Abstract

Background

Childhood misfortune is associated with late-life depressive symptoms, but it remains an open question whether adult socioeconomic and relational reserves could reduce the association between childhood misfortune and late-life depressive symptoms.

Methods

Using the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), data from 8'357 individuals (35'260 observations) aged 50–96 years and living in 11 European countries were used to examine associations between three indicators of childhood misfortune (adverse childhood events, poor childhood health, and childhood socioeconomic circumstances) and late-life depressive symptoms. Subsequently, we tested whether these associations were mediated by education, occupational position, the ability to make ends meet, and potential or perceived relational reserves; that is family members or significant others who can provide help in case of need, respectively. Analyses were stratified by gender and adjusted for confounding and control variables.

Results

Adult socioeconomic reserves partly mediated the associations between adverse childhood events, poor childhood health and late-life depressive symptoms. The associations with the third indicator of childhood misfortune (childhood socioeconomic circumstances) were fully mediated by adult socioeconomic reserves in men, and partly mediated in women. None of the associations were mediated by relational reserves. However, perceived relational reserves were associated with fewer late-life depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

Childhood socioeconomic disadvantage can be mitigated more easily over the life course than adverse childhood events and poor childhood health, especially in men. Perceived relational reserves work primarily as a protective force against late-life depressive symptoms and may be particularly important in the context of the cumulative effect of childhood adversities.

Keywords: Late-life depression, Childhood misfortune, Life course, Reserves, Europe

Highlights

-

•

Socioeconomic reserves can mediate the effect of childhood socioeconomic disadvantage on late-life depressive symptoms.

-

•

Education turned out to be the strongest mediator.

-

•

Findings showed a lasting effect of adverse childhood experiences and poor childhood health on late-life depressive symptoms.

-

•

Relational reserves did not mediate the effect of any of the childhood misfortune indicators on late-life depressive symptoms.

-

•

Relational reserves were associated with fewer late-life depressive symptoms suggesting a potential protective function.

1. Introduction

Depression is the most common mental health problem in late life with a substantial increase among the oldest old (Luppa et al., 2012). An important risk factor for mental health is early-life stress (Schwarzbach, Luppa, Forstmeier, Konig, & Riedel-Heller, 2014). Studies have shown that late-life depression is associated with disadvantaged childhood socioeconomic circumstances (CSC) (Angelini, Howdon, & Mierau, 2018), adverse childhood experiences (ACE) (Ege, Messias, Thapa, & Krain, 2015), and poor childhood health (Arpino, Guma, & Julia, 2018). However, whether this effect of childhood misfortune on late-life depressive symptoms can be mitigated by socioeconomic and relational reserves over the life course is still unclear. As conceptualized by Cullati, Kliegel, and Widmer (2018), different types of reserves (e.g. cognitive, economical, relational, etc.) can be assembled over the life course. These reserves need to be developed and maintained by individuals. Their availability has been shown to affect an individual’s vulnerability to life course stressors (Ihle et al., 2016). Relational reserves in particular are at stakes for promoting physical and mental health, increasing individual resilience against non-normative events by activating resources from others (family, close friends) in case of need. Therefore, these reserves might carry an important protective function against deterioration of late-life mental health.

First, socioeconomic reserves acquired in young and late adulthood (Galobardes, Shaw, Lawlor, Lynch, & Davey Smith, 2006) may alleviate the effect of childhood misfortune on late-life depressive symptoms by providing individuals with resources derived from education and occupational position. However, previous findings on potential mediation by adult socioeconomic reserves are inconsistent. European studies showed either no mediating effect by adult socioeconomic factors (Angelini et al., 2018) or a mediating effect of adult educational attainments on the association between CSC and late-life depressive symptoms, but not on the association between childhood health and late-life depressive symptoms (Arpino et al., 2018).

Second, social relations could reduce the effect of childhood misfortune on late-life depressive symptoms. In the present study, we focus on social relations conceptualized as reserves, which can be formed, maintained and restored over the life course. Relational reserves are the latent matrix of relationships established by active exchanges and reciprocity with family members and friends (e.g. doing someone a favor) (Widmer, 2016). Over the life course, these interactions form stable convoys of significant others, likely to stand by someone’s side if needed (Antonucci & Akiyama, 1995). Individuals are likely to accumulate such relational reserves over time. Relational reserves are potential resources which can be activated in case of need (e.g. adverse life event) to receive help or support (Cullati et al., 2018). Hence, the study included variables of potential relational reserves (close family relations) which are known to incorporate intimate positions in the personal convoy of significant others (Antonucci & Akiyama, 1995). Further, to integrate potential help which can be quickly activated in case of need, we integrated a variable of perceived relational reserves (“If I were in trouble, there are people in this area who would help me”). People on whom individuals can rely in times of need can help to delay or modify processes of health decline in late life, such as depressive symptoms (Cullati et al., 2018). Although a systematic review on social relations and depression in late life has shown that social support of good quality can buffer depressive symptoms in late life (Schwarzbach et al., 2014), up to now, it is not known if relational reserves can mediate the effect of an adverse start in life on late-life mental health.

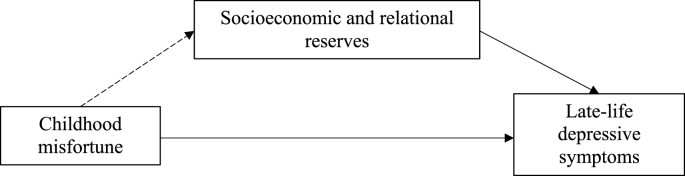

We hypothesize, that socioeconomic and relational reserves acquired over the life course could alleviate a bad start in life and reduce its effect on late-life depressive symptoms. Therefore, the present study examined whether adult socioeconomic and relational reserves mediate the associations between three childhood misfortune indicators and late-life depressive symptoms (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized mediating effect of socioeconomic and relational reserves. The dashed arrow represents a theoretical link which was not analyzed in the present study.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

Data were drawn from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) (Börsch-Supan et al., 2013) which took place every two years between 2004 (wave 1) and 2015 (wave 6). Depressive symptoms, adult socioeconomic reserves and potential relational reserves were assessed at waves 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6. Information on childhood misfortune was assessed during SHARELIFE (retrospective survey on life histories in wave 3). The question on perceived relational reserves (“If I were in trouble, there are people in this area who would help me”) was only integrated in waves 5 and 6. In this study, participants were included if (A) they participated in the third wave, (B) provided at least one measurement of depressive symptoms in any of the other five waves, and (C) provided at least one measurement of relational reserves in waves 5 and 6. The final sample included 8357 individuals (35,260 observations) aged 50–96 years and living in 11 European countries.1 Participants contributed an average of 4.2 observations to the model.

