Abstract

Objective –

Albuminuria is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease in diabetes. We determined whether albuminuria associates with alterations in the proteome of HDL of subjects with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), and whether those alterations associated with coronary artery calcification (CAC).

Approach and Results –

In a cross-sectional study of 191 subjects enrolled in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study (DCCT/EDIC), we used isotope dilution tandem-mass spectrometry to quantify 46 proteins in HDL. Stringent statistical analysis demonstrated that eight proteins associated with albuminuria. Two of those proteins, α−1-microglobulin/bikunin precursor (AMBP) and prostaglandin-H2 D-isomerase (PTGDS), strongly and positively associated with the albumin excretion rate (P<10−6). Furthermore, paraoxonase 1 (PON1) and PON3 levels in HDL strongly and negatively associated with the presence of coronary artery calcium, with odds ratios per 1-SD difference of 0.63 (0.43–0.92, 95% CI, P=0.018) for PON1 and 0.59 (0.40–0.87, 95% CI, P=0.0079) for PON3. Only one protein, PON1, associated with both albumin excretion rate and CAC.

Conclusions –

Our observations indicate that the HDL proteome is remodeled in T1DM subjects with albuminuria. Moreover, low concentrations of the anti-atherosclerotic protein PON1 in HDL associated with both albuminuria and CAC, raising the possibility that alterations in HDL’s protein cargo mediate in part the known association of albuminuria with cardiovascular risk in T1DM.

Keywords: HDL proteomics, HDL-C, LDL-C, triglycerides, kidney disease, selected reaction monitoring

Graphical Abstract

Albuminuria is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in people with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and in the general population1–4. Albuminuria also increases the risk of progressing to end-stage renal disease (ESRD)5, 6. Albuminuria may contribute to CVD risk in T2DM subjects by promoting an atherogenic lipid profile characterized by elevated triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), and a shift in LDL to small, dense particles7. However, HDL-C levels are not consistently low in T1DM subjects despite their increase in CVD risk8–10.

Clinical and epidemiological studies show a robust, inverse association of HDL-C levels with CVD risk11, 12. However, several lines of evidence suggest that the association between HDL-C levels and CVD status is not a causal relationship and that elevating HDL-C is not necessarily therapeutic13, 14. For example, a genetic mutation in SR-BI (SCARB1), a protein critically involved in HDL metabolism in the liver, greatly increases both HDL-C levels and atherosclerosis15, 16. Collectively these observations indicate that HDL-C levels do not necessarily reflect HDL’s cardioprotective effects.

HDL metrics other than HDL-C are likely to mediate HDL’s cardioprotective effects. HDL carries a wide array of proteins linked to lipoprotein metabolism, inflammation, protease inhibition, and complement regulation, suggesting that this cargo contributes to HDL’s anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic properties17. We found that the HDL proteome is dramatically remodeled in ESRD patients18. It is unclear whether albuminuria in T1DM affects HDL’s protein cargo or whether alterations in HDL’s proteins associate with CVD in T1DM.

In the current study, we used targeted mass spectrometric proteomics to test the hypotheses that alternations in the HDL proteome associate with albuminuria in T1DM subjects. Because albuminuria is a risk factor for CVD, we also determined whether changes in the abundance of proteins in the HDL proteome associate with coronary artery calcification, which strongly predicts incident CVD risk19. Our observations support the proposal that certain HDL proteins may be markers–and perhaps mediators–of albuminuria and the increased cardiovascular risk associated with T1DM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Subjects and experimental design.

The Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) study20 was an observational cohort study of T1DM subjects that followed the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT). All subjects in our study were enrolled in an ancillary EDIC study of lipoproteins21 that involved subjects from all 28 clinical sites in the United States and Canada21. For this study, extra plasma was obtained every other year during EDIC years 3–12 (1997–2006). After an overnight fast, blood was collected into ice-cold tubes containing EDTA (6 mM final concentration). Plasma was prepared immediately by centrifugation (2500 g for 15 min) and frozen at −80°C until analysis22. All studies were approved by the Human Studies Committee at the University of Washington, which coordinated the lipoprotein ancillary study, and by the EDIC clinical centers.

We designed a cross-sectional study based on urinary albumin excretion, with oversampling of participants with microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria. Urinary albumin excretion had been quantified every other year as albumin excretion rate (AER). Fasting blood and AER had been collected in the alternate years. We first selected all the stored plasma samples from annual visits at which the ancillary EDIC subjects had demonstrated macroalbuminuria (AER ≥300 mg/dL) at that visit as well as one year earlier and one year later. We then randomly sampled similar numbers of participants who demonstrated microalbuminuria (AER 30–299 mg/dL) or normoalbuminuria (AER <30 mg/dL)23 during the annual visit and one year earlier and later. Subjects were not selected on the basis of gender, HbA1c, or other clinical criteria. When multiple time points were available for a given participant, we used the time point closest to EDIC year 7 or 8 (calendar year 2000–2002), when EDIC measured coronary artery calcification (CAC)24. For each selected subject, we used the clinical characteristics obtained at the same visit as the plasma sample. The mean duration of diabetes at the time of sampling was >20 years in each group.

HDL isolation.

HDL (density 1.063–1.210 g/mL) was isolated by sequential ultracentrifugation from rapidly thawed plasma25, using buffers supplemented with 100 μM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), 100 μM butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The protein concentration of HDL was determined using the Lowry assay (BioRad), with albumin as the standard. All samples were deidentified and analyzed in a blinded manner in HDL isolation, HDL proteomics, and statistical analysis.

