Abstract

Traditional mediation analysis assumes that a study population is homogeneous and the mediation effect is constant over time, which may not hold in some applications. Motivated by smoking cessation data, we propose a latent class dynamic mediation model that explicitly accounts for the fact that the study population may consist of different subgroups and the mediation effect may vary over time. We use a proportional odds model to accommodate the subject heterogeneities and identify latent subgroups. Conditional on the subgroups, we employ a Bayesian hierarchical nonparametric time-varying coefficient model to capture the time-varying mediation process, while allowing each subgroup to have its individual dynamic mediation process. A simulation study shows that the proposed method has good performance in estimating the mediation effect. We illustrate the proposed methodology by applying it to analyze smoking cessation data.

Keywords: Bayesian inference, dynamic mediation, latent class, time-varying coefficients

1. Introduction

Mediation analysis is widely used in psychosocial and behavioral research to understand whether the effect of an exposure variable X on an outcome variable Y is mediated through a third variable known as the mediator variable M. For example, suppose that a prevention program shows a treatment effect of decreasing the patient’s symptoms of depression; the investigator may be interested in understanding whether the prevention program achieves that treatment effect by improving the patient’s coping skills. Assuming that the relationship (or path) among these variables is causal, Baron and Kenny (1986) laid out the basic statistical procedure for estimating the mediation effect based on two regression models: regressing Y on M and X, and regressing M on X. Then, the mediation effect is defined as the product of the regression coefficient of M in the first regression, with the regression coefficient of X in the second regression. Baron and Kenny’s procedures have been extended in various ways to handle more complicated cases, such as longitudinal and correlated data (Gollob & Reichardt 1991; Cole & Maxwell 2003), multiple mediators (Brown 1997; West & Aiken 1997; MacKinnon 2000; Preacher & Hayes 2008), latent variables (Hoyle & Kenny 1999; Bollen 2002; Lau & Cheung 2010), and categorical data (Foshee et al. 1998; MacKinnon, Warsi, & Dwyer, 1995; Hayes & Preacher 2014). MacKinnon et al. (2002) provided a comprehensive review of methods for statistical mediation analysis.

Researchers have also investigated mediation analysis from the viewpoint of causal inference using a framework of counterfactual outcomes (Rubin 1974, 1990). After initial definitions and discussions of direct and indirect causal effects (Robins & Greenland 1992; Pearl 2001), a number of articles on this topic have been published that concern different identification strategies for direct and indirect effects under various assumptions, including models with practical consideration of predictor-outcome confounders, mediator-outcome confounders, predictor-mediator interactions and nonlinearities. (Robins 2003; Rubin 2004; Petersen et al., 2006; Joffe et al., 2007; Ten Have et al., 2004, 2007; Imai et al., 2010; VanderWeele and Vansteelandt 2010; Hafeman & VanderWeele 2011; Valeri & VanderWeele 2013). More recently, Bind et al. (2016) also formalized a causal framework with potential outcomes for the mediation effect in longitudinal studies. Theories for mediation analysis in a decision theoretic framework without counterfactuals were also developed (Didelez et al. 2006; Geneletti 2007). While most of this literature has focused on conventional frequentist approaches, some researchers have proposed Bayesian approaches to estimate the natural direct and indirect effects (Yuan & MacKinnon, 2009; Daniels et al. 2012).

Our research is motivated by smoking cessation data collected as part of a randomized clinical trial to examine the effectiveness of an individually tailored relapse prevention program for female smokers (Wetter et al., 2011). A total of 302 female participants who were interested in quitting smoking were recruited from the Seattle metropolitan area. The participants included in the study were females aged 18 to 70 years who had smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day for at least the past year, had an expired breath carbon monoxide level of ≥ 10 parts per million; and were able to speak, read, and write in English. Exclusion criteria were the regular use of tobacco products other than cigarettes, an active substance abuse disorder, current psychiatric disorder, current bupropion use, and contraindications for nicotine replacement therapy.

Longitudinal data were collected from participants by using a handheld personal computer (Casio model E-10). In this analysis, we focus on the data collected on the first day post smoking cessation, which include 2152 observations from 293 participants. The number of assessments for the participants range from 1 to 19, with a mean of 7.3. About 90% of the assessments were completed between 6:00 AM and 9:30 PM. One research objective is to estimate the mediation effect of positive smoking outcome expectancies (i.e., M) on the effect of a negative mood (i.e., X) on smoking urges (i.e., Y), where positive smoking outcome expectancies refer to a smoker’s belief that smoking a cigarette will result in positive consequences, e.g., reduce anxiety or enhance enjoyment. The three variables are assessed using multi-item questionnaires. Previous research shows that negative mood is one critical post-cessation precipitant of lapse/relapse, and has been associated with an increased urge to smoke among smokers who are attempting to quit (Shiyko et al., 2012). Some evidence suggests that positive smoking outcome expectancies may be triggered by internal states such as negative mood (Baker et al., 2004; Kirchner & Sayette, 2007), and are associated with smoking urges (Brandon, Wetter, & Baker, 1996).

Two issues make this mediation analysis challenging. First, the study population is heterogeneous and may consist of several subgroups. It has been long recognized that smoking is a complex behavior (Green, 1979; Sullivan & Kendler, 1999; Javis, 2004; Husten et al.1998). The population of smokers is heterogeneous and consists of different subgroups (Dijkstra & De Vries 2000; Poland et al. 2000; Norman et al., 2000; Anatchkova et al., 2006; Velicer et al. 2007). For example, among hardcore smokers who have little to no intention of quitting, Bommelé et al. (2015) identified three subgroups: receptive smokers (36%) who perceive many disadvantages of smoking and advantages of quitting; ambivalent smokers (59%) who are undecided about quitting, and resistant smokers (5%) who see few disadvantages of smoking and few advantages of quitting. Acknowledging patient subgroups in data analysis is the key to precision medicine.

The second challenge of this mediation analysis is that it is well known that smoking is a time-dependent behavior (Schneider, et al., 2005; Reitzel, et al., 2001). Smokers often experience high smoking urges and negative moods during the afternoon and evening, and lower smoking urges in the morning. In other words, the mediation effect of positive smoking outcome expectancies is expected to vary over time. Huang and Yuan (2016) called such a time-varying mediation process a dynamic mediation effect. Almost all existing mediation methods, however, assume that the mediation process is time-invariant or static, making them unsuitable for analyzing the smoking data.

In this paper, we develop a latent class dynamic mediation model that accounts for both the subject heterogeneities and time-varying (or dynamic) nature of the mediation process, as shown in Figure 1. Specifically, we assume the heterogeneity of subjects is captured by a latent variable that defines different subgroups, and the subgroups can be identified by base-line covariates using a proportional odds model. Conditional on the subgroups, we employ a Bayesian hierarchical time-varying coefficient model to capture the dynamic nature of the mediation process, while allowing each subgroup to have its individual dynamic mediation process. To obtain robust inference, we use a penalized spline to model the subgroup-specific mediation process without imposing strong parametric assumptions. The proposed method generalizes the method of Lu & Song (2012) by accommodating the mediation process and accounting for heterogeneous longitudinal data.

