Abstract

Sexual orientation is a multidimensional construct which is increasingly recognized as an important demographic characteristic in population health research. For this study, weighted Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) data were pooled across 47 jurisdictions biennially from 2005 to 2015, resulting in a national sample of 98 jurisdiction-years (344,815 students). Respondents were a median of 15.5 years, 49.9% male, and 48.8% White. Sexual identity and behavior trends from 2005 to 2015 were assessed with logistic regression analysis. Overall, 13.9% of females and 7.0% of males identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual (LGB), or not sure, while 9.1% of females and 4.2% of males indicated both same-and-different-sex behavior or same-sex behavior. In total, 17.0% of female and 8.5% of male youth reported non-heterosexual (LGB or not sure) sexual identity, same-sex sexual behavior, or both. LGB youth were approximately twice as likely as other youth to report lifetime sexual behavior. White and Asian youth were less likely to report non-heterosexual identity and/or have engaged in same-sex sexual behaviors than youth of other races/ethnicities. Prevalence of non-heterosexual identities increased over time for both sexes, but only female youth reported significantly more same-sex behavior over time. This is the first study to simultaneously assess adolescent sexual identity and behavior over time within a national dataset. These findings are critical for understanding the sexual health needs of adolescents, and for informing sexual health policy and practice.

Keywords: Sexual minority, sexual behavior, sexual identity, Youth Risk Behavior Survey, adolescent/youth

INTRODUCTION

Researchers, policy makers, and advocates have increasingly recognized sexual orientation as an important demographic characteristic that should be assessed in population health research (Institute of Medicine Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, 2011). Sexual orientation is a multidimensional construct that has been measured using at least three distinct dimensions: identity, behavior, and attraction (Patterson, Jabson, & Bowen, 2017). People can be categorized as sexual minorities based on their self-identification (e.g., identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual [LGB]), the sex of their sexual partners (e.g., same-sex or both same-and-different-sex), and/or their attractions (e.g., same-sex or both same-and-different-sex). Each of these dimensions can be assessed independently or in combination to measure the prevalence of sexual minority status in the general population (Patterson et al., 2017).

Multiple population-based studies have documented the prevalence of sexual minority identity and behavior among U.S. adults using these metrics (Chandra, Mosher, Copen, & Sionean, 2011; Copen, Chandra, & Febo-Vazquez, 2016; Farley, Stephens, Harvey, Sikes, & Wenger, 1992; Hsieh & Ruther, 2016). However, few of these studies have examined changes in the prevalence of sexual minority status over time using more than one dimension of sexual orientation or assessed if these trends vary among demographic groups (Chandra et al., 2011; Copen et al., 2016; Patterson et al., 2017). Even fewer studies have examined these trends within nationally representative samples of youth under the age of 18 years, many of whom may not yet have engaged in sexual behavior and may self-identify as unsure of their sexual identity (Everett, Schnarrs, Rosario, Garofalo, & Mustanski, 2014; Kann et al., 2016; Mustanski et al., 2014). Given that fewer youth have engaged in sexual behavior than adults, it is particularly important to measure sexual identity in addition to sexual behavior to identify sexual minority and unsure youth populations (Johns, Zimmerman, & Bauermeister, 2013; Priebe & Svedin, 2013). Accordingly, the current study examined the prevalence of sexual minority identity and behavior in a national, demographically diverse sample of U.S. high school students over a 10-year period.

Recent studies indicate that both sexual minority identity and behavior are increasing among adults. A meta-analysis of sexual identity, behavior, and attraction using national survey data from 2002–2011 found that 3.5% of adults identified as LGB, 8.2% reported same-sex sexual behavior, and 11.0% reported same-sex attraction (Gates, 2011). Subsequently, a Gallup polling study revealed that, from 2012 to 2016, the prevalence of U.S. adults who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) increased from 3.5% to 4.1% with the greatest increase noted in female-identified and racial/ethnic minority (i.e., non-White) respondents (Gates, 2017). Interestingly, the prevalence of LGBT identity in the 2012–2016 data differed across demographic groups: across all years, LGBT identity was significantly higher among non White, female, and younger respondents. Moreover, LGBT identity increased more quickly over time among younger versus older adults.

Compared to adults, little is known about trends in dimensions of sexual orientation among national samples of U.S. youth over time. Only four federally-sponsored multistate U.S. health surveillance surveys contain questions about sexual identity and/or sexual behavior and have measured these self-reported outcomes among adolescents under 18 years of age. Three of these studies, the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) (Savin-Williams & Ream, 2007), the Growing up Today Study (GUTS) (Ziyadeh et al., 2007), and the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) (Chandra et al., 2011), have reported the prevalence of either sexual identity or behavior among youth 18 years or younger. Reports from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBS), however, have included analyses of both adolescent sexual identity and behavior since 1999 for certain jurisdictions, and since 2015 nationally (Kann et al., 2016a). A significant limitation of all these studies is the lack of separate assessment of sex assigned at birth and gender identity. The conflation of these categories, as well as the potential bias it introduces into studies of sexual orientation and behavior (Lunn, Obedin-Maliver, & Bibbins-Domingo, 2017), must be noted for any reports using these surveillance surveys, including our own. Results from each of these surveys are described below in order of the year of data collection.

Wave I of Add Health assessed sexual behavior (but not identity) among a nationally representative adolescent cohort with a mean age of 15.8 years in 1994–1995; 0.7% of males and 0.8% of females reported both-sex sexual contact, whereas 0.4% of males and females reported only same-sex sexual contact (Savin-Williams & Ream, 2007). In 1999, GUTS used attraction based questions to assess sexual identity by asking adolescent children (ages 12–18) of the participants in the Nurses’ Health II study whether they were attracted to individuals of the same and/or opposite sex. In total, 1.0% of these youth described themselves as LGB, 5.0% as “mostly heterosexual,” 2.0% as unsure, and 92.0% as heterosexual (Ziyadeh et al., 2007); sexual behavior was not assessed. The 2006–2008 NSFG assessed sexual minority behavior among youth ages 15–17, and Chandra et al. (2011) found that 10.3% of females and 1.7% of males reported any same-sex sexual behavior in their lifetimes; sexual identity and/or attraction were not reported.

Kann et al. (2011) reported state-level estimates and pooled state-level median estimates for sexual identity (9 states) and/or behavior (12 states) using combined YRBS data from 2001–2009. Kann et al. found that 1.3% of youth identified as gay or lesbian, 3.7% as bisexual, and 2.5% as unsure. For sexual behavior, 2.5% reported only same-sex sexual contact and 3.3% reported both-sex sexual contact. In 2015, the first year that the national YRBS included questions on sexual identity and behavior, Kann et al. (2016a) reported that 2.0% of U.S. high school students identified as gay or lesbian, 6.0% identified as bisexual, and 3.2% identified as not sure. Kann et al also found that 1.7% of YRBS respondents reported only same-sex sexual behavior, while 4.6% reported both same-sex and different-sex sexual behavior.

The work of Kann et al. provides a strong foundation for understanding the prevalence of sexual minority identity and behavior among high school students. However, several critical gaps remain. Kann et al. did not examine whether the prevalence of sexual identity and behavior varied over time or by the race/ethnicity of respondents. Given the myriad health disparities facing sexual minority youth (Everett et al., 2014; Marshal et al., 2013; Seth, Walker, & Figueroa, 2017), in particular youth navigating the intersectionality of multiple minority identities, monitoring the prevalence of sexual minority identity and behavior over time and across race/ethnicity is important for understanding and addressing the health needs of the general population. This is especially true if, as observed among U.S. adults (Gates, 2017), the prevalence of sexual minority identification in youth is increasing over time. The inclusion of multiple dimensions of sexual orientation in population-level health surveillance is critically important, not only because of the lower levels of sexual behavior among youth compared to adults, but also because the scope and magnitude of health disparities observed among sexual minority populations can differ based on which dimension of sexual orientation is monitored (Bostwick, Boyd, Hughes, & McCabe, 2010; Farmer, Bucholz, Flick, Burroughs, & Bowen, 2013; Johns et al., 2013; Lindley, Walsemann, & Carter, 2012; Priebe & Svedin, 2013) and by other intersecting demographics characteristics (Hsieh & Ruther, 2016).

