Abstract

Background:

Highly sensitized candidates on the transplant waitlist remain a significant challenge as current desensitization protocols have variable success rates of donor specific antibody (DSA) reduction. Therefore, improved therapies are needed. APRIL (proliferation-inducing ligand) and BLyS (B-lymphocyte stimulator) are critical survival factors for B-lymphocytes and plasma cells, which are the primary sources of alloantibody production. We examined the effect of APRIL/BLyS blockade on DSA in a murine kidney transplant model as a possible novel desensitization strategy.

Methods:

C57BL/6 mice were sensitized with intraperitoneal injections of 2 × 106 BALB/c splenocytes. Twenty-one days following sensitization, animals were treated with 100μg of BLyS blockade (BAFFR-Ig) or APRIL/BLyS blockade (TACI-Ig), administered thrice weekly for an additional 21 days. Animals were then sacrificed or randomized to kidney transplant with Control Ig, BLyS blockade, or APRIL/BLyS blockade. Animals were sacrificed 7 days post-transplant. B-lymphocytes and DSA of BLyS blockade only or APRIL/BLyS blockade-treated mice were assessed by flow cytometry, IHC, and ELISPOT.

Results:

APRIL/BLyS inhibition resulted in a significant reduction of DSA by flow crossmatch compared to controls (p<0.01). APRIL/BLyS blockade also significantly depleted IgM and IgG secreting cells and B-lymphocyte populations compared to controls (p<0.0001). APRIL/BLyS blockade in transplanted mice also resulted in decreased B lymphocyte populations; however, no difference in rejection rates were seen between groups.

Conclusions:

APRIL/BLyS blockade with TACI-Ig significantly depleted B-lymphocytes and reduced DSA in this sensitized murine model. APRIL/BLyS inhibition may be a clinically useful desensitization strategy for sensitized transplant candidates.

Introduction:

Alloantibody directed against graft major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens is a significant barrier to solid organ transplantation for allosensitized patients. Currently, approximately 30,000 patients on the United Network for Organ Sharing kidney transplant waitlist are considered highly sensitized with a calculated panel reactive antibody (cPRA) ≥80%.1 These patients develop alloantibodies against MHC antigens through exposures to blood transfusions, pregnancy, and previous transplants. As a result, it is often difficult to find a compatible donor organ, which leads to increased wait times and mortality rates among patients awaiting transplant.2–4

Desensitization to alloantibody is an option for highly sensitized patients. Recent data suggest an overall survival advantage with current desensitization strategies as compared to dialysis for patients with pre-existing human leukocyte antigen (HLA) antibodies, although disagreement remains.4–5 In general, desensitization protocols focus on targeting B-lymphocytes (ie, anti-CD20 antibodies), antibody removal and modulation (ie, plasmapheresis, Immunoglobulin G-degrading enzyme of Streptococcus pyogenes (IdeS), intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)), and depletion of plasma cells (ie, bortezomib).6–9 The optimal desensitization protocol, however, has yet to be defined with mixed short-term and long-term results.10 As such, new agents that are safe and effective are needed.

APRIL (a proliferation-inducing ligand) and BLyS (B lymphocyte stimulator) are critical survival factors for both B-lymphocytes and terminally differentiated plasma cells.11–16 Recent clinical studies targeting BLyS demonstrated minor reduction in alloantibody as measured by the cPRA, but the reduction was not clinically significant.17 Another study found significant reductions in memory B-lymphocytes and circulating plasmablasts.18 We tested both BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockade in a murine model of ABMR.

Materials and Methods:

Animals

C57BL/6 (H-2b), BALB/c (H-2d), CBA (H2k) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and housed in the University of Wisconsin Laboratory Animal Facility. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Policies at University of Wisconsin. Mice were randomized into 6 experimental groups: no treatment (nonsensitized); 21d (sensitized, harvested 21d post-sensitization); 42d sensitized (sensitized, harvested 42d post-sensitization); cyclosporine A (CsA) (sensitized, treated with CsA) (30mg/kg daily); BLyS blockade (sensitized, treated with BAFFR-Ig (B cell activating factor receptor-Immunoglobulin) (100 μg BAFFR-Ig in PBS, i.p. injection 3x/week for 3 weeks)) 21d post-sensitization; APRIL/BLyS blockade (sensitized, treated with TACI-Ig (Transmembrane activator and calcium modulator and cyclophilin ligand interactor-Immunoglobulin) (100 μg TACI-Ig in PBS, i.p. injection 3x/week for 3 weeks)) 21d post-sensitization. TACI-Ig blocked both APRIL and BLyS, and BAFFR-Ig blocked BLyS alone. Animals were sensitized with 2×106 purified splenocytes i.p. Tissues were collected 21d or 42d post-sensitization.

Transplanted mice were randomized into three groups. At 21d post-sensitization, animals were transplanted with a BALB/c kidney, underwent nephrectomy, and were treated with BLyS blockade, APRIL/BLyS blockade or Control Ig (100 μg i.p. injection 3x/week for 3 weeks), as well as 30 mg/kg daily of CsA to prevent rejection. The contralateral native kidney was removed 1d later, leaving the animals to rely solely on the transplanted kidney.

Flow Cytometry

Single cell suspensions of splenocytes, bone marrow, and mesenteric lymph nodes were prepared from fresh cells. Flow methods were similar to Allman and Gross.13,19 Antibodies used: anti-IgD (11–26c.2a), anti-CD45R (B220) (RA3–6B2), anti-CD24 (M1/69), anti-IgM (R6–60.2), anti-CD3 (17A2), anti-CD27 (LG.3A10), anti-CD38 (90/CD38), anti-CD138 (281–2), anti-CD21 (7G6), anti-CD5 (clone 53–7.3 BD Pharmingen), anti-CD23 (B3B4), anti-CD25 (PC61), anti-CD4 (GK1.5), anti-CD8α (53–6.7), anti-FOXP3 (150 D). Flow cytometry was performed on a BD LSR II or BD LSR Fortessa at the UWCCC Flow Cytometry Laboratory and data analyzed with FlowJo (TreeStar, Inc., Ashland, OR).

B-lymphocyte subset determination/gating

Cells were gated to remove nonsinglets, then a tight lymphocyte gate, through a CD3- gate and were visualized as IgM versus CD21. CD21+IgM+ (mature B-lymphocytes), CD21++ IgM++ (transitional 2 marginal zone (T2 MZ) lymphocytes) and CD21-IgM++ (transitional 1 (T1) B-lymphocytes) gates were drawn. In addition, CD45R versus CD5 were gated as CD45R+CD5- cells then visualized as CD23 versus CD21. Gates were drawn for CD21+CD23- (marginal zone (MZ) B-lymphocytes), CD21-CD23- (naïve B-lymphocytes) and CD23int CD23+ (follicular (Fo) B-lymphocytes). Plasma cells were defined as CD45R-IgD-CD27+IgM-CD138+.

T lymphocyte subset gating

Cells were gated to remove nonsinglets, then gated through a lymphocyte gate and visualized as CD3 versus FSC-A, with the CD3+ gate further gated as CD4+ and CD8+. The CD4+ gate was visualized as CD25 versus FOXP3 with the CD25+FOXP3+ cells gated as Tregs.

Flow crossmatch

Flow crossmatch was performed essentially as described.20 Briefly, donor (BALB/c H2d) or third-party (CBA H2k) splenocytes were freshly isolated from spleen. Cells were suspended, counted, and 500,000 cells were aliquoted into cluster tubes for staining. Serum or plasma from experimental time points was diluted 1:8 in RPMI with 10% fetal calf serum for a total volume of 50 μl and added to the cells for 30 min at room temperature (RT), then washed and cells were stained for mouse IgG. Antibodies used include: anti-IgG (Poly4053), anti-CD3 (17A2). Cells were gated to remove nonsinglets through a lymphocyte gate and then a CD3+ gate. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was determined for the population of interest.

