Abstract

Gochujang, a traditional Korean hot sauce, was prepared with a variety of antioxidant-rich supplements to improve its bioactive functions and preference by pungency-sensitive people. Among the tested ingredients, tomato paste exhibited the strongest antioxidant and neuroprotective activities when added as a supplement to traditional gochujang. Furthermore, oral administration of gochujang prepared with tomato paste to mice significantly improved cognitive function compared to original gochujang. As gochujang supplemented with tomato paste was found to contain an appreciable amount of lycopene with neuroprotective activity, it is most likely that the neuroprotective activity and cognitive improvement by the product was partially attributable to cis-lycopene, a highly bioavailable form converted from trans-lycopene during the manufacturing process of the product. However, a further study is required to verify the precise underlying mechanism of action.

Keywords: Gochujang, Tomato paste, Cognitive function, Lycopene

Introduction

Gochujang, a traditional Korean fermented condiment, is made by blending of glutinous grains (rice or wheat), pulverized fermented soybeans (meju), and pepper powder, which is then fermented and aged (Choi et al., 2014; Oh et al., 2006). In recent years, a number of reports have shown the health effects of gochujang including anti-obesity, anti-cancer, and anti-metastatic activities, imparted by its various functional metabolites derived from capsaicin, soy isoflavones, and soyasaponins (Kim et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2010; Park et al., 2001; Park et al., 2004; Patra et al., 2016; Shin et al., 2016).

In the present study, we attempted to develop a less spicy gochujang which would improve health benefits by replacing some of red pepper with other functional ingredients. Initial screening for antioxidant capacities of selected ingredients was conducted by intracellular antioxidant enzyme induction activity in cultured mouse hippocampal cells. The candidate ingredients tested in the study included blueberry, strawberry, blueberry, walnut, Korean yam, and tomato which were reported to have protective effect against oxidative stress-related diseases including cancer, osteoporosis, and cardiovascular disease (Friedman, 2013; Hartal and Danzig, 2003; Viuda-Martos et al., 2014). In particular, tomato paste was included as a potential ingredient of a functional gochujang because its component lycopene has been extensively studied for its biological functions (Kavanaugh et al., 2007). Several studies have demonstrated that lycopene counteracts cognitive impairment induced by various factors, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and neuroinflammation, a high-fat diet, galactose, diabetes, and colchicine (Friedman, 2013; Viuda-Martos et al., 2014). In addition, lycopene was shown to enhance cognitive function and hippocampal neurogenesis (Bae et al., 2016; Lei et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018); therefore, this study investigated whether gochujang supplemented with tomato paste could counteract the learning and memory deficit induced by scopolamine in a mouse model.

Materials and methods

Preparation of gochujang and its ethanolic extract

Traditional gochujang was prepared according to the procedure provided by Andong Jebiwon Agricultural Corp. (Andong, Korea). Briefly, 10 kg of gochujang was manufactured by mixing 2.5 kg red pepper powder, 5 kg grain syrup which was obtained by boiling and concentrating the mixture containing 2 kg of gelatinized glutinous rice powder and 2 kg of malt macerated in 10 L of water, 1.7 kg meju (dried fermented soybean block) powder, 0.75 kg salt, and 0.05 kg glasswort, and subsequently aging for 3 months.

The traditional gochujang supplemented with 5% (w/w) blueberry, strawberry, tomato paste, walnut, or Korean yam, was prepared according to the same procedure as traditional gochujang manufacturing as described above. Tomato paste used in gochujang preparation was made by briefly boiling chopped tomatoes for 5 min, passing through a sieve, and steadily simmering with stirring until reduced to a thick paste (50% of original volume). The paste was used for in vitro and in vivo studies after extracting in 80% (v/v) ethanol, filtered, and concentrated.

The freeze-dried gochujang samples were prepared by extracting gochujang with 10 volumes of 80% (v/v) ethanol, filtered, and concentrated to the concentration of 100 mg/mL. The samples were filtered through a 0.45 μm sterile syringe filter before use.

Determination of total phenolic and flavonoid contents

Total phenolics were determined using Folin-Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent (Kuhnen et al., 2014). Briefly, 100 µL of sample was mixed with 50 μL of sodium bicarbonate solution (10%, w/v), and then 15 μL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was added (previously diluted 5-fold with distilled water). After a 5 min incubation at room temperature, the sample mixture was transferred to a 96-well microplate, and the absorbance was measured at 593 nm using a microplate reader. The results are expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE).