2.2. Outcome: depressive symptoms

The EURO-D scale is a validated measure of late-life depressive symptoms, which permits comparing depressive symptoms across European countries (Copeland et al., 2004; Kok, Avendano, Bago d’Uva, & Mackenbach, 2012; Prince et al., 1999). It includes 12 items: Depression, Pessimism, Wishing death, Guilt, Sleep, Interest, Irritability, Appetite, Fatigue, Concentration, Enjoyment, and Tearfulness. Depressive symptoms were measured in all SHARE waves, except wave 3. In the analysis, depressive symptoms are treated as a continuous variable.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Childhood misfortune

Following a multidimensional approach of childhood adversities (Ferraro, Schafer, & Wilkinson, 2016; Pearlin, Schieman, Fazio, & Meersman, 2005), three self-reported indicators of childhood misfortune were created: ACE (no ACE, 1 ACE, 2 or more ACE), poor childhood health (no childhood health problems vs. 1 or more childhood health problems), and a CSC index with five categories ranging from “most disadvantaged” to “most advantaged”. These retrospective measures of SHARE were found to reflect well the experienced childhood circumstances (Havari & Mazzonna, 2015; Lacey, Belcher, & Croft, 2012) though another study suggested that recalled life-course data tended to underestimate real childhood circumstances (Batty, Lawlor, Macintyre, Clark, & Leon, 2005).

ACE were assessed using six indicators of traumatic events occurring between birth and the age of 18 (Ege et al., 2015): growing up in care (children’s home or foster family), parental death (no parental death, either father or mother, both), parental mental illness, parental drinking abuse, period of hunger, and property being taken away. These six indicators were combined, resulting in an ACE score with the categories “no ACE” (i.e., participants who only answered “no”), “1 ACE” (i.e., participants who answered “yes” once), and “2 or more ACE” (i.e., participants who answered “yes” at least twice). Participants with missing information for all six indicators were excluded.

The score for childhood health is composed of three recoded binary variables of health conditions until the age of 15 (Arpino et al., 2018): long or multiple hospitalizations, 1 or less vs. 2 or more childhood diseases (e.g., polio, asthma, meningitis, encephalitis), and none vs. 1 or more serious childhood health conditions (severe headaches, psychiatric problem, fractures, heart trouble, cancers, and physical injury that has led to permanent handicap, disability or limitation in daily life). These three indicators taken together resulted in a two-level categorical variable of “no childhood health problems” (i.e., participants who answered “no” to all indicators) and “1 or more childhood health problems” (i.e., participants who answered “yes” to at least one indicator). Participants with missing information for all three indicators were excluded.

Childhood socioeconomic circumstances were assessed by four retrospective indicators at the age of 10 (SHARELIFE; wave 3) (Wahrendorf & Blane, 2015), which are known to have long-lasting effects on adult health (Chittleborough, Baum, Taylor, & Hiller, 2006). First, the occupational position of the main breadwinner of the household during childhood was derived from the International Standard Classification of Occupations (Wahrendorf, Blane, Bartley, Dragano, & Siegrist, 2013). These 10 main occupational groups were regrouped into four skill-levels, and then dichotomized into “low” and “high” occupational position. Second, having ten books or less at home compared to having more than ten books indicated socioeconomic disadvantage (Evans, Kelley, Sikora, & Treiman, 2010). Third, household overcrowding – more than one person per room – (Marsh, 1999), was computed using the number of people living in a household and the number of rooms per household (excluding kitchen, bathrooms, and hallways). Fourth, housing quality was assessed by the presence of the following facilities: fixed bath, cold and hot water supply, inside toilet, and central heating (Dedman, Gunnell, Davey Smith, & Frankel, 2001). If the household had none of them, it was coded as “disadvantaged”. These four binary indicators served to create an index of childhood socioeconomic circumstances with five categories ranging from “most disadvantaged” to “most advantaged”. Disadvantaged CSC have been shown to predict a wide range of health indicators, including muscle strength (Cheval, Boisgontier, et al., 2018), lung function (Cheval, Chabert, et al., 2018), frailty (van der Linden et al., 2017), disability (Landös et al., 2018), and physical inactivity (Cheval, Sieber, et al., 2018).

2.3.2. Prior confounders and covariates

All models were adjusted for the following confounders: birth cohort (1919–1928, 1929–1938 [Great Depression], 1939–1945 [World War II], and After 1945) (Yang, 2007), country of residence (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland), and participant attrition by death (Boe, Balaj, Eikemo, McNamara, & Solheim, 2017).

Due to their strong association with depressive symptoms, four health status variables were included as covariates: (1) chronic disease score (less than 2 vs. 2 or more of the following conditions: stroke, heart attack, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, Parkinson’s disease, or asthma) (Huang, Dong, Lu, Yue, & Liu, 2010); (2) daily life physical activity (physically active [more than once a week] vs. physically inactive [once a week or less]) (Cheval, Sieber, et al., 2018; Lindwall, Larsman, & Hagger, 2011); (3) limitations of activities of daily living (0 vs. 1 or more) (4); limitations of instrumental activities of daily living (0 vs. 1 or more) (Ormel, Rijsdijk, Sullivan, van Sonderen, & Kempen, 2002).

2.3.3. Mediators

Adult socioeconomic reserves: Potential adult socioeconomic mediators over the life course included participants’ highest level of education, main occupational position, and the ability to make ends meet with their household income. UNESCO’s International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) was used to group participants into primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of education. The variable for participants’ main occupational position during adult life was determined in the same manner as the variable describing the main breadwinner during childhood (see 2.2.1 Childhood misfortune). Additionally, participants who had never done paid work were assigned to a separate category. The answer to the question “Thinking of your household’s total monthly income, would you say that your household is able to make ends meet?” reflected socioeconomic conditions in late-life, ranging from 1 (“with great difficulty”) to 4 (“easily”) (Litwin & Sapir, 2009). All three indicators were measured at each wave, except wave 3.

Relational reserves: Potential reserves (measured at all waves, except wave 3) included partnership status (living with a partner vs. not living with a partner) (Kamiya, Doyle, Henretta, & Timonen, 2013), number of children still alive (0 vs. 1 or more) (Grundy, van den Broek, & Keenan, 2017), and number of siblings still alive (0 vs. 1 or more) (Rajkumar et al., 2009). Perceived relational reserves were measured in wave 5 and 6 by the statement of “If I were in trouble, there are people in this area who would help me” (yes vs. no) (Schwarzbach et al., 2014).

