Abstract

Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are pentamers built from a variety of subunits. Some are homomeric assemblies of α subunits, others heteromeric assemblies of α and β subunits which can adopt two stoichiometries (2α:3β or 3α:2β). There is evidence for the presence of heteromeric nAChRs with the two stoichiometries in the CNS, but it has not yet been possible to identify them at a given synapse. The 2α:3β receptors are highly sensitive to agonists, whereas the 3α:2β stoichiometric variants, initially described as low sensitivity receptors, are indeed activated by low and high concentrations of ACh. We have taken advantage of the discovery that two compounds (NS9283 and Zn) potentiate selectively the 3α:2β nAChRs to establish (in mice of either sex) the presence of these variants at the motoneuron-Renshaw cell (MN-RC) synapse. NS9283 prolonged the decay of the two-component EPSC mediated by heteromeric nAChRs. NS9283 and Zn also prolonged spontaneous EPSCs involving heteromeric nAChRs, and one could rule out prolongations resulting from AChE inhibition by NS9283. These results establish the presence of 3α:2β nAChRs at the MN-RC synapse. At the functional level, we had previously explained the duality of the EPSC by assuming that high ACh concentrations in the synaptic cleft account for the fast component and that spillover of ACh accounts for the slow component. The dual ACh sensitivity of 3α:2β nAChRs now allows to attribute to these receptors both components of the EPSC.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Heteromeric nicotinic receptors assemble α and β subunits in pentameric structures, which can adopt two stoichiometries: 3α:2β or 2α:3β. Both stoichiometric variants are present in the CNS, but they have never been located and characterized functionally at the level of an identified synapse. Our data indicate that 3α:2β receptors are present at the spinal cord synapses between motoneurons and Renshaw cells, where their dual mode of activation (by high concentrations of ACh for synaptic receptors, by low concentrations of ACh for extrasynaptic receptors) likely accounts for the biphasic character of the synaptic current. More generally, 3α:2β nicotinic receptors appear unique by their capacity to operate both in the cleft of classical synapses and at extrasynaptic locations.

Keywords: acetylcholine, nicotinic receptors, NS9283, Renshaw cell, stoichiometry, zinc

Introduction

Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are ionotropic receptors with a cationic selectivity, which makes them excitatory. They are pentamers built either from α subunits (homomeric nAChRs) or from α and β subunits (heteromeric nAChRs) (Dani, 2015). Heteromeric nAChRs can associate multiple α and β subunits and in addition, for a given set of α and β subunits, can adopt two stoichiometries noted either 2α:3β and 3α:2β or A2B3 and A3B2 (Marotta et al., 2014). There is evidence for the presence in the CNS of the two stoichiometric variants of heteromeric nAChRs (Marks et al., 1999, 2007; Shafaee et al., 1999; Gotti et al., 2007; DeDominicis et al., 2017). However, until now it has not been possible to assess the presence of a given variant at a specific synapse. We have attempted such a characterization in the spinal cord, at the synapses between the motoneurons (MNs) and the Renshaw cells (RCs), first characterized as cholinergic by Eccles et al. (1954), and in which postsynaptic heteromeric nAChRs mediate a biphasic EPSC, which decays with time constants in the 10 and 100 ms ranges (Lamotte d'Incamps and Ascher, 2008).

The various heteromeric nAChRs differ by a number of properties but in particular by their sensitivity to ACh. Considerable progress has been made recently in characterizing these differences, and in particular to explain why the EC50 of the concentration response relation (CRR) depends on the stoichiometric variant examined. Differences in ACh sensitivity between the two variants built from the same subunits were best described for recombinant receptors associating α4 and β2 subunits (Zwart and Vijverberg, 1998; Nelson et al., 2003; Zhou et al., 2003; Kuryatov et al., 2005; Moroni et al., 2006, 2008; Zwart et al., 2006; Tapia et al., 2007; Carbone et al., 2009). In (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs, the ACh CRR is well fit by a single sigmoid with an EC50 of a few μm. In (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs, the ACh CRR was initially described as monophasic with a high EC50, but more recent studies have shown that it is biphasic with a high sensitivity (HS) region (EC50 ∼1 μm) and a low sensitivity (LS) region (EC50 ∼100 μm) (Harpsøe et al., 2011; Grupe et al., 2013; Eaton et al., 2014). Similar differences were observed for stoichiometric variants of α2β2 and α2β4 nAChRs (Wang et al., 2015). At the molecular level, these differences have been shown to result from the absence or presence of an α-α interface. In (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs, ACh binds (with high affinity) to the two α-β interfaces. In (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs, ACh also binds to the two α-β interfaces but only elicits a partial activation; the full activation requires (low affinity) binding of ACh to the α-α interface (Harpsøe et al., 2011; Mazzaferro et al., 2011, 2014; Eaton et al., 2014), which is thus an ACh “accessory binding site” (Wang et al., 2015). Recently, two compounds have been found to bind to this site and to potentiate the activation of A3B2 receptors by ACh: NS9283 (EC50 of a few μm) (Timmermann et al., 2012; Grupe et al., 2013; Olsen et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015; Mazzaferro et al., 2017; Wang and Lindstrom, 2017) and Zn (100 μm) (Moroni et al., 2008; Mazzaferro et al., 2011).

We have applied these two compounds at the MN-RC synapse and found that NS9283 potentiates both evoked and spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs), whereas Zn potentiates sEPSCs. A caveat introduced by the observation that NS9283 is an inhibitor of AChE was lifted when we found that this effect plays a minor role at concentrations of NS9283 up to 10 μm. Thus, A3B2 nAChRs are present at the MN-RC synapse, and because of their dual ACh sensitivity can mediate both components of the EPSCs: the fast component involves binding of ACh to the three interfaces of synaptic cleft receptors, whereas the slow component involves binding of ACh to the α-β interfaces of extrasynaptic receptors.

Materials and Methods

All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations at Université Paris Descartes (ethical committee authorization CEEA34.BLDI.068.12).

Animals and slice preparation.

The mice used (of either sex) were either wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J mice (Janvier) or knock-out lines for the β2 nAChR subunits: β2−/− (Picciotto et al., 1995) or α7−/− β2−/− (Somm et al., 2014) obtained by crossing β2−/− mice with α7−/− mice (Orr-Urtreger et al., 1997). All mutants were bred as homozygous; confirmation of the genotype of the mice was made whenever necessary with the appropriate PCR from small samples collected at P5.

The mice (P5-P10) were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 0.1–0.2 ml xylazine (0.25 mg/ml) and ketamine (3 mg/ml). The dissection and the slicing were performed as described previously (Lamotte d'Incamps et al., 2012). Slices were then transferred into ACSF containing the following (in mm): NaCl 130, KCl 2.5, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1, NaH2PO4 1.0, NaHCO3 26, glucose 25, Na-ascorbate 0.4, Na-pyruvate 2, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, pH 7.4. For the Zn experiments, NaH2PO4 and NaHCO3 were replaced by HEPES (10 mm) and NaCl concentration was raised to 145 mm. After a 30 min incubation in ACSF at 34°C, slices were maintained at room temperature (18°C–24°C).

Biochemistry.

Recombinant mouse AChE (mAChE) was a generous gift from Pr. Palmer Taylor (University of California–San Diego). Stock solutions of NS9283 were prepared as 20 mm in 1 m HCl, and further dilutions were prepared in HEPES buffer (0.1 m; pH 7.4). Reversible inhibition of mAChE by compound NS9283 was measured in a medium (0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4), which contains substrate acetylthiocholine iodide (ATC) (Sigma-Aldrich) (range 0.1–1 mm) and reagent 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (0.3 mm) according to the Ellman method (Ellman et al., 1961) at 415 nm and 25°C, using a Bio-Rad microplate reader. Additionally, control enzyme activity without the inhibitor was measured. There was no spontaneous hydrolysis of ATC with NS9283, and no solvent interference on AChE activity in the tested range of NS9283 (0.2–9 μm). Higher concentrations of NS9283 could not be used due to solvent inhibition. The inhibition constants were evaluated from the effect of ATC concentration(s) on the degree of inhibition by NS9283 (at concentration I) according to the equation: v = Vm × s/(Km(1 + I/Ki) + s), which describes the noncompetitive inhibition and from which the dissociation constant Ki was calculated (Cornish-Bowden, 2012). The value of the Km in the absence of NS9283 was 0.10 ± 0.01 mm, similar to the values obtained on the same enzyme by Šinko et al. (2010).

Electrophysiology.

HEKA EPC-9 or Molecular Devices Axopatch 200B amplifiers were used for data acquisition. Whole-cell recordings were filtered at 3 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. Series resistance (range 8–30 Mohms) was corrected (60%) in most recordings of sEPSCs and in all the recordings of EPSCs evoked by ventral root (VR) stimulation.

The recording chamber was continuously perfused with ACSF at a rate of ∼1 ml/min. RCs were first identified by their characteristic response to VR stimulation and voltage-clamped in the whole-cell configuration. Patch pipettes had an initial open-tip resistance of 3.5 to 6 MOhms. The internal solution contained the following (in mm): Cs-gluconate 125, spermine 10, QX-314 Cl 5, HEPES 10, EGTA or BAPTA 10, CaCl2 1, Mg-ATP 4, and Na2GTP 0.4. The pH was adjusted to 7.3 with CsOH, and the osmolarity to 285–295 mOsm. Membrane potentials were corrected for the liquid junction potential (Vj = −15 mV). Except when indicated otherwise, the recordings illustrated were obtained at −60 mV. The glutamatergic components of the EPSCs were suppressed by adding NBQX (2 μm) to block AMPARs and d-APV (50 μm) to block NMDARs. α7 nAChRs were blocked by methyl-lyc-aconitine (10 nm). GABAergic and glycinergic currents were blocked by SR 95531 (gabazine, 3 μm) and strychnine (1 μm). Stock solutions of NS9283 were prepared at 20 mm in DMSO. NBQX, d-APV, gabazine, NS9283 (3-[3-(3-pyridyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl]benzonitrile), and sazetidine-A (saz-A) (6-(5-(((S)-azetidin-2-yl)methoxy)pyridine-3-yl)hex-5-yn-1-ol) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience and Ascent, except for an initial gift of NS9283 from Dr Dan Peters. Galantamine hydrobromide was from Abcam, and QX-314 chloride was from Alomone Labs. All other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Analysis of EPSCs.

