Much of the nervous system is considered to have limited regenerative capacity. Peripheral nerves, however, are one notable exception. When nerve trunks in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) are injured, the damaged axons can regrow at a rate of 1–3 mm per day (in rodents) and reinnervate their original targets (Scheib and Höke, 2013). Much of this high regenerative potential is attributed to the unique properties of PNS glial cells, the Schwann cells (Brosius Lutz and Barres, 2014; Jessen and Mirsky, 2016). The primary function of Schwann cells is production of myelin around peripheral axons. However, after an insult, these cells rapidly lose their differentiated state and become the center of a complex injury response: (1) they break down their own myelin through autophagy and phagocytosis (Gomez-Sanchez et al., 2015; Jang et al., 2016; Brosius Lutz et al., 2017); (2) they recruit inflammatory cells to assist in myelin clearance (Martini et al., 2008); (3) they secrete neurotrophic factors to support neuron survival and axon regrowth (Meyer et al., 1992; Webber and Zochodne, 2010; Fontana et al., 2012); and (4) they remyelinate the regenerated axons (Gomez-Sanchez et al., 2017). This well-orchestrated set of events is key to successful nerve repair.

Establishing and maintaining the myelinated fate and, conversely, switching to the repair-cell phenotype involve drastic changes in the transcriptional landscape of Schwann cells. The zinc-finger transcription factor Krox20 is considered to be the master regulator of myelinating Schwann cells (Topilko et al., 1994; Decker et al., 2006). In contrast, c-Jun has been identified as the single most important transcription factor for determining the repair-cell identity (Jessen and Mirsky, 2016). When c-Jun upregulation after injury is genetically abolished, both the conversion of myelinating Schwann cells to repair cells and nerve regeneration falter (Arthur-Farraj et al., 2012). Upregulation of c-Jun can also be observed independent of physical nerve injury, such as in hereditary demyelinating neuropathies, where it appears to prevent excessive secondary loss of sensory axons (Hantke et al., 2014). In light of these findings, elevation of c-Jun has been suggested as a potential strategy to rescue nerve regeneration when it fails, or to reduce axon loss in neuropathies. But would supraphysiological levels of c-Jun be compatible with myelination?

In a study recently published in The Journal of Neuroscience, Fazal et al. (2017) answered this important question. They used a genetic system in which an extra copy of c-Jun is expressed under the control of a myelin-specific protein (P0) in mice. This system ensures expression of c-Jun specifically in Schwann cells starting from late embryonic development, and it allows moderate or strong elevation of c-Jun to different degrees, depending on whether mice are heterozygous or homozygous for the transgenic allele.

Moderate overexpression of c-Jun in heterozygous mice caused only a slight thinning of the myelin sheaths in adult mice, probably due to a correspondingly slight delay in the onset of myelination. In contrast, higher expression of c-Jun in homozygous mutants strongly interfered with nerve development: Schwann cells failed to myelinate a significant proportion of axons, myelinated axons had very thin myelin, and signs of demyelination developed in older animals.

These morphological findings were matched by corresponding changes in the nerve transcriptome. While comparatively few transcripts were altered in heterozygous mutant mice, many more genes were either upregulated or downregulated in homozygous mutants. Interestingly, among the upregulated genes were some previously shown to be specific for repair Schwann cells and not expressed during development, such as Shh, Olig1, and Gdnf (Arthur-Farraj et al., 2012). Thus, overexpression of c-Jun alone might be sufficient to reprogram Schwann cells of intact nerves into repair-like cells. This interpretation is consistent with previous transcriptome-wide analyses showing that these “repair genes” fail to be upregulated in the absence of c-Jun (Arthur-Farraj et al., 2012).

