Abstract

Fatty acids affect a number of physiological processes, in addition to forming the building blocks of membranes and body fat stores. In this study, we uncover a role for the monounsaturated fatty acid oleate in the innate immune response of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. From an RNAi screen for regulators of innate immune defense genes, we identified the two stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturases that synthesize oleate in C. elegans. We show that the synthesis of oleate is necessary for the pathogen-mediated induction of immune defense genes. Accordingly, C. elegans deficient in oleate production are hypersusceptible to infection with diverse human pathogens, which can be rescued by the addition of exogenous oleate. However, oleate is not sufficient to drive protective immune activation. Together, these data add to the known health-promoting effects of monounsaturated fatty acids, and suggest an ancient link between nutrient stores, metabolism, and host susceptibility to bacterial infection.

Author summary

The evolution of multicellular organisms has been shaped by their interactions with pathogenic microorganisms. The microscopic nematode C. elegans eats bacteria for food and has evolved inducible immune defenses toward ingested pathogens that are coordinated within intestinal epithelial cells. C. elegans, therefore, presents a genetic system to characterize the requirements for the activation of innate immune defenses. Here, we show that the monounsaturated fatty acid oleate is necessary for the induction of innate immune defenses and for protection against bacterial pathogens, which defines a new link between metabolism and the regulation of anti-pathogen responses in a metazoan host.

Introduction

Fatty acids are the key structural components of phospholipids and triglycerides, and thereby affect nearly every facet of eukaryotic physiology. In addition to forming the building blocks of membranes and functioning as a currency of energy storage, fatty acid molecules promote health in a diverse number of ways. For example, fatty acids act as soluble signals for intracellular communication, affect membrane fluidity, and have been directly linked to lifespan regulation [1–3]. Conversely, excess stores of fatty acids in triglycerides lead to atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes [4]. Thus, it is important to understand how individual fatty acids affect key physiological processes within a cell.

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is a valuable model for studying the roles of fatty acids in metazoan biology [5–10]. Through the sequential action of conserved elongase (elo) and desaturase (fat) genes, nematodes can synthesize the full range of fatty acid molecules found in plants and animals [5–9]. Thus, C. elegans does not have a dietary requirement for specific fatty acids, unlike mammals. In nematodes, as in mammals, the majority of fatty acid molecules are synthesized from stearic acid, a saturated, 18-carbon molecule, which is progressively desaturated and elongated to a variety of monounsaturated (MUFA) and polyunsaturated (PUFA) fatty acids (Fig 1A) [5–9]. The contribution of individual fatty acids to specific biological processes can be characterized using genetic approaches in C. elegans at the level of an entire organism.

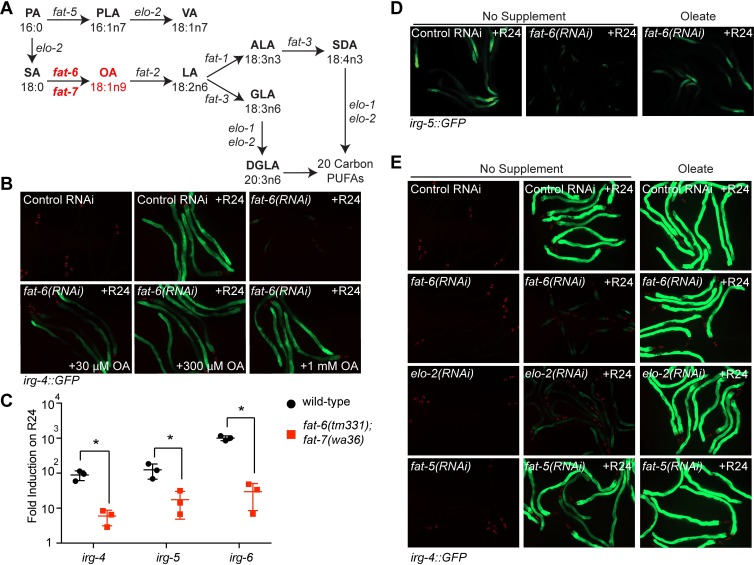

Fig 1. An RNAi screen identifies a role for MUFAs in the activation of C. elegans innate immune effectors.

A. A schematic of the long-chain fatty acid synthesis pathway in C. elegans adapted from [6,17]. Fatty acid nomenclature: X:YnZ, X indicates the number of carbon atoms, Y denotes the number of double bonds, and Z designates the position of the terminal double bond relative to the methyl end of the molecule. Abbreviations: ALA, α-linoleic acid; DGLA, di-homo-γ-linoleic acid; GLA, γ-linoleic acid; LA, linoleic acid; OA, oleate; PA, palmitic acid; PLA, palmitoleic acid; SA, stearic acid; SDA, stearidonic acid; VA, vaccenic acid. B. The C. elegans irg-4::GFP immune reporter was exposed to control or fat-6(RNAi) bacteria seeded on plates containing control or the indicated levels of oleate. The animals were then transferred at the L4 stage to plates containing R24 for approximately 18 hours. Red pharyngeal expression is the myo-2::mCherry co-injection marker, which confirms the presence of the transgene. C. Expression of the immune effectors irg-4, irg-5, and irg-6 were determined using qRT-PCR in wild-type or fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) mutant animals exposed to R24 or solvent control (1% DMSO) for six hours. Data are the average of three independent replicates, each normalized to a control gene and presented as fold induction in R24-exposed vs. solvent control-exposed animals in the indicated genetic background. Error bars show standard deviation. Significance was determined by t-tests, * p<0.05. D. Animals containing the irg-5::GFP immune reporter were grown as described above and exposed to R24. All animals had a Rol phenotype, which confirms the presence of the transgene. E. C. elegans containing the irg-4::GFP immune reporter were fed RNAi bacteria targeting the indicated genes on plates containing control or oleate and exposed to R24, as described above.

Nematodes rely on inducible host defense mechanisms to provide protection from ingested pathogens [11–14]. Because worms normally eat bacteria for food, their evolution has been shaped by interactions with both pathogenic and nonpathogenic microorganisms. The immune effectors in C. elegans include a suite of secreted proteins, including lysozymes, proteins with CUB-like domains, and ShK toxins, some of which are required for host defense during bacterial infection [15–18]. C. elegans with mutations that abrogate the induction of these immune effectors during infection are hypersusceptible to killing by bacterial pathogens [15,19,20]. In this study, we define a requirement for the MUFA oleate in innate immune activation and pathogen defense in C. elegans. Previously, Nandakumar et al. showed that two polyunsaturated fatty acids, γ-linolenic acid (GLA) and stearidonic acid (SDA), are required for the basal expression of innate immune effectors [17]. Here, we show that oleate is necessary for innate immune activation and resistance to bacterial infection in a manner distinct from the effects of GLA and SDA. Because oleate is among the most abundant fatty acids in cells, our data suggest an ancient link between cellular energy stores and immune activation.

