Abstract

Objective

Mobile phone-based interventions have been proven to be effective tools for smoking cessation, at least in the short term. Gamification, that is, the use of game-design elements in a non-game context, has been associated with increased engagement and motivation, critical success factors for long-term success of mobile Health solutions. However, to date, no app review has examined the use of gamification in smoking cessation mobile apps. Our review aims to examine and quantify the use of gamification strategies (broad principles) and tactics (on-screen features) among existing mobile apps for smoking cessation in the UK.

Methods

The UK Android and iOS markets were searched in February 2018 to identify smoking cessation apps. 125 Android and 15 iOS apps were tested independently by two reviewers for primary functionalities, adherence to Five A smoking cessation guidelines, and adoption of gamification strategies and tactics. We examined differences between platforms with χ2 tests. Correlation coefficients were calculated to explore the relationship between adherence to guidelines and gamification.

Results

The most common functionality of the 140 mobile apps we reviewed allowed users to track the days since/until the quit date (86.4%). The most popular gamification strategy across both platforms was performance feedback (91.4%). The majority of apps adopted a medium level of gamification strategies (55.0%) and tactics (64.3%). Few adopted high levels of gamification strategies (6.4%) or tactics (5.0%). No statistically significant differences between the two platforms were found regarding level of gamification (p>0.05) and weak correlations were found between adherence to Five A’s and gamification strategies (r=0.38) and tactics (r=0.26).

Conclusion

The findings of this review show that a high level of gamification is adopted by a small minority of smoking cessation apps in the UK. Further exploration of the use of gamification in smoking cessation apps may provide insights into its role in smoking cessation.

Keywords: smoking cessation, gamification, mobile applications, mHealth

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study had a sample of 140 mobile apps for smoking cessation in the UK iOS and Google Play store.

Since the architecture used to operationalise gamification was developed through review of taxonomies from both academic and non-academic sources, the architecture is representative of existing literature.

The exclusion of apps with less than a 4-star rating or fewer than 5 ratings resulted in the omission of a large number of iOS apps, limiting the generalisability of the findings for the iOS store.

Certain app functionalities and gamification elements that are only visible or activated on long-term use may not have been identified by our review.

Introduction

Smoking is responsible for 16% of all deaths in the UK and remains one of the major preventable causes of chronic diseases.1 According to a recent study, smoking is ranked as the number one risk factor driving death and disability within the UK.2 Although behavioural support along with pharmacological treatments is evidently the most effective method for smoking cessation, not all individuals seeking to quit are able or willing to seek face-to-face support.3 The number of individuals using smoking cessation services provided by the National Health Service in the UK is continuously falling,4 a trend observed in multiple European countries.5 The decline in use of stop smoking services is likely to be attributed to access issues in light of significant public health budget cuts.6 On the other hand, due to increased digitalisation and diffusion of technologies, internet and mobile-based interventions are becoming more popular. The use of mobile-delivered support can be initiated independently by smokers, and can complement existing face-to-face support services. With their wide reach and low cost of dissemination, mobile health (mHealth) solutions represent a cost-effective method of helping people quit smoking.7 mHealth interventions have been identified as useful tools for aiding smoking cessation. A Cochrane review found that mobile phone-based cessation interventions had a beneficial impact on 6-month cessation outcomes.8 The systematic review concluded that smokers who received support from mobile phone-based interventions were 1.7 times more likely to quit in the short-term compared with those who did not receive the mobile phone-based intervention.8 Although several mobile apps for smoking cessation exist, many suffer from low engagement and retention levels. According to Singh et al, attaining high levels of user engagement is critical for the success of mHealth which is why it is an important focus of mHealth solutions.9

The application of gamification, the ‘use of game-design elements in a non-game context’,10 in the field of mHealth is rapidly emerging, with mobile app developers increasingly integrating badges and other elements of gamification to motivate and engage users. There is no shortage of gamification advocates, particularly in the context of health behaviour change and mHealth. Some examples of mHealth apps which use gamification and have been empirically studied include Zombies, Run! to increase physical activity, SPARX for battling depression, Mango Health for improving retention of medication use and FitGame to increase intake of fruits and vegetables.11–14 A study on Zombies, Run! found the mobile app increases the motivation of participants to run and uplifts their confidence.11 Likewise, SPARX was found to reduce depression scores and act as a potential alternative to usual treatment in primary care for adolescents suffering from depressive symptoms.12

