Abstract

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) type V is an ultrarare heritable bone disorder caused by the heterozygous c.−14C>T mutation in IFITM5. The oro-dental and craniofacial phenotype has not been described in detail, which we therefore undertook to evaluate in a multicenter study (Brittle Bone Disease Consortium). Fourteen individuals with OI type V (age 3 to 50 years; 10 females, 4 males) underwent dental and craniofacial assessment. None of the individuals had dentinogenesis imperfecta. Six of the 9 study participants (66%) for whom panoramic radiographs were obtained had at least one missing tooth (range 1 to 9). Class II molar occlusion was present in 8 (57%) of the 14 study participants. The facial profile was retrusive and lower face height was decreased in 8 (57%) individuals. Cephalometry, performed in three study participants, revealed a severely retrusive maxilla and mandible, and moderately to severly retroclined incisors in a 14-year old girl, a protrusive maxilla and a retrusive mandible in a 14-year old boy. Cone beam computed tomograpy scans were obtained from two study participants and demonstrated intervertebral disc calcification at the C2–C3 level in one individual. Our study observed that OI type V is associated with missing permanent teeth, especially permanent premolar, but not with dentinogenesis imperfecta. The pattern of craniofacial abnormalities in OI type V thus differs from that in other severe OI types, such as OI type III and IV, and could be described as a bimaxillary retrusive malocclusion with reduced lower face height and multiple missing teeth.

Keywords: Osteogenesis Imperfecta, Craniofacial, Oligodontia, Dental, Fractures, IFITM5

Introduction

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a heritable connective tissue disorder that is associated with bone fragility and often short stature (1). About 90% of individuals with a clinical diagnosis of OI have variants in COL1A1 and COL1A2, the genes encoding collagen type I alpha chains (2). Clinically, such patients are classified into OI types I (least severe form), OI type II (perinatal lethal), OI type III (severe), OI type IV (moderate severity). There is presently no cure for OI, but bisphosphonate drugs are widely administered to increase bone density and decrease the number of fractures (1). Apart from fractures in long bones and vertebra, individuals with COL1A1- and COL1A2–related OI often have dental and craniofacial abnormalities, including dentinogenesis imperfecta (DI), tooth agenesis and malocclusion (3–5).

Among OI types not caused by COL1A1 or COL1A2, OI type V is the most prevalent disorder (6). OI type V is caused by the recurrent heterozygous c.−14C>T variant in IFITM5, which encodes BRIL, a transmembrane protein with unknown function that is specifically expressed in osteoblasts (7–9). The variant creates a new translational start site and leads to the addition of 5 amino acids at the N-terminus of the BRIL protein. OI type V resembles OI type IV with regard to fracture incidence, long-bone deformities, vertebral compression fractures and scoliosis (10, 11), but also has distinguishing features such as hyperplastic callus formation and calcification of the interosseous forearm membrane (10, 12). How the addition of 5 amino acids to BRIL protein leads to bone fragility is unknown at present. Mouse models harboring the OI type V variant die at birth, which complicates mechanistic studies (13, 14).

Although OI type V seems to lead to similar bone material abnormalities and bone fragility as OI type IV caused by COL1A1/COL1A2 mutations (10, 15), little is known about the involvement of the craniofacial skeleton and teeth in OI type V. Previous reports on OI type V stated that affected individuals did not have clinical signs of DI (10, 16, 17), but missing teeth, short roots and ectopic eruption of the molars have been reported (17). A prospective, detailed characterization of the craniofacial and dental phenotype in a cohort of OI type V has not been performed.

In the present report we therefore evaluated the oro-dental and craniofacial characteristics in a cohort of individuals with OI type V who were identified through the Brittle Bone Disease Consortium, a multicenter Rare Disease Clinical Research Network.

Materials and Methods

Study Participants

Individuals with a diagnosis of OI type V were recruited through the Brittle Bone Disease Consortium (https://www.rarediseasesnetwork.org/cms/BBD) that comprises several specialized centers from across North America (Houston, Montreal, Chicago, Baltimore, Portland, Washington DC, New York, Omaha, Los Angeles). One of the projects conducted by the consortium is a natural history study to assess the clinical features of OI. Patients with a diagnosis of OI of any type and any age are eligible to participate. Dental evaluation is offered to participants who are three years of age or older.

The present study analyzes baseline dental data from the 14 study participants (10 females, 4 males; age range 3 to 50 years) who had a diagnosis of OI type V. Two individuals in addition agreed to participate in an ancillary study involving cone beam computed tomography (CBCT). For 11 individuals, the diagnosis of OI type V was confirmed by genetic testing (heterozygosity for the c.−14C>T variant in IFITM5); in 3 participants the diagnosis was based on specific clinical findings alone (ossification of the interosseous membrane of the forearm, hyperplastic callus formation) because DNA was not available for analysis. Three cephalometric radiographs were also studied. The study was approved at all participating study centers, and all study participants or their legal guardians provided informed consent.

