Abstract

Consistent with the paradigm shifting observations of David Barker and colleagues that revealed a powerful relationship between decreased weight through 2 years of age and adult disease, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and preterm birth are independent risk factors for the development of subsequent hypertension. Animal models have been indispensable in defining the mechanisms responsible for these associations and the potential targets for therapeutic intervention. Among the modifiable risk factors, micronutrient deficiency, physical immobility, exaggerated stress hormone exposure and deficient trophic hormone production are leading candidates for targeted therapies. With the strong inverse relationship seen between gestational age at delivery and the risk of hypertension in adulthood trumping all other major cardiovascular risk factors, improvements in neonatal care are required. Unfortunately, therapeutic breakthroughs have not kept pace with rapidly improving perinatal survival, and groundbreaking bench-to-bedside studies are urgently needed to mitigate and ultimately prevent the tsunami of prematurity-related adult cardiovascular disease that may be on the horizon. This review highlights our current understanding of the developmental origins of hypertension and draws attention to the importance of increasing the availability of lactation consultants, nutritionists, pharmacists, and physical therapists as critical allies in the battle that IUGR or premature infants are waging not just for survival but also for their future cardiometabolic health.

Keywords: Developmental Origins, Insulin, Leptin, Multidisciplinary, Preterm, Therapy

Introduction

The developmental origins of adult disease construct gained traction following a series of epidemiological studies by Barker and colleagues that suggested early influences during intrauterine and early postnatal development could lead to potentially irreversible modifications in physiology and metabolism that influence disease risk in adulthood. Barker’s seminal observation that the geographic areas in England with the highest infant mortality rate in the early twentieth century went on to report higher rates of coronary heart disease sparked follow-up investigations that demonstrated low birth weight was a strong predictor of subsequent cardiovascular disease risk (Barker et al. 1989a, De Boo and Harding 2006).

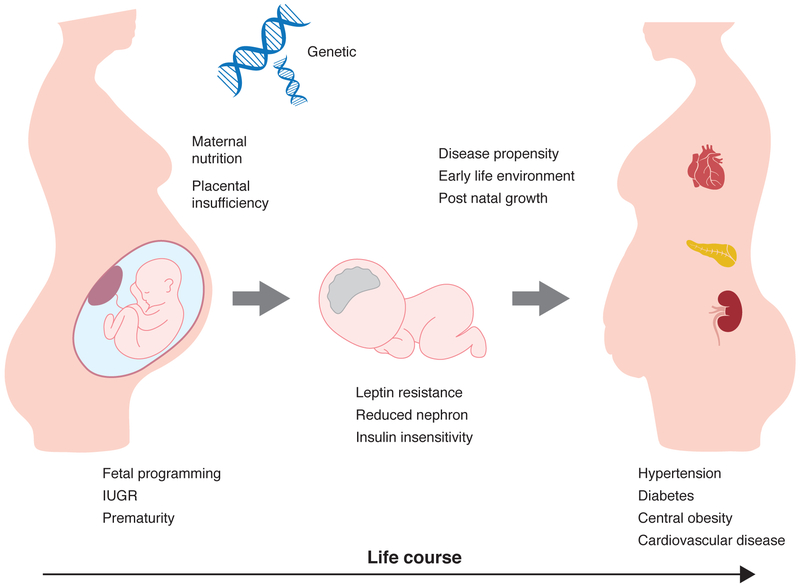

Shorty after the initial publication of the association between low birth weight and adult disease, the “fetal origins” hypothesis was expanded by realization that the vulnerable phase of human development extends beyond the time of parturition. This is especially important when considering preterm infants that emerge from the intrauterine environment more developmentally immature than term infants, who themselves lack the maturation typical of more precocious animal species. Furthermore, low birth weight itself must always be considered a marker, rather than a cause of subsequent disease, with the varying etiologies of low birth weight encompassing relatively benign normal genetic variation and more life threatening events including intrauterine growth restriction and preterm delivery. Herein, after reviewing the mechanistic insight obtained from model species, we turn our attention to recent insight into the perinatal origins of subsequent disease susceptibility with focus on the cardiovascular implications of intrauterine growth restriction and prematurity (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Perinatal factors converge to establish the risk of hypertension. Acting upon genetic susceptibility, maternal health and placental function powerfully influence fetal growth and development. The subsequent hormonal and nutritional milieu impact gene expression and organ morphology, two key determinants of the pathway conceptualized as fetal programming; at times, this adverse intrauterine environment manifests as intrauterine growth restriction or prematurity. Following delivery, the early life environment and postnatal growth continue to reset disease propensity through key regulatory systems, including leptin and insulin signaling pathways, as well as nephron endowment. Over the life course, central leptin resistance, reduced kidney function, and insulin resistance can increase the propensity towards hypertension and other components of the metabolic syndrome, including diabetes and obesity.

I. Developmental Origins in Model Organisms

A. Developmental Origins

Programming is a phenomenon co-opted by the developmental origins hypothesis to explain a process whereby an insult during a critical period of development evokes potentially irreversible long term effects. Gluckman and Hanson (2004) have proposed a more active process where the fetus detects its environment, and uses that information to adapt to the predicted future. Unfortunately, as the environment changes, those predictions can be maladaptive. Even if the adaptations improve immediate survival, they typically come at the cost of long-term health and longevity. This phenomenon, labeled a ‘predictive adaptive response’ is seen across species. A quintessential example of the trade off that occurs between short-term survival and future health is the wood frog (Rana sylvatica). At times of early life adversity, stress hormone exposure causes the tadpole to develop a long strong tail to escape predation and accumulate scarce resources, but after metamorphosis, health and longevity are sacrificed with the early drive for survival leaving the animal with foreshortened size and a loss of competitive advantage (Middlemis et al. 2013).

Regarding the developmental origins of hypertension, multiple downstream mechanisms have been described including vascular alterations, decreased nephron endowment, and hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, especially central leptin–melanocortin signaling pathways (Samuelsson 2014, Taylor et al. 2014). Potential triggers of the pathologic cascade include reduced caloric intake, nutritional imbalance and hypoxia, all of which affect the growth and maturation of organ systems and influence homeostatic regulation. The programming field has benefited from novel investigations in a variety of species, with each species offering distinct advantages. These basic science studies, including prominent investigations in fish, chicken, rodents, and larger mammals have been indispensable in the pursuit of mechanistic and therapeutic advancement.

B. Model Organisms

Given their transparency and ex utero development, zebrafish (Danio rerio) have been an important model species in the elucidation of the genetic requirements for normal cardiovascular development. Studies on the vascular anatomy have defined the ontogeny of vascular networks and the onset of nitric oxide (NO) responsiveness. These data have clearly demonstrated an important reciprocal role of NO as a mediator of vasculogenesis and mediator of nutrient distribution during early development (Clough et al. 2015, Pelster et al. 2005). While developmental insight expands, the zebrafish model has already shown its utility in the exploration of gene-environment interactions seen with a number of programming stimuli, including dysglycemia, dyslipidemia, early nutritional conditioning, oxidative stress, and pharmaceutical exposures (Eeden 2014, Kalichak et al. 2016, Wang et al. 2013, Wilkinson and van Williams et al. 2013).

