Abstract

Lipid raft domains, where sphingolipids and cholesterol are enriched, concentrate signaling molecules. To examine how signaling protein complexes are clustered in rafts, we focused on the functions of glycoprotein M6a (GPM6a), which is expressed at a high concentration in developing mouse neurons. Using imaging of lipid rafts, we found that GPM6a congregated in rafts in a GPM6a palmitoylation-dependent manner, thereby contributing to lipid raft clustering. In addition, we found that signaling proteins downstream of GPM6a, such as Rufy3, Rap2, and Tiam2/STEF, accumulated in lipid rafts in a GPM6a-dependent manner and were essential for laminin-dependent polarity during neurite formation in neuronal development. In utero RNAi targeting of GPM6a resulted in abnormally polarized neurons with multiple neurites. These results demonstrate that GPM6a induces the clustering of lipid rafts, which supports the raft aggregation of its associated downstream molecules for acceleration of neuronal polarity determination. Therefore, GPM6a acts as a signal transducer that responds to extracellular signals.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Lipid raft domains, where sphingolipids and cholesterol are enriched, concentrate signaling molecules. We focused on glycoprotein M6a (GPM6a), which is expressed at a high concentration in developing neurons. Using imaging of lipid rafts, we found that GPM6a congregated in rafts in a palmitoylation-dependent manner, thereby contributing to lipid raft clustering. In addition, we found that signaling proteins downstream of GPM6a accumulated in lipid rafts in a GPM6a-dependent manner and were essential for laminin-dependent polarity during neurite formation. In utero RNAi targeting of GPM6a resulted in abnormally polarized neurons with multiple neurites. These results demonstrate that GPM6a induces the clustering of lipid rafts, which supports the raft aggregation of its associated downstream molecules for acceleration of polarity determination. Therefore, GPM6a acts as a signal transducer that responds to extracellular signals.

Keywords: cholesterol, GPM6a, growth cone, lipid rafts, palmitoylation, polarity

Introduction

Lipid raft domains, where sphingolipids and cholesterol are enriched, are thought to concentrate signaling molecules as a result of their lower fluidity compared with other membrane areas in various cell types (Lingwood and Simons, 2010). However, because neurons have a much higher concentration of these lipid species than any other cell type (Aureli et al., 2015), the importance of lipid rafts in neuronal signaling is not clear.

We focused on the glycoprotein M6a (GPM6a), which, similar to myelin proteolipid protein (PLP; Schneider et al., 2005), is localized in the neuronal plasma membrane through four transmembrane domains (Möbius et al., 2008). GPM6a is one of the major palmitoylated proteins in the brain (Kang et al., 2008). Because palmitoylated membrane proteins are generally known to accumulate in lipid raft domains (Fukata and Fukata, 2010), this protein should be a good candidate for the study of neuronal lipid rafts. GPM6a is a physiological substrate of the palmitoyl acyltransferase HIP14 (Butland et al., 2014), a protein that associates with huntingtin, which is related to the human neurodegenerative disease Huntington's disease (HD); a dysfunctional mutant of HIP14 itself is also a causative gene for HD.

Some information is currently available regarding the function of this protein in neuronal development. GPM6a is neuron specific and is highly expressed in differentiated neurons compared with its expression in stem cells (Yan et al., 1993; Alfonso et al., 2005; Michibata et al., 2008). Furthermore, our proteomic study indicated that GPM6a is one of the major membrane proteins of growth cones (Nozumi et al., 2009), specialized, highly motile structures located at the tip of extending axons in developing neurons that are crucial for accurate synaptogenesis (Bloom and Morgan, 2011; Gordon-Weeks and Fournier, 2014; Igarashi, 2014), although their exact physiological function is not known.

We therefore hypothesized that the GPM6a in lipid rafts might be involved in a key step of neuronal morphogenesis and therefore searched for factors downstream of GPM6a. We found that GPM6a is colocalized with D4, a cholesterol-binding protein and a molecular imaging marker for lipid rafts (Ishitsuka et al., 2011). In addition, lipid rafts containing GPM6a were clustered; however, in the absence of GPM6a, no rafts were clustered and D4 was dispersed in the membrane. GPM6a itself was accumulated at the origin of the neurite. We identified the downstream signaling molecules of GPM6a as the Rufy3-Rap2-STEF/Tiam2 complex and the components of this complex have been reported previously to be determinants for cell polarity in a cell-autonomous manner (Nishimura et al., 2005; Mori et al., 2007). GPM6a signaling pathway molecules are collected and concentrated in lipid rafts in a manner that is dependent on the palmitoylated form of GMP6a, even at stage 1 of neuron formation. These effects of GMP6a are indispensable for polarity signal transduction, are induced by the extracellular stimulator laminin (LN), and strikingly accelerate the neuronal polarity decision by shortening stage 2. In addition, GPM6a was asymmetrically localized at the future neurite origin site before neurite outgrowth and subsequently continued to localize at the tip of the neurite and in the growth cone area after axon determination. The combined data indicate that palmitoylated GPM6a induces the clustering of lipid rafts and that a palmitoylation-dependent GPM6a-signaling protein complex is formed in the lipid rafts at stage 1 of neuron formation, which acts as one of the earliest polarity determinants and accelerators for neuron formation.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and reagents.

The antibodies used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antibodies used in immunodetection

| Antigen | Species | IF | WB | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPIPx/mKIAA0871/Singar/Rufy3 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1/1000 | 1/1000 | H. Koga (Kazusa DNA Institute, Japan) |

| STEF/Tiam2 | Rat monoclonal IgG | 1/1000 | 1/1000 | M. Hoshino (National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Japan) |

| Glycoprotein M6a | Rat monoclonal IgG | 1/1000 | 1/1000 | T. Hirata (National Institute of Genetics, Japan) |

| Glycoprotein M6a | Rat monoclonal IgG | 1/1000 | 1/1000 | Medical & Biological Laboratories |

| Integrin β1/CD29 | Rat monoclonal IgG | 1/400 | 1/1000 | BD Biosciences |

| Rap2 | Mouse monoclonal IgG | 1/500 | 1/1000 | BD Biosciences |

| βIII tubulin | Mouse monoclonal IgG | 1/1000 | 1/2000 | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Par3 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1/1000 | 1/1000 | Millipore |

| Flotillin1 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1/500 | 1/1000 | Millipore |

| GFP | Rabbit polyclonal | 1/1000 | 1/1000 | Medical & Biological Laboratories |

| HA | Mouse monoclonal IgG | 1/1000 | 1/1000 | Medical & Biological Laboratories |

| Flag | Mouse monoclonal IgG | 1/1000 | 1/1000 | Medical & Biological Laboratories |

| Myc | Mouse monoclonal IgG | 1/1000 | 1/1000 | Millipore |

Labeling of the His-tagged EGFP-D4.

The His-EGFP-tagged θ toxin domain 4 (His-EGFP-D4) was produced using E. coli. Dissociated or adhered cells were incubated in 10% FBS/L-15 containing 10 μg/ml His-tag-EGFP-D4 at 37°C for 10 min. After washing, the EGFP-D4 labeled cells were observed or were fixed with 4% PFA for immunostaining.

Plasmid construction for shRNAs.

The plasmid pCS-U6-CA-GFP that was used for expression of short hairpin RNA (shRNA) was described previously (Okada et al., 2014). Small-interference RNA sequences for knock-down of the mouse Gpm6a gene were designed by BLOCK-iT RNAi Designer (Life Technologies). The Gpm6a target 21-nucleotide sequences were 5′-GCATTGCGGCTGCTTTCTTTG (#5), 5′-GGCTATCAAAGATCTCTATGG (#7), and 5′-GGCATTGGTGTTTCATTAAGG (#8). A nontarget control sequence, 5′-CAACAAGATGAAGAGCACCAA, obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, was used as a negative shRNA control (shNeg). We also used an empty vector negative control, Bsm. Synthetic oligonucleotides for top and bottom sequences corresponding to the shRNAs were annealed, phosphorylated, and cloned between BsmBI and XhoI sites in the pCS-U6-CA-GFP plasmid.

WT plasmids and the palmitoylation mutant GPM6a plasmid.

cDNA fragments encoding WT mouse GPM6a, Rufy3, Rap2, and STEF were amplified using PCR and subcloned into pEGFP (Clontech Laboratories), pFLAG-CMV (Sigma-Aldrich), or pcDNA3-HA vectors. To generate palmitoyl site mutations of GPM6a (ΔPal mutant; C17, 18, 21S), inverse PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis35 was performed using the KOD-Plus mutagenesis kit (Toyobo) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primer used was the following sense primer of C17, 18, 21S M6a: tcctccattaaatccctgggaggtattccctatgcttc.

Gene targeted mice.

GPM6a-KO male and female mice (Mita et al., 2015) were kindly provided by T. Hirata (National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Japan).

Proteomic analysis of protein binding partners.

Vectors encoding pFLAG-tagged proteins that were used as bait were transfected into HEK293 cells (Table 2). Forty-eight hours later, the expressed proteins were immunoprecipitated with the anti-pFLAG-tag Ab and coprecipitated binding partners were analyzed using mass spectrometry. To search effectively for cytosolic binding partners, the residues of GPM6a to which sugar chains ware attached and the CAAX box of Rap2A were modified or deleted. After identification of coprecipitated Rufy3 and Tiam2/STEF, those modifications did not affect their binding interactions with WT-GPM6a and WT-Rap2A (see Fig. 5).

Table 2.

GPM6a-interacting proteins revealed by proteomics

| # | Protein name | No. of total peptides |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Glycoprotein M6A | 7 |

| 2 | Seizure related 6 homolog (mouse)-like 2 (SEZ6L2) | 3 |

| 3 | Glycoprotein m6b | 2 |

| 4 | LYRIC; metadherin | 2 |

| 5 | Transmembrane protein 30A | 1 |

| 6 | Xenotropic and polytropic retrovirus receptor 1 | 1 |

| 7 | Trophoblast glycoprotein; 5T4 oncotrophoblast antigen | 1 |

| 8 | Cysteine-rich with EGF-like domains 1 (CRELD1) | 1 |

| 9 | KIAA0970 protein; fibronectin type III domain containing 3A (FDCA3A) | 1 |

FLAG-tagged GPM6a expressed in HEK293 cells was immunoprecipitated by anti-FLAG Ab and the immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by mass spectrometry.

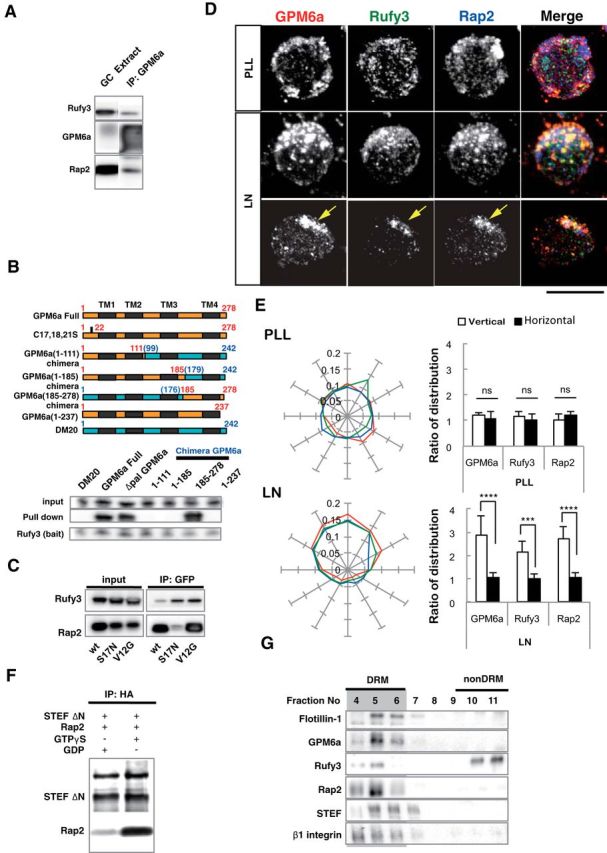

Figure 5.

