (P = 0.52); in addition, topical use led to significantly lower transfusion rates in THA (P = 0.004) and TKA (P = 0.001), and the rates of thromboembolic events (P = 0.86) were similar in the two groups.

Epinephrine induces human platelet aggregation by binding to α 2‐adrenergic receptor1, 28 and constricts peripheral blood vessels to reduce bleeding, thus achieving an effective hemostatic effect. As Gasparini et al.29 report, local administration of epinephrine could be an effective and safe method for reducing blood loss and decreasing transfusion requirements in TKA. In the current meta‐analysis, the total blood loss, hidden blood loss drainage volume, and maximum Hb drop in the combined group were significantly reduced compared with those in the TXA group. These results were consistent with previous reports. The possible explanation for this effect was: first, the synthetic fibrinolytic inhibitor TXA is an effective way to reduce blood loss because it inhibits high fibrinolysis induced by surgical trauma6, 8, 9. Second, previous studies have found that the efficacy of epinephrine is associated with peak blood flow at 20–30 min after tourniquet release15, 28, 29. Local administration of epinephrine before tourniquet release could result in peripheral vasoconstriction and decreases peak blood flow15. Consequently, the effect of TXA and epinephrine is a synergistic hemostatic effect.

The requirement for transfusion was similar for both groups in our meta‐analysis (P = 0.06); a fixed model was adopted because there was no statistical heterogeneity. This phenomenon can be explained by low dose epinephrine showing only temporary procoagulant activity after administration, and this activity accelerates coagulation and fibrillation without changing the peak16. In addition, the lack of uniformity in blood transfusion standards may also potentially affect the outcome of blood transfusion assessment. No differences were found in operation time, length of stay, HSS score, and ROM.

Theoretically, patients treated with TXA plus low‐dose epinephrine are more at risk for thromboembolism. The epinephrine technique can promote platelet aggregation and spleen contraction by activating a‐adrenoreceptors, resulting in an instant 20%–30% increase in the peripheral count of platelets, and also increasing platelet aggregation as well as the risk of thrombosis. In this meta‐analysis, DVT confirmed that there were 5 cases in each group. The total rate of DVT was 2.3%. No significant differences were observed between the two groups using Doppler ultrasound examination. This phenomenon may be explained as follows. First, although TXA may have the potential risk of triggering thrombosis, this has not been confirmed6, 7, 8, 9, 10. Some authors even suggest that TXA can reduce the risk of thrombosis by reducing the need for blood transfusions30. Second, all patients were routinely treated with chemical drugs to prevent thrombosis during perioperative periods, such as rivaroxaban and low molecular weight heparin. Therefore, we have confidence in the results for DVT, and they were similar to those of other studies. Although epinephrine is effective in hemostasis, it has been successfully used in arthroplasty. However, the mechanism of alpha and beta‐epinephrine receptors may lead to cardiovascular side effects. Therefore, use in patients with pheochromocytoma, thyrotoxicosis, and digoxin should proceed with caution.

The main limitation of the current study was that only 4 RCT were searched in TKA by February 2018 and the sample size was relatively small in this meta‐analysis. Thus, more high‐quality RCT are required to confirm the above conclusion. Second, most studies report shorter follow‐up periods, which may potentially affect clinical outcomes such as DVT and wound complications. Third, the meta‐analysis included insufficient clinical data, such as blood pressure data. Therefore, it is very difficult to get the results if adrenaline has an extra effect on perioperative blood pressure. Finally, the different methods of operation, such as whether to use a tourniquet or a drainage tube, may have an effect on blood loss. However, it was difficult for us to compare these results by subgroup analysis because of sample size limitations.

Conclusion

This current meta‐analysis indicates that the combined administration of tranexamic acid plus low‐dose epinephrine can effectively reduce total blood loss, hidden blood loss, drainage volume, and maximum Hb drop compared with the use of TXA alone. No statistical differences were found postoperatively in terms of the requirement for transfusion, operation time, length of stay, HSS score, ROM, and not increasing the risk of DVT in the two groups in primary TKA.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Li Chen (chenli930@scu.edu.cn) from Analytical & Testing Center Sichuan University for her help with image processing and data analysis. Second, the funding should be changed as: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Program (No. 81601936, No. 81672219), and it was funded by the Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (No. 2018HH0141), and it was also funded by the Health Department of Chengdu city, Sichuan Province (No. 18ZD016).

