Abstract

The ventral striatum is involved in motivated behavior. Akin to the dorsal striatum, the ventral striatum contains two parallel pathways: the striatomesencephalic pathway consisting of dopamine receptor Type 1-expressing medium spiny neurons (D1-MSNs) and the striatopallidal pathway consisting of D2-MSNs. These two genetically identified pathways are thought to encode opposing functions in motivated behavior. It has also been reported that D1/D2 genetic selectivity is not attributed to the anatomical discrimination of two pathways. We wanted to determine whether D1- and D2-MSNs in the ventral striatum functioned in an opposing manner as previous observations claimed, and whether D1/D2 selectivity corresponded to a functional segregation in motivated behavior of mice. To address this question, we focused on the lateral portion of ventral striatum as a region implicated in food-incentive, goal-directed behavior, and recorded D1 or D2-MSN activity by using a gene-encoded ratiometric Ca2+ indicator and by constructing a fiberphotometry system, and manipulated their activities via optogenetic inhibition during ongoing behaviors. We observed concurrent event-related compound Ca2+ elevations in ventrolateral D1- and D2-MSNs, especially at trial start cue-related and first lever press-related times. D1 or D2 selective optogenetic inhibition just after the trial start cue resulted in a reduction of goal-directed behavior, indicating a shared coding of motivated behavior by both populations at this time. Only D1-selective inhibition just after the first lever press resulted in the reduction of behavior, indicating D1-MSN-specific coding at that specific time. Our data did not support opposing encoding by both populations in food-incentive, goal-directed behavior.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT An opposing role of dopamine receptor Type 1 or Type 2-expressing medium spiny neurons (D1-MSNs or D2-MSNs) on striatum-mediated behaviors has been widely accepted. However, this idea has been questioned by recent reports. In the present study, we measured concurrent Ca2+ activity patterns of D1- and D2-MSNs in the ventrolateral striatum during food-incentive, goal-directed behavior in mice. According to Ca2+ activity patterns, we conducted timing-specific optogenetic inhibition of each type of MSN. We demonstrated that both D1- and D2-MSNs in the ventrolateral striatum commonly and positively encoded action initiation, whereas only D1-MSNs positively encoded sustained motivated behavior. These findings led us to reconsider the prevailing notion of a functional segregation of MSN activity in the ventral striatum.

Keywords: fiberphotometry, food-incentive goal-directed behavior, motivation, optogenetic inhibition, ventrolateral striatum, yellow cameleon

Introduction

The projection neurons of the striatum are GABAergic medium spiny neurons (MSNs), which are subdivided into two populations: the dopamine receptor Type 1-expressing (D1)- and the dopamine receptor Type 2-expressing (D2)-MSNs. These MSNs are critically involved in motor control and goal-directed motivational processes (Kreitzer and Malenka, 2008; Kravitz et al., 2010). D1- and D2-MSNs in the dorsal striatum (DS) project to distinct targets within the basal ganglia. D1-MSNs project to output nuclei of basal ganglia (substantia nigra/ventral tegmental area) directly and D2-MSNs project to the external globus pallidus, which is a relay nucleus to the output nuclei. Based on these connections, DS D1-MSNs are regarded as the striatomesencephalic pathway or direct pathway, and DS D2-MSNs are regarded as the striatopallidal pathway or indirect pathway. This clear separation of striatal circuitry may account for the neural basis of the opposing D1 vs D2 roles in the DS, initially proposed by Albin et al. (1989) in terms of motor control. That is, activation of the direct pathway facilitates movement and activation of the indirect pathway inhibits movement. Studies using D1- and D2-type-specific loss- and gain of function have supported the view of opposing roles of D1- and D2-MSNs in the DS on motor function (Kravitz et al., 2010; Durieux et al., 2012), reinforcement learning (Kravitz et al., 2012), and drug sensitization (Ferguson et al., 2011; Durieux et al., 2012).

This view has been extended to studies on the ventral striatum (VS), especially on the nucleus accumbens (NAc; the rostral VS) in a series of drug-seeking behavioral studies (Hikida et al., 2010; Lobo et al., 2010; Stefanik et al., 2013). Such an extension was supported in part by anatomical similarity; in the VS, D1-MSNs project to the ventral tegmental area (ventral mesencephalon [VM]) directly and D2-MSNs project the ventral pallidum (VP), a relay nucleus to the VM. Akin to the DS, VS D1-MSNs and D2-MSNs can be regarded as direct and indirect pathways, respectively. However, further anatomical evidence questions an exclusive D1 versus D2 separation of direct/indirect pathways in the VS (Gangarossa et al., 2013; Kupchik et al., 2015). First, half of VP neurons receive NAc D1-MSNs input, and the VP acts as an output nucleus of the basal ganglia. The former evidence contradicts the idea that D1-MSNs do not project to a relay nucleus. The latter resolved the above contradiction but gave rise to another contradiction (i.e., D2-MSNs projecting to an output nucleus directly). In addition, the former evidence points out that D1- and D2-MSNs share the same pathway from the NAc to the VP. Therefore, it is unknown whether VS-mediated behaviors, aside from drug-seeking behaviors, are encoded by D1- and D2-MSNs in an opposing or cooperative manner.

We recently demonstrated that ventrolateral striatal (VLS) D2-MSNs control motivated behavior through experiments combining cell type-specific ablation/inhibition with food-incentive, goal-directed behavior (Tsutsui-Kimura et al., 2017); toxin-mediated loss of function of the entire (from the rostral to the caudal) VLS D2-MSNs impaired motivation, and optogenetics-mediated loss of function of D2-MSNs in the middle portion of the VLS impaired motivation as well. Although the VLS is not identical to the NAc, our recent data highlighted that the VLS regulates motivated behavior. These results encouraged us to tackle the above question. We first developed a fiber photometric system to observe the activity of VLS D1- or D2-MSNs in freely moving mice and examined whether each cell type signaled in an opposing or coordinated manner during motivated behavior. We next examined the functional readout of D1- or D2-selective, activity-oriented optogenetic inhibition to determine whether D1 or D2-MSNs encode motivated behavior in an opposing or a cooperative manner.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals and approved by the Animal Research Committee of Keio University School of Medicine (approval 14027-(1)). Experiments were performed using 3- to 12-month-old male and female mice. D2-YC mice (Drd2-tTA::tetO-YCnano50 double-transgenic mice) were obtained by crossing between Drd2-tTA mice (Tsutsui-Kimura et al., 2017) and tetO-YCnano50 mice (Kanemaru et al., 2014). D2-ArchT mice (Drd2-tTA::tetO-ArchT-EGFP double-transgenic mice) were obtained by crossing between Drd2-tTA mice and tetO-ArchT-EGFP mice (Tsunematsu et al., 2013). D1-YC mice (Pde10a2-tTA::tetO-YCnano50; Adora2a-Cre triple-transgenic mice) were obtained by crossing between Pde10a2-tTA mice (Sano et al., 2008), tetO-YCnano50 mice, and Adora2a-Cre mice (Durieux et al., 2009) (see Fig. 1). D1-ArchT mice (Pde10a2-tTA::tetO-ArchT-EGFP; Adora2a-Cre triple-transgenic mice) were obtained by crossing Pde10a2-tTA mice, tetO-ArchT-EGFP mice, and Adora2a-Cre mice. The genetic background of all transgenic mice was mixed C57BL6 and 129SvEvTac.

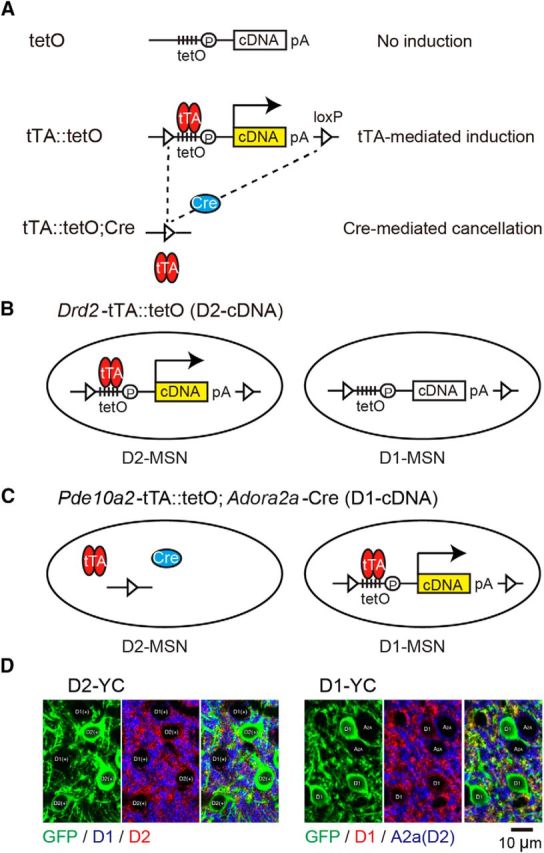

Figure 1.

