Abstract

Puerariae radix (PR) is a traditional Chinese food and medicine. In this study, the chemical profile and bioactivities of PR fermented with Aspergillus niger (PFA) were investigated. Based on HPLC analysis, PFA chemical profile changed and total phenols increased by 12.5% relative to PR. Consequently, the in vitro antioxidant activity significantly improved. According to the blood lipid analysis in mice, PFA showed a better ability to inhibit the increased blood lipid levels induced by Triton WR-1339 than PR. In a quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) study, PFA up-regulated cholesterol 7-alpha hydroxylase (CYP7A1) and low-density lipoprotein receptor mRNA expression, which were 50% and 44.8% higher than the levels induced by high-dose PR. Conversely, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCoAR) mRNA expression was down-regulated to 46.8% lower than the levels induced by high-dose PR. The qRT-PCR results suggested that PFA displayed better hypolipidemic activity than PR, due to its superior ability to regulate mRNA expression.

Keywords: Antioxidant, Aspergillus niger, Hypolipidemic, Puerariae radix, Solid fermentation

Introduction

Currently, due to the growing demand for healthy and functional foods, edible and medicinal plants have attracted increasing attention. Pueraria lobata (Willd.) Ohwi (Leguminosae) is a plant with a long history in Asia. The roots of P. lobata are used as a superior animal feed, a natural health food and effective medicines in Asian countries (Xia et al., 2013). Many studies have revealed that Puerariae radix (PR) is rich in isoflavones and starch and can prevent and treat cardiovascular disease, decrease blood sugar and ameliorate menopausal syndrome (Wook et al., 2013; Xie et al., 2012). Hence, functional food development of PR is very promising.

Microbial fermentation has been used to make foods and drugs for thousands of years in China; this technique can enhance known therapeutic effects, decrease toxicity and produce additional functions (Xia and Yang, 2010). In modern industrial applications, this natural process can be used to produce desired products, such as pigments, antioxidants, and other molecules, in a controlled manner. These products are more popular among consumers than those produced by chemical synthesis (Couto and Sanromán, 2006). In particular, researchers have attempted to obtain new functions from traditional medicines or foods by microbial fermentation in recent years (Chen et al., 2013; Ni et al., 2015).

Aspergillus niger (A. niger) is an edible fungus used and distributed worldwide. It is generally regarded as safe by the United States Food and Drug Administration and is used for biotransformation, waste treatment and citric acid production (Bansal et al., 2012; Papagianni, 2007; Schuster et al., 2002). A. niger has been used for the biotransformation of many kinds of compounds, such as isoflavones, saponins, and steroids (Miyazawa et al., 2006; Parshikov et al., 2015). Hence, A. niger should be an appropriate strain to conduct solid fermentation in this study. During fermentation, A. niger produces various enzymes that are needed in plant fiber degradation, and this promotes the release of active compounds in PR. At the same time, starch and fiber in PR supply carbon source for A. niger growth.

The aim of this study was to add value to PR through solid fermentation. Recently, PR has been added to many types of functional foods, such as tea, wine and vinegar, via fermentation to improve their health characteristics (Zhang, 2013). To the best of our knowledge, there are limited reports about PR fermentation by A. niger. In addition, most existing studies have focused on flavors and production techniques, while bioactivities are rarely investigated (Chen and Zhao, 2015). PR possesses high antioxidant activity (Guerra et al., 2000; Yu et al., 2004), and is used with other medicines to treat hyperlipidemia (Liu et al., 2011; Xie et al., 2012). We focused on changes in the bioactivity of PR before and after solid fermentation with A. niger. Hence, we compared the antioxidant activity and hypolipidemic effect between unfermented PR and fermented PR in this work. This study will provide foundational data for further applications.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Glutathione (GSH) assay kit (No. 20150604), malondialdehyde (MDA) assay kit (No. 20150604), superoxide dismutase (SOD) kit (No. 20150604), catalase (CAT) assay kit (No. 20150604), total cholesterol (TC) assay kit (No. 20150522), triglyceride (TG) assay kit (No. 20150522), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) assay kit (No. 20150516), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) assay kit (No. 20150516) were obtained from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Co. (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). All chemicals and solvents were the highest commercially available grade.

