Abstract

A new fluorescent probe made from (E)-2-(benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-3-(6-hydroxynaphthalen-2-yl) acrylonitrile (Probe 1) was synthesized for the determination of bisulfite concentrations in real food samples (red wine and sugar). Adding bisulfite to a Probe 1 solution caused a marked decrease in fluorescence intensity and a visual color change from yellow to light yellow. This distinct color response indicates that Probe 1 could be used as a visual sensor for bisulfite. Probe 1 can detect bisulfite quantitatively in the range 0–400 μM with a detection limit of 0.10 μM. This makes Probe 1 a convenient signaling instrument for determining bisulfite levels in sugar and red wine samples.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10068-019-00571-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Fluorescent probe, Bisulfite, Sugar, Red wine

Introduction

Bisulfite (HSO3−) is commonly used in the food, drug, and beverage industries because it acts as an antibiotic, antioxidant, and antimicrobial enzyme (McFeeters, 1998; Sun et al., 2014a). However, chronic exposure to excessive levels of HSO3− causes harm to biomacromolecules, cells, and tissue, and can cause allergic reactions and asthmatic attacks in some individuals (Wang et al., 2017). Because of its harm to human health, the threshold levels of bisulfite in medicine and food are severely limited in most countries (Yilmaz and Somer, 2007). For example, in China, the level of sulfur (calculated by SO2) in red wine is strictly controlled at < 0.25 g/kg and at < 0.1 g/kg in white granulated sugar (Wang et al., 2017). Therefore, the detection and limitation of bisulfite in food are essential to human health. Accordingly, there is a need for a fluorescent probe that can selectively and sensitively detect bisulfite in food.

To date, several methods have been developed to determine HSO3− content, such as chromatography (McFeeters and Barish, 2003), titration, capillary electrophoresis, electrochemistry (Daunoravicius and Padarauskas, 2002; Lu et al., 2006) and spectrophotometry (Hassan et al., 2006). These methods have been used to determine bisulfite content in fruit, wine, starches, beverages, beer, and sugar. However, most of these methods rely on high-cost apparatus and multiple reagents, and their pre-treatment processes require substantial amounts of time. Fluorescent probes have become a promising tool for the sensing and monitoring of bisulfite content due to their rapid response, simplicity, real-time detection ability, high sensitivity, and selectivity (Ding et al., 2015; Ding et al., 2016). Over the years, more fluorescent probes for bisulfite have been developed by nucleophilic reaction with aldehyde (Liu et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2012), C=C double bond (Sun et al., 2017) and levulinate (Chen et al., 2012; Choi et al., 2010; Gu et al., 2011), coordination to metal ions (He et al., 2014; Yuan et al., 2013), complexation with amines (Leontiev and Rudkevich, 2005; Sun et al., 2009), and Michael-type additions (Li, 2015; Peng et al., 2014; Santos-Figueroa et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2014a; Tan et al., 2014; Tian et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014; Ye et al., 2018). Although many small molecule fluorescent probes have been applied to bisulfite detection, further study is urgently needed to develop efficient and practical sensors that can detect bisulfite in food. In our previous study, a new fluorescent probe was synthesized to detect bisulfite selectively relying on Michael-type additions and was applied as a testing tool to determine bisulfite levels in sugar (Wang et al., 2017). In order to find a more responsive and visible colorimetric fluorescent probe, a new probe based on (E)-2-(benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-3-(6-hydroxynaphthalen-2-yl) acrylonitrile (Probe 1) is introduced in this work. The fluorophore of probe 1 is a naphthalene ring moiety and the reaction sites are unsaturated C=C double bonds for bisulfite. The probe shows high sensitivity and selectivity for HSO3− and could be used to monitor bisulfite levels in food (red wine and sugar) with high recovery.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

6-Hydroxy-2-naphthaldehyde (99%), homocysteine(Hcy, 99%), piperidine (99%), cysteine (Cys, 99%), glutathione (GSH, 99%), 2-benzothiazoleacetonitrile (98%) were gotten from Bailing Wei (Beijing, P. R. China). Analytes sodium acetate trihydrate (CH3COONa), sodium chloride (NaCl), sodium thiocyanate (NaSCN), fluoride (NaF), ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), sodium bromide (NaBr), sodium sulfite (Na2SO3), potassium iodide (KI),sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), sodium nitrate (NaNO3), sodium nitrite (NaNO2), sodium hydrogen sulfite (NaHSO3), calcium chloride (CaCl2), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), ethanol (CH3CH2OH) and methanol (CH3OH) were HPLC grade bought from Banxia Company.

