Abstract

Scientists have hypothesized that the availability of phosphocreatine (PCr) and its ratio to inorganic phosphate (Pi) in cerebral tissue form a substrate of wakefulness. It follows then, according to this hypothesis, that the exhaustion of PCr and the decline in the ratio of PCr to Pi form a substrate of fatigue. We used 31P-magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P-MRS) to investigate quantitative levels of PCr, the γ-signal of ATP, and Pi in 30 healthy humans (18 female) in the morning, in the afternoon, and while napping (n = 15) versus awake controls (n = 10). Levels of PCr (2.40 mM at 9 A.M.) decreased by 7.0 ± 0.8% (p = 7.1 × 10−6, t = −5.5) in the left thalamus between 9 A.M. and 5 P.M. Inversely, Pi (0.74 mM at 9 A.M.) increased by 17.1 ± 5% (p = 0.005, t = 3.1) and pH levels dropped by 0.14 ± 0.07 (p = 0.002; t = 3.6). Following a 20 min nap after 5 P.M., local PCr, Pi, and pH were restored to morning levels. We did not find respective significant changes in the contralateral thalamus or in other investigated brain regions. Left hemispheric PCr was signficantly lower than right hemispheric PCr only at 5 P.M. in the thalamus and at all conditions in the temporal region. Thus, cerebral daytime-related and sleep-related molecular changes are accessible in vivo. Prominent changes were identified in the thalamus. This region is heavily relied on for a series of energy-consuming tasks, such as the relay of sensory information to the cortex. Furthermore, our data confirm that lateralization of brain function is regionally dynamic and includes PCr.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT The metabolites phosphocreatine (PCr) and inorganic phosphate (Pi) are assumed to inversely reflect the cellular energy load. This study detected a diurnal decrease of intracellular PCr and a nap-associated reincrease in the left thalamus. Pi behaved inversely. This outcome corroborates the role of the thalamus as a region of high energy consumption in agreement with its function as a gateway that relays and modulates information flow. Conversely to the dynamic lateralization of thalamic PCr, a constantly significant lateralization was observed in other regions. Increasing fatigue over the course of the day may also be a matter of cerebral energy supply. Comparatively fast restoration of that supply may be part of the biological basis for the recreational value of “power napping.”

Keywords: 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy, inorganic phosphate, pH, phosphocreatine, thalamus

Introduction

Many recent studies have focused on the diurnal alterations of cerebral energy supply. Modalities such as PET, MRI, EEG, and behavioral tests have provided a wide spectrum of parameters to characterize different states of wakefulness and sleep propensity. Diurnal exhaustion of cerebral energy and activational reserves has been proposed as a factor contributing to fatigue in the evening (Porkka-Heiskanen and Kalinchuk, 2011). Dijk and coworkers (1987) let volunteers nap for 30 min after being awake for 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, or 20 h, respectively. The reseachers recorded 90% of night sleep maximum slow-wave activity at 16 h and later. Using fMRI (Marek et al., 2010), subjects performing a Stroop task were investigated after being awake for 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22 h. The researchers found maximal network activation at 6 h and minimal at 18 h. Glucose metabolism (CMRGlc) was studied using [18F]FDG-PET, perfusion was studied using fMRI or [15O]H2O-PET, and oxygen consumption (CMROx) was studied using [15O]O2-PET. Two studies investigating subjects in the morning and in the afternoon revealed a global decrease of absolute CMRGlc by 6 and 4% (Buysse et al., 2004; Shannon et al., 2013). While the decrease was pronounced in cortical areas, both detected constant CMRGlc in the thalamus. CMROx decreased globally by 5% and a constant oxygen-glucose index pointed to minimal admixture of anaerobic glycolysis (Shannon et al., 2013).

Plante et al. (2014) reported 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) in 8.8 ml voxels of eight subjects showing a significant increase of PCr but not of ATP after recovery sleep following sleep deprivation in gray matter but not in white matter. Baseline condition versus sleep deprivation did not differ significantly. The metabolic Pi/PCr ratio was constant through all conditions. The same group (Trksak et al., 2013) previously reported <3% change in global PCr and ATP during baseline, sleep deprivation, and recovery sleep in 14 controls, including the eight subjects above. Changes of other metabolites after sleep deprivation were detected by 1H-MRS (Urrila et al., 2006).

Ex vivo measurements of ATP and PCr in brain extracts from rats before and after 3 h of sleep deprivation showed a decrease of PCr by 57% and of ATP by 40% in the frontal cortex (Dworak et al., 2010, 2017).

As neuronal firing is the major energy consumer in the brain, states with prevailing slow EEG activity may be associated with lower energy demand. In some neurons, firing rates were even reduced to silence during delta sleep (Nir et al., 2011). This is consistent with the results of [18F]FDG-PET studies before and after 32 h total sleep deprivation. Considerable reductions of absolute CMRGlc after sleep deprivation were observed in thalamus (left: −23%; right: −18%), basal ganglia, and cerebellum; a moderate decline was detected in lateral frontal (−9%) and temporal cortices (−13%; Wu et al., 1991, 2006). The thalamus, a pivotal hub of somatic and cortical afferences and efferences, is particularly active during wakefulness. During sleep it is known as the generator of EEG spindles (McCormick, 2002; Lüthi, 2014). Therefore, it was included as a candidate region.

In research concerning diurnal and nocturnal changes of brain lateralization, Casagrande and Bertini (2008), using a simple finger-tapping motor paradigm, observed a switch of left to right hemispheric dominance. Falling asleep and waking up were differently delayed in different brain regions in long-term EEG studies and occurred earlier in the left hemisphere (Rial et al., 2013). Some authors addressed the correlation of lateralization of different tasks and brain regions by fMRI. Indeed, all were found correlated, except parietal activity related to spatial attention (Badzakova-Trajkov et al., 2010).

Given that so little data are available on the fate of high-energy phosphates in the human brain during daytime, we designed a study using 31P MRS. To detect changes of PCr, Pi, and γ-ATP signals, we used a longitudinal study design that included measurements in the morning, in the afternoon, and during a short nap.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

The study included 32 healthy subjects (19 females, 13 males; mean age, 36 ± 3 years; range, 20–61 years) recruited from scientific staff and by local advertisements. Medical histories were free of sleep, psychiatric, neurological, alcohol, or drug disorders. One male was excluded due to movement artifacts and one female due to left-handedness. All 30 remaining subjects were right-handed nonsmokers who took no medications. Handedness was assessed using a 19-item adaption of the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971) and revealed scores at 16.2 ± 1.1 of a maximum of 19. Subjects slept ≥7 h on the night before the study. Most of the participants were members of the scientific staff. Between the morning and the afternoon sessions, all subjects performed their usual work in a scientific research center, which was mainly office work using computers and thus highly demanding on left-hemispheric capacities. During this time, all avoided caffeine. The study was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of the medical faculty of the University of Düsseldorf.

Measurement procedure.

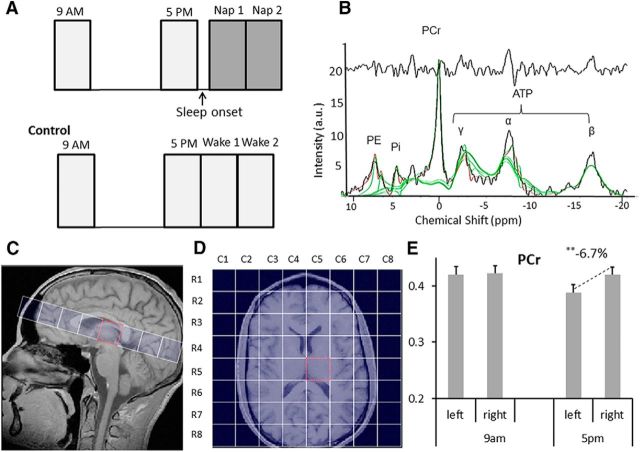

A 3.0 T Magnetom scanner (TrioTim, Siemens) was equipped with a double-tuned 31P-1H head coil from Rapid Biomedical. MRS protocols of 20 min were identical throughout all subjects and conditions. Subjects were measured in two sessions, one starting at 9:04 A.M. (±26 min) and one at 4:52 P.M. (±19 min; Fig. 1A). The morning session included one MRS scan of 20 min awake (9 A.M., n = 30, 18 female). The afternoon session included one MRS scan of 20 min awake (5 P.M., n = 30, 18 female) and two subsequent MRS scans of 20 min, either while napping (Nap1, n = 15, 8 female; Nap2, n = 13, 7 female) or awake (Wake1, Wake2, n = 10 controls, 7 female). During the scans in the wake-state, subjects were requested to stay awake and keep their eyes open. All subjects were equipped with a pulse oximeter, permanently monitored, and occasionally reminded to keep their eyes open. After completion of the afternoon wake scan, members of the nap subcohort was allowed to close their eyes and fall asleep. Napping state was defined by rest of voluntary movements, clear slowing of breathing, and a drop of the heart rate by ≥5/min and reached after an average delay of 7 ± 3 min after the end of the wake scan. The average individual drop in heart rate to sleep stages 1 and 2 was reported at 4.1/min and 6.64/min(Burgess et al., 1999) and at 2.5/min and 5.8/min (Zemaityte et al., 1986; Burgess et al., 1999), respectively. None of the subjects spontaneously awakened during or between the Nap1 and Nap2 scans and all required vigorous wake-up calls after the end of the procedure.

Figure 1.

A, Study design. Top, Subjects were measured in two sessions, one in the morning at 9 A.M. and one in the afternoon at 5 P.M. of the same day. After the afternoon 5 P.M. scan at wake state, 15 subjects remained positioned in the scanner and were further measured while napping. Each measurement lasted 20 min. Bottom, 10 controls underwent the same protocol but stayed awake during the second and third scan of the 5 P.M. session. B, 31P spectrum of the left thalamic voxel (R5, C5) after postprocessing with Tarquin. The upper black line represents residuals after fitting. The green and red lines are the fitted and modeled linear combination of monomolecular basic spectra. C, Sagittal view with the grid placed parallel to and 2 mm under the anterior commissure–posterior commissure plane. D, Axial 2D flash image in radiological orientation (left hemisphere at the right image side) overlaid with the CSI grid of 8 × 8 voxels. E, Comparison of PCr levels in the left (R5C5) and right (R5C4) thalamus voxel. In the morning the intraindividual left–right percentage difference averaged −1.9%, rising in the afternoon to highly significant −6.7%. Error bars denote SEM.