Results

An RNAi screen identifies a role for MUFAs in the activation of C. elegans innate immune effectors

We previously conducted an RNAi screen of 1,420 intestinal genes for innate immune regulators in C. elegans [21]. We used an immunostimulatory small molecule called R24 (also called RPW-24) and a GFP-based transcriptional reporter, irg-4::GFP, which provides a convenient readout of innate immune activation [18,21–25]. The gene irg-4 (F08G5.6) is transcriptionally upregulated during infection with multiple pathogens and contains a CUB-like domain, which is present in many of the secreted immune effectors in C. elegans [15,16,18]. irg-4 is required for normal resistance to bacterial infection, but does not modulate the normal lifespan of C. elegans or affect susceptibility to other stressors [16–18]. irg-4 is also strongly upregulated by R24, a xenobiotic that protects nematodes from bacterial infection by boosting innate immune responses [18,21,22,25]. Because of its potent immunostimulatory properties, R24 is a useful tool for dissecting the metabolic requirements of immune activation without altering the bacterial diet of C. elegans [18,21–25]. The RNAi screen identified 29 gene inactivations that are required for the R24-mediated induction of the innate immune reporter irg-4::GFP [21]. Interestingly, two of the genes identified in this screen are the stearoyl-coenzyme A (CoA) desaturases fat-6 and fat-7, which function redundantly to synthesize oleate from stearic acid (Fig 1A) [5]. RNAi-mediated knockdown of fat-6 completely abrogated the induction of irg-4::GFP by R24 (Fig 1B) while knockdown of fat-7 partially suppressed its upregulation (S1A Fig).

To validate the results of the RNAi studies in the irg-4::GFP transcriptional reporter, we used qRT-PCR to examine the transcriptional regulation of the irg-4 gene in wild-type and in fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) double-mutant animals, which are deficient in oleate production [5,8]. The R24-mediated induction of irg-4 was reduced in fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) animals compared to wild-type animals (Fig 1C). In addition, the induction of two other immune effectors, irg-5(F35E12.5) and irg-6(C32H11.1), was also attenuated in the fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) double mutant (Fig 1C). Like irg-4, irg-5 and irg-6 are strongly induced during infection with the bacterial pathogen P. aeruginosa and by the immunostimulatory xenobiotic R24 [18,21–23]. In addition, knockdown of irg-5 and irg-6 makes C. elegans more susceptible to infection by P. aeruginosa [18]. The defect in immune activation by fat-6(RNAi) was also visualized using the irg-5::GFP transcriptional reporter (Fig 1D). Thus, stearoyl-CoA desaturases are required for the induction of at least three key immune effectors in C. elegans.

We performed fatty acid supplementation experiments to determine if the effect of the stearoyl-CoA desaturases on immune activation depends specifically on the production of the MUFA oleate. Interestingly, supplementation of exogenous oleate rescued, in a dose-dependent manner, the R24-mediated immune activation defect of the irg-4::GFP reporter strain in fat-6(RNAi) animals (Fig 1B). Oleate is also required for the upregulation of irg-5::GFP by R24, as supplementation of this MUFA rescued the induction defect conferred by knockdown of fat-6 (Fig 1D).

Consistent with a key role for MUFAs in immune activation, knockdown of the elongase elo-2, which catalyzes the conversion of palmitic acid to stearic acid, the step immediately upstream of oleate synthesis, also suppressed the activation of irg-4::GFP by R24 (Fig 1E). Importantly, oleate supplementation also fully complemented the immune activation defect of elo-2(RNAi) animals (Fig 1E). These data demonstrate that lack of oleate, and not an accumulation of upstream stearic acid, is responsible for deficits in immune effector induction. In addition, knockdown of fat-5, the palmitoyl-CoA desaturase, which also preferentially acts on palmitic acid, but converts it to a different MUFA, palmitoleic acid (PLA), had no effect on the induction of irg-4::GFP (Fig 1E).

Our RNAi screen also identified the mediator subunit mdt-15 among the 29 gene inactivations that are required for the R24-mediated induction of the innate immune reporter irg-4::GFP [21]. We subsequently showed that mdt-15 is required for the induction of innate immune effectors and for defense against the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa [21]. In addition to its role as an immune regulator, MDT-15 controls the transcription of a suite of fatty acid biosynthesis enzymes [26–28]. Interestingly, oleate supplementation did not rescue the induction of irg-4::GFP in mdt-15(tm2182) loss-of-function animals, indicating that mdt-15 controls multiple steps in the activation of innate immune effectors (S1B Fig).

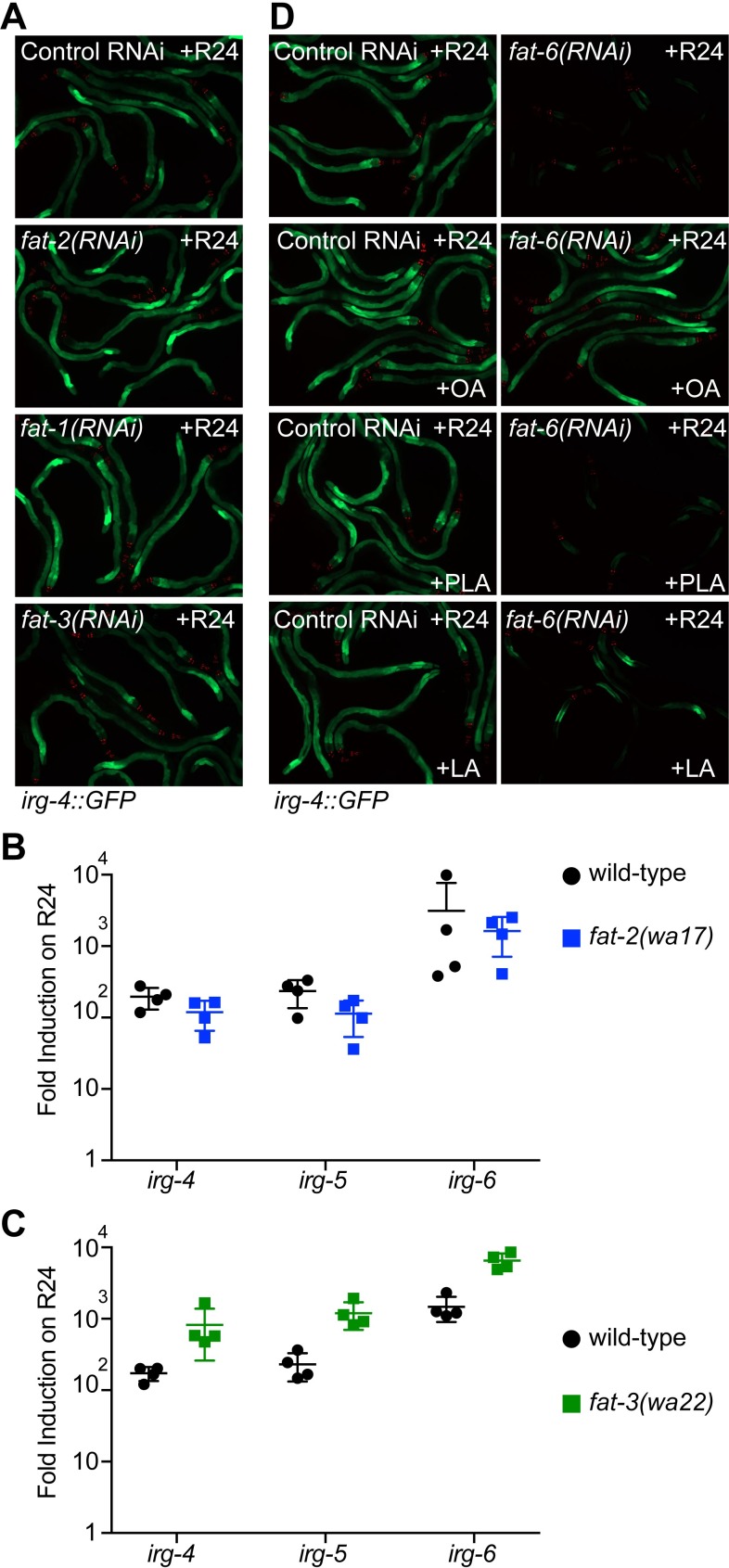

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are not required for immune effector induction by the immunostimulatory xenobiotic R24