Craniofacial and dental evaluations

The dental evaluation comprised clinical examination and extra- and intraoral photographs for all study participants, panoramic radiographs for those participants aged six years and older who consented to the test. The study dentist at each site performed the intraoral clinical examination and was responsible for obtaining a standard set of intraoral and extraoral photographs as well as panoramic radiographs. Examiners had been calibrated by passing the simplified International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) examination (18). The photographs and radiographs were uploaded to the study website and were independently assessed by two experienced central readers, an orthodontist and an oral radiologist. There were no inter-observer disagreements on the assessments presented here. CBCT scans were evaluated by an oral and maxillofacial radiologist.

The clinical dental examination included assessing the classification of molar occlusion, overbite, overjet, crowding, open bite, crossbite, arch shape and the presence of DI (said to be present if at least one tooth appearing opalescent or had gray, brown or yellow color). The presence of DI was also assessed by examining panoramic radiographs (radiographic criteria for DI were: partial or complete pulp obliteration, rated according to Jacobsen and Kerekes (19); cervical constrictions).

Lateral and frontal photographs were used to assess facial type (normocephalic, brachycephalic or dolichocephalic), and profile (normal, concave or convex). The facial type was determined by using the facial index that was calculated as the ratio between the maximum width to the maximum length of the face on the frontal photograph: dolichocephalic (long and narrow face), <0.72; normocephalic, 0.72 to 0.82; brachycephalic (short and wide face), >0.82 (20). Facial proportions were calculated as follows: total face height, distance between glabella and soft tissue pogonion (the most anteroinferior point of the chin); upper face height, distance between glabella and subnasale; lower face height, distance between subnasale and the soft tissue pogonion. A lower face height less than 47% of total face height was classified as reduced; a lower face height more than 63% of total face height was classified as increased (21). Profile assessment was performed by measuring the angle between glabella, subnasale, and soft tissue pogonion in a full profile picture. An angle between 158 and 180 degrees was considered normal, regardless of sex (22). An angle <158 degrees indicates a convex profile while an angle >180 degree represents a flat to concave profile.

Lateral cephalometric radiographs were analyzed using the Ceph Tracing routine of the Dolphin Imaging software package (version 11.8). Results were compared to normative cephalometric data as published (23). CBCT scans were acquired with a 3D Accuitomo 170 (Morita Inc, Kyoto, Japan) CBCT machine in a 170 mm × 120 mm field-of-view and a 250 μm voxel size. The exposure settings for CBCT included a tube voltage of 90 kV and a tube current of 4.5 mA for 17.5 seconds. Image analysis was performed using Anatomage InVivo 5 version 5.4 (Invivo Dental; Anatomage, San Jose, CA) software. Panoramic radiographs were analyzed to identify missing teeth, retained or impacted teeth as well as malformed teeth. Impaction or retention was identified as a tooth failing to erupt within 3 years of the normal development window (24).

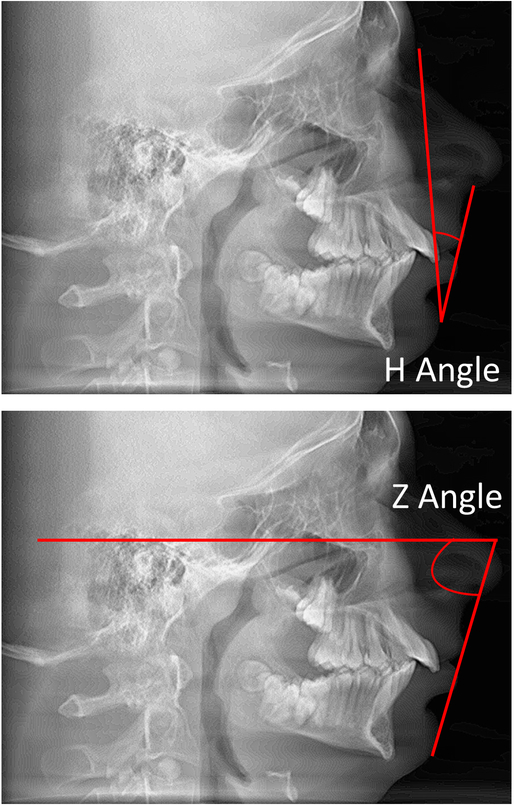

In order to evaluate the projection of the lip and the convexity of the lower face, two measurements were used (Figure 1).The H angle measures the prominence of the lips in relation to the facial line (Nasion soft-pogonion soft: Normal mean value: 6 degrees, standard deviation 3 degrees) (25). The Z angle is used to measure facial balance and measures the prominence of the lips or the relative retrusiveness of the chin. The Z angle is formed by the intersection of the lines Nasion (soft tissue)-Pogonion (soft tissue) and Pogonion (soft tissue) - most prominent lip point. The normal mean for the Z angle is 10 degrees with a standard deviation of 4 degrees (26).

Figure 1. Determination of the H and Z angles.

The H angle measures the prominence of the lips in relation to the facial line. The Z angle measures the prominence of the lips or the relative retrusiveness of the chin and is formed by the intersection of the lines nasion (soft tissue) - pogonion (soft tissue) and pogonion (soft tissue) - most prominent lip point.