The thalamus region was positioned in the isocenter of the scanner and in the center of the predefined 8 × 8 voxel chemical shift imaging (CSI) grid (Fig. 1C,D). Furthermore, the grid was centered midsagittally in the x-axis and tilted parallel to the anterior commissure–posterior commissure line in the sagittal (yz) plane and shifted with the lower edge crossing the colliculus inferior. An AAH Scout was applied. This coregistration tool enable to perfectly reposition the acquisition grid as in a precedent measurement. Anatomical reference images in the sagittal, coronal, and transversal planes were acquired using T1-weighted two-dimensional (2D) flash sequences before the 2D CSI 31P-MRS sequences. Manual shimming ensured FWHM ≤ 25 Hz before data acquisition. Finally, a three-dimensional (3D) MPRAGE sequence used an eight-channel 1H-coil (3 T head matrix). All parameters were kept constant throughout all in vivo and phantom measurements.

To test reproducibility, two subjects underwent the entire protocol twice on 2 different days. To exclude any left–right asymmetry of the instrumentation, one subject was scanned in prone and in supine positions at either condition.

Sequences.

The T1-weighted 2D flash sequence used the following parameters: field of view (FOV), 20.2 × 20.2 cm; voxel size, 0.9 × 0.7 × 4 mm3; slices, 35; echo time (TE) = 2.46 ms; repetition time (TR) = 250 ms; averages, 1; acquisition time (TA) = 1.25 min; flip angle, 70°; bandwidth (BW), 330 Hz/Px; base resolution, 320.

31P MRS used a 2D-CSI sequence with a 8 × 8 voxel isotropic matrix (voxel size, 25 × 25 × 25 mm3) and the following parameters: FOV, 20 × 20 cm; TE = 2.3 ms; TR = 3000 ms; averages, 45; TA = 20.15 min; tip angle, 90°, complex points, 1.024; BW, 2 kHz.

The MPRAGE sequence used the following parameters: FOV, 25.6 × 25.6 cm; TE = 3.37 ms; TR = 1900 ms; averages, 1; TA = 3.55 min; TI = 900 ms; flip angle, 9°; BW, 200 Hz/Px; in-plane matrix size, 256 × 256; voxel size, 1 × 1 × 1 mm3; parallel imaging technique mode, generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisition.

Segmentation.

Three-dimensional MPRAGE datasets (1 mm3) were segmented using SPM12 (statistical parametric mapping, The Welcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). A fixed set of cubic 8 × 8 (25 mm)3 volumes of interest identical to the CSI grid was created with Pmod 3.2.1 (Pmod) and the individual raw MPRAGE datasets were manually coregistered to the grid position at the 2D flash images. The same affine transformation was applied to the binary segment masks created by SPM and the respective fraction occupied by gray matter, white matter, and CSF was read out.

Quantification.

Phantoms were prepared that matched in vivo conditions in the brain tissue. Since each 31P compound has distinct physical MR properties, such as relaxation counterparts given by the biological environment, in vivo T1 of PCr, ATP, and Pi had to be determined first to assure optimal matching of the matrix (i.e., other constituents apart from the analytes of interest). The applied CSI sequence differed from other sequences (image-selected in vivo spectroscopy or full saturated recovery) due to rest phasing and nonsaturation effects. Therefore, literature values of the in vivo T1 time of 31P compounds could not be applied to the current settings. We performed saturation studies in four subjects to determine the T1. The subjects were measured repeatedly in runs of ascending repetition times (TR = 550, 1000, 1700, 2500, 3000, 4000, 5000, 6500, 8000, 10,000, and 12,000 ms) which were partitioned onto three sessions while maintaining all other CSI parameters. Curves of the following form (Eq. 1) were fitted to the individual data points of signal integrals at the preselected TR:

|

Up to now, most phantom compositions reported contained GdCl3 and agarose gel as T1 and T2 modifiers, matching in vivo 1H relaxation rates of brain tissue in 3 T instruments (Blenman et al., 2006). Some 31P MRS phantom studies have answered basic questions about signal assignment, pH-related and Mg2+-related signal shifts, and fine structures at high-spectral resolution (Lu et al., 2014a,b). To calibrate signal integrals in the present settings, phantoms of progressively more complex composition and shape were prepared (Table 1). First 2.5 mM pure PCr (as Na2PCr × 4 H2O) were dissolved in 1500 ml H2O, the pH adjusted to 7.4 with HCl and then measured. Then 3.5 mM ATP (as Na2ATP) and 1.0 mM Pi (as NaH2PO4 × 2 H2O) were added and the pH adjusted with NaOH to 7.4. Subsequently, solutions with defined concentrations of Gd (0.1–25 μM, as GdCl3), Mg (1–10 mM, as MgCl2 × 6 H2O), agarose (0.07–0.6%), and KCl (140 mM as KCl) were prepared. The resulting concentrations of Na ranged between 3 and 20 mM. If agarose was used, it was heated in 1300 ml of pure water to dissolve and made up with an aliquot (200 ml) of cold solution containing the scheduled masses of other compounds. All components were not heated together because 12 min in a conventional microwave oven at 800 W would have caused PCr to react to a product appearing as a second peak at 1 ppm, accounting for up to 30% of the total PCr-related signal integral.

Table 1.

Relaxation times (T1) in a mixture of 2.5 mM PCr, 3.5 mM ATP, and 1.0 mM Pi while varying type and concentration of modifiers in the matrix

| Concentration | PCr | γ-ATP | Pi | Concentration | PCr | ɣ-ATP | Pi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (ms) | T1 (ms) | T1 (ms) | T1 (ms) | T1 (ms) | T1 (ms) | ||

| Gd (μM) | Mg (mM) | ||||||

| 0 | 5812 | 5608 | 7269 | 0 | 5812 | 5608 | 7269 |

| 0.1 | 4706 | 1780 | 7300 | 1 | 5365 | 3393 | 7600 |

| 0.2 | 4600 | 1163 | 6820 | 1.5 | 3636 | 7665 | |

| 1 | — | 263 | — | 2 | 5431 | 3566 | — |

| 1.5 | 4200 | — | 6200 | 2.5 | 5401 | 3358 | 6666 |

| 8 | 3501 | — | 4218 | 3.5 | 5693 | 3250 | 6848 |

| 14 | 2093 | — | 2722 | 6 | 4948 | 2499 | 6074 |

| 25 | 1486 | — | 1994 | 10 | 5213 | 1795 | 6300 |

| Agarose (%) | K (mM) | ||||||

| 0 | 5812 | 5608 | 7269 | 140 | 5061 | 3793 | 7285 |

| 0.07 | 5170 | 1468 | 7253 | ||||

| 0.2 | 5600 | 765 | 6700 | K + Mg (mM) | |||

| 0.4 | 5091 | 325 | 4643 | 140 + 1.5 | 5016 | 3044 | 6688 |

| 0.6 | 4939 | — | 4161 |

At each measurement 1.5 L of solution adjusted to pH 7.4 was submitted to a 31P spectroscopy saturation study at 13 different repetition times. T1 were determined using Equation 1.

The same T1 saturation studies were performed as in vivo with ascending TR and additional steps at 15,000 and 20,000 ms. Once the optimal composition of modifiers was determined, phantoms of 1500 ml volume containing different concentrations of PCr, ATP, and Pi (1–6.4 mM) were prepared and measured to calibrate in vivo results. Finally, an agarose gel preparation (0.4%) with in vivo concentrations of close to 2.5 mM PCr, 3.5 mM ATP, and 1.0 mM Pi was sealed into a thin plastic bag and placed into a human skull to match geometry, eventual disturbance of field homogeneity, or signal by the solid encasement and positioning in the coil and MR scanner.

Data processing.

All in vivo and phantom Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) MRS data were analyzed with Tarquin 4.3.10 (Wilson et al., 2011). All data underwent a Fourier transformation and zero and first-order phase correction and were fitted as linear combinations of the simulated metabolic basis set, including PCr, ATP, Pi, phosphoethanolamine (PE), glycerophosphocholine (GPC), and glycerophosphoethanolamine (GPE). While PCr, Pi, PE, GPC, and GPE appear as a singlet Lorentzian peak, signals from the α and γ phosphor atoms in ATP were modeled as doublet and β-ATP as triplet accounting for the homonuclear j-coupling (16 Hz) with one or two neighbors, respectively.

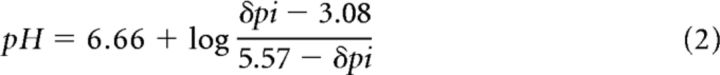

Even though in vivo signals at the γ-ATP and α-ATP chemical shift position may not originate from ATP alone, but from superpositions with ADP, aminomonophosphate, and other nucleotides, γ-ATP and not β-ATP was used due to a better signal-to-noise ratio here. By convention, PCr was set at 0 ppm as the spectral reference. The k-space filter was switched on. The initial β value, which determines the mixing ratio of Lorentzian and Gaussian (Voigt) lineshape, was chosen at 1000 Hz2 (Marshall et al., 1997; Lu et al., 2013; Novak et al., 2014) and both the maximum metabolite and the maximum broad shift were set at 3.0 ppm. In addition, all 31P spectra were 1H decoupled. In postprocessing, a zero-filling factor of 2 and a line broadening of 10 Hz were applied. Figure 1B shows one individual 31P spectrum of one voxel covering the left thalamus (row 5, column 5) at 9 A.M. From the chemical shift of the Pi signal, apparent pH values were calculated according to the derivative of the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation (Eq. 2; Petroff et al., 1985; Huang et al., 2016) as follows:

|

Statistics.

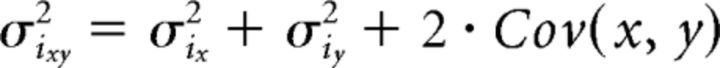

Since the study was longitudinal, the within-subject version of the two-tailed t test was applicable for comparison of means. The variable quality of spectra from voxel to voxel was taken into account by weighting every single data point by the reciprocal square of its absolute SD (σi) put out by the Tarquin software (weighting factor wi = 1/σi2). If combinations of single values at conditions X and Y are considered, they have to be weighted according to the probability of the combination event with a weighting factor wixy = 1/σixy2 whereby the variance of the combination is as follows:

|

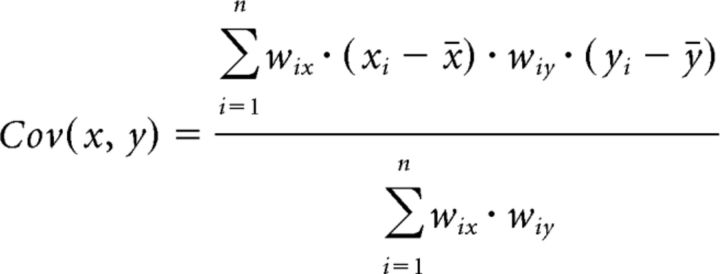

with Cov, covariance of x, y;

|

with yi and xi the individual signal level of PCr, Pi, or γ-ATP respectively at the respective condition and x̄, ȳ weighted averages of individual values at the x and y condition.