Microorganism and materials

PR was purchased in the medicine market (Chengdu, Sichuan, China) and identified by Professor Zhang Hao (Sichuan University). Aspergillus niger CICC 40338 was provided by China Center of Industrial Culture Collection (CICC) and stored at − 20 °C before cultivating.

Preparation of cultures and solid-state fermentation

Freeze-dried spores of A. niger were recovered on potato dextrose agar medium for 5 days at 30 °C and then cultured in yeast extract peptone dextrose fluid medium at 160 rpm/min and 30 °C for 3 days.

Then, 25 g PR was mixed with 25 mL distilled water in a 250 mL flask. The substrate was autoclaved at 121 °C for 20 min, then stirred evenly and cooled down naturally. The sterilized PR was inoculated with 10% (v/w) prepared seed broth and statically cultured at 30 °C for 10 days. After 10 days, the fermentation products were dried at 50 °C for 24 h and ground by a mill to fine powder (100 mesh).

Contents of six principal isoflavones

First, samples were accurately weighted out to 1 g and extracted with 15 mL 70% ethanol water solution by ultrasonic extraction for 30 min. The extract was assayed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The remaining supernatant was diluted to five concentrations and stored at 4 °C for further analysis of antioxidant activities. Second, standard solutions of isoflavones at different concentrations were prepared. All solutions were filtered through a polytetrafluoroethylene filter (0.45 µm).

The HPLC analysis was performed on a liquid chromatograph system that consisted of a LC-10Atvp pump, a CTO-10Asvp column oven, a SCL-10Avp system controller, a SPD-10Avp detector and a Class-vp chromatographic work station (LC-10Atvp; Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). The chromatography column Kromasil C18 (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 µm, Akzo Nobel, Bohus, Sweden) was used for sample separation. The solvent flow condition was described in our previous study (Huang et al., 2017). Briefly, the mobile phase was composed of water (solvent A) and methanol (solvent B), with gradient elution as follows: 0–10 min, 25% B; 10–20 min, 25–30% B; 20–60 min, 30–100% B; 60–70 min, 100–25% B. The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min. The temperature of the column oven was set at 35 °C. The wavelength detector was set at 250 nm, and the injection volume of each sample was 5 µL. Contents are expressed as mg/g dry weight (mg/g DW).

Total phenolic contents (TPC) and antioxidant activities in vitro

The experimental procedures were described in our previous study (Huang et al., 2017). TPC is expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents per g of dry weight (mg GAE/g DW). The total antioxidant activity, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH) and hydroxyl (·OH) scavenging activities are both expressed as mg ascorbic acid equivalents/g of sample (mg AAE/g of sample). Moreover, ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) is expressed as mmol Fe2+/g of sample. Vitamin C was the positive control.

Hypolipidemic effect in mice

Eighty male Kunming mice (25–30 g) were obtained from Dashuo Experiment Animal Co. (Chengdu, Sichuan, China). Before the experiments, the mice were acclimatized under laboratory conditions for 1 week. The mice were housed in a controlled temperature (22 ± 1 °C) and relative humidity (40 ± 10%) with a reverse 12 h light/dark cycle. They were provided with standard food and water ad libitum. All the experiments with animals were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the institutional animal ethical committee (Number: SCU2016-1204). The samples were prepared as follows: PFA and PR were weighted out at 1 g and extracted with 15 mL 70% ethanol water solution by ultrasonic extraction for 30 min. The extracts were evaporated at 45 °C, lyophilized and then dissolved with 10 mL normal saline. Finally, the extracts were diluted with normal saline to 50 mg/mL (crude drug, low dose) and 100 mg/mL (crude drug, high dose).

The mice were randomly divided into nine groups, and each group included 10 mice. According to the method described by Chen and Li (2007), the mice were fasted for 12 h prior to initiation of the experiment. Triton WR-1339 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in normal saline to 30 mg/mL. All mice were injected with Triton WR-1339 or normal saline. Twelve hours after the injection, all mice were treated as shown in Table 1, and they sacrificed at 24 h after Triton WR-1339 injection. The serum and liver samples were collected and stored at − 70 °C for further analysis.

Table 1.