Total flavonoid content was determined by a previously described colorimetric method using aluminum chloride, with slight modifications (Chung et al., 1999). Briefly, 25 µL of sample was mixed with 75 µL of 95% (v/v) methanol in a 96-well microplate. Then, 5 µL of 10% AlCl3·6H2O, 1 M potassium acetate, and 140 µL of distilled water were added, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 40 min. Absorbance readings were obtained at 415 nm with a microplate reader (Infinite 200; Tecan, Grödig, Austria). The total flavonoid content of the samples was extrapolated from standard curves generated with quercetin at 0–50 µg/mL.

Cell culture

A mouse hippocampal cell line, HT22, was obtained from Professors Dong Seok Lee and Kyung Sik Song (Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea). For routine maintenance, cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Welgene, Gyeongsan, Korea) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco™/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1 × penicillin–streptomycin solution (100 × , Welgene, Gyeongsan, Republic of Korea) in a humidified CO2 incubator (MCO-19-AIC, Sanyo, Osaka, Japan) at 37 °C and 5% CO2/95% air. HT22 cells were subcultured every other day at about 70% confluence with 0.05% trypsin–EDTA sodium salt solution (Welgene).

Cell viability assay

HT22 cells were seeded in a 96-well culture plate in 10% (v/v) FBS-containing DMEM at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well. After 24 h, cells were treated with 5 mM glutamate and/or gochujang samples for 24 h. The cell survival rate was measured using the D-Plus™ CCK cell viability assay kit (Dongin LS, Seoul, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell viability is presented as the percentage relative to the untreated control.

Antioxidant response element (ARE) activity assay

Transcriptional activity of the ARE was measured using the HT22-ARE cell that is carrying an ARE-luciferase construct (Bae et al., 2016). The cells were plated into a 96-well plate (Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well. After 24 h allowing to attach, cells were treated with various concentrations of each extract in 0.5% FBS-containing culture medium for 24 h. The luciferase activity was determined by a luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The luminescence was detected using a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and calibrated with the amount of total proteins. The values were then normalized against the control.

Determination of intracellular ROS level

HT22 cells were seeded into black-bottom 96-well plate at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well. After attached, the cells were treated with 5 mM glutamate and/or samples in 0.5% (v/v) FBS-containing media for 6 h. Subsequently, cells were subject to measurement of intracellular level of ROS by 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) assay according to Wang and Joseph (1999) with slight modifications. Briefly, dichlorfluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to a final concentration 20 μM, and applied to the PBS-washed cells for 30 min in dark. Fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and emission wavelength of 535 nm, in fluorescence microplate reader (Infinite 200, Tecan). The data were expressed as a relative intensity of fluorescence to the negative control.

Animal behavioral tests

The animal study was conducted by the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Kyungpook National University (approval number: KNU-2017-0160). Five-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Daehan Biolink (Seoul, South Korea) were allowed to adapt for 1 week. Mice were maintained at controlled laboratory conditions (temperature of 25 °C, humidity 50 ± 5%, 12 h light–dark cycle with water and chow ad libitum). After a week of acclimation, mice weighing 18–22 g of body weight (bw) were subject to the Y-maze, passive avoidance, and Morris water maze tasks.

For the behavioral tests, a total of 72 mice were (6-weeks-old) were divided into 9 groups (8 mice per group): (1) administrated vehicle only (negative control); (2) injected with scopolamine (1 mg/kg bw); (3) administered tacrine (a cholinesterase inhibitor; 10 mg/kg bw) and scopolamine; (4) administered original gochujang (plain gochujang, PG) at 200 mg/kg bw and scopolamine; (5) administered PG at 400 mg/kg bw and scopolamine; (6) administered gochujang supplemented with 5% tomato paste (tomato-supplemented gochujang, TSG) at 200 mg/kg bw and scopolamine; (7) administered TSG at 400 mg/kg bw and scopolamine; (8) administered tomato paste (tomato extract, TE) at 10 mg/kg bw and scopolamine; and (9) administered TE at 20 mg/kg bw and scopolamine. Test samples or tacrine were orally administered 1 h prior to performing every task, while the mice were allowed to adapt the atmosphere of the experimental room. After 30 min of administration, 1 mg/kg bw scopolamine was intraperitoneally injected to the mice to induce memory impairment. Another 30 min later, each mouse was subjected to the task.

The Y-maze is a tool for studying working memory by spontaneous alternation of mice (Yamada et al., 1999). A single 5-min test was performed in which each mouse was placed in the A arm of the maze. The Y-maze trials were recorded by a video camera, and the total number of arm entries and the order of entries were determined. Spontaneous alternations were defined as consecutive triplets of different arm choices. The percentage of alternations was calculated according to the following formula: % Alternation = [(number of alternations)/(total arm entries − 2)] × 100.