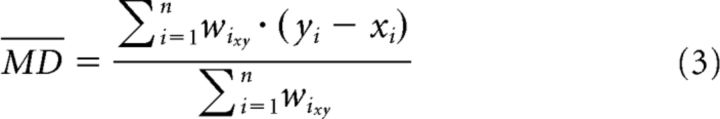

The weighted mean difference MD of a parameter between two conditions, i.e., 5 P.M. versus 9 A.M. (n = 30), Nap1 versus 5 P.M. (n = 15), Nap2 versus 5 P.M. (n = 13), Wake1 and Wake2 versus 5 P.M. (n = 10) calculated throughout subjects for a given voxel as follows (Eq. 3):

|

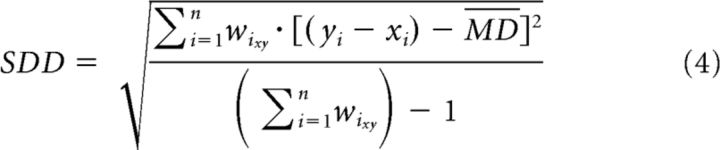

The weighted SD of differences (SDD) was calculated as follows (Eq. 4):

|

The T value is then defined as follows (Eq. 5):

|

The corresponding p-value was calculated using the t, p conversion table integrated in Microsoft Excel as tvert(abs(t); n-2;2), with n − 2 degrees of freedom and two sides (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 1996). Significance thresholds were adjusted according to the Benjamini–Hochberg approach (Holm, 1979; Benjamini and Hockberg, 1995) to control for multiple testing. As 16 regions were tested at four conditions, the α thresholds were 0.05 × 1/64; 0.05 × 2/64; 0.05 × 3/64, and so on.

The logarithmic pH values were transformed to linear [H3O]+ concentrations before calculating means, SDs, and differences and thereafter back-transformed to the pH scale. SDs of individual data points were not available for pH.

Results

In vivo measurements

We used 31P-MRS to investigate levels of PCr, ATP, and Pi in 30 healthy humans at 9 A.M. and 5 P.M. awake and then either after a delay of 7 min to fall asleep during the first and second 20 min of an afternoon nap ending at 6 P.M. or as control during continued waking. Spectra were obtained from 16 voxels as listed in Tables 2 and 3. The resulting peak integrals of PCr, ATP, and Pi signals were compared between morning, afternoon, nap, and control conditions. Changes of the three analytes levels and the metabolic ratio Pi/PCr between conditions averaged across all subjects are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Changes of PCr, Pi, and total nucleotides levels (γ-ATP signal) throughout 16 voxels awake at 9 A.M., 5 P.M., and while napping (n1, n2) compared to wake controls (w1, w2)

| Voxel No. | Hemisphere | Anatomical label | PCr |

Pi |

Metabolic ratio Pi/PCr |

γ-ATP (NxP)i |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 vs 9a | n1 vs 5b | n2 vs 5c | 5 vs 9a | n1 vs 5b | n2 vs 5c | 5 vs 9a | n1 vs 5b | n2 vs 5c | 5 vs 9a | n1 vs 5b | n2 vs 5c | |||

| w1 vs 5d | w2 vs 5d | w1 vs 5d | w2 vs 5d | w1 vs 5d | w2 vs 5d | w1 vs 5d | w2 vs 5d | |||||||

| R4C3 | Right | Insula | −0.4% | 0.6% | 2.5% | −6.4%* | 11% | 17% | −9% | 16% | 25% | −0.7% | 6.8% | 9.4% |

| 4.2% | 4.2% | 9% | 4% | −10% | 15% | 4.4% | −3.3% | |||||||

| R4C6 | Left | −3.5% | 1.5% | 0.9% | 6.3% | 7% | −4% | 0% | 4% | −5% | 2.7% | 3.8% | −2.5% | |

| −3.3% | −3.3% | 18% | 11% | 5% | 4% | −7.0% | 3.2% | |||||||

| R5C3 | Right | Temporal transversal | 0.5% | −0.6% | 0.9% | −8.4% | −2% | −4% | −8% | −3% | −4% | 2.1% | 2.1% | 1.8% |

| −1.1% | 5.9% | −2% | −10% | −6% | −11% | −5.7% | −8.6% | |||||||

| R5C6 | Left | −3.4% | 2.4% | 2.5% | −6.2% | −2% | −7% | −1% | −4% | −7% | −0.6% | −2.4% | −3.2% | |

| −0.5% | 5.0% | 5% | −6% | −1% | −6% | 3.3% | −11.7% | |||||||

| R6C3 | Right | Temporal medulla | −1.5% | 6.5%* | 5.1% | −5.0% | −5% | −15%* | 2% | −10% | −18%* | 2.6% | 5.9% | −12.7% |

| −3.8% | −4.9% | −2% | −8% | −4% | −6% | −6.1% | −7.2% | |||||||

| R6C6 | Left | −2.4% | 3.3% | −0.6% | −11% | 1% | −1% | −8% | −1% | −2% | 2.8% | −8.8% | −3.6% | |

| 4.9% | 5.9% | 15% | 7% | −4% | −1% | −4.1% | 11.4% | |||||||

| R7C3 | Right | Occipitotemporal | −2.1% | 2.1% | −0.1% | 2.0% | −12% | −15% | 3% | −16%* | −18%* | −1.7% | 0.3% | −7.0% |

| 1.7% | 0.3% | 3% | 2% | −8% | 8% | −1.0% | −8.8% | |||||||

| R7C6 | Left | −2.0% | −0.1% | −3.4% | −7.1% | −13% | −5% | 5% | −16%* | −4% | −1.0% | 0.6% | 5.3% | |

| 1.1% | 4.0% | −7% | −2% | −12% | 5% | −3.8% | −8.0% | |||||||

| R3C4 | Right | Anterior cingulum | −2.0% | 2.1% | 5.6% | −0.1% | 1% | −7% | 4% | −8% | −17% | 7.8% | 2.4% | 9.6% |

| 0.2% | 3.3% | 6% | 1% | −2% | −14% | 1.7% | −3.3% | |||||||

| R3C5 | Left | 0.2% | 1.8% | 2.1% | 1.6% | 1% | −3% | 3% | −6% | −10% | 5.8% | 5.0% | 9.2% | |

| −6.5% | 4.4% | −10% | 0% | −7% | 11% | 3.4% | 1.1% | |||||||

| R4C4 | Right | Caudate-putamen | −1.6% | 6.0% | 4.9% | −8.9% | 9% | 6% | −7% | 3% | 2% | −5.7% | 10.0%* | 5.1% |

| −4.6% | −2.5% | −8% | 5% | 7% | −1% | −1.2% | −6.1% | |||||||

| R4C5 | Left | −2.0% | 0.8% | 2.2% | 8.5% | 4% | 5% | 10% | 2% | 3% | −4.7% | 2.7% | −0.6% | |

| −4.5% | 0.4% | −11% | 1% | −3% | 3% | 1.5% | −3.0% | |||||||

| R5C4 | Right | Thalamus | −1.9% | 2.6% | 1.8% | 2.4% | −4% | 7% | 2% | −7% | 5% | −0.2% | −0.3% | −0.8% |

| 0.7% | −2.0% | −6% | −15% | −14% | −11% | −3.6% | −4.0% | |||||||

| R5C5 | Left | −7.0e | 5.4%h | 5.2%* | 17.1%g | −15%* | −11% | 28%g | −16%* | −17%* | −2.8% | 4.1% | 0.9% | |

| −1.0% | 1.4% | 2% | −2% | 2% | −5% | −5.2% | 8.2% | |||||||

| R7C4 | Right | Occipitomedial | −1.0% | 1.6% | 1.1% | 4.6% | −8% | −15%* | 7% | −12% | −15%* | −0.9% | 1.8% | 3.5% |

| 1.0% | 5.2% | 2% | 1% | −4% | −23% | −2.2% | −0.2% | |||||||

| R7C5 | Left | −2.3% | 0.1% | 2.2% | −0.3% | −4% | 1% | 3% | −5% | −2% | −4.2% | −1.1% | 0.7% | |

| 4.2% | 3.1% | −4% | 6% | −6% | 0% | −0.6% | 3.7% | |||||||

aAfternoon (5 P.M.) versus morning (9 A.M.) averaged across 30 subjects.

bFirst scan after sleep onset (Nap1) versus awake at afternoon (5 P.M.) averaged across 15 subjects.

cSecond scan after sleep onset (Nap2) versus afternoon (5 P.M.) averaged across 13 subjects.

dSecond and third scan awake versus the first within the 5 P.M. session averaged across 10 control subjects.

eChanges with p values of 7.0 × 10−6 that survived Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

fChanges with p values of 5.0 × 10−5 that survived Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

gChanges with p values of 0.0046 that survived Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

hChanges with p values of 0.007 that did not survive Benjamini-Hochberg correction.

iNxP, minor contributions of any nucleoside phosphate such as ADP, GTP, GDP.

*Changes with p values of 0.01 < p < 0.05 that did not survive Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

Table 3.