Evoked EPSCs (eEPSCs) (elicited by stimulation of the VR) and sEPSCs were analyzed with Neuromatic (www.Thinkrandom.com) as described previously (Lamotte d'Incamps et al., 2012). We analyzed the eEPSCs evoked by single pulses (1p) and by 5 pulse trains (5p, frequency 100 Hz). Stimulations (either 1p or 5p) were repeated at 10 s intervals. In all figures, eEPSCs are shown as averaged records of 10 responses, whereas sEPSCs are shown as average of as many events could be collected during the experiment. The decay time constants were measured by fitting a double exponential after the peak of the last EPSC from the response in the RC. The two components of the fit were each described by their amplitude and their time constant: <a1, τ1> is the fast component of the decay and <a2, τ2> the slow one. a11p, τ11p, a21p, and τ21p are the values calculated for the responses to a single pulse, a15p, τ15p, a25p, and τ25p those calculated for the decay from the peak of the response to the fifth pulse of a train. The weighted decay time was calculated as τw = (a1 × τ1 + a2 × τ2)/(a1 + a2). The double exponential fit assumes that both components reach their peak at the same time, but, as we discussed previously, the slow component has probably a slower rise than the fast one (Lamotte d'Incamps et al., 2012). In such a case, the rise of <a2, τ2> will overlap with the decay of <a1, τ1>, and the fit will overestimate the value of τ1. Moreover, if there is a change in the second component, the estimate of the parameters of the first component will suggest a change even if there is not actually one. This difficulty, which could not be resolved as we have not been able to eliminate selectively the fast component to evaluate the rise of the second, complicates the interpretation of the effects of NS9283 on the first component of the EPSC. In the experiment illustrated in Figure 1A, the early decay of the 1p-EPSCs was clearly not affected by NS9283 and yet the double exponential fit suggested a reduction of τ1 from 10.2 to 8.3 ms (see Fig. 1A). The peak of the 1p-EPSC was slightly reduced (from 462 to 419 pA), but the calculated value of a1 was reduced from 377 to 300 pA. In Figure 1B, the peak of the 5p-EPSC increased from 569 pA to 579 pA and the early decay was unchanged, but the values from the fit suggested a decrease of a15p from 412 to 260 pA and of τ15p from 13.8 to 10.9 ms. Overall, our quantitative analysis of the second component was robust but the quantification of the fast component remained approximate.

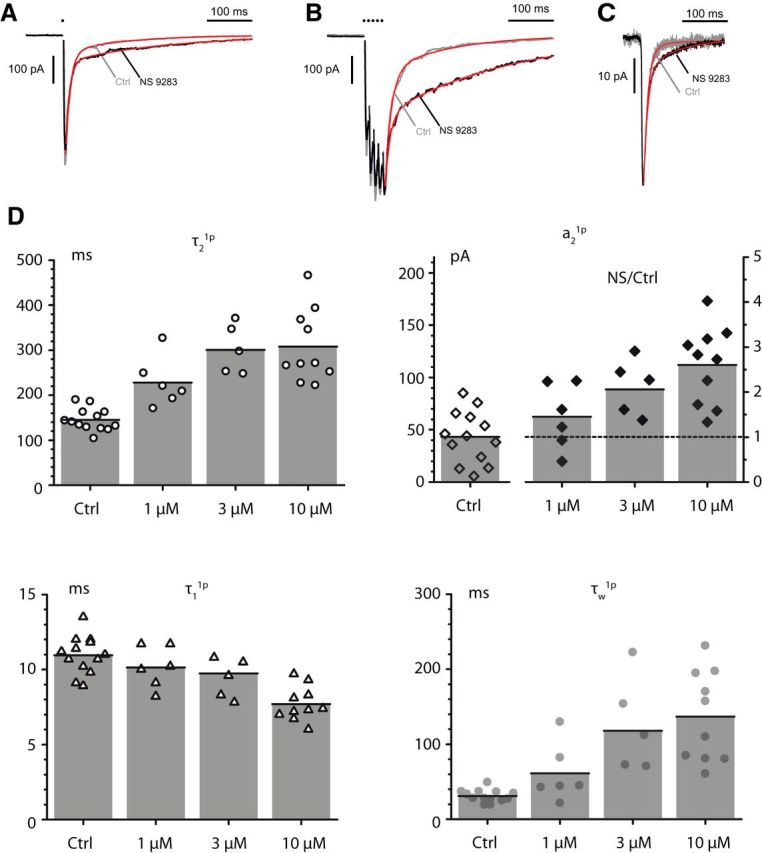

Figure 1.

NS9283 potentiates and prolongs the slow component of the MN-RC nicotinic eEPSC (A, B) and prolongs the sEPSCs (C). The eEPSCs were elicited by a stimulation of the VR with one pulse (1p, A) or five pulses (5p, 100 Hz, B). The decay was fitted by two exponentials, which defined four parameters: the amplitudes (a1, a2) and the decay time constants (τ1, τ2) of the fast and slow components. The weighted time constant τw combined these four values. A, Effect of NS9283 (10 μm) on a 1p eEPSC. CTL: a1 377 pA, a2 62 pA, τ1 10.2 ms, τ2 129 ms, τw 27 ms. NS9283: a1 300 pA, a2 98 pA, τ1 8.3 ms, τ2 222 ms, τw 60.9 ms. B, Effect of NS9283 (10 μm) on a 5p eEPSC (same cell as in A). CTL: a1 412 pA, a2 132 pA, τ1 13.8 ms, τ2 144 ms, τw 45.4 ms. NS9283: a1 260 pA, a2 291 pA, τ1 10.9 ms, τ2 274 ms, τw 150 ms. C, Effect of NS9283 (10 μm) on sEPSCs (same cell as in A, B). CTL average of 54 events, NS9283 average of 245 events. CTL: a1 −19.7 pA, a2 −1.0 pA, τ1 9.2 ms, τ2 51.2 ms, τw 11.2 ms. NS9283: a1 −16.4 pA, a2 −4.5 pA, τ1 8.8 ms, τ2 76.4 ms, τw 23.3 ms. D, Effects of three concentrations of NS9283 (1, 3, 10 μm) on the values of τ2, a2, τ1, and τw for 1p eEPSCs. The values of the three time constants, which do not vary significantly as a function of the intensity of the VR stimulation, were plotted directly for each NS9283 concentration. For a2, however, the value depends on the intensity of stimulation, which changes the number of axons excited, and this leads to the variability illustrated in the left part of the graph for the control value (Ctrl). To evaluate the effects of NS9283, we plotted the value of the ratio of the amplitude measured in NS9283 over that measured in control (right ordinate scale). For τ1, the values were those measured from the double exponential fit assuming that both components start at time 0, but, as discussed in Materials and Methods, this assumption leads to an apparent decrease, which disagrees with the observation (A, B) that the decay of the early component of the EPSC is not changed by NS9283.

For sEPSCs, the fit was only made on averaged records. The detection threshold was set between −7 and −12 pA depending on the background noise level, which was increased by some of the compounds having anti-AChE effects (see Results). The relatively high value of the threshold resulted in a slight overestimate of the mean amplitude, due to the absence of correction for the missed small events. In our early analysis of the decay of spontaneous and miniature EPSCs, we fit the decay with single exponentials because we were not able to detect a slow component (this observation was one of our reason to suggest that the slow component of the eEPSC reflects activation by spillover of extrasynaptic receptors). The fact that under NS9283 a slow component appears in sEPSCs (see Fig. 1C) suggested the possibility that a small slow component could be already present in sEPSCs in control conditions; indeed, when we reevaluated our data using longer time bases than that used in our early analysis, we could actually identify a slow component. However, this component was small; and in many cases in which an overall slowing could be well documented, it was difficult to separate the contributions to the slowing of changes of a2 and changes of τ2 (see Fig. 6).

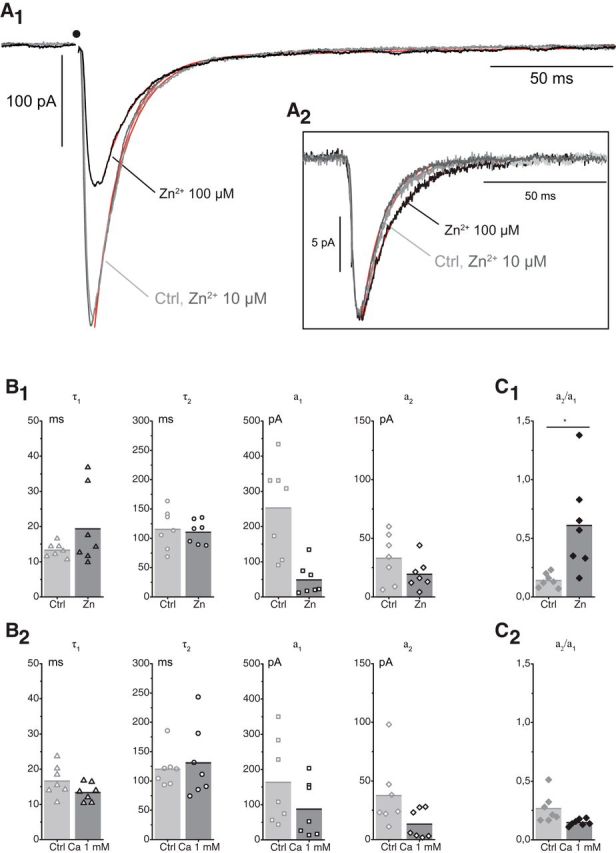

Figure 6.

Effects of Zn (10 and 100 μm) on the sEPSCs and the eEPSCs. A1, Effects of Zn (10 and 100 μm) on eEPSCs (10 traces). CTL: a1 −308 pA, a2 −25.4 pA, τ1 10.6 ms, τ2 81.3 ms, τw 16.0 ms. Zn 10 μm: a1 −293 pA, a2 −25.9 pA, τ1 11.4 ms, τ2 78.4 ms, τw 16.8 ms. Zn 100 μm: a1 −134 pA, a2 −21.3 pA, τ1 12.6 ms, τ2 87.7 ms, τw 22.9 ms. A2, Effects of Zn (100 μm) on the sEPSCs (inset) (same experiment as in A1). The records illustrated correspond to sEPSCs recorded on a 150 ms time base and fit with a single exponential (control: 194 events, −12 pA, td 8.8 ms; Zn 10 μm: 356 events, −14.5 pA, td 9.1 ms; Zn 100 μm: 592 events −13 pA, td = 12.8 ms). The values of the kinetic parameters for a dual exponential fit were also measured on a 540 ms time base, but this reduced the number of events. B1, Effects of Zn (100 μm) on eEPSCs. There was no significant change in the two time constants of the decay. The reduction of the amplitude was more important for a1 than for a2. B2, Effects on eEPSCs of reducing the external Ca concentration from 2 to 1 mm. There was no significant change in the two time constants of the decay. The reduction of the amplitude was slightly higher for a1 than for a2, leading to a slight increase in the ratio a2/a1 (p = 0.016; n = 7). C, Ratio of the two amplitudes a1 and a2 in presence of Zn (100 μm) and in reduced Ca (1 mm). The ratio is increased by Zn from 0.14 ± 0.06 to 0.61 ± 0.41 (n = 7; p = 0.01; C1) and unchanged (control 0.27 ± 0.12; reduced Ca 0.15 ± 0.03; n = 7; p = 0.07 bilateral paired t test) when the release is reduced presynaptically by lowering the Ca concentration (C2).