Monounsaturated fatty acids are converted to polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) by desaturases that initially use oleate as a substrate [6]. To determine if a PUFA is required for immune effector induction by the immunostimulatory xenobiotic R24, we used both genetic and fatty acid complementation experiments. We examined the induction of irg-4::GFP in animals deficient in the desaturase fat-2, which catalyzes the first step in PUFA synthesis (the conversion of oleate to linoleic acid), and also fat-1(RNAi) and fat-3(RNAi), the enzymes that act downstream of fat-2 in the synthesis of PUFAs (Fig 1A) [6,7]. Knockdown of fat-1, fat-2, or fat-3 had no effect on the induction of irg-4::GFP by R24 (Fig 2A). We confirmed this RNAi experiment using the fat-2(wa17) and the fat-3(wa22) loss-of-function mutants (Fig 2B and 2C). Notably, the R24-mediated induction of the immune effectors irg-4, irg-5, and irg-6 in the fat-2(wa17) and the fat-3(wa22) mutants were not significantly lower than in wild-type animals (Fig 2B and 2C).

Fig 2. Polyunsaturated fatty acids are not required for immune induction by the immunostimulatory small molecule R24.

A. C. elegans irg-4::GFP immune reporter animals were fed the indicated RNAi bacteria and transferred at the L4 stage to plates containing R24 for approximately 18 hours. B and C. Expression of the immune effectors irg-4, irg-5, and irg-6 were determined using qRT-PCR in wild-type, fat-2(wa17), and fat-3(wa22) mutant animals exposed to R24 or the solvent control (DMSO) for six hours. Data are the average of four independent replicates, each normalized to a control gene and presented as fold induction in R24-exposed vs. solvent control-exposed animals in the indicated genetic background. Error bars show standard deviation. Significance was determined by t-tests. There was no significant difference in the R24-mediated induction of the indicated gene in fat-2(wa17) animals or in fat-3(wa22) mutants for irg-4. In fat-3(wa22) animals, the induction of irg-5 and irg-6 by R24 was significantly higher than in wild-type (p <0.001). D. C. elegans irg-4::GFP immune reporter animals were fed control or fat-6(RNAi) bacteria seeded on plates containing control or 500 μM of the indicated fatty acid. PLA is palmitoleic acid and LA is linoleic acid. The animals were then transferred at the L4 stage to plates containing R24 for approximately 18 hours. The presence of the transgene is confirmed by red pharyngeal expression of the myo-2::mCherry co-injection marker.

Supplementation of individual fatty acids to fat-6(RNAi) animals confirmed these genetic observations. Unlike oleate supplementation, addition of the 16 carbon MUFA palmitoleic acid (PLA), which is synthesized by the desaturase fat-5 (Fig 1A), did not complement the irg-4::GFP induction defect in fat-6(RNAi) animals (Fig 2D). In addition, supplementation of the PUFA linoleic acid (LA), which is synthesized by fat-2 using oleate as a substrate (Fig 1A), also failed to fully complement the irg-4::GFP induction defect of fat-6(RNAi) animals (Fig 2D). Together, these data show that the fatty acid oleate, and not another MUFA or PUFA, is required for the induction of the innate immune effector genes by an immunostimulatory small molecule.

Stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity is required for immune effector induction

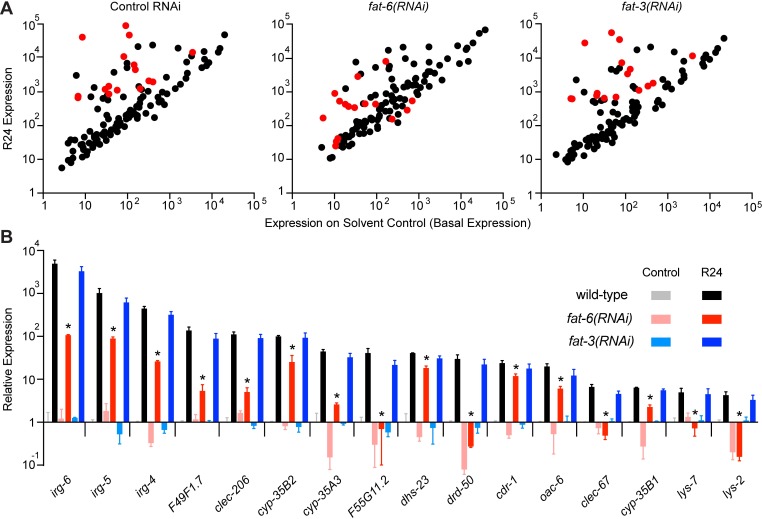

To determine if stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity has a broad effect on the induction of innate immune effectors, we profiled the transcription of 118 immune and stress response genes in wild-type, fat-6(RNAi), and fat-3(RNAi) animals, each exposed to the solvent control (DMSO) or R24 (Fig 3A). Of the 40 genes that were induced at least 4-fold by R24, the upregulation of 16 genes was significantly attenuated in fat-6(RNAi) animals (Fig 3A and 3B and S1 Table). As we observed in our studies of irg-4, irg-5, and irg-6 in the fat-3(wa22) mutant (Fig 2C), the induction of these 16 fat-6-dependent genes was not affected by knockdown of fat-3 (Fig 3A and 3B). For this transcription profiling experiment, we chose to use fat-6(RNAi) to examine the effects of oleate depletion on immune activation. Others have also used single knockdown of either fat-6 or fat-7 to recapitulate the phenotypes observed in the fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) double mutant [3,29]. Of note, the R24-mediated upregulation of irg-4, irg-5, and irg-6 was not attenuated in the fat-6(tm331) or fat-7(wa36) single mutants (S2A and S2B Fig), but the induction of these immune effectors was suppressed in fat-6(RNAi) animals (Fig 3B), as in the fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) double mutants (Fig 1C). We also confirmed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) that knockdown of fat-6 significantly decreases the pool of oleate and causes accumulation of the upstream fatty acid stearate (S1C Fig).

Fig 3. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity is required for the induction of an innate immune response in C. elegans.

A. Dot plots showing the NanoString nCounter gene expression analysis of 118 immune and stress response genes in C. elegans grown on the indicated RNAi bacteria and exposed to control or R24. Each dot represents one gene. Red dots highlight the 16 genes whose R24-mediated induction is significantly suppressed in fat-6(RNAi) animals. Data are the average of two independent replicates. B. The expression of the 16 fat-6-dependent genes in the indicated genotypes and conditions is shown relative to wild-type animals exposed to control. Significance was determined using t-tests, * p<0.05. Data are the average of two independent replicates, each normalized to three control genes and expressed relative to the baseline condition (wild-type animals exposed to control) for each gene. Error bars show standard deviation.

Interestingly, each of the 16 fat-6-dependent, fat-3-independent genes encode putative immune effectors that are induced during infection with at least one bacterial pathogen, a group that includes the innate immune effectors irg-4, irg-5, and irg-6 (Fig 3B). Twenty-four genes, however, were induced by R24 in a manner independent of fat-6 (S1 Table). Thus, fat-6 modulates the transcription of a specific subset of genes, including a group of innate immune effectors. Moreover, the observation that the induction of these 16 genes was not controlled by fat-3 further supports the specificity of fat-6 in the regulation of innate immune responses.