Like income, sex, race/ethnicity, and disability, sexual orientation has been identified as a fundamental social determinant of health across the life course (Institute of Medicine Committee on Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities, 2011; Penman-Aguilar, Bouye, & Liburd, 2016). Compared to other social determinants, however, little is known about how the proportion of sexual minority individuals in society by identity and/or behavior has changed over time or how changes in this proportion may affect population health. The invisibility of sexual minority status compared to other stigmatized demographic traits (e.g., non-White race/ethnicity) further complicates this question. Social desirability bias can result in an under-reporting of stigmatized traits within survey research studies (Tourangeau & Yan, 2007). Sexual minority status is stigmatized (Herek & McLemore, 2013); therefore, survey research participants may consider questions about sexual orientation to be “sensitive” and may not disclose their sexual minority status to researchers.

Even without complete amelioration of stigma, longitudinal decreases in stigma may likewise result in increased participant reporting of stigmatized traits within survey-based research studies. Public attitudes toward LGB people have become increasingly favorable over time. These improved attitudes have been detected both by measures of interpersonal stigma administered within the general population (Helms & Waters, 2016; Herek, 2002; Herek & McLemore, 2013; Twenge, Sherman, & Wells, 2015) and by the passage of inclusive public policy measures (e.g., marriage equality). Studies have correlated decreases in sexual minority stigma at the interpersonal and structural levels with decreased health expenditures and better mental health outcomes among sexual minority populations (Duncan & Hatzenbuehler, 2014; Everett, Hatzenbuehler, & Hughes, 2016; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2012). These reductions in stigma may be responsible for the increased disclosure of sexual minority status within national studies, especially since 2014 when marriage equality was attained at the national level (Gates, 2017). The extent to which increased reporting of sexual minority status due to stigma reduction may be true among diverse sub-populations, however, remains understudied.

Recent studies show that studying the intersections of sociodemographic characteristics is of growing public health significance (Penman-Aguilar et al., 2016). One review demonstrated that measuring more than one social determinant at a time better estimates health outcomes among multiply marginalized populations, which comprise over 50% of the population (Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013). Differences in health outcomes have been detected among sexual minority populations who are also gender and/or racial/ethnic minorities compared to those who are not (Bostwick et al., 2014; Corliss et al., 2014; Lytle, De Luca, & Blosnich, 2014). Therefore, studies of the demographics of sexual minority populations should optimally report intersections with race/ethnicity, age, sex, and gender. Future work should also determine if trends in reporting of sexual minority status are changing among all demographic subpopulations at the same rate.

The Current Study

Within this study, we used pooled jurisdiction-level YRBS data from 2005–2015 to address three main study objectives: (1) to report the prevalence of U.S. high school students who identify as a sexual minority–operationalized in this study as both sexual minority identity, which includes LGB students, and non-heterosexual identity, a slightly broader category which encompasses LGB students as well as students who report a “not sure” sexual identity–and to examine trends in sexual identity over time; (2) to determine if these trends differ based on whether sexual orientation is assessed using sexual identity and/or sexual behavior; and (3) to assess the relative prevalence of different combinations of sexual identity and behavior with a focus on differences by sex and race/ethnicity.

Based upon previous analyses within the YRBS (Kann et al., 2016a) and other young adult populations (Gates, 2017), the current study tested three hypotheses related to these objectives. First, we hypothesized that the prevalence of sexual minority and non-heterosexual identity would be higher than the prevalence of sexual minority behavior among U.S. youth. Second, we hypothesized that the prevalence of (1) sexual minority and non-heterosexual identity as well as (2) sexual minority behavior would be higher among female and non-White youth (compared to male and White youth). Third, we hypothesized that the prevalence of (1) sexual minority and non-heterosexual identity as well as (2) sexual minority behavior would increase among both males and females from 2005–2015.

METHOD

Participants

The YRBS is a biennial national survey that has been conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) since 1991 to collect health data on students in Grades 9–12 (Brener et al., 2013). The YRBS monitors health-related behaviors among youth, such as alcohol and drug use, experiences with violence, suicidal ideation, sexual behaviors, and eating habits, among others (Kann et al., 2016b). For this study, we used data from local versions of the YRBS, which are administered on a state, large urban school district, or county level by departments of education or health. In this implementation, jurisdictions used a two-stage cluster sample design to identify a representative sample of students (Brener et al., 2013). In the first stage, schools were selected with a probability proportional to their enrollment. In the second stage, classes of a required subject or during a required period were randomly selected and all students within these classes were eligible to participate. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and students completed the self-administered surveys during the span of that single class period. A new sample was selected in this manner each year that the survey is administered; the same students were not followed over time. For a complete description of the sampling procedure, see Kann et al. (2016b).

Analytic Sample

Local YRBS data were pooled across multiple jurisdictions (city and state) and years (biennially from 2005–2015). The entire dataset consisted of 47 jurisdictions across 6 time points, and 541,410 youth. A total of 114 jurisdiction-years (distinct surveys administered by a particular jurisdiction in a specific year) assessed sexual identity, and 115 jurisdiction-years assessed sexual behavior (sex of sexual contacts). For the present analyses, only jurisdictionyears that assessed both sexual identity and behavior were included, resulting in a sample size of 98 jurisdiction-years (344,815 students).

Measures

All measures included in these analyses were identical across all jurisdiction-years unless otherwise noted.

Sex

Sex was determined by asking participants “What is your sex?” with the choices: (1) male or (2) female. As mentioned above, the YRBS does not ask about gender identity; therefore, we will refer only to “male” or “female” participants in this article.

Sexual Identity1

Sexual identity was assessed by asking, “Which of the following best describes you?” Response options included: (1) heterosexual (straight); (2) gay or lesbian; (3) bisexual; and (4) not sure.

Sexual Behavior2

Sexual behavior was assessed by asking, “During your life, with whom have you had sexual contact?” Response options included: (1) I have never had sexual contact; (2) females; (3) males; and (4) females and males. This variable was recoded based on the students’ reported sex. The recoded variable included four categories: no sexual partners, only different-sex partners, only same-sex partners, and both same-and-different-sex partners. Throughout, we use the term “any same-sex sexual behavior” to describe participants who reported either only same-sex sexual partners or both same-and-different-sex sexual partners.

Assessing Prevalence of Sexual Identity and Behavior

For the purposes of this study, YRBS respondents were classified as “sexual minority youth (SMY)” if they reported a sexual minority (i.e., LGB) identity, any lifetime sexual minority behavior (i.e., any same-sex sexual behavior), or both. To account for individuals who were not sure of their identity and not sexually active, YRBS respondents were classified as “non-heterosexual youth (NHY)” if they reported a non-heterosexual identity (i.e., LGB or not sure of their sexual identity), any lifetime sexual minority behavior, or both.

Race/Ethnicity

Race/ethnicity was assessed using two questions. First, participants were asked if they identified as Hispanic or Latino (yes or no). Second, participants were asked to select all of the races that applied from the following list: American Indian or Alaska Native; Asian; Black or African American; Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; and White. Using the CDC’s (2016) classification, these variables were combined into 7 racial/ethnic groups: (1) American Indian or Alaska Native; (2) Asian; (3) Black or African American; (4) Hispanic/Latino (regardless of reported race); (5) Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander; (6) White; and (7) Multiple Races (Non-Hispanic).

School Grade

Participants were asked, “In what grade are you?” Response options included: 9th grade, 10th grade, 11th grade, 12th grade, and ungraded or other grade. Students who selected “ungraded or other grade” (n = 457) were excluded from analyses.

Statistical Analysis

All data cleaning and recoding was conducted in SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Cary, NC). Analyses were carried out using SAS-Callable SUDAAN Version 11.0.1 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC) to appropriately weight estimates and to account for the complex sampling design of the YRBS. The YRBS data weights adjust for student non-response and distribution of students by grade, sex, and race/ethnicity in each jurisdiction (Brener et al., 2013).