The groups information and administrations

| Group | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| Intraperitoneal injection | Oral administration | |

| Normal control | Normal saline | Normal saline |

| Model control | 300 mg/kg Triton WR-1339 | Normal saline |

| PFA-low | 300 mg/kg Triton WR-1339 | PFA 0.5 g/kg, b. w. |

| PFA-high | 300 mg/kg Triton WR-1339 | PFA 1 g/kg, b. w. |

| PR-low | 300 mg/kg Triton WR-1339 | PR 0.5 g/kg, b. w. |

| PR-high | 300 mg/kg Triton WR-1339 | PR 1 g/kg, b. w. |

| Lovastatin | 300 mg/kg Triton WR-1339 | lovastatin 10 mg/kg, b. w. |

| PFA-NS | Normal saline | PFA 1 g/kg, b. w. |

| PR-NS | Normal saline | PR 1 g/kg, b. w. |

The dosage was calculated with crude materials

PFA Puerariae radix fermented by Aspergillus niger; PR Puerariae radix; NS Normal saline; b. w. body weight

The serum lipid levels (TC, TG, HDL and LDL), GSH and MDA levels and SOD and CAT activities in the liver were detected by using commercial reagent kits purchased from the Institute of Biological Engineering of Nanjing Jiancheng (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) according to the instruction manuals.

RT-PCR

The mRNA expression of LDLR, CYP7A1, and HMGCoAR was determined from liver tissue. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (RR047A; Takara, Dalian, Liaoning, China). The mRNA expression levels of LDLR, CYP7A1, and HMGCoAR were evaluated by qRT-PCR analysis using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II Kit (RR820A; Takara, Dalian, Liaoning, China). qRT-PCR was performed on ThermoFisher PIKORed 96 system (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The primer sequences are listed in Table 2. Target mRNA expression in each sample was normalized to the housekeeping gene β-actin. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to calculate relative mRNA expression levels.

Table 2.

The sequences of the primers used for real-time PCR

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | 5′-GAAGATCAAGATCATTGCTCCT | 5′-TACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCA |

| CYP7A1 | 5′-GCCCTGAAGCAATGAAAGCAGCCTCT | 5′-GAGAGCCGCAGAGCCTCCTTGATGA |

| HMGCoAR | 5′-TGACGATGGCAGGACGCAACCTCTAT | 5′-CACCTTGGCTGGAATGACGGCTTCAC |

| LDLR | 5′-CCTGGAAGGCAGCTACAAGTGTGAGT | 5′-CGTGGCGGTTGGTGAAGAGCAGATAG |

Statistical analysis

The data obtained were analyzed by using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) V.19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistically significant differences among the groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by LSD tests and Dunnett’s tests. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Contents of isoflavones determined by HPLC

Isoflavones are important indicators used to evaluate the quality of PR. In this work, several representative isoflavones were chosen to reflect the contents of isoflavones in the samples. We found that the species and contents of the PR compounds were changed after fermentation. These changes may alter the bioactivities of PR. Glycosides, such as daidzin, were hydrolyzed to the corresponding aglycones. However, most of the principal compounds in PR, such as puerarin, were reserved after fermentation. The results agreed with the report of Choi and Ji (2005) showing that O-glycoside but not C-glycoside isoflavones in PR are effectively hydrolyzed by microorganisms. Puerarin represents C-glycoside isoflavones and daidzin represents O-glycoside ones. As shown in Table 3, the total contents of the major isoflavones in PFA showed a slight increase compared with those in unfermented PR (p < 0.05). The increases in the contents of puerarin and 3′-OH puerarin were probably due to the decrease of mirificin and 3′-OCH3 puerarin and the consumption of non-isoflavones (including protein, carbohydrate). However, glycoside compounds such as daidzin strongly decreased from 7.31 ± 0.22 mg/g DW to 0.31 ± 0 mg/g DW, and homologous aglycones such as daidzein increased from 0.66 ± 0.03 mg/g DW to 7.23 ± 0.09 mg/g DW. The results were consistent with those of previous studies (Lee et al., 2015; Raimondi et al., 2009). In addition, aglycones have higher antioxidant activity and better absorption by the human intestinal tract than isoflavone glucosides, owing to their better lipid solubility (Chi and Cho 2016; Marazza et al., 2012). Hence, fermentation by A. niger may enhance PR bioactivities. In addition, the molecular weight of compounds such as daidzin (416), which was hydrolyzed to daidzein, was much higher than that of daidzein (254). If all daidzin was transformed to daidzein, the content of daidzein in PFA should be 4.46 mg/g DW. In fact, the total daidzein content was 7.23 mg/g DW in PFA. Therefore, the moles of isoflavones in unit weight increased. This increase will enhance the bioactivities of PR. The extra daidzein content may be due to other glucosides with the same aglycones as daidzin or certain precursors.

