Abstract

Objectives:

Predictors of success among emerging adults (EA; ages 18–25) within behavioral weight loss (BWL) trials are largely unknown. We examined whether early program engagement predicted overall engagement and weight loss in EA.

Methods:

Data were pooled from 2 randomized controlled pilot trials in EA. Participants (N = 99, 80% female, BMI = 33.7±5.1 kg/m2) received a 3-month BWL intervention. Weight was objectively assessed at 0 and 3 months; engagement was tracked weekly; retention was assessed at 3 months.

Results:

Greater engagement during the initial 4 weeks of treatment predicted greater weight loss (p = .001). Compared to those who did not engage in all 4 initial weeks, participants meeting this threshold experienced greater overall engagement (9.6 vs. 4.2 weeks, p < .001), weight losses (intent-to-treat = −3.8% vs. −1.3%, p = .004), and retention (78% vs. 53%, p = .012).

Conclusions:

Early engagement in BWL is associated with better outcomes among EA. Monitoring engagement in real-time during the initial 4 weeks of treatment may be necessary to effectively intervene. Early engagement did not vary by sex or race; future work should identify characteristics associated with poor early engagement.

Keywords: emerging adults, young adults, behavioral weight loss, engagement

Though obesity is a major public health challenge across the lifespan, emerging adulthood—typically ranging from ages 18 to 25—represents a unique developmental period wherein individuals are at especially high risk for weight-related concerns. In fact, weight gain is greater during emerging adulthood than any other developmental period1 with an estimated more than 40% of 18–25 year olds meeting criteria for overweight or obesity.2 Further, the weight gain and obesity during these years is associated with increased cardiometabolic risks.3–6 Thus, the transition from adolescence to early adulthood represents a crucial time to intervene for disease prevention and health promotion.

Multiple factors appear to contribute to weight gain and obesity during emerging adulthood including reduced exercise, unhealthy eating patterns, and poor sleep hygiene in addition to frequent transitions in living situations, work, school, and relationships.7 These same challenges may also contribute to the poor outcomes seen among emerging adults enrolled in standard adult behavioral weight loss (BWL) programs.8 Given the unique issues that emerging adults face, it is essential that BWL interventions for this group are tailored to help 18- to 25-year-olds navigate these obstacles. With an increased awareness of the need for targeted interventions for this population,8,9 research on effective ways to intervene to prevent weight gain and promote weight loss specifically for emerging adults is growing. Recent pilot trials of BWL programs designed for emerging adults have demonstrated marked improvements relative to their performance in adult programs, but mean weight losses are modest and variability in treatment response remains a considerable challenge.10,11 Findings from these initial studies highlight the need to identify factors that may be predictive of overall success to inform future efforts to intervene with this high-risk population.

Given that similar variability is also seen in standard adult BWL trials,12–14 turning to this body of literature may help to inform investigations of this phenomenon among emerging adults. Early treatment response has been identified as a predictor of overall and long-term weight loss, suggesting that the first few months of treatment are a crucial time to engage participants. A study looking at success in a BWL program for older adults (ages 45–76) with type 2 diabetes and a BMI ≥ 25kg/m2, found that weight loss during the first 2 months of the intervention was associated with 1-year weight loss.15 Further, these authors found that 1- and 2-month initial weight loss was associated with 8-year weight loss.16 Notably, there was a significant difference in adherence in month 2 with those participants with poorer weight loss at month 2 attending fewer meetings, consuming fewer meal replacements, and engaging in less physical activity compared to those participants with highest initial weight loss.16

Among emerging and young adults in weight management trials, engagement is a notorious challenge.17 Several studies targeting this population have documented early disengagement, with one study reporting decline in online engagement as early as 4 weeks into the trial.18 Another study with young adults found that the proportion of highly engaged participants declined quickly during the first 3 months and overall engagement steadily declined over 24 months.19 Given how common disengagement is, it is important to understand how engagement—or lack thereof—may impact overall weight loss outcomes among emerging adults specifically. While the relationship between early engagement and weight loss outcomes has been established in the adult BWL literature, this relationship has not been examined among emerging adults. This gap is notable, as it is not always the case that findings in the adult literature are directly translatable to emerging adults. For instance, emerging adults respond poorly to traditional behavioral weight loss programs that have demonstrated great success among adults as a whole;8 further, while depressive symptoms and alcohol use have been shown to decrease over the course of BWL programs for adults,20–22 data demonstrate both depressive symptoms and alcohol use remain unchanged throughout BWL programs for emerging and young adults.23,24

In sum, while early treatment response and adherence appear to be important early predictors of overall weight loss success for older adults,15,16 little is known about factors that might predict outcomes for emerging adults. To that end, this study examined whether early program engagement predicted better overall engagement, retention, and weight loss for emerging adults within a behavioral weight loss program designed specifically for this population.