We first conducted descriptive analyses to determine the prevalence of sexual identity, sexual behavior, and other demographics among the entire pooled sample. We conducted t-tests to test for sex differences in prevalence of sexual identity and behavior. Next, we examined the prevalence of sexual identity, behavior, and their combinations at each time point. Trends in prevalence estimates from 2005 to 2015 were examined using logistic regression. As recommended by the CDC, time was modeled as a continuous variable using orthogonal coefficients to reflect the biennial spacing of the surveys (Esser, Clayton, Demissie, Kanny, & Brewer, 2017; Troiden, 1988). These analyses were stratified by sex, controlled for grade and race/ethnicity, and assessed linear and non-linear (quadratic and cubic) trends. All cubic trends were non-significant and, as such, are not discussed further. The Bonferroni method was used to correct for multiple testing. Trend results were significant at the level p = .00125 (k = α/40). A significant p-value indicates there is evidence of a linear change. If the associated beta for the significant linear time variable is negative, there is evidence of a linear decrease. Similarly, if the associated beta is positive, there is evidence of a linear increase. The linear regression is an average measure of increase or decrease across the 6 time points. Whether the slope is significantly different from 0 is a measure of whether the trend is on average upward or downward. Finally, we examined the prevalence of sexual identity, behavior, and their combinations stratified by sex and race/ethnicity using the entire pooled sample.

Demographics

The pooled YRBS sample contained nearly equal weighted proportions of male (49.9%) and female youth (50.1%; Table 1). Nearly one-half of youth in the weighted sample identified as White (48.8%), followed by 24.7% Hispanic and 16.6% Black. The largest number of participants were in 9th grade (27.3%), with slightly decreasing representation across increasing grade (10th, 25.8%; 11th, 24.0%; 12th, 23.0%; Table 1).

Table 1:

Demographic Characteristics by Sex, 2005–2015 YRBS

| Combined | Female | Male | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | Unweighted % | N | % | N | % | |

| Female | 182,236 | 50.14 | 52.13 | 182,236 | 50.14 | N/A | |

| Male | 167,375 | 49.86 | 47.87 | N/A | 167,375 | 49.86 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| American Indian/ Alaskan Native | 5,386 | 0.86 | 1.54 | 2,511 | 0.75 | 2,875 | 0.98 |

| Asian | 25,243 | 5.43 | 7.22 | 12,724 | 5.26 | 12,519 | 5.6 |

| Black or African American | 58,363 | 16.63 | 16.69 | 31,394 | 17.26 | 26,969 | 16 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 88,333 | 24.67 | 25.27 | 46,667 | 24.84 | 41,666 | 24.5 |

| Native Hawaiian/ Other PI | 6,225 | 0.77 | 1.78 | 3,112 | 0.71 | 3,113 | 0.84 |

| White | 148,229 | 48.76 | 42.4 | 76,099 | 48.15 | 72,130 | 49.38 |

| Multiple Races | 17,832 | 2.87 | 5.1 | 9,729 | 3.03 | 8,103 | 2.71 |

| Grades | |||||||

| 9th | 94,956 | 27.34 | 27.47 | 49,299 | 26.90 | 45,657 | 27.79 |

| 10th | 91,508 | 25.75 | 26.47 | 47,967 | 25.78 | 43,541 | 25.73 |

| 11th | 85,489 | 23.95 | 24.73 | 44,694 | 24.08 | 40,795 | 23.83 |

| 12th | 73,753 | 22.95 | 21.33 | 38,529 | 23.24 | 35,224 | 22.66 |

| Sexual Identity | |||||||

| Heterosexual | 310,307 | 89.55 | 88.76 | 155,369 | 86.09 | 154,938 | 93.03 |

| Gay/Lesbian | 7,049 | 1.86 | 2.02 | 3,529 | 1.75 | 3,520 | 1.97 |

| Bisexual | 20,429 | 5.3 | 5.84 | 16,144 | 8.20 | 4,285 | 2.39 |

| Not Sure | 11,826 | 3.29 | 3.3S | 7,194 | 3.97 | 4,632 | 2.61 |

| Sexual Behavior | |||||||

| No Sex | 164,297 | 45.73 | 46.99 | 90,527 | 48.25 | 73,770 | 43.21 |

| Same Sex Only | 9,214 | 2.35 | 2.64 | 5,235 | 2.52 | 3,979 | 2.17 |

| Male and Female | 16,126 | 4.32 | 4.61 | 12,441 | 6.59 | 3,685 | 2.04 |

| Different Sex Only | 159,974 | 47.6 | 45.76 | 74,033 | 42.64 | 85,941 | 52.58 |

| Sexual Minority Youth (SMY) | |||||||

| Yes | 38,854 | 10.14 | 11.11 | 27,136 | 13.84 | 11,718 | 6.43 |

| No | 310,757 | 89.86 | 88.89 | 155,100 | 86.16 | 155,657 | 93.57 |

| Non-Heterosexual Youth (NHY) | |||||||

| Yes | 48,050 | 12.72 | 13.74 | 32,744 | 16.98 | 15,306 | 8.45 |

| No | 301,561 | 87.28 | 86.26 | 149,492 | 83.02 | 152,069 | 91.55 |

RESULTS

Prevalence of Sexual Minority Orientation

In total, 10.1% of all YRBS respondents were classified as sexual minority youth (SMY), while 12.7% were classified as non-heterosexual youth (NHY) in our analyses. Collectively, 13.8% of females and 6.4% of males were classified as SMY, while 17.0% of females and 8.5% of males were classified as NHY (Table 1)

Sexual Identity

Within the pooled sample, 7.2% of youth identified as sexual minorities (e.g., LGB). Including these, 10.5% were classified as non-heterosexual (i.e., LGB or not sure), with 3.3% reporting they were not sure. Separated by sex, 1.8% of female youth identified as lesbian, 8.2% identified as bisexual, and 4.0% identified as not sure (Table 1). Compared to female youth, substantially fewer male youth identified as non-heterosexual in the pooled sample–2.0% identified as gay, 2.4% identified as bisexual, and 2.6% identified as not sure (Table 1). There were significant sex differences in the number of students who identified as heterosexual, bisexual, and not sure (p <.0001).

Sexual Behavior

Between 2005 and 2015, reports of no lifetime sexual contact increased over time from 37.8% to 47.3% for males and from 46.0% to 51.4% for females (Table 4). A total of 6.7% of respondents reported engaging in any lifetime same-sex behavior. In total, 9.1% of female youth reported any lifetime same-sex sexual behavior–2.5% with only same-sex partners and 6.6% with both same-and-different-sex partners (Table 1). Compared to female youth, fewer male youth reported sexual minority behavior–2.2% reported only same-sex partners and 2.0% reported both same-and-different-sex partners (Table 1). There were significant sex differences in the number of students who reported no lifetime sexual contact, same-and-different-sex partners, and different-sex partners (p <.0001).

Table 4:

Sexual Behavior over Time among Male and Female Youth

| Male Youth Sexual Behavior | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | Combined | Change 2005–2015a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | β | p | |

| No Sex | 4117 | 37.83 | 5059 | 37.56 | 6153 | 37.22 | 10255 | 40.98 | 14764 | 41.56 | 22099 | 47.25 | 62447 | 43.16 | 046 | < .0001 |

| Same Sex Only | 176 | 2.17 | 267 | 2.53 | 317 | 2.25 | 539 | 2.19 | 850 | 2.15 | 1283 | 2.11 | 3432 | 2.17 | −0.11 | .326 |

| Male and Female | 184 | 1.77 | 239 | 2.11 | 287 | 2.16 | 511 | 2.07 | 757 | 2.06 | 1112 | 2.03 | 3090 | 2.04 | 0.00 | .9954 |

| Different Sex Only | 5133 | 58.22 | 6899 | 57. 8 | 7717 | 58.37 | 13189 | 54.76 | 17553 | 54.23 | 23953 | 48.62 | 74444 | 52.63 | −.44 | < .0001 |

| Female Youth Sexual Behavior | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | Combined | Change 2005–2015a | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | β | p | |

| No Sex | 5119 | 45.59 | 6359 | 42.99 | 8164 | 45.66 | 12465 | 44.35 | 17938 | 47.28 | 27173 | 51.37 | 77218 | 48.23 | 0.34 | < .0001 |

| Same Sex Only | 152 | 1 5 | 262 | 2.42 | 392 | 2.14 | 653 | 2.38 | 1027 | 2.34 | 1927 | 2.81 | 4413 | 2.5 | 0.38 | < .0001 |

| Male and Female | 390 | 4.59 | 676 | 5.74 | 945 | 5.6 | 1780 | 6.68 | 2563 | 7.32 | 3912 | 6.57 | 10266 | 6.55 | 0.2 | .0006 |

| Different Sex Only | 4506 | 47.92 | 6092 | 48.85 | 6942 | 46.59 | 11347 | 46.58 | 15219 | 43.06 | 20056 | 39.25 | 64182 | 42.72 | −0 43 | < .0001 |

