Abstract

Objective

Many low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) struggle to provide the health services investment required for life-saving congenital heart disease (CHD) surgery. We explored associations between risk-adjusted CHD surgical mortality from 17 LMICs and global development indices to identify patterns that might inform investment strategies.

Design

Retrospective analysis: country-specific standardised mortality ratios were graphed against global development indices reflective of wealth and healthcare investment. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated.

Setting and participants

The International Quality Improvement Collaborative (IQIC) keeps a volunteer registry of outcomes of CHD surgery programmes in low-resource settings. Inclusion in the IQIC is voluntary enrolment by hospital sites. Patients in the registry underwent congenital heart surgery. Sites that actively participated in IQIC in 2013, 2014 or 2015 and passed a 10% data audit were asked for permission to share data for this study. 31 sites in 17 countries are included.

Outcome measures

In-hospital mortality: standardised mortality ratios were calculated. Risk adjustment for in-hospital mortality uses the Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery method, a model including surgical risk category, age group, prematurity, presence of a major non-cardiac structural anomaly and multiple congenital heart procedures during admission.

Results

The IQIC registry includes 24 917 congenital heart surgeries performed in children<18 years of age. The overall in-hospital mortality rate was 5.0%. Country-level congenital heart surgery standardised mortality ratios were negatively correlated with gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (r=−0.34, p=0.18), and health expenditure per capita (r=−0.23, p=0.37) and positively correlated with under-five mortality (r=0.60, p=0.01) and undernourishment (r=0.39, p=0.17). Countries with lower development had wider variation in mortality. GDP per capita is a driver of the association between some other measures and mortality.

Conclusions

Results display a moderate relationship among wealth, healthcare investment and malnutrition, with significant variation, including superior results in many countries with low GDP per capita. These findings provide context and optimism for investment in CHD procedures in low-resource settings.

Keywords: paediatrics, surgery, congenital heart disease, paediatric cardiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study uses data from the International Quality Improvement Collaborative for Congenital Heart Disease (IQIC), which offers a unique opportunity to study outcomes from low-income and middle-income countries where little is known about outcomes for congenital heart surgery.

This is the first study to directly compare development and investment to congenital heart surgery outcomes.

This study adds context to the discussion of national investment in tertiary care in general and for congenital heart surgery in specific emerging economies.

Study sample size is limited by the number of participants in IQIC.

The study does not examine regional variability within countries.

Introduction

In 2015, more than 150 world leaders at the United Nations agreed to adopt the 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) calling for a sustained investment globally to achieve a number of targets aiming at eradicating poverty and inequality, take action on climate change and the environment, improve access to health and education, and build strong institutions and partnerships.1 Of particular importance is SDG3, ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages and its demanding target to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1000 live births and under-five mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1000 live births by 2030. Recent studies show that congenital anomalies, of which heart disease represents nearly half, are the fourth leading cause of neonatal deaths, especially for countries with lower overall childhood mortality,2 which tend to be middle-income, upper middle-income and high-income countries. Congenital heart disease (CHD) can also be a significant contributor to poverty as families can incur catastrophic health costs if care is not covered by health insurance.

Surgery for CHD requires substantial resources, and a highly specialised healthcare infrastructure. Low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) lack both access to care and capacity to perform congenital heart surgeries safely and effectively. Less developed countries have disproportionately higher amount of CHD per million gross domestic product (GDP) compared with more economically developed countries.3 In some cases, even countries that fall in the high-income group, or higher income regions within a country, struggle with allocating appropriate resources to CHD services. For example, Argentina is typically classified as high income, but centres from Argentina chose to be in the International Quality Improvement Collaborative (IQIC) because they felt they struggled with similar problems as LMICs for congenital heart surgery.