Figure 1:

Directed graph of latent class dynamic mediation model for intensive longitudinal data. Boxes represent observed variables: Z = (Z1, …, Zp)T are p-dimensional covariates; Xt, Mt, and Yt are the predictor, mediator and outcome at time t. In the smoking cessation example, they are the measured levels of negative mood, positive smoking outcome expectancies, and smoking urge, respectively. Circles represent unobserved constructs that underlie the latent classes and heterogeneity of the observed variables: C represents latent class membership; αl(t), γl(t), βl(t), δl(t), τl(t) are the class-specific time-varying parameters that are related to the mediation process, conditional on the latent class C = l; , , , are the class-specific time-invariant variance components that are related to the mediation process, conditional on the latent class C = l. The probability of belonging to a latent class is modeled as a function of baseline covariates Z.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. In Section 2, we present our latent class dynamic mediation model and provide its causal interpretation. Section 3 describes the procedure for Bayesian model estimation. Section 4 examines the performance of the proposed method through simulation studies. Section 5 applies the new method to the smoking cessation data, and Section 6 provides concluding remarks.

2. Methods

2.1. Latent class dynamic mediation model

Suppose a longitudinal study is designed to collect repeated measurements from n subjects. Let i = 1,…n index subject, j = 1,…mi index repeated measurement. Let Xij, Yij, Mij denote the predictor (or exposure variable), outcome and mediator variables, respectively, measured at time tij from the ith subject. In our smoking cessation data, X is negative mood, Y is smoking urge, and M is positive smoking outcome expectancies. We assume that there are L subgroups in the study population and let Ci = l denote the unobserved latent class (or subgroup) membership of the ith subject, where l = 1, 2, …, L. For ease of description, we use the terms “class” and “subgroup” exchangeably. We discuss how to determine the value of L later.

Given the latent subgroup membership for each subject, we model the mediation process as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where γl(tij), αl(tij), δl(tij), βl(tij) and τl(tij) are class-specific, time-varying regression coefficients that are smooth functions of time. Specifically, αl(tij) quantifies how the relationship between the mediator variable M and the predictor variable X varies over time in the lth subgroup; and βl(tij) measures how the relationship between the outcome variable Y and the mediator variable M, after adjusting for the predictor variable X, varies over time in the lth subgroup. Random intercepts ξi and ζi are used to account for the correlation among repeated measures within the same subject. We assume that residuals ϵij and ηij follow normal distributions and . Here, we allow different subgroups to have different residual variances.

Without imposing any specific parametric structure, we model γl(tij), αl(tij), δl(tij), βl(tij) and τl(tij) nonparametrically using a penalized spline with quadratic basis:

One advantage of using the penalized spline to model the time-varying coefficients is that, after plugging the above equations into the mediation models (1)-(4), the resulting model takes a familiar form of a linear mixed model or Bayesian hierarchical model (Eilers & Marx, 1996; Ruppert et al., 2003), which greatly simplifies the model fitting and estimation. As an example, if we plug αl(t) and γl(t) into equation (1), we obtain the following linear mixed

Similarly, mediation equation (2) can also be represented as a linear mixed model.

We now turn to the model of the latent class. Let Zi = (1, Z1i, Z2i, …, Zpi)′ denote a vector of p baseline covariates of the ith subject. We model the latent class membership Ci using a proportional odds model as follows,

| (5) |

where ω01 ≤ ω02 ≤ ⋯ ≥ ω0l. Letting πl(Zi) = Pr(Ci = l∣Zi), the proportional odds model can be re-expressed as

| (6) |

Under the above model, the latent class memberships are identifiable based on two assumptions: 1) the baseline covariates, Z, are associated with the latent class membership; 2) the mediation effect is the same within the latent class, but different across latent classes. In other words, the latent classes are identified using two pieces of information simultaneously, namely the baseline covariates and the similarity/dissimilarity of mediation effects between subjects, through the joint likelihood of C, M and Y.

The number of latent classes (i.e., the value of L) is chosen based on a cetain information criterion, e.g. the deviance information criterion (DIC; Spiegelhalter et al., 2002), such that the resulting model has the best goodness-of-fit. In practice, we can start from L = 1 and progressively increase the value of L until the DIC first starts to increase, and then select the value of L that yields the smallest DIC as the number of latent classes.

2.2. Mediation effect and its causal interpretation

To define the causal mediation effect, we follow the notations in the counterfactual outcome framework (Rubin, 1974, 1978; Robins & Greenland, 1992; Pearl, 2001). Let Mi(x) denote the subject’s counterfactual value for M if exposure X was set to x, and let Yi(x, m) denote the subject’s counterfactual outcome if exposure X was set to x and mediator M was set to m, through some intervention or manipulation. As our primary interest is to estimate subgroup-specific mediation effect, our definition of average causal mediation effect (ACME) is conditioning on the latent class membership, which is different from most existing work (Robins and Greenland 1992; Pearl 2001; Imai et al., 2010). Specifically, we define the subgroup-specific average causal mediation effect (S-ACME) at time t as

where x* = x + 1 indicates the one unit increase from the reference value x for the exposure variable. Following the work by Pearl (2001), Imai (2010) and Bind et al. (2016), we delineate the assumptions such that the estimator of αl(t)βl(t) can be interpreted as an S-ACME estimator.

Assumption 1 (Correct latent class): The proportional odds model used to identify the latent class membership is correctly specified.

Assumption 2 (Latent class sequential ignorability):

It is also assumed that Pr(Xij = x) > 0 and Pr(Mij (x) = m∣xij = x) > 0 for all possible values of x and m.

Assumption 2 includes two conditional independences: (1) ignorability of exposure, which says that given the latent class membership and baseline covariates, the potential mediator and potential outcome are statistically independent of the level of exposure; and (2) ignorability of mediator, which says the potential outcome is statistically independent of the potential mediator given the latent class membership, the observed exposure, and baseline covariates. The ignorability of exposure can be achieved by randomization, but not guaranteed in observational studies. The ignorability of the mediator is more stringent, and may not even hold in randomized studies.

The latent class sequential ignorability (Assumption 2) is a weaker assumption than the sequentially ignorable assumption described by Imai et al. (2010a & 2010b) as the latter requires that there is no unmeasured pre-exposure confounders. In contrast, the latent class sequential ignorablity assumption still holds when there are unmeasured pre-exposure confounders if the counfounders are explained by the latent class membership. The tradeoff is that we here require that the latent class model is correctly specified (Assumption 1).

