Abstract

Novel therapies for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) are likely to be expensive. The cost of novel drugs (e.g., bedaquiline, delamanid) may be so prohibitively high that a traditional cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) would rate regimens containing these drugs as not cost-effective. Traditional CEA may not appropriately account for considerations of social justice and may put the most disadvantaged populations at greatest risk. Using the example of novel drug regimens for MDR-TB, we demonstrate a novel methodology (“justice-enhanced CEA”) and demonstrate how such an approach can simultaneously assess social justice impacts alongside traditional cost-effectiveness ratios. Justice-enhanced CEA, as we envision it, is performed in 3 steps: 1) systematic data collection about patients’ lived experiences, 2) use of empirical findings to inform social justice assessments, and 3) incorporation of data-informed social justice assessments into a decision analytic framework that includes traditional CEA. These components are organized around a core framework of social justice developed by Bailey and colleagues to compare impacts on disadvantage not otherwise captured by CEA. Formal social justice assessments can produce 3 composite levels – ‘Expected not to worsen…’; ‘May worsen…’; and ‘Expected to worsen clustering of disadvantage’. Levels of social justice impact would be assessed for each major type of outcome under each policy scenario compared. Social justice assessments are then overlaid side-by-side with cost-effectiveness assessments corresponding to each branch pathway on the decision tree. In conclusion we present “justice-enhanced” framework that enables the incorporation of social justice concerns into traditional cost-effectiveness analysis for evaluation of new regimens for MDR-TB.

Introduction

Economic evaluation commonly takes the form of cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), and compares costs and health effects of interventions to help direct limited healthcare resources toward those activities that provide the greatest ‘value for money’(1). CEAs generally report incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, expressed as incremental cost per incremental health outcome. For example, relative to existing standard of care for a given condition, a novel intervention might cost $1,000 (incremental cost) per additional year of life gained (incremental health outcome). Such assessments help decision-makers to determine which interventions will maximize beneficial health outcomes per dollar spent. Unfortunately, CEA may lead to policy recommendations that harm disadvantaged groups as an unintended consequence (2, 3). Take the example of novel drugs for multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB): bedaquiline(4) and delamanid(5). These drugs are more expensive than ones in current use; it may be less costly (and equally effective) to maintain standard MDR regimens versus implementing novel MDR regimens. Standard regimens, which typically require more hospitalizations, and/or longer treatment durations than novel regimens, may expose patients to significantly higher risks of treatment-induced disadvantages like stigma. Finding ways to assess impacts on social disadvantage such as stigma alongside the traditional CEA is critical to enabling clinicians, policymakers, academic allies, and funders to develop MDR-TB treatment policies that are more just and thereby more responsive to needs of the populations they serve.

Social justice is an ethical consideration prominent in the school of political philosophy inspired by Rawls’s work on justice (6, 7) and Sen’s work on inequality, (8, 9) and carried forward by theorists such as Daniels, Nussbaum, Powers and Faden (2, 10, 11). It calls for fairness and equity in the distribution of societal advantages and disadvantages, including the impacts of health policy choices, and a commitment to social justice is central to public health (12) (13). Stigma has been defined as” a social process, experienced or anticipated, characterized by exclusion, rejection, blame or devaluation, that results from experience, perception or reasonable anticipation of an adverse social judgement about a person or group”(14). TB has long been a highly stigmatized disease and accounting for stigma within social justice assessments of TB interventions should be considered a key element in moving cost-effectiveness analyses forward.

Policy choices involving social justice may present trade-offs between maximizing net benefit and combating severe disadvantage (2, 12, 15, 16). To conduct fully informed policy deliberations, decision makers should be able to represent such trade-offs explicitly, but traditional CEA does not equip them to do so (2). We use the MDR-TB treatment example to introduce the concept of a new methodology that we term justice-enhanced CEA (JE-CEA). We show how JE-CEA can assess impacts on social justice alongside traditional cost-effectiveness ratios, and we suggest how it may support better-informed policy decisions (Box 1).

