The Central Asia outbreak (CAO) clade is a branch of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype that is associated with multidrug resistance, increased transmissibility, and epidemic spread in parts of the former Soviet Union. Furthermore, migration flows bring these strains far beyond their areas of origin.

KEYWORDS: Beijing genotype, IS6110, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, drug resistance

ABSTRACT

The Central Asia outbreak (CAO) clade is a branch of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype that is associated with multidrug resistance, increased transmissibility, and epidemic spread in parts of the former Soviet Union. Furthermore, migration flows bring these strains far beyond their areas of origin. We aimed to find a specific molecular marker of the Beijing CAO clade and develop a simple and affordable method for its detection. Based on the bioinformatics analysis of the large M. tuberculosis whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data set (n = 1,398), we identified an IS6110 insertion in the Rv1359-Rv1360 intergenic region as a specific molecular marker of the CAO clade. We further designed and optimized a multiplex PCR method to detect this insertion. The method was validated in silico with the recently published WGS data set from Central Asia (n = 277) and experimentally with M. tuberculosis isolates from European and Asian parts of Russia, the former Soviet Union, and East Asia (n = 319). The developed molecular assay may be recommended for rapid screening of retrospective collections and for prospective surveillance when comprehensive but expensive WGS is not available or practical. The assay may be especially useful in high multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) burden countries of the former Soviet Union and in countries with respective immigrant communities.

INTRODUCTION

The Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype remains the most studied lineage of this important human pathogen. In its turn, the Beijing genotype encompasses multiple and distant sublineages and clades, some of whom have attracted special attention due to the particularly hazardous combination of pathogenic strain properties and certain migration flows that can bring such strains far beyond their areas of origin. Countries of the former Soviet Union are marked with high levels of tuberculosis (TB) incidence and rate of drug resistance. The contributing M. tuberculosis genotypes are not uniformly spread across these countries. The most known clonal clusters belong to the Beijing genotype and are designated as the Russian epidemic sublineage B0/W148 and the Central Asian sublineage. While the former is well known and was extensively studied, the latter one received much less attention. It also exemplifies the confusing terminological issues of the M. tuberculosis nomenclature. This cluster has consecutively received different names in different studies as follows: CC1 or Central Asian (1), East Europe 1 (2), and Central Asian/Russian (3). It largely correlates with the multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (MLVA) 94-32 cluster (3) and IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) A0 cluster and Beijing 12 mycobacterial interspersed repetitive-unit (MIRU) M2 subtype (4, 5). It is the major Beijing sublineage in the former Soviet Central Asia and one of the two major clusters spread in different parts of Russia. In spite of development of the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) barcode nomenclature (6) that is digital and hence more precise, the use of geographically derived names remains helpful. Accordingly, due to the high prevalence not only in Central Asia but also in different regions across Russia, this Beijing sublineage would be more appropriately named “Central Asian/Russian.”

Importantly, this sublineage is heterogeneous, but its most dangerous component has been named in a very similar way as the Central Asia outbreak (CAO) clade (1). In other words, “Central Asian” and “Central Asia outbreak” are not synonymous names of the same genotype. Instead, CAO is a part of the Central Asian sublineage of the Beijing genotype and should be clearly distinguished from it.

Previous studies in Central Asia highlighted medically critical features of the Beijing CAO clade. First, in Uzbekistan, these closely genetically related strains were strongly associated with multidrug resistance (MDR) (1). Next, the prisons in the former Soviet Union have been marked with overcrowding, hence conditions facilitating transmission of the most transmissible strains. In this sense, it is noteworthy that Beijing CAO strains were highly prevalent in the prison setting in Kyrgyzstan (7). In contrast, strains of the Central Asian sublineage on the whole were shown to be more prevalent but less MDR-associated than Beijing B0/W148 strains in northwestern Russia (8) and West Siberia (9). It is possible that Russian strains of the Central Asian sublineage do not belong to CAO but to other clones. Only rare CAO strains have been identified in the Samara region in central Russia to date (10).

