To the Editor: Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) is a histologic subtype that accounts for approximately 38% of uterine sarcomas.[1] Early and complete surgical resection of ESS is the initial treatment.[2] However, the effect of local treatment modalities for ovarian conservation, lymphadenectomy, and postoperative radiation remains unclear. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2009 system classifies ESS patients with lymph node metastasis as stage IIIC, implying a significant adverse effect of lymph node status on patient prognosis. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network,[3] bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is preferred in low-grade ESS (LGESS), but no evidence supports the choice of lymphadenectomy, and the management of ovaries may be individualized in patients of reproductive age. Over 80% of patients with LGESS are estrogen receptor-positive,[4] and postoperative estrogen blockade is recommended for stages II to IV LGESS.[5,6] Adjuvant radiotherapy is recommended as a postoperative treatment for patients with stage II disease to reduce local recurrence rates. However, the benefits of lymph node resection after primary surgery (total hysterectomy/bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) in nonmetastatic LGESS remain controversial.[7] Moreover, few studies found that oophorectomy and hormone receptor status had no influence on overall survival (OS) and endocrine therapy.[8] Few studies have also suggested that postoperative pelvic radiotherapy did not improve OS in stage I or stage II uterine sarcomas.[9] Because these studies are biased by heterogeneity and small sample sizes,[3] we retrospectively reviewed treatments of patients with LGESS in the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) 18 registry database (1973–2015, submission in November 2017) to evaluate the impact of lymphadenectomy, postoperative radiation, and ovarian conservation on survival outcome (5-year OS and 5-year cause-specific survival [CSS]) in LGESS patients.[10]

LGESS was based on the International Classification of Disease for Oncology, Third Edition. Data involved in this study represent the most recent follow-up (December 31, 2015) available in the SEER database. Patients were screened for the following eligibility criteria: diagnosis of LGESS, primary disease of uterus, active follow-up, and treatment with surgery. Detailed demographic, oncological, and survival data were collected. Cancer stage was reclassified according to FIGO staging 2009 based on tumor size, tumor extension, and lymph node status recorded in the database. Those without a code for oophorectomy or specific ovarian conservation were considered as having unknown oophorectomy status and therefore excluded from the study. Propensity score matching for each group was calculated for each case through an automated algorithm with the propensity score difference cutoff being 1%. Patient demographics, tumor characteristics, and treatment patterns were included in the propensity score model (PSM) [Table 1].