Table 3.

The contents of main isoflavones of samples

| Isoflavones | Contents (mg/g DW) | |

|---|---|---|

| PFA | PR | |

| 3′-OH puerarin | 3.58 ± 0.10a | 3.35 ± 0.12b |

| Puerarin | 39.38 ± 1.03a | 36.32 ± 0.67b |

| Mirificin | 6.75 ± 0.01a | 8.31 ± 0.51b |

| 3′-OCH3 puerarin | 6.85 ± 0.09a | 7.40 ± 0.35b |

| Daidzin | 0.31 ± 0a | 7.31 ± 0.22b |

| Daidzein | 7.23 ± 0.09a | 0.66 ± 0.03b |

| Total | 64.1 ± 0.57a | 63.35 ± 0.18b |

The data is expressed as mean ± SD, n = 6

DW dry weight of sample; PFA Puerariae radix fermented by Aspergillus niger; PR Puerariae radix

Values with the different letters were significantly different at the level of 0.05

Contents of total phenolics

Studies have demonstrated the high correlation between TPC and antioxidant activity (Paixão et al., 2007). Hence, determination of TPC is necessary. In this study, the TPC of samples was detected with the Folin-Ciocalteu method and is expressed as gallic acid equivalents (mg GAE/g DW). The data showed that the phenolic contents increased from 44.39 ± 0.02 mg GAE/g DW (unfermented PR) to 49.95 ± 0.04 mg GAE/g DW (PFA). Some reports have suggested that substances used as Chinese medicines may be concentrated during microorganism growth, due to the consumption of proteins, carbohydrates and other nutrients (Chandrasekara and Shahidi, 2012).

Antioxidant capacity

Several antioxidant capacity assays with different mechanisms were performed to measure the antioxidant capacities of the samples, and the results are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Antioxidant activities of PFA and PR in vitro

| Samples | Total antioxidant activity (mg AAE/g of sample) | DPPH (mg AAE/g of sample) | ·OH (mg AAE/g of sample) | FRAP (mmol Fe2+/g of sample) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFA | 24.327 ± 2.310a | 12.739 ± 0.652a | 256.215 ± 12.134a | 0.112 ± 0.063a |

| PR | 19.415 ± 0.521b | 10.576 ± 0.517b | 133.433 ± 11.369b | 0.110 ± 0.037a |

The data is expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 6

AAE ascorbic acid equivalents; PFA Puerariae radix fermented by Aspergillus niger; PR Puerariae radix

Values with the different letters were significantly different at the level of 0.05

In the total antioxidant activity assay, the activity of PFA was over 25% superior to that of PR. Similarly, PFA extracts exhibited stronger DPPH scavenging activity and hydroxyl radical scavenging activity than PR. These antioxidant activities increased by 20.4% and 92.0% after fermentation, respectively. However, the FRAP of PFA showed no significant difference from that of PR (p > 0.05).

Although different analysis methods have different reaction mechanisms, the results above indicated that solid fermentation with A. niger enhanced the antioxidant activities of PR. The results have three possible explanations. First, daidzein has higher antioxidant activity than daidzin (Chen et al., 2011). Second, the antioxidant activity of 3′-OH puerarin is 20 times higher than that of puerarin, and thus, increased 3′-OH puerarin can enhance PR antioxidant activity (Ye et al., 2007). Finally, the contents of isoflavones and phenols, which are the major antioxidant ingredients in PR, were increased by solid fermentation. These findings are consistent with the observations by Dulf et al. (2017).

