Abstract

Background:

Most states have at least one policy targeting alcohol use during pregnancy. The public health impact of these policies has not been examined.

Objective:

To examine the relationship between state-level policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy and alcohol use among pregnant women.

Methods:

Data include state-level alcohol and pregnancy policy data and individual-level U.S. BRFSS data about pregnant women’s alcohol use 1985–2016 (n=57,194). Supportive policies include Mandatory Warning Signs; Priority Substance Abuse Treatment; Reporting Requirements for Data and Treatment Purposes; and Prohibitions on Criminal Prosecution. Punitive policies include Civil Commitment; Child Protective Services Reporting Requirements; and Child Abuse/Neglect. Analyses include logistic regression models that adjust for individual-and state-level controls, include fixed effects for state and year, account for clustering by state, and weight by probability of selection.

Results:

Relative to having no policies, supportive policy environments were associated with more any drinking, but not binge or heavy drinking. Of individual supportive policies, only the following relationships were statistically significant: Mandatory Warning Signs was associated with lower odds of binge drinking; Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women and Women with Children was associated with higher odds of any drinking. Relative to no policies, punitive policy environments were also associated with more drinking, but not with binge or heavy drinking. Of individual punitive policies, only Child Abuse/Neglect was associated with lower odds of binge and heavy drinking. Mixed policy environments were not associated with any alcohol outcome.

Conclusions:

Most policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy do not appear to be associated with less alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

Introduction

Alcohol is a known teratogen that causes fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD), and other harms to fetuses (May et al., 2008; Russell & Skinner, 1988; Sokol, Delaney-Black, & Nordstrom, 2003; Strandberg-Larsen, Gronboek, Andersen, Andersen, & Olsen, 2009). Alcohol use during pregnancy is common; approximately 15% of pregnant women in the U.S. report any alcohol use and almost 3% report binge drinking (Popova, Lange, Probst, Parunashvili, & Rehm, 2017).

Almost all U.S. states have enacted one or more policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy (Roberts, Thomas, Treffers, & Drabble, 2017). The number of states with at least one such policy has increased over time, from one in 1974 to 43 in 2013 (Roberts et al., 2017). Scholars have categorized these policies into “supportive” and “punitive” (Chavkin, Wise, & Elman, 1998; Gomez, 1997). Supportive policies do not use threat of sanctions or coercion and include: warning signs; priority treatment for pregnant women or women with children; reporting requirements, when that reporting is to the health department for public health data gathering or for treatment referral purposes; and prohibitions against criminal prosecution. Punitive policies use coercion to compel behavior change and include: civil commitment; Child Protective Services (CPS) reporting requirements; and defining alcohol use during pregnancy as child abuse/neglect (Drabble, Thomas, O’Connor, & Roberts, 2014; Thomas, Rickert, & Cannon, 2006). Through the 1980s, states tended to have only punitive or only supportive policies (Roberts et al., 2017). In the 1990s, having a mix of punitive and supportive policies became the norm, with punitive policies added to supportive ones (Roberts et al., 2017). In 2013, 25 states had a punitive environment, 15 states a supportive environment, 3 states a mixed environment, and 8 states had no policies related to alcohol use during pregnancy.

A limited body of research has examined effects of policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy. A few studies have examined impacts of a federal law mandating that beverages containing alcohol have warning labels about the effects of alcohol use during pregnancy (Greenfield, Graves, & Kaskutas, 1999; Hankin et al., 1993). One recent study examining impacts of state policies requiring warning signs about effects of alcohol use during pregnancy suggests warning signs may be associated with reduced alcohol use during pregnancy, but this study only examined effects through 2010 (Cil, 2017). To date, there has been no comprehensive research examining effects of other individual state-level policies that target women’s alcohol use during pregnancy or effects of punitive, supportive, or mixed policy environments on alcohol use during pregnancy. Understanding effects of state-level policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy is important because such policies have been shown to increase adverse birth outcomes and to decrease prenatal care utilization (Subbaraman et al., 2018). Policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy also continue to be debated and enacted in individual states (Drabble et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2017), components of these policies have recently begun to be included in federal legislation (CFF, 2012), and advocates are challenging some of these policies in court (“Eloise Anderson, et al v. Tamara M. Loertscher,” 2017).

In this study, we examine associations between a range of state-level policies, as well as the overall policy environment, and drinking among a national sample of pregnant women. Although typically not stated explicitly (except related to warning signs), the intent of policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy can be assumed to be to decrease alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Thus, we would expect states with each individual policy, as well as states with only supportive, only punitive, or mixed punitive and supportive policies, would have lower alcohol use during pregnancy than states with no policy. Prohibitions against criminal prosecution could plausibly be associated with more alcohol use during pregnancy as this policy could be interpreted as the state tacitly giving permission for pregnant women to drink. Also, punitive policies could lead women to avoid prenatal care and substance use disorder treatment out of fear of punishment (Roberts & Pies, 2011), which could translate into more drinking during pregnancy in states with punitive policies.

Methods

Data sources

This study uses 1985–2016 data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) for alcohol outcomes and individual-level controls, NIAAA’s Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS) (NIAAA, 2016) and original legal research for alcohol and pregnancy policies, and secondary sources for state-level controls.

BRFSS is an annual telephone survey in the U.S. that tracks health status and health behaviors of adults to provide national and state-level estimates (CDC). BRFSS has been conducted annually since 1984, with pregnancy status assessed since 1985. During the 1980s, between 15 and 40 states participated each year. Beginning in 1992, 49 or more states participated each year. The CDC has used BRFSS data for national estimates of drinking during pregnancy since 1991 (CDC, 2009, 2012). BRFSS data are also often used in policy evaluations (McGeary, 2013; Naimi et al., 2014). BRFSS has included questions about alcohol use since the first survey, although alcohol data were not collected during even years in the 1990s. Participation rates were more than 70% in 1993, and have been closer to 50% through the 2000s (Galea & Tracy, 2007). In this study, we restricted our analyses to participants who reported that they were currently pregnant.

