A novel series of 2-pyrazoline derivatives were designed, synthesized, and evaluated for cholinesterase (ChE) inhibitory, Aβ anti-aggregating and neuroprotective activities.

A novel series of 2-pyrazoline derivatives were designed, synthesized, and evaluated for cholinesterase (ChE) inhibitory, Aβ anti-aggregating and neuroprotective activities.

Abstract

A novel series of 2-pyrazoline derivatives were designed, synthesized, and evaluated for cholinesterase (ChE) inhibitory, Aβ anti-aggregating and neuroprotective activities. Among these, 3d, 3e, 3g, and 3h were established as the most potent and selective BChE inhibitors (IC50 = 0.5–3.9 μM), while 3f presented dual inhibitory activity against BChE and AChE (IC50 = 6.0 and 6.5 μM, respectively). Kinetic analyses revealed that 3g is a partial noncompetitive inhibitor of BChE (Ki = 2.22 μM), while 3f exerts competitive inhibition on AChE (Ki = 0.63 μM). The active compounds were subsequently screened for further assessments. 3f, 3g and 3h reduced Aβ1–42 aggregation levels significantly (72.6, 83.4 and 63.4%, respectively). In addition, 3f demonstrated outstanding neuroprotective effects against Aβ1–42-induced and H2O2-induced cell toxicity (95.6 and 93.6%, respectively). Molecular docking studies were performed with 3g and 3f to investigate binding interactions inside the active sites of BChE and AChE. Compounds 3g and 3f might have the multifunctional potential for use against Alzheimer's disease.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is an irreversible brain disorder. The first signs of AD are memory loss and behavior change followed by declining cognition, language, and ability to perform activities of daily living. The accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau slowly impairs brain structure and function. The progression of AD remains irreversible, even though much research has been carried out since the 1980s.1 Discovery of decreased cholinergic transmission, accumulated Aβ, and increased inflammation in AD patients has guided researchers to search for a compound capable of affecting multiple targets.2–4 Acetylcholine (ACh) is a cholinergic neurotransmitter that is predominantly hydrolyzed by acetylcholinesterase (AChE). In AD patients, ACh levels are depleted due to altered activities of cholinesterase. AChE is the main enzyme responsible for regulating cholinergic transmission. AChE activity is unchanged or declines in AD patients.5 Conversely, butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) is a pseudocholinesterase enzyme; its function in the brain was neglected until increased BChE activity was discovered in AD patients.5 In addition to their catalytic activity, cholinesterase enzymes have notable noncatalytic functions and contribute to amyloid aggregation, making them targets for drug design in AD.6,7

The formation of Aβ plaques is a hallmark of AD, which triggers the formation of neurofibrillary tangles, inflammation, and eventually cell death. Experimentally, Aβ deposits are targeted by means of aggregation inhibitors and immunotherapeutics.8,9 In addition, Aβ peptides are reported to exert toxicity due to generation of cellular hydrogen peroxide.10,11

4,5-Dihydro-1H-pyrazole or a 2-pyrazoline ring is a cyclic hydrazine moiety and a nitrogen-containing five-membered heterocyclic compound with important biological activities.12 Modifications of the pyrazoline ring on carbon (C3, C4, and C5) or nitrogen (N1 and N2) expanded the spectrum of pharmacological activity, leading to anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anti-amoebic, and antiprotozoal activities.13–18 A number of pyrazoline analogues have been identified or developed to target neurological disorders such as AD, depression, and Parkinson's disease.19–23 In addition, some 3,5-diarylpyrazolines with ChE inhibitory activity in the nanomolar range have been claimed as good candidates for treatment of AD in the literature.21,24–27

The complexity of AD and the lack of effective treatment for this disease prompted us to search for a multi-target directed ligand combining crucial features, such as ChE inhibitory, Aβ anti-aggregating, and neuroprotective activities. For this purpose, a series of 2-pyrazolines were synthesized and their inhibitory activity towards ChE was investigated. The active derivatives were also evaluated for their Aβ anti-aggregating activity and neuroprotective properties.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

The title compounds 3a–k were synthesized via the pathway shown in Scheme 1. The starting compounds, 4-substituted benzaldehydes (1a–i), were gained by the reaction of 4-fluorobenzaldehyde with appropriate amines using the same method as previously reported.28 Claisen–Schmidt condensation between 1a–i and substituted acetophenones in the presence of NaOH afforded the corresponding chalcone derivatives (2a–k). The cyclization of these chalcones with hydrazine hydrate in glacial acetic acid afforded pyrazoline derivatives (3a–k) with a yield of 45–94%. The structures of the synthesized compounds were deduced using spectroscopic techniques, such as IR, 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, mass, and elemental analysis.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of target compounds. Reagents and conditions: (i) appropriate acetophenone, 20% aq. NaOH, EtOH, 5 °C, 2 h, (ii) NH2NH2·H2O, CH3COOH, 4 h, refluxed.

In the IR spectra of 3a–k, the sharp absorption bands around 1657–1632 and 1604–1616 cm–1 were assigned to the stretching of C O and C N, respectively. The proton NMR spectra of the target compounds showed an ABX system attributed to one single proton Hx (C-5) and two diastereotopic protons, Ha and Hb (C-4), of the pyrazoline ring. The protons Ha and Hb at C-4 showed two doublets of doublets in the region 3.07–3.36 and 3.73–3.86 ppm, respectively. The Hx proton, which is vicinal to methylene protons, resonated as a doublet of doublets in the region 5.39–5.60 ppm. The methyl protons of the acetyl group were observed around 2.23–2.32 ppm as a singlet. In the 13C NMR spectra, three characteristic signals were observed for C3, C4 and C5 of the pyrazoline moiety at values of approximately 154, 42 and 58 ppm, respectively. The signals at around 167 ppm also confirmed the acetyl group in the structure. In the ESI-MS spectra of pyrazolines, the [M + H]+ and [M + Na]+ molecular ion peaks for each compound were observed at their respective masses. Results of elemental analyses (CHN) were in agreement with the suggested chemical structures of the synthesized compounds.