Comparison of PCr, Pi/PCr, and total nucleotides (γ-ATP signal) levels in the left hemisphere versus right hemisphere throughout eight pairs of homologue voxels and throughout conditions awake at 9 A.M., 5 P.M., while napping (Nap1, Nap2) and in wake controls (Wake1, Wake2)

| Voxel No. | Region | PCr |

Metabolic ratio Pi/PCr |

γ-ATP (NxP)e |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 A.M. | 5 P.M. | Nap1 | Nap2 | 9 A.M. | 5 P.M. | Nap1 | Nap2 | 9 A.M. | 5 P.M. | Nap1 | Nap2 | ||

| Wake1 | Wake2 | Wake1 | Wake2 | Wake1 | Wake2 | ||||||||

| R4C6 vs R4C3 |

Insula | 4% | 3.5% | 3% | −1.3% | −10% | −1.2% | 9.3% | 2.4% | 5.2% | 4.9% | 7% | −7.1% |

| −2.9% | 8.3% | −17% | 2.3% | −9.3% | 14.4% | ||||||||

| R5C6 vs R5C3 |

Temporal transversal | −6%c | −6.4%d | −6.8%d | −10%d | −7.8% | −7.7% | 6.9% | −2.5% | −5.7% | 3.5% | −4.1% | −2.6% |

| −7.5%* | −1.3% | −6.1% | 1.7% | −24%d | −16%d | ||||||||

| R6C6 vs R6C3 |

Temporal medulla | −9.2%b | −7%d | −10%d | −11%d | −4.3% | −13% | 8.5% | −0.3% | −8.2% | −5% | −8.2% | 0.1% |

| −6.8%b | −7.15% | 7.8% | 21%* | −10.5% | 8.3% | ||||||||

| R7C6 vs R7C3 |

Occipitotemporal | 2.1% | −7.8% | 3.2% | −3.7% | −3.7% | −2% | 7.8% | 13.2% | −5.2% | −1.6% | −12% | 0.9% |

| −2.6% | −3.1% | −17.6% | 12.4% | 18.3% | 4.2% | ||||||||

| R3C5 vs R3C4 |

Anterior cingulum | −5.7% | −5.1% | 4% | 6.7% | 8.1% | 10% | 2.3% | 12% | 4.4% | −2% | 7.6 | 0.8% |

| 5% | 12.3% | 16.2% | 3.4% | −0.9% | −2.3% | ||||||||

| R4C5 vs R4C4 |

Caudate-putamen | 2.7% | 2% | 1.2% | 3.4% | −9% | 6.4% | 5.7% | 13.7% | 4.12% | 1.3% | 3.1% | −1% |

| 6.4% | 5.4% | −15.5% | −4.9% | −12.4% | −0.5% | ||||||||

| R5C5 vs R5C4 |

Thalamus | 1.6% | −6.7%a | −6%b | −4.9%d | −6.5% | 12.3%d | 4.9% | −2.2% | −4.6% | −7.5%* | 3.1% | −3.9% |

| −6.1%a | −1.8% | 36%* | 23% | −19.4%d | −12.3% | ||||||||

| R7C5 vs R7C4 |

Occipitomedial | −1.8% | 1.9% | −3.1% | −1.8% | −15% | 3.7% | 6.1% | 3.4% | −0.6% | 0.15% | −1.3% | −3.4% |

| −2.9% | −3.5% | −24% | −16% | −4.4% | −1.8% | ||||||||

The numbers of subjects n were the same as in Table 2.

ap values of 7.0 × 10−5< p < 6.5 × 10−5 that survived Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

bp values of 4.1 × 10−4 < p < 4.0 × 10−4 that survived Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

cp values of 7.0 × 10−4.

dp values of 0.0011 < p < 0.0074 that survived Benjamini-Hochberg correction.

eNxP, minor contributions of any nucleoside phosphate such as ADP, GTP, GDP.

*p-values of 0.01 < p < 0.05 that did not survive Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

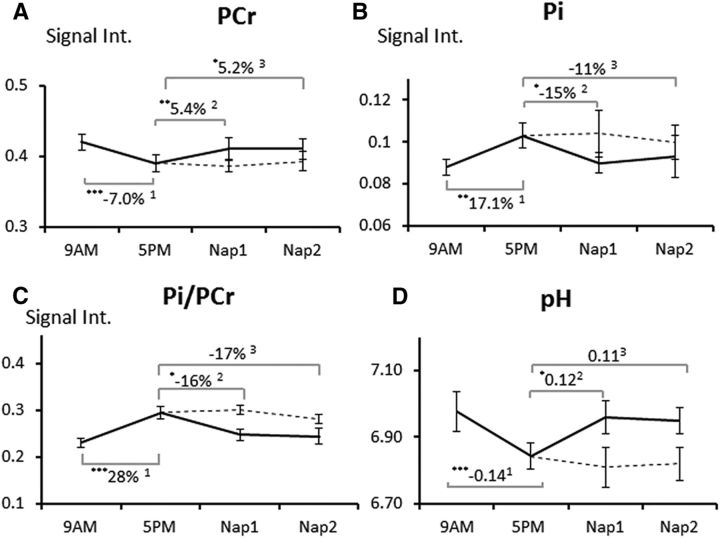

In the left thalamus, PCr decreased significantly by 7.0 ± 0.8% at 5 P.M. compared with 9 A.M. (p = 7.0·10−6, t = −5.5, n = 30; Fig. 2A). PCr recovered incompletely (>80%) by 5.4 ± 1.7% (p = 0.007, t = 3.2) after 20 min of napping. There was no additional effect with rather higher scatter after 40 min of napping. Pi showed an inverse pattern: an increase at the 5 P.M. condition versus 9 A.M. baseline by 17.1 ± 5% (p = 0.005, t = 3.1) was followed by a decrease of 15 ± 6% (p = 0.02, t = −2.6) after a 20 min nap (Fig. 2B). A course of apparent pH of 6.98 (95% CI 6.83–7.08), 6.84 (95% CI 6.74–6.94), 6.96 (95% CI 6.86–7.04), and 6.95 (95% CI 6.89–7.01) was calculated for the morning, afternoon, and first and second 20 min of nap conditions (Fig. 2D). Controls showed no significant changes across the three consecutive scans between 5 P.M. and 6 P.M. Here, data from the last scan were more scattered. Percentage changes of PCr, Pi levels, Pi/PCr, and pH in the left thalamus are indicated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A–D, Plots of the courses of PCr (A), Pi (B), metabolic ratio Pi/PCr (C), and pH level (D) in the left thalamus 15.6 ml voxel throughout the four conditions assessed. Dotted lines represent the control group that did not nap. Note the inverse course of Pi and Pi/PCr versus PCr and pH, respectively.

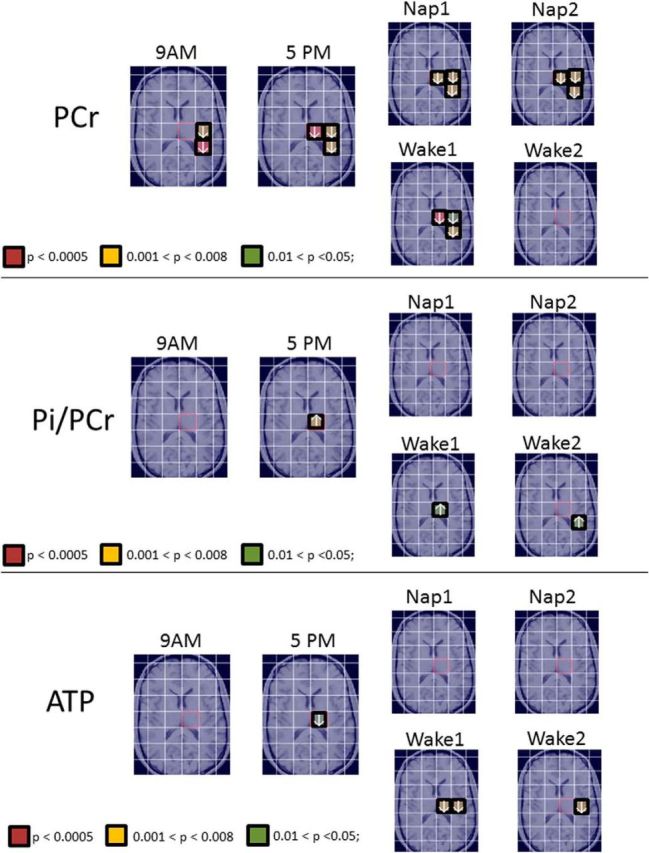

The PCr/ATP ratio was 1.6 averaged across all voxels, conditions, and individuals. The γ-ATP signal, a cumulative measure of the nucleotide inventory, underwent no significant change. Importantly, the parameters PCr, Pi, and Pi/PCr (Fig. 3A) did not show any significant changes in the other investigated voxels. We did not find respective changes in the right thalamus.

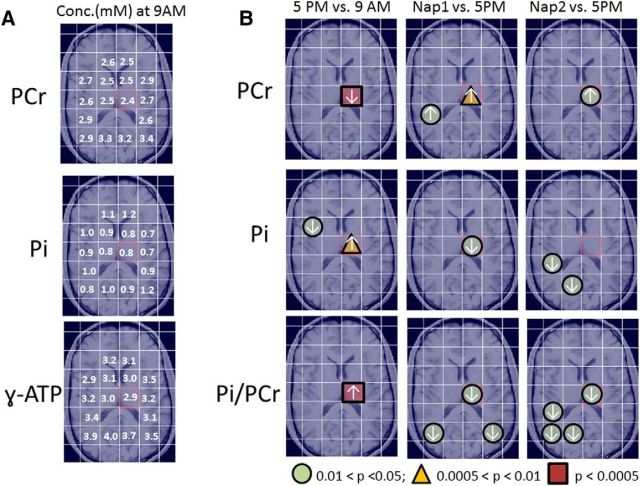

Figure 3.

A, Voxelwise concentrations of PCr, Pi, and γ-ATP at 9 A.M. B, Localization of the observed significant changes between conditions within the CSI grid overlaid onto an axial MRI.

In the right occipital and posterior temporal and right insular region, some observed changes with p < 0.05 did not withstand Benjamini–Hochberg corrections (Table 2). Figure 3B illustrates the localization of voxels with significant changes of PCr, γ-ATP, and Pi at 5 P.M. and after the nap.

In the thalamus a significant left–right side difference became apparent only in the afternoon (−6.7 ± 1.3%, p = 1.6·10−5, t = −6.8) but not in the morning (−1.9 ± 1.4%, p = 0.3, t = −1.2, n = 30; Fig. 1E). Conversely, the right temporal medullar and transveral hemispheric PCr significantly exceeded the left at all conditions (see Fig. 4; Table 3) by an average of 7.4%. However, the latter findings outside the isocenter may be interpreted in view of spatial field inhomogeneities and different fractions of gray matter, white matter, and CSF included in the voxel homologues.

Figure 4.

Illustration of voxels displaying significant left–right hemispheric differences of PCr, Pi/PCr, and ATP level throughout 16 voxels at 9 A.M. and 5 P.M. for all subjects, while napping (Nap1, Nap2) for napping subjects, and while awake for wake controls (Wake1, Wake2).