Histology

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded kidneys were cut into 5 μm sections. Slides were de-paraffinized, rehydrated from xylene through a graded ethanol series to ddH2O and subsequently treated as described below. Immunoperoxidase staining was done as previously described.21,22 Tissue sections were washed in distilled water, counter-stained with hematoxylin and dehydrated through an ethanol series. The following antibodies were used for immunohistochemical studies: Rat anti-C4d (200–1; American Research Products, Waltham, MA; Cat. No. 12–5000). Sections were stained with anti-PAX5 (Abcam, ab140341 polyclonal) antibody overnight. Slides were imaged on a Nikon Eclipse E600 supplied with an Olympus DP70 camera. Quantification was performed using a custom macro written for ImageJ software (NIH, imagej.nih.gov/ij/). 3–5 nonoverlapping pictures of representative slides were taken from at least 3 animals per group for Image J analysis. All H&E, PAS and C4d slides were reviewed by Dr. Weixiong Zhong, MD, PhD, transplant pathologist, and scored according to Banff 2013.23

Antibody Secreting Cell (ASC) ELISPOTs

ASC ELISPOTs were performed as previously described.24 Briefly, cells were incubated overnight on a plate coated with capture antibody (anti-IgM or anti-IgG antibody). Plates were washed and incubated with biotinylated anti-IgM or anti-IgG antibody, washed again and incubated with streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate. Plates were developed with BCIP/NBT substrate (MabTech) until distinct spots appeared. Color development was stopped by extensively washing with water. After drying, spots were quantified using dissecting microscope.

Statistics

Primary statistical tests were ANOVA, Mann-Whitney, and T-tests. For sensitized animals, test groups were compared to the sensitized, no treatment group. For transplanted mice, test groups were compared to animals given Control Ig.

Results:

APRIL/BLyS blockade, but not BLyS blockade alone, decreased donor specific antibodies (DSA)

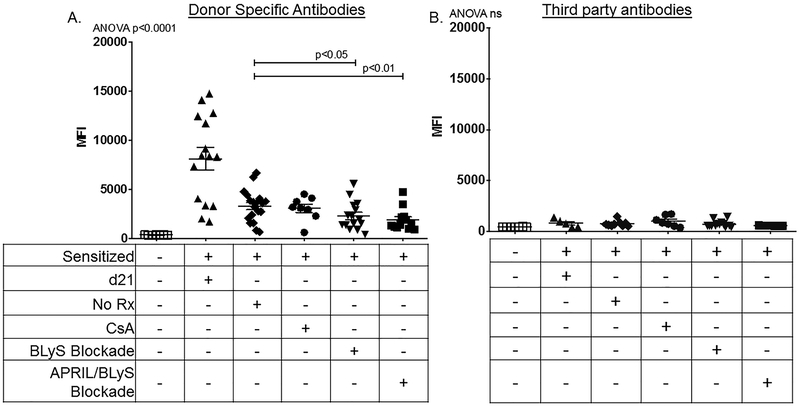

To determine the effect of APRIL/BLyS blockade and BLyS blockade on pre-existing alloantibodies, we sensitized C57BL/6 mice (H2b) with BALB/c splenocytes (H2d), then assessed the effect of APRIL/BLyS blockade and BLyS blockade 3x/week for an additional 21d following sensitization period (Figure 1, Table 1). As expected, sensitized mice at d21 had increased DSA compared to baseline nonsensitized mice at 21d and also at 42d. Sensitized mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade were found to have significantly lower DSA than sensitized untreated mice (p<0.01). Additionally, mice treated with BLyS blockade also significantly reduced DSA compared to sensitized control (p<0.05) (Figure 2A). Using CBA splenocytes as third-party targets (H2k), little reactivity was observed (Figure 2B), which indicates the antibody produced was in fact donor specific.

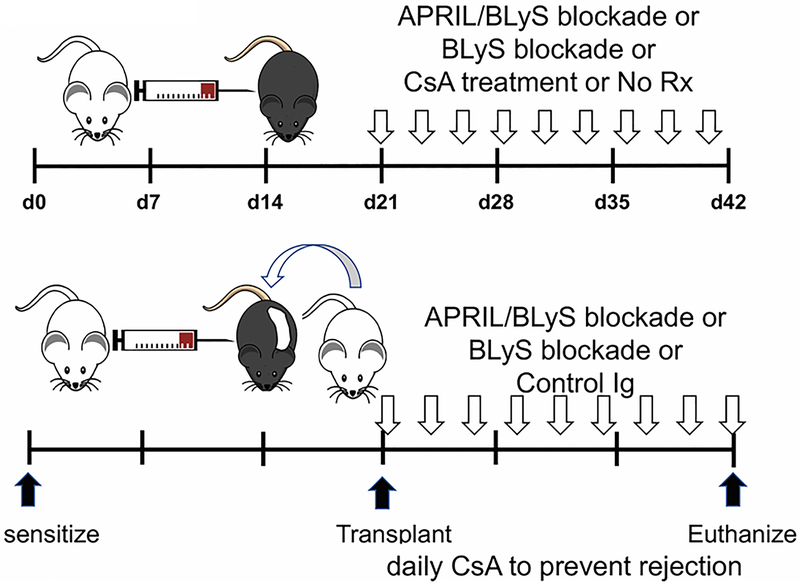

Figure 1. Experimental methodology: Mice were sensitized with a complete MHC mismatch, then desensitized with BLyS or APRIL/BLyS blockade.

Mice were sensitized by injection of 2 × 106 purified BALB/c splenocytes i.p. After 21 days, sensitized mice were either euthanized, left untreated for an additional 21 days, treated for 21d with 30 mg/kg daily cyclosporine A (CsA), treated with BLyS blockade 3x/week for 3 weeks, treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade 3x/week for 3 weeks. Transplanted mice were likewise sensitized, then treated with a BLyS blockade, APRIL/BLyS blockade or Control Ig blockade (Control Ig contains only the immunoglobulin portion of the BLyS or APRIL/BLyS reagent, 3 times weekly) at time of transplant. All transplanted mice received 30 mg/kg CsA daily to help prevent rejection. Except for the 21d group, all animals were euthanized on d42 post sensitization.

Table 1. Animals were distributed into experimental groups.

Treatments are indicated in the first column and group names are indicated in the top row. Next to the group name is an indication of how many animals were included in the group. The transplant animal group has been highlighted with a thicker border to make them easier to identify.

| Baseline n=7 | 21d euthanize n=6 | Sensitized, No Rx n=18 | Sensitized, CsA n=8 | Sensitized + BLyS blockade n=16 | Sensitized + APRIL /BLyS blockade n=13 | Transplant, BLyS blockade n=6 | Transplant APRIL /BLyS blockade n=3 | Transplant, Control Ig n=6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitized | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Euthanized, 21d | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| No Treatment | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CsA | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | + |

| BLyS blockade | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| APRIL/BLyS blockade | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| Control Ig | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Transplant | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + |

Figure 2. Donor Specific Antibodies were reduced after treatment with APRIL/BLyS blockade, but not BLyS blockade alone.

Symbols represent baseline nonsensitized mice ( ); sensitized d21 mice (

); sensitized d21 mice ( ); sensitized untreated mice (

); sensitized untreated mice ( ); sensitized mice treated with 30 mg/kg CsA daily (

); sensitized mice treated with 30 mg/kg CsA daily ( ); sensitized mice treated with BLyS blockade (

); sensitized mice treated with BLyS blockade ( ); sensitized mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade (

); sensitized mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade ( ). A) Flow crossmatch was performed by incubating sera with BALB/c (H2d) splenocytes. In all figures, the tables below the figures indicate the treatments that were given to each group. No Rx means no treatment for 21 days after the 21 day sensitization period. We observed a significant decrease in circulating DSA in sensitized mice given APRIL/BLyS blockade compared with sensitized untreated mice (P < 0.01). We observed a significant decrease in DSA in BLyS blockade only treated mice when compared to sensitized untreated mice (P < 0.05). B) We tested for third party alloantibodies by repeating the flow crossmatch using CBA (H2k) splenocytes. Very little reactivity was observed, and none was significantly different between groups.

). A) Flow crossmatch was performed by incubating sera with BALB/c (H2d) splenocytes. In all figures, the tables below the figures indicate the treatments that were given to each group. No Rx means no treatment for 21 days after the 21 day sensitization period. We observed a significant decrease in circulating DSA in sensitized mice given APRIL/BLyS blockade compared with sensitized untreated mice (P < 0.01). We observed a significant decrease in DSA in BLyS blockade only treated mice when compared to sensitized untreated mice (P < 0.05). B) We tested for third party alloantibodies by repeating the flow crossmatch using CBA (H2k) splenocytes. Very little reactivity was observed, and none was significantly different between groups.