2.4. Statistical analysis

To estimate the associations, linear mixed-effects regressions were performed (Boisgontier & Cheval, 2016). These models allow accounting for the nested structure of the data. In our case, observations (repeated measurement of depressive symptoms) were nested within participants. Moreover, linear mixed-effects regressions avoided excluding participants with missing observations, because these models do not require an equal number of observations for all participants. Analyses were stratified by gender as previous studies showed that women were at greater risk of depression than men (Djernes, 2006; Luppa et al., 2012).

Model 1 investigated the association between the three childhood misfortune indicators and late-life depressive symptoms adjusted for confounders. Age was centered at the midpoint of the sample’s age range (73 years old). To test potential mediations, adult socioeconomic indicators were added in Model 2 and relational reserves were included in Model 3. Finally, health status covariates were added in Model 4.

To formally test the mediation between childhood misfortune and depressive symptoms through adult socioeconomic reserves, 5000 bias-corrected accelerated bootstraps with 95% confidence intervals were reported for the difference in the coefficient estimates of the childhood misfortune effects between the model without the mediator (i.e., total effect) and the model with the mediator (i.e., direct effect). To take into account the structure of the data, an R function was created to resample individual and observation-level model parameters instead of participants.

To test a potential mediation by relational reserves independently of adult socioeconomic indicators, a supplementary analysis was performed adding the relational reserves directly in Model 2 (see supplementary material – Table S1). Statistical assumptions associated with linear mixed models, including normality of the residuals, linearity, multicollinearity (variance inflation factors), and undue influence (Cook’s distances), were met.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive results

Details on the 8357 participants’ characteristics (4909 women) can be found in Table 1. Symptoms of depression increased with age, with a faster increase for men (b = 0.50) than for women (b = 0.32).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

| Women |

Men |

|

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 62.0 (8.882) | 61.9 (8.419) |

| Countries | ||

| Austria | 198 (4.0) | 124 (3.6) |

| Belgium | 614 (12.5) | 487 (14.1) |

| Czech Republic | 383 (7.8) | 176 (5.1) |

| Denmark | 555 (11.3) | 410 (11.9) |

| France | 509 (10.4) | 356 (10.3) |

| Germany | 298 (6.1) | 246 (7.1) |

| Greece | 1 (0.02) | 2 (0.06) |

| Italy | 582 (11.9) | 426 (12.4) |

| Netherlands | 526 (10.7) | 368 (10.7) |

| Poland | 9 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) |

| Spain | 482 (9.8) | 285 (8.3) |

| Sweden | 432 (8.8) | 330 (9.6) |

| Switzerland | 320 (6.5) | 235 (6.8) |

| Birth cohort | ||

| After 1945 | 2201 (44.8) | 1501 (43.5) |

| Between 1919 and 1928 | 408 (8.3) | 235 (6.8) |

| Between 1929 and 1938 | 1148 (23.4) | 825 (24.0) |

| Between 1939 and 1945 | 1152 (23.5) | 887 (25.7) |

| Attrition | ||

| No dropout | 4797 (97.3) | 3336 (96.8) |

| Death | 112 (2.3) | 112 (3.3) |

| Childhood socioeconomic circumstances (CSC) at age 10 | ||

| Most disadvantaged | 708 (14.4) | 480 (13.9) |

| Disadvantaged | 1147 (23.4) | 773 (22.4) |

| Middle | 1730 (35.2) | 1188 (34.5) |

| Advantaged | 999 (20.4) | 774 (22.5) |

| Most advantaged | 325 (6.6) | 233 (6.8) |

| Adverse childhood events (ACE) score at age 18 | ||

| No ACE | 3659 (74.5) | 2558 (74.2) |

| 1 ACE | 1003 (20.4) | 693 (20.1) |

| 2 or more ACE | 247 (5.0) | 197 (5.7) |

| Childhood health problems until age 15 | ||

| No problems | 3564 (72.6) | 2473 (71.7) |

| 1 or more | 1345 (27.4) | 975 (28.3) |

| Education | ||

| Primary | 1419 (28.9) | 750 (21.8) |

| Secondary | 2527 (51.5) | 1766 (51.2) |

| Tertiary | 963 (19.6) | 932 (27.0) |

| Main occupational position | ||

| High-skilled | 930 (19.0) | 1297 (37.6) |

| Low-skilled | 3466 (70.6) | 2133 (61.9) |

| Never worked | 513 (10.5) | 18 (0.5) |

| Ability to make ends meet with household income | ||

| Easily | 2021 (41.2) | 1770 (51.3) |

| Fairly easily | 1485 (30.3) | 1017 (29.5) |

| With some difficulty | 1002 (20.4) | 489 (14.2) |

| With great difficulty | 401 (8.2) | 172 (5.0) |

| Potential relational reserves | ||

| Partnership status | ||

| Not living with a partner | 1876 (38.2) | 759 (22.0) |

| Living with a partner | 3033 (61.8) | 2689 (78.0) |

| Number of children alive | ||

| No children | 4438 (90.4) | 3049 (88.4) |

| 1 or more | 471 (9.6) | 399 (11.6) |

| Number of siblings alive | ||

| No siblings | 3347 (68.2) | 2297 (66.6) |

| 1 or more | 1562 (31.8) | 1151 (33.4) |

| Perceived relational reserves | ||

| Help available in case of need | ||

| No | 522 (10.6) | 397 (11.5) |

| Yes | 4387 (89.4) | 3051 (88.5) |

| Activities of daily living (ADL) | ||

| No ADL limitations | 4598 (93.7) | 3299 (95.7) |

| 1 or more ADL limitations | 311 (6.3) | 149 (4.3) |

| Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) | ||

| No IADL limitations | 4244 (86.5) | 3246 (94.1) |

| 1 or more IADL limitations | 665 (13.6) | 202 (5.9) |

| Physical activity | ||

| High (more than once a week) | 3608 (73.5) | 2791 (81.0) |

| Low (once a week or less) | 1301 (26.5) | 657 (19.0) |

| Number of chronic diseases | ||

| 2 or more | 2250 (45.8) | 1285 (37.3) |

| Less than 2 | 2659 (54.2) | 2163 (62.7) |

| Depressive symptoms, mean (SD) | 2.594 (2.269) | 1.608 (1.764) |

3.2. Association between childhood misfortune and late-life depressive symptoms

ACE and childhood health were associated with higher levels of late-life depressive symptoms, but the coefficients were generally lower for men than for women (Model 1).