Taking into account frequent reports of hypodontia in patients with OI, to evaluate the caries prevalence in this population a modification of the DFT (decayed and filled teeth) index was utilized. Caries scores were adjusted for the missing teeth, by dividing the total sum of decayed and filled teeth by the total number of teeth present in an individual. Therefore, this adjusted DFT is a continuous variable ranging from 0 to 1, with 0 being the minimum caries experience and 1 being the highest (27).

The severity of malocclusion was assessed by two orthodontists. Mild malocclusion was diagnosed by normal facial features and projection, a normal functional occlusal table and an arrangement of teeth that included at most mild crowding, absence of crossbite, as well as normal antero posterior molar and canine relationships. A moderate malocclusion was defined by slight facial features alterations such as mild prognathism, and a dental occlusion that was deemed functional, with more than mild crowding. Severe malocclusion was determined by altered facial features with regard to profile or proportions, severe crowding and altered functional occlusion such as crossbite, openbite and lack of a minimum of occlusal contacts. Crowding was determined by two experienced orthodontists. It teeth were well aligned on the dental arch without rotation or overlap, absence of crowding was noted. If the teeth were either rotated or overlapping and less than 3 mm of space was necessary to correct the rotations or overlap, mild crowding was determined. If the space required was between 3 mm and 6 mm per arch, moderate crowding was identified and if a space of more than 6 mm was identified, then severe crowding was determined (28).

Results

Fourteen study participants with OI type V underwent dental evaluation (Table 1). Panoramic radiographs were obtained in 9 study participants. None of the individuals had clinical or radiological signs of DI. Tooth discoloration, pulp obliteration, bulbous crowns, short roots or taurodontism were not observed in this cohort. Six of the nine study participants (67%) for whom panoramic radiographs were obtained had at least one missing tooth. The number of missing teeth ranged from 1 to 9. Three of these 9 individuals had retained deciduous teeth past the normal range of exfoliation; eight study participants had impacted permanent teeth. The retained teeth were either located under unexfoliated primary teeth or just failed to erupt. The most frequent primary retained tooth type was the upper second molar. The teeth were not ectopically positioned but failed to erupt nonetheless. Ten study participants had an adjusted DFT score of 0, in four subjects the adjusted DFT score ranged from 0.21 to 0.67. Examples of the clinical and radiological features are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 1.

General clinical information and dental evaluation.

| Indi- vidual |

Sex | Age (yrs) |

Pan-orex | Agenesis of teeth | Retained primary teeth | Retention of permanent teeth | DFT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | f | 3 | no | not available | not applicable | not applicable | 0 |

| 2 | f | 4 | no | not available | not applicable | not applicable | 0 |

| 3 | f | 7 | no | not available | not applicable | not applicable | 0 |

| 4 | f | 8 | yes | 15, 25, 34, 44 | none | 12, 13, 14, 24 | 0.21 |

| 5 | m | 8 | no | not available | not applicable | not available | 0 |

| 6 | f | 11 | yes | 15, 24, 25, 31, 34, 35, 41, 44, 45 | 55, 73, 74, 83, 84 | 14 | 0 |

| 7 | f | 14 | yes | none | none | none | 0.58 |

| 8 | f | 14 | yes | none | none | 17 | 0 |

| 9 | f | 14 | yes | 14, 15, 24, 25, 34, 35, 41, 44, 45 | 75, 85 | 17, 27, 37, 47 | 0 |

| 10 | m | 14 | yes | none | none | 17, 27, 37, 46, 47 | 0 |

| 11 | f | 18 | yes | 38, 48 | none | 17 | 0 |

| 12 | f | 41 | yes | 15, 25, 34, 35, 45 | none | 27 | 0 |

| 13 | m | 47 | yes | 35 | none | 28, 38, 48 | 0.67 |

| 14 | m | 50 | no | not available | none | none | 0.40 |

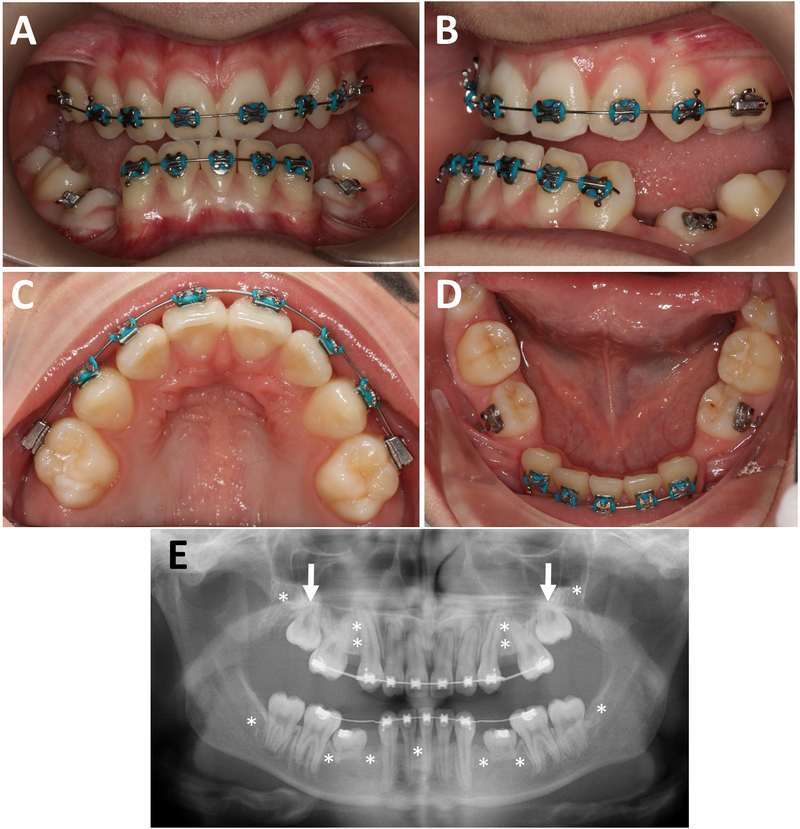

Figure 2.