METHODS

Participants & Procedures

The current study is a secondary data analysis using a pooled dataset from 2 randomized controlled pilot trials (NCT01889082; NCT01899625) both of which involved 3-month behavioral weight loss (BWL) programs adapted specifically for emerging adults based on our previous formative work.25 A detailed description of tailoring can be found in our pilot trial outcomes paper;10 briefly, we expanded traditional BWL content to provide an increased emphasis on goal-setting and behavior change surrounding high-risk behaviors specific to the transition into adulthood (eg, alcohol, sweetened beverages). Program content also addresses other key areas of interest for this population that emerged based on our formative work (eg, time and stress management, motivation). In addition to content changes, we also shortened the core treatment program to 3 months’ duration (compared with typical 6 to 18 months in adult programs) and delivered the intervention using a combination of in-person sessions and the Internet in order to be responsive to emerging adults’ reported time and schedule demands, while still providing some desired in person contact.

Participants were recruited using digital and print advertisements, radio spots, email blasts, listservs, and flyers. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for both trials were the same. Inclusion criteria included: 1) age 18–25 years; 2) body mass index (BMI) of 25–45 kg/m2; 3) regular Internet access; 4) English speaking; and 5) willingness to be randomized to any of the arms. Exclusion criteria included 1) uncontrolled medical condition that would pose a safety risk with weight loss or unsupervised exercise (eg, uncontrolled hypertension); 2) current or planned use of weight loss medications or participation in another weight loss program; 3) reported heart condition, chest pain, or loss of consciousness on the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q); 4) psychiatric hospitalization in the last 12 months; 5) pregnancy, lactation, or plans to become pregnant during the study period; 6) weight loss of greater than 5% within the previous 6 months; 7) reported history of or current eating disorder. Individuals who met all inclusion/exclusion criteria and were interested in participating provided informed consent following an in-person informational meeting. Participants who reported medical conditions that could interfere with their ability to safely complete the intervention were required to obtain written MD permission prior to beginning treatment. Both of the trials involved weekly intervention contact for 3 months, with a combination of in person and technology mediated delivery (ie, website, reporting platform, weekly e-coaching). All study procedures were approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Demographics.

At baseline, participants reported sex, age, race, and ethnicity.

Height, weight, and BMI.

Height was measured at baseline only to the nearest millimeter using a wall-mounted stadiometer and a standard protocol. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.01 kg in light clothes without shoes using a calibrated digital scale at 0 and 3 months. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms/height in square meters.

Engagement in treatment.

Engagement was tracked weekly throughout the 3-month programs. Engagement for this study was operationalized as attendance at an initial in person session and at least weekly weight reporting during the technology mediated phase, which was the primary metric for engagement and drove e-coaching feedback.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Release 25.0.0 (IBM Corp.©, 2017, Armonk, NY, www.ibm.com). Descriptive analyses were conducted on baseline demographic characteristics of participants. Weekly engagement was binary-coded based on whether participants attended a session visit (for in-person contacts) and as reporting weight at least once during technology-mediated weeks. Early engagement was examined as a continuous variable (total number of weeks engaged) for analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a rank-ordered variable for correlational analysis using Spearman’s rho. In subsequent analyses, engagement was also dichotomized into participants who engaged in all 4 initial weeks (“high early engagers”) compared to those who did not meet this threshold (“low early engagers”) for chi-square analyses; the threshold of 4 weeks was selected both based on the distribution of these data and extant reports from adult literature.15

Initial analyses (using either ANOVA or chi-square analysis depending on the characteristics of the dependent variable) found no significant (p > .05) results for overall study or treatment arm differences with respect to demographic variables, weight change, and whether a participant was a high early engager, providing statistical support for pooling the 2 study data sets. ANOVA was used to examine percent weight loss for completers only and separately under intent-to-treat analyses with baseline observation carried forward (ITT). When ITT was employed we report robust ANOVA statistics (Welch Test), and used the Game-Howell post-hoc test to distinguish significant differences with respect to weeks of early engagement.

