Abstract

Background:

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) clinical guidelines for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) are widely utilized to assess patients’ PrEP eligibility. The guidelines include two versions of criteria – guidance summary criteria and recommended indications criteria – that diverge in a potentially critical way for heterosexually active women: Both require women’s knowledge of their own risk behavior, but the recommended indications also require women’s knowledge of their partners’ HIV risk or recognition of a potentially asymptomatic sexually transmitted infection (STI). This study examined women’s PrEP eligibility according to these two different versions of criteria across risk and motivation categories.

Setting/Methods:

HIV-negative women (n=679) recently engaged in care at Connecticut Planned Parenthood centers were surveyed online in 2017. The survey assessed PrEP eligibility by both versions of CDC criteria, HIV risk indicators, PrEP motivation indicators, and sociodemographic characteristics.

Results:

Participants were mostly non-Hispanic White (33.9%) or Black (35.8%) and low-income (<$30,000/year; 58.3%). Overall, 82.3% were eligible for PrEP by guidance summary criteria vs. 1.5% by recommended indications criteria. Women disqualified by recommended indications criteria included those reporting condomless sex with HIV-positive or serostatus-unknown male partners (n=27, 11.1% eligible); one or more recent STI(s) (n=53, 3.8% eligible); multiple sex partners (n=168, 3.0% eligible); intended PrEP use (n=211, 2.8% eligible); and high self-perceived risk (n=5, 0.0% eligible).

Conclusion:

Current guidelines disqualify many women who could benefit from PrEP and may lead to discrepant assessments of eligibility. Guideline reform is needed to improve clarity and increase women’s PrEP access and consequent HIV protection.

Keywords: HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis, eligibility determination, clinical decision-making, patient care, women

INTRODUCTION

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a highly effective method of HIV prevention.1,2 In the US, PrEP uptake has risen dramatically among men since its 2012 federal approval, but remains low among women: Women account for less than five percent of PrEP users3 despite representing 19% of new HIV diagnoses.4 Further efforts are needed to promote PrEP uptake among women, including implementation of clinical practice standards that improve women’s PrEP access.

2018 marked the release of an updated (“2017”) version of the US Clinical Practice Guideline for PrEP by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).5 This comprehensive informational resource, commonly referred to as “the CDC guidelines,” updates an earlier (2014) version of the guidelines,6 which consolidated and elaborated early interim CDC guidance published between 2011 and 2013 for different key populations.7–9 The CDC guidelines are intended to support clinicians and policymakers in making PrEP available to people at substantial risk for HIV. Indeed, clinicians have reported such guidelines to be a key influence on PrEP comfort and decision-making in practice10,11 and the CDC guidelines form the foundation of clinical recommendations adopted at state and organization levels.e.g.,12,13

The guidelines contain PrEP eligibility criteria to help identify patients at substantial HIV risk, defined separately for MSM, heterosexual women and men, and people who inject drugs, but state two different versions – guidance summary criteria and recommended indications criteria. Though overlapping, there are several inconsistencies between guidance summary criteria and recommended indications criteria within each risk group; for women at risk due to heterosexual activity, the two versions of criteria diverge in a potentially critical way: While both require women’s knowledge of their own risk behavior, only the recommended indications criteria also require women to either know their partners’ HIV risk or recognize a potentially asymptomatic sexually transmitted infection (STI).14,15 Specifically, the first and less restrictive version of criteria, the guidance summary criteria,5(p. 13) stipulates that women should be HIV-uninfected and lists the following indicators of substantial HIV risk: HIV-positive sexual partner, recent bacterial STI (syphilis or gonorrhea), high number of sex partners, history of inconsistent or no condom use, commercial sex work, and high-prevalence area or network. Thus, to meet the guidance summary criteria, women need only know about their own risk behavior. The second version of criteria, the recommended indications criteria,5(p. 36) specifies that women should be HIV-uninfected, heterosexually active adults who are not in a monogamous relationship with a recently tested, HIV-negative partner and should be characterized by one or more of the following: (a) in an ongoing serodiscordant sexual relationship, (b) infrequently uses condoms during sex with one or more male partners of unknown HIV status who are known to be at substantial risk (e.g., because of injection practices or sex with other men), and (c) had syphilis or gonorrhea within the past six months. Thus, for women at sexual risk to meet criteria according to the recommended indications criteria, women need to know that (a) a partner’s HIV status is positive, (b) a partner is engaging in risk behavior, or (c) they themselves have a potentially asymptomatic STI.

Although a key objective of the CDC guidelines is to identify women at substantial risk for HIV as potential PrEP candidates, the effectiveness of both the guidance summary criteria and the recommended indications criteria in achieving that objective has not been explicitly investigated. Understanding whether these two versions of eligibility criteria distinguish women who are at risk and motivated to use PrEP is critical, as many providers use them as screening criteria when deciding whether to discuss and prescribe PrEP during patient encounters.

The present research was undertaken to evaluate both versions of CDC guideline criteria (guidance summary criteria and recommended indications criteria) among a large sample of HIV-negative women recently engaged in care at Connecticut Planned Parenthood centers. We pursued three main objectives: First, we sought to describe the eligibility of sociodemographic groups differentially affected by HIV (e.g., non-Hispanic Black vs. White women4,16) according to guidance summary and recommended indications criteria and to assess whether the relative eligibility of these groups aligned with the epidemiological risk profile of HIV. Second, we sought to determine whether women with existing HIV risk factors and motivation to use PrEP would be deemed eligible according to guidance summary and recommended indications criteria, and how the 2017 update to the 2014 guidelines affected such eligibility. A third, exploratory objective was to investigate the pervasiveness of CDC guideline criteria within state-level PrEP eligibility recommendations and whether different states used different versions of the CDC criteria (guidance summary vs. recommended indications criteria).

