Abstract

Although Pantoea species are widely distributed among plants, water, soils, humans, and animals, due to a lack of efficient isolation methods, the clonality of Pantoea species is poorly characterized. Therefore, we developed a new semi-selective medium designated ‘lysine-ornithine-mannitol-arginine-charcoal’ (LOMAC) to isolate these species. In an inclusive and exclusive study examining 94 bacterial strains, all Pantoea strains exhibited yellow colonies on LOMAC medium. The performance of the medium was assessed using Pantoea-spiked soils. Percent average agreement relative to the Api20E biochemical test was 97%. A total of 24 soil spot samples and 19 plant types were subjected to practical trials. Of the 91 yellow colonies selected on LOMAC medium, 81 were correctly identified as Pantoea species using the biochemical test. The sequencing of 16S rRNA (rrs) and gyrB from these isolates confirmed that Pantoea agglomerans, P. vagans, P. ananatis, and P. deleyi were present in Japanese fields. A phylogenetic analysis using rrs enabled only the limited separation of strains within each Pantoea spp., whereas an analysis using gyrB revealed higher variability and enabled the finer resolution of distinct branches. P. agglomerans isolates were divided into 3 groups, 2 of which were new clades, with the other comprising a large group including biocontrol strains. P. vagans was also in one of the new clades. The present results indicate that LOMAC medium is useful for screening Pantoea species. The use of LOMAC medium will provide new opportunities for identifying the beneficial properties of Japanese Pantoea isolates.

Keywords: Pantoea sp., isolation, semi-selective medium, environment, phylogenetic analysis

Pantoea is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae, recently separated from the genus Enterobacter. The genus Pantoea includes at least 20 species, such as P. agglomerans, P. vagans (formerly a P. agglomerans strain), P. ananatis, P. deleyi, and P. eucalyptii (25). Members of Pantoea are motile, non-encapsulated, non-spore forming rods with peritrichous flagella, and are typically yellow pigmented. Pantoea are abundant in plant and animal products, arthropods and other animals, water, soil, dust and air, and occasionally in humans. Pantoea species exhibit both deleterious and beneficial characteristics. For example, although Pantoea species are known to cause crop diseases and disorders in exposed individuals via the inhalation of organic dusts (5–7, 16, 18), they also produce substances effective in the treatment of various cancers in humans and animals, suppress the development of various plant pathogens via antibiotic production and/or competition, and exhibit bio-fertilizer and bio-remediation properties (6).

Previous studies reported the isolation of unique Pantoea strains from environmental sources. Son et al. in Korea, Malboobi et al. in Iran, and Sulbaran et al. in Venezuela demonstrated that P. agglomerans strains isolated from soil exert beneficial effects on crops (6, 14, 15, 23, 24). In greenhouse and field trials, Malboobi et al. showed that P. agglomerans promoted the growth of potato plants (14, 15). Kageyama et al. isolated new Pantoea spp. from fruits and soils in Japan and demonstrated that these Japanese species were phylogenetically distant from other Pantoea species (3, 11). Japanese researchers also reported the efficacy of LPS from P. agglomerans for the treatment of human cancers. Kasugai et al. intradermally administered LPS in combination with transarterial intermittent chemotherapy to treat patients with advanced gastric cancer with multiple liver metastases (12).

Despite the apparent medical and agricultural significance of Pantoea spp., limited information is currently available on their distribution and prevalence, which is partly due to the lack of methods for efficient isolation and enumeration in the presence of competing organisms. Only a few media for detecting Pantoea spp. have been reported to date. Lysine-Ornithine-Mannitol (LOM) agar was developed in 1981 for isolating Enterobacter agglomerans (4); however, this medium was developed for testing human stool samples. PA 20 semi-selective medium was developed in 2006 for the isolation and enumeration of P. ananatis from plant material (10). Non-selective agar media, such as Nutrient agar and LB, are occasionally used to isolate Pantoea spp. The ability to produce a yellow pigment is used to identify Pantoea spp. on non-selective agar media, such as LB and Trypticase soy agar (5, 8, 9). However, the detection and isolation of Pantoea spp. from environmental sources (1, 9) will require a new semi-selective agar medium. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to develop a semi-selective medium for the isolation and enumeration of Pantoea spp. in the presence of competing organisms frequently found in soils and plants.

Materials and Methods

Semi-selective agar medium

The ingredients of lysine-ornithine-mannitol-arginine-charcoal (LOMAC) agar medium were placed into two groups. Solution A was prepared by adding the following (L−1) to water: 3 g of yeast extract (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI, USA), 2 g of sodium chloride (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan), 2 g of magnesium sulfate (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), 0.05 g of sodium pyruvate (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), 1 g of soy peptone (Conda, Madrid, Spain), 5 g of L-lysine hydrochloride (Peptide Institute, Osaka, Japan), 6.5 g of L(+)-ornithine hydrochloride (Peptide Institute), 5 g of L-arginine hydrochloride (Peptide Institute), 0.3 g of bromothymol blue (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 13.5 g of agar (SSK Sales, Shizuoka, Japan), and 2 g of charcoal (Serachem, Hiroshima, Japan). pH was adjusted to 6.5. Solution A was autoclaved at 121°C for 15 min and cooled to 50°C. Solution B was prepared by adding the following (50 mL−1) to water: 5.25 g of mannitol (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), 0.03 g of vancomycin hydrochloride (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), and 0.016 g of amphotericin B (Wako Pure Chemical Industries). Fifty milliliters of solution B was filter-sterilized and then mixed with 1 L of solution A. Charcoal was used as an absorbent against toxic chemicals to bacteria. Vancomycin and amphotericin B were used as inhibitors of Gram-positive bacteria and fungi, respectively. Media were designed for mannitol-positive, lysine-negative, ornithine-negative, and arginine-negative species, including Pantoea spp., to yield intensely yellow colonies (8). Mannitol-, lysine-, ornithine-, and arginine-negative species yield colorless colonies. Species that are mannitol-positive and either lysine-, ornithine-, or arginine-positive yield greenish-blue colonies. Species that are mannitol-negative and either lysine-, ornithine-, or arginine-positive yield colorless colonies that turn greenish-blue after more than 24 h.

Plating efficiency tests

A total of 86 bacterial and 8 fungal strains were examined (Table 1). These included 69 Gram-negative rods, including 13 Pantoea spp., 14 Gram-positive cocci, and 3 Gram-positive rods. These strains were sub-cultured on non-selective medium (Tryptic Soy Agar [TSA]; Difco Laboratories) at 35±2°C for 24 h. An overnight TSA culture of each bacterial colony was streaked onto LOMAC and LOM plates (4), which were incubated at 35±2°C and examined after 24 h for the presence or absence of yellow colonies.

