Abstract

Reproductive-age women are a fast-growing component of active-duty military personnel who experience deployment and combat more frequently than previous service-era women Veterans. With the expansion of the number of women and their roles, the United States Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs have prioritized development and integration of reproductive services into their health systems. Thus, understanding associations between deployments or combat exposures and short- or long-term adverse reproductive health outcomes is imperative for policy and programmatic development. Servicewomen and women Veterans may access reproductive services across civilian and military or Veteran systems and providers, increasing the need for awareness and communication regarding deployment experiences with a broad array of providers. An example is the high prevalence of military sexual trauma reported by women Veterans and the associated mental health diagnoses that may lead to a lifetime of high risk-coping behaviors that increase reproductive health risks, such as sexually transmitted infections, unintended pregnancies, and others. Care coordination models that integrate reproductive healthcare needs, especially during vulnerable times such as at the time of military separation and in the immediate postdeployment phase, may identify risk factors for early intervention with the potential to mitigate lifelong risks.

Keywords: women Veterans, reproductive health, deployment

Active-duty servicewomen and recently separated women Veterans are an increasing population in the United States with distinct reproductive healthcare needs. In fiscal year 2016, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) reported that 235,813 (18%) of active-duty service members were women, an increase from a low of less than 10% in previous eras. The majority of all active-duty servicewomen (98%) are of reproductive age (<45 years).1 In addition, there are currently approximately 2 million U.S. women Veterans and 40% are younger than 45 years.2 Reproductive-age women Veterans are now the fastest growing population eligible for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare services and other benefits.3

A military deployment is defined as an assignment away from the personnel’s home station to somewhere outside the continental United States and its territories. Restrictions on military occupations for servicewomen, including resultant deployment and combat exposure, were slowly removed through legislative and DOD initiatives starting in the 1990s. Combat exposure increased for servicewomen from 7% among pre-1990 women Veterans to 24% of those serving after policy changes.4 Thus, women serving in conflicts following the September 11, 2001, terror attacks, Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation New Dawn (OEF/OIF/OND), make up a unique population. For example, of the 71,504 women Veterans identified on a roster of OEF/OIF/OND service era Veterans, 69% had a single deployment and 31% had multiple deployments during their service years.5 Given the overlap of deployments and military commitments with prime reproductive years of service-women, it is imperative to provide healthcare services to optimize pregnancy planning and identify long-term risks associated with deployments and combat exposure.

How Is Healthcare Provided for Servicewomen and Women Veterans?

Healthcare for active-duty servicewomen is highly dependent on their geographic location and proximity to military hospitals or medical centers. Servicewomen may also use their military health insurance (Tricare) to access any necessary healthcare through community civilian providers. Increasingly, active-duty military personnel are seeking physical and mental healthcare from the civilian sector such as the Civilian Medical Resources Network, established in 2005.6,7 Researchers suggest this may be partly due to the “double agency” that makes military healthcare providers responsible for both patient health and responding to military command.6 Those stationed internationally may need to use country-specific services, be transported to a military hospital, or travel to the United States via “medical evacuation” for certain needs, which may impact military readiness.8

Servicewomen may separate from the military shortly after a deployment and enter the VA for postdeployment health needs. Women Veterans may access care across health systems based on private or public insurance coverage, including VA and civilian facilities. Since the enactment of a 2008 expansion law, all OEF/OIF/OND combat zone Veterans are eligible for 5 years of VA healthcare after leaving the military, regardless of education, income, or insurance status.9 Any sustained service-connected disabilities (defined as an injury or illness that was incurred or aggravated during active military service) are then individually reviewed for ongoing benefits. Access to gender-specific healthcare in VA varies by location and provider experience; thus, expansion of these services is a VA priority.10

The 2015 Study of Barriers for Women Veterans to VA Health Care11 identified significant limitations to the VA goal of comprehensive women’s healthcare. First, women Veterans may bypass the nearest VA clinic because the needed women’s services are not available.11 Second, finding transportation to specialty services was most burdensome for women with the highest levels of disability. Hence, rural VA clinics play an essential role in addressing overall health disparities for women Veterans, as rural Veterans are less likely to have access to non-VA specialty care sources compared with urban Veterans.12 And finally, longer drive timesfor women Veterans to VA facilities are associated with greater attrition from the VA.13 Disparities research in women Veteran populations is nascent and evolving, with an immense need for further research to direct healthcare access interventions.14

Women’s healthcare services in the VA are divided into primary and specialty care services. “Gender-specific primary care” includes cancer screening, human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination, preconception and contraceptive care, and menopausal support. “Specialty care,” often only available in larger medical centers or through non-VA referrals, includes pregnancy care, infertility, sterilization, sexual dysfunction, and other problem-based care. Women’s Health Clinics (WHCs) were developed in settings with a greater caseload of women Veterans and are more likely to provide “comprehensive” primary care and women’s health-specific services if they have an academic affiliation or a designated women’s health provider (DWHP).15 Despite these designations, not all primary care providers (PCPs) or DWHPs have the same knowledge-base and experience with the full spectrum of reproductive services. For example, “birth control” is listed as general care provided by PCPs under VA healthcare services for women, not specialty care.16 Yet training on comprehensive contraceptive provision is not universal, leading to access barriers for long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) or implants, which are not only the most effective but safest options for many women. In 2008, only 58% of WHCs had a gynecology specialty clinic, in which 85% of these specialty sites provided IUD insertions, compared with only 14% of sites with DWHPs only.17 As reproductive health services across the VA vary,18 the need to co-locate gynecologic services is important in high volume settings.19

Traditionally, the VA sought to provide comprehensive services within the health system and limited access to non-VA providers. As a response to reports of VA specialty care access issues, Congress passed the Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act of 2014 (VACAA) and significantly changed the care delivery process across the VA.20 The VACAA and May 2015 follow-up legislation allow Veterans waiting more than 30 days for VA care, those residing more than 40 miles from a VA facility, and those with “unusual and excessive burden for travel” to receive healthcare with “Choice” contracted providers. Veterans may receive community care that is arranged and paid for by VA. As the number of women Veterans has increased in the VA, partnerships with non-VA providers have filled reproductive healthcare gaps that the VA was not set-up to offer. Unfortunately, the attempts to expand access to care through civilian providers occurred without a feasibility assessment. A study exploring quality and coordination of non-VA/Choice care found the VACAA was enacted too rapidly without adequate preparation, community networks were poorly established, and care was increasingly delayed due to scheduling or communication challenges.21 Additionally, referring out reproductive health services meant women Veterans were cared for by civilian providers who may be less familiar with Veteran, and especially deployment-related experiences and needs.22 The newly passed VA Mission Act of 2018 will attempt to address some of these issues, including providing continuing education for community providers who serve Veterans.23 When uninsured women Veterans attempt to access civilian reproductive services, their access is often limited by state-level legislative restrictions and funding cuts that have closed or altered services in publicly funded family planning clinics.24 Unfortunately, VA funding for community care will not lead to greater reproductive health access for rural women without local civilian services.