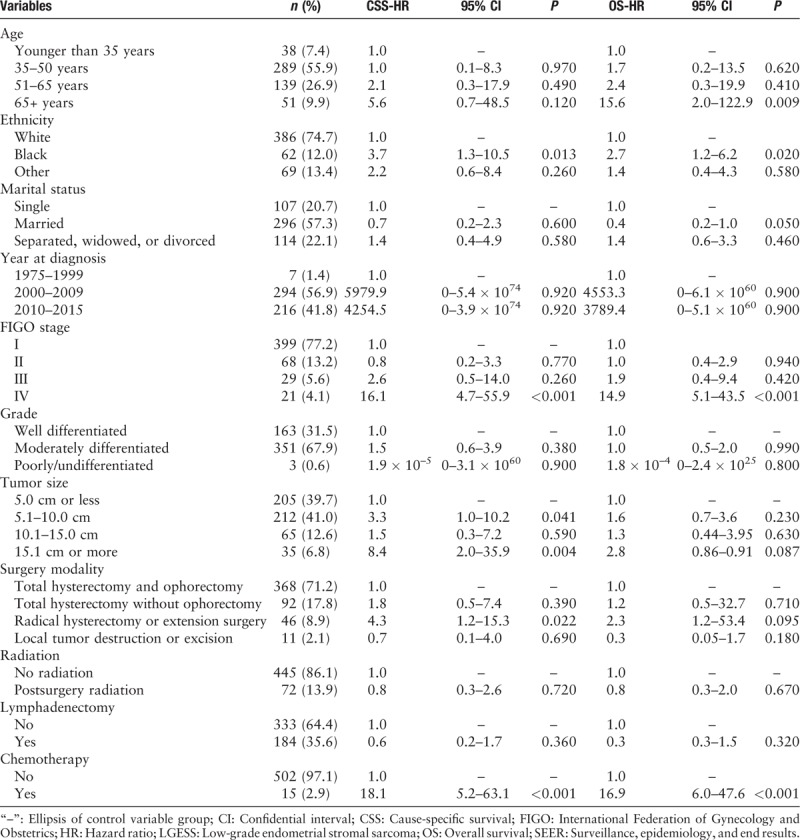

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic and treatment characteristics of the patients with LGESS in SEER database from 1973 to 2015 (n = 517).

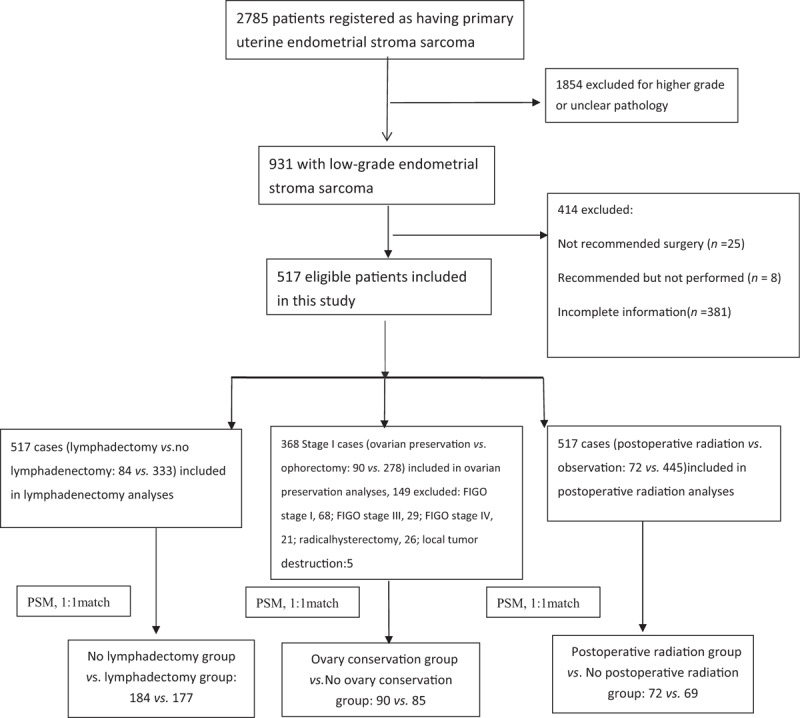

A total of 517 patients with low-grade uterine sarcoma were included for the analysis of lymphadenectomy and postoperative radiation, and 368 patients were available for the analysis of ovarian conservation in stage I [Figure 1]. The data used in this study were from the public database, which did not involve privacy protection and ethic approval. Mean age at the time of diagnosis was 49.2 ± 11.2 years (range, 16–85 years), and 63.2% (327/517) of patients were younger than 50 years. The mean follow-up duration was 67.9 ± 56.3 months (95% confidential interval, 63.1–72.8 months). Most of the patients were white women (74.7%, 386/517), followed by black women (12.0%, 62/517) and those of other ethnicities (13.4%, 69/517). There were 399 (77.2%) patients, 68 (13.2%), 29 (5.6%), and 21 (4.1%) with stages I, II, III, and IV, respectively. Among them, 67.9% (351/517) had moderately differentiated carcinoma, and 31.5% (163/517) had well-differentiated carcinoma. Moreover, 17.8% (92/517) of patients underwent ovarian conservation, 35.6% (184/517) underwent lymphadenectomy, and 13.9% (72/517) underwent postoperative radiotherapy. The Cox regression analysis found that patients aged over 65 years were more likely to have advanced stage (stage IV). Patients with black ethnicity, those who underwent radical hysterectomy or extension surgery, and those who received chemotherapy had higher hazard ratio for death (P < 0.05 in OS or CSS) [Table 1]. After PSM with this information (including the aforementioned age, stage, ethnicity, chemotherapy, and surgery), there were no statistically significant differences between the internal baseline characteristics of the three groups.