Linear trend based on trend analyses using logistic regression model controlling for grade and race/ethnicity, p <.05

Trends in Sexual Minority Identity and Behavior over Time

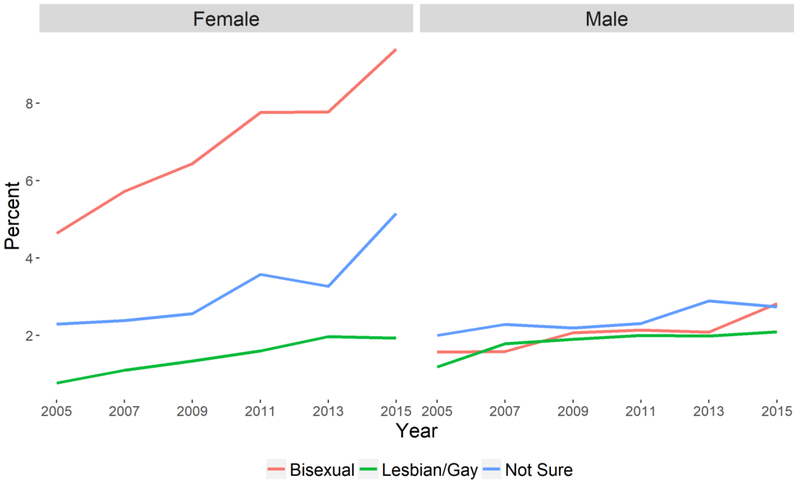

There were significant increases between 2005 and 2015 in the proportion of female youth who identified as lesbian (0.8% to 1.9%; p < .0001), bisexual (4.6% to 9.4%; p < .0001), and not sure (2.3% to 5.2%; p < .0001) (Table 2). Similar to female youth, there were significant increases in the proportion of male youth who identified as non-heterosexual between 2005 and 2015; however, the magnitude of change was much smaller (gay: 1.2% to 2.1%, p = .0012; bisexual: 1.6% to 2.8%, p < .0001 (Table 3). All non-heterosexual identity trends are visualized in Figure 1.

Table 2:

Sexual Identity and Sexual Behavior Trends among Female Youth

| 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | Combined | Change 2005–2015a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | β | p | |

| Heterosexual | 9326 | 92.3 | 12116 | 90.81 | 14414 | 89.66 | 22661 | 87.07 | 31662 | 86.97 | 43647 | 83.53 | 133826 | 86.19 | −0.7 | < .0001 |

| No sex | 4847 | 47.49 | 6006 | 44.82 | 7529 | 47.33 | 11279 | 46.4 | 16295 | 49.96 | 23740 | 53.69 | 69696 | 50.4 | 0.38 | < .0001 |

| Same Sex Only | 96 | 1.21 | 148 | 1.65 | 218 | 1.61 | 338 | 1.55 | 485 | 1.11 | 757 | 1.33 | 2042 | 1.134 | −0.25 | .0443 |

| Male and Female | 123 | 1.64 | 208 | 2.32 | 240 | 2.02 | 521 | 2.04 | 759 | 2.63 | 1062 | 2 1 | 2915 | 2.21 | 0.07 | .4777 |

| Different Sex Only | 4258 | 49.66 | 5754 | 51.22 | 6427 | 49.05 | 10523 | 50.01 | 14123 | 46.29 | 108088 | 42. 88 | 59173 | 46.05 | −0.38 | < .0001 |

| Lesbian | 90 | 0.77 | 158 | 1.1 | 244 | 1.34 | 405 | 1.6 | 701 | 1.97 | 1292 | 1.93 | 2890 | 1.75 | 0.63 | < .0001 |

| No sex | 20 | 15.37 | 29 | 16.67 | 60 | 31.62 | 123 | 24.57 | 170 | 23.18 | 312 | 26.74 | 714 | 25.24 | 0.27 | .37 |

| Same Sex Only | 33 | 24.92 | 71 | 44.18 | 104 | 33.22 | 152 | 35.66 | 292 | 43.06 | 660 | 48.28 | 1312 | 43.47 | 0.88 | < .0001 |

| Male and Female | 23 | 41.93 | 45 | 30.3 | 62 | 25.78 | 92 | 28.48 | 177 | 27.32 | 227 | 18.37 | 626 | 23.55 | −0.96 | .0001 |

| Different Sex Only | 14 | 17.78 | 13 | 8.84 | 18 | 11.38 | 38 | 11.29 | 62 | 6.44 | 93 | 6.61 | 238 | 7.74 | −0.93 | .0116 |

| Bisexual | 498 | 4.64 | 779 | 5.72 | 1285 | 6.44 | 2312 | 7.76 | 3070 | 7.78 | 5543 | 9.4 | 13387 | 8.1 | 0.57 | < .0001 |

| No sex | 126 | 21.03 | 157 | 17.53 | 326 | 24.4 | 530 | 23.07 | 745 | 22.02 | 1670 | 32.34 | 3554 | 27.29 | 0.48 | .0269 |

| Same Sex Only | 18 | 3.53 | 39 | 7.3 | 52 | 3.43 | 135 | 4.32 | 190 | 5.11 | 392 | 6.7 | 826 | 5.73 | 0.56 | .0187 |

| Male and Female | 204 | 50.75 | 356 | 47.93 | 548 | 44.49 | 1017 | 47.55 | 1389 | 49.17 | 2186 | 38.77 | 5700 | 43.43 | −0.44 | < .0001 |

| Different Sex Only | 130 | 24.68 | 227 | 27.23 | 359 | 27.68 | 530 | 25.06 | 746 | 23.7 | 1295 | 22.19 | 3307 | 23.56 | −0.27 | .0334 |

| Not Sure | 253 | 2.29 | 336 | 2.38 | 500 | 2.56 | 967 | 3.58 | 1334 | 3.27 | 2586 | 5.15 | 5976 | 3.97 | 0.83 | < .0001 |

| No sex | 126 | 46.25 | 167 | 46.62 | 249 | 48.23 | 533 | 49.43 | 728 | 50.72 | 1451 | 57.64 | 3254 | 54.05 | 0.75 | < .0001 |

| Same Sex Only | 5 | 1.37 | 4 | 0.85 | 18 | 2.86 | 28 | 3.67 | 60 | 3.8 | 118 | 2.74 | 233 | 2.98 | 0.28 | .4019 |

| Male and Female | 38 | 17.61 | 67 | 23.53 | 95 | 22.18 | 150 | 21.28 | 238 | 20.24 | 437 | 15.82 | 1025 | 18.04 | −0.47 | .0062 |

| Different Sex Only | 84 | 34.77 | 98 | 28.99 | 138 | 26.73 | 256 | 25.62 | 308 | 25.24 | 580 | 23.8 | 1464 | 24.93 | −0.22 | .3976 |

Linear trend based on trend analyses using logistic regression model controlling for grade and race/ethnicity, p <.05

Table 3:

Sexual Identity and Sexual Behavior Trends among Male Youth

| 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | Combined | Change 2005–2015a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | β | p | ||

| Heterosexual | 9106 | 95.25 | 11819 | 94.37 | 13529 | 93.84 | 22798 | 93.55 | 31418 | 93.04 | 44368 | 92.35 | 133038 | 93.05 | −0.36 | < .0001 |

| No sex | 3958 | 38.25 | 4875 | 37.38 | 5799 | 37.24 | 9577 | 40.93 | 13819 | 41.91 | 20583 | 47.83 | 58611 | 43.5 | 0.48 | < .0001 |

| Same Sex Only | 102 | 1.35 | 140 | 1.64 | 159 | 1.18 | 275 | 1.17 | 404 | 1.02 | 518 | 0.7 | 1598 | 0.96 | −0.65 | < .0001 |

| Male and Female | 56 | 0.62 | 69 | 0.74 | 97 | 0.67 | 156 | 0.78 | 225 | 0.59 | 337 | 0.63 | 943 | 0.65 | −0.13 | .592 |

| Different Ses Only | 4990 | 59.78 | 6735 | 59.75 | 7478 | 60.91 | 12790 | 57.12 | 16967 | 56.48 | 22930 | 50.84 | 71886 | 54.88 | −0.4 | < .0001 |

| Gay | 124 | 1.18 | 188 | 1.78 | 285 | 1.9 | 493 | 2 | 690 | 1.98 | 1153 | 2.09 | 2933 | 1.98 | 0.23 | .0012 |

| No sex | 28 | 23.37 | 33 | 28.33 | 98 | 32.86 | 183 | 26.88 | 205 | 30.87 | 329 | 30.73 | 876 | 31.45 | −0.07 | .7552 |

| Same Sex Only | 44 | 49.73 | 86 | 33.72 | 99 | 39.53 | 171 | 37.39 | 278 | 39.3 | 496 | 45.73 | 1174 | 42.02 | −0.33 | .1875 |

| Male and Female | 30 | 17.74 | 36 | 18.07 | 32 | 9.68 | 52 | 8.37 | 90 | 11.67 | 140 | 11.65 | 380 | 11.52 | 0.04 | .8673 |

| Different Sex Only | 22 | 9.16 | 33 | 19.88 | 56 | 17.93 | 87 | 17.36 | 117 | 18.16 | 188 | 11.84 | 503 | 15.02 | −0.05 | .7997 |

| Bisexual | 166 | 1.57 | 225 | 1.58 | 340 | 2.07 | 564 | 2.14 | 816 | 2.08 | 1404 | 2.82 | 3515 | 2.36 | 0.52 | < .0001 |

| Noses | 40 | 18,37 | 51 | 25.36 | 103 | 29.87 | 167 | 32.29 | 241 | 29.54 | 456 | 36.87 | 1058 | 33.17 | 0.73 | .0013 |

| Same Sex Only | 22 | 13.54 | 30 | 12.48 | 40 | 11.68 | 57 | 10.67 | 107 | 11.65 | 168 | 12.31 | 424 | 11.96 | 0.04 | .9012 |

| Male and Female | 63 | 46.32 | 96 | 38.42 | 109 | 37.72 | 203 | 26.54 | 279 | 36.71 | 406 | 29.05 | 1156 | 33.19 | −0.65 | .0047 |

| Different Sex Only | 41 | 21.57 | 48 | 23.74 | 88 | 20.73 | 137 | 20.5 | 189 | 22.1 | 374 | 21.73 | 877 | 21.68 | 0.01 | .9773 |

| Not Sure | 214 | 2 | 232 | 2.28 | 320 | 2.19 | 639 | 2.31 | 1000 | 2.89 | 1522 | 2.74 | 3927 | 2.62 | 0.28 | .0056 |

| No sex | 91 | 41.3 | 100 | 39.9 | 153 | 47.36 | 328 | 54.46 | 499 | 46.3 | 731 | 50.95 | 1902 | 48.95 | 0.17 | .4291 |

| Same Sex Only | 8 | 3.88 | 11 | 8.43 | 19 | 6.56 | 35 | 5.02 | 61 | 6.32 | 101 | 5.86 | 236 | 6.00 | −0.07 | .8651 |

| Male and Female | 35 | 12.46 | 38 | 21.35 | 49 | 25.59 | 100 | 17.07 | 160 | 17.7 | 229 | 13.75 | 611 | 16.43 | −0.37 | .1574 |

| Different Sex Only | 80 | 41.86 | 83 | 30.32 | 99 | 20.49 | 175 | 23.45 | 280 | 29.67 | 461 | 29.44 | 1178 | 28.62 | −0.03 | .878 |

Linear trend based on trend analyses using logistic regression model controlling for grade and race/ethnicity, p <.05

Figure 1:

Sexual Identity by Sex over Time among Non-Heterosexual Youth: YRBS 2005–2015

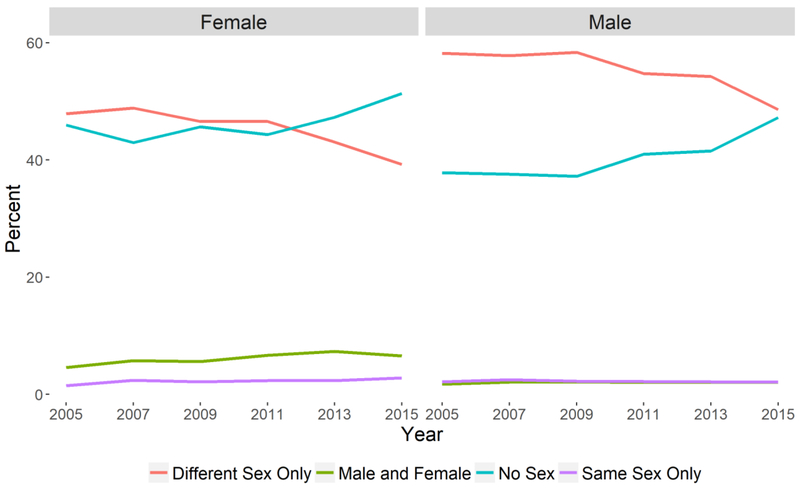

In conjunction with an increase in minority sexual identity, the proportion of female youth who reported sexual minority behavior significantly increased from 2005 to 2015. The percent of female youth who reported only same-sex partners increased from 1.5% to 2.8% (p < .0001) and the percent of female youth who reported both same-and-different-sex partners increased from 4.6% to 6.6% (p = .0006) (Table 4). Unlike among female youth, there were no significant changes in sexual minority behavior among male youth for reports of only same-sex partners (p = .326) or reports of both same-and-different-sex partners (p = .9954) (Table 4). All sexual behavior trends are visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Sexual Behavior by Sex over Time: YRBS 2005–2015

Intersections of Sexual Identity and Behavior

In addition to analyzing sexual identity and behavior separately, we also explored how sexual identity and behavior intersect for both females (Table 2) and males (Table 3) over time. When accounting for sexual identity among both male and female youth across all years in the pooled YRBS dataset, SMY were significantly more likely to report any lifetime sexual behavior than heterosexual or unsure youth. Overall, 25.2% of lesbian female youth and 27.3% of bisexual female youth reported that they had never had sex compared to 50.4% of all heterosexual and 54.1% of unsure female youth. Similarly, 31.5% of gay male youth and 33.2% of bisexual male youth reported that they had never had sex compared to 44.0% of heterosexual male youth and 49.0% of unsure male youth.

Among heterosexual and not sure youth, the most common response option selected for sexual behavior was “no sex,” followed by “different sex only.” Small percentages of heterosexual youth reported only same-sex partners (1.0% of males and 1.1% of females) and both same-and-different-sex partners (0.7% of males and 2.2% of females). In contrast, larger percentages of unsure youth reported sexual minority behavior. Specifically, 21.0% of unsure female youth and 22.4% of unsure male youth reported any lifetime same-sex sexual behavior, including 16.4% of unsure males and 18.0% of unsure females who reported both same-and-different-sex partners, and 6.0% of unsure males and 3.0% of unsure females who reported only same-sex partners.

Compared to heterosexual and not sure youth, students reporting sexual minority (i.e., LGB) identities reported more same-sex sexual behaviors. The most common response option for sexual behavior among gay male and lesbian female youth was “same sex only” followed by “no sex.” Sizeable percentages of gay males also reported both same-and-different-sex partners (11.5%) and only different-sex partners (15.0%). Lesbian female youth were more likely to report both same-and-different-sex partners (23.6%) than only different-sex partners (7.7%). In contrast, among bisexual male youth, identical percentages reported both same-and-different-sex partners (33.2%) and no sex (33.2%), while nearly twice as many reported only different-sex partners (21.7%) as only same-sex partners (12.0%). Bisexual females most commonly reported sex with both same-and-different-sex partners (43.4%) followed by no sex (27.3%). Notably, bisexual female youth were over four times more likely to report sex with only different-sex partners (23.6%) than with only same-sex partners (5.7%).