What Is Reproductive Health?

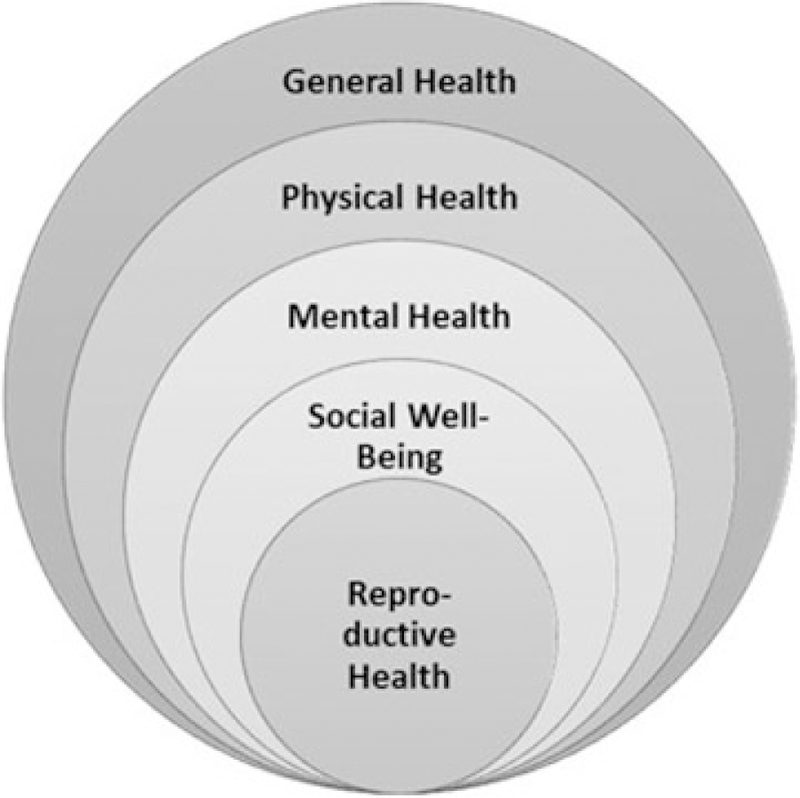

The United Nations defines “reproductive health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being,” and not “merely the absence of reproductive disease or infirmity”25 (Fig. 1). Although most reproductive health problems arise during the reproductive years, “in old age, general health continues to reflect earlier reproductive life events.”25,26 Reproductive services include pregnancy care, family planning, care for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), protection from and response to sexual and gender-based violence, preventive health services (gynecologic exams, HPV vaccination, bone screening, and cancer screening), and specialty care for infertility, sexual dysfunction, pelvic pain, and other pathology.27 Specific to women Veterans, Katon et al categorized reproductive conditions to assess their frequency within the VA in FY2010.28 The most common reproductive diagnoses identified in women younger than 45 years included menstrual and pain disorders, STIs and vaginitis, urinary conditions, and pregnancy-related diagnoses. As most deployments happen in reproductive-age women, the focus of this article is on needs for those younger than 45 years (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

The components of women’s health. (Adapted from Guidelines on Reproductive Health for the UN Resident Coordinator System. The United States Population Information Network (POPIN). 2001. Available at: http://www.un.org/popin/unfpa/taskforce/guide/iatfreph.gdl.html).

Table 1.

Reproductive health needs across a life and career course

| Age | 18–45 y | 45–64 y | 65+ y |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life stage | Childbearing → Perimenopause → Menopause | ||

| Career stage | Military (deployment/combat) → Separation → Veteran status | ||

| Reproductive needs | Menstrual health contraception Pregnancy Infertility |

||

| Cervical cancer screening | |||

| Menopause | |||

| Osteoporosis | |||

| Breast cancer screening | |||

| Sexual dysfunction Sexually transmitted infections Pelvic floor disorders Urinary conditions Gynecologic basic and specialty care | |||

Source: Adapted from the State of Reproductive Health in Women Veterans. Veterans Healthcare Administration. Available at: https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/docs/SRH_FINAL.pdf.

How Does Deployment Impact Reproductive Health?

Sexual Trauma

An understanding of postdeployment reproductive health must be framed by the high prevalence of military sexual trauma (MST) in this population. MST encompasses both sexual assault and repeated, threatening sexual harassment experienced during military service. The VA has a systematic approach to screening for MST during primary care and mental health visits. An electronic health record clinical reminder prompts providers with the following questions: “While you were in the military, (1) did you receive uninvited and unwanted sexual attention, such as touching, cornering, pressure for sexual favors, or verbal remarks? (2) Did someone ever use force or threat of force to have sexual contact with you against your will?” Responses may be “yes,” “no,” or “declines” and an affirmative response will link the Veteran with MST-specific services. Approximately 22% of women Veterans enrolled in the VA report MST.29 Women who deployed and reported combat experiences were significantly more likely to report sexual harassment (odds ratio [OR], 2.20; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.84–2.64) or both sexual harassment and sexual assault (OR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.61–3.78) compared with nondeployers.30 The Millennium Cohort Study is a prospective study of over 200,000 Veterans designed to evaluate the long-term impact of military exposures on a variety of health outcomes. One study leveraged these data to explore health and occupational outcomes among military women with recent sexual trauma. The authors found recent harassment was associated with demotion, and both harassment and assault were associated with poorer physical health, after controlling for other characteristics and prior trauma history.31 MST is independently associated with homelessness, a long-term reintegration consequence that adversely impacts reproductive health outcomes for women. As trauma experiences can result in lifelong psychological stress, adverse reproductive outcomes and reintegration experiences such as homelessness,32 screening, and provider awareness are imperative.33