The passive avoidance task is a tool used to evaluate conditioned learning and memory ability (Kim et al., 2013). The apparatus (Gemini Avoidance System, San Diego, CA, USA) was equipped with two chambers and a guillotine door. On the day when Y-maze test was finished, mice were subject to adaptation for passive avoidance test. The next day, mice were orally administered the samples or tacrine, injected with scopolamine, and adapted in the bright chamber for 10 s. The day after, mice treated with samples and scopolamine were placed in the bright chamber for the training trial. Ten seconds later, the guillotine door between the bright and dark chambers was opened. When the mouse entered the dark chamber, the door closed and an electrical foot shock (0.5 mA) was delivered for 3 s through the stainless steel rods. One day after the training trial, the mouse was again placed in the bright chamber for the test trial (data acquisition). The time taken for a mouse to enter the dark chamber after the door was opened was defined as the latency time for both training and test trials. Latency for staying in the bright chamber was recorded up to 300 s. If a mouse did not enter the dark chamber within 300 s, the mouse was removed and assigned a latency score of 300 s. Long latency time represents higher learning and memory ability.

The Morris water maze task was performed using previously described protocols with slight modifications (Seo et al., 2016). The Morris water maze consisted of a circular pool (90 cm in diameter and 45 cm in height) with a featureless inner surface. The pool was filled with water (22 ± 1 °C) to a depth of 30 cm. The tank was placed in a dimly lit, soundproof test room with four visual cues. A white platform (6 cm in diameter and 29 cm in height) was then submerged in one of the pool quadrants. After passive avoidance task, the mice were dedicated to swimming training for 60 s in the absence of the platform. During the next 4 days, the mice were given test samples or tacrine and scopolamine every day and also given four trials per session per a day with the platform in place. Once locating the platform, a mouse was permitted to remain on it for 10 s. If the mouse did not locate the platform within 60 s, it was guided to place on the platform for 10 s. The swimming time in the pool quadrant where the platform had previously been placed was recorded, analyzed, and graphed.

Histology

Histological examination of the hippocampal CA1 region was conducted as reported previously (Seo et al., 2017). Briefly, brain tissue was collected, rinsed, and fixed by immersing in a 3.7% (v/v) formalin solution. Fixed brain tissue was embedded in paraffin block after dehydration, sectioned using a microtome (RM-2125 RT, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The stained tissue slices were observed and imaged under an optical microscope (Eclipse 80i; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed on cytoplasmic fractions prepared from hippocampal tissue homogenates to estimate the level of antioxidant enzymes according to a protocol described previously (Seo et al., 2016). Antibodies used in this study were as follows; the primary antibodies were anti-heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and anti-β-actin, and the secondary antibodies, conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, were anti-goat immunoglobulin G (IgG) or anti-mouse IgG (All from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA).

Analysis of lycopene in tomato paste and gochujang supplemented with tomato paste

Dried samples were extracted with 6 volumes of hexane:ethanol:acetone (2:1:1), vortexed for 1 min, and incubated at room temperature for 5 min to allow phase separation. The upper phase containing the lycopene was evaporated, dissolved in 1 mL ethyl acetate, and filtered through 0.45 μm sterile syringe filter for HPLC analysis.

Lycopene was analyzed by a Jasco 1580 HPLC system equipped with a PDA detector (Jasco) and a 4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm pore size C30 column (Develosil, Nomura chemical Co., Ltd, Seto, Japan). The compositions of solvents A and B were as follows: A, 88% methanol, 5% methyl tert-butyl ether, 5% H2O, and 2% (w/v) ammonium acetate; B, 78% methyl tert-butyl ether, 20% methanol, and 2% (w/v) ammonium acetate. The gradient was as follows; 45–50% B over 10 min, 50–95% B over 5 min, held at 95% B for 3 min, 95–100% B over 4 min, held at 100% B for 6 min, and 2 min to return to 45% B. The flow rate was 0.8 mL/min, and detection at 470 nm.

Statistical analysis

The data collected from triplicated independent experiments were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or standard error (SE). The obtained data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance with Duncan’s multiple range test using SPSS Statistics 22 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for multiple comparisons. Data were considered statistically significant when the p values were less than 0.05. Statistical differences were indicated with asterisks, hashtags, or different alphabetical letters.

Results and discussion

Antioxidant activities of potential ingredients of gochujang

Traditional gochujang was prepared using five different supplemental ingredients, including blueberry, strawberry, tomato paste, walnut, and Korean yam, along with original ingredients, and then the in vitro antioxidant activity of the preparations was evaluated.

Total phenolic content was higher in gochujang manufactured with 5% strawberry or walnut or Korean yam than the sauce made with the other ingredients (Table 1). However, gochujang prepared with tomato paste or blueberry had higher levels of total flavonoids than the other samples (Table 1). In particular, trans-lycopene contents in tomato paste and tomato paste-containing gochujang were 13 and 0.6 μg/g dry matter, respectively (Table 2).