GPM6a-RUFY3-Rap2-STEF/Tiam2 forms a protein complex that is enriched in lipid rafts. A, Immunoprecipitation (IP) of the Triton X-100 extracts of growth cone (GC) fractions using an anti-GPM6a Ab. The blots were immunostained with Abs against GPM6a, Rufy3, and Rap2. The RUN domain protein Rufy3 and a small GTPase, Rap2, were coprecipitated with GPM6a, suggesting the presence of a GPM6a-Rufy3-Rap2 ternary complex in vivo. B, Identification of the Rufy3-binding region of GPM6a using GPM6a mutants. Top, To maintain the four-transmembrane domain in the mutants, chimeras of GPM6a and DM20, another member of the PLP family, were constructed. The fragments derived from GPM6a (orange) were joined with those from DM20 (blue). The amino acid numbers of GPM6a and DM20 are shown in red and blue respectively. Transmembrane domains are shown in black. (See Sato et al., 2011). Bottom, Constructs containing EGFP-tagged full-length GPM6a (aa 1–278), Δpal-GPM6a, chimeras, or a C-terminus deletion (aa 1–237) were coexpressed with myc-Rufy3 in COS-7 cells. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-myc antibody. The input was Western blotted with an anti-myc (Rufy3, bait) or an anti-GFP antibody (input) and the immunoprecipitate (pull-down) was Western blotted using an anti-EGFP (input) and myc Abs (bait). The Rufy3-binding site of GMP6a was determined as being located within GPM6a aa 185–278. C, Characterization of Rap2 binding to Rufy3. FLAG-tagged Rap2, the GDP-binding DN form (S17N), or the GTP-binding CA form (V12G) was preincubated with EGFP-Rufy3. EGFP-Rufy3 was immunoprecipitated with an anti-EGFP Ab and coprecipitated Rap2 was detected by Western blotting with anti-FLAG. The GDP-bound form of Rap2 lost the ability to bind Rufy3. D, GPM6a, Rufy3, and Rap2 are colocalized in cortical neurons grown on LN 30 minutes after plating of cortical neurons on LN but not on PLL. Iimmunofluorescence analysis indicated that the asymmetrically assembled endogenous GPM6a (red) was colocalized with endogenous Rufy3 (green) and Rap2 (blue). Arrows indicate their cellular accumulation sites. Scale bar, 20 μm. E, Left, Cumulative angular probability distribution of fluorescence of the GPM6a (red), Rufy3 (green), and Rap2 (blue) in Figure 3D. Right, Ratio of the fluorescence intensities of GPM6a, Rufy3, and Rap2 on the vertical or horizontal axis is shown. Asymmetric localization of each protein was specifically observed in neurons on LN. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 20 for each; two-tailed t test, vertical vs horizontal; LN-GPM6a, 2.90 ± 0.79 vs 1.07 ± 0.20; LN-Rufy3, 2.17 ± 0.47 vs 1.03 ± 0.18; LN-Rap2, 2.70 ± 0.56 vs 1.06 ± 0.19). ***p < 0.001. F, GTP-bound Rap2 specifically interacts with the Rac1 GEF Tiam2/STEF. HA-STEF was preincubated with FLAG-Rap2 in the presence of GTPγ with FLAG. HA-STEF was immunoprecipitated using an anti-HA antibody and coprecipitated Rap2 was detected by blotting with an anti-FLAG Ab. G, The complex components downstream of GPM6a were distributed in the DRM. Mouse brains were lysed and subjected to a sucrose density gradient and collected fractions were Western blotted for the indicated proteins. The DRM marker flotillin 1 was detected in fractions #4 to #6; GPM6a, Rap2, STEF, and β1 integrin (a LN receptor) were enriched in DRMs and Rufy3 was also found in these fractions.

Neuronal cell culture.

Dissociated neuron cultures were prepared from embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5) or E16.5 mice. Cortices were dissected in cold DMEM (Wako) under a stereomicroscope and incubated in AccuMax (final concentration, 50%; Innovative Cell Technologies) in HBSS (Wako) for 10 min at 37°C. Neurons were suspended in 10% FBS (Invitrogen)/DMEM and filtered through a 40 μm cell strainer (BD Falcon). Neurons were counted and plated on coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine (PLL) or LN (2 μg/ml; Invitrogen) using Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27 glutaMax (x1 final concentration) and penicillin/streptomycin. For time-lapse recording or EGFP-D4 labeling of live cells, neurons were cultured at 37°C without the CO2 control in L-15 (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27, glutaMax (x1 final concentration (Invitrogen)), 0.45% glucose and penicillin/streptomycin. Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) treatment was as described previously (Scorticati et al., 2011).

For overexpression or rescue experiments, the transfected cells were precultured in a LIPIDURE-coated 96-well plate (NOF Corporation, Japan) at 37°C for 24 h.

Transfection of neurons.

For transfection, dissociated neurons (1 × 106) were placed in 2 mm gap cuvettes (BEX) containing 100 μl of Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) with 2–5 μg of plasmid DNA or 50 nm siRNA, and were transfected using 10 direct-current electrical pulses with an intensity of 20 V at intervals of 50 ms using an electroporator (CUY 21 Vitro-EX, BEX Co., Ltd.). The transfected cells were precultured in a LIPIDURE coated 96-well plate (NOF Corporation, Japan) at 37°C without the CO2 control in L-15 supplemented with 10% FBS, B27, 0.45% glucose and penicillin/streptomycin. After 24 h, the sedimented cells were suspended and replated on coverslips coated with PLL or LN (2 μg/ml; Invitrogen).

Immunofluorescence.

The cells were fixed for 30 min with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS, pH 7.4. After fixation, the cells were rinsed 3 times with PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. The permeabilized cells were incubated in 2% BSA–PBS for 1 h and then incubated with 2% BSA–PBS containing primary antibodies overnight. For staining of extracellular GPM6a or EGFP-D4, the fixed cells were incubated directly in 2% BSA–PBS for 1 h before staining. After the first antibody treatment, the cells were rinsed with PBS and incubated with secondary antibody for 3 h. Finally, the cells were washed with PBS and mounted in fluorescent mounting medium (Dako).

Coronal slices (50–75 μm thick) were prepared from fixed brains using the Leica vibratome VT1000S. The sections were permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and then blocked with 5% BSA–PBS for 1 h. Slices were incubated with 5% BSA–PBS containing primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the slices were rinsed with PBS and incubated with secondary antibody for 3 h. Finally, the coronal slices were washed with PBS and mounted in fluorescent mounting medium (Dako). Preparations were examined under an Olympus BX63 fv2000 confocal microscope and a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope.

Time-lapse experiment.

pmCherry-C1-ms GPM6a or Δpal GPM6a was electroporated into dissociated E14.5 mouse cortical neurons (5 μg of plasmid/L × 106 cells) and the neurons were than cultured with 10% FBS/L-15 in LIPIDURE-coated 96-well plates. After 24 h, the sedimented cortices were suspended in 10% FBS/L-15 and filtered through a 40 μm cell strainer. EGFP-positive neurons were plated on a glass-bottom dish coated with PLL or laminin using L-15 supplemented with B27, GlutaMax, glucose, and penicillin/streptomycin. The glass-bottom dish was prewarmed in a temperature-controlled incubation chamber (at 37°C; Tokai Hit) fitted onto a confocal microscope (Olympus, FV2000). Both DIC and fluorescence images were obtained over 2–12 h with a cooled CCD camera and these images were processed using the image analysis software MetaMorph (Molecular Devices).

Rac1 activity assay.

The DNA fragment spanning the p21 binding domain (PBD/CRIB region 67–150; Cdc42-Rac interactive binding region) of PAK was amplified using PCR and subcloned into pEGFP-C1 to generate pEGFP-PAK-PBD. For preparation of GFP-PAK PBD immobilized beads, GFP-PAK PBD was expressed in COS-7 cells and purified from COS-7 cells by immunoprecipitation with an anti-EGFP Ab.

Pull-down assay and immunoprecipitation assay.

The growth cone fraction of mouse forebrain was isolated and extracted as described previously (Nozumi et al., 2009). The COS-7 cells that had been transfected using electroporation were washed with cold PBS, lysed with lysis buffer I (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mm EDTA), sonicated, and centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4°C. The Abs against the recombinant proteins were coupled to protein G beads (Invitrogen; 1 μg of antibody/μl of resin) and incubated with the cell extracts at 4°C for 2 h. The resin was washed 3 times and eluted with 1× sample buffer for SDS-PAGE.

Preparation of DRM fractions.

Detergent-resistant membrane (DRM) fractions were prepared as described by Simons and Ikonen (1997) with some modifications. Embryonic mouse brains (E14.5) were dissected in PBS on ice. Lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, phosphatase inhibitor mixture, APMSF, leupeptin, and pepstatin) with 1% Brij 98 and 5% glycerol was added to the brain (brain: buffer II = 8:1, vol:wt) and the brain was homogenized. The homogenate was mixed well and placed on ice for 1 h. After centrifugation, the supernatant was gently mixed with an equal volume of 80% sucrose lysis buffer. The sample was placed at the bottom of an ST40 Ti centrifuge tube and sequentially overlaid with 4 ml of 35% sucrose lysis buffer and 4 ml of 5% sucrose lysis buffer. After centrifugation for 18 h at 20,000 × g using an ST40 Ti rotor, the DRMs had floated to the top of the gradient. Twelve fractions (1 ml/fraction) were then carefully collected from the top of the gradient using a Hitachi gradient generator.

Protein localization assay.

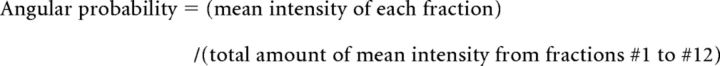

For analysis of protein localization in neurons, we used the angular probability distribution assay. In this assay, the area of the isolated neuron was radially partitioned into 12 fractions from the center with the radial grid plug-in tool of ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). Each fraction was outlined with the freehand ROI tool of ImageJ and mean intensities of the fluorescence in each fraction were analyzed. The fraction with maximum fluorescence intensity was designated fraction #1 and the other fractions were then sequentially counted clockwise to fraction #12. Angular probability distribution was calculated as follows:

|

For the assay of protein localization in the growth cone in a stage 3 neuron, we analyzed the ratio of immunofluorescence in the growth cone to that in the axonal shaft. Mean intensity of immunofluorescence in the growth cone or the axon shaft was measured in a squared ROI of ImageJ. The growth cone was entirely enclosed within a ROI and the mean intensity was analyzed. For measurement of the intensity of the shaft, the ROI was set at least 10 μm away from the cell body.

Colocalization assay.

We used the ImageJ plugin “colocalization color map” to determine protein colocalization to automatically quantify the correlation between a pair of pixels. Distribution of the normalized mean deviation product (nMDP) value is shown with a color scale and average nMDPs were compared.

Polarity assay.

At 30 min or 4 h after plating, isolated neurons that had immediately attached or that protruded a single short (3–5 μm) filopodia or lamellipodia within an angle of 90° from the center were considered as monopolar; that is, stage 3 neurons. Neurons protruding bipolar or multiple plural filopodia or lamellipodia within an angle of 90° were considered bi- or multipolar; that is, stage 2 neurons. Neurons with a lamellipodia formed over an angle of 180° or those with no filopodia or lamellipodia were defined as neutral or intact; that is, stage 1 neurons.

At 72 h after plating, isolated neurons projecting single major neurites that were at least twice as long as other processes were counted as polarized; that is, stage 3 neurons. Neurons with minor but not major neurites were counted as unpolarized; that is, stage 2 neurons. Neurite tracing and measurement of neurite length were done using the NeuronJ plug-in of ImageJ.

In utero electroporation.