Individual 9 (girl, 14 years). A, B. Intraoral photographs, showing posterior and anterior open bite and canine Class III but Class II molar malocclusion due to mesial drift of the upper molars in the edentulous space. C, D. Occlusal view, showing missing premolars and retained lower deciduous molars. E. Panoramic radiograph, showing the deciduous molars with resorbed roots, unerupted 2nd molar (arrows), a missing lower incisor and the position of the 8 missing premolars (asterisks). Third molars are also congenitally missing (asterisks).

Evaluation of occlusion revealed the presence of dental class II molar occlusion on at least one side in 8 of the 14 study participants (57%) (Table 2). Canine occlusion was class II on at least one side in 6 of the 12 individuals (50%) where it could be evaluated. Overjet ranged from −2 mm to +4 mm. Anterior crossbite was present in 7 (50%), posterior crossbite in 8 study participants (57%). Anterior open bite was observed in 6 (43%), lateral open bite in 5 individuals (36%). Six study participants (43%) presented with moderate dental crowding.

Table 2.

Occlusion data.

| Indi- vidual |

Molar occl right |

Molar occl left |

Canine occl right |

Canine occl left |

Severity of mal-occlusion | Over- jet (mm) |

Over- bite (%) |

Anterior cross-bite |

Posterior cross-bite |

Anterior open bite |

Lateral open bite |

Crow-ding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I | II | II | II | mild | 2 | 15 | y | y | n | y | mild |

| 2 | II | I | II | I | severe | 0 | openbite | y | y | y | y | n |

| 3 | I | I | I | I | mild | 1 | 0 | n | n | n | n | n |

| 4 | II | II | n/a | n/a | severe | −2 | openbite | y | y | y | n | mild |

| 5 | II | II | n/a | I | mild | 0 | openbite | y | n | y | n | mild |

| 6 | II | II | n/a | n/a | severe | 4 | 100 | n | y | n | n | n |

| 7 | I | I | I | I | mild | 2 | 10 | n | n | n | n | n |

| 8 | II | II | II | II | moderate | 0 | openbite | y | y | y | n | n |

| 9 | II | II | III | III | severe | −1 | 0 | y | y | y | y | n |

| 10 | II | II | II | II | severe | 6 | 40 | n | n | n | n | mild |

| 11 | I | I | I | I | n/a braces | 2 | 25 | n | n | n | n | n |

| 12 | I | I | I | I | moderate | 2 | 75 | n | n | n | n | moderate |

| 13 | I | III | I | II | severe | 0 | openbite | y | y | y | y | n |

| 14 | III | III | III | II | mild | 2 | 25 | n | y | n | y | mild |

Abbreviation: occl, occlusion

All study participants had normal ear position and no frontal bossing (Table 3). The facial profile was retrusive in 8 of the 14 study participants (57%). Assessment of facial proportions showed decreased lower face height in 8 individuals (57%), maxillary and mandibular dentoalveolar processes were underdeveloped in 50% of the participants.

Table 3.

Facial characteristics.

| Indi- vidual |

Face Type | Facial Profile | H line | Z angle | Facial Proportions | Lower face height (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | brachy | retrusive | 7.8 | 76.9 | normal | 46 |

| 2 | brachy | retrusive | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 3 | normo | normal | 19.1 | 70.4 | normal | 54 |

| 4 | normo | retrusive | 10.8 | 71.3 | decreased LFH | 45 |

| 5 | normo | normal | 24.5 | 59.3 | normal | 52 |

| 6 | brachy | retrusive | 24.7 | 56.8 | normal | 53 |

| 7 | brachy | retrusive | 3.7 | 78.3 | decreased LFH | 46 |

| 8 | normo | normal | 20.8 | 76.4 | normal | 50 |

| 9 | brachy | retrusive | 0.1 | 91.8 | decreased LFH | 47 |

| 10 | brachy | convex | 24.6 | 65.8 | decreased LFH | 43 |

| 11 | brachy | retrusive | 11.2 | 76.8 | normal | 50 |

| 12 | normo | retrusive | 1.4 | 86.6 | decreased LFH | 43 |

| 13 | normo | normal | 6.1 | 88.6 | normal | 47 |

| 14 | normo | normal | 9.3 | 99.9 | normal | 52 |

Abbreviations: LFH: lower face height; Normo: Normocephalic; Brachy: Brachycephalic