Table 1.

Total phenol and flavonoid contents of gochujang supplemented with various functional ingredients

| Supplementary ingredients | Total phenols (mg GAE/100 g)1 | Total flavonoids (mg QE/100 g)1 |

|---|---|---|

| No additive | 71.81 ± 3.28c | 66.67 ± 4.64b |

| Blueberry, 5% (w/w) | 79.60 ± 5.81bc | 75.57 ± 1.91a |

| Tomato, 5% (w/w) | 82.52 ± 3.93ab | 69.75 ± 2.29b |

| Strawberry, 5% (w/w) | 91.07 ± 4.85a | 50.82 ± 1.81d |

| Walnut, 5% (w/w) | 89.34 ± 5.55a | 53.21 ± 1.51d |

| Korean yam, 5% (w/w) | 89.23 ± 5.47a | 61.48 ± 1.61c |

Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Values with different letters are significantly different among the samples (p < 0.05)

1GAE and QE represent gallic acid equivalent and quercetin equivalent, respectively

Table 2.

Trans-lycopene contents in the test samples

| Samples | Concentration (μg/g wet basis) |

|---|---|

| Plain gochujang | N.D. |

| Raw tomato | 31.5 ± 5.9a |

| Tomato paste | 13.0 ± 0.9b |

| Tomato-supplemented gochujang1 | 0.6 ± 0.1c |

Values represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Values with different letters are significantly different among the samples (p < 0.05)

N.D. Not detected

1Tomato-supplemented gochujang was prepared by supplementing plain gochujang with 5% (w/w) tomato paste

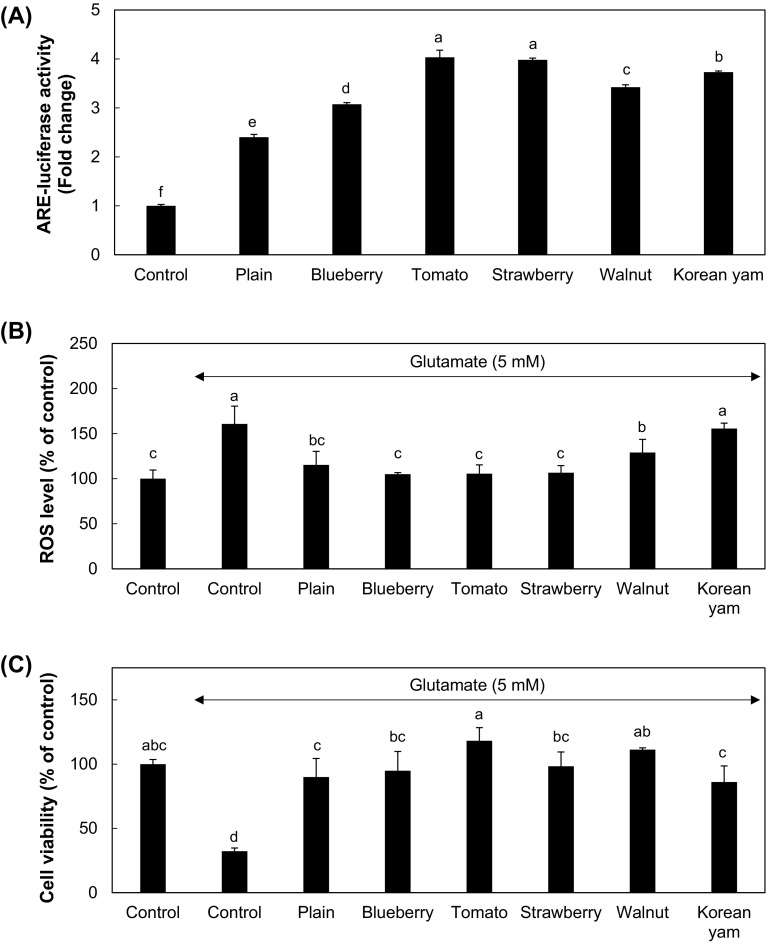

An ARE-luciferase reporter assay showed that gochujang prepared with tomato paste or strawberry had the highest antioxidant enzyme induction potential in mouse hippocampal HT22 cells (Fig. 1A). Similarly, cells treated with gochujang prepared with tomato paste, blueberry, or strawberry had the lowest intracellular ROS levels (Fig. 1B). These results of the ARE-luciferase reporter induction and intracellular ROS scavenging assays consistently indicated the superiority of tomato paste as an antioxidant ingredient for gochujang manufacturing. More specifically, gochujang supplemented with either tomato paste or strawberry had the highest antioxidant potential in mouse hippocampal HT22 cells as assessed by the ARE-luciferase reporter assay.

Fig. 1.