Table 1.

Growth and colony color of microbes cultivated on semi-selective agar media LOMAC agar and LOM agar

| Nomenclature | Bacterial strains | Colony color | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| LOMAC*2 | LOM | ||

| Gram-negative rod | Pantoea agglomerans NBRC 102470*1 | Yellow | Yellow |

| Pantoea agglomerans ES53 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Pantoea agglomerans ES127 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Pantoea agglomerans ES137 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Pantoea agglomerans ES144 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Pantoea agglomerans ES149 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Pantoea agglomerans ES162 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Pantoea ananatis ES126 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Pantoea ananatis ES133 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Pantoea brenneri ES153 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Pantoea deleyi ES168 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Pantoea vagans ES63 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Pantoea vagans ES67 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii 142 | Blue | Brownish yellow | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii 610 | Green | Brownish yellow | |

| Acinetobacter lwoffii 85 | —*3 | — | |

| Cedecea davisae 369 | Blue white | Green | |

| Cedecea davisae 1319 | Blue white | Yellow | |

| Citrobacter freundii 370 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Citrobacter freundii 711 | White | Yellow | |

| Edwardsiella trada 371 | Blue white | Blue white | |

| Enterobacter aerogenes 373 | Blue white | Brownish yellow | |

| Enterobacter aerogenes 1278 | Blue white | Brown | |

| Enterobacter amnigenus 374 | White | Yellow | |

| Enterobacter asburiae 375 | Blue | Yellow | |

| Enterobacter cloacae 87 | Blue | Brown | |

| Enterobacter cloacae 372 | Blue white | Yellow | |

| Enterobacter cloacae 726 | Blue white | Whitish yellow | |

| Enterobacter intermedius 378 | Blue | Yellow | |

| Enterobacter kobei 379 | Blue white | Yellow | |

| Enterobacter sakazakii 380 | Green | Yellow | |

| Escherichia coli 84 | Blue white | Yellow | |

| Escherichia coli 381 | White | Yellow | |

| Escherichia coli 722 | White | Brownish yellow | |

| Hafnia alvei 382 | Blue | Brownish yellow | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca 500 | Blue white | Yellow | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca 1248 | Blue white | Yellow | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae 54 | Blue | Brown | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. Ozaenae 1233 | Blue | Brown | |

| Klebsiella Pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae 383 | Whitish yellow | Brownish yellow | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae 1223 | Yellow | Brown | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae 476 | Blue white | Brown | |

| Morganella morganii 1434 | Blue | Yellow | |

| Plesiomonas shigelloides 73 | Blue white | Blue | |

| Proteus mirabilis 81 | White | Yellow | |

| Proteus vulgaris 56 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Proteus vulgaris 384 | White | Yellow | |

| Providencia alcalifaciens 1454 | Whitish yellow | Yellow | |

| Providencia rettgeri 385 | Clear | Yellow | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 729 | White | Brownish yellow | |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens 607 | Blue white | Brown | |

| Shewanella putrefaciens 147 | Blue | Brown | |

| Vibrio alginolyticus 150 | Brownish yellow | Brown | |

| Vibrio fluvialis 153 | Blue green | Yellow | |

| Vibrio mimicus 151 | Blue green | Green | |

| Vibrio vulnificus 149 | Green | Green | |

| Yersinia enterocolitica 134 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Yersinia enterocolitica 389 | Clear | Yellow | |

| Salmonella typhimurium 677 | Blue | Brownish yellow | |

| Salmonella enteritidis 672 | Blue | Yellow | |

| Shigella flexneri 80 | Blue | Yellow | |

| Shigella sonnei 143 | Blue | Yellow | |

| Serratia ficaria 1364 | Blue | Yellow | |

| Serratia fonticola 1369 | Blue | Yellow | |

| Serratia marcescens 387 | Red | Brown | |

| Serratia marcescens 1344 | Red | Brown | |

| Serratia odorifera 1379 | Whitish yellow | Yellow | |

| Serratia plymuthica 1398 | Yellow | Yellow | |

| Serratia rubidaea 1354 | Red | Yellow | |

|

| |||

| Fungi | Candida albicans 110 | Blue white | Brown |

| Candida albicans 111 | Blue white | Brown | |

| Candida kefyr 116 | — | — | |

| Candida krusei 114 | White | Yellow | |

| Candida parapsilosis 120 | Blue white | Brown | |

| Candida tropicalis 651 | White | Yellow | |

| Cryptococcus neoformans 105 | — | — | |

| Cryptococcus neoformans 119 | Blue white | Brown | |

|

| |||

| Gram-positive rod | Bacillus cereus 77 | — | — |

| Bacillus subtilis 625 | — | — | |

| Bacillus subtilis 626 | — | — | |

|

| |||

| Gram-positive cocci | Enterococcus casseliflavus 70 | — | — |

| Enterococcus faecalis 106 | — | — | |

| Enterococcus faecalis 545 | — | — | |

| Enterococcus faecalis 546 | — | — | |

| Enterococcus faecium 547 | — | — | |

| Enterococcus faecium 548 | — | — | |

| Enterococcus gallinarum 69 | — | — | |

| Staphylococcus aureus 75 | — | — | |

| Staphylococcus aureus 89 | — | — | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis 58 | — | — | |

| Streptococcus oralis 135 | — | — | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae 58 | — | — | |

| Streptococcus pyogenes 538 | — | — | |

| Streptococcus sanguinis 83 | — | — | |

Synonym of the type strain of Pantoea agglomerans American Type Culture Collection 27155.

LOMAC: Lysine-Ornithine-Mannitol-Arginine-charcoal.

No growth.

The recovery of Pantoea species using LOMAC medium was evaluated based on the efficiency of colony formation. Bacterial suspensions from fresh colonies grown on TSA were adjusted in sterile saline to an optical density at 660 nm (OD660) of 0.5 (ca. 1.5×108 CFU mL−1). Bacterial suspensions were serially diluted 10-fold, and 0.1-mL aliquots of each dilution were plated on the tested plate media. The recovery percentage was calculated from the ratio of the mean colony counts on the test medium and on non-selective TSA as a reference.

Verification of LOMAC agar medium for the cultivation of Pantoea spp. from environmental soils

The effectiveness of the LOMAC plate for bacterial recovery was demonstrated in soils (1 g) spiked with 1:105 dilutions of P. agglomerans NBRC 102470 (1.5×108 CFU mL−1). Soils spiked with P. agglomerans were added to sterile saline (20 mL) and vortexed for 30 s in a mixer. The supernatant was serially diluted 1:10 in sterile saline, and 0.1 mL of the suspension was spread on LOMAC agar. The plates were incubated for 24 to 48 h at 35±2°C. After the incubation, all colonies obtained were streaked onto TSA medium and incubated at 35±2°C for 24 h. Isolates were identified by biochemical testing using the Api20E system (Sysmex bioMérieux, Tokyo, Japan).

