Over the past decade, several inhibitors of key metabolic dependencies have been shown to be active in AML, suggesting that targeting cellular metabolism is a promising therapeutic strategy for this disease. Specific inhibitors of the TCA cycle isoenzymes IDH1 and 2, mutated in approximately 20% of AML cases, abrogate the myeloid differentiation block and restore normal granulocytic/neutrophilic differentiation of IDH½-mutated AML blasts (1, 2). Moreover, lonidamine and 2-deoxy-D-glucose, two small molecules that inhibit the first rate-limiting step of glycolysis, have been demonstated to have potent anti-leukemic activities in AML cells in preclinial studies and are now being tested in early phase clinical trials (3, 4). While the inhibition of metabolic enzymes alters metabolite steady-state levels, it also impacts the activity of other downstream signaling pathways. For instance, glycolysis inhibition by lonidamine is associated with activation of the MEK/ERK pathway, which in the context of AML, could counteract the anti-leukemic effect of glycolysis inhibition (3). This example suggests that it is essential to identify both the favorable effects and the potential liabilities of metabolic perturbations on downstream signaling pathways in order to i) prevent potential resistance mechanisms to inhibition of the metabolic targets and ii) nominate combination therapies that may synergize with metabolic inhibitors.

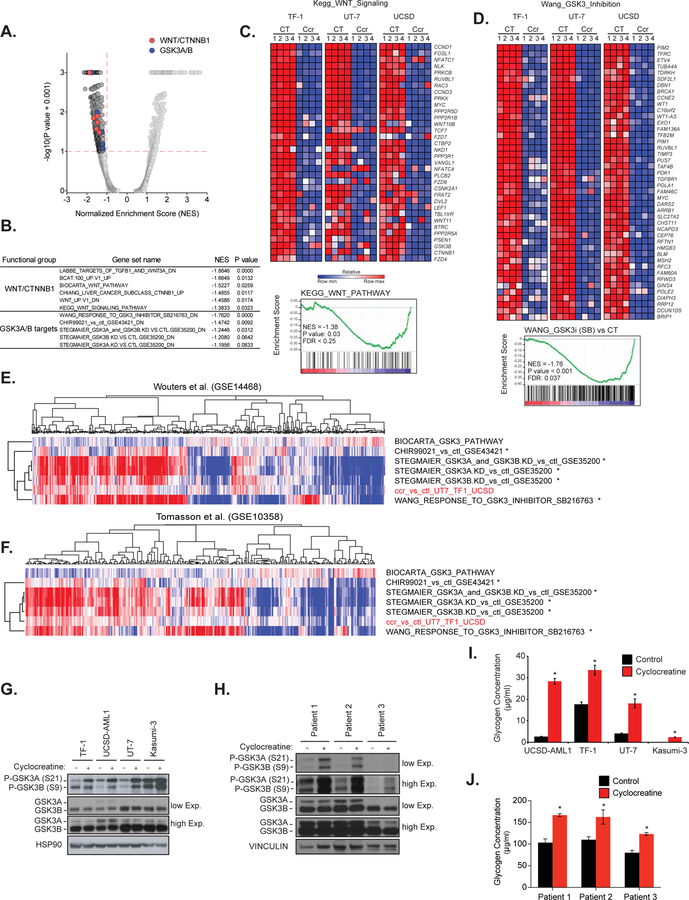

We recently identified the mitochondrial creatine kinase, CKMT1, involved in arginine-creatine metabolism, as a new metabolic vulnerability in the molecular subset of AML driven by the proto-oncogene EVI1 (5). We determined that suppression of arginine-creatine metabolism by CKMT1-directed shRNAs or by the small molecule cyclocreatine selectively altered the mitochondrial respiration and ATP production of EVI1-positive AML cells, thereby reducing their growth. In an effort to identify relevant signaling pathways that may be dysregulated by alteration of arginine-creatine metabolism, we interrogated by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) our transcriptional data generated through RNA-sequencing in three EVI1-positive AML cell lines, TF-1, UT-7 and UCSD-AML1, treated for 24h with cyclocreatine (GSE86151). This open-ended enrichment analysis revealed that gene sets related to the GSK3 and WNT pathways were among those most enriched in genes whose expression was suppressed by cyclocreatine (Figures 1A and 1B, Odds Ratio = 4.10, P value = 0.017; Odds Ratio =10.24, P value = 0.004 for WNT and GSK3 respectively, based on 2-tailed Fisher exact test). Creatine kinase (CK) pathway inhibition impaired the expression of both GSK3-target genes and protein members of WNT signaling from the most upstream genes involved in the pathway, such as WNT10b, WNT11, DVL2, FZD4, FZD6, and FZD7, to the most downstream targets, such as CTNNB1 and its well-reported targets MYC and CCND1 (Figures 1C and 1D).