METHODS

Methods described below have also been reported elsewhere.17,18

Procedures

In February of 2017, an email inviting Connecticut Planned Parenthood patients to participate in an anonymous online survey was distributed to 11,238 patients. The survey was restricted to patients who had agreed to receiving email communication from Planned Parenthood (77%), were 18 and older, and recently engaged in care at Planned Parenthood centers in three small cities with the highest annual number of HIV infections in Connecticut: Bridgeport, Hartford, and New Haven.19 Recent care engagement, determined via patients’ medical records, was defined as attending one or more visits in the past ten months. Interested patients followed a survey link embedded in the recruitment email, completed an online consent form, responded to survey questions (median time=36 minutes), and received compensation ($10 gift card). The survey closed to new participants once 973 had enrolled and initiated the survey – which occurred within 100 hours of deploying the recruitment email – to avoid exceeding the recruitment maximum of 1,000. All procedures were approved by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee.

Measures

All measures were self-administered via the online survey. Additional details about measures of PrEP eligibility, HIV risk, and PrEP motivation beyond the descriptions below are available as supplemental digital content (See Text Summary, Supplemental Digital Content 1).

PrEP eligibility

was conceptualized as a dichotomous variable, coded as (1) eligible vs. (0) ineligible, and determined separately for each version of CDC guideline criteria (guidance summary criteria and recommended indications criteria). Operationalization of each individual criterion (wording of associated survey item[s]) and the number/combination of criteria needed to qualify as eligible by each version are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

| Version 1 of Criteria for Women: Guidance Summary Criteria (p. 13) | ||

|---|---|---|

| At Risk Due to Heterosexual Activity | ||

| Criterion | Measure(s) | Response(s) Indicating Criterion Met |

| 1+ of the following: | ||

| •HIV-positive sexual partner | Are you in an ongoing sexual relationship with an HIV--positive partner?d | Yes |

| Has a healthcare provider EVER in your life told you that you have… Syphilis | Yes | |

| •High number of sex partners | Over the past 6 months, with about how many DIFFERENT MEN did you have vaginal or anal sex? Please enter a number in the space below.e | 3+ |

| Over the past 6 months, how consistently did you use condoms when having anal sex with a man? | Mostly (75% of the time) Sometimes (50% of the time) Rarely (25% of the time) Never (0% of the time) | |

| •Commercial sex work | Have you ever had sex in exchange for money, drugs, or other goods? | Yes |

| •In high-prevalence area or network | N/A (assumed participants were NOT in high-prevalence area or network) | - |

| At Risk Due to Injection Drug-Related Activity | ||

| 1+ of the following: | ||

| •HIV-positive injecting partner | Over the past 6 months, have you injected drugs by using needles, syringes, or other drug preparation equipment that had already been used by another person who you know is HIV-POSITIVE? | Yes |

| •Sharing injection equipment | Over the past 6 months, have you injected drugs by using needles, syringes, or other drug preparation equipment that had already been used by another person? | Yes |

| Version 2 of Criteria for Women: Recommended Indications Criteria (p. 36) | ||

| At Risk Due to Heterosexual Activity | ||

| Criterion | Measure(s) | Response(s) Indicating Criterion Met |

| Adult person | N/A (sample restricted to participants 18 and older) | - |

| Without acute or established HIV infection | N/A (sample restricted to self-reported HIV-negative participants; clinical measures unavailable) | - |

| Any sex with opposite sex partners in past 6 months | Over the past 6 months, have you had any vaginal or anal sex with a man? In other words, over the past 6 months, has a man inserted his penis into your vagina or anus? | Yes |

| Not in a monogamous partnership with a recently tested HIV-negative partner | Are you currently in a monogamous sexual relationship with a partner who has recently tested HIV-negative? “Monogamous” means that you only have sex with each other and no one else.” | No I don’t know |

| AND 1 +of the following: | ||

| •Is a man who has sex with both women and men (behaviorally bisexual) | N/A (sample restricted to women) | - |

| How often do you use condoms with your sexual partner(s) who you believe to be at substantial risk of getting HIV? | Sometimes Never |

|

| •Is in an ongoing sexual relationship with an HIV-positive partner | Are you in an ongoing sexual relationship with an HIV--positive partner? | Yes |

| Has a healthcare provider EVER in your life told you that you have… Syphilis | Yes | |

| At Risk Due to injection Drug-Related Activity | ||

| Adult person | N/A (sample restricted to participants 18 and older) | - |

| Without acute or established HIV infection | N/A (sample restricted to self-reported HIV-negative participants; clinial measures unavailable) | - |

| Any injection of drugs not prescribed by a clinician in the past 6 months | Over the past 6 months, have you injected drugs? | Yes |

| AND 1+ of the following: | ||

| •Any sharing of injection drug or preparation equipment in past 6 months | Over the past 6 months, have you injected drugs by using needles, syringes, or other drug preparation equipment that had already been used by another person? | Yes |

| •Risk of sexual acquisition | N/A (evaluate by above criteria for women at risk due to heterosexual activity) | - |

US Clinical Practice Guideline - 2Q17 Update

Original (2014) US Clinical Practice Guideline guidance summary criteria were similar except that (a) gonorrhea and syphilis were not specifically named in a footnote to “recent bacterial STI” and (b) “recent drug treatment (but curently injecting)” was an additional criterion (in list of 1 + criteria) for people at risk due to injection drug-related activity

Includes HIV risk criteria only; does not include clinical eligibility criteria (documented HIV negative test result, no signs/symptoms of acute HIV infection, normal renal function, no contraindicated medications, documented hepatitis B virus infection/vaccination status)

Participants who reported being in a monogamous sexual relationship with a recently-tested HIV-negative partner were not directly asked this question. Instead, they were automatically assigned the value “No.”