Engineering of D1- or D2-MSN-specific YCnano50 or ArchT-EGFP mice. A, Gene manipulation strategies. Top, tetO cassette was inserted downstream of the Actb polyA signal in tetO knockin mice, but with no gene induction. Middle, tTA-mediated gene induction. tTA binds to the tTA-dependent promoter (tetO) and transactivates the transcription of cDNA in double-transgenic mice. Bottom, The tetO cassette was removed by crossing with Cre mice, yielding Cre recombination. tetO, Tetracycline operator; tTA, tetracycline-controlled transcriptional activator; pA, polyadenylation signal; loxP, locus of X-over P1. B, Strategy for the generation of D2-cDNA (Drd2-tTA::tetO double-transgenic) mice. Drd2-tTA induced the expression of cDNA (YCnano50 or ArchT-EGFP) in D2-MSNs, but not in D1-MSNs. C, Strategy for the generation of D1-cDNA (Pde10a2-tTA::tetO-cDNA; Adora2a-Cre triple-transgenic) mice. Pde10a2-tTA induced the expression of cDNA (YC nano50 or ArchT-EGFP) in D1-MSNs, but not in D2-MSNs by Cre-mediated removal of tetO cassette. D, Left panels, YCnano50 expression in the striatum of adult D2-YC mice. Green represents GFP indirect fluorescence of YCnano50 (left). Blue and red represent D1 and D2 receptors, respectively (middle). Right, Merged image represents that YCnano50 was selectively expressed in D2-MSNs. Right panels, YCnano50 expression in the striatum of adult D1-YC mice. Green represents GFP fluorescence of YCnano50 (left). Red and blue represent D1 and A2a receptor, respectively (middle). Right, Merged image represents that YCnano50 was selectively expressed in D1-MSNs.

The following primer sets were used in mouse genotyping: D2R-582U (5′-GCGTTTGACTAAGTTGCCAAGCTG-3′) and mtTA24L (5′-CGGAGTTGATCACCTTGGACTTGT-3′) were used for Drd2-tTA and yielded a 610 bp band; tTAup (5′-GCTGCTTAATGAGGTCGG-3′) and tTAlow (5′-CTCTGCACCTTGGTGATC-3′) were used for Pde10a2-tTA and yielded a 500 bp band; CreP1 (5′-GCCTGCATTACCGGTCGATGCAACG-3′) and CreP2 (5′-AAATCCATCGCTCGACCAGTTTAGTTACCC-3′) were used for Adora2a-Cre and yielded a band of 640 bp. Wild-type mice were negative for the above PCR products. Genotyping for tetO-YCnano50 and tetO-ArchT-EGFP was previously described (Tsunematsu et al., 2013; Kanemaru et al., 2014). While transgene induction can be turned off by administration of doxycycline, we used the system solely to achieve cell-type specificity.

Immunohistochemistry.

The method for immunohistochemistry has been described previously (Kanemaru et al., 2014). The following antibodies were used: anti-dopamine receptor Type 1 (D1) (1:1000, goat polyclonal, Frontier Institute), anti-D2 (1:1000, guinea pig polyclonal, Frontier Institute), anti-adenosine receptor Type 2a (A2a) (1:1000, guinea pig polyclonal, Frontier Institute), and anti-GFP (1:1000, rabbit polyclonal, Frontier Institute). For fluorescence microscopy, sections were treated with a mixture of species-specific secondary antibodies conjugated to AlexaFluor-488, -555, or -633 (1:1000, Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature. Fluorescent images were obtained with a confocal microscope (LSM710, Zeiss).

Surgery.

Stereotaxic surgery was performed under anesthesia with a ketamine-xylazine mixture (100 and 10 mg/kg, respectively, i.p.). For the optical measurement, animals were unilaterally (right side) implanted with an optical fiber cannula (CFMC14L05, φ 400 μm, 0.39 NA; Thorlabs) into the VLS (0.4 mm anteroposterior, 2.0 mm mediolateral from bregma, −4.0 mm dorsoventral from the skull surface), according to the atlas of Paxinos and Franklin (2004). For the optogenetic inhibition, mice were bilaterally implanted with 200 μm core diameter optical fiber cannula (0.39 NA, Thorlabs) into the VLS. For microinjection studies, mice were unilaterally (right side) implanted with 400 μm core diameter optical fiber and microinjection guide cannula (Eicom) into the VLS, with a respective 15 degree angle of insertion in the coronal plane.

Fiberphotometry.

We used a fiber photometric system to detect compound neuronal calcium fluctuations. The system was designed by Olympus Engineering (see Fig. 2A). The input light (435 nm; silver-LED, Prizmatix) was reflected off a dichroic mirror (DM455CFP; Olympus), coupled into an optical fiber (M41L01, φ 600 μm, 0.48 NA; Thorlabs) linked to a 400 μm 0.39 NA optical fiber (M79L01; Thorlabs) through a pinhole (φ 600 μm), and then delivered to an optical fiber cannula implanted into the mouse brain. LED power was <200 μW at the fiber tip. Emitted cyan and yellow fluorescence from YCnano50 was collected via an optical fiber cannula, divided by a dichroic mirror (DM515YFP; Olympus) into cyan (483/32 nm band-path filters, Semrock) and yellow (542/27 nm), and detected by each photomultiplier tube (H10722–210; Hamamatsu Photonics). The fluorescence signals in addition to TTL signals from behavioral settings were digitized by a data acquisition module (NI USB-6211; National Instruments) and simultaneously recorded by using a custom-made LabVIEW program (National Instruments). Signals were collected at a sampling frequency of 1000 Hz. The fluorescence signals were smoothed using a 100-point moving-average method.

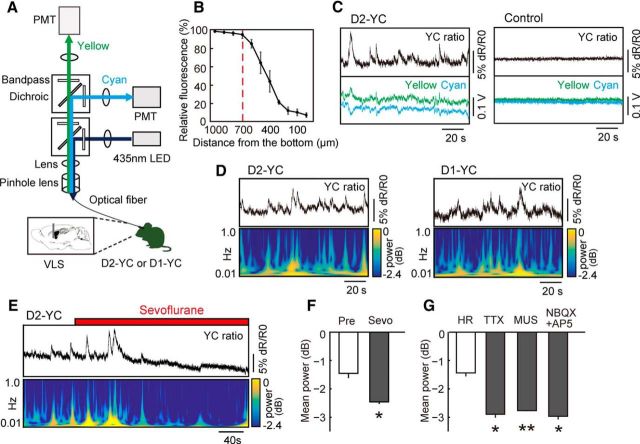

Figure 2.

Optical measurement of neuronal activity in D2- and D1-MSNs in freely moving mice. A, Schematic of fiber-photometric system. Light path for fluorescence excitation and emission is through a single multimode fiber connected to the optical fiber cannula implanted in the VLS. The fluorescence emission is separated in two by a dichroic mirror, and cyan and yellow fluorescence are corrected through bandpass filters and enhanced by photomultiplier tubes. B, Estimating the effective detection range of the fiberphotometry. When we carefully inserted the optical fiber cannula into the VLS in the fixed brain slice of a D2-YC mouse put on a black shading plate, >10% reduction of fluorescence was observed beyond the distance of 700 μm from the bottom. n = 4 slices from 2 brains. C, Example of yellow/cyan fluorescence intensity ratio (YC ratio; top) and corresponding fluorescence intensity changes of yellow and cyan fluorescence (bottom) recorded in the VLS in D2-YC (left) and wild-type control (right) mice, respectively. D, Examples of YC ratio (top) and corresponding power spectral data (bottom) in the VLS in D2-YC (left) and D1-YC (right) mice, respectively. YC ratio was recorded from a freely moving mouse in the home cage. E, The diminishment of YC ratio in the VLS of D2-YC mice under sevoflurane anesthesia. F, The effect of sevoflurane on YC ratio (power value) in the VLS of D2-YC mice. *p < 0.05, compared with pretreatment (paired t test). n = 4. G, The response of YC ratio (power value) in the VLS of D2-YC mice to microinjection of HEPES-Ringer's solution (HR), TTX, MUS, NBQX, and AP-5. *p < 0.05, compared with HR as a control (Student's t test with Bonferroni correlation). **p < 0.01, compared with HR as a control (Student's t test with Bonferroni correlation). n = 4 for each drug. Error bars indicate ± SE.