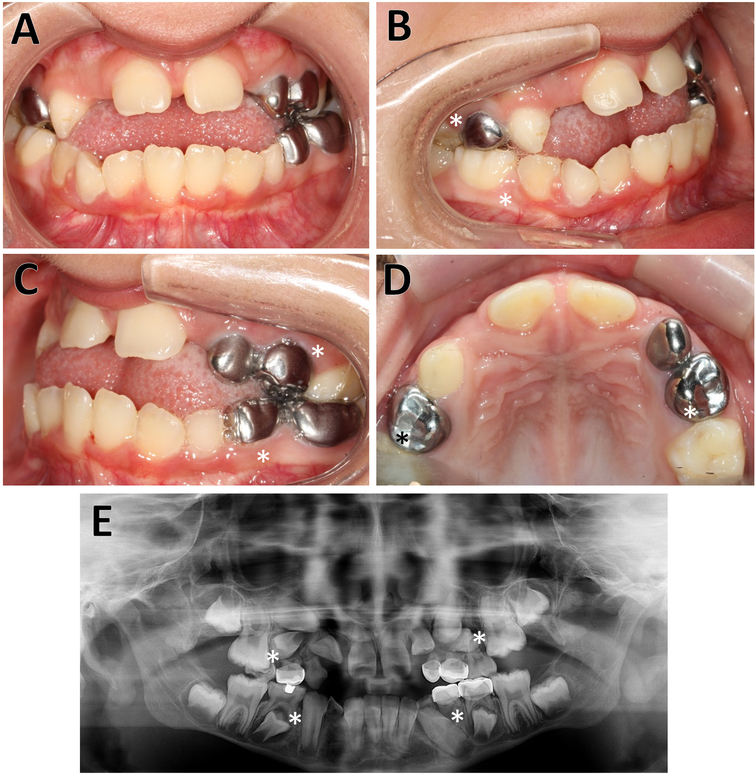

Cephalometry was performed in three study participants (Figure 3). Individual 9, a 14-year old girl, presented a severely retrusive maxilla and mandible, an underdeveloped lower face and severely retroclined upper and lower incisors. In contrast, individual 10, a 14-year old boy, had a protrusive maxilla and a retrusive mandible. Individual 13 presented with almost normal cephalometric results.

Figure 3.

Individual 4 (girl, 8 years). A, B, C Intra-oral photographs, showing the anterior open bite with Class II molar occlusion due to migration of upper permanent molars. The skeletal relationship is of a retrognathic maxilla. D. Occlusal plane view. E. The radiograph shows the agenesis of the premolars (15, 25, 44, 34) as well as multiple impactions (12, 13, 14, 24). Missing teeth are indicated by asterisks.