87.9% of the sample had less than 3 partners; Median = 1 partner

Sociodemographic characteristics

included gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, education, employment, household income, age, and geographic location.

HIV risk indicators

spanned three categories:

Sexual health risk indicators included STIs (diagnosed in lifetime and perceived in past six months), PrEP use (lifetime and current), post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) use (lifetime), emergency contraception use (lifetime), and pregnancy (lifetime unwanted and current).

Behavioral risk indicators included vaginal or anal sex with multiple (two or more) male partners (past six months); condomless vaginal or anal sex with a male partner (past six months); condomless vaginal or anal sex with an HIV-positive or status-unknown male partner (past six months); anticipated increase in number of sexual partners (future six months); anticipated decrease in condom use (future six months); sex in exchange for money, drugs, or other goods (lifetime); and injection drug use (past six months).

Relationship risk indicators included experiencing intimate partner violence (current relationship of one or more years); experiencing reproductive coercion (lifetime); involvement in an ongoing sexual relationship with a potentially viremic HIV-positive male partner; and involvement in an ongoing relationship with a male partner of unknown HIV status (current relationship of one or more months).

PrEP motivation indicators

included self-perceived HIV risk (self-rated “very” or “extremely” likely to get HIV in lifetime), PrEP interest (“very” or “extremely” interested in learning more about PrEP), and PrEP intention (“probably” or “definitely” would take PrEP if available for free).20

Analysis

The analytic sample was restricted to participants who identified as women (“woman” or “transgender woman”), reported no prior HIV diagnosis, and responded to all PrEP eligibility questions for both sets of criteria (guidance summary criteria and recommended indications criteria). For a given set of criteria, women who met the subset of criteria pertaining to heterosexual activity, injection drug-related activity, or both were deemed eligible by those criteria. (See eTables 1–2, Supplemental Digital Content 2 for supplementary analyses of eligibility by criteria pertaining to heterosexual activity only and injection drug-related activity only). Frequency distributions were calculated to describe sample characteristics. Logistic regressions were conducted to compare the probability of being eligible within sociodemographic categories. State-level eligibility criteria were compiled by searching state health department websites for PrEP-specific content. Specifically, two co-authors (RWG and MT) independently searched for PrEP criteria and other PrEP-related information on health department websites for all states and Washington, DC, reconvening to compare their lists of online sources (URLs recorded for each state) and create a master list of sources. An initial coding scheme developed by the principal investigator (SKC) was iteratively refined through multiple rounds of coding and discussion. Based on the final coding scheme, RWG and MT systematically recorded PrEP eligibility criteria specified on state health department websites and coded PrEP-related links provided on these websites. SKC reviewed and finalized all recorded criteria and assigned codes.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic and Behavioral Characteristics

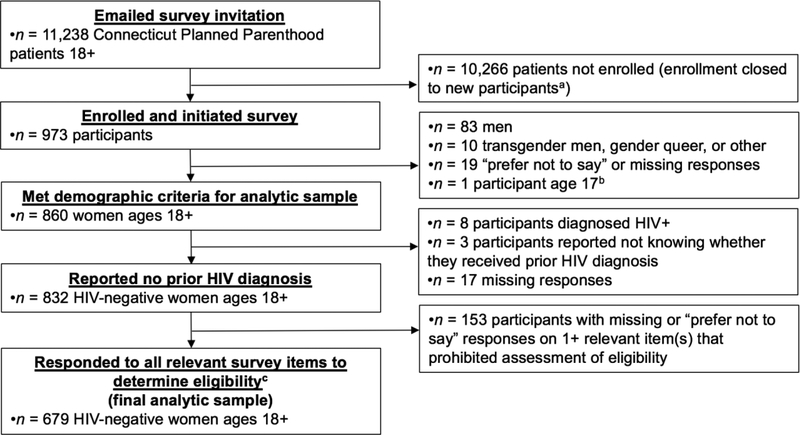

Of the 973 Connecticut Planned Parenthood patients enrolled in the survey, 679 met criteria for inclusion in the analytic sample (see Figure 1). No participants identified as transgender women. Most participants identified as non-Hispanic White (33.9%) or Black (35.8%). The mean age was 28.2 (SD=7.5). As compared to HIV-negative female participants who were excluded from analyses because they did not answer all required items (n=153), a larger percentage of participants included in analyses were White (33.9% of included vs. 24.2% of excluded; X2[1]=5.38, p=.020). There was no significant difference in age distribution (57.0% of included vs. 51.6% of excluded were over age 25; X2[1]=1.46, p=.227). As compared to the larger population of HIV-negative female patients 18 and older who were recently engaged in care at the three Planned Parenthood centers from which the sample was drawn (n = 12,426), a larger percentage of our sample was White (33.9% of study sample vs. 28.9% of patient population; X2[1]=7.71, p=.005) and over age 25 (57.0% of study sample vs. 52.0% of patient population; X2[1]=6.47, p=.011). Additional sociodemographic characteristics are displayed in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Summary of Participant Enrollment and Inclusion within Analytic Sample.