Neuroprotective effect of gochujang supplemented with functional ingredient. (A) ARE-luciferase reporter activity was assessed in HT22-ARE cells treated with various gochujang preparations at 400 μg/mL. HT22-ARE cells were incubated in the presence of ethanolic extract of gochujang supplemented with functional ingredients for 24 h, followed by assaying luciferase activity as described in Materials and methods. (B) Glutamate-induced ROS production was measured in HT22 cells treated with various gochujang preparations at 400 μg/mL and concomitantly challenged with glutamate. HT22 cells were pretreated with an ethanolic extract of gochujang supplemented with functional ingredients for 24 h, and then incubated in the presence of 5 mM glutamate for another 24 h. Intracellular ROS levels were measured as described in the materials and methods. (C) Glutamate-induced cytotoxicity was determined in HT22 cells with various gochujang preparations at 400 μg/mL and concomitantly challenged with glutamate. HT22 cells were pretreated with an extract of gochujang supplemented with various functional ingredients for 24 h, and then incubated in the presence of 5 mM glutamate for another 24 h. Cell viability was then measured by the MTT assay. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3). Bars with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Cytoprotective effect of gochujang supplemented with tomato paste against glutamate challenge

Challenging HT22 cells with glutamate at 5 mM dramatically reduced cell viability probably through increased ROS generation, and treatment of the cells with gochujang prepared with tomato paste effectively suppressed glutamate-induced cell death, leading to the full recovery of viability (Fig. 1C). Although gochujang made with other ingredients, including blueberry, strawberry, and walnut, had a slightly protective effect against the effects of glutamate, gochujang prepared with tomato paste was the most effective.

Consistent with the above-mentioned antioxidant capacities reducing intracellular ROS accumulation induced by glutamate treatment, gochujang supplemented with tomato paste completely restored cell viability of glutamate-challenged HT22 cells. These observations suggest that because of its neuroprotective and cognition-improving activities, tomato paste is the best supplemental gochujang ingredient. Furthermore, TSG had the highest overall acceptability score in the sensory test (data not shown).