Fiberphotometry with pharmacological intervention in freely moving mice.

One week after guide cannula and optical fiber implantation targeted at the VLS, a stainless-steel microinjection cannula (CXMI-4T; Eicom) with a length of 1 mm longer than the guide cannula was inserted. The microinjection cannula was connected to a 25 μl Hamilton syringe operated by an infusion pump (Eicom). The following drugs were used: 0.64 ng/μl TTX (Wako), 1 μg/μl muscimol (MUS; Tocris Bioscience), 1 μg/μl NBQX (Tocris Bioscience), and 4 μg/μl AP-5 (Tocris Bioscience), which were dissolved in the vehicle (HEPES-Ringer's solution): 125 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES, 2 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgSO4, 10 mm glucose, pH 7.4. The microinjection volume was always 0.4 μl, given at a rate of 0.05 μl/min. After a 5 min postinjection period, the optical recording resumed.

Fixed ratio (FR) operant task.

Mice were housed individually under conditions of food restriction. Their body weights were maintained at 85% of initial body weight. Behavioral trainings and tests were performed in an aluminum operant chamber measuring W22 × D26 × H18 cm (Med Associates) under constant darkness. A food dispenser flanked by two retractable levers was located on the floor. The lever on the left side is designated as “active” (triggering delivery of a food reward), and the one on the right is “inactive” (no relation to food reward). Each trial began with the presentation of two levers (trial start [TS]). After mice pressed the active lever (lever press [LP]), the levers were retracted and one food pellet (20 mg each, dustless precision pellets, Bio-serv) was delivered as a reward (RW). After the food delivery, 30 s of intertrial interval was added, during which levers were retracted, followed by the automatic starting of the next trial. The intertrial interval allows time for mice to consume the food pellet. The session lasted 60 min or until mice received 100 food rewards. The training started with a FR-1 schedule, in which the animals obtained one food reward after each active LP. Once the animals were able to obtain 50 rewards within 60 min, the training progressed to an FR-2 schedule, in which two active LPs were needed for each RW. The training moved on to an FR-3 schedule when the animals could obtain 50 rewards in 60 min. The animals were then trained on an FR-10 schedule after they could obtain 50 rewards in 60 min for a couple of sessions. Then mice were implanted with an optic fiber cannula and were left to recover for a week. After the recovery, the mice connected with an optic fiber were trained up from the FR-1 schedule until the mice performed the FR-10 operant task under the optical measurement. On average, it took 28 d for the entire behavioral procedure, consisting of training, surgery and recovery, and retraining.

Progressive ratio (PR) operant task.

The same apparatus used in the FR task was used in the PR task. The training procedure and task sequences were the same as previously described (Tsutsui-Kimura et al., 2017). After the training was completed, the mice were implanted with optic fiber cannulas bilaterally and allowed to recover for a week. After recovery, the mice connected with a bifurcated optic fiber were trained again, and when their performance in the PR task stabilized for three consecutive sessions, we moved to the optical manipulation phase of the experiment. On average, it took 28 d for the entire behavioral procedure. The PR breakpoint was defined as an index of instrumental motivation. The time spent to complete the PR (the mean time from the first active LP to achieving the required number of active LP) was defined as an index of instrumental motivation. Percent inactive lever pressing [inactive LP/(inactive and active LP) × 100] was calculated and was defined as an index of associative learning. The latency to collect reward was defined as an index of appetite.

In vivo optical measurement of MSN activity during the FR operant tasks.

Four D2-YC and five D1-YC mice were subjected to the FR task. YC ratio (a ratio of yellow to cyan fluorescence intensity; R) in one session was detrended using cubic spline, and normalized within each trial calculating the Z score as (R − Rmean)/RSD, where Rmean and RSD were the mean and SD of the YC ratio for 5 s just before each TS.

Optogenetic inhibition during the PR operant tasks.

Six D2-ArchT and three D1-ArchT mice were subjected to the PR task under the influence of optogenetic inhibition. Before each experiment, optical fibers (Doric Lenses) were connected bilaterally into the optical cannula. Yellow (575 nm, 3 mW each at the fiber tip) or blue (475 nm, 2 mW each) light was generated by a SPECTRA 2-LCR-XA light engine (Lumencor).

Data analysis.

YC ratio and all statistics were analyzed using MATLAB (The MathWorks). The power spectral data of YC ratio was obtained by a wavelet analysis. In the pharmacological study, a power spectral profile over a 0.05–1.0 Hz window was used for analysis.

Data for all experiments were analyzed using parametric statistics with Student's t test, Student's t test with Bonferroni correction, paired t test, or paired t test with Bonferroni correction.

Results

Optical detection of compound Ca2+ signals of D1- or D2-MSNs in the VLS

To understand the temporal patterns of VLS D1- or D2-MSN activity during goal-directed, motivated behavior, we generated transgenic mice harboring a Ca2+ indicator in a D1- or D2-MSN-specific manner (Fig. 1) and developed a fiber photometric system to detect compound Ca2+ signals from the targeted cells (Fig. 2A). We used a Förster resonance energy transfer-based ratiometric gene-encoded Ca2+ indicator, called yellow cameleon (YC) nano50 (Horikawa et al., 2010), which allowed us to reduce noise levels originated from motion artifacts under physiological conditions (Kanemaru et al., 2014).

To sufficiently express the Ca2+ indicator in the targeted cell population, we took advantage of an improved tetracycline-controllable gene induction system (KENGE-tet system, e.g., tetO-YCnano50 mice) (Tanaka et al., 2012). To express YCnano50 selectively in D2-MSNs, we generated Drd2-tTA::tetO-YCnano50 double-transgenic mice (D2-YC; Fig. 1B,D). In the D2-YC striatum, 93% of D2-MSNs expressed YCnano50 and none of D1-MSNs expressed it. Striatal cholinergic interneurons expressed Drd2 mRNA; however, Drd2-tTA mice failed to express tTA in these cells (Tsutsui-Kimura et al., 2017), resulting in no YCnano50 induction in cholinergic interneurons. Outside the striatum, Drd2 mRNA positive-dopamine neurons in the midbrain expressed tTA and <1% of dopamine neurons induced YCnano50, but the direct fluorescence of YCnano50 was invisible (data not shown). Drd2 mRNA-positive neurons in the insular cortex did not express tTA and none of insular neurons induced YCnano50 (Tsutsui-Kimura et al., 2017). Among the VLS, although there might be YCnano50 positive axons of dopamine neurons, their levels were negligible.

To express it in D1-MSNs, we generated triple-transgenic mice (Pde10a2-tTA::tetO-YCnano50; Adora2a-Cre) in which Pde10a2-tTA expressed tTA in both D1- and D2-MSNs and drove tTA-mediated YCnano induction, but with D2-MSN-specific Cre expression under the control of an Adora2a promoter excised tetO cassette, resulting in D1-MSN-specific YCnano50 expression (D1-YC; Fig. 1C,D). YCnano50 was expressed by 98.1% of D1-MSNs and none of D2-MSNs (Fig. 1D). Pde10a2 gene exclusively expressed within the striatum; therefore, none of projection neurons to the striatum expressed YCnano50 in D1-YC mice.

Although fiberoptic intracellular Ca2+ recording systems have been previously developed for the use of GCaMPs (Cui et al., 2013; Gunaydin et al., 2014), we designed a new optical recording system using a ratiometric calcium indicator. Our fiber photometric system includes one light source (435 nm LED) and two photomultiplier tubes for the detection of cyan and yellow fluorescence derived from YCnano50. The compound intracellular Ca2+ signals in the VLS were measured as a ratio of yellow to cyan fluorescence intensity.