aOur enrollment maximum was established as 1,000 participants. To avoid exceeding this maximum, we closed the survey to new participants when 973 had enrolled because additional patients had clicked on the survey link but not yet consented and we were uncertain whether they would continue on to enroll.

bParticipant self-reported being 18 or older on screening item and subsequently reported being 17 in demographic survey question

cEligiblity assessable by all 4 sets Df CDC guideline criteria: (a) 2017 recommended indications criteria, (b) 2017 guidance summary criteria, (c) 2014 recommended indications criteria, and (d) guidance summary criteria

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Differences in PrEP Eligibility Among Women

| Total | Eligible Based On Recommended Indications Criteriaa | Eligible Based On Guidance Summary Criteriab | Eligible vs. Ineligible Based On Guidance Summary Criteriaa (Comparison Within Sociodemographic Categories) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Subgroup | n (%)b | n (%)c | n (%)c | OR [95% Cl] | p | AOR [95% CI]d | p |

| All womene | 679 (100.0) | 10 (1.5) | 559 (82.3) | - | - | - | - |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic White women [REF] | 230 (33.9) | 5 (2.2) | 190 (82.6) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Non-Hispanic Black women | 243 (35.8) | 5 (2.1) | 197 (81.1) | .90 [.56, 1.44] | .67 | .78 [.45, 1.33] | .35 |

| Hispanic/Latina women | 162 (23.9) | 0 (0.0) | 135 (83.3) | 1.05 [.62, 1.80] | .85 | .98 [.54, 1.79] | .95 |

| Non-Hispanic American Indian, Asian, Native Hawaiian, and other | 44 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 37 (84.1) | 1.11 [.46, 2.67] | .81 | 1.22 [.47, 3.18] | .69 |

| Sexual Orientationf | |||||||

| Heterosexual/Straight [REF] | 518 (79.1) | 8 (1.5) | 433 (83.6) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Bisexual | 98 (15.0) | 0 (0.0) | 80 (81.6) | .87 [.50, 1.53] | .63 | .83 [.46, 1.49] | .53 |

| Lesbian/Gay | 13 (2.0) | 1 (7.7) | 8 (61.5) | .31 [.10, .98] | .05 | .30 [.09, .97] | .04 |

| Other | 26 (4.0) | 1 (3.8) | 19 (73.1) | .53 [.22, 1.31] | .17 | .50 [.20, 1.27] | .15 |

| Education | |||||||

| Less than bachelor’s degree [REF] | 492 (72.5) | 8 (1.6) | 408 (82.9) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 187 (27.5) | 2 (1.1) | 151 (80.7) | .86 [.56, 1.33] | .51 | .74 [.45, 1.22] | .23 |

| Employment | |||||||

| Employed full-time or part-time [REF] | 458 (67.5) | 4 (0.9) | 382 (83.4) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Unemployed | 83 (12.2) | 3 (3.6) | 61 (73.5) | .55 [.32, .95] | .03 | .42 [.22, .80] | .01 |

| Other (e.g., student, homemaker, retired) | 138 (20.3) | 3 (2.2) | 116 (84.1) | 1.05 [.63, 1.76] | .86 | .86 [.49, 1.52] | .61 |

| Household Income | |||||||

| $10,000 or less per year [REF] | 170 (25.0) | 4 (2.4) | 137 (80.6) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| $11,000 - $30,000 per year | 226 (33.3) | 2 (0.9) | 190 (84.1) | 1.27 [.76, 2.14] | .37 | .90 [.50, 1.64] | .74 |

| $31,000 - $50,000 per year | 151 (22.2) | 3 (2.0) | 120 (79.5) | .93 [.54, 1.61] | .80 | .61 [.32, 1.17] | .13 |

| $51,000 - $70,000 per year | 67 (9.9) | 0 (0.0) | 58 (86.6) | 1.55 [.70, 3.45] | .28 | 1.05 [42, 2.58] | .92 |

| Over $70,000 per year | 65 (9.6) | 1 (1.5) | 54 (83.1) | 1.18 [.56, 2.51] | .66 | .81 [.34, 1.96] | .64 |

| Age | |||||||

| 18–25 years [REF] | 292 (43.0) | 1 (0.3) | 240 (82.2) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| 26 or older | 387 (57.0) | 9 (2.3) | 319 (82.4) | 1.02 [1.68. 1.51] | .94 | 1.06 [.68. 1.65] | .80 |

| Geographic Locationg | |||||||

| Bridgeport [REF] | 263 (38.9) | 1 (0.4) | 219 (83.3) | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Hartford | 118 (17.5) | 3 (2.5) | 93 (78.8) | .75 [.43, 1.29] | .30 | .78 [43, 1.40] | .40 |

| New Haven | 236 (34.9) | 6 (2.5) | 196 (83.1) | .98 [.62, 1.57] | .95 | .98 [.60, 1.61] | .93 |

| Other | 59 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 49 (83.1) | .98 1.46. 2.091 | .97 | 1.0 [.45, 2.191 | 1.00 |