Chickens retain advantages of fish models, including ex utero development, and they have specific advantages including a cardiac structure more reminiscent of humans. Professor Giussani capitalized on those advantages in a series of fascinating studies that isolated the effects of fetal hypoxia on development by incubating embryos under normoxic (sea level) or hypoxic (high altitude) conditions with prominent cardiovascular changes seen even prior to hatching (Herrera et al. 2013, Salinas et al. 2010). Developmental changes in arterial reactivity have also been described in embryonic and newly hatched chicks in a hypoxic-induced growth restriction model with the data suggesting that the vasodilatation mechanism matures prior to the vasoconstriction mechanism, and that alterations in this maturational timeline, as a result of hypoxic events, can later contribute to a reduced microvascular perfusion capacity (Moonen et al. 2012)

To further explore maternal influences on development, rodent models have been extensively characterized following the introduction of triggers including both genetic mutation and environmental manipulation. Many of these studies initially focused on the influence of maternal nutrition on development of vascular function and blood pressure, and most have shown a strong association between vascular endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in the offspring of both underfed and overfed mothers (Armaitage et al. 2005, Elahi et al. 2009, Khan et al. 2005, Samuelsson et al. 2008). Furthermore, offspring of isocaloric but low protein fed mice also develop high blood pressure and postnatal endothelial dysfunction (Clough 2015). Likewise, rat models of IUGR display endothelial dysfunction as a consequence of impaired NO availability with adult phenotypes including exercise-induced sympathetic over-activation and hypertension (Grandvuillemin et al. 2018, Mizuno et al. 2013).

Experimental rodent models have also interrogated early and late windows of developmental susceptibility by assessing the impact of alterations in antenatal and early postnatal growth and nutrition. Khan et al. (2005) cross-fostered offspring to compare the effects of high fat diet exposure during the prenatal and early postnatal periods, and their data suggest isolated prenatal exposure to high fat diet is sufficient to induce hypertension (Matthews et al. 2011). We have performed a series of complementary investigations by leveraging the natural variation that occurs in rodent growth as a consequence of variance in the intrauterine or postnatal litter size (Hermann et al. 2009). In our investigations, postnatal growth restriction interferes with neurodevelopment and increases the hypertensive response to stress in a pathway dependent on central leptin and angiotensin II signaling (Meyer et al. 2014, Peotta et al. 2016). These alterations can be prevented by neonatal supplementation of the neurotrophic hormone leptin (Erkonen et al. 2011, Vickers et al. 2005).

In sheep, prenatal maternal nutrition and birth size have also been shown to affect fetal cardiovascular development, and the larger animal size has allowed for reproducible assessment of cardiomyocyte kinetics and microvasculature modifications such as decreased capillary density and deviation of normal distribution pattern of metabolic substrates in body tissues (Ma et al. 2010, Costello et al. 2008). Along with others, we have capitalized on the similarities between ovine and human cardiovascular structure and the ability to instrument the developing fetus to demonstrate primary alterations in baroreceptor reflex regulation and coronary artery reactivity that preceded the development of hypertension (Roghair et al. 2005, Segar et al. 2006). Harkening back to Dr. Barker’s initial focus on cardiovascular mortality, it is important to note than both placental insufficiency and fetal anemia have been shown to modulate cardiomyocyte fate, increasing wall stress and the susceptibility to myocardial ischemia (Jonker et al. 2010, Louey et al. 2007). Furthermore, as a species often examined prior to clinical introduction of novel perinatal therapeutics, there is an extensive database regarding the effect of antenatal glucocorticoid exposure on both short-term and long-term outcomes of sheep, with late gestation glucocorticoids shown to have short-term benefit and early gestation glucocorticoid exposure, as seen with maternal-fetal metabolic or psychologic stress, shown to exert detrimental effects on cardiovascular and neuronal development predisposing to hypertension later in life (Dodic et al. 1998, Padbury et al. 1995).

II. Developmental Origins and IUGR

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), a reduction in expected fetal growth, affects approximately 5–15% of all pregnancies in developed countries with at least 6 fold higher rates in developing countries (Sharma et al. 2016, Yzydorczyk et al. 2017). For more than two decades, evidence has accumulated supporting an inverse relationship between birth weight, systolic blood pressure and the prevalence of hypertension. Professor David J.P. Baker was one of the first to describe the relationship and later refine it by noting that, as a stronger surrogate for suboptimal growth, babies that are born small in relation to placental weight were at even greater risk of developing hypertension (Barker et al. 1990). The cause of hypertension is likely multifactorial and affected by both prenatal and postnatal events.

A. Renal Origins

Protein malnutrition, pharmacologic exposures and hypoxia are important causes of a reduction in glomeruli, and reduced nephron number has been considered an important factor associated with elevated blood pressure. Brenner and Chertow (1994) were among the first proposing the association of low birth weight with reduced nephron number and an increased risk of hypertension later in life. While most studies have not reported sex or race-specific results, there appear to be important racial disparities with black infants showing the strongest associations between birthweight and renal function or blood pressure (Cassidy-Bushrow et al. 2012, Hemachandra et al. 2006).

Although birth weight is considered a barometer for the fetal environment, asymmetrical intrauterine growth restriction, which reflects a redistribution of blood flow away from most intraabdominal organs including the kidneys and pancreas, may be a more specific indicator of significant fetal nutrient deficiency (Bagby 2007). Human IUGR and experimental undernutrition in animal models has shown a reduced nephron number in association with asymmetric intrauterine growth restriction (Hinchliffe et al. 1991, Hinchliffe et al. 1992, Merlet-Benichou et al. 1994, Vehaskari et al. 2001, Woods et al. 2001). Additional studies support a link between reduced nephron number and essential hypertension, and fetal kidney weight during nephrogenesis is linearly related to nephron number (Hoy et al. 2005, Hughson et al. 2003, Keller et al. 2003). Moreover, hyperfiltration with intrarenal renin-angiotensin system activation has been theorized to contribute to the prenatal programming of hypertension (Habib et al. 2011). A disorder of prenatal intrarenal renin-angiotensin system programing with altered renal sodium handling has also been proposed to contribute to cardiovascular disease in animals that sustain prenatal insults and develop salt-dependent hypertension as a consequence of the early anomalies in sodium absorption (Bertram et al. 2001, Dagan et al. 2008, Manning et al. 2002).

B. Vascular Origins

Infants born IUGR have increased vascular stiffness and increased intima media thickness resulting in decreased vascular compliance and impaired endothelial-dependent vasodilation; a role for in utero extracellular protein deposition in the cascade that leads to programmed arterial stiffness has been demonstrated in both sheep and guinea pig models of late gestation IUGR by Thompson and colleagues (2011a, 2011b, 2014). These vascular alterations may increase myocardial workload and contribute to the development of hypertension in adulthood (Leeson et al. 1997, Martin et al. 2000, Martyn and Greenwood 1997). While impaired NO-dependent signaling appears to contribute to the vascular phenotype (Roghair et al. 2009), clinical studies have also demonstrated heightened sympathetic tone as an etiology for IUGR-related arterial remodeling, baroreceptor reflex dysfunction and hypertension (Boguszewski et al. 2004, Johansson et al. 2007, Jones et al. 2008). Although prenatal programing limits the postnatal ability to adapt, thus increasing the vulnerability to disease, the postnatal environment plays an important role in reducing or enhancing the likelihood of disease expression. Known exacerbating postnatal factors include nutrient availability and physiologic stress (Bagby 2007).