IS6110 is one of the major drivers of M. tuberculosis genome evolution, but some copies of this mobile element are sufficiently stable on an evolutionary time scale. Accordingly, they may serve as specific markers of phylogenetic entities provided that such specificity was proven on a large body of available genomes and collections. For example, PCR methods based on detection of specific IS6110 have been developed for the Latin American Mediterranean (LAM) family (11), Beijing genotype on the whole (12), and the Beijing B0/W148 strain (13).

To sum up, the Beijing CAO clade presents an epidemic, highly transmissible, and MDR-associated cluster of M. tuberculosis isolates. The economic migration flows emanating from Central Asia may ultimately result in a wider dissemination of these strains on a global scale. This emphasizes the urgent need for development of a simple and affordable method of their detection. Here, we aimed to find an IS6110 insertion specific to the medically significant M. tuberculosis CAO clade and to develop a method for its detection. The assay was validated both in silico and through experimental analysis of M. tuberculosis strains of different origins and genotypes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

M. tuberculosis isolates.

For the specific purposes of this study, M. tuberculosis isolates were selected on the basis of their different origins and diverse genetic background and do not correlate with local population structures. M. tuberculosis DNA samples were obtained during our ongoing or completed studies and represented the northern part of European Russia (Komi Republic) and southwestern Siberia (Omsk region). Two other collections were previously described convenience samples from Vietnam and Belarus (12).

M. tuberculosis drug susceptibility testing of the Russian isolates for 1st and 2nd line drugs (streptomycin, isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, ofloxacin, kanamycin, capreomycin, cycloserine, para-aminosalicylic acid) was carried out for all strains using the method of absolute concentrations on solid Lowenstein-Jensen medium according to order number 109 of the Ministry of Healthcare of the Russian Federation and using the Bactec MGIT 960 system (Becton, Dickinson, Sparks, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The laboratories in Syktyvkar (Komi) and Omsk are externally quality assured by the System for External Quality Assessment Center for External Quality Control of Clinical Laboratory Research (Moscow, Russia).

Genotyping.

A cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)-based procedure was used for DNA extraction. The Beijing genotype, Beijing B0/W148 cluster, and Beijing 94-32 cluster were detected by PCR assays as previously described (5, 12, 13). Spoligotyping and 24 MIRU–variable-number tandem-repeat (VNTR) typing were performed as described in references 14 and 15, respectively.

In silico analysis and determination of the CAO-specific IS6110 insertion.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data of 1,398 M. tuberculosis isolates of lineage 2 (East Asian lineage, a major part of which is the Beijing genotype) were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA). The data set consisted of 13 independent WGS studies and was described in more detail in our previous study (16). In summary, 186 samples belonged to the ancient Beijing sublineages (20 proto-Beijing, 50 Asia Ancestral 1, 20 Asia Ancestral 2, 62 Asia Ancestral 3), while 1,212 isolates belonged to the modern Beijing sublineages (18 Asian African 1, 101 Asian African 2, 38 Asian African 3, 61 Pacific RD150, 3 Asian African 2/RD142, 289 Europe/Russia W148, 361 Central Asian). Differentiation of clade A and CAO branches within the Central Asian sublineage was carried out using previously described SNPs (1, 16).

The identification of IS6110 integration sites was carried out using ISMapper pipeline (17). The pipeline employs a split-read approach and consists of two scripts. The first script makes a table of insertions for each isolate. The second one creates one large table showing all possible insertion element (IS) query locations in all isolates as well as in the reference genome.

Information on gene properties was taken from TubercuList (https://mycobrowser.epfl.ch).

PCR assay for detection of the CAO clade.