Figure 1. Creatine Kinase pathway inhibition impairs GSK3 and WNT signaling.

(A–B) Quantitative comparison with GSEA of the c2 collection of 3,469 curated gene sets available from MSigDB v5.2 for TF-1, UT-7 and UCSD-AML1 cell lines treated with cyclocreatine for 24h relative to control treated cell lines (n = 3 per condition). Data are presented as a volcano plot of −log10(P value + 0.001) versus the normalized enrichment score (NES) for each evaluated gene set. P value and NES for gene sets related to GSK3 (blue) and WNT/CTNNB1 signaling (red) are listed. Gray dots indicate all other c2 gene sets.

(C–D) Heatmaps (top panel) and GSEA plots (bottom panel) for GSK3 and WNT signaling pathways in TF-1, UT-7 and UCSD-AML1 cell lines upon treatment with cyclocreatine for 24h. Depleted and enriched genes are respectively in blue and red. Data are presented as row normalized. P value ≤ 0.05, FDR ≤ 0.05 and absolute fold change for log2(FPKM) scores ≥ 1.5. CT: control, Ccr: Cyclocreatine.

(E–F) ssGSEA in two large human primary patient AML gene expression datasets Wouters et al. (n=526, GSE14468) and Tomasson et al. (n=304, GSE10358). Data are presented as heatmaps. Depleted and enriched genes are respectively in blue and red. * P value reporting the overlap between GSK3 and creatine kinase pathways inhibition signatures was calculated using a two-tailed Fisher exact test.

(G) Western immunoblot for p-GSK3A (S21), p-GSK3B (S9), GSK3A, GSK3B and HSP90 after cyclocreatine treatment.

(H) Western immunoblot for p-GSK3A (S21), p-GSK3B (S9), GSK3A, GSK3B and VINCULIN after cyclocreatine treatment of three EVI1-positive primary AML patient samples.

(I–J) Glycogen quantification after cyclocreatine treatment. *P value < 0.05 calculated using a Welch’s t-test in comparison with the control condition. Error bars represent mean ± SEM of three replicates.

Next, we performed single-sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) in two large human primary patient AML gene expression datasets Wouters et al. (n=526, GSE14468) and Tomasson et al. (n=304, GSE10358). In both datasets, a significant correlation was observed between the transcriptional signatures of GSK3 inhibition and creatine kinase pathway inhibition (Figures 1E, 1F and S1A). In line with these results, the level of GSK3 phosphorylation at the inhibitory serine sites of the two GSK3 isoforms (S21 on GSK3A and S9 on GSK3B) was strongly enhanced upon cyclocreatine treatment, confirming the inhibition of GSK3 in EVI1-positive AML cell lines and primary patient samples (Figures 1G and 1H). Interestingly, the basal level of S21/S9 GSK3 phosphorylation was higher in Kasumi-3, compared to the other EVI1-positive cell lines, suggesting less constitutive activation of GSK3 at baseline. Despite this high basal level of phosphorylation, GSK3 was further phosphorylated upon cyclocreatine treatment in Kasumi-3. Intracellular glycogen accumulation, which was previously reported as a direct phenotypic consequence of GSK3 inhibition (7), was also observed both by Periodic Acid-Schiff positive staining and glycogen dosage in cyclocreatine-treated AML cell lines and primary patient samples (Figures S1C, 1I and 1J). Moreover, we previously reported that cyclocreatine treatment induced cell cycle arrest in AML cells (5), and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 is a critical downstream mediator of the cell cycle arrest associated with GSK3 inhibition (8). Consistent with these reports, cyclocreatine treatment increased p27Kip1 levels in the EVI1-positive AML cell line TF-1 (Figure S1D).