Mature B-lymphocyte subsets were reduced while newly formed B-lymphocyte subsets were increased with both APRIL/BLyS blockade and BLyS blockade

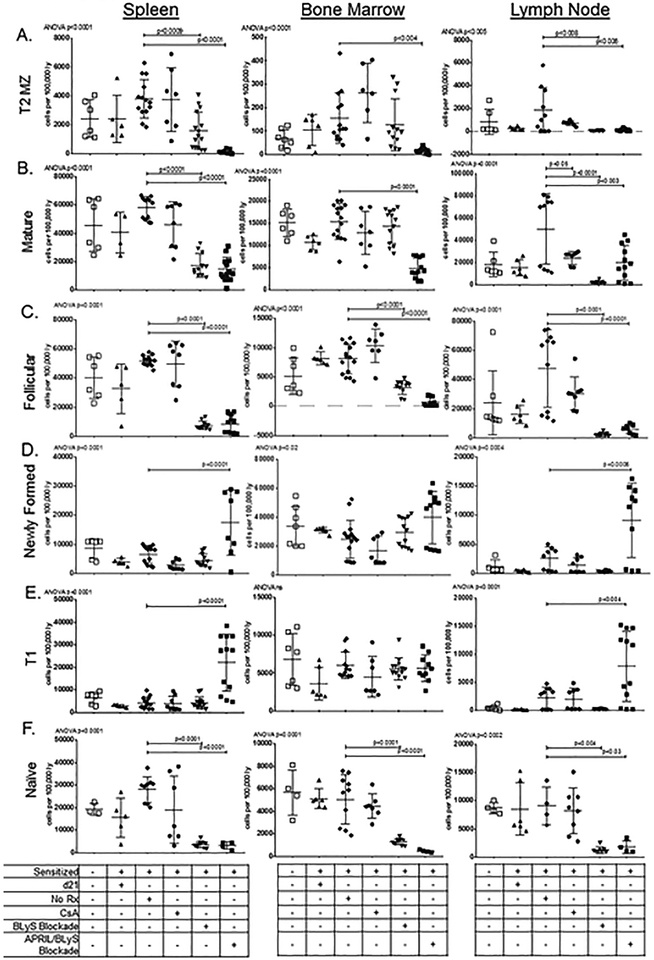

Mature B-lymphocyte subsets were evaluated, which included T2 MZ B-lymphocytes, mature B-lymphocytes, and Fo B-lymphocytes. BLyS blockade significantly reduced all 3 subsets in spleen (p<0.0009) and LN (p<0.008), and Fo B cells in BM (p<0.001). In comparison, APRIL/BLyS blockade significantly decreased all 3 mature B lymphocyte subsets in all tissues compared to sensitized control (p<0.006) (Figure 3A–C). Naïve B cells were depleted with BLyS blockade (p<0.0001) as well as APRIL/BLyS blockade (p<0.0001) in both BM and spleen and to a lesser extent in LNs (Figure 3F). Lastly, plasma cells were evaluated, but no significant changes were seen with BLyS or APRIL/BLyS blockade (data not shown).

Figure 3. APRIL/BLyS blockade had a significantly stronger effect on reduction of mature B-lymphocyte subsets than BLyS blockade alone.

Symbols represent baseline nonsensitized mice ( ); sensitized d21 mice (

); sensitized d21 mice ( ); sensitized untreated mice (

); sensitized untreated mice ( ); sensitized mice treated with 30 mg/kg CsA daily (

); sensitized mice treated with 30 mg/kg CsA daily ( ); sensitized mice treated with BLyS blockade (

); sensitized mice treated with BLyS blockade ( ); sensitized mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade (

); sensitized mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade ( ). Tissues were collected at time of euthanasia, 21 days after sensitization and after receiving 21 days of treatment. Control groups were held for the same amount of time, to ensure that they were age matched. Subsets are listed on the side, tissues are labeled on the top. All values are reported as number of cells per 100 000 lymphocytes. A) T2 MZ B-lymphocytes were significantly decreased in sensitized APRIL/BLyS blockade treated mice in spleen and BM when compared to sensitized untreated mice. Sensitized BLyS blockade-treated mice also had reduced numbers compared to untreated mice. B-C) BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockade both depleted mature and Fo B-lymphocytes in spleen and BM compared to sensitized untreated mice. APRIL/BLyS blockade reduced mature and Fo B-lymphocytes in BM compared to sensitized untreated mice. D) Sensitized mice receiving APRIL/BLyS blockade had a significant increase in newly formed B-lymphocytes in spleen (P < 0.0001) and LN (P < 0.0006). E) Similarly, T1 B-lymphocytes were significantly increased in APRIL/BLyS blockade-treated mice in both spleen and LN when compared to sensitized untreated controls. F) Naive B cells were strongly depleted in spleen, BM and LN by both BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockades.

). Tissues were collected at time of euthanasia, 21 days after sensitization and after receiving 21 days of treatment. Control groups were held for the same amount of time, to ensure that they were age matched. Subsets are listed on the side, tissues are labeled on the top. All values are reported as number of cells per 100 000 lymphocytes. A) T2 MZ B-lymphocytes were significantly decreased in sensitized APRIL/BLyS blockade treated mice in spleen and BM when compared to sensitized untreated mice. Sensitized BLyS blockade-treated mice also had reduced numbers compared to untreated mice. B-C) BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockade both depleted mature and Fo B-lymphocytes in spleen and BM compared to sensitized untreated mice. APRIL/BLyS blockade reduced mature and Fo B-lymphocytes in BM compared to sensitized untreated mice. D) Sensitized mice receiving APRIL/BLyS blockade had a significant increase in newly formed B-lymphocytes in spleen (P < 0.0001) and LN (P < 0.0006). E) Similarly, T1 B-lymphocytes were significantly increased in APRIL/BLyS blockade-treated mice in both spleen and LN when compared to sensitized untreated controls. F) Naive B cells were strongly depleted in spleen, BM and LN by both BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockades.

Early B-lymphocyte populations such as newly formed B-lymphocytes and T1 B-lymphocytes were significantly increased in mice receiving APRIL/BLyS blockade. Mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade demonstrated a significant increase in newly formed B-lymphocytes in spleen (p<0.0001) and LNs (p<0.0006) (Figure 3D). T1 B-lymphocytes were also significantly increased in spleen (p<0.0001) and LNs (p<0.004) in mice receiving APRIL/BLyS blockade compared to sensitized untreated mice (Figure 3E). These changes were not seen with BLyS blockade alone. This increase in early B-lymphocyte populations is likely because newly formed B and T1 B-lymphocytes do not rely on APRIL or BLyS for development and survival; therefore, they are not affected by APRIL/BLyS or BLyS blockade alone, but accumulate as they are unable to progress to more mature B-lymphocyte subsets.13,25

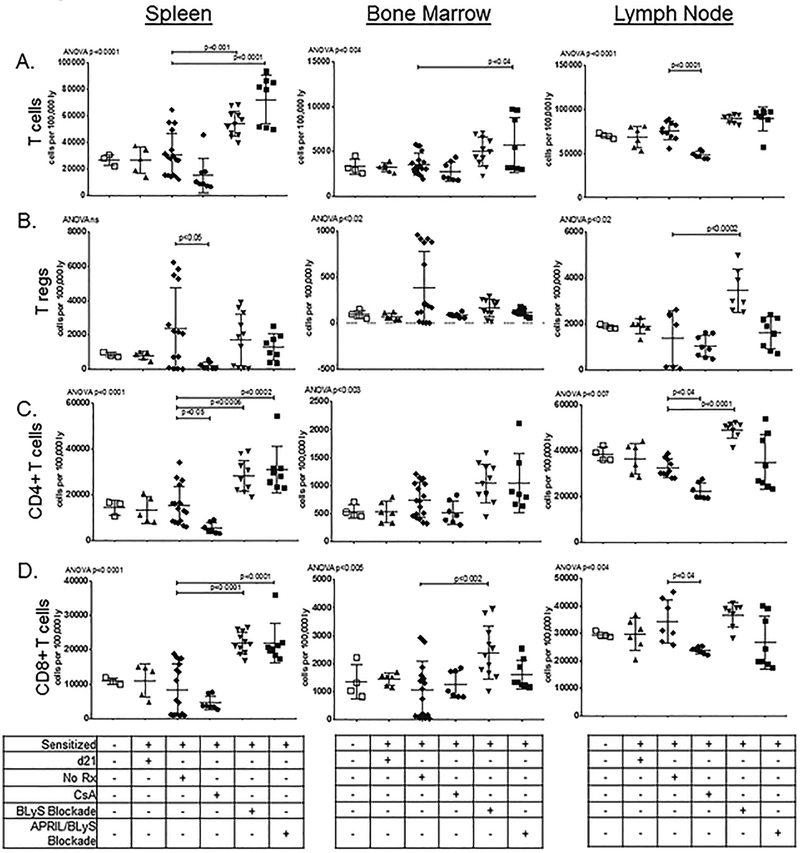

Treatment of sensitized mice with BLyS blockade or APRIL/BLyS blockade had differential effect on T cell populations