In utero electroporation was performed on E14 using pregnant ICR mice and C57BL/6NCrlCrlj mice as described previously (Tabata and Nakajima, 2001) with some modification. In brief, pregnant mice were deeply anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of pentobarbital (48.6 mg/kg body weight) and their uterine horns were exposed. Plasmid DNA purified with the QIAGEN plasmid maxi kit was dissolved in HBS buffer solution (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl) with 0.01% Fast Green solution. Approximately 1 μl of plasmid solution was injected into the lateral ventricle using a processed microcapillary made from a glass tube (#3-000-105-G, Drummond GD-1; Narishige). Electroporation was performed using a disc electrode (CUY650P3; Bex) and electroporator (CUY21 Edit II; Bex, Nepa21; Nepa gene) under the following conditions: voltage, 35 V; pulse-on, 50 ms; pulse-off, 450 ms; pulse times, 5. The uterine horns were placed back into the abdominal cavity to allow the embryos to continue normal development.

Time-lapse experiments for RNAi were performed as described previously (Tabata and Nakajima, 2001) with some modification. In utero electroporation was performed as above on E14 embryos. Organotypic coronal brain slices (250 μm thick) at the level of the anterior commissure and interventricular foramen were prepared at 2 d after electroporation (E16) using a vibrating microtome (Thermo Scientific). The slices in HBSS (Wako) were then placed on an insert membrane (pore size, 0.4 μm; Millipore) and cultured as described previously (Namba et al., 2014). The culture dishes were then mounted in a CO2 incubator chamber (5% CO2, at 37°C) fitted onto a FV1000 confocal laser microscope and the dorsomedial region of the neocortex was examined. Approximately 10–20 optical Z sections were acquired automatically every 30 min for 24 h and 20 focal planes (50 μm thick) were merged to visualize the entire shape of the cells.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed t test, the Mann–Whitney test, one-way ANOVA, or two-way fractional ANOVA to calculate p-values. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Calculations were performed using Microsoft Office Excel and GraphPad Prism 6.0 software.

Results

Palmitoylation of GPM6a is necessary for its accumulation in lipid rafts

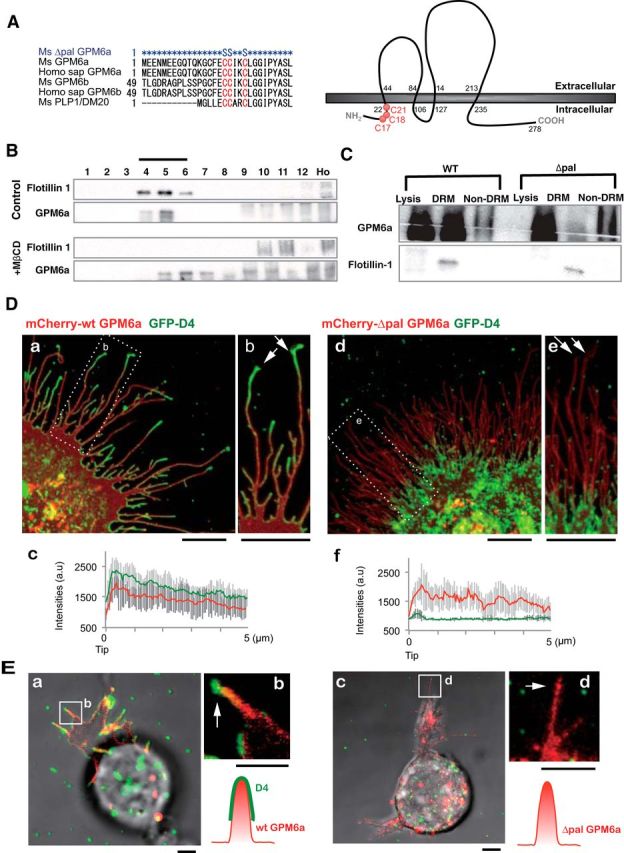

We first investigated whether GPM6a requires palmitoylation for its functions. Protein palmitoylation requires a few neighboring cysteine residues within the protein (Fukata and Fukata, 2010). Therefore, similar to the reported palmitoylation site in PLP (Schneider et al., 2005), the cluster of cysteine residues in the N-terminus region of GPM6a is the most likely location for palmitoylation. We therefore constructed Δpal-GPM6a (C17, 18, 21S) as a palmitoylation-deficient mutant (Fig. 1A). Palmitoylation of membrane proteins generally results in a shift of the protein into the DRM fraction, which is considered to biochemically represent the lipid raft domains of the plasma membrane. To first confirm the accumulation of GPM6a in lipid rafts, we fractionated E14.5 mouse brain homogenates to obtain the DRM fraction. Western blotting of the obtained fractions indicated that brain-derived GPM6a was primarily recovered in the DRM fraction, along with the lipid raft marker flotillin-1 (Fig. 1B), which we found previously to be a growth cone membrane protein using proteomics analysis (Nozumi et al., 2009). Depletion of cholesterol, which is enriched in lipid rafts, using MβCD resulted in the exclusion of both GPM6a and flotillin-1 from the DRM fractions, providing further evidence of the localization of GPM6a in lipid rafts (Fig. 1B). In addition to brain–DRM fractionation, we also performed DRM fractionation of Neuro2a cells overexpressing WT-GPM6a or Δpal-GPM6a. This experiment showed that WT-GPM6a was collected into the DRM fraction (Fig. 1C), but that Δpal-GPM6a was isolated in the non-DRM fractions (Fig. 1C), confirming that palmitoylation of GPM6a is critical for its localization to lipid rafts.

Figure 1.

Palmitoylation of GPM6a is necessary for its enrichment in lipid rafts. A, Left, Alignment of amino acids in the first intracellular segment of mouse (Ms) and human (Homo sap) GPM6a and its homologs. Conserved cysteines that are mutated to serine in the mouse Δpal-GPM6a mutant (top) are indicated in red. Right, Diagram of mouse GPM6a, showing the location of its palmitoylation sites at C17, C18, and C21 (red). B, GPM6a is localized in cholesterol-rich DRM fractions. E14.5 mouse brain homogenates were treated with 1% Brij98 and DRMs were fractionated using sucrose gradient centrifugation. In the control, GPM6a and a DRM marker flotillin 1 were colocalized in fractions #4 to #6. Colocalization of GPM6a and flotillin 1 in these fractions was inhibited by removal of cholesterol by MβCD treatment (+MβCD). C, Defective palmitoylation resulted in the exclusion of GPM6a from the DRM fraction. Neuro2a cells with overexpressed WT-GPM6a (WT) or Δpal-GPM6a [mutated at C17S, C18S, and C21S (C17, 18, 21S); Δpal] were lysed and fractionated into DRM or non-DRM fractions. Loss of palmitoylation inhibited the localization of GPM6a into the DRM fractions. D, E, Overexpressed GPM6a in COS-7 cells (D) and in GPM6a-KO cortical neurons (E) assembles cholesterol at the tips of GPM6a-induced filopodia via its palmitoylation. The live cells were labeled with EGFP-D4, a live-imaging marker for cholesterol-rich membrane domains. EGFP-D4 on the cell surface and the localization of overexpressed mCherry-GPM6a were observed using immunofluorescence. Da–Dc, Ea, Eb, mCherry-tagged WT-GPM6a. Dd–Df, Ec, Ed, Δpal-GPM6a. Db, De, Eb, Ed, Magnified views of the white boxes (Da and De and Ea and Ec, respectively). Shown is the quantitative distribution of the fluorescence intensities of WT-GPM6a (Dc) or Δpal-GPM6a (Df): red, D4: green). Measurements were performed within 5 μm from a filopodial tip. n = 10 for each (means ± SD). EGFP-D4 was assembled on the tip of filopodia induced only by WT-GPM6a (arrows in Db, De, Eb, Ed). In E, the diagrams depict the colocalization of D4 and WT-GPM6a but the lack of colocalization of Δpal-GPM6a and D4. Therefore, in Δpal-GPM6a-transfected cells, D4 was diffusely distributed and was not concentrated around Δpal-GPM6a. Scale bars: Da, Db, Dd, De, 10 μm; Ea-Ed, 2 μm.

Because lipid rafts were originally defined as cholesterol-enriched membrane domains, we chose cholesterol-specific binding proteins for raft imaging. We performed colocalization analysis of GPM6a with the cholesterol indicator GFP-D4 to confirm its localization in lipid rafts (Ishitsuka et al., 2011). We investigated whether EGFP-D4, an imaging marker of membrane cholesterol and lipid rafts, specifically colocalized with transfected mCherry-wt GPM6a and -Δpal-GPM6a in COS-7 cells (Fig. 1D) or in mouse GPM6a-KO cortical neurons (Fig. 1E). WT-GPM6a, but not Δpal-GPM6a, was colocalized with D4 in the plasma membrane of COS-7 cells (Figs. 1D, 2A). After the appearance of filopodia, WT-GPM6a, but not ΔPal-GPM6a, colocalized with D4 at the tips of filopodia, where WT-GPM6a was concentrated in both COS-7 cells (Figs. 1D, 2) and in neurons (Fig. 1E). Therefore, in the case of mCherry-WT-GPM6a-transfected cells, D4 accumulated at the GPM6a-enriched domains; however, in the case of mCherry-Δpal-GPM6a-transfected cells, D4 did not accumulate in any specific region and was widely distributed on the cell surface (Figs. 1Dd–Df; E, 2). These results indicated that the cysteine clusters of GPM6a that were mutated in mCherry-Δpal-GPM6a (Fig. 1A) were necessary for its accumulation in functional lipid rafts and that the GPM6a molecule itself clustered the cholesterol-rich domains.

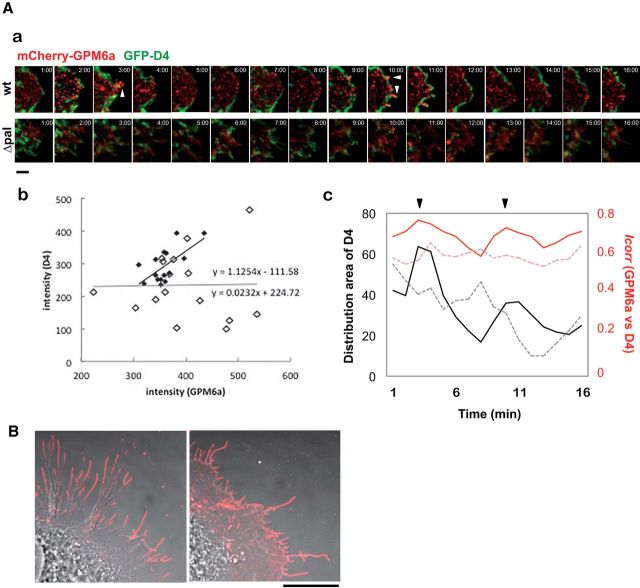

Figure 2.

GPM6a assembles and clusters cholesterol via its palmitoylation. A, GPM6a and D4 are synchronously distributed on the membrane. Aa, Sixteen sequential images (1 min per frame) of an EGFP-D4 (green)-labeled COS-7 cell expressing mCherry-WT- or Δpal-GPM6a (red). Arrowheads indicate filopodia protruding sites. Scale bar, 5 μm. Ab, Quantitative correlation of EGFP-D4 fluorescent intensities with those of mCherry-wt- (filled diamonds) or Δpal-GPM6a (open diamonds) in Aa. The regression lines and formulas are shown. Ac, Chronological changes in the distribution area of EGFP-D4 (black) and in the correlation index between GPM6a and D4 (red). These changes were synchronized in the cells expressing mCherry-wt- GPM6a (solid line), but not in cells expressing Δpal-GPM6a (dotted line). Arrowheads indicate the time at which the filopodia protruded in Aa. B, Cell-surface distribution of WT-GPM6a or ΔPal-GPM6a expressed in COS-7 cells. To observe GPM6a on the specifically cell surface, the cells were fixed but not permeabilized and immunostained with an anti-GPM6a, and Ab with an epitope that is within the extracellular domain of GPM6a. The WT-GPM6a was specifically localized on the surface of filopodia (arrow), but ΔPal-GPM6a was more broadly distributed. Scale bar, 20 μm.