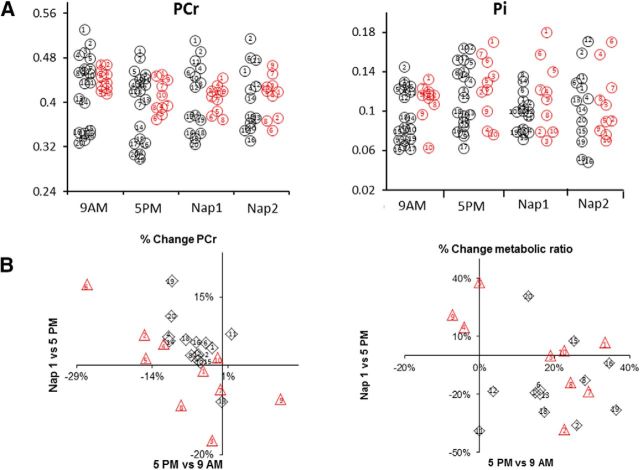

The average between-subject variabilities across all regions, conditions, and subjects were characterized by coefficients of variation of 13.5% for PCr, 24.3% for the Pi signal, and 10.1% for the γ-ATP signal. Scatter plots of individual data points are given in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

A, Scatter plots of individual changes of PCr and Pi in the left thalamus throughout four conditions for both subjects who napped (black circles) and controls (red circles). B, Individual changes of PCr and Pi/PCr in nap versus wake at 5 P.M. plotted as a function of changes in awake state in the course of the day (5 P.M. vs 9 A.M.). Red triangles represent the respective changes within the control group that stayed awake during all four scans and black diamonds the group that napped. Note the vertical shift between the test and control cluster of data points.

Reproducibility and reliability

Two subjects underwent the entire protocol of morning, afternoon, and nap scans twice on 2 different days. The coefficient of variation for repeated measurements at equivalent conditions was 3.1% for the left thalamic region (two replicates and two subjects). PCr level changes in the thalamus voxel between the morning and afternoon conditions were −4.5 and −3.9% in Subject 1 and −5.7% and −8.0% in Subject 2, respectively. To exclude any left–right asymmetry of the instrumentation, Subject 2 was scanned in prone and in supine positions at either condition. Clearly, regardless of whether the voxel's position was left or right from the isocenter of the scanner, it was constantly the left thalamus voxel that showed lower PCr values than the contralateral thalamus and a decrease of PCr in the afternoon scan. The respective decrease amounted to −5 or −6% in the supine and prone position, respectively. Repeated measurements of a reference phantom containing 2.7 mM PCr at 9 A.M. and 5 P.M. on 3 different days showed a coefficient of variation of PCr levels of 0.6%.

Origin of 31P-MRS signals

At the present medium field regime of B0 ≈ 3 T, the dipolar interaction and not the chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) can be considered as the prevailing relaxation mechanism (Cohen and Burt, 1977; Evelhoch et al., 1985; Mathur-De Vré et al., 1990). In our study, the addition of ATP and Pi did not affect the T1 relaxation time of PCr. Hence, it can be assumed that 1H-31P intermolecular dipol–dipol interaction (DD) with H2O contributed most to the relaxation of PCr. As intramolecular protons are not adjacent to the heteronucleus 31P, the intramolecular DD can be neglected. Also, contributions of the spin rotation and the scalar relaxation can be neglected in small P molecules.

With respect to subcellular localization, the cytosol with a viscosity approximately the same as water [0.7–2.0 centipoise (cP)] provides a high mobility of 31P metabolites and short correlation times (τ) in contrast to mitochondria with a viscosity of >100 cP (Luby-Phelps, 2000). Apparent diffusion ranges of PCr were estimated at 2 μm in the mitochondrial matrix and at ≈66 μm within the cytosol with diffusion coefficients of DPCr = 0.08 × 10−3 mm2/s and 0.28 × 10−3 mm2/s, respectively (Gabr et al., 2011). Furthermore, due to the composition of membrane folds (cristae) in stack-like arrangements every 40–100 nm and small overall size (0.7–3.0 μm), the mitochondria provide multiple 31P relaxation partners causing very short relaxation times and low 31P signals. While ATP is produced at the matrix site of the ATP-synthase and thus concentrated in the mitochondrial M-space, the mitochondrial isoform of creatin kinase is localized between inner and outer membrane in the mitochondrial C-space. Thus the C-space is the site of production of PCr (Wallimann et al., 1992). Space there is even narrower (≈2–20 nm width) and thus diffusion is more restricted. Hence, it can be concluded that the received MRS signals of PCr and ATP are of almost exclusive intracellular cytosol localization and thus are the receivid MRS signals.

Regarding Pi, at 7 T additional Pi signals with shorter T1 could be differentiated at ∼5.2 ppm from the major Pi signal at 4.8 ppm and assigned to more alkaline and viscous compartments, such as mitochondria (pH ≈7.9; Kan et al., 2010). Comparing different pharmacologic interventions versus baseline, other Pi signals could be attributed to extracellular space (pH ≈7.3) at 7 T (Gilboe et al., 1998). Such fine structures could not be resolved by our 3 T equipment. The model implemented in Tarquin uses a Pi basic signal centered at 4.8 ppm and thus may largely reflect cytosolic Pi (pH ≈7.0; Gilboe et al., 1998).

A further issue is the mutual contribution of white matter and gray matter to the received 31P signal. As mentioned in the introduction, Plante and coworkers (2014) extrapolated PCr levels in pure white matter and pure gray matter by linear regression of 31P signals and tissue type fraction over 84 voxels. At baseline, nonsignificantly slightly higher PCr levels in white matter (4.06) than in gray matter (3.94) were reported. They observed a nonsignificant decrease of PCr by 3.9% from baseline to SD and a significant increase by 7.3% to recovery sleep in gray matter and no effect in white matter. A similar regression analysis at baseline of Hetherington et al. (2001) yielded 3.53 mM PCr in gray matter and 3.33 mM PCr in white matter, not differing significantly. Also, we determined the fraction of gray matter, white matter, and CSF in each voxel by readout of an analog grid in coregistered and segmented MPRAGE images as presented in Table 4. Group averages of tissue fractions were almost identical in homologous left and right hemispheric voxels and no correlation of hemispheric differences in signals of PCr, Pi, and Pi/PCr, and of gray matter and white matter fractions could be observed. The major constituent of the thalamus voxel in our study was white matter (67%). Whereas individual differences between left and right averaged 0.9% for gray matter and −2.8% for white matter here, PCr differed by −1.9% at baseline and −6.7% at 5 P.M. In the temporal voxels R5C6 versus R5C3 and R6C6 versus R6C3, gray matter differed by −0.2 and −3.1%, respectively, and white matter by 1.0 and 2.6%, whereas static side differences of PCr averaged −6.4 and −8.5% (i.e., right dominating). Thus, it can be concluded that PCr is affected much more by functional issues than by structural issues.

Table 4.

Fractions of gray matter, white matter, and CSF within each voxel, extracted from segments of coregistered MPRAGE datasets, averages across 18 subjects

| Voxel No. | Hemisphere | Anatomical label | Average fraction |

SD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gray matter | White matter | CSF | Gray matter | White matter | CSF | |||

| R4C3 | Right | Insula | 0.63 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| R4C6 | Left | 0.62 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.04 | |

| R5C3 | Right | Temporal transversal | 0.54 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| R5C6 | Left | 0.54 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.03 | |

| R6C3 | Right | Temporal medulla | 0.34 | 0.58 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| R6C6 | Left | 0.31 | 0.61 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| R7C3 | Right | Occipitotemporal | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| R7C6 | Left | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.02 | |

| R3C4 | Right | Anterior cingulum | 0.34 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| R3C5 | Left | 0.36 | 0.56 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.03 | |

| R4C4 | Right | Caudate-putamen | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| R4C5 | Left | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| R5C4 | Right | Thalamus | 0.24 | 0.68 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| R5C5 | Left | 0.25 | 0.65 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | |

| R7C4 | Right | Occipitomedial | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| R7C5 | Left | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.05 | |

Quantitation and in vitro validation

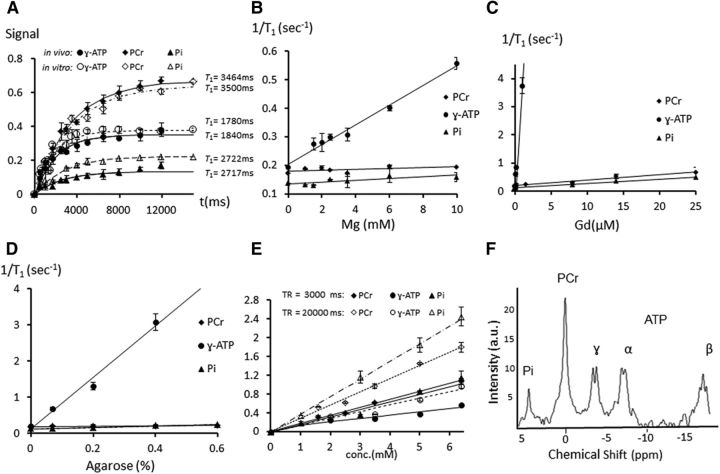

Figure 6A shows 31P-MRS signal saturation studies, curve fits, and resulting T1 of four subjects. The resulting average in the left thalamus voxel was T1 = 3464 ± 371 ms for PCr, T1 = 1840 ± 518 ms for ATP, and T1 = 2717 ± 462 ms for Pi. Consistent with variations of the water content of the brain tissue throughout regions, different T1 values were observed in different (25 mm)3 voxels. Short T1 values were observed in the thalamus voxel, which contained a high fraction of white matter (67%), whereby longer relaxation times occurred in the voxels covering the left insula (T1 = 3733 ± 480 ms, R4C6) or the posterior cingulum (T1 = 3708 ± 673 ms, R6C5) with a higher amount of gray matter (62 and 39%, respectively) and CSF (13 and 28%, respectively). Measurements of progressively more complex phantoms consequently followed pH adjustment to 7.4 and started with 2.5 mM pure PCr in water yielding T1 = 6062 ± 253 ms. Next 3.5 mM ATP and 1.0 mM Pi were added, resulting in T1 = 5812 ± 500 ms for PCr, T1 = 5608 ± 97 ms for ATP, and T1 = 7269 ± 16 ms for Pi. The in vivo T1 of PCr of 3464 ± 371 ms to 3733 ± 480 ms found by us was close to the literature range of 2700–3570 ms reported by Blenman et al. (2006). The observed in vivo test–retest coefficient of variation (CV) of 3.1% outperformed the interassay intraindividual CV of 4.2% reported by Kato et al. (1994).

Figure 6.