Targeted quantification of HDL proteins by selected reaction monitoring (SRM) with 15N-labeled APOA1 as the internal standard.

Human [15N]APOA1 (>99% purity after isolation) was produced by a bacterial expression system26. Following the addition of freshly prepared methionine (10 mM final concentration), HDL proteins (10 μg total proteins) and [15N]APOA1 (0.5 μg, as the internal standard) were reduced with dithiothreitol and alkylated with iodoacetamide. Tryptic digests of HDL were analyzed with a nano-LC-MS/MS Thermo TSQ Vantage coupled to a Waters nanoACQUITY UltraPerformance liquid chromatography system18, 25. Resolution for Q1 and Q3 were 0.7 Da (full width at half maximum), and analyses were performed using a scheduled transition list generated by Skyline27, an open source program for quantitative data processing and proteomic analysis. At least two peptides per protein and three or four SRM transitions of each peptide were used for the Skyline analysis18, 25. The results were expressed as the ratio of the peak areas of each peptide and the [15N]APOA1 peptide [15N]THLAPYSDELR. To calculate the relative levels of each peptide, we set the average ratio of the peptide to the internal standard peptide in normoalbuminuric subjects to an arbitrary unit of one.

Statistical analysis.

Differences in relative protein expression by albuminuria status determined by SRM analysis were evaluated by ANOVA of the group means. We also performed multiple linear regression analyses for percent changes of protein levels in HDL per doubling in AER with or without adjustment for clinical characteristics including age, sex, DCCT treatment group, use of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi), duration of diabetes, use of lipid-lowering medications, smoking, body mass index (BMI), and mean percentage of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c%). To account for multiple comparison testing of HDL proteins, we used the Benjamini-Hochberg method with a 10% false discovery rate, i.e. based on the corrected or adjusted p-values (q-values), only proteins with a q-value less than 0.10 were considered significant. We tested associations of HDL proteins with the presence of CAC by using logistic regression analysis. The logistic models were adjusted for potential confounders as described above and also for log(AER). Odds ratios (ORs) are reported per analyte SD. Correlation analysis with continuous variables used Pearson’s coefficient. All statistical analyses were performed in R, a free software environment for statistical computing and graphics.

RESULTS

The clinical characteristics of the 191 subjects we studied are listed in Table 1. The three groups (normoalbuminuria, microalbuminuria, macroalbuminuria) had similar mean ages, percentages of smokers, BMIs, and HDL-C levels. LDL-C levels were slightly lower and the duration of diabetes was slightly longer in the normoalbuminuria group. In contrast, the groups differed significantly in gender distribution. Also, median levels of triglycerides differed significantly among the three groups (higher in the macroalbuminuria group), as did estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR) (lower in macroalbuminuria subjects) and HbA1c levels (lower in the normoalbuminuria subjects). There were no differences in HbA1c, albuminuria, or coronary artery calcium between the EDIC subjects, whose glucose levels had been tightly controlled, and the DCCT subjects, whose levels had been controlled less tightly.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of subjects with T1DM by albumin excretion rate (AER) status.

| Covariate | Normal AER (< 30 mg/day) |

Microalbuminuria (30 – < 300 mg/day) |

Macroalbuminuria (≥ 300 mg/day) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 67 | 64 | 60 | |

| Age (years) | 42.0 (37.0–48.0) | 44.0 (35.0–48.2) | 43.5 (36.2–49.0) | 0.45 |

| Gender (Female) | 39 (58) | 16 (25) | 10 (17) | <0.0001 |

| Caucasian | 67 (100) | 64 (100) | 60 (100) | |

| DCCT treatment | ||||

| Conventional glucose control | 39 (58) | 41 (64) | 48 (80) | 0.01 |

| Intensive glucose control | 28 (42) | 23 (36) | 12 (20) | 0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.6 (24.6–30.7) | 27.0 (24.8–29.8) | 28.3 (25.2–31.2) | 0.34 |

| Smoker | 17 (25) | 12 (19) | 21 (35) | 0.24 |

| Blood pressure med(s) | 41 (61) | 44 (69) | 48 (80) | |

| Lipid-lowering med(s) | 46 (69) | 49 (77) | 53 (88) | 0.008 |

| Statin | 18 (27) | 3 (5) | 18 (30) | 0.0006 |

| RAASi | ||||

| ACEi | 42 (63) | 49 (77) | 53 (88) | 0.001 |

| ARB | 10 (15) | 0 (0) | 9 (15) | |

| Duration of DM (years) | 26.1 (22.1–30.0) | 20.0 (17.3–24.3) | 22.0 (18.4–24.3) | 0.04 |

| eGFR (CKD-EPI) (mL/min/1.73m2) |

106.0 (93.8–113.4) | 106.5 (95.3–114.5) | 84.1 (57.1–106.5) | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c (%) (mmol/mol) |

7.7 (7.0–8.8) 61 (54–73) |

8.4 (7.7–9.4) 68 (61–79) |

8.6 (7.8–9.6) 70 (62–82) |

0.006 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 117.0 (111.5–124.8) | 124.0 (114.5–132.5) | 132.0 (125.0–144.0) | 0.0001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 73.0 (69.0–78.5) | 78.0 (72.0–82.5) | 80.0 (71.5–86.5) | 0.02 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 50.0 (43.0–62.0) | 49.0 (41.8–59.0) | 50.0 (42.0–59.5) | 0.55 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 103.0 (86.0–118.0) | 110.0 (86.2–134.2) | 110.0 (84.0–135.5) | 0.03 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 173.0 (157.0–188.0) | 183.5 (153.8–203.0) | 187.0 (154.0–221.5) | 0.004 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 69.0 (53.0–117.0) | 85.0 (54.8–111.0) | 117.0 (70.0–180.5) | 0.002 |

| AER | 12.0 (9.3–16.4) | 69.5 (50.7–97.0) | 758.8 (559.4–1497.2) | <0.0001 |

Entries are median (interquartile range) for continuous covariates and N (%) for categorical covariates. RAASi, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor; ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB angiotensin II receptor blocker. P-values were obtained by ANOVA analysis of the differences among group means.