To estimate the effective detection range of our assay system, we used fixed D2-YC mouse brains. We carefully inserted the optical fiber cannula (φ 400 μm) into the VLS in a fixed coronal brain slice (>1.0 mm thickness) that was put on a black shading plate. We recorded the cyan fluorescence intensity at every sequential 100 μm depth from the top to the bottom. Because we observed more than a 10% reduction of fluorescence at a distance of 600 μm from the bottom, we estimated that the range of detection limit was at ∼700 μm depth (>600 μm) (n = 4 slices from 2 brains; Fig. 2B). We counted the number of fluorescent cells in the column (400 μm in diameter and 700 μm in height) and inferred that our system collected compound signals from ∼300 cells in D2-YC mice.

We observed a fluctuation of the yellow/cyan fluorescence intensity ratio (YC ratio) in the VLS in both freely moving D2-YC and D1-YC mice. The convex wave of YC ratio corresponded to fluctuations of anti-parallel yellow (convex) and cyan (concave) fluorescence intensities in D2-YC mice, but we did not observe the wave of YC ratio in control wild-type mice (Fig. 2C). The frequency of these YC ratios ranged mainly from 0.1 Hz to <1.0 Hz, and the duration of convex waves was typically 10–20 s (0.05–0.1 Hz) (Fig. 2D).

To confirm whether the waves of YC ratio correspond to compound neuronal activities within the VLS, we manipulated neuronal activity and measured expected outcomes. We observed that the YC ratio in the VLS was gradually diminished by sevoflurane anesthesia in D2-YC mice (Fig. 2E,F; n = 4, Pre [from −90 s to −30 s] vs sevoflurane [from 110 s to 170 s], t(3) = 4.03, p = 0.03, paired t test). In addition, the YC ratio was significantly diminished after microinjection of several inhibitors of neuronal activity, such as the action potential blocker TTX (n = 4, t(3) = 6.34, p = 0.03, paired t test with Bonferroni correction vs control of HEPES-Ringer's solution), the GABAA receptor agonist MUS (n = 4, t(3) = 9.26, p = 0.008), and the mixture of the AMPA receptor antagonist NBQX and the NMDA receptor antagonist AP-5 (NBQX + AP-5; n = 4, t(3) = 6.79, p = 0.01) (Fig. 2G). These findings indicate that the waves of YC ratio correspond to compound neuronal activities of MSNs. Hereafter, we refer to the YC ratio waves as a compound Ca2+ signal.

Similar temporal patterns of VLS D2- and D1-MSN activities during an operant task

We previously demonstrated that dysfunction of VLS D2-MSNs led to decreased motivation during an operant task (Tsutsui-Kimura et al., 2017). It remains unclear at what specific time these neurons activated during the task and whether the counterpart of these cells in the same region (VLS D1-MSNs) behaved in an opposite manner or not. To verify the timing of targeted cell activity during a task, we chose an FR-10 schedule as a food-incentive, operant task (Fig. 3A) and we recorded compound Ca2+ signals from VLS D2- or D1-MSNs separately using our optical recording setup (Fig. 3). The position of the VLS ranged from the rostral to the caudal part of the striatum. We selected the middle portion of the VLS for the recording because the optogenetic ablation of the middle portion of the VLS sufficiently produced impaired motivation (Tsutsui-Kimura et al., 2017).

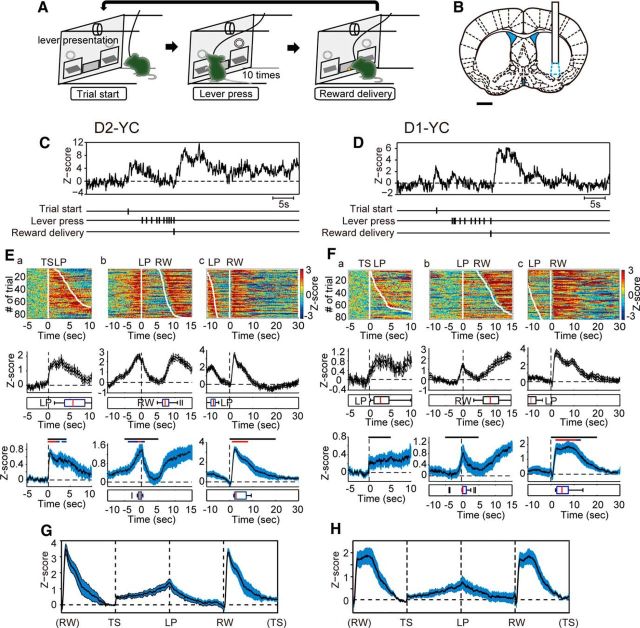

Figure 3.

Temporal changes of compound intracellular Ca2+ signals in VLS D2- and D1-MSNs during an operant task. A, Schematic illustration of the fixed ratio (FR)-10 operant task sequence. B, Recording site of Ca2+ signal of D2- or D1-MSNs in the VLS (cyan-dotted region). Scale bar, 1 mm. C, D, Representative trace of compound intracellular Ca2+ transients in VLS D2- (C) and D1-MSNs (D), respectively. Vertical ticks indicate time stamps of TS, each LP, and RW. E, F, Temporal changes of Ca2+ signals in VLS D2- (E) and D1-MSNs (F) aligned to the timing of TS (a), first LP (b), and RW (c), respectively. Top row, Color-coded compound Ca2+ signals in one representative session (85 trials, E; and 79 trials, F) sorted by TS-LP latency or LP-RW duration. Middle row, Averaged signals from the same session in the top row. Boxplot represents the timing of LP (a), RW (b), and LP (c), respectively. Bottom row, Averaged signals from all sessions of all mice (n = 12 sessions from 4 mice). Black bar represents the statistical period. Blue bar represents p < 0.05. Red bar represents p < 0.01. Paired t test with Bonferroni correction: mean Z score during 5 s just before TS vs that during each 1 s period for 5 s after TS (a), respective 5 s before and after LP (b), or 20 s after RW(c). Boxplots represent the peak of Ca2+ signal within the statistical period. G, H, Trace of averaged VLS D2- (G) and D1-MSN (H) Ca2+ signals from all sessions in which the duration between trigger points was normalized. E, G, n = 12 sessions from 4 D2-YC mice. F, H, n = 15 sessions from 5 D1-YC mice. Shadow areas represent ± SE.

Apart from Ca2+ signal dynamics seen in a freely moving situation, compound Ca2+ signals from VLS D2-MSNs exhibited a periodic pattern during the task. Transient increases of compound Ca2+ signals were observed at the initiation of every trial (TS) when both levers were automatically presented (Fig. 3Ea; n = 12 sessions, mean Z score during 5 s just before TS [Pre] vs the mean during each 1 s period for 5 s after TS, paired t test with Bonferroni correction, t(11) = 3.36–6.92, p < 0.01 [red] and p < 0.05 [blue]). After TS, the level of compound Ca2+ signals gradually increased, reached a peak at the time of the first LP (median value of TS-LP latency was 11.6 ± 2.3 s) (Fig. 3Eb; Pre vs the mean during each 1 s period for respective 5 s before and after LP, paired t test with Bonferroni correction, t(11) = 3.59–4.89, p < 0.01 [red] and p < 0.05 [blue]), and then decreased by the 10th LP. The last (10th) LP was contingent with the RW, and LP-RW duration was 10.0 ± 1.1 s (median value). A 30 second intertrial interval (RW to next TS) started at the last LP during which time mice collected a food pellet after RW. A Ca2+ surge (averaged peak time was 4.4 s after RW) was observed when mice consumed a pellet (Fig. 3Ec; Pre vs the mean during each 1 s period for 20 s after RW, paired t test with Bonferroni correction, t(11) = 4.86–12.09, p < 0.01 [red]). An averaged trace (n = 12 sessions) normalized by events clearly summarized the temporal pattern of compound VLS D2-MSN Ca2+ signals: elevation at the TS, gradual increase to the first LP, gradual decrease to the last LP, and surge right after RW (Fig. 3G).