Box 1. Current limitations in traditional CEA and examples of ways Justice-enhanced CEA may bolster traditional CEA.

| Current gaps in traditional CEA | Advantages of JE-CEA approach |

|---|---|

|

|

MDR-TB: standard vs. novel treatment regimens

Tuberculosis (TB) disproportionately affects populations that are already disadvantaged(17). It may also exacerbate pre-existing disadvantage not only through the physical, social, and financial hardships of the disease itself, but also through lengthy, burdensome treatment that may exacerbate disadvantages of stigma, shame, social isolation, loss of agency and family strain (18, 19). With lower cure rates and higher fatality rates, MDR-TB carries even greater stigma and fear than drug sensitive TB; alongside longer, more burdensome treatment (20, 21).

Novel MDR-TB treatment regimens are still under investigation, but early studies suggest the possibility of similar or higher cure rates with fewer side effects(5, 22, 23). Bedaquiline and delamanid have both shown early evidence of efficacy, both are taken orally, potentially eliminating the current need for painful daily intramuscular injections at healthcare facilities (24). These novel agents come at exceptionally high prices; for example, current prices for delamanid in Europe exceed $28,000 for a 6-month course, or $150 daily (25). Because of this price differential, traditional CEA might not deem regimens using these high-priced novel agents to be cost-effective, even though they could transform therapy for patients from a two-year course – including eight months of frequently crippling daily injections in a hospital or remote facility – into a nine-month, fully oral regimen (26, 27). From the standpoint of the commitment to social justice that is central to public health (13, 28), CEA’s inability to compare explicitly the impact of different policies on the distribution of disadvantage, alongside incremental cost-effectiveness, is ethically sub-optimal.

The social justice framework

A formal methodology to account for impacts on disadvantage in the context of CEA can be constructed using a core framework of social justice recently synthesized by Bailey and colleagues (19). This approach proceeded by locating areas of agreement among a family of theories of social justice that deploy “multidimensional metrics of human well-being”, where each theory identifies certain dimensions of well-being that people generally have reason to value as “basic determinants of the character and quality of human life” (2, 9–11, 15, 28–32). Bailey and colleagues sought to identify the points of “convergence or overlap” so that the resulting framework would be a basis for ethical analysis in the context of public health policymaking (19: p. 631).

Three core dimensions of human well-being were identified, namely: (1) agency – the ability to lead one’s life and engage in activities one finds meaningful; (2) respect – the recognition of one’s equal moral value, worth, and dignity as a person; and (3) association – the ability to engage in a full range of intimate, familial, friendly, community, economic, and civic relationships with others (28). A 4th point of convergence to complete the core framework, Bailey and colleagues identified “a shared principle of prioritization” as follows (19: p. 632):

“….it is a priority and duty of justice to avert and alleviate clusters of disadvantage in multiple dimensions of well-being. As Powers and Faden argue, justice requires that priority be given to addressing systematic disadvantages that cut across multiple core dimensions of well-being (3). Wolff and de-Shalit argue for a duty to prioritize social institutions, programs, and policies that ‘decluster disadvantage,’ breaking up vicious cycles through which disadvantages in some dimensions of well-being coexist with and reinforce disadvantages in other dimensions (8). Venkatapuram has also endorsed this norm(29).”

Within the context of TB, stigma can impact on each of these three dimensions of well-being. For example, TB stigma may impact agency or the ability to lead one’s life and engage in activities one finds meaningful through enacted or experienced stigma (also known as discrimination), structural stigma such as policies or laws may also impact one’s agency(33, 34). Anticipated or perceived stigma may result from the belief in some communities that one is devalued or ‘less than’ others once they have been diagnosed with tuberculosis, this type of stigma impacts on the respect dimension and can lead to delayed diagnosis and poor treatment adherence(35). Secondary or courtesy stigma is present when family, friends and colleagues may expect a negative attitude because of their link with TB, this can lead to important impacts on patients’ dimension of association and can limit their regular activities and support opportunities(36).