SRM analysis revealed marked differences in the abundance of multiple HDL proteins in T1DM subjects with albuminuria.

To test whether albuminuria and CVD associate with abnormalities in HDL’s protein cargo in T1DM, we used tandem MS analysis with targeted SRM18 and isotope dilution to quantify relative levels of 46 proteins in HDL from the three groups of subjects. We selected these proteins because they were reproducibly detected in preliminary shotgun proteomics analysis17, 18 of TIDM subjects with normoalbuminuria, microalbuminuria, and macroalbuminuria (10 in each group, data not shown). All 46 proteins were detected in HDL isolated by ultracentrifugation from each of the 191 subjects in this study. Differences in protein expression were initially evaluated by a test for trend without adjustment for clinical characteristics but with adjustment for multiple comparison (Benjamin-Hochberg adjusted p-value < 0.10). This analysis revealed that 14 proteins were differentially expressed in subjects with micro- or macro-albuminuria, as compared with subjects with normoalbuminuria (Supplemental Table I).

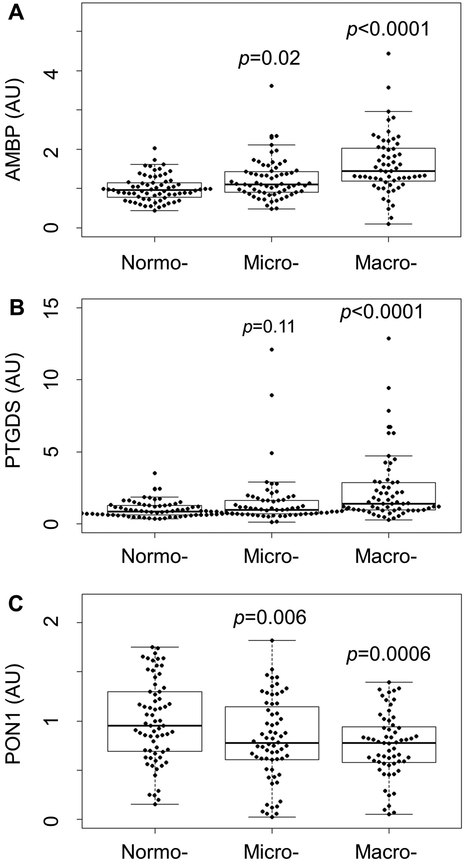

Seven proteins (AMBP, B2M, CST3, LPA, PSAP, PTGDS, and RBP4) were significantly increased in HDL isolated from subjects with micro- and macro-albuminuria, as compared with those with normoalbuminuria. It is noteworthy that five of the seven proteins, AMBP, B2M, CST3, PTGDS, and RBP4, were increased markedly in HDL of ESRD subjects in a previous study18. In contrast, seven proteins (APOA1, APOA2, APOE, PCYOX1, PON1, PON3, and SAA4) were significantly reduced in HDL isolated from subjects with micro- and macro-albuminuria compared with those with normoalbuminuria. Representative examples of proteins that were markedly altered in the HDL of subjects with albuminuria are shown in Fig. 1. These observations demonstrated that albuminuria in T1DM subjects is associated with abnormalities in HDL protein composition.

Figure 1. SRM analysis of HDL proteins in normo-, micro- and macroalbuminuria subjects.

Box plots of AMBP (A), PTGDS (B), and PON1 (C) in HDL isolated from normo-, micro- and macroalbuminuria subjects. Peptides were quantified as the integrated peak area relative to that of [15N]APOA1. The box plots show the distribution of the data (median, interquartile ranges), while the dots represent individual data points. P-values are relative to the normoalbuminuria group. AU, arbitrary units.

HDL proteins associate with continuous albumin excretion rate (AER).

We used the absolute values of albumin excretion rate (i.e. the continuous AER) instead of albuminuria status (i.e. normo-, micro-, and macroalbuminuria) to investigate further the relationship between the levels of HDL proteins and albuminuria. We first used a linear regression model to test the association between HDL proteins and continuous AER without adjustment for clinical characteristics. When we adjusted for multiple comparison with the Benjamini-Hochberg method, 13 proteins remained significantly associated with continuous AER. Next, we tested the association between HDL proteins and continuous AER with a multivariable linear regression model with adjustment for clinical characteristics (Supplemental Table II). After adjusting for differences in gender distribution and other potential confounders and controlling for multiple comparisons, 8 proteins were associated with continuous AER (Table 2). Two of those proteins, AMBP and PTGDS (Fig. 2), exhibited large percentage differences per doubling of the continuous AER (≥10%) that were highly significant (P<0.0002). Taken together, these observations indicate that the relative abundance of certain proteins in HDL of subjects with albuminuria differed markedly from that of subjects with normoalbuminuria.

Table 2.