Interestingly, we observed a similar temporal pattern of compound Ca2+ signals in VLS D1-MSNs (Fig. 3D,F,H). Ca2+ signal changes were observed at the time of TS (Fig. 3Fa; n = 15 sessions, Pre vs the mean during each 1 s period for 5 s after TS, paired t test with Bonferroni correction), and small and large peaks were observed at the first LP (median value of TS-LP latency was 4.8 ± 1.0 s) and after RW (median value of LP-RW duration was 10.3 ± 0.9 s), respectively (Fig. 3Fb,Fc; Pre vs the mean during each 1 s period for respective 5 s before and after LP, or 20 s after RW, paired t test with Bonferroni correction, t(14) = 3.22–6.70, p < 0.01 [red] and p < 0.05 [blue]). The shape of the D1-MSN Ca2+ surge seen after RW (averaged peak time was 6.2 s after RW) was different from that of D2-MSNs: the period of Ca2+ surge of D1-MSNs (10.7 ± 1.4 s, n = 15 sessions) was longer than that of D2-MSNs (9.1 ± 1.8 s, n = 12 sessions) but not statistically significant (t(25) = 0.72, p = 0.48, Student's t test). A normalized averaged trace (n = 15 sessions) demonstrated similar event-related Ca2+ dynamics in VLS D1-MSNs to those in D2-MSNs, except for a longer Ca2+ surge after RW (Fig. 3H).

Higher D2-MSN Ca2+ elevation after TS cue correlated to a higher motivated state

In our FR-10 schedule, the intertrial interval (RW to next TS) was fixed, but the latency from TS cue to first LP (TS-LP latency; Fig. 4A, blue arrow) and the duration of 10 LPs (LP-RW duration; Fig. 4A, red arrow) varied in trials. These periods can be considered as indices of motivation; mice with higher motivation displayed a shorter TS-LP latency and shorter LP-RW duration, and vice versa. We hypothesized that trials conducted under a higher motivation would be accompanied with a higher neuronal activation.

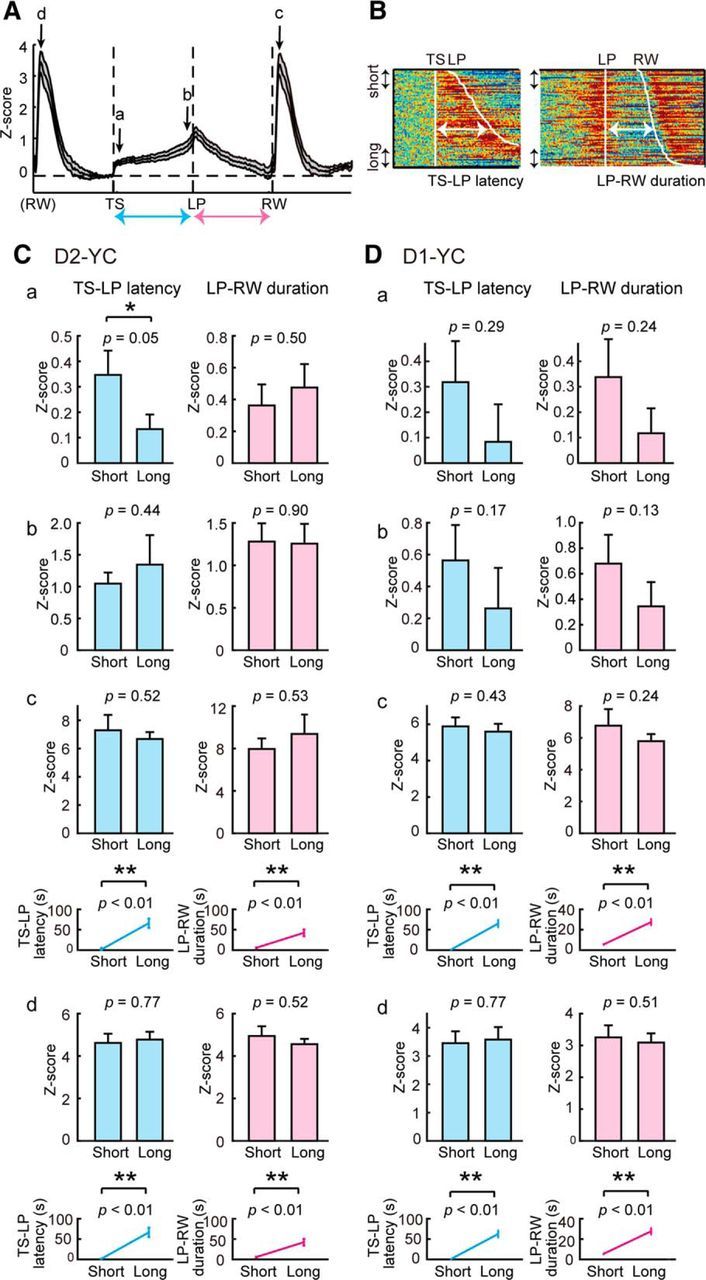

Figure 4.

Relationship between Ca2+ signals of D2-MSNs or D1-MSNs in the VLS and goal-directed behavior of mice. A, Illustration of normalized Ca2+ signal trace (same as Fig. 3G) with four time-points (a–d) and two behavioral parameters (blue and red arrows). B, Definition of short and long latency/duration in color-coded Ca2+ signals from one session consisting of 85 trials (same as Fig. 3D, E). Trials with the shortest and longest 10% were extracted and analyzed as “short” and “long” groups, respectively. C, Comparison of Ca2+ levels with two behavioral parameters in D2-YC mice. Ca, Averaged Ca2+ levels (0.1 s) after TS were compared between short and long groups (left). Short TS-LP latency group displayed higher Ca2+ elevations compared with the long group. LP-RW duration did not influence Ca2+ elevation after TS (right). Cb, Averaged Ca2+ levels (0.1 s) before LP were compared between short and long groups. Neither TS-LP latency nor LP-RW duration affected Ca2+ elevation around the first LP. Cc, Peak Ca2+ levels after RW were compared between both groups. None of parameters influenced peak Ca2+ levels after RW. Cd, Peak Ca2+ levels after previous RW were compared between both groups. None of parameters influenced levels of previous Ca2+ surges. Line graphs represent averaged latency/duration in short and long groups. Top, a–c. Bottom, d. D, Same analyses in D1-YC mice. *p < 0.05 (paired t test). **p < 0.01 (paired t test). n = 12 sessions from 4 D2-YC mice; n = 15 sessions from 5 D1-YC mice. Error bars indicate + SE.

To address the above, we first defined and extracted trials with relatively motivated or unmotivated conditions by sorting TS-LP latency. We selected the top 10% of trials with short TS-LP as motivated conditions and the bottom 10% of trials with long TS-LP as unmotivated conditions from each session (Fig. 4B), and collected trials from all sessions in terms of short and long groups. We analyzed the degrees of Ca2+ elevation at different time points (a-d inFig. 4A) and compared Ca2+ levels among groups. We also ranked trials with LP-RW duration, extracted short and long groups, and compared Ca2+ levels. We did these groupings with both D2- and D1-MSN data.

We found that the short TS-LP group exhibited higher D2-MSN Ca2+ levels just after TS compared with the long TS-LP group (Fig. 4Ca; n = 12 sessions, t(11) = 3.68, p = 0.05, paired t test), suggesting that the degree of Ca2+ elevation after the TS cue correlated to the level of motivation. From other comparisons (short vs long latency/duration at different time points), we did not find any significant differences. Among these, the following negative data should be noted: (1) Time lengths of TS-LP latency and LP-RW duration did not correlate to Ca2+ levels at the first LP (time b). (2) Time lengths of TS-LP latency and lever pressing did not correlate to Ca2+ levels following reward collection (time c). (3) Ca2+ levels at reward collection (time d) did not correlate to either time length related to future events.

Short TS-LP and short LP-RW groups exhibited higher D1-MSN Ca2+ levels just after TS compared with long groups, but there was no significant difference (Fig. 4Da; n = 15 sessions, t(14) = 1.10, p = 0.10, paired t test). Time lengths of TS-LP latency and LP-RW duration did not correlate to D1-MSN Ca2+ levels at the first LP (time b), at the time following reward collection (time c), or at the time of previous reward collection (time d).

Temporally specific optogenetic inhibition of D2- and D1-MSNs in the VLS induces similar effects to goal-directed behavior

To examine the causal relationship between the event-related activities of D2- or D1-MSNs and the goal-directed behavior of mice, we used an optogenetic inhibition of VLS D2- or D1-MSNs and evaluated the effect on motivated behaviors. In this experiment, we used the PR schedule task (Richardson and Roberts, 1996) to address effort-related motivation. We used transgenic mice in which D2-MSNs or D1-MSNs expressed a light-driven proton pump (archaerhodopsin [ArchT]; Fig. 1), referred to as D2-ArchT and D1-ArchT, respectively, and we targeted these cells in the bilateral VLS (Fig. 5A). After PR training, surgery, and retraining, we conducted the PR task combined with event targeted illumination.