According to a randomised controlled trial, individuals who had access to a gamified version of a web-based intervention to aid arthritis patients, had a higher level of engagement than those offered the intervention without game elements.15 Similarly, a study found that participants who utilised a gamified smoking cessation intervention had higher levels of motivation and engagement compared with a non-gamified cohort.16 Gamification has also been associated positively with self-efficacy and psychological empowerment, among other behavioural and psychological outcomes.15 17–19

Despite the increased application of gamification in the mHealth industry and the promising findings of its benefits for health behaviour change,20 little research has examined the use of gamification in the context of mHealth and smoking cessation. Although some reviews on gamification use in health apps have been conducted, they have not explicitly focused on apps for smoking cessation or the UK app market.20 21 Of the reviews that have focused on mobile apps for smoking cessation,22–26 none explicitly explored gamification use and only two focused on the UK app market in 2012 and 2014.27 28 Since the mobile app market is constantly evolving, it is important that a more up-to-date review is conducted to gain insight on the currently available mobile apps for smokers seeking to quit. Our study investigated mobile apps for smoking cessation currently available in the UK to gain insight on the types of apps available and their functionalities. Moreover, we examined the types of gamification elements and the level of gamification implemented in the mobile apps. The findings of our research can have important implications for smokers seeking to quit via mHealth, mobile app developers and tobacco policy makers.

Methods

Sample and procedure

The methodology of the mobile app review included three stages: identification, screening and testing. To identify mobile apps available on both Android and iOS platforms in the UK, the software 42matters was used.29 42matters is an online service that provides app market and audience data to provide insight into the mobile app market to build new products. Data on app market Application Programming Interface were extracted using the software on 19 February 2018 using search terms consistent with prior mobile app reviews: ‘stop smoking’, ‘quit smoking’ and ‘smoking cessation’.22–26

Apps were then screened independently by two researchers. Apps with duplicate identification numbers (assigned by the 42matters software to each unique app) were eliminated. Moreover, apps with no rating, a rating of less than four (out of five) or fewer than five individual ratings were eliminated. The cut-off point of five individual ratings is already set forth by the Apple Store. In order to treat apps from both stores equally, we applied the same cut-off point to Android apps. While the methodology used by Android and Apple stores to rank apps is not transparent, it is accepted that the rating, number of ratings, downloads and reviews can be used to determine an app’s popularity. Using popularity as an inclusion or exclusion criterion for mobile app reviews is a common methodology adopted in previous studies as it ensures that the most widely used and most ‘liked’ apps are evaluated.30–32

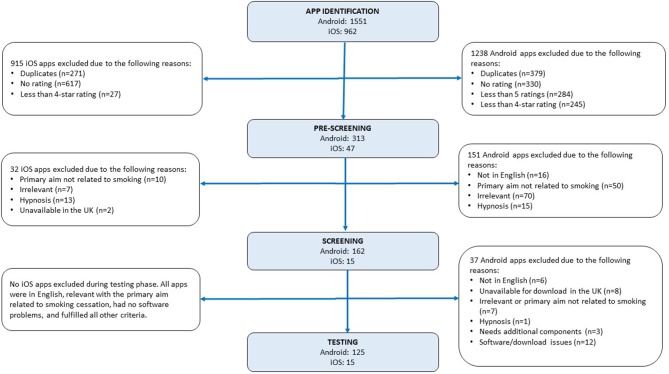

Once preliminary criteria had been applied, the remaining apps were screened based on the description and screenshots of mobile apps provided on their main page in the store. The information was used to apply the following exclusion criteria: primary aim was not to help smokers quit, app was not in the English language, app was irrelevant (ie, app had nothing to do with smoking cessation but was still captured by the software due to the inputted search terms), app focused on hypnosis and app targeted specific patient groups or healthcare professionals. Further exclusions were conducted on installation of mobile apps. Hypnosis apps were excluded because it is not an evidence-based strategy for smoking cessation.33 Additional exclusion criteria on installation included: unsuccessful download of the app, software problems on installation and requirement for additional devices such as smartwatches. After screening was complete, a total of 140 mobile apps remained of which 125 were Android apps and 15 were iOS apps. Three mobile apps were found in both platforms but were still assessed independently by both reviewers as slight variations between Android and iOS versions exist. The procedure inclusive of the number of apps excluded in each stage of the methodology can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Identification, screening and testing stages of the mobile app review.