GPM6a in lipid rafts is asymmetrically accumulated in the neurons at stage 1 in response to LN

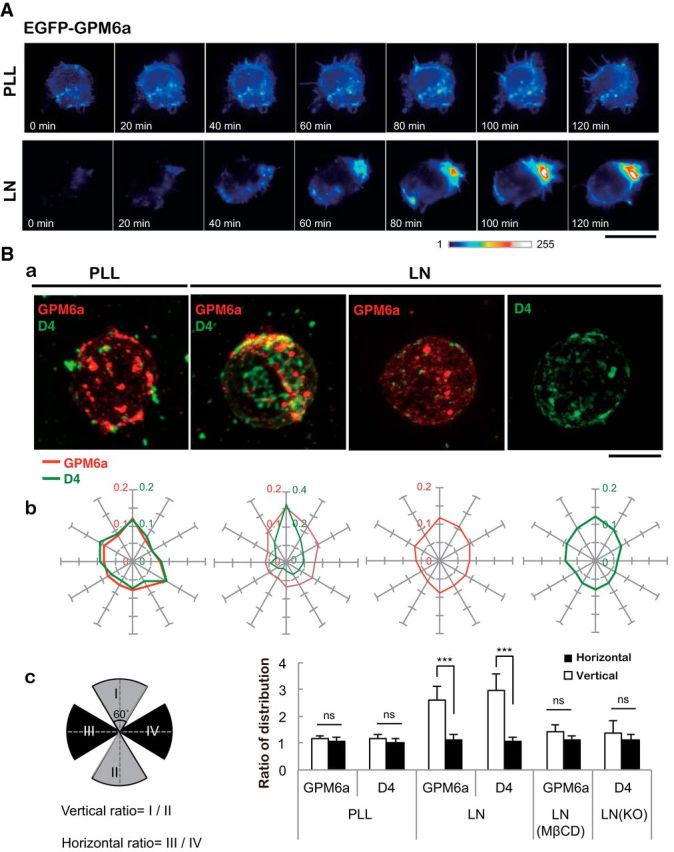

We next investigated whether the GPM6a in lipid rafts is involved in the formation of neuronal processes using a mouse cortical neuron model. Because GPM6a is a plasma membrane protein (Möbius et al., 2008) and its expression is known to increase after neuronal differentiation (Michibata et al., 2008), we hypothesized that GPM6a might be involved in neuronal shape formation in response to extracellular stimuli. To examine this hypothesis, we performed live-cell imaging of changes in the distribution of cellular GPM6a at an early stage of neuronal process formation using mouse cortical neurons. We compared GFP-GPM6a distribution in neurons cultured on a substrate of LN, which is an endogenous extracellular matrix protein, or on PLL, which is an artificial substrate for cell culture (Fig. 3A). When the neurons were plated on LN, but not when plated on PLL, EGFP-GPM6a rapidly asymmetrically accumulated in the plasma membrane within 30 min after plating at a stage corresponding to stage 1 of neuronal polarity determination (Fig. 3A; Dotti et al., 1988; Takano et al., 2015).

Figure 3.

Asymmetrical assembly of GPM6a induced by LN and its effects on clustering of the cholesterol-rich membrane domain. A, Time-lapse imaging of EGFP-GPM6a overexpressed in E16 cortical neurons over 2 h after plating. The fluorescence intensities of EGFP-GPM6a are shown as pseudocolors. Note that EGFP-GPM6a was asymmetrically assembled at 1 h after plating of the neurons on LN, but not on PLL. Scale bar, 20 μm. B, Correlation between the localization of GPM6a and cholesterol-rich membrane domains. Ba, mCherry-tagged WT-GPM6a (wt GPM6a; red) was overexpressed in GPM6a-KO cortical neurons and was plated on PLL or LN in the absence or presence of MβCD. Before plating, these unfixed GPM6a-overexpressing cells or the nontransfected GPM6a-KO cells were labeled with EGFP-D4 (green). At 1 h after plating the distribution of mCherry-GPM6a and EGFP-D4 was observed. Bb, Cumulative angular probability distribution of mCherry-GPM6a (red) and EGFP-D4 (green) in the cortical neurons (see Materials and Methods). Bc, Ratios of the fluorescence intensities for GPM6a and D4 in the areas of the vertical (I to II) or horizontal axes (III to IV) are shown. The section of the highest intensity was defined as 0 degrees. In Bb and Bc, asymmetric localization of mCherry-GPM6a and EGFP-D4 was specifically observed in neurons on LN and was inhibited by either the depletion of cholesterol (MβCD) or by the lack of GPM6a expression (GPM6a-KO), respectively. Scale bar, 10 μm. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 20; two-tailed t test; vertical vs horizontal; LN-GPM6a, 2.59 ± 0.52 vs 1.10 ± 0.21; LN-D4, 2.96 ± 0.62 vs 1.08 ± 0.16). ***p < 0.001.

Next, we analyzed the cellular localization of the labeled GPM6a in these cells by comparing it with that of D4-binding. On PLL, GPM6a was colocalized with D4 (Fig. 3Ba); however, both of these molecules displayed a symmetric cellular distribution, which was defined based on determination of the angular probability distribution index (Fig. 3Bb; see Materials and Methods). In contrast, on LN, D4 and GPM6a were colocalized asymmetrically (Fig. 3Ba,Bb), corresponding to the observed distribution of GPM6a in Figure 3A. Neurons devoid of cholesterol as a result of MβCD treatment or devoid of GPM6a (GPM6KO neurons) displayed symmetrical distribution of GPM6a and D4, respectively (Fig. 3Ba,Bb). Quantification of the distribution of these molecules in these experiments confirmed the above results (Fig. 3Bc).

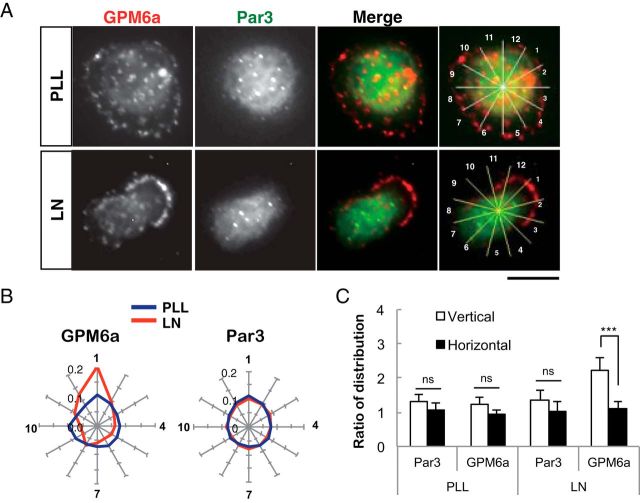

Intriguingly, Par3, a typical determinant of cellular polarity (Shi et al., 2003), did not exhibit a similar directional distribution at stage 1 on LN (Fig. 4A–C). These results suggested that GMP6a was distributed asymmetrically even at stage 1 in response to LN, before Par 3 asymmetric redistribution. These results suggested that GPM6a is accumulated in lipid rafts in response to LN at the time before neurite outgrowth starts (Dotti et al., 1988; Takano et al., 2015).

Figure 4.

Asymmetric localization of GPM6a at stage 1 is before that of Par3. A, LN induced the asymmetric localization of GPM6a but not of Par3 in stage 1 neurons. Immunofluorescence analysis of the localization of endogenous GPM6a (red) and Par3 (green) in cortical neurons cultured on PLL or LN 30 min after plating (stage 1). GPM6a but not Par3 was asymmetrically localized at this stage. Scale bars, 10 μm. B, C, Cumulative angular probability distribution of the immunofluorescence of GPM6a (red) and Par3 (green) that is shown in A in stage 1 cortical neurons on PLL (blue) or LN (red).

Lipid rafts are necessary for the formation and concentration of the GPM6a-Rufy3-Rap2-STEF/Tiam2 complex

The above results suggested the possibility that GPM6a has a potential role in neurite outgrowth that might be mediated by accumulation of its downstream signaling molecules in lipid rafts in response to LN. To investigate such molecules, we searched our previous proteomic analysis of growth cone membrane proteins (Nozumi et al., 2009; Igarashi., 2014) for the candidate proteins (Table 2) and identified Rufy3 (also known as Rap2-interacting protein X or Singar1; Kukimoto-Niino et al., 2006; Mori et al., 2007) as one such protein. Rufy3 is prominently referenced among adapter proteins for small G-proteins in the growth cone (Nozumi et al., 2009). Rufy3 interacts with Rap2 (Kukimoto-Niino et al., 2006), which is a member of the small GTPase Ras family (Ohba et al., 2000) and is a major Ras family member in the growth cone membrane, as revealed by proteomics analysis (Nozumi et al., 2009).

Immunoprecipitation of GPM6a from isolated growth cones resulted in coprecipitation of rufy3 and Rap2, showing the presence of a GPM6a-Rufy3-Rap2 ternary complex (Fig. 5A). We further examined these protein interactions in pull-down experiments using EGFP-GPM6a mutant/DM20 (a molecule related to GPM6a; Sato et al., 2011) chimeric proteins and myc-Rufy3 expressed in COS-7 cells. We showed that the Rufy3-binding site on GPM6a is located in its C-terminal region (Fig. 5B). In addition, in pull-down experiments with EGFP-Rufy3 and FLAG-Rap2, we demonstrated that the active form (GTP-bound, i.e., V12G constitutively active mutant) of Rap2 specifically binds Rufy3 (Fig. 5C). Immunofluorescent staining of endogenous proteins in mouse neurons indicated that the colocalization of these three proteins and their asymmetrical distribution at stage 1 of neurite formation occurred in an LN-dependent manner and that PLL did not induce such effects (Fig. 5D,E).

We next searched for Rap2-binding proteins and identified a neuronal Rac GEF (Tiam2/STEF; Matsuo et al., 2002; Nishimura et al., 2005) as a Rap-2 binding partner. In coimmunoprecipitation experiments using tagged purified proteins, we confirmed that this interaction occurs when Rap2 is present as a GTP-bound form (Fig. 5F). We further analyzed the distribution of these protein complex members in the DRM fractions of mouse brains using Western blotting and determined that endogenous Rufy3, Rap2, and Tiam2/STEF were concentrated in the DRM fractions, along with GPM6a and a LN receptor, β1 integrin (Fig. 5G).