Among women, results showed a gradient across CSC categories: the more advantaged CSC a woman grew up in, the lower her risk for late-life depression symptoms. For men, only the CSC categories “middle”, “advantaged” and “most advantaged” were associated with late-life depressive symptoms. A gradient among these three categories was observable, but again less pronounced than for women.

3.3. Mediation by adult socioeconomic reserves

In women, associations of childhood misfortune and late-life depressive symptoms were partly mediated by adult socioeconomic reserves (Table 2, Model 2). For ACE, the associations decreased by 18.9% (none vs. 1 adverse childhood experience), and 9.7% (none vs. 2 or more adverse childhood experiences). For childhood health, the association decreased by 6.6% (none vs. 1 or more childhood health problems). For CSC, the associations decreased by 64.0% (most disadvantaged vs. disadvantaged CSC), 55.4% (most disadvantaged vs. middle CSC), 62.4% (most disadvantaged vs. advantaged CSC), and 66.5% (most disadvantaged vs. most advantaged CSC). More importantly, the results of the bootstrapped 95% CI revealed that all mediating pathways were significant (Table 2, Model 2, bootstrap results).

Table 2.

Associations between childhood misfortune and late-life depressive symptoms among women.

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (95%CI) | b (95%CI) | b (95%CI) | b (95%CI) | |||||

| Women | ||||||||

| Age | 0.32 (0.25–0.40) | <0.001 | 0.32 (0.25–0.40) | <0.001 | 0.32 (0.25–0.40) | <0.001 | 0.33 (0.25–0.40) | <0.001 |

| Age2 | 0.16 (0.13–0.20) | <0.001 | 0.16 (0.13–0.20) | <0.001 | 0.16 (0.13–0.20) | <0.001 | 0.16 (0.13–0.20) | <0.001 |

| ACE score at age 18 (ref. no ACE) | ||||||||

| 1 ACE | 0.31 (0.19–0.42) | <0.001 | 0.25 (0.14–0.36) | <0.001 | 0.24 (0.13–0.35) | <0.001 | 0.21 (0.10–0.31) | <0.001 |

| 2 or more ACE | 0.62 (0.41–0.83) | <0.001 | 0.56 (0.35–0.76) | <0.001 | 0.53 (0.33–0.74) | <0.001 | 0.40 (0.20–0.59) | <0.001 |

| Childhood health problems (ref. no problems) | ||||||||

| 1 or more | 0.37 (0.27–0.48) | <0.001 | 0.35 (0.25–0.45) | <0.001 | 0.35 (0.24–0.45) | <0.001 | 0.27 (0.18–0.37) | <0.001 |

| CSC (ref. Most disadvantaged) | ||||||||

| Disadvantaged | -0.25 (-0.40–0.09) | 0.002 | -0.09 (-0.24–0.07) | 0.261 | -0.09 (-0.24–0.06) | 0.254 | -0.07 (-0.21–0.08) | 0.352 |

| Middle | -0.56 (-0.72–0.40) | <0.001 | -0.25 (-0.41–0.09) | 0.002 | -0.25 (-0.41–0.09) | 0.002 | -0.18 (-0.33–0.03) | 0.019 |

| Advantaged | -0.60 (-0.77–0.43) | <0.001 | -0.24 (-0.41–0.06) | 0.009 | -0.23 (-0.41–0.05) | 0.011 | -0.17 (-0.34–0.01) | 0.042 |

| Most advantaged | -0.67 (-0.90–0.44) | <0.001 | -0.22 (-0.46–0.01) | 0.064 | -0.23 (-0.47–0.00) | 0.053 | -0.15 (-0.37–0.08) | 0.199 |

| Education (ref. Primary) | ||||||||

| Secondary | – | -0.30 (-0.43–0.18) | <0.001 | -0.31 (-0.43–0.18) | <0.001 | -0.25 (-0.36–0.13) | <0.001 | |

| Tertiary | – | -0.35 (-0.53–0.17) | <0.001 | -0.35 (-0.52–0.17) | <0.001 | -0.23 (-0.40–0.07) | 0.006 | |

| Main occupational position (ref. High-skilled) | ||||||||

| Low-skilled | – | 0.06 (-0.08–0.20) | 0.379 | 0.06 (-0.08–0.20) | 0.386 | 0.04 (-0.08–0.17) | 0.504 | |

| Never worked | – | -0.10 (-0.30–0.11) | 0.35 | -0.08 (-0.28–0.12) | 0.423 | -0.16 (-0.34–0.03) | 0.108 | |

| Ability to make ends meet (ref. Easily) | ||||||||

| Fairly easily | – | 0.23 (0.12–0.35) | <0.001 | 0.22 (0.11–0.34) | <0.001 | 0.18 (0.07–0.28) | 0.001 | |

| With some difficulty | – | 0.71 (0.57–0.84) | <0.001 | 0.69 (0.55–0.82) | <0.001 | 0.54 (0.41–0.67) | <0.001 | |

| With great difficulty | – | 1.60 (1.41–1.79) | <0.001 | 1.57 (1.39–1.76) | <0.001 | 1.20 (1.03–1.38) | <0.001 | |

| Potential relational reserves | ||||||||

| Living with a partner (ref. Not living with a partner) | – | – | 0.03 (-0.07–0.13) | 0.503 | 0.09 (-0.01–0.18) | 0.066 | ||

| Number of children alive (ref. No children) | – | – | 0.08 (-0.08–0.24) | 0.316 | 0.08 (-0.07–0.23) | 0.279 | ||

| Number of siblings alive (ref. No children) | – | – | 0.02 (-0.07–0.12) | 0.633 | -0.00 (-0.09–0.09) | 0.977 | ||

| Perceived relational reserves | ||||||||

| Yes, help available in case of need (ref. No help available) | – | – | -0.44 (-0.59–0.29) | <0.001 | -0.41 (-0.55–0.28) | <0.001 | ||

| 1 or more ADL limitations (ref. No ADL limitations) | – | – | – | 0.45 (0.25–0.64) | <0.001 | |||

| 1 or more IADL limitations (ref. No IADL limitations) | – | – | – | 0.85 (0.70–0.99) | <0.001 | |||

| Low physical activity (ref. High physical activity) | – | – | – | 0.43 (0.32–0.53) | <0.001 | |||

| Less than 2 chronic diseases (ref. 2 or more chronic diseases) | – | – | – | -0.60 (-0.69–0.50) | <0.001 | |||

| Bootstrap of the mediation by adult socioeconomic reserves (difference between total and direct effect) | ||||||||

| ACE score at age 18 (ref. no ACE) | ||||||||

| 1 ACE | 95% CI (0.055; 0.067) | |||||||

| 2 or more ACE | 95% CI (0.059; 0.077) | |||||||

| Childhood health problems (ref. no problems) | ||||||||

| 1 or more | 95% CI (0.020; 0.030) | |||||||

| CSC (ref. Most disadvantaged) | ||||||||

| Disadvantaged | 95% CI (0.141; 0.176) | |||||||

| Middle | 95% CI (0.272; 0.342) | |||||||

| Advantaged | 95% CI (0.320; 0.409) | |||||||

| Most advantaged | 95% CI (0.382; 0.505) | |||||||

Abbreviations: CSC, childhood socioeconomic circumstances, ACE, adverse childhood events; ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; CI, confidence interval.