The changes in the variance of the holding current were measured with Neuromatic on records 500 ms long. The “apparent elementary current,” iel, was calculated as the ratio between the change of the holding current over the change of variance.

Experimental design and statistical analysis.

Electrophysiological recordings were obtained from spinal cord slices of young (P6-P10) mice of either sex. One cell per slice was recorded to avoid residual effects of the compounds used. Experiments were repeated at least three times in slices obtained from several animals. One-sample t tests, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney, paired t tests, or Welch tests in the case of unpaired data were used to assess the difference between two samples (the tests were unilateral unless noted). Values are given as mean ± SD.

Results

NS9283 amplifies the slow component of eEPSCs and prolongs both evoked and sEPSCs

Our previous analysis of the synaptic currents mediated by heteromeric nAChRs at the MN-RC synapse had led us to propose that LS receptors are responsible for the fast component of the eEPSC, whereas HS receptors account for the slow component (Lamotte d'Incamps et al., 2012). However, the data on the ACh sensitivity of the various stoichiometric variants of nAChRs left open whether the HS receptors mediating the slow component are A2B3 receptors or A3B2 receptors operating at the foot of their CRR (Lamotte d'Incamps and Ascher, 2014). The discovery that NS9283 selectively potentiates A3B2 receptors offered a tool to answer this question because it predicted that NS9283 would potentiate the slow component if this component involves A3B2 receptors.

Timmermann et al. (2012) first established that NS9283 selectively potentiates the stoichiometric variants of α4β2 recombinant receptors expressing a high α4/β2 ratio and therefore consisting mostly of A3B2. Grupe et al. (2013) analyzed the effects of NS9283 on the ACh CRR of these receptors. In control conditions, the ACh CRR has a first limb with an EC50 close to 1 μm and a second larger limb with an EC50 of ∼100 μm, as first described by Harpsøe et al. (2011). Under a saturating concentration of NS9283 (∼10 μm), the ACh CRR becomes monophasic with an EC50 close to 1 μm.

To analyze the effects of NS9283 on the eEPSCs, we applied it at 1, 3, and 10 μm (the peculiar effects of higher concentrations will be described in a separate section). We observed that the slow component of the EPSC was amplified and its decay slowed. This is illustrated for NS9283 at 10 μm in Figure 1A, B both for 1p and 5p stimulations. The analysis of the time constants (τ1 and τ2) and the amplitudes (a1 and a2) of the two components of the decay showed that the time constant of the fast component (τ1) was slightly shortened by NS9283, whereas the time constant of the slow component (τ2) was markedly increased. Figure 1D illustrates the results of multiple experiments in the case of 1p-EPSCs. The most visible change was the increase of τ2, which in control had a mean value of 145 ± 25 ms (n = 13) and increased by a factor of 1.6 ± 0.2 (n = 6, t(5) = −5.8138, p = 0.0011, paired t test) with NS9283 1 μm, 2.1 ± 0.4 (n = 5, t(4) = −6.7618, p = 0.0012) for NS9283 3 μm and 2.1 ± 0.6 (n = 10, t(9) = −6.5197, p = 0.00005) for NS9283 10 μm. In parallel, the amplitude of the slow component (a2) increased. Because the values of the amplitudes are very variable across experiments and, contrary to the time constants, depend on the intensity of the stimulation of the VR, we used the ratio of the value under NS9283 over the control value in a given experiment to represent the increase of a2. The mean control value of a2 was 43.3 ± 24.9 pA (n = 13). It increased by a factor of 1.45 ± 0.72 (n = 6, t(5) = −1.7134, not significant, p = 0.074) with NS9283 1 μm, 2.1 ± 0.6 (n = 5, t(4) = −11.6216, p = 0.00016) for NS9283 3 μm and 2.60 ± 0.86 (n = 10, t(9) = −3.9035, p = 0.0018) for NS9283 10 μm. Both a1 and τ1 showed a significant decrease for NS9283 10 μm: a1 was reduced by 41% from 318 ± 96 pA down to 188 ± 63 pA (n = 10, t(9) = −10.4010, p = 1.39e−6) and τ1 from 11.1 ± 1.3 ms down to 7.7 ± 1.2 ms (t(9) = −5.3215, p = 0.00024). The weighted time constants increased at all three concentrations. With NS9283 10 μm, the weighted time constant for the 1p EPSC (τw1p) rose from 31.0 ± 8.2 ms (n = 13) to 136.8 ± 60.6 ms (n = 10, t(9) = −5.9851, p = 0.00010, paired t test with the corresponding controls) and the weighted time constant for the 5p-EPSC (τw5p) rose from 64.6 ± 21.2 ms to 194.2 ± 65.5 ms (n = 8, t(7) = −7.2478, p = 0.00009). As discussed in Materials and Methods, the reductions of a1 and τ1 are likely to be largely artifactual and due to the fact that we could not correct for the fact that the slow component rises slowly. NS9283 at concentrations of 1–10 μm did not significantly affect the peak of the EPSC evoked by VR stimulation when tested shortly after the drug application (10 min). A decrease of the EPSC often occurred on a longer time scale but was also observed in the absence of the drug, and likely to be linked with a presynaptic fatigue. Thus, the major effect of NS9283 on the eEPSC appears to be an increase of the slow component.

The fact that in the case of the eEPSCs NS9283 acts mainly on the slow component led us to examine its effects on the sEPSCs. In our initial study of the nicotinic EPSCs mediated by heteromeric receptors in the RC (Lamotte d'Incamps et al., 2012), we had fitted the decay of the sEPSCs by a single exponential with a time constant close to that of the fast component of the fast eEPSC. We had not seen a slow component but suspected its presence (Lamotte d'Incamps and Ascher, 2014) and indeed could detect it when we used a longer time base (500 ms) than in our initial study and forced a two-exponential fit on the decay of the averaged records (Fig. 1C). The sEPSCs were compared in control conditions and in NS9283 (10 μm). After addition of NS9283 10 μm, the decay of the sEPSCs was slowed, as illustrated in Figure 1C. The weighted time constant (τw) increased from 15.2 ± 4.9 ms in control to 26.5 ± 9.9 ms (n = 7, t(6) = −4.7813, p = 0.0015). There were no significant changes in the values of the amplitudes of the two components (a1 went from 12.3 ± 5.5 to 16.4 ± 10.0 pA; n = 7, t(6) = −0.6314, p = 0.28, and a2 went from 3.5 ± 3.0 to 4.8 ± 1.4 pA; n = 7, t(6) = −0.7062, p = 0.25, bilateral paired t tests). The prolongation of the decay τw involved both a slowing of the decay of the first component (from τ1 = 7.4 ± 2.7 ms in control to τ1 = 9.1 ± 1.7 ms in presence of NS9283 10 μm; n = 7, t(6) = −2.4648, p = 0.024) and an increase of τ2 (from 53.8 ± 37.7 ms up to 86.6 ± 43.6 ms; n = 7, t(6) = −2.7115, p = 0.018).

The fact that NS9283 potentiates eEPSCs and sEPSCs strongly suggests that A3B2 nAChRs are present at the MN-RC synapse. The observation that NS9283 potentiates the slow components of the synaptic currents supports the hypothesis that the HS receptors are mostly A3B2 receptors operating at the foot of their biphasic CRR.

NS9283 potentiates the currents induced by nicotinic agonists

The effects of NS9283 on the EPSCs strongly suggest the presence of A3B2 nAChRs on the RC but do not exclude the simultaneous presence of A2B3 receptors. To try to identify these receptors, we made use of the observations indicating that many nAChR agonists affect differentially the two stoichiometric variants so that the responses they elicit differ in the ratio of the currents due to A3B2 and A2B3 nAChRs. Because the potentiation by NS9283 only affects A3B2 receptors, it should be larger for agonists preferentially activating A3B2 receptors than for those preferentially activating A2B3 receptors. To test this hypothesis, we selected four agonists: carbachol, nicotine, cytosine, and saz-A. Carbachol was selected as an analog of ACh because of the observation (discussed in a later section) that NS9283 is an inhibitor of AChE. The other three agonists (all insensitive to AChE) were selected because, at least in the case of α4β2 nAChRs, they act in different proportions on the A2B3 and A3B2 nAChRs: nicotine acts on both A3B2 and A2B3 nAChRs, cytisine has no agonist effect on A2B3 nAChRs, and saz-A has more marked effects on A2B3 than on A3B2 nAChRs.

Fast application of agonists was difficult in our experimental conditions as the cells recorded from are situated rather deep in the slices (at least 50–100 μm from the surface). We therefore selected to bath apply the agonists and minimize desensitization by using low concentrations. These “low” concentrations were defined as lower or close to the EC50 values of the high-affinity α-β interfaces deduced from the CRRs of A2B3 nAChRs and from the foot of the biphasic CRRs of A3B2 nAChRs. Thus, we could assume that most of the α-α interfaces were not occupied by the agonist and accessible to NS9283. The low concentrations of agonists induced inward currents that were steady for over a few minutes. The stability of these currents does not indicate that the receptors were not partly desensitized (Pidoplichko et al., 1997; Paradiso and Steinbach, 2003) and indeed the agonists induced a long-lasting depression of the EPSCs that was likely due to desensitization, as described below. The stability only indicated that a steady state was reached in the window defined by the intersection of activation and desensitization relationships (Pidoplichko et al., 1997; Lester, 2004; Benallegue et al., 2013; Campling et al., 2013; Grupe et al., 2013).