Hypolipidemic activity

Injection of Triton WR-1339 induces acute hyperlipidemia. This procedure is a fast and convenient method to screen potential hypolipidemic drugs. PR is a traditional Chinese medicine, that is used with other herbs to treat hyperlipidemia (Xie et al., 2012). Thus, we explored the hypolipidemic effect of PFA, which may perform better than PR, as shown in the previous in vitro studies.

In this study, blood lipid levels and related enzyme activities were assessed, and the results are displayed in Table 5. After the injection of Triton WR-1339, the TC, TG and LDL levels in serum of the model group were significantly increased (p < 0.01), and the HDL level was slightly decreased compared with that of the normal group (p < 0.05). These findings indicated that the acute hyperlipidemia model was successfully established. As shown in Table 5, PFA and PR treatments reduced the changes in blood lipid parameters induced by Triton WR-1339. Specifically, TC, TG and LDL levels in the PFA- and PR-treated groups were significantly reduced, and HDL levels were enhanced relative to those in the model group (p < 0.05). Both PFA and PR improved blood lipid parameters in a dose-dependent manner in hyperlipidemic mice. Furthermore, PFA was better at regulating blood lipid levels than PR at a high dose, especially for TC (15.9% lower than PR) and TG (10.8% lower than PR). Both PFA and PR are quite safe at high doses.

Table 5.

Results of different groups on blood lipid levels and antioxidant parameters of liver

| Group | TC (mmol/L) | TG (mmol/L) | HDL (mmol/L) | LDL (mmol/L) | SOD (U/mg protein) | CAT (U/mg protein) | GSH (μmol/g protein) | MDA (μmol/g protein) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal control | 4.22 ± 0.30a | 2.34 ± 0.05a | 1.41 ± 0.02a | 0.46 ± 0.01a | 127.6 ± 8.2a | 17.2 ± 0.5a | 22.1 ± 0.2a | 1.8 ± 0.6a |

| Model control | 6.20 ± 0.45b | 3.18 ± 0.12b | 1.22 ± 0.07b | 0.95 ± 0.06b | 83.2 ± 5.4b | 13.6 ± 0.4b | 7.2 ± 0.8b | 3.2 ± 0.3b |

| PFA-low | 4.51 ± 0.53a | 2.05 ± 0.11a | 1.35 ± 0.05b | 0.76 ± 0.03c | 113.1 ± 6.5c | 15.5 ± 0.3c | 12.5 ± 0.4c | 3.0 ± 0.2b |

| PFA-high | 3.96 ± 0.21a | 1.74 ± 0.06c | 1.37 ± 0.04c | 0.57 ± 0.03c | 119.3 ± 7.6a | 16.5 ± 0.2a | 17.6 ± 1.0c | 2.4 ± 0.2a |

| PR-low | 4.80 ± 0.33a | 2.25 ± 0.22a | 1.30 ± 0.04b | 0.73 ± 0.10c | 103.0 ± 4.2c | 15.1 ± 0.4c | 12.7 ± 0.8c | 2.8 ± 0.1b |

| PR-high | 4.71 ± 0.22a | 1.95 ± 0.16a | 1.34 ± 0.02c | 0.60 ± 0.02c | 114.2 ± 6.7a | 16.4 ± 0.3a | 15.2 ± 0.2c | 2.7 ± 0.2b |

| Lovastatin | 4.31 ± 0.32a | 1.98 ± 0.20a | 1.27 ± 0.01b | 0.52 ± 0.01c | 107.2 ± 8.2c | 15.4 ± 0.5c | 15.2 ± 0.5c | 2.4 ± 0.3c |

| PFA-NS | 3.94 ± 0.17a | 1.82 ± 0.11c | 1.45 ± 0.12a | 0.46 ± 0.03a | 128.5 ± 5.5a | 17.5 ± 0.6a | 23.3 ± 0.6a | 2.3 ± 0.1a |

| PR-NS | 4.07 ± 0.52a | 1.75 ± 0.21c | 1.41 ± 0.08a | 0.43 ± 0.04a | 127.7 ± 8.3a | 18.3 ± 0.8a | 22.4 ± 0.5a | 2.3 ± 0.2a |

The data is expressed as mean ± SD, n = 6

PFA Puerariae radix fermented by Aspergillus niger; PR Puerariae radix; NS Normal saline