Pregnancy

Understanding the causal relationship between military service exposures and deployment on MST and adverse pregnancy outcomes is important for identifying target risk factors that may ultimately contribute to the high prevalence of chronic medical, psychiatric, and substance abuse conditions among women Veterans.34 Mitigating risk is also important for VA financial planning, due to an increasing number of potentially high-risk deliveries funded by the VA and most are to women Veterans with service-connected disabilities.35 Unfortunately, studies of associations between deployment and adverse pregnancy outcomes are fraught with methodologic limitations, including small sample sizes, inappropriate comparison/reference group, lack of prospective data collection, and measurement error from reliance on self-reported data.

Early research in OEF/OIF/OND women Veterans analyzed self-reported data and found conflicting associations between military service and adverse pregnancy outcomes, including miscarriage and birth defects, heightening concerns regarding potential long-term environmental exposures on reproductive health.36–38 A more recent study using birth records showed no increased risk of birth defects in infants of OEF/OIF Veterans by deployment history.39 In addition to self-reported outcomes, several studies used women who never deployed as a comparison group. Araneta et al found that adverse pregnancy outcomes were similar among OEF/OIF/OND-exposed versus non-exposed pregnancies among OEF/OIF/OND Veterans. However, for postwar conceptions, the authors found spontaneous abortions (deployed: 23%, nondeployed: 9%; adjusted OR [aOR] = 2.9, 95% CI, 1.9–4.6) and ectopic pregnancies (deployed: 11%, nondeployed 1%; aOR = 7.7, 95% CI, 3.0–19.8) were elevated for OEF/OIF/OND Veterans, while controlling for age, race, education, and marital status.38

Other studies analyzed the timing of pregnancies in relation to deployments. One found that delivering within 6 months of deployment (compared with no prior deployments) increased risk of spontaneous preterm birth (aOR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.5–2.9). Longer periods of time between deployment and delivery (compared with no prior deployments) were not found to be associated with spontaneous preterm birth and the authors concluded that optimizing pregnancy timing and predeployment contraception could mitigate preterm birth risk.40 Another analyzed 2,276 live births and found that compared with pregnancies before deployment, pregnancies among nondeployed appeared to have greater risk of preterm birth (nondeployed: aOR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.25–3.72) compared with after deployment (aOR, 1.90; 95% CI, 0.90–4.02). A similar pattern was observed for low birth weight. The authors posited that comparisons between nondeployed and deployed are flawed due to confounding factors, such as predeployment behavioral and/or medical characteristics.41 Shaw et al explored relationships between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and adverse pregnancy outcomes through use of a database of all VA-covered deliveries from 2000 to 2012. The team found associations between women Veterans diagnosed with PTSD and gestational diabetes (RR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2–1.7), preeclampsia (RR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1–1.6), prolonged hospitalization (RR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.01–1.4), and repeat hospitalization (RR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2–1.6).42 In sum, data confirming an independent association between deployment or combat and adverse pregnancy outcomes are inconclusive and most likely confounded by other psychological stress or comorbidities.

Reproductive Planning and Contraception

Reproductive planning is essential for active-duty servicewomen to avoid unintended pregnancy at the time of deployment or other service commitments, as well as ensuring pregnancy occurs when a woman’s health is optimized. Despite this need, approximately 59% of active-duty pregnancies are unintended, resulting in 12% of all U.S. servicewomen experiencing an unintended pregnancy each year.43 Unintended pregnancy remains an issue in recent conflicts during deployment, with one longitudinal study reporting 10.8% of women in an OIF Army combat brigade requiring medical evacuation for pregnancy reasons.44 Women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during deployment who desire abortion care typically must also receive a medical evacuation and pay for the procedure out of pocket unless it is a result of rape or incest, or if continuation of the pregnancy endangers the woman’s life.45 As women denied a wanted abortion are more likely to experience economic hardship and insecurity in subsequent years than those who receive desired abortion care,46 further research on the effects of restrictive military policies and insurance coverage is needed. Additionally, a study of women Veterans who received care in the VA found a history of deployment was associated with increased need for abortion services in the previous 5 years (aOR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.04–6.02).47 Opportunities to support reproductive planning persist as women transition into Veteran services.

The most effective means to improve reproductive planning is through consistent use of contraception. A survey study of active-duty servicewomen and Veterans with a deployment history found that 63% of respondents reported contraception use during deployment for pregnancy prevention and/or noncontraceptive benefits, such as menstrual suppression.48 Method access varied somewhat with women reporting difficulty obtaining LARC methods or being discouraged from use, while those on short-acting methods, such as the contraceptive ring, found continuation difficult due to insufficient supplies at their deployment location. Even with abstinence during deployment, these issues place women at risk for unintended pregnancy during leave or postdeployment times when immediate access to care may be challenging.

Once women establish care in the VA, all contraceptive methods are covered, but access to LARC methods is based on provider experience. Women Veterans with a history of substance use disorders and mental health needs have decreased uptake of LARC methods and adherence to short-acting contraceptive methods as compared with other women Veterans.49,50 Women Veterans who report of a history of MST and those with a DWHP are most likely to access the methods of their choice.51 Women Veterans who experience homelessness are more likely to utilize LARC methods than housed women Veterans (9.3 vs. 5.4%; p > 0.001) within the VA. Despite this finding, ongoing efforts to prioritize reproductive planning are needed, due to the high prevalence of chronic health conditions in this population.34 Ensuring women Veterans who are transitioning into the VA postdeployment are screened for reproductive health needs may decrease access barriers and risk of unintended pregnancy in a vulnerable time period.