Literature has examined general surgical mortality in LMICs, but to date, no studies have examined congenital heart surgery mortality in a comparative context to development. LeBrun et al surveyed hospitals in multiple low-income countries and found limited operative capacity for surgery with most countries having less than one surgeon or anaesthesiologist per 100 000 population.4 Bainbridge et al found that in a mixed surgical population, perioperative mortality declined from the 1970s to 2011, especially in LMICs.5 Hsuing and Abdallah highlight the need for more data on funding of paediatric surgery in LMICs.6

An analysis of congenital heart surgery outcomes within LMICs adds context to the efforts of countries to reduce mortality for CHD. We retrospectively explored associations between risk-adjusted in-hospital survival after congenital heart surgery and indicators of national development and healthcare investment among centres in LMICs participating in an IQIC aimed at reducing congenital heart surgery mortality.

Methods

Congenital heart surgery outcomes

The IQIC for CHD collects surgical outcome data from participating centres in low-resource settings around the world. The IQIC aims to reduce mortality for congenital heart surgery by collaborating with local sites to implement quality improvement strategies such as perioperative communication, infection reduction and team-based practice.7 The IQIC began collecting data in 2008 from five sites and has since grown to 64 sites across 25 countries in 2018. The database is housed at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Outcome data (in-hospital mortality) in the IQIC registry were collected by individual programmes on paediatric congenital heart surgeries performed at each site. Inclusion in the IQIC is voluntary enrolment by hospital sites. Patients included in the registry underwent congenital heart surgery. Sites that actively participated in IQIC in 2013, 2014 or 2015 and successfully passed a 10% data audit were asked for permission to share data for this study. A total of 31 sites in 17 countries (Afghanistan, Argentina, Brazil, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, India, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, Russia, Serbia, Uganda, Ukraine and Vietnam) chose to participate.

Development indicators

The 2014 country-level development indicators are drawn from the publicly available World Bank World Development Indicators database.8 Eight variables are included as indicators of country development and investment in health: GDP per capita, health expenditure per capita, under-five mortality rate, poverty headcount ratio at US$5.50 per day, prevalence of undernourishment, life expectancy at birth, domestic general government health expenditure (% of GDP) and specialist surgical workforce (per 100 000 population).

GDP per capita (in constant 2010 US$) is the sum of gross value added by all resident producers (plus taxes, minus subsidies) divided by midyear population.8 Health expenditure per capita (in current US$) is the sum of public and private health expenditures as a ratio of total population.8 Prevalence of undernourishment is the percentage of the population whose food intake is insufficient to meet dietary energy requirements continuously.8 Poverty headcount ratio is internationally comparable measure of the percentage of the population with income less than US$5.50 a day (2011 international prices).8 The under-five mortality rate (per 1000 live births) is the probability that a newborn baby will die before reaching age five, based on age-specific mortality rates of that year.8 Life expectancy measures years of life for a newborn given current mortality patterns remain throughout their life.8 Domestic general government health expenditure is the amount of public expenses on health as a share of the economy (GDP).8 Specialist surgical workforce is the number of specialist surgical, anaesthetic and obstetric providers (per 100 000 of population).8

Data analysis

We completed a retrospective analysis of IQIC registry data. For each country, we used the IQIC registry to determine the total number of cases of congenital heart surgery in the registry in children less than 18 years of age over the 3-year period 2013–2015. The observed in-hospital mortality rate was calculated as the number of deaths occurring prior to hospital discharge divided by the total number of Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS)-classified surgical cases. The RACHS model is used to evaluate differences in mortality among groups of patients undergoing congenital heart surgery.9 The outcome measure used is a standardised mortality ratio (SMR) for each country, defined as the observed in-hospital mortality rate divided by the mortality rate that would be expected given the country’s patient case mix. The expected in-hospital mortality rate was calculated using the previously validated RACHS risk adjustment method.7 10 The model included surgical risk category (categories 1–6, where 1 represents surgical procedures with the lowest risk for in-hospital mortality and 6 the highest), age group (≤30 days, 31 days to <1 year, 1–17 years), prematurity (<37 weeks), presence of a major non-cardiac structural anomaly and multiple congenital heart procedures during the admission. The RACHS method was developed using US outcomes data, but since the inception of the IQIC in 2008 has been successfully applied to LMICs.7 An SMR greater than 1.0 suggests higher than expected mortality based on patient case mix, while an SMR less than 1.0 represents lower than expected mortality. Two-way scatter plots were used to examine the relationships between SMR and each development indicator; the strength of these relationships was quantified using Spearman correlation coefficients. We also used linear regression analysis to compare unadjusted regression coefficients relating each development indicator to SMR to coefficients adjusted for GDP per capita. We adjusted for GDP per capita because it is a common broad representation of economic status that has been linked to health.11 We did not adjust for any other indicators. The natural log of SMR was used as the outcome for these models since SMR itself was not normally distributed. An ancillary analysis without Peru was also completed after it appeared to be an outlier in figures generated.