Biological activity

ChE inhibitory activity

As seen in Table 1, most of the compounds showed selective inhibitory activity against BChE over AChE. 3f was an exception with IC50 values of 6.0 and 6.5 μM for BChE and AChE, respectively.

Table 1. ChE inhibitory activities of 2-pyrazolines 3a–k.

| |||||||||

| Compound | R1 | R2 | tPSA a | log P a | MW | H-Bond acc./don. | IC50

b

(μM) ± SE |

Selectivity for BChE c | |

| BChE | AChE | ||||||||

| 3a | OCH3 |

|

81.84 | 1.89 | 391.43 | 6/0 | 27.5 ± 0.5 | 955.3 ± 0.2 | 34.8 |

| 3b | OCH3 |

|

68.95 | 3.15 | 390.44 | 5/0 | 32.7 ± 0.1 | 205.6 ± 0.1 | 6.3 |

| 3c | OCH3 |

|

68.95 | 4.79 | 440.50 | 5/0 | 254.2 ± 0.1 | 319.2 ± 0.2 | 1.2 |

| 3d | OCH3 |

|

57.61 | 4.59 | 498.62 | 5/0 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 62.8 ± 0.1 | 128.1 |

| 3e | OCH3 |

|

54.37 | 5.98 | 497.63 | 4/0 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 20.1 ± 0.1 | 9.8 |

| 3f | OCH3 |

|

57.61 | 2.81 | 422.52 | 5/0 | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 6.5 ± 0.1 | 1.1 |

| 3g | OCH3 |

|

57.61 | 3.15 | 436.55 | 5/0 | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 47.9 ± 0.1 | 104.1 |

| 3h | OCH3 |

|

54.37 | 4.61 | 421.54 | 4/0 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 77.4 ± 0.1 | 19.9 |

| 3i | OCH3 |

|

57.61 | 4.46 | 484.60 | 4/0 | 1902 ± 0.1 | 294.9 ± 0.0 | 0.2 |

| 3j | H |

|

48.38 | 4.85 | 468.60 | 4/0 | 137.3 ± 0.1 | 100.2 ± 0.1 | 0.7 |

| 3k | H |

|

48.38 | 3.41 | 406.53 | 4/0 | 216.7 ± 0.1 | 221.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 |

| Donepezil | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 6.2 ± 1.0 d | |||||||

atPSA and log P calculated using Molecular Operating Environment, Chemical Computing Group (MOE) 2018.0101.

bIC50 values of compounds represent the concentration that caused a 50% reduction in enzyme activity.

cSelectivity for BChE is defined as IC50(AChE)/IC50(BChE).

dIC50 (nM) ± SE.

Regarding BChE inhibitory activity, 3g, carrying a 4-ethylpiperazine moiety on the phenyl at the fifth position of the pyrazoline ring, was found to be the most potent agent with an IC50 = 0.5 μM. 3d containing a 4-benzylpiperazine moiety induced a similar BChEi activity (IC50 = 0.5 μM) to 3g. Changing 4-ethylpiperazine to 4-methylpiperazine resulted in a brief reduction in BChEi activity of 3f with an IC50 = 6.0 μM.

However, the presence of 4-phenylpiperazine (3i, IC50 = 1902 μM) instead of 4-ethylpiperazine reduced the inhibitory activity towards BChE. Compounds carrying alkyl-substituted piperazine, such as methyl, ethyl, and benzyl, induced better BChEi activity than those with phenyl-substituted piperazine. Moreover, when the substituent at the piperazine ring is an alkyl group (3g, SI = 104.1 and 3d, SI = 128.1) bulkier than methyl (3f, SI = 1.1), the selectivity to BChE significantly increased.

Notably, compounds 3e and 3h (IC50 = 2.1 and 3.9 μM) possessing benzyl- and methylpiperidin moieties, respectively, demonstrated similar activity to their counterparts 3d and 3f, which have piperazine substituents. Reducing the number of methoxy groups on the phenyl at the third position of the pyrazoline ring lowered the inhibitory activity of compounds 3j and 3k with an IC50 = 137.3 and 216 μM, respectively. Also, replacement of the piperazine moiety with azole rings reduced the inhibitory activity of compounds 3a, 3b, and 3c with IC50 = 22.5–254.2 μM.

Based on the IC50 values, the modes of inhibition of 3g on BChE and 3f on AChE were characterized by Dixon and slope replot analyses (Fig. 1). The inhibition mechanism of 3g on BChE was found to be of the partial non-competitive type with Ki = 2.22 ± 0.82 (Fig. 1A). This finding showed that compound 3g may bind not only with the free enzyme, but also with the enzyme–substrate complex. Detailed kinetic evaluation revealed that 3g decreased Vmax (β = 0.11, coefficient of noncompetitive interaction) without producing a significant change in the value of Km (α = 1.38, coefficient of competitive interaction). 3f was found to be a competitive inhibitor of AChE with Ki = 0.63 ± 0.09 μM (Fig. 1B). This model suggested that compound 3f may bind with the catalytic site thus preventing the formation of the enzyme–substrate complex.

Fig. 1. Dixon plot for A) partial noncompetitive inhibition of BChE by 3g, Dixon plot and slope replot for B) competitive inhibition of AChE by 3f, Dixon plot and slope replot, r2 values for the trendlines >0.90.

Inhibition of self-mediated Aβ1–42 aggregation

The selected compounds (IC50 ≤6 μM for ChE, 3d, 3e, 3f, 3g, and 3h) were examined for their Aβ anti-aggregating activity and neuroprotective properties. The results are summarized in Table 2. A thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence assay was performed to assess the inhibitory effects of the compounds on self-mediated Aβ1–42 aggregation using rifampicin and donepezil as the standard. Although the compounds were not as active as rifampicin at 100 μM, 3f, 3g and 3h caused significantly lower aggregation. Further studies revealed that the compounds showed moderate ability for inhibition of self-mediated Aβ1–42 aggregation at 10 μM, especially 3e and 3h (82.2 and 80.6%, respectively, see data in the ESI†).