Given Assumptions 1 & 2, we have that

and

where l = 1,…,L. Thus, the S-ACME at time t in the proposed latent class dynamic mediation model is identified and given by αl(t)βl(t). With some simple linear algebra, we can also see that for all possible values of x and x′, under Assumptions 1 & 2. In the literature, such equality is called the assumption of no interaction between the exposure and the mediator (Robins and Richardson 2010; Imai et al. 2010a & b), which means that the mediation effect does not depend on the value of the exposure, i.e., the mediation effect is the same at all possible values of the exposure. In the proposed latent class dynamic mediation model, this assumption is implied by the model assumption in equation (1)-(5). In many studies, it may be unrealistic to make such an assumption. This assumption can be relaxed by adding the product term of X and M in equation (2) to allow exposure-mediator interaction (Kraemer et al. 2008; Valeri author & VanderWeele 2013; Bind et al. 2016).

3. Bayesian estimation

It is well known that statistical inference for a mediation effect, in particular estimation of the confidence interval, is not straightforward because the sampling distribution of the estimate of the mediation effect is skewed and does not follow a simple parametric distribution, even under large samples (MacKinnon et al., 2002). Each of the regression coefficients αl(t) and βl(t) may be asymptotically normal; however, their product is skewed. As we model αl(t) and βl(t) nonparametrically, inference for the dynamic mediation effect αl(t)βl(t) is more challenging. The fact that the latent class membership Ci is not observable further complicates the inference. We tackle this problem using a Bayesian approach. Yuan and MacKinnon (2009) showed that the Bayesian method is particularly attractive for mediation analysis because the confidence interval and standard error can be easily derived from posterior samples. In addition, under the Bayesian paradigm, the unobserved latent class membership is naturally regarded as an unknown parameter, which can be conveniently sampled using the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method.

To fit the proposed model, we assign independent vague priors to model the parameters. Specifically, for variance components, we assign independent inverse gamma distributions with a shape parameter of 10−3 and scale parameter of 10−3. For the regression parameters of the mediation model, we assign independent normal distributions N(0, 104). For the regression parameters of the latent class model, following Garrett and Zeger (2000) and Elliott et al. (2005), we assign them independent normal distributions N(0, 9/4), which is a proper prior centered at 1/L and relatively flat after the logit transformation. We choose vague priors to represent the general case that there is little prior information on model parameters and we want the data to speak for themselves. We use a Metropolis-within-Gibbs algorithm by Roberts and Rosenthal (2008) to sample the conditional posterior distributions of the parameters. Details are provided in the Appendix.

4. Numerical studies

We conducted a simulation study to evaluate the performance of the proposed method. We considered three baseline covariates Z1, Z2 and Z3, where Z1 is a binary variable generated from a Bernoulli distribution, with probability 0.5, and Z2, Z3 ~ N(0, 5). We considered scenarios with 2 subgroups or 3 subgroups. When there were 2 subgroups, we set ω01 = 0, ω1 = ω2 = ω3 = 1; and when there were 3 subgroups, we set ω01 = −3, ω02 = 3, ω1 = −1, ω2 = ω3 = 1, such that the number of subjects is similar in subgroups. We simulated the predictor Xij from N(0, 1), and then simulated mediator Mij based on equation (1), and outcome Yij based on equation (2), under four different shapes of mediation effect αl(t)βl(t): a flat curve, valley curve, hump curve and decayed curve. Table 1 provides the function forms for generating these curves. For simplicity, in equations (1) to (2), we set the values of the intercepts as γl(t) = δl(t) = 1, 3, 5 for l = 1, 2, 3, respectively. We set the first-level residual variances , and the second-level random error variances for l = 1, 2, 3.

Table 1:

Four different shapes of αl(t) and βl(t) considered in the simulation study.

|

αl(t),βl(t) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Shape | Shape Subgroup 1 (l = 1) | Subgroup 2 (l = 2) | Subgroup 3 (l = 3) |

| Flat | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Valley | |||

| Hump | 3x + exp [− {3(x − 0.5)}2] | 3x + 3 exp [− {3(x − 0.5)}2] | 3x + 5 exp [− {3(x − 0.5)}2] |

| Decay | −3 + 5 exp (−x0.5) | −3 + 6 exp (−x0.5) | −3 + 7 exp (−x0.5) |

We took the total number of subjects as n = 50 when there are 2 subgroups, and n = 100 when there are 3 subgroups. We assumed mi = 10 repeated measurements that are equally spaced in the standardized time interval [0, 1]. We compared the proposed latent class dynamic mediation model (LC-DMM) to the conventional static mediation model (SMM), which assumes that the mediation effect is time invariant and subjects are homogeneous, and a simple dynamic mediation model (DMM) that allows the mediation effect to be time-varying but does not account for the subject heterogeneity. As far as we aware, the DMM is also novel. We used K = 9 knots with quadratic penalized spline for both the proposed latent class dynamic mediation model and the simple dynamic mediation model. A total of 1,000 simulations under each simulation configuration were conducted. One practical challenge for the penalized spline method is to determine the location and the number of knots. While too few knots may lead to underfitting of the data, too many knots may lead to overfitting. Ruppert (2002) suggested that 10 knots are adequate for approximating monotonic or single-mode functions, and around 20 knots are adequate for more complicated functions, when knots are equally spaced or located at the percentiles of the observed data. The penalized spline method is robust to overfitting, because of the use of the roughness penalty, and prior specification of spline regression parameters (Jullion & Lambert 2007). In our simulation study, the results are very similar when the number of (equally spaced) knots is set as 6, 9, 12 or 20. In Table 2 and 3, we presented the results of simulation studies using 9 equally spaced knots and noninformative inverse gamma priors for the variance of the spline coefficients with a shape parameter of 10−3 and scale parameter of 10−3.

Table 2:

The mean square error (MSE), relative bias (RB) and coverage probability (CP) of 95% credible interval for the estimates of the mediation effects at time points t = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 and 0.8 under the conventional static mediation model (SMM), the simple dynamic mediation model (DMM), the proposed latent class dynamic mediation model (LC-DMM) when there are 2 subgroups.