Furthermore, we completed a stratified analysis between low complexity cases (RACHS categories 1 and 2) and high complexity cases (RACHS categories 3–6) and SMR. To do this, for each country, we calculated an SMR for RACHS 1–2 and an SMR for RACHS 3–6 and compared correlations between the low RACHS SMR and each development indicator with the high RACHS SMR and each development indicator.

Ethical considerations

Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data capture tools hosted at Boston Children’s Hospital.12 REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for importing data from external sources. The senior author had complete access to the registry data, and the authors are responsible for the study design, analysis and interpretation of data, and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients and public were not involved in the development of this study.

Results

Among 31 programmes in 17 countries, the IQIC database included 24 917 congenital heart surgeries performed in children<18 years of age. The number of programmes per country ranged from one to six. The overall in-hospital mortality rate was 5.0% and country-level mortality rate ranged from 1.7% to 25.0%. The number of congenital heart surgery cases by country and the proportion of cases in each country compared with the total cases is shown in online supplementary figure 1. Centres in China represent the largest percentage of cases, with 33.4% of total cases. The age and RACHS category distribution of cases by country is shown in online supplementary figures 2 and 3. In most countries, the majority of patients undergoing surgery in the centres are 1–17 years old. There is variation in the proportion of RACHS categories, but all countries have at least 50% of cases in low-complexity RACHS category 1 or 2. The full RACHS model used to calculate country SMRs is shown in online supplementary table 1.

bmjopen-2018-028307supp001.docx (1.3MB, docx)

Country SMRs range from 0.40 to 4.85. Unadjusted mortality rates and standardised mortality rates by country are shown in online supplementary figure 4. Correlation coefficients between each development index and SMR and regression coefficients, both unadjusted and adjusted by GDP per capita, by country are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Correlation and regression coefficients for development indicators with standardised mortality ratio

| Indicator | Number of countries | Correlation coefficient | Unadjusted regression coefficient | Regression coefficient adjusted for GDP per capita |

| GDP per capita (US $) | 17 | r=−0.34 | −0.047 | – |

| Health expenditure per capita (US $) | 17 | r=−0.23 | −0.035 | 0.092 |

| Undernourishment (%) | 14* | r=0.39 | 0.40 | 0.78 |

| Under-five mortality rate (per 1000) | 17 | r=0.60† | 0.13† | 0.16 |

| Poverty headcount ratio at US$5.50 a day (% of population) | 11* | r=0.26 | 0.12 | 0.19 |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | 17 | r=−0.35 | −0.50 | −0.49 |

| Domestic general government health expenditure (% of GDP) | 17 | r=−0.22 | −0.094 | −0.030 |

| Specialist surgical workforce (per 100,000) | 11* | r=−0.56 | −0.074 | −0.052 |

*World Bank Index not available for some countries.

†Significant at p<0.05.

P values, gross domestic product (GDP) correlation p=0.18, unadjusted regression coefficient p=0.29, health expenditure correlation p=0.37, unadjusted regression p=0.55, adjusted regression p=0.47, undernourishment correlation p=0.17, unadjusted regression p=0.14, adjusted regression p=0.20, under-five mortality rate correlation p=0.01, unadjusted regression p=0.04, adjusted regression p=0.08, poverty headcount ratio correlation p=0.43, unadjusted regression p=0.46, adjusted regression p=0.33, life expectancy correlation p=0.16, unadjusted regression p=0.11, adjusted regression p=0.24, domestic general government health expenditure correlation p=0.40, unadjusted regression p=0.41, adjusted regression p=0.84. Specialist surgical workforce p=0.07, unadjusted regression p=0.26, adjusted regression p=0.45.