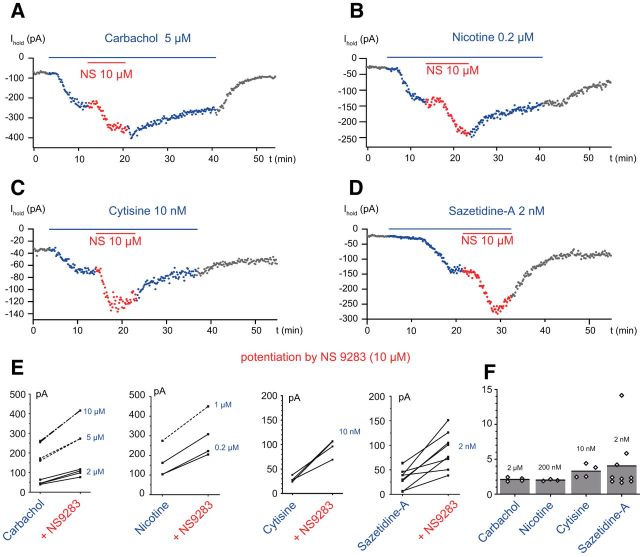

Carbachol was applied at 2, 5, and 10 μm. The EC50 of carbachol for α4β2 nAChRs was measured as 17 μm by Eaton et al. (2003) in experiments in which the EC50 for the HS limb of the (α4)2(β2)3 ACh CRR was 1.7 μm. At 2 μm, carbachol induced currents of a few 10s of pA (43.5 ± 11.7 pA, n = 6) and at 10 μm currents of a few 100 pA (241.0 ± 65.3 pA, n = 5; Fig. 2A,E). At higher concentrations, the peak currents could reach several nA but could not be clamped adequately and were always decreasing rapidly. NS9283 (10 μm) potentiated the currents induced by carbachol at 2 and 10 μm. The mean potentiation was 2.1 ± 0.3 (n = 4, p = 0.014, t(3) = 8.0617, p = 0.0020) for carbachol 2 μm (Fig. 2F) and 1.57 ± 0.09 (n = 4, t(3) = 13.0481, p = 0.00049) for carbachol 10 μm.

Figure 2.

NS9283 potentiates the currents induced by the exogenous application of nicotinic agonists. Agonists were applied until the response reached steady state before adding NS9283 (10 μm) for ∼10 min. A, Carbachol 5 μm. B, Nicotine 0.2 μm. C, Cytisine 10 nm. D, saz-A 2 nm. E, Summary of the effects obtained in multiple experiments with various concentrations of agonists: carbachol (2, 5, and 10 μm), nicotine (0.2 and 1 μm), cytisine (10 nm), and saz-A (2 nm). F, Mean values of the potentiation induced by NS9283 on the responses to the four agonists. Carbachol 2 μm: 2.1 ± 0.3 (n = 4). Nicotine 0.2 μm: 2.0 ± 0.1 (n = 3). Cytisine 10 nm: 3.3 ± 1.0 (n = 4). saz-A 2 nm: 4.0 ± 4.0 (n = 9).

Nicotine was applied at 0.2 and 1 μm, two values in the range of the EC50 values measured in A2B3 recombinant nAChRs containing β2 subunits (Nelson et al., 2003; Moroni et al., 2006; Anderson et al., 2009; Campling et al., 2013), and lower than the EC50 values for the main (LS) limb of A3B2 nAChRs measured by the same authors. Nicotine at 0.2 μm induced a current of 123.3 ± 33.5 pA (n = 3) and at 1 μm a current of 215 ± 93 pA (n = 5). NS9283 (10 μm) potentiated the nicotine induced current by 2.0 ± 0.1-fold at 0.2 μm (n = 3) and by 1.6-fold (n = 1) at 1 μm (Fig. 2B,E,F).

Cytisine was applied at concentrations ranging from 10 nm to 1 μm. Cytisine has no agonist effect on α4β2 A2B3 receptors and is a partial agonist of α4β2 A3B2 receptors (Papke and Heinemann, 1994; Houlihan et al., 2001; Eaton et al., 2003; Nelson et al., 2003; Moroni et al., 2006; Carbone et al., 2009; Mazzaferro et al., 2011; Campling et al., 2013; Marotta et al., 2014). Most studies have described the activation of A3B2 receptors by a single sigmoid with an EC50 between 1 and 16 μm (Eaton et al., 2003; Nelson et al., 2003; Moroni et al., 2006; Carbone et al., 2009; Mazzaferro et al., 2011; Campling et al., 2013; Marotta et al., 2014). However, Papke and Heinemann (1994), in their pioneering study of the effects of cytisine on α4β2 receptors which were likely A3B2 receptors, noted that the CRR had two components: with a first plateau at concentrations of ∼100 nm and a second plateau at concentrations >30 μm (Houlihan et al., 2001). By analogy with the CRR for ACh and nicotine on A3B2 nAChRs, these observations suggested that the action of cytisine on (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs involves both the α-β and the α-α interfaces, that the EC50 value in the μm range measured by most authors corresponds to that of the LS limb of the CRR, and that the EC50 of the HS limb is in the range of 10 nm. The currents induced by cytisine at 10 nm were 29.5 ± 6.0 pA (n = 4). The relatively small size of these currents is in agreement with the claim that cytisine is a partial agonist. NS9283 potentiated the responses to 10 nm cytisine by a factor of 3.3 ± 1.0 (n = 4, t(3) = 4.7527, p = 0.0089; Fig. 2C,E,F). Higher concentrations of cytisine (1 μm) induced larger currents (145 ± 69 pA, n = 7), but these currents were not stationary and decreased during the application. NS9283 (10 μm) was applied in three experiments and induced a transient increase of a few 10s of pA on the falling limb of the response.

saz-A was applied at concentrations of 2–50 nm. saz-A binds exclusively to the α-β interfaces of α4β2 nAChRs. It is a full agonist on α4β2 A2B3 receptors, and it is a partial agonist with low efficacy (0.05% to 19%) on α4β2 A3B2 receptors (Zwart et al., 2008; Carbone et al., 2009; Mazzaferro et al., 2011; Eaton et al., 2014; Indurthi et al., 2016). The reported EC50 values for the activation of A2B3 and A3B2 α4β2 nAChRs in expression systems range from a few nm to 23 nm (Zwart et al., 2008; Carbone et al., 2009; Mazzaferro et al., 2011; Eaton et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015; Indurthi et al., 2016). At a concentration of 2 nm, saz-A induced inward currents of 35.6 ± 21.0 pA (n = 9). These currents were potentiated by NS9283 (10 μm) and reached 90.1 ± 35.5 pA (n = 9) (Fig. 2D–F). Higher concentrations of saz-A induced rather large currents: 171 ± 136 pA (n = 4) at 5 nm and 433 ± 211 pA (n = 5) at 50 nm. In 3 of 5 cases, the responses to saz-A 50 nm were not stationary and decreased with time, suggesting that desensitization was progressively overcoming activation. In the other 2 cases, the current was stationary. The responses to saz-A 50 nm were not potentiated by NS9283: the mean current value was 583 ± 68 pA for saz-A and 595 ± 81 pA for saz-A + NS9283 (n = 3). The absence of potentiation for “high” concentrations of saz-A (50 nm) is likely explained by the fact that NS9283 shifts to the left both the activation CRR and the desensitization CRR as seen with ACh (Grupe et al., 2013), which means that the highest agonist concentrations that initially induced a steady-state current are now out of the range defining the “window currents.”

Our choice of the four agonists on which we analyzed the steady-state effects of NS9283 was guided by the hope that, because these agonists do not activate in the same proportions A3B2 and A2B3 nAChRs, differences in the degree of potentiation by NS9283 could reveal the presence of A2B3 receptors. This hope was not fulfilled because the maximal potentiations were of similar magnitude for the four agonists tested (carbachol, nicotine, cytisine, saz-A) (Fig. 2F) and the weak trend suggesting a larger effect in the case of saz-A is not consistent with our hypothesis: if both A3B2 and A2B3 are present, the response to saz-A should be dominated by that of A2B3 variants and thus should be less potentiated by NS9283 than responses involving a comparable activation of the two isoforms, or a preferential activation of A3B2. The activation of A2B3 nAChRs by saz-A may be masked by a preferential desensitization of these receptors (Campling et al., 2013; Eaton et al., 2014). An alternative explanation of the results is that there are actually very few A2B3 nAChRs in the RCs.

Carbachol, nicotine, and cytisine all reduced the amplitude of the EPSCs. A reduction to <50% of the control was observed for carbachol 5 μm (44 ± 8%, n = 5, t(4) = −14,8834, p = 0.000059), nicotine 1 μm (46 ± 13%, n = 5, t(4)= −9.6988, p = 0.00032), and cytisine 0.1 μm (37 ± 27%, n = 4, t(3) = −4.6806, p = 0.0092). After washing out the agonist, we observed a nearly complete recovery of the EPSC in a few cases in which the agonist had been applied at a low concentration and for <10 min. For longer applications or for “high” concentrations (nicotine 10 μm, cytisine 1 μm), the EPSC amplitude did not recover, which may indicate that the receptors had entered a long desensitized state (Pidoplichko et al., 1997; Paradiso and Steinbach, 2003). One cannot exclude that part of the depression involves presynaptic effects (McGehee et al., 1995). saz-A 2 nm reduced the amplitude of the EPSC to 83 ± 12% of its control value (n = 10, t(9) = −4.6724, p = 0.00058), with no significant effect on the decay time constants (control τw = 50.7 ± 33.8 ms, saz-A τw = 58.5 ± 46.8 ms, n = 8, t(7) = −0.931, p = 0.38). This is consistent with the observation that, in the nm concentration range, saz-A produces little desensitization of (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs (Eaton et al., 2014). saz-A 50 nm reduced the EPSCs to 47 ± 20% of its control value (n = 5, t(4) = −6.0809, p = 0.0019) and after washing out saz-A the reduction persisted despite the recovery of the saz-A induced current.

The fact that NS9283 potentiates the currents induced by ACh agonists not hydrolyzed by ACh and known to activate A3B2 nAChRs reinforces the conclusion that these receptors are present at the MN-RC synapse. The similarity between the effects of NS9283 on the currents induced by agonists activating in different proportions A3B2 or A2B3 nAChRs suggests that, if A2B3 receptors are present at the synapse, they are not abundant.

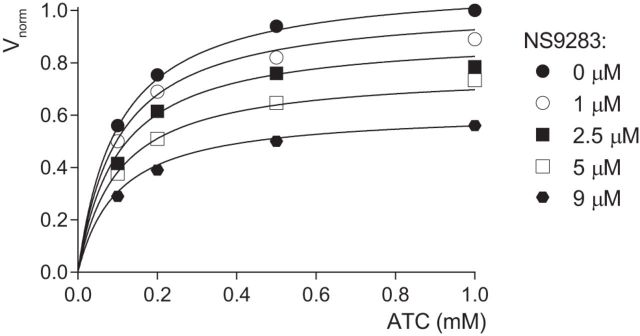

NS9283 is a noncompetitive inhibitor of AChE

Although the prolongation by NS9283 of the heteromeric nicotinic EPSC was that expected from a potentiation of A3B2 nAChRs, it also resembled the prolongation of the EPSC induced by the AChE inhibitor neostigmine (Lamotte d'Incamps et al., 2012). We thus wondered whether NS9283 had any effect on AChE and assayed the effect of NS9283 on the catalytic activity of purified mouse recombinant AChE using the Ellman method (see Materials and Methods). The results showed that NS9283 is indeed an AChE inhibitor (Fig. 3). The reduction of the AChE activity increased with the concentration of NS9283, but the Km of the concentration-activity relation of AChE (0.10 ± 0.01 mm) was unchanged, indicating a noncompetitive inhibition. The Ki was evaluated (see Materials and Methods) as 11.2 μm.