Oleate is required for host resistance to P. aeruginosa infection

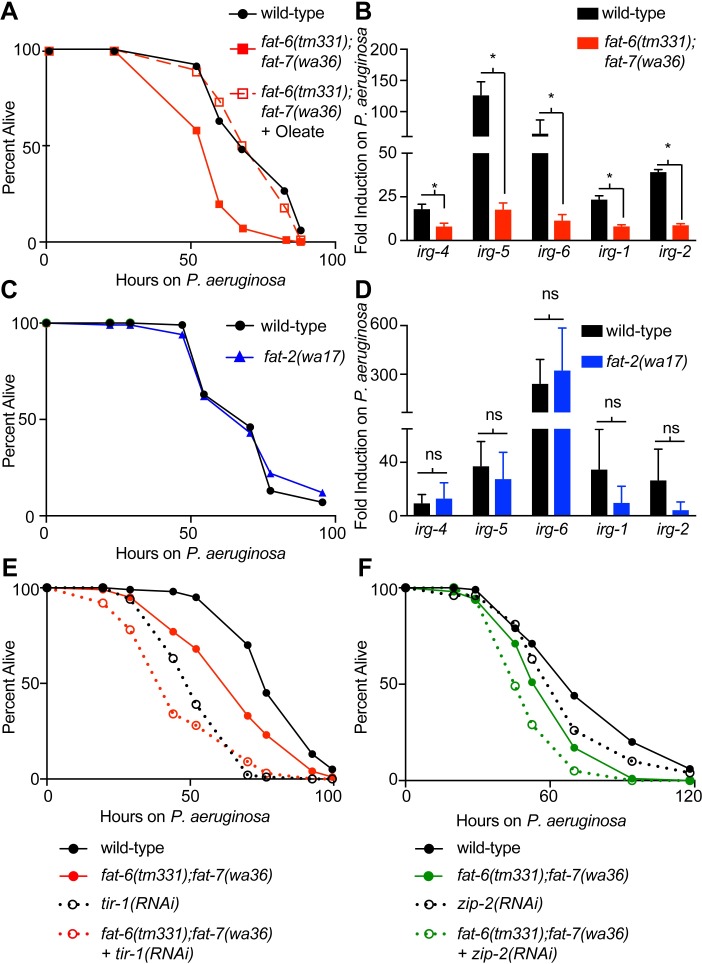

Of the 16 genes whose R24-mediated induction was dependent on fat-6, ten are putative immune effectors that are also induced during infection with P. aeruginosa, including three known modulators of the host susceptibility to pseudomonal infection, irg-4, irg-5, and irg-6 [16–18]. To determine if oleate is important for host defense in C. elegans, we performed pathogenesis assays with P. aeruginosa. The fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) double mutant was more susceptible to infection by P. aeruginosa than wild-type animals, consistent with a prior report [17] (Fig 4A and S2A Table). Importantly, fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) animals have a similar lifespan as wild-type animals when grown under standard laboratory conditions [30]. These data suggest that the hypersusceptibility to pathogen-mediated killing in the fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) double mutant is not secondary to pleiotropic effects of these mutations on worm fitness. Supplementation of oleate to the fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) animals fully complemented the enhanced susceptibility of this mutant to pathogen infection (Fig 4A and S2A Table). Of note, fat-6(tm331) and fat-7(wa36) single mutant worms are not more susceptible to pathogen-mediated killing than wild-type animals, as noted previously [17] (S3 Fig and S2B Table). Consistent with the key role of fat-6 and fat-7 in the regulation of innate immune responses, the fold induction of the innate immune effectors irg-4, irg-5, irg-6, irg-1, and irg-2 during pseudomonal infection was significantly attenuated in the fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) double mutant compared to wild-type (Fig 4B).

Fig 4. Oleate is required for host resistance to P. aeruginosa infection.

A and C. P. aeruginosa pathogenesis assays of wild-type and fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) (A) or fat-2(wa17) (C) animals grown on control media or oleate-supplemented media, as indicated. Animals were transferred at the L4 stage to plates containing P. aeruginosa. Assay plates were not supplemented with oleate. fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) animals are more susceptible to killing by P. aeruginosa (p<0.01). Oleate supplementation rescues the enhanced susceptibility to pathogen phenotype of the fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) mutant (p<0.01). fat-2(wa17) animals are not hypersusceptible to killing (p = not significant). Data are representative of at least two trials. Sample sizes, mean lifespan, and p values for all trials are shown in S2A Table. Significance was determined using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests. B and D. Expression of the indicated genes measured by qRT-PCR in wild-type, fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) double-mutant, or fat-2(wa17) animals exposed to P. aeruginosa at the L4 stage for 6 hours. Data are the average of three independent replicates, each normalized to a control gene and presented as fold induction in animals of the indicated genetic background infected with P. aeruginosa vs. animals fed the standard bacterial food source (E. coli OP50). Error bars show standard deviation. Statistical significance was determined using t-tests. * p<0.05. E and F. P. aeruginosa pathogenesis assays of wild-type and fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) exposed to control RNAi bacteria, tir-1(RNAi) or zip-2(RNAi) bacteria, as indicated. fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36)+ tir-1(RNAi) animals are significantly more susceptible than fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) mutants and tir-1(RNAi) animals (p<0.05). In addition, fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36)+ zip-2(RNAi) animals are significantly more susceptible than fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) mutants and zip-2(RNAi) animals (p<0.05). Data are representative of at least two trials. Sample sizes, mean lifespan, and p values for all trials are shown in S2A Table. Significance was determined using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests.

Nandakumar et al. previously defined a role for two PUFAs, GLA and SDA, in the basal regulation of innate immune effectors and pathogen resistance in C. elegans [17]. We considered whether the effect of oleate on the activation of immune responses could occur through its metabolism to GLA and SDA; however, several lines of evidence show that this is not the case. The pathogen susceptibility and immune effector transcription profile of fat-2(wa17) mutants demonstrate that the effect of oleate on innate immune activation is not dependent on the production of PUFAs. The desaturase fat-2 acts immediately downstream of oleate production to catalyze the first step in PUFA biosynthesis (Fig 1A). fat-2(wa17) mutant animals are not more susceptible to P. aeruginosa infection than wild-type animals (Fig 4C and S2A Table). In addition, the induction of the immune effectors irg-4, irg-5, irg-6, irg-1, and irg-2 during pseudomonal infection was not compromised in fat-2(wa17) mutants compared to wild-type (Fig 4D), unlike what we observed for the fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) double mutant (Fig 4B). We also examined the desaturase fat-3, which acts downstream of fat-2 in the synthesis of PUFAs, including GLA and SDA (Fig 1A). Nandakumar et al. previously showed that fat-3 is required for resistance to P. aeruginosa via the fatty acids GLA and SDA [17]. We found that exogenous oleate did not rescue the enhanced susceptibility of the fat-3(wa22) mutant to pseudomonal infection (S4 Fig and S2D Table). Thus, fat-6 and fat-7 affect pathogen susceptibility specifically through the production of oleate, in a manner that is independent of PUFA synthesis via the enzymes fat-2 or fat-3.

