Abstract

Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) regulates the synthesis, transport and enterohepatic circulation of bile acids (BA) by modulating the expression of related genes in the liver and small intestine. The composition of the gut microbiota is correlated with metabolic diseases, notably obesity and non-alcoholic fatty acid disease (NAFLD). Recent studies revealed that bacterial metabolism of BA can modulate FXR signaling in the intestine by altering the composition and concentrations of FXR agonist and antagonist. FXR agonist enhances while FXR antagonist suppresses obesity, NAFLD and insulin resistance. The role of intestinal FXR in metabolic disease was firmly established by the analysis of mice lacking FXR that are metabolic resistant to HFD-induced metabolic disease. This is mediated by FXR modulating in part the expression of genes involved in ceramide synthesis in the small intestine. In ileum of obese mice due to the presence of endogenous FXR agonists produced in the liver, these genes are activated, while in mice with altered levels of specific gut bacteria, levels of an FXR antagonist, tauro-β-muricholic acid (T-β-MCA) increase and FXR signaling and ceramide synthesis are repressed. T-β-MCA, which is metabolized in wild-type mice, led to the discovery of glycine-β-muricholic acid (Gly-MCA) that is stable in the intestine and a potent inhibitor of FXR signaling. These studies reveal that ceramides produced in the ileum under the control of FXR, influence metabolic disease, and suggest that novel FXR antagonist such as Gly-MCA that specifically inhibit intestine FXR, could serve as potential drug for the treatment of metabolic disease.

Keywords: Bile acids, Farnesoid X receptor, Ceramides, Obesity, Diabetes, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