Alcohol and pregnancy policy statutory, regulatory, and effective date data were obtained from APIS and from original legal research using both Westlaw and HeinOnline, two online legal databases. The process for obtaining and coding these data has been described in detail elsewhere (Roberts et al., 2017). Briefly, it involved 1) identifying and gathering relevant statutes and regulations; 2) identifying effective dates for each; 3) coding policies, including ensuring inter-rater reliability; and 4) checking with states and secondary sources to ensure accuracy of data gathering and coding.

Data for state-level controls were obtained from secondary sources, including the U.S. census, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, APIS, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, National Beverage Control Association, published research (Kerr, Williams, & Greenfield, 2015), and original legal research.

Measures

Alcohol consumption data for pregnant women come from BRFSS and are measured at the individual level for the past 30 days. Alcohol outcomes were selected based on the official recommendation in the U.S. of abstinence from alcohol use during pregnancy, and literature finding increased risks of poor outcomes associated with binge and higher volume drinking (Alvik, Torgersen, Aalen, & Lindemann, 2011; Meyer-Leu, Lemola, Daeppen, Deriaz, & Gerber, 2011; O’Leary & Bower, 2012; O’Leary, Nassar, Kurinczuk, & Bower, 2009; O’Leary et al., 2010; Sayal et al., 2009; Strandberg-Larsen et al., 2009; Strandberg-Larsen et al., 2008).

Outcomes include:

1) Any alcohol (dichotomous, one or more drinks); 2) Any binge drinking [dichotomous, five or more (four or more beginning in 2006) drinks on an occasion]; 3) Heavy drinking (based on frequency, quantity, and binge drinking frequency, using indexing (Armor & Polich, 1982; Stahre, Naimi, Brewer, & Holt, 2006) and modeled as a dichotomous outcome of 16+ in the past month, or roughly four or more drinks per week, a level at which there is well documented harm (O’Leary & Bower, 2012), for the sample overall.

Although questions about alcohol consumption were asked consistently, there were some changes in wording over time. Our modeling approach (fixed effects for year) controls for measurement changes.

Individual-level controls include age (18–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–45, missing), race (White, Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American/Alaska Native, Mixed race/other/missing), marital status (married, divorced/widowed/separated, single, member of unmarried couple, missing), education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate, missing), income (in 2013 $: <=27,000, >27,000-<=49,000, >49,000 - <=88,000, >88,000, missing), tobacco (no, yes, missing), and physical activity (no, yes, missing).

State-level statutes and regulations relating to alcohol and pregnancy are the main independent variables. These include: Mandatory Warning Signs, Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women, Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women and Women with Children, Reporting Requirements for Data and Treatment Purposes, Prohibitions on Criminal Prosecution, Civil Commitment, Reporting Requirements for CPS Purposes, and Child Abuse/Neglect. These policies have been described in detail elsewhere (Roberts et al., 2017). Priority treatment for pregnant women and Priority treatment for pregnant women and women with children are considered separately because lack of childcare availability has been noted as a barrier to substance use disorder treatment for pregnant women (Terplan, Garrett, & Hartmann, 2009). Each policy is dichotomous, coded as 0 if it was not in effect for that state that year and 1 if it was in effect for that state that year.

Briefly, the first alcohol and pregnancy policies – Reporting Requirements for CPS and Child Abuse/Neglect – went into effect in Massachusetts in 1974. [See Table 1.] Mandatory Warning Signs went into effect in Washington D.C. in 1985, followed by Reporting Requirements for Data and Treatment Purposes in Kansas in 1986. Priority Treatment policies for Pregnant Women first went into effect in California and for Pregnant Women and Women with Children in Florida and Washington in 1989. Prohibitions on Criminal Prosecution first went into effect in Kentucky, Missouri, and Virginia in 1992 and Civil Commitment first went into effect in South Dakota and Wisconsin in 1998. Each policy was still in effect in at least four states in 2016. In 2016, Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women and Women with Children was the least common and Reporting for Treatment and Data Purposes the most common. The decades in which the policies were in effect for each state are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy in effect by decade and by state

| Policy | Year first went into effect | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandatory Warning Signs: Notices warning about harms from alcohol use during pregnancy must be posted in locations where alcoholic beverages are sold | 1985 | AK, CA, DC, GA, SD | AK, AZ, CA, DC, DE, GA, IL, KY, MN, NE, NH, NJ, NM, NY, OR, SD, TN, WA, WV | AK, AZ, CA, DC, DE, GA, IL, KY, MN, MO, NC, NE, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OR, SD, TN, TX, WA, WV | AK, AZ, CA, DC, DE, GA, IL, KY, MN, MO, NC, NE, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OR, SD, TN, TX, UT, WA, WV | |

| Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women: Mandatory priority access to substance abuse treatment for pregnant women who abuse alcohol | 1989 | CA | AZ, CA, GA, KS, LA, MD, WI | AK, AR, AZ, CA, CO, GA, KS, LA, MD, OK, UT, WI | AK, AR, AZ, CA, CO, GA, KS, KY, LA, MD, OK, TX, UT, WI | |

| Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women and Women with Children: Mandatory priority access to substance abuse Treatment for pregnant women and women with children who abuse alcohol | 1989 | FL, WA | DC, FL, IL, MO, WA | DC, FL, IL, MO, TX, WA, WY | DC, FL, IL, MO, WA | |