Specific policy choices can be compared in terms of their expected impact on the clustering of disadvantage across core dimensions of well-being (15). A just decision process for questions of health policy ought at least to avoid exacerbating the clustering of disadvantage in affected populations (2). The failure to anticipate and avert such policy outcomes would undermine social justice by worsening the plight of people in society who were already relatively badly off prior to the enactment of the policy, and who may have come into the line of fire of adverse policy impacts through the very pre-existing circumstances by which they were already disadvantaged. For example, TB stigma may be worsened by increased number or duration of visits to health care facilities or prolonged hospitalization. Novel treatment regimens may reduce the number of visits and or duration leading to a reduction in experienced or anticipated stigma. These impacts should be accounted for in cost-effectiveness analysis, else these important social justice impacts may be overlooked.

Justice-Enhanced CEA

We propose, a systematic, data-informed methodology called justice-enhanced CEA (JE-CEA). For any given policy question to which CEA is applicable, JE-CEA is a social justice assessment that enables decision makers to explicitly consider expected impacts on the clustering of disadvantage. Using three impact levels, the social justice assessment for a given scenario under analysis could be either ‘Expected not to worsen…’, ‘May worsen…’, or ‘Expected to worsen…”, as color-coded in Figure 1. We use the language of ‘worsening’ here because, as noted above, a just decision process for questions of health policy ought at least to avoid exacerbating the clustering of disadvantage in affected populations (2). In the context of scaling up novel MDR-TB regimens, our assumption is that the successful treatment of the disease constitutes the main vehicle to alleviate disease-imposed disadvantage. JE-CEA is designed to support the comparison of approaches in terms of their unintended and unwelcome propensities to exacerbate clustering of disadvantage across core dimensions of well-being – agency, association, and respect.

Figure 1. Impact on social justice to be overlaid over traditional CEA decision tree.

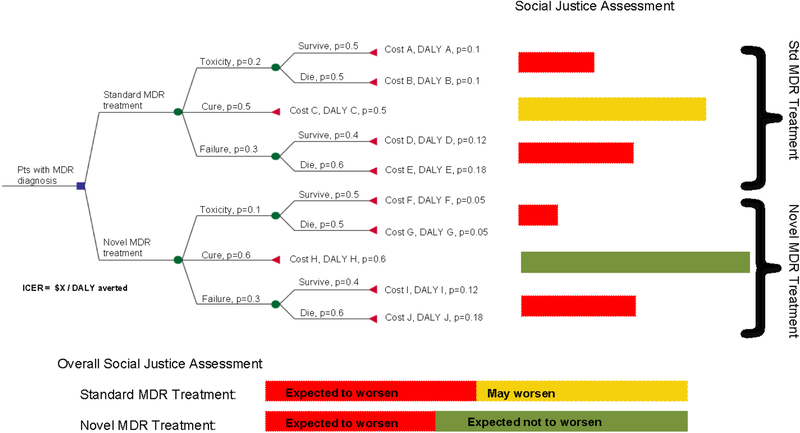

These assessments are compiled using empirical findings tracking the occurrence, magnitude, and breadth of cross-cutting impacts on the 3 core dimensions of well-being. For instance, empirical findings may indicate that even patients who experience cure on MDR-TB treatment may suffer marital strife or public ridicule as a result of prolonged hospitalization. An MDR-TB cure requiring hospitalization might accordingly be associated with adverse impacts of moderate magnitude across a breadth of 2 core dimensions of well-being: association (social isolation) and respect (stigma). Such levels of social justice impact could be assessed for each major type of outcome under treatment regimens to be compared. As a simplified example, we show hypothetical assessments in Figure 2 with possible outcomes of cure, toxicity, and failure. Each outcome could have a probability and an expected impact on social justice informed by empirical data, for both standard and novel MDR-TB regimens.

Figure 2. Hypothetical, simplified example of the proposed methodology incorporating social justice.