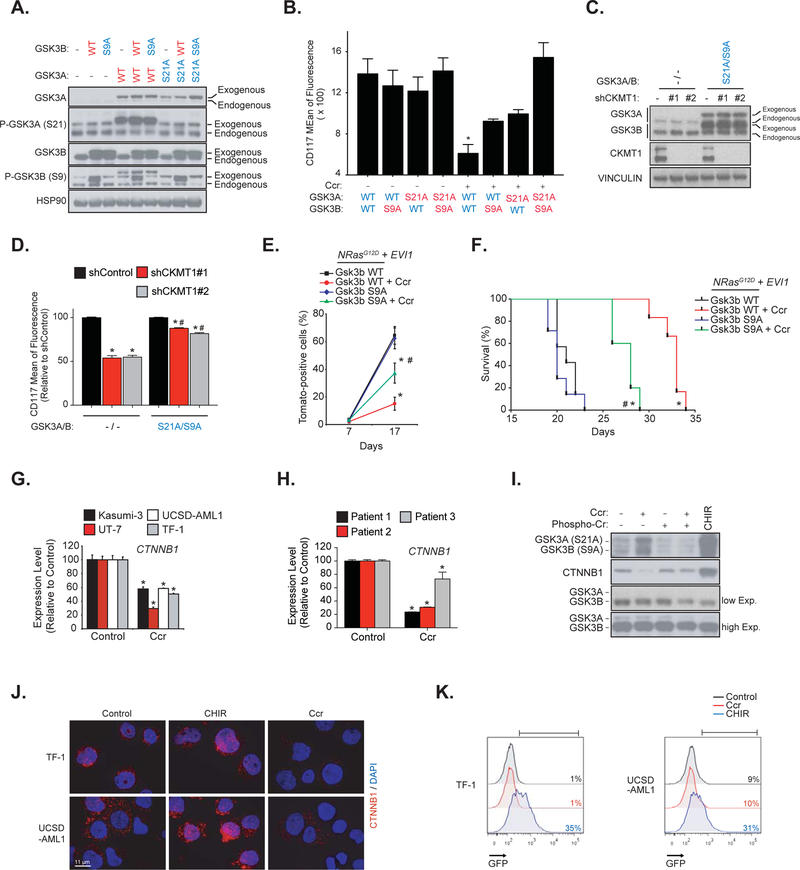

We recently reported that the reduced growth of EVI1-positive AML cell lines treated with cyclocreatine was associated with a decreased expression of the immature cell surface marker CD117 (5). We also compared the effect of CK pathway inhibition on two mouse models, one which develop an NrasG12D + Evi1-driven AML that contains a clonal Evi1 integration and expresses high transcript levels of Evi1 and a second AML expressing an NrasG12D that does not express Evi1. We established that the NrasG12D + Evi1-driven disease burden was selectively altered by CK pathway inhibition (5). To investigate whether inhibition of GSK3 signaling was important for such effects, we generated constitutively active GSK3 mutants by substituting serines 21 and 9 with non-phosphorylable alanines (S21A and S9A) on GSK3A and GSK3B, respectively (Figure 2A). Co-expression of GSK3A/B active mutants (S21A/S9A) in AML cells significantly attenuated the CD117 marker repression induced by cyclocreatine and CKMT1 knock-down (Figures 2B–D). In addition, overexpression of Gsk3b S9A in NrasG12D + Evi1 cells significantly attenuated the anti-leukemic effect of cyclocreatine and reduced survival of the Gsk3b S9A subgroup compared to the wild-type (WT) Gsk3b subgroup (Figures 2E and 2F). Taken together, these results showed that GSK3 plays a substantial role in the cellular effects induced by CK pathway inhibition.

Figure 2. The anti-leukemic effects of creatine kinase pathway inhibition are mediated by concomitant GSK3 inhibition and CTNNB1 silencing.

(A) Western immunoblot for p-GSK3A (S21), p-GSK3B (S9), GSK3A, GSK3B and HSP90 indicating the level of GSK3 construct overexpression in TF-1 cells.

(B) FACS analysis of the expression of the CD117 cell surface marker after cyclocreatine (Ccr) treatment in TF-1 cells. * P value < 0.05 calculated in comparison to the control condition. Error bars represent mean ± SEM of two biological replicates.

(C) Western immunoblot for GSK3A, GSK3B, CKMT1 and VINCULIN indicating the level of CKMT1 shRNA knock-down and GSK3A/B S21A/S9A overexpression in TF-1 cells.