Coding and classification of mobile apps

After screening procedures, two reviewers independently tested each app. Every app was installed and reviewed for ~30 min on the day of installation. The next day, each mobile app was reviewed for ~5 min for the delivery of any additional notifications. Similar to screening, discrepancies not resolved by the two reviewers, led to a consultation and final decision from a third reviewer.

General functionalities

Functionalities of apps were coded based on categories consistently used by previous mobile app reviews on smoking cessation.23–25 The categories included: (1) tracker: the app tracked the number of days elapsed since the user quit smoking and/or the number of days until the user’s quit date; (2) calculator: the app primarily calculated the amount of money a smoker saved by not smoking and/or the health benefits attained by abstaining; (3) rationing: the app prompted the user to limit the number of cigarettes smoked and/or how often the user can smoke a cigarette (eg, providing time limits); (4) informational: app provided information in the form of text and images to provide the user with knowledge on various aspects of smoking cessation; (5) game: app took the form of a game to help users quit; (6) lung health monitor: app measured and tracks the user’s lung function and health; and (7) other: all functionalities that did not fit one of the six other categories.

Five A guidelines

To understand whether apps were developed with scientific input, we assessed them against the Five A’s framework (Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist, Arrange) for behaviour change.34 This framework is globally accepted as a tool to inform and develop health behaviour change interventions (online supplementary table 1). It has been applied to various behaviours including smoking cessation.

bmjopen-2018-027883supp001.pdf (572KB, pdf)

Gamification

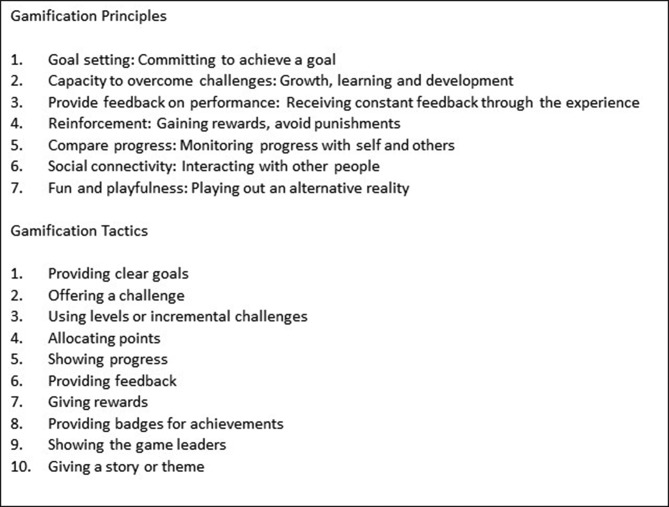

To assess gamification, an architecture developed by Cugelman35 was used.35 It consists of two parts: (1) the persuasive and broad principles of gamification, also known as gamification strategies, and (2) the on-screen features of gamification that users interact with, also known as gamification tactics. Cugelman35 developed this architecture through a review of a number of other taxonomies presented both in academic and non-academic sources.35 A large amount of overlap existed when compared with other frameworks; Cugelman35 captured the active ingredients of gamification as represented in the literature. The architecture used to operationalise gamification can be seen in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Gamification principles and tactics framework.

Data analysis

To examine the price, ratings and features of mobile apps descriptive statistics were calculated. We classified the level of gamification strategies as none, low (1–2 strategies), medium (3–5 strategies) and high (6–7 strategies). Similarly, we classified the level of gamification tactics as none, low (1–3 tactics), medium (4–7 tactics) and high (8–10 tactics). The cut-off points used were arbitrary, as there is no previous research identifying specific thresholds with meaningful implications. In order to investigate any differences between the two mobile platforms, we used Pearson χ2 tests for independence. For instances, when the frequency count was <5, we used Fisher’s exact test of independence. A significance level of p<0.05 was set to determine statistical significance. We also calculated correlation coefficients to explore the association between adherence to Five A guidelines and gamification strategies and tactics. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA V.12.1.

Patient and public involvement

The study had no patient or public involvement.