The Farnesoid X Receptor

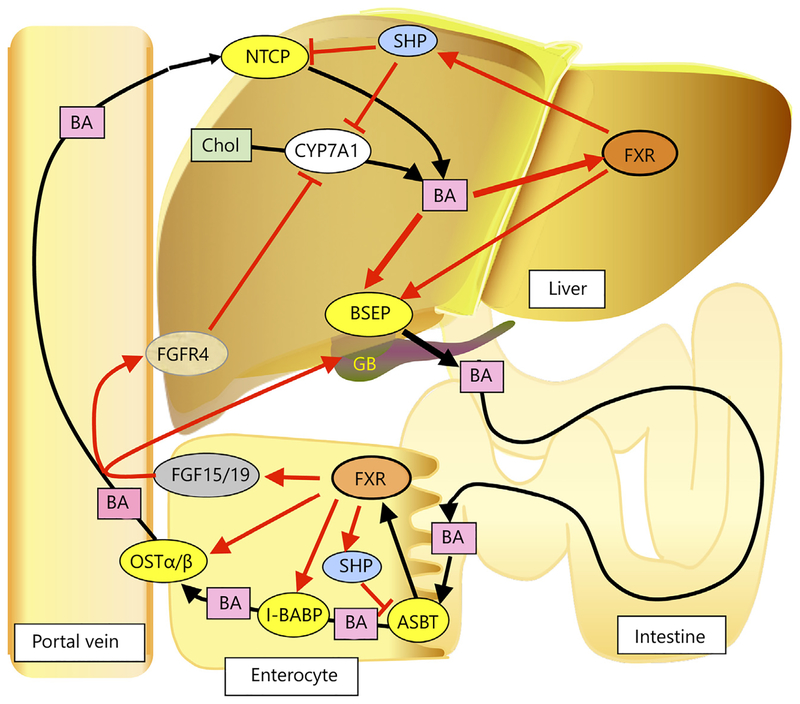

The farnesoid X receptor (FXR, NR1H4) was first described as an orphan receptor [1], and as a farnesoid-activated nuclear receptor [2], when initially discovered by two laboratories. Subsequently, bile acids (BA) were found to be the natural endogenous ligands for FXR [3]. FXR is expressed in liver and intestine, and at lower levels in the adrenal gland [4]; it is also expressed in certain cells of the kidney [4, 5]. FXR controls BA synthesis and transport and the enterohepatic circulation of BA as revealed by gene expression studies and the cholestatic liver phenotype in the Fxr-null mice [6]. Endogenous ligands for FXR include the primary BA chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), and cholic acid (CA), the secondary BA deoxy cholic acid, and lithocholic acid, and the conjugated BA taurocholic acid. When BA levels increase in the liver, FXR is activated by these ligands, BA synthesis is suppressed, BA transport to the small intestine is increased, and BA uptake from the blood is decreased as a result of increased and decreased expression of FXR target genes that include BA transporters and BA synthesis enzymes. FXR-mediated gene suppression occurs through the novel pathway of induction of the small heterodimer partner (SHP, NR0B2), a member of the nuclear receptor super-family that binds to and interferes with the positive regulation of gene expression by other nuclear receptors including liver receptor homolog-1 (NR5A2) and liver X receptor (NR1H3); these nuclear receptors are involved in the control of genes that participate in BA synthesis and transport [7]. Shp is a direct FXR target gene in the liver and ileum. The role of FXR in the regulation of BA homeostasis is shown in figure 1. In the liver, through the SHP pathway, FXR suppresses CYP7A1, the rate-limiting enzyme in BA synthesis, and Na+-taurocholate cotrans-porting polypeptide (NTCP, SLC10A1) that transports BA from the blood to the liver. FXR directly activates the expression of bile salt export protein (BSEP, ABCB11) that transports BA from the liver to the gall bladder (GB). OATPs and ABCB4 also contribute to BA transport in the liver. Thus, when BA levels increase in the liver, CYP7A1, the rate-limiting enzyme in BA synthesis, is decreased, NTCP and BA uptake from the blood is decreased, and BSEP and BA transport to the intestine is increased. In the ileum enterocyte, FXR activation by BA agonists produced in the liver enhances transport of BA from the gut lumen to the blood by inducing expression of apical sodium-BA transporter (ASBT, SLC10A2) and organic solute and steroid transporter alpha-beta (OSTα/β that transports BA from the enterocyte to the blood [8]. Induction of intestinal BA-binding protein (I-BABP) by FXR also enhances this transfer across the enterocyte to reach ASBT. There is another means by which intestinal FXR controls BA synthesis in the liver. Intestinal FXR induces the expression of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF)15 (designated FGF19 in humans) gene (Fgf15) in the enterocyte. FGF15/19 is transported to the liver and binds to and activates the hepatocyte plasma membrane receptor complex FGFR4/β-Klotho, resulting in the suppression of CYP7A1 expression [9]. FGF15/19 also promotes emptying of the GB that facilitates the dumping of hepatic BA to the intestine through binding to the FGFR3/β-Klotho complex [10]. Under conditions where BA levels are markedly elevated in the intestine, FXR is activated, which stimulates the transport of BA into the blood stream for delivery back to the liver and through FGF15/19 lowers hepatic BA synthesis. In summary, elevated hepatic BA activate FXR to increase their export to the intestine, decrease uptake of BA from the blood and decrease BA synthesis. Intestinal FXR activation further increases FXR15/19 to decrease BA synthesis in the liver through the suppression of CYP7A1 expression.

Fig. 1.

Roles of FXR signaling in the enterohepatic circulation of BA. BA are synthesized from cholesterol (Chol) with CYP7A1, a cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase as the rate-limiting enzyme. BA activates FXR, which through control of a number of genes, accelerates BA export from liver through direct induction of BSEP expression, and decreases BA uptake to liver by the suppression of NTCP expression via hepatic FXR-SHP signaling. FXR decreased BA synthesis by the SHP-mediated suppression of the gene encoding CYP7A1. In the intestinal epithelia cells, BA activation of FXR decreases BA absorption at the intestine through the suppression of ASBT via FXRSHP signaling, and stimulated BA transport to the blood by induction of the gene encoding OSTα/β. Transport across the enterocyte is facilitated by I-BABP, which is also induced by FXR. FXR also induces the expression of FGF15/19, which upon binding to FGFR4-βKlotho complex on the plasma membrane, suppresses the expression of CYP7A1 in the liver. FGF15/19 also stimulates filling of the GB through binding to FGFR3. Thus, when hepatic and ileal BA levels increase, FXR is activated, leading to decreased BA pool size.