In addition to increases in reporting of same-sex sexual behaviors, the proportion of youth reporting “no sex” increased from 2005 to 2015 among females who identified as not sure, and males who identified as bisexual. Among females who identified as heterosexual, the proportion of youth reporting “no sex” increased from 2011 to 2015, and from 2009 to 2015 among males who identified as heterosexual (Tables 2 and 3). Despite the overall decreasing trend in reported sexual behavior from 2005 to 2015, there was a statistically significant increase in reporting only same-sex partners among lesbian females from 24.9% to 48.3% (Table 2). Statistically significant decreases in reporting sexual behavior with both same-and-different-sex partners were also observed among bisexual female youth from 2005–2015 (Table 2). In contrast, there was no significant change in reporting same-sex behavior among male NHY (Table 3).

Sexual Identity and Behavior Intersections by Race/Ethnicity

Finally, we examined racial/ethnic differences in sexual identity, behavior, and their intersections using the pooled YRBS dataset (i.e., combining 2005–2015). Overall, both male and female White and Asian youth were the least likely to identify as sexual minorities (Tables 5 and 6), whereas multiracial female youth were the most likely to identify as sexual minorities (13.7% of multiracial female youth identified as lesbian or bisexual) (Table 5).

Table 5:

Sexual Identity and Sexual Behavior among Female Youth by Race/Ethnicity

| White | Black | Hispanic/Latino | Asian | American Indian/Alaskan |

Native Hawaiian/Other |

Multiple | Combined | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Heterosexual | 67016 | 88.04 | 26019 | 84.08 | 38525 | 84.28 | 11295 | 88.13 | 2012 | 82.19 | 2643 | 80.33 | 7859 | 80.06 | 155369 | 86.09 |

| No sex | 34038 | 47.87 | 12963 | 48.28 | 19648 | 52.51 | 8305 | 71.46 | 1063 | 51.82 | 1302 | 51.16 | 3993 | 48.89 | 81312 | 50.42 |

| Same Sex Only | 741 | 1.06 | 528 | 1.73 | 718 | 1.69 | 140 | 0 88 | 45 | 2.23 | 68 | 3.49 | 110 | 0.89 | 2350 | 1.34 |

| Male and Female | 1423 | 2.25 | 696 | 2.38 | 931 | 2.21 | 96 | 0.82 | 46 | 1.62 | 53 | 2.19 | 282 | 3.8 | 3527 | 2.22 |

| Different Sex Only | 30814 | 48. 82 | 11832 | 47.61 | 17228 | 43.59 | 2754 | 26.85 | 858 | 44.33 | 1220 | 43.16 | 3474 | 46.43 | 68180 | 46.02 |

| Lesbian | 1072 | 1.44 | 910 | 2.63 | 1070 | 1.87 | 121 | 0.81 | 56 | 2.02 | 72 | 2.18 | 228 | 1.95 | 3529 | 1.75 |

| No sex | 312 | 27.52 | 196 | 22.18 | 241 | 24.7 | 55 | 44.03 | 16 | 29.02 | 16 | 13.42 | 53 | 17.58 | 889 | 25.34 |

| Same Sex Only | 434 | 36.26 | 458 | 48.82 | 502 | 51.29 | 38 | 38.8 | 22 | 39.27 | 30 | 28.29 | 104 | 49 | 1588 | 43.97 |

| Male and Female | 255 | 28.26 | 176 | 20.86 | 227 | 17.9 | 21 | 12.8 | 9 | 24.15 | 16 | 51.2 | 54 | 18.36 | 758 | 23.03 |

| Different Sex Only | 71 | 7.97 | 80 | 8.15 | 100 | 6.12 | 7 | 4.38 | 9 | 7.56 | 10 | 7.09 | 17 | 15.06 | 294 | 7.66 |

| Bisexual | 5534 | 6.99 | 3232 | 9.63 | 5046 | 9.76 | 589 | 5.14 | 309 | 10.12 | 252 | 6.47 | 1182 | 11.71 | 16144 | 8.2 |

| No sex | 1569 | 25.81 | 807 | 21.88 | 1340 | 30.53 | 268 | 64.02 | 73 | 17.34 | 65 | 20.99 | 304 | 20.23 | 4426 | 27.32 |

| Same Sex Only | 271 | 5.36 | 268 | 7.87 | 319 | 5.21 | 45 | 4.37 | 22 | 9.45 | 23 | 9.55 | 72 | 5.52 | 1020 | 5.86 |

| Male and Female | 2311 | 45.48 | 1452 | 45.51 | 2145 | 40.57 | 146 | 16.82 | 131 | 54.06 | 105 | 42.92 | 557 | 52.99 | 6847 | 43.48 |

| Different Sex Only | 1383 | 23.36 | 705 | 24.73 | 1242 | 23.69 | 130 | 14.8 | 83 | 19.15 | 59 | 26.53 | 249 | 21.27 | 3851 | 23.34 |

| Not Sure | 2477 | 3.53 | 1233 | 3.66 | 2026 | 4.09 | 719 | 5.92 | 134 | 5.67 | 145 | 11.01 | 460 | 6.28 | 7194 | 3.97 |

| No sex | 1421 | 55.16 | 576 | 46.85 | 953 | 52.43 | 567 | 74.69 | 77 | 57.79 | 71 | 77.35 | 235 | 42.05 | 3900 | 54.51 |

| Same Sex Only | 64 | 2.02 | 75 | 4.96 | 85 | 3.03 | 16 | 1.78 | 7 | 1.26 | 7 | 0.76 | 23 | 7.7 | 277 | 2.97 |

| Male and Female | 395 | 16.91 | 276 | 21.17 | 432 | 21.27 | 58 | 5.05 | 22 | 19.72 | 33 | 14.26 | 93 | 20.48 | 1309 | 17.92 |

| Different Sex Only | 597 | 25.91 | 306 | 27.03 | 556 | 23.27 | 78 | 18.47 | 28 | 21.24 | 34 | 7.64 | 109 | 29.77 | 1708 | 24.6 |

Table 6:

Sexual Identity and Sexual Behavior among Male Youth by Race/Ethnicity

| White | Black | Hispanic/Latino | Asian | American Indian/Alaskan |

Native Hawaiian/Other |

Multiple | Combined | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Heterosexual | 67642 | 93.94 | 24965 | 92.93 | 38125 | 91.86 | 11526 | 92.98 | 2579 | 87.56 | 2772 | 88.08 | 7329 | 91.28 | 154938 | 93.03 |

| No sex | 32808 | 46.14 | 7859 | 30.44 | 15073 | 40.43 | 8047 | 71.8 | 1075 | 42.97 | 1156 | 44.55 | 3190 | 43.53 | 69168 | 43.58 |

| Same Sex Only | 514 | 0.76 | 478 | 1.83 | 507 | 0.88 | 106 | 0.47 | 30 | 0.7 | 56 | 0.97 | 91 | 0.93 | 1782 | 0.95 |

| Male and Female | 465 | 0.68 | 170 | 0.65 | 290 | 0.62 | 48 | 0.34 | 21 | 0.9 | 31 | 0.78 | 62 | 0.56 | 1087 | 0.64 |

| Different Sex Only | 33855 | 52.42 | 16458 | 67.07 | 22255 | 58.06 | 3325 | 27.39 | 1453 | 55.43 | 1569 | 53.7 | 3986 | 54.99 | 82901 | 54.83 |

| Gay | 1193 | 1.63 | 646 | 2.19 | 1050 | 2.42 | 224 | 1.36 | 78 | 2.08 | 105 | 5.94 | 224 | 2.81 | 3520 | 1.97 |

| No sex | 405 | 32.54 | 167 | 28.71 | 263 | 29.13 | 96 | 42.27 | 11 | 12.2 | 35 | 52.86 | 61 | 21.8 | 1038 | 31.1 |