Sample collection and practical trials

Samples of plants and environmental soils were obtained from 26 areas in Japan. Samples of soil (1 g) were added to sterile saline (20 mL) and vortexed for 30 s in a mixer. Similarly, plant samples (1 g) were added to sterile saline (10 mL) and homogenized using a mortar and pestle. After filtering using a cell strainer (40 μm), the flow through fraction was serially diluted 1:10 in sterile saline, and 0.1 mL of the suspension was spread on LOMAC agar medium and non-selective TSA medium. After an incubation at 35±2°C for 24 to 48 h, bacterial colonies with a yellow color were selected, passaged onto TSA medium, and incubated at 35±2°C for 24 h. After a second incubation, the isolates were identified by biochemical testing using the Api20E system.

PCR and phylogenetic analysis of sequencing data

Bacterial DNA was extracted using a QIAamp UCP Pathogen Mini kit (Qiagen KK, Tokyo, Japan). PCR amplification of the housekeeping genes 16S rRNA (rrs) and gyrB was performed using the following primer sets: 16S-8F and 16S-1492R for rrs, and gyr-320 and rgyr-1260 for gyrB (20). PCR targeting for rrs encoding 16S rRNA was performed with the ExTaq (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) enzyme under the same conditions as those previously described (20), except for an annealing temperature set to 49°C. PCR targeting for gyrB encoding partial GyrB was performed with initial denaturation and activation of the ExTaq enzyme at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 50°C for 45 s, elongation at 72°C for 60 s, and final elongation at 72°C for 7 min. Positive PCR amplification was verified electrophoretically using 5 μL of each reaction loaded onto a 1.5% agarose gel. PCR products were verified by DNA sequencing. Briefly, the PCR amplicon was purified with the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up kit (MACHEREY-NAGEL GmbH & Co. KG, Duren, Germany) and subjected to DNA sequencing. In 16S rRNA sequencing, additional primers, 16S-609R and 16S-533R, were used to achieve the complete coverage of the amplicon (20). In GyrB sequencing, DNA sequences were elucidated by the dideoxy termination method employing the same primers used for PCR amplification. Nucleotide sequences were searched for homology by BLAST screening against the GenBank databases. DNA sequences were aligned using ClustalW, and phylogenetic trees were generated based on partial gyrB sequences. Sites exhibiting alignment gaps were excluded from the analysis. NJplot program (19), version 2.3, was used to calculate evolutionary distances and infer trees based on the minimum evolution (ME) method using the maximum composite likelihood formula. The nodal robustness of the inferred trees was assessed using 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Nucleotide sequence accession number

The nucleotide sequences of the isolates in Japan reported here have been deposited in the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ databases and assigned the following accession numbers: LC422596 and LC422697 to LC422728 for the nucleotide sequence of gyrB; LC438406 to LC438434 for the nucleotide sequence of rrs.

Results

Growth and selectivity tests

To assess the selectivity of LOMAC medium for Pantoea strains and the growth of these strains on the medium, 86 bacterial strains, including P. agglomerans NBRC 102470, 6 isolates of P. agglomerans, 2 isolates of P. ananatis, P. brenneri ES153, P. deleyi ES168, 2 isolates of P. vagans, and 8 fungal strains were streaked on agar plates (Table 1). All Pantoea strains tested formed yellow colonies on LOMAC medium after being incubated for 24 h. However, 5 Gram-negative rods also formed yellow colonies on LOMAC medium. Acinetobacter lwoffii 85, Candida kefyr 116, Cryptococcus neoformans 105, and 14 Gram-positive cocci and 3 Gram-positive rods did not grow on the medium. The remaining isolates, including 50 Gram-negative rods and 6 fungi, formed colonies of various colors, such as blue, green, blue-white, white, whitish-yellow, clear, brownish-yellow, and red, but did not form yellow colonies. These results indicated that LOMAC medium is not only semi-selective for Pantoea strains, but also enables the differentiation of strains based on colony color.

Similarly, the selectivity of LOM medium for Pantoea strains and growth of the strains on the medium were tested (Table 1). All Pantoea strains tested formed yellow colonies on LOM medium after being incubated for 24 h. However, 30 Gram-negative rods and 2 fungi also formed yellow colonies on LOM medium. The remaining isolates, including 25 Gram-negative rods and 4 fungi, formed colonies of various colors, but did not form yellow colonies. There were no strains that were present on LOMAC medium but not on LOM medium. These results indicated that LOM medium is equal to LOMAC medium for selectivity to Pantoea strains, but not superior to LOMAC for the differentiation of strains based on colony color.

Recovery of growth on LOMAC medium

LOMAC medium and TSA medium were compared in terms of recovering the growth of 6 P. agglomerans strains, 2 P. ananatis strains, one P. brenneri strain, one P. deleyi strain, and 2 P. vagans strains. Plating efficiencies for the 12 Pantoea strains ranged between 44 and 182, i.e., 106% for P. agglomerans ES53, 92% for P. agglomerans ES127, 78% for P. agglomerans ES137, 56% for P. agglomerans ES144, 94% for P. agglomerans ES149, 93% for P. agglomerans ES162, 44% for P. ananatis ES126, 70% for P. ananatis ES133, 112% for P. brenneri ES153, 182% for P. deleyi ES168, 143% for P. vagans ES63, and 159% for P. vagans ES 67, with an average of 102%. The colonies of all Pantoea strains were yellow, convex, with smooth margins, and visible after the incubation at 35±2°C for 24 h. These results indicated that LOMAC medium supported the good growth of the Pantoea strains tested.

Evaluation of LOMAC agar medium for the cultivation of Pantoea spp. in soils

Bacterial recovery from soils was assessed using 3 different soils spiked with P. agglomerans NBRC 102470 (Table 2). LOMAC agar plates enabled the growth of 99 colonies, 10 of which were colonies with a yellow color. Fifty-five colonies were obtained from soil A; five of these were colonies with a yellow color and correctly identified as Pantoea spp.3 using Api20E. The other 50 colonies with non-yellow colors were not identified as any Pantoea species (Table 2). Soil B yielded 4 colonies with a yellow color. Only 1 colony was identified as Pantoea spp.3. The other 2 colonies were identified as Citrobacter youngae and the remaining colony as Leclercia adecarboxylate. Soil B also yielded 26 colonies with non-yellow colors. None of them were identified as Pantoea species. Similarly, Soil C yielded 1 colony with a yellow color, which was identified as Pantoea spp. 3. Soil C yielded 13 colonies with non-yellow colors, none of which were identified as Pantoea species (Table 2). Average percent positive and negative predictive values were 70% (7/10) and 100% (89/89), respectively. Overall agreement was 97% (96/99), indicating that Pantoea species were successfully isolated on the medium and that the colonies with a yellow color were instantaneously distinguishable as Pantoea species.