Stearoyl-CoA desaturases are required for the induction of immune effectors, such as irg-4, irg-5, and irg-6, whose basal, or resting, expression is dependent on the p38 MAPK PMK-1 innate immune pathway and those, like irg-1 and irg-2, whose transcription are regulated independent of this canonical immune pathway (Fig 4B) [15,18,21,31]. Interestingly, knockdown of tir-1, the Toll/IL-1 (TIR) domain protein that is an integral component the p38 MAPK PMK-1 signaling cassette [19,32,33], further enhanced the susceptibility of the fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) double loss-of-function mutant strain to pseudomonal infection (Fig 4E and S2A Table). Likewise, knockdown of the bZIP transcription factor zip-2, which controls the induction of irg-1 and irg-2 during P. aeruginosa infection [31], caused the fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) double mutant to be more susceptible to killing by P. aeruginosa (Fig 4F and S2A Table). These data suggest that fat-6 and fat-7 are required for the proper expression of a broad group of innate immune effectors via a mechanism that operates in parallel to the p38 MAPK PMK-1 and ZIP-2 immune pathways.

Stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity is necessary for protection against diverse bacterial pathogens

We performed GC-MS to determine if R24 treatment changes the abundance of cellular oleate. Interestingly, GC-MS revealed that the fraction of both oleate and linoleic acid relative to the total fatty acid pool significantly increased in R24-treated samples compared to controls (Fig 5A). Together, these data show that treatment with the immunostimulatory xenobiotic R24 shifts the fatty acid pool towards more oleate.

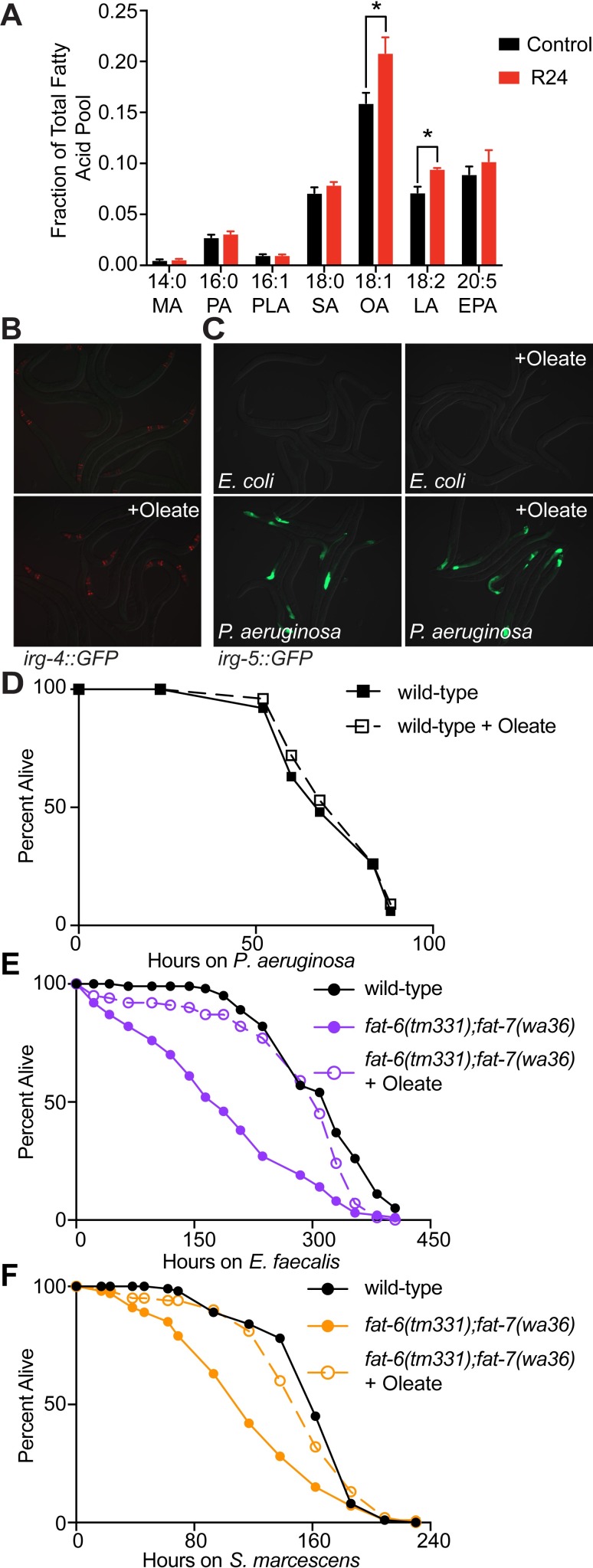

Fig 5. Oleate is necessary but not sufficient for pathogen resistance in C. elegans.

A. GC-MS of L4-stage animals exposed to R24 or solvent control for 24 hours. Data are the average of three independent replicates with error bars showing standard deviation. Statistical analyses performed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. * p<0.05. Abbreviations: MA, myristic acid; PA, palmitic acid; PLA, palmitoleic acid; SA, stearic acid; OA, oleic acid; LA, linoleic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid. B and C. C. elegans irg-4::GFP (B) or irg-5::GFP (C) animals were grown on plates containing control or oleate, as indicated. The animals were then transferred at the L4 stage to plates containing P. aeruginosa or E. coli OP50, as indicated. D, E, F. C. elegans pathogenesis assays with P. aeruginosa (D), E. faecalis (E) and S. marcescens (F) in wild-type and fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) animals grown on control media or oleate-supplemented media, as indicated. Animals were transferred at the L4 stage to plates containing the indicated pathogen. Assay plates were not supplemented with oleate. There is no significant difference between the conditions in D. In E and F, the fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) mutants are more susceptible to killing by the indicated pathogen (p<0.01). Oleate supplementation rescues the enhanced susceptibility to pathogens phenotype of the fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) mutant in both E and F (p<0.01). Data are representative of at least two trials. Sample sizes, mean lifespan, and p values for all trials are shown in S2C Table. Significance was determined using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests.

Because oleate is required for the induction of innate immune effectors and is increased in the presence of R24, we asked if this MUFA is sufficient for innate immune activation in C. elegans. However, the addition of oleate to the standard bacterial food source for C. elegans did not activate GFP expression in the irg-4::GFP or the irg-5::GFP transcriptional reporters (Fig 5B and 5C). The presence of oleate in the growth media also did not further augment the induction of irg-5::GFP during P. aeruginosa infection (Fig 5C). In addition, oleate treatment did not extend the lifespan of wild-type C. elegans during P. aeruginosa infection (Fig 5D and S2C Table). Thus, oleate is necessary, but not sufficient, for immune activation and resistance to P. aeruginosa infection in C. elegans.

Interestingly, fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) mutant animals were also hypersusceptible to infection with the gram-positive pathogen Enterococcus faecalis (Fig 5E and S2C Table) and Serratia marcescens (Fig 5F and S2C Table), which, like P. aeruginosa, is a gram-negative bacteria. Importantly, the enhanced susceptibility of the fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) mutants to infection with E. faecalis and S. marcescens was rescued by treatment with exogenous oleate (Fig 5E and 5F). Thus, oleate is required for host resistance to diverse bacterial pathogens.

Discussion

This study defines a role for the MUFA oleate in C. elegans innate immune activation. We show that animals deficient in oleate production were hypersusceptible to killing by the bacterial pathogens P. aeruginosa, E. faecalis, and S. marcescens in a manner dependent on oleate. Oleate is among the most abundant fatty acids in cells. Thus, these data may explain how a metazoan animal limits the induction of protective immune defenses to times when the host has accumulated sufficient energy reserves to survive challenge from bacterial pathogens.