C. Exacerbation by Growth Acceleration

Eriksson et al. (2000, 2001, 2003) further described a relationship between children that were born small with poor growth in the first year of life followed by rapid weight gain in childhood and hypertension in adulthood (Forsen et al. 2004). In their longitudinal study, Barker et al. (2002) reported that children who developed hypertension later in life were born asymmetrically small for gestation then went on to develop accelerated BMI increment between 3–11 years of age. Evaluating an earlier phase of catch-up growth, Taine et al. (2016) showed that children born small for gestational age with rapid growth velocity in the first few months of life have the highest blood pressures. Prenatal and postnatal weight gain patterns have also been speculated to influence future adiposity and metabolic risk. Rapid postnatal weight gain during the first 2 years of life has been linked to hypertension by Perng and colleagues (2016). Unfortunately, neonatal growth acceleration increases the risk of obesity-related hypertension (Ben-Shlomo et al. 2008), while continued growth failure increases the risk of hypertension beyond the effect of IUGR alone (Barker et al. 1989b, Eriksson et al. 2007). This dichotomy emphasizes the effect of dysregulated genetic growth potential on actualization of the disease vulnerability.

D. Mitigation through Nutrition

While they have known impacts on neurodevelopment, very little is also known regarding the role of perinatal micronutrient and iron deficiencies in relation to blood pressure level in adulthood. Lindberg et al. (2017) generated a hypothesis based on their findings from their randomized double blind controlled trial that the association between low birth weight and increased risk of hypertension in adulthood might be modifiable with micronutrient intervention in infancy such as iron supplements, highlighting the need for ongoing nutritional assessment.

While increased breast milk intake has been shown to improve the metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes of growth restricted experimental animals (Briffa et al. 2017), this has not be definitively evaluated in IUGR infants. In a meta-analysis by Horta et al. (2015), breastfeeding, regardless of IUGR status, decreased the likelihood of developing major cardiovascular risk factors, including type 2 diabetes and obesity, but no association was observed with blood pressure. Similarly, a randomized study of breast feeding duration, in women already intending to breast feed, did not identify an effect on blood pressure in childhood (Martin et al. 2014).

III. Developmental Origins and Prematurity

Prematurity is a major risk factor for hypertension and obesity with the risks increasing with decreasing gestational age (de Jong et al. 2012, Irving et al. 2000, Keijzer-Veen et al. 2005, Leon et al. 2000, Siewert-Delle 1998). Johansson and colleagues (2005) assessed blood pressure in 329,495 military conscripts and observed the odds of hypertension, adjusted for birth weight and current body mass index, increased 93% in subjects born at 24–28 wk gestation and 48% in those born at 29–32 wk gestation. This hypertensive phenotype is present in both males and females, including infants born as late as 35 wk gestation (Bonamy et al. 2012, Gunay et al. 2014, Sipola-Leppänen et al. 2015). Hypertension has both an early onset, with up to 70% of preterm infants demonstrating elevated systolic blood pressure in infancy (Dagle 2011), and a prolonged duration, with hypertension remaining a significant concern into adulthood, especially in the presence of adult obesity (Duncan et al. 2011, Pyhälä et al. 2009).

A. Altered Body Composition and Heightened Sympathetic Activation

Abdominal obesity and the odds of metabolic syndrome are increased by early preterm birth (Sipola-Leppänen et al. 2015), and rebound adiposity with ectopic fat accretion significantly increases the risk of insulin resistance and hypertension (Barker et al. 1989a, Ben-Shlomo et al. 2008, Crane et al. 2016; Eriksson et al. 2007). By the time they reach 36 wk postmenstrual age, nearly 90% of extremely low birth weight infants are growth restricted (Dusick et al. 2003), and they typically remain growth restricted as adults (Hack et al. 2014), but the reduction in body weight often masks an underlying increase in central adiposity (Crume et al. 2014, Hack et al. 2003, Johnson et al. 2012, Uthaya et al. 2005).

Basic science investigation in developmentally immature mice have revealed important comorbid hypertension, behavioral and learning disabilities following growth restriction and steroid exposure. The presence of analogous neurodevelopmental consequences following preterm delivery (Kaur et al.2014, Travis et al. 20015) raise the potential that abnormal neuronal regulation of blood pressure contributes to the origins of hypertension (Miller et al. 2016). Similar to IUGR term infants, preterm infants display features consistent with sympathetic over-activation, including increased catecholamine excretion, increased resting heart rate, and exaggerated pressor response to psychological stress (Johansson et al. 2007, Jones et al. 2007, Pyhala et al. 2009, Ward et al. 2004). The risk of hypertension is also increased in the presence of diabetes and obesity, triggers of sympathetic activation through pathways including the presence of insulin resistance and the elaboration of adipose-derived proteins such as leptin (Bell and Rahmouni 2016).

B. Leptin Deficiency and Insulin Resistance

Leptin and insulin both target hypothalamic neurons and muscle fibers such that a normalization of leptin levels could improve insulin signaling and a reduction in insulin levels could attenuate leptin-evoked sympathetic activation. Within the hypothalamus, leptin triggers central sympathetic tone through a JAK-STAT3 pathway (Dubinion et al. 2013), and insulin enhances leptin-induced STAT3 signaling by inducing the molecular chaperone GRP78 (Thon et al. 2016). Ultimately, hyperinsulinemia induces sympathetic activation in healthy humans (Vaz et al. 2010), and recent investigations have shown the complexity of interactions, with hyperinsulinemia contributing to obesity-linked hypertension and insulin receptors playing an important role in leptin-evoked hypertension (do Carmo et al. 2016, Zhang et al. 2016)

In the presence of sufficient amino acid availability, insulin stimulates muscle hypertrophy through induction of a PI3K–Akt-mTOR pathway (Barazzoni et al. 2012). In elegant preclinical investigations, German and colleagues (2010) showed physiologic leptin replacement improves insulin-stimulated PI3K activation in rats, leading to reductions in body fat and preservation of lean mass, independent of changes in body weight. Yau et al. (2014) subsequently demonstrated that leptin can improve skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity in sheep via induction of IGF binding protein-2. Unfortunately, preterm infants are known to be profoundly leptin deficient, with lower levels in males mirroring the male disadvantage in long-term outcomes of prematurity (Ertl et al. 1999, Ng et al. 2001, Steinbrekera and Roghair 2016).