Table 2.

Evaluation of semi-selective LOMAC agar medium for the cultivation of Pantoea spp. from environmental soils

| Soil | LOMAC agar medium | Species identified by the biochemical test Api20E (No. of isolates tested) | % Positive predictive value | % Negative predictive value | % Overall agreement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Total no. of colonies | No. of yellow colonies | |||||

| A | 55 | 5 |

Yellow colonies: Pantoea sp3 (5) Non-yellow colonies: Aeromonas hydrophila/caviae/sobria (1), Bordetella/Alcaligenes/Moraxella spp. (2), Enterobacter amnigenus (3), Ochrobacterium anthropi (1), Photobacterium damselae (1), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (6), Pseudomonas fluorescens/putida (31), Pseudomonas luteora (3), Pseudomonas oryzihabitans (1), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (1) |

100% (5/5) | 100% (50/50) | 100% (55/55) |

| B | 30 | 4 |

Yellow colonies: Pantoea sp3 (1), Citrobacter youngae (2), Leclercia adecarboxylate (1), Non-yellow colonies: Acinetobacter baumannii/calcoaceticus (5), Enterobacter cloacae (10), Hafnia alvei (1), Klebsiella pneumoniae (1), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1), Pseudomonas fluorescens/putida (8) |

25% (1/4) | 100% (26/26) | 90% (27/30) |

| C | 14 | 1 |

Yellow colonies: Pantoea sp3 (1) Non-yellow colonies: Pseudomonas fluorescens/putida (13) |

100% (1/1) | 100% (13/13) | 100% (14/14) |

| 99 | 10 | 17 species | 70% (7/10) | 100% (89/89) | 97% (96/99) | |

Sample collection and practical trials for isolating Pantoea species

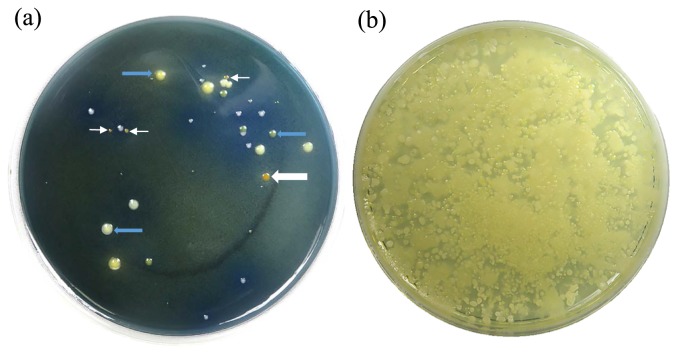

A total of 26 trials for isolating Pantoea species were performed using 24 spots of soil samples and 19 samples of plants obtained from geographically diverse regions of Japan, such as Nagano, Fukuoka, Chiba, and Hokkaido (Table 3). All samples were tested with LOMAC and TSA. LOMAC agar typically generated yellow colonies (Fig. 1a), whereas TSA medium did not have the ability to isolate Pantoea species producing a yellow pigment (Fig. 1b).

Table 3.

Pantoea species isolated in 26 practical trials

| Trial | Location | Sample | LOMAC agar medium | Species identified by the biochemical test Api20E (No. of isolates tested) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Total no. of colonies | No. of yellow colonies | No. of yellow colonies selected for biochemical test Api20E*1 | ||||

| Trial 1 | Nagano C-1 | Soil | 39 | 24 | 7 | Pantoea spp3 (1) |

| Trial 2 | Nagano A-1 | Soil | 19 | 0 | 0 | None |

| Trial 3 | Nagano B-1 | Weed leaf (d*2) | 209 | 48 | 8 | Pantoea spp3 (7) |

| Weed root (d) | 106 | 29 | 8 | Pantoea spp3 (3), Pantoea spp4 (1) | ||

| Soil | 59 | 4 | 4 | None | ||

| Trial 4 | Nagano C-2 | Soil | 8 | 0 | 0 | None |

| Trial 5 | Nagano D-1 | Soil | 36 | 0 | 0 | None |

| Trial 6 | Nagano E-1 | Soil | 107 | 3 | 1 | Serratia rubidaea (1) |

| Trial 7 | Nagano F-1 | Soil | 54 | 0 | 0 | None |

| Trial 8 | Nagano G-1 | Crops seed (d) | 466 | 57 | 13 | Pantoea spp3 (13) |

| Crops root (d) | 888 | 49 | 7 | Pantoea spp2 (6), Pantoea spp3 (1) | ||

| Soil | 9 | 3 | 3 | None | ||

| Trial 9 | Nagano H-1 | Soil | 15 | 0 | 0 | None |

| Trial 10 | Nagano I-1 | Soil | 49 | 0 | 0 | None |

| Trial 11 | Nagano A-2 | Soil | 96 | 0 | 0 | None |

| Trial 12 | Nagano B-2 | Soil | 183 | 5 | 4 | Pantoea spp3 (1), Klebsiella ozaenae (2) |

| Trial 13 | Nagano A-3 | Soil | 15 | 3 | 1 | None |

| Weed leaf (d) | 27 | 27 | 6 | Pantoea spp2 (6) | ||

| Weed root (d) | 7 | 0 | 0 | None | ||

| Trial 14 | Nagano B-3 | Weed root (d) | 75 | 6 | 4 | Pantoea spp3 (1), Pantoea spp2 (1) |

| Soil | 13 | 5 | 3 | None | ||

| Trial 15 | Nagano C-3 | Weed root (d) | 37 | 7 | 5 | Pantoea spp2 (1), Klebsiella ozaenae (3) |

| Weed leaf (d) | 59 | 36 | 8 | Pantoea spp3 (8) | ||

| Soil | 34 | 2 | 2 | None | ||

| Trial 16 | Nagano D-2 | Soil | 15 | 0 | 0 | None |

| Trial 17 | Nagano E-2 | Soil | 175 | 4 | 4 | None |

| Trial 18 | Nagano F-2 | Soil | 40 | 4 | 3 | Pantoea spp3 (1), Klebsiella ozaenae (1), Leclercia adecarboxylate (1) |