FXR Mediates the Influence of Gut Bacteria on Metabolic Disease

It is firmly established that the gut microbiota is markedly altered in obesity and related metabolic abnormalities including insulin resistance and fatty liver as compared with normal healthy controls [11, 12]. This suggests that gut bacterial composition mediated metabolic diseases. However, the precise mechanism for this association between the gut microbiota and metabolic disease has remained elusive. Gut bacteria could contribute to the metabolism of dietary compounds such as fatty acids and thus decrease calorie consumption by the body or gut bacteria could produce metabolites from dietary constituents that influence systemic biochemical processes that promote metabolic disease [13]. For example, bacteria fermentation produce butyrate and short chain fatty acids that can, under the right circumstances, have deleterious effects in the host leading to metabolic disease.

An observation made 13 years ago led to recent studies revealing that FXR mediates in part the influence of gut bacteria on metabolic disease [14]. Mice fed the antioxidant tempol, a low molecular weight, free radical nitroxide that protects cells from oxidative stress, gained less weight than their control counterparts on an either normal low-fat or a high-fat diet, and this was accompanied by decreased spontaneous cancer and increased longevity [14]. The mechanism of the tempol effect was investigated by use of metabolomics revealing an increase in fatty acid metabolism and an alteration of the composition of the gut microbiota after oral administration of tempol [15] The latter was confirmed by 16S rRNA gene-sequencing community analysis revealing that upon tempol administration, the intestinal bacterial population was shifted from the phylum Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes within 5 days of commencing treatment, with specific decreases within the phylum Firmicutes, in the Lactobacillaceae family, due to reduced levels Lactobacillus spp. [16]. While the shift in the microbiota composition was correlated with the effects of tempol, the mechanism was unclear. Other studies revealed that mice on tempol have elevated levels of the conjugated BA tauro-β-muricholic acid (T-β-MCA) as compared to their control counterparts. It is known that bacteria, including Lactobacillus spp., have bile salt hydrolase (BSH) that hydrolyzes conjugated BA produced in the liver; this likely accounts for the increase in T-β-MCA in tempol-treated mice, since lower Lactobacillus spp. and BSH would result in less T-β-MCA hydrolysis [16]. A clue to the link between Lactobacillus spp. and obesity was revealed by the finding that T-β-MCA is an antagonist of FXR [16]. Indeed, mice fed with tempol had lower FXR signaling in the intestine than did control mice, as determined by the analysis of mRNAs encoded by the FXR target genes Shp and Fgf15 [16]. Similar results were found with mice that were administered antibiotics, thus further confirming that gut bacteria and BSH activity modulated intestinal levels of T-β-MCA [17]. The question then arose as to whether tempol or antibiotics administration, which lowered Lactobacillus spp. and BSH activity, increased intestinal T-β-MCA, and suppressed FXR, was the main pathway that led to the modulation of obesity, insulin resistance and fatty liver. This was established by studies using mice that lack FXR expression in the intestine; these mice when fed a high fat diet exhibited less obesity, insulin resistance and fatty liver compared with their wild-type counterparts [16, 17]. Mice lacking intestinal FXR fed on HFD were also resistant to the effects of tempol and antibiotics, although they were already metabolically fit [16, 17].

Mechanism by Which FXR Controls Metabolic Disease

HFD-induced obese mice have elevated levels of serum ceramides, which were decreased by about 30–50% when treated with tempol or antibiotics. Intestine-specific Fxr-null mice also have lower serum ceramides as compared to their wild-type counterparts [16, 17], indicating that the ceramide levels are controlled in part by FXR. While ceramides are essential lipids for normal skin and nerve function, at high concentrations, they can have adverse effects [18, 19]. Ceramide levels are positively correlated with metabolic disease in mice and correlative studies in humans suggest that ceramides are associated with metabolic disease, such as insulin resistance [20–22]. Ceramide levels are regulated by secreted endocrine factors and nuclear receptors involved in the control of metabolism. For example, the positive effect of FGF21 on insulin resistance is due in part to reduced cellular ceramides as a result of adiponectin stimulation of ceramide conversion to sphingosine [23]. Antagonism of FXR on metabolic disease appears to be mediated though the modulation of ceramide levels.