2017 CDC guideline criteria for risk due to heterosexual activity, criteria for risk due to injection drug-related activity, or both

Column percentages

Row percentages

Models adjusted for all other sociodemographic characteristics (race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, education, employment, household income, age, and/or geographic location)

Participants who self-identified as a “woman” or “transgender woman” were eligible; no participants self-identified as a “transgender woman”

n = 655 for this subgroup because 24 participants selected “prefer not to say”

Represents location of Planned Parenthood center visited most recently; n = 676 due to missing responses

Over the preceding six months, the vast majority of participants (89.1%) reported vaginal or anal sex with one or more men, of which 90.2% reported inconsistent or no condom use. When heterosexually active participants were asked whether they had condomless vaginal or anal sex with an HIV positive or status-unknown male partner in particular, 91.9% reported they had not, 4.5% reported they had, and 3.6% reported they did not know. Few participants (0.7%) reported injecting drugs.

PrEP Eligibility

There were substantial differences in the prevalence of women eligible for PrEP based on guidance summary vs. recommended indications criteria: 559 (82.3%) of the 679 women were eligible based on guidance summary criteria and 10 women (1.5%) were eligible based on recommended indications criteria. A similar pattern of difference in percent eligibility between guidance summary and recommended indications criteria was evident within all sociodemographic categories (see Table 2). Logistic regression analyses predicting eligibility according to guidance summary criteria found two significant sociodemographic predictors: sexual orientation and employment. Gay/lesbian women were less likely to qualify for PrEP than heterosexual women and unemployed women were less likely to qualify than employed women. Logistic regression analyses predicting eligibility according to recommended indications criteria were not performed because of the low number of participants deemed eligible (less than ten observations in all subgroups).

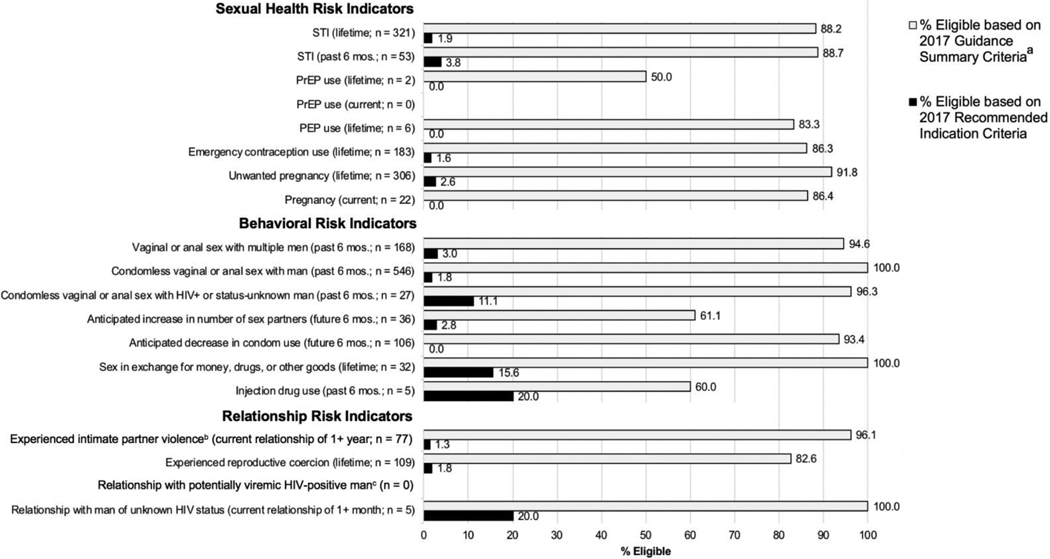

HIV Risk Indicators and PrEP Eligibility

Figure 2 shows PrEP eligibility by risk indicator. Within all risk indicator groups, more women were eligible for PrEP based on guidance summary vs. recommended indications criteria, with the latter disqualifying the majority of women. Similar patterns were evident when heterosexual risk criteria and injection drug-related risk criteria were examined separately (See eTables 1–2, Supplemental Digital Content 2). Comparison of eligibility based on 2014 vs. 2017 criteria revealed that the guideline update had little impact on women’s eligibility (See eTable 3, Supplemental Digital Content 2).

Figure 2.

PrEP Eligibility According to 2017 CDC Criteria Among Subgroups of Women in Reporting Various Risk Indicators.

aEligibility assessment assumed all participants were NOT in a high-prevalence area or network. If all participants were assumed to be in a high-prevalence area or network, 100% would be eligible based on guidance summary criteria for all risk indicators.

bA total of 349 participants responded to survey items corresponding to the "experienced intimate partner violence" risk indicator because only participants who reported having sex with men (or both men and women) and having a current sexual/romantic relationship for 1+ year (n = 357) were gated to those items (and 8 responses were missing). For ail risk indicators besides the "experienced intimate partner violence" risk indicator, the total number of participants who responded to corresponding survey items ranged from 651-679 due to survey gating/display logic, missing responses, and exclusion of "prefer not to say" responses. (See Appendix 1 for description of gating/display logic and Appendix 2: eTable 1 for total n per risk indicator).

cPotentially viremic = not virally suppressed or viral suppression status unknown to participant

PrEP Motivation Indicators and PrEP Eligibility

Five women perceived themselves as being at high risk for HIV, of which four were eligible based on guidance summary criteria and zero were eligible based on recommended indications criteria. Of the 108 women who were “very” or “extremely” interested in learning more about PrEP, more were eligible based on guidance summary criteria (79.6%) vs. recommended indications criteria (4.6%). Likewise, of the 211 women who reported they “probably” or “definitely” would take PrEP, more were eligible based on guidance summary (82.5%) vs. recommended indications criteria (2.8%) (See eTable 4, Supplemental Digital Content 2).