Infertility

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine defines infertility as failure to conceive within 12 months of unprotected intercourse, unless medical history, age, or physical findings prompt an earlier evaluation. Approximately 10% of U.S. women aged 15 to 44 years in the general population have difficulty getting pregnant or staying pregnant.52 The effects of deployment on fertility are not well established, despite concerns for environmental risks and combat injuries. One study of Iraq and Afghanistan women Veterans found an increased risk of infertility associated with mental health diagnoses while controlling for deployment history.5 Another reported the risk of infertility diagnoses increased with deployment length and recommended consideration of shorter assignment times for women.53 In response to Veteran concerns and thelimited and variable research findings, the VA established an infertility policy to expand basic coverage for fertility evaluation and treatment including in vitro fertilization procedures, if the Veteran’s cause of infertility is service connected.54 Establishing service connectivity is difficult, except in the rare setting of a physical trauma impacting reproductive organs, as data do not support an association between deployment and diagnosed infertility.

Menstrual Health

Painful menses or dysmenorrhea and endometriosis are common diagnoses in women Veterans in the VA.28 It is difficult to establish the effects of deployment and combat exposure on these disorders or the timing of their onset, except that many women who use contraception during deployment may do so for menstrual suppression related to symptoms that started prior to their assignment.48 Menstrual symptoms during deployment appear to vary by race and ethnicity with one survey study finding a range, with 6% of African American women and up to 21% of Asian American women reporting severe dysmenorrhea.55 Similar to infertility, dysmenorrhea and endometriosis are associated with mental health diagnoses when controlling for deployment history.5 As these disorders may lead to chronic pain and poor quality of life, mental health associations are not surprising, and screening women postdeployment and at VA enrollment could lead to early interventions, such as pelvic floor physical therapy, which decrease risk of long-term disability.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Data on the postdeployment needs related to cervical cancer and STI screening are limited, but closely linked to high-risk sexual behaviors and MST prevalence in deployed women Veterans. High-risk sexual behaviors in active-duty military personnel include inconsistentcondom use, multiple partners, and alcohol consumption.56 Many studies on STI rates in active-duty personnel included military recruits whose exposures represent pre-enlisting behaviors. One study specific to deployment found active duty servicewomen deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan had higher gonorrhea and chlamydia rates than their male peers.57 Predeployment education on high-risk sexual behaviors and provision of condoms in the field could decrease risk of exposure and the potential for long-term adverse outcomes of chronic pelvic pain and infertility.58

Studies of active-duty military personnel suggest an increased rate of cervical dysplasia compared with civilian populations; yet methodologic differences, including use of retrospective billing data, differences in screening and follow-up rates, and inclusion of all military insurance beneficiaries, limit direct comparisons.59–61 Published studies predominantly occurred in the era prior to routine vaccination against HPV and, as cervical dysplasia can occur several years after a high-risk exposure, updated studies are needed to estimate the current prevalence. Regardless, ensuring active-duty servicewomen and women Veterans are fully vaccinated and up to date on cervical cancer screening across their career transitions will decrease risk of progression to cervical cancer in a potentially higher-risk population.

Sexual Dysfunction

Female sexual function is complex and multifaceted, and trauma and mental health diagnoses, such as PTSD, incurred during deployment and combat exposure are closely associated with sexual dysfunction.62,63

Women Veterans in the VA who experienced combat frequently report sexual health issues, with low libido as the most common.64 Blais et al65 explored associations between sexual dysfunction and suicidal ideation in servicewomen and women Veterans. Symptoms consistent with PTSD and depression and lower sexual function were all associated with suicidal ideation, specifically difficulties with sexual arousal (aOR, 0.87, 95% CI, 0.79–0.97) and sexual satisfaction (aOR, 0.85, 95% CI, 0.75–0.96). As sexual health impacts relationship satisfaction and overall quality of life, screening for dysfunction and early interventions may decrease progressive mental health risks. Additionally, universal MST screening in the VA is one important intervention to engage women in treatment and address the complex relationships between sexual trauma, PTSD, and sexual dysfunction.

Urinary Conditions

Deployment conditions and environment impact feminine hygiene practices in the field and can lead to ongoing postdeployment health issues, including urinary symptoms and urinary tract infections (UTIs).66 While data on whether there is a true increased risk of UTIs are limited,66,67 subjective symptoms of dysuria or pruritus that might also be a result of vaginitis can impact work and quality of life.68 Many servicewomen are reluctant to seek care and may risk progression to kidney disease with untreated infection.68 As part of predeployment training, the Women’s Health Promotion Program was developed to educate servicewomen on hygiene in austere environments, including use of a female urinary diversion device. One year after program implementation, the rates of urinary and vaginal infections had declined.69 Additionally, self-treatment kits for urinary and vaginal infections show promise,70 but may not adequately treat the cause of ongoing symptoms. Addressing any genitourinary symptoms postdeployment should be a priority to avoid any further delay in appropriate care. Military experiences may put women Veterans at risk for chronic urinary issues, as urinary conditions remain a top diagnosis of women Veterans seeking care within the VA.28,71

Pelvic Floor Disorders

Pelvic floor disorders encompass urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse which typically occur in older women, but may be related to pregnancy and delivery. Military deployments and combat exposures could theoretically increase risk of urinary incontinence and prolapse due to strenuous training, heavy lifting, and activities necessitating recurrent Valsalva techniques. Despite these service-associated risks, data on these associations are limited72 and are confounded by other risk factors by the time women are Veterans.71,73 Investing in pelvic floor physical therapists in the VA with experience in traumasensitive care can prevent progression of many pelvic floor disorders and improve the quality of life for women Veterans experiencing symptoms across their lifespan.

How Do Postdeployment Comorbidities Impact Reproductive Health?