Somewhat surprisingly, Krox20 levels were not greatly perturbed when c-Jun was elevated. Previous cell-culture investigations had uncovered a cross-inhibitory relationship between Krox20 and c-Jun. High c-Jun levels impeded Krox20 upregulation during Schwann cell differentiation (Parkinson et al., 2008), and in turn high Krox20 levels reduced phosphorylation of c-Jun by Jun-N-terminal kinase (Parkinson et al., 2004). However, in the present study, moderate overexpression of c-Jun in heterozygous mice did not detectably affect Krox20 expression, at either the mRNA or the protein level. Higher overexpression of c-Jun in homozygous mice did result in lower Krox20 levels in adult animals, but no significant changes were found at an earlier time point. Thus, the interaction between these two master transcription factors may be more complex than previously hinted at in the in vitro experiments.

Fazal et al. (2017) also assessed the impact of c-Jun overexpression on nerve regeneration in heterozygous animals. Considering the importance of c-Jun in nerve regeneration, one would expect overexpression of c-Jun to potentiate this process. Myelin clearance was indeed accelerated in mutant animals, as indicated by a lower number of intact myelin sheaths and lower levels of the myelin protein MBP in mutants than in injured control nerves. Less clear, however, is whether other aspects of the Schwann cell response to injury, such as promotion of neuron survival and axon regrowth, were also enhanced by the supraphysiological levels of c-Jun. Indeed, functional tests revealed that both sensory and motor recovery was even delayed in mutant animals, although full functional recovery was eventually achieved. Additionally, while myelination defects during development were observed mainly in homozygous mutants expressing high c-Jun, moderate overexpression of c-Jun in heterozygous mutant mice was sufficient to substantially delay the onset of remyelination after injury.

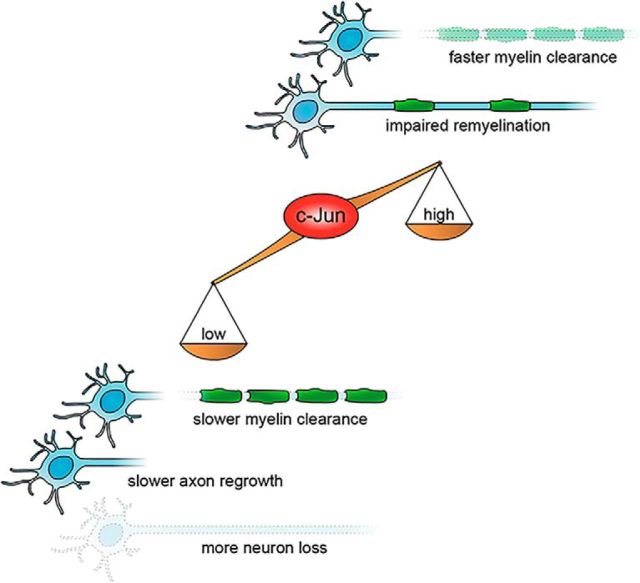

Overall, the study by Fazal et al. (2017) adds an important missing piece to our understanding of c-Jun function(s) in Schwann cells. Previous cell-culture studies had implicated c-Jun in the negative regulation of developmental myelination (Parkinson et al., 2008), consistent with the observation that its levels plummet as Schwann cells start myelinating. However, deletion of Schwann cell c-Jun in vivo was without detectable consequences (Parkinson et al., 2008; Fontana et al., 2012). With all due caution when translating overexpression experiments to normal physiology, the results of the present study suggest that c-Jun does act as a negative regulator of myelination during nerve development. Additionally, they indicate that manipulation of c-Jun levels in pathophysiological conditions for therapeutic purposes should be controlled very tightly. Low c-Jun blocks the Schwann cell response to injury and its neuroprotective effects, but high c-Jun perturbs the subsequent remyelination program (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the consequences of low or high c-Jun levels on nerve regeneration. Deletion of c-Jun in Schwann cells leads to slower myelin clearance, slower axon regrowth, and greater loss of neurons after nerve injury. Conversely, overexpression of c-Jun in Schwann cells results in faster myelin clearance but impairs the subsequent remyelination program.