Figure 3.

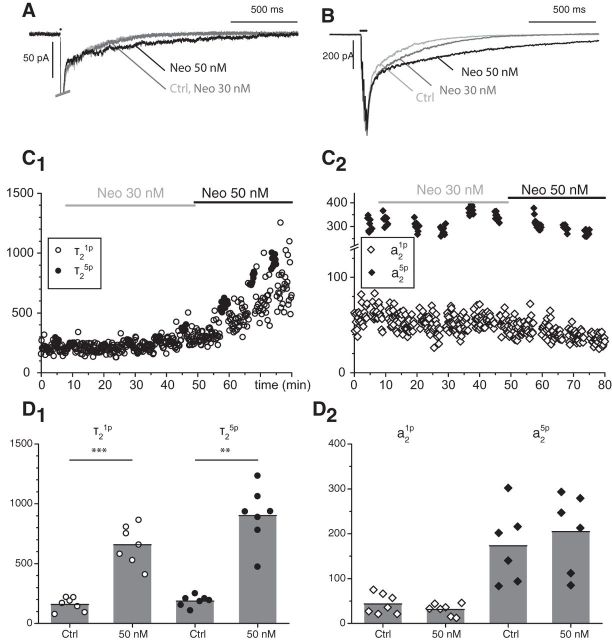

NS9283 is a noncompetitive inhibitor of AChE. NS9283 was applied at concentrations ranging from 1 to 9 μm. The AChE activity of mouse recombinant AChE was measured with ATC in the concentration range of 0.1 to 1.0 mm. The velocity of hydrolysis of ATC is expressed as Vnorm defined as v/Vmax (where v is the velocity in a given condition and Vmax is the maximum velocity measured in the absence of inhibitor). The Km measured in the absence of NS9283 was 0.10 ± 0.01 mm. NS9283 shows a noncompetitive inhibition profile. The Ki was evaluated (see Materials and Methods) as 11.2 ± 0.8 μm (three experiments).

The observation that NS9283 has some anti-AChE effects raised the possibility that some of the prolongation of the EPSC decay by NS9283 could result from AChE inhibition, even if such an inhibition cannot explain that NS9283 potentiates the responses to agonists not hydrolyzed by AChE (carbachol, nicotine, cytisine, saz-A). To evaluate this possibility, we compared in detail the effects of NS9283 and those of neostigmine, which we had used in our previous study (Lamotte d'Incamps et al., 2012). Because the concentration of NS9283 used in most of our experiments (10 μm) was close to the Ki measured biochemically (11.2 μm), we initially selected a concentration of neostigmine close to the Ki of 7 nm measured in biochemical experiments by Santillo and Liu (2015). At this concentration, no effect on the EPSCs was detected. An effect was detected for neostigmine 30 and 50 nm (Fig. 4). It developed slowly and did not show a clear plateau over a period of 30 min. We measured it at a time between 20 and 30 min after the beginning of the application. For 30 nm, the effect was most marked for τ25p, which increased by ∼50% (1.56 ± 0.29, n = 3, t(2) = 3.3289, p = 0.040). At 50 nm, there was a more marked prolongation, by a factor of 4.70 ± 2.54 (n = 7, t(6) = −8.8115, p = 5.9e−5) for τ21p and 5.24 ± 2.82 (n = 7, t(6) = −7.6157, p = 0.00013) for τ25p (Fig. 4D1). In contrast, neostigmine had very limited effects on a2 (Fig. 4D2): at 30 nm, there was no significant change in a21p and a25p; at 50 nm, a21p was actually reduced by a factor of 0.76 ± 0.24 (n = 7; t(6) = −2.6236, p = 0.0197), whereas no change could be detected in a25p. Over longer applications, a2 tended to decrease, possibly due to desensitization of the receptors by ambient ACh (Lamotte d'Incamps et al., 2012).

Figure 4.

Neostigmine prolongs the slow component of the eEPSC but does not increase its amplitude. A–C, Neostigmine was applied at 30 nm and then at 50 nm. A, B, Average of 10 EPSCs. A, 1p-EPSCs. B, 5p-EPSCs. C, Time course of the changes of τ21p (C1, open circles), τ25p (C1, filled circles), a21p (C2, open diamonds), and a25p (C2, filled diamonds) after addition of neostigmine. D, Bar graphs represent the average changes of τ2 (D1) and a2 (D2) induced by neostigmine (50 nm) for 1p-EPSCs and 5p-EPSCs. Neostigmine only increased τ2, whereas NS9283 increased both τ2 and a2 (Fig. 1). **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

The very slow development of the effect of neostigmine at nm concentrations was likely due to the low rate of diffusion of the compound in the slice. To confirm this point, we tested the effect of an AChE inhibitor with a lower affinity, galantamine, for which the Ki has been evaluated as 227 nm (Santillo and Liu, 2015). Galantamine had no effect at a concentration of 100 nm. At 1 μm, it mimicked the effects of neostigmine: the mean value of the time constant of the slow decay τ21p increased by a factor of 2.6 ± 1.6 (n = 5, t(4) = −2.6134, p = 0.030), whereas a21p was reduced by a factor of 0.62 ± 0.33 (n = 5, t(4) = −2.517, p = 0.033). However, the effect developed in 10–15 min after the drug reached the slice, a rate comparable with that observed with NS9283 and much faster than that observed with neostigmine. After washing galantamine, the effect on τ21p was fully reversible, but the depression of a21p was not.

Overall, the results indicate that AChE inhibition does not increase a2, and thus suggest that the increase of a2 induced by NS9283 at concentrations between 1 and 10 μm cannot be attributed to the inhibition of AChE. They further suggest that the prolongation of the decay of the EPSC by blockade of AChE requires that more than half of the enzyme activity be inhibited, in which case concentrations of NS9283 a few times higher than its Ki for AChE would be needed to mimic the effects of neostigmine and galantamine, namely, a prolongation of the decay not associated with an increased amplitude of a2. This hypothesis was tested by analyzing the effects of NS9283 at 50 μm.

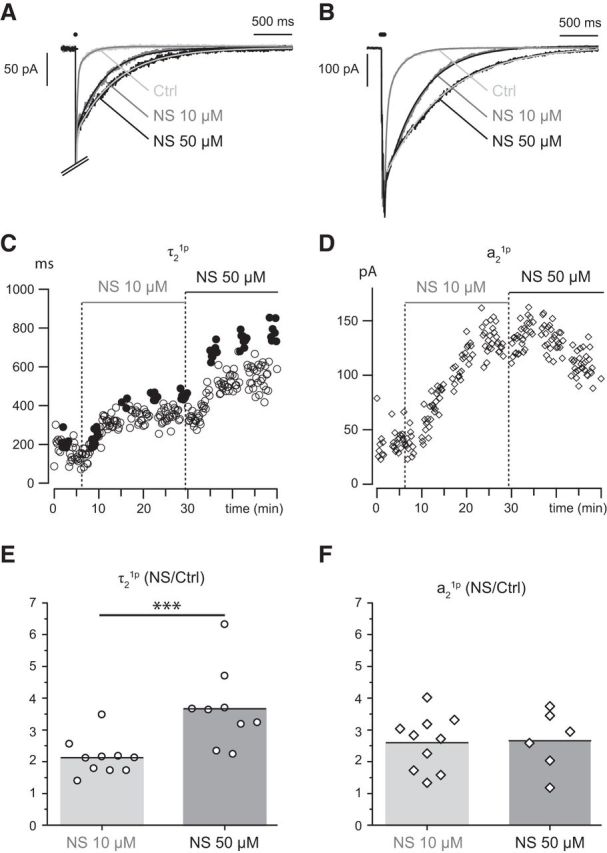

NS9283 50 μm acts on both the nAChRs and the AChE

When NS9283 was applied at 50 μm, it produced effects that resembled those of NS9293 10 μm. The comparison of the effects of the two concentrations showed that, although switching from 10 to 50 μm further increased τ21p by a factor 2.1 ± 0.6 (NS9283 10 μm, n = 10, t(9) = −6.5197, p = 0.00005 vs control) and by a factor of 3.67 ± 1.24 for NS9283 50 μm (n = 9, t(8) = −7.7494, p = 0.00003 vs control; t(11.007) = 3.3840, p = 0.0030, Welch test to compare the two concentrations), a21p was evenly increased by the two concentrations: by a factor 2.60 ± 0.86 for NS9283 10 μm (n = 10, t(9) = −3.9035, p = 0.0018 vs control) and by a factor of 2.66 ± 0.94 for NS9283 50 μm (n = 6; t(9) = −34.6549, p = 0.0028 vs control; t(9.89) = 0.1203, p = 0.45, Welch test to compare the two concentrations). This is illustrated in Figure 5A–C in an experiment where the two concentrations of NS9283 were applied in succession and in Figure 5E–F by the bar graphs from multiple experiments. The fact that increasing the NS9283 concentration only affects τ21p mirrors the effects of neostigmine and is in agreement with an anti-AChE effect. More generally, the data support the conclusion that up to 10 μm the effects of NS9283 are mostly due to its binding to the nAChRs and saturate at 10 μm, whereas for this concentration the anti-AChE effect is at its threshold and only becomes important at higher concentrations.

Figure 5.

NS9283 mimics the effects of neostigmine but only at high concentrations. NS9283 at 10 μm prolongs the decay (τ2, C) and increases the amplitude (a2, D) of the EPSC. Increasing the concentration to 50 μm induces a further slowing of the decay τ2 but not a further increase of the amplitude of the slow component. A, B, 1p-EPSC (A) and 5p-EPSC (B) in control, with 10 μm NS9283 and 50 μm NS9283. C, D, Time course of the changes of τ21p (C, open circles), τ25p (C, filled circles), and a21p (D, open diamonds) after addition of NS9283 at 10 μm and at 50 μm. E, F, Bar graphs comparing the changes of τ21p and a21p induced by NS9283 10 and 50 μm. The values plotted are the ratio of the values measured under NS9283 and those measured in control conditions. ***p < 0.001.

Our previous experiments on AChE inhibition by neostigmine at 0.1 and 1 μm (Lamotte d'Incamps et al., 2012) showed that the prolongation of the EPSCs was associated with the development of a steady inward current (a few 10s of pA at −60 mV for neostigmine 1 μm) and an increased variance of the holding current, which allowed evaluation of an elementary current (−1 pA at −60 mV) close to that induced by ACh applied exogenously. Similar observations were made by Katz and Miledi (1977) at the neuromuscular junction when AChE was blocked, and were explained by the buildup of “ambient” ACh leaking from the nerve terminal. In contrast, NS9283 at 10 μm was reported not to induce any inward current, whether in expression systems in which no AChE is present (Grupe et al., 2013) or in slices (Timmermann et al., 2012). This suggested that the presence of an inward current could be a test of the inhibition of AChE.