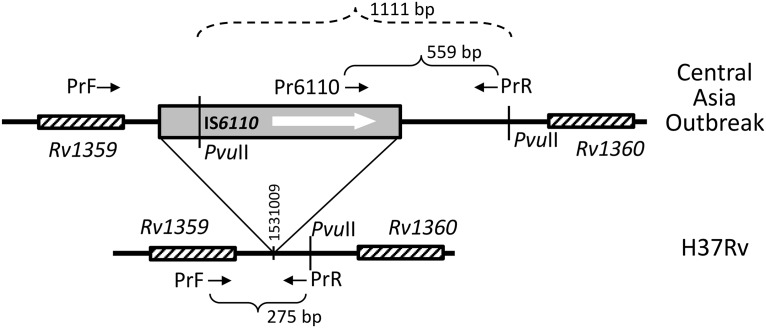

Initial assessment and optimization of the PCR assay were done with 10 DNA samples of phylogenetically confirmed CAO and non-CAO isolates (i.e., those with available next-generation sequencing [NGS] data obtained in our laboratories and included in the above phylogenetic analysis). The portion of the Rv1359-Rv1360 intergenic region was amplified with primers Pr6110 (5′-CGTACTCGACCTGAAAGACG), PrF (5′-GGATGGTCCTTGCTGGGTG), and PrR (5′-GTATGAGCACAAGACACCGC) in 25 μl of PCR mixture (15 pmol of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 U Taq DNA polymerase, 200 μM [each] deoxynucleoside triphosphates [dNTPs]) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 63°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 50 s; and final elongation at 72°C for 50 s. The PCR products were separated in the 1.3% standard agarose gel and photographed in UV light. The specifically amplified fragments were 559 bp (amplified with Pr6110-PrR primers) for the CAO strain and 275 bp (amplified with PrF-PrR primers) for any other strain.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

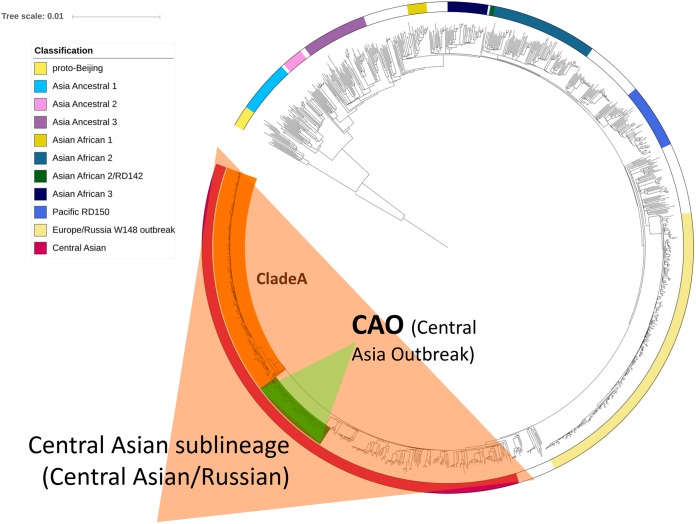

On the global WGS-based dendrogram of lineage 2, several monophyletic branches can be seen, including the homogeneous B0/W148 cluster and more diverse Central Asian/Russian branch (Fig. 1). In its turn, the latter contains a monophyletic group of closely related isolates of the CAO clade (n = 81). Superposition of the in silico identified IS6110 insertions on the dendrogram revealed a specific integration site that was found exclusively in all CAO strains. This IS6110 was located in the intergenic region between Rv1359 and Rv1360 at position 1531009 in the H37Rv genome (Fig. 2).

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic tree of M. tuberculosis lineage 2 isolates. Central Asian sublineage and Central Asia outbreak (CAO) clade are highlighted.

FIG 2.

Schematic view of the genome region containing the IS6110 insertion specific to the Beijing CAO clade (not to scale). Short arrows indicate the primers. PvuII site-flanked fragment (CAO-specific band in IS6110-RFLP fingerprint) is shown by dashed lines.