Physical Health

Military deployments occur in young, physically fit servicewomen, but injuries that commonly occur may impact postdeployment physical health and long-term quality of life. Gender differences in the approach to military physical training and the risk for injury have been described.74 One study in deployed servicewomen found 36% sustained a musculoskeletal injury, most commonly affecting the knee or low back.75 These injuries could lead to chronic pain and associated opioid dependence without early and appropriate intervention. Other adverse health conditions are associated with deployment history. According to some studies of OEF/OIF/OND Veterans, multisystem medically unexplained symptoms, such as fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic fatigue syndrome, among others, may be at least twice as prevalent among female (8.4%) versus male (4.2%) Veterans.76–78 Several studies among civilian populations suggest that these conditions, broadly termed “chronic multisymptom illness,” may be associated with a higher risk of adverse reproductive health outcomes,79–81 but there are limited studies of these associations among military personnel. Another understudied area, but one with significant risks for mental and reproductive health, is traumatic brain injury (TBI) in servicewomen. While women make up a minority of military-associated TBI diagnoses, they are more likely to experience long-term symptoms then men,82 and may be more likely to experience their TBI through intimate partner violence rather than combat injury during their service years.83 Postdeployment physical examinations need to include a level of concern for more “mild” physical injuries that may lead to differential outcomes for women, including pelvic floor disorders and sexual dysfunction, which impact long-term quality of life.

Mental Health

Following the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, it became evident that women tend to respond differently to combat and injury versus their male counterparts, often based on predeployment stressors and histories of interpersonal trauma.84,85 The Millennium Cohort Study included 17,481 women who served from 2001 to 2008 and study researchers found those who were deployed and had combat exposures were more likely to report mental health symptoms or diagnoses than nondeployed women (aOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.65–2.20).86 Additionally, deployed women reporting combat exposures were more likely to report new-onset disordered eating (aOR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.02–3.11) compared with women who deployed but did not report combat exposures.87 These mental health issues can influence reproductive health risks and carry across their careers and into the VA. Of all women Veterans, those of reproductive age with mental health disorders experience the highest rates of VA healthcare utilization.88

Trauma and stressors could impact pregnancy outcomes and this area remains understudied in women with deployment histories. One study found that deployment with combat exposure after childbirth was associated with a higher risk of maternal depression compared with nondeployed women (aOR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.17–3.43), whereas deployment with combat exposure before childbirth was not associated with a statistically significant higher risk of maternal depression (aOR, 1.27; 95% CI, 0.83–1.95).89 To address care needs unique to women Veterans, Shivakumar et al described the interrelated factors for optimal perinatal health, which include deployment and postdeployment factors (combat stressors, MST, etc.), pregnancy and postpartum factors (pregnancy intention, parity, risks of postpartum depression, etc.), and psychiatric conditions (PTSD, premilitary abuse, etc.).90 Preconception consultation, both during active duty and into Veteran health services, is important to integrate military service exposures and weigh the risks and benefits of treatment options during pregnancy compared with the risk of worsening mental health during pregnancy and postpartum.

Social Well-Being

Postdeployment reintegration for women can be challenging and adversely impact reproductive goals. In one study, women reported avoidance of speaking about their military experiences. They identified disrupted relationships with family and friends and difficulty reestablishing their household roles. Their coping methods varied, but included negative approaches (substance use, social isolation, and weight gain/loss) and positive choices, such as reaching out to military peers and engaging in therapy.91 A small online survey found support groups and social networks for Veterans tend to be more accessible for men, especially those who experienced combat. Women and those without combat exposure may be more socially isolated than men following military service or deployment resulting in potential barriers to seeking help and service provision in this vulnerable population.92 The negative coping strategies can be associated with high-risk sexual behaviors, unintended pregnancy, and subsequent adverse pregnancy outcomes; thus, the need for evidence on postdeployment reintegration strategies is important for reproductive health outcomes.

Women Veterans are four times more likely to experience homelessness than civilian women and trauma experiences during military service, including MST, are known risk factors in this vulnerable population.93,94 Homeless women experience a high rate of unintended pregnancy that can adversely affect their mental health and ability to obtain housing.95 Prenatal homelessness is also an independent risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as preterm birth.96 Homeless women have low contraceptive utilization, are at high risk for sexual exploitation, and have a hard time prioritizing reproductive healthcare due to competing demands.97,98 Women Veterans are highly reliant upon the VA for reproductive health needs; however, services vary widely across the country in non-VA homeless healthcare organizations. Integration of reproductive health screening into VA homeless services is essential to meet acute needs in this high-risk population.

Research Gaps and Conclusion

Reproductive health research in servicewomen and women Veterans is a high priority due to the minority status of women in the military and need to expand services. There is particular interest in the intersection of needs of women and National Institutes of Health (NIH) health disparity populations such as racial/ethnic minorities, rural residents, those from low socioeconomic strata, and gender minorities. Fortunately, available data do not reveal any direct causal relationships between deployments or combat and adverse reproductive outcomes, albeit based on studies with methodological limitations, including small study sizes, study design limitations, and residual or uncontrolled confounding including from mental and physical comorbidities. What is clear in previous research is that reproductive health and other health outcomes are not independent events, supporting the United Nations’ integrative definition of reproductive health25 (Fig. 1). The effect of deployment on mental and physical health is a large part of reproductive issues, such as sexual dysfunction and chronic pelvic pain. Adverse mental and physical health conditions may confound or mediate associations of military deployment-related exposures and reproductive health and lead to challenges in diagnosis and treatment of certain aspects of reproductive health for servicewomen and women Veterans. The trauma some women experience prior to their military enlistment is also a potential risk factor for other adverse life events, especially revictimization during or after their service, and yet data on best screening options for resilience and predeployment mental health are sparse. Education interventions on reproductive health and planning for both men and women during their service differ by military branch and need evidence-based standardization to mitigate high-risk sexual behaviors. Programmatic evaluation on efforts to decrease MST could be highly impactful, due to the clear associations with all adverse health outcomes. Development of healthcare provider training and implementation of comprehensive and integrative care coordination programs will make knowledgeable women’s healthcare providers more widely and readily available across military and Veteran services, resulting in engagement of women in essential preventive care. Finally, improving military or Veteran healthcare services will not address the civilian family planning legislative restrictions that led to geographic gaps across the United States in comprehensive reproductive health services. As current legislation shifts to more non-VA civilian health care funding,23 many vulnerable women Veterans in rural settings will lack clinic or provider options for covered reproductive services.24 Acknowledging the vital role reproductive health plays in a woman’s life and general health is necessary to integrate services across healthcare touchpoints.