| Trial 19 | Nagano G-2 | Vegetable root (d) | 59 | 43 | 4 | None |

| Soil | 50 | 0 | 0 | None | ||

| Trial 20 | Nagano H-2 | Forage vegetable (d) | 410 | 336 | 11 | Pantoea spp3 (7), Pantoea spp2 (3), Rahnella aquatilis (1) |

| Soil | 4 | 0 | 0 | None | ||

| Trial 21 | Fukuoka I-2 | Fruit accessory (d) | 36 | 36 | 4 | Pantoea spp3 (4) |

| Soil | 110 | 0 | 0 | None | ||

| Trial 22 | Fukuoka J | Soil | 644 | 6 | 6 | None |

| Vegetable leaf (d) | 1080 | 15 | 4 | Pantoea spp1 (1), Pantoea spp3 (1), Cronobacter sp (1), | ||

| Vegetable root (d) | 472 | 8 | 6 | Pantoea spp3 (2) | ||

| Trial 23 | Chiba K | Vegetable leaf (d) | 90 | 6 | 5 | Pantoea spp3 (5) |

| Vegetable root (d) | 3 | 3 | 3 | Pantoea spp3 (3) | ||

| Soil | 95 | 0 | 0 | None | ||

| Trial 24 | Chiba L | Soil | 41 | 4 | 2 | Pantoea spp2 (2) |

| vegetable root (d) | 0 | 0 | 0 | None | ||

| Trial 25 | Hokkaido M | Vegetable stem (m*3) | 23 | 16 | 3 | None |

| Trial 26 | Nagano N | Vegetable stem (m) | 32 | 32 | 3 | Pantoea spp3 (2) |

|

| ||||||

| Total colony | 5186 | 797 | 91 | 91 | ||

All isolates produced a yellow pigment on TSA medium.

d: dicot.

m: monocot.

Fig. 1.

(a) Bacterial colonies on lysine-ornithine-mannitol-arginine-charcoal (LOMAC) agar medium. (b) Bacterial colonies on Tryptic soy agar medium. White arrows indicate bacterial colonies actually defined as yellow. Blue arrows indicate bacterial colonies defined as other than yellow. Samples were equally applied to each medium.

A total of 797 yellow colonies were generated on LOMAC agar (Table 3). Among these colonies, 91 were sub-cultured on TSA medium. Eighty-one out of the 91 colonies were identified as Pantoea spp. using the Api20E test. One isolate was identified as Pantoea spp. 1, 18 as Pantoea spp. 2, 61 as Pantoea spp. 3, and 1 as Pantoea spp. 4. These results demonstrated that LOMAC agar is applicable for use in the isolation of various Pantoea species, such as Pantoea spp. 1, spp. 2, spp. 3, and spp. 4.

PCR and sequencing results

In further analyses of the 81 Pantoea spp. colonies, 34 genomic DNAs were randomly selected and subjected to PCR amplification targeting the rrs gene. In 29 out of 34 genomic DNAs, PCR analyses yielded 1503-bp amplicons of the expected size.

DNA sequence analyses revealed that all of the sequences of the 20 Pantoea spp. 3 isolates were 100% identical not only to one another, but also some types of Pantoea strains, such as P. agglomerans ATCC27155, P. deleyi LMG24200 (20), and P. vagans LMG24199 (20); the rrs sequences of 8 isolates of Pantoea spp. 2 were categorized into 3 types of sequences for their highest identity, i.e., the sequences of the rrs of 5 isolates of Pantoea spp. 2 were 100% identical to P. ananatis ATCC 27966 [P. ananatis type]; the sequences of 2 Pantoea spp. 2 isolates showed the highest identity to that of Erwinia aphidicola ATCC 27992 (ranging from 99% to 100% nucleotide [nt] identity) (Erwinia type); the sequence of one Pantoea spp. 2 isolate was 100% identical to P. agglomerans ATCC 27155 (P. agglomerans type); and the sequence of one Pantoea spp. 4 isolate showed the highest identity to that of Enterobacter cloacae ATCC 13047 (99% nt identity) (E. cloacae type).

In all 34 genomic DNAs, PCR targeting the gyrB gene yielded 970-bp amplicons of the expected size. DNA sequence analyses and a BLAST search of the gyrB amplicons revealed that the gyrB sequence of Pantoea spp. 1 isolate was nearly identical to that of E. toletana (85% nucleotide [nt] identity); the gyrB sequences of 9 isolates of Pantoea spp. 2 were categorized into 3 types of sequences for their highest identity, i.e., the sequence of one isolate of Pantoea spp. 2 showed the highest identity to that of P. vagans (97% nt identity) (P. vagans type), the sequences of 6 isolates of Pantoea spp. 2 showed the highest identity to that of P. ananatis (ranging between 91 and 100% nt identity) (P. ananatis type); the sequence of one isolate of Pantoea spp. 2 showed the highest identity to that of E. rhapontici (90% nt identity) (Erwinia type), and the sequence of one isolate of Pantoea spp. 2 showed the highest identity to that of E. tasmaniensis (87% nt identity) (Erwinia type); the gyrB sequences of 23 isolates of Pantoea spp. 3 were categorized into 4 types of sequences for their highest identity, i.e., the sequences of 15 isolates of Pantoea spp. 3 showed the highest identity to that of P. agglomerans (ranging between 95 and 99% nt identity) (P. agglomerans type), the sequences of 5 isolates of Pantoea spp. 3 showed the highest identity to that of P. vagans (ranging between 97 and 100% nt identity) (P. vagans type), the sequences of 2 isolates of Pantoea spp. 3 showed the highest identity to that of P. deleyi (99% nt identity) (P. deleyi type), and the sequence of one isolate of Pantoea spp. 3 showed the highest identity to that of P. brenneri (98% nt identity) (P. brenneri type); and the sequence of one isolate of Pantoea spp. 4 showed the highest identity to that of L. adecarboxylata (95% nt identity).