Adjusted associations of HDL proteins with log(AER).

| Protein | % Difference per doubling in AER (95% CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|

| AMBP | 10 (5, 15) | 9.11E–05 |

| PTGDS | 30 (14, 45) | 0.00015 |

| APOA2 | −2 (−3, −1) | 0.0023 |

| APOE | −4 (−7, −1) | 0.0092 |

| CFD | −3 (−6, −1) | 0.0099 |

| PSAP | 4 (1, 7) | 0.014 |

| SAA4 | −2 (−4, 0) | 0.016 |

| PON1 | −3 (−6, −1) | 0.017 |

P-values are from a linear regression model that adjusts for age, sex, DCCT treatment group, use of RAASi, duration of DM, use of lipid-lowering medications, smoking, BMI, and HbA1c. HDL proteins that are significant when controlling the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (q-values) at 10% are shown (Supplemental Table II).

Figure 2. Volcano plot of adjusted associations of continuous log(AER) with each HDL protein (percent difference per doubling in AER).

For each protein, p-values are plotted versus the percent change in HDL protein levels per doubling in AER from a model that adjusts for age, sex, DCCT treatment group, use of RAASi, duration of diabetes, use of lipid-lowering medications, smoking, BMI, and HbA1c. Proteins that were increased with the doubling in AER are displayed to the right of the value 0 on the x axis (the vertical dashed line), while decreased proteins are to the left. The horizontal dotted line indicates the significance threshold using Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate of 10%.

Certain HDL proteins correlate highly with both eGFR and albuminuria while others correlate only with albuminuria.

We next determined the correlation between HDL proteins, albuminuria and GFR, quantified as log transformed AER and eGFR, respectively (Supplemental Table III). AMBP, PSAP and PTGDS strongly and negatively correlated with eGFR (Table 3; r=−0.47, −0.29 and −0.43, respectively). All three proteins also correlated strongly and positively with log(AER) (Table 3; r=0.46, 0.22 and 0.36, respectively). In contrast, APOE, SAA4 and PON1 exhibited significant negative correlations with log(AER) (r=−0.28, −0.20 and −0.22, respectively) but did not correlate significantly with eGFR (Table 3; r<0.12). These observations suggest that certain HDL proteins (AMBP, PSAP, PTGDS) are markers for both eGFR and albuminuria. In contrast, other proteins (APOE, SAA4, PON1) correlate only with albumin excretion.

Table 3.

Correlations (r) of HDL proteins with log(AER) and eGFR.

| Protein | r log(AER) |

P-value | Protein | r eGFR |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBP | 0.46 | 1.3E–11 | AMBP | −0.47 | 6.0E-12 |

| PTGDS | 0.36 | 2.9E–07 | PTGDS | −0.43 | 8.9E-10 |

| APOE | −0.28 | 0.0001 | APOE | 0.06 | 0.41 |

| PSAP | 0.22 | 0.0024 | PSAP | −0.29 | 6.4E-05 |

| SAA4 | −0.20 | 0.0059 | SAA4 | 0.11 | 0.15 |

| PON1 | −0.22 | 0.0024 | PON1 | 0.01 | 0.88 |

Pearson’s coefficients (r) and p-values are from correlation analysis between the levels of HDL proteins and log(AER) or eGFR. Only HDL proteins that are significant when controlling the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (q-values) at 10% are shown (Supplemental Table II).

PON1 and PON3 in HDL strongly and negatively associate with coronary artery calcification.

Using a logistic regression model, we next determined if levels of HDL proteins associated with coronary artery calcification (CAC). In this model, in addition to age, sex, DCCT treatment group, use of renin- angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, duration of diabetes, use of lipid-lowering medications, smoking, BMI, and HbA1c, we also adjusted for log(AER). This analysis revealed that three HDL proteins, PON1, PON3 and LCAT were negatively associated with CVD, defined as CAC>0 (Supplemental Table IV). For PON1 and PON3, the odds ratios per 1-SD change were 0.63 and 0.59 with a p-value of 0.018 and 0.0079, respectively (Fig. 3). The mean levels of PON1 and PON3 in HDL isolated from subjects with coronary artery calcification were 18% and 24% lower, respectively, than those from subjects without calcification. The significant differences for PON1 and PON3 persisted after controlling for levels of HDL-C, LDL-C, and triglycerides. Moreover, LDL-C, HDL-C and triglycerides did not associate with coronary artery calcification in the fully adjusted model (Fig. 3). In contrast, the difference in LCAT levels was no longer significant after controlling for levels of HDL-C, LDL-C, and triglycerides. Although AMBP and PTGDS were strongly and positively associated with albuminuria, these two proteins were not associated with CAC>0 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. PON1 and PON3 in HDL associate with the presence of CAC in a multiple regression model.

Odds ratios are per analyte SD. Estimates are from a multiple regression model that additionally adjusts for age, sex, DCCT treatment group, use of RAASi, duration of diabetes, use of lipid-lowering medications, smoking, BMI, HbA1c, and continuous log(AER).