Instruments

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were gotten on a Bulu Ke AV 600 MHz NMR and TMS was used as internal standard. The high-resolution mass spectrum (HRMS) was carried out at a Bulu Ke Apex IV FTMS. Fluorescence spectra were observed, recorded on a Ri Li F-4600 fluorescence spectrometer. UV–Vis spectra was taken down on a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrometer.

Preparation of Probe 1

6-Hydroxy-2-naphthaldehyde (1, 1.72 g, 0.01 mol) and 2-benzothiazoleacetonitrile (2, 1.74 g, 0.01 mol) were dissolved in methanol (25 mL) with piperidine (0.10 g, 0.012 mol). The reaction mixture was refluxed for 3 h. The methanol was distilled off and the product was washed with methanol. The crude product was crystallized again, to give pure (E)-2-(benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-3-(6-hydroxynaphthalen-2-yl) acrylonitrile (probe 1, 2.53 g).

Preparation of analytes and Probe 1

Probe 1 stock solution (1 mM) was dissolved with DMSO. Analytes Cys, GSH, Hcy, CH3COONa, NaSCN, NH4Cl, Na2CO3, NaBr, NaHCO3, Na2SO3, NaF, Na2SO4, KI, NaNO3, NaNO2, NaCl, NaHSO3, CaCl2 were prepared by distilled water to obtain 10 mM aqueous solution (Ye et al., 2018). Distilled water was used to dilute the stock solution and were used at once.

Preparation of sugar and red wine

Sugar and red wine were random purchased from wumei market (Beijing), sugar were dissolved in deionized water (Wang et al., 2017). Crystal sugar (carbohydrate 99.2 g/100 g), granulated sugar (carbohydrate 92.2 g/100 g), soft sugar (carbohydrate 98.9 g/100 g); red wine A (alcohol content, 12%; type, dry), red wine B (alcohol content, 13%; type, dry), red wine C (alcohol content, 12.5%; type, dry). Samples were added different concentrations of NaHSO3, the fluorescence signal of all these samples at 525 nm were recorded.

The procedures of HSO3− determination

The preparation of test system: Firstly, 0.48 mL DMSO and 0.02 mL probe solution were mixed in cuvette. Secondly, buffer solution was poured into the cuvette and made the capacity of cuvette up to 2 mL. Finally, ion solution was added. After waiting 5 min, it was mixed completely. Fluorescence spectrophotometer conditions: λex = 398 nm, λem = 525 nm, temperature: 25 °C. Voltage: 700 v. slit width: 10 nm, 10 nm. Sensitivity: 2.

Statistical analysis

All tests were repeated three times. The results were showed as standard deviation. It was performed with oringin 8.5 software (OriginLab Corporation, USA). The molecular structures were draw by ChemBioOffice 2008 (CambridgeSoft, UK).

Results and discussion

Probe synthesis

Probe 1 was synthesized through a Knoevenagel condensation reaction of 6-hydroxy-2-naphthaldehyde and 2-benzothiazoleacetonitrile over a piperidine catalyst (Fig. 1). Probe 1 was isolated from simple recrystallization. This synthetic method was facile and the raw materials are common. The probe 1 was characterized by 1H NMR, HRMS and 13C NMR (Figures A1-3, in supporting information).

Fig. 1.