Mechanistically, mice under intestinal FXR antagonism or lacking intestinal FXR have increased beige adi-pose depots that mediate weight loss by increasing energy expenditure. Similar to brown adipose tissue, beige adipocytes are associated with increased metabolism and decreased obesity [24]. The increased beige adipose, as measured by monitoring uncoupling protein 1 expression and other genes that are preferentially expressed in brown and beige adipocytes, is correlated with the lowering of serum ceramides through the modulation of FXR signaling in the ileum. Increased adipose beiging likely accounts for the weight loss in HFD-fed mice treated with tempol and antibiotics. This is due in part to the FXR-mediated decrease in serum ceramides since ceramides inhibit conversion of white to beige adipose in vitro [25]. Ceramides also promote fatty liver as revealed by studies using primary mouse hepatocytes treated with ceramides [17]. SREBP-1C, a transcription factor that controls fatty acid synthesis in liver is induced and triglyceride levels increased when these cells are stimulated with ceramide.

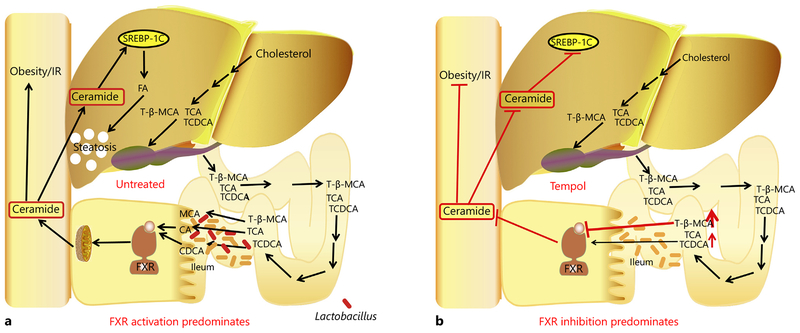

In summary, in obese mice, BA produced in the liver and transported to the intestine may have high FXR agonist activity resulting in increased FXR signaling and elevated ceramide production (fig. 2). The antagonist T-β-MCA is rapidly hydrolyzed by the gut microbiotal and does not reach concentration that would inhibit FXR signaling. When obese mice are treated with tempol or antibiotics, T-β-MCA levels are elevated in the intestine due to lower and decreased BSH activity, so that FXR is inhibited and intestinal and blood ceramides are decreased. The decreased ceramides mainly result in increased adipose beiging and lower hepatic lipids. While it is currently not known whether this pathway exists in humans, FXR expression and signaling are increased in obese individuals. The composition of BA agonist and antagonist in humans need to be examined to determine whether human obesity is associated with increased FXR agonist/antagonist ratios.

Fig. 2.

Modulation of FXR signaling in the ileum and metabolic disease. a In untreated mice, BA metabolites produced in the liver enter the enterocyte. Most of these metabolites are FXR agonists that activate FXR resulting in increased serum ceramides. The FXR antagonist T-β-MCA is rapidly hydrolyzed by bacterial BSH. Ceramides induce endoplasmic reticulum stress in the adipocytes and liver resulting in decreased rates of metabolism through suppression of adipose beiging and increased fatty liver through the activation of fatty acid synthesis pathways. b When mice are treated with tempol or antibiotics, gut bacteria populations are altered including lower levels of bacterial species like Lactobacillus spp. that express BSH resulting in the accumulation of the FXR antagonist T-β-MCA. Inhibition of FXR results in lower levels of serum ceramides, increased adipose beiging and decreased fatty acid synthesis and the associated deleterious phenotypes found in HFD-fed wild-type mice.

FXR as a Drug Target

Since FXR controls BA and lipid levels in liver, it has been considered a viable drug target for the treatment of cholestasis and fatty liver, including non-alcoholic fatty acid disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). A derivative of the FXR agonist CDCA [26], 6α-ethyl-CDCA (obeticholic acid, OCA), was recently approved by the US FDA for the treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), and is in clinical trials for treatment of NASH [27]. A reduction in NAFLD was observed in a phase 3 trial with OCA, although a few side effects were noted including pruritus [28, 29]. Increased plasma LDL cholesterol and decreased HDL cholesterol were also evident in these studies, suggesting that cardiovascular outcomes should be evaluated in patients under long-term treatment with OCA. OCA showed efficacy in the treatment of PBC, which is currently treated with ursodeoxycholic acid [30]. Thus, FXR was shown to be a therapeutic target for the development of drugs to treat liver diseases in humans. In mouse models, FXR agonist [31] and antagonist [25] were found to modulate metabolic diseases.