31P-MRS signal saturation studies of PCr, γ-ATP, and Pi, of relaxation times (T1), and of relaxation rates (1/T1): A, Comparison of saturation curves in vivo in four subjects with those of best matching phantom preparations containing all 2.5 mM PCr, 3.5 mM ATP, and 1.0 mM Pi and 8 μM Gd for PCr, 0.1 μM Gd for ATP, and 14 μM Gd for Pi. B–D, Relaxation rate (1/T1) of PCr, γ-ATP, and Pi in solutions with different concentrations of Mg2+ (1–10 mM), Gd (0.07–25 μM) and agarose (0.07–0.6%). E, Calibration lines for PCr (diamond), ATP (circle) and Pi (triangle) signal covering the concentration range 1–6.4 mM measured at TR = 3000 ms (filled symbols) and at saturated level with TR = 20 000 ms (open symbols). The in vivo PCr, γ-ATP and Pi level in the thalamus region at 9 AM corresponded to a concentration of 2.40, 2.91 and 0.8 mM (n = 30), respectively. Error bars indicate SEM. F, 31P spectrum of the R5, C5 voxel of a phantom containing 2.5 mM PCr, 3.5 mM ATP, 1.0 mM Pi and 0.44% agarose placed inside a human skull.

Because complexes of ATP and Mg have been reported as active species in vivo (Cohen and Burt, 1977), we also studied Mg as matrix additive. Here variations of concentrations of Mg2+ (1–10 mM) and the addition of 140 mM KCl to mimic cytosol barely influenced T1 of PCr and Pi (Fig. 6B). In agreement with Cohen and Burt (1977), Mg ≤10 mM increased the relaxation rate of PCr and Pi by <16%. In contrast, relaxation rates of the γ-ATP signal considerably increased with increasing Mg concentrations by ≤68%. However, short T1 as observed in vivo could not be reached at Mg concentrations in the relevant range of 0.5–2 mM and also not by combination of Mg, K, and Cl (Table 1). Thus, macromolecular and viscosity factors must also account for the shortening of γ-ATP T1 in vivo.

Subsequently, to reach in vivo conditions, a series of measurements with T1 modifiers, i.e., Gd (0.07–25 μM) and agarose gel (0.07–0.6%), were conducted. In contrast to Mg, the paramagnetic T1 modifier Gd (0.07–25 μM) and the viscous agarose caused a stronger T1 shortening effect within increasing concentrations (Fig. 6C,D). Noteworthy here is the strong increase of the relaxation rate (1/T1) of γ-ATP, in contrast to PCr and Pi. This can be explained by the restricted mobility of the large, multiply charged ATP molecule and the associated higher correlation time. Similarly, in the cytosol, polar macromolecules reduce ATP diffusion (DATP = 0.15 mm2/s; Crank, 1976). Diffusion coefficients of PCr and Pi in 1% agarose gel (DPCr = 0.76 × 10−3 mm2/s, DPi = 0.78 × 10−3 mm2/s) that equaled DPCr in water (Gabr et al., 2011) were in agreement with the minimal effect of agarose on T1 of PCr and Pi in our study. Thus, we did not observe differences in the T1 behavior of ATP, PCr, and Pi that could be explained by differential structure-related CSA effects in addition to global matrix-induced effects.

In vivo conditions were best matched at 8 μM Gd for PCr (T1 = 3501 ± 148 ms), which was half of that reported for 1H-MRS, in line with the methodological differences (Blenman et al., 2006) at 0.1 μM Gd for ATP (T1 = 1780 ± 170 ms) and at 14 μM Gd for Pi (T1 = 2722 ± 22 ms; Fig. 6A). Using these measurements, two calibration curves of each metabolite, one at TR = 3000 ms as used in vivo and one at the saturated level of TR = 20,000 ms, were obtained from phantoms with concentrations of 1.6, 2.5, 3.5, 5.0, and 6.4 mM PCr and of 2.0, 3.5, 5.0, and 6.4 mM ATP and Pi (Fig. 6E). Furthermore, to study effects of the geometry and homogeneity of the sample onto the signal, a preparation of 2.5 mM PCr, 3.5 mM ATP and 1 mM Pi and 0.44% agarose was placed inside a human skull. This yielded the same PCr, ATP, and Pi peak integrals as the preparation in a cubic plastic container (Fig. 6F). Each concentration was measured three times. Application of this calibration curve to in vivo data (TR = 3000 ms) of n = 13 subjects who napped and underwent all four scans yielded a left thalamus concentration of 2.57 ± 0.09 mM for PCr, 2.91 ± 0.08 mM for ATP, and 0.81 ± 0.04 mM for Pi at baseline in the morning, a PCr level of 2.41 ± 0.09 mM in the afternoon, and 2.54 ± 0.09 mM and 2.53 ± 0.09 mM during the first and second 20 min nap (Nap1 and Nap2). The respective concentrations of Pi at 5 P.M., Nap1, and Nap2 were 0.97, 0.82, and 0.86 ± 0.04 mM. The measurement of the phantom calibration series yielded a precision, expressed as relative SDs of PCr of 3.73%, ATP of 6.4%, and Pi of 5.6% averaged over all concentrations studied. In the n = 4 subjects in whom entire saturation studies were conducted, application of the calibration line established for standard unsaturated conditions (TR = 3000 ms) to the in vivo signals acquired at 3000 ms yielded concentrations of 2.36 mM PCr. The calibration line established for saturated conditions (12,000 ms) to the in vivo data acquired at 12,000 ms yielded 2.16 mM PCr. The concentrations in the remaining voxels were calculated by applying calibration lines established for each voxel to the respective MRS signal (Fig. 3A).

Plausibility of outcomes in view of current literature

The brain consists of approximately 79% intracellular and 21% extracellular space, (Nioka et al., 1991) the latter including and resembling CSF. PCr and ATP are of almost exclusive intracellular localization and thus is the received MRS signal. The total concentration of PCr has been reported to be 2.5 mM in the brain (Nioka et al., 1991) and ∼0.04 mM in CSF (Agren and Niklasson, 1988; Rao et al., 2018). The concentration of ATP in the brain was 3.0 mM. Meanwhile, the concentrations of ATP, ADP, and AMP in CSF were below the detection limit at 0.05 μM (Harkness et al., 1984). In muscular interstitial fluid, the concentration of ATP was 0.113 μM, the concentration of ADP was 0.052 μM, and the concentration of AMP was 0.351 μM (Mo and Ballard, 2001). As the ratio of ATP/ADP is approximately 7 (e.g., 7.6 in Musch et al., 1980) and that of ADP/AMP again approximately 7 (e.g., 7.7 in Musch et al., 1980) and because adenine nucleotides are considerably more abundant than others, the γ-ATP signal composed of the sum of all nucleotides preferentially reflects ATP. For Pi, CSF concentrations of 1.39 mM (Heipertz et al., 1979) were reported and the signal detected here corresponded to a total brain concentration of 0.74 mM. A direct cross-method validation of in vivo 31P-MRS versus ex vivo enzymatic assay of neutralized tissue homogenate supernatants found only 48% of available Pi detectable by 31P-MRS (Nioka et al., 1991).

Outcome parameters of this study were in the range reported by others. The PCr/γ-ATP ratio of 1.6 found here agreed with the range 1.4–1.8 and specific ratio 1.5 reported by others (Lu et al., 2013; Novak et al., 2014). The concentrations of 2.45 mM PCr observed in the thalamus and of 3.22 mM in the occipital region (averages of left and right at 9 A.M.) and of 2.95 mM ATP and 0.8 mM Pi in the thalamus are close to those of 3.1–3.5 mM PCr in gray matter, 2.9–3.3 mM in white matter, 2.40–2.54 mM in the thalamus, 3.9–4.3 mM in the occipital region, and of global 2.2–3.0 mM ATP and 0.9–1.3 mM Pi found by others (Buchli et al., 1994; Hetherington et al., 2001; Jensen et al., 2002; Du et al., 2007; Dworak et al., 2011; Ren et al., 2015). In our study, in the morning the PCr levels were 2.40 mM in the left and 2.45 mM in the right thalamus (n = 30) whereby the average of individual side differences amounted to −1.9%, the respective numbers were 2.35 mM left, 2.50 mM right, and −6.7% in the evening (n = 30). This was in agreement with results obtained by Jensen et al. (2002) of 2.40 mM in the left and 2.54 mM in the right thalamus amounting to 5.5% difference.

Discussion

Our study revealed a 7.0 ± 0.8% diurnal decrease of PCr in the left thalamus between 9 A.M. and 5 P.M. A nap of 20 min restored PCr by 5.4%. Pi showed inverse changes. Controls that did not nap did not show this reversal to baseline of PCr and Pi. These highly significant data were corroborated by concing in vitro and in vivo evidence. Outcome measures, including an external calibration of absolute analyte concentrations, matched literature values, as we have shown.

Cellular and neurochemical level

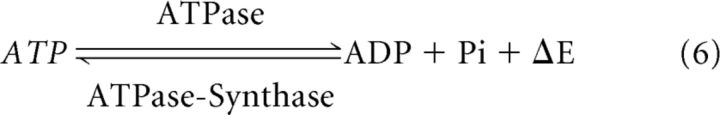

Universally available energy in the cell is provided by ATP breakdown as follows (Eq. 6):

|

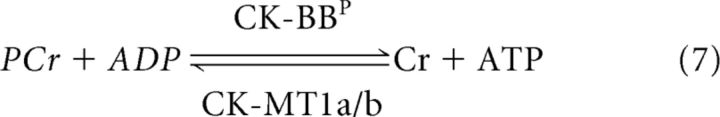

PCr in turn acts as a reservoir for high-energy phosphate bonds to supply peak-load power and to capture ATP overflow. The transfer of this phosphate bond in both directions is catalyzed by the creatine kinase (CK) in the brain by its mitochondrial isoforms CK-MT1a/b and the cytoplasmatic isoform CK-BB (compare Eq. 7). This opens up the established function of PCr as an intracellular energy shuttle from sites of production, such as mitochondria, to sites of consumption (Gabr et al., 2011), as shown in Equation 7:

|

CK can be regulated by phosphorylation, shifting equilibrium to the right (Lin et al., 2009). Consistent with the maintance of this equilibrium, ATP levels of our study underwent the same changes throughout all conditions as PCr, although the changes were not significant. The observed decrease of cytosolic pH in the afternoon might largely result from net hydrolysis of PCr to Pi and Cr. Apparently cerebral storages of Cr/PCr buffer are partially accessible by oral supplementation of Cr (Lyoo et al., 2003; Dworak et al., 2017).

Daytime and thalamic energy consumption

The physiological impact of our main finding is related to thalamic function. The thalamus serves as a gateway, relaying and modulating the information flow to and from mainly primary cortices. This “gate to the neocortex” is essential for the generation of consciousness and alertness (Steriade et al., 1993).