Acknowledgments

L.M.G.: Received support from NIH/NICHD grant IK12HD085 816 (PI: Silver).

A.V.G.: Received support from VA HSR&D grant no. IIR 12–084 (PI: Gundlapalli) and VA Salt Lake City Center of Innovation Award no. I50HX001240 from the Health Services Research and Development of the Office of Research and Development of the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

A.F.M.: Received support from VA CDA 1 IK2 RX002324–01A1.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position or policy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

References

- 1.United States Department of Defense. Population Representation in the Military Services, 2016. Available at: https://www.cna.org/pop-rep/2016/summary/summary.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2018

- 2.National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Age/gender Population Table 2016. Available at: https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_Population.asp. Accessed June 4, 2018

- 3.Friedman SA, Phibbs CS, Schmitt SK, Hayes PM, Herrera L, Frayne SM. New women veterans in the VHA: a longitudinal profile. Womens Health Issues 2011;21(4, Suppl):S103–S111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patten E, Parker K. Women in the U.S. Military: Growing Share, Distinctive Profile 2011. Available at: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2011/12/women-in-the-military.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2018

- 5.Cohen BE, Maguen S, Bertenthal D, Shi Y, Jacoby V, Seal KH. Reproductive and other health outcomes in Iraq and Afghanistan women veterans using VA health care: association with mental health diagnoses. Womens Health Issues 2012;22(05):e461–e471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waitzkin H, Cruz M, Shuey B, Smithers D, Muncy L, Noble M. Military personnel who seek health and mental health services outside the military. Mil Med 2018;183(5–6):e232–e240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wooten NR, Brittingham JA, Pitner RO, Tavakoli AS, Jeffery DD, Haddock KS. Purchased behavioral health care received by military health system beneficiaries in civilian medical facilities, 2000–2014. Mil Med 2018;183(7–8):e278–e290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christopher LA, Miller L. Women in war: operational issues of menstruation and unintended pregnancy. Mil Med 2007;172(01): 9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United States Veterans Administration Health Care. Combat Veteran Eligibility 2011. Available at: https://www.va.gov/healthbenefits/assets/documents/publications/IB-10-438_Combat_Veteran_Eligibility.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2018

- 10.Yano EM, Bastian LA, Frayne SM, et al. Toward a VA women’s health research agenda: setting evidence-based priorities to improve the health and health care of women veterans. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21(Suppl 3):S93–S101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Study of Barriers for Women Veterans to VA Health Care April 2015. Available at: http://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/index.asp. Accessed March 3, 2018

- 12.Cordasco KM, Mengeling MA, Yano EM, Washington DL. Health and health care access of rural women veterans: findings from the National Survey of Women Veterans. J Rural Health 2016;32(04): 397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman SA, Frayne SM, Berg E, et al. Travel time and attrition from VHA care among women veterans: how far is too far? Med Care 2015;53(04, Suppl 1):S15–S22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter A, Borrero S, Wessel C, Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Corbelli J; VA Women’s Health Disparities Research Workgroup. Racial and ethnic health care disparities among women in the Veterans affairs healthcare system: a systematic review. Womens Health Issues 2016;26(04):401–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy SM, Rose DE, Burgess JF Jr, Charns MP, Yano EM. The role of organizational factors in the provision of comprehensive women’s health in the Veterans health administration. Womens Health Issues 2016;26(06):648–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Women Veterans Health Care 2015; Available at: http://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/womenshealthservices/healthcare_about.asp. Accessed August 19, 2016

- 17.Seelig MD, Yano EM, Bean-Mayberry B, Lanto AB, Washington DL. Availability of gynecologic services in the department of veterans affairs. Womens Health Issues 2008;18(03):167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katon J, Reiber G, Rose D, et al. VA location and structural factors associated with on-site availability of reproductive health services. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28(Suppl 2):S591–S597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Hamilton AB, Cordasco KM, Yano EM. Women veterans’ healthcare delivery preferences and use by military service era: findings from the National Survey of Women Veterans. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28(Suppl 2):S571–S576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Veterans Affairs. Expanded access to non-VA care through the Veterans Choice Program. Interim final rule. Fed Regist 2015;80(230):74991–74996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattocks KM, Mengeling M, Sadler A, Baldor R, Bastian L. The Veterans Choice Act: a qualitative examination of rapid policy implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care 2017;55(Suppl 7(Suppl 1):S71–S75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 547: Health care for women in the military and women veterans. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120(06):1538–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.United States Senate Committee on Veteran Affairs. The VA Mission Act of 2018. Available at: https://www.veterans.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/OnePager_TheVAMISSIONActof2018.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2018

- 24.Gawron L, Pettey WBP, Redd A, Suo Y, Turok DK, Gundlapalli AV. The “safety net” of community care: leveraging GIS to identify geographic access barriers to Texas family planning clinics for homeless women Veterans. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2018;2017:750–759 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.United States Population Information Network (POPIN). Guide-lines on Reproductive Health for the UN Resident Coordinator System 2001. Available at: http://www.un.org/popin/unfpa/taskforce/guide/iatfreph.gdl.html. Accessed March 20, 2017

- 26.Louis GB, Platt R. Reproductive and Perinatal Epidemiology New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 27.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for Women’s Health Care: A Resource Manual 2014. Available at: http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Guidelines-for-Womens-Health-Care. Accessed March 20, 2017