Nandakumar et al. previously identified two fatty acids, GLA and SDA, which are synthesized by the enzyme fat-3 and are required for the basal expression of immune effectors [17]. Our data indicate that oleate and these PUFAs affect immune effector expression and pathogen resistance by different mechanisms. C. elegans with a loss-of-function mutation in fat-2, the enzyme that catalyzes the first step in PUFA synthesis, induced innate immune effector genes normally and were not more susceptible to P. aeruginosa pathogenesis. It is also important to note that knockdown of fat-3 did not affect the R24-mediated induction of 16 fat-6-dependent innate immune effectors. In addition, exogenous supplementation of PUFAs to fat-6(RNAi) animals did not restore immune effector expression, whereas the addition of oleate fully complemented the induction defect of these animals. Also of note, the effect of fat-3(wa22) on susceptibility to bacterial infection was independent of oleate.

Han et al. recently found that oleate is sufficient to extend the lifespan of nematodes that were grown under standard laboratory conditions [1]. Interestingly, we found that treatment with oleate is not sufficient to provide protection during bacterial infection, but is required for proper immune gene transcription. Specifically, oleate is important for the pathogen-mediated induction of immune effectors that are downstream of the p38 MAPK PMK-1 pathway and for genes that are regulated by the bZIP transcription factor ZIP-2, which functions independently of the canonical PMK-1 pathway to mediate an early transcriptional response to P. aeruginosa infection [31]. Consistent with these data, RNAi mediated knockdown of tir-1, a component of the p38 MAPK PMK-1 signaling cassette, as well as zip-2, enhanced the susceptibility of fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) animals to P. aeruginosa infection. Thus, oleate has diverse, health-promoting effects on lifespan and pathogen resistance in C. elegans.

In plants, oleate is also required for the proper expression of immune defense genes and resistance to pathogen infection, suggesting that the role for oleate in immune activation may be strongly conserved [34,35]. However, the mechanism by which oleate regulates immune defenses is not known in either C. elegans or plants. Our supplementation studies indicate that oleate treatment itself does not activate immune gene transcription. Thus, oleate is unlikely to be a signal of immune activation in C. elegans, but rather functions as a licensing factor for the elaboration of anti-pathogen responses. Disruption of oleate biosynthesis alters membrane fluidity, which has pleiotropic consequences on membrane-bound organelles, including activating stress pathways associated with endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction [3]. Indeed, alterations of membrane fluidity have been linked to activation of G protein-coupled receptors [36,37]. Thus, changing the oleate content in C. elegans may modulate the ability of the host to mount protective defense responses, either directly or by disrupting lipid-protein interactions that are essential for immune pathway activation. Our findings present a previously unappreciated link between a highly abundant fatty acid and immune activation, which may represent an ancient connection between body energy stores and susceptibility to bacterial infection.

Materials and methods

C. elegans and bacterial strains

C. elegans strains were maintained on E. coli OP50 or HT115 bacteria on nematode growth media plates, as described [38]. The C. elegans strains used in this study were N2 Bristol [38], AU306 agIs43 [irg-4::GFP::unc-54-3’UTR; myo-2::mCherry] [21], AY101 acIs101 [pDB09.1(irg-5::GFP); pRF4(rol-6(su1006))] [39], BX156 fat-6(tm331);fat-7(wa36) [9], BX106 fat-6(tm331) [5], BX153 fat-7(wa36) [5], BX30 fat-3(wa22) [6], and BX26 fat-2(wa17) [6]. P. aeruginosa strain PA14 [3], E. faecalis strain MMH594 [40], and S. marcescens strain Db11 [41] were used in this study.

Fatty acid supplementation

Fatty acids were obtained from Nu-Chek-Prep, Inc. and were prepared as previously described [42]. Assays were performed by growing synchronized L1 worms on the indicated fatty acid or control media containing tergitol (0.1%). Unless otherwise indicated, oleate was used at a concentration of 400 or 500 μM, except for Fig 1E, which used 1 mM. Palmitoleic acid and linoleic acid were used at a concentration of 500 μM.

C. elegans bacterial infection and other assays

“Slow killing” P. aeruginosa pathogenesis assays were performed as previously described [43]. The E. faecalis [40,44] and S. marcescens [45] pathogenesis assays were performed as previously described. For the assays with fatty acid supplementation, L4 stage-matched C. elegans, raised from the L1 to the L4 stage on E. coli HT115 on media containing fatty acids or control, were transferred to standard assay plates for the indicated experiment, which were not supplemented with fatty acids. Sample sizes, mean lifespan, and p values for all trials are shown in S2 Table. The protocol for treatment of animals with 70 μM R24 has also been described [22]. The RNAi screen of 1,420 RNAi clones was previously described [21]. RNAi clones that were used in this study are from the Ahringer [46] or Vidal [47] libraries and were confirmed by sequencing.

NanoString nCounter gene expression analyses and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

The codeset used for the NanoString nCounter Gene Expression Analysis was synthesized by NanoString and contained probes for 118 C. elegans genes, which has been described previously [21,23]. Counts from each gene were normalized to three control genes: snb-1, ama-1, and act-1. The qRT-PCR studies were performed as described previously [21–23], using previously published primer sequences [8,15,21–23]. All values were normalized against the control gene snb-1. Fold change was calculated using the Pfaffl method [48].

Gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (GC-MS)

Synchronized populations of approximately 6,000 worms at the L4 stage were harvested 24 hours after exposure to 70 μM R24 or 1% DMSO control, washed with M9 buffer to remove excess bacteria, and frozen in ethanol on dry ice. Worm pellets were thawed, sonicated, and then dissolved in 1 mL of a 3:1 methanol: methylene chloride mixture with 50 μl of internal standard dissolved in hexane (17:0, Nu-Chek-Prep Inc.). While vortexing, 200 μl acetyl chloride was slowly added. Samples were subjected to methanolysis at 80°C for 1 hour. After cooling to room temperature, the sample was neutralized with 4 mL of 7% K2CO3, and fatty acid methyl esters were extracted through the addition of 2 mL of hexane. Following hexane addition, samples were vortexed and then centrifuged at 2,500 rpm for 10 minutes. The top hexane layer containing fatty acid methyl esters was transferred to a new borosilicate glass test tube and washed with 2 mL acetonitrile, vortexed, and centrifuged at 2,500 rpm for 5 min. The top hexane layer was transferred and dried under nitrogen. Fatty acid methyl esters were resuspended in 200 μl hexane, vortexed, and transferred to Agilent vials with glass insert. Fatty acid methyl esters were analyzed by GC-MS using an Agilent 6890/5972 GC-MS system outfitted with a Supelcowax 10 column as previously described [49,50]. The relative abundance of each fatty acid was determined by dividing each fatty acid by the total fatty acid pool.

Microscopy

Nematodes were paralyzed with 10 mM levamisole (Sigma), mounted on agar pads and photographed using a Zeiss AXIO Imager Z2 microscope with a Zeiss Axiocam 506mono camera and Zen 2.3 (Zeiss) software.

Statistical analyses

C. elegans survival was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences were determined with the log-rank test using OASIS 2 [51]. Other statistical tests, which are indicated in the figure legends, were performed using Prism 7 (GraphPad Software).