References

- 1. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2007, 89: 780–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harsten A, Bandholm T, Kehlet H, Toksvig‐Larsen S. Tourniquet versus no tourniquet on knee‐extension strength early after fast‐track total knee arthroplasty; a randomized controlled trial. Knee, 2015, 22: 126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jawhar A, Hermanns S, Ponelies N, Obertacke U, Roehl H. Tourniquet‐induced ischaemia during total knee arthroplasty results in higher proteolytic activities within vastus medialis cells: a randomized clinical trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2016, 24: 3313–3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Skovgaard C, Holm B, Troelsen A, et al No effect of fibrin sealant on drain output or functional recovery following simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Acta Orthop, 2013, 84: 153–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Su EP, Mount LE, Nocon AA, Sculco TP, Go G, Sharrock NE. Changes in markers of thrombin generation and interleukin‐6 during unicondylar knee and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty, 2018, 33: 684–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Demos HA, Lin ZX, Barfield WR, Wilson SH, Robertson DC, Pellegrini VD Jr. Process improvement project using tranexamic acid is cost‐effective in reducing blood loss and transfusions after total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty, 2017, 32: 2375–2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jain NP, Nisthane PP, Shah NA. Combined administration of systemic and topical tranexamic acid for total knee arthroplasty: can it be a better regimen and yet safe? A randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty, 2016, 31: 542–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee SY, Chong S, Balasubramanian D, Na YG, Kim TK. What is the ideal route of administration of tranexamic acid in TKA? A randomized controlled trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2017, 475: 1987–1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nielsen CS, Jans Ø, Ørsnes T, Foss NB, Troelsen A, Husted H. Combined intra‐articular and intravenous tranexamic acid reduces blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2016, 98: 835–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Styron JF, Klika AK, Szubski CR, Tolich D, Barsoum WK, Higuera CA. Relative efficacy of tranexamic acid and preoperative anemia treatment for reducing transfusions in total joint arthroplasty. Transfusion, 2017, 57: 622–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu Y, Yang T, Zeng Y, Si H, Cao F, Shen B. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion requirements in primary simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis, 2017, 28: 501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bakovic D, Pivac N, Eterovic D, et al The effects of low‐dose epinephrine infusion on spleen size, central and hepatic circulation and circulating platelets. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging, 2013, 33: 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. von Känel R, Dimsdale JE. Effects of sympathetic activation by adrenergic infusions on hemostasis in vivo. Eur J Haematol, 2000, 65: 357–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yun‐Choi HS, Park KM, Pyo MK. Epinephrine induced platelet aggregation in rat platelet‐rich plasma. Thromb Res, 2000, 100: 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gao F, Sun W, Guo W, Li Z, Wang W, Cheng L. Topical administration of tranexamic acid plus diluted‐epinephrine in primary total knee arthroplasty: a randomized double‐blinded controlled trial. J Arthroplasty, 2015, 30: 1354–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zeng WN, Liu JL, Wang FY, Chen C, Zhou Q, Yang L. Low‐dose epinephrine plus tranexamic acid reduces early postoperative blood loss and inflammatory response: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2018, 100: 295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stewart LA, Clarke M, Rovers M, et al Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta‐analyses of individual participant data: the PRISMA‐IPD statement. JAMA, 2015, 313: 1657–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 2011, 343: d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huang Z, Ma J, Pei F, et al Meta‐analysis of temporary versus no clamping in TKA. Orthopedics, 2013, 36: 543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wei G, Liang J, Li YP, Wu QY, Chen JF. Efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid plus epinephrine on reducing postoperative blood loss after unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Zhong Guo Quan Ke Yi Xue, 2016, 3: 327–331. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu HY, Fan YM, Yang JX, Zhao J, Guo HL. Efficacy of intra‐articular injection of tranexamic acid plus epinephrine on postoperative blood loss in elderly patients with total knee arthroplasty. Chuang Shang Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2017, 19: 840–843. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jans Ø, Grevstad U, Mandoe H, Kehlet H, Johansson PI. A randomized trial of the effect of low dose epinephrine infusion in addition to tranexamic acid on blood loss during total hip arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth, 2016, 116: 357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yu Z, Yao L, Yang Q. Tranexamic acid plus diluted‐epinephrine versus tranexamic acid alone for blood loss in total joint arthroplasty: a meta‐analysis. Medicine, 2017, 96: e7095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhaohui L, Wanshou G, Qidong Z, Guangduo Z. Topical hemostatic procedures control blood loss in bilateral cemented single‐stage total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Sci, 2014, 19: 948–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gao F, Sun W, Guo W, Li Z, Wang W, Cheng L. Topical application of tranexamic acid plus diluted epinephrine reduces postoperative hidden blood loss in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty, 2015, 30: 2196–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S, et al. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ, 2014, 349: g4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang S, Gao X, An Y. Topical versus intravenous tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int Orthop, 2017, 41: 739–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Larsson J, Lewis DH, Liljedahl SO, Löfström JB. Early biochemical and hemodynamic changes after operation in a bloodless field. Eur Surg Res, 1977, 9: 311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gasparini G, Papaleo P, Pola P, Cerciello S, Pola E, Fabbriciani C. Local infusion of norepinephrine reduces blood losses and need of transfusion in total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop, 2006, 30: 253–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2011, 93: 1577–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]