Beside the decrease of PCr in the left thalamus between 9 A.M. and 5 P.M., we found a substantial restoration of PCr values after a recreational nap of 20 and 40 min following the scan at 5 P.M. This finding is in line with the relatively short period needed for recreation even after longer times of wakefulness. We have recently shown that another neurochemical marker, A1 adenosine receptors, which increase during 52 h of wakefulness, are restored to control levels during a recovery sleep episode of only 14 h (Elmenhorst et al., 2017). Considering the thalamus as a whole, many [18F]FDG-PET studies (Maquet et al., 1990, 1997; Braun et al., 1997) showed a decreased energy demand during sleep versus wakefulness, e.g., −49% (Maquet et al., 1990) in slow-wave sleep (SWS). Similarly, our study in terms of PCr also showed a lower energy demand during the first period of sleep. Apparently not carrying weight to the macroscopic balance, higher neuronal firing rates (giving origin to spindle waves) were temporally registered within the first 30 min during the transition to low-frequency SWS (Dijk et al., 1987) in subregions, such as the thalamic reticular nucleus.

Aspects of lateralization

Our findings indicate a lateralization of thalamic function, since the increase of Pi/PCr was pronounced in the left thalamus. Lateral and specifically hemispheric specialization is a generally accepted concept of mammalian brains. It is well established for language and handedness as well as for other functions.

Numerous reports describe a side-specific subjection of the thalamus to sleep-associated changes and impacts on connectivity from mediating and propagating signals from sleep generators in forebrain, hypothamamic, and brainstem structures to the cerebral hemispheres in different species (Brown et al., 2012). Also, the “chemical neuroanatomy” shows a strong lateralization.

A prominent example is the norepinephrine system, which is highly relevant for arousal and sleep (Berridge, 2008) and has been shown to modulate thalamic activity (Devilbiss et al., 2006). Oke et al. (1978) showed that norepinephrine concentrations in the left thalamus are in most nuclei 1.5 to >3 times higher than in the right homolog. This “chemical lateralization” will necessarily translate into functional differences. Consistent with this are PET and fMRI studies reporting decreased thalamic activity during visual-vigilance tasks after sleep deprivation (Wu et al., 1991; Thomas et al., 2000), where the left deactivation exceeded the right by a factor of 1.1 and 1.5, respectively. Also, circadian [18F]FDG studies detected a drop of uptake in the afternoon, which was accentuated in the right posterior temporal and occipital region (Buysse et al., 2004; Shannon et al., 2013).

In line with these findings, use-dependent effects have been discussed as underlying hemispherically and regionally differential fatigue or sleep load (Borbély et al., 2016). As the subjects of this study performed scientific office work, which is particularly demanding on the left hemisphere, between the 9 A.M. and 5 P.M. session, lateralization may have been pronounced in this cohort. Temporal PCr levels were found lateralized independent of the condition. These results agree with results showing lower glucose metabolism in left temporal regions best matching the voxels R5C6 and R6C6 of this study versus right in the morning (by −2.6, −3.9%) and in the evening (by −3.4, −3.6%; Shannon et al., 2013). Macquet et al. (1990) observed ∼40% decrease of glucose consumption in SWS versus awake state, which was less pronounced in the left hemisphere by −3.4 and −5.9% in middle and superior temporal regions. These findings could reflect permanent regional differences in the intensity and density of use contrasting with the daytime and sleep-related findings in the thalamus.

In muscle tissue, it is well established that during continued work energy (storage) compounds such as ATP, PCr, lactate, glucose, glucagone, and fats are consumed in that order and as long as stocks last. An overview of our results and those cited strongly suggests that in the brain the disposition on energy reserves does not occur synchronically but rather follows a spatiotemporal cascade as a function of regional wakefulness, activity, sleep, rest, and their intensity. In line with this idea, neuroimages of different activational parameters are not necessarily congruent. In perfectly resting tissue, full PCr stores and minimum [18F]FDG uptake can be expected. At the other end of the scale, beyond aerobic capacity—to limit cellular acidosis—glycolysis and thus [18F]FDG uptake may be downregulated despite deficient PCr reserves. This effect may apply to the more extreme situation of sleep deprivation. Consistent with this interpretation are the findings, by Wu et al. (1991), of a large decrease (−25%) of CMRGlc in the left thalamus after sleep deprivation and the global decrease of PCr after sleep deprivation observed by Plante et al. (2014).

Limitations

First, the voxel defined as “thalamus” did not exactly match the anatomy of this brain structure. This is due to the rigid and predefined grid of relatively large voxels (15.6 ml). As a consequence, a small posterior portion of the thalamus was omitted and adjacent structures, mostly internal capsule and CSF, were included. To estimate these effects, we segmented coregistered MPRAGE image datasets. Since we found no significant differences in the relative tissue portions between the left and right “thalamus” voxel, we can exclude this factor as an explanation for our main finding. Another factor is a lower statistical sensitivity in those voxels with a higher variability of included individual anatomy, such as in peripheral compared with central voxels. As the comparatively thin cortical layer is particularly sensitive to partial volume effects, cortical facets of the observed metabolic changes may have been underestimated.

Finally, we defined the nap status primarily by observational ratings. The physiological records of our subjects matched the reported scope, e.g., for drops in heart rate from wakefulness to sleep stages 1 and 2 as reported by Zemaityte et al. (1986) and Burgess et al. (1999), furthermore corroborated by the lack of awakening during the scan procedure and need for intense wake-up calls thereafter in all subjects. However, future studies could profit from additional EEG recordings and formal vigilance tests.

Summary

This study revealed a highly significant decrease of cytosolic PCr in the left thalamus between 9 A.M. and 5 P.M. accompanied by an inverse increase in Pi. The effect was largely reversible after a short recreational nap. A similar period of quiet waking did not result in the same kind of recovery of Pi/PCr in controls. These findings support a daytime-related energy demand of the thalamus. Further, they provide evidence for a lateralized homeostatic regulation of the thalamus. Conversely to the dynamic lateralization of thalamic PCr, a constantly significant lateralization was observed in the temporal regions through all conditions.

As a methodological tradeoff, we showed that the 31P relaxation behavior in the living brain can be mimicked by solutions of ATP in the presence of Mg and agarose alone and of PCr and Pi with additional Gd, all suitable for external calibration.

Footnotes

This work was supported by by Forschungszentrum Jülich. Investigations were performed at the laboratories of Forschungszentrum Jülich.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Agren H, Niklasson F (1988) Creatinine and creatine in CSF: indices of brain energy metabolism in depression. Short note. J Neural Transm 74:55–59. 10.1007/BF01243575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badzakova-Trajkov G, Häberling IS, Roberts RP, Corballis MC (2010) Cerebral asymmetries: complementary and independent processes. PloS One 5:e9682. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B 57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW. (2008) Noradrenergic modulation of arousal. Brain Res Rev 58:1–17. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blenman R, Port J, Felmlee J (2006) In vivo measurement of T1 relaxation times of 31P metabolites in human brain at 3T. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med 14:3098. [Google Scholar]

- Borbély AA, Daan S, Wirz-Justice A, Deboer T (2016) The two-process model of sleep regulation: A reapprisal. J Sleep Res 25:131–143. 10.1111/jsr.12371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun AR, Balkin TJ, Wesensten NJ, Carson RE, Varga M, Baldwin P, Selbie S, Belenky G, Herscovitch P (1997) Regional cerebral blood flow throughout the sleep–wake cycle. an H215O PET study. Brain 120:1173–1197. 10.1093/brain/120.7.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Basheer R, McKenna JT, Strecker RE, McCarley RW (2012) Control of sleep and wakefulness. Physiol Rev 92:1087–1187. 10.1152/physrev.00032.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchli R, Duc CO, Martin E, Boesiger P (1994) Assessment of absolute metabolite concentrations in human tissue by 31P MRS in vivo. Part I: Cerebrum, cerebellum, cerebral gray and white matter. Magn Reson Med 32:447–452. 10.1002/mrm.1910320404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess HJ, Kleiman J, Trinder J (1999) Cardiac activity during sleep onset. Psychophysiology 36:298–306. 10.1017/S0048577299980198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Nofzinger EA, Germain A, Meltzer CC, Wood A, Ombao H, Kupfer DJ, Moore RY (2004) Regional brain glucose metabolism during morning and evening wakefulness in humans. Sleep 27:1245–1254. 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande M, Bertini M (2008) Night-time right hemisphere superiority and daytime left hemisphere superiority: a repatterning of laterality across wake–sleep–wake states. Biol Psychol 77:337–342. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SM, Burt CT (1977) 31P nuclear magnetic relaxation studies of phosphocreatine in intact muscle: determination of intracellular free magnesium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 74:4271–4275. 10.1073/pnas.74.10.4271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crank J. (1976) The mathematics of diffusion. 2nd ed London: Oxford UP. [Google Scholar]