| Subgroup 1 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMM |

DMM |

LC-DMM |

||||||||

| Shape | t | MSE | RB | CP(%) | MSE | RB | CP(%) | MSE | RB | CP(%) |

| Flat | 0.2 | 2.50 | −0.16 | 0.00 | 2.42 | −0.17 | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.00 | 93.0 |

| 0.4 | 2.50 | −0.16 | 0.00 | 2.35 | −0.16 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 96.5 | |

| 0.6 | 2.50 | −0.16 | 0.00 | 2.32 | −0.16 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 97.0 | |

| 0.8 | 2.50 | −0.16 | 0.00 | 2.31 | −0.16 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 96.0 | |

| Valley | 0.2 | 3.63 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 75.0 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 95.3 |

| 0.4 | 1.75 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.08 | −0.07 | 68.0 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 95.9 | |

| 0.6 | 1.84 | −0.18 | 0.00 | 0.79 | −0.17 | 6.00 | 0.03 | −0.00 | 95.9 | |

| 0.8 | 5.61 | −0.29 | 0.00 | 2.10 | −0.20 | 1.00 | 0.04 | −0.00 | 97.7 | |

| Hump | 0.2 | 17.73 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 0.33 | −0.12 | 63.0 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 96.0 |

| 0.4 | 9.90 | −0.06 | 0.07 | 18.50 | −0.27 | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 95.3 | |

| 0.6 | 35.77 | −0.29 | 0.00 | 27.33 | −0.25 | 0.00 | 0.12 | −0.00 | 94.5 | |

| 0.8 | 7.95 | −0.28 | 0.00 | 1.71 | −0.08 | 42.0 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 97.0 | |

| Decay | 0.2 | 14.93 | 0.73 | 0.05 | 2.65 | −0.09 | 18.0 | 0.17 | −0.01 | 92.0 |

| 0.4 | 7.69 | −0.05 | 0.20 | 3.12 | −0.08 | 15.0 | 0.12 | −0.01 | 97.0 | |

| 0.6 | 28.37 | −0.24 | 0.00 | 3.13 | −0.08 | 15.0 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 96.0 | |

| 0.8 | 9.72 | −0.25 | 0.00 | 3.58 | −0.09 | 16.0 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 95.0 | |

| Subgroup 2 |

||||||||||

| SMM |

DMM |

LC-DMM |

||||||||

| Shape | t | MSE | RB | CP(%) | MSE | RB | CP(%) | MSE | RB | CP(%) |

| Flat | 0.2 | 13.07 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 12.50 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.00 | 97.0 |

| 0.4 | 13.07 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 12.63 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.00 | 96.0 | |

| 0.6 | 13.07 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 12.70 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.00 | 96.0 | |

| 0.8 | 13.07 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 12.75 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.00 | 97.0 | |

| Valley | 0.2 | 10.02 | 1.38 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 10.0 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 96.5 |

| 0.4 | 8.84 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 95.3 | |

| 0.6 | 7.55 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 2.49 | 0.59 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 95.9 | |

| 0.8 | 6.85 | 0.55 | 0.10 | 5.09 | 0.68 | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 93.6 | |

| Hump | 0.2 | 36.24 | 3.79 | 0.00 | 4.89 | 2.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 96.0 |

| 0.4 | 18.12 | 1.12 | 0.00 | 47.77 | 1.53 | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.00 | 94.7 | |

| 0.6 | 8.46 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 67.16 | 1.10 | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.00 | 95.3 | |

| 0.8 | 6.66 | 0.47 | 0.07 | 22.63 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 94.6 | |

| Decay | 0.2 | 50.12 | 3.09 | 0.00 | 32.44 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 0.29 | −0.01 | 96.0 |

| 0.4 | 27.61 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 38.60 | 0.53 | 0.00 | 0.22 | −0.01 | 96.5 | |

| 0.6 | 15.40 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 44.12 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 96.0 | |

| 0.8 | 10.96 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 46.83 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 96.5 | |

Table 3:

The mean square error (MSE), relative bias (RB) and coverage probability (CP) of 95% credible interval for the estimates of the mediation effects at time points t = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 and 0.8 under the conventional static mediation model (SMM), the simple dynamic mediation model (DMM) and the proposed latent class dynamic mediation model (LC-DMM) when there are 3 subgroups.

| Subgroup 1 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMM |

DMM |

LC-DMM |

||||||||

| Shape | t | MSE | RB | CP(%) | MSE | RB | CP(%) | MSE | RB | CP(%) |

| Flat | 0.2 | 86.57 | 2.32 | 0.00 | 88.77 | 2.35 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.00 | 97.0 |

| 0.4 | 86.57 | 2.32 | 0.00 | 89.08 | 2.35 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 95.5 | |

| 0.6 | 86.57 | 2.32 | 0.00 | 89.52 | 2.36 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 96.0 | |

| 0.8 | 86.57 | 2.32 | 0.00 | 90.16 | 2.37 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 95.5 | |

| Valley | 0.2 | 56.58 | 3.00 | 0.00 | 1.35 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 97.5 |

| 0.4 | 54.14 | 2.39 | 0.00 | 5.60 | 1.24 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 96.0 | |

| 0.6 | 50.99 | 1.90 | 0.00 | 16.55 | 1.54 | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 96.0 | |

| 0.8 | 48.59 | 1.65 | 0.00 | 34.76 | 1.78 | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 97.0 | |

| Hump | 0.2 | 143.91 | 7.44 | 0.00 | 35.04 | 5.40 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 91.0 |

| 0.4 | 105.96 | 2.67 | 0.00 | 363.99 | 4.26 | 0.00 | 0.08 | −0.02 | 91.0 | |

| 0.6 | 78.76 | 1.79 | 0.00 | 479.9 | 2.97 | 0.00 | 0.13 | −0.02 | 92.5 | |

| 0.8 | 71.74 | 1.55 | 0.00 | 128.26 | 1.40 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.05 | 92.5 | |

| Decay | 0.2 | 196.61 | 6.08 | 0.00 | 208.53 | 1.52 | 0.00 | 0.19 | −0.01 | 93.5 |

| 0.4 | 149.45 | 2.36 | 0.00 | 241.88 | 1.34 | 0.00 | 0.16 | −0.00 | 93.5 | |

| 0.6 | 117.21 | 1.63 | 0.00 | 267.78 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 95.5 | |

| 0.8 | 103.49 | 1.41 | 0.00 | 284.26 | 1.18 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 95.0 | |

| Subgroup 2 |

||||||||||

| SMM |

DMM |

LC-DMM |

||||||||

| Shape | t | MSE | RB | CP(%) | MSE | RB | CP(%) | MSE | RB | CP(%) |

| Flat | 0.2 | 18.74 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 19.77 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 97.5 |

| 0.4 | 18.74 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 19.90 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.10 | −0.00 | 96.5 | |

| 0.6 | 18.74 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 20.11 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 96.0 | |

| 0.8 | 18.74 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 20.42 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 97.5 | |

| Valley | 0.2 | 20.38 | 1.49 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 2.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 96.5 |

| 0.4 | 15.42 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 1.43 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 95.0 | |

| 0.6 | 10.55 | 0.39 | 0.002 | 2.82 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 95.5 | |

| 0.8 | 9.50 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 5.22 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.09 | −0.01 | 95.5 | |

| Hump | 0.2 | 90.63 | 2.35 | 0.00 | 10.82 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 96.5 |

| 0.4 | 14.39 | 0.61 | 0.00 | 65.42 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 93.5 | |

| 0.6 | 8.32 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 76.37 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 94.5 | |

| 0.8 | 14.87 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 30.31 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 92.5 | |

| Decay | 0.2 | 102.09 | 1.94 | 0.00 | 53.34 | 0.44 | 0.00 | 0.30 | −0.01 | 96.5 |