Phylogeny of Pantoea isolates obtained in practical trials

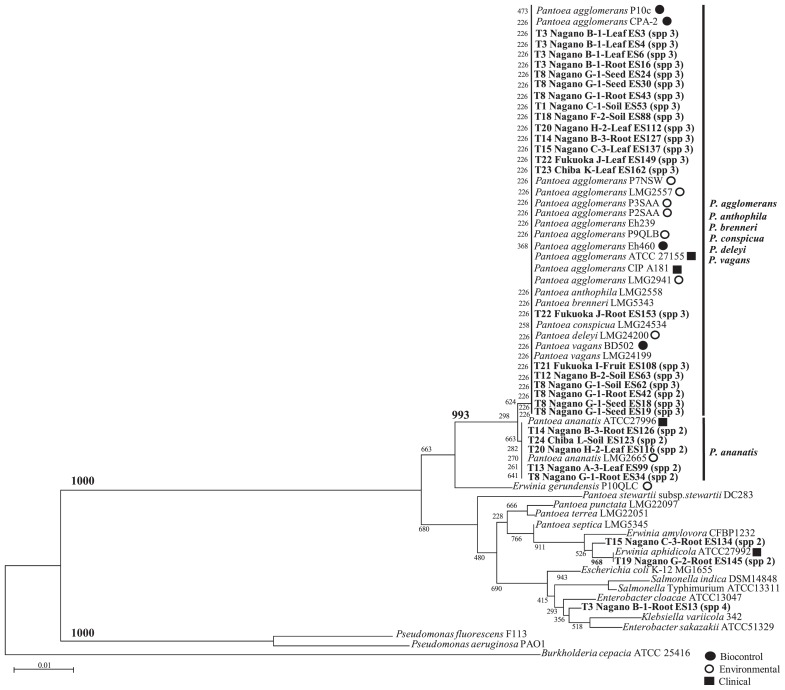

A dendrogram was calculated using the partial rrs sequences of a length appropriate for the analysis (Fig. 2). A total of 29 rrs sequences were obtained in the present study. Based on the results of phylogenetic tree analyses on 29 strains, the Pantoea strains isolated in the present study were roughly divided into 2 groups. The first group mainly consisted of Pantoea species, including P. agglomerans, P. anthophila, P. brenneri, P. deleyi, P. vagans, and P. ananatis. The second group consisted of P. stewartii, P. terrea, P. septica, P. punctata, and other Enterobacteriaceae (Fig. 2). Analyses using 16S rDNA enabled only the limited separation of strains within each Pantoea spp.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationships based on 16S ribosomal DNA sequences obtained from strains related to Pantoea spp. isolated from soil and plant samples in isolation practical trials. The dendrogram was generated using the neighbor-joining method. The numbers on the branches represent confidence intervals generated by bootstrapping with 1,000 replications. The scale bar represents 0.1 substitutions per nucleotide position. The nucleotide sequences of the isolates in Japan reported herein have been deposited in the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ databases and assigned accession numbers. The accession numbers of the referenced strains are as follows: P. agglomerans CIP181 (GenBank: FJ611803.1), P. agglomerans P7NSW (GenBank: FJ611823.1), P. agglomerans CPA-2 (GenBank: FJ611834.1), P. agglomerans P2SAA (GenBank: FJ611819.1), P. agglomerans P10c (GenBank: FJ611836.1), P. agglomerans LMG2557 (GenBank: FJ611802.1), P. agglomerans Eh239 (GenBank: FJ611826.1), P. agglomerans P3SAA (GenBank: FJ611820.1), P. agglomerans Eh460 (GenBank: FJ611828.1), P. agglomerans P9QLB (GenBank: FJ611831.1), P. agglomerans LMG2941 (GenBank: FJ611837.1), P. conspicua LMG24534 (GenBank: NR_116247.1), P. brenneri LMG5343 (GenBank: NR_116748.1), P. vagans BD502 (GenBank: DQ849043.1), P. vagans LMG24199 (GenBank: NR_116115.1), P. anthophila LMG2558 (GenBank: NR_116113.1), P. deleyi LMG24200 (GenBank: NR_116114.1), Salmonella enterica subsp. indica DSM14848 (GenBank: NR_044370.1), S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC13311 (GenBank: NR_119108.1), Enterobacter cloacae ATCC13047 (GenBank: NR_102794.2), E. sakazakii ATCC51329 (GenBank: GU122217.1), P. stewartii subsp. stewartii DC283 (GenBank: AJ311838.1), P. ananatis LMG2665 (GenBank: NR_119362.1), P. ananatis ATCC27996 (GenBank: FJ611813.1), P. septica LMG5345 (GenBank: NR_116752.1), E. gerundensis P10QLC (GenBank: FJ611850.1), E. aphidicola ATCC27992 (GenBank: FJ611858.1), E. amylovora CFBP1232 (GenBank: NR_116753.1), P. punctate LMG22097 (Japanese Pantoea) (GenBank: FJ611886.1), P. terrea LMG22051 (Japanese Pantoea) (GenBank: NR_116110.1), Escherichia coli str. K-12 substr. MG1655 (Genbank: U00096.3), Burkholderia cepacia ATCC 25416 (Genbank: AF097530.1), Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (Genbank: DQ777865.1), P. fluorescens F113 (Genbank: CP003150.1), Klebsiella variicola 342 (Genbank: CP000964.1).