All models are adjusted for confounders: birth cohort, country of residence, attrition.

Separate analyses for each mediator showed that education and the ability to make ends meet contributed equally strongly to the reduction of the association between CSC and late-life depressive symptoms among women (about 37%), with occupational position being the weakest mediator (about 8%). Furthermore, there was a gradient regarding education and the ability to make ends meet, with a decreasing risk of late-life depressive symptoms for women with higher education and an increasing risk of late-life depressive symptoms for women who had greater financial difficulty.

In men, ACE and childhood health were partly mediated, whereas CSC was fully mediated by adult socioeconomic reserves (Table 3, Model 2). For ACE, the associations decreased by 21.9% (none vs. 1 adverse childhood experience), and 8.7% (none vs. 2 or more adverse childhood experiences). For childhood health, the association decreased by 6.2% (none vs. 1 or more childhood health problems). For CSC, the association of most disadvantaged vs. middle CSC showed a total decrease, while the decrease of most disadvantaged vs. advantaged CSC, and of most disadvantaged vs. most advantaged CSC was 85.0% and 87.3% respectively. Again, results of the bootstrapped 95% CI revealed that all mediating pathways were significant (Table 3, Model 2, bootstrap results).

Table 3.

Associations between childhood misfortune and late-life depressive symptoms among men.

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (95%CI) | b (95%CI) | b (95%CI) | b (95%CI) | |||||

| Men | ||||||||

| Age | 0.50 (0.43–0.57) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.43–0.57) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.42–0.57) | <0.001 | 0.48 (0.41–0.55) | <0.001 |

| Age2 | 0.19 (0.15–0.22) | <0.001 | 0.19 (0.15–0.22) | <0.001 | 0.19 (0.15–0.22) | <0.001 | 0.18 (0.15–0.22) | <0.001 |

| ACE score at age 18 (ref. no ACE) | ||||||||

| 1 ACE | 0.24 (0.12–0.35) | <0.001 | 0.19 (0.07–0.30) | 0.001 | 0.18 (0.07–0.29) | 0.002 | 0.14 (0.04–0.25) | 0.008 |

| 2 or more ACE | 0.40 (0.20–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.36 (0.17–0.55) | <0.001 | 0.36 (0.17–0.55) | <0.001 | 0.30 (0.12–0.48) | 0.001 |

| Childhood health problems (ref. no problems) | ||||||||

| 1 or more | 0.16 (0.05–0.26) | 0.003 | 0.15 (0.05–0.24) | 0.004 | 0.14 (0.04–0.24) | 0.006 | 0.10 (0.00–0.19) | 0.041 |

| CSC (ref. Most disadvantaged) | ||||||||

| Disadvantaged | 0.02 (-0.14–0.18) | 0.805 | 0.10 (-0.05–0.26) | 0.199 | 0.09 (-0.06–0.25) | 0.253 | 0.10 (-0.05–0.24) | 0.199 |

| Middle | -0.17 (-0.33–0.01) | 0.032 | -0.00 (-0.16–0.15) | 0.954 | -0.01 (-0.17–0.15) | 0.907 | 0.02 (-0.13–0.17) | 0.805 |

| Advantaged | -0.24 (-0.41–0.07) | 0.005 | -0.04 (-0.21–0.14) | 0.685 | -0.04 (-0.22–0.13) | 0.64 | -0.03 (-0.20–0.13) | 0.717 |

| Most advantaged | -0.28 (-0.50–0.05) | 0.015 | -0.04 (-0.27–0.19) | 0.764 | -0.04 (-0.27–0.19) | 0.742 | -0.01 (-0.23–0.21) | 0.913 |

| Education (ref. Primary) | ||||||||

| Secondary | – | -0.19 (-0.32–0.06) | 0.005 | -0.18 (-0.31–0.05) | 0.006 | -0.17 (-0.29–0.05) | 0.007 | |

| Tertiary | – | -0.24 (-0.40–0.08) | 0.004 | -0.23 (-0.39–0.07) | 0.006 | -0.18 (-0.33–0.03) | 0.021 | |

| Main occupational position (ref. High-skilled) | ||||||||

| Low-skilled | – | 0.04 (-0.06–0.15) | 0.445 | 0.04 (-0.07–0.14) | 0.498 | 0.01 (-0.09–0.11) | 0.79 | |

| Never worked | – | 0.94 (0.32–1.55) | 0.003 | 0.89 (0.28–1.51) | 0.004 | 0.46 (-0.12–1.05) | 0.121 | |

| Ability to make ends meet (ref. Easily) | ||||||||

| Fairly easily | – | 0.26 (0.15–0.37) | <0.001 | 0.24 (0.13–0.34) | <0.001 | 0.19 (0.08–0.29) | <0.001 | |

| With some difficulty | – | 0.60 (0.45–0.74) | <0.001 | 0.56 (0.42–0.71) | <0.001 | 0.41 (0.27–0.54) | <0.001 | |

| With great difficulty | – | 1.24 (1.02–1.46) | <0.001 | 1.18 (0.96–1.40) | <0.001 | 0.94 (0.73–1.15) | <0.001 | |

| Potential relational reserves | ||||||||

| Living with a partner (ref. Not living with a partner) | – | – | -0.18 (-0.30–0.07) | 0.002 | -0.14 (-0.25–0.04) | 0.009 | ||

| Number of children alive (ref. No children) | – | – | -0.01 (-0.16–0.14) | 0.923 | 0.00 (-0.14–0.15) | 0.949 | ||

| Number of siblings alive (ref. No children) | – | – | 0.02 (-0.08–0.11) | 0.715 | 0.00 (-0.09–0.09) | 0.938 | ||

| Perceived relational reserves | ||||||||

| Yes, help available in case of need (ref. No help available) | – | – | -0.34 (-0.48–0.20) | <0.001 | -0.28 (-0.41–0.14) | <0.001 | ||