Like leptin deficiency, insulin resistance may be a critical early factor in the cascade leading to cardiometabolic disease (Thompson and Regnault 2011). Placental insufficiency and other adverse in utero events can alter insulin sensitivity and skeletal muscle mass, increasing the likelihood of type 2 diabetes (Brown et al. 2016, De Blasio et al. 2012, Limesand and Rozance 2017). Likewise, endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodeling are exacerbated by insulin resistance, increasing the likelihood of hypertension (Abe et al. 1998, Federci et al. 2014). The establishment of novel therapeutic interventions aimed at the preservation of insulin sensitivity in the face of environmental adversity may substantially improve the cardiometabolic health of premature infants. In a recent cross-sectional study, Ahmad and colleagues (2016a, 2016b) demonstrated high insulin levels in the cord blood of infants <32 wk vs 32–40 wk gestation. The inverse correlation between insulin levels and gestational age could suggest unique regulation to stimulate growth and maturation while placental transfer maintains euglycemia or could simply mark a state of relative insulin resistance. Investigations in non-human primates suggest the later with reduced muscle content of key glucose transport-regulating proteins, including GLUT1 and GLUT4 in preterm baboons (Blanco et al. 2010). When challenged by euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp, preterm baboons have reduced insulin sensitivity in association with impaired insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation (Blanco et al. 2015). In a complementary late gestation fetal sheep model, Dr. Brown and colleagues (2016) showed chronic euglycemic hyperinsulinemia fails to increase muscle fiber growth in conjunction with tissue hypoxia and increased noradrenaline levels, suggesting an inhibitory effect by environmental stress and counter-regulatory hormones.

C. Immobility and Physical Rehabilitation

Even with adequate nutrient intake, skeletal muscle growth suffers from a lack of physical exercise. Skeletal muscle activity plays a major role in bone health, as evidenced by a reduction in bone density among those with neuromuscular disorders (Khatri et al. 2008). Murine studies have further demonstrated that maternal exercise during pregnancy increases the physical activity and insulin sensitivity of the offspring, with similar effects seen when the offspring themselves are exposed to exercise (Acosta et al. 2015, Blaize et al. 2015, Carter et al. 2012 and 2013, Eclarinal et al. 2016). Within the neonatal intensive care nurseries, infant activity may be discouraged over concern the active infant will consume excessive calories, require higher amounts of oxygen or dislodge critical lines and tubes. Even when unbundled, infants may not have the energy to be active and unit staffing may not support the provision of consistent physical therapy, prompting concerns for infant health that led to the investigation of parent-administered therapy (McQueen et al. 2013, Ustad et al. 2016). There is evidence that specific doses of exercise, administered by physical therapists, can at least transiently improve the growth and bone density of premature infants (Schulzke et al. 2014). Encouragingly, in rodents, the early introduction of physical activity has been shown to improve the metabolic health of individuals exposed to an antenatal high fat diet (Falcão-Tebas et al. 2018).

D. Glucocorticoid Excess and Nutritional Rehabilitation

Beyond the effects of undernutrition and immobility, exposure to excess glucocorticoids can reduce growth, alter body composition and development, and increase blood pressure into adulthood. Again, timing and dosage of exposure are critically important. A single course of late gestation betamethasone administered to women with threatened preterm delivery has not been shown to affect size at birth or offspring blood pressure within 30 years of delivery (De Boo and Harding 2006). However, it is well known that repetitive courses of antenatal steroids in the context of a prolonged threat of preterm delivery, can stimulate maturation at the expense of somatic growth, and low birth weight is associated with increased blood pressure (Barker et al. 1989a, Gennser et al. 1988, Bonamy et al. 2012). Fortunately, exposure to repeated course of antenatal betamethasone has not been associated with cardiometabolic disease in childhood (Cartwright et al. 2018). Postnatal synthetic glucocorticoid administration, including dexamethasone but not hydrocortisone, can evoke a catabolic state with impaired lean tissue growth and cerebral hypoplasia (Lodygensky et al. 2005, Murphy et al. 2001). Iatrogenic growth failure is a source of concern given the associations between brain growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes, and the increasing reports that convalescing preterm infants are already predisposed to altered body composition, including reduced muscle mass and excessive central adiposity (Crume et al. 2014, Hack et al. 2003, Johnson et al. 2012, Uthaya et al. 2005).

Notably, preterm infants are deficient in neurotrophic factors, including leptin, a hormone that is present in breast milk but not infant formulas (Casabiell et al. 1997, O’Connor et al. 2003, Resto et al. 2001). Unlike initial findings in term infants, premature infants randomized to breast milk rather than preterm formula had significantly lower blood pressure in childhood, with a dose-response relationship between the proportion of human milk and later outcomes (Singhal et al. 2001). It is possible the different results in term and preterm infants are reflective of a greater degree of vulnerability among developmentally less mature infants. With a worldwide incidence of prematurity approaching 10% (Beck et al. 2010), long-term follow-up studies focusing on the cardiovascular effects of breastmilk and breastfeeding are needed.

Conclusion

The presence of a detrimental intrauterine and neonatal environment significantly increases the risk of asymmetric growth failure followed by the emergence of central obesity, insulin resistance and leptin deficiency with major implications for cardiovascular and metabolic regulation. IUGR and prematurity also trigger the development of adaptive responses, including increased vascular tone and hyperinsulinism that further increase the vulnerability to development of hypertension. With the assistance of lactation support, an increased reliance on breast milk and breast feeding as a source of nutrition and trophic hormones appears to be beneficial for preterm infants. Consultation with nutritionists and pharmacists can further remedy micronutrient deficiency and therapeutic misadventure. Finally, as an aid to the convalescing IUGR or preterm infant, the early introduction of rehabilitative physical therapy holds the promise to improve lean-fat ratios, enhance musculoskeletal health and attenuate the development of metabolic disease and hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number HL007485).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

There are no conflicts of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this review or the research reported.