Synthesis of probe 1

1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO), δ (ppm): 10.30(s, OH), 8.49(s, 1H), 8.45(s, 1H), 8.18(d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 8.17(d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 8.08(d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.90(d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.86(d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.58(t, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 7.50(t, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 7.21(s, 1H), 7.20(dd, J = 9.0 Hz, 2.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO): δ164.15, 158.81, 153.44, 148.83, 137.08, 134.69, 134.18, 131.72, 127.55, 127.53, 127.48, 127.24, 126.58, 125.28, 123.45, 122.87, 120.43, 117.13, 109.65, 103.47. HRMS: calcd. [M-H]+ 327.05976, found 327.05950.

The sensing property of probe 1 for HSO3−

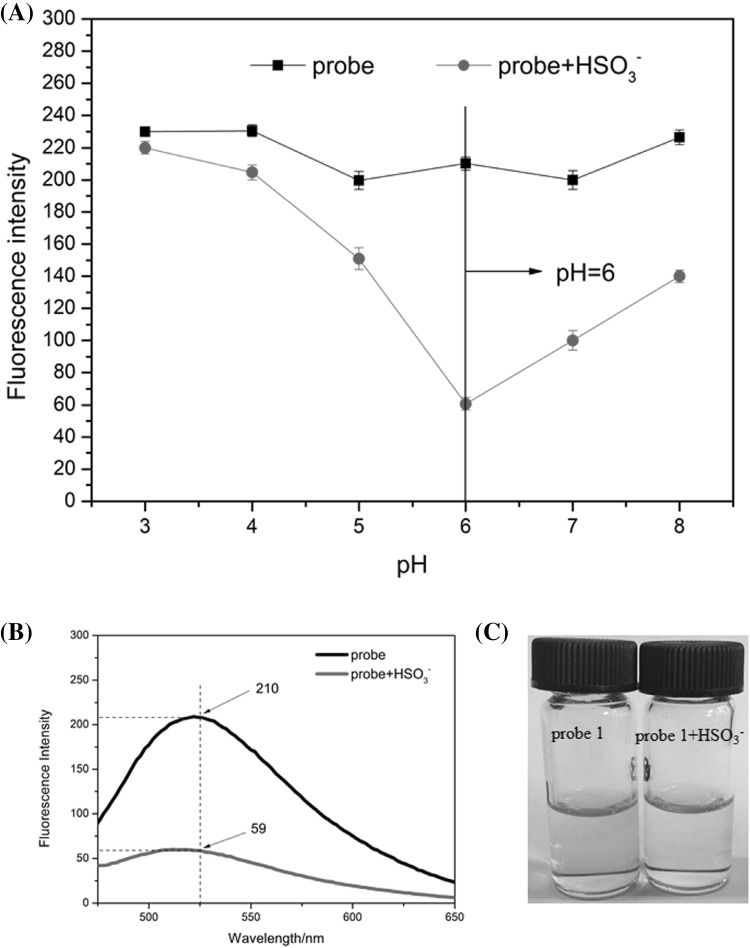

The fluorescent spectral responses of Probe 1 (10 μM) and Probe 1-HSO3− (300 μM) under various pH conditions (3.0–8.0) were observed at 25 °C (Fig. 2A). The fluorescence intensity of free Probe 1 was unchanged over the pH range, while that of Probe 1-HSO3− decreased quickly from pH 3.0–6.0, then increased from pH 6.0–8.0. The fluorescence intensity differences between Probe 1 and Probe1-HSO3− were greatest at pH 6.0. Hence, pH 6.0 was chosen for use in further experiments.

Fig. 2.

(A) Fluorescent intensity of probe 1 (10 μM) in the absence and presence of HSO3− (300 μM) in different pH buffer solution; (B) fluorescence spectra of probe 1 (10 μM) and probe 1 (10 μM) with HSO3− (300 μM) in PBS (pH 6.0) with DMSO (v/v, 3:1) at 25 °C; (C) the color changed of probe 1 (10 μM) in the absence and presence of HSO3− (300 μM). “PBS” is phosphate buffer solution

Probe 1 (10 μM) had stronger fluorescence in PBS (pH 6.0, PBS:DMSO = 3:1) at 25 °C. As HSO3− (300 μM) was added, the fluorescence intensity at 525 nm declined by almost four-fold (Fig. 2B) and the color changed from yellow to light yellow (Fig. 1C).