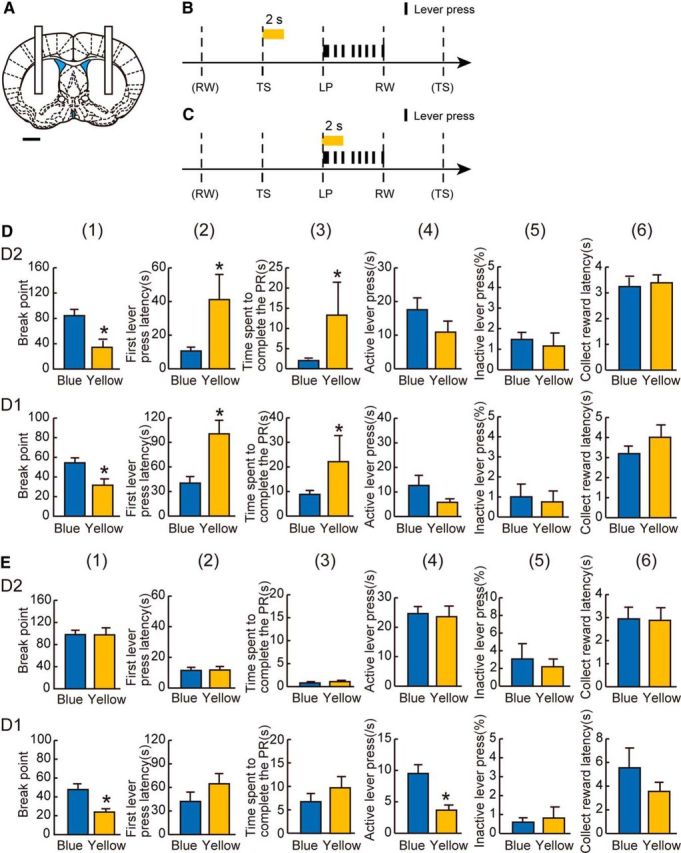

Figure 5.

Effect of optogenetic inhibition of D2-MSNs or D1-MSNs in the VLS on goal-directed behavior in mice. A, Illumination site in the bilateral VLS. Scale bar, 1 mm. B, C, The timing of illumination in the PR task. B, Yellow or blue light was applied at the time of every TS with the lever presentation for 2 s (yellow bar). C, Yellow or blue light was applied at the time of LP behavior for 2 s (yellow bar). D, The effect of yellow-light illumination at the time of TS (B) in D2-ArchT (top row) and D1-ArchT (bottom row) mice, respectively. Yellow-light illumination decreased breakpoint (1), prolonged first LP latency (2), and time spent to complete the PR (3) in both D2 and D1-ArchT mice, whereas it did not affect the active LPs (4), percentage inactive LPs (5), or collect reward latency (6). E, The effect of yellow-light illumination at the timing of LP (C) in D2-ArchT (top row) and D1-ArchT (bottom row) mice, respectively. Yellow-light illumination had no effect in D2-ArchT mice, whereas it decreased breakpoint (1) and active LPs (4) in D1-ArchT mice. Other behavioral parameters were not affected by yellow-light illumination in D1-ArchT mice. *p < 0.05, compared with the blue light control (paired t test). n = 12 sessions from 6 D2-ArchT mice; n = 8 sessions from 3 D1-ArchT mice. Error bars indicate + SE.

We first selected the TS. D2- and D1-ArchT mice were illuminated with yellow (sensitive to ArchT) or blue (insensitive) light for 2 s at the time of TS in every trial of the PR schedule (Fig. 5B) (Tsutsui-Kimura et al., 2017). With yellow light illumination at the TS, both D2- and D1-ArchT mice showed quantitative reductions in goal-directed behavior in terms of breakpoint (1) (n = 12 sessions, t(11) = 3.61, p < 0.05 for D2-ArchT; n = 8 sessions, t(7) = 3.83, p < 0.05 for D1-ArchT, paired t test), first LP latency (2) (t(11) = 2.90, p < 0.05 for D2-ArchT; t(7) = 3.86, p < 0.05 for D1-ArchT), and time spent to complete the PR (3) (t(11) = 2.72, p < 0.05 for D2-ArchT; t(7) = 2.70, p < 0.05 for D1-ArchT), but no significant differences in active LP rate (4) (t(11) = 1.90, p = 0.08 for D2-ArchT; t(7) = 1.97, p = 0.09 for D1-ArchT), percentage inactive LPs (5) (t(11) = 0.57, p = 0.58 for D2-ArchT; t(7) = 1.24, p = 0.24 for D1-ArchT), or collect reward latency (6) (t(11) = 0.89, p = 0.40 for D2-ArchT; t(7) = 1.84, p = 0.10 for D1-ArchT) compared with the blue light session (Fig. 5D). These data indicate that VLS D2- and D1-MSN inhibition immediately after the TS cue resulted in decreased motivation without affecting cognition and appetite, and more importantly, both TS-related VLS D2- and D1-MSN activation encodes motivated behavior.

We next tested the effect of inhibition at the LP time (Fig. 5C). In D2-ArchT mice, 2 s of VLS D2-MSN inhibition after the first LP did not change any index of goal-directed behavior (1–6: breakpoint: n = 12 sessions, t(11) = 0.31, p = 0.76, first LP latency: t(11) = 0.71, p = 0.49, time spent to complete the PR: t(11) = 1.68, p = 0.12, active LP rate: t(11) = 0.32, p = 0.76, percentage inactive LPs: t(11) = 0.03, p = 0.97, collect reward latency: t(11) = 0.01, p = 0.99). Whereas in D1-ArchT mice, VLS D1-MSN inhibition at the same time point reduced goal-directed behavior in terms of breakpoint (1) (n = 8 sessions, t(7) = 3.56, p < 0.05) and active LP rate (4) (t(7) = 4.26, p < 0.05), but not in first LP latency (2) (t(7) = 1.96, p = 0.09), time spent to complete the PR (3) (t(7) = 1.93, p = 0.10), percentage inactive LPs (5) (t(7) = 0.42, p = 0.69), and collect reward latency (6) (t(7) = 1.91, p = 0.10) did not significantly change (Fig. 5E). These data indicate that LP-related VLS D1-MSN activation encodes motivated behavior but VLS D2-MSN activation does not. In addition, the data indicate that the functional readout was distinct between VLS D1 versus D2-MSN activation at the LP time point, but the readout was not exactly opposite.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates concurrent Ca2+ activity within D1- and D2-MSNs in the VLS during a food-incentive, goal-directed behavior. Based on this observation, we conducted a timing- and cell-type-specific optical inhibition of each type of MSN. We showed that the inhibition of both types of MSN at the TS diminished motivated behavior. These results indicate that both D1- and D2-MSN subpopulations in the VLS positively encode food-incentive behavior and do not support the opposing functional roles of D1 versus D2-MSNs. One caveat is that previous other motivation related studies were conducted in the NAc (i.e., the ventromedial striatum); therefore, it is possible that our findings are simply due to the positional difference.

When we discuss “opposing roles” in general, we have to consider the activity of each population on one hand, and the readout after a population-specific manipulation on the other hand. In cases of psychostimulant-related behaviors, the application of a psychostimulant (cocaine) results in increased protein kinase A (PKA) activity in VS D1-MSNs and decreased PKA activity in VS D2-MSNs (Goto et al., 2015), demonstrating a clear opposite reaction. A recent study using Ca2+ fiberphotometry also demonstrated an opposite reaction during the application of cocaine (Calipari et al., 2016). Enforced activation of D1-MSNs increases drug-incentive behavior, whereas activation of D2-MSNs decreases it (Hikida et al., 2010; Lobo et al., 2010; Lobo and Nestler, 2011) and vice versa (Augur et al., 2016), supporting the notion of an antagonistic readout. Accordingly, the scenario of drug-incentive behavior supports opposing roles of VS D1- versus D2-MSNs.

Our study on food-incentive, goal-directed behavior does not support opposing roles of VS D1- versus D2-MSNs in either activity or readout. In terms of activity, we measured compound intracellular Ca2+ signals from each population, whose signals corresponded to neuronal activities (Cui et al., 2013), and found concurrent changes of compound intracellular Ca2+ signals in both populations during behavior. It is known that extracellular dopamine in the VS increases at the time of operant cue exposure and response in food-incentive operant behaviors (Roitman et al., 2004). These results with our findings imply that dopamine input to either population is not enough to induce a detectable, opposing change of compound intracellular Ca2+ signal levels. In this case, we have to note that the increase of extracellular dopamine is the response or the outcome to the natural reward, and the degree of dopamine increase would be more physiological than that in drug-related behaviors including psychostimulant exposure and drug seeking in previously exposed situation. Thus, it is possible that the pathological massive dopamine release seen in drug-related behavior would induce opposing Ca2+ signals in either population.