The effects of NS9283 on the holding current and its variance were analyzed at concentrations from 1 to 50 μm. Up to 3 μm, we could not detect any increase of either the holding current or its variance. At 10 μm, there was a small increase in the variance of the holding current in 13 of 23 experiments with a mean value of 7.2 ± 5.0 pA2 (t(22) = 3.7189, p = 0.0012, one-sample t test), but the associated inward current was too small to be evaluated on a background showing some increased leak current. In contrast, when NS9283 was applied at 50 μm, there was an inward current in all experiments but 1 (out of 8) with a mean value of 22.3 ± 13.9 pA (t(7) = 3.6543, p = 0.0081, one-sample t test) and an increased variance of 28.3 ± 18.5 pA2 (t(7) = 3.5336, p = 0.0096, one-sample t test).

In a parallel analysis with neostigmine, one could detect neither an inward current nor a change in variance of the holding current at neostigmine 30 nm. At 50 nm, we observed small changes of both parameters, which developed in 10s of minutes, like the changes in the EPSCs (Fig. 4). The changes in holding current were obscured by small changes of the leak current over these periods, but in 6 of 8 cells, the changes of variance were more robust and their average value was 10.7 ± 5.5 pA2 (t(7) = 3.3346, p = 0.013). These observations suggest that neostigmine or NS9283 only induce a leak of ACh when their concentration is ∼3–5 times the Ki (i.e., when the AChE inhibition is nearly complete).

The inhibition of AChE by NS9283 does prolong the EPSCs, but this effect is not significant for concentrations of NS9283 <10 μm, at which NS9283 saturates its binding site on A3B2 nAChRs.

The effects of NS9283 and neostigmine in β2−/− mice

There is evidence that the nAChRs of RCs in WT mice contain not only α4 and β2 subunits but also α2 and β4 subunits (Ishii et al., 2005; Lamotte d'Incamps and Ascher, 2013; Perry et al., 2015). The effects of NS9283 observed in A3B2 recombinant α4β2 nAChRs have been looked for in A3B2 assemblies of α2β2, α2β4, and α4β4 nAChRs (Lee et al., 2011; Timmermann et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015), and there is agreement on the fact that the potentiation is present in α2β2 nAChRs. However, in the case of β4-containing receptors (hereafter noted β4* nAChRs, resp. β2* for those containing the β2 subunit), Timmermann et al. (2012) reported positive effects of NS9283 on both α2β4 and α4β4 nAChRs, whereas Wang et al. (2015) saw no effect on α2β4 nAChRs, and Lee et al. (2011) saw no effect on α4β4 nAChRs. To try to evaluate the contribution of β4 subunits in the case of the RC, we analyzed β2−/− knock-out mice (see Materials and Methods).

In β2−/− mice, the EPSCs were very similar to the WT mice EPSCs (Lamotte d'Incamps and Ascher, 2013) and similarly affected by NS9283 at 10 μm, although less potently. The amplitude a21p of the slow component of the EPSC increased by a factor of 1.56 ± 0.45 (n = 9, t(8) = 3.723, p = 0.0029), whereas the value for the WT was 2.60 ± 0.86 (n = 10; p = 0.0018 vs control; t(13.91) = −3.3633, p = 0.0024, Welch test to compare the two strains); the value of τ21p increased by a factor of 1.13 ± 0.38 (n = 9, t(8) = 1.0076, not significant, p = 0.17) versus a value of 2.1 ± 0.6 in WT (n = 10, p = 0.00005 vs control, t(15.68) = −4.4748, p = 0.00020, Welch test to compare the two strains). We observed similar discrepancies between β2−/− and WT mice for a25p and τ25p.

In β2−/− mice, nicotine at 1 μm induced a current with an amplitude comparable with that of the current induced in WT mice (β2−/− 175 ± 119 pA; n = 6; WT: 215 ± 93 pA; n = 5; t(8.98) = 0.62, p = 0.55, Welch test). The potentiation by NS9283 10 μm was 1.4 ± 0.8-fold (n = 4, t(3) = −3.4053, p = 0.042, paired t test). Finally, saz-A at 50 nm, which induced a large current in WT mice (558 ± 358 pA, n = 6, t(5) = 3.8115, p = 0.012), did not induce any inward current in β2−/− mice, and NS9283 had no measurable effect when added on saz-A (n = 3). saz-A has been shown to activate some β4* receptors, but with an EC50 in the 100 nm range (Campling et al., 2013; Jensen et al., 2014). The results thus suggest that, at concentrations of <50 nm, the effects of saz-A in WT mice involve β2* nAChRs, some of which could associate β2 and β4 subunits.

Zn prolongs sEPSCs

García-Colunga et al. (2001) reported that, on α2β4 nAChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes, Zn potentiated the ACh induced current without inducing a current by itself. This observation was later extended to α4β2, α4β4, α3β4, and α2β2 nAChRs by Hsiao et al. (2001), and Hsiao et al. (2008) showed that, at the single-channel level, the potentiation resulted from an increased burst duration, and predicted that Zn should prolong the decay of synaptic currents mediated by the corresponding receptors. Moroni et al. (2008) and Mazzaferro et al. (2011) then found that, in α4β2 nAChRs, the Zn potentiation is specific of (α4)3(β2)2 receptors and due to the binding of Zn at the α4-α4 interface. The maximum potentiation was obtained with a Zn concentration of ∼100 μm. In contrast, at a concentration of 10 μm, Zn does not potentiate (α4)3(β2)2 receptors but has a selective antagonist effect on (α4)2(β2)3 receptors (Moroni et al., 2008).

When Zn was applied at 10 μm on the MN-RC synapse (5 experiments), it did not produce a significant change in either the amplitude or the decay of either the 1p eEPSCs (amplitude Ctrl 189 ± 158 pA, Zn 165 ± 143 pA, n = 5, t(4) = 2.1482, p = 0.098; τw Ctrl 24.1 ± 10.4 ms, Zn 26.3 ± 10.7 ms, n = 5, t(4) = −0.4619, p = 0.67) or the sEPSCs (amplitude Ctrl 14.1 ± 0.2 pA, n = 2 experiments, Zn 16.3 ± 4.2 pA, n = 3, Mann–Whitney U = 2, p = 0.8; τw Ctrl 11.8 ± 2.2 ms, n = 2, Zn 15.5 ± 3.9 ms, n = 3, Mann–Whitney U = 1, p = 0.4) (Fig. 6A,B). In contrast, when Zn 100 μm was applied, the eEPSC showed a rapid and strong reduction, sometimes disappearing completely (Ctrl 301 ± 158 pA, Zn 65.4 ± 54.3 pA, n = 7, t(6) = 4.9272, p = 0.0013). This effect was likely presynaptic as Zn in the range of 100 μm is known to block most Ca channels (Magistretti et al., 2003). On the other hand, the amplitude of sEPSCs was not modified (Ctrl 15.4 ± 5.4 pA, Zn 15.1 ± 3.1 pA, n = 4, t(3) = 0.162, p = 0.88), while their decay was slowed: τw increased from 12.3 ± 1.7 ms to 21.1 ± 3.9 ms (n = 4, t(3) = −6.1056, p = 0.088), and this was mostly due to a prolongation of the slow time constant, which increased from 27.7 ± 12.6 ms to 45.4 ± 10 ms (n = 3, t(2) = −8.3969, p = 0.014; Fig. 6A). These data are in the direction predicted by Hsiao et al. (2008) from their analysis of single channels activated by ACh application. They support the notion that sEPSCs are mostly and possibly exclusively mediated by A3B2 receptors.

In the reduced eEPSCs, the time constants of decay of the two components were not significantly changed. The amplitudes of the fast component and of the slow component were both reduced, but this reduction was more marked for the fast component (Fig. 6C1; a2/a1 went from 0.14 ± 0.06 in Ctrl up to 0.61 ± 0.41 in 100 μm Zn, n = 7, t(6) = −3.1214, p = 0.010). To examine whether this difference could be related to the reduction of the ACh release, we analyzed the effects on the eEPSCs of a reduction of external Ca from 2 to 1 mm. As in the case of Zn, there was little change in the decay time constants, but the reduction of the slow component was of the same order, or larger, than that of the fast component (Fig. 6C2; a2/a1 went from 0.27 ± 0.12 in Ctrl down to 0.15 ± 0.03 in 1 μm Ca, n = 7, t(6) = 2.2738, p = 0.031). This suggests that, in the case of Zn application, the reduction of the release masks an actual increase of the relative size of the slow component, similar to that observed with NS9283. The reduction of the release may also shorten the decay of the EPSC, which is partly controlled by spillover (Lamotte d'Incamps et al., 2012) and mask the increase of the dissociation rate.

The effects of Zn reinforce the conclusion, first derived from the effects of NS9283, that A3B2 receptors are present on RCs. However, the prolongation induced by Zn appears smaller than that induced by NS9283, and does not affect in the same proportions as NS9283 the amplitude and the decay of the slow component of the synaptic current. This may be linked to the fact that, although NS9283 and Zn both bind to the α-α interface, they do not seem bind to the same amino acids: Moroni et al. (2008) concluded that α4H195 and α4E224 contribute to the Zn2+ binding site, whereas for the NS9283 binding site Wang et al. (2015) gave a crucial role to α4T126 Olsen et al. (2013) to α4H116 and Wang et al. (2017) to α4Q124.

Discussion

A3B2 receptors mediate both components of the EPSC

The speed of decay of synaptic currents involves many factors, among which the speed of dissociation of the transmitter from the receptors, desensitization, and the evolution of the transmitter concentration in and around the cleft (Scimemi and Beato, 2009). In our early study of the decay of MN-RC EPSCs, we proposed that the two components of the decay could reflect the presence of two heteromeric nAChRs with different affinities for ACh: low affinity (LS) receptors from which ACh would dissociate rapidly, and high affinity (HS) receptors from which ACh would dissociate slowly (Lamotte d'Incamps et al., 2012). At that time, LS and HS receptors were, respectively, equated with A3B2 and A2B3 receptors, and we thus assumed that the fast component would be mediated by A3B2 nAChRs and the slow one by A2B3 nAChRs. The discovery that the CRR of A3B2 nAChRs has both an HS and an LS limb (Harpsøe et al., 2011; Wang and Lindstrom, 2017) opened the possibility that this single class of stoichiometric variants could be sufficient to explain the biphasic EPSC: the fast component would result from the activation of A3B2 nAChRs by a high concentration of ACh binding to both α-β interfaces and to the α-α interface (LS mode), whereas during the slow component, due to the lower ACh concentration, ACh only binds to α-β interfaces (HS mode).