| 0.4 | 30.77 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 60.31 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.24 | −0.01 | 96.0 | |

| 0.6 | 18.65 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 66.53 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 95.5 | |

| 0.8 | 18.96 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 69.59 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 97.5 | |

| Subgroup 3 |

||||||||||

| SMM |

DMM |

LC-DMM |

||||||||

| Shape | t | MSE | RB | CP(%) | MSE | RB | CP(%) | MSE | RB | CP(%) |

| Flat | 0.2 | 7.77 | −0.17 | 0.00 | 7.17 | −0.16 | 0.00 | 0.24 | −0.00 | 94.0 |

| 0.4 | 7.77 | −0.17 | 0.00 | 7.05 | −0.16 | 0.00 | 0.16 | −0.00 | 95.5 | |

| 0.6 | 7.77 | −0.17 | 0.00 | 6.93 | −0.16 | 0.00 | 0.16 | −0.00 | 94.5 | |

| 0.8 | 7.77 | −0.17 | 0.00 | 6.78 | −0.16 | 0.00 | 0.15 | −0.00 | 95.5 | |

| Valley | 0.2 | 12.55 | 0.78 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 85.0 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 95.0 |

| 0.4 | 5.93 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.14 | −0.07 | 67.0 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 95.5 | |

| 0.6 | 5.34 | −0.19 | 0.00 | 2.46 | −0.19 | 1.00 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 94.5 | |

| 0.8 | 18.38 | −0.31 | 0.00 | 7.72 | −0.23 | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 94.0 | |

| Hump | 0.2 | 48.56 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 1.30 | −0.12 | 0.48 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 90.0 |

| 0.4 | 73.14 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 98.20 | −0.29 | 0.00 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 97.0 | |

| 0.6 | 160.23 | −0.30 | 0.00 | 131.79 | −0.28 | 0.00 | 0.16 | −0.04 | 95.0 | |

| 0.8 | 14.60 | −0.25 | 0.04 | 4.71 | −0.09 | 21.0 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 96.5 | |

| Decay | 0.2 | 38.15 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 4.43 | −0.07 | 22.0 | 0.43 | −0.01 | 92.0 |

| 0.4 | 55.25 | −0.05 | 0.13 | 5.21 | −0.07 | 0.14 | 0.30 | −0.00 | 94.0 | |

| 0.6 | 122.98 | −0.25 | 0.00 | 5.42 | −0.07 | 0.14 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 95.0 | |

| 0.8 | 17.44 | −0.22 | 0.03 | 6.08 | −0.07 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 96.5 | |

To numerically summarize the performance of three approaches, we calculated the relative bias (i.e., average estimation bias/true value of the mediation effect), mean squared error (MSE), and the coverage probability of the 95% credible interval for αl(t)βl(t) at four different time points t = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 and 0.8. Note that when the mediation effect is not constant, the values of the mediation effect at the four time points are different. For example, the true values of the mediation effect are 1.0, 2.1, 2.7, and 2.8 at t = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 and 0.8, respectively, under the hump-shaped mediation process of subgroup 1. Table 2 shows the results when the simulated data consist of two latent classes. The two comparators, i.e., SMM and DMM, performed poorly with large biases, MSEs, and low coverage rates, because both methods ignored the subgroup difference and only one pooled mediation effect/function was estimated. The SMM performed worse than the DMM because it further assumes that the mediation effect is time invariant. In contrast, the proposed LC-DMM performed well in all the scenarios. The method successfully identified the two latent classes and yielded estimates with small biases and coverage probabilities close to the nominal value. Similar results were observed when the data were simulated with three latent classes, as shown in Table 3.

We investigated the robustness of the proposed method to model misspecification through simulation studies. The proposed method contains two sets of models: the latent class model that describes the relationship between the covariates and the latent class membership, and the mediation model that describes the dynamic mediation process given the latent class membership. In Tables 1-3, we show that the mediation model is robust to the shape of mediation process, partially because the mediation model adopts a nonparametric approach (i.e., the penalized spline). Comparatively, the latent class model is more susceptible to model misspecification. To investigate the impact of the model misspecification, we considered the situations where some baseline covariates are misspecified in the latent class model. Specifically, we generated the latent class membership based the model (5) with three baseline covariates Z1, Z2 and Z3, where Z1 ~Bernoulli(0.3), Z2, Z3 ~ N(0, 2), with regression coefficients ω01 = 0, ω1 = ω2 = ω3 = 2. When fitting the model, we replaced Z1, (Z3, Z2) or (Z1, Z2, Z3) with random variables generated from the same distributions but not associated with the latent class membership. In other words, one, two or three of the covariates in the model were mis-specified. We calculated the accuracy of identifying latent class membership (percentage of correctly assigned membership among the study sample), and the summary statistics for mediation effect at different time points. The results were shown in Table 4. We observed that the accuracy of identifying latent class membership decreased as more covariates were mis-specified in the model.

Table 4:

The identification accuracy (IA) of latent class membership, mean square error (MSE), and relative bias (RB) for the estimates of the mediation effects at time points t = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 and 0.8 using the proposed latent class dynamic mediation model (LC-DMM) with 2 latent classes, when one, two or three of the baseline covariates are misspecified. The truth is there are 2 subgroups.

| Subgroup 1 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setting 1* |

Setting 2* |

Setting 3* |

||||||||

| Shape | t | IA (%) | MSE | RB | IA (%) | MSE | RB | IA (%) | MSE | RB |

| Flat | 0.2 | 99.99 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 97.82 | 0.60 | 0.08 | 50.02 | 12.92 | 0.66 |

| 0.4 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.49 | 0.08 | 12.16 | 0.64 | ||||

| 0.6 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 0.08 | 11.91 | 0.64 | ||||

| 0.8 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.47 | 0.07 | 12.12 | 0.64 | ||||

| Valley | 0.2 | 99.91 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 96.79 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 47.49 | 0.14 | 0.22 |

| 0.4 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 1.11 | 0.90 | 0.39 | ||||

| 0.6 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 2.86 | 0.49 | ||||

| 0.8 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.44 | 0.10 | 6.29 | 0.57 | ||||

| Hump | 0.2 | 99.99 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 96.80 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 55.64 | 3.83 | 1.27 |

| 0.4 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 3.22 | 0.13 | 49.44 | 1.09 | ||||

| 0.6 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 4.62 | 0.10 | 72.66 | 0.80 | ||||

| 0.8 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 1.78 | 0.09 | 21.15 | 0.41 | ||||

| Decay | 0.2 | 99.99 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 95.90 | 2.23 | 0.08 | 50.51 | 24.21 | 0.38 |