While the functions of c-Jun in Schwann cells become clearer and clearer, how it exactly performs these functions remains somewhat terra incognita. Which transcription factors does c-Jun interact with in Schwann cells? c-Jun can form both homodimers and heterodimers with members of the Fos or ATF/CREB families (van Dam and Castellazzi, 2001). Interestingly, c-Jun, Fosl2, and ATF3 were shown to be similarly upregulated after nerve injury (Arthur-Farraj et al., 2017), suggesting that multiple c-Jun complexes could form in this context. Clarifying which c-Jun complex mediates which function could allow uncoupling the proregenerative role of c-Jun from the myelination-inhibiting role. Which signals underlie c-Jun upregulation upon nerve injury? Among other regulatory mechanisms, phosphorylation of the N-terminal domain of c-Jun by Jun-N-terminal kinase is known to augment its transcriptional activity and stability (Shaulian and Karin, 2001). In Schwann cells, however, N-terminal phosphorylation of c-Jun appears to be dispensable for its function, especially with respect to Schwann cell dedifferentiation and myelin clearance (Parkinson et al., 2008). Finally, what is the role of the repair genes controlled by c-Jun? While it is clear that some repair genes (e.g., Artn and Gdnf) encode neurotrophic factors to support neuron survival and axon regrowth (Fontana et al., 2012), the function of other c-Jun targets in Schwann cells, such as Shh and Runx2, is more enigmatic. Adding these molecular details to the general framework contributed by Fazal et al. (2017) and previous studies will be important to guide future attempts to modulate c-Jun levels in nerve diseases.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: These short reviews of recent JNeurosci articles, written exclusively by students or postdoctoral fellows, summarize the important findings of the paper and provide additional insight and commentary. If the authors of the highlighted article have written a response to the Journal Club, the response can be found by viewing the Journal Club at www.jneurosci.org. For more information on the format, review process, and purpose of Journal Club articles, please see http://jneurosci.org/content/preparing-manuscript#journalclub.

The author declares no competing financial interests.