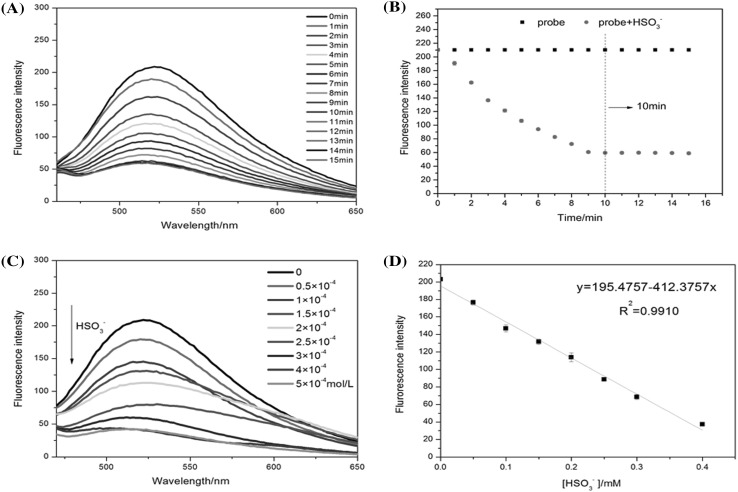

The fluorescence spectral response of Probe 1 (10 μM) for HSO3− (300 μM) was observed in 10 mM PBS (pH 6.0, PBS:DMSO = 3:1). As shown in Fig. 3A, the fluorescence intensity was observed each minute and decreased quickly after adding 300 μM HSO3−. The fluorescence signal at 525 nm was recorded. Fluorescence and HSO3− saturation were reached in 10 min (Fig. 3B). This confirms that Probe 1 took 10 min to react with HSO3− completely.

Fig. 3.

(A) Time-dependent fluorescence spectra of probe 1 (10 μM) in the presence of HSO3− (300 μM); (B) time-dependent fluorescence intensity changes of probe 1 (10 μM) in the presence of HSO3− (300 μM); (C) fluorescence spectra of probe 1 (10 μM) with HSO3− (0-500 μM); (D) the plot of fluorescence intensity difference with HSO3− from 0 to 400 μM in PBS (10 mM, pH 6.0). The test was repeated 3 times

To verify that Probe 1 has the ability to quantitatively detect HSO3− in PBS solution, the fluorescence intensity of Probe 1 (10 μM) with different concentrations of HSO3− added (0–500 μM) was measured (Fig. 3C). As shown in Fig. 3D, by plotting the data from Probe 1 reacting with different concentration of HSO3−, a good calibration curve was acquired. The fluorescence intensity was linearly connected with concentrations of HSO3− ranging 0–400 μM, and the detection limit (LOD) was counted as 1 × 10−7 M based on S/N = 3 according to the definition of a previous report. The fast response and excellent linear relationship provide a real-time quantitative method of HSO3− detection.