Table 2. In vitro effects on self-mediated Aβ1–42 aggregation, cytotoxicity, and Aβ1–42- and H2O2-induced cytotoxicity.

| Comp. | Aβ1–42 aggregation (%) ± SEM | Cytotoxicity (% cell viability) ± SEM | Aβ1–42-Induced cytotoxicity (% cell viability) ± SEM | H2O2-Induced cytotoxicity (% cell viability) ± SEM |

| 3d | 89.8 ± 8.0 | 93.3 ± 3.3 | 69.3 ± 2.3 | 87.0 ± 2.8 |

| 3e | 86.4 ± 7.0 | 100.6 ± 1.3 | 83.5 ± 2.0 | 84.4 ± 2.1 |

| 3f | 72.6 ± 0.8* | 93.3 ± 14.2 | 95.6 ± 2.6*** | 93.6 ± 2.5* |

| 3g | 83.4 ± 0.9* | 89.2 ± 4.6 | 67.9 ± 2.3 | 87.4 ± 4.7 |

| 3h | 63.4 ± 1.3* | 95.4 ± 4.3 | 78.4 ± 3.4 | 81.1 ± 3.3 |

| Control a | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Rifampicin | 48.4 ± 0.3* | — | — | — |

| Donepezil | 83.4 ± 0.1* | — | 62.5 ± 0.5 | 69.0 ± 4.4 |

| Amyloid (10 μM) | — | — | 78.0 ± 1.0 | — |

| H2O2 (250 μM) | — | — | — | 75.2 ± 4.6 |

aFor each assay, the control was a non-treated sample.

Cytotoxicity

The cytotoxicity of five compounds (3d, 3e, 3f, 3g, and 3h) at 10 μM on the healthy cell line L929 was determined by the MTT assay (Table 2). The results suggested that the compounds have a negligible effect on cell viability (statistically insignificant).

Neuroprotection

The neuroprotective effects of the compounds (3d, 3e, 3f, 3g, and 3h) against Aβ1–42- and H2O2-induced cell death were evaluated in SH-SY5Y cells using the MTT assay (Table 2). The results revealed that 3f was the most protective compound with 95.6 and 93.6% cell viability against Aβ1–42-induced and H2O2-induced cell toxicity, respectively.

Molecular modeling

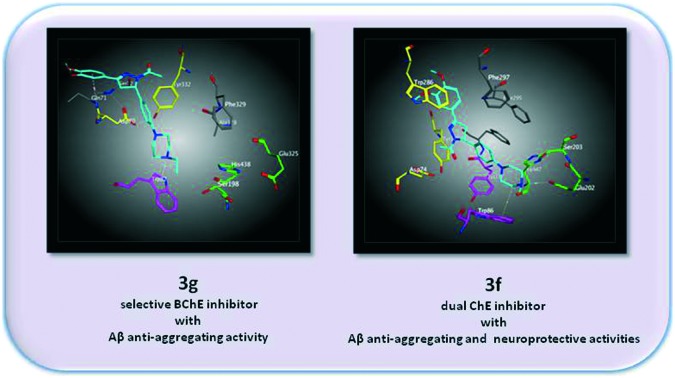

Lipinski's rule of five states that most “drug-like” molecules have a log P ≤ 5, molecular weight ≤500, number of hydrogen bond acceptors ≤10, and number of hydrogen bond donors ≤5. It was encouraging to note that all the compounds complied with all Lipinski parameters (Table 1). In addition, compounds with higher polar surface areas (tPSAs) have lower CNS permeability, and a tPSA less than 90 Å2 indicates that a compound is able to penetrate the blood brain barrier (BBB).29 Based on their predicted tPSA values (between 48.38 and 81.84 Å2), the derivatives were assumed to penetrate the BBB. Molecular docking studies were performed for 3g (the most potent and selective BChE inhibitor) and 3f (a dual inhibitor) to investigate their possible binding modes in BChE and AChE. The docking result of 3g in BChE showed that the ethylpiperazine moiety fit into the anionic site and established π–cation interactions with Trp82. Additionally, the phenyl moiety located closely at peripheral site residues Asp 70 and Tyr 332. Interestingly, 3g does not directly interact with the catalytic triad of BChE (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. (A) Representation of the binding mode of 3g in the BChE active site. (B) Representation of the binding mode of 3f in the BChE active site. The catalytic triad (Ser198, His438, and Glu325) is shown in green, the anionic site residue Trp82 is shown in purple, and the peripheral anionic site (Tyr332 and Asp70) is shown in yellow.

In accordance with kinetic studies, this orientation of 3g in the BChE active site may cause reduction of substrate hydrolysis (Fig. 1A). Although 3f was located in a similar position to 3g, hydrophobic interactions in the anionic site may be decreased by methyl substitution instead of ethyl. The docking result of 3f in AChE showed that the methylpiperazine group of 3f formed ionic interaction with catalytic site residue Glu202, which may prevent substrate binding. This finding is also supported with the competitive mechanism of 3f revealed by kinetic studies (Fig. 1B). Additionally, the methylpiperazine moiety of 3f established hydrophobic interactions with Trp86 which results in tight fitting into the active site gorge of AChE (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. (A) Representation of the binding mode of 3f (blue) in the AChE active site. The catalytic triad (Ser203, His447, and Glu202) is shown in green, the anionic site (Trp86 and Tyr337) is shown in purple, and the peripheral anionic site (Trp286, Asp74 and Tyr341) is shown in yellow. (B) 2D interaction between 3f and residues of the AChE active site.