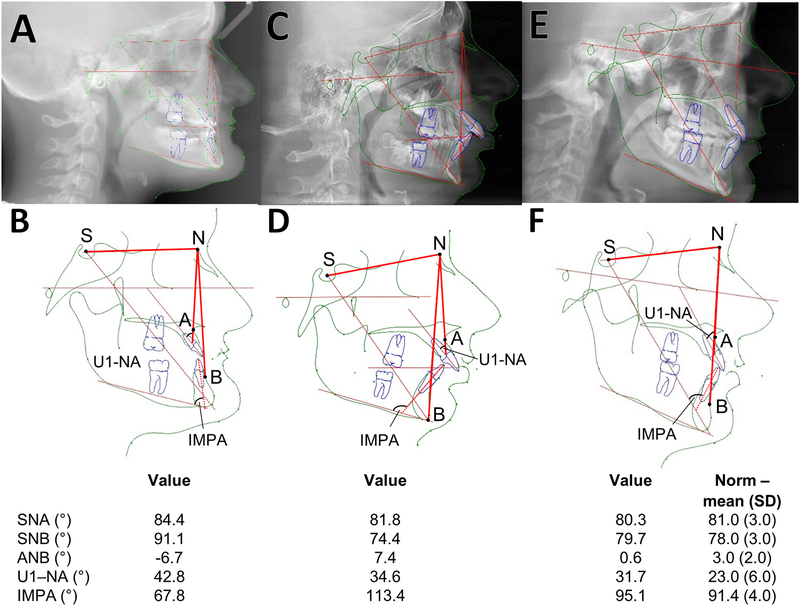

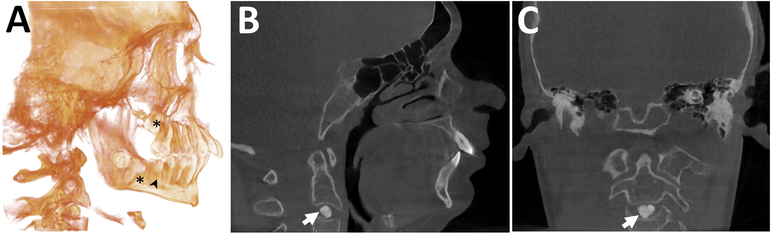

CBCT scans were obtained from two study participants. An impacted upper second molar and the absence of the lower third molars were detected in Individual 11 (not shown). In Individual 10, the CBCT scan demonstrated impacted second molars and semi impacted lower first molars. An intervertebral disc calcification at the C2–C3 level was also identified (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cephalograms A, B. Individual 9 (girl, 14 years). The maxilla and mandible are significantly retrognathic. The ANB angle (4.9 standard deviations [SD] below the reference mean value) and the Wits measurements (the length of the yellow lines on the occlusal plane; 3.1 SD above the reference mean value) are abnormal, indicating a Class III biretrusive skeletal malocclusion compensated by severely proclined upper incisors (as indicated by the elevated U1-NA angle) and severely retroclined lower incisors (reflected in the decreased incisor to mandibular plane angle, IMPA). There is also a severely brachycephalic facial type. C, D. Individual 10 (boy, 14 years). Cephalogram reconstructed from CBCT. The mandible is retrognathic. The maxilla-mandibular relationship is abnormal (the ANB angle is increased). All four second molars present with primary retention and are failing to erupt, the lower right first molar demonstrates secondary retention and has only erupted partially. Roots on the lower left first molar are shortened. Typical Class II division 1 malocclusion with a retrognathic mandible and a reduced lower face height. E, F. Individual 13 (47 year old male). Cephalometric measurements are within normal limits Definition of angles: SNA (Sella – Nasion - point A) measures the anteroposterior projection of the maxilla; SNB (Sella – Nasion - Point B) measures the anteroposterior projection of the mandible; ANB (Point A – Nasion - Point B): measures the relationship the maxilla in realtion to the mandible in the anteroposterior plane; U1-NA (upper incisor 1 – NA line): measures the angulation of the upper incisor in relation to the NA line; IMPA (lower incisor – mandibular plane angle): measures the angulation of the lower incisor in relation ot the mandibular plane angle

Discussion

In this largest oro-dental and craniofacial study on an OI type V population reported to date, we found that DI was absent but that missing teeth, especially premolars was a common occurrence. Malocclusion associated with either a retrusive maxilla or biretrusive jaws was also frequently observed. The facial type was either normal or brachycephalic and more than half of the individuals with OI type V presented with a retrusive (concave) profile and decreased lower face height due to underdeveloped maxillary and mandibular dentoalveolar processes.

The dental pattern of OI type V differs from that of OI types III and IV, as DI is absent and teeth are normally shaped. We observed multiple missing teeth in OI type V, especially involving the premolars, which is commonly seen also in OI types III and IV (4). The prevalence of permanent tooth retention seems to be lower in OI type V than in OI types III and IV and mainly involves the upper second molars which are not ectopically positioned but fail to erupt.

The absence of DI in OI type V has been reported in the first description of the disorder (10) and has also been noted in subsequent case series (16, 17, 29). This could be explained by the lack of a collagen type I defect in OI type V, as collagen type I is the major protein of intertubular dentin (90%) (30).

Previous reports have noted that missing teeth are a common finding in OI caused by COL1A1/COL1A2, affecting the permanent dentition in 10% to 22% of individuals (4, 31). Premolars appear to be most commonly affected (4). The present study suggests that premolars are also most frequently missing in OI type V. Tooth development is a complex process involving signaling pathways that are also important for skeletal development such as WNT signaling (32). It is therefore intuitive that genetic defects leading to major abnormalities in bone cell function also affect tooth development, but the precise pathways whereby variants in IFITM5 lead to tooth agenesis are unknown at present. For more mechanistic studies it would be interesting to assess the role of mutated IFITM5 in tooth development using mouse models of OI type V (13, 14).

Previous studies have shown a high prevalence of class III malocclusion in the more severe OI types related to collagen type I mutations (OI types III and IV) (31, 33, 34). These malocclusions are caused by a severely hypoplastic maxilla and the counterclockwise rotation of the mandible resulting in severe negative overjet. Cephalometric studies suggest that the relative mandibular prognathism in these OI types in part reflects the decreased anterior length of the maxilla associated to a counterclockwise rotation of the mandible during growth (35). Our findings indicate that skeletal Class III malocclusion is less frequent in OI type V and that Class II malocclusion either of skeletal or dento alveolar origin is more frequent in OI type V than in other forms of moderate to severe OI. The ANB angle which measures the projection of the maxilla to the manbible is often negative in OI types III and IV, indicating a skeletal Class III malocclusion. In OI type V, the ANB is either nil or positive, indicating a Class I or II malocclusion. However due to the missing teeth, especially the premolars, the Angle classification of occlusion is often not consistent. The assessment of the facial profile in OI type V also point to a marked difference in morphological appearace, as none of the present study participants had a prognathic mandible but rather a bimaxillary retrusion or a micrognathic mandible.

The severity of malocclusion varied widely in the present study independent of age. Six of the 14 study participants had severe malocclusion due to the presence of lateral open bite, multiple missing or retained teeth and tooth migration. This indicates that their malocclusions presented significant therapeutic challenges where conventional orthodontic approaches would likely be inadequate. Nevertheless, the present study cohort presented with less severe malocclusion than what is typically seen in OI types III and IV caused by variants in COL1A1 or COL1A2 (5).

Regarding facial characteristics, reduced lower face height and concave profile were more common in our study cohort, suggesting that the dentoalveolar processes do not develop normally but do not result in the severely prognathic profile that is often observed in individuals with OI type III and IV. Deficient dentoalveolar development may be due to missing teeth altering the growth or may be a direct effect of the IFITM5 variant.