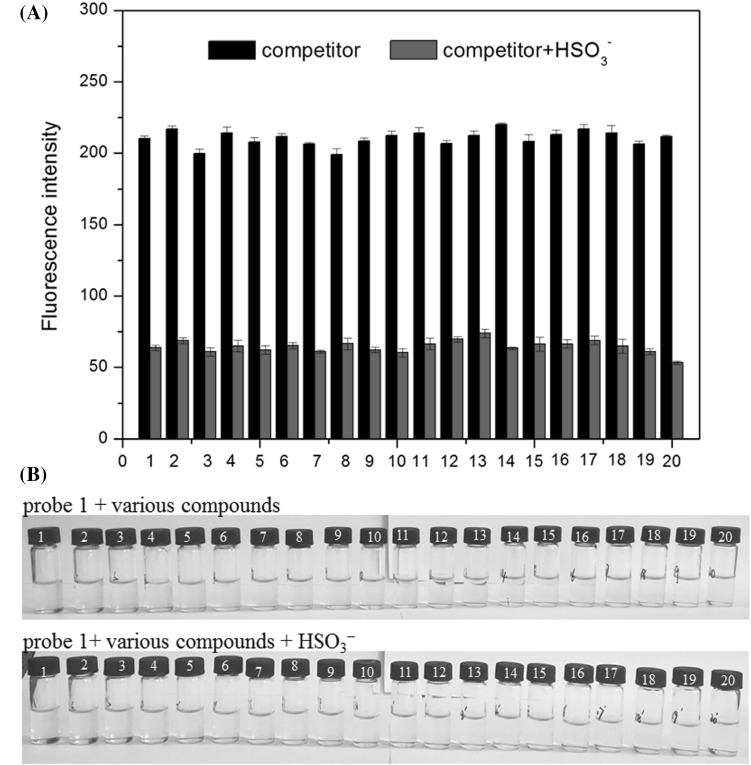

To explore the sensitivity of Probe 1 for HSO3− detection, various compounds, including AcO−, Br−, Cl−, I−, SCN−, NO3−, NO2−, SO32−, SO42−, HCO3−, CO32−, Cys, Hcy, GSH, F−, HSO3−, Na+, K+, NH4+, and Ca2+ were tested. As shown in Fig. 4A, these competitors resulted in limited fluorescence responses, having nearly no interference for HSO3− detection. This suggests that Probe 1 is highly selective for HSO3− and is not interfered with by other competing anions. Only HSO3− caused the color of the Probe 1 solution to change from yellow to light yellow (Fig. 4B). Therefore, Probe 1 has the specificity and ability to detect HSO3− under complicated conditions.

Fig. 4.

(A) Fluorescence intensity change of probe 1 (10 μM) upon addition of various species (300 μM for each. 1, blank; 2, AcO−; 3, Br−; 4, Cl−; 5, I−; 6, SCN−; 7, NO3−; 8, NO2−; 9, SO32−; 10, SO42−; 11, HCO3−; 12, CO32−; 13, Cys; 14, Hcy; 15, GSH; 16, F−; 17, Na+; 18, K+; 19, NH4+; 20, Ca2+. 300 μM for HSO3−). The test was repeated 3 times; (B) the solution color of probe 1 + various compounds and probe 1 + various compounds + HSO3− (300 μM for each. 1, AcO−; 2, Br−; 3, Cl−; 4, I−; 5, SCN−; 6, NO3−; 7, NO2−; 8, SO32−; 9, SO42−; 10, HCO3−; 11, CO32−; 12, Cys; 13, Hcy; 14, GSH; 15, F−; 16, Na+; 17, K+; 18, NH4+; 19, HSO3−; 20, Ca2+. 300 μM for HSO3−)

Reaction mechanism

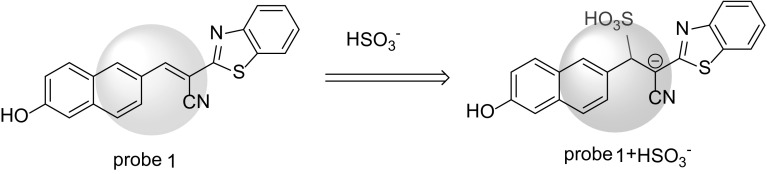

To demonstrate the identification mechanism of Probe 1 for HSO3−, HRMS and 1H NMR titration were carried out. As shown in supplementary Figure S6, the proton signal of the bridge double bond at 8.49 ppm (H8) disappeared and a new peak appeared at 6.94 ppm (H8’). To gain some insights into this mechanism, measurement of the UV–Vis absorption of Probe 1 and Probe 1-SO3H were necessary (Figure A4, supporting information). The addition of HSO3− led to a decreasing trend in the UV–Vis spectral intensity, suggesting that the C=C bonds are interrupted by nucleophilic addition (Figure A5, supporting information). The mechanism was further confirmed by HRMS, in which the peak appeared at m/z 407.01767 (calcd. 407.01646), corresponding to [M − 2H]− (Figure A6, supporting information). These results suggest that the reaction mechanism by which Probe 1 reacts with HSO3− is via nucleophilic addition with carbon–carbon double bonding (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The mechanism for probe 1 with HSO3−