Figure 1.

Flowchart exhibiting the selection of the study population of low-grade uterine sarcoma after excluding the patients not received the surgery and without complete information (n = 517). PSM: Propensity score model.

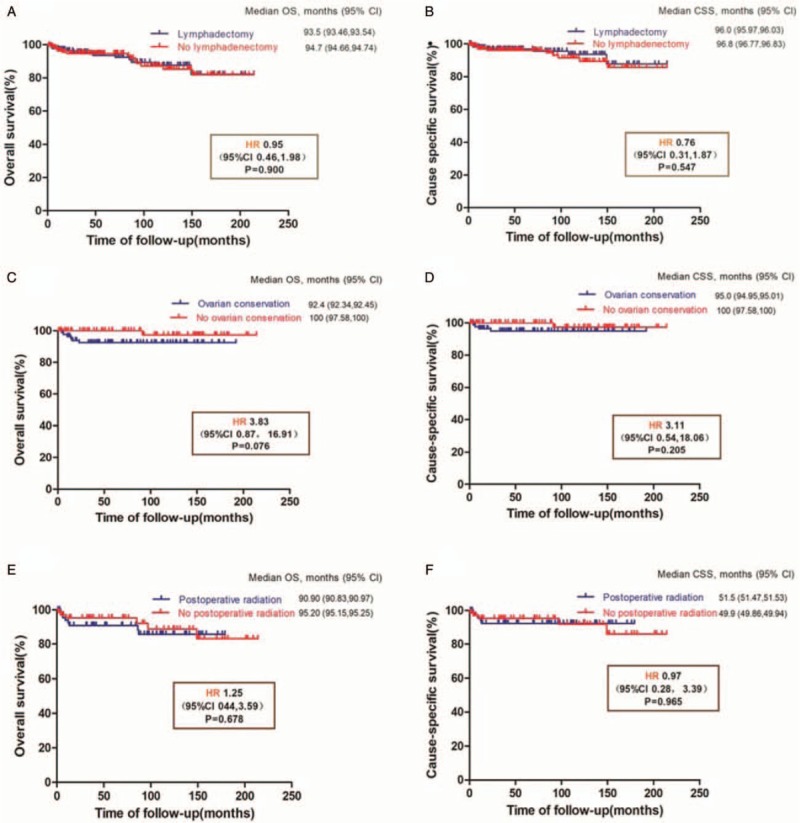

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to construct survival and cumulative risk curves, and statistically significant differences between the curves were compared with log-rank tests. In the lymphadenectomy group, the 5-year OS was 94.7% vs. 93.5% (log-rank test, P = 0.900), and the 5-year CSS was 96.0% and 96.8% (log-rank test, P = 0.550). In the ovarian conservation group, the 5-year OS was 92.4% vs. 100% (log-rank test, P = 0.076), and the 5-year CSS was 95.0% vs. 100% (log-rank test, P = 0.210). In the postoperative radiation group, the 5-year OS was 90.9% vs. 95.2% (log-rank test, P = 0.680), and the 5-year CSS was 92.3% vs. 95.2% (log-rank test, P = 0.970) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Survival outcomes of different treatment modalities in patients with low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. Overall survival (A) and CSS (B) of lymphadenectomy group (n = 361); overall survival (C) and CSS (D) of ovarian preservation group (n = 175); and overall survival (E) and CSS (F) of postoperative radiation group (n = 141). CI: Confidential interval; CSS: Cause-specific survival; HR: Hazard ratio; OS: Overall survival.