RESULTS

Participants (N = 99) were 80% female and 52.5% non-Hispanic White, 29.3% non-Hispanic Black / African American, 8.1% Hispanic / Latinx, 4% Asian, 4% of participants identified as multiracial, and 2% declined to report on their race. Average age was 22.1 years (SD = 2.0) with an average baseline BMI of 33.7 kg/m2 (SD = 5.1), and the majority were never married (73.7%). There were no differences in early engagement by sex (p = .61), race (p = .10) or ethnicity (p = .60).

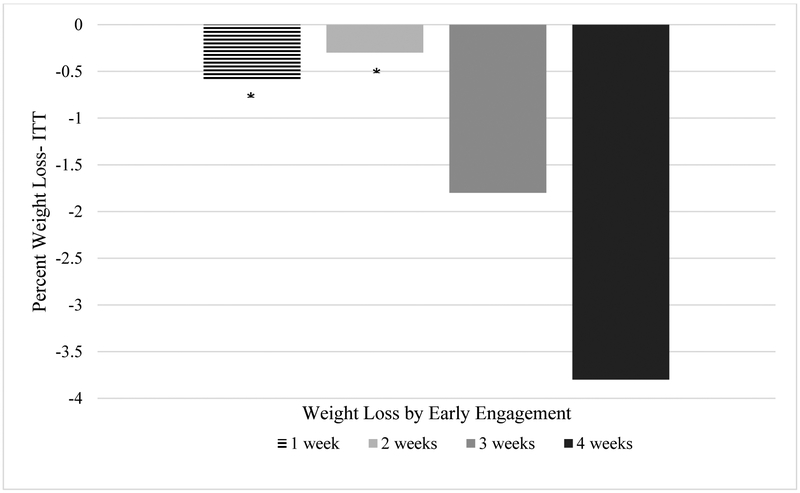

Overall, greater engagement during the initial 4 weeks of treatment was associated with greater percent weight change at 3 months (rho = −.32, p = .001). There was a dose response pattern observed (p < .001), such that weight loss increased as weeks of engagement increased during the initial weeks of treatment [−0.6% for 1 week and −3.8% for 4 weeks, with 4 weeks significantly greater than both 1 and 2 weeks (see Figure 1)]. A total of 70% of participants were high early engagers, participating in all 4 initial weeks of treatment by attending the initial in-person sessions and reporting weight thereafter. Compared to low early engagers, high early engagers demonstrated a greater overall rate of engagement throughout the 3-month program (9.6/12 weeks vs. 4.2/12 weeks, p < .001). In addition, high early engagers were significantly more likely to complete their post-treatment assessment (78% retention vs. 53%, p = .012). With respect to weight loss (Figure 2), high early engagers fared better in both intent-to-treat (−3.8% vs. −1.3%, p = .004) and completers-only analyses (−4.8% vs. −2.4%, p = .045).

Figure 1.

Dose Response Pattern in 3-month Weight Loss (ITT) Based on Early Engagement

*significant difference in weight change (p < .05) compared to 4 weeks

Figure 2.

Weight Losses at 3-months for High Early Engagers vs Low Early Engagers

DISCUSSION

Given the high rates of overweight and obesity in emerging adults combined with the tremendous variability in treatment response in the few behavioral weight loss interventions specifically targeting this age group, identification of individual-level factors that are predictive of weight loss success is essential. Results from this study suggest that those emerging adults who were high early engagers (ie, attended initial in person session and reported weight during the initial 4 weeks of a BWL treatment) had greater overall engagement in treatment, greater weight loss, and better retention compared to low early engagers. Further, results revealed a dose response pattern such that participants who engaged in 4 weeks as opposed to 1–2 weeks experienced significantly greater weight loss, with weight losses at an intermediate level for those who engaged 3 weeks. Taken together, these findings underscore the initial 4 weeks of treatment as a critical window for engagement to promote weight loss in this high-risk population—and perhaps more importantly, these results highlight the importance of consistent engagement during this window. Seeking to identify baseline variables that might be used to predict poor early treatment response would be of interest in future work and could inform treatment matching efforts. Of note, in the current sample, early engagement did not differ based on demographic characteristics, including sex, race or ethnicity—examining other contextual, psychological or behavioral characteristics and their association with early engagement could be useful in future work.