This hypothesis is supported by the observation that NS9283 and Zn potentiate the slow components of the EPSCs, in agreement with the report by Grupe et al. (2013) that NS9283 slowed the decay of the responses to brief pulses of ACh. A similar interpretation can explain the slowing of the sEPSCs by Zn (100 μm). The potentiation of the slow component of the EPSCs also agrees with the single-channel observations, which showed for nonsaturating concentrations of ACh a marked increase in the frequency of channel openings both on (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs exposed to NS9283 (Mazzaferro et al., 2017) and on α4β4 nAChRs exposed to Zn (Hsiao et al., 2008). The kinetic model of the effects of NS9283 proposed by Indurthi et al. (2016), which proposes that NS9283 increases the probability of opening of the channels by acting on “preactivated states” rather than the closed-open transition or the single-channel conductance, is in good agreement with these observations.

The observation that NS9283 does not increase the amplitude of the early component of the EPSCs (Fig. 1) is in agreement with the observation of Grupe et al. (2013) showing that NS9283 left shifts the CRR of ACh but is without effect at saturating concentrations of ACh. Both observations are at first sight difficult to reconcile with the report by Grupe et al. (2013) that NS9283 increased the peak of the response to brief pulses of 1 mm ACh. The contradiction can be resolved if the ACh concentration is saturating at the peak of the early EPSC, but not in the case of a pulse of ACh applied on HEK cells with a theta glass capillary. The absence of a prolongation of the early EPSC by NS9283 (Fig. 1) is puzzling, as one would expect that, when the concentration of ACh decreases after the peak, NS9283 would potentiate a tail current. However, the decay of the ACh concentration in the synaptic cleft may actually be extremely rapid due to the presence of AChE (<1 ms, as at the neuromuscular junction) (Magleby and Stevens, 1972), and the early current may entirely originate from the receptors in which the α-α interfaces are fully occupied by a saturating concentration of ACh (in control conditions) or by ACh and NS9283 (when NS9283 is present).

Two populations of A3B2 nAChRs?

Within the scheme in which the two components of the EPSCs correspond to two modes of activation of the A3B2 receptors, we had previously considered the possibility (Lamotte d'Incamps and Ascher, 2014) that the dissociation constants of ACh in the LS and HS modes could be directly related to the two time constants of the decay. This appears unlikely, at least for the HS mode, as the hypothesis predicts long channel openings (or long bursts of openings) during the slow component of the EPSCs. This prediction is not supported by the single channel observations of Carignano et al. (2016) and Mazzaferro et al. (2017) who only observed short openings of A3B2 nAChRs, whether these were exposed to low or high ACh concentrations. In addition, the fact that the time constants of the slow components of the synaptic currents are noticeably smaller for sEPSCs than for eEPSCs, and smaller for 1p-eEPSCs than for 5p-eEPSCs, suggests that these time constants do not reflect directly the speed of dissociation of ACh and are influenced by other parameters, such as the speed of decay of the ACh concentration in and out of the synaptic cleft (Lamotte d'Incamps et al., 2012) and possibly desensitization. We therefore favor a more complex interpretation of the biphasic EPSC decay, in which A3B2 nAChRs mediate both components but are present both in the subsynaptic region (where they are exposed to a brief pulse of ACh at high concentration) and in perisynaptic and extrasynaptic regions where they are activated by low concentrations of ACh having escaped hydrolysis by the synaptic cleft AChE and decaying slowly in the absence of local AChE (Lamotte d'Incamps et al., 2012; Lamotte d'Incamps and Ascher, 2014).

Evidence for the presence in RCs of nAChRs other than (α4)2(β2)3 nAChRs

The effects of NS9283 and of Zn 100 μm demonstrate the presence of A3B2 nAChRs at the MN-RC synapse. They do not demonstrate that all the potentiated receptors are β2* nAChRs, and they do not exclude that some of the slow component of the control EPSC be due to A2B3 nAChRs.

The presence of β4* A3B2 nAChRs is made likely by the fact that, in β2−/− mice, EPSCs and nicotine-induced currents are potentiated by NS9283. The relatively large size of the currents induced by low concentrations of cytisine in WT mice could also indicate a contribution of β4* nAChRs because, for some of these receptors, cytisine is a full agonist whereas it is only a very weak partial agonist on β2* nAChRs (Luetje and Patrick, 1991; Papke and Heinemann, 1994; Harpsøe et al., 2013).

There is evidence for the presence of both A2B3 and A3B2 nAChRs in the CNS (Marks et al., 1999, 2007; Shafaee et al., 1999; Gotti et al., 2008; DeDominicis et al., 2017), in variable proportions (Kuryatov et al., 2005). However, the similarity between the potentiations induced by NS9283 on the responses to the four agonists tested, as well as the fact that Zn at 10 μm, which has been shown to inhibit A2B3 nAChRs without affecting A3B2 nAChRs (Moroni et al., 2008), had no detectable effect on either the eEPSCs or the sEPSCs, both suggest that, if present, A2B3 nAChRs are not abundant and contribute little to the synaptic currents.

Can one use NS9283 to identify A3B2 nAChRs?

NS9283 is a useful tool to identify A3B2 nAChRs in the CNS, as proposed by the discoverers of the compound. Nevertheless, the anti-AChE properties of NS9283 could complicate the interpretation of the physiological effects of NS9283. In behavioral experiments, NS9283 has been usually applied orally at doses from 0.1 mg/kg up to 3 mg/kg, which Timmermann et al. (2012) extrapolated to brain concentrations of 0.11–3.3 μm. However, some experiments used much higher concentrations (up to 30 mg/kg) (Rode et al., 2012) at which effects on AChE could become significant. Furthermore, the threshold for a functional effect of the blockade of AChE may not be the same for all central nicotinic synapses and may be lowered in pathological conditions. Mice with reduced AChE activity due to heterozygous AChE are more sensitive to AChE inhibitors (Mohr et al., 2013), which suggests that partial inhibition of AChE may have important effects in conditions in which the cholinergic transmission is chronically impaired, as in Alzheimer's disease (Wilkinson et al., 2004).

A3B2 nAChRs in the CNS may mediate both fast and slow EPSCs

The CNS EPSCs or EPSPs involving heteromeric nAChRs have time constants of decay varying from a few 10s of milliseconds (Nose et al., 1991; Bell et al., 2011; English et al., 2011; Leão et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2013; Unal et al., 2015) to hundreds of milliseconds (Hu et al., 1989; Nose et al., 1991; Bell et al., 2011; Ren et al., 2011; Arroyo et al., 2012; Bennett et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2013; Hay et al., 2016). The slow EPSCs were often assumed to be mediated by A2B3 nAChRs because A3B2 nAChRs were initially characterized as low affinity LS receptors. As already noted by Timmermann et al. (2012), the discovery that the CRR of A3B2 nAChRs has a HS foot opened the possibility that A3B2 nAChRs situated far from the ACh release site may be activated by low concentrations of ACh and mediate slow synaptic currents. This may be in particular the case for the slow cortical synaptic currents mediated by heteromeric nAChRs, which are often assumed to be activated by volume transmission (Descarries et al., 1997; Bennett et al., 2012), and which yet may be carried by (α4)3(β2)2 receptors (DeDominicis et al., 2017).