What triggered changes in compound intracellular Ca2+ signal levels? We assume that excitatory/inhibitory inputs to MSNs dominantly control Ca2+ levels. Glutamatergic neurons from the cortex and thalamus innervate both D1- and D2-MSNs in the striatum. In particular, VLS MSNs receive glutamatergic afferents from the insular cortex (Berendse et al., 1992). The insular cortex activates at the time of cue presentation and the blockade of this activation causes decreased food-incentive behavior (Kusumoto-Yoshida et al., 2015). This report may mean that concurrent D1- and D2-MSN activation is mediated by insular cortex activation during behavior. We also have to consider other excitatory inputs (e.g., projections from the thalamus) as well as inhibitory inputs (e.g., projections from striatal interneurons) as candidate factors that determine compound intracellular Ca2+ signal levels. However, there has not been evidence that excitatory/inhibitory inputs to MSNs are biased to D1- or D2-MSNs. Indeed, concurrent activities of D1- and D2-MSNs during operant tasks are accepted even in the DS (Cui et al., 2013; Isomura et al., 2013; Tecuapetla et al., 2014, 2016). Together, theories of opposition regarding dopamine signals (e.g., PKA) are evident, but opposing neuronal activity (e.g., electrical membrane properties) no longer appears appropriate in terms of describing D1- and D2-MSN function.

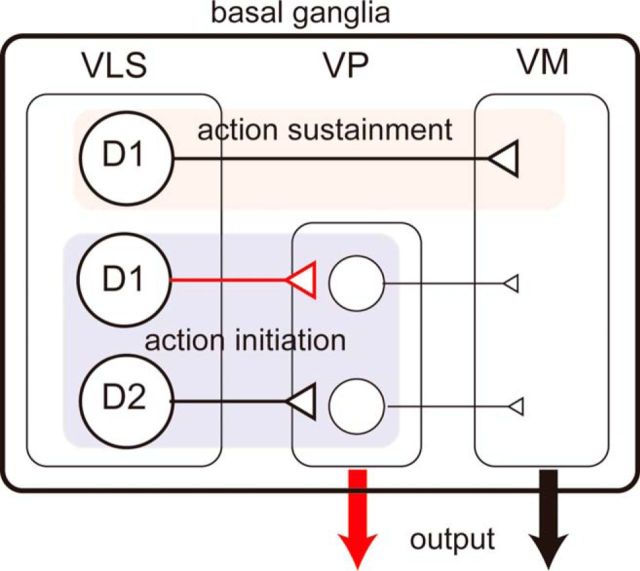

Regarding opposing readouts, our data do not correspond to studies using psychostimulant exposure (Creed et al., 2016). Optogenetic inhibition revealed that the activities of both VLS D1- and D2-MSNs at the TS cue positively encoded the food-incentive motivation, whereas at the first LP, that of only D1-MSNs positively encoded the motivation (Fig. 5). We would like to address the behavioral readout according to anatomical characteristics of the VS. Recently, Kupchik et al. (2015) showed that 50% of VP neurons receive input from NAc D1-MSNs, whereas 89% of VP neurons receive input from D2-MSNs and that 100% of VM neurons receive input from D1-MSNs and 0% of VM neurons receive input from D2-MSNs. The VP projects to the VM; therefore, VP-projecting D1-MSNs can be regarded as an indirect pathway. The VP also sends axons outside the basal ganglia as an output nucleus. In this case, D2-MSNs can be a direct pathway. The sharing of pathways between VS D1- and D2-MSNs may attribute a common readout after a manipulation. According to these anatomical findings and our optogenetic silencing data, we hypothesize that the neural projections from the VS to the VP, which is composed of both D1- and D2-MSNs, including potential collaterals of D1-MSNs (Cazorla et al., 2014), can be responsible for promoting motivation at the TS time, whereas the direct projection from the VS to the VM, which is composed of only D1-MSNs, may be responsible for promoting motivation at the time of LP (Fig. 6). This hypothesis can explain the roles of MSNs in timing- and pathway-specific manners in food-incentive, goal-directed behavior. One caveat is that our targeted region, the middle portion of the VLS, is not identical to the NAc where Kupchik et al. (2015) studied. The VLS receives the input from the insular cortex and projects to the VP (Tsutsui-Kimura et al., 2017); however, the proportion of D1-MSN to VP projection is unknown. Another effort is needed to generalize the Kupchik et al. (2015) findings in the entire VS.

Figure 6.

Proposed encoding of VLS MSNs. Schematic illustration of basal ganglia circuitry (Kupchik et al., 2015) and proposed VLS MSN encoding. Red represents unique connections (VLS D1-MSNs to VP, output from the VP). VLS D1-MSN to VM pathway encodes action sustainment (red shading), whereas VLS D1- and D2-MSN to VP pathway encodes action initiation (blue-shading).

In trying to propose a conceptual scheme for the interpretation of the roles of VLS MSNs in motivated behavior, it is important to consider the distinction among the activational aspects of motivation (Salamone, 1988). Motivation can be defined as the activation of goal-directed behavior. It involves a directional component that enables subjects to select a behavior leading to an optimal outcome and an activational component that initiates and maintains the actions directed to goals (Salamone, 1988; Bailey et al., 2015). In our study, we used FR and PR schedules of lever pressing tasks as a motivational assessment. Both tasks required mice to initiate goal-directed action at various times from the TS to the first LP, and to continue lever pressing until achieving the required ratio. Thus, the period from the TS to the first LP was related to action initiation, and the period from the first LP to RW was related to the sustainment of goal-directed action. Interestingly, during the above periods, concurrent Ca2+ activities were observed in VLS D1- and D2-MSNs (Fig. 3). Unlike these common activity patterns, our optogenetic silencing revealed timing- and population-specific contributions to the activational component of motivation: both D2- and D1-MSNs encode initiation, but only D1-MSNs encode sustainment of goal-directed action (Fig. 5). In turn, supposing our above hypothesis is correct, the initiation of action is encoded by the VLS-VP mixed pathway and the sustainment of action is encoded by the VLS-VM direct pathway. This study is the first to clearly dissociate the contribution of the VLS subpopulations to activational components of motivation, although a previous study observed dissociable patterns of neural firing in the DS regarding action initiation and maintenance (Jin et al., 2014).