While identification of engagement as an early predictor of weight loss is important, more research is also needed on how to promote re-engagement, especially for those emerging adults who may have disengaged early in the lifestyle intervention. Developing specific and targeted strategies that individualize the content and type of intervention contact based on engagement during the first month may be effective. For example, a stepped care model of intervention could be employed wherein all emerging adults receive a fully automated technology platform to start, and based on early engagement and / or treatment response, individuals can be stepped into more intensive contact or rescue approaches. In adult behavioral weight loss interventions, one study found that delivering a more intensive invention to participants failing to meet specific weight loss goals at 6 weeks (but not 12) was successful.26,27 Another adult weight loss study found that the standard behavioral weight loss model produced similar 18-month weight losses compared to a “stepped care” model with modifiable intensity.12 Within Internet-based programs specifically, recent data from adults suggest that offering additional interventionist support via a single in-person contact and 2 phone calls greatly improved weight loss outcomes for early non-responders.28 More research is needed to determine what rescue approaches will be most effective among emerging adults specifically.

While determining how to best promote re-engagement among emerging adults remains a critical direction for future research, results from the current study provide insight regarding when to intervene in order to promote re-engagement. Typical BWL contact occurs on a weekly basis; however, the dose-response pattern found here indicates that waiting until the following week to discuss a lapse in self-weighing increases the odds for poorer overall weight loss outcomes. Sending automated SMS text reminders to step on the scale to those participants who have not weighed themselves in 3 days could serve to prevent a lapse in consistent self-weighing—thus promoting continuous engagement with little added effort or cost. Future work could also focus on the development of Just-in-Time Adaptive interventions to promote continued engagement and adherence during high-risk times in emerging adults’ daily lives. Although this study highlights the importance of early engagement for weight loss, it is limited by the assessment follow-up length of 3 months. Future work should investigate whether this threshold predicts longer-term weight loss and other desirable outcomes. Additionally, identifying individual characteristics, such as initial level of motivation, level of stress or depression, or life events, that are associated with poorer early engagement might help tailor interventions to improve outcomes. Given data were pooled across 2 pilot trials, the same assessment measures were not available for all participants to examine these variables in the current study. Limitations withstanding, this study is the first to demonstrate that among emerging adults, early engagement in behavioral weight loss trials is associated with more favorable outcomes in terms of overall engagement, retention and weight loss. Further, the sample was diverse with respect to race and ethnicity. In sum, results suggest that consistent early engagement is crucial to weight loss success among emerging adults; and furthermore, data indicate that weight loss outcomes might be improved by carefully monitoring engagement within the first 4 weeks of treatment in order to detect lapses and intervene in order to provide additional support.

Acknowledgements

These findings were presented in part at the 2017 annual meeting of The Obesity Society. We would like to acknowledge Megan Henderson for her coordination of these trials and her technical assistance with the present manuscript. We are grateful to the participants in the SPARK RVA and Live Well RVA trials, without whom this work would not be possible. And finally, we acknowledge funding for this work (NIDDK #K23DK083440 and #R03DK095959). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of NIDDK.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Approval Statement

All study procedures were approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board (#HM14613 & #HM14857).

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors of this article declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Jessica Gokee LaRose, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Department of Health Behavior and Policy, Richmond, VA.

Joseph L. Fava, The Miriam Hospital Weight Control and Diabetes Research Center, Providence, RI.

Autumn Lanoye, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Department of Health Behavior and Policy, Richmond, VA.

Laura Caccavale, Children’s Hospital of Richmond at Virginia Commonwealth University, Healthy Lifestyles Center, Richmond, VA.

References

- 1.Williamson DF, Kahn HS, Remington PL, Anda RF. The 10-year incidence of overweight and major weight gain in US adults. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(3):665–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity. Data, trends, and maps (on-line). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/data-trends-maps/index.html. Accessed February 8, 2019.