Footnotes

This work was supported by Université Paris Descartes, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Association française contre les myopathies AFM 16026 to B.L.d. We thank Dan Peters for a sample of NS9283 used in the initial experiments; Palmer Taylor for providing mouse AChE; Uwe Maskos for providing the β2−/−, α7−/−, and α7−/− β2−/− mice; and Marco Beato, Francis Crépel, Stéphane Dieudonné, Anne Feltz, Bruno Gasnier, Marc Gielen, Jochen Klein, and Alain Marty for suggestions and comments on an early draft of the paper.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Anderson DJ, Malysz J, Grønlien JH, El Kouhen R, Håkerud M, Wetterstrand C, Briggs CA, Gopalakrishnan M (2009) Stimulation of dopamine release by nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ligands in rat brain slices correlates with the profile of high, but not low, sensitivity α4β2 subunit combination. Biochem Pharmacol 78:844–851. 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo S, Bennett C, Aziz D, Brown SP, Hestrin S (2012) Prolonged disynaptic inhibition in the cortex mediated by slow, non-α7 nicotinic excitation of a specific subset of cortical interneurons. J Neurosci 32:3859–3864. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0115-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell KA, Shim H, Chen CK, McQuiston AR (2011) Nicotinic EPSPs in hippocampal CA1 interneurons are predominantly mediated by nicotinic receptors that contain α4 and β2 subunits. Neuropharmacology 61:1379–1388. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benallegue N, Mazzaferro S, Alcaino C, Bermudez I (2013) The additional ACh binding site at the α4(+)/α4(−) interface of the (α4β2)2α4 nicotinic ACh receptor contributes to desensitization. Br J Pharmacol 170:304–316. 10.1111/bph.12268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett C, Arroyo S, Berns D, Hestrin S (2012) Mechanisms generating dual-component nicotinic EPSCs in cortical interneurons. J Neurosci 32:17287–17296. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3565-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campling BG, Kuryatov A, Lindstrom J (2013) Acute activation, desensitization and smoldering activation of human acetylcholine receptors. PLoS One 8:e79653. 10.1371/journal.pone.0079653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone AL, Moroni M, Groot-Kormelink PJ, Bermudez I (2009) Pentameric concatenated (α4)2(β2)3 and (α4)3(β2)2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: subunit arrangement determines functional expression. Br J Pharmacol 156:970–981. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00104.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carignano C, Barila EP, Spitzmaul G (2016) Analysis of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α4β2 activation at the single-channel level. Biochim Biophys Acta 1858:1964–1973. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish-Bowden A. (2012) Fundamentals of enzyme kinetics, Ed 4 Weinheim, Germany: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Dani JA. (2015) Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor structure and function and response to nicotine. Int Rev Neurobiol 124:3–19. 10.1016/bs.irn.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeDominicis KE, Sahibzada N, Olson TT, Xiao Y, Wolfe BB, Kellar KJ, Yasuda RP (2017) The (α4)3(β2)2 stoichiometry of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor predominates in the rat motor cortex. Mol Pharmacol 92:327–337. 10.1124/mol.116.106880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descarries L, Gisiger V, Steriade M (1997) Diffuse transmission by acetylcholine in the CNS. Prog Neurobiol 53:603–625. 10.1016/S0301-0082(97)00050-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton JB, Peng JH, Schroeder KM, George AA, Fryer JD, Krishnan C, Buhlman L, Kuo YP, Steinlein O, Lukas RJ (2003) Characterization of human α4β2-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors stably and heterologously expressed in native nicotinic receptor-null SH-EP1 human epithelial cells. Mol Pharmacol 64:1283–1294. 10.1124/mol.64.6.1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton JB, Lucero LM, Stratton H, Chang Y, Cooper JF, Lindstrom JM, Lukas RJ, Whiteaker P (2014) The unique α4(+)/(−)α4 agonist binding site in (α4)3(β2)2 subtype nicotinic acetylcholine receptors permits differential agonist desensitization pharmacology versus the (α4)2(β2)3 subtype. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 348:46–58. 10.1124/jpet.113.208389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JC, Fatt P, Koketsu K (1954) Cholinergic and inhibitory synapses in a pathway from motor-axon collaterals to motoneurones. J Physiol 126:524–562. 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V Jr, Featherstone RM (1961) A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol 7:88–95. 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DF, Ibanez-Sandoval O, Stark E, Tecuapetla F, Buzsáki G, Deisseroth K, Tepper JM, Koos T (2011) GABAergic circuits mediate the reinforcement-related signals of striatal cholinergic interneurons. Nat Neurosci 15:123–130. 10.1038/nn.2984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Colunga J, González-Herrera M, Miledi R (2001) Modulation of alpha2beta4 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by zinc. Neuroreport 12:147–150. 10.1097/00001756-200101220-00037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Moretti M, Gaimarri A, Zanardi A, Clementi F, Zoli M (2007) Heterogeneity and complexity of native brain nicotinic receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 74:1102–1111. 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Moretti M, Meinerz NM, Clementi F, Gaimarri A, Collins AC, Marks MJ (2008) Partial deletion of the nicotinic cholinergic receptor α4 or β2 subunit genes changes the acetylcholine sensitivity of receptor-mediated 86Rb+ efflux in cortex and thalamus and alters relative expression of α4 and β2 subunits. Mol Pharmacol 73:1796–1807. 10.1124/mol.108.045203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grupe M, Jensen AA, Ahring PK, Christensen JK, Grunnet M (2013) Unravelling the mechanism of action of NS9283, a positive allosteric modulator of (α4)3(β2)2 nicotinic ACh receptors. Br J Pharmacol 168:2000–2010. 10.1111/bph.12095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpsøe K, Ahring PK, Christensen JK, Jensen ML, Peters D, Balle T (2011) Unraveling the high- and low-sensitivity agonist responses of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci 31:10759–10766. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1509-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpsøe K, Hald H, Timmermann DB, Jensen ML, Dyhring T, Nielsen EØ, Peters D, Balle T, Gajhede M, Kastrup JS, Ahring PK (2013) Molecular determinants of subtype-selective efficacies of cytisine and the novel compound NS3861 at heteromeric nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem 288:2559–2570. 10.1074/jbc.M112.436337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay YA, Lambolez B, Tricoire L (2016) Nicotinic transmission onto layer 6 cortical neurons relies on synaptic activation of non-α7 receptors. Cereb Cortex 26:2549–2562. 10.1093/cercor/bhv085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan LM, Slater Y, Guerra DL, Peng JH, Kuo YP, Lukas RJ, Cassels BK, Bermudez I (2001) Activity of cytisine and its brominated isosteres on recombinant human α7, α4β2 and α4β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurochem 78:1029–1043. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00481.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao B, Dweck D, Luetje CW (2001) Subunit-dependent modulation of neuronal nicotinic receptors by zinc. J Neurosci 21:1848–1856. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01848.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao B, Mihalak KB, Magleby KL, Luetje CW (2008) Zinc potentiates neuronal nicotinic receptors by increasing burst duration. J Neurophysiol 99:999–1007. 10.1152/jn.01040.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Steriade M, Deschênes M (1989) The effects of brainstem peribrachial stimulation on neurons of the lateral geniculate nucleus. Neuroscience 31:13–24. 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90027-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indurthi DC, Lewis TM, Ahring PK, Balle T, Chebib M, Absalom NL (2016) Ligand binding at the α4-α4 agonist-binding site of the α4β2 nAChR triggers receptor activation through a pre-activated conformational state. PLoS One 11:e0161154. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K, Wong JK, Sumikawa K (2005) Comparison of alpha2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit mRNA expression in the central nervous system of rats and mice. J Comp Neurol 493:241–260. 10.1002/cne.20762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AB, Hoestgaard-Jensen K, Jensen AA (2014) Pharmacological characterisation of α6β4* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors assembled from three chimeric α6/α3 subunits in tsA201 cells. Eur J Pharmacol 740:703–713. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R (1977) Transmitter leakage from motor nerve endings. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 196:59–72. 10.1098/rspb.1977.0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuryatov A, Luo J, Cooper J, Lindstrom J (2005) Nicotine acts as a pharmacological chaperone to up-regulate human alpha4beta2 acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 68:1839–1851. 10.1124/mol.105.012419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamotte d'Incamps B, Ascher P (2008) Four excitatory postsynaptic ionotropic receptors coactivated at the motoneuron-Renshaw cell synapse. J Neurosci 28:14121–14131. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3311-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamotte d'Incamps B, Ascher P (2013) Subunit composition and kinetics of the Renshaw cell heteromeric nicotinic receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 86:1114–1121. 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamotte d'Incamps B, Ascher P (2014) High affinity and low affinity heteromeric nicotinic acetylcholine receptors at central synapses. J Physiol 592:4131–4136. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.273128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamotte d'Incamps B, Krejci E, Ascher P (2012) Mechanisms shaping the slow nicotinic synaptic current at the motoneuron-Renshaw cell synapse. J Neurosci 32:8413–8423. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0181-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leão RN, Mikulovic S, Leão KE, Munguba H, Gezelius H, Enjin A, Patra K, Eriksson A, Loew LM, Tort AB, Kullander K (2012) OLM interneurons differentially modulate CA3 and entorhinal inputs to hippocampal CA1 neurons. Nat Neurosci 15:1524–1530. 10.1038/nn.3235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Zhu C, Malysz J, Campbell T, Shaughnessy T, Honore P, Polakowski J, Gopalakrishnan M (2011) α4β2 neuronal nicotinic receptor positive allosteric modulation: an approach for improving the therapeutic index of α4β2 nAChR agonists in pain. Biochem Pharmacol 82:959–966. 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester RA. (2004) Activation and desensitization of heteromeric neuronal nicotinic receptors: implications for non-synaptic transmission. Bioorganic Med Chem Lett 14:1897–1900. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.02.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luetje CW, Patrick J (1991) Both alpha- and beta-subunits contribute to the agonist sensitivity of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci 11:837–845. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00837.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti J, Castelli L, Taglietti V, Tanzi F (2003) Dual effect of Zn2+ on multiple types of voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents in rat palaeocortical neurons. Neuroscience 117:249–264. 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00865-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magleby KL, Stevens CF (1972) A quantitative description of end-plate currents. J Physiol 223:173–197. 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MJ, Whiteaker P, Calcaterra J, Stitzel JA, Bullock AE, Grady SR, Picciotto MR, Changeux JP, Collins AC (1999) Two pharmacologically distinct components of nicotinic receptor-mediated rubidium efflux in mouse brain require the beta2 subunit. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 289:1090–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MJ, Meinerz NM, Drago J, Collins AC (2007) Gene targeting demonstrates that α4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits contribute to expression of diverse [3H]epibatidine binding sites and components of biphasic 86Rb+ efflux with high and low sensitivity to stimulation by acetylcholine. Neuropharmacology 53:390–405. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marotta CB, Rreza I, Lester HA, Dougherty DA (2014) Selective ligand behaviors provide new insights into agonist activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. ACS Chem Biol 9:1153–1159. 10.1021/cb400937d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaferro S, Benallegue N, Carbone A, Gasparri F, Vijayan R, Biggin PC, Moroni M, Bermudez I (2011) Additional acetylcholine (ACh) binding site at α4/α4 interface of (α4β2)2α4 nicotinic receptor influences agonist sensitivity. J Biol Chem 286:31043–31054. 10.1074/jbc.M111.262014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaferro S, Gasparri F, New K, Alcaino C, Faundez M, Iturriaga Vasquez P, Vijayan R, Biggin PC, Bermudez I (2014) Non-equivalent ligand selectivity of agonist sites in (α4β2)2α4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: a key determinant of agonist efficacy. J Biol Chem 289:21795–21806. 10.1074/jbc.M114.555136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaferro S, Bermudez I, Sine SM (2017) α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: relationships between subunit stoichiometry and function at the single channel level. J Biol Chem 292:2729–2740. 10.1074/jbc.M116.764183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Heath MJ, Gelber S, Devay P, Role LW (1995) Nicotine enhancement of fast excitatory synaptic transmission in CNS by presynaptic receptors. Science 269:1692–1696. 10.1126/science.7569895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr F, Zimmermann M, Klein J (2013) Mice heterozygous for AChE are more sensitive to AChE inhibitors but do not respond to BuChE inhibition. Neuropharmacology 67:37–45. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroni M, Zwart R, Sher E, Cassels BK, Bermudez I (2006) alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptors with high and low acetylcholine sensitivity: pharmacology, stoichiometry, and sensitivity to long-term exposure to nicotine. Mol Pharmacol 70:755–768. 10.1124/mol.106.023044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroni M, Vijayan R, Carbone A, Zwart R, Biggin PC, Bermudez I (2008) Non-agonist-binding subunit interfaces confer distinct functional signatures to the alternate stoichiometries of the α4β2 nicotinic receptor: an α4-α4 interface is required for Zn2+ potentiation. J Neurosci 28:6884–6894. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1228-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ME, Kuryatov A, Choi CH, Zhou Y, Lindstrom J (2003) Alternate stoichiometries of alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 63:332–341. 10.1124/mol.63.2.332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nose I, Higashi H, Inokuchi H, Nishi S (1991) Synaptic responses of guinea pig and rat central amygdala neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol 65:1227–1241. 10.1152/jn.1991.65.5.1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JA, Kastrup JS, Peters D, Gajhede M, Balle T, Ahring PK (2013) Two distinct allosteric binding sites at α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors revealed by NS206 and NS9283 give unique insights to binding activity-associated linkage at cys-loop receptors. J Biol Chem 288:35997–36006. 10.1074/jbc.M113.498618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr-Urtreger A, Göldner FM, Saeki M, Lorenzo I, Goldberg L, De Biasi M, Dani JA, Patrick JW, Beaudet AL (1997) Mice deficient in the alpha7 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor lack alpha-bungarotoxin binding sites and hippocampal fast nicotinic currents. J Neurosci 17:9165–9171. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09165.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]