Conclusion

Although current treatment of AD is based on AChE inhibitors and an N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) blocker, their effects remain debated. Many factors, such as low ACh levels, Aβ aggregation, tau protein phosphorylation, and increased oxidative stress, seem to overlap in the pathology of AD. Therefore, it is believed that a multifactorial approach could provide hope in this field. For this purpose, a novel series of 2-pyrazoline derivatives were designed, synthesized, and evaluated for their ChE inhibitory, Aβ anti-aggregating, and neuroprotective activities. Among them, 3d, 3e, 3g, and 3h were established as the most potent and selective inhibitors of BChE (IC50 = 0.5, 2.1, 0.5, and 3.9 μM, SI = 128.1, 9.8, 104.1, and 19.9, respectively), while 3f showed dual inhibitory activity against BChE and AChE (IC50 = 6.0 and 6.5 μM, respectively). The compounds with an inhibitory effect on ChE were subsequently screened for their Aβ anti-aggregating and neuroprotective activities. 3f, 3g and 3h induced lower levels of Aβ1–42 aggregation (72.6, 83.4 and 63.4%). In addition, 3f increased the viability of Aβ1–42 and H2O2 treated SH-SY5Y cells significantly (95.6 and 93.6%, respectively). Recent findings suggested that BChE activity is increased while AChE activity is reduced in AD brain and thus, BChE-selective inhibitors might provide greater benefit in AD treatment.30,31 Nevertheless, since the levels of ChEs vary across the clinical course of AD, dual inhibitors remain important in the treatment of AD.32,33 Therefore, 3g, which is a highly potent and selective BChE inhibitor with Aβ anti-aggregating activity, and 3f, which has dual ChE inhibitory activity with Aβ anti-aggregating and neuroprotective effects, might be potential lead compounds for further development of treatment for AD.

Experimental

Chemistry

Melting points were determined with a Thomas Hoover capillary melting point apparatus (Thomas Scientific, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and were not corrected. Attenuated total reflection (ATR) Fourier transform IR (FTIR) spectra were obtained using a MIRacle ATR accessory (Pike Technologies, Fitchburg, WI, USA) in conjunction with a Spectrum BX FTIR spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, USA) and were reported in cm–1. 1H (400 MHz) and 13C NMR (100 MHz) spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury 400 FT NMR spectrophotometer using tetramethylsilane as an internal reference (chemical shift presented in δ ppm). ESI-MS spectra were measured on a micromass ZQ-4000 single-quadruple mass spectrometer. Elemental analyses (C, H, and N) were performed on a Leco CHNS 932 analyzer (Leco, St. Joseph, MI, USA).

General procedure for the preparation of chalcone derivatives (2a–k)

An aqueous NaOH solution (20%) was added dropwise to a solution of 10 mmol 4-substituted benzaldehyde 1a–i and an appropriate acetophenone (10 mmol) in ethanol (20 mL) at 5 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The obtained precipitate was filtered and washed with cold ethanol. The crude product was used for the next step without further purification.

General procedure for the preparation of 2-pyrazoline derivatives (3a–k)

Hydrazine hydrate (4 mmol, 0.2 mL) was added to a solution of the corresponding chalcone derivative (1 mmol) in acetic acid (5 mL). The reaction mixture was refluxed under stirring for 4 h, poured into an ice–water mixture, and then neutralized with a saturated NaHCO3 solution. The precipitate was filtered, dried, and crystallized from ethanol.

1-(5-(4-(1H-1,2,4-Triazol-1-yl)phenyl)-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (3a)

Yield 84%; mp. 210–2 °C. IR; 3106, 3007, 2939, 2838, 1632, 1604, 1518, 1463, 1434, 1414, 1324, 1263, 1242 cm–1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 9.25 (1H; s; triazole), 8.22 (1H; s; triazole), 7.80 (2H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.4 Hz), 7.38–7.36 (3H; m; Ar–H), 7.30 (1H; dd; Ar–H; J: 8.4 Hz; J: 2.0 Hz), 7.02 (1H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.4 Hz), 5.60 (1H; dd; Hx; Jxa: 4.8 Hz; Jxb: 11.6 Hz), 3.86 (1H; dd; Hb; Jba: 18.0 Hz; Jbx: 11.6 Hz), 3.82 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.80 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.20 (1H; dd; Ha; Jab: 18.0 Hz; Jax: 4.8 Hz), 2.32 (3H; s; CH3) ppm. 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 167.18 (CO), 154.09 (C3 pyrazoline), 152.29, 150.77, 148.69, 142.19, 142.03, 135.67, 126.84, 123.51, 120.38, 119.75, 111.38, 109.07, 58.77 (C5 pyrazoline), 55.51 (OCH3), 55.44 (OCH3), 41.99 (C4 pyrazoline), 21.60 (CH3) ppm. ESI-MS (m/z); 414.15 [M + Na]+, 392.16 [M + H]+. Anal. calcd. for C21H21N5O3: C, 64.44; H, 5.41; N, 17.89. Found: C, 64.63; H, 5.09; N, 17.65.

1-(5-(4-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)phenyl)-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (3b)

Yield 71%; mp. 184–6 °C. IR; 3120, 2936, 2833, 1645, 1608, 1519, 1424, 1404, 1262, 1243 cm–1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 8.18 (1H; s; imidazole), 7.67 (1H; t; imidazole; J: 1.6 Hz), 7.56 (2H; dd; Ar–H; J: 8.8 Hz; J: 2.0 Hz), 7.35 (1H; d; Ar–H; J: 1.6 Hz), 7.29 (2H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.8 Hz), 7.26 (1H; d; Ar–H; J: 2.0 Hz), 7.07 (1H; s; imidazole), 7.00 (1H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.4 Hz), 5.56 (1H; dd; Hx; Jxa: 4.8 Hz; Jxb: 11.8 Hz), 3.82 (1H; dd; Hb; Jba: 18.0 Hz; Jbx: 11.6 Hz), 3.79 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.78 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.17 (1H; dd; Ha; Jab: 18.0 Hz; Jax: 4.0 Hz), 2.30 (3H; s; CH3) ppm. 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 167.14 (CO), 154.11 (C3 pyrazoline), 150.77, 148.69, 141.09, 135.83, 135.45, 129.73, 126.86, 123.52, 120.70, 120.37, 118.00, 111.38, 109.07, 58.72 (C5 pyrazoline), 55.51 (OCH3), 55.44 (OCH3), 41.99 (C4 pyrazoline), 21.60 (CH3) ppm. ESI-MS (m/z); 412.95 [M + Na]+, 390.97 [M + H]+. Anal. calcd. for C22H22N4O3: C, 67.68; H, 5.68; N, 14.35. Found: C, 67.64; H, 5.39; N, 14.60.