The above studies suggest that intestinal FXR could be a target for the treatment of metabolic diseases as revealed by the correlation between levels of the FXR antagonist T-β-MCA, FXR signaling and obesity, insulin resistance and NAFLD. To this end, a derivative of T-β-MCA, glycine-β-muricholic acid (Gly-MCA), was synthesized based on in silico modeling of T-β-MCA binding to the FXR ligand-binding domain [25]. Gly-MCA was resistant to BSH and stable in the intestine. Oral administration of Gly-MCA decreased FXR signaling in the ileum and decreased HFD-induced and genetic (ob/ob mice) obesity, insulin resistance and NAFLD [25]. Thus, Gly-MCA mimicked the findings with tempol and antibiotic treatment and the intestine-specific Fxr-null mice. Furthermore, Gly-MCA, was associated with decreased serum ceramides and the favorable metabolic phenotypes; the positive metabolic effects of Gly-MCA were reversed by the injection of ceramides or by the administration of the FXR agonist GW4064 [25].

The question arises as to the long-term consequences of FXR inhibition in the intestine. Notably, does lack of FXR signaling in the intestine alter the enterohepatic transport of BA? However, intestine-specific Fxr-null mice and wild-type mice treated with Gly-MCA still have similar BA pool sizes, although there are some changes in BA compositions, thus indicating that the enterohepatic transport is operational in the absence of FXR expression in the intestine [25]. It is not obvious whether these changes in BA composition might have deleterious consequences after long-term FXR inhibition.

An intestine-restricted FXR agonist, fexeramine, was found to cause lower weight gain, decreased insulin resistance, and lower steatosis in mice fed on HFD [31]. Fexeramine-treated mice also exhibited increased adipose beiging. While the beneficial metabolic effects are similar to those found with the FXR antagonist Gly-MCA, the mechanism is quite distinct [25]. Fexeramine requires almost tenfold higher oral dosing than does Gly-MCA, 100 mg/kg for fexeramine vs. 10 mg/kg for Gly-MCA. While Gly-MCA mediates its effect through direct modulation of intestinal FXR and ceramide production, fexeramine appears to require TGR5 as revealed by the use of Tgr5 -null mice [31]. Altered composition of BA metabolites in liver of fexeramine-treated, HFD-fed mice, which results from the induction of FGF15 and suppression of CYP7A1-mediated BA synthesis and transport, may activate TGR5 in the intestine or other sites of expression. Unlike fexaramine, Gly-MCA had no effects on intestinal TGR5-cAMP-GLP1 signaling in vivo, and the brown and beige fat TGR5-cAMP-DIO2 pathway. Luciferase reporter gene assays further demonstrated that Gly-MCA does not activate TGR5 signaling. Thus, the metabolic improvements after Gly-MCA administration were largely due to the specific inhibition of the intestinal FXR-ceramide axis. While this pathway may also be a viable means to treat metabolic disease, a high-affinity, intestine-restricted FXR agonist needs to be developed.

The safety of any FXR agonist or antagonist also needs to be considered. Chronic activation of FXR in transgenic constitutively-activated FXR mice resulted in liver toxicity and growth delay, suggesting that treatment with chronic FXR-activating agents’ may lead to unwanted side effects [32]. To this end, whole body Fxr -null mice had a high incidence of liver tumors including hepatocellular adenoma, carcinoma and even hepatocholangiocellular carcinoma as compared to their wild-type counterparts [33, 34]. Fxr -null mice also have increased intestinal cancer [35]. Mice lacking expression of FXR in the liver are resistant to spontaneous liver cancer, but more susceptible to CA-induced liver cancer than wild-type mice [36]. Mice lacking FXR expression specifically in the liver, have increased in spontaneous liver cancer, but when treated with CA have increased liver tumors compared to control wild-type mice [36]. Long-term data from intestine-specific Fxr-null mice has not yet been collected. Thus, antagonists will be used chronically to treat metabolic disease, should not inhibit hepatic FXR. Intestinal FXR is a promising target for the treatment of metabolic disease; it is vital that any FXR antagonist must be restricted to the intestine, since inhibition of hepatic FXR could lead to cholestasis and even liver cancer.