(D) FACS analysis of the expression of the CD117 cell surface marker after CKMT1 shRNA knock-down in TF-1 cells stably expressing an empty vector or a GSK3A/B S21A/S9A overexpression construct. Data is represented relative to shControl within each expression construct. * P value < 0.05 calculated in comparison to shControl. # P value < 0.05 calculated in comparison to empty vector. Error bars represent mean ± SEM of four replicates. Statistical significance determined by a Mann-Whitney test.

(E) FACS analysis of N-RasG12D + Evi1 Tomato-positive cells in the bone marrow with error bars representing the mean ± SEM of three bone marrow samples analyzed per time point. Statistical significance determined by a Welch’s t-test.

(F) Kaplan-Meier curves showing overall survival of N-RasG12D + Evi1 and either wild-type (WT) or Gsk3b S9A mice (n = 7 for cyclocreatine-treated groups versus n = 5 for vehicle-treated groups). Statistical significance determined by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test.

(E–F) * P value < 0.05 by comparison with the corresponding vehicle-treated group (Gsk3b WT or Gsk3b S9A). # P value < 0.05 by comparison with cyclocreatine-treated Gsk3b WT group. Ccr: cyclocreatine.

(G–H) mRNA level of expression of CTNNB1 after cyclocreatine (Ccr) treatment in AML cell lines (G) and primary patient samples (H). * P value < 0.05 calculated using a Mann-Whitney test in comparison with the control condition. Error bars represent mean ± SEM of four replicates.

(I) Western immunoblot for p-GSK3A (S21), p-GSK3B (S9), GSK3A, GSK3B and CTNNB1 after cyclocreatine (Ccr), phosphocreatine (Phospho-Cr) and CHIR 99–021 (CHIR) treatment in UCSD-AML1 cells.

(J) CTNNB1 immunofluorescence staining after cyclocreatine (Ccr) and CHIR 99–021 (CHIR) treatment (CTNNB1 in red and DAPI in blue).

(K) Representative FACS analysis of a CTNNB1 TCF/LEF GFP reporter assay in response to cyclocreatine (Ccr) and CHIR 99–021 (CHIR) treatment. Colored number is percentage of positive cells.

We and others have previously identified GSK3 as a target in hematopoietic cells transformed by HOX genes, and chemical inhibition or shRNA-targeting of either GSK3A selectively, or both GSK3A and GSK3B, were shown to impair AML cell viability and promote in vitro granulo-monocytic differentiation (6, 9–11). While targeting GSK3 seems to be an interesting alternative in AML, all of these studies also raised an important question concerning the feasibility of such a therapeutic intervention given the role of GSK3 in WNT pathway regulation and HSC homeostasis (12). Indeed, decreased expression or activity of GSK3 in the bone marrow promotes the expansion of HSCs through stabilization of CTNNB1 and a WNT-dependent activation of stem cell self-renewal (13, 14). Interestingly, in addition to its inhibitory effect on GSK3, cyclocreatine treatment also repressed the mRNA and protein levels of CTNNB1 (Figures 2G–I), and this effect was counteracted by reactivation of arginine-creatine metabolism upon phospho-creatine supplementation (Figure 2I). The GSK3 inhibitor, CHIR 99–021, was used as a positive control for CTNNB1 accumulation (Figure 2I). Despite GSK3 pathway inhibition, cyclocreatine treatment prevented nuclear CTNNB1 accumulation in TF-1 and UCSD-AML1 cells and thereby did not activate a TCF/LEF-GFP reporter system. In contrast, CHIR 99–021 stabilized CTNNB1 (Figures 2J and 2K).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the blockade of the creatine pathway inhibits GSK3 and silences WNT pathway, thus impeding the canonical control of GSK3 on the WNT pathway through CTNNB1. By turning off WNT signaling, most likely through transcriptional downregulation of the entire pathway – including FZD4, FZD6, and CTNNB1 itself – CK pathway inhibition allows the anti-leukemic and pro-maturation effects of GSK3 inhibition without activation of the pro-leukemogenic WNT signaling pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Kevin Shannon for advice and discussions. We thank the Saint-Louis Hospital’s Tumor Biobank (Daniela Geromin, Carole Albuquerque) for managing patient AML samples. This research was supported with grants from the US National Cancer Institute (NCI) (NIH R35 CA210030; KS), the Children’s Leukemia Research Foundation (CLRF), and the Bridge Project, a collaboration between the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT and the Dana-Farber–Harvard Cancer Center (DF–HCC) (K.S. and M.T.H.). KS is a Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar. AP is a recipient of support from the ERC Starting Grant (H2020), the ATIP–AVENIR and LNCC French research programs, the EHA research grant for a Non-Clinical Advanced fellow, and is supported by the St. Louis Association for leukemia research. LB is an MD-PhD candidate of “Ecole de l’INSERM Liliane Bettencourt” and a recipient of Philippe Foundation and GPM fellowships.