Improvement of cognitive function by gochujang supplemented with tomato paste

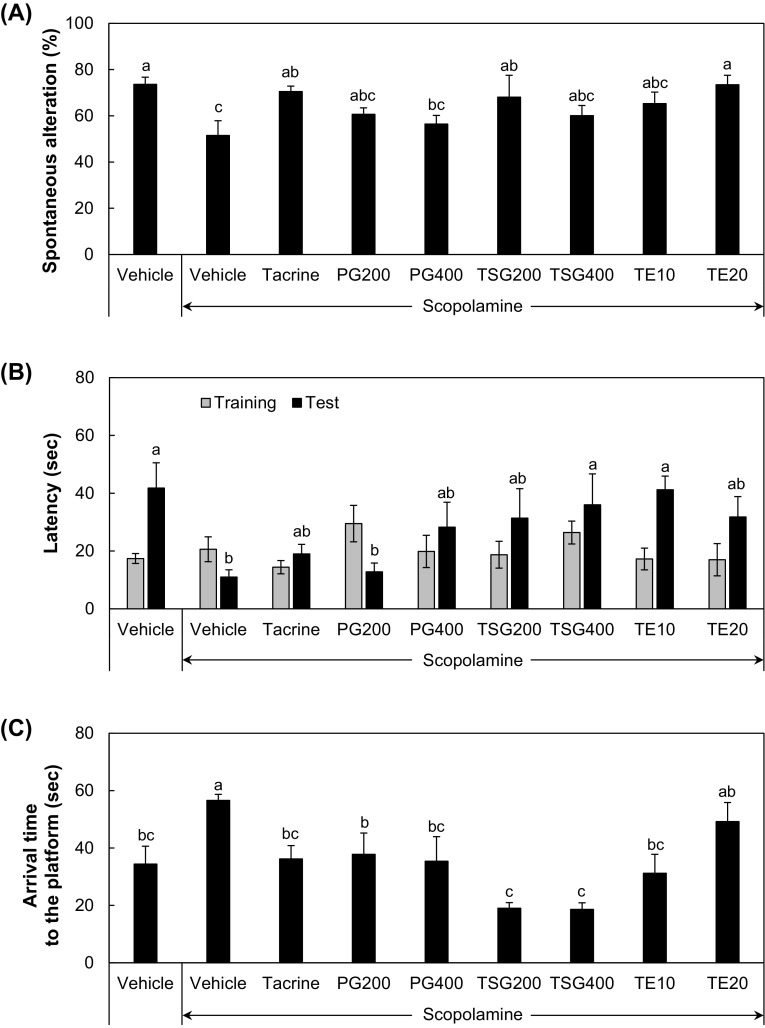

As tomato paste-supplemented gochujang showed comparatively high antioxidant capacities and hippocampal neuronal cell protective activity in addition to the best organoleptic preference, its in vivo effect on cognitive function was further investigated in scopolamine-induced hypomnesia mouse model. Mice were given scopolamine by intraperitoneal injection post-administration of ethanolic extracts of gochujang samples (PG and TSG) and TE. The memory impairment was assessed by behavioral tests such as Y-maze, passive avoidance, and Morris water maze tests (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of TSG administration on scopolamine-induced learning and memory impairment. Gochujang test samples were orally administered to C57BL/6 J mice within the 24 h period prior to scopolamine injection (1 mg/kg bw). The memory impairment was tested by Y-maze task (A), passive avoidance task (B), and Morris water maze task (C). PG, plain gochujang, was given at 200 or 400 mg/kg bw; TSG, tomato paste-supplemented gochujang, was given at 200 or 400 mg/kg bw; TE, tomato paste extract, was given at 10 or 20 mg/kg bw. Tacrine (10 mg/kg bw), an AChE inhibitor, was used as a positive control. Values are mean ± SE from 5 individual animals (n = 5). Bars with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Scopolamine-induced memory impairment was manifested by a reduced spontaneous exploration as evaluated by Y-maze test (Fig. 2A), a decreased latency staying in a bright chamber by passive avoidance test (Fig. 2B), and a delayed time for finding the platform in Morris water maze test (Fig. 2C). Moreover, administration with TSG or TE for 3 days restored the exploration reduction (Fig. 2A). TSG administration at a dose of 200 μg/kg for a week improved the conditioned memory (Fig. 2B) and that for 2 weeks was effective in preventing spatial learning and memory deficit by scopolamine injection (Fig. 2C). The memory-improving effect of TSG was higher than any other samples tested including tacrine, PG and TE.

These results suggest that the administration of tomato paste or TSG increased the willingness of the mice to explore new environments, and that mice administered TSG tended to have superior working memory compared to mice fed unsupplemented gochujang, although there was no statistical significance between the two groups of mice.

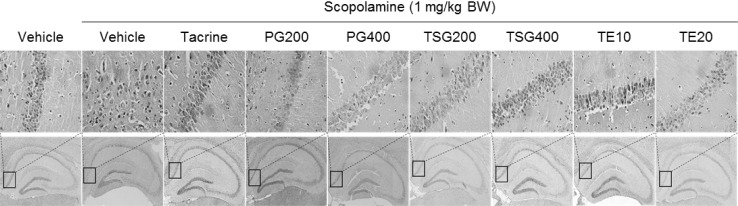

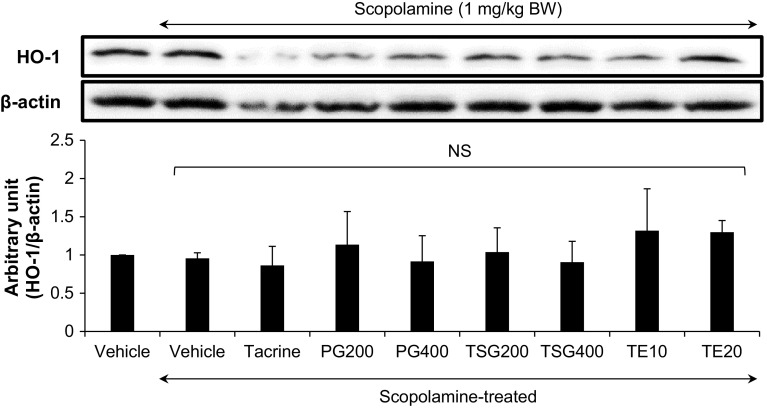

Protective effect of tomato gochujang against scopolamine-induced hippocampal damage

To examine the possible protective mechanism of oral TSG administration against scopolamine-induced memory impairment, the mouse hippocampal CA1 region was stained and evaluated for injury level. While scopolamine injection caused a significant damage, including hippocampal pyramidal cell loss, the TSG administration most effectively attenuated the scopolamine-induced abnormality in the CA1 region, among the test samples, and showed apparent protective effect from scopolamine-induced damage (Fig. 3). However, the expression level of HO-1 protein in the hippocampus did not differ among the experimental groups treated with various gochujang samples (Fig. 4). Taken together with the behavioral tests, this study demonstrated that TSG administration improved scopolamine-induced learning and memory impairment and hippocampal neuronal structure in vivo.

Fig. 3.

Protective effect of TSG administration against scopolamine-induced damage in CA1 area of mouse hippocampus. After sacrifice of the experimental mice, the brain tissues were dissected and sectioned for microscopic observation. Representative images (× 100) displayed that the hippocampal CA1 region where pyramidal cell loss occurred in scopolamine-injected mouse brain was found to be neatly structured in TSG or TE-treated mouse brain. PG plain gochujang; TSG tomato paste-supplemented gochujang; TE tomato paste extract

Fig. 4.