Results

App functionalities

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of mobile apps for smoking cessation across both platforms. The most common feature among apps across both platforms was the tracker feature which allows users to track the day until and/or since quitting (86.4%). A large majority of apps included a calculator feature which helps users calculate money saved or health benefits accrued since quitting (80.3%). Only 15.7% of apps across both platforms were informational, and only a small number were games or included games to help smokers quit (11.4%). Across both platforms, the majority of apps tested were free (85.0%) and the average user rating across was 4.4 since apps with less than a 4-star rating were excluded.

Table 1.

Overview of mobile apps for smoking cessation

| Platform | ||||

| iOS (n=15) | Android (n=125) | Both platforms (n=140) | ||

| Features of apps | Calculator | 15 (100%) | 99 (79.2%) | 114 (80.3%) |

| Rationing | 1 (6.7%) | 24 (19.2%) | 25 (17.9%) | |

| Tracker | 15 (100%) | 106 (84.8%) | 121 (86.4%) | |

| Informational | 4 (26. 7%) | 18 (14.4%) | 22 (15.7%) | |

| Game | 0 (0%) | 16 (12.8%) | 16 (11.4%) | |

| Lung health monitor | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 1 (6.7%) | 4 (3.2%) | 5 (3.6%) | |

| Cost | Free | 14 (93.3%) | 105 (84.0%) | 119 (85.0%) |

| Paid | 1 (6.7%) | 20 (16.0%) | 21 (15.0%) | |

| Mean price (£) | 1.0 (0.0–0.99) | 2.2 (0.0–8.6) | 2.1 (0.0–8.6) | |

| Popularity | Mean user rating | 4.6 (4.1–5.0) | 4.4 (4.0–5.0) | 4.4 (4.0–5.0) |

| Mean no of ratings | 821 (6–6500) | 1726 (6–35 045) | 1629 (6–35 045) | |

Five A guidelines

We found that 92 out of 140 (65.7%) mobile apps across both platforms only adhered to 1–2 out of the Five A’s. Only 3 out of 140 mobile apps (2.1%) adhered to all Five A guidelines, indicating a low level of scientific and evidence-based development of the mobile apps. Online supplementary table 2 displays detailed results regarding adherence to Five A guidelines.

Gamification

An overview of the number and percentage of each gamification strategy and tactic adopted by mobile apps is presented in table 2. The most popular gamification strategy across both platforms was feedback on performance (91.4%). A majority of the apps allowed users to track their smoking habits or calculate money and health benefits; hence, this gamification strategy was inherently present. Although almost two thirds of mobile apps across both platforms (64.3%) utilised goal setting to motivate users, only 28.6% of apps provided users with the capacity and support to reach the goals set and the challenges faced. For example, ‘smoking log—stop smoking’ is an example of an app which was reviewed that enabled the user to set goals with regard to the number of cigarettes the user can smoke that day or the time until the next cigarette can be smoked, but it provides no support or advice to the user on how this goal can be achieved.36

Table 2.

Number of gamification principles and strategies

| Platform | χ2 | ||||

| iOS (n=15) |

Android (n=125) | Both (n=140) |

P value | ||

| Gamification strategies | Goal setting | 10 (66.7%) | 80 (64.0%) | 90 (64.3%) | 0.839 |

| Capacity of overcome challenges | 7 (46.7%) | 33 (26.4%) | 40 (28.6%) | 0.101 | |

| Feedback on performance | 15 (100.0%) | 113 (90.4%) | 128 (91.4%) | 0.363 | |

| Reinforcement | 10 (66.7%) | 61 (48.8%) | 71 (50.7%) | 0.191 | |

| Compare progress | 4 (26.7%) | 17 (13.6%) | 21 (15.0%) | 0.242 | |

| Social connectivity | 9 (60.0%) | 60 (48.0%) | 69 (49.3%) | 0.380 | |

| Fun and playfulness | 1 (6.7%) | 10 (8.0%) | 11 (7.9 %) | 1.000 | |

| Gamification tactics | Provides clear goals | 10 (66.7%) | 80 (64.0%) | 90 (64.3%) | 0.839 |

| Offers a challenge | 10 (66.7%) | 80 (64.0%) | 90 (64.3%) | 0.839 | |

| Uses levels | 3 (20.0%) | 25 (20.0%) | 28 (20.0%) | 1.000 | |

| Allocates points | 1 (6.7%) | 9 (7.2%) | 10 (7.1%) | 1.000 | |

| Shows progress | 15 (100.0%) | 113 (90.4%) | 128 (91.4%) | 0.363 | |

| Provides feedback | 15 (100.0%) | 113 (90.4%) | 128 (91.4%) | 0.363 | |

| Gives rewards | 10 (66.7%) | 61 (48.8%) | 71 (50.7%) | 0.191 | |

| Provides badges for achievements | 9 (60.0%) | 49 (39.2%) | 58 (41.4%) | 0.122 | |