| Reporting Requirements for Treatment & Data: Mandatory or discretionary reporting of alcohol use during pregnancy for purposes of Treatment referral or data collection | 1986 | IL, KS, MN, NJ, OR | AK, CA, CO, FL, IA, IL, KS, KY, LA, MI, MN, MO, NJ, NY, OK, OR, TX, WI | AK, CA, CO, DE, FL, IA, IL, IN, KS, KY, LA, ME, MI, MN, MO, ND, NH, NJ, NV, NY, OH, OK, OR, PA, SC, SD, TX, WA, WI, WV | AK, CA, CO, DE, FL, IL, IN, KS, KY, ME, MI, MN, MO, ND, NJ, NV, NY, OH, OK, OR, PA, SC, SD, TX, WA, WI, WV | |

| Prohibitions on Criminal Prosecution: Prohibit use of medical tests (such as prenatal screening or toxicology) as evidence in criminal prosecution | 1992 | FL, KS, KY, MO, NV, VA | KS, KY, LA, MO, NV, VA | CO, KS, KY, LA, MO, NV, VA | ||

| Civil Commitment: Mandatory involuntary commitment of pregnant women to Treatment or protective custody to protect fetus from prenatal exposure to alcohol | 1998 | SD, WI | MN, ND, OK, SD, WI | MN, ND, OK, SD, WI | ||

| Reporting Requirements for CPS Purposes: Mandated or discretionary reporting of alcohol use during pregnancy for purposes of child abuse/neglect investigation | 1974 | MA | MA, MN, UT | AZ, CA, FL, KY, MA, MI, MN, RI, SD, UT, VA, WI | AK, AZ, CA, FL, IN, KY, LA, MA, ME, MI, MN, OK, PA, RI, SD, UT, VA, WI | AK, AR, AZ, CA, DC, FL, IN, KY, LA, MA, MD, ME, MI, MN, OK, PA, RI, SD, UT, VA, WI |

| Child Abuse/Neglect: Legal significance of alcohol use during pregnancy and, in some cases, defines alcohol use during pregnancy as child abuse/neglect | 1974 | MA | IL, IN, MA, NV, UT | FL, IL, IN, KY, MA, NV, RI, SC, SD, TX, UT, VA, WI | AL, AZ, CO, FL, IL, IN, KY, LA, MA, ME, ND, NV, OK, RI, SC, SD, TX, UT, VA, WI | AL, AZ, CO, FL, GA, IL, IN, KY, LA, MA, ME, ND, NV, OK, RI, SC, SD, TX, UT, VA, WI |

Bold indicates states that had the policy go into effect during that decade; grey background are supportive; white background are punitive

We created a separate variable characterizing policy environments for each state and year as supportive only (one or more of Mandatory Warning Signs, Priority Treatment, Reporting for Data and Treatment Purposes, and Prohibitions on Criminal Prosecution and no punitive policies), punitive only (one or more of Civil Commitment, Reporting for CPS Purposes, and Child Abuse/Neglect and no supportive policies), mixed supportive and punitive (one or more supportive and one or more punitive policies), and no policy.

State-level controls include state- and year-specific poverty (continuous), per capita cigarette sales (continuous, as a proxy for effective tobacco policies), and two general population alcohol policies on which data are available for our entire study time period: Blood Alcohol Concentration laws (neither a .10 or .08 law, .10 law, .08 law), and indicators for states with retail monopolies on wine or spirits (dichotomous).

Statistical analysis

To examine associations between state-level policy variables and individual-level alcohol-related outcomes, we used sample-weighted logistic regression in models that adjusted for individual-and state-level controls and included fixed effects for state and for year. Consistent with prior research examining effects of state-level policies on individual behavior with BRFSS data, standard errors were adjusted to reflect clustering by state (Friedman, Schpero, & Busch, 2016; McGeary, 2013). Fixed effects variables for state account for other characteristics of the state that might impact outcomes. Fixed effects for year account for changes in BRFSS questions over time, for changes in BRFSS sampling strategy over time, and changes in federal policy related to alcohol use during pregnancy that have occurred over time.

We first estimated models for the associations between alcohol and pregnancy policy environment (no policy, punitive, supportive, mixed) for each outcome [Model 1]. We then estimated models that included each policy in a separate model [Models 2] and finally estimated models that included all policies [Model 3] for each outcome. Our logistic regression equations testing the effects of our policy variables on alcohol use outcomes take the following general form:

where i indexes individual; s indexes state; and t indexes years; ALC represents either any drinking, any binge drinking, or any heavy drinking; Xist represents the vector of individual-level controls (i.e., for an individual in a given state and year); Xst represents the vector of time varying state-level controls; αs represents state fixed effects (i.e., vector of state indicators); and αt represents year fixed effects (i.e., vector of year indicators). βPOLICYst in Model 1 represents our policy environment variable; in Model 2 this is each individual policy, and in Model 3 this is the vector of all policies entered simultaneously. Model coefficients are expressed as odds ratios, and analyses were conducted in Stata, version 15 (StataCorp, 2017). For associations significant at a p<0.05 level, we used the post-estimation margins command to generate predicted probabilities of the outcome when the policy was versus was not in effect.