1-(5-(4-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)phenyl)-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (3c)

Yield 94%; mp. 156–8 °C. IR; 3512, 2963, 2837, 1642, 1605, 1514, 1454, 1416, 1262, 1237 cm–1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 8.51 (1H; s; benzimidazole), 7.76–7.74 (1H; m; benzimidazole), 7.63 (2H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.0 Hz), 7.59–7.57 (1H; m; benzimidazole), 7.41 (2H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.4 Hz), 7.37 (1H; d; Ar–H; J: 2.0 Hz), 7.31–7.27 (3H; m; benzimidazole and Ar–H), 7.01 (1H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.8 Hz), 5.63 (1H; dd; Hx; Jxa: 4.4 Hz; Jxb: 11.8 Hz), 3.86 (1H; dd; Hb; Jba: 18.2 Hz; Jbx: 11.6 Hz), 3.80 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.78 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.23 (1H; dd; Ha; Jab: 18.0 Hz; Jax: 4.4 Hz), 2.32 (3H; s; CH3) ppm. 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 167.21 (CO), 154.18 (C3 pyrazoline), 150.79, 148.71, 143.71, 143.16, 141.91, 134.82, 132.93, 127.07, 123.80, 123.52, 123.37, 122.34, 120.41, 119.86, 111.39, 110.54, 109.10, 58.80 (C5 pyrazoline), 55.52 (OCH3), 55.45 (OCH3), 42.06 (C4 pyrazoline), 21.63 (CH3) ppm. ESI-MS (m/z); 462.96 [M + Na]+, 440.98 [M + H]+. Anal. calcd. for C26H24N4O3: C, 70.89; H, 5.49; N, 12.72. Found: C, 70.48; H, 5.73; N, 12.55.

1-(5-(4-(4-Benzylpiperazin-1-yl)phenyl)-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (3d)

Yield 67%; mp. 74–6 °C. IR; 2935, 2819, 1657, 1611, 1515, 1406, 1263, 1243 cm–1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 7.33–7.23 (7H; m; Ar–H), 6.99 (3H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.8 Hz), 6.83 (2H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.8 Hz), 5.40 (1H; dd; Hx; Jxa: 4.0 Hz; Jxb: 11.0 Hz), 3.79 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.78 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.74 (1H; br; Hb), 3.49 (2H; s; CH2), 3.09–3.07 (5H; m; piperazine and Ha), 2.48 (4H; br; piperazine), 2.25 (3H; s; CH3) ppm. 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 166.85 (CO), 154.07 (C3 pyrazoline), 150.66, 150.10, 148.67, 137.94, 132.74, 128.79, 128.08, 126.85, 126.07, 123.72, 120.26, 115.38, 111.37, 109.99, 61.93, 58.68 (C5 pyrazoline), 55.49 (OCH3), 55.41 (OCH3), 52.40, 48.23, 42.01 (C4 pyrazoline), 21.64 (CH3) ppm. ESI-MS (m/z); 521.28 [M + Na]+, 499.28 [M + H]+. Anal. calcd. for C30H34N4O3: C, 72.26; H, 6.87; N, 11.24. Found: C, 72.62; H, 7.10; N, 11.36.

1-(5-(4-(4-Benzylpiperidin-1-yl)phenyl)-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (3e)

Yield 68%; mp. 146 °C. IR; 2926, 2838, 2806, 1650, 1609, 1515, 1440, 1404, 1261, 1241 cm–1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 7.35 (1H; d; Ar–H; J: 2.0 Hz), 7.29–7.26 (3H; m; Ar–H), 7.19–7.16 (3H; m; Ar–H), 7.02–6.97 (3H; m; Ar–H), 6.84 (2H; d; Ar–H; J: 9.2 Hz), 5.41 (1H; dd; Hx; Jxa: 4.4 Hz; Jxb: 11.6 Hz), 3.80 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.79 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.74 (1H; dd; Hb; Jba: 18.0 Hz; Jbx: 11.6 Hz), 3.60 (2H; brd; NCH2eq; J: 12.8 Hz), 3.10 (1H; dd; Ha; Jab: 17.8 Hz; Jax: 4.4 Hz), 2.57–2.53 (2H; m; NCH2ax and DMSO), 2.27 (3H; s; CH3), 1.63–1.60 (3H; m; NCH2CH[combining low line]2eq and CH), 1.23–1.20 (2H; m; NCH2CH[combining low line]2ax) ppm. ESI-MS (m/z); 520.05 [M + Na]+, 498.06 [M + H]+. Anal. calcd. for C31H35N3O3: C, 74.82; H, 7.09; N, 8.44. Found: C, 74.77; H, 7.21; N, 8.35.

1-(5-(4-(4-Methylpiperazin-1-yl)phenyl)-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (3f)

Yield 47%; mp. 143–5 °C. IR; 2932, 2835, 2791, 1648, 1610, 1514, 1437, 1411, 1265, 1238 cm–1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 7.33 (1H; d; Ar–H; J: 1.6 Hz), 7.25 (1H; dd; J: 8.4 Hz; J: 2.0 Hz), 6.98 (3H; dd; J: 8.4 Hz; J: 2.0 Hz), 6.84 (2H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.8 Hz), 5.40 (1H; dd; Hx; Jxa: 4.4 Hz; Jxb: 11.6 Hz), 3.78 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.77 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.73 (1H; dd; Hb; Jba: 18.2 Hz; Jbx: 11.6 Hz), 3.11–3.04 (5H; m; Ha ve NCH2), 2.41–2.38 (4H; t; NCH2; J: 4.4 Hz), 2.25 (3H; s; CH3), 2.18 (3H; s; NCH3) ppm.

13C-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 166.84 (CO), 154.06 (C3 pyrazoline), 150.66, 150.09, 148.68, 132.69, 126.07, 123.71, 120.26, 115.32, 111.36, 108.98, 58.67 (C5 pyrazoline), 55.49 (OCH3), 55.41 (OCH3), 54.47, 48.06, 45.64, 42.00 (C4 pyrazoline), 21.63 (CH3) ppm. ESI-MS (m/z); 445.01 [M + Na]+, 423.03 [M + H]+. Anal. calcd. for C24H30N4O3: C, 68.22; H, 7.16; N, 13.26. Found: C, 68.32; H, 7.45; N, 12.97.