To examine the effect of BLyS or APRIL/BLyS blockade on T cell populations, we stained cells for T lymphocyte markers including CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25 and FoxP3 (Figure 4). Overall, total T cells were increased in spleen (p<0.0001) and BM (p<0.04) of APRIL/BLyS blockade treated mice, as well as increased in spleen (p<0.001) of BLyS blockade treated mice (Figure 4A). Interestingly, Tregs were increased in LNs of sensitized mice treated with BLyS blockade (p<0.0002), but this change was not seen in mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade (Figure 4B). Spleen CD4+ T cells were increased in both BLyS (p<0.0006) and APRIL/BLyS (p<0.0002) blockades with BLyS blockade also significantly increasing LN CD4+ T cells in LN (p<0.0001) compared to sensitized untreated animals (Figure 4C). CD8+ T cells were likewise increased in both BLyS (p<0.0001) and APRIL/BLyS (p<0.0001) blockade in spleen, but only BLyS blockade increased CD8+ T cell populations in BM (p<0.002) (Figure 4D). Data using CsA as treatment are presented for reference to established immunosuppression depleting agents. As expected, CsA treatment resulted in significantly decreased spleen CD4+ (p<0.05), LN CD4+ (p<0.04), and LN CD8+ T cells (p<0.04).

Figure 4. Significant changes in T-cell subsets were found in mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade and BLyS blockade.

Symbols represent baseline nonsensitized mice ( ); sensitized d21 mice (

); sensitized d21 mice ( ); sensitized untreated mice (

); sensitized untreated mice ( ); sensitized mice treated with 30 mg/kg CsA daily (

); sensitized mice treated with 30 mg/kg CsA daily ( ); sensitized mice treated with BLyS blockade (

); sensitized mice treated with BLyS blockade ( ); sensitized mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade (

); sensitized mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade ( ).We stained cells for CD3+, CD3+CD4+, CD3+CD8+, and for Tregs, CD25+FoxP3+ populations. A) Overall T cell populations were reduced in spleen and LNs of mice that were treated with CsA after 21d of sensitization. We also saw an overall increase in T cells in spleen with both BLyS blockade and APRIL/BLyS blockade. A less profound increase was also observed in BM of APRIL/BLyS blockade animals. In animals treated with CsA, a significant decrease in T cells was observed. B) Tregs were also depleted in splenocytes of animals that received CsA. Tregs were increased in sensitized mice treated with a BLyS blockade in LN. C) CD4+ T cells were increased in both BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockades and decreased with CsA treatment in spleen, but only BLyS blockade increased CD4+ T cells in LNs. D) CD8+ T cells were likewise increased in both BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockade in splenocytes, but only BLyS blockade increased CD8+ T cell populations in BM, no increase was seen in LN. A reduction in CD8+ T cells was observed in LN of CsA treated animals.

).We stained cells for CD3+, CD3+CD4+, CD3+CD8+, and for Tregs, CD25+FoxP3+ populations. A) Overall T cell populations were reduced in spleen and LNs of mice that were treated with CsA after 21d of sensitization. We also saw an overall increase in T cells in spleen with both BLyS blockade and APRIL/BLyS blockade. A less profound increase was also observed in BM of APRIL/BLyS blockade animals. In animals treated with CsA, a significant decrease in T cells was observed. B) Tregs were also depleted in splenocytes of animals that received CsA. Tregs were increased in sensitized mice treated with a BLyS blockade in LN. C) CD4+ T cells were increased in both BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockades and decreased with CsA treatment in spleen, but only BLyS blockade increased CD4+ T cells in LNs. D) CD8+ T cells were likewise increased in both BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockade in splenocytes, but only BLyS blockade increased CD8+ T cell populations in BM, no increase was seen in LN. A reduction in CD8+ T cells was observed in LN of CsA treated animals.

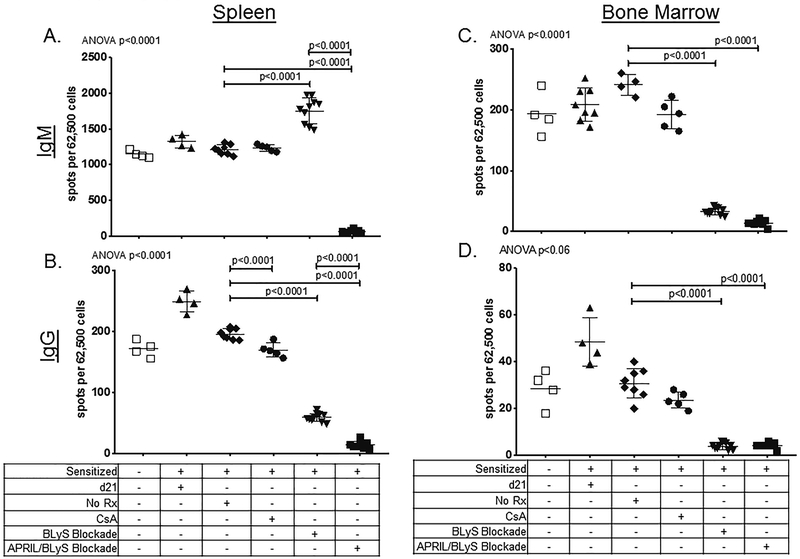

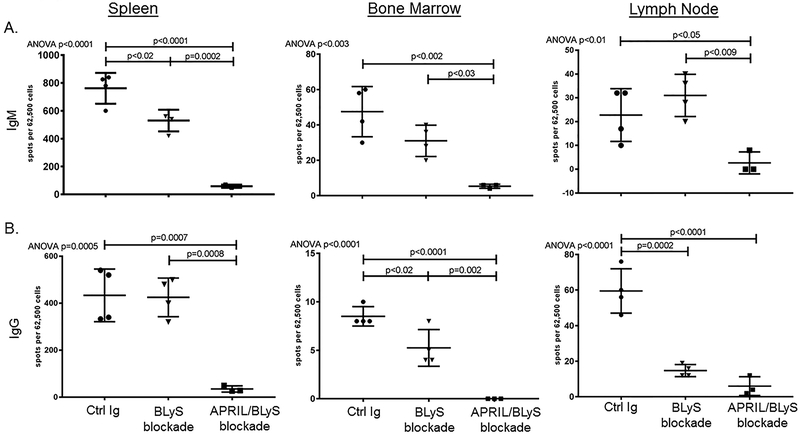

Treatment of sensitized mice with APRIL/BLyS blockade, but not BLyS blockade alone, reduces antibody secreting cells (ASCs) in spleen

We performed ASC ELISPOT to determine whether the observed reduction of B-lymphocyte subsets was accompanied by reduction in the number of cells able to produce IgM or IgG. ASC ELISPOT visualized B-lymphocytes, plasmablasts and plasma cells that produce antibody. ELISPOT data showed a decrease in spleen IgM (p<0.0001) and IgG (p<0.0001) secreting cells with APRIL/BLyS blockade compared to both sensitized control and BLyS blockade treated animals. By contrast, BLyS blockade was significantly less effective at depleting IgG secreting cells in spleen (p<0.0001) and had a significant increase in IgM secreting cells (p<0.0001) (Figure 5A–B). Both IgM and IgG secreting cells were depleted by both BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockade in BM (p<0.0001) (Figure 5C–D).

Figure 5. Antibody Secreting Cell (ASC) ELISPOT showed that treatment with APRIL/BLyS blockade had a profound effect on the ability of cells to secrete IgG or IgM.

Symbols represent baseline nonsensitized mice ( ); sensitized d21 mice (

); sensitized d21 mice ( ); sensitized untreated mice (

); sensitized untreated mice ( ); sensitized mice treated with 30 mg/kg CsA daily (

); sensitized mice treated with 30 mg/kg CsA daily ( ); sensitized mice treated with BLyS blockade (

); sensitized mice treated with BLyS blockade ( ); sensitized mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade (

); sensitized mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade ( ). A) In spleen, IgM secreting cells were significantly reduced by APRIL/BLyS blockade when compared to both sensitized untreated controls and BLyS blockade alone (P < 0.0001). BLyS blockade resulted in significantly increased spleen ASC producing IgM (P < 0.0001) compared to sensitized untreated. B) Both APRIL/BLyS blockade and BLyS blockade were able to significantly reduce spleen IgG secreting cells when compared to sensitized control (P < 0.0001). ASC from sensitized mice that received APRIL/BLyS blockade were also significantly reduced compared to BLyS blockade alone (P < 0.0001). C) Both APRIL/BLyS blockade and BLyS blockade significantly reduced IgM secreting cells in the BM (P < 0.0001). D) Both APRIL/BLyS and BLyS blockade were able to significantly decrease BM IgG secreting cells when compared to sensitized untreated controls (P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001).