| 0.4 | 0.28 | 0.04 | 2.66 | 0.06 | 29.85 | 0.35 | ||||

| 0.6 | 0.33 | 0.04 | 2.76 | 0.06 | 35.52 | 0.34 | ||||

| 0.8 | 0.34 | 0.03 | 2.86 | 0.05 | 39.53 | 0.33 | ||||

| Subgroup 2 |

||||||||||

| Setting 1* |

Setting 2* |

Setting 3* |

||||||||

| Shape | t | IA (%) | MSE | RB | IA (%) | MSE | RB | IA (%) | MSE | RB |

| Flat | 0.2 | 99.99 | 0.31 | 0.05 | 97.82 | 1.00 | 0.07 | 50.02 | 13.07 | 0.31 |

| 0.4 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.06 | 12.79 | 0.30 | ||||

| 0.6 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.89 | 0.06 | 12.63 | 0.30 | ||||

| 0.8 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.85 | 0.06 | 12.48 | 0.30 | ||||

| Valley | 0.2 | 99.91 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 96.79 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 47.49 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| 0.4 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.69 | 0.22 | ||||

| 0.6 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.35 | 0.08 | 3.13 | 0.28 | ||||

| 0.8 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.69 | 0.07 | 7.30 | 0.31 | ||||

| Hump | 0.2 | 99.98 | 0.33 | 0.12 | 96.80 | 0.57 | 0.15 | 55.64 | 3.04 | 0.38 |

| 0.4 | 0.69 | 0.04 | 4.52 | 0.06 | 56.18 | 0.34 | ||||

| 0.6 | 0.87 | 0.03 | 6.64 | 0.06 | 81.09 | 0.31 | ||||

| 0.8 | 1.71 | 0.08 | 2.64 | 0.06 | 13.72 | 0.21 | ||||

| Decay | 0.2 | 99.99 | 0.59 | 0.04 | 95.90 | 2.62 | 0.05 | 50.51 | 26.63 | 0.24 |

| 0.4 | 0.62 | 0.03 | 2.97 | 0.05 | 31.45 | 0.22 | ||||

| 0.6 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 3.45 | 0.05 | 33.99 | 0.21 | ||||

| 0.8 | 0.52 | 0.02 | 3.76 | 0.04 | 36.14 | 0.20 | ||||

Setting 1-3: one, two or three covariates were misspecified.

5. Application

We applied the proposed method to the smoking cessation data that were collected as part of a randomized clinical trial designed to examine the effectiveness of an individually tailored palm-top computer-based relapse prevention program for female smokers (Wetter et al., 2011). Our research question of interest is to estimate how the expectancy of a positive smoking outcome (i.e., M) mediates the effect of a negative mood (i.e., X) on smoking urge (i.e., Y), and to entangle the heterogeneity of mediation effects in the study population by identification of latent subgroups. The baseline covariates that were used to identify the latent subgroups are age, BMI, education (higher than college or not) and race (white or not). All the exposure, mediator and outcome variables were assessed using rating scales. In particular, a 1 to 5 scale was used to evaluate participants’ smoking urge (1=no urge, 5=severe urge). Specifically, participants responded to the question, “How strong is your urge to smoke?” on a five-point scale that ranged from 1 (no urge) to 5 (severe urge). At the same time, their emotional state were assessed by responding to the statement “Right now, my mood is negative (for example: irritable, sad, anxious, tense, stressed, angry, frustrated, etc)”, (1- Definitely NO, 2 - Mostly NO, 3 - Mostly YES, 4 - Definitely YES). Positive smoking outcome expectancies was rated by responding to the question, “Would smoking right now improve your mood, be pleasurable, or help you cope with this situation?” Possible responses were 1 (definitely NO), 2 (mostly no), 3 (mostly yes), 4 (definitely YES). Because smoking urge, negative mood and the expectancy of a positive smoking outcome all varied from morning to night, it is reasonable to conjecture that the mediated effect of the expectancy of a positive smoking outcome may be a dynamic mediated effect that varies across time.

We applied the proposed model, equation (1)-(6), to identify the latent classes and estimate the mediation effects. Specifically, to avoid overfitting and let the data to speak for themselves, we used quadratic penalized splines with 9 equally spaced knots to model the time-varying coefficients, including αl(t), βl(t), τl(t), γl(t) and δl(t). In addition, we assigned vague priors with large variance to model the parameters, which represented the case that we have little prior information on model parameters.

To determine the number of latent classes, beginning from one class, we increased the number of classes until the DIC increased. The DICs for the model with one, two, three and four latent classes were 21351.4, 19548.60, 20667.35, 379092.5, respectively. Thus, we used the two-subgroup model for our analysis.

Figure 2 depicts the estimated subgroup-specific mediation effects , l = 1, 2. The two subgroups demonstrate rather different mediation effects. One subgroup, which might be called the “non-mediated subgroup”, shows little mediation effect throughout the day. The estimated curve is almost flat and close to 0. In contrast, the other subgroup, which might be called the “mediated subgroup”, shows a concave mediation effect curve. The mediation effect is relatively weak in the morning, around 8:00 AM until noon, and then starts to strengthen in the afternoon. We also calculated the proportion of the total effect of negative mood on smoking urge that was explained by the mediation effect for the two subgroups. Notably, as both the mediation effects and total effects were estimated as functions of time, the proportion of mediation effects out of total effects estimated in the proposed method was also a function of time, rather than a constant. The results were shown in Figure 3. In the “non-mediated subgroup”, the proportional of mediation effects out of total effects was almost zero all the time. For the “mediated subgroup”, the proportional of mediation effects out of total effects was between 15% to 25%. Although the magnitude of the mediation effect was relatively weak in late morning and noon, the proportional of mediation effects out of total effects was increasing during this time interval. We compared the characteristics of the two subgroups. The subgroup membership for each subject is determined on the basis of the subgroup that has a higher posterior probability for that subject. For example, if a subject has a higher posterior probability of being in the mediated subgroup than of being in the non-mediated subgroup, he/she is classified into the mediated subgroup, and vice versa. As shown in Table 5, compared to the non-mediated subgroup, the mediated subgroup tends to be younger and less educated. This result suggests that if investigators want to design an intervention program to control smoking urges by modifying the smoker’s positive smoking outcome expectancies, such a program should perhaps target younger and less educated smokers. As older and well educated smokers tend to be in the non-mediated subgroup, the intervention program that aims to modify the smoker’s positive smoking outcome expectancies may not be effective in controlling smoking urges among smokers in that subgroup.

Figure 2:

The estimated mediation effect of positive smoking outcome expectancies on the relationship between negative affect and smoking urge for two subgroups. The shade shows the 95% credible interval.

Figure 3:

The estimated proportion of mediation effects of the positive smoking outcome expectancies on the relationship between negative affect and smoking urge out of total effects of the negative affect on smoking urge for two subgroups. The blue line indicates the “non-mediated subgroup” and the black line indicates the “mediated subgroup”.