Values with the different letters were significantly different at the level of 0.05, compared with normal and model group

Hyperlipidemia results in dysfunction between oxidation and antioxidation. Hence, many oxygen free radicals and high levels of MDA will be produced. These changes induce cardiac-cerebral vascular disease, liver damage and aging (Shao et al., 2016). The SOD and CAT activities indicate the ability to scavenge oxygen free radicals. The GSH and MDA contents reflect the current degree of lipid peroxidation. In this work, injection of Triton WR-1339 strongly attenuated SOD and CAT activities in model group (p < 0.01). In addition, the GSH content decreased, and the MDA content increased (p < 0.01, p < 0.01). In the PFA-treated groups, the decreased SOD and CAT activities and GSH level were partly recovered, and the elevated MDA level was slightly decreased, similar to the PR-treated groups. Hence, treatments with PFA and PR reduced lipid peroxidation and enhanced the activities of antioxidant enzymes at both low and high doses. In addition, PFA at a high dose is more effective at increasing GSH and decreasing MDA levels than PR (p < 0.01, p < 0.05). Hence, PFA is a better choice than PR to alleviate lipid peroxidation induced by hyperlipidemia.

The antihyperlipidemia results were consistent with the antioxidant results in vitro. PFA exhibited superior antihyperlipidemic activity relative to PR. There may be three explanations for the results. First, oxidative stress plays a major role in endothelial damage and atherosclerosis. Oxidants can oxygenate LDL to oxidized LDL and aggravate the accumulation of cholesterol. Hence, antioxidant activity plays an important role in the hypolipidemic effect. PFA has higher antioxidant activity than PR, as observed in a previous in vitro study. Second, the major bioactive ingredients in PFA, similar to those in PR, are isoflavones. In addition, isoflavones in PR have been shown to have hypolipidemic effects (Park et al., 2009; Wook et al., 2013). The contents of isoflavones and phenols per gram of PFA were higher than those in PR. Third, the ratio of aglycones in PFA was higher than that in PR. Aglycones have better lipid solubility than glycosides (Lee et al., 2015; Marazza et al., 2012). Hence, more aglycones than glycosides will be absorbed from the intestinal tract into the blood circulation. Therefore, PFA has stronger hypolipidemic effects.

RT-PCR

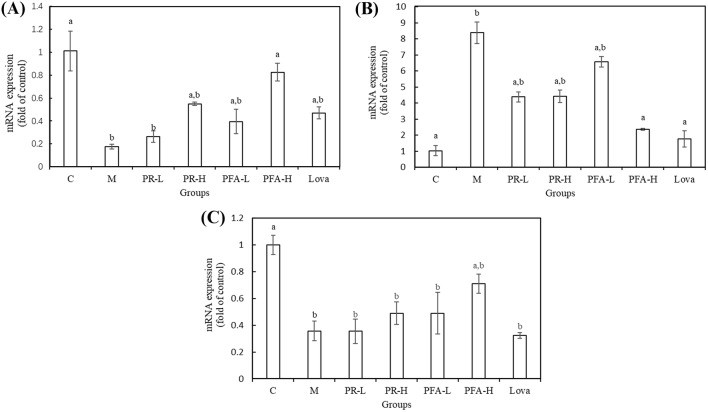

In order to search the possible mechanism of PFA and PR in hyperlipidemic activity, a qRT-PCR study was done in mice liver. The CYP7A1 enzyme converts cholesterol into 7-hydroxycholesterol, which is an important step in the bile acid biosynthesis pathway in the liver (Russell, 2003). Hence, the higher expression of CYP7A1 mRNA leads to faster consumption of cholesterol. In addition, the plasma cholesterol concentration is regulated mainly by the LDL receptor pathway, in which circulating LDL is taken into cells by receptor-mediated endocytosis (Brown and Goldstein, 1986). Moreover, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaric acid (HMGA) is a competitive inhibitor of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCoAR) and strongly reduces cholesterol biosynthesis both in vitro and in vivo. As is known to all, lovastatin is the first approved inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase in the world, so it was chosen as the positive control in the study (Padova et al., 1982; Tobert, 2003). As shown in Fig. 1, the expression of CYP7A1 mRNA and LDLR mRNA was restrained by Triton WR-1339. Compared with the model group, treatment with PR and PFA up-regulated mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner, especially in the PFA-H groups (p < 0.01). On the other hand, high-dose PFA and lovastatin significantly inhibited the expression of HMGCoAR mRNA (p < 0.01, p < 0.01). Hence, PFA showed better performance than PR in regulating the expression of lipid metabolism-related mRNA. It is the further evidence that PFA has better hyperlipidemic activity than PR.