Results

Sample description

Among the 57,955 pregnant women in the BRFSS analytic sample, 57,194 answered questions about past 30 day alcohol use. The majority were under 30 (54%), White (70%), married (72%), current non-smokers (89%), and physically active (66%), and had at least some college education (62%). Respondents represented all regions in the U.S., and the majority of the sample participated in the 2000s and 2010s (77%). At the time of study participation, many respondents were living in states when supportive policies such as Reporting Requirements for Data and Treatment Purposes (47%) and Mandatory Warning Signs (41%) were in effect, and fewer were living in states when Prohibitions on Criminal Prosecution policies (9%) were in effect. Roughly a third of the respondents were living in states when punitive policies such as Child Abuse/Neglect (33%) and Reporting Requirements for CPS Purposes (31%) were in effect; only 7% were living in states when Civil Commitment policies were in effect. [See Table 2] Eleven percent reported any alcohol use, 2% reported binge drinking, and 2% reported heavy drinking. Among those who reported having at least one drink in the past 30 days, the mean number of drinks reported over the past 30 days was 14.3. Of the 1645 participants with valid binge and heavy drinking data, 24% reported binge (but not heavy) drinking, 26% reported heavy (but not binge) drinking, and 50% reported both binge and heavy drinking.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics for pregnant women in the 1985–2016 pooled BRFSS data with alcohol consumption data (n=57,194), unweighted

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–24 | 13,866 | 24.2 | |

| 25–29 | 17,200 | 30.1 | |

| 30–34 | 16,032 | 28.0 | |

| 35–39 | 7,783 | 13.6 | |

| 40–45 | 2,130 | 3.7 | |

| Missing | 183 | 0.3 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 40,080 | 70.1 | |

| Black | 5,369 | 9.4 | |

| Hispanic (any race) | 6,779 | 11.9 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1,817 | 3.2 | |

| Native American/Alaska Native | 1,200 | 2.1 | |

| Mixed race/Other/Missing | 1,949 | 3.4 | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 40,879 | 71.5 | |

| Divorced/widowed/separated | 3,563 | 6.2 | |

| Single | 9,206 | 16.1 | |

| Member of an unmarried couple | 3,447 | 6.0 | |

| Missing | 99 | 0.2 | |

| Education Level | |||

| Less than high school | 5,312 | 9.3 | |

| High school graduate | 14,694 | 25.7 | |

| Some college | 15,216 | 26.6 | |

| College graduate | 21,919 | 38.3 | |

| Missing | 53 | 0.1 | |

| Income Quartile (2013 adjusted) | |||

| <=27,000 | 12,629 | 22.1 | |

| >27, 000–<=49,000 | 12,009 | 21.0 | |

| >49,000–<=88,000 | 13,260 | 23.2 | |

| >88,000 | 13,056 | 22.8 | |

| Missing | 6,240 | 10.9 | |

| Current Tobacco Use | |||

| No | 50,589 | 88.5 | |

| Yes | 6,452 | 11.3 | |

| Missing | 153 | 0.3 | |

| Current Physical Activity | |||

| No | 14,104 | 24.7 | |

| Yes | 37,820 | 66.1 | |

| Missing | 5,270 | 9.2 | |

| U.S. Census Region Represented | |||

| Northeast | 10,140 | 17.7 | |

| Midwest | 14,144 | 24.7 | |

| South | 17,551 | 30.7 | |

| West | 15,359 | 26.9 | |

| Decade Represented | |||

| 1980s | 3,203 | 5.6 | |

| 1990s | 10,254 | 17.9 | |

| 2000s | 25,824 | 45.2 | |

| 2010s | 17,913 | 31.3 | |

| Policy Exposure | |||

| Supportive | |||

| Mandatory Warning Signs | 23,638 | 41.3 | |

| Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women | 11,632 | 20.3 | |

| Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women & Women with Children | 5,808 | 10.2 | |

| Reporting Requirements for Data and Treatment Purposes | 26,991 | 47.2 | |

| Prohibitions on Criminal Prosecution | 5,234 | 9.2 | |

| Punitive | |||

| Civil Commitment | 3,851 | 6.7 | |

| Reporting Requirements for CPS Purposes | 17,929 | 31.4 | |

| Child Abuse/Neglect | 18,632 | 32.6 | |

| Any drinking | 6,342 | 11.1 | |

| Binge drinking | 1,266 | 2.2 | |

| Heavy drinking | 1,251 | 2.2 | |

Policy environment associations with past 30 day alcohol use during pregnancy

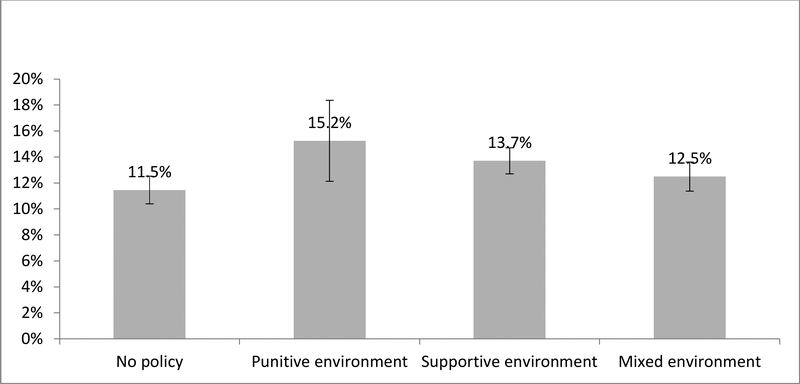

Both supportive [aOR 1.25, p=0.005] and punitive [aOR 1.44, p=0.019] environments were associated with higher odds of any alcohol use relative to environments without any policies. The predicted probability of any alcohol use when no policies were in effect was 11.5% [95% CI 10.4, 12.5], 15.2% [95% CI 12.1, 18.4] in punitive policy environments, 13.7% [12.7, 14.7] in supportive environments, and 12.5% [95% CI 11.4, 13.6] in mixed environments. [See Table 3 and Figure 1] Mixed environment was not associated with any alcohol use. In the models predicting binge drinking and predicting heavy drinking, neither supportive, punitive, nor mixed environments were associated with outcomes in either model. [See Table 3]

Table 3.