- 28.Katon JG, Hoggatt KJ, Balasubramanian V, et al. Reproductive health diagnoses of women veterans using department of Veterans Affairs health care. Med Care 2015;53(04, Suppl 1):S63–S67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimerling R, Gima K, Smith MW, Street A, Frayne S. The Veterans Health Administration and military sexual trauma. Am J Public Health 2007;97(12):2160–2166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leardmann CA, Pietrucha A, Magruder KM, et al. ; Millennium Cohort Study Team. Combat deployment is associated with sexual harassment or sexual assault in a large, female military cohort. Womens Health Issues 2013;23(04):e215–e223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Millegan J, Milburn EK, LeardMann CA, et al. Recent sexual trauma and adverse health and occupational outcomes among U.S. service women. J Trauma Stress 2015;28(04):298–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brignone E, Gundlapalli AV, Blais RK, et al. Differential risk for home-lessness among US male and female Veterans with a positive screen for military sexual trauma. JAMA Psychiatry 2016;73(06):582–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yonkers KA, Smith MV, Forray A, et al. Pregnant women with posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of preterm birth. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71(08):897–904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gawron LM, Redd A, Suo Y, Pettey W, Turok DK, Gundlapalli AV. Long-acting reversible contraception among homeless women Veterans With chronic health conditions: a retrospective cohort study. Med Care 2017;55(Suppl 9(Suppl 2):S111–S120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mattocks KM, Frayne S, Phibbs CS, et al. Five-year trends in women veterans’ use of VA maternity benefits, 2008–2012. Womens Health Issues 2014;24(01):e37–e42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang H, Magee C, Mahan C, et al. Pregnancy outcomes among U.S. Gulf War veterans: a population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. Ann Epidemiol 2001;11(07):504–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wells TS, Wang LZ, Spooner CN, et al. Self-reported reproductive outcomes among male and female 1991 Gulf War era US military veterans. Matern Child Health J 2006;10(06):501–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Araneta MR, Kamens DR, Zau AC, et al. Conception and pregnancy during the Persian Gulf War: the risk to women veterans. Ann Epidemiol 2004;14(02):109–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bukowinski AT, DeScisciolo C, Conlin AM, K Ryan MA, Sevick CJ, Smith TC. Birth defects in infants born in 1998–2004 to men and women serving in the U.S. military during the 1990–1991 Gulf War era. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2012;94(09):721–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaw JG, Nelson DA, Shaw KA, Woolaway-Bickel K, Phibbs CS, Kurina LM. Deployment and preterm birth among US Army soldiers. Am J Epidemiol 2018;187(04):687–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katon J, Cypel Y, Raza M, et al. Deployment and adverse pregnancy outcomes: primary findings and methodological considerations. Matern Child Health J 2017;21(02):376–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaw JG, Asch SM, Katon JG, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and antepartum complications: a novel risk factor for gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2017;31 (03):185–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindberg LD. Unintended pregnancy among women in the US military. Contraception 2011;84(03):249–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belmont PJ Jr, Goodman GP, Waterman B, DeZee K, Burks R, Owens BD. Disease and nonbattle injuries sustained by a U.S. Army Brigade Combat Team during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Mil Med 2010;175(07):469–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.TRICARE. Covered Service 2018; Available at: https://www.tricare.mil/CoveredServices/IsItCovered/Abortions. Accessed June 18, 2018

- 46.Foster DG, Biggs MA, Ralph L, Gerdts C, Roberts S, Glymour MM. Socioeconomic outcomes of women who receive and women who are denied wanted abortions in the united states. Am J Public Health 2018;108(03):407–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwarz EB, Sileanu FE, Zhao X, Mor MK, Callegari LS, Borrero S. Induced abortion among women veterans: data from the ECUUN study. Contraception 2018;97(01):41–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grindlay K, Grossman D. Contraception access and use among U.S. servicewomen during deployment. Contraception 2013;87(02): 162–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Callegari LS, Zhao X, Nelson KM, Borrero S. Contraceptive adherence among women Veterans with mental illness and substance use disorder. Contraception 2015;91(05):386–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Callegari LS, Zhao X, Nelson KM, Lehavot K, Bradley KA, Borrero S. Associations of mental illness and substance use disorders with prescription contraception use among women veterans. Contraception 2014;90(01):97–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goyal V, Mattocks K, Bimla Schwarz E, et al. Contraceptive provision in the VA healthcare system to women who report military sexual trauma. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23(09):740–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Infertility Available at: https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/infertility. Accessed June 20, 2018

- 53.Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center (AFHSC). Health of women after wartime deployments: correlates of risk for selected medical conditions among females after initial and repeat deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq, active component, U.S. Armed Forces. MSMR 2012;19(07):2–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Infertility Treatment Available at: https://www.va.gov/COMMUNITYCARE/programs/veterans/ivf.asp. Accessed June 21, 2018

- 55.Deuster PA, Powell-Dunford N, Crago MS, Cuda AS. Menstrual and oral contraceptive use patterns among deployed military women by race and ethnicity. Women Health 2011;51(01):41–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meadows SO, Engel CC, Collins RL, Beckman RL, et al. 2015 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS) Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2018 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aldous WK, Robertson JL, Robinson BJ, et al. Rates of gonorrhea and chlamydia in U.S. military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan (2004–2009). Mil Med 2011;176(06):705–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mathias SD, Kuppermann M, Liberman RF, Lipschutz RC, Steege JF. Chronic pelvic pain: prevalence, health-related quality of life, and economic correlates. Obstet Gynecol 1996;87(03):321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ollayos CW, Peterson M. Relative risks for squamous intraepithelial lesions detected by the Papanicolaou test among Air Force and Army beneficiaries of the Military Health Care System. Mil Med 2002;167(09):719–722 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stany MP, Bidus MA, Reed EJ, et al. The prevalence of HR-HPV DNA in ASC-US Pap smears: a military population study. Gynecol Oncol 2006;101(01):82–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Insinga RP, Glass AG, Rush BB. Diagnoses and outcomes in cervical cancer screening: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;191(01):105–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tran JK, Dunckel G, Teng EJ. Sexual dysfunction in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Sex Med 2015;12(04):847–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cosgrove DJ, Gordon Z, Bernie JE, et al. Sexual dysfunction in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Urology 2002;60(05):881–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Helmer DA, Beaulieu GR, Houlette C, et al. Assessment and documentation of sexual health issues of recent combat veterans seeking VA care. J Sex Med 2013;10(04):1065–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blais RK, Monteith LL, Kugler J. Sexual dysfunction is associated with suicidal ideation in female service members and veterans. J Affect Disord 2018;226:52–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lowe NK, Ryan-Wenger NA. Military women’s risk factors for and symptoms of genitourinary infections during deployment. Mil Med 2003;168(07):569–574 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Czerwinski BS, Wardell DW, Yoder LH, et al. Variations in feminine hygiene practices of military women in deployed and noncombat environments. Mil Med 2001;166(02):152–158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nielsen PE, Murphy CS, Schulz J, et al. Female soldiers’ gynecologic healthcare in Operation Iraqi Freedom: a survey of camps with echelon three facilities. Mil Med 2009;174(11):1172–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Trego LL, Steele NM, Jordan P. Using the RE-AIM model of health promotion to implement a military women’s health promotion program for austere settings. Mil Med 2018;183(Suppl 1): 538–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ryan-Wenger NA, Lowe NK. Evaluation of training methods required for military women’s accurate use of a self-diagnosis and self-treatment kit for vaginal and urinary symptoms. Mil Med 2015;180(05):559–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anger JT, Saigal CS, Wang M, Yano EM; Urologic Diseases in America Project. Urologic disease burden in the United States: veteran users of Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare. Urology 2008;72(01):37–41, discussion 41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Larsen WI, Yavorek T. Pelvic prolapse and urinary incontinence in nulliparous college women in relation to paratrooper training. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2007;18(07):769–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sohn MW, Zhang H, Taylor BC, et al. ; Urologic Diseases in America Project. Prevalence and trends of selected urologic conditions for VA healthcare users. BMC Urol 2006;6:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Allison KF, Keenan KA, Sell TC, Abt JP, Nagai T, Deluzio J, McGrail M, Lephart SM. Musculoskeletal, biomechanical, and physiological gender differences in the US military. US Army Med Dep J 2015; Apr-Jun:22–32 [PubMed]