| Same Sex Only | 482 | 40.86 | 226 | 39.76 | 467 | 45.47 | 77 | 37.48 | 36 | 56.93 | 33 | 30.22 | 98 | 60.2 | 1419 | 42.56 |

| Male and Female | 158 | 12.48 | 83 | 12.28 | 134 | 10.15 | 20 | 10.52 | 10 | 7.58 | 18 | 9.57 | 31 | 9.82 | 454 | 11.44 |

| Different Sex Only | 148 | 14.12 | 170 | 19.25 | 186 | 15.24 | 31 | 9.73 | 21 | 23.28 | 19 | 7.34 | 34 | 8.19 | 609 | 14.9 |

| Bisexual | 1609 | 2.22 | 690 | 2.48 | 1241 | 2.62 | 256 | 1.81 | 91 | 4.92 | 106 | 2.18 | 292 | 3.21 | 4285 | 239 |

| No sex | 598 | 33.47 | 162 | 18.3 | 318 | 35.1 | 133 | 56.37 | 30 | 56.16 | 28 | 21.03 | 74 | 29.31 | 1343 | 32.57 |

| Same Sex Only | 137 | 9.74 | 105 | 18.49 | 164 | 12.33 | 33 | 11.29 | 8 | 2.00 | 16 | 26.73 | 34 | 13.87 | 497 | 12.08 |

| Male and Female | 461 | 32.56 | 256 | 41.14 | 453 | 33.58 | 47 | 14.51 | 24 | 18.28 | 31 | 32.9 | 109 | 34.09 | 1381 | 33.26 |

| Different Sex Only | 413 | 24.23 | 167 | 22.07 | 306 | 18.99 | 43 | 17.83 | 29 | 23.56 | 31 | 19.34 | 75 | 22.72 | 1064 | 22.09 |

| Not Sure | 1686 | 2.21 | 668 | 2.4 | 1250 | 3.1 | 513 | 3.85 | 127 | 5.44 | 130 | 3.8 | 258 | 2.69 | 4632 | 2.61 |

| No sex | 887 | 51.79 | 264 | 36.86 | 471 | 43.12 | 367 | 74.86 | 56 | 54.27 | 60 | 49.44 | 116 | 48.36 | 2221 | 48.9 |

| Same Sex Only | 85 | 7.91 | 58 | 696 | 93 | 4.02 | 14 | 3.18 | 6 | 1.34 | 8 | 6.12 | 17 | 10.95 | 281 | 6.17 |

| Male and Female | 261 | 14.47 | 103 | 21.93 | 246 | 18.4 | 55 | 7.64 | 23 | 16.5 | 20 | 7.76 | 55 | 21.26 | 763 | 16.3 |

| Different Sex Only | 453 | 25.83 | 243 | 34.24 | 440 | 34.45 | 77 | 14.31 | 42 | 27.88 | 42 | 36.68 | 70 | 19.44 | 1367 | 28.63 |

Both male and female Asian youth were the least likely to report any lifetime sexual behavior (Table 7). Asian youth were also the least likely to report any same-sex sexual behavior (2.3% of Asian males and 3.4% of Asian females). Among females, multiracial youth were the most likely to report any same-sex sexual behavior (13.7%), followed by American Indian/Alaskan Native youth (12.1%). Among all males, the youth most likely to report any same-sex sexual behavior were multiracial (5.7%), Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander (5.7%), and Black (5.6%).

Table 7:

Sexual Behavior by Race/Ethnicity among Male and Female High School Aged Youth

| Sexual Behavior Female Youth | White | Black | Hispanic/Latino | Asian | American Indian/Alaskan |

Native Hawaiian/Other |

Multiple | Combined | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–2015 | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| No sex | 37340 | 46.29 | 14542 | 45 | 22182 | 49.84 | 9195 | 71.04 | 1229 | 48.21 | 1454 | 51.27 | 4585 | 44.49 | 90527 | 48.25 |

| Same Sex Only | 1510 | 1.9 | 1329 | 3.68 | 1624 | 3.02 | 239 | 1.42 | 96 | 3.66 | 128 | 4.12 | 309 | 2.8 | 5235 | 2.52 |

| Male and Female | 4384 | 6.16 | 2600 | 7.71 | 3735 | 7.02 | 321 | 1.99 | 208 | 8.4 | 207 | 7.23 | 986 | 10.89 | 12441 | 6.59 |

| Different Sex Only | 32865 | 45.65 | 12923 | 43.62 | 19126 | 40 11 | 2969 | 25.55 | 978 | 39.73 | 1323 | 37.39 | 3849 | 41.82 | 74033 | 42.64 |

| Sexual Behavior Male Youth | White | Black | Hispanic/Latino | Asian | American Indian/Alaskan |

Native Hawaiian/Other |

Multiple | Combined | ||||||||

| 2005–2015 | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| No sex | 34698 | 45.76 | 8452 | 30.26 | 16125 | 40.1 | 8643 | 71.23 | 1172 | 43.59 | 1239 | 44.71 | 3441 | 42.59 | 73770 | 43.21 |

| Same Sex Only | 1218 | 1.78 | 867 | 3.2 | 1231 | 2.36 | 230 | 1.28 | 80 | 1.97 | 113 | 3.46 | 240 | 3.28 | 3979 | 2.17 |

| Male and Female | 1345 | 1.88 | 612 | 2.42 | 1123 | 2.27 | 170 | 1.01 | 78 | 2.75 | 100 | 2.27 | 257 | 2.45 | 3685 | 2.04 |

| Different Sex Only | 34869 | 50.58 | 17038 | 64.12 | 23187 | 55.27 | 3476 | 26.47 | 1545 | 51.69 | 1661 | 49.55 | 4165 | 51.68 | 85941 | 52.58 |

Similar to the overall sample, SMY were more likely to report any lifetime sexual behavior compared to heterosexual and unsure youth regardless of sex and race/ethnicity. However, this trend was weakest among Black male youth, due to the comparatively lower percentage of Black heterosexual (30.0%) and unsure (36.0%) males who reported no sex (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

By utilizing a diverse, national dataset we were able to provide estimates of sexual minority identity and behavior among U.S. high school aged youth. Additionally, we examined whether the prevalence of SMY and NHY changed over a period of 10 years to address three hypotheses grounded in previous literature. Consistent with our first hypothesis and with prior studies of sexual orientation among adolescents (Kann et al., 2016a), a lower percentage of youth reported any lifetime same-sex sexual behavior (6.7%) than a sexual minority (LGB) identity (7.2%) or a non-heterosexual (LGB or unsure) identity (10.5%). These three groups were found to be significantly different from each other (p <.0001). The lower prevalence of sexual minority behavior compared to identity among youth within the 2015 YRBS contrasts with the pattern observed among adults in the NSFG (Chandra et al., 2011; Copen et al., 2016), which likely reflects the fact that adolescents have had less time to accumulate sexual experience compared to adults– approximately half of the youth in the YRBS sample reported any lifetime sexual behavior, compared with approximately 90–95% of adults (Copen et al., 2016; Gates, 2017).

Hypotheses 2a and 2b were both supported for sex, but only partially supported for race/ethnicity. Consistent with previous research with youth (Hu, Xu, & Tornello, 2016; Savin-Williams, Joyner, & Rieger, 2012) and adults (Copen et al., 2016; Gates, 2017), we found that female youth were more likely than male youth to report a sexual minority identity (10.0% vs. 4.4%) or a non-heterosexual identity (13.9% vs. 7.0%). These differences are likely driven by female youth being three times more likely to identify as bisexual than their male counterparts. As previously observed (Chandra et al., 2011), sex differences were also observed for sexual behavior: female youth were more likely than male youth to report any lifetime same-sex sexual behavior (9.1% vs. 4.2%). In support of our hypothesis that non-White students would be more likely to identify as sexual minorities or as non-heterosexual, all non-White youth except for Asian youth were more likely to report a non-heterosexual identity than White youth within the pooled 2005–2015 YRBS dataset. Interestingly, Asian males and females were less likely to report a sexual minority identity, but more likely to report an unsure identity than their sexmatched White counterparts. Similar trends were found by sex and race/ethnicity for sexual minority behavior. With the exception of Asian youth, all other non-White youth were more likely to report lifetime sexual minority behavior than White youth.