Fig. 1.

Effects of Puerariae radix fermented by Aspergillus niger (PFA) and Puerariae radix (PR) on mRNA expression in the mouse liver. (A) Cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase (CYP7A1), (B) 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGCoAR), and (C) low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR). Each value is expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). ap < 0.05 versus model control, bp < 0.05 versus normal control. C: normal control; M: model control; PR-L: PR treatment at 0.5 g/kg; PR-H: PR treatment at 1 g/kg; PFA-L: PFA treatment at 0.5 g/kg; PFA-H: PFA treatment at 1 g/kg; Lova: lovastatin treatment at 10 mg/kg

In conclusion, microbial solid fermentation is a commercial and effective method to alter the functions of crude plant medicines. In our study, Aspergillus niger CICC 40338 could change the ingredients of PR and improve its antioxidant activity in vitro and its hypolipidemic effect in vivo. PFA is a promising functional food that has anti-aging, antioxidant and antihyperlipidemia effects.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by Sichuan Science and Technology Support Program (No. 2014S20131).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bansal N, Tewari R, Soni R, Soni SK. Production of cellulases from Aspergillus niger ns-2 in solid state fermentation on agricultural and kitchen waste residues. Waste Manage. 2012;32:1341–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1986;232:34–47. doi: 10.1126/science.3513311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekara A, Shahidi F. Bioaccessibility and antioxidant potential of millet grain phenolics as affected by simulated in vitro digestion and microbial fermentation. J. Funct. Foods. 2012;4:226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2011.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Fu YJ, Zu YG, Wang W, Mu FS, Luo M, Li CY, Gu CB, Zhao CJ. Biotransformation of saponins to astragaloside IV from Radix Astragali by immobilized Aspergillus niger. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2013;2:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2013.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Li X. Hypolipidemic effect of flavonoids from mulberry leaves in triton wr-1339 induced hyperlipidemic mice. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007;16:290–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Wang Y, Zeng H, Yuan Y, Zhou Y. Screening and identification of antioxidant components in the extract of Puerariae radix, using HPLC coupled with MS. Food Anal. Method. 2011;4:373–380. doi: 10.1007/s12161-010-9180-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YX, Zhao HY. The puerarin production process with Aspergillus niger. Farm Products Processing. 2015;10:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chi CH, Cho SJ. Improvement of bioactivity of soybean meal by solid-state fermentation with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens versus Lactobacillus spp. and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016;68:619–625. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi EK, Ji GE. Food microorganisms that effectively hydrolyze O-glycoside but not C-glycoside isoflavones in Puerariae Radix. J. Food Sci. 2005;70:25–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb09970.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Couto SR, Sanromán MA. Application of solid-state fermentation to food industry—A review. J. Food Eng. 2006;76:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dulf FV, Dan CV, Dulf EH, Pintea A. Phenolic compounds, flavonoids, lipids and antioxidant potential of apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) pomace fermented by two filamentous fungal strains in solid state system. Chem. Cent. J. 2017;11:92. doi: 10.1186/s13065-017-0323-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra MC, Speroni E, Broccoli M, Cangini M, Pasini P, Minghetti A, Crespi-Perellino N, Mirasoli M, Cantelli-Forti G, Paolini M. Comparison between Chinese medical herb Pueraria lobata crude extract and its main isoflavone puerarin: antioxidant properties and effects on rat liver CYP-catalysed drug metabolism. Life Sci. 2000;67:2997–3006. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(00)00885-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Zhang H, Xue D. Enhancement of antioxidant activity of Radix Puerariae and red yeast rice by mixed fermentation with Monascus purpureus. Food Chem. 2017;226:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Hong GE, Zhang H, Yang YC, Han KH, Mandal PK, Lee CH. Production of the isoflavone aglycone and antioxidant activities in black soymilk using fermentation with Streptococcus thermophilus S1. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2015;24:537–544. doi: 10.1007/s10068-015-0070-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CM, Ma JQ, Sun YZ. Protective role of puerarin on lead-induced alterations of the hepatic glutathione antioxidant system and hyperlipidemia in rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011;49:3119–3127. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marazza JA, Nazareno MA, Giori GS, Garro MS. Enhancement of the antioxidant capacity of soymilk by fermentation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus. J. Funct. Foods. 2012;4:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2012.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa M, Takahashi K, Araki H. Biotransformation of isoflavones by Aspergillus niger, as biocatalyst. J. Chem. Technol. Biot. 2006;81:674–678. doi: 10.1002/jctb.1461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ni H, Chen F, Jiang ZD, Cai MY, Yang YF, Xiao AF, Cai NH. Biotransformation of tea catechins using Aspergillus niger, tannase prepared by solid state fermentation on tea byproduct. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2015;60:1206–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padova CD, Bosisio E, Cighetti G, Rovagnati P, Mazzocchi M. 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaric acid (HMGA) reduces dietary cholesterol induction of saturated bile in hamster. Life Sci. 1982;30:1907–1914. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90471-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paixão N, Perestrelo R, Marques JC, Câmara JS. Relationship between antioxidant capacity and total phenolic content of red rosé and white wines. Food Chem. 2007;105:204–214. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papagianni M. Advances in citric acid fermentation by Aspergillus niger: biochemical aspects, membrane transport and modeling. Biotechnol Adv. 2007;25:244–263. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park GJ, Park LBR, Park SJ, Kim JD. Effects of puerariae flos on antioxidative activities and lipid levels in hyperlipidemic sprague-dawley rats. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutri. 2009;38:846–851. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2009.38.7.846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parshikov IA, Woodling KA, Sutherland JB. Biotransformations of organic compounds mediated by cultures of Aspergillus niger. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2015;99:6971–6986. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6765-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raimondi S, Roncaglia L, De Lucia M, Amaretti A, Leonardi A, Pagnoni UM, Rossi M. Bioconversion of soy isoflavones daidzin and daidzein by Bifidobacterium strains. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2009;81:943–950. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1719-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW. The enzymes, regulation, and genetics of bile acid synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:137–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster E, Dunn-Coleman N, Frisvad JC, Van Dijck PW. On the safety of Aspergillus niger - a review. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2002;59:426–435. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao F, Gu LF, Chen HJ, Liu RH, Huang HL, Ren G. Comparation of hypolipidemic and antioxidant effects of aqueous and ethanol extracts of Crataegus pinnatifida fruit in high-fat emulsion-induced hyperlipidemia rats. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2016;12:64–69. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.176049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobert JA. Lovastatin and beyond: the history of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2:517–526. doi: 10.1038/nrd1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wook LD, Goo KJ, Tai KY. Effects of dietary isoflavones from puerariae radix on lipid and bone metabolism in ovariectomized rats. Nutrients. 2013;5:2734–2746. doi: 10.3390/nu5072734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia DZ, Zhang PH, Fu Y, Yu WF, Ju MT. Hepatoprotective activity of puerarin against carbon tetrachloride-induced injuries in rats: a randomized controlled trial. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013;59:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia T, Yang P. The bi-directional fermentation technology, a new approach to attenuating the toxicity of toxic chinese materia medica. Journal of Fungal Research. 2010;8:52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Xie WD, Zhao YN, Du LJ. Emerging approaches of traditional Chinese medicine formulas for the treatment of hyperlipidemia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140:345–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye H, Yuan S, Cong XD. Biotransformation of puerarin into 3′-hydroxypuerarin by Trichoderma harzianum NJ01. Enzyme Microb. Tech. 2007;40:594–597. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2006.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Zhao Y, Shu B. The radical scavenging activities of radix puerariae isoflavonoids: a chemiluminescence study. Food Chem. 2004;86:525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2003.08.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. Develop of compound puerariae radix health tea. Food and Machinery. 2013;29:238–241. [Google Scholar]