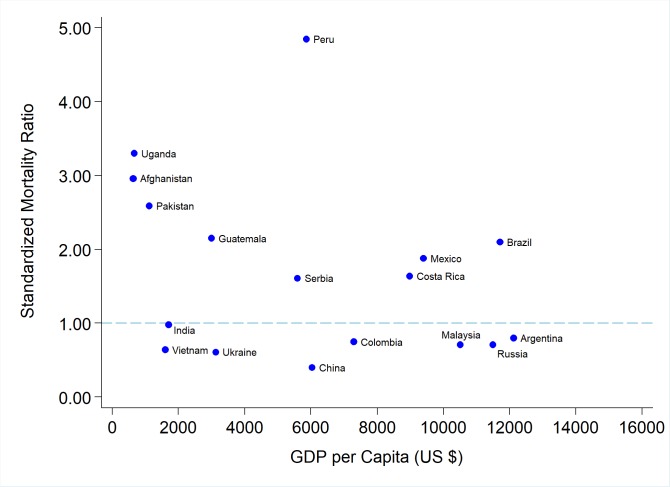

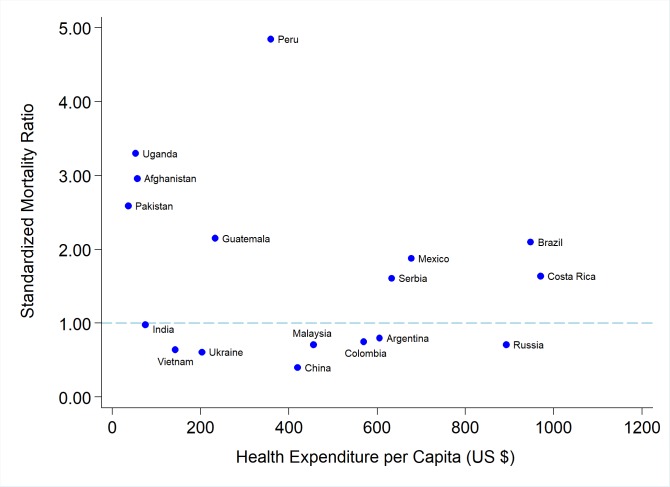

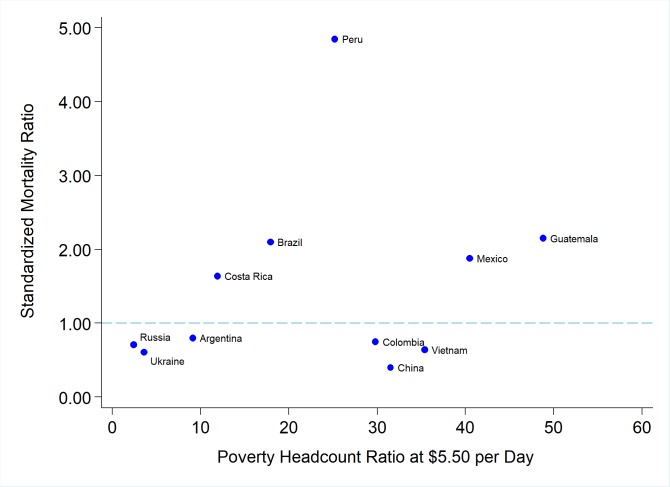

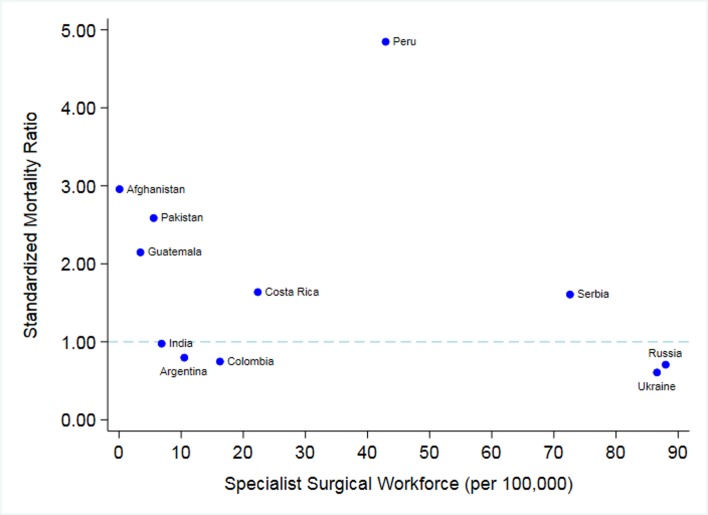

The relationships between SMR by country and GDP per capita, health expenditure per capita, poverty headcount ratio, and specialist surgical workforce are shown in figures 1–4 respectively. Notable in figure 1 is a general trend towards lower SMR with increased GDP per capita, and Peru as a potential outlier in the data. figure 2, health expenditure per capita, is similar to figure 1; however, Serbia and Costa Rica seem to be at higher levels of health expenditure per capita than GDP per capita when compared with the other countries. The relationships between SMR and other development indicators (undernourishment, under-five mortality rate, life expectancy and domestic general government health expenditure) are shown in online supplementary figures 5–8.

Figure 1.

This graph shows negative correlation of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita on the x-axis and standardised mortality ratio on the y-axis by country.

Figure 2.

This graph shows negative correlation of health expenditure per capita on the x-axis and standardised mortality ratio on the y-axis by country.

Figure 3.

This graph shows positive correlation of poverty ratio at US$5.50 a day on the x-axis and standardised mortality ratio on the y-axis by country.

Figure 4.

This graph shows a negative correlation of surgical specialist workforce on the x-axis and standardised mortality ratio on the y-axis by country.