). A) In spleen, IgM secreting cells were significantly reduced by APRIL/BLyS blockade when compared to both sensitized untreated controls and BLyS blockade alone (P < 0.0001). BLyS blockade resulted in significantly increased spleen ASC producing IgM (P < 0.0001) compared to sensitized untreated. B) Both APRIL/BLyS blockade and BLyS blockade were able to significantly reduce spleen IgG secreting cells when compared to sensitized control (P < 0.0001). ASC from sensitized mice that received APRIL/BLyS blockade were also significantly reduced compared to BLyS blockade alone (P < 0.0001). C) Both APRIL/BLyS blockade and BLyS blockade significantly reduced IgM secreting cells in the BM (P < 0.0001). D) Both APRIL/BLyS and BLyS blockade were able to significantly decrease BM IgG secreting cells when compared to sensitized untreated controls (P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001).

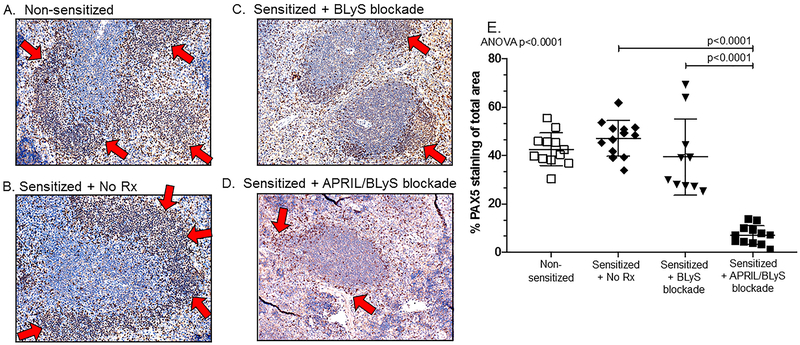

APRIL/BLyS blockade was more effective at depleting B-lymphocytes from splenic germinal centers than BLyS blockade alone

B-lymphocyte population reductions observed by flow cytometry were confirmed with IHC. Using PAX5 antibody to detect B-lymphocytes in paraffin-embedded spleen sections, the B-lymphocyte region of the germinal center in mice receiving APRIL/BLyS blockade was significantly disrupted and reduced (Figure 6). Red arrows point to the region of PAX5 staining designating the B cell zone. APRIL/BLyS blockade treated mice demonstrated significantly decreased PAX5 staining compared to BLyS blockade and sensitized untreated mice, indicating an overall depletion of B-lymphocytes in germinal centers (Figure 6E). There was no significant difference in germinal centers between sensitized untreated and BLyS blockade treated mice.

Figure 6. Treatment with APRIL/BLyS blockade largely eliminated B-lymphocytes from splenic germinal centers of sensitized mice.

PAX5 (brown) staining of paraffin embedded spleens demonstrated that B-lymphocytes were largely absent from germinal centers in sensitized mouse treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade. A) Nonsensitized control spleen had normal architecture of B-lymphocytes in spleen germinal centers, B-lymphocytes areas are indicated by arrows. B) Sensitized untreated mouse spleen had a well-developed germinal center with large population of B-lymphocytes (brown). C) Sensitized mouse spleen after BLyS blockade showed some diminishment of B-lymphocytes in the germinal center. D) Sensitized mouse spleen receiving APRIL/BLyS blockade was largely lacking B-lymphocytes around germinal center. E) Symbols represent baseline nonsensitized mice ( ); sensitized untreated mice (

); sensitized untreated mice ( ); sensitized mice treated with BLyS blockade (

); sensitized mice treated with BLyS blockade ( ); sensitized mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade (

); sensitized mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade ( ). Animals treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade had a significant decrease in the number of B-lymphocytes compared to both sensitized untreated animals (P < 0.0001) as well as to BLyS blockade alone (P < 0.0001).

). Animals treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade had a significant decrease in the number of B-lymphocytes compared to both sensitized untreated animals (P < 0.0001) as well as to BLyS blockade alone (P < 0.0001).

DSA were not reduced by APRIL/BLyS blockade in murine ABMR transplant model

Next we used BLyS blockade and APRIL/BLyS blockade in a sensitized murine kidney transplant model. Mice were sensitized, transplanted on d21 post-sensitization, and then treated with Control Ig, BLyS blockade or APRIL/BLyS blockade to determine the effect on B-lymphocyte subsets and rejection. All mice were concomitantly treated with 30 mg/kg CsA to prevent overt rejection. While there is a reduction in DSA in the APRIL/BLyS blockade group compared to the Control Ig treatment group, it was not significant, and no third party allospecific antibodies were observed (data not shown).

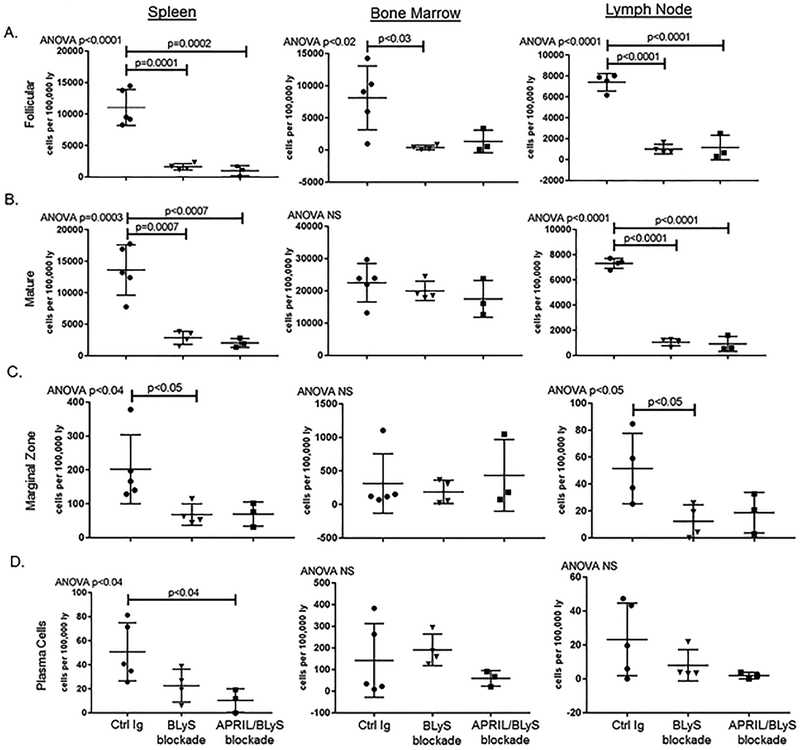

BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockade reduced B-lymphocyte subsets in transplant mice

We assessed changes in B-lymphocyte subsets after transplant. Both BLyS (p≤0.0007) and APRIL/BLyS (p<0.0007) blockades were able to significantly reduce Fo and mature B-lymphocytes in spleen and LN (Figure 7A–B). Marginal zone B-lymphocytes were also reduced by BLyS blockade (p<0.05) in spleen and LN (Figure 7C). Significant reductions in plasma cell populations were only found in the spleen of transplanted mice that received APRIL/BLyS blockade (p<0.04) (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. In transplanted mice, both APRIL/BLyS blockade and BLyS blockade reduced mature B-lymphocyte subsets but did not have an effect on early B-lymphocytes subsets.

Symbols represent sensitized, transplanted mice treated with Control Ig ( ); BLyS blockade (

); BLyS blockade ( ); or APRIL/BLyS blockade (

); or APRIL/BLyS blockade ( ). All mice also received 30 mg/kg CsA daily after transplant. A) APRIL/BLyS blockade significantly reduced follicular B-lymphocyte subsets compared with Control Ig treated mice in spleen and LNs, but while BM follicular B-lymphocytes were reduced for both treatments, only BLyS blockade was significant. B) Mature B-lymphocytes were reduced in spleen and LNs in transplanted mice for both BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockades, but not in BM. C) Marginal zone B-lymphocytes were reduced by both BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockades, but only significantly for BLyS blockade. D) Plasma cells were significantly reduced in spleens of mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade.