To determine whether PON1 enzymatic activity correlates with PON1 mass (assessed by isotope dilution MS/MS), we quantified PON1 activity with two substrates—phenyl acetate (PA) and 4-(chloromethyl)phenyl acetate (CMPA)28—in 238 subjects participating in the Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) study29. We found a positive correlation between PON1 mass and PON1 activity with each assay (PA, r=0.47, P<10−13; CMPA, r=0.31, P<10−6). These observations support the proposal that PON1 mass correlates strongly with PON1 enzymatic activity. In contrast, we found no correlation of PON1 mass or activity with cholesterol efflux capacity (measured with the Rothblatt/Rader method30), suggesting that PON1 mass and/or activity are not major modulators of HDL’s ability to promote cholesterol efflux from macrophages.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we used targeted MS/MS with isotope dilution to quantify 46 proteins in HDL isolated from subjects in the DCCT/EDIC study to determine whether albuminuria associated with alterations in HDL’s protein cargo. The relative levels of eight proteins in HDL associated significantly with continuous albumin excretion rate in a model corrected for multiple comparisons and clinically relevant characteristics (Fig. 4). Two of the proteins, AMBP and PTGDS, were very strongly and positively associated with albuminuria. Because albuminuria is an independent risk factor for CVD in both diabetic and non-diabetic subjects4, 31, we also determined whether changes in HDL protein levels associate with coronary artery calcification (CAC>0), a strong predictor of CVD risk19. We identified two proteins, PON1 and PON3 that strongly and negatively associated with coronary artery calcification (Fig. 4). Only one protein, PON1, associated with both albumin excretion rate and CVD. Taken together, our observations indicate that the HDL proteome is remodeled in albuminuria, that low levels of PON1 and PON3 associate with coronary artery calcification, and that increased CVD risk in T1DM subjects with albuminuria may be mediated in part by decreased PON1 levels in HDL.

Figure 4. Venn diagram of HDL proteins, albuminuria and CVD.

Of the 46 proteins quantified in HDL isolated from T1DM subjects with or without albuminuria, eight proteins were significantly associated with albuminuria with adjustment for clinical characteristics and controlling the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate at 10%. Two of those HDL proteins were negatively associated with logit (CAC>0) with adjustment for clinical characteristics and controlling the HDL-C, LDL-C, and triglycerides levels.

The PON gene family has 3 members, PON1, PON2, and PON3, that share 80% to 90% sequence identity at the amino acid level among mammalian species32. PON1 and PON3 are exclusively carried by circulating HDL33–35, while PON2 is an intracellular protein that localizes in the membrane fraction of cells36. Importantly, PON1 deficient mice and mice deficient in both PON1 and APOE developed atherosclerosis faster than control mice fed with atherogenic diet37, 38. Overexpression of PON1 protected APOE-deficient mice from atherosclerosis39, 40. Because PON1 is strongly anti-atherogenic in mouse models of hypercholesterolemia37, 40, and the levels of PON1 activity in HDL associate negatively with CVD in multiple human studies41–45, these observations suggest that albuminuria might promote pro-atherogenic changes in the HDL of T1DM subjects.

PON1 polymorphisms have been widely investigated for their possible involvement in atherosclerosis46, and epidemiological studies indicate genetic associations between PON1 and the risk of CVD in some populations of subjects47, 48. However, the role of PON1 genetic polymorphisms in the development of CVD remains controversial46, 49. In contrast, levels of PON1 activity associate with CVD in non-diabetic populations in multiple studies41–45. We found that PON1 mass as assessed by MS/MS correlated strongly with PON1 enzymatic activity in a second cohort of T1DM subjects enrolled in the CACTI study. In contrast, PON1 mass and activity did not correlate with macrophage cholesterol efflux capacity. A previous study of T1DM subjects suggested that low levels of PON3, but not PON1, associate with established atherosclerosis21. However, the small number of subjects in that study (28 cases and 28 controls) may have limited the ability to detect a significant association of PON1 with atherosclerosis. Together with our observations, these findings suggest that PON1 and/or PON3 concentration in HDL are more predictive of the risk of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease than are PON1 genotypes. It will be important to quantify PON1 mass and activity as well as other proposed metrics of HDL’s cardioprotective effects in future studies of incident CVD risk in T1DM subjects.

Previous studies demonstrated that APOE associates positively with CVD risk in females with high levels of HDL cholesterol and C-reactive protein but not in males50. In an analysis adjusted for multiple comparisons, we also found that APOE associated with CAC in females but not in males in our cohort. However, that association lost significance after further adjustment for clinical variables, perhaps because there were relatively few females in the groups of albuminuric subjects. It is important to note that albuminuria is more common in males than females with T1DM51.

We used a logistic regression model to determine if any of the proteins whose HDL levels were abnormal in the T1DM subjects with albuminuria associated with prevalent coronary artery disease as assessed by CAC>0. After adjustment for clinical covariates that associate with coronary artery disease, only one protein, PON1, associated strongly and negatively both with CAC>0 and with log(AER). In contrast, PON3 associated strongly and negatively with calcification but not with log(AER). Importantly, these observations were independent of HDL-C, LDL-C, and triglycerides, demonstrating that alterations in HDL’s protein cargo can be dissociated from traditional lipid risk factors for atherosclerosis.

We also found that LCAT associated significantly with coronary artery calcification in the model that adjusted for multiple clinically relevant covariates. However, this association lost significance when we also controlled for LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglyceride levels. These observations suggest that the association of LCAT with coronary artery calcification reflects lipid abnormalities in T1DM subjects.

We previously demonstrated that AMBP and PTGDS are markedly elevated in HDL of ESRD patients on dialysis18. In the current study, AMBP and PTGDS strongly and positively correlated/associated with AER and strongly and negatively correlated/associated with eGFR, which is consistent with the observation that EDIC subjects albuminuria were more likely to exhibit a decrease in eGFR24. Proteolytic processing of AMBP generates alpha-1-microglobulin and bikunin. Alpha-1-microglobulin is a member of the superfamily of lipocalin transport proteins that are implicated in the regulation of inflammatory pathways52. PTGDS is a glutathione-independent prostaglandin D synthase. It catalyzes the conversion of prostaglandin H2 to prostaglandin D2, which regulates smooth muscle contraction and platelet aggregation. Inflammation, altered smooth muscle contraction, and platelet aggregation are implicated in renal injury, raising the possibility that the HDL-associated AMBP and PTGDS contribute to the pathogenesis of renal disease. In future studies, it will be important to determine if elevated levels of AMBP and PTGDS in HDL predict incident albuminuria and/or progressive renal disease in T1DM subjects.