Stratified analysis comparing congenital heart surgery mortality ratios from low-complexity cases (low RACHS categories, 1–2) and high-complexity cases (high RACHS categories, 3–6) is shown in table 2. The low RACHS categories analysis includes a total of 16 870 cases, and the high RACHS categories analysis includes a total of 7997 cases. The low RACHS score SMR correlation largely mirror the overall SMR Spearman correlation, while the high RACHS score SMR has a lower correlation than the low RACHS score SMR with each development indicator except poverty headcount ratio and specialist surgical workforce.

Table 2.

Development indicators and standardised mortality ratio (SMR) correlations stratified by risk adjustment for congenital heart surgery (RACHS) category

| Correlations with SMR | |||

| All cases Correlation coefficient(p value) |

RACHS 1–2 Correlation coefficient(p value) |

RACHS 3–6 Correlation coefficient(p value) |

|

| GDP per capita (US$) | -0.34 (0.18) | -0.38 (0.14) | −0.07 (0.81) |

| GNI per capita (US$) | −0.38 (0.13) | -0.40 (0.11) | -0.16 (0.58) |

| Health expenditure per capita (US$) | −0.23 (0.37) | -0.23 (0.38) | 0.13 (0.66) |

| Undernourishment (%) | 0.39 (0.17) | 0.40 (0.15) | 0.11 (0.74) |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | -0.35 (0.16) | -0.38 (0.14) | -0.07 (0.82) |

| Under-five mortality rate (per 1000) | 0.60 (0.01) | 0.54 (0.02) | 0.43 (0.12) |

| Poverty headcount ratio at US $5.50 a day (%) of population | 0.26 (0.43) | 0.15 (0.65) | 0.38 (0.28) |

| Domestic general government health expenditure (% of GDP) | −0.22 (0.40) | -0.19 (0.47) | -0.01 (0.97) |

| Specialist surgical workforce (per 100 000) | -0.56 (0.07) | -0.50 (0.12) | -0.70 (0.04) |

| Number of countries | 17 | 17 | 14* |

*Three countries (Afghanistan, Peru, and Uganda) were not used in the RACHS 3–6 correlations due to small number of cases.

GDP, gross domestic product; GNI, gross national income.