In this simplified decision analysis tree, we present a representation of how social justice assessments may be overlaid with the decision analysis framework corresponding to particular branches in the model. The colors of the bars represent the expected impact on social justice experienced on average across each branch pathway, while the length of the bars correspond to the proportion of the cohort experiencing that particular social justice impact. For the overall social justice assessment, assessments are concatenated across each intervention arm. (pts: patients; p: probability; DALY: disability adjusted life years; MDR: multi-drug resistant tuberculosis; ICER: incremental cost-effectiveness ratio)

Social justice assessments can be presented in parallel to a decision tree as is commonly used for CEA (Figure 2). Each social justice assessment will have two dimensions: 1) proportion of patient population exposed to each outcome (length of bar shown in Figure 2), and 2) level of impact on clustering of disadvantage under that outcome (color of bar). An overall social justice assessment can be compiled by presenting summary bars for each alternative. In the hypothetical example of Figure 2, the summary bars indicate that, relative to the standard regimen, the novel regimen is favored on both dimensions of the social justice assessment (proportion exposed and level of impact).

Data to inform JE-CEA: MDR-TB patients’ lived experiences

To perform JE-CEA comparing MDR-TB treatment regimens in a given setting, empirical estimates of impact on core dimensions of well-being will be required. A qualitative evaluation is needed to determine whether, in what ways, and to what extent each regimen might worsen the clustering of disadvantage experienced by patients. For example, a meta-analysis of prior qualitative research on TB patients’ experience indicates that patient-centered barriers to TB treatment adherence include lack of community, family, or household support(28). Techniques such as in-depth interviews with MDR-TB patients and their healthcare providers can be used to explore social isolation as well as other ways in which MDR-TB treatment may compromise agency, respect, and association for patients. Interview findings can be used to compile formal social justice assessments, which are then incorporated into the JE-CEA decision analysis. Future work could build on qualitative findings to further refine decision analysis by developing tools to better quantify factors most likely to exacerbate disadvantage.

Synthesis

Decision makers should be empowered to assess both value for money and impact on disadvantage at once, making explicit any trade-offs between them. When they are concordant, the case for making a certain decision is bolstered; when they are discordant, decision-makers should evaluate the discrepancy. In cases like the example discussed above – in which the hospitalization required by standard MDR-TB treatment is associated with experiences of stigma and social isolation, which could be averted by a novel (but high-cost) regimen requiring no hospitalization – the CEA component of JE-CEA, (ie: the ICER), might favor the standard regimen, while the justice-enhanced component (ie: social justice assessment) favors the novel regimen. JE-CEA would present decision makers not only with this discrepancy, but also with the extent of relevant impacts on each side. In this type of case, JE-CEA might serve to provide the additional justification needed for policymakers to implement costly regimens to improve the plight of MDR-TB patients, and ultimately for civil society to press for reductions in the price of novel MDR-TB regimens.

Strengths & limitations of the JE-CEA approach

If successfully implemented and replicated, JE-CEA could fill important gaps in the current approach to economic evaluation (Box 1). These include: introducing social justice language into economic evaluation; encouraging the awareness and inclusion of social justice impacts when making health-related decisions; highlighting the need for the collection and analysis of empirical data to demonstrate how treatment regimens can exacerbate disadvantage; and encouraging decision makers to incorporate formal assessments of social justice in key policy and resource allocation decisions. To achieve these gains, additional resources and expertise would be required to compile formal social justice assessments across different settings. It remains unclear how far such assessments may be generalizable (though the same could be said about the economic considerations of CEA). It is important to note that social justice may not be the only element lacking in CEA, and evaluations should perhaps also include assessments of fairness, equity or age preference, just to name a few. The methodology proposed here is but a first step toward including elements like social justice in a formal assessment of CEA. While transmission is a critical issue for MDR-TB control, JE-CEA at this stage relies on a decision analysis model and does not explicitly account for transmission. Future expansion of the methodology should involve transmission models.