| 1 or more ADL limitations (ref. No ADL limitations) | – | – | – | 0.55 (0.32–0.78) | <0.001 | |||

| 1 or more IADL limitations (ref. No IADL limitations) | – | – | – | 0.74 (0.53–0.95) | <0.001 | |||

| Low physical activity (ref. High physical activity) | – | – | – | 0.38 (0.27–0.50) | <0.001 | |||

| Less than 2 chronic diseases (ref. 2 or more chronic diseases) | – | – | – | -0.51 (-0.60–0.42) | <0.001 | |||

| Bootstrap of the mediation by adult socioeconomic reserves | ||||||||

| ACE score at age 18 (ref. no ACE) | ||||||||

| 1 ACE | 95% CI (0.045; 0.060) | |||||||

| 2 or more ACE | 95% CI (0.026; 0.042) | |||||||

| Childhood health problems (ref. no problems) | ||||||||

| 1 or more | 95% CI (0.004; 0.015) | |||||||

| CSC (ref. Most disadvantaged) | ||||||||

| Disadvantaged | – | |||||||

| Middle | 95% CI (0.135; 0.200) | |||||||

| Advantaged | 95% CI (0.165; 0.247) | |||||||

| Most advantaged | 95% CI (0.187; 0.297) | |||||||

Abbreviations: CSC, childhood socioeconomic circumstances, ACE, adverse childhood events; ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; CI, confidence interval.

All models are adjusted for confounders: birth cohort, country of residence, attrition.

Separately analyzing each mediator revealed that the associations between CSC and late-life depressive symptoms among men were primarily mediated by education (about 68%), then by the ability to make ends meet (about 47%), and the weakest mediator was occupational position (about 30%). As for women, there was a gradient regarding education and the ability to make ends meet. Having never worked was associated with more symptoms of depression, but this was not robust when adjusting for health status (Model 4).

Interactions between childhood misfortune and adult socioeconomic reserves were tested and results showed no clear interactions.

3.4. The role of potential and perceived relational reserves

When adding potential and perceived relational reserves (Model 3), there was no mediation of the associations between the three childhood misfortune indicators and late-life depressive symptoms. This result was robust, when running supplementary analysis which included relational reserves without adding adult socioeconomic reserves (see Table S1). Among potential relational reserves, the number of living children and siblings was not associated with depression, irrespective of gender. Living with a partner reduced the level of late-life depression in men (not in women) and this association remained robust after adjusting for health status (Model 4). The supplementary analysis excluding socioeconomic reserves confirmed a reduced risk for late-life depressive symptoms for men living with a partner (p < 0.001), which was also true for women (p < 0.05), although to a lesser extent.

Regarding perceived relational reserves, women and men who thought that someone would be around to provide help them if they were in trouble, had a significantly lower risk for late-life depressive symptoms (p < 0.001) compared to those who had nobody. This association between perceived relational reserves and depressive symptoms was robust after adjusting for health status (Model 4). Moreover, this association was also found in the supplementary analysis with a slightly stronger negative effect, indicating a lower risk of late-life depressive symptoms among women.

Interactions between childhood misfortune and relational reserves were tested and the results showed no clear interactions.

4. Discussion

This study investigated whether adult socioeconomic and relational reserves mediated the association between childhood misfortune and late-life depressive symptoms. Results confirmed the long-term association between childhood misfortune and a greater number of late-life depressive symptoms (Arpino et al., 2018; Ege et al., 2015). The associations of ACE and poor childhood health with late-life depressive symptoms were partly mediated by adult socioeconomic reserves. However, the associations of CSC with late-life depressive symptoms were fully mediated by adult socioeconomic reserves for men, and partly mediated for women. Neither potential nor perceived relational reserves mediated the association between childhood misfortune and late-life depressive symptoms.

Among men, the strongest mediator was the highest educational level achieved, followed by the ability to make ends meet, and the weakest mediator was the occupational position. For women, the mediation was less pronounced, with education and ability to make ends meet contributing equally to the mediation. This result is in line with previous results showing a stronger link between CSC and late-life depressive symptoms for women than for men (Angelini et al., 2018). In contrast to our results, Angelini et al., 2018 did not find that adult socioeconomic reserves explained the association between CSC and depressive symptoms (Angelini et al., 2018). However, they used annual household income as an indicator of adult socioeconomic status, which means that the results of both studies are not necessarily contradicting, depending on how the annual household income is linked to the main occupational position.

Moreover, our findings supported the hypothesis that education can mitigate the negative effect of disadvantaged childhood socioeconomic circumstances on late-life depressive symptoms (Arpino et al., 2018; Grundy et al., 2017). Education might have appeared to be the most important mediator, because it usually starts in childhood and therefore acts as a structural determinant of occupational position and income (Bol, 2015). This strengthens the critical importance of education as a long-term determining factor in inequalities of health outcomes (Cheval, Sieber, et al., 2018; Davies, Dickson, Davey Smith, van den Berg, & Windmeijer, 2018; Mirowsky & Ross, 1998). Furthermore, education could play a central role regarding late-life depressive symptoms, because both are essentially connected to cognitive processing. However, there was only a marginal difference between secondary and tertiary levels, and this effect was not as strong for the associations with ACE and childhood health, which is in line with previous findings (Arpino et al., 2018). This strengthens the need for a multidimensional approach to early-life adversities (Ferraro et al., 2016).