- 75.Roy TC, Piva SR, Christiansen BC, et al. Description of musculoskeletal injuries occurring in female soldiers deployed to Afghanistan. Mil Med 2015;180(03):269–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mohanty AF, Helmer DA, Muthukutty A, et al. Fibromyalgia syndrome care of Iraq- and Afghanistan-deployed Veterans in Veterans Health Administration. J Rehabil Res Dev 2016;53(01): 45–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mohanty AF, Muthukutty A, Carter ME, et al. Chronic multisymptom illness among female Veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Med Care 2015;53(04, Suppl 1):S143–S148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mohanty AF, McAndrew LM, Helmer D, Samore MH, Gundlapalli AV. Chronic multisymptom illness among Iraq/Afghanistan-deployed US Veterans and their healthcare utilization within the Veterans health administration. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33 (09):1419–1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Magtanong GG, Spence AR, Czuzoj-Shulman N, Abenhaim HA. Maternal and neonatal outcomes among pregnant women with fibromyalgia: a population-based study of 12 million births. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2019;32(03):404–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Khashan AS, Quigley EM, McNamee R, McCarthy FP, Shanahan F, Kenny LC. Increased risk of miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy among women with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10(08):902–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zioni T, Buskila D, Aricha-Tamir B, Wiznitzer A, Sheiner E. Pregnancy outcome in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2011;24(11):1325–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brickell TA, Lippa SM, French LM, Kennedy JE, Bailie JM, Lange RT. Female service members and symptom reporting after combat and non-combat-related mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2017;34(02):300–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gerber MR, Iverson KM, Dichter ME, Klap R, Latta RE. Women veterans and intimate partner violence: current state of knowledge and future directions. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23 (04):302–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Polusny MA, Kumpula MJ, Meis LA, et al. Gender differences in the effects of deployment-related stressors and pre-deployment risk factors on the development of PTSD symptoms in National Guard Soldiers deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. J Psychiatr Res 2014; 49:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Adams RS, Nikitin RV, Wooten NR, Williams TV, Larson MJ. The association of combat exposure with postdeployment behavioral health problems among U.S. Army enlisted women returning from Afghanistan or Iraq. J Trauma Stress 2016;29(04):356–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Seelig AD, Jacobson IG, Smith B, et al. ; Millennium Cohort Study Team. Prospective evaluation of mental health and deployment experience among women in the US military. Am J Epidemiol 2012;176(02):135–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jacobson IG, Smith TC, Smith B, et al. ; Millennium Cohort Study Team. Disordered eating and weight changes after deployment: longitudinal assessment of a large US military cohort. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169(04):415–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Washington DL, Farmer MM, Mor SS, Canning M, Yano EM. Assessment of the healthcare needs and barriers to VA use experienced by women veterans: findings from the national survey of women Veterans. Med Care 2015;53(04, Suppl 1): S23–S31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nguyen S, Leardmann CA, Smith B, et al. ; Millennium Cohort Study Team. Is military deployment a risk factor for maternal depression? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013;22(01):9–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shivakumar G, Anderson EH, Surís AM. Managing posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression in women veterans during the perinatal period. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24(01): 18–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mattocks KM, Haskell SG, Krebs EE, Justice AC, Yano EM, Brandt C. Women at war: understanding how women veterans cope with combat and military sexual trauma. Soc Sci Med 2012;74(04): 537–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ashley WTJ, Constantine Brown JL, Block O. Don’t fight like a girl: veteran preferences based on combat exposure and gender. Affilia 2017;32(02):230–242 [Google Scholar]

- 93.Washington DL, Yano EM, McGuire J, Hines V, Lee M, Gelberg L. Risk factors for homelessness among women veterans. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2010;21(01):82–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hamilton AB, Poza I, Washington DL. “Homelessness and trauma go hand-in-hand”: pathways to homelessness among women veterans. Womens Health Issues 2011;21(4, Suppl):S203–S209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Webb DA, Culhane J, Metraux S, Robbins JM, Culhane D. Prevalence of episodic homelessness among adult childbearing women in Philadelphia, PA. Am J Public Health 2003;93(11):1895–1896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cutts DB, Coleman S, Black MM, et al. Homelessness during pregnancy: a unique, time-dependent risk factor of birth outcomes. Matern Child Health J 2015;19(06):1276–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kennedy S, Grewal M, Roberts EM, Steinauer J, Dehlendorf C. A qualitative study of pregnancy intention and the use of contraception among homeless women with children. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2014;25(02):757–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nyamathi A, Wenzel S, Keenan C, Leake B, Gelberg L. Associations between homeless women’s intimate relationships and their health and well-being. Res Nurs Health 1999;22(06):486–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]