Association between state alcohol and pregnancy policy environment and alcohol use during pregnancy, Models 1

| Any alcohol use | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

| No policy | ref | ||

| Punitive environment | 1.44 | [1.06, 1.96] | 0.019 |

| Supportive environment | 1.25 | [1.07, 1.47] | 0.005 |

| Mixed policy environment | 1.11 | [0.90, 1.38] | 0.320 |

| Binge alcohol | |||

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

| No policy | ref | ||

| Punitive environment | 0.85 | [0.47, 1.56] | 0.604 |

| Supportive environment | 0.91 | [0.63, 1.32] | 0.627 |

| Mixed policy environment | 0.92 | [0.61, 1.38] | 0.682 |

| Heavy drinking | |||

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

| No policy | ref | ||

| Punitive environment | 0.60 | [0.32, 1.13] | 0.114 |

| Supportive environment | 0.87 | [0.53, 1.42] | 0.576 |

| Mixed policy environment | 0.75 | [0.45, 1.24] | 0.269 |

Models include individual-level controls (age, race, marital status, education, income, tobacco use, and physical activity) and state-level controls (% poverty, BAC laws, alcohol control state, and tobacco consumption) and fixed effects for state and year. All models were weighted and SEs were adjusted for clustering at the state level.

Figure 1.

Adjusted probabilities and 95% CIs of any alcohol by alcohol/pregnancy policy environment

Individual-policy associations with past 30 day alcohol use during pregnancy

Of individual supportive policies, Mandatory Warning Signs was associated with lower odds of binge drinking in Model 2 and Model 3 [aOR 0.54, p=0.005 and aOR 0.56, p=0.012]. The predicted probability of binge drinking when Mandatory Warning Signs was in effect was 1.8% [95% CI 1.43, 2.11] and 3.0% [95% CI 2.3, 3.7] when it was not in effect. [See Table 4 and Figure 2.] Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women and Women with Children was associated with higher odds of any alcohol in both Model 2 and Model 3 [aOR 1.28, p=0.001 and aOR 1.25, p=.001]. The predicted probability of any drinking when Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women and Women with Children was in effect was 14.8% [95% CI 13.5, 16.0] and 12.4% when it was not [95% CI 12.3, 12.6]. Prohibitions on Criminal Prosecution was associated with lower odds of heavy drinking in Model 2 [aOR 0.61, p=0.024], but not in Model 3. [See Table 4.] Of individual punitive policies, Child Abuse/Neglect was associated with lower odds of binge drinking in Model 3 [aOR 0.69, p=0.009] and with heavy drinking in both Model 2 and Model 3 [aOR 0.62, p=0.015 and aOR 0.64, p=0.004]. The predicted probability of binge drinking when Child Abuse/Neglect was in effect was 1.8% [95% CI 1.4, 2.2] and 2.6% [95% CI 2.4, 2.8] when it was not. The predicted probability of heavy drinking when Child Abuse/Neglect was in effect was 1.8% [95% CI 1.4, 2.1] and 2.6 [95% CI 2.4, 2.8] when it was not.

Table 4.

Association between state policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy and alcohol use during pregnancy

| Models 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any alcohol use | ||||||

| aOR | 95% CI | p | aOR | 95% CI | P | |

| Mandatory Warning Signs | 0.94 | [0.77, 1.15] | 0.544 | 0.95 | [0.76, 1.19] | 0.651 |

| Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women | 0.84 | [0.64, 1.11] | 0.222 | 0.91 | [0.69, 1.19] | 0.474 |

| Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women & Women with Children | 1.28 | [1.11, 1.46] | <0.001 | 1.25 | [1.10, 1.41] | <0.001 |

| Reporting Requirements for Treatment & Data | 0.95 | [0.80, 1.14] | 0.600 | 0.98 | [0.82, 1.18] | 0.880 |

| Prohibitions on Criminal Prosecution | 0.79 | [0.57, 1.09] | 0.148 | 0.75 | [0.56, 1.01] | 0.061 |

| Civil Commitment | 0.82 | [0.64, 1.04] | 0.109 | 0.84 | [0.68, 1.05] | 0.132 |

| Reporting Requirements for CPS purposes | 0.86 | [0.71, 1.05] | 0.140 | 0.93 | [0.78, 1.11] | 0.411 |

| Child Abuse/Neglect | 1.02 | [0.83, 1.23] | 0.918 | 1.05 | [0.86, 1.28] | 0.656 |

| Binge alcohol | ||||||

| aOR | 95% CI | p | aOR | 95% CI | P | |

| Mandatory Warning Signs | 0.54 | [0.35, 0.83] | 0.005 | 0.56 | [0.36, 0.88] | 0.012 |

| Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women | 0.89 | [0.51, 1.55] | 0.688 | 0.89 | [0.58, 1.38] | 0.610 |

| Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women & Women with Children | 0.66 | [0.32, 1.39] | 0.278 | 0.77 | [0.48, 1.25] | 0.293 |

| Reporting Requirements for Treatment & Data | 0.96 | [0.74, 1.25] | 0.770 | 0.97 | [0.74, 1.27] | 0.813 |

| Prohibitions on Criminal Prosecution | 0.85 | [0.49, 1.48] | 0.572 | 1.07 | [0.64, 1.78] | 0.806 |

| Civil Commitment | 1.55 | [0.82, 2.92] | 0.178 | 1.56 | [0.90, 2.70] | 0.111 |

| Reporting Requirements for CPS purposes | 1.33 | [0.96, 1.85] | 0.089 | 1.24 | [0.95, 1.62] | 0.117 |