In one of the two study participants who underwent CBCT scanning, we observed calcification of the intervertebral disk at the C2–C3 level. Calcification of intervertebral discs is a rare condition in children, which may present with neck pain, limited neck movement or may be discovered incidentally as in the present case. The cause of intervertebral disk calcification is unknown, but trauma and infection have been suggested as likely causes (36). Intervertebral disk calcification can lead to disc herniation, dysphagia or spinal cord compression (37), but can also resolve spontaneously (36). Thus, further follow-up of this individual will be important.

Even though this is the largest study on oro-dental and craniofacial aspects of OI type V until now, small sample size is an important limitation of this report. Incorporating more patients with OI type V will allow for more detailed observations. It will also be important for future studies to go beyond phenotypic description and assess treatment approaches to correct the significant craniofacial and dental abnormalities that are present in OI type V. As such treatments might involve orthognathic surgery and the placement of dental implants, more studies on the histopathology and material properties of OI type V bone would be valuable.

In conclusion, our study observed that OI type V is associated with missing teeth but not with DI. Facial analyses and cephalometric data show that OI type V is characterized by dentoalveolar alterations due to multiple missing teeth but not reversed overjet, as is frequently observed in other types of OI. The malocclusion phenotype of OI type V is either Class I biretrusive or Class II with a retrognathic mandible, and thus is markedly different from the phenotype of OI types III and IV.

Figure 5.

CBCT of Individual 10 (boy, 14 years). A. Three-dimensional volume rendering image. An increased severe maxillary prognatism and mandibular retrognatism, primary retention of second molars (*) and secondary retention of the lower right first molar (arrowhead) are present. B. Sagittal and C. Coronal images. There is a well-defined, round-shaped radiopaque entity within the disc space at the C2–C3 level, consistent with intervertebral disc calcification (arrow). The adjacent vertebral end plates appear normal.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jane Atkinson (National Institutes of Health) for helpful suggestions. This study was performed as an activity of the Brittle Bone Disease Consortium. The Brittle Bone Disease Consortium (1U54AR068069–0) is a National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), and is funded through a collaboration between the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), NCATS, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The study was also supported by the Shriners of North America. None of the authors declares a conflict of interest.

Members of the Brittle Bone Disease Consortium: Michael Bober6, Paul Esposito7, David R Eyre8, Danielle Gomez9, Gerald Harris10, Tracy Hart11, Mahim Jain2, Jeffrey Krisher12, Sandesh CS Nagamani2, Eric S Orwoll13, Cathleen L Raggio14, Eric Rush7, Peter Smith10, Laura Tosi15

6 Division of Medical Genetics, Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Delaware; 7 University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE; 8 Department of Orthopedic and Sports Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA; 9 Shriners Hospital for Children – Tampa, Tampa, FL; 10 Shriners Hospital for Children – Chicago, Chicago, IL; 11 Osteogenesis Imperfecta Foundation, Gaithersburg, MD; 12 Health Informatics Institute, Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL; 13 Department of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, OR; 14 Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY; 15 Bone Health Program, Children’s National Health System, Washington, DC, USA