JE-CEA methodology is currently under conceptual development. Its full elucidation remains to be borne out through empirical research and discussions with clinicians and policy makers. Further work is intended to refine this concept by including empirical estimates/observations of perceptions of social justice impacts, as well as quantitative efforts to appropriately balance cost-effectiveness and social justice considerations. Moreover, while the core framework of social justice employed in JE-CEA is derived from theories in political philosophy, it will also be important to consider social-science-based frameworks for addressing issues of social justice and health, such as de-stigmatization (37, 38) The adoption of JE-CEA will require the engagement and education of key stakeholders as well as thoughtful dissemination across various settings. Being able to see social justice assessments alongside traditional CEA outputs still leaves policymakers with difficult decisions, particularly in cases of discordance. Like traditional CEA, however, JE-CEA is designed not to replace the decision-making process but to provide a more complete picture that decision makers can use to organize and inform their deliberations. Importantly, we do not suggest that JE-CEA is the only way to incorporate social justice assessments into economic evaluation; rather, the development of JE-CEA may stimulate improved approaches that could further promote the inclusion of formal social justice assessments into traditional CEA, policy development and key decision-making processes.

Conclusion

Current prevailing methods for economic evaluation do not fully address considerations of social justice. As a result, assessments of interventions such as novel regimens for MDR-TB may overlook important potential benefits in reducing clusters of disadvantage, missing opportunities to alleviate patient burden. International human rights law principles call for a focus on vulnerable and marginalized groups, (39) yet traditional CEA does not address this need and may overlook this important principle. Here we propose justice-enhanced CEA as an alternative approach. Formal assessments of social justice can and should be undertaken in conjunction with CEA to provide more complete information to decision-makers. Otherwise, initially costly interventions (including novel regimens for MDR-TB) may never be scaled up, with the result that clinicians do not have access to certain (more expensive) treatments, clustering of disadvantage is worsened among already badly-off populations, and sufficient pressure is never applied for the economics of those interventions to change. Incorporating social justice assessments into CEA can lead to more ethically responsible decision making, ultimately creating a healthier and more just society.

Key Messages.

Current prevailing methods for economic evaluation in medicine do not fully address considerations of social justice.

Decision makers should be empowered to assess both value for money and impact on disadvantage at once, making explicit any trade-offs between them.

Incorporating social justice assessments into CEA can lead to more ethically responsible decision making, ultimately creating a healthier and more just society.

Acknowledgements:

AZ, MWM, DD and HT conceived this work. The paper was drafted and critically reviewed by AZ, DD, MWM, AVD and HT. All authors had authority over manuscript preparation and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. No authors have any conflicts to declare. This work was funded by a grant awarded to MWM by the US National Institutes of Health (1R56AI114458–01). The funding organization had no involvement in the design of the study, or the decision to publish the manuscript. The authors are grateful to two anonymous journal reviewers for valuable comments that enabled us to improve the manuscript.