). All mice also received 30 mg/kg CsA daily after transplant. A) APRIL/BLyS blockade significantly reduced follicular B-lymphocyte subsets compared with Control Ig treated mice in spleen and LNs, but while BM follicular B-lymphocytes were reduced for both treatments, only BLyS blockade was significant. B) Mature B-lymphocytes were reduced in spleen and LNs in transplanted mice for both BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockades, but not in BM. C) Marginal zone B-lymphocytes were reduced by both BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockades, but only significantly for BLyS blockade. D) Plasma cells were significantly reduced in spleens of mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade.

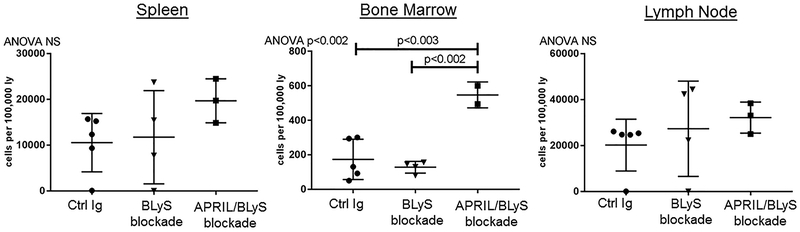

APRIL/BLyS blockade increased BM CD4+ T cells in transplant mice

We examined T cell subsets, by staining tissues from transplanted mice with CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25 and FoxP3. Similar to results seen in the sensitized nontransplant model, APRIL/BLyS blockade resulted in a significant increase in BM CD3+CD4+ T lymphocytes compared to both transplant control and BLyS blockade treated groups (p<0.003) (Figure 8). No other changes in T lymphocyte subsets were found between transplanted groups.

Figure 8. Treatment with APRIL/BLyS blockade increased populations of CD4+ T lymphocytes in transplanted mice.

Symbols represent sensitized, transplanted mice treated with Control Ig ( ); BLyS blockade (

); BLyS blockade ( );APRIL/BLyS blockade (

);APRIL/BLyS blockade ( ). All mice also received 30 mg/kg CsA daily after transplant. Treatment with APRIL/BLyS blockade increased BM CD3+CD4+T lymphocytes compared to Control Ig and BLyS blockade, but no other populations (total T cells, CD8+ T cells, or regulatory T cells) were changed by any treatment.

). All mice also received 30 mg/kg CsA daily after transplant. Treatment with APRIL/BLyS blockade increased BM CD3+CD4+T lymphocytes compared to Control Ig and BLyS blockade, but no other populations (total T cells, CD8+ T cells, or regulatory T cells) were changed by any treatment.

In transplanted mice, similar reductions in antibody secreting cells were observed after BLyS and APRIL/BLyS blockade to that observed in sensitized mice

To determine whether treatment with APRIL/BLyS blockade or BLyS blockade changed numbers of antibody secreting cells in transplanted mice, we performed IgG and IgM ELISPOTs. We observed a profound reduction of IgM and IgG secreting cells in spleen (p=0.0007), BM (p<0.002), and LNs (p<0.05) of mice treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade compared to transplant control (Figure 9). Similarly, BLyS blockade resulted in an intermediate reduction of spleen IgM secreting cells (p<0.02) and BM (p<0.02) and LN (p=0.0002) IgG secreting cells compared to transplant control. Importantly, APRIL/BLyS blockade resulted in a significant reduction of IgM secreting cells in all tissues (p<0.03) and IgG secreting cells in spleen (p=0.0008) and BM (p=0.002) compared to BLyS blockade alone. While BLyS blockade has a partial effect, addition of APRIL blockade results in a nearly complete reduction of antibody secretion.

Figure 9. Antibody Secreting Cell ELISPOT showed that treatment with APRIL/BLyS blockade had a profound effect on the ability of cells to secrete IgG or IgM.

Symbols represent sensitized, transplanted mice treated with Control Ig ( ); BLyS blockade (

); BLyS blockade ( ); APRIL/BLyS blockade (

); APRIL/BLyS blockade ( ). All mice also received 30 mg/kg CsA daily after transplant. A) Treatment with APRIL/BLyS blockade was more effective in reducing numbers of IgM secreting cells than BLyS blockade alone in spleen, BM and LNs. B). By contrast, IgG secreting cells were not significantly reduced in the spleen by BLyS blockade, although BLyS blockade was able to reduce antibody secreting cells in BM and LN. APRIL/BLyS blockade significantly reduced spleen and BM IgG secreting cells compared to BLyS blockade alone.

). All mice also received 30 mg/kg CsA daily after transplant. A) Treatment with APRIL/BLyS blockade was more effective in reducing numbers of IgM secreting cells than BLyS blockade alone in spleen, BM and LNs. B). By contrast, IgG secreting cells were not significantly reduced in the spleen by BLyS blockade, although BLyS blockade was able to reduce antibody secreting cells in BM and LN. APRIL/BLyS blockade significantly reduced spleen and BM IgG secreting cells compared to BLyS blockade alone.

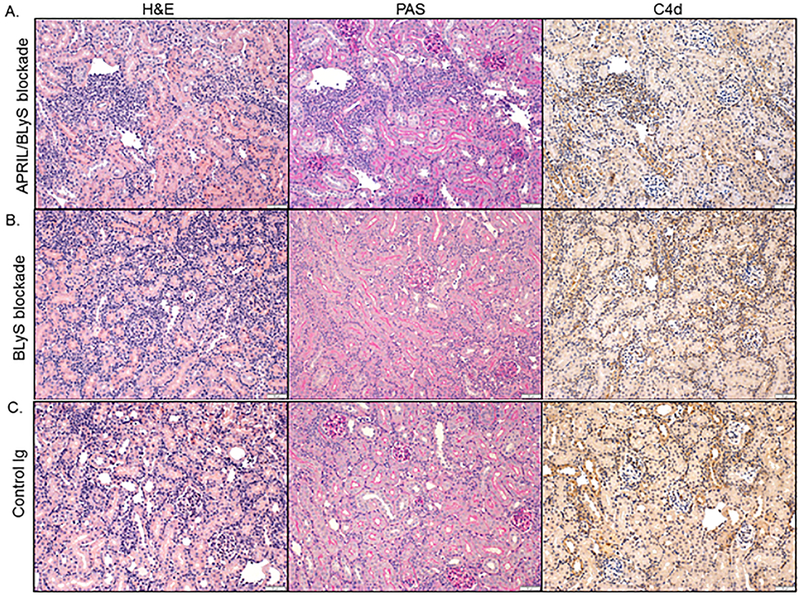

No changes in rejection seen with BLyS or APRIL/BLyS blockade

Lastly, transplanted kidneys were collected at the time of harvest and evaluated for signs of rejection. All pathology slides were reviewed by a transplant pathologist and scored for tubulitis (t), interstitial inflammation (i), glomerulitis (g), peritubular capillaritis (ptc), vasculitis (v), chronic glomerulopathy (cg), chronic interstitial fibrosis (ci), chronic tubular atrophy (ct), mesangial matrix increase (mm), arteriolar hyaline thickening (ah), vascular fibrous intimal thickening (cv) and C4d. Slides were then scored for T-cell mediated rejection (TCMR) and ABMR based on Banff classification.

Overall, no significant difference in TCMR severity was noted between transplant control, BLyS blockade, or APRIL/BLyS blockade. All reviewed kidney biopsies from animals receiving BLyS blockade developed TCMR IB as evidenced through the presence of severe interstitial inflammation. In comparison, 67% of animals in the transplant control and APRIL/BLyS blockade group developed TCMR IB and 33% developed TCMR IA (table 2). Similarly, moderate mvi (g + ptc ≥ 2) was found in 67% of BLyS blockade biopsies compared to 33% in both the transplant control and APRIL/BLyS blockade treatment group. No C4d deposition was noted in any group Figure 10).

Table 2. Kidneys from transplanted mice were analyzed using Banff criteria.23.

| Group | t | i | g | ah | v | ptc | cg | ci | ct | cv | mm | C4d | TCMR IB (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Ig | 2.7±0.6 | 3.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.7±1.2 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.3±0.6 | 0.3±0.6 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 66.7% (2) |

| BLyS blockade | 3.0±0.0 | 3.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 2.0±1.7 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 100% (3) |

| APRIL/BLyS blockade | 2.7±0.6 | 3.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.7±1.2 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.3±0.6 | 0.3±0.6 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 0.0±0.0 | 66.7% (2) |

Figure 10. BLyS or APRIL/BLyS blockade did not change immunohistochemical parameters in the kidney in transplanted mice.