Detection of HSO3− in sugar and red wine

Bisulfite is used widely in food as a preservative and antioxidant but excess amounts have negative health implications. We applied Probe 1 to detect HSO3− in real samples to verify the practical applicability of Probe 1 in food. Crystal sugar, soft sugar, granulated sugar, and three different red wines were obtained from Wumei Market, Beijing. Deionized water was used to dissolve sugar samples (Sun et al., 2014b; Wang et al., 2017). The wines and sugar solutions were added to PBS (pH 6.0, 10 mM), including Probe 1, and the fluorescence signals at 525 nm were recorded for data analysis. As shown in Table 1, the HSO3− levels in the three kinds of red wine were 0.7, 1.2, and 0.5 μM. In crystal sugar it was 0.6 μM, in granulated sugar it was 1.4 μM, and in soft sugar it was 0.6 μM. Then, different concentrations of HSO3− were added to the red wine and sugar samples. Probe 1 determined HSO3− concentrations with high recovery rates ranging from 94.34 to 105.10%. To prove that Probe 1 can detect HSO3− accurately, the titration method was used to analyze the concentrations of HSO3− in red wine and sugar. The relative deviation ranged from 3.22 to 8.69% (Table A1, supporting information). The results demonstrate that Probe 1 performs well as a probe for the quantitative detection of HSO3− in food.

Table 1.

Determination of HSO3− concentrations in sugar and red wine samples

| Sample | HSO3− detected (μmol) | HSO3− added (μmol) | HSO3− detected (μmol) | Recovery (%) | RSD (%; n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal sugar | 0.60 ± 0.01 |

10.00 30.00 |

11.00 32.00 |

103.78 104.58 |

0.18 0.13 |

| Granulated sugar | 1.40 ± 0.03 |

10.00 30.00 |

11.00 33.00 |

96.50 105.10 |

0.09 0.12 |

| Soft sugar | 0.60 ± 0.02 |

10.00 30.00 |

10.00 30.00 |

94.34 98.04 |

0.30 0.13 |

| Wine A | 0.70 ± 0.01 |

10.00 30.00 |

10.40 30.50 |

97.20 99.35 |

0.28 0.10 |

| Wine B | 1.20 ± 0.02 |

10.00 30.00 |

11.40 30.90 |

101.79 99.04 |

0.24 0.13 |

| Wine C | 0.50 ± 0.01 |

10.00 30.00 |

10.70 30.60 |

101.91 100.33 |

0.27 0.10 |

The test was repeated 3 times

A comparison of the chemical structures, detection limits, and response times of the proposed probe and some previously reported HSO3− fluorescent probes is listed in supplementary Table A2. These detection limit and response time of Probe 1 are comparable to those of other reported probes. In our previous study (Wang et al., 2017), a new fluorescent probe was synthesized to detect HSO3− in sugar, but the visible colorimetry was not good enough. The present study shows that Probe 1 has a novel structure and is very easy to synthesize. Upon the addition of HSO3−, Probe 1 has an obvious color change from yellow to light yellow. Probe 1 was successfully used to detect HSO3− concentrations in sugar and red wine. Furthermore, this experimental method is a friendly environment, with a reduction in the use of toxic reagents and risks to the analyst and the generation of residues. Probe 1 is applicable only to liquid phase analysis, solid samples must first be dissolved in solution.

In summary, we have developed a responsive and visible color-changing fluorescent probe for the detection of HSO3−. The function of Probe 1 relies on nucleophilic addition to C=C double bonds, which was verified by HRMS and 1H NMR studies. Importantly, once reacted with HSO3−, the color of Probe 1 solution visibly alters from yellow to light yellow. The color change is so obvious that Probe 1 can be used in practical applications for HSO3− detection. Finally, we have shown that this probe can be used to measure HSO3− quantitatively in sugar and red wine samples. Therefore, this probe has practical significance for the detection of HSO3− in a wide range of food sampling conditions. Further studies are underway to develop a more rapid and selective fluorescent probe with a more obvious color response.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The programme was recognitioned by the Support Project of High-level Teachers in Beijing Municipal Universities in the Period of 13th Five-year Plan (CIT&TCD201804021); Scientific and technological innovation and service capacity building-basic research business funding-study on the flavor of typical Chinese traditional dishes (PXM2018-014213-000033).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Haitao Chen, Email: yang123sx@126.com.