1-(5-(4-(4-Ethylpiperazin-1-yl)phenyl)-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (3g)

Yield 61%; mp. 73–5 °C. IR; 2934, 2821, 1656, 1613, 1514, 1408, 1261, 1236 cm–1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 7.33 (1H; d; Ar–H; J: 1.6 Hz), 7.26 (1H; dd; J: 8.0 Hz; J: 2.0 Hz), 7.00–6.95 (3H; m; Ar–H), 6.84 (2H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.4 Hz), 5.40 (1H; dd; Hx; Jxa: 4.4 Hz; Jxb: 11.4 Hz), 3.78 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.77 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.73 (1H; dd; Hb; Jba: 18.2 Hz; Jbx: 11.4 Hz), 3.14 (1H; br; Ha), 3.06 (4H; t; NCH2; J: 4.4 Hz), 2.44 (4H; t; NCH2; J: 4.4 Hz), 2.35–2.30 (2H; q; CH2CH3; J: 7.2 Hz), 2.25 (3H; s; CH3), 0.99 (3H; t; CH2CH3; J: 7.6 Hz), ppm. 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 166.92 (CO), 154.14 (C3 pyrazoline), 150.75, 150.18, 148.75, 132.80, 126.15, 123.79, 120.33, 115.38, 111.43, 109.06, 58.76 (C5 pyrazoline), 55.57 (OCH3), 55.48 (OCH3), 52.22, 51.55, 48.19, 42.08 (C4 pyrazoline), 21.71 (CH3), 11.87 ppm. ESI-MS (m/z); 459.05 [M + Na]+, 437.07 [M + H]+. Anal. calcd. for C25H32N4O3: C, 68.78; H, 7.39; N, 12.83. Found: C, 68.99; H, 7.51; N, 12.79.

1-(5-(4-(4-Methylpiperidin-1-yl)phenyl)-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (3h)

Yield 45%; mp. 68–70 °C. IR; 2919, 1646, 1612, 1513, 1460, 1430, 1264, 1240 cm–1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 7.35 (1H; d; Ar–H; J: 2.0 Hz), 7.27 (1H; dd; J: 8.2 Hz; J: 2.0 Hz), 7.02–6.98 (3H; m; Ar–H), 6.85 (2H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.4 Hz), 5.41 (1H; dd; Hx; Jxa: 4.4 Hz; Jxb: 11.6 Hz), 3.81 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.80 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.75 (1H; dd; Hb; Jba: 18.0 Hz; Jbx: 11.6 Hz), 3.60 (2H; brd; NCH2eq; J: 12.4 Hz), 3.10 (1H; dd; Ha; Jab: 17.8 Hz; Jax: 4.4 Hz), 2.59 (2H; td; NCH2ax; J: 11.0/2.0 Hz), 2.27 (3H; s; CH3), 1.65 (2H; brd; NCH2CH2eq; J: 12.0 Hz), 1.48–1.45 (1H; m; CH), 1.24–1.17 (2H; qd; NCH2CH2ax; J: 12.0/3.2 Hz), 0.91 (3H; d; CH3; J: 6.0 Hz) ppm. 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 166.84 (CO), 154.08 (C3 pyrazoline), 150.66, 150.41, 148.68, 132.21, 126.07, 123.73, 120.25, 115.70, 111.36, 108.98, 58.68 (C5 pyrazoline), 55.50 (OCH3), 55.41 (OCH3), 48.85, 48.81, 42.00 (C4 pyrazoline), 33.37, 30.09, 21.67, 21.64 (CH3) ppm. ESI-MS (m/z); 444.05 [M + Na]+, 422.06 [M + H]+. Anal. calcd. for C25H31N3O3: C, 71.23; H, 7.41; N, 9.97. Found: C, 70.99; H, 7.57; N, 9.83.

1-(5-(4-(4-Phenylpiperazin-1-yl)phenyl)-3-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (3i)

Yield 48%; mp. 189–191 °C. IR; 2964, 2832, 1648, 1597, 1514, 1461, 1423, 1265, 1230 cm–1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 7.35 (1H; d; Ar–H; J: 1.2 Hz), 7.27 (1H; dd; J: 8.2 Hz; J: 2.0 Hz), 7.21 (2H; t; J: 8.4 Hz), 7.05–6.91 (7H; m; Ar–H), 6.78 (1H; t; J: 7.2 Hz), 5.43 (1H; dd; Hx; Jxa: 4.0 Hz; Jxb: 11.4 Hz), 3.80 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.79 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.74 (1H; dd; Hb; Jba: 18.0 Hz; Jbx: 11.2 Hz), 3.25–3.18 (8H; m; NCH2 and DMSO-D2O), 3.10 (1H; dd; Ha; Jab: 18.0 Hz; Jax: 4.0 Hz), 2.26 (3H; s; CH3) ppm. ESI-MS (m/z); 507.06 [M + Na]+, 485.08 [M + H]+. Anal. calcd. for C29H32N4O3: C, 71.88; H, 6.66; N, 11.56. Found: C, 72.01; H, 6.88; N, 11.82.

1-(5-(4-(4-Benzylpiperazin-1-yl)phenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (3j)

Yield 67%; mp. 67–9 °C. IR; 2937, 2817, 1656, 1608, 1515, 1409, 1248, 1229 cm–1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 7.69 (2H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.8 Hz), 7.31–7.23 (5H; m; Ar–H), 6.99 (4H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.8 Hz), 6.83 (2H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.4 Hz), 5.39 (1H; dd; Hx; Jxa: 4.0 Hz; Jxb: 11.8 Hz), 3.78 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.73 (1H; br; Hb), 3.49 (2H; s; CH2), 3.07–3.02 (5H; m; piperazine and Ha), 2,48 (4H; s; piperazine and DMSO), 2.23 (3H; s; CH3) ppm. 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 166.84 (CO), 160.77, 153.85 (C3 pyrazoline), 150.09, 137.95, 132.72, 128.79, 128.15, 128.08, 126.85, 126.11, 123.63, 115.37, 114.10, 61.94, 58.65 (C5 pyrazoline), 55.24 (OCH3), 52.41, 48.21, 41.97 (C4 pyrazoline), 21.65 (CH3) ppm. ESI-MS (m/z); 491.02 [M + Na]+, 469.04 [M + H]+. Anal. calcd. for C29H32N4O2: C, 74.33; H, 6.88; N, 11.96. Found: C, 74.71; H, 6.58; N, 11.59.