| Child Abuse/Neglect | 0.71 | [0.49, 1.04] | 0.080 | 0.69 | [0.52, 0.91] | 0.009 |

| Heavy drinking | ||||||

| aOR | 95% CI | p | aOR | 95% CI | P | |

| Mandatory Warning Signs | 0.72 | [0.40, 1.30] | 0.277 | 0.73 | [0.42, 1.28] | 0.276 |

| Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women | 1.03 | [0.65, 1.62] | 0.911 | 0.95 | [0.61, 1.47] | 0.819 |

| Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women & Women with Children | 0.57 | [0.32, 1.03] | 0.062 | 0.65 | [0.41, 1.04] | 0.074 |

| Reporting Requirements for Treatment & Data | 0.83 | [0.64, 1.07] | 0.150 | 0.87 | [0.70, 1.08] | 0.218 |

| Prohibitions on Criminal Prosecution | 0.61 | [0.40, 0.94] | 0.024 | 0.79 | [0.49, 1.27] | 0.338 |

| Civil Commitment | 1.90 | [0.87, 4.11] | 0.105 | 1.99 | [0.82, 4.83] | 0.126 |

| Reporting Requirements for CPS purposes | 1.05 | [0.67, 1.64] | 0.826 | 1.06 | [0.73, 1.54] | 0.766 |

| Child Abuse/Neglect | 0.62 | [0.43, 0.91] | 0.015 | 0.64 | [0.47, 0.87] | 0.004 |

Model 2s examine each policy separately and include individual-level controls (age, race, marital status, education, income, tobacco use, and physical activity) and state-level controls (% poverty, BAC laws, alcohol control state, and tobacco consumption) and fixed effects for state and year. Model 3 includes all alcohol policies with covariates included in Model 1s. All Models were weighted and SEs were adjusted for clustering at the state-level.

Grey background indicates supportive; white background indicates punitive

Figure 2.

Adjusted probabilities and 95% CIs of alcohol use among pregnant women by alcohol/pregnancy policy for policies with significant associations

Note: PtxWC=Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women and Women with Children; MWS=Mandatory Warning Signs; CACN=Child Abuse/Neglect

Discussion

This is the first study to comprehensively examine multiple policies that specifically target alcohol use during pregnancy. We found that both supportive and punitive policy environments are associated with increased odds of any alcohol use during pregnancy, although not with binge or heavy drinking. We also found that few individual alcohol and pregnancy policies are associated with alcohol use during pregnancy, and that those that are are not necessarily associated with less drinking during pregnancy. The three individual alcohol and pregnancy policies that were associated with drinking during pregnancy were: Mandatory Warning Signs, Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women and Women with Children, and Child Abuse/Neglect. Mandatory Warning Signs was associated with lower odds of binge drinking. Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women and Women with Children was associated with higher odds of any drinking. Child Abuse/Neglect was associated with lower odds of binge and heavy drinking.

These findings do not indicate that there is a set of evidence-based policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy that policy makers should adopt. Combined with published data that indicates that rates of alcohol use during pregnancy have remained relatively steady since the 1990s (CDC, 2009) and that state policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy lead to increased adverse birth outcomes and decreased prenatal care utilization (Subbaraman et al., 2018), these findings indicate that new policy approaches may be needed in order to meaningfully reduce alcohol use during pregnancy and related public health harms.

There are important factors to consider in relation to the specific policies that were associated with drinking in this sample. First, while the finding of less binge drinking when Mandatory Warning Signs is in effect is consistent with what one would expect, the fact that we did not find Mandatory Warning Signs to be associated with either any alcohol use or with heavy drinking suggests that the messages may not reach female drinkers who do not binge drink. Second, the finding of Priority Treatment associated with more drinking is counter-intuitive. One possibility is that states with such a policy have fewer treatment slots available, which is why they give pregnant women priority. It is also possible that priority treatment could contribute to pregnant women understanding that there might be a benefit to disclosing alcohol use and also to destigmatizing use during pregnancy. Thus, it is possible that in states where priority treatment is in effect, pregnant women may be less likely to underreport their alcohol use. Third, while defining alcohol use during pregnancy as child abuse/neglect appears associated with less drinking, it is also possible that – due to fear of punishment – pregnant women might be less likely to report drinking in response to survey questions when policies defining alcohol use during pregnancy as child abuse/neglect are in effect. Thus, that finding should be interpreted with caution. Even if future research using different methodological approaches were to confirm this finding, the ethics of defining harm to a fetus as child abuse/neglect and possible other public health harms from such a policy need to be weighed against any public health benefit from reductions in drinking among pregnant women.

There may be a concern with endogeneity, i.e., states with more alcohol use during pregnancy or FAS may be more likely to adopt policies. We could not keep state-specific time trends in the analytic models because adding these additional parameters led to model instability. Other methods to handle policy endogeneity, such as differencing, are infeasible in analyses using individual-level data as outcomes as we have here. Differencing would also be inappropriate for BRFSS data due to measurement error inherent in survey data. We were unable to definitively rule out possible effects of endogeneity. There are some factors that suggest endogeneity may be less of a concern for this particular policy topic. In particular, data on alcohol use during pregnancy or FAS in individual states were not readily available (May & Gossage, 2001), available in a timely manner, or necessarily reliable when policies were being enacted. Also, research has also documented that policy-making on substance use and pregnancy has been driven by political concerns, such as positioning on abortion (Murphy & Rosenbaum, 1999; Paltrow, 1999; Roberts et al., 2017), and factors such as the proportion of female legislators in the state (Thomas et al., 2006), and not necessarily influenced by scientific evidence about the prevalence of FAS or alcohol use during pregnancy (Woodruff, 2017).