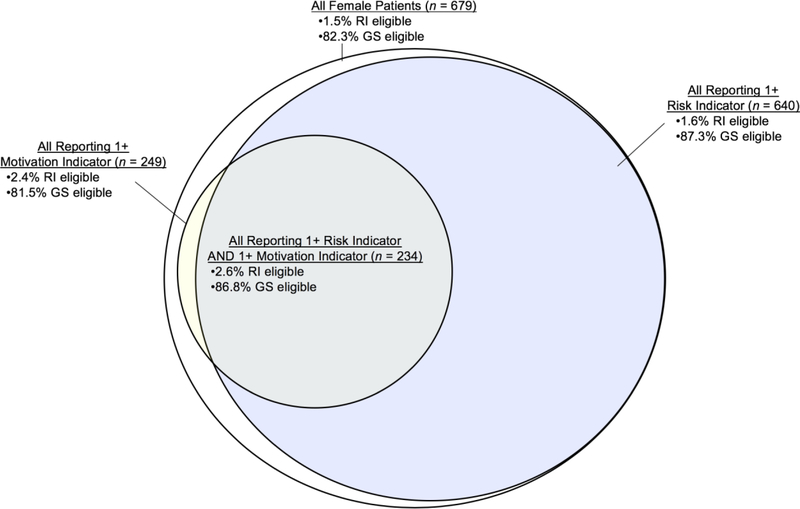

Risk and Motivation Indicators Combined and PrEP Eligibility

Figure 3 displays PrEP eligibility according to both sets of criteria for the full sample, women with one or more risk indicators, women with one or more motivation indicators, and women with both risk and motivation indicators. Among the 234 women reporting both, 86.8% were eligible by guidance summary criteria and 2.6% by recommended indications criteria.

Figure 3.

Schematic Representation of PrEP Eligibility According to 2017 CDC Criteria Among Women At Risk for HIV, Motivated to Use PrEP, or Both. RI eligible = % eligible according to CDC recommended indications criteria. GS eligible = % eligible according to CDC guidance summary criteria.

Pervasiveness of CDC Guideline Criteria

Many state websites specified eligibility criteria that were the same or similar to CDC guideline criteria and/or linked directly or indirectly to CDC guideline criteria online (42 of 50 states and DC; See eTable 5, Supplemental Digital Content 3). There was variability in the version of CDC guideline criteria adopted; some states specified criteria more similar to guidance summary criteria and others specified criteria more similar to recommended indications criteria. Three states neither specified PrEP criteria for women on their website nor linked to CDC or other web pages related to PrEP.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that many women who report known HIV risk factors, motivation to take PrEP, or both would not be considered eligible for PrEP according to the criteria set forth in the CDC guidelines. This was found for both versions of criteria in the guidelines – guidance summary criteria and recommended indications criteria – but was especially true for the latter, according to which the vast majority (98.5%) of women were disqualified. The insensitivity of the criteria to women who could benefit from PrEP is disconcerting in the context of 7,300 new HIV infections occurring among US women annually4 as well as disproportionately low levels of reported PrEP awareness21,22 and uptake.3 It is further concerning given the potential reach of these criteria: Our review of state guidelines found that most states either specify eligibility criteria similar to CDC criteria, link to CDC criteria, or both.

Our first study objective was to describe the eligibility of sociodemographic groups differentially affected by HIV and to assess whether the relative eligibility of these groups aligned with the epidemiological risk profile of HIV. Analyses based on guidance summary criteria revealed few significant sociodemographic differences in eligibility. Within sociodemographic categories, women appeared similarly likely to qualify for PrEP, except for women who were unemployed (vs. employed) and gay or lesbian (vs. heterosexual) being less so. Therefore, overall, the relative eligibility of sociodemographic groups did not align with the epidemiological risk profile of HIV. Fortunately, it also did not oppose that profile; recent studies with men who have sex with men have reported that Black men, who are disproportionately burdened by HIV, were less likely to meet CDC eligibility criteria than White men.23,24 Rather, to the extent that eligibility determines access, our data suggest that CDC criteria would be unlikely to reduce HIV disparities among women but also unlikely to substantively exacerbate them.

Our second objective was to determine whether women with existing HIV risk factors and motivation to use PrEP would be deemed eligible according to both versions of criteria, and how the 2017 update to the 2014 guidelines affected such eligibility. As noted above, the two versions of criteria both disqualified some women reporting risk and motivation indicators, but the recommended indications criteria in particular disqualified nearly all. The 2017 update had minimal impact. These findings underscore the need for guideline reform. Modifying one version of criteria to match the other or eliminating one version of criteria altogether would strengthen the clarity of the guidelines and reduce discrepancies in assessments of eligibility.14 However, even the guidance summary criteria disqualified some women who could benefit from PrEP, and eliminating or modifying recommended indications criteria would not resolve this issue. Therefore, we recommend that the guidelines also explicitly state the limitations of using eligibility criteria for screening purposes and recommend discussing PrEP with all patients as part of routine sexual healthcare in order to guard against missed opportunities.14,25

Among the limitations of current CDC criteria are their emphasis on past behavior.26 The risk indicators we considered reflected not only past risk behavior but also future behavior. Many women in our sample reported they anticipated decreasing their condom use, increasing their number of sexual partners, or both in the next six months, and some of these women were disqualified by both sets of criteria. These anticipated behavioral changes highlight the potential fluidity of sexual behavior and the inherent shortcoming of criteria that rely on past behavior to predict future risk. Likewise, our findings with respect to past risk behavior should be interpreted within this context, recognizing that not all women reporting past risk factors will be at future risk.