No treatment changed inflammatory cell infiltration or C4d deposition in kidneys of sensitized transplanted animals that were given A) APRIL/BLyS blockade, B) BLyS blockade, compared to C) Control Ig treatment.

Despite significant improvement in pre-transplant DSA and reduction of B-lymphocyte subsets, no improvement was observed in kidney pathology with BLyS or APRIL/BLyS blockade.

Discussion:

We demonstrated that a rodent model of sensitization and subsequent blockade of both APRIL and BLyS was associated with greater reduction of the humoral immune system than BLyS blockade alone. In our pre-transplant model, APRIL/BLyS blockade resulted in superior depletion of DSA, mature B lymphocyte subsets, antibody secreting cells, and splenic germinal centers compared to sensitized control and BLyS blockade alone. Next we explored the effects of BLyS blockade and APRIL/BLyS blockade in a sensitized transplant model. Both of these treatments were able to significantly decrease mature B lymphocyte subsets with APRIL/BLyS blockade resulting in a profound depletion of antibody secreting cells compared to both transplant control and BLyS blockade. Despite these changes in B lymphocyte populations and antibody secreting cell production, neither BLyS blockade alone nor APRIL/BLyS blockade altered the development of DSA or kidney transplant rejection. One potential explanation for the lack of changes in histology is that an extended desensitization period may be required in order to successfully decrease rejection. Furthermore, the decrease of DSA but no difference seen on kidney pathology is an important reminder that DSA is a biomarker and does not necessarily reflect the pathology occurring in the kidney.

Our data suggest that one of the primary reasons for superior DSA reduction with APRIL/BLyS blockade was more effective targeting of B-lymphocytes due to the addition of APRIL blockade. In support of this, Benson et al examined the relationship between APRIL, BLyS, and plasma cells and determined that plasma cells require support from at least one of these cytokines for long-term plasma cell survival.26 Thus, targeting BLyS alone would be expected to deplete mature B-lymphocytes but be less effective at depleting plasma cells, the main source of alloantibody secretion, as confirmed by our data.17,26,27 Although the role of APRIL and BLyS in B-lymphocyte and plasma cell immunology has been well established, targeting of these two survival factors as a therapeutic strategy in transplantation is still evolving.

BLyS blockade has been investigated in multiple randomized controlled trials with encouraging results. In a study by Mujtaba et al, tabalumab (anti-BLyS) was given to highly sensitized patients awaiting kidney transplantation with the goal of reducing alloantibody.17 Although the BLyS inhibitor successfully reduced total immunoglobulin and resulted in a statistically significant decrease in cPRA, this reduction was transient and did not appear to be clinically significant. In agreement with our observations and as discussed in Mujtaba et al, sustained alloantibody reduction that has a clinical impact will likely need to target B-lymphocytes at multiple stages of development. For example, adding an APRIL blockade to the BLyS blockade could additionally target plasma cells, which are left completely untargeted by BLyS blockade alone.17 Additionally, Banham et al investigated belimumab (BLyS blockade) versus placebo in addition to standard of care immunosuppression in kidney transplant. Belimumab was found to significantly reduce memory B-lymphocytes, circulating plasmablasts and preformed IgG without any major increase in risk of infection. This trial offers further support to our findings and is encouraging of the results that anti-BLyS therapy may have in future studies.

In agreement with our findings, Kwun et al reported similar findings of decreased DSA and overall B-lymphocyte populations with APRIL/BLyS blockade in a preclinical nonhuman primate AMR (antibody mediated rejection) model.28 Animals were given induction therapy followed by atacicept (TACI-Ig) for combined APRIL/BLyS blockade after kidney transplantation. Compared to controls that received induction therapy alone, APRIL/BLyS blockade-treated animals had significantly decreased levels of early de novo DSA at 2 and 4 weeks post-transplantation and also had significantly smaller peripheral B-lymphocyte populations at 6 weeks post-transplantation. Graft survival more than doubled in the TACI-Ig treated animals compared to controls, although this was not found to be statistically significant. While the purpose of our study differed, the findings in Kwun et al offer further support for the utilization of APRIL/BLyS blockade as therapy for desensitization. In our study, we sought to address whether APRIL/BLyS blockade could reduce preformed DSA, in comparison to previous studies that demonstrated APRIL/BLyS blockade to be effective at prevention of DSA.

Additionally, our finding in this model that simultaneous APRIL/BLyS blockade decreased mature B-lymphocyte populations is supported by previous work in the autoimmune literature. Therapeutic targets of APRIL and/or BLyS have been tested for several autoimmune diseases in which pathogenic autoantibodies play a major role. Treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has utilized several FDA-approved APRIL and/or BLyS blocking therapies. Belimumab (anti-BLyS) was found to deplete transitional and naïve B-lymphocytes but resulted in a transient increase in memory cells.29,30 Similar to our study, APRIL/BLyS blockade (via TACI-Ig) versus BLyS blockade (via BAFFR-Ig) alone were compared in a murine model of SLE.31 APRIL/BLyS blockade was found to be superior to BLyS blockade in preventing renal damage, independent of autoantibody levels, and also correlated with a reduction of plasma cells.31 Similarly, in a rheumatoid arthritis (RA) murine model, APRIL/BLyS blockade was found to inhibit both humoral and cellular immune responses, resulting in reduced collagen induced arthritis (CIA).32 In that study, APRIL/BLyS blockade via TACI-Ig blocked activation in vitro, and inhibited antigen-specific T lymphocyte activation and priming in vivo. TACI is present not only on B-lymphocytes, but also on activated T lymphocytes.

In summary, our data demonstrate that APRIL/BLyS blockade in sensitized animals was more effective at reducing DSA than BLyS blockade alone. This reduction likely resulted from improved depletion of mature B-lymphocyte populations and antibody secreting cells. Although APRIL/BLyS blockade has been shown in this study to significantly deplete mature B-lymphocyte populations, it has also been shown to increase transitional B-lymphocytes, which are thought to be tolerogenic.14,33–35 Thus APRIL/BLyS blockade may not only provide a more favorable milieu for improved transplant outcomes in desensitized patients, but in broader terms it may represent a clinically important mechanism for developing desensitization strategies in solid organ transplantation. Further study and careful consideration are required to determine the role of APRIL/BLyS blockade in transplantation as a desensitization therapy and its impact on post-transplant outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Flow cytometry panels and gating schemes. Flow cytometry was performed using a BD LSR II or BD LSR Fortessa, maintained by UWCCC flow cytometry center. Data analysis was done in FlowJo from Tree Star. Cells were gated for singlets and then lymphocytes based on forward and side scatter. Cells were visualized for CD21 versus IgM with gates drawn for transitional 2 marginal zone (T2 MZ) B-lymphocytes, mature B-lymphocytes, transitional 1 (T1) B-lymphocytes, left flow diagram in each set. After gating through a CD5−CD45R+ gate, CD21 versus CD23 with gates drawn for marginal zone (MZ) B-lymphocytes, follicular (Fo) B-lymphocytes and newly formed B-lymphocytes, right flow diagram in each set. There was a clearly discernible decrease in mature, Fo, and MZ B-lymphocytes in animals treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade and BLyS blockade (C, D) compared to nonsensitized or sensitized untreated groups (A, B). E) Naïve cells were gated for singlets and lymphocytes, then through an IgD+CD45R+ gate and visualized as IgD+CD27+ cells. F) Plasma cells were gated for singlets, then through a large gate that contained lymphocytes as well as larger cells, then through an IgD- CD45R- gate, IgM-CD27+ gate and finally visualized as IgM-CD138+.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Shannon Reese for helpful suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript. The authors would like to thank the UWCCC Flow Cytometry Shared instrumentation core, including the Shared Instrumentation grant 1S00OD018202–01 Special BD LSR Fortessa, which made possible the purchase and use of the BD LSR Fortessa and the UW Transplant Research Training Grant (T32 AI125231). BAFFR-Ig and TACI-Ig were kindly provided by EMD Serono Research and Development Institute under an MTA.

Funding

This work was supported by a KL2 career development award (4KL2TR000428–10), the American Society of Transplant Surgeons Faculty Development Grant (MSN183242), and the American College of Surgeons Franklin Martin, MD, FACS Faculty Research Fellowship (MSN192116). This publication was supported by the National Institute Of Allergy And Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32AI125231.