| Shows game leaders | 1 (6.7%) | 5 (4.0%) | 6 (4.3%) | 0.500 | |

| Gives a story/theme | 1 (6.7%) | 5 (4.0%) | 6 (4.3%) | 0.500 | |

*P<0.05 (No statistically significant values were found).

Additionally, 69 out of 140 mobile apps across both platforms adopted social connectivity (49.3%). However, most of these achieved this by including share options with popular social media platforms. Only a few of the apps provided users with social communities integrated into the app itself to share thoughts or discuss progress with other smokers trying to quit. Finally, the least common gamification strategy observed in the apps was fun and playfulness (7.9%). This finding is consistent with the low presence of on-screen gamification tactics, such as showing game leaders (4.3%) and including a theme or story within the app (4.3%). No statistically significant differences between the two platforms were found for any of the gamification strategies or tactics (p>0.05).

Table 3 presents the level of gamification adopted by mobile apps, in terms of the number of strategies and the number of on-screen features (also known as gamification tactics). Only 7.1% of apps across platforms did not adopt any gamification strategy or tactic. More than half of mobile apps across both platforms had adopted a medium level of gamification strategies (55.0%) and tactics (64.3%). However, only a minority adopted a high level of gamification strategies (6.4%) or a high level of gamification tactics (5.0%). No statistically significant differences between the two platforms were found with relation to the level of gamification strategies or tactics (p>0.05).

Table 3.

Level of gamification incorporated in mobile apps for smoking cessation

| Platform | χ2 | ||||

| iOS (n=15) | Android (n=125) | Both platforms (n=140) | P value | ||

| No of gamification strategies adopted | 0 (None) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (8.0%) | 10 (7.1%) | 0.600 |

| 1–2 (Low) | 4 (26.7%) | 40 (32.0%) | 44 (31.4%) | 0.776 | |

| 3–5 (Medium) | 9 (60%) | 68 (54.4%) | 77 (55.0%) | 0.700 | |

| 6–7 (High) | 2 (13.3%) | 7 (5.6%) | 9 (6.4%) | 0.248 | |

| No of gamification tactics adopted | 0 (None) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (8.0%) | 10 (7.1%) | 0.600 |

| 1–3 (Low) | 4 (26.7%) | 29 (23.2%) | 33 (23.6%) | 0.753 | |

| 4–7 (Medium) | 9 (60.0%) | 81 (64.8%) | 90 (64.3%) | 0.714 | |

| 8–10 (High) | 2 (13.3%) | 5 (4.0%) | 7 (5.0%) | 0.164 | |

*P<0.05 (No statistically significant values were found).

Furthermore, we tested whether adherence to Five A guidelines and the number of gamification strategies and tactics incorporated in smoking cessation mobile apps were related by calculating correlation coefficients (online supplementary table 3). We found that across all mobile apps (n=140) the numbers of gamification tactics and strategies were only weakly correlated with adherence to Five A guidelines, an indicator for level of scientific input (r=0.26 and r=0.38, respectively).

Discussion

We reviewed mobile apps for smoking cessation available in the UK Android and iOS app stores and found that most of them incorporated a limited number of gamification elements and strategies.

We found that a majority of apps tested in our review allowed users to calculate the money saved or health benefits accrued since quitting. The popularity of this feature among mobile apps for smoking cessation is consistent with findings from prior reviews conducted outside of the UK market.23–26 A large proportion of smoking cessation apps available on the UK market also allow users to track the day until and or since quitting. The integration of tracker and calculator features permits users to self-monitor their progress, a technique which has been associated with increased effectiveness for health behaviour change.37–41

Across both platforms the most common gamification strategy adopted was feedback on performance. This finding is consistent with another review which found that 60 out of 64 gamified health apps included feedback and monitoring.21 The least common gamification strategy was fun and playfulness which requires app developers to include on-screen features such as a story or theme for the entertainment and liking of the user. Most apps do not incorporate such elements likely because they are more difficult to implement in comparison to basic tracker and calculator features which inherently provide feedback on performance. Goal setting was present in >60% of apps. This is promising as previous research suggests that goal setting is a fundamental component for successful health behaviour change interventions.42 Although several apps allow users to set goals, not many provide advice or information on how to set realistic and appropriate goals, or how to achieve them.