Discussion

We found the expected positive correlation between under-five mortality and SMR, which was statistically significant. We also found a borderline statistically significant negative correlation between specialist surgical workforce and CHD mortality: as specialist surgical workforce increases, congenital heart surgery mortality decreases, suggesting that adequate workforce is integral to quality congenital heart surgical capacity. Other correlations found that are not statistically significant include negative associations of GDP per capita, health expenditure per capita, domestic government health expenditure and life expectancy with congenital heart surgery SMR: as these indicators increase, SMR decreases. We found positive associations of poverty headcount and undernourishment with SMR: as poverty headcount or undernourishment increases, SMR increases. The association of GDP per capita and SMR suggests that the overall development of a country may be an important component of surgical mortality. While most associations do not reach statistical significance, they display links between development and surgery outcomes.

Although it is difficult to be conclusive, an interesting finding of this study is that there is still substantial variation between countries in SMRs even at similar development levels. For example, Afghanistan and Pakistan have much higher SMRs than India, although they are at similar GDP per capita levels. Nations with high levels of conflict such as Afghanistan may have stressed health systems as a whole,13 14 which would impact congenital heart surgery services. Also, while Afghanistan, Pakistan and India have similar GDP per capita levels, they have very different overall GDP levels, which may affect access to surgery for patients and impact congenital heart surgery SMR variation. Similarly, Peru, Serbia and China are at similar GDP per capita levels yet vary widely in mortality, with China at the lowest SMR. China has a well-organised and efficient health system that likely contributes to better outcomes.15 Although Peru appears to be an outlier, it is not influential—meaning it does not have a substantial impact on the correlation coefficients—with the exception of the association between SMR and undernourishment and SMR and specialist surgical workforce (both associations become stronger without Peru).

When adjusting for GDP per capita, regression coefficients decrease in magnitude for some indicators—poverty, life expectancy and under-five mortality. Therefore, the data indicate that GDP per capita is a driver of the association between these specific indicators and congenital heart surgery mortality. However, the regression coefficient for undernourishment increases when controlling for GDP per capita, suggesting that population-wide undernourishment affects mortality after congenital heart surgery outside the effect of GDP. This may be reflective of the higher likelihood of children undergoing CHD surgery while malnourished in countries where malnourishment is more prevalent, and potentially higher risk of death in such circumstances.16–18 This also suggests that factors that correlate with general paediatric health, such as undernourishment, impact surgical mortality, offering a target for further improvement of health and surgical outcomes.

Comparative analysis of low RACHS SMRs with development indicators and high RACHS SMRs with development indicators displays that low RACHS SMRs correlations are similar to the overall SMR correlations and thus may contribute more to the overall correlation than high RACHS cases. Notably, high RACHS cases SMRs have a stronger correlation with poverty headcount ratio and with specialist surgery workforce than low RACHS cases SMRs, suggesting that low poverty and a present specialist surgery workforce are more important for positive outcomes in high-complexity cases. This potentially suggests that increasing training for a specialist surgery workforce is necessary in LMICs.

As poverty and infectious diseases decrease, non-communicable diseases such as CHD in LMICs account for a greater percentage of childhood deaths. Congenital defects represented 8.7% of global under-five mortality in 2016.19 Many stakeholders believe congenital heart surgery should be considered an ‘essential paediatric surgical procedure’ due to the economic value of these surgeries in a community.20 A substantial fraction (58%) of congenital heart defect burden (avertable disability years) could be alleviated with scaled up congenital heart surgery programmes in LMICs.21 Quality in high-specialty care is of paramount importance. A recent study estimated that cardiovascular diseases are the highest contributor to amenable mortality due to poor-quality care.22 Quality tertiary care requires trained personnel and equipment and infection control.23 Recommended strategies to improve surgical care include training and basic infrastructure and equipment,24 which necessitates investment in healthcare systems.