Effect of TSG administration on the HO-1 expression in the hippocampus. Gochujang test samples were orally administered to mice 24 h prior to scopolamine injection, and then the hippocampus was collected and hippocampal homogenate was subjected to western blot analysis for HO-1 protein expression. PG plain gochujang; TSG tomato paste-supplemented gochujang; TE tomato paste extract. Values are mean ± SD (n = 4). NS indicates no statistically significant difference among experimental groups

It has been well documented that tomato contain a variety of phytochemicals that are associated with cognitive improvement. Tomato and its products are good sources of vitamins and minerals such as potassium, folate, and vitamin A, C, and E as well as phytochemicals including lycopene, β-carotene, quercetin, and kaempferol (Canene-Adams et al., 2005). Our data demonstrated that TSG had relatively high total phenolic and flavonoid contents (Table 1). The trans-lycopene contents in tomato paste and tomato-containing gochujang were 13 and 0.6 μg/g of dry matter, respectively (Table 2).

Considering multiple studies using animal models supporting that lycopene is helpful to improve cognitive function, mostly due to its antioxidant activity (Canene-Adams et al., 2005; Kaur et al., 2011; Kuhad et al., 2008; Prema et al., 2015), our observation that oral administration of TSG improved scopolamine-induced learning and memory impairment may presumably be attributable to the combinatorial work of antioxidant substances in TSG including lycopene.

The superior antioxidant enzyme induction and neuroprotective effects of TSG appears to be associated with the presence of lycopene and its synergistic effect with the other polyphenolic compounds in TSG, as it showed higher antioxidant enzyme inducing activity despite the similar total phenolic and flavonoid contents to that in gochujang containing other ingredients. Furthermore, there should be significant level of cis-lycopene in gochujang, which is known to be more bioavailable than the trans form, as the trans-lycopene in the tomato must have been converted to the cis form during gochujang manufacturing by processes such as heat treatment and fermentation. Unfortunately, this study could not assay the cis-lycopene content in the samples because of a technical limitation.

Lycopene has been reported to improve cognitive function in several animal studies, mostly due to its antioxidant activity (Canene-Adams et al., 2005; Prema et al., 2015). In fact, our unpublished data demonstrated that lycopene, tomato paste, and TSG did not inhibit cerebral acetylcholine esterase activity (data not shown). Lycopene has also been reported to ameliorate neurological deficits, brain water content, blood–brain barrier disruption and neuronal apoptosis through inflammatory reaction suppression which is, in turn, mediated by a diminished expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and ICAM-1 (Wu et al., 2015).

In conclusion, gochujang prepared with tomato paste showed enhanced neuroprotective and cognitive function-improving activities compared to unsupplemented gochujang, without a significant decline in sensory preference.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Grant from INNOPOLIS, Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT), Republic of Korea (2018).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sunghee Kim, Phone: +82-53-950-5752, Email: ksh20414@naver.com.

Jisun Oh, Phone: +82-53-950-5752, Email: j.oh@knu.ac.kr.

Chan Ho Jang, Phone: +82-53-950-5752, Email: cksghwkd7@gmail.com.

Jong-Sang Kim, Phone: +82-53-950-5752, Email: vision@knu.ac.kr.

References

- Bae JS, Han M, Shin HS, Shon DH, Lee ST, Shin CY, Lee Y, Lee DH, Chung JH. Lycopersicon esculentum extract enhances cognitive function and hippocampal neurogenesis in aged mice. Nutrients. 2016;8:679. doi: 10.3390/nu8110679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canene-Adams K, Campbell JK, Zaripheh S, Jeffery EH, Erdman JW. The tomato as a functional food. J. Nutr. 2005;135:1226–1230. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.5.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SJ, Lee NH, Choi UK. Comparison of the quality characteristics of Korean fermented red pepper-soybean paste (Gochujang) and Meju made with soybeans (Glycine max L.) germinated under dark and light conditions. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 23: 1223–1230 (2014)