Previous studies have shown that elevated plasma levels of inflammatory makers predict an increased risk of progressive nephropathy in T1DM53. Moreover, levels of the acute phase proteins SAA1 and SAA2 are elevated in HDL from subjects with ESRD18, 54, 55, and elevated levels of SAA1/2 during inflammation impair HDL’s cholesterol efflux capacity in both humans and mice56. However, we found that levels of SAA1 and SAA2 in HDL were similar in subjects with normoalbuminuria and albuminuria and that they failed to associate with coronary artery calcification, suggesting that inflammation-mediated changes in HDL’s protein cargo were not major contributors to altered HDL protein levels, kidney disease, or atherosclerosis in the T1DM subjects in our study.

Strengths of our study include a well-validated targeted proteomic approach to quantifying HDL proteins, the large number of T1DM subjects with varying degrees of albuminuria, stringent statistical analysis, and the similar clinical characteristics of the case and control subjects. A limitation is our study’s cross-sectional design, which could not reveal whether the associations of the HDL proteome with coronary artery calcification and albuminuria were causal. Our study also contained a relatively small number of females with albuminuria, which might have limited our ability to identify gender-dependent markers of CVD. It will therefore be critical to determine whether alterations to the HDL proteome predict the future onset of CVD and kidney disease in T1DM subjects.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that multiple HDL proteins are altered in T1DM subjects with albuminuria. We also found that two HDL proteins associate with prevalent CVD as assessed by the presence of coronary artery calcification and that this association was independent of lipid levels. However, only PON1 associated with both albuminuria and CVD, raising the possibility that increased CVD risk in T1DM subjects with albuminuria is mediated in part by alterations in HDL’s content of PON1. Our observations support the proposal that HDL’s protein cargo can serve as a marker—and perhaps mediator—of kidney disease and risk of atherosclerosis.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

The HDL proteome is remodeled in T1DM subjects with albuminuria.

AMBP, PSAP and PTGDS in HDL all strongly and positively correlated with log(AER); they also strongly and negatively correlated with eGFR.

PON1 and PON3 levels in HDL strongly and negatively associate with atherosclerosis in T1DM but only PON1 associate with both atherosclerosis and renal function.

Alterations in HDL’s protein cargo might mediate in part the known association of albuminuria with cardiovascular risk in T1DM.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

None of the sponsors had any role in study design, data analysis, or reporting of the results. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DP3DK108209, P30DK017047, P01HL092969, R00HL091055, R01HL108897, R01HL112625, and P01HL128203), a Beginning Grant-in-Aid from the American Heart Association (13BGIA17290026), and the University of Washington’s Proteomics Resource (UWPR95794). Mass spectrometry experiments were performed by the Mass Spectrometry Resource, Department of Medicine, University of Washington and the Quantitative and Functional Proteomics Core of the Diabetes Research Center.

Abbreviations:

- AER

albumin excretion rate

- AMBP

α−1-microglobulin/bikunin precursor

- APOA1

apolipoprotein A-I

- CAC

coronary artery calcium

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DCCT

Diabetes Control and Complications Trial

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- EDIC

Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HDL-C

HDL cholesterol

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometric analysis

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- PON1

serum paraoxonase/arylesterase 1

- PON3

serum paraoxonase/arylesterase 3

- PONs

paraoxonases

- PTGDS

prostaglandin-H2 D-isomerase

- RAASi

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors

- SRM

selective reaction monitoring

- T1DM

type 1 diabetes mellitus

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Himmelfarb has served as a consultant to Gilead and Medikine. Dr. Bornfeldt has received research support from Novo Nordisk A/S on a different project. Dr. Heinecke is named as a co-inventor on patents for the use of oxidation and protein markers to predict the risk of cardiovascular disease. All other authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnlov J, Evans JC, Meigs JB, Wang TJ, Fox CS, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS. Low-grade albuminuria and incidence of cardiovascular disease events in nonhypertensive and nondiabetic individuals: The framingham heart study. Circulation. 2005;112:969–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillege HL, Fidler V, Diercks GF, van Gilst WH, de Zeeuw D, van Veldhuisen DJ, Gans RO, Janssen WM, Grobbee DE, de Jong PE. Urinary albumin excretion predicts cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality in general population. Circulation. 2002;106:1777–1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klausen K, Borch-Johnsen K, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Jensen G, Clausen P, Scharling H, Appleyard M, Jensen JS. Very low levels of microalbuminuria are associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease and death independently of renal function, hypertension, and diabetes. Circulation. 2004;110:32–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox CS, Matsushita K, Woodward M, et al. Associations of kidney disease measures with mortality and end-stage renal disease in individuals with and without diabetes: A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380:1662–1673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Boer IH, Afkarian M, Rue TC, Cleary PA, Lachin JM, Molitch ME, Steffes MW, Sun W, Zinman B. Renal outcomes in patients with type 1 diabetes and macroalbuminuria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2342–2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Velde M, Matsushita K, Coresh J, et al. Lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and higher albuminuria are associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. A collaborative meta-analysis of high-risk population cohorts. Kidney international. 2011;79:1341–1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Boer IH, Astor BC, Kramer H, Palmas W, Rudser K, Seliger SL, Shlipak MG, Siscovick DS, Tsai MY, Kestenbaum B. Mild elevations of urine albumin excretion are associated with atherogenic lipoprotein abnormalities in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (mesa). Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:407–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganjali S, Dallinga-Thie GM, Simental-Mendia LE, Banach M, Pirro M, Sahebkar A. Hdl functionality in type 1 diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2017;267:99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwab KO, Doerfer J, Hecker W, Grulich-Henn J, Wiemann D, Kordonouri O, Beyer P, Holl RW. Spectrum and prevalence of atherogenic risk factors in 27,358 children, adolescents, and young adults with type 1 diabetes: Cross-sectional data from the german diabetes documentation and quality management system (dpv). Diabetes Care. 2006;29:218–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Ferranti SD, de Boer IH, Fonseca V, Fox CS, Golden SH, Lavie CJ, Magge SN, Marx N, McGuire DK, Orchard TJ, Zinman B, Eckel RH. Type 1 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the american heart association and american diabetes association. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2843–2863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon DJ, Rifkind BM. High-density lipoprotein--the clinical implications of recent studies. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1311–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson PW, Abbott RD, Castelli WP. High density lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality. The framingham heart study. Arteriosclerosis. 1988;8:737–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hegele RA. Cetp inhibitors - a new inning? N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1284–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rader DJ, Tall AR. The not-so-simple hdl story: Is it time to revise the hdl cholesterol hypothesis? Nature medicine. 2012;18:1344–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rigotti A, Trigatti BL, Penman M, Rayburn H, Herz J, Krieger M. A targeted mutation in the murine gene encoding the high density lipoprotein (hdl) receptor scavenger receptor class b type i reveals its key role in hdl metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12610–12615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zanoni P, Khetarpal SA, Larach DB, et al. Rare variant in scavenger receptor bi raises hdl cholesterol and increases risk of coronary heart disease. Science. 2016;351:1166–1171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaisar T, Pennathur S, Green PS, et al. Shotgun proteomics implicates protease inhibition and complement activation in the antiinflammatory properties of hdl. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:746–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shao B, de Boer I, Tang C, Mayer PS, Zelnick L, Afkarian M, Heinecke JW, Himmelfarb J. A cluster of proteins implicated in kidney disease is increased in high-density lipoprotein isolated from hemodialysis subjects. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:2792–2806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polonsky TS, McClelland RL, Jorgensen NW, Bild DE, Burke GL, Guerci AD, Greenland P. Coronary artery calcium score and risk classification for coronary heart disease prediction. JAMA. 2010;303:1610–1616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications (edic). Design, implementation, and preliminary results of a long-term follow-up of the diabetes control and complications trial cohort. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:99–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marsillach J, Becker JO, Vaisar T, Hahn BH, Brunzell JD, Furlong CE, de Boer IH, McMahon MA, Hoofnagle AN. Paraoxonase-3 is depleted from the high-density lipoproteins of autoimmune disease patients with subclinical atherosclerosis. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:2046–2054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Boer IH. Kidney disease and related findings in the diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:24–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nathan DM. The diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study at 30 years: Overview. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:9–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cleary PA, Orchard TJ, Genuth S, Wong ND, Detrano R, Backlund JY, Zinman B, Jacobson A, Sun W, Lachin JM, Nathan DM. The effect of intensive glycemic treatment on coronary artery calcification in type 1 diabetic participants of the diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications (dcct/edic) study. Diabetes. 2006;55:3556–3565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shao B, Pennathur S, Heinecke JW. Myeloperoxidase targets apolipoprotein a-i, the major high density lipoprotein protein, for site-specific oxidation in human atherosclerotic lesions. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:6375–6386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan RO, Forte TM, Oda MN. Optimized bacterial expression of human apolipoprotein a-i. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;27:98–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacLean B, Tomazela DM, Shulman N, Chambers M, Finney GL, Frewen B, Kern R, Tabb DL, Liebler DC, MacCoss MJ. Skyline: An open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:966–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richter RJ, Jarvik GP, Furlong CE. Determination of paraoxonase 1 status without the use of toxic organophosphate substrates. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2008;1:147–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dabelea D, Kinney G, Snell-Bergeon JK, Hokanson JE, Eckel RH, Ehrlich J, Garg S, Hamman RF, Rewers M. Effect of type 1 diabetes on the gender difference in coronary artery calcification: A role for insulin resistance? The coronary artery calcification in type 1 diabetes (cacti) study. Diabetes. 2003;52:2833–2839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khera AV, Cuchel M, de la Llera-Moya M, Rodrigues A, Burke MF, Jafri K, French BC, Phillips JA, Mucksavage ML, Wilensky RL, Mohler ER, Rothblat GH, Rader DJ. Cholesterol efflux capacity, high-density lipoprotein function, and atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:127–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerstein HC, Mann JF, Yi Q, Zinman B, Dinneen SF, Hoogwerf B, Halle JP, Young J, Rashkow A, Joyce C, Nawaz S, Yusuf S. Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. JAMA. 2001;286:421–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mackness B, Durrington PN, Mackness MI. The paraoxonase gene family and coronary heart disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:357–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Draganov DI, Stetson PL, Watson CE, Billecke SS, La Du BN. Rabbit serum paraoxonase 3 (pon3) is a high density lipoprotein-associated lactonase and protects low density lipoprotein against oxidation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33435–33442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Precourt LP, Amre D, Denis MC, Lavoie JC, Delvin E, Seidman E, Levy E. The three-gene paraoxonase family: Physiologic roles, actions and regulation. Atherosclerosis. 2011;214:20–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reddy ST, Wadleigh DJ, Grijalva V, Ng C, Hama S, Gangopadhyay A, Shih DM, Lusis AJ, Navab M, Fogelman AM. Human paraoxonase-3 is an hdl-associated enzyme with biological activity similar to paraoxonase-1 protein but is not regulated by oxidized lipids. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:542–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng CJ, Wadleigh DJ, Gangopadhyay A, Hama S, Grijalva VR, Navab M, Fogelman AM, Reddy ST. Paraoxonase-2 is a ubiquitously expressed protein with antioxidant properties and is capable of preventing cell-mediated oxidative modification of low density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44444–44449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shih DM, Gu L, Xia YR, Navab M, Li WF, Hama S, Castellani LW, Furlong CE, Costa LG, Fogelman AM, Lusis AJ. Mice lacking serum paraoxonase are susceptible to organophosphate toxicity and atherosclerosis. Nature. 1998;394:284–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shih DM, Xia YR, Wang XP, Miller E, Castellani LW, Subbanagounder G, Cheroutre H, Faull KF, Berliner JA, Witztum JL, Lusis AJ. Combined serum paraoxonase knockout/apolipoprotein e knockout mice exhibit increased lipoprotein oxidation and atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17527–17535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rozenberg O, Shih DM, Aviram M. Paraoxonase 1 (pon1) attenuates macrophage oxidative status: Studies in pon1 transfected cells and in pon1 transgenic mice. Atherosclerosis. 2005;181:9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tward A, Xia YR, Wang XP, Shi YS, Park C, Castellani LW, Lusis AJ, Shih DM. Decreased atherosclerotic lesion formation in human serum paraoxonase transgenic mice. Circulation. 2002;106:484–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ayub A, Mackness MI, Arrol S, Mackness B, Patel J, Durrington PN. Serum paraoxonase after myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:330–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Azarsiz E, Kayikcioglu M, Payzin S, Yildirim Sozmen E. Pon1 activities and oxidative markers of ldl in patients with angiographically proven coronary artery disease. International journal of cardiology. 2003;91:43–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhattacharyya T, Nicholls SJ, Topol EJ, Zhang R, Yang X, Schmitt D, Fu X, Shao M, Brennan DM, Ellis SG, Brennan ML, Allayee H, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Relationship of paraoxonase 1 (pon1) gene polymorphisms and functional activity with systemic oxidative stress and cardiovascular risk. JAMA. 2008;299:1265–1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jarvik GP, Rozek LS, Brophy VH, Hatsukami TS, Richter RJ, Schellenberg GD, Furlong CE. Paraoxonase (pon1) phenotype is a better predictor of vascular disease than is pon1(192) or pon1(55) genotype. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2441–2447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mackness B, Davies GK, Turkie W, Lee E, Roberts DH, Hill E, Roberts C, Durrington PN, Mackness MI. Paraoxonase status in coronary heart disease: Are activity and concentration more important than genotype? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1451–1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wheeler JG, Keavney BD, Watkins H, Collins R, Danesh J. Four paraoxonase gene polymorphisms in 11212 cases of coronary heart disease and 12786 controls: Meta-analysis of 43 studies. Lancet. 2004;363:689–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Odawara M, Tachi Y, Yamashita K. Paraoxonase polymorphism (gln192-arg) is associated with coronary heart disease in japanese noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:2257–2260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suehiro T, Nakauchi Y, Yamamoto M, Arii K, Itoh H, Hamashige N, Hashimoto K. Paraoxonase gene polymorphism in japanese subjects with coronary heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 1996;57:69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang WH, Hartiala J, Fan Y, Wu Y, Stewart AF, Erdmann J, Kathiresan S, Roberts R, McPherson R, Allayee H, Hazen SL. Clinical and genetic association of serum paraoxonase and arylesterase activities with cardiovascular risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:2803–2812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Corsetti JP, Gansevoort RT, Bakker SJ, Navis G, Sparks CE, Dullaart RP. Apolipoprotein e predicts incident cardiovascular disease risk in women but not in men with concurrently high levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and c-reactive protein. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2012;61:996–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perkins BA, Bebu I, de Boer IH, Molitch M, Tamborlane W, Lorenzi G, Herman W, White NH, Pop-Busui R, Paterson AD, Orchard T, Cowie C, Lachin JM. Risk factors for kidney disease in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karthikeyan VJ, Lip GY. Alpha 1-microglobulin: A further insight into inflammation in hypertension? Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:1022–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin J, Glynn RJ, Rifai N, Manson JE, Ridker PM, Nathan DM, Schaumberg DA. Inflammation and progressive nephropathy in type 1 diabetes in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2338–2343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holzer M, Birner-Gruenberger R, Stojakovic T, El-Gamal D, Binder V, Wadsack C, Heinemann A, Marsche G. Uremia alters hdl composition and function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1631–1641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weichhart T, Kopecky C, Kubicek M, et al. Serum amyloid a in uremic hdl promotes inflammation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:934–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vaisar T, Tang C, Babenko I, Hutchins P, Wimberger J, Suffredini AF, Heinecke JW. Inflammatory remodeling of the hdl proteome impairs cholesterol efflux capacity. J Lipid Res. 2015;56:1519–1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.