Supporting information

A. C. elegans carrying the irg-4::GFP immune reporter grown on control or fat-7(RNAi) bacteria and exposed to R24 or solvent control at the L4 stage. B. Wild-type C. elegans or mdt-15(tm2182) loss-of-function C. elegans grown on control media or media supplemented with oleate and exposed to R24 at the L4 stage. C. GC-MS of L4-stage animals grown on control or fat-6(RNAi) exposed to solvent control for 24 hours. Data are the average of three independent replicates with error bars showing standard deviation. Statistical analyses performed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. * p<0.05.

(TIF)

qRT-PCR was used to assess the expression of the immune effector genes irg-4, irg-5, and irg-6 in fat-6(tm331) (A) and fat-7(wa36) (B) animals exposed to the solvent control or R24 compared to wild-type. Data are the average of four independent replicates, each normalized to a control gene and presented as fold induction in R24-exposed vs. solvent control-exposed animals. Error bars show standard deviation.

(TIF)

P. aeruginosa pathogenesis assay of wild-type and the indicated mutant worms are presented. There is no significant difference between these conditions. Data are representative of two trials. Sample sizes, mean lifespan and p values for both trials are shown in S2B Table. Significance was determined using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests.

(TIF)

P. aeruginosa pathogenesis assays of wild-type and fat-3(wa22) animals grown on control media or oleate-supplemented media, as indicated. Animals were transferred at the L4 stage to plates containing P. aeruginosa. Assay plates were not supplemented with oleate. The fat-3(wa22) mutant is more susceptible to killing by P. aeruginosa (p<0.01). Oleate supplementation did not rescue the enhanced susceptibility to pathogens phenotype of the fat-3(wa22) mutant (p is not significant). Data are representative of two trials. Sample sizes, mean lifespan, and p values for all trials are shown in S2D Table. Significance was determined using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests.

(TIF)

(XLSX)

A. All trials for the pathogenesis assays presented in Fig 4. B. All trials for the pathogenesis assays presented in S3 Fig. C. All trials for the pathogenesis assays presented in Fig 5. D. All trials for the pathogenesis assays presented in S4 Fig.