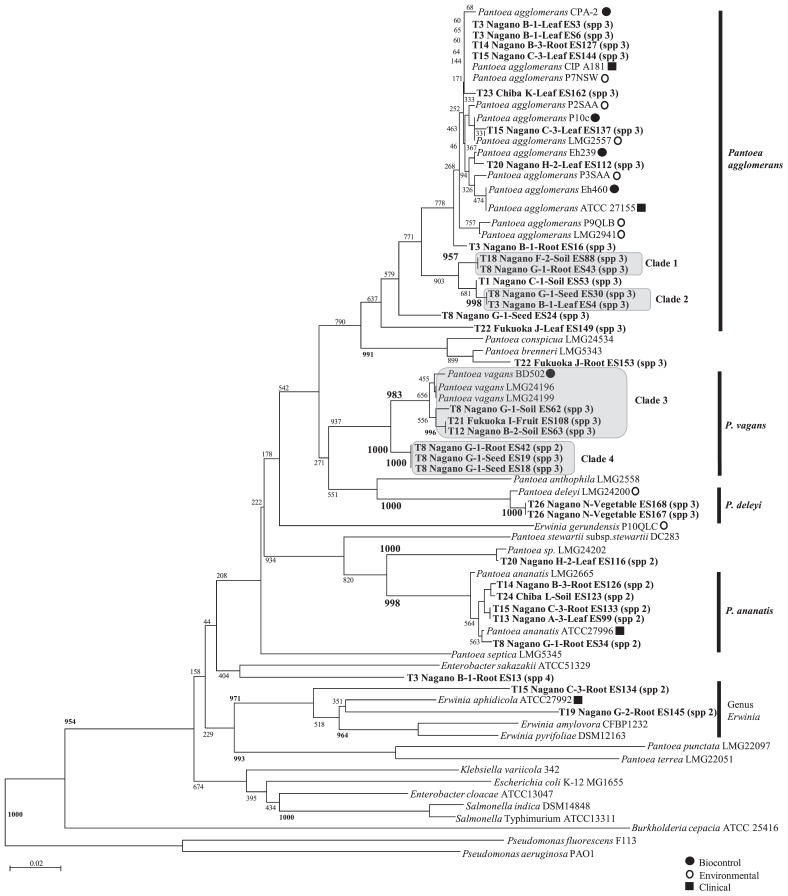

A total of 33 gyrB sequences were obtained. Based on the results of phylogenetic tree analyses for 33 strains, the Pantoea strains isolated in the present study were roughly divided into a number of groups (Fig. 3). In addition, P. agglomerans was further divided into three clades; clades 1 and 2 did not contain previously reported strains. The other clade formed a large group containing the P. agglomerans-type strain and already reported biocontrol strains (20). Similarly, P. vagans was also divided into two clades, in which clade 3 contained strain BD502, which was previously reported as a biocontrol strain (20), and clade 4 did not contain any previously reported strains. P. deleyi grouped with strain LMG24200, which was previously reported as an environmental strain (2). P. ananatis formed a large group in which all of the isolates were found to belong to Pantoea spp. 2. These results indicated that LOMAC medium is applicable to the isolation of Pantoea species exhibiting novel phylogenetic properties.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic relationships based on partial gyrB sequences obtained from strains related to Pantoea spp. isolated from soil and plant samples in isolation practical trials. The dendrogram was generated using the neighbor-joining method. The numbers on the branches represent confidence intervals generated by bootstrapping with 1,000 replications. The scale bar represents 0.1 substitutions per nucleotide position. The nucleotide sequences of the isolates in Japan reported herein have been deposited in the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ databases and assigned accession numbers. The accession numbers of the referenced strains are as follows: P. agglomerans CIP181 (GenBank: FJ617394.1), P. agglomerans P7NSW (GenBank: FJ617397.1), P. agglomerans CPA-2 (GenBank: FJ617395.1), P. agglomerans P2SAA (GenBank: FJ617388.1), P. agglomerans P10c (GenBank: FJ617389.1), P. agglomerans LMG2557 (GenBank: FJ617408.1), P. agglomerans Eh239 (GenBank: FJ617379.1), P. agglomerans P3SAA (GenBank: FJ617392.1), P. agglomerans Eh460 (GenBank: FJ617377.1), P. agglomerans P9QLB (GenBank: FJ617403.1), P. agglomerans LMG2941 (GenBank: FJ617399.1), P. conspicua LMG24534 (GenBank: EU145269.1), P. brenneri LMG5343 (GenBank: FJ617409.1), P. vagans BD502 (GenBank: EF988786.1), P. vagans LMG24196 (GenBank: EF988758.1), P. vagans LMG24199 (GenBank: EF988768.1), P. anthophila LMG2558 (GenBank: EF988812.1), P. deleyi LMG24200 (GenBank: EF988770.1), Salmonella enterica subsp. indica DSM14848 (GenBank: EU014648.1), S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC13311 (GenBank: EU014643.1), Enterobacter cloacae ATCC13047 (GenBank: EU643470.1), E. sakazakii ATCC51329 (GenBank: AY370844.1), P. stewartii subsp. stewartii DC283 (GenBank: KF482574.1), Pantoea sp. LMG24202 (GenBank: EF988778.1), P. ananatis LMG2665 (GenBank: KF482590.1), P. ananatis ATCC27996 (GenBank: FJ617369.1), P. septica LMG5345 (GenBank: FJ617422.1), E. gerundensis P10QLC (GenBank: FJ617414.1), E. aphidicola ATCC27992 (GenBank: FJ617417.1), E. amylovora CFBP1232 (GenBank: FJ617419.1), E. pyrifoliae DSM12163 (GenBank: AB242885.1), P. punctate LMG22097 (Japanese Pantoea) (GenBank: EF988805.1), P. terrea LMG22051 (Japanese Pantoea) (GenBank: EF988804.1), Escherichia coli str. K-12 substr. MG1655 (Genbank: NC_000913.3), Burkholderia cepacia ATCC 25416 (Genbank: HQ849191.1), Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (Genbank: AE004091.2), P. fluorescens F113 (Genbank: CP003150.1), Klebsiella variicola 342 (Genbank: CP000964).

Discussion

We herein developed a new semi-selective agar medium and proposed a protocol for isolating Pantoea species. On LOMAC medium, Pantoea strains formed yellow colonies; however, some Gram-negative bacteria from environmental samples also formed yellow colonies. It is conceivable that under the same substrate availability conditions, strains other than Pantoea will form colonies of the same color. However, many Pantoea strains are known to produce a yellow pigment (5, 8). When yellow colonies isolated on LOMAC medium were passaged on TSA medium, the majority of Pantoea strains in the present study produced a yellow pigment on TSA. This result indicates that the diagnostic accuracy of the procedure may be improved by eliminating bacteria that do not produce a yellow pigment on TSA. The efficient recovery of Pantoea strains on LOMAC medium suggests its applicability to investigations on the ecology of these species in the environment.

In practical trials, many Pantoea strains were isolated from plants. Pantoea is a plant-derived bacterium known to exist as an endophyte. As reported previously (21, 22), the inside of plants is considered to be suitable for the survival of Pantoea species, such as P. vagans. Endophytic organisms, such as Pantoea, live inside plants without causing damage (17). In addition, endophytic Pantoea may promote plant growth by accelerating processes including nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, siderophore secretion, and biocontrol (13, 17). Different Pantoea species were detected in different parts of the same plant in the present study. For example, 6 strains of P. ananatis were isolated from the roots of crops (dicot) in trial 8, but were not detected in seeds. This result suggests that the role of parasitism differs among species and also that each Pantoea species may play a different role inside plants. Notably, P. deleyi was detected in trial 26 in the stem of a vegetable plant. Although limited information is currently available on P. deleyi, this species has been isolated from bacterial plaques and dead portions of eucalyptus (2). However, there were no dead portions in the stems of the vegetables examined in this trial, and, therefore, the function of P. deleyi in these plants remains unclear. This species is predicted to be more closely related to P. vagans based on the results of gyrB phylogenetic tree analyses. Future studies will provide more information on this strain.

Pantoea strains were also isolated from 4 out of 24 spots of soil samples (16.7%) and from 15 out of 19 plant types (78.9%) with a large difference in detection rates. The population of Pantoea strains varies among crops, weeds, vegetables, fruits and soils in the environment in Japan.

Attempts to isolate Pantoea strains in 11 trials using samples from Nagano and 1 trial using samples from Hokkaido were unsuccessful because no colonies with a yellow color were observed on LOMAC medium. Among the non-yellow colonies, 7 were randomly selected and subjected to genetic analyses. As expected, gyrB sequencing revealed that these 7 colonies were not Pantoea species. In consideration of this result as well as recovery efficiency from soils, the protocol used in the present study is suitable for isolating Pantoea species.