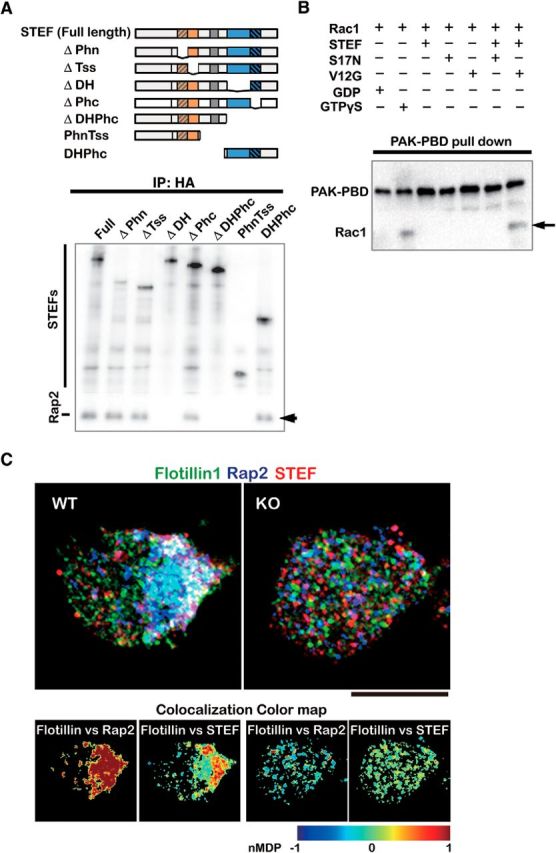

In further coimmunoprecipitation experiments using HA-tagged STEF mutants and FLAG-Rap2, we identified the DHPHc domain of Tiam2/STEF as a Rap2-binding site (Fig. 6A). Because, in addition to Tiam2/STEF (Nishimura et al., 2005), Rac1, which is a substrate of STEF/Tiam2 (Matsuo et al., 2002), is also a polarity determinant that functions in cytoskeletal rearrangement (Cáceres et al., 2012), we investigated whether the Rap2-Tiam2/STEF interaction activates Rac1. Coprecipitation experiments of HA-STEF with wild-type Rac1 and Rap2 activity mutants confirmed that this was the case (Fig. 6B). Immunofluorescent experiments using WT and KO mouse cortical neurons indicated that endogenous Rap2 and STEF were colocalized at stage 1 in a GPM6a-dependent manner and that both Rap2 and that STEF colocalized with endogenous flotillin 1, suggesting their localization in DRMs (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Interaction of Rap2-Tiam2/STEF activates the Rac1 GEF activity of Tiam2/STEF and these signaling proteins colocalize with flotillin1 via GPM6a. A, Rap2-binding sites in Tiam2/STEF. Top, HA-tagged mutants of Tiam2/STEF used for the Rap2 binding assay. Bottom, Determination of the Rap2-binding domain of Tiam2/STEF for Rac1 activation. Full-length or deletion mutants of HA-STEF were coexpressed with Flag-Rap2 in COS-7 cells. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag and anti-HA antibodies. Flag-Rap2 that coprecipitated with HA-STEF is indicated by an arrow. B, GTP-Rap2 activated the Rac1-GEF activity of Tiam2/STEF. Myc-tagged Rac1 was preincubated with either DN (S17) or CA (V12) Rap2 and HA-STEF. Activated Rac1 was pulled down using PAK-PBD immobilized to beads and was analyzed using Western blotting (arrow). C, Representative triple immunostaining of the localization of endogenous flotillin1 (green), Rap2 (blue), and Tiam2/STEF (red) in WT or GPM6aKO cortical neurons. nMDP values (see also Fig. 7D and Materials and Methods) indicate that flotillin1 colocalized with Rap2 or Tiam2/STEF in the WT neuron, but not in the GPM6aKO neuron. Scale bar, 10 μm.

These data conclusively show that these signaling proteins downstream of GPM6a accumulated in lipid rafts in an LN- and GPM6a-dependent manner.

Signaling molecules downstream of GPM6a colocalize with the lipid raft marker D4 at stage 1 of neurite formation

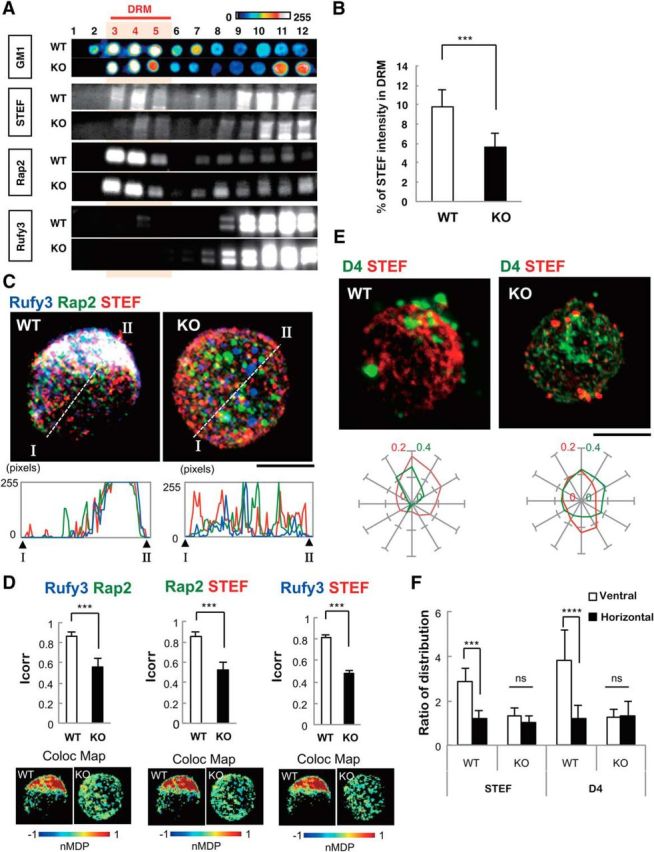

To further confirm the GPM6a dependency of the accumulation of these signaling proteins in lipid rafts, we used Western blotting to analyze the enrichment of these three GPM6a-downstream signaling proteins in the DRM fraction of WT or GPM6a-KO mouse brains. All three proteins localized in DRMs in a GPM6a-dependent manner (Fig. 7A,B), indicating that they function in lipid rafts in the presence of GPM6a.

Figure 7.

Loss of GPM6a disrupts the assembly of both the downstream proteins of GPM6a and the cholesterol-rich membrane domain. A, Distribution of Rap2, Rufy3, and Tiam2/STEF in the DRM fraction of WT or GPM6a-KO mouse brains as assessed using Western blotting. GM1 ganglioside was labeled using CtxB as a lipid raft marker. Concentrations are shown using pseudocolor images. B, Quantification of STEF expression in DRM fractions of WT and GPM6a-KO cells (see A). Data are shown as means ± SD % (n = 5; two-tailed t test; WT 9.776 ± 1.78 vs GPM6a-KO 5.6 ± 1.44). ***p < 0.001. C, Immunofluorescent staining of endogenous Tiam2/STEF (red), Rap2 (green), and Rufy3(blue) in WT and GPM6a-KO cortical neurons at 30 min after plating on LN (top, bar, 10 μm). The detailed fluorescent profiles of each fluorescent image along the lines I-II are shown (bottom). D, Colocalization of endogenous Rufy3 and Rap2, Rap2 and Tiam2/STEF, or Rufy3 and STEF in the WT and GPM6a-KO neurons are shown as the mean correlation index (Icorr, top) and the color map of the nMDP (bottom). The fluorescent punctate pattern of Tiam2/STEF, Rap2, and Rufy3 staining was asymmetrically and synchronously distributed in WT neurons, but not in GPM6a-KO neurons. ***p < 0.001. E, Correlation between the clustering of EGFP-D4 labeling and the asymmetric assembly of Tiam2/STEF. Top, Either WT or GPM6a-KO cortical neurons were grown on LN for 30 min and live cells were then stained with EGFP-D4 (green). The cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and immunostained with anti-Tiam2/STEF antibodies (red). Scale bar, 10 μm. Bottom, Cumulative angular probability distribution of the fluorescence of Tiam2/STEF (red) and D4 (green) in the top panels. F, Ratio of the fluorescence intensities of Tiam2/STEF and D4 on vertical or horizontal axes is shown. The fluorescence of Tiam2/STEF and D4 show asymmetric and synchronous localization in WT, but not in GPM6a-KO cortical neurons. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 20 for each; two-tailed t test; vertical vs horizontal; Tiam2/STEF in WT 2.89 ± 0.59 vs 1.19 ± 0.36; D4 in WT 3.85 ± 1.33 vs 1.22 ± 0.59). ***p < 0.001.

Immunofluorescence analysis indicated that these three proteins colocalized with one another in WT neurons at stage 1 of neurite formation, but not in GPM6a-KO neurons (Fig. 7C), suggesting that Rufy3, Rap2, and STEF functioned in a GPM6a-dependent manner. The colocalization of any two of these three proteins was higher in the presence of GPM6a than in its absence (Fig. 7D). We also examined the localization of STEF after the addition of D4 to cortical neurons. EGFP-D4 binds to cholesterol, is concentrated in lipid rafts, and fluorescently labels rafts (Fig. 7E). As shown above in Figure 3G, STEF/Tiam2 is localized in the DRM fraction that represents lipid rafts. D4 and STEF were both highly concentrated in the axon-protruding site in WT neurons at stage 1 (Fig. 7E), but not in GPM6a-KO neurons in which D4 and STEF/Tiam2 were diffusely distributed in the cell membrane (Fig. 7E,F). These combined results indicated that the three GPM6a downstream signaling components are aggregated in lipid rafts in a GPM6a-dependent manner in stage 1 neurons.

GPM6a determines neuronal polarity in response to external signals

We hypothesized that GPM6a and its downstream signaling complex in live neurons might be stimulated by intrinsic extracellular signals such as LN. In particular, we focused on the possibility that they are involved in neuronal polarity determination based on previous reports. Therefore, Rufy3 and Tiam2/STEF are reported to be involved in the cell-autonomous polarity determination of neurons (Nishimura et al., 2005; Mori et al., 2007), and Rap2 is involved in the polarity of intestinal cells (Gloerich et al., 2012). To examine this possibility, we compared the effect of PLL, which is frequently used in studies of neuronal polarity, with that of LN on the GPM6a-dependent localization of these proteins in the development of mouse neuronal polarity.

In the in vitro model of neuronal polarity determination, neurite outgrowth progresses from developmental stage 1 to stage 2 (with multiple minor processes) and finally to stage 3 (axon determination and growth) and, ultimately, the neurons form dendrites at stage 4 and synapses at stage 5 (Dotti et al., 1988; Fig. 8A).

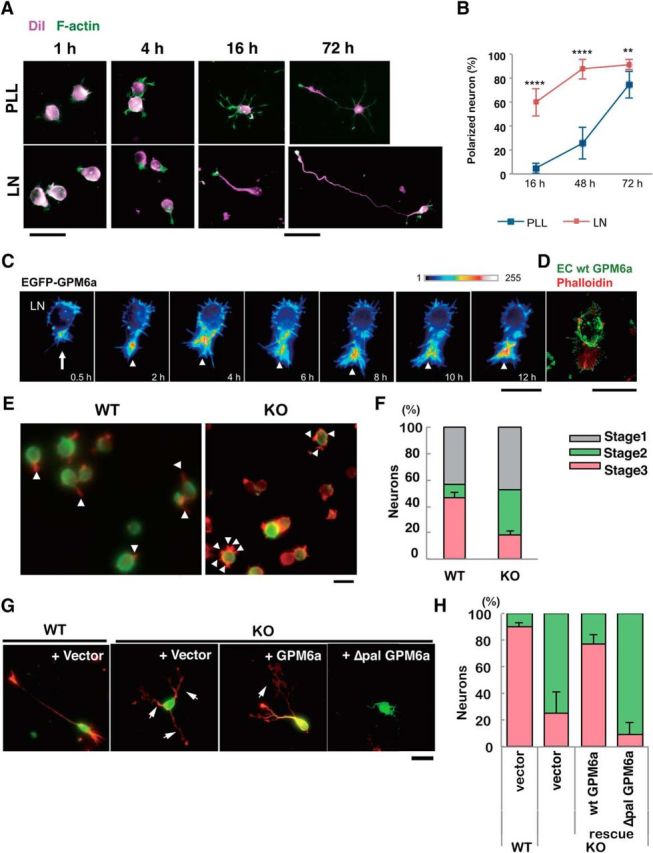

Figure 8.