- Devilbiss DM, Page ME, Waterhouse BD (2006) Locus ceruleus regulates sensory encoding by neurons and networks in waking animals. J Neurosci 26:9860–9872. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1776-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijk DJ, Beersma DG, Daan S (1987) EEG power density during nap sleep: reflection of an hourglass measuring the duration of prior wakefulness. J Biol Rhythms 2:207–219. 10.1177/074873048700200304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du F, Zhu XH, Qiao H, Zhang X, Chen W (2007) Efficient in vivo 31P magnetization transfer approach for noninvasively determining multiple kinetic parameters and metabolic fluxes of ATP metabolism in the human brain. Magn Reson Med 57:103–114. 10.1002/mrm.21107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworak M, McCarley RW, Kim T, Kalinchuk AV, Basheer R (2010) Sleep and brain energy levels: ATP changes during sleep. J Neurosci 30:9007–9016. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1423-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworak M, McCarley RW, Kim T, Kalinchuk AV, Basheer R (2011) Replies to commentaries on ATP changes during sleep. Sleep 34:841–843. 10.5665/SLEEP.1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworak M, Kim T, McCarley RW, Basheer R (2017) Creatine supplementation reduces sleep need and homeostatic sleep pressure in rats. J Sleep Res 26:377–385. 10.1111/jsr.12523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmenhorst D, Elmenhorst EM, Hennecke E, Kroll T, Matusch A, Aeschbach D, Bauer A (2017) Recovery sleep after extended wakefulness restores elevated A1 adenosine receptor availability in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:4243–4248. 10.1073/pnas.1614677114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evelhoch JL, Ewy CS, Siegfried BA, Ackerman JJ, Rice DW, Briggs RW (1985) 31P spin-lattice relaxation times and resonance linewidths of rat tissue in vivo: dependence upon the static magnetic field strength. Magn Reson Med 2:410–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabr RE, El-Sharkawy AM, Schär M, Weiss RG, Bottomley PA (2011) High-energy phosphate transfer in human muscle: diffusion of phosphocreatine. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 301:C234–C241. 10.1152/ajpcell.00500.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilboe DD, Kintner DB, Anderson ME, Fitzpatrick JH Jr (1998) NMR-based identification of intra- and extracellular compartments of the brain Pi peak. J Neurochem 71:2542–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness RA, Coade SB, Webster AD (1984) ATP, ADP and AMP in plasma from peripheral venous blood. Clin Chim Acta 143:91–98. 10.1016/0009-8981(84)90216-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heipertz R, Eickhoff K, Karstens KH (1979) Cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of magnesium and inorganic phosphate in epilepsy. J Neurol Sci 41:55–60. 10.1016/0022-510X(79)90139-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington HP, Spencer DD, Vaughan JT, Pan JW (2001) Quantitative 31P spectroscopic imaging of human brain at 4 tesla: assessment of gray and white matter differences of phosphocreatine and ATP. Magn Reson Med 45:46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. (1979) A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat 6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Coman D, Herman P, Rao JU, Maritim S, Hyder F (2016) Towards longitudinal mapping of extracellular pH in gliomas. NMR Biomed 29:1364–1372. 10.1002/nbm.3578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen JE, Drost DJ, Menson RS, Williamson PC (2002) In vivo brain 31P-MRS: measuring the phospholipid resonances at 4 tesla from small voxels. NMR Biomed 15:338–347. 10.1002/nbm.776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan HE, Klomp DW, Wong CS, Boer VO, Webb AG, Luijten PR, Jeneson JA (2010) In vivo 31P MRS detection of an alcaline inorganic phosphate pool with short T1 in human resting skeletal muscle. NMR Biomed 23:995–1000. 10.1002/nbm.1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Shioiri T, Murashita J, Hamakawa H, Inubushi T, Takahashi S (1994) Phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy and ventricular enlargement in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res 55:41–50. 10.1016/0925-4927(94)90010-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Liu Y, MacLeod KM (2009) Regulation of muscle creatine kinase by phosphorylation in normal and diabetic hearts. Cell Mol Life Sci 66:135–144. 10.1007/s00018-008-8575-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu A, Atkinson IC, Zhou XJ, Thulborn KR (2013) PCr/ATP ratio mapping of the human head by simultaneously imaging of multiple spectral peaks with InterLeaved excitations and flexible twisted projection imaging readout trajectories (SIMPLE-TPI) at 9.4 tesla. Magn Reson Med 69:538–544. 10.1002/mrm.24281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Zhu XH, Zhang Y, Chen W (2014a) Intracellular redox state revealed by in vivo 31P MRS measurement of NAD+ and NADH contents in brains. Magn Reson Med 71:1959–1972. 10.1002/mrm.24859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Chen W, Zhu XH (2014b) Field dependance study of in vivo brain 31P MRS up to 16.4 T. NMR Biomed 27:1135–1141. 10.1002/nbm.3167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby-Phelps K. (2000) Cytoarchitecture and physical properties of cytoplasm: volume, viscosity, diffusion, intracellular surface area. Int Rev Cytol 192:189–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüthi A. (2014) Sleep spindles: where they come from, what they do. Neuroscientist 20:243–256. 10.1177/1073858413500854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyoo IK, Kong SW, Sung SM, Hirashima F, Parow A, Hennen J, Cohen BM, Renshaw PF (2003) Multinuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of high-energy phosphate metabolites in human brain following oral supplementation of creatine-monohydrate. Psychiatry Res: Neuroimaging 123:87–100. 10.1016/S0925-4927(03)00046-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maquet P, Dive D, Salmon E, Sadzot B, Franco G, Poirrier R, von Frenckell R, Franck G (1990) Cerebral glucose utilization during sleep–wake cycle in man determined by positron emission tomography and [18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose method. Brain Res 513:136–143. 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91099-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maquet P, Degueldre C, Delfiore G, Aerts J, Péters JM, Luxen A, Franck G (1997) Functional neuroanatomy of human slow-wave sleep. J Neurosci 17:2807–2812. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02807.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek T, Fafrowicz M, Golonka K, Mojsa-Kaja J, Oginska H, Tucholska K, Urbanik A, Beldzik E, Domagalik A (2010) Diurnal patterns of activity of the orienting and executive attention neural networks in subjects performing a stroop-like task: a functional magnetic imaging study. Chronobiol Int 27:945–958. 10.3109/07420528.2010.489400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall I, Higinbotham J, Bruce S, Freise A (1997) Use of Voigt lineshape for quantification of in vivo 1H spectra. Magn Reson Med 37:651–657. 10.1002/mrm.1910370504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur-De Vré R, Maerschalk C, Delporte C (1990) Spin-lattice relaxation times and nuclear overhauser enhancement effect for 31P metabolites in model solutions at two frequencies: implications for in vivo spectroscopy. Magn Reson Imaging 8:691–698. 10.1016/0730-725X(90)90003-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA. (2002) Cortical and subcortical generators of normal and abnormal rhythmicity. Int Rev Neurobiol 49:99–114. 10.1016/S0074-7742(02)49009-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo FM, Ballard HJ (2001) The effect of systemic hypoxia on interstitial and blood adenosine, AMP, ADP and ATP in dog skeletal muscle. J Physiol 536:593–603. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0593c.xd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musch TI, Pelligrino A, Dempsey JA (1980) Effects of prolonged N2O and barbiturate anesthesia on brain metabolism and pH in the dog. Respir Physiol 39:121–131. 10.1016/0034-5687(80)90040-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (1996) Data plot reference manual. pp. 66–67. Gaithersburg, MD: U.S. Department of Commerce; Available at: an2/homepagehtm. [Google Scholar]

- Nioka S, Chance B, Lockard SB, Dobson GP (1991) Quantitation of high energy phosphate compounds and metabolic significance in the developing dog brain. Neurol Res 13:33–38. 10.1080/01616412.1991.11739962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nir Y, Staba R, Andrillon T, Vyazovskiy W, Cirelli C, Fried I, Tononi G (2011) regional slow waves and spindles in human sleep. Neuron 70:153–169. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak J, Wilson M, MacPherson L, Arvanitis TN, Davies NP, Peet AC (2014) Clinical protocols for 31P MRS of the brain and their use in evaluating optic pathway gliomas in children. Eur J Radiol 83:e106–112. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oke A, Keller R, Mefford I, Adams RN (1978) Lateralization of norepinephrine in human thalamus. Science 200:1411–1413. 10.1126/science.663623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. (1971) The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9:97–113. 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroff OA, Prichard JW, Behar KL, Rothman DL, Alger JR, Shulman R (1985) Cerebral intracellular pH by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neurology 35:1681–1688. 10.1212/WNL.35.12.1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plante DT, Trksak GH, Jensen JE, Penetar DM, Ravichandran C, Riedner BA, Tartarini WL, Tartarini WL, Dorsey CM, Renshaw PF, Lukas SE, Harper DG (2014) Gray matter-specific changes in brain bioenergetics after acute sleep deprivation: a 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy study at 4 tesla. Sleep 37:1919–1927. 10.5665/sleep.4242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porkka-Heiskanen T, Kalinchuk AV (2011) Adenosine, energy metabolism and sleep homeostasis. Sleep Med Rev 15:123–135. 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao R, Ennis K, Lubach GR, Lock EF, Georgieff MK, Coe CL (2018) Metabolomic analysis of CSF indicates brain metabolic impairment precedes hematological indices of anemia in the iron-deficient infant monkey. Nutr Neurosci 21:40–48. 10.1080/1028415X.2016.1217119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Sherry AD, Malloy CR (2015) 31P-MRS of healthy human brain: ATP synthesis, metabolite concentrations, pH and T1 relaxation times. NMR Biomed 28:1455–1462. 10.1002/nbm.3384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rial R, González J, Gené L, Akaârir M, Esteban S, Gamundí A, Barceló P, Nicolau C (2013) Asymmetric sleep in apneic human patients. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 304:R232–R237. 10.1152/ajpregu.00302.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon BJ, Dosenbach RA, Su Y, Vlassenko AG, Larson-Prior LJ, Nolan TS, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME (2013) Morning–evening variation in human brain metabolism and memory circuits. J Neurophysiol 109:1444–1456. 10.1152/jn.00651.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, McCormick DA, Sejnowski TJ (1993) Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain. Science 262:679–685. 10.1126/science.8235588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Sing H, Belenky G, Holcomb H, Mayberg H, Dannals R, Wagner H, Thorne D, Popp K, Rowland L, Welsh A, Balwinski S, Redmond D (2000) Neural basis of alertness and cognitive performance impairments during sleepiness 1: effects of 24 h of sleep deprivation on waking human regional brain activity. J Sleep Res 9:335–352. 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trksak GH, Bracken BK, Jensen JE, Plante DT, Penetar DM, Tartarini WL, Maywalt MA, Dorsey CM, Renshaw PF, Lukas SE (2013) Effects of sleep deprivation on brain bioenergetics, sleep and cognitive performance in cocaine-dependent individuals. ScientificWorldJournal 2013:947879. 10.1155/2013/947879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urrila AS, Hakkarainen A, Heikkinen S, Huhdankoski O, Kuusi T, Stenberg D, Häkkinen AM, Porkka-Heiskanen T, Lundbom N (2006) Preliminary findings of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in occipital cortex during sleep. Psychiatry Res 147:41–46. 10.1016/j.pscychres.2006.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallimann T, Wyss M, Brdiczka D, Nicolay K, Eppenberger HM (1992) Intracellular compartmentation, structure and function of creatine kinase isoenzymes in tissues with high and fluctuating energy demands: the ‘phosphocreatine circuit’ for cellular energy homeostasis. Biochem J 281:21–40. 10.1042/bj2810021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M, Reynolds G, Kauppinen RA, Arvanitis TN, Peet AC (2011) A constrained least-squares approach to the automated quantitation of in vivo 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy data. Magn Reson Med 65:1–12. 10.1002/mrm.22579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JC, Gillin JC, Buchsbaum MS, Hershey T, Hazlett E, Sicotte N, Bunney WE Jr (1991) The effect of sleep deprivation on cerebral glucose metabolic rate in normal humans assessed with positron emission tomography. Sleep 14:155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JC, Gillin JC, Buchsbaum MS, Chen P, Keator DB, Khosla Wu N, Darnall LA, Fallon JH, Bunney WE (2006) Frontal lobe metabolic decreases with sleep deprivation not totally reversed by recovery sleep. Neuropsychopharmacology 31:2783–2792. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemaityte D, Varoneckas G, Plauska K, Kaukenas J (1986) Components of the heart rhythm power spectrum in wakefulness and individual sleep stages. Int J Psychophysiol 4:129–141. 10.1016/0167-8760(86)90006-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]