In conclusion, we herein developed a new semi-selective medium known as LOMAC and established a protocol for isolating Pantoea species with high test efficiency. We detected Pantoea strains in samples of plants and soils from Japan using LOMAC even when Pantoea species were present at lower densities than non-target bacteria. Therefore, LOMAC medium enables the screening of Pantoea species from environmental sources and may be useful in future studies.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Jumonji University and Kohjin Bio Co., Ltd.

References

- 1.Azegami K. Isolation of Pantoea spp. from weeds and their pathogenicity on onion and welsh onion. Microbial Genetic Resource Search Collection Report. 2016;25:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brady C.L., Venter S.N., Cleenwerck I., Engelbeen K., Vancanneyt M., Swings J., Coutinho T.A. Pantoea vagans sp. nov., Pantoea eucalypti sp. nov., Pantoea deleyi sp. nov. and Pantoea anthophila sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:2339–2345. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.009241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brady C.L., Venter S.N., Cleenwerck I., Vandemeulebroecke K., De Vos P., Coutinho T.A. Transfer of Pantoea citrea, Pantoea punctata and Pantoea terrea to the genus Tatumella emend. as Tatumella citrea comb. nov., Tatumella punctata comb. nov. and Tatumella terrea comb. nov. and description of Tatumella morbirosei sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:484–494. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.012070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bucher C., von Graevenitz A. Evaluation of three differential media for detection of Enterobacter agglomerans (Erwinia herbicola) J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:1164–1166. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.6.1164-1166.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dutkiewicz J., Mackiewicz B., Lemieszek M.K., Golec M., Milanowski J. Pantoea agglomerans: a mysterious bacterium of evil and good. Part I. Deleterious effects: Dust-borne endotoxins and allergens—focus on cotton dust. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2015;22:576–588. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1185757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutkiewicz J., Mackiewicz B., Lemieszek M.K., Golec M., Milanowski J. Pantoea agglomerans: a mysterious bacterium of evil and good. Part IV. Beneficial effects. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016;23:206–222. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1203879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutta B., Gitaitis R., Barman A., Avci U., Marasigan K., Srinivasan R. Interactions between Frankliniella fusca and Pantoea ananatis in the center rot epidemic of onion (Allium cepa) Phytopathology. 2016;106:956–962. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-12-15-0340-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farmer J.J., III . Enterobacteriaceae: itroduction and ientification. In: Murray P.R., Baron E.J., Pfaller M.A., Tenover F.C., Yolken R.H., editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 7th ed. American Society for Microbiology; Washington, D.C: 1999. pp. 442–458. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goszczynska T., Moloto V.M., Venter S.N., Coutinho T.A. Isoration and identification of Pantoea ananatis from onion seed in South Africa. Seed Sci Technol. 2006;34:655–688. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goszczynska T., Venter S.N., Coutinho T.A. PA 20, a semi-selective medium for isolation and enumeration of Pantoea ananatis. J Microbiol Methods. 2006;64:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kageyama B., Nakae M., Yagi S., Sonoyama T. Pantoea punctata sp. nov., Pantoea citrea sp. nov., and Pantoea terrea sp. nov. isolated from fruit and soil samples. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:203–210. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-2-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasugai H., Ishiyama J., Imai I., et al. A case report of far advanced gastric cancer with multiple liver metastasis (H3) treated with transarterial intermittent chemotherapy and intradermal administration of low molecular lipopolysaccharide (LPSp) extracted from Pantoea agglomerans. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1995;22:1690–1693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ker K., Seguin P., Driscoll B.T., Fyles J.W., Smith D.L. Switchgrass establishment and seeding year production can be improved by inoculation with rhizosphere endophytes. Biomass Bioenergy. 2012;47:295–301. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malboobi M.A., Behbahani M., Madani H., Owlia P., Deljou A., Yakhchali B., Moradi M., Hassanabadi H. Performance evaluation of potent phosphate solubilizing bacteria in potato rhizosphere. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;25:1479–1484. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malboobi M.A., Owlia P., Behbahani M., Sarokhani E., Moradi S., Yakhchali B., Deljou A., Heravi K.M. Solubilization of organic and inorganic phosphates by three highly efficient soil bacterial isolates. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;25:1471–1477. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medrano E.G., Bell A.A. Genome sequence of Pantoea ananatis strain CFH 7-1, which is associated with a vector-borne cotton fruit disease. Genome Announc. 2015;3:e01029–15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01029-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mei C., Flinn B.S. The use of beneficial microbial endophytes for plant biomass and stress tolerance improvement. Recent Pat Biotechnol. 2010;4:81–95. doi: 10.2174/187220810790069523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller A.M., Figueiredo J.E., Linde G.A., Colauto N.B., Paccola-Meirelles L.D. Characterization of the inaA gene and expression of ice nucleation phenotype in Pantoea ananatis isolates from maize white spot disease. Genet Mol Res. 2016;15:15017863. doi: 10.4238/gmr.15017863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perrière G., Gouy M. WWW-query: an on-line retrieval system for biological sequence banks. Biochimie. 1996;78:364–369. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)84768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rezzonico F., Smits T.H., Montesinos E., Frey J.E., Duffy B. Genotypic comparison of Pantoea agglomerans plant and clinical strains. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:204. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smits T.H., Rezzonico F., Kamber T., Goesmann A., Ishimaru C.A., Stockwell V.O., Frey J.E., Duffy B. Genome sequence of the biocontrol agent Pantoea vagans strain C9-1. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:6486–6487. doi: 10.1128/JB.01122-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smits T.H., Rezzonico F., Kamber T., Blom J., Goesmann A., Ishimaru C.A., Frey J.E., Stockwell V.O., Duffy B. Metabolic versatility and antibacterial metabolite biosynthesis are distinguishing genomic features of the fire blight antagonist Pantoea vagans C9-1. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Son H.J., Park G.T., Cha M.S., Heo M.S. Solubilization of insoluble inorganic phosphates by a novel salt- and pH-tolerant Pantoea agglomerans R-42 isolated from soybean rhizosphere. Bioresour Technol. 2006;97:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sulbarán M., Pérez E., Ball M.M., Bahsas A., Yarzábal L.A. Characterization of the mineral phosphate-solubilizing activity of Pantoea agglomerans MMB051 isolated from an iron-rich soil in southeastern Venezuela (Bolívar State) Curr Microbiol. 2009;58:378–383. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walterson A.M., Stavrinides J. Pantoea: insights into a highly versatile and diverse genus within the Enterobacteriaceae. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2015;39:968–984. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuv027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]