Risk prediction is indeed a complicated and imperfect process—for providers and for patients. Less than one percent of participants reported perceiving themselves to be at significant risk for HIV even though many more reported objective indicators of risk (e.g., over ten times as many reported a recent STI). Previous research has documented a mismatch between perceived risk and risk behavior, with women routinely underestimating their risk.27 Notably, despite the low risk perception reported, 31% of participants reported they “probably” or “definitely” would take PrEP if it was freely available, suggesting underestimation of risk is not an insurmountable barrier to PrEP uptake. For some women with high intention to take PrEP despite low perceived risk, this could reflect a different motivation for taking PrEP (e.g., anxiety reduction). Accordingly, the CDC guidelines could encourage patient-provider discussions of the holistic impact that PrEP has on wellbeing, including psychosocial benefits.

Our final objective was to examine the pervasiveness of CDC guideline criteria within state-level eligibility criteria presented online. Nearly all states (84%) and DC appear to have duplicated, adapted, or linked to the CDC guideline criteria, underscoring the relevance and reach of the CDC guidelines as a clinical standard and potential determinant of access. Some state criteria more closely aligned with the guidance summary criteria and others with the recommended indications criteria. Variability in state-level eligibility criteria could contribute to state-level disparities in providers’ perceptions of the “appropriate” PrEP candidate and associated rates of PrEP prescription. Thus, guideline reform is needed at both national and state levels, and active efforts will be necessary to translate CDC guideline revisions into state-level guideline updates.

This study has limitations that are important to acknowledge and invite follow-up study. Participants were recruited from Connecticut Planned Parenthood centers and may not represent women in other geographic areas or with different levels of healthcare engagement. Risk factors were self-reported and the study was cross-sectional; use of biological risk markers28 or a longitudinal design monitoring actual seroconversion29 would strengthen inferences regarding the sensitivity of eligibility criteria to women’s HIV risk. Additionally, social desirability bias may have led to underreporting of risk indicators and overreporting of motivation indicators, particularly because the survey was distributed by participants’ source of healthcare.

Concluding Remarks

Release of the CDC guidelines coincided with a marked increase in PrEP uptake in the US30 and has supported adoption of PrEP in clinical practices across the country. However, the current findings suggest that the eligibility criteria they present fail to identify many women who could benefit from PrEP; this failure may contribute to low and inequitable levels of PrEP awareness and uptake among women,3,21,22 an effect amplified by the widespread adoption and endorsement of these criteria at the state level. The US Preventive Services Task Force, a national panel of experts, recently released drafted recommendations for PrEP that parallel the CDC recommended indications criteria for women at risk due to heterosexual activity;31 if left unrevised, these recommendations would further reinforce the more restrictive of the CDC criteria, according to which only 1.5% of our sample was eligible.

Nationwide, the CDC originally estimated that 468,000 US women were strong candidates for PrEP due to heterosexual activity based on the 2014 recommended indications criteria.32 In 2018, they revised that number to 177,000 women based on an alternative estimation approach.33 Our results imply that both of these estimates drastically misrepresent the number of women who could actually benefit from PrEP. Such underestimation may skew providers’ perceptions about women’s need for PrEP and, in so doing, reduce the frequency with which PrEP is offered to women within the healthcare system. It may also lead to broader de-prioritization of PrEP for women, discouraging allocation of funding and other resources to initiatives aimed at enhancing women’s access. Ongoing evaluation and improvement of CDC eligibility criteria is crucial to ensuring that women’s HIV prevention needs are not overlooked in clinical practices and public health policies.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Detailed description of Measures and Coding

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Supplementary Eligibility Analyses (eTables 1–4)

Supplemental Digital Content 3. Summary of State-Level PrEP Eligibility Criteria for Women (eTable 5)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the Connecticut Planned Parenthood patients who generously contributed their time and effort by participating in this study. We are grateful to Ms. Susan Lane for her help with data collection and other facets of the study. We appreciate the funding and resources provided by the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (CIRA) Pilot Projects in HIV Program at Yale University. CIRA is funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) via Award Number P30-MH062294. Effort was supported by the NIMH via Award Numbers K01-MH103080 (SKC), F31-MH113508 (TCW), and T32-MH02003 (TT). Additional support for TCW was provided by the NIMH via the Brown Initiative in HIV and AIDS Clinical Research for Minority Communities (R25-MH083620). Additional support for TT was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) via the HIV/AIDS, Substance Abuse, and Trauma Training Program at the University of California, Los Angeles (R25-DA035692). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH, NIDA, National Institutes of Health (NIH), or Planned Parenthood Federation of America, Inc.