References

- Abe H, Yamada N, Kamata K, Kuwaki T, Shimada M, Osuga J, Shionoiri F, Yahagi N, Kadowaki T, Tamemoto H, et al. 1998. Hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and impaired endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation in mice lacking insulin receptor substrate-1. Journal of Clinical Investigation 101 1784–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta W, Meek TH, Schutz H, Dlugosz EM, Vu KT & Garland T Jr 2015. Effects of early-onset voluntary exercise on adult physical activity and associated phenotypes in mice. Physiology & Behavior 149 279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A, Rukmini MS, Yadav C, Agarwal A, Manjrekar PA & Hegde A 2016a. Indices of glucose homeostasis in cord blood in term and preterm newborns. Journal of Clinical Research in Pediatric Endocrinology 8 270–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A, Srikantiah RM, Yadav C, Agarwal A, Manjrekar PA & Hegde A 2016b. Cord blood levels of insulin, cortisol and HOMA2-IR in very preterm, late preterm and term newborns. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 10 BC05–BC08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage JA, Taylor PD & Poston L 2005. Experimental models of developmental programming: Consequences of exposure to an energy rich diet during development. Journal of Physiology 565 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby SP 2007. Maternal nutrition, low nephron number, and hypertension in later life: pathways of nutritional programming. Journal of Nutrition 137 1066–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barazzoni R, Short KR, Asmann Y, Coenen-Schimke JM, Robinson MM & Nair KS 2012. Insulin fails to enhance mTOR phosphorylation, mitochondrial protein synthesis, and ATP production in human skeletal muscle without amino acid replacement. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 303 E1117–E1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Osmond C, Golding J, Kuh D & Wadworth ME 1989a. Growth in utero, blood pressure in childhood and adult life, and mortality from cardiovascular disease. BMJ 298 564–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Winter PD, Osmond C, Margetts B & Simmonds SJ 1989b. Weight in infancy and death from ischaemic heart disease. Lancet 2 577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Bull AR, Osmond C & Simmonds SJ 1990. Fetal and placental size and risk of hypertension in adult life. BMJ 301 259–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Forsen T, Eriksson JG & Osmond C 2002. Growth and living conditions in childhood and hypertension in adult life: a longitudinal study. Journal of Hypertension 20 1951–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck S, Wojdyla D, Say L, Betran AP, Merialdi M, Requejo JH, Rubens C, Menon R & Van Look PF 2010. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: a systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 88 31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell BB & Rahmouni K 2016. Leptin as a mediator of obesity-induced hypertension. Current Obesity Reports 5 397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Y, McCarthy A, Hughes R, Tilling K, Davies D & Smith GD 2008. Immediate postnatal growth is associated with blood pressure in young adulthood: the Barry Caerphilly Growth Study. Hypertension 52 638–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram C, Trowern AR, Copin N, Jackson AA & Whorwood CB 2001. The maternal diet during pregnancy programs altered expression of the glucocorticoid receptor and type 2 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase: potential molecular mechanisms underlying the programming of hypertension in utero. Endocrinology 142 2841–2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaize AN, Pearson KJ & Newcomer SC 2015. Impact of maternal exercise during pregnancy on offspring chronic disease susceptibility. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews 43 198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco CL, Liang H, Joya-Galeana J, DeFronzo RA, McCurnin D & Musi N. 2010. The ontogeny of insulin signaling in the preterm baboon model. Endocrinology 151 1990–1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco CL, McGill-Vargas LL, Gastaldelli A, Seidner SR, McCurnin DC, Leland MM, Anzueto DG, Johnson MC, Liang H, DeFronzo RA, et al. 2015. Peripheral insulin resistance and impaired insulin signaling contribute to abnormal glucose metabolism in preterm baboons. Endocrinology 156 813–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boguszewski MC, Johannsson G, Fortes LC & Sverrisdóttir YB 2004. Low birth size and final height predict high sympathetic nerve activity in adulthood. Journal of Hypertension 22 1157–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonamy AK, Källén K & Norman M 2012. High blood pressure in 2.5-year-old children born extremely preterm. Pediatrics 129 e1199–e1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner BM & Chertow GM 1994. Congenital oligonephropathy and the etiology of adult hypertension and progressive renal injury. American Journal of Kidney Disease 23 171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briffa JF, O’Dowd R, Moritz KM, Romano T, Jedwab LR, McAinch AJ, Hryciw DH & Wlodek ME 2017. Uteroplacental insufficiency reduces rat plasma leptin concentrations and alters placental leptin transporters: ameliorated with enhanced milk intake and nutrition. Journal of Physiology 595 3389–3407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD & Hay WW Jr 2016. Impact of placental insufficiency on fetal skeletal muscle growth. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 435 69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LD, Wesolowski SR, Kailey J, Bourque S, Wilson A, Andrews SE, Hay WW Jr & Rozance PJ 2016. Chronic hyperinsulinemia increases myoblast proliferation in fetal sheep skeletal muscle. Endocrinology 157 2447–2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter LG, Lewis KN, Wilkerson DC, Tobia CM, Ngo Tenlep SY, Shridas P, Garcia-Cazarin ML, Wolff G, Andrade FH, Charnigo RJ, et al. 2012. Perinatal exercise improves glucose homeostasis in adult offspring. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 303 E1061–E1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter LG, Qi NR, De Cabo R & Pearson KJ 2013. Maternal exercise improves insulin sensitivity in mature rat offspring. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 45 832–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright RD, Harding JE, Crowther CA, Cutfield WS, Battin MR, Dalziel SR & McKinlay CJD 2018. Repeat antenatal betamethasone and cardiometabolic outcomes. Pediatrics 142 (1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casabiell X, Piñeiro V, Tomé MA, Peinó R, Diéguez C & Casanueva FF 1997. Presence of leptin in colostrum and/or breast milk from lactating mothers: a potential role in the regulation of neonatal food intake. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 82 4270–4273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Wegienka G, Barone CJ 2nd, Valentini RP, Yee J, Havstad S & Johnson CC. 2012. Race-specific relationship of birth weight and renal function among healthy young children. Pediatric Nephrology 27 1317–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough GF 2015. Developmental conditioning of the vasculature. Comprehensive Physiology 5 397–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello PM, Rowlerson A, Astaman NA, Anthony FE, Sayer AA, Cooper C, Hanson MA & Green LR 2008. Peri‐implantation and late gestation maternal undernutrition differentially affect fetal sheep skeletal muscle development. Journal of Physiology 586 2371–2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane JD, Yellin SA, Ong FJ, Singh NP, Konyer N, Noseworthy MD, Schmidt LA, Saigal S & Morrison KM 2016. ELBW survivors in early adulthood have higher hepatic, pancreatic and subcutaneous fat. Science Reports 6 31560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crume TL, Scherzinger A, Stamm E, McDuffie R, Bischoff KJ, Hamman RF & Dabelea D 2014. The long-term impact of intrauterine growth restriction in a diverse U.S. cohort of children: the EPOCH study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 22 608–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagan A, Kwon HM, Dwarkanath V & Baum M 2008. Effect of renal denervation on prenatal programing of hypertension and renal tubular transporter abundance. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 295 F29–F34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagle JM, Fisher TJ, Haynes SE, Berends SK, Brophy PD, Morriss FH Jr & Murray JC 2011. Cytochrome P450 (CYP2D6) genotype is associated with elevated systolic blood pressure in preterm infants after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit. Journal of Pediatrics 159 104–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Blasio MJ, Gatford KL, Harland ML, Robinson JS & Owens JA 2012. Placental restriction reduces insulin sensitivity and expression of insulin signaling and glucose transporter genes in skeletal muscle, but not liver, in young sheep. Endocrinology 153 2142–2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boo HA & Harding JE 2006. The developmental origins of adult disease (Barker hypothesis). Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 46 4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong F, Monuteaux MC, van Elburg RM, Gillman MW & Belfort MB 2012. Systematic review and meta-analysis of preterm birth and later systolic blood pressure. Hypertension 59 226–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Wang Z, Freeman NJ, Alsheik AJ, Adi A & Hall JE 2016. Regulation of blood pressure, appetite, and glucose by leptin after inactivation of insulin receptor substrate 2 signaling in the entire brain or in proopiomelanocortin neurons. Hypertension 67 378–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodic M, May CN, Wintour EM & Coghlan JP 1998. An early prenatal exposure to excess glucocorticoid leads to hypertensive offspring in sheep. Clinical Science (London) 94 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubinion JH, do Carmo JM, Adi A, Hamza S, da Silva AA & Hall JE 2013. Role of proopiomelanocortin neuron Stat3 in regulating arterial pressure and mediating the chronic effects of leptin. Hypertension 61 1066–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AF, Heyne RJ, Morgan JS, Ahmad N & Rosenfeld CR 2011. Elevated systolic blood pressure in preterm very-low-birth-weight infants ≤3 years of life. Pediatric Nephrology 26 1115–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusick AM, Poindexter BB, Ehrenkranz RA & Lemons JA 2003. Growth failure in the preterm infant: can we catch up? Seminars in Perinatology 27 302–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eclarinal JD, Zhu S, Baker MS, Piyarathna DB, Coarfa C, Fiorotto ML & Waterland RA 2016. Maternal exercise during pregnancy promotes physical activity in adult offspring. FASEB Journal 30 2541–2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elahi MM, Cagampang FR, Mukhtar D, Anthony FW, Ohri SK & Hanson MA 2009. Long‐term maternal high‐fat feeding from weaning through pregnancy and lactation predisposes offspring to hypertension, raised plasma lipids and fatty liver in mice. British Journal of Nutrition 102 514–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson J, Forsen T, Tuomilehto J, Osmond C & Barker D 2000. Foetal and childhood growth and hypertension in adult life. Hypertension 36 790–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Tuomilehto J, Osmond C & Barker DJ. 2001. Early growth and coronary heart disease in later life: longitudinal study. British Medical Journal 322 949–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Tuomilehto J, Osmond C & Barker DJ 2003. Early adiposity rebound in childhood and risk of Type 2 diabetes in adult life. Diabetologia 46 190–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson JG, Forsén TJ, Kajantie E, Osmond C & Barker DJ 2007. Childhood growth and hypertension in later life. Hypertension 49 1415–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkonen GE, Hermann GM, Miller RL, Thedens DL, Nopoulos PC, Wemmie JA & Roghair RD 2011. Neonatal leptin administration alters regional brain volumes and blocks neonatal growth restriction-induced behavioral and cardiovascular dysfunction in male mice. Pediatric Research 69 406–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl T, Funke S, Sárkány I, Szabó I, Rascher W, Blum WF & Sulyok E 1999. Postnatal changes of leptin levels in full-term and preterm neonates: their relation to intrauterine growth, gender and testosterone. Biology of the Neonate 75 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcão-Tebas F, Kuang J, Arceri C, Kerris JP, Andrikopoulos S, Marin EC & McConell GK. 2019. Four weeks of exercise early in life reprograms adult skeletal muscle insulin resistance caused by paternal high fat diet. Journal of Physiology 597 121–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federici M, Pandolfi A, De Filippis EA, Pellegrini G, Menghini R, Lauro D, Cardellini M, Romano M, Sesti G, Lauro R, et al. 2004. G972R IRS-1 variant impairs insulin regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in cultured human endothelial cells. Circulation 109 399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsen T, Osmond C, Eriksson JG & Barker DJ 2004. Growth of girls who later develop coronary heart disease. Heart 90 20–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennser G, Rymark P & Isberg PE 1988. Low birth weight and risk of high blood pressure in adulthood. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.) 296 1498–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German JP, Wisse BE, Thaler JP, Oh-I S, Sarruf DA, Ogimoto K, Kaiyala KJ, Fischer JD, Matsen ME, Taborsky GJ Jr, et al. 2010. Leptin deficiency causes insulin resistance induced by uncontrolled diabetes. Diabetes 59 1626–1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluckman PD and Hanson MA 2004. Developmental origins of disease paradigm: a mechanistic and evolutionary perspective. Pediatric Research 56 311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandvuillemin I, Buffat C, Boubred F, Lamy E, Fromonot J, CHarpiot P, Simoncini S, Sabatier F, Dignat-George Francoise, Peyter Anne-Christine, et al. 2018. Arginase upregulating and eNOS uncoupling contribute to impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in a rat model of intrauterine growth restriction. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative Comprehensive Physiology 315 R509–R520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunay F, Alpay H, Gokce I & Bilgen H 2014. Is late-preterm birth a risk factor for hypertension in childhood? European Journal of Pediatrics 173 751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib S, Zhang Q & Baum M 2011. Prenatal programming of hypertension in the rat: effect of postnatal rearing. Nephron Extra 1 157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack M, Schluchter M, Cartar L, Rahman M, Cuttler L & Borawski E 2003. Growth of very low birth weight infants to age 20 years. Pediatrics 112 e30–e38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack M, Schluchter M, Margevicius S, Andreias L, Taylor HG & Cuttler L 2014. Trajectory and correlates of growth of extremely-low-birth-weight adolescents. Pediatric Research 75 358–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemachandra AH, Klebanoff MA & Furth SL 2006. Racial disparities in the association between birth weight in the term infant and blood pressure at age 7 years: results from the collaborative perinatal project. Journal of American Society of Nephrology 17 2576–2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann GM, Miller RL, Erkonen GE, Dallas LM, Hsu E, Zhu V & Roghair RD 2009. Neonatal catch up growth increases diabetes susceptibility but improves behavioral and cardiovascular outcomes of low birth weight male mice. Pediatric Research 66 53–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera EA, Salinas CE, Blanco CE, Villena M, Giussani DA 2013. High altitude hypoxia and blood pressure dysregulation in adult chickens. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health & Disease 4 69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliffe SA, Sargent PH, Howard CV, Chan YF & van Velzen D 1991. Human intrauterine renal growth expressed in absolute number of glomeruli assessed by the dissector method and Cavalieri principle. Lab Investigation 64 777–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliffe SA, Lynch MR, Sargent PH, Howard CV & van Velzen D 1992. The effect of intrauterine growth retardation on the development of renal nephrons. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 99 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horta BL, Loret de Mola C & Victora CG 2015. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatrica 104 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy W, Hughson MD, Bertram JF, Douglas-Denton R & Amann K 2005. Nephron number, hypertension, renal disease, and renal failure. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 16 2557–2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughson M, Farris AB, Douglas-Denton R, Hoy WE & Bertram JF 2003. Glomerular number and size in autopsy kidneys: the relationship to birth weight. Kidney International 63 2113–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving RJ, Belton NR, Elton RA & Walker BR 2000. Adult cardiovascular risk factors in premature babies. Lancet 355 2135–2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson S, Iliadou A, Bergvall N, Tuvemo T, Norman M & Cnattingius S 2005. Risk of high blood pressure among young men increases with the degree of immaturity at birth. Circulation 112 3430–3436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson S, Norman M, Legnevall L, Dalmaz Y, Lagercrantz H & Vanpée M 2007. Increased catecholamines and heart rate in children with low birth weight: perinatal contributions to sympathoadrenal overactivity. Journal of Internal Medicine 261 480–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MJ, Wootton SA, Leaf AA & Jackson AA. 2012. Preterm birth and body composition at term equivalent age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 130 e640–e649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A, Beda A, Ward AM, Osmond C, Phillips DI, Moore VM & Simpson DM 2007. Size at birth and autonomic function during psychological stress. Hypertension 49 548–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A, Beda A, Osmond C, Godfrey KM, Simpson DM & Phillips DI 2008. Sex-specific programming of cardiovascular physiology in children. European Heart Journal 29 2164–2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonker SS, Giraud MK, Giraud GD, Chattergoon NN, Louey S, Davis LE, Faber JJ & Thornburg KL 2010. Cardiomyocyte enlargement, proliferation and maturation during chronic fetal anaemia in sheep. Experimental Physiology 95:131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichak F, Idalencio R, Rosa JG, de Oliveira TA, Koakoski G, Gusso D, de Abreu MS, Giacomini AC, Barcellos HH, Fagundes M, et al. 2016. Waterborne psychoactive drugs impair the initial development of Zebrafish. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 41 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Powell S, He L, Pierson CR & Parikh NA 2014. Reliability and repeatability of quantitative tractography methods for mapping structural white matter connectivity in preterm and term infants at term-equivalent age. PLoS One 9 e85807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keijzer-Veen MG1, Finken MJ, Nauta J, Dekker FW, Hille ET, Frölich M, Wit JM& van der Heijden AJ 2005. Is blood pressure increased 19 years after intrauterine growth restriction and preterm birth? A prospective follow-up study in the Netherlands. Pediatrics 116 725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller G, Zimmer G, Mall G, Ritz E & Amann K 2003. Nephron number in patients with primary hypertension. New England Journal of Medicine 348 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan IY, Dekou V, Douglas G, Jensen R, Hanson MA, Poston L & Taylor PD 2005. A high‐fat diet during rat pregnancy or suckling induces cardiovascular dysfunction in adult offspring. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative Comprehensive Physiology 288 R127–R133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri IA, Chaudhry US, Seikaly MG, Browne RH & Iannaccone ST 2008. Low bone mineral density in spinal muscular atrophy. Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease 10 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeson CP, Whincup PH, Cook DG, Donald AE, Papacosta O, Lucas A & Deanfield JE 1997. Flow-mediated dilation in 9- to 11-year-old children: the influence of intrauterine and childhood factors. Circulation 96 2233–2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon DA, Johansson M & Rasmussen F 2000. Gestational age and growth rate of foetal mass are inversely associated with systolic blood pressure in young adults: an epidemiologic study of 165136 Swedish men aged 18 years. American Journal of Epidemiology 152 597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limesand SW & Rozance PJ 2017. Fetal adaptations in insulin secretion result from high catecholamines during placental insufficiency. Journal of Physiology 595 5103–5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg J, Norman M, Westrup B, Domellof M & Berglund SK 2017. Lower systolic blood pressure at age 7 y in low-birth-weight children who received iron supplements in infancy: results from a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 106 475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodygensky GA, Rademaker K, Zimine S, Gex-Fabry M, Lieftink AF, Lazeyras F, Groenendaal F, de Vries LS & Huppi PS 2005. Structural and functional brain development after hydrocortisone treatment for neonatal chronic lung disease. Pediatrics 116 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louey S, Jonker SS, Giraud GD & Thornburg KL 2007. Placental insufficiency decreases cell cycle activity and terminal maturation in fetal sheep cardiomyocytes. Journal of Physiology 580 639–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Zhu MJ, Zhang L, Hein SM, Nathanielsz PW & Ford SP 2010. Maternal obesity and overnutrition alter fetal growth rate and cotyledonary vascularity and angiogenic factor expression in the ewe. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative Comprehensive Physiology 299 R249–R258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning j, Beutler K, Knepper MA & Vehaskari VM 2002. Upregulating of renal BSC1 and TSC in prenatally programmed hypertension. American Journal of Physiology 283 F202–F206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin H, Gazelius B & Norman M. 2000. Impaired acetylcholine-induced vascular relaxation in low birth weight infants: implications for adult hypertension? Pediatric Research 47 457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RM, Patel R, Kramer MS, Vilchuck K, Bogdanovich N, Sergeichick N, Gusina N, Foo Y, Palmer T, Thompson J, et al. 2014. Effects of promoting longer-term and exclusive breastfeeding on cardiometabolic risk factors at age 11.5 years: a cluster-randomized, controlled trial. Circulation 129 321–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn CN & Greenwald SE 1997. Impaired synthesis of elastin in walls of aorta and large conduit arteries during early development as an initiating event in pathogenesis of systemic hypertension. Lancet 350 953–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews PA, Samuelsson AM, Seed P, Pombo J, Oben JA, Poston L & Taylor PD 2011. Fostering in mice induces cardiovascular and metabolic dysfunction in adulthood. Journal of Physiology 589 3969–3981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen D, Lakes K, Rich J, Vaughan J, Hayes G, Cooper D & Olshansky E 2013. Feasibility of a caregiver-assisted exercise program for preterm infants. Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing 27 184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlet-Benichou C, Gilbert T, Muffat-Joly M, Lelievre-Pegorier M & Leroy B 1994. Intrauterine growth retardation leads to a permanent nephron deficit in the rat. Pediatric Nephrology 8 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer LR, Zhu V, Miller A & Roghair RD 2014. Growth restriction, leptin, and the programming of adult behavior in mice. Behavioural Brain Research 275 131–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlemis Maher J, Werner EE & Denver RJ 2013. Stress hormones mediate predator-induced phenotypic plasticity in amphibian tadpoles. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 280 20123075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SL, Huppi PS & Mallard C 2016. The consequences of fetal growth restriction on brain structure and neurodevelopmental outcome. Journal of Physiology 594 807–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno M, Siddique K, Baum M & Smith SA 2013. Prenatal programming of hypertension induces sympathetic overactivity in response to physical stress. Hypertension 61 180–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moonen RM, Kessels CG, Zimmermann LJ & Villamor E 2012. Mesenteric artery reactivity and small intestine morphology in a chicken model of hypoxia‐induced fetal growth restriction. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 63 601–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BP, Inder TE, Huppi PS, Warfield S, Zientara GP, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA & Volpe JJ 2001. Impaired cerebral cortical gray matter growth after treatment with dexamethasone for neonatal chronic lung disease. Pediatrics 107 217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng PC, Lam CW, Lee CH, Wong GW, Fok TF, Wong E, Chan IH & Ma KC 2001. Changes of leptin and metabolic hormones in preterm infants: a longitudinal study in early postnatal life. Clinical Endocrinology (Oxford) 54 673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor D, Funanage V, Locke R, Spear M. & Leef K 2003. Leptin is not present in infant formulas. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 26 490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padbury JF, Polk DH, Ervin MG, Berry LM, Ikegami M, Jobe AH 1995. Postnatal cardiovascular and metabolic responses to a single intramuscular dose of betamethasone in fetal sheep born prematurely by cesarean section. Pediatr Res 38 709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelster B, Grillitsch S & Schwerte T 2005. NO as a mediator during the early development of the cardiovascular system in the zebrafish. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A 142 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peotta V, Rahmouni K, Segar JL, Morgan DA, Pitz KM, Rice OM & Roghair RD 2016. Neonatal growth restriction-related leptin deficiency enhances leptin-triggered sympathetic activation and central angiotensin II receptor-dependent stress-evoked hypertension. Pediatric Research 80 244–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perng W, Hajj H, Belfort MB, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kramer MS, Gillman MW & Oken E 2016. Birth size, early life weight gain, and midchildhood cardiometabolic health. The Journal of Pediatrics 173 122–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyhälä R, Räikkönen K, Feldt K, Andersson S, Hovi P, Eriksson JG, Järvenpää AL & Kajantie E 2009. Blood pressure responses to psychosocial stress in young adults with very low birth weight: Helsinki study of very low birth weight adults. Pediatrics 123 731–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resto M, O’Connor D, Leef K, Funanage V, Spear M & Locke R 2001. Leptin levels in preterm human breast milk and infant formula. Pediatrics 108 E15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roghair RD, Segar JL, Sharma RV, Zimmerman MC, Jagadeesha DK, Segar EM, Scholz TD & Lamb FS 2005. Newborn lamb coronary artery reactivity is programmed by early gestation dexamethasone before the onset of systemic hypertension. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative Comprehensive Physiology 289 R1169–R1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roghair RD, Segar JL, Volk KA, Chapleau MW, Dallas LM, Sorenson AR, Scholz TD & Lamb FS 2009. Vascular nitric oxide and superoxide anion contribute to sex-specific programmed cardiovascular physiology in mice. American Journal of Physiology: Regulatory Integrative Comprehensive Physiology 296 R651–R662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas CE, Blanco CE, Villena M, Camm EJ, Tuckett JD, Weerakkody RA, Kane AD, Shelley AM, Wooding FB, Quy M, et al. 2010. Cardiac and vascular disease prior to hatching in chick embryos incubated at high altitude. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease 1 60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson AM 2014. New perspectives on the origin of hypertension; the role of the hypothalamic melanocortin system. Experimental Physiology Special Issue: The Physiology and Pathophysiology of Obesity 9 1110–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson AM, Matthews PA, Argenton M, Christie MR, McConnell JM, Jansen EH, Piersma AH, Ozanne SE, Twinn DF, Remacle C, et al. 2008. Diet‐induced obesity in female mice leads to offspring hyperphagia, adiposity, hypertension, and insulin resistance: A novel murine model of developmental programming. Hypertension 51 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulzke SM, Kaempfen S, Trachsel D & Patole SK 2014. Physical activity programs for promoting bone mineralization and growth in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews 4 CD005387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segar JL, Roghair RD, Segar EM, Bailey MC, Scholz TD & Lamb FS 2006. Early gestation dexamethasone alters baroreflex and vascular responses in newborn lambs before hypertension. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative Comprehensive Physiology 291 R481–R488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D, Shastri S & Sharma P 2016. Intrauterine growth restriction: antenatal and postnatal aspects. Clinical Medicine Insights: Pediatrics 10 67–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siewert-Delle A & Ljungman S 1998. The impact of birth weight and gestational age on blood pressure in adult life: a population-based study of 49-year-old men. American Journal of Hypertension 11 946–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal A, Cole TJ & Lucas A 2001. Early nutrition in preterm infants and later blood pressure: two cohorts after randomised trials. Lancet 357 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipola-Leppänen M, Vääräsmäki M, Tikanmäki M, Matinolli HM, Miettola S, Hovi P, Wehkalampi K, Ruokonen A, Sundvall J, Pouta A, et al. 2015. Cardiometabolic risk factors in young adults who were born preterm. American Journal of Epidemiology 181 861–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrekera B & Roghair R 2016. Modeling the impact of growth and leptin deficits on the neuronal regulation of blood pressure. Journal of Endocrinology 231 R47–R60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taine M, Stengel B, Forhan A, Carles S, Botton J, Charles MA & Heude B. 2016. Rapid early growth may modulate the association between birth weight and blood pressure at 5 years in the EDEN cohort study. Hypertension 68 859–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor PD, Samuelsson AM & Poston L 2014. Maternal obesity and the developmental programming of hypertension: a role for leptin. Acta Physiologica 210 508–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JA & Regnault TR 2011. In utero origins of adult insulin resistance and vascular dysfunction. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine 29 211–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JA, Gros R, Richardson BS, Piorkowska K & Regnault TR 2011. Central stiffening in adulthood linked to aberrant aortic remodeling under suboptimal intrauterine conditions. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative Comprehensive Physiology 301 R1731–R1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JA, Richardson BS, Gagnon R & Regnault TR 2011. Chronic intrauterine hypoxia interferes with aortic development in the late gestation ovine fetus. Journal of Physiology 589 3319–3332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JA, Sarr O, Piorkowska K, Gros R & Regnault TR 2014. Low birth weight followed by postnatal over-nutrition in the guinea pig exposes a predominant player in the development of vascular dysfunction. Journal of Physiology 592 5429–5443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thon M, Hosoi T & Ozawa K 2016. Insulin enhanced leptin-induced STAT3 signaling by inducing GRP78. Science Reports 6 34312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis KE, Adams JN, Ben-Shachar M & Feldman HM 2015. Decreased and increased anisotropy along major cerebral white matter tracts in preterm children and adolescents. PLoS One 10 e0142860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ustad T, Evensen KA, Campbell SK, Girolami GL, Helbostad J, Jørgensen L, Kaaresen PI & Øberg GK 2016. Early parent-administered physical therapy for preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 138 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthaya S, Thomas EL, Hamilton G, Dore CJ, Bell J & Modi N 2005. Altered adiposity after extremely preterm birth. Pediatric Research 57 211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz M, Sucharita S, Srivatsa DV, Unni US, Raj T & Kurpad AV 2010. Cardiac autonomic responses to hyperinsulinemia are associated with skeletal muscle function in healthy human subjects. Autonomic Neuroscience 152 96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vehaskari VM, Aviles DH & Manning J 2001. Prenatal programming of adult hypertension in the rat. Kidney International 59 238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers MH, Gluckman PD, Coveny AH, Hofman PL, Cutfield WS, Gertler A, Breier BH & Harris M 2005. Neonatal leptin treatment reverses developmental programming. Endocrinology 146 4211–4216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Mao Y, Cui T, Tang D & Wang XL 2013. Impact of a combined high cholesterol diet and high glucose environment on vasculature. PLoS One 8 e81485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward AM, Moore VM, Steptoe A, Cockington RA, Robinson JS & Phillips DI 2004. Size at birth and cardiovascular responses to psychological stressors: evidence for prenatal programming in women. Journal of Hypertension 22 2295–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson RN & van Eeden FJ 2014. The zebrafish as a model of vascular development and disease. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science 124 93–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LM, Timme‐Laragy AR, Goldstone JV, McArthur AG, Stegeman JJ, Smolowitz RM & Hahn ME 2013. Developmental expression of the Nfe2‐related factor (Nrf) transcription factor family in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. PLoS One 8 e79574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods LL, Ingelfinger JR, Nyengaard JR & Rasch R 2001. Maternal protein restriction suppresses the newborn renin-angiotensin system and programs adult hypertension in rats. Pediatric Research 49 460–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau SW, Henry BA, Russo VC, McConell GK, Clarke IJ, Werther GA & Sabin MA 2014. Leptin enhances insulin sensitivity by direct and sympathetic nervous system regulation of muscle IGFBP-2 expression: evidence from nonrodent models. Endocrinology 155 2133–2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yzydorczyk C, Armengaud JB, Peyter AC, Chehade H, Cachat F, Juvet C, Siddeek B, Simoncini S, Sabatier F, Dignat-George F, et al. 2017. Endothelial dysfunction in individuals born after fetal growth restriction: cardiovascular and renal consequences and preventive approaches. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease 8 448–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Zhang H, Li S, Li Y, Liu Y, Fernandez C, Harville E, Bazzano L, He J, Chen W 2016. Impact of adiposity on incident hypertension Is modified by insulin resistance in adults: longitudinal observation from the Bogalusa Heart Study. Hypertension 67 56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]