Nearly half of the apps implement social connectivity as a gamification strategy. However, most do so by providing basic and easily implementable options of sharing results and progress to others via popular social media platforms rather than setting up social communities where thoughts and progress can be discussed with other smokers attempting to quit. Online social communities provide a platform for additional support, as well as a channel to interact with others seeking to quit. Two systematic reviews have found that online social networks and features can be effective and have a positive influence on health behaviour change.43 44 Aside from social support, social connectivity features can drive user engagement via the mechanism of social comparison, which suggests that people compare themselves with others as a method of self-evaluation, which can impact behavioural outcomes.45

Regarding the level of gamification, our results indicate that a majority of apps adopt a medium level of gamification strategies and/or tactics, with few adopting no gamification or a high level of gamification. Several gamification elements, such as providing feedback and displaying progress, are inherently present in mobile apps (eg, Instagram, Google Maps) that would not generally be perceived as gamified. As a consequence of this, existing literature and our analysis may overestimate the level of gamification truly present. Refining gamification taxonomies to better measure the true level of gamification would allow researchers to look beyond elements inherently found in mobile apps.

Despite the possible overestimation of the level of gamification in mobile apps, research shows that gamification can positively impact psychological and behavioural outcomes.12–19 Consequently, gamification can be an important part of persuasive design of mobile apps for smoking cessation which can result in higher user engagement and could thus provide a potentially cost-effective method to improve smoking cessation rates, thereby achieving a substantial public health impact prior research has shown the benefits of mobile and internet-based interventions for individuals of lower socioeconomic status46 47; hence, the provision of effective mobile apps for smoking cessation could reduce health inequalities by increasing cessation rates among disadvantaged groups. However, the development of gamified mobile apps for smoking cessation requires collaboration between gaming experts, software developers, behaviour change specialists and smoking cessation experts. Further research needs to continue to investigate gamified mobile apps for smoking cessation in randomised controlled trials to assess effectiveness on quit rates, as well as the potential benefits.

There are several strengths of our review. The focus on the UK mobile app market, which has not been extensively studied in previous literature, helps gain insight on mobile app interventions available in this geographic region. Moreover, we tested apps available in two major app stores, inclusive of apps with a cost. Previous mobile app reviews focusing on smoking cessation apps available in the UK did not examine apps available on the Android app store nor apps that have to be paid for.27 28 Our findings are up to date and representative of the entire UK mobile app market.

Our findings are also bound by some limitations. Due to the exclusion criteria, apps with less than a 4-star rating or apps with fewer than 5 ratings were excluded. This particularly led to the exclusion of a large number of iOS apps and therefore could have an effect on the generalisability of the findings. Future research could evaluate apps with lower ratings and explore whether gamification levels are correlated with user ratings as such research can have important implications for app developers and health researchers during the design and development of health apps. Additionally, since all mobile apps were reviewed for ~30 min on the day of installation and a few minutes the next day, it could be that certain app functionalities that are only visible or activated on long-term use would not have been recorded. Future studies could explore app functionalities and gamification features for a longer period of time to ensure that apps that have multiday cessation programmes are accurately assessed. Although our review examined adherence to cessation guidelines as an indicator of scientific input, we did not assess the overall quality of mobile apps and hence were not able to correlate level of gamification to app quality. Such analyses would require rigorous assessment of app quality with evidence-based tools, such as the Mobile App Rating Scale.48

Conclusion

Our research comprehensively reviewed the UK market for smoking cessation mobile applications in early 2018. Our findings showed that a medium level of gamification was adopted by just over half of the smoking cessation apps and only a minority adopted a high level of gamification or incorporate more complex and difficult to implement gamification features. Since gamification can be used to address critical limitations of mHealth interventions, such as engagement and retention, our research shows that increased effort and collaboration between gaming experts, software developers and smoking cessation specialists is essential for the development of gamified mobile apps for smoking cessation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NBR conducted the mobile app review and produced the first draft of the paper. DW acted as a second reviewer and helped consolidate the results of the review. FTF and NM provided guidance on the overall methodology of the review and revised the manuscript for content. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results, read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Primary data were collected and analysed by the authors from publicly available sources. No participants were involved nor was an intervention administered. No ethical approval was required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data were extracted from mobile apps available to download on iOS and Google stores. Details of the extracted data are available by the authors upon request.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. National Health Service [Internet]. Statistics on Smoking – England, 2018 [PAS]. 2018. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-smoking/statistics-on-smoking-england-2018/content.