The first of these two genes, Rv1359, encodes a probable transcriptional regulatory protein, which is involved in the transcriptional mechanism. The second gene, Rv1360, encodes a probable oxidoreductase that is probably involved in cellular metabolism while it is assigned to functional category “intermediary metabolism and respiration.” Transcriptomics study demonstrated its mRNA to be downregulated after 24 h of starvation. Both Rv1359 and Rv1360 were nonessential genes for in vitro growth of H37Rv (TubercuList, https://mycobrowser.epfl.ch).

The CAO-specific integration site is located 338 bp upstream of Rv1360 and is in the same orientation. An overexpression of Rv1360 was determined in amikacin- and kanamycin-resistant M. tuberculosis isolates, speculatively suggesting its role in the compensation of drug resistance (18). Finally, it may be noted that a PPE family gene (PPE19, a core mycobacterial gene, conserved in mycobacterial strains) is located immediately downstream of Rv1360. However, a causative correlation between this specific IS6110 insertion and epidemic capacities of the CAO strain should be studied in experimental models.

The specificity of the identified IS6110 insertion was additionally assessed in silico with a recently published WGS data set from Uzbekistan (19). The collection included 277 strains; of them, 237 belonged to the Beijing genotype. The phylogenetic analysis and identification of IS6110 insertion sites confirmed that only isolates of the CAO clade (n = 173) had this IS6110 insertion.

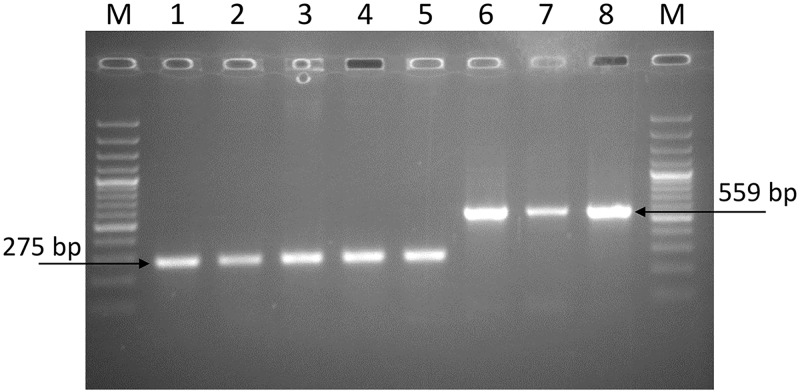

The performance of the developed assay was experimentally validated with DNA samples from different settings and genetic families of M. tuberculosis. The collections represented both European and Asian parts of Russia, former Soviet Union (Belarus), and East Asia (Vietnam), i.e., settings with a high prevalence of the Beijing genotype. Collections included isolates of lineages 1, 2, and 4 (Table 1). The Beijing genotype isolates represented both ancient and modern sublineages, and the latter included two major Beijing genotype clusters prevalent in the former Soviet Union, i.e., B0/W148 (Russian epidemic cluster) and 94-32 (Central Asian/Russian sublineage). In total, 319 isolates were tested, and unambiguous results were obtained for all samples, i.e., amplification of either one or another fragment (Fig. 3). The CAO-specific band was amplified only in a fraction of strains of the Beijing 94-32 cluster. Although a phylogeographic assessment was beyond the scope of this study, we note that only one CAO isolate was found in the northern Russian region of Komi compared to 5 CAO isolates in the Omsk region in Siberia (Table 1). Given the common border of the Omsk region with Kazakhstan, this gradient correlates with a known high prevalence of the CAO clade in Central Asia.

TABLE 1.