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding: SKC has received compensation for developing and delivering medical education related to PrEP. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding was provided by the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (CIRA) Pilot Projects in HIV Program at Yale University. CIRA is funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) via Award Number P30-MH062294. Effort was supported by the NIMH via Award Numbers K01-MH103080 (SKC), F31-MH113508 (TCW), and T32-MH02003 (TT). Additional support for TCW was provided by the NIMH via the Brown Initiative in HIV and AIDS Clinical Research for Minority Communities (R25-MH083620). Additional support for TT was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) via the HIV/AIDS, Substance Abuse, and Trauma Training Program at the University of California, Los Angeles (R25-DA035692). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH, NIDA, or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Some results presented in this manuscript were previously presented at the 13th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence in Miami (June, 2018)

REFERENCES

- 1.Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, Kennedy CE, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for all populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2016;30(12):1973–1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riddell JT, Amico KR, Mayer KH. HIV Preexposure prophylaxis: A review. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1261–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Giler RM, et al. The prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis use and the pre-exposure prophylaxis-to-need ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):841–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report: Diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2017-vol-29.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2019.

- 5.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States - 2017 update: A clinical practice guideline. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2018.

- 6.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Public Health Service. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States - 2014: A clinical practice guideline. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/guidelines/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidance: Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(3):65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidance for clinicians considering the use of preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in heterosexually active adults. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(31):586–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update to interim guidance for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for the prevention of HIV infection: PrEP for injecting drug users. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(23):463–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krakower D, Ware N, Mitty JA, Maloney K, Mayer KH. HIV providers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in care settings: A qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1712–1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith DK, Mendoza MC, Stryker JE, Rose CE. PrEP awareness and attitudes in a national survey of primary care clinicians in the United States, 2009–2015. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Georgia Department of Public Health. Expanding prevention through community mobilization: Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) toolkit. https://dph.georgia.gov/sites/dph.georgia.gov/files/PrEP%20Toolkit%202017.pdf. Accessed August 19, 2018.

- 13.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion: Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):1133–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calabrese SK, Krakower DS, Willie TC, Kershaw TS, Mayer KH. US guideline criteria for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: Clinical considerations and caveats. Clin Infect Dis. 2019. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raifman J, Sherman SG. US guidelines that empower women to prevent HIV with preexposure porphylaxis. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;45(6):e38–e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hess KL, Hu X, Lansky A, Mermin J, Hall HI. Lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(4):238–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calabrese SK, Dovidio JF, Tekeste M, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis stigma as a multidimensional barrier to uptake among women who attend Planned Parenthood. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;79(1):46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tekeste M, Hull S, Dovidio JF, et al. Differences in medical mistrust between Black and White women: Implications for patient provider communication about PrEP. AIDS and Behavior. 2018. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connecticut Department of Public Health. HIV Statistics. http://portal.ct.gov/DPH/AIDS--Chronic-Diseases/Surveillance/QuickStats. Accessed February 23, 2019.

- 20.Gamarel KE, Golub SA. Intimacy motivations and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adoption intentions among HIV-negative men who have sex with men (MSM) in romantic relationships. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(2):177–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwakwa HA, Bessias S, Sturgis D, et al. Engaging United States Black communities in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis: Analysis of a PrEP engagement cascade. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018; 110(5):480–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jayakumaran JS, Aaron E, Gracely EJ, Schriver E, Szep Z. Knowledge, attitudes, and acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis among individuals living with HIV in an urban HIV clinic. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0145670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan PS, Rosenberg ES, Sanchez TH, et al. Explaining racial disparities in HIV incidence in Black and White men who have sex with men in Atlanta, GA: A prospective observational cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(6):445–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoots BE, Finlayson T, Nerlander L, Paz-Bailey G. Willingness to take, use of, and indications for pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men - 20 US Cities, 2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):672–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calabrese SK, Krakower DS, Mayer KH. Integrating HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) into routine preventive healthcare to avoid exacerbating disparities. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12):1883–1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golub SA. PrEP stigma: Implicit and explicit drivers of disparity. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15(2):190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kershaw TS, Ethier KA, Niccolai LM, Lewis JB, Ickovics JR. Misperceived risk among female adolescents: Social and psychological factors associated with sexual risk accuracy. Health Psychol. 2003;22(5):523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cornelisse VJ, Fairley CK, Stoove M, et al. Evaluation of PrEP eligibility criteria using sexually transmissible infections as HIV risk markers at enrolment in PrEPX, a large Australian HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(12):1847–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lancki N, Almirol E, Alon L, McNulty M, Schneider JA. Preexposure prophylaxis guidelines have low sensitivity for identifying seroconverters in a sample of young Black MSM in Chicago. AIDS. 2018;32(3):383–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan PS, Giler RM, Mouhanna F, et al. Trends in the use of oral emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for pre-exposure prophylaxis against HIV infection, United States, 2012–2017. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):833–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Preventive Services Task Force. Prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: Pre-exposure prophylaxis. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/draft-recommendation-statement/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Accessed February 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith DK, Van Handel M, Wolitski RJ, et al. Vital signs: Estimated percentages and numbers of adults with indications for preexposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition--United States, 2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(46):1291–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith DK, Van Handel M, Grey JA. Estimates of adults with indications for HIV preexposure prophylaxis by jurisdiction, transmission risk group, and race/ethnicity, United States 2015. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12):859–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Detailed description of Measures and Coding

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Supplementary Eligibility Analyses (eTables 1–4)

Supplemental Digital Content 3. Summary of State-Level PrEP Eligibility Criteria for Women (eTable 5)