Limitations

First, there may be differential under-reporting of alcohol use during pregnancy across states and time. If under-reporting is lower in states with supportive policies and higher in states with punitive policies, this could explain why we did not observe effects for some policies or why we observed more drinking when Priority Treatment for Pregnant Women and Women with Children was in effect and less drinking when policies that define alcohol use during pregnancy as child abuse/neglect were in effect. Second, we did not look at FAS or FASD, but rather at alcohol consumption. Consistent data on FAS and FASD over our time period were not available. Future research should consider conducting similar analyses over a shorter time span in states with consistent FAS surveillance systems or with other indicators of effects of alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Third, we did not examine policy enforcement or women’s awareness of policies. If policies are not enforced or women not aware of them (Thomas, Cannon, & French, 2015), this could explain lack of effects. Third, alcohol use during pregnancy is not the only public health outcome of interest related to alcohol and pregnancy policies. Research has already examined the relationship between policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy and birth outcomes and prenatal care utilization (Subbaraman et al., 2018). Future research is needed to examine the relationship between policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy and outcomes such as substance use disorder treatment utilization and indicators of harm to children, such as maternal alcohol use related child developmental abnormalities or maternal alcohol use related child maltreatment. Fourth, while BRFSS includes a large sample of pregnant women, binge and heavy drinking are rare outcomes and some policies were only in effect for a small number of states for a small number of years. Thus, it is possible that our study was under-powered to detect effects, such as between Civil Commitment and binge or heavy drinking.

Strengths

To our knowledge, we are the first to consider multiple alcohol and pregnancy policies across the U.S. and the overall state-level policy environment. We also used a large, national sample that asked substantially consistent questions regarding alcohol use and used similar methodology over forty years. Our policy dataset is the first comprehensive dataset of 40 years of state-level alcohol and pregnancy policies. These policy data are based on a rigorous coding process that used consistent decision rules to guide policy classification and effective dates coding (Roberts et al., 2017).

Conclusion

Most policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy do not appear to be associated with lower levels of alcohol consumption during pregnancy. More research is needed to examine what, if any, public health benefits alcohol and pregnancy policies have.

Implications for policy

The lack of consistent lower levels of alcohol consumption during pregnancy associated with policies targeting alcohol use during pregnancy, combined with other recent research that finds adverse birth and health care utilization outcomes due to these policies (Subbaraman et al., 2018), indicates that new policy approaches to alcohol use during pregnancy may be needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anna Bernstein, Beckie Kriz, RN, MSc, Nicole Nguyen, MPH, and Heather Lipkovich, MPH for project support. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was supported by the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health [Grant R01AA023267].

Biography

Sarah C.M. Roberts, DrPH is Associate Professor at University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Roberts studies how policies and our health care system punish rather than support vulnerable pregnant women, including women seeking abortion and women who use alcohol and/or drugs.

Amy A. Mericle, PhD is a Scientist at the Alcohol Research Group, Public Health Institute. Dr. Mericle studies recovery support services for alcohol and drug use disorders as well as research methods and measurement issues in psychiatric services research.

Meenakshi S. Subbaraman, PhD, MS is Biostatistician and Co-Director of Statistical and Data Services at the Alcohol Research Group, Public Health Institute. Dr. Subbaraman studies cannabis and alcohol policy and the methods for studying mediators/mechanisms of action.

Sue Thomas, PhD is Senior Research Scientist and Director of PIRE-Santa Cruz, and specializes in the intersection of law and social science research. Her project specialties include fetal alcohol spectrum disorders policy, reproductive rights, and methodological questions pertaining to using legal data for social science research.

Ryan D. Treffers, JD is a legal policy researcher for the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation. His work largely involves conducting legal research where the law and public health intersect.

Kevin L. Delucchi, PhD is Professor at University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Delucchi is a quantitative research expert whose research focuses on the use of sophisticated statistical methods for addressing problems common in human-based research, including missing data and co-morbid conditions.

William C. Kerr, PhD is Senior Scientist and Center Director at the Alcohol Research Group, Public Health Institute. Dr. Kerr is an expert in alcohol control policy and policy evaluation as well as in the methodology of alcohol use measurement.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alvik A, Torgersen AM, Aalen OO, & Lindemann R (2011). Binge alcohol exposure once a week in early pregnancy predicts temperament and sleeping problems in the infant. Early Hum Dev, 87(12), 827–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armor DJ, & Polich JM (1982). Measurement of alcohol consumption In Pattison EM & Kaufman E (Eds.), Encyclopedic Handbook of Alcoholism (pp. 72–80). New York: Gardner Press. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. 2005 Survey Data. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss.

- CDC. (2009). Alcohol use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of childbearing age - United States, 1991–2005. MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 58(19), 529–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2012). Alcohol use and binge drinking among women of childbearing age--United States, 2006–2010. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 61(28), 534–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CFF. (2012). Children & Family Futures. Implementation of CAPTA as a policy and practice tool to reduce the impact of prenatal alcohol exposure: points of agreement. Retrieved from Children and Family Futures website: http://www.cffutures.org/files/presentations/CAPTA_Summary_Statement_%20on_%20Alcohol_%20Affected_%20Newborns.pdf