1-(5-(4-(4-Ethylpiperazin-1-yl)phenyl)-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)ethanone (3k)

Yield 58%; mp. 91–3 °C. IR; 2958, 2830, 1616, 1511, 1470, 1449, 1438, 1249 cm–1. 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 7.70 (2H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.8 Hz), 6.99 (4H; m; Ar–H), 6.84 (2H; d; Ar–H; J: 8.8 Hz), 5.39 (1H; dd; Hx; Jxa: 4.4 Hz; Jxb: 11.4 Hz), 3.78 (3H; s; OCH3), 3.74 (1H; br; Hb), 3.36 (1H; br; Ha and DMSO-D2O), 3.06 (4H; brt; piperazine), 2.40 (4H; brt; piperazine), 2.30–2.26 (2H; q; CH2CH3; J: 7.2 Hz), 2.23 (3H; s; CH3), 1.18 (3H; t; CH2CH3; J: 7.2 Hz), ppm. 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6); δ 167.01 (CO), 154.09 (C3 pyrazoline), 150.63, 148.65, 132.69, 128.90, 126.58, 123.99, 116.08, 114.82, 58.72 (C5 pyrazoline), 55.38 (OCH3), 54.49, 49.62, 47.98, 42.03 (C4 pyrazoline), 21.69 (CH3), 12.09 ppm. ESI-MS (m/z); 429.30 [M + Na]+, 407.33 [M + H]+. Anal. calcd. for C24H30N4O2: C, 70.91; H, 7.44; N, 13.78. Found: C, 70.95; H, 7.38; N, 14.16.

Biological activity

ChE inhibition assay

Human recombinant acetylcholinesterase (C1682), butyrylcholinesterase from equine serum (1057), acetylthiocholine iodide (A5751), and S-butyrylthiocholine iodide (B3253) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, and 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) was purchased from CALBIOCHEM (Los Angeles California, USA). Cholinesterase activity and kinetic assays were performed using Ellman's assay.34 Reactions were initiated by adding the enzyme to a medium containing the substrate (0.2–0.5 mM) and 0.125 mM DTNB at pH 8.0 (100 mM MOPS) and 25 °C; samples were monitored spectrophotometrically at 412 nm using a multimode plate reader (BMG Labtech Omega FLUOstar). Dixon plots (1/v versus I) were developed for four different concentrations of 3g and 3f (0.5, 1, 10, and 100 μM) and butyrylthiocholine/acetylthiocholine iodide was used as the substrate (0.2–0.5 mM). Dose–response curves, IC50, and Ki values were determined by Graphpad Prism 5 software. Donepezil HCl (D-6821, Sigma) was also tested as a reference agent.

ThT assay for Aβ1–42 aggregation

The inhibitory properties of the compounds on Aβ1–42 aggregation were determined using a thioflavin T (ThT)-based fluorescence assay.35 A commercially available Aβ1–42 protein fragment (A9810, Sigma Aldrich) was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4 and incubated at 37 °C for 72 h to induce peptide aggregation. Then, 100 μM inhibitor and 5 μM Aβ1–42 were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. The Aβ1–42–inhibitor mixture was added to ThT (200 μM) in 50 mM glycine–NaOH buffer, pH 8.0, and ThT excitation/emission was measured at 448/490 nm using a SpectraMax® microplate reader. Donepezil (100 μM, Sigma D-6821) was tested as a reference compound. Aβ1–42 percentage aggregation was determined by the following calculation: [(IFi/IFo) × 100], where IFi and IFo are the fluorescence intensities obtained for Aβ1–42 in the presence and absence of inhibitors.

MTT assay for cytotoxicity

To evaluate the cytotoxicity of five compounds (3d, 3e, 3f, 3g, and 3h) on the healthy cell line L929 (ATCC number CCL-1), the MTT assay was performed.36 L929 cells (5000 cells per well) were treated with 10 μM of each compound and then incubated for 24 hours. After incubation, 10 μL of MTT reagent (thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide, 5 mg mL–1) was added to each well. MTT formazan crystals were dissolved by the addition of 100 μL DMSO. The absorbance values at 690 and 570 nm were measured using a multimode plate reader (BMG Labtech Omega FLUOstar). Cell viability was determined as follows:

MTT assay for neuroprotective activity

To evaluate the neuroprotective effects of five compounds (3d, 3e, 3f, 3g, and 3h) against Aβ1–42- and H2O2-induced cytotoxicity, the MTT assay was performed.36 SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC number CRL-2266), (5000 cells per well) were treated with 10 μM of each compound for 3 h prior to 10 μM Aβ1–42 or 250 μM H2O2 treatment and then incubated for 24 hours. After incubation, 10 μL of MTT reagent (thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide, 5 mg mL–1) was added to each well. MTT formazan crystals were dissolved by the addition of 100 μL DMSO. The absorbance values at 690 and 570 nm were measured using a multimode plate reader (BMG Labtech Omega FLUOstar). Cell viability was determined as follows:

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software using one-way ANOVA analysis (Bonferroni's or Dunnett's test) or two tailed t-test compared to control values. p-Values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Molecular modeling studies

The clog P, tPSA, and docking studies were performed using MOE version 2018.0101 software, available from Chemical Computing Group Inc., 1010 Sherbrooke St. West, Suite 910, Montreal, Canada H3A 2R7, ; http://www.chemcomp.com.

The crystal structures of human BChE and AChE (PDB: 5NN0 (ref. 37) and ; 4EY7 (ref. 38)) were selected as target proteins because of their suitable resolution and co-crystallized ligands. All non-protein atoms and water molecules were removed from the enzymes. Errors were corrected by the “Structure Preparation” application. The ligands were constructed using the MOE builder tool and energy was minimized using the Merck Molecular Force Field (MMFF94x, gradient: 0.05 kcal mol–1 Å–1). Ligands were prepared for docking by considering their protonation state at pH 7.4. Docking studies were performed using the Triangle Matcher method. The results were ranked with the London dG scoring function and rescored with the GBVI/WSA dG scoring function. The poses with the lowest S score were selected for the enzymes.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Turkish Scientific Research Institution (TUBITAK, 114S374).