Palmitoylation of GPM6a is essential for stage 1 neuronal polarity determination facilitated by LN. A, B, Comparison of the effects of LN (bottom) and PLL (top) on the time course of neuronal polarity determination. A, Neurons derived from mouse cortices were cultured on PLL or LN for 4, 16, or 72 h. The plasma membrane (magenta) and F-actin (green) were stained using DiI and phalloidin, respectively. A single neurite that eventually became an axon was observed; however, such a neuron was protruded after only 4 h on LN, but was not protruded after 4 h on PLL. Note that the neurons on LN skip the multipolar stage known as stage 2. B, Time-dependent changes in the percentage of polarized neurons on LN or PLL. Neurons with a major neurite that was at least twice as long as the other neurites were deemed polarized neurons. The proportions of polarized neurons on LN versus PLL were significantly different at all time points (****p < 0.0001 at 16 or 48 h; **p < 0.01 at 72 h). Two-way factorial ANOVA with Tukey's multiple-comparisons test; data points are means ± SD % (n = 100 from five distinct preparations). C, Time-lapse imaging over 12 h of the localization of EGFP-GPM6a expressed in mouse cortical neurons on LN. The fluorescence intensities of EGFP-GPM6a are shown as a pseudocolor. A single neurite protruded from the hot spot area of EGFP-GPM6a (arrow). EGFP-GPM6a was continuously localized at the growth cone (arrowheads). D, Growth cone (arrowhead) protruded from the GPM6a-enriched membrane area (arrow) in cortical neurons cultured for 30 min on LN. The cells were stained with the GPM6a Ab (extracellular epitope) (green) and phalloidin (red) without and with membrane permeabilization, respectively. Scale bars, 20 μm. E, F, Determination of neuronal polarity on LN was inhibited in GPM6a-KO cortical neurons. E, Representative neurons from WT or GPM6a-KO mice that were plated on LN for 4 h. Arrowheads indicate neurites. Note that the GPM6a-KO neurons had multiple neurites, but that the WT neurons had a single neurite. Fixed neurites were permeabilized and stained for F-actin using phalloidin (red) and for microtubules using tubulin βIII Ab (green). Scale bar, 20 μm. F, Percentage of neurons at stage 1, 2, or 3 in neurons from WT or GPM6a-KO mice that were plated on LN. Categorization of the stage of cortical neuron formation at 4 h after plating as stage 1 (gray), stage 2 (blue), and stage 3 neurons (red) was based upon their cell polarity (n = 50 neurons for each different group). One-way ANOVA data with Tukey's multiple-comparisons test (mean ± SD %; stage 3 neurons: LN-wt 46.2 ± 4.2 vs LN-M6aKO 18.3 ± 3.4). ****p < 0.0001. G, H, Neuronal cell polarity rescue experiment in GPM6a-KO neurons. EGFP-tagged WT-GPM6a or Δpal-GPM6a was transfected into GPM6a-KO cortical neurons. G, Neurons were observed at 72 h after plating on PLL or LN. The cortical neurons were stained for F-actin using phalloidin (red) and for EGFP using anti-EGFP Ab (green). Arrows indicate axons. EGFP-tagged GPM6a rescued neurite formation, whereas the mutant GPM6a lacked the ability to rescue neurite formation in GPM6a-KO neurons. Scale bar, 20 μm. H, Cortical neurons derived from WT or GPM6a-KO mice after plating on LN were classified according to their polarity (Fig. 5F) and the percentage of each type is shown (n = 50 neurons for each different group; percentage of polarized neurons; values are means ± SD). We compared four groups: WT neurons + vector (EGFP), GPM6-KO neurons + vector (EGFP), GPM6a-KO neurons + EGFP-GPM6a, and GPM6a-KO neurons + EGFP-Δpal GPM6a. Data (percentages of the stage 3 neurons) were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple-comparisons test (n = 50 neurons in each different group; percentage of polarized neuron; means ± SD; WT + vector 90.1 ± 3.3 vs GPM6a-KO + vector 25.0 ± 16.6, ***p < 0.001; GPM6a-KO + vector vs GPM6a-KO + GPM6a 77.2 ± 6.8, *p < 0.05; WT + vector vs GPM6a-KO + ΔPal-GPM6a 9.7 ± 8.7, ****p < 0.0001; GPM6a-KO + GPM6a vs GPM6a-KO + ΔPal-GPM6a, ***p < 0.001).

Analysis of neuronal cells stained with the fluorescent tracer DiL and F-actin over time indicated that LN-dependent neuronal polarity was established significantly sooner than PLL-dependent neuronal polarity (Fig. 8A,B). Therefore, when plated on LN, axons were formed within 4 h, whereas cortical neurons plated on PLL remained at stage 2 for several hours after plating, a state in which the neurons exhibited multiple shorter processes with no distinctive axonal process (Fig. 8A,B).

Immunofluorescence imaging analysis of mouse cortical neurons transfected with EGFP-GPM6a showed that LN induced the enrichment of GPM6a at the site of neurite origin during stages 1–3 (Fig. 8C,D). LN-dependent polarity determination was GPM6a dependent, as determined by analysis of cortical neurons from WT and GPM6a KO mice (Fig. 8E,F), and was GPM6a palmitoylation dependent, as determined by comparing GPM6aKO cortical neurons transfected with WT-GPM6a or Δpal-GPM6a (Fig. 8G,H).

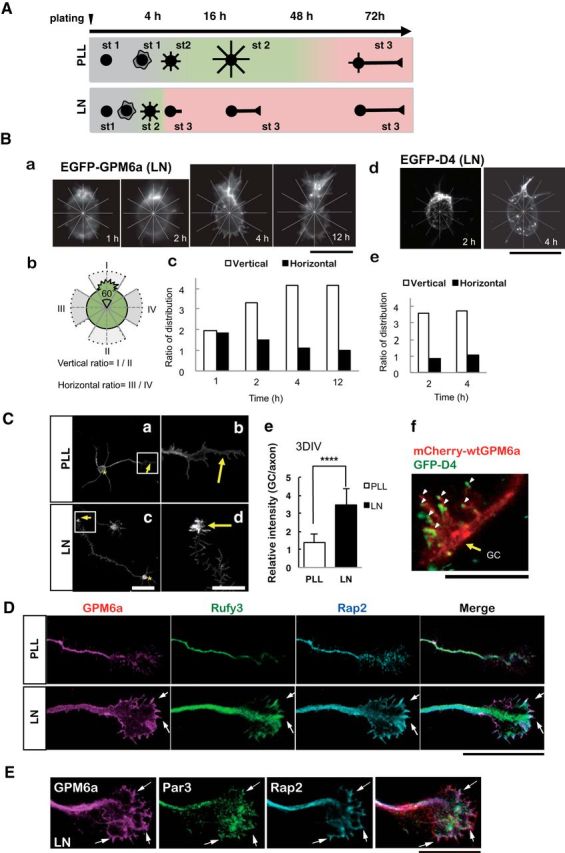

We summarized the polarity determination processes of the cortical neurons on LN or PLL (Fig. 9A). Analysis of the WT neurons transfected with EGFP-WT-GPM6a or labeled with EGFP-D4 (Fig. 9B,Cf) or of endogenous GPM6a (Fig. 9Ca–Ce, D) indicated the specific localization of GPM6a in lipid rafts in growth cones. At stage 3, endogenous GPM6a, Rufy3, and Rap2 were highly concentrated in the growth cone on LN, as well as Par3, but not on PLL (Fig. 9C–E). These results suggest that LN-induced facilitation of neuronal polarity determination is GPM6a-palmitoylation dependent (i.e., is mediated through GPM6a accumulation of lipid rafts) and that GPM6a downstream signaling molecules colocalize with GPM6a. In particular, throughout neurite formation, GPM6a was localized at the tip of the neuronal protrusion, from the site of the neurite origin at stage 1 to the growth cone at stage 3 (Figs. 8C, 9B).

Figure 9.

Polarity determination of stage 1 of neuronal formation is facilitated in neurons plated on LN; GPM6a, cholesterol, and the GPM6a-downstream signaling complex are enriched at the growth cone. A, Schematic models of the neuronal polarity determination time course in neurons plated on PLL or LN. The diagrams show the representative neuron shapes at each time point. Developmental stages of the neurons were morphologically defined according to Dotti's definition (Dotti et al., 1988); i.e., stage 1: cells with no neurite (gray); stage 2, multipolar cells (green); and stage 3: polarized cells (pink). In the cells plated on PLL, the neuronal stage changed from 1 to 2 four hours after plating. The neurons continued in stage 2 for up to 48 h. Between 48 and 72 h, the stage of the neurons changed from stage 2 to stage 3. In the cells plated on LN, the neurons dramatically changed from stage 1 to stage 3 between 1 and 4 h after plating and remained in stage 3 thereafter. B, Growth cone was protruded from the GPM6a- and cholesterol-enriched membrane area. Ba, Fluorescence images of EGFP-WT GPM6a in the neuron at 1, 2, 4, or 12 h after plating on LN. Scale bar, 20 μm. Bb, Image of each neuron was divided into six areas of 60 degrees (see also the radial grid in Ba), with the protruding site, or the neurite, defined as 0 degrees. A vertical line was drawn from the protruding site. A horizontal line that intersected the vertical line at the center of the cell was also drawn. The protruding area and the area directly opposite, which were bisected by the vertical line, were defined as areas I and II. The areas bisected by the horizontal line were defined as areas III and IV. Bc, Ratios of the fluorescence intensity of EGFP-WT-GPM6a in the vertical (open bars) and horizontal (filled bars) areas were calculated. Bd, Images of GFP-D4 labeling of the neuron at 2 or 4 h after plating on laminin were divided as described in Bb. Scale bar, 20 μm. Be, Ratios of the fluorescence intensity of GFP-D4 in the vertical (open bars) or horizontal (filled bars) areas were calculated. See also Figure 2B at stage 1. C, GPM6a accumulated in the growth cone at stage 3 on LN. Representative immunostained images of endogenous GPM6a in stage 3 neurons plated on PLL (Ca, Cb) or LN (Cc, Cd). Cell bodies and growth cones are indicated using asterisks and arrows, respectively. Cb, Cd, Higher-magnification images of the growth cones in the boxed areas in Ca and Cc, respectively. Scale bars: Ca, Cc, 50 μm; Cb, Cd, 20 μm. Ce, Ratio of the immunofluorescence intensity of GPM6a in the growth cone versus that of the axon. Note that GPM6a significantly accumulates in the growth cone at stage 3 in the presence of LN (n = 20). Two-tailed t test, ****p < 0.0001. Cf, Colocalization of GPM6a and cholesterol-rich membrane domains at the growth cone of neurons on LN. GPM6aKO cortical neurons overexpressing mCherry-WT-GPM6a (red) were cultured on LN for 3 d and were then stained live with EGFP-D4 (green) on LN. GC, Growth cone. Scale bar, 5 μm. D, Immunofluorescently stained endogenous GPM6a (magenta), Rufy3 (green), and Rap2 (blue) were colocalized at the peripheral (P) domain of the growth cone at stage 3 in neurons plated on LN, but not in neurons plated on PLL. The ternary complex accumulated (arrows) near the growth cone plasma membrane. Scale bar, 5 μm. E, Par3 is concentrated in the growth cone at stage 3 in GPM6a- and LN-dependent polarized neurons. Par3 (green) is colocalized with GPM6a (magenta) and Rap2 (blue), particularly in the leading edge of the growth cone (arrows; see the rightmost view, merged). Scale bar, 10 μm.

GPM6a is involved in in vivo neuronal polarization

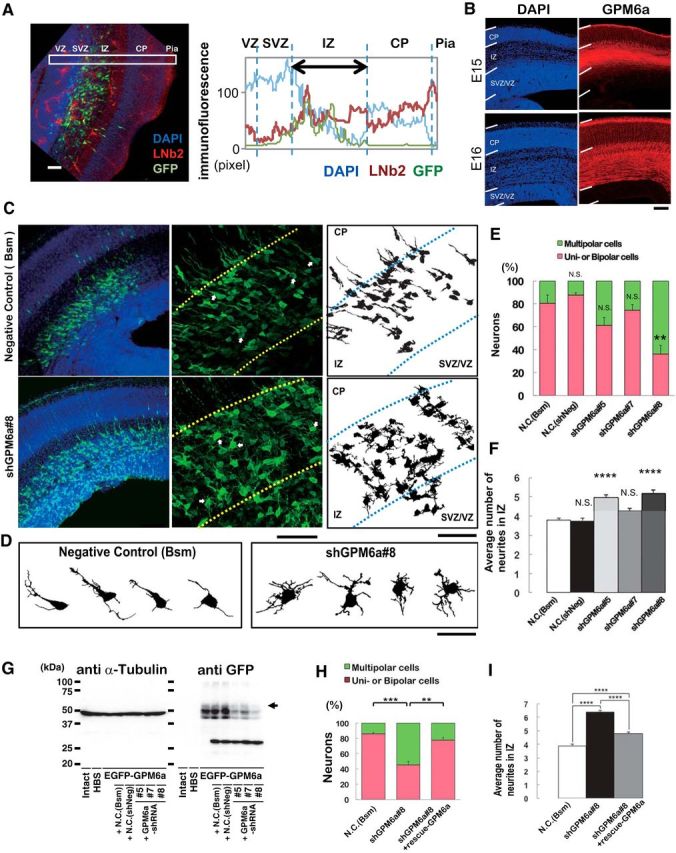

Finally, to examine the possibility that GPM6a is involved in in vivo determination of neuronal polarity, we administered RNAi against GPM6a or control RNAi in utero to mice and analyzed neuronal formation in the cortical neurons from these mice. Immunofluorescence analysis indicated that, at the normal developmental stage of E15–E16, LN was concentrated in the intermediate zone (IZ) (Fig. 10A; Lathia et al., 2007) and GPM6a was highly enriched in both neuronal cell bodies, which reside in the cortical plate, and in their axons in the IZ of the developing mouse cortex (Fig. 10B). For the in utero RNAi experiments, we designed two negative control vectors, Bsm, which lacks shRNA sequences, and shNeg, which expresses the stem loop structure without targets), and three shRNA expression vectors (shRNA #5, #7, and #8) against GPM6a for in utero administration at E14. Administration of shRNA #8 resulted in the production of neurons with multiple, short neurites similar to those at stage 2 in the IZ and showed delayed axon formation [Fig. 10C–G represent views (Fig. 10C,D), quantification (Fig. 10E,F), and validation of RNAi (Fig. 10G)]; shRNA #5 and #7 did not have significant effects after in utero administration, although they showed decreased GPM6a expression as well as #8 (Fig. 10G). We confirmed the biochemical KD effects of the shRNAs in vitro, including the effects of the negative controls, by Western blotting analysis of the expression of transfected GFP-GPM6a in COS-7 cells (Fig. 10G). The effects of shRNA#8 were rescued by the overexpression of WT-GPM6a (Fig. 10H,I). These results suggested that GPM6a is involved in neuronal polarity determination and in the subsequent axon development in vivo.