References

- 1.Trejo P, Rauch F. Osteogenesis imperfecta in children and adolescents-new developments in diagnosis and treatment. Osteoporos Int 2016;27:3427–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forlino A, Marini JC. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Lancet 2016;387:1657–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson K, Dahllof G, Lindahl K, Kindmark A, Grigelioniene G, Astrom E, Malmgren B. Mutations in COL1A1 and COL1A2 and dental aberrations in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta - A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0176466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malmgren B, Andersson K, Lindahl K, Kindmark A, Grigelioniene G, Zachariadis V, Dahllof G, Astrom E. Tooth agenesis in osteogenesis imperfecta related to mutations in the collagen type I genes. Oral Dis 2017;23:42–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizkallah J, Schwartz S, Rauch F, Glorieux F, Vu DD, Muller K, Retrouvey JM. Evaluation of the severity of malocclusions in children affected by osteogenesis imperfecta with the peer assessment rating and discrepancy indexes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2013;143:336–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bardai G, Moffatt P, Glorieux FH, Rauch F. DNA sequence analysis in 598 individuals with a clinical diagnosis of osteogenesis imperfecta: diagnostic yield and mutation spectrum. Osteoporos Int 2016;27:3607–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semler O, Garbes L, Keupp K, Swan D, Zimmermann K, Becker J, Iden S, Wirth B, Eysel P, Koerber F, Schoenau E, Bohlander SK, Wollnik B, Netzer C. A mutation in the 5’-UTR of IFITM5 creates an in-frame start codon and causes autosomal-dominant osteogenesis imperfecta type V with hyperplastic callus. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91:349–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho TJ, Lee KE, Lee SK, Song SJ, Kim KJ, Jeon D, Lee G, Kim HN, Lee HR, Eom HH, Lee ZH, Kim OH, Park WY, Park SS, Ikegawa S, Yoo WJ, Choi IH, Kim JW. A single recurrent mutation in the 5’-UTR of IFITM5 causes osteogenesis imperfecta type V. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91:343–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moffatt P, Gaumond MH, Salois P, Sellin K, Bessette MC, Godin E, de Oliveira PT, Atkins GJ, Nanci A, Thomas G. Bril: a novel bone-specific modulator of mineralization. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23:1497–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glorieux FH, Rauch F, Plotkin H, Ward L, Travers R, Roughley P, Lalic L, Glorieux DF, Fassier F, Bishop NJ. Type V osteogenesis imperfecta: a new form of brittle bone disease. J Bone Miner Res 2000;15:1650–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeitlin L, Rauch F, Travers R, Munns C, Glorieux FH. The effect of cyclical intravenous pamidronate in children and adolescents with osteogenesis imperfecta Type V. Bone 2006;38:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung MS, Glorieux FH, Rauch F. Natural history of hyperplastic callus formation in osteogenesis imperfecta type V. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22:1181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lietman CD, Marom R, Munivez E, Bertin TK, Jiang MM, Chen Y, Dawson B, Weis MA, Eyre D, Lee B. A transgenic mouse model of OI type V supports a neomorphic mechanism of the IFITM5 mutation. J Bone Miner Res 2015;30:489–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rauch F, Geng Y, Lamplugh L, Hekmatnejad B, Gaumond MH, Penney J, Yamanaka Y, Moffatt P. Crispr-Cas9 engineered osteogenesis imperfecta type V leads to severe skeletal deformities and perinatal lethality in mice. Bone 2018;107:131–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blouin S, Fratzl-Zelman N, Glorieux FH, Roschger P, Klaushofer K, Marini JC, Rauch F. Bone matrix hypermineralization and increased osteocyte lacunae density in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta type V. J Bone Miner Res 2017;32:1884–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rauch F, Moffatt P, Cheung M, Roughley P, Lalic L, Lund AM, Ramirez N, Fahiminiya S, Majewski J, Glorieux FH. Osteogenesis imperfecta type V: marked phenotypic variability despite the presence of the IFITM5 c.−14C>T mutation in all patients. J Med Genet 2013;50:21–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim OH, Jin DK, Kosaki K, Kim JW, Cho SY, Yoo WJ, Choi IH, Nishimura G, Ikegawa S, Cho TJ. Osteogenesis imperfecta type V: clinical and radiographic manifestations in mutation confirmed patients. Am J Med Genet A 2013;161a:1972–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gugnani N, Pandit IK, Srivastava N, Gupta M, Sharma M. International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS): A New Concept. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2011;4:93–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobsen I, Kerekes K. Long-term prognosis of traumatized permanent anterior teeth showing calcifying processes in the pulp cavity. Scand J Dent Res 1977;85:588–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franco FC, de Araujo TM, Vogel CJ, Quintao CC. Brachycephalic, dolichocephalic and mesocephalic: Is it appropriate to describe the face using skull patterns? Dental Press J Orthod 2013;18:159–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nanda SK. Patterns of vertical growth in the face. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1988;93:103–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anic-Milosevic S, Lapter-Varga M, Slaj M. Analysis of the soft tissue facial profile by means of angular measurements. Eur J Orthod 2008;30:135–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobson A, Jacobson RL. Radiographic cephalometry: From basics to 3-D imaging, 2nd edition: Quintessence Publishing Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demirjian A, Goldstein H, Tanner JM. A new system of dental age assessment. Hum Biol 1973;45:211–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holdaway RA. A soft-tissue cephalometric analysis and its use in orthodontic treatment planning. Part I. Am J Orthod 1983;84:1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merrifield LL. The profile line as an aid in critically evaluating facial esthetics. Am J Orthod 1966;52:804–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ulseth JO, Hestnes A, Stovner LJ, Storhaug K. Dental caries and periodontitis in persons with Down syndrome. Special Care in Dentistry 1991;11:71–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Little RM. The irregularity index: a quantitative score of mandibular anterior alignment. Am J Orthod 1975;68:554–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brizola E, Mattos EP, Ferrari J, Freire PO, Germer R, Llerena JC Jr., Felix TM. Clinical and molecular characterization of osteogenesis imperfecta type V. Mol Syndromol 2015;6:164–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberg M, Kulkarni AB, Young M, Boskey A. Dentin: structure, composition and mineralization. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2011;3:711–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Connell AC, Marini JC. Evaluation of oral problems in an osteogenesis imperfecta population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1999;87:189–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Juuri E, Balic A. The biology underlying abnormalities of tooth number in humans. J Dent Res 2017;96:1248–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz S, Tsipouras P. Oral findings in osteogenesis imperfecta. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1984;57:161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang PC, Lin SY, Hsu KH. The craniofacial characteristics of osteogenesis imperfecta patients. Eur J Orthod 2007;29:232–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waltimo-Siren J, Kolkka M, Pynnonen S, Kuurila K, Kaitila I, Kovero O. Craniofacial features in osteogenesis imperfecta: a cephalometric study. Am J Med Genet A 2005;133:142–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dai LY, Ye H, Qian QR. The natural history of cervical disc calcification in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86-a:1467–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohanty S, Sutter B, Mokry M, Ascher PW. Herniation of calcified cervical intervertebral disk in children. Surg Neurol 1992;38:407–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]