Footnotes

Disclosure of conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Chaturvedi A, Herbst L, Pusch S, Klett L, Goparaju R, Stichel D, et al. Pan-mutant-IDH1 inhibitor BAY1436032 is highly effective against human IDH1 mutant acute myeloid leukemia in vivo. Leukemia 2017;31(10):2020–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang F, Travins J, DeLaBarre B, Penard-Lacronique V, Schalm S, Hansen E, et al. Targeted inhibition of mutant IDH2 in leukemia cells induces cellular differentiation. Science 2013;340(6132):622–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calvino E, Estan MC, Simon GP, Sancho P, Boyano-Adanez Mdel C, de Blas E, et al. Increased apoptotic efficacy of lonidamine plus arsenic trioxide combination in human leukemia cells. Reactive oxygen species generation and defensive protein kinase (MEK/ERK, Akt/mTOR) modulation. Biochem Pharmacol 2011;82(11):1619–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estan MC, Calvino E, de Blas E, Boyano-Adanez Mdel C, Mena ML, Gomez-Gomez M, et al. 2-Deoxy-D-glucose cooperates with arsenic trioxide to induce apoptosis in leukemia cells: involvement of IGF-1R-regulated Akt/mTOR, MEK/ERK and LKB-1/AMPK signaling pathways. Biochem Pharmacol 2012;84(12):1604–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenouille N, Bassil CF, Ben-Sahra I, Benajiba L, Alexe G, Ramos A, et al. The creatine kinase pathway is a metabolic vulnerability in EVI1-positive acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Med 2017;23(3):301–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerji V, Frumm SM, Ross KN, Li LS, Schinzel AC, Hahn CK, et al. The intersection of genetic and chemical genomic screens identifies GSK-3alpha as a target in human acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Invest 2012;122(3):935–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Georgievska B, Sandin J, Doherty J, Mortberg A, Neelissen J, Andersson A, et al. AZD1080, a novel GSK3 inhibitor, rescues synaptic plasticity deficits in rodent brain and exhibits peripheral target engagement in humans. J Neurochem 2013;125(3):446–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Smith KS, Murphy M, Piloto O, Somervaille TC, Cleary ML. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 in MLL leukaemia maintenance and targeted therapy. Nature 2008;455(7217):1205–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z, Iwasaki M, Ficara F, Lin C, Matheny C, Wong SH, et al. GSK-3 promotes conditional association of CREB and its coactivators with MEIS1 to facilitate HOX-mediated transcription and oncogenesis. Cancer Cell 2010;17(6):597–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta K, Gulen F, Sun L, Aguilera R, Chakrabarti A, Kiselar J, et al. GSK3 is a regulator of RAR-mediated differentiation. Leukemia 2012;26(6):1277–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner FF, Benajiba L, Campbell AJ, Weiwer M, Sacher JR, Gale JP, et al. Exploiting an Asp-Glu “switch” in glycogen synthase kinase 3 to design paralog-selective inhibitors for use in acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Transl Med 2018;10(431). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Bertrand FE, Davis NM, Abrams SL, Montalto G, et al. Multifaceted roles of GSK-3 and Wnt/beta-catenin in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis: opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Leukemia 2014;28(1):15–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trowbridge JJ, Xenocostas A, Moon RT, Bhatia M. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 is an in vivo regulator of hematopoietic stem cell repopulation. Nat Med 2006;12(1):89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J, Zhang Y, Bersenev A, O’Brien WT, Tong W, Emerson SG, et al. Pivotal role for glycogen synthase kinase-3 in hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis in mice. J Clin Invest 2009;119(12):3519–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.