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amy Walker and Cole Haynes for many helpful discussions and reagents, as well as Melanie Trombly for comments on the manuscript. Some nematode strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by R01 AI130289 (to RPW), a Child Health Research Award from the Charles H. Hood Foundation (to RPW), an Innovator Award from the Kenneth Rainin Foundation (to RPW), T32 AI007349 (to SMA), T32 AI132152 (to NDP), R01 DK101522 (to AAS) and P30 DK040561 (to AAS). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Han S, Schroeder EA, Silva-Garcia CG, Hebestreit K, Mair WB, et al. (2017) Mono-unsaturated fatty acids link H3K4me3 modifiers to C. elegans lifespan. Nature 544: 185–190. 10.1038/nature21686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen M, Flatt T, Aguilaniu H (2013) Reproduction, fat metabolism, and life span: what is the connection? Cell Metab 17: 10–19. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hou NS, Gutschmidt A, Choi DY, Pather K, Shi X, et al. (2014) Activation of the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response by lipid disequilibrium without disturbed proteostasis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111: E2271–2280. 10.1073/pnas.1318262111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, Bittner V, Criqui MH, et al. (2011) Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 123: 2292–2333. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watts JL, Browse J (2000) A palmitoyl-CoA-specific delta9 fatty acid desaturase from Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 272: 263–269. 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watts JL, Browse J (2002) Genetic dissection of polyunsaturated fatty acid synthesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 5854–5859. 10.1073/pnas.092064799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watts JL, Phillips E, Griffing KR, Browse J (2003) Deficiencies in C20 polyunsaturated fatty acids cause behavioral and developmental defects in Caenorhabditis elegans fat-3 mutants. Genetics 163: 581–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brock TJ, Browse J, Watts JL (2006) Genetic regulation of unsaturated fatty acid composition in C. elegans. PLoS Genet 2: e108 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brock TJ, Browse J, Watts JL (2007) Fatty acid desaturation and the regulation of adiposity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 176: 865–875. 10.1534/genetics.107.071860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi X, Tarazona P, Brock TJ, Browse J, Feussner I, et al. (2016) A Caenorhabditis elegans model for ether lipid biosynthesis and function. J Lipid Res 57: 265–275. 10.1194/jlr.M064808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim DH, Ewbank JJ (2018) Signaling in the innate immune response. WormBook 2018: 1–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen LB, Troemel ER (2015) Microbial pathogenesis and host defense in the nematode C. elegans. Curr Opin Microbiol 23: 94–101. 10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pukkila-Worley R (2016) Surveillance Immunity: An Emerging Paradigm of Innate Defense Activation in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog 12: e1005795 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pukkila-Worley R, Ausubel FM (2012) Immune defense mechanisms in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestinal epithelium. Curr Opin Immunol 24: 3–9. 10.1016/j.coi.2011.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Troemel ER, Chu SW, Reinke V, Lee SS, Ausubel FM, et al. (2006) p38 MAPK regulates expression of immune response genes and contributes to longevity in C. elegans. PLoS Genet 2: e183 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shapira M, Hamlin BJ, Rong J, Chen K, Ronen M, et al. (2006) A conserved role for a GATA transcription factor in regulating epithelial innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 14086–14091. 10.1073/pnas.0603424103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nandakumar M, Tan MW (2008) Gamma-Linolenic and Stearidonic Acids Are Required for Basal Immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans through Their Effects on p38 MAP Kinase Activity. PLoS Genet 4: e1000273 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson ND, Cheesman HK, Liu P, Anderson SM, Foster KJ, et al. (2019) The nuclear hormone receptor NHR-86 controls anti-pathogen responses in C. elegans. PLoS Genet 15: e1007935 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shivers RP, Pagano DJ, Kooistra T, Richardson CE, Reddy KC, et al. (2010) Phosphorylation of the conserved transcription factor ATF-7 by PMK-1 p38 MAPK regulates innate immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet 6: e1000892 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim DH, Feinbaum R, Alloing G, Emerson FE, Garsin DA, et al. (2002) A conserved p38 MAP kinase pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity. Science 297: 623–626. 10.1126/science.1073759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pukkila-Worley R, Feinbaum RL, McEwan DL, Conery AL, Ausubel FM (2014) The evolutionarily conserved mediator subunit MDT-15/MED15 links protective innate immune responses and xenobiotic detoxification. PLoS Pathog 10: e1004143 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pukkila-Worley R, Feinbaum R, Kirienko NV, Larkins-Ford J, Conery AL, et al. (2012) Stimulation of host immune defenses by a small molecule protects C. elegans from bacterial infection. PLoS Genet 8: e1002733 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheesman HK, Feinbaum RL, Thekkiniath J, Dowen RH, Conery AL, et al. (2016) Aberrant Activation of p38 MAP Kinase-Dependent Innate Immune Responses Is Toxic to Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 (Bethesda) 6: 541–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson ND, Pukkila-Worley R (2018) Caenorhabditis elegans in high-throughput screens for anti-infective compounds. Curr Opin Immunol 54: 59–65. 10.1016/j.coi.2018.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding W, Higgins DP, Yadav DK, Godbole AA, Pukkila-Worley R, et al. (2018) Stress-responsive and metabolic gene regulation are altered in low S-adenosylmethionine. PLoS Genet 14: e1007812 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taubert S, Van Gilst MR, Hansen M, Yamamoto KR (2006) A Mediator subunit, MDT-15, integrates regulation of fatty acid metabolism by NHR-49-dependent and -independent pathways in C. elegans. Genes Dev 20: 1137–1149. 10.1101/gad.1395406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goh GY, Martelli KL, Parhar KS, Kwong AW, Wong MA, et al. (2014) The conserved Mediator subunit MDT-15 is required for oxidative stress responses in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell 13: 70–79. 10.1111/acel.12154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taubert S, Hansen M, Van Gilst MR, Cooper SB, Yamamoto KR (2008) The Mediator subunit MDT-15 confers metabolic adaptation to ingested material. PLoS Genet 4: e1000021 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Gilst MR, Hadjivassiliou H, Jolly A, Yamamoto KR (2005) Nuclear hormone receptor NHR-49 controls fat consumption and fatty acid composition in C. elegans. PLoS Biol 3: e53 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goudeau J, Bellemin S, Toselli-Mollereau E, Shamalnasab M, Chen Y, et al. (2011) Fatty acid desaturation links germ cell loss to longevity through NHR-80/HNF4 in C. elegans. PLoS Biol 9: e1000599 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Estes KA, Dunbar TL, Powell JR, Ausubel FM, Troemel ER (2010) bZIP transcription factor zip-2 mediates an early response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 2153–2158. 10.1073/pnas.0914643107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liberati NT, Fitzgerald KA, Kim DH, Feinbaum R, Golenbock DT, et al. (2004) Requirement for a conserved Toll/interleukin-1 resistance domain protein in the Caenorhabditis elegans immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 6593–6598. 10.1073/pnas.0308625101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Couillault C, Pujol N, Reboul J, Sabatier L, Guichou JF, et al. (2004) TLR-independent control of innate immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans by the TIR domain adaptor protein TIR-1, an ortholog of human SARM. Nat Immunol 5: 488–494. 10.1038/ni1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kachroo A, Kachroo P (2009) Fatty Acid-derived signals in plant defense. Annu Rev Phytopathol 47: 153–176. 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mandal MK, Chandra-Shekara AC, Jeong RD, Yu K, Zhu S, et al. (2012) Oleic acid-dependent modulation of NITRIC OXIDE ASSOCIATED1 protein levels regulates nitric oxide-mediated defense signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24: 1654–1674. 10.1105/tpc.112.096768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Q, Alemany R, Casas J, Kitajka K, Lanier SM, et al. (2005) Influence of the membrane lipid structure on signal processing via G protein-coupled receptors. Mol Pharmacol 68: 210–217. 10.1124/mol.105.011692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bodhicharla R, Devkota R, Ruiz M, Pilon M (2018) Membrane Fluidity Is Regulated Cell Nonautonomously by Caenorhabditis elegans PAQR-2 and Its Mammalian Homolog AdipoR2. Genetics 210: 189–201. 10.1534/genetics.118.301272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brenner S (1974) The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolz DD, Tenor JL, Aballay A (2010) A conserved PMK-1/p38 MAPK is required in Caenorhabditis elegans tissue-specific immune response to Yersinia pestis infection. J Biol Chem 285: 10832–10840. 10.1074/jbc.M109.091629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garsin DA, Sifri CD, Mylonakis E, Qin X, Singh KV, et al. (2001) A simple model host for identifying Gram-positive virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 10892–10897. 10.1073/pnas.191378698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flyg C, Kenne K, Boman HG (1980) Insect pathogenic properties of Serratia marcescens: phage-resistant mutants with a decreased resistance to Cecropia immunity and a decreased virulence to Drosophila. J Gen Microbiol 120: 173–181. 10.1099/00221287-120-1-173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deline ML, Vrablik TL, Watts JL (2013) Dietary supplementation of polyunsaturated fatty acids in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Vis Exp 81: e50879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan MW, Mahajan-Miklos S, Ausubel FM (1999) Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa used to model mammalian bacterial pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 715–720. 10.1073/pnas.96.2.715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuen GJ, Ausubel FM (2018) Both live and dead Enterococci activate Caenorhabditis elegans host defense via immune and stress pathways. Virulence 9: 683–699. 10.1080/21505594.2018.1438025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pujol N, Link EM, Liu LX, Kurz CL, Alloing G, et al. (2001) A reverse genetic analysis of components of the Toll signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol 11: 809–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamath RS, Ahringer J (2003) Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods 30: 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rual JF, Ceron J, Koreth J, Hao T, Nicot AS, et al. (2004) Toward improving Caenorhabditis elegans phenome mapping with an ORFeome-based RNAi library. Genome Res 14: 2162–2168. 10.1101/gr.2505604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pfaffl MW (2001) A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 29: e45 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soukas AA, Kane EA, Carr CE, Melo JA, Ruvkun G (2009) Rictor/TORC2 regulates fat metabolism, feeding, growth, and life span in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev 23: 496–511. 10.1101/gad.1775409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pino EC, Webster CM, Carr CE, Soukas AA (2013) Biochemical and high throughput microscopic assessment of fat mass in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Vis Exp 73: e50180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han SK, Lee D, Lee H, Kim D, Son HG, et al. (2016) OASIS 2: online application for survival analysis 2 with features for the analysis of maximal lifespan and healthspan in aging research. Oncotarget 7: 56147–56152. 10.18632/oncotarget.11269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. C. elegans carrying the irg-4::GFP immune reporter grown on control or fat-7(RNAi) bacteria and exposed to R24 or solvent control at the L4 stage. B. Wild-type C. elegans or mdt-15(tm2182) loss-of-function C. elegans grown on control media or media supplemented with oleate and exposed to R24 at the L4 stage. C. GC-MS of L4-stage animals grown on control or fat-6(RNAi) exposed to solvent control for 24 hours. Data are the average of three independent replicates with error bars showing standard deviation. Statistical analyses performed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. * p<0.05.

(TIF)

qRT-PCR was used to assess the expression of the immune effector genes irg-4, irg-5, and irg-6 in fat-6(tm331) (A) and fat-7(wa36) (B) animals exposed to the solvent control or R24 compared to wild-type. Data are the average of four independent replicates, each normalized to a control gene and presented as fold induction in R24-exposed vs. solvent control-exposed animals. Error bars show standard deviation.

(TIF)

P. aeruginosa pathogenesis assay of wild-type and the indicated mutant worms are presented. There is no significant difference between these conditions. Data are representative of two trials. Sample sizes, mean lifespan and p values for both trials are shown in S2B Table. Significance was determined using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests.

(TIF)

P. aeruginosa pathogenesis assays of wild-type and fat-3(wa22) animals grown on control media or oleate-supplemented media, as indicated. Animals were transferred at the L4 stage to plates containing P. aeruginosa. Assay plates were not supplemented with oleate. The fat-3(wa22) mutant is more susceptible to killing by P. aeruginosa (p<0.01). Oleate supplementation did not rescue the enhanced susceptibility to pathogens phenotype of the fat-3(wa22) mutant (p is not significant). Data are representative of two trials. Sample sizes, mean lifespan, and p values for all trials are shown in S2D Table. Significance was determined using Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests.

(TIF)

(XLSX)

A. All trials for the pathogenesis assays presented in Fig 4. B. All trials for the pathogenesis assays presented in S3 Fig. C. All trials for the pathogenesis assays presented in Fig 5. D. All trials for the pathogenesis assays presented in S4 Fig.

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.