Table 5:

Comparison of characteristics between two smoker subgroups identified by the latent class dynamic mediation model. Numbers in parentheses are standard errors.

| Variable | Mediated subgroup (n = 270) |

Non-mediated subgroup (n = 22) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.3 (10.7) | 49.0 (9.5) | 0.005* |

| BMI | 26.5 (6.2) | 25.0 (5.8) | 0.30* |

| Education (≥ college) | 20% | 50% | 0.007† |

| Race (white or not) | 83.3% | 81.8% | 0.77† |

t-test;

Chi-squared test.

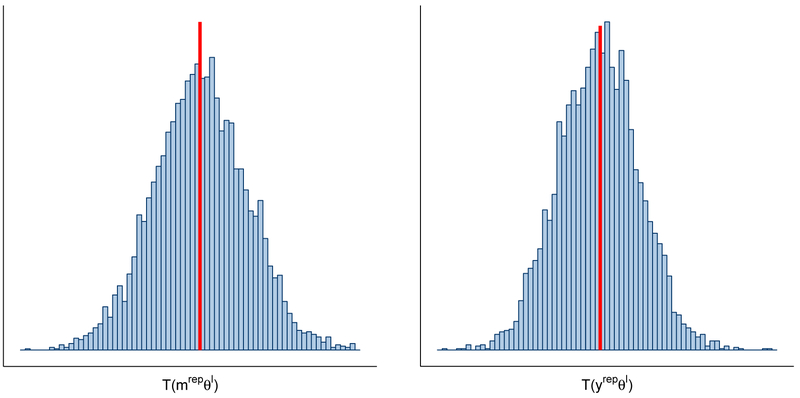

Lastly, we assessed the goodness-of-fit of our model using posterior-predictive checking based on the χ2 discrepancy measures (Gelman, Meng, and Stern, 1996) as follows:

where θ is the set of model parameters. As shown in Figure 4, the posterior-predictive probabilities are 0.498 and 0.509 for T(y, θ) and T(m, θ), respectively, suggesting that the proposed model provides a reasonable fit to the smoking cessation data.

Figure 4:

Distribution of posterior predictive check statistics T(y, θ) and T(m, θ). Red line indicates the statistics calculated based on the observed data.

6. Discussion

Mediation analysis is a valuable tool to understand the mechanism behind complex health behaviors by partitioning the overall effect into direct effects and mediation effects, thus facilitating investigators to design effective intervention programs. In this paper, we proposed a latent class dynamic mediation analysis model to disentangle the heterogeneity of mediation effect in the population by identifying latent classes, with class-specific mediation effects. Specifically, using a proportion odds model, our approach accommodates the possible existence of different subgroups within the study population. Moreover, given the subgroups, we used time-varying parameters to capture the dynamic mediation process over time and allow identification of hinge points where effects change. We provided conditions such that the estimated mediation effect represents a causal effect. Our simulation study showed that the proposed method has good performance to estimate the mediation effect. We applied the proposed methods to a smoking cessation data and studied the mediation effect of positive smoking outcome expectancies on negative mood on smoking urge. We successfully identified two unique latent classes. In one of them, the mediation effect is a concave shaped curve during smokers’ wake time, while in the other one, the mediation effect is almost null throughout the day. Our findings provide insights for investigators to design effective intervention program that is specifically tailored for a given subject. As our method acknowledges the heterogeneity of the population and allows us to capture each subgroup’s personalized mediation process, it provides a useful method to achieve precision medicine.

The proposed approach has a few limitations that deserve further investigation. First, within each latent class, the proposed dynamic mediation model adopts the original Baron and Kenny’s three-variable approach that did not have covariates, as shown in Figure 1. In practice, the proposed method can be easily extended to include covariates in equation (1) & (2). Such extensions of Baron and Kenny’s model have been extensively discussed in literature (VanderWeele & Vansteelandt 2009; Valeri & VanderWeele 2013). Second, the proposed method does not fully accommodate settings in which the exposure and the mediator or the exposure and covariates may interact to affect the outcome. If such interactions are present, interaction terms might need to be included in equation (1) & (2) to have a correctly specified model. In addition, the proposed model focuses on the contemporaneous relationships among variables and assumes that the exposure and mediator are not affected by variables measured at earlier time points. Such assumptions are discussed and named as “no time-varying confounding with respect to both the exposure and mediator variables” in Bind et al. 2016. Strategies to account for time-varying confounding in longitudinal data have been previously discussed (Robins et al. 2000; Heagerty & Comstock 2013), and in mediation analysis (VanderWeele & Tchetgen Tchetgen 2014). In the proposed model, a possible extension is to include variables at earlier time points to equation (1) & (2). While the extension of statistical model is straightforward, the assumptions of identifying causal mediation effects need to reevaluated carefully. In addition, we focus on the case in which there is only a single mediator. The extension of the proposed model to a model with multiple mediators is straightforward by including multiple mediators as additional covariates in the regression model (2), and for each additional mediator, add a regression model similar to equation (1) by replacing M with that mediator as the response. The overall mediation effect is the sum of the mediation effect associated with each individual mediator.

Supplementary Material

References

- Anatchkova MD, Velicer WF, and Prochaska JO (2006). Replication of subtypes for smoking cessation within the precontemplation stage of change. Addictive Behaviors, 31(7), 1101–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, and Fiore MC (2004). Addiction motivation reformulated: An effective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review, 111 (1), 33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM and Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51 (6), 1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bind MA, Vanderweele TJ, Coull BA, and Schwartz JD (2015). Causal mediation analysis for longitudinal data with exogenous exposure. Biostatistics, 17 (1), 122–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA (2002). Latent variables in psychology and the social sciences. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 605–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommelé J, Kleinjan M, Schoenmakers TM, Burk WJ, Van Den Eijnden R, and Van De Mheen D (2015). Identifying subgroups among hardcore smokers: a latent profile approach. PloS one, 10 (7), e0133570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Wetter DW, and Baker TB (1996). Affect, expectancies, urges, and smoking: Do they conform to models of drug motivation and relapse? Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 4 (1), 29. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RL (1997). Assessing specific mediational effects in complex theoretical models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 4(2), 142–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA and Maxwell SE (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112 (4), 558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels MJ, Roy JA, Kim C, Hogan JW, and Perri MG (2012). Bayesian inference for the causal effect of mediation. Biometrics, 68(4), 1028–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didelez V, Dawid P, and Geneletti S (2012). Direct and indirect effects of sequential treatments. arXiv preprint arXiv:1206.6840. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MR, Gallo JJ, Ten Have TR, Bogner HR, and Katz IR (2005). Using a Bayesian latent growth curve model to identify trajectories of positive affect and negative events following myocardial infarction. Biostatistics, 6(1), 119–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers PH and Marx BD (1996). Flexible smoothing with b-splines and penalties. Statistical Science, 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, and Linder GF (1999). Family violence and the perpetration of adolescent dating violence: Examining social learning and social control processes. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 331–342. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett ES, and Zeger SL (2000). Latent class model diagnosis. Biometrics, 56(4), 1055–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Meng XL, and Stern H (1996). Posterior predictive assessment of model fitness via realized discrepancies. Statistica sinica, 733–760. [Google Scholar]