- Chavkin W, Wise PH, & Elman D (1998). Policies towards pregnancy and addiction. Sticks without carrots. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 846, 335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cil G (2017). Effects of posted point-of-sale warnings on alcohol consumption during pregnancy and on birth outcomes. J Health Econ, 53, 131–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble LA, Thomas S, O’Connor L, & Roberts SC (2014). State responses to alcohol use and pregnancy: findings from the Alcohol Policy Information System (APIS). J Soc Work Pract Addict, 14(2), 191–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Eloise, et al. v. Tamara M. Loertscher, No. 2328, 137 (S Ct 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Friedman AS, Schpero WL, & Busch SH (2016). Evidence suggests that the ACA’s tobacco surcharges reduced insurance take-up and did not Increase Smoking Cessation. Health Aff (Millwood), 35(7), 1176–1183. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, & Tracy M (2007). Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Annals of Epidemiology, 17(9), 643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez LE (1997). Misconceiving mothers: legislators, prosecutors, and the politics of prenatal drug exposure. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Graves KL, & Kaskutas LA (1999). Long-term effects of alcohol warning labels: findings from a comparison of the United States and Ontario, Canada. Psychology & Marketing, 16(3), 261–282. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin JR, Sloan JJ, Firestone IJ, Ager JW, Sokol RJ, & Martier SS (1993). A time series analysis of the impact of the alcohol warning label on antenatal drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 17(2), 284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr WC, Williams E, & Greenfield TK (2015). Analysis of Price Changes in Washington Following the 2012 Liquor Privatization. Alcohol & Alcoholism, 50(6), 654–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, & Gossage JP (2001). Estimating the prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome: a summary. Alcohol Res Health, 25, 159–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Marais AS, Hendricks LS, Snell CL, Tabachnick BG, . . . Viljoen DL (2008). Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol syndrome and partial fetal alcohol syndrome in South Africa: a third study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 32(5), 738–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeary KA (2013). The impact of state-level nutrition-education program funding on BMI: evidence from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Soc Sci Med, 82, 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Leu Y, Lemola S, Daeppen JB, Deriaz O, & Gerber S (2011). Association of moderate alcohol use and binge drinking during pregnancy with neonatal health. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 35(9), 1669–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S, & Rosenbaum M (1999). Pregnant women on drugs: combating stereotypes and stigma. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Blanchette J, Nelson TF, Nguyen T, Oussayef N, Heeren TC, . . . Xuan Z (2014). A new scale of the U.S. alcohol policy environment and its relationship to binge drinking. Am J Prev Med, 46(1), 10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA. (2016). Alcohol Policy Information System. http://www.alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/.

- O’Leary CM, & Bower C (2012). Guidelines for pregnancy: what’s an acceptable risk, and how is the evidence (finally) shaping up? Drug Alcohol Rev, 31(2), 170–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary CM, Nassar N, Kurinczuk JJ, & Bower C (2009). The effect of maternal alcohol consumption on fetal growth and preterm birth. BJOG: 116(3), 390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary CM, Nassar N, Zubrick SR, Kurinczuk JJ, Stanley F, & Bower C (2010). Evidence of a complex association between dose, pattern and timing of prenatal alcohol exposure and child behaviour problems. Addiction, 105(1), 74–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paltrow LM (1999). Punishment and Prejudice: Judging Drug-Using Pregnant Women In Hanigsberg JE & Ruddick S (Eds.), Mother Troubles (pp. 59–80). Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Popova S, Lange S, Probst C, Parunashvili N, & Rehm J (2017). Prevalence of alcohol consumption during pregnancy and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders among the general and Aboriginal populations in Canada and the United States. Eur J Med Genet, 60(1), 32–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SCM, & Pies C (2011). Complex calculations: how drug use during pregnancy becomes a barrier to prenatal care. Matern Child Health J, 15(3), 333–341. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0594-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SCM, Thomas S, Treffers R, & Drabble L (2017). Forty years of state alcohol and pregnancy policies in the USA: best practices for public health or efforts to restrict women’s reproductive rights? Alcohol and Alcoholism, 52(6), 715–721. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agx047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M, & Skinner JB (1988). Early measures of maternal alcohol misuse as predictors of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 12(6), 824–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayal K, Heron J, Golding J, Alati R, Smith GD, Gray R, & Emond A (2009). Binge pattern of alcohol consumption during pregnancy and childhood mental health outcomes: longitudinal population-based study. Pediatrics, 123(2), e289–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol RJ, Delaney-Black V, & Nordstrom B (2003). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. JAMA, 290(22), 2996–2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahre M, Naimi T, Brewer R, & Holt J (2006). Measuring average alcohol consumption: the impact of including binge drinks in quantity-frequency calculations. Addiction, 101(12), 1711–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2017). Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, Texas: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Strandberg-Larsen K, Gronboek M, Andersen AM, Andersen PK, & Olsen J (2009). Alcohol drinking pattern during pregnancy and risk of infant mortality. Epidemiology, 20(6), 884–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandberg-Larsen K, Nielsen NR, Gronbaek M, Andersen PK, Olsen J, & Andersen AM (2008). Binge drinking in pregnancy and risk of fetal death. Obstet Gynecol, 111(3), 602–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraman MS, Thomas S, Treffers R, Delucchi K, Kerr WC, Martinez P, & Roberts SCM (2018). Associations between state-level policies regarding alcohol use among pregnant women, adverse birth outcomes, and prenatal care utilization:Results from 1972–2013 Vital Statistics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terplan M, Garrett J, & Hartmann K (2009). Gestational age at enrollment and continued substance use among pregnant women in drug treatment. J Addict Dis, 28(2), 103–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S, Cannon CL, & French J (2015). The effects of state alcohol and pregnancy policies on women’s health and healthy pregnancies. The Journal of Women, Politics, and Policy(36), 68–94. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S, Rickert L, & Cannon C (2006). The meaning, status, and future of reproductive autonomy: the case of alcohol use during pregnancy. UCLA Womens Law J, 15, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff K (2017). State legislators’ use of evidence in making policy on alcohol use in pregnancy: Preliminary data from qualitative interviews. Paper presented at the American Public Health Association Annual Meeting Atlanta, Georgia [Google Scholar]