Financial support for this study was provided entirely by a grant awarded to MWM by the US National Institutes of Health (1R56AI114458–01). The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Drummond M, Sculpher M, Torrance G, O’Brien B, Stoddart G. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes, 3rd Edition 3rd ed. New York, USA: Oxford University Press Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powers M, Faden R. Social Justice: the Moral Foundations of Public Health and Health Policy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brock DW, Daniels N, Neumann PJ, Siegel JE. Ethical and Distributive Considerations In: Neumann PJ, Sanders GD, Russell LB, Siegel JE, Ganiats TG, editors. Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. The use of bedaquiline in the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: interim policy guidance. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lessells RJ. Delaminid for multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. Thorax. 2013;68(8):730. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rawls J A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rawls J, Kelly E. Justice as Fairness: A Restatement. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sen A Inequality Reexamined. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sen A Developmeny as Freedom. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniels N Just Health: Meeting Health Needs Fairly. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nussbaum MC. Creating Capabilties: The Human Development Approach. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 7th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faden R, Shebaya S. Public Health Ethics. In: Zalta EN, editor. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss MG, Ramakrishna J, Somma D. Health-related stigma: rethinking concepts and interventions. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(3):277–87. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolff J, DeShalit A. Disadvantage. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brock DW. Ethical issues in the use of cost effectiveness analysis for the prioritization of health care resources In: Anand S, Peter F, Sen A, editors. Public Health, Ethics and Equity. UK: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grange J, Story A, Zumla A. Tuberculosis in disadvantaged groups. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2001;7(3):160–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hargreaves JR, Boccia D, Evans CA, Adato M, Petticrew M, Porter JD. The social determinants of tuberculosis: from evidence to action. American journal of public health. 2011;101(4):654–62. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.199505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lonnroth K, Jaramillo E, Williams BG, Dye C, Raviglione M Drivers of tuberculosis epidemics: the role of risk factors and social determinants. Social science & medicine. 2009;68(12):2240–6. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin SS, Pasechnikov AD, Gelmanova IY, Peremitin GG, Strelis AK, Mishustin S, et al. Adverse reactions among patients being treated for MDR-TB in Tomsk, Russia. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2007;11(12):1314–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO. Multidrug and Extensively Drug-Resistant TB (M/XDR-TB): 2010 Global Report on Surveillance and Response. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diacon AH, Dawson R, von Groote-Bidlingmaier F, Symons G, Venter A, Donald PR, et al. 14-day bactericidal activity of PA-824, bedaquiline, pyrazinamide, and moxifloxacin combinations: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9846):986–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diacon AH, Pym A, Grobusch M, Patientia R, Rustomjee R, Page-Shipp L, et al. The diarylquinoline TMC207 for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360(23):2397–405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.TBAlliance. Portfolio: Clinical Development NY, USA [cited 2014 Dec. 18]. Available from: http://www.tballiance.org/portfolio/.

- 25.Lessem E An Activist’s Guide to Delaminid (Deltyba). Treatment Action Group (TAG), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aung KJ, Van Deun A, Declercq E, Sarker MR, Das PK, Hossain MA, et al. Successful ‘9-month Bangladesh regimen’ for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among over 500 consecutive patients. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2014;18(10):1180–7. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vassall A Cost-effectiveness of introducing Bedaquiline in MDR-TB regimens - An exploratory analysis. World Health Organisation (WHO), 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bailey TC, Merritt MW, Tediosi F. Investing in Justice: Ethics, Evidence and the Eradication Investment Cases for Lymphatic Filariasis and Onchocerciasis. American journal of public health. (In Press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venkatapuram S Health Justice: An argument from the Capabilities Approach. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alkire S Valuing Freedoms: Sen’s Capability Approach and Poverty Reduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crocker DA. Ethics of Global Development: Agency, Capability, and Deliberative Democracy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruger JP. Health and Social Justice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coreil J, Mayard G, Simpson KM, Lauzardo M, Zhu Y, Weiss M. Structural forces and the production of TB-related stigma among Haitians in two contexts. Social science & medicine. 2010;71(8):1409–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baral SC, Karki DK, Newell JN. Causes of stigma and discrimination associated with tuberculosis in Nepal: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:211. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Somma D, Thomas BE, Karim F, Kemp J, Arias N, Auer C, et al. Gender and socio-cultural determinants of TB-related stigma in Bangladesh, India, Malawi and Colombia. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2008;12(7):856–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Craig GM, Daftary A, Engel N, O’Driscoll S, Ioannaki A. Tuberculosis stigma as a social determinant of health: a systematic mapping review of research in low incidence countries. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;56:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berezin M, Lamont M. Mutuality, mobilization, and messaging for health promotion: Toward collective cultural change. Social science & medicine. 2016;165:201–5. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clair M, Daniel C, Lamont M. Destigmatization and health: Cultural constructions and the long-term reduction of stigma. Social science & medicine. 2016;165:223–32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.CESCR U. The Nature of States Parties’ Obligation. UN CESCR, 1990. [Google Scholar]