- 3.Merten MJ. Weight status continuity and change from adolescence to young adulthood: examining disease and health risk conditions. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18(7):1423–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carnethon MR, Loria CM, Hill JO, et al. Risk factors for the metabolic syndrome: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, 1985–2001. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(11):2707–2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bild DE, Sholinsky P, Smith DE, et al. Correlates and predictors of weight loss in young adults: the CARDIA study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20(1):47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dutton GR, Kim Y, Jacobs DR Jr., et al. 25-year weight gain in a racially balanced sample of U.S. adults: the CARDIA study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(9):1962–1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanoye A, Brown KL, LaRose JG. The transition into young adulthood: a critical period for weight control. Curr Diab Rep. 2017;17(11):114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gokee-LaRose J, Gorin AA, Raynor HA, et al. Are standard behavioral weight loss programs effective for young adults? Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33(12):1374–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loria CM, Signore C, Arteaga SS. The need for targeted weight-control approaches in young women and men. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(2):233–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaRose JG, Tate DF, Lanoye A, et al. Adapting evidence-based behavioral weight loss programs for emerging adults: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Health Psychol. 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Napolitano MA, Hayes S, Bennett GG, et al. Using Facebook and text messaging to deliver a weight loss program to college students. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jakicic JM, Tate DF, Lang W, et al. Effect of a stepped-care intervention approach on weight loss in adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2012;307:2617–2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lillis J, Niemeier HM, Thomas JG, et al. A randomized trial of an acceptance-based behavioral intervention for weight loss in people with high internal disinhibition. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24:2509–2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke LE, Ewing LJ, Ye L, et al. The SELF trial: a self-efficacy-based behavioral intervention trial for weight loss maintenance. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23:2175–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unick JL, Hogan PE, Neiberg RH, et al. Evaluation of early weight loss thresholds for identifying nonresponders to an intensive lifestyle intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22(7):1608–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unick JL, Neiberg RH, Hogan PE, et al. Weight change in the first 2 months of a lifestyle intervention predicts weight changes 8 years later. Obesity. 2015;23(7):1353–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lytle LA, Laska MN, Linde JA, et al. Weight-gain reduction among 2-year college students: the CHOICES RCT. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(2):183–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laska MN, Sevcik SM, Moe SG, et al. A 2-year young adult obesity prevention trial in the U.S.: process evaluation results. Health Promot Int. 2016; 31(4):793–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta A, Calfas KJ, Marshall SJ, et al. Clinical trial management of participant recruitment, enrollment, engagement, and retention in the SMART study using a Marketing and Information Technology (MARKIT) model. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;42:185–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naparstek J, Wing RR, Xu X, et al. Internet-delivered obesity treatment improves symptoms of and risk for depression. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(4):671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faulconbridge LF, Wadden T, Rubin RR, et al. One-year changes in symptoms of depression and weight in overweight/obese individuals with type 2 diabetes in the Look AHEAD study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(4):783–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kase CA, Piers AD, Schaumberg K, et al. The relationship of alcohol use to weight loss in the context of behavioral weight loss treatment. Appetite. 2016;99:105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorin AA, LaRose JG, Espeland MA, et al. Eating pathology and psychological outcomes in young adults in self-regulation interventions using daily self-weighing. Health Psychol. 2019;38(2):143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaRose JG, Evans Ew, Neiberg RH, et al. Dietary outcomes within the Study of Novel Approaches to Weight Gain Prevention (SNAP) randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaRose JG, Guthrie KM, Lanoye A, et al. A mixed methods approach to improving recruitment and engagement of emerging adults in behavioural weight loss programs. Obes Sci Pract. 2016;2(4):341–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carels RA, Young KM, Coit CB, et al. The failure of therapist assistance and stepped-care to improve weight loss outcomes. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(6):1460–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carels RA, Wott CB, Young KM, et al. Successful weight loss with self-help: a stepped-care approach. J Behav Med. 2009;32(6):503–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unick JL, Dorfman L, Leahey TM, et al. A preliminary investigation into whether early intervention can improve weight loss among those initially non-responsive to an internet-based behavioral program. J Behav Med. 2016;39(2):254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]