- Chung HS, Chang LC, Lee SK, Shamon LA, van Breemen RB, Mehta RG, Farnsworth NR, Pezzuto JM, Kinghorn AD. Flavonoid constituents of Chorizanthe diffusa with potential cancer chemopreventive activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999;47:36–41. doi: 10.1021/jf980784o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M. Anticarcinogenic, cardioprotective, and other health benefits of tomato compounds lycopene, alpha-tomatine, and tomatidine in pure form and in fresh and processed tomatoes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:9534–9550. doi: 10.1021/jf402654e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartal D, Danzig L. Tomato extract: a functional ingredient with health benefits. Agro. Food Ind. Hi. Tech. 2003;14:18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur H, Chauhan S, Sandhir R. Protective effect of lycopene on oxidative stress and cognitive decline in rotenone induced model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 2011;36:1435–1443. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0469-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh CJ, Trumbo PR, Ellwood KC. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s evidence-based review for qualified health claims: tomatoes, lycopene, and cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 99: 1074–1085 (2007) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kim HJ, Suh HJ, Kim JH, Kang SC, Park S, Lee CH, Kim JS. Estrogenic activity of glyceollins isolated from soybean elicited with Aspergillus sojae. J. Med. Food. 2010;13:382–390. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2009.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HV, Kim HY, Ehrlich HY, Choi SY, Kim DJ, Kim Y. Amelioration of Alzheimer’s disease by neuroprotective effect of sulforaphane in animal model. Amyloid. 2013;20:7–12. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2012.751367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Oh BH, Shin DH. Quality characteristics of kochujang prepared with different meju fermented with Aspergillus sp and Bacillus subtilis. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2008;17:527–533. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhad A, Sethi R, Chopra K. Lycopene attenuates diabetes-associated cognitive decline in rats. Life Sci. 2008;83:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnen S, Moacyr JR, Mayer JK, Navarro BB, Trevisan R, Honorato LA, Maraschin M, Pinheiro Machado Filho LC. Phenolic content and ferric reducing-antioxidant power of cow’s milk produced in different pasture-based production systems in southern Brazil. J. Sci. Food Agric. 94: 3110–3117 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lei XF, Lei LJ, Zhang ZL, Cheng Y. Neuroprotective effects of lycopene pretreatment on transient global cerebral ischemia-reperfusion in rats: the role of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Report. 2016;13:412–418. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh BH, Kim YS, Jeong PH, Shin DH. Quality characteristics of Kochujang meju prepared with Aspergillus species and Bacillus subtilis. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2006;15:549–554. [Google Scholar]

- Park KU, Kim JY, Cho YS, Yee ST, Jeong CH, Kang KS, Seo KI. Anticancer and immuno-activity of onion Kimchi methanol extract. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2004;33:1439–1444. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2004.33.9.1439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park KY, Kong KR, Jung KO, Rhee SH. Inhibitory effects of Kochujang extracts on the tumor formation and lung metastasis in mice. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2001;6:187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Patra JK, Das G, Paramithiotis S, Shin HS. Kimchi and other widely consumed traditional fermented foods of Korea: a review. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1493. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prema A, Janakiraman U, Manivasagam T, Arokiasamy JT. Neuroprotective effect of lycopene against MPTP induced experimental Parkinson’s disease in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 2015;599:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo JY, Ju SH, Oh J, Lee SK, Kim JS. Neuroprotective and cognition-enhancing effects of compound K isolated from red ginseng. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016;64:2855–2864. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b05789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo JY, Lim SS, Kim J, Lee KW, Kim JS. Alantolactone and isoalantolactone prevent amyloid beta25-35-induced toxicity in mouse cortical neurons and scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment in mice. Phytother. Res. 2017;31:801–811. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin HW, Jang ES, Moon BS, Lee JJ, Lee DE, Lee CH, Shin CS. Anti-obesity effects of gochujang products prepared using rice koji and soybean meju in rats. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016;53:1004–1013. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-2162-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viuda-Martos M, Sanchez-Zapata E, Sayas-Barbera E, Sendra E, Perez-Alvarez JA, Fernandez-Lopez J. Tomato and tomato byproducts. Human health benefits of lycopene and its application to meat products: a review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 54: 1032–1049 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang H, Joseph JA. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using microplate reader. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;27:612–616. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang Z, Li B, Qiang Y, Yuan T, Tan X, Wang Z, Liu Z, Liu X. Lycopene attenuates western-diet-induced cognitive deficits via improving glycolipid metabolism dysfunction and inflammatory responses in gut-liver-brain axis. Int. J. Obes. (in press) (2018) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wu A, Liu RC, Dai WM, Jie YQ, Yu GF, Fan XF, Huang Q. Lycopene attenuates early brain injury and inflammation following subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015;8:14316–14322. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Tanaka T, Han D, Senzaki K, Kameyama T, Nabeshima T. Protective effects of idebenone and alpha-tocopherol on beta-amyloid-(1-42)-induced learning and memory deficits in rats: implication of oxidative stress in beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:83–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao BT, Liu H, Wang JM, Liu PJ, Tan XT, Ren B, Liu ZG, Liu XB. Lycopene supplementation attenuates oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and cognitive impairment in aged CD-1 mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66:3127–3136. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b05770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]