Abbreviations:

- AMR

antibody mediated rejection

- ASC

antibody secreting cell

- APRIL

a proliferation-inducing ligand

- BAFFR-Ig

B cell activating factor receptor-Immunoglobulin

- BLyS

B lymphocyte stimulator

- BM

bone marrow

- CsA

cyclosporine A

- CIA

collagen induced arthritis

- cPRA

calculated panel reactive antibody

- DSA

donor specific antibody

- HLA

Human Leukocyte Antigen

- IdeS

immunoglobulin G-degrading enzyme of Streptococcus pyogenes IdeS

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- IP

intraperitoneal

- IVIG

intravenous immunoglobulin

- LN

lymph node

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- MZ

marginal zone

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- RT

room temperature

- SFC

spot forming cells

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- Spl

splenocytes

- TACI-Ig

Transmembrane activator and calcium modulator and cyclophilin ligand interactor-Immunoglobulin

- T1

Transitional 1 B-lymphocyte

- T2 MZ

Transitional 2 marginal zone B-lymphocyte

Footnotes

Disclosures and conflicts of interest:

Robert Redfield: Murine TACI-Ig and BAFFR-Ig were generously provided by Merck Serono. Outside the submitted work, grants and personal fees were received from Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche.

All other authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Nancy A. Wilson, Department of Medicine, Division of Nephrology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Natalie M. Bath, Department of Surgery, Division of Transplant, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Bret M. Verhoven, Department of Surgery, Division of Transplant, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Xiang Ding, Division of Transplant Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI

Brittney A. Boldt, Department of Surgery, Division of Transplant, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Adarsh Sukhwal, University of Wisconsin-Platteville.

Weixiong Zhong, Department of Pathology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Sarah E. Panzer, Department of Medicine, Division of Nephrology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Robert R. Redfield, III, Department of Surgery, Division of Transplant, University of Wisconsin-Madison

References:

- 1.Jordan SC, Choi J, Vo A. Kidney transplantation in highly sensitized patients. Br Med Bull. 2015;114(1):113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordan SC, Vo AA. Donor-specific antibodies in allograft recipients: etiology, impact and therapeutic approaches. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2014;19(6):591–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scornik JC, Bromberg JS, Norman DJ, et al. An update on the impact of pre-transplant transfusions and allosensitization on time to renal transplant and on allograft survival. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montgomery RA, Lonze BE, King KE, et al. Desensitization in HLA-incompatible kidney recipients and survival. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(4):318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manook M, Koeser L, Ahmed Z, et al. Post-listing survival for highly sensitised patients on the UK kidney transplant waiting list: a matched cohort analysis. Lancet. 2017;389(10070):727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jordan SC, Lorant T, Choi J. IgG Endopeptidase in Highly Sensitized Patients Undergoing Transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(17):1693–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montgomery RA, Zachary AA, Racusen LC, et al. Plasmapheresis and intravenous immune globulin provides effective rescue therapy for refractory humoral rejection and allows kidneys to be successfully transplanted into cross-match-positive recipients. Transplantation. 2000;70(6):887–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vo AA, Lukovsky M, Toyoda M, et al. Rituximab and intravenous immune globulin for desensitization during renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(3):242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodle ES, Shields AR, Ejaz NS, et al. Prospective iterative trial of proteasome inhibitor-based desensitization. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(1):101–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abu Jawdeh BG, Cuffy MC, Alloway RR, et al. Desensitization in kidney transplantation: review and future perspectives. Clin Transplant. 2014;28(4):494–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsons RF, Vivek K, Rostami SY, et al. Acquisition of humoral transplantation tolerance upon de novo emergence of B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2011;186(1):614–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redfield RR 3rd, Rodriguez E, Parsons R, et al. Essential role for B cells in transplantation tolerance. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23(5):685–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gross JA, Dillon SR, Mudri S, et al. TACI-Ig neutralizes molecules critical for B cell development and autoimmune disease. impaired B cell maturation in mice lacking BLyS. Immunity. 2001;15(2):289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiemann B, Gommerman JL, Vora K, et al. An essential role for BAFF in the normal development of B cells through a BCMA-independent pathway. Science. 2001;293(5537):2111–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro-Shelef M, Calame K. Plasma cell differentiation and multiple myeloma. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16(2):226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dillon SR, Gross JA, Ansell SM, Novak AJ. An APRIL to remember: novel TNF ligands as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5(3):235–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mujtaba MA, Komocsar WJ, Nantz E, et al. Effect of Treatment With Tabalumab, a B Cell-Activating Factor Inhibitor, on Highly Sensitized Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease Awaiting Transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(4):1266–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banham GD, Flint SM, Torpey N, et al. Belimumab in kidney transplantation: an experimental medicine, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10140):2619–2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allman D, Pillai S. Peripheral B cell subsets. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20(2):149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang G, Wilson NA, Reese SR, et al. Characterization of transfusion-elicited acute antibody-mediated rejection in a rat model of kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(5):1061–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djamali A, Vidyasagar A, Adulla M, et al. Nox-2 is a modulator of fibrogenesis in kidney allografts. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(1):74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vidyasagar A, Reese S, Acun Z, et al. HSP27 is involved in the pathogenesis of kidney tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295(3):F707–F716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haas M, Sis B, Racusen LC, et al. Banff 2013 meeting report: inclusion of c4d-negative antibody-mediated rejection and antibody-associated arterial lesions. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(2):272–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panzer SE, Wilson NA, Verhoven BM, et al. Complete B Cell Deficiency Reduces Allograft Inflammation and Intragraft Macrophages a Rat Kidney Transplant Model. Transplantation. 2018;102(3):396–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackay F, Browning JL. BAFF: a fundamental survival factor for B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(7):465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benson MJ, Dillon SR, Castigli E, et al. Cutting edge: the dependence of plasma cells and independence of memory B cells on BAFF and APRIL. J Immunol. 2008;180(6):3655–3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Connor BP, Raman VS, Erickson LD, et al. BCMA is essential for the survival of long-lived bone marrow plasma cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199(1):91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwun J, Page E, Hong JJ, et al. Neutralizing BAFF/APRIL with atacicept prevents early DSA formation and AMR development in T cell depletion induced nonhuman primate AMR model. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(3):815–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Z, Davidson A. Taming lupus-a new understanding of pathogenesis is leading to clinical advances. Nat Med. 2012;18(6):871–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stohl W, Hiepe F, Latinis KM, et al. Belimumab reduces autoantibodies, normalizes low complement levels, and reduces select B cell populations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(7):2328–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haselmayer P, Vigolo M, Nys J, et al. A mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus responds better to soluble TACI than to soluble BAFFR, correlating with depletion of plasma cells. Eur J Immunol. 2017;47(6):1075–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Marsters SA, Baker T, et al. TACI-ligand interactions are required for T cell activation and collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(7):632–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newell KA, Asare A, Kirk AD, et al. Identification of a B cell signature associated with renal transplant tolerance in humans. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(6):1836–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newell KA, Asare A, Sanz I, et al. Longitudinal studies of a B cell-derived signature of tolerance in renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(11):2908–2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shabir S, Girdlestone J, Briggs D, et al. Transitional B lymphocytes are associated with protection from kidney allograft rejection: a prospective study. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(5):1384–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Flow cytometry panels and gating schemes. Flow cytometry was performed using a BD LSR II or BD LSR Fortessa, maintained by UWCCC flow cytometry center. Data analysis was done in FlowJo from Tree Star. Cells were gated for singlets and then lymphocytes based on forward and side scatter. Cells were visualized for CD21 versus IgM with gates drawn for transitional 2 marginal zone (T2 MZ) B-lymphocytes, mature B-lymphocytes, transitional 1 (T1) B-lymphocytes, left flow diagram in each set. After gating through a CD5−CD45R+ gate, CD21 versus CD23 with gates drawn for marginal zone (MZ) B-lymphocytes, follicular (Fo) B-lymphocytes and newly formed B-lymphocytes, right flow diagram in each set. There was a clearly discernible decrease in mature, Fo, and MZ B-lymphocytes in animals treated with APRIL/BLyS blockade and BLyS blockade (C, D) compared to nonsensitized or sensitized untreated groups (A, B). E) Naïve cells were gated for singlets and lymphocytes, then through an IgD+CD45R+ gate and visualized as IgD+CD27+ cells. F) Plasma cells were gated for singlets, then through a large gate that contained lymphocytes as well as larger cells, then through an IgD- CD45R- gate, IgM-CD27+ gate and finally visualized as IgM-CD138+.