In summary, Gly-MCA is a potential candidate for the treatment of metabolic disease since it inhibits FXR in the intestine but does not inhibit hepatic FXR [25]. Gly-MCA is also affective at oral administration with doses of 10 mg/kg, which is equivalent to an approximate dose of 1 gm for a 100 kg human. Further studies are warranted in order to determine the safety of this compound and other intestine-selective FXR inhibitors in mice and other animal models.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

A.D. Patterson owns equity in Heliome Biotech. This financial interest has been reviewed by the University’s Individual Conflict of Interest Committees and is currently being managed by the University.

References

- 1.Seol W, Choi HS, Moore DD: Isolation of proteins that interact specifically with the retinoid X receptor: two novel orphan receptors. Mol Endocrinol 1995; 9: 72–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman BM, Goode E, Chen J, Oro AE, Bradley DJ, Perlmann T, Noonan DJ, Burka LT, McMorris T, Lamph WW, Evans RM, Weinberger C: Identification of a nuclear receptor that is activated by farnesol metabolites. Cell 1995; 81: 687–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parks DJ, Blanchard SG, Bledsoe RK, Chandra G, Consler TG, Kliewer SA, Stimmel JB, Willson TM, Zavacki AM, Moore DD, Lehmann JM: Bile acids: natural ligands for an orphan nuclear receptor. Science 1999; 284: 1365–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suh JM, Yu CT, Tang K, Tanaka T, Kodama T, Tsai MJ, Tsai SY: The expression profiles of nuclear receptors in the developing and adult kidney. Mol Endocrinol 2006; 20: 3412–3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang T, Wang XX, Scherzer P, Wilson P, Tall-man J, Takahashi H, Li J, Iwahashi M, Sutherland E, Arend L, Levi M: Farnesoid X receptor modulates renal lipid metabolism, fibrosis, and diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 2007; 56: 2485–2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinal CJ, Tohkin M, Miyata M, Ward JM, Lambert G, Gonzalez FJ: Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell 2000;102: 731–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Hagedorn CH, Wang L: Role of nuclear receptor SHP in metabolism and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011; 1812: 893–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson PA: Role of the intestinal bile acid transporters in bile acid and drug disposition. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2011; 201: 169–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ: Bile acids as hormones: the FXR-FGF15/19 pathway. Dig Dis 2015; 33: 327–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi M, Moschetta A, Bookout AL, Peng L, Umetani M, Holmstrom SR, Suino-Powell K, Xu HE, Richardson JA, Gerard RD, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA: Identification of a hormonal basis for gallbladder filling. Nat Med 2006; 12: 1253–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aqel B, DiBaise JK: Role of the gut microbiome in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr Clin Pract 2015; 30: 780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boursier J, Diehl AM: Implication of gut microbiota in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS Pathog 2015; 11:e1004559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arora T, Backhed F: The gut microbiota and metabolic disease: current understanding and future perspectives. J Intern Med 2016; 280: 339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell JB, Xavier S, DeLuca AM, Sowers AL, Cook JA, Krishna MC, Hahn SM, Russo A: A low molecular weight antioxidant decreases weight and lowers tumor incidence. Free Radic Biol Med 2003; 34: 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li F, Pang X, Krausz KW, Jiang C, Chen C, Cook JA, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB, Gonzalez FJ, Patterson AD: Stable isotope- and mass spectrometry-based metabolomics as tools in drug metabolism: a study expanding tempol pharmacology. J Proteome Res 2013; 12: 1369–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li F, Jiang C, Krausz KW, Li Y, Albert I, Hao H, Fabre KM, Mitchell JB, Patterson AD, Gonzalez FJ: Microbiome remodelling leads to inhibition of intestinal farnesoid X receptor signalling and decreased obesity. Nat Commun 2013; 4: 2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang C, Xie C, Li F, Zhang L, Nichols RG, Krausz KW, Cai J, Qi Y, Fang ZZ, Takahashi S, Tanaka N, Desai D, Amin SG, Albert I, Patterson AD, Gonzalez FJ: Intestinal farnesoid x receptor signaling promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest 2015; 125: 386–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unger RH: Lipotoxic diseases. Annu Rev Med 2002; 53: 319–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chaurasia B, Summers SA: Ceramides – lipotoxic inducers of metabolic disorders. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2015; 26: 538–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kremer GJ, Atzpodien W, Schnellbacher E: Plasma glycosphingolipids in diabetics and normals. Klin Wochenschr 1975; 53: 637–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Promrat K, Longato L, Wands JR, de la Monte SM: Weight loss amelioration of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis linked to shifts in hepatic ceramide expression and serum ceramide levels. Hepatol Res 2011; 41: 754–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahammed SK, Chowdhury A: Insulin resistance and ‘lipotoxic liver diseases’. Trop Gastroenterol 2013; 34: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holland WL, Adams AC, Brozinick JT, Bui HH, Miyauchi Y, Kusminski CM, Bauer SM, Wade M, Singhal E, Cheng CC, Volk K, Kuo MS, Gordillo R, Kharitonenkov A, Scherer PE: An FGF21-adiponectin-ceramide axis controls energy expenditure and insulin action in mice. Cell Metab 2013; 17: 790–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen P, Spiegelman BM: Brown and beige fat: molecular parts of a thermogenic machine. Diabetes 2015; 64: 2346–2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang C, Xie C, Lv Y, Li J, Krausz KW, Shi J, Brocker CN, Desai D, Amin SG, Bisson WH, Liu Y, Gavrilova O, Patterson AD, Gonzalez FJ: Intestine-selective farnesoid X receptor inhibition improves obesity-related metabolic dysfunction. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pellicciari R, Fiorucci S, Camaioni E, Clerici C, Costantino G, Maloney PR, Morelli A, Parks DJ, Willson TM: 6alpha-ethyl-chenodeoxycholic acid (6-ECDCA), a potent and selective FXR agonist endowed with anticholestatic activity. J Med Chem 2002; 45: 3569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Copple BL, Li T: Pharmacology of bile acid receptors: evolution of bile acids from simple detergents to complex signaling molecules. Pharmacol Res 2016; 104: 9–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanyal AJ: Use of farnesoid X receptor agonists to treat nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis 2015; 33: 426–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, Lavine JE, Van Natta ML, Abdelmalek MF, Chalasani N, Dasarathy S, Diehl AM, Hameed B, Kowdley KV, McCullough A, Terrault N, Clark JM, Tonascia J, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Doo E; NASH Clinical Research Network: Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 385: 956–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silveira MG, Lindor KD: Obeticholic acid and budesonide for the treatment of primary biliary cirrhosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2014; 15: 365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang S, Suh JM, Reilly SM, Yu E, Osborn O, Lackey D, Yoshihara E, Perino A, Jacinto S, Lukasheva Y, Atkins AR, Khvat A, Schnabl B, Yu RT, Brenner DA, Coulter S, Liddle C, Schoonjans K, Olefsky JM, Saltiel AR, Downes M, Evans RM: Intestinal FXR agonism promotes adipose tissue browning and reduces obesity and insulin resistance. Nat Med 2015; 21: 159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng Q, Inaba Y, Lu P, Xu M, He J, Zhao Y, Guo GL, Kuruba R, de la Vega R, Evans RW, Li S, Xie W: Chronic activation of FXR in transgenic mice caused perinatal toxicity and sensitized mice to cholesterol toxicity. Mol Endocrinol 2015; 29: 571–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim I, Morimura K, Shah Y, Yang Q, Ward JM, Gonzalez FJ: Spontaneous hepatocarcinogenesis in farnesoid X receptor-null mice. Carcinogenesis 2007; 28: 940–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang F, Huang X, Yi T, Yen Y, Moore DD, Huang W: Spontaneous development of liver tumors in the absence of the bile acid receptor farnesoid X receptor. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 863–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maran RR, Thomas A, Roth M, Sheng Z, Esterly N, Pinson D, Gao X, Zhang Y, Ganapathy V, Gonzalez FJ, Guo GL: Farnesoid X receptor deficiency in mice leads to increased intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and tumor development. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2009; 328: 469–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kong B, Zhu Y, Li G, Williams JA, Buckley K, Tawfik O, Luyendyk JP, Guo GL: Mice with hepatocyte-specific FXR deficiency are resistant to spontaneous but susceptible to cholic acid-induced hepatocarcinogenesis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2016; 310:G295–G302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]