Previous work considered that perceived social connectedness was more important than perceived social support for health and well-being of older adults (Ashida & Heaney, 2008). Our results support this hypothesis as individuals who believed that they would receive help from someone in the area when in trouble showed a reduced risk of depressive symptoms. Among potential social reserves, only partnership status was associated with late-life depressive symptoms. While there was no effect observable in women, men living with a partner had a reduced risk for depressive symptoms. This result is in line with previous studies indicating that spousal support may be more important for men than for women in late-life mental health (Santini et al., 2016). Generally, women seem to maintain larger networks of significant others than men (Walen & Lachman, 2000). This implies that men are more vulnerable to spousal loss and its related negative consequences for health than women (Stroebe, 2001). Moreover, early adversities may promote mistrust in others, making it difficult to form and keep close social ties, especially for men (Miller et al., 2009). Our findings indicated that some of the relational reserves chosen had a protective effect on late-life depressive symptoms, but no mediating effect. Future studies should focus on qualitative personal network data and variables assessing supportive social reserves to further examine the effect of relational reserves on the association of childhood misfortune and late-life mental health. Another approach would be to hypothesize that childhood misfortune restrains the assembling of relational reserves due to difficult or inexistent family relations which usually are frequent in the personal convoy of significant others (Antonucci & Akiyama, 1995). By consequence, this lack of relational resources or a high effort to form substitute relational reserves could make individuals more vulnerable to life course adversities like mental health problems.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include a large sample size, analyses stratified by gender, a validated measure of depressive symptoms (EURO-D), and a multidimensional measure of childhood misfortune. This study also has limitations. First, even if retrospective life-course data of SHARE (wave 3) have been shown to be accurate (Havari & Mazzonna, 2015; Lacey et al., 2012), self-reported information on childhood misfortune and adult socioeconomic status (e.g. main occupational position) might still be subject to recall or social desirability bias. However, previous studies on the validity of retrospective measures of childhood social class (Batty et al., 2005) and a review on the recall of ACE (Hardt & Rutter, 2004) indicated an underestimated assessment of the data. This underlines a judicious, but nonetheless warrantable interpretation of the results. Second, the childhood misfortune indicators did not consider the exact age at which the adversities occurred and may therefore not capture childhood condition in its integrality. Hence, the differences observed between childhood misfortune indicators should be interpreted cautiously. Third, like all longitudinal studies including older adults, attrition represents a potential selection bias. By adjusting all models for attrition by death, we limited this bias. Fourth, including only participants who answered the SHARELIFE module (wave 3) resulted in a sample size reduction, which may have caused information bias on the exposure. Fifth, the measures of relational reserves may not fully reflect certain dimensions like their long term constitution, their thresholds and the circumstances in which they can be activated (Cullati et al., 2018). Sixth, it cannot be excluded that the selected sample is subject to selection bias affecting the findings. Seventh, due to the limitations of the information available in SHARE, and the limited knowledge on factors associated with reserves, we cannot exclude that an unmeasured factor might have confounded the association between the mediators and the outcome.

5. Conclusion

This study underlines the long-term association between childhood misfortune and late-life depressive symptoms. Associations of ACE and childhood health were only partly mediated by adult socioeconomic reserves. Our results suggest that the effect of some early-life adversities (e.g., disadvantaged socioeconomic circumstances) on late-life depressive symptoms are fully reversible, especially for men, whereas the effect of others can only be reduced (e.g., ACE and poor childhood health). Education turned out to be the strongest mediator of the association between CSC and late-life depressive symptoms, and more so in men than women. Relational reserves did not mediate the effect of childhood misfortune on late-life depressive symptoms. Nevertheless, perceived relational reserves were associated with fewer late-life depressive symptoms and may therefore still have a protective effect against late-life depressive symptoms among people who experienced childhood misfortune. Future studies should further investigate how perceived relational reserves interact with cumulative adversity over the life course.

Data sharing

This SHARE dataset is available at http://www.share-project.org/data-access.html.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Funding

This study was supported by the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research “LIVES – Overcoming vulnerability: Life course perspectives”, which is financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number: 51NF40-160590). Matthieu P. Boisgontier received funding from the Research Foundation Flanders (1504015N; 1501018N).

Contributors

M.v.A, M.P.B., B.C, S.C. designed the analyses. S.S. did the data management. B.C. analyzed the data. M.v.A, M.P.B., S.C., drafted the manuscript. All authors critically appraised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

This study used data provided by the SHARE study. During the SHARE study, the relevant research ethics committees in the participating countries approved the research design, and all participants provided written informed consent. For further use and analysis of the SHARE data, no ethical approval is needed.

Acknowledgements

This paper uses data from SHARE Waves 1, 2, 3 (SHARELIFE), 4, 5 and 6 (DOIs: 10.6103/SHARE.w1.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w2.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w3.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w4.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w5.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w6.600).

The SHARE data collection was primarily funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812) and FP7 (SHARE-PREP: no.211909, SHARE-LEAP: no.227822, SHARE M4: no.261982). Additional funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04–064, HHSN271201300071C) and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org).

Footnotes

It should be noted that the analysis also included Greece and Poland, but their results were not considered as they provided very low numbers of participants (see Table 1).

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100434.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Angelini V., Howdon D.D.D., Mierau J.O. Childhood socioeconomic status and late-adulthood mental health: Results from the survey on health, ageing and retirement in Europe. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018:95–104. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T.C., Akiyama H. Greenwood Press/Greenwood Publishing Group; Westport, CT, US: 1995. Convoys of social relations: Family and friendships within a life span context Handbook of aging and the family; pp. 355–371. [Google Scholar]