Figure 10.

GPM6a is involved in the formation of polarized axons in vivo. A, Localization of LN in the IZ of mouse embryonic brain. Left, Distribution of β2-LN (also called S-LN; red) and GFP-positive neurons (green) in a representative E16 coronal brain section. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Right, Fluorescence intensity profiles of anti-β2-LN Ab in each area in the E16 coronal brain sections in the boxed areas in the photograph are indicated. Average intensities of anti-β2-LN Ab immunofluorescence are shown. B, Immunohistochemical analysis of GPM6a in embryonic brain. GPM6a immunoreactivity (red) was mainly localized in the IMZ at stage E15 and in the cortical plate at stage E16. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). C, D, RNAi of GPM6a using in utero electroporation of shRNA against GPM6a or one of two negative control shRNA plasmids (Bsm) in mice at the developmental stage of E16. C, Left, Low magnifications of representative immunofluorescent staining of morphological transitions in E16 coronal brain sections of mice. Neurons were stained with DAPI (blue) and anti-EGFP (green) to visualize the RNAi-introduced neurons more clearly. Morphological transition was impaired by GPM6a-KD. Middle, Higher magnification of the representative morphological transition focusing on the IZ that was impaired by GPM6a-KD (top, negative control, N.C., Bsm; bottom, shGPM6a#8). Arrows indicate the neurons drawn in D (see below). Right, Drawings of representative neurons in the middle panels. Scale bar, 50 μm. D, Magnified drawing of several typical neurons in the middle panels of C. E, F, Quantitative analysis of the effect of negative controls (Bsm, shNeg) and shGPM6a (#5, #7, and #8) on neuronal morphology (classified as having unipolar/bipolar or multipolar morphology) (E) and the number of neurites in the IZ (F). **p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001 versus negative control (N.C.; Bsm) using one-way ANOVA. More than 100 EGFP-positive neurons from three to four brains were examined in each group. The data represent means ± SEM. There was rarely an effect of either of the two negative controls, the shNeg (including a nontarget sequence under the U6 promoter) and the Bsm (without shRNA-expression sequence under the U6 promoter, only restriction enzyme-targeting sequence), on the neurons. The shGPM6a#8 induced and the shGPM6a#5 had a tendency to induce multipolar cells or increase the number of neurites. G, Efficiency of each shRNA vector was examined by immunoblotting of the expression of EGFP-GPM6a transfected into COS-7 cells. The arrowhead indicates the position of GPM6a. α-tubulin was blotted as a loading control. H, I, RNAi and rescue experiment of GPM6a in vivo. The shGPM6a#8 and/or rescue-GPM6a expression vectors were electroporated into the cortex at E14, followed by fixation at E16. Quantitative analysis of RNAi and rescue effects on neuronal morphology (classified as having unipolar/bipolar or multipolar morphology) (H) and the number of neurites in the IZ (I) were measured (N.C., Bsm 85.8 ± 2.0 vs shGPM6a#8 45.4 ± 4.5, ***p < 0.001; shGPM6a#8 45.4 ± 4.5 vs shGPM6a#8 + rescue-WT-GPM6a 77.6 ± 3.6, **p < 0.005, one-way ANOVA). More than 100 EGFP-positive neurons from three to four brains were examined in each group. The data represent means ± SEM.

Discussion

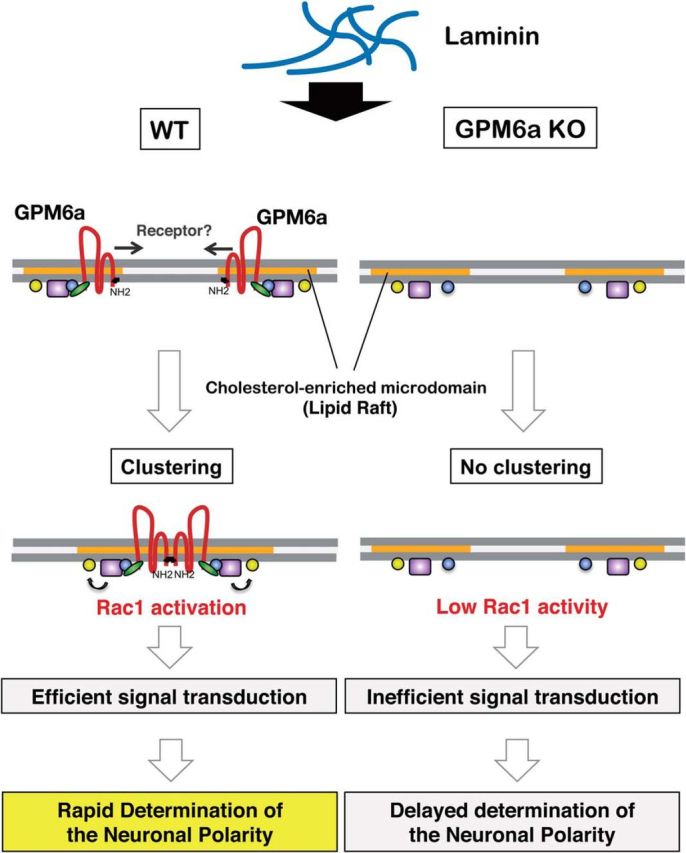

We have demonstrated that palmitoylated GPM6a cluster lipid rafts (Fig. 1) and that its asymmetrical distribution in the membrane is consistent with the site of origin of the neurite, which originates in response to LN (Figs. 3A, 8C). Not only GPM6a, but also its downstream signaling proteins such as Rufy3, Rap2, and Tiam2/STEF, each of which is involved in cellular polarization, were concentrated in lipid rafts in a GPM6a-dependent manner and facilitated polarity determination of neurons (Figs. 5, 7, 8E–H). In addition, GPM6a was localized asymmetrically at the future neurite origin site before neurite outgrowth and subsequently continued to localize at the tips of neurites and in the growth cone area after axon determination (Figs. 3A, 8B, 9B–D). In utero administration of RNAi against GPM6a showed that decreased expression of GPM6a impaired neuronal polarity (Fig. 10). These combined results suggest that GPM6a induces the clustering of neuronal lipid rafts and of signaling molecules in these rafts for more rapid determination of neuronal polarity and axon formation in response to extracellular signals (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Scheme for the molecular mechanism of neuronal polarity determination in lipid raft-like membrane domains via the GPM6a protein. GPM6a (brown) is localized in cholesterol-enriched, lipid raft membrane domains (orange) through its palmitoylation (Fig. 1). Through its interaction with Rufy3 (green), GPM6a captures active Rap2 (blue) (Fig. 3A–E) that is bound to Rac1 GEF Tiam2/STEF (purple) (Fig. 5F), which contributes to stabilization of the distribution of the determinants of neuronal polarity (i.e., Tiam2/STEF, Rap2, Rufy3) in the lipid rafts (Fig. 7). Left, In WT neurons, extracellular LN induces asymmetrical assembly of GPM6a in membranes (Fig. 2A), perhaps through a LN-receptor such as integrin (Fig. 3G), resulting in extensive clustering of GPM6a in lipid rafts (Fig. 3B) and subsequent clustering of downstream signaling molecules of GPM6a (Figs. 5D, E, 8C, D). These proteins are synchronously assembled around the cluster of lipid rafts (Figs. 6A, 8E). Because activated Rap2 activates Tiam2/STEF, a Rac1-GEF (Fig. 6B, C), the assembled Rap2 and Tiam2/STEF may robustly activate Rac1 (arrow to yellow box) in this location. As a result, neuronal polarity is rapidly determined in the neurons grown on LN (Figs. 8A, B, D, E, 11A) and a single neurite is protruded from the GPM6a-assembled area (Fig. 8C). Right, In GPM6a-KO neurons, the downstream signaling molecules of GPM6a are dispersed within the membrane and are not concentrated in lipid rafts (Fig. 7A, B). LN induces neither clustering of cholesterol-enriched domains (Fig. 3B) nor the asymmetric localization of these proteins (Figs. 6A, 7C, D), which results in functionally inefficient signal transduction. Even if these neurons are grown on LN, the cells show a much lower ability to facilitate polarity determination (Fig. 8E–H).

There are two definitions of lipid rafts: one defines rafts as membrane domains in which the membrane fluidity is lower than that in the surrounding areas and the second includes the facilitation of transduction of extracellular signals by such a membrane domain (Lingwood and Simons, 2010). Therefore, the former definition is based solely on the lipids present and the latter definition requires the involvement of signaling proteins such as GPM6a. The lipid rafts in GPM6a-WT type cells fulfilled the criteria for both definitions. However, the lipid rafts of GPM6a-KO cells only satisfied the criteria of the former definition and could not satisfy the criteria of the latter definition because there was insufficient signaling at theses rafts for LN-dependent polarity determination in these cells. Such functionally insufficient lipid rafts were rescued by palmitoylated GPM6a, indicating that functionally sufficient neuronal lipid raft domains require GPM6a.

Because the growth cone has lower levels of cholesterol and sphingolipids than the adult synaptic membrane (Igarashi et al., 1990), the efficient enrichment of signaling molecules in lipid rafts is likely to be important for the function of growth cones. We first identified the potential palmitoylation sites of GPM6a and, by microscopic analysis of WT GPM6A and its palmitoylation-deficient mutant (Fig. 1), we demonstrated that not only is palmitoylated GPM6a localized in lipid rafts, but that it also clusters these rafts (Fig. 1D,E). Palmitoylation of membrane proteins is known to be essential for their translocation to lipid rafts (Fukata and Fukata, 2010, Aicart-Ramos et al., 2011; Hornemann, 2015; Mukai et al., 2015), which is important for the transduction of extracellular signals.

We found that GPM6a functions to facilitate neuronal polarity at stage 1, responding to an extracellular signal such as LN (Fig. 8), and that it functions in an in vivo setting (Fig. 11). Although cell-autonomous signaling could determine neuronal polarity (Dotti et al., 1988) in individual single cells in vitro, according to the tug-of-war model (Lalli, 2014), it seems less likely that such signaling spontaneously occurs in in vivo polarization of neurons in an inconsistent way. Therefore, the driving of intrinsic signaling pathways such as GPM6a and its downstream signaling proteins that are concentrated in lipid rafts is likely to be important for rapid and synchronized polarity determination (Esch et al., 1999; Ménager et al., 2004; Randlett et al., 2011; Takano et al., 2015), which may explain why lipid rafts are thought to be important for axonal growth (Kamiguchi, 2006).