M. tuberculosis strain collections used for experimental validation of the Central Asia outbreak clade PCR assay

| Country, region, genotypea | No. Russia, Northwest, Komi (n = 88) | No. Russia, Siberia, Omsk (n = 131) | No. Belarus (n = 44) | No. Vietnam (n = 57) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing, all | 46 | 93 | 32 | 30 |

| Central Asian/Russian sublineage, CAO clade | 1 | 5 | ||

| Central Asian/Russian sublineage, non-CAO isolates | 28 | 46 | 16 | |

| B0/W148 (100-32) cluster | 14 | 42 | 9 | |

| Beijing, other | 3 | 38 | 7 | 30 |

| Non-Beijing, all | 42 | 12 | 27 | |

| LAM | 12 | 12 | 1 | |

| Ural | 9 | |||

| Haarlem | 4 | 1 | ||

| T (SIT53) | 8 | 2 | ||

| T (other) | 5 | |||

| L4 (unknown family) | 4 | |||

| EAI | 23 |

Beijing Central Asian/Russian sublineage was detected based on IS6110-RFLP typing (as A0 profile [4]), 24-loci MIRU-VNTR typing (Beijing 94-32 cluster), or through detection of the specific SNP in the sigE gene (3). Beijing B0/W148 cluster (successful Russian Beijing strain) was detected by IS6110-RFLP typing (as B0 profile [4]), 24-loci MIRU-VNTR typing (Beijing 100-32 cluster), or by testing specific IS6110 insertion (13). Non-Beijing families were defined by spoligotyping followed by expert-based correction and/or testing specific SNPs (LAM and Ural).

FIG 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of the Rv1359-Rv1360 PCR products of M. tuberculosis isolates. (Lanes 1 to 5) M. tuberculosis isolates with intact Rv1359-Rv1360 intergenic region; (lanes 6 to 8) isolates of the Beijing CAO clade; M, Thermo Scientific GeneRuler 100-bp Plus DNA Ladder. Arrows show specific bands for Beijing CAO (559 bp) and other genotypes (275 bp).

The information on drug resistance profiles of the identified CAO isolates and other Russian isolates is summarized in Table S1 in the supplemental material. A single CAO isolate from Komi was polyresistant. In Omsk, 2 CAO isolates were polyresistant, and 3 were MDR. This differs from a situation with non-CAO strains of the Central Asian sublineage in Omsk (n = 46) in which 30 were susceptible, 5 monoresistant, 3 polyresistant, and 8 MDR. The previous study in Omsk demonstrated significantly decreased odds of being MDR for the Beijing 94-32 cluster (i.e., Central Asian sublineage) compared to those for the Beijing B0/W148 cluster (9).

Since using a DNA extracted from bacterial culture delays the strain genotype identification of a strain, several commercially available nucleic acid amplification tests for use directly on sputum have been published and are in use (20–22). Accordingly, we have recently started a long-term prospective study involving several sites in Russia and Kazakhstan to validate the developed molecular test with DNA extracted from clinical material. The preliminary results obtained with microscopy-positive sputum samples appear to be quite promising under optimized PCR conditions, including increased number of PCR cycles (not shown).

In conclusion, assays targeting particular epidemic strains (e.g., successful Russian clone Beijing B0/W148) were proven useful in clinical practice in Russia (13, 20). In this way, a clinical doctor is rapidly informed about an especially dangerous infecting strain. In its turn, an epidemiologist would be no less timely informed about the penetration of such a strain into a new region. The CAO branch is an important epidemic group, but it is indistinguishable from the larger and heterogeneous Central Asian sublineage of the Beijing genotype by 24 MIRU-VNTR typing.