- Geneletti S (2007). Identifying direct and indirect effects in a non?counterfactual framework. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology), 69(2), 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Gollob H and Reichardt C (1991). Interpreting and estimating indirect effects assuming time lags really matter, 243-259 In: Collins L and Horn J, eds., Best Methods for the Analysis of Change: Recent Advances, Unanswered Questions, Future Directions. American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Green P and Silverman B (1994). Nonparametric Regression and Generalized Linear Models: A Roughness Penalty Approach. Chapman & Hall, London. [Google Scholar]

- Hafeman DM, and VanderWeele TJ (2011). Alternative assumptions for the identification of direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology, 22(6), 753–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, and Preacher KJ (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67(3), 451–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heagerty PJ, and Comstock BA (2013). Exploration of lagged associations using longitudinal data. Biometrics, 69(1), 197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, and Kenny DA (1999). Sample size, reliability, and tests of statistical mediation In Hoyle RH (Ed.), Statistical strategies for small sample research (pp. 195–222). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, and Yuan Y (2017). Bayesian dynamic mediation analysis. Psychological methods, 22(4), 667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husten CG, McCarty MC, Giovino GA, Chrismon JH, and Zhu BP (1998). Intermittent smokers: a descriptive analysis of persons who have never smoked daily. American Journal of Public Health, 88(1), 86–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, Keele L, and Yamamoto T (2010). Identification, inference and sensitivity analysis for causal mediation effects. Statistical science, 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MJ (2004). Why people smoke. BMJ, 328(7434), 277–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jullion A, and Lambert P (2007). Robust specification of the roughness penalty prior distribution in spatially adaptive Bayesian P-splines models. Computational statistics & data analysis, 51(5), 2542–2558. [Google Scholar]

- Joffe MM, Small D, and Hsu CY (2007). Defining and estimating intervention effects for groups that will develop an auxiliary outcome. Statistical Science, 74–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner TR and Sayette MA (2007). Effects of smoking abstinence and alcohol consumption on smoking-related outcome expectancies in heavy smokers and tobacco chippers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 9 (3), 365–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau RS, and Cheung GW (2010). Estimating and comparing specific mediation effects in complex latent variable models. Organizational Research Methods, 1094428110391673. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, and Song X (2012). Finite mixture varying coefficient models for analyzing longitudinal heterogenous data. Statistics in medicine, 31 (6), 544–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP (2000). Contrasts in multiple mediator models In: Rose JS, Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ (eds.). Multivariate Applications in Substance Use Research: New methods for New Questions, 141–160. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Homan JM, West SG, and Sheets V (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7 (1), 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, and Dwyer JH (1995). A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 30(1), 41–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman GJ, Velicer WF, Fava JL, and Prochaska JO (2000). Cluster subtypes within stage of change in a representative sample of smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 25(2), 183–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl J (2001). Direct and indirect effects. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, 411-420 Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen ML, Sinisi SE, and van der Laan MJ (2006). Estimation of direct causal effects. Epidemiology, 17(3), 276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poland BD, Cohen JE, Ashley MJ, Adlaf E, Ferrence R, Pederson LL, … and Raphael D (2000). Heterogeneity among smokers and non-smokers in attitudes and behaviour regarding smoking and smoking restrictions. Tobacco Control, 9(4), 364–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, and Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzel LR, Cromley EK, Li Y, et al. (2011) The effect of tobacco outlet density and proximity on smoking relapse during a specific quit attempt. American Journal of Public Health, 101, 315–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts GO, and Rosenthal JS (2009). Examples of adaptive MCMC. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 18(2), 349–367. [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM (2003). Semantics of causal DAG models and the identification of direct and indirect effects. Highly structured stochastic systems, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM and Greenland S (1992). Identifiability and exchangeability for direct andindirect effects. Epidemiology, 3 (2), 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM, Hernan MA and Brumback B (2000). Marginal structural models and causal inference in Epidemiology. Epidemiology, 11: 550–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB (1974). Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 66 (5), 688–701. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB (1990). Comment: Neyman (1923) and causal inference in experiments and observational studies. Statistical Science, 5 (4), 472–480. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB (2004). Direct and indirect causal effects via potential outcomes. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 31(2), 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppert D (2002). Selecting the number of knots for penalized splines. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 11 (4). [Google Scholar]

- Ruppert D, Wand MP and Carroll RJ (2003). Semiparametric Regression. Cambridge University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JE, Reid RJ, Peterson NA, Lowe JB, and Hughey J (2005) Tobacco outlet density and demographics at the tract level of analysis in Iowa: implications for environmentally based prevention initiatives. Prevention Science, 6 (4), 319–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiyko MP, Lanza ST, Tan X, Li R, and Shiffman S (2012). Using the time-varying effect model (TVEM) to examine dynamic associations between negative affect and self-confidence on smoking urges: Differences between successful quitters and relapsers. Prevention Science, 13 (3), 288–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF, and Kendler KS (1999). The genetic epidemiology of smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 1(Suppl2), S51–S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ten Have TR, Elliott MR, Joffe M, Zanutto E, and Datto C (2004). Causal models for randomized physician encouragement trials in treating primary care depression. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 99(465), 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Valeri L, and VanderWeele TJ (2013). Mediation analysis allowing for exposure?mediator interactions and causal interpretation: Theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychological methods, 18(2), 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele TJ, Tchetgen EJT, Cornelis M, and Kraft P (2014). Methodological challenges in Mendelian randomization. Epidemiology,25(3), 427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele T and Vansteelandt S (2009). Conceptual issues concerning mediation, interventions and composition. Statistics and its Interface, 2, 457–468. [Google Scholar]

- VanderWeele TJ, and Vansteelandt S (2010). Odds ratios for mediation analysis for a dichotomous outcome. American journal of epidemiology, 172(12), 1339–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, Redding CA, Sun X, and Prochaska JO (2007). Demographic variables, smoking variables, and outcome across five studies. Health Psychology, 26(3), 278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SG, and Aiken LS (1997). Toward understanding individual effects in multicomponent prevention programs: Design and analysis strategies In Bryant KJ, Windle M, and West SG (Eds.), The science of prevention: Methodological advances from alcohol and substance abuse research (pp. 167–209). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Wetter DW, McClure JB, Cofta-Woerpel L, Costello TJ, Reitzel LR, Businelle MS,and Cinciripini PM (2011). A randomized clinical trial of a palmtop computer-delivered treatment for smoking relapse prevention among women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25 (2), 365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K and Marlatt GA(2004). Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: that was Zen, this is Tao. American Psychologist, 59 (4), 224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y and MacKinnon DP (2009). Bayesian mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 14 (4), 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.