- 2. healthdata.org [Internet]. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation: United Kingdom. 2016. http://www.healthdata.org/united-kingdom.

- 3. Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Fanshawe TR, et al. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;3:CD008286– https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/ 10.1002/14651858.CD008286.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Iacobucci G. Stop smoking services: BMJ analysis shows how councils are stubbing them out. BMJ 2018;362:k3649 10.1136/bmj.k3649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Filippidis FT, Laverty AA, Mons U, et al. Changes in smoking cessation assistance in the European Union between 2012 and 2017: pharmacotherapy versus counselling versus e-cigarettes. Tob Control 2019;28:95–100. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Iacobucci G. Number of people using NHS stop smoking services continues to fall. BMJ 2017;358:j3936 10.1136/bmj.j3936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organisation [Internet]. mHealth: Use of appropriate digital technologies for public health: Seventy First World Health Assembly, A71/20. 26th, 2018. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA71/A71_20-en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Whittaker R, McRobbie H, Bullen C, et al. Mobile phone-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;17:Cd006611 10.1002/14651858.CD006611.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singh K, Drouin K, Newmark LP, et al. Developing a Framework for Evaluating the Patient Engagement, Quality, and Safety of Mobile Health Applications. Issue Brief 2016;5:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deterding S, Dixon D, Khaled R, et al. From game design elements to gamefulness: defining "gamification". Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments; Tampere, Finland. 2181040. ACM 2011:p. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moran MJ, Coons JM. Effects of a Smart-phone Application on Psychological, Physiological, and Performance Variables in College-Aged Individuals While Running. Int J of Exerc Sci 2015;8:104–11. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Merry SN, Stasiak K, Shepherd M, et al. The effectiveness of SPARX; a computerised self-help intervention for adolescents seeking help for depression: randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ Open [Internet] 2012. https://www.bmj.com/content/344/bmj.e2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nguyen E, Bugno L, Kandah C, et al. Is There a Good App for That? Evaluating m-Health Apps for Strategies That Promote Pediatric Medication Adherence. Telemed J E Health 2016;22:929–37. 10.1089/tmj.2015.0211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones BA, Madden GJ, Wengreen HJ. The FIT Game: preliminary evaluation of a gamification approach to increasing fruit and vegetable consumption in school. Prev Med 2014;68:76–9. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Allam A, Kostova Z, Nakamoto K, et al. The effect of social support features and gamification on a Web-based intervention for rheumatoid arthritis patients: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e14 10.2196/jmir.3510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. El-Hilly AA, Iqbal SS, Ahmed M, et al. Game On? Smoking Cessation Through the Gamification of mHealth: A Longitudinal Qualitative Study. JMIR Serious Games 2016;4:e18 10.2196/games.5678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harold DJ. A Qualitative Study on the Effects of Gamification on Student Self‐Efficacy. Philadelphia: International Society for Technology in Education Conference, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Banfield J, Wilkerson B. Increasing Student Intrinsic Motivation And Self-Efficacy Through Gamification Pedagogy. Contemporary Issues in Education Research 2014;7:291–8. 10.19030/cier.v7i4.8843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johnson D, Deterding S, Kuhn KA, et al. Gamification for health and wellbeing: A systematic review of the literature. Internet Interv 2016;6:89–106. 10.1016/j.invent.2016.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lister C, West JH, Cannon B, et al. Just a fad? Gamification in health and fitness apps. JMIR Serious Games 2014;2:e9 10.2196/games.3413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Edwards EA, Lumsden J, Rivas C, et al. Gamification for health promotion: systematic review of behaviour change techniques in smartphone apps. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012447 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choi J, Noh GY, Park DJ. Smoking cessation apps for smartphones: content analysis with the self-determination theory. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e44 10.2196/jmir.3061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abroms LC, Lee Westmaas J, Bontemps-Jones J, et al. A content analysis of popular smartphone apps for smoking cessation. Am J Prev Med 2013;45:732–6. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abroms LC, Padmanabhan N, Thaweethai L, et al. iPhone apps for smoking cessation: a content analysis. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:279–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoeppner BB, Hoeppner SS, Seaboyer L, et al. How Smart are Smartphone Apps for Smoking Cessation? A Content Analysis. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:1025–31. 10.1093/ntr/ntv117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bennett ME, Toffey K, Dickerson F, et al. A Review of Android Apps for Smoking Cessation. J Smok Cessat 2015;10:106–15. 10.1017/jsc.2014.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ubhi HK, Kotz D, Michie S, et al. Comparative analysis of smoking cessation smartphone applications available in 2012 versus 2014. Addict Behav 2016;58:175–81. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ubhi HK, Michie S, Kotz D, et al. Characterising smoking cessation smartphone applications in terms of behaviour change techniques, engagement and ease-of-use features. Transl Behav Med 2016;6:410–7. 10.1007/s13142-015-0352-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. App Market API [Internet]. All the App Intelligence Data you Need. 2019. https://42matters.com/