Xiaoming Wu, Email: wuxiao136ming@qq.com.

Jialin Wang, Email: 15701577507@163.com.

Hao Wang, Email: 2461539795@qq.com.

Feiyan Tao, Email: 75444671@qq.com.

Shaoxiang Yang, Phone: +86-10-68985382, Email: yangshaoxiang@th.btbu.edu.cn.

Hongyu Tian, Email: tianhy@btbu.edu.cn.

Yongguo Liu, Email: liuyg@th.btbu.edu.cn.

Baoguo Sun, Email: sunbg@btbu.edu.cn.

References

- Chen S, Hou P, Wang J, Song X. A highly sulfite-selective ratiometric fluorescent probe based on ESIPT. RSC Adv. 2012;2:10869–10873. doi: 10.1039/c2ra21471g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi MG, Hwang J, Eor S, Chang SK. Chromogenic and fluorogenic signaling of sulfite by selective deprotection of resorufin levulinate. Org Lett. 2010;12:5624–5627. doi: 10.1021/ol102298b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daunoravicius Z, Padarauskas A. Capillary electrophoretic determination of thiosulfate, sulfide and sulfite using in-capillary derivatization with iodine. ElectropHoresis. 2002;23:2439–2444. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200208)23:15<2439::AID-ELPS2439>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding YB, Tang YY, Zhu WH, Xie YS. Fluorescent and colorimetric ion probes based on conjugated oligopyrroles. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:1101–1112. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00436A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding YB, Zhu WH, Xie YS. Development of ion chemosensors based on porphyrin analogues. Chem Rev. 2016;117:2203–2256. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Liu C, Zhu YC, Zhu YZ. A boron-dipyrromethene-based fluorescent probe for colorimetric and ratiometric detection of sulfite. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59:11935–11939. doi: 10.1021/jf2032928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan SS, Hamza MS, Mohamed AH. A novel spectrophotometric method for batch and flow injection determination of sulfite in beverages. Anal Chim Acta. 2006;570:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Lin W, Xu Q, Wei H. A unique type of pyrrole-based cyanine fluoropHores with turn-on and ratiometric fluorescence signals at different pH regions for sensing pH in enzymes and living cells. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2014;6:22326–22333. doi: 10.1021/am506322h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leontiev AV, Rudkevich DM. Revisiting noncovalent SO2– amine chemistry: an indicator-displacement assay for colorimetric detection of SO2. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14126–14127. doi: 10.1021/ja053260v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Rapidly responsive and highly selective fluorescent probe for sulfite detection in real samples and living cells. Anal Chim Acta. 2015;897:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XJ, Yang QW, Chen WQ, Mo LN, Chen S, Kang J, Song XZ. A ratiometric fluorescent probe for rapid, sensitive and selective detection of sulfur dioxide with large Stokes shifts by single wavelength excitation. Org Biomol Chem. 2015;13:8663–8668. doi: 10.1039/C5OB00765H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu CH, Bhattacharjee B, Hsu CH, Chen SY, Ruaan RC, Chang WH. Highly luminescent CdSe nanoparticles embedded in silica thin films. J Electroceram. 2006;17:21–29. doi: 10.1007/s10832-006-9930-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McFeeters RF. Use and removal of sulfite by conversion to sulfate in the preservation of salt-free cucumbers. J Food Prot. 1998;61:885–890. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-61.7.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFeeters RF, Barish AO. Sulfite analysis of fruits and vegetables by highperformance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with ultraviolet spectrophotometric detection. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:1513–1517. doi: 10.1021/jf025693c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng MJ, Yang XF, Yin B, Guo Y, Suzenet F, En D, Duan YW. A hybrid coumarin–thiazole fluorescent sensor for selective detection of bisulfite anions in vivo and in real samples. Chem-Asian J. 2014;9:1817–1822. doi: 10.1002/asia.201402113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Figueroa LE, Giménez C, Agostini A, Aznar E, Marcos MD, Sancenón F, Amorós P. Selective and sensitive chromofluorogenic detection of the sulfite anion in water using hydropHobic hybrid organic–inorganic silica nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:13712–13716. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Zhang W, Qian J. A ratiometric fluorescence probe for selective detection of sulfite and its application in realistic samples. Talanta. 2017;162:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Fan S, Zhang S, Zhao D, Duan L, Li R. A fluorescent turn-on probe based on benzo [e] indolium for bisulfite through 1, 4-addition reaction. Sens Actuators B. 2014;193:173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2013.11.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Zhao D, Fan S, Duan L, Li R. Ratiometric fluorescent probe for rapid detection of bisulfite through 1, 4-addition reaction in aqueous solution. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:3405–3409. doi: 10.1021/jf5004539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Zhong C, Gong R, Mu H, Fu E. A ratiometric fluorescent chemodosimeter with selective recognition for sulfite in aqueous solution. J Org Chem. 2009;74:7943–7946. doi: 10.1021/jo9014744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YQ, Liu J, Zhang J, Yang T, Guo W. Fluorescent probe for biological gas SO2 derivatives bisulfite and sulfite. Chem Commun. 2013;49:2637–2639. doi: 10.1039/c3cc39161b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YQ, Wang P, Liu J, Zhang J, Guo W. A fluorescent turn-on probe for bisulfite based on hydrogen bond-inhibited C [double bond, length as m-dash] N isomerization mechanism. Analyst. 2012;137:3430–3433. doi: 10.1039/c2an35512d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L, Lin W, Zhu S, Yuan L, Zheng K. A coumarin-quinolinium-based fluorescent probe for ratiometric sensing of sulfite in living cells. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:4637–4643. doi: 10.1039/c4ob00132j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H, Qian J, Sun Q, Bai H, Zhang W. Colorimetric and ratiometric fluorescent detection of sulfite in water via cationic surfactant-promoted addition of sulfite to α, β-unsaturated ketone. Anal Chim Acta. 2013;788:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JL, Hao YF, Wang H, Yang SX, Tian HY, Sun BG, Liu YG. Rapidly Responsive and Highly Selective Fluorescent Probe for Bisulfite Detection in Food. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65:2883–2887. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b00353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Wu XM, Yang SX, Tian HY, Liu YG, Sun BG. A dual-site fluorescent probe for separate detection of hydrogen sulfide and bisulfite. Dyes Pigments. 2019;160:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.dyepig.2018.09.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MY, He T, Li K, Wu MB, Huang Z, Yu XQ. A real-time colorimetric and ratiometric fluorescent probe for sulfite. Analyst. 2013;138:3018–3025. doi: 10.1039/c3an00172e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MY, Li K, Li CY, Hou JT, Yu XQ. A water-soluble near-infrared probe for colorimetric and ratiometric sensing of SO2 derivatives in living cells. Chem Commun. 2014;50:183–185. doi: 10.1039/C3CC46468G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Z, Duan C, Sheng R, Xu J, Wang H, Zeng L. A Novel Colorimetric and Ratiometric Fluorescent Probe for Visualizing SO2 Derivatives in Environment and Living Cells. Talanta. 2018;176:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz ÜT, Somer G. Determination of trace sulfite by direct and indirect methods using differential pulse polarography. Anal Chim Acta. 2007;603:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2007.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C, Luo M, Zeng F, Wu S. A fast-responding fluorescent turn-on sensor for sensitive and selective detection of sulfite anions. Anal Methods. 2012;4:2638–2640. doi: 10.1039/c2ay25496d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L, Lin W, Zheng K, He L, Huang W. Far-red to near infrared analyte-responsive fluorescent probes based on organic fluorophore platforms for fluorescence imaging. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:622–661. doi: 10.1039/C2CS35313J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.