After controlling the variables of age, tumor stage, and other treatment information, we found that lymphadenectomy did not improve the 5-year OS and CSS in patients with LGESS. However, the necessity of lymphadenectomy may be emphasized, as lymphadenectomy contributes to FIGO staging and therefore influences future decisions regarding adjuvant therapy. Thus, determination of lymph node resection should be individualized. The ovary is an important organ in the production of estrogen hormones, and ovarian conservation decreases the risk of the development of osteoporosis and cardiovascular diseases in young women with other cancers.[11] In our study, 63.2% (327/517) of patients were aged <50 years, and the function of ovary met the physiological process. We found that ovarian conservation had no influence on both OS and CSS (P > 0.05) in patients with stage I LGESS.

Adjuvant radiotherapy in ESS reduces the local recurrence rate but has limited effect on survival.[12] In the previous studies,[3] patients treated with adjuvant radiotherapy presumably had higher risk factors (eg, larger tumors and deeper myometrial invasion). We found that postoperative radiation was not associated with higher OS and CSS in patients with LGESS after PSM by multivariable logistic regression analysis. Therefore, more studies are needed to assess patients with high-risk lesions for local recurrence, which can help provide guidance on subsequent therapy.

Our study did not provide information on tumor recurrence or exact details, which could help investigating differences in the progression-free survival. Data in our study may have some stage migration as not all patients underwent lymphadenectomy. Data from large-scale trials and multiple centers are needed because of the rarity of LGESS.

Therefore, total hysterectomy still remains the main treatment modality for early-stage LGESS. After surgery-based treatment, the long-term OS remains high (90% or more). Further, current evidence does not support lymphadenectomy and postoperative radiotherapy in patients with LGESS. The ovaries could be preserved in selected patients with stage I LGESS who prefer to retain hormonal function.

Acknowledgements

Thanks for the support of the SEER∗Stat Team.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Wang M, Meng SH, Li B, He Y, Wu YM. Survival outcomes of different treatment modalities in patients with low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. Chin Med J 2019;00:00–00. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000259

Ming Wang is now working in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Beijing Youan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100069, China.

References

- 1.Yang H, Li XC, Yao C, Lang JH, Jin HM, Xi MR, et al. Proportion of uterine malignant tumors in patients with laparoscopic myomectomy: a National Multicenter Study in China. Chin Med J 2017; 130:2661–2665. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.218008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amant F, Floquet A, Friedlander M, Kristensen G, Mahner S, Nam EJ, et al. Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) consensus review for endometrial stromal sarcoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2014; 24:67–72. doi: 10.1097/IGC. 0000000000000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Uterine Neoplasms. v.1; 2018. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/ [Accessed November 8, 2018] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bai H, Yang J, Cao D, Huang H, Xiang Y, Wu M, et al. Ovary and uterus-sparing procedures for low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: a retrospective study of 153 cases. Gynecol Oncol 2014; 132:654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichardt P. The treatment of uterine sarcomas. Ann Oncol 2012; 23 suppl 10:x151–x157. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thanopoulou E, Judson I. Hormonal therapy in gynecological sarcomas. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2012; 12:885–894. doi: 10.1586/era.12.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dos Santos LA, Garg K, Diaz JP, Soslow RA, Hensley ML, Alektiar KM, et al. Incidence of lymph node and adnexal metastasis in endometrial stromal sarcoma. Gynecol Oncol 2011; 121:319–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.12.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou J, Zheng H, Wu SG, He ZY, Li FY, Su GQ, et al. Influence of different treatment modalities on survival of patients with low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg 2015; 23:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed NS, Mangioni C, Malmström H, Scarfone G, Poveda A, Pecorelli S, et al. Phase III randomised study to evaluate the role of adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy in the treatment of uterine sarcomas stages I and II: an European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gynaecological Cancer Group Study (protocol 55874). Eur J Cancer 2008; 44:808–818. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer statistics. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/ [Accessed November 16, 2017] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuo K, Machida H, Shoupe D, Melamed A, Muderspach LI, Roman LD, et al. Ovarian conservation and overall survival in young women with early-stage cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2017; 129:139–151. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schick U, Bolukbasi Y, Thariat J, Abdahbortnyak R, Kuten A, Igdem S, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors in endometrial stromal tumors: a Rare Cancer Network study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012; 82:e757–e763. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]