- Arpino B., Guma J., Julia A. Early-life conditions and health at older ages: The mediating role of educational attainment, family and employment trajectories. PLoS One. 2018;13(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashida S., Heaney C.A. Differential associations of social support and social connectedness with structural features of social networks and the health status of older adults. Journal of Aging and Health. 2008;20(7):872–893. doi: 10.1177/0898264308324626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batty G.D., Lawlor D.A., Macintyre S., Clark H., Leon D.A. Accuracy of adults' recall of childhood social class: Findings from the aberdeen children of the 1950s study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2005;59(10):898–903. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.030932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boe T., Balaj M., Eikemo T.A., McNamara C.L., Solheim E.F. Financial difficulties in childhood and adult depression in Europe. The European Journal of Public Health. 2017;27(suppl_1):96–101. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisgontier M.P., Cheval B. The anova to mixed model transition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2016;68:1004–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bol T. Has education become more positional? Educational expansion and labour market outcomes, 1985–2007. Acta Sociologica. 2015;58(2):105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan A., on behalf of the, S. C. C. T., Brandt, M., on behalf of the, S. C. C. T., Hunkler, C., on behalf of the, S. C. C. T., . . . on behalf of the, S. C. C. T Data resource profile: The survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe (SHARE) International Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;42(4):992–1001. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheval B., Boisgontier M.P., Orsholits D., Sieber S., Guessous I., Gabriel R.…Cullati S. Association of early- and adult-life socioeconomic circumstances with muscle strength in older age. Age and Ageing. 2018;47(3):398–407. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheval B., Chabert C., Orsholits D., Sieber S., Guessous I., Blane D.…Cullati S. Disadvantaged early-life socioeconomic circumstances are associated with low respiratory function in older age. Journal of Gerontology: Series A. 2018:1134–1140. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheval B., Sieber S., Guessous I., Orsholits D., Courvoisier D.S., Kliegel M.…Boisgontier M.P. Effect of early- and adult-life socioeconomic circumstances on physical inactivity. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2018;50(3):476–485. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittleborough C.R., Baum F.E., Taylor A.W., Hiller J.E. A life-course approach to measuring socioeconomic position in population health surveillance systems. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2006;60(11):981–992. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.048694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J.R.M., Beekman A.T.F., Braam A.W., Dewey M.E., Delespaul P., Fuhrer R.…Wilson K.C.M. Depression among older people in Europe: The EURODEP studies. World Psychiatry. 2004;3(1):45–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullati S., Kliegel M., Widmer E. Development of reserves over the life course and onset of vulnerability in later life. Nature Human Behaviour. 2018;2(8):551–558. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0395-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies N.M., Dickson M., Davey Smith G., van den Berg G.J., Windmeijer F. The causal effects of education on health outcomes in the UK Biobank. Nature Human Behaviour. 2018;2(2):117–125. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0279-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedman D.J., Gunnell D., Davey Smith G., Frankel S. Childhood housing conditions and later mortality in the Boyd Orr cohort. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2001;55(1):10–15. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djernes J.K. Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: A review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;113(5):372–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ege M.A., Messias E., Thapa P.B., Krain L.P. Adverse childhood experiences and geriatric depression: Results from the 2010 BRFSS. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;23(1):110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M.D.R., Kelley J., Sikora J., Treiman D.J. Family scholarly culture and educational success: Books and schooling in 27 nations. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 2010;28(2):171–197. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro K.F., Schafer M.H., Wilkinson L.R. Childhood disadvantage and health problems in middle and later life: Early imprints on physical health? American Sociological Review. 2016;81(1):107–133. doi: 10.1177/0003122415619617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B., Shaw M., Lawlor D.A., Lynch J.W., Davey Smith G. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1) Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2006;60(1):7–12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.023531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy E., van den Broek T., Keenan K. Number of children, partnership status, and later-life depression in eastern and western Europe. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2017:353–363. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J., Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havari E., Mazzonna F. Can we trust older people's statements on their childhood circumstances? Evidence from SHARELIFE. European Journal of Population. 2015;31(3):233–257. [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.Q., Dong B.R., Lu Z.C., Yue J.R., Liu Q.X. Chronic diseases and risk for depression in old age: A meta-analysis of published literature. Ageing Research Reviews. 2010;9(2):131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihle A., Mons U., Perna L., Oris M., Fagot D., Gabriel R. The relation of obesity to performance in verbal abilities, processing speed, and cognitive flexibility in old age: The role of cognitive reserve. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2016;42(1–2):117–126. doi: 10.1159/000448916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya Y., Doyle M., Henretta J.C., Timonen V. Depressive symptoms among older adults: The impact of early and later life circumstances and marital status. Aging & Mental Health. 2013;17(3):349–357. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.747078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok R., Avendano M., Bago d'Uva T., Mackenbach J. Can reporting heterogeneity explain differences in depressive symptoms across Europe? Social Indicators Research. 2012;105(2):191–210. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9877-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey R.J., Belcher J., Croft P.R. Validity of two simple measures for estimating life-course socio-economic position in cross-sectional postal survey data in an older population: Results from the north staffordshire osteoarthritis project (NorStOP) BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2012;12(1):88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landös A., von Arx M., Cheval B., Sieber S., Kliegel M., Gabriel R.…Cullati S. Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and disability trajectories in older men and women: A european cohort study. The European Journal of Public Health. 2018:50–58. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Linden B.W., Cheval B., Sieber S., Guessous I., Kliegel M., Courvoisier D. Associations of childhood socioeconomic position with frailty trajectories at older age. Innovation in Aging. 2017;1(suppl_1):235–236. [Google Scholar]

- Lindwall M., Larsman P., Hagger M.S. The reciprocal relationship between physical activity and depression in older european adults: A prospective cross-lagged panel design using SHARE data. Health Psychology. 2011;30(4):453–462. doi: 10.1037/a0023268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin H., Sapir E.V. Perceived income adequacy among older adults in 12 countries: Findings from the survey of health, ageing, and retirement in Europe. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(3):397–406. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppa M., Sikorski C., Luck T., Ehreke L., Konnopka A., Wiese B.…Riedel-Heller S.G. Age- and gender-specific prevalence of depression in latest-life--systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136(3):212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh A. Policy Press; 1999. Home sweet home?: The impact of poor housing on health. [Google Scholar]

- Miller G.E., Chen E., Fok A.K., Walker H., Lim A., Nicholls E.F.…Kobor M.S. Low early-life social class leaves a biological residue manifested by decreased glucocorticoid and increased proinflammatory signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(34):14716–14721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902971106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J., Ross C.E. Education, personal control, lifestyle and health:A human capital hypothesis. Research on Aging. 1998;20(4):415–449. [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J., Rijsdijk F.V., Sullivan M., van Sonderen E., Kempen G.I.J.M. Temporal and reciprocal relationship between IADL/ADL disability and depressive symptoms in late life. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57(4):P338–P347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.4.p338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L.I., Schieman S., Fazio E.M., Meersman S.C. Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46(2):205–219. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M.J., Reischies F., Beekman A.T., Fuhrer R., Jonker C., Kivela S.L.…Copeland J.R. Development of the EURO-D scale--a European, Union initiative to compare symptoms of depression in 14 European centres. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;174(4):330–338. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar A.P., Thangadurai P., Senthilkumar P., Gayathri K., Prince M., Jacob K.S. Nature, prevalence and factors associated with depression among the elderly in a rural south Indian community. International Psychogeriatrics. 2009;21(2):372–378. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209008527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini Z.I., Fiori K.L., Feeney J., Tyrovolas S., Haro J.M., Koyanagi A. Social relationships, loneliness, and mental health among older men and women in Ireland: A prospective community-based study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;204:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzbach M., Luppa M., Forstmeier S., Konig H.H., Riedel-Heller S.G. Social relations and depression in late life-a systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014;29(1):1–21. doi: 10.1002/gps.3971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M. Gender differences in adjustment to bereavement: An empirical and theoretical review. Review of General Psychology. 2001;5(1):62–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wahrendorf M., Blane D. Does labour market disadvantage help to explain why childhood circumstances are related to quality of life at older ages? Results from SHARE. Aging & Mental Health. 2015;19(7):584–594. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.938604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahrendorf M., Blane D., Bartley M., Dragano N., Siegrist J. Working conditions in mid-life and mental health in older ages. Advances in Life Course Research. 2013;18(1):16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walen H.R., Lachman M.E. Social support and strain from partner, family, and friends: Costs and benefits for men and women in adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2000;17(1):5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Widmer E.D. Routledge; 2016. Family configurations: A structural approach to family diversity. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. Is old age depressing? Growth trajectories and cohort variations in late-life depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48(1):16–32. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.