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c9md00030e

References

- Anderson R. M., Hadjichrysanthou C., Evans S., Wong M. M. Lancet. 2017;390:2327–2329. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32399-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batool A., Kamal M. A., Rizvi S. M. D., Rashid S. Curr. Drug Metab. 2018;19:704–713. doi: 10.2174/1389200219666180305152553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unzeta M., Esteban G., Bolea I., Fogel W. A., Ramsay R. R., Youdim M. B. H., Tipton K. F., Marco-Contelles J. Front. Neurosci. 2016;10:205. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni E., Bartolini M., Abu I. F., Blockley A., Gotti C., Bottegoni G., Caporaso R., Bergamini C., Andrisano V., Cavalli A., Mellor I. R., Minarini A., Rosini M. Future Med. Chem. 2017;9:953–963. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2017-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greig N. H., Lahiri D. K., Sambamurti K. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(Suppl 1):77–91. doi: 10.1017/s1041610203008676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini M., Bertucci C., Cavrini V., Andrisano V. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;65:407–416. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinamarca M. C., Sagal J. P., Quintanilla R. A., Godoy J. A., Arrázola M. S., Inestrosa N. C. Mol. Neurodegener. 2010;5:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpini E., Scheltens P., Feldman H. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:539–547. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00502-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ow S.-Y., Dunstan D. E. Protein Sci. 2014;23:1315–1331. doi: 10.1002/pro.2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Atwood C. S., Hartshorn M. A., Multhaup G., Goldstein L. E., Scarpa R. C., Cuajungco M. P., Gray D. N., Lim J., Moir R. D., Tanzi R. E., Bush A. I. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7609–7616. doi: 10.1021/bi990438f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behl C., Davis J. B., Lesley R., Schubert D. Cell. 1994;77:817–827. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alex J. M., Kumar R. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2014;29:427–442. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2013.795956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng-Cheng L., Dong-Dong L., Qing-Shan L., Xiang L., Zhu-Ping X., Hai-Liang Z. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:5374–5377. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bano S., Javed K., Ahmad S., Rathish I. G., Singh S., Alam M. S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:5763–5768. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui Z. N., Mohammed Musthafa T. N., Ahmad A., Khan A. U. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:2860–2865. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayat F., Salahuddin A., Umar S., Azam A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:4669–4675. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy M. V. R., Billa V. K., Pallela V. R., Mallireddigari M. R., Boominathan R., Gabriel J. L., Reddy E. P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:3907–3916. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Prada J., Robledo S. M., Vélez I. D., del Crespo M. P., Quiroga J., Abonia R., Montoya A., Svetaz L., Zacchino S., Insuasty B. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;131:237–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gökhan-Kelekçi N., Yabanoğlu S., Küpeli E., Salgın U., Özgen Ö., Uçar G., Yeşilada E., Kendi E., Yeşilada A., Bilgin A. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:5775–5786. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turan-Zitouni G., Hussein W., Saglik B. N., Baysal M., Kaplancikli Z. A. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery. 2018;15:414–427. [Google Scholar]

- Shah M. S., Khan S. U., Ejaz S. A., Afridi S., Rizvi S. U. F., Najam-ul-Haq M., Iqbal J. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;482:615–624. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawazura H., Takahashi Y., Shiga Y., Shimada F., Ohto N., Tamura A. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1997;73:317–324. doi: 10.1254/jjp.73.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karklin Fontana A. C., Fox D. P., Zoubroulis A., Valente Mortensen O., Raghupathi R. J. Neurotrauma. 2016;33:1073–1083. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.4079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra N., Sasmal D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:702–705. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.11.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chigurupati S., Selvaraj M., Mani V., Selvarajan K. K., Mohammad J. I., Kaveti B., Bera H., Palanimuthu V. R., Teh L. K., Salleh M. Z. Bioorg. Chem. 2016;67:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamali C., Gul H. I., Ece A., Taslimi P., Gulcin I. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2018;91:854–866. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozmen Ozgun D., Gul H. I., Yamali C., Sakagami H., Gulcin I., Sukuroglu M., Supuran C. T. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;84:511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meciarova M., Toma S., Magdolen P. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2003;10:265–270. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(02)00157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith J. M., Tichenor M. S., Apodaca R. L., Xiao W., Jones W. M., Seierstad M., Pierce J. M., Palmer J. A., Webb M., Karbarz M. J., Scott B. P., Wilson S. J., Wennerholm M. L., Rizzolio M., Rynberg R., Chaplan S. R., Breitenbucher J. G. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;26:3109–3114. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciro A., Park J., Burkhard G., Yan N., Geula C. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:138–143. doi: 10.2174/156720512799015127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg A., Ballard C., Bullock R., Darreh-Shori T., Somogyi M. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15:PCC.12r01412. doi: 10.4088/PCC.12r01412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard C. G. Eur. Neurol. 2002;47:64–70. doi: 10.1159/000047952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P., Srivastava P., Seth A., Tripathi P. N., Banerjee A. G., Shrivastava S. K. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019;174:53–89. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2018.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellman G. L., Courtney K. D., Andres V., Featherstone R. M. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine H. Protein Sci. 1993;2:404–410. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalili-Baleh L., Forootanfar H., Küçükkılınç T. T., Nadri H., Abdolahi Z., Ameri A., Jafari M., Ayazgok B., Baeeri M., Rahimifard M., Abbas Bukhari S. N., Abdollahi M., Ganjali M. R., Emami S., Khoobi M., Foroumadi A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;152:600–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Košak U., Brus B., Knez D., žakelj S., Trontelj J., Pišlar A., Šink R., Jukič M., živin M., Podkowa A., Nachon F., Brazzolotto X., Stojan J., Kos J., Coquelle N., Sałat K., Colletier J.-P., Gobec S. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:119–139. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung J., Rudolph M. J., Burshteyn F., Cassidy M. S., Gary E. N., Love J., Franklin M. C., Height J. J. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:10282–10286. doi: 10.1021/jm300871x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.