Our method has several limitations. First, the sample size is only 17 countries and 31 sites (for some indicators, fewer), which limits statistical power, and may be why most associations, except under-five mortality, were not significant. Second, data are analysed at the country level but using only facility-based clinical outcomes data from selected centres that participate in IQIC, which are not representative of countrywide outcomes for CHD surgery and vary in the proportion of country cases that they represent, making firm conclusions difficult, but suggesting that country-specific analyses about patients at different poverty levels may be warranted. IQIC sites are often tertiary-level hospitals with large referral bases and academic intent towards quality improvement; IQIC members are willing and able to collect data and participate in quality improvement activities. That may mean that sometimes hospital settings represented in this study do not always mirror the overall development level of their countries. However, most high-income countries tend to regionalise CHD surgical centres in several large urban areas, to avoid the creation of many small-volume centres.25 Therefore, even though the overall quality of care of the health systems may be low, the centres themselves may have quite good CHD surgical outcomes. Country-level SMRs may also not accurately reflect regional variability in the level of development or resources available for congenital heart surgery, especially in large countries such as China and India. For example, the sites in India are mostly from states in Southern India, which tend to have higher development levels than the Northern part of the country. There may also be variations in case mix of participating institutions due to gaps in the existing diagnosis and referral networks, healthcare financing and social and cultural factors that may result in not treating the patients with the most severe disease, which may not be completely accounted for in risk-adjustment models. Regional differences in healthcare financing for CHD surgery and in-hospital care, including public and private insurance, is a particularly important factor not examined in this study, since care becomes unaffordable to most families if it is not included in universal health insurance coverage package. On the other hand, institutions too could potentially suffer financial losses if reimbursement for CHD surgery is not at the appropriate level.

In conclusion, our results show correlations between various development indicators and congenital heart surgery mortality. Nonetheless, there is variation among countries of similar GDP per capita levels, and lower risk-adjusted mortality in some countries with lower development offers hope and encourages investment in congenital heart surgery programmes. Our study can also be helpful for health policy decision-making. The recent global discourses on access to surgical services as well as on reduction of childhood mortality have been missing a macroanalysis of the investments needed to develop surgical services in LMICs for high-complexity diseases such as CHD. Our findings show that a link could be made between various development indicators and congenital heart surgery mortality, calling for more investigation at a regional level for quality and access improvement strategies and encouraging investment in congenital heart surgery programmes and subspecialty training, especially for all countries committed to achieving the SDG3 target of ending preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age. As governments consider the development of different paediatric services, this study can give them guidance on areas they could invest in. The trend between economic factors and outcomes identified in this study can also be investigated by single centres using socioeconomic data of individual patients to see if a similar link arises, potentially helping to identify higher risk populations.

Further study is required to truly understand why countries with similar development levels vary in congenital heart surgery mortality. Future studies ought to investigate why such variations exist, and examine the role of governments, non-governmental organization (NGOs) or other stakeholders, training and retention of skilled professionals and other personnel, and infection control practices in particular countries. Future studies should attempt to capture outcomes of children who did not have access to operations, as outcomes for these children are also likely associated with development and investment. Studies should also attempt to collect longer term outcomes to represent the broader socioeconomic factors that may affect survival from CHD surgery26 and that could be collected with a more population health-focused database. This inquiry can help establish effective strategies for successful congenital heart surgical programmes in LMICs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work has been published as a conference abstract at the American College of Cardiology and presented at The Global Forum on Humanitarian Medicine in Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery.

Footnotes

Contributors: SR and KJJ had the primary responsibility to design the study and write the manuscript. BZ, KMC, JTC, KD, KG, PH, RKK, JK, WN, NFS and KJJ coordinated the global study data concept and collection. BZ revised multiple manuscript drafts, and DdF interpreted data. KG conducted statistical analyses.

Funding: Funding was received from Kobren Family Chair for Patient Safety and Quality, Harvard University Summer Undergraduate Research in Global Health and Harvard College Research Program.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The institutional review board at Boston Children’s Hospital gave permission for the IQIC data registry to be used for this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data are available by emailing the corresponding author.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. United Nations Sustainable Development. Sustainable development goals - United Nations. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (cited 2018 May 21).