The herein described molecular assay may be recommended for rapid screening of retrospective collections and for prospective monitoring of circulating M. tuberculosis strains, when comprehensive but expensive WGS is not available or practical. The Beijing CAO clade is a cluster of closely related but already diverged strains, and they have different resistance profiles. The developed method is by no means intended to replace drug susceptibility testing but will provide epidemiologists and/or clinical doctors with important information about the infecting strain. The assay may become a useful complement of the methodological repertoire in high MDR-TB burden countries of the former Soviet Union and in the countries with respective immigrant communities.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR) 18-04-01035.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00215-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Merker M, Blin C, Mona S, Duforet-Frebourg N, Lecher S, Willery E, Blum MG, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Mokrousov I, Aleksic E, Allix-Béguec C, Antierens A, Augustynowicz-Kopeć E, Ballif M, Barletta F, Beck HP, Barry CE III, Bonnet M, Borroni E, Campos-Herrero I, Cirillo D, Cox H, Crowe S, Crudu V, Diel R, Drobniewski F, Fauville-Dufaux M, Gagneux S, Ghebremichael S, Hanekom M, Hoffner S, Jiao WW, Kalon S, Kohl TA, Kontsevaya I, Lillebæk T, Maeda S, Nikolayevskyy V, Rasmussen M, Rastogi N, Samper S, Sanchez-Padilla E, Savic B, Shamputa IC, Shen A, Sng LH, Stakenas P, Toit K, Varaine F, Vukovic D, Wahl C, Warren R, Supply P, Niemann S, Wirth T. 2015. Evolutionary history and global spread of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing lineage. Nat Genet 47:242–249. doi: 10.1038/ng.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo T, Comas I, Luo D, Lu B, Wu J, Wei L, Yang C, Liu Q, Gan M, Sun G, Shen X, Liu F, Gagneux S, Mei J, Lan R, Wan K, Gao Q. 2015. Southern East Asian origin and coexpansion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing family with Han Chinese. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:8136–8141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424063112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mokrousov I, Chernyaeva E, Vyazovaya A, Skiba Y, Solovieva N, Valcheva V, Levina K, Malakhova N, Jiao WW, Gomes LL, Suffys PN, Kutt M, Aitkhozhina N, Shen AD, Narvskaya O, Zhuravlev V. 2018. Rapid assay for detection of the epidemiologically important Central Asian/Russian strain of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype. J Clin Microbiol 56:e01551-17. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01551-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narvskaya O, Mokrousov I, Otten T, Vishnevsky B. 2005. Molecular markers: application for studies of Mycobacterium tuberculosis population in Russia, p 111–125. In Read MM. (ed), Trends in DNA fingerprinting research. Nova Science Publishers, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mokrousov I, Narvskaya O, Vyazovaya A, Millet J, Otten T, Vishnevsky B, Rastogi N. 2008. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype in Russia: in search of informative variable-number tandem-repeat loci. J Clin Microbiol 46:3576–3584. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00414-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coll F, McNerney R, Guerra-Assunção JA, Glynn JR, Perdigão J, Viveiros M, Portugal I, Pain A, Martin N, Clark TG. 2014. A robust SNP barcode for typing Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. Nat Commun 5:4812. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mokrousov I, Valcheva V, Sovhozova N, Aldashev A, Rastogi N, Isakova J. 2009. Penitentiary population of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Kyrgyzstan: exceptionally high prevalence of the Beijing genotype and its Russia-specific subtype. Infect Genet Evol 9:1400–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vyazovaya A, Solovieva N, Gerasimova A, Akhmedova G, Turkin E, Sunchalina T, Tarashkevich R, Bogatin S, Gavrilova N, Bychkova A, Anikieva E, Zhuravlev V, Narvskaya O, Mokrousov I. 2019. Population structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Russian regions bordering EU countries. Russ J Infect Immun 8:585. doi: 10.15789/2220-7619-2018-4-6.59. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasechnik O, Vyazovaya A, Vitriv S, Tatarintseva M, Blokh A, Stasenko V, Mokrousov I. 2018. Major genotype families and epidemic clones of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Omsk region, Western Siberia, Russia, marked by a high burden of tuberculosis-HIV coinfection. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 108:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casali N, Nikolayevskyy V, Balabanova Y, Harris SR, Ignatyeva O, Kontsevaya I, Corander J, Bryant J, Parkhill J, Nejentsev S, Horstmann RD, Brown T, Drobniewski F. 2014. Evolution and transmission of drug-resistant tuberculosis in a Russian population. Nat Genet 46:279–286. doi: 10.1038/ng.2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marais BJ, Victor TC, Hesseling AC, Barnard M, Jordaan A, Brittle W, Reuter H, Beyers N, van Helden PD, Warren RM, Schaaf HS. 2006. Beijing and Haarlem genotypes are overrepresented among children with drug-resistant tuberculosis in the Western Cape province of South Africa. J Clin Microbiol 44:3539–3543. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01291-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mokrousov I, Vyazovaya A, Zhuravlev V, Otten T, Millet J, Jiao WW, Shen AD, Rastogi N, Vishnevsky B, Narvskaya O. 2014. Real-time PCR assay for rapid detection of epidemiologically and clinically significant Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype isolates. J Clin Microbiol 52:1691–1693. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03193-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mokrousov I, Narvskaya O, Vyazovaya A, Otten T, Jiao WW, Gomes LL, Suffys PN, Shen AD, Vishnevsky B. 2012. Russian “successful” clone B0/W148 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype: a multiplex PCR assay for rapid detection and global screening. J Clin Microbiol 50:3757–3759. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02001-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamerbeek J, Schouls L, Kolk A, van Agterveld M, van Soolingen D, Kuijper S, Bunschoten A, Molhuizen H, Shaw R, Goyal M, van Embden J. 1997. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol 35:907–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Supply P, Allix C, Lesjean S, Cardoso-Oelemann M, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Willery E, Savine E, de Haas P, van Deutekom H, Roring S, Bifani P, Kurepina N, Kreiswirth B, Sola C, Rastogi N, Vatin V, Gutierrez MC, Fauville M, Niemann S, Skuce R, Kremer K, Locht C, van Soolingen D. 2006. Proposal for standardization of optimized mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit-variable-number tandem repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 44:4498–4510. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01392-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shitikov E, Kolchenko S, Mokrousov I, Bespyatykh J, Ischenko D, Ilina E, Govorun V. 2017. Evolutionary pathway analysis and unified classification of East Asian lineage of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci Rep 7:9227. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10018-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawkey J, Hamidian M, Wick RR, Edwards DJ, Billman-Jacobe H, Hall RM, Holt KE. 2015. ISMapper: identifying transposase insertion sites in bacterial genomes from short read sequence data. BMC Genomics 16:667. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1860-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma D, Lata M, Singh R, Deo N, Venkatesan K, Bisht D. 2016. Cytosolic proteome profiling of aminoglycosides resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates using MALDI-TOF/MS. Front Microbiol 7:1816. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merker M, Barbier M, Cox H, Rasigade JP, Feuerriegel S, Kohl TA, Diel R, Borrell S, Gagneux S, Nikolayevskyy V, Andres S, Nubel U, Supply P, Wirth T, Niemann S. 2018. Compensatory evolution drives multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Central Asia. Elife 7:38200. doi: 10.7554/eLife.38200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimenkov DV, Kulagina EV, Antonova OV, Zhuravlev VY, Gryadunov DA. 2016. Simultaneous drug resistance detection and genotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis using a low-density hydrogel microarray. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:1520–1531. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma K, Sharma M, Chaudhary L, Modi M, Goyal M, Sharma N, Sharma A, Jain A, Dhibar DP, Jain K, Khandelwal N, Ray P, Lal V, Salfinger M. 2018. Comparative evaluation of Xpert MTB/RIF assay with multiplex polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 113:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rockwood N, Wojno J, Ghebrekristos Y, Nicol MP, Meintjes G, Wilkinson RJ. 2017. Utility of second-generation line probe assay (Hain MTBDRplus) directly on 2-month sputum specimens for monitoring tuberculosis treatment response. J Clin Microbiol 55:1508–1515. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00025-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.