- 30. Azar KM, Lesser LI, Laing BY, et al. Mobile applications for weight management: theory-based content analysis. Am J Prev Med 2013;45:583–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Breton ER, Fuemmeler BF, Abroms LC. Weight loss—there is an app for that! But does it adhere to evidence-informed practices? Transl Behav Med 2011;1:523–9. 10.1007/s13142-011-0076-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cowan LT, Van Wagenen SA, Brown BA, et al. Apps of steel: are exercise apps providing consumers with realistic expectations?: a content analysis of exercise apps for presence of behavior change theory. Health Educ Behav 2013;40:133–9. 10.1177/1090198112452126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Barnes J, Dong CY, McRobbie H, et al. Hypnotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010;25 10.1002/14651858.CD001008.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Health Organisation. Toolkit for delivering the 5A’s and 5R’s brief tobacco interventions in primary care. Geneva. 2014. http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/smoking_cessation/9789241506946/en/ (accessed 8 Sept 2018).

- 35. Cugelman B. Gamification: what it is and why it matters to digital health behavior change developers. JMIR Serious Games 2013;1:e3 10.2196/games.3139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Charlton C. Smoking Log – Stop Smoking. Google Play Store [Internet]. 2018. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.ccswe.SmokingLog&hl=en (accessed 26 Feb 2018).

- 37. Greaves CJ, Sheppard KE, Abraham C, et al. Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Public Health 2011;11:119 10.1186/1471-2458-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. van Achterberg T, Huisman-de Waal GG, Ketelaar NA, et al. How to promote healthy behaviours in patients? An overview of evidence for behaviour change techniques. Health Promot Int 2011;26:148–62. 10.1093/heapro/daq050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bartlett YK, Sheeran P, Hawley MS. Effective behaviour change techniques in smoking cessation interventions for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. Br J Health Psychol 2014;19:181–203. 10.1111/bjhp.12071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. de Vries H, Eggers SM, Bolman C. The role of action planning and plan enactment for smoking cessation. BMC Public Health 2013;13:393 10.1186/1471-2458-13-393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lorencatto F, West R, Michie S. Specifying evidence-based behavior change techniques to aid smoking cessation in pregnancy. Nicotine Tob Res 2012;14:1019–26. 10.1093/ntr/ntr324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Epton T, Currie S, Armitage CJ. Unique effects of setting goals on behavior change: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 2017;85:1182–98. 10.1037/ccp0000260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Laranjo L, Arguel A, Neves AL, et al. The influence of social networking sites on health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015;22:243–56. 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Maher CA, Lewis LK, Ferrar K, et al. Are health behavior change interventions that use online social networks effective? A systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e40–-e. 10.2196/jmir.2952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Festinger L. A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Human Relations 1954;7:117–40. 10.1177/001872675400700202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, et al. Smoking and socioeconomic status in England: the rise of the never smoker and the disadvantaged smoker. J Public Health 2012;34:390–6. 10.1093/pubmed/fds012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hiscock R, Dobbie F, Bauld L. Smoking Cessation and Socioeconomic Status: An Update of Existing Evidence from a National Evaluation of English Stop Smoking Services. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:1–10. 10.1155/2015/274056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015;3:e27 10.2196/mhealth.3422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027883supp001.pdf (572KB, pdf)