References

- Arthur-Farraj PJ, Latouche M, Wilton DK, Quintes S, Chabrol E, Banerjee A, Woodhoo A, Jenkins B, Rahman M, Turmaine M, Wicher GK, Mitter R, Greensmith L, Behrens A, Raivich G, Mirsky R, Jessen KR (2012) c-Jun reprograms Schwann cells of injured nerves to generate a repair cell essential for regeneration. Neuron 75:633–647. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur-Farraj PJ, Morgan CC, Adamowicz M, Gomez-Sanchez JA, Fazal SV, Beucher A, Razzaghi B, Mirsky R, Jessen KR, Aitman TJ (2017) Changes in the coding and non-coding transcriptome and DNA methylome that define the Schwann cell repair phenotype after nerve injury. Cell Rep 20:2719–2734. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosius Lutz A, Barres BA (2014) Contrasting the glial response to axon injury in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Dev Cell 28:7–17. 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosius Lutz A, Chung WS, Sloan SA, Carson GA, Zhou L, Lovelett E, Posada S, Zuchero JB, Barres BA (2017) Schwann cells use TAM receptor-mediated phagocytosis in addition to autophagy to clear myelin in a mouse model of nerve injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:E8072–E8080. 10.1073/pnas.1710566114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker L, Desmarquet-Trin-Dinh C, Taillebourg E, Ghislain J, Vallat JM, Charnay P (2006) Peripheral myelin maintenance is a dynamic process requiring constant Krox20 expression. J Neurosci 26:9771–9779. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0716-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazal SV, Gomez-Sanchez JA, Wagstaff LJ, Musner N, Otto G, Janz M, Mirsky R, Jessen KR (2017) Graded elevation of c-Jun in Schwann cells in vivo: gene dosage determines effects on development, remyelination, tumorigenesis, and hypomyelination. J Neurosci 37:12297–12313. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0986-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana X, Hristova M, Da Costa C, Patodia S, Thei L, Makwana M, Spencer-Dene B, Latouche M, Mirsky R, Jessen KR, Klein R, Raivich G, Behrens A (2012) c-Jun in Schwann cells promotes axonal regeneration and motoneuron survival via paracrine signaling. J Cell Biol 198:127–141. 10.1083/jcb.201205025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Sanchez JA, Carty L, Iruarrizaga-Lejarreta M, Palomo-Irigoyen M, Varela-Rey M, Griffith M, Hantke J, Macias-Camara N, Azkargorta M, Aurrekoetxea I, De Juan VG, Jefferies HB, Aspichueta P, Elortza F, Aransay AM, Martínez-Chantar ML, Baas F, Mato JM, Mirsky R, Woodhoo A, et al. (2015) Schwann cell autophagy, myelinophagy, initiates myelin clearance from injured nerves. J Cell Biol 210:153–168. 10.1083/jcb.201503019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Sanchez JA, Pilch KS, van der Lans M, Fazal SV, Benito C, Wagstaff LJ, Mirsky R, Jessen KR (2017) After nerve injury, lineage tracing shows that myelin and Remak Schwann cells elongate extensively and branch to form repair Schwann cells, which shorten radically on remyelination. J Neurosci 37:9086–9099. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1453-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantke J, Carty L, Wagstaff LJ, Turmaine M, Wilton DK, Quintes S, Koltzenburg M, Baas F, Mirsky R, Jessen KR (2014) c-Jun activation in Schwann cells protects against loss of sensory axons in inherited neuropathy. Brain 137:2922–2937. 10.1093/brain/awu257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SY, Shin YK, Park SY, Park JY, Lee HJ, Yoo YH, Kim JK, Park HT (2016) Autophagic myelin destruction by Schwann cells during wallerian degeneration and segmental demyelination. Glia 64:730–742. 10.1002/glia.22957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen KR, Mirsky R (2016) The repair Schwann cell and its function in regenerating nerves. J Physiol 594:3521–3531. 10.1113/JP270874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini R, Fischer S, López-Vales R, David S (2008) Interactions between Schwann cells and macrophages in injury and inherited demyelinating disease. Glia 56:1566–1577. 10.1002/glia.20766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M, Matsuoka I, Wetmore C, Olson L, Thoenen H (1992) Enhanced synthesis of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the lesioned peripheral nerve: different mechanisms are responsible for the regulation of BDNF and NGF mRNA. J Cell Biol 119:45–54. 10.1083/jcb.119.1.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson DB, Bhaskaran A, Droggiti A, Dickinson S, D'Antonio M, Mirsky R, Jessen KR (2004) Krox-20 inhibits jun-NH2-terminal kinase/c-Jun to control Schwann cell proliferation and death. J Cell Biol 164:385–394. 10.1083/jcb.200307132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson DB, Bhaskaran A, Arthur-Farraj P, Noon LA, Woodhoo A, Lloyd AC, Feltri ML, Wrabetz L, Behrens A, Mirsky R, Jessen KR (2008) c-Jun is a negative regulator of myelination. J Cell Biol 181:625–637. 10.1083/jcb.200803013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheib J, Höke A (2013) Advances in peripheral nerve regeneration. Nat Rev Neurol 9:668–676. 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaulian E, Karin M (2001) AP-1 in cell proliferation and survival. Oncogene 20:2390–2400. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topilko P, Schneider-Maunoury S, Levi G, Baron-Van Evercooren A, Chennoufi AB, Seitanidou T, Babinet C, Charnay P (1994) Krox-20 controls myelination in the peripheral nervous system. Nature 371:796–799. 10.1038/371796a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam H, Castellazzi M (2001) Distinct roles of Jun:Fos and Jun:ATF dimers in oncogenesis. Oncogene 20:2453–2464. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber C, Zochodne D (2010) The nerve regenerative microenvironment: early behavior and partnership of axons and Schwann cells. Exp Neurol 223:51–59. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.05.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]