In conclusion, our data indicate that D1- and D2-MSNs in the VLS exhibit event-related concurrent Ca2+ activities during food-incentive, goal-directed behavior in mice. Both types of MSNs in the VLS positively encode the action initiation motivational component, whereas only D1-MSNs positively encode the sustainment of motivation. These results allow us to reconsider the conventional thinking of opposing functions of MSNs in the striatum, and propose the possibility of new pathway-specific coding for action initiation and sustainment of motivational processes.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant for Research Fellow 15J06790 to A.N. and 2640100 to I.T.-K., Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 15H03123 Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Area “Oscillology” (16H01621), and Takeda Science Foundation to K.F.T. A.K.E. is a Senior Research Associate of the FRS-FNRS (Belgium) and an investigator of WELBIO. We thank H. Sano for the gift of Pde10a2-tTA transgenic mice.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB (1989) The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci 12:366–375. 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90074-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augur IF, Wyckoff AR, Aston-Jones G, Kalivas PW, Peters J (2016) Chemogenetic activation of an extinction neural circuit reduces cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. J Neurosci 36:10174–10180. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0773-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey MR, Jensen G, Taylor K, Mezias C, Williamson C, Silver R, Simpson EH, Balsam PD (2015) A novel strategy for dissecting goal-directed action and arousal components of motivated behavior with a progressive hold-down task. Behav Neurosci 129:269–280. 10.1037/bne0000060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berendse HW, Galis-de Graaf Y, Groenewegen HJ (1992) Topographical organization and relationship with ventral striatal compartments of prefrontal corticostriatal projections in the rat. J Comp Neurol 316:314–347. 10.1002/cne.903160305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calipari ES, Bagot RC, Purushothaman I, Davidson TJ, Yorgason JT, Peña CJ, Walker DM, Pirpinias ST, Guise KG, Ramakrishnan C, Deisseroth K, Nestler EJ (2016) In vivo imaging identifies temporal signature of D1 and D2 medium spiny neurons in cocaine reward. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:2726–2731. 10.1073/pnas.1521238113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla M, de Carvalho FD, Chohan MO, Shegda M, Chuhma N, Rayport S, Ahmari SE, Moore H, Kellendonk C (2014) Dopamine D2 receptors regulate the anatomical and functional balance of basal ganglia circuitry. Neuron 81:153–164. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creed M, Ntamati NR, Chandra R, Lobo MK, Lüscher C (2016) Convergence of reinforcing and anhedonic cocaine effects in the ventral pallidum. Neuron 92:214–226. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G, Jun SB, Jin X, Pham MD, Vogel SS, Lovinger DM, Costa RM (2013) Concurrent activation of striatal direct and indirect pathways during action initiation. Nature 494:238–242. 10.1038/nature11846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durieux PF, Bearzatto B, Guiducci S, Buch T, Waisman A, Zoli M, Schiffmann SN, de Kerchove d'Exaerde A (2009) D2R striatopallidal neurons inhibit both locomotor and drug reward processes. Nat Neurosci 12:393–395. 10.1038/nn.2286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durieux PF, Schiffmann SN, de Kerchove d'Exaerde A (2012) Differential regulation of motor control and response to dopaminergic drugs by D1R and D2R neurons in distinct dorsal striatum subregions. EMBO J 31:640–653. 10.1038/emboj.2011.400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SM, Eskenazi D, Ishikawa M, Wanat MJ, Phillips PE, Dong Y, Roth BL, Neumaier JF (2011) Transient neuronal inhibition reveals opposing roles of indirect and direct pathways in sensitization. Nat Neurosci 14:22–24. 10.1038/nn.2703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangarossa G, Espallergues J, de Kerchove d'Exaerde A, El Mestikawy S, Gerfen CR, Hervé D, Girault JA Valjent E (2013) Distribution and compartmental organization of GABAergic medium-sized spiny neurons in the mouse nucleus accumbens. Front Neural Circuits 7:22. 10.3389/fncir.2013.00022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto A, Nakahara I, Yamaguchi T, Kamioka Y, Sumiyama K, Matsuda M, Nakanishi S, Funabiki K (2015) Circuit-dependent striatal PKA and ERK signaling underlies rapid behavioral shift in mating reaction of male mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:6718–6723. 10.1073/pnas.1507121112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunaydin LA, Grosenick L, Finkelstein JC, Kauvar IV, Fenno LE, Adhikari A, Lammel S, Mirzabekov JJ, Airan RD, Zalocusky KA, Tye KM, Anikeeva P, Malenka RC, Deisseroth K (2014) Natural neural projection dynamics underlying social behavior. Cell 157:1535–1551. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikida T, Kimura K, Wada N, Funabiki K, Nakanishi S (2010) Distinct roles of synaptic transmission in direct and indirect striatal pathways to reward and aversive behavior. Neuron 66:896–907. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horikawa K, Yamada Y, Matsuda T, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto M, Matsu-ura T, Miyawaki A, Michikawa T, Mikoshiba K, Nagai T (2010) Spontaneous network activity visualized by ultrasensitive Ca(2+) indicators, yellow Cameleon-Nano. Nat Methods 7:729–732. 10.1038/nmeth.1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isomura Y, Takekawa T, Harukuni R, Handa T, Aizawa H, Takada M, Fukai T (2013) Reward-modulated motor information in identified striatum neurons. J Neurosci 33:10209–10220. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0381-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Tecuapetla F, Costa RM (2014) Basal ganglia subcircuits distinctively encode the parsing and concatenation of action sequences. Nat Neurosci 17:423–430. 10.1038/nn.3632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemaru K, Sekiya H, Xu M, Satoh K, Kitajima N, Yoshida K, Okubo Y, Sasaki T, Moritoh S, Hasuwa H, Mimura M, Horikawa K, Matsui K, Nagai T, Iino M, Tanaka KF (2014) In vivo visualization of subtle, transient, and local activity of astrocytes using an ultrasensitive Ca(2+) indicator. Cell Rep 8:311–318. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz AV, Freeze BS, Parker PR, Kay K, Thwin MT, Deisseroth K, Kreitzer AC (2010) Regulation of parkinsonian motor behaviours by optogenetic control of basal ganglia circuitry. Nature 466:622–626. 10.1038/nature09159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravitz AV, Tye LD, Kreitzer AC (2012) Distinct roles for direct and indirect pathway striatal neurons in reinforcement. Nat Neurosci 15:816–818. 10.1038/nn.3100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer AC, Malenka RC (2008) Striatal plasticity and basal ganglia circuit function. Neuron 60:543–554. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupchik YM, Brown RM, Heinsbroek JA, Lobo MK, Schwartz DJ, Kalivas PW (2015) Coding the direct/indirect pathways by D1 and D2 receptors is not valid for accumbens projections. Nat Neurosci 18:1230–1232. 10.1038/nn.4068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumoto-Yoshida I, Liu H, Chen BT, Fontanini A, Bonci A (2015) Central role for the insular cortex in mediating conditioned responses to anticipatory cues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:1190–1195. 10.1073/pnas.1416573112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo MK, Nestler EJ (2011) The striatal balancing act in drug addiction: distinct roles of direct and indirect pathway medium spiny neurons. Front Neuroanat 5:41. 10.3389/fnana.2011.00041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo MK, Covington HE 3rd, Chaudhury D, Friedman AK, Sun H, Damez-Werno D, Dietz DM, Zaman S, Koo JW, Kennedy PJ, Mouzon E, Mogri M, Neve RL, Deisseroth K, Han MH, Nestler EJ (2010) Cell type-specific loss of BDNF signaling mimics optogenetic control of cocaine reward. Science 330:385–390. 10.1126/science.1188472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KB (2004) The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson NR, Roberts DC (1996) Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J Neurosci Methods 66:1–11. 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00153-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roitman MF, Stuber GD, Phillips PE, Wightman RM, Carelli RM (2004) Dopamine operates as a subsecond modulator of food seeking. J Neurosci 24:1265–1271. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3823-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone JD. (1988) Dopaminergic involvement in activational aspects of motivation: effects of haloperidol on schedule-induced activity, feeding, and foraging in rats. Psychobiology 16:196–206. [Google Scholar]

- Sano H, Nagai Y, Miyakawa T, Shigemoto R, Yokoi M (2008) Increased social interaction in mice deficient of the striatal medium spiny neuron-specific phosphodiesterase 10A2. J Neurochem 105:546–556. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05152.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanik MT, Kupchik YM, Brown RM, Kalivas PW (2013) Optogenetic evidence that pallidal projections, not nigral projections, from the nucleus accumbens core are necessary for reinstating cocaine seeking. J Neurosci 33:13654–13662. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1570-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka KF, Matsui K, Sasaki T, Sano H, Sugio S, Fan K, Hen R, Nakai J, Yanagawa Y, Hasuwa H, Okabe M, Deisseroth K, Ikenaka K, Yamanaka A (2012) Expanding the repertoire of optogenetically targeted cells with an enhanced gene expression system. Cell Rep 2:397–406. 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tecuapetla F, Matias S, Dugue GP, Mainen ZF, Costa RM (2014) Balanced activity in basal ganglia projection pathways is critical for contraversive movements. Nat Commun 5:4315. 10.1038/ncomms5315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tecuapetla F, Jin X, Lima SQ, Costa RM (2016) Complementary contributions of striatal projection pathways to action initiation and execution. Cell 166:703–715. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunematsu T, Tabuchi S, Tanaka KF, Boyden ES, Tominaga M, Yamanaka A (2013) Long-lasting silencing of orexin/hypocretin neurons using archaerhodopsin induces slow-wave sleep in mice. Behav Brain Res 255:64–74. 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui-Kimura I, Takiue H, Yoshida K, Xu M, Yano R, Ohta H, Nishida H, Bouchekioua Y, Okano H, Uchigashima M, Watanabe M, Takata N, Drew MR, Sano H, Mimura M, Tanaka KF (2017) Dysfunction of ventrolateral striatal dopamine receptor Type 2-expressing medium spiny neurons impairs instrumental motivation. Nat Commun 8:14304. 10.1038/ncomms14304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]