- 2. Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet 2016;388:3027–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31593-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Children’s HeartLink. A Case for the Invisible Child: Childhood Heart Disease and the Global Health Agenda. 2015. https://childrensheartlink.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/The-Invisible-Child-Brief-1.pdf

- 4. LeBrun DG, Chackungal S, Chao TE, et al. Prioritizing essential surgery and safe anesthesia for the Post-2015 Development Agenda: operative capacities of 78 district hospitals in 7 low- and middle-income countries. Surgery 2014;155:365–73. 10.1016/j.surg.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bainbridge D, Martin J, Arango M, et al. Perioperative and anaesthetic-related mortality in developed and developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2012;380:1075–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60990-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hsiung G, Abdullah F. Financing pediatric surgery in low-, and middle-income countries. Semin Pediatr Surg 2016;25:10–14. 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2015.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jenkins KJ, Castañeda AR, Cherian KM, et al. Reducing mortality and infections after congenital heart surgery in the developing world. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1422–30. 10.1542/peds.2014-0356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Bank. World Development Indicators. 2014. http://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/

- 9. Jenkins KJ. Risk adjustment for congenital heart surgery: the RACHS-1 method. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu 2004;7:180–4. 10.1053/j.pcsu.2004.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jenkins KJ, Gauvreau K, Newburger JW, et al. Consensus-based method for risk adjustment for surgery for congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;123:110–8. 10.1067/mtc.2002.119064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Präg P, Mills MC, Wittek R. Subjective socioeconomic status and health in cross-national comparison. Soc Sci Med 2016;149:84–92. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Acerra JR, Iskyan K, Qureshi ZA, et al. Rebuilding the health care system in Afghanistan: an overview of primary care and emergency services. Int J Emerg Med 2009;2:77–82. 10.1007/s12245-009-0106-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Joshi M. Comprehensive peace agreement implementation and reduction in neonatal, infant and under-5 mortality rates in post-armed conflict states, 1989-2012. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2015;15:27 10.1186/s12914-015-0066-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li H, Feng H, Wang J, et al. Relationships among gross domestic product per capita, government health expenditure per capita and infant mortality rate in China. Biomed Res 2017;28. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Argent AC, Balachandran R, Vaidyanathan B, et al. Management of undernutrition and failure to thrive in children with congenital heart disease in low- and middle-income countries. Cardiol Young 2017;27:S22–30. 10.1017/S104795111700258X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oyarzún I, Claveria C, Larios G, et al. Nutritional recovery after cardiac surgery in children with congenital heart disease. Rev Chil Pediatr 2018;89:24–31. 10.4067/S0370-41062018000100024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vaidyanathan B, Radhakrishnan R, Sarala DA, et al. What determines nutritional recovery in malnourished children after correction of congenital heart defects? Pediatrics 2009;124:e294–9. 10.1542/peds.2009-0141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. UNICEF DATA. Under-Five Mortality [Internet]. //data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/under-five-mortality/

- 20. Saxton AT, Poenaru D, Ozgediz D, et al. Economic Analysis of Children’s Surgical Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0165480 10.1371/journal.pone.0165480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Disease control priorities. : Debas HT, Donkor P, Gawande A, Jamison DT, Kruk ME, Mock CN, et al Essential surgery. 421 Third edition Washington, DC: World Bank, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, et al. High-quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1196–e1252. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Children’s HeartLink. Finding the Invisible Child: Childhood Heart Disease and the Global Health Agenda. 2015. https://childrensheartlink.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/The-Invisible-Child-Brief-2.pdf

- 24. Luboga S, Macfarlane SB, von Schreeb J, et al. Increasing access to surgical services in sub-saharan Africa: priorities for national and international agencies recommended by the bellagio essential surgery group. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000200 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Daenen W, et al. Optimal Structure of a Congenital Heart Surgery Department in Europe byEACTS Congenital Heart Disease Committee1. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 2003;24:343–51. 10.1016/S1010-7940(03)00444-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xiang L, Su Z, Liu Y, et al. Effect of family socioeconomic status on the prognosis of complex congenital heart disease in children: an observational cohort study from China. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2018;2:430–9. 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30100-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028307supp001.docx (1.3MB, docx)