We have recently succeeded in the live-imaging of cholesterol (GFP-D4) and GPM6a in the growth cones of NG108-15 cells using super-resolution microscopy (Nozumi et al., 2017). These lipid raft components were retrieved by clathrin-independent endocytosis, which were found to occur spatially at a different portion from clathrin-mediated endocytosis.

Finally, because GPM6a is highly expressed and is a major palmitoylated protein in the adult neuron (Kang et al., 2008), GPM6a is thought to play important roles as a transducer of signaling in lipid rafts at the adult stage. For example, palmitoylation is involved in neuropsychiatric diseases including HD, Alzheimer's disease, and schizophrenia (Young et al., 2012). Moreover, GPM6a is known to be a substrate of the palmitoyl transferase HIP14, the dysfunctional mutant of which can be a causative gene for HD (Butland et al., 2014). In addition, GPM6a was reported to exhibit stress-responsive expression (Alfonso et al., 2005) and to be associated with depression (Boks et al., 2008); therefore, this GPM6a pathway might also be important for diseases of mood (Gregor et al., 2014). Therefore, in adults, as we have shown here that, in the developing neuron, GPM6a may act as a signaling transducer in lipid rafts that may be physiologically and/or pathologically important, including in “adult neurogenesis”-dependent synaptogenesis (Inestrosa and Varela-Nallar, 2015; Lieberwirth et al., 2016). Further investigations will clarify the importance of GPM6a in lipid rafts.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the TOGONO Comprehensive Brain Science Network on Innovative Areas (M.I.), Project Promoting Grants from Niigata University, Uehara Science Promoting Foundation (M.I.), RIKEN BioResource Center Grants for gene targeting in mice (M.I.), Tsukada Milk Company Research Grants (A.H.), and KAKENHI from MEXT of Japan (Grants 17023019, 22240040, and 24111515 to M.I. and Grants 15K06770 and 24700319 to A.H.). We thank T. Nagase (Kazusa DNA Research Institute, Kisarazu, Japan), M. Matsuda (Kyoto University, Japan), M. Hoshino (National Center for Neurology and Psychiatry, Kodaira, Japan), and T. Hirata (National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Japan) for providing materials; T. Natsume (National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology) for proteomic analysis; Sachi Matsushita (Aichi Medical University, Nagakute, Japan) for technical assistance with shRNA expression vectors; the Animal Resource Laboratory (Niigata University; Japan) for producing KO mice; K. Mineta (King Faisal University, al-Ahsa, Saudi-Arabia) for help with bioinformatic searches pertaining to RNAi; F. Nakatsu (Igarashi lab) for critical discussions; and A. Tamada (Igarashi laboratory) for advice regarding imaging techniques.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Aicart-Ramos C, Valero RA, Rodriguez-Crespo I (2011) Protein palmitoylation and subcellular trafficking. Biochim Biophys Acta 1808:2981–2994. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso J, Fernández ME, Cooper B, Flugge G, Frasch AC (2005) The stress-regulated protein M6a is a key modulator for neurite outgrowth and filopodium/spine formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:17196–17201. 10.1073/pnas.0504262102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aureli M, Grassi S, Prioni S, Sonnino S, Prinetti A (2015) Lipid membrane domains in the brain. Biochim Biophys Acta 1851:1006–1016. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom OE, Morgan JR (2011) Membrane trafficking events underlying axon repair, growth, and regeneration. Mol Cell Neurosci 48:339–348. 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boks MP, Hoogendoorn M, Jungerius BJ, Bakker SC, Sommer IE, Sinke RJ, Ophoff RA, Kahn RS (2008) Do mood symptoms subdivide the schizophrenia phenotype? Association of the GMP6A gene with a depression subgroup. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 147B:707–711. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butland SL, Sanders SS, Schmidt ME, Riechers SP, Lin DT, Martin DD, Vaid K, Graham RK, Singaraja RR, Wanker EE, Conibear E, Hayden MR (2014) The palmitoyl acyltransferase HIP14 shares a high proportion of interactors with huntingtin: implications for a role in the pathogenesis of Huntington's disease. Hum Mol Genet 23:4142–4160. 10.1093/hmg/ddu137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres A, Ye B, Dotti CG (2012) Neuronal polarity: demarcation, growth and commitment. Curr Opin Cell Biol 24:547–553. 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotti CG, Sullivan CA, Banker GA (1988) The establishment of polarity by hippocampal neurons in culture. J Neurosci 8:1454–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esch T, Lemmon V, Banker G (1999) Local presentation of substrate molecules directs axon specification by cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 19:6417–6426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukata Y, Fukata M (2010) Protein palmitoylation in neuronal development and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 11:161–175. 10.1038/nrn2788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloerich M, ten Klooster JP, Vliem MJ, Koorman T, Zwartkruis FJ, Clevers H, Bos JL (2012) Rap2A links intestinal cell polarity to brush border formation. Nat Cell Biol 14:793–801. 10.1038/ncb2537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Weeks PR, Fournier AE (2014) Neuronal cytoskeleton in synaptic plasticity and regeneration. J Neurochem 129:206–212. 10.1111/jnc.12502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor A, Kramer JM, van der Voet M, Schanze I, Uebe S, Donders R, Reis A, Schenck A, Zweier C (2014) Altered GPM6A/M6 dosage impairs cognition and causes phenotypes responsive to cholesterol in human and Drosophila. Hum Mutat 35:1495–1505. 10.1002/humu.22697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornemann T. (2015) Palmitoylation and depalmitoylation defects. J Inherit Metab Dis 38:179–186. 10.1007/s10545-014-9753-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi M. (2014) Proteomic identification of the molecular basis of mammalian CNS growth cones. Neurosci Res 88:1–15. 10.1016/j.neures.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi M, Waki H, Hirota M, Hirabayashi Y, Obata K, Ando S (1990) Differences in lipid composition between isolated growth cones from the forebrain and those from the brainstem in the fetal rat. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 51:1–9. 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90252-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inestrosa NC, Varela-Nallar L (2015) Wnt signaling in neuronal differentiation and development. Cell Tissue Res 359:215–223. 10.1007/s00441-014-1996-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishitsuka R, Saito T, Osada H, Ohno-Iwashita Y, Kobayashi T (2011) Fluorescence image screening for chemical compounds modifying cholesterol metabolism and distribution. J Lipid Res 52:2084–2094. 10.1194/jlr.D018184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiguchi H. (2006) The region-specific activities of lipid rafts during axon growth and guidance. J Neurochem 98:330–335. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03888.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang R, Wan J, Arstikaitis P, Takahashi H, Huang K, Bailey AO, Thompson JX, Roth AF, Drisdel RC, Mastro R, Green WN, Yates JR 3rd, Davis NG, El-Husseini A (2008) Neural palmitoyl-proteomics reveals dynamic synaptic palmitoylation. Nature 456:904–909. 10.1038/nature07605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukimoto-Niino M, Takagi T, Akasaka R, Murayama K, Uchikubo-Kamo T, Terada T, Inoue M, Watanabe S, Tanaka A, Hayashizaki Y, Kigawa T, Shirouzu M, Yokoyama S (2006) Crystal structure of the RUN domain of the RAP2-interacting protein x. J Biol Chem 281:31843–31853. 10.1074/jbc.M604960200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalli G. (2014) Regulation of neuronal polarity. Exp Cell Res 328:267–275. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.07.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lathia JD, Patton B, Eckley DM, Magnus T, Mughal MR, Sasaki T, Caldwell MA, Rao MS, Mattson MP, ffrench-Constant C (2007) Patterns of laminins and integrins in the embryonic ventricular zone of the CNS. J Comp Neurol 505:630–643. 10.1002/cne.21520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberwirth C, Pan Y, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Wang Z (2016) Hippocampal adult neurogenesis: Its regulation and potential role in spatial learning and memory. Brain Res 1644:127–140. 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingwood D, Simons K (2010) Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science 327:46–50. 10.1126/science.1174621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo N, Hoshino M, Yoshizawa M, Nabeshima Y (2002) Characterization of STEF, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rac1, required for neurite growth. J Biol Chem 277:2860–2868. 10.1074/jbc.M106186200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ménager C, Arimura N, Fukata Y, Kaibuchi K (2004) PIP3 is involved in neuronal polarization and axon formation. J Neurochem 89:109–118. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2004.02302.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michibata H, Okuno T, Konishi N, Wakimoto K, Kyono K, Aoki K, Kondo Y, Takata K, Kitamura Y, Taniguchi T (2008) Inhibition of mouse GPM6A expression leads to decreased differentiation of neurons derived from mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 17:641–651. 10.1089/scd.2008.0088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mita S, de Monasterio-Schrader P, Fünfschilling U, Kawasaki T, Mizuno H, Iwasato T, Nave KA, Werner HB, Hirata T (2015) Transcallosal projections require glycoprotein M6-dependent neurite growth and guidance. Cereb Cortex 25:4111–4125. 10.1093/cercor/bhu129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möbius W, Patzig J, Nave KA, Werner HB (2008) Phylogeny of proteolipid proteins: divergence, constraints, and the evolution of novel functions in myelination and neuroprotection. Neuron Glia Biol 4:111–127. 10.1017/S1740925X0900009X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Wada T, Suzuki T, Kubota Y, Inagaki N (2007) Singar1, a novel RUN domain-containing protein, suppresses formation of surplus axons for neuronal polarity. J Biol Chem 282:19884–19893. 10.1074/jbc.M700770200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai J, Tamura M, Fénelon K, Rosen AM, Spellman TJ, Kang R, MacDermott AB, Karayiorgou M, Gordon JA, Gogos JA (2015) Molecular substrates of altered axonal growth and brain connectivity in a mouse model of schizophrenia. Neuron 86:680–695. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namba T, Kibe Y, Funahashi Y, Nakamuta S, Takano T, Ueno T, Shimada A, Kozawa S, Okamoto M, Shimoda Y, Oda K, Wada Y, Masuda T, Sakakibara A, Igarashi M, Miyata T, Faivre-Sarrailh C, Takeuchi K, Kaibuchi K (2014) Pioneering axons regulate neuronal polarization in the developing cerebral cortex. Neuron 81:814–829. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Yamaguchi T, Kato K, Yoshizawa M, Nabeshima Y, Ohno S, Hoshino M, Kaibuchi K (2005) PAR-6-PAR-3 mediates Cdc42-induced Rac activation through the Rac GEFs STEF/Tiam1. Nat Cell Biol 7:270–277. 10.1038/ncb1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozumi M, Togano T, Takahashi-Niki K, Lu J, Honda A, Taoka M, Shinkawa T, Koga H, Takeuchi K, Isobe T, Igarashi M (2009) Identification of functional marker proteins in the mammalian growth cone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:17211–17216. 10.1073/pnas.0904092106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozumi M, Nakatsu F, Katoh K, Igarashi M (2017) Coordinated movement of vesicles and actin bundles during nerve growth revealed by superresolution microscopy. Cell Rep 18:2203–2216. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohba Y, Mochizuki N, Matsuo K, Yamashita S, Nakaya M, Hashimoto Y, Hamaguchi M, Kurata T, Nagashima K, Matsuda M (2000) Rap2 as a slowly responding molecular switch in the Rap1 signaling cascade. Mol Cell Biol 20:6074–6083. 10.1128/mcb.20.16.6074-6083.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada K, Nishizawa K, Fukabori R, Kai N, Shiota A, Ueda M, Tsutsui Y, Sakata S, Matsushita N, Kobayashi K (2014) Enhanced flexibility of place discrimination learning by targeting striatal cholinergic interneurons. Nat Commun 5:3778. 10.1038/ncomms4778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randlett O, Poggi L, Zolessi FR, Harris WA (2011) The oriented emergence of axons from retinal ganglion cells is directed by laminin contact in vivo. Neuron 70:266–280. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Watanabe N, Fukushima N, Mita S, Hirata T (2011) Actin-independent behavior and membrane deformation exhibited by the four-transmembrane protein M6a. PLoS One 6:e26702. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]