Hypothesis 3a was supported for both males and females. Non-heterosexual identities significantly increased among male and female adolescents from 2005–2015; this effect was stronger for female than for male respondents. Hypothesis 3b, however, was only supported for females. Despite an overall trend in decreasing sexual behavior over time across the sample as a whole, and including female SMY, same-sex sexual behaviors significantly increased among female youth; same-sex sexual behavior also increased among male youth, but this increase was not statistically significant. We were unable to test factors that accounted for these increases in non-heterosexual identity and same-sex behavior among female youth. However, other studies indicate that changes in interpersonal and structural stigma are likely involved: the increased prevalence of non-heterosexual youth over time coincides with improvements in social attitudes toward sexual minority individuals during the same time period (Friedman et al., 2014). In other words, decreases in social stigma may contribute to youth’s willingness/comfort in reporting a non-heterosexual identity and/or same-sex behaviors, and therefore to increased reporting of non-heterosexual sexual identities and/or same-sex behaviors in research (Robertson, Tran, Lewark, & Epstein, 2017).

Our study had both strengths and limitations. Few studies have explored whether the prevalence of various dimensions of sexual orientation differ based on sex and race/ethnicity nor have they assessed change over time. To our knowledge, this is the first analysis that assesses not only the prevalence of sexual identity and behavior, as well as their intersections among high school aged youth, but also assesses trends in sexual identity and behavior over time using a pooled national sample. Due to the large sample size of the dataset, we were also able to assess racial/ethnic differences in sexual identity and behavior combinations across all racial/ethnic groups studied and stratified by sex. However, some groups had a small sample size, which limited the statistical testing that could be used to analyze racial/ethnic differences. Further, while it is important that the National YRBS added sexual identity and behavior in 2015, its study design does not include the third dimension of sexual orientation–namely sexual attraction (Patterson et al., 2017). Future survey years could benefit by including this construct in order to obtain a more complete picture of adolescent sexual orientation. Additionally, the design of YRBS did not allow for assessment of asexual orientation, either by attraction or identity. Moreover, YRBS did not measure gender identity before 2017, which makes the results from this study difficult to compare to recent LGBT population estimates (Lunn et al., 2017; Gates, 2017) which typically consider gender identity in concert with sex assigned at birth. While sexual orientation is typically measured via self-report, some researchers have examined physiological responses to sexual stimuli in an effort to understand the physiological manifestations of sexuality (e.g., Chivers, 2017). Although the design of YRBS presents significant barriers to the use of physiological measurement, the integration of self-report and physiological measurement in future studies has the potential to further advance our understanding of sexuality.

Another consideration is the anonymous, self-administered format of the YRBS and resulting inability to verify if respondents were answering truthfully; this limitation is ubiquitous in survey-based research, and the magnitude of its effect on the prevalence of reported sexual minority identity or behavior is a topic of ongoing debate (Katz-Wise, Calzo, Li, & Pollitt, 2015; Robinson-Cimpian, 2014; Savin-Williams & Joyner, 2014). Although this study assessed trends in sexual minority identity and behavior over time, the students completing YRBS surveys were not the same across years; therefore, unlike ongoing cohort studies such as Add Health or GUTS, we cannot draw within-person inferences. There is some evidence that within-person changes in sexual orientation over time are associated with depression (Everett, 2015) and substance use (Needham, 2012; Ott et al., 2013). As such, it will be important to continue to examine within person trajectories of sexual orientation and their implications for health and wellbeing. However, our data provide a representation of national trends–in other words, our data are more generalizable than a longitudinal cohort study and have important implications for the study and practice of sexual minority health nationwide.

National Trends

Trends over time indicate that, while sexual minority behavior is increasing, particularly among sexual minority youth, the percentage of sexual minority youth who are reporting no sex is increasing as well. These numbers, in concert with a decrease in reported heterosexual identity, may indicate that more sexual minority youth (and female youth in particular) are identifying as gay, lesbian, or bisexual without sexual experience than before.

Unlike many studies of adults, our analyses of combinations of sexual identity and behavior was inclusive of youth who identified as not sure of their sexual identity and who had not yet had sex. Consistent with prior reports indicating that assessment of multiple dimensions of sexual orientation can yield novel and important information (Bostwick et al., 2010; Lindley et al., 2012; Patterson et al., 2017), analyses of combinations of sexual identity and behavior in our sample revealed several novel findings–first, that LGB youth were less likely to report “no sex” compared to heterosexual and not sure youth. Second, same-sex sexual behavior increased among all non-heterosexual female youth as well as among gay male youth. Third, within sexual minority youth sub-populations who had engaged in same-sex sexual behaviors, both gay males and lesbian females were more likely to report only same-sex partners than both same-and different-sex partners. In contrast, these trends were reversed among bisexual male and female individuals.

Identity Development

Past demographic analyses of sexual orientation among U.S. youth have found significantly higher rates of uncertainty and lower rates of sexual minority identity in comparison to our sample (Remafedi, Resnick, Blum, & Harris, 1992). It is possible that changing social attitudes regarding non-heterosexual identities and behaviors may affect the ways in which non-heterosexual youth approach the process of identity formation. Decreases in social stigma have been associated with an increased likelihood of disclosure of sexual minority status within surveys. Decreases in stigma may also have reduced social expectations for compulsory heterosexuality; this phenomenon may have led fewer youth to select “heterosexual” as a “default response” within YRBS (Miller & Ryan, 2011). More research should examine trends over time in how youth approach sexual identity formation through changing cultural contexts. Individual and environmental differences in approaches to identity formation may be particularly relevant considering the prevalence of youth who were not sure of their identity despite engaging in different types of sexual behavior, as well as youth who were sure of their identities despite not having engaged in any lifetime sexual behavior.

Another interesting finding in our analyses was that, while only a small percentage of heterosexual youth reported engaging in any same-sex behavior (3.3% of females and 1.6% of males), due to the larger number of heterosexual youth overall, heterosexual youth comprised 40.7% of female and 45.7% of male youth reporting any lifetime same-sex sexual behaviors. Analogously, sizeable percentages (7.8% of female and 3.4% of male participants) who reported only different-sex partners also reported a non-heterosexual identity. The fact that 3.3% of high school students indicated that they were not sure of their sexual identity highlights the developmental nature of sexual identity (Remafedi et al., 1992). Studies using the national YRBS dataset, which was not used in our analyses, report similar rates of “not sure” reporting (3.2%) nationwide (Caputi, Smith, & Ayers, 2017).

Individuals who indicated a not sure sexual identity, while significantly more likely to report engaging in same-sex behaviors than heterosexual individuals, were only half as likely to engage in any same-sex behavior as LGB students. This illustrates the critical importance of considering SMY and NHY as disparate categories, as not sure youth demonstrate patterns of sexual behavior distinct from both heterosexual and LGB youth. When not sure students reported engaging in same-sex behaviors, similar to bisexual youth, they were more likely to report both same-and-different-sex partners than only same-sex partners.

Policy Implications

Our results demonstrate that the prevalence of youth who identify as non-heterosexual and who report same-sex behaviors is growing over time, particularly among female youth. Averaging across the 10 years of data available, 1 in 6 high school aged females and 1 in 8 high school aged males reported a non-heterosexual identity and/or having engaged in same-sex behavior. These findings indicate that nearly two out of three high school aged non-heterosexual youth are female. Additionally, with the exception of Asian youth, a greater percentage of non-White youth identified as non-heterosexual and/or engaged in same-sex behavior than White youth.

These findings reveal that, among non-heterosexual youth, female and non-White youth represent a greater proportion of the non-heterosexual population than their White and/or male counterparts. Funding for LGB research, however, disproportionately supports studies focused on the health of sexual minority men (Coulter, Kenst, Bowen, & Scout, 2014), especially those at risk for or living with HIV. While there is no doubt that such populations deserve this attention and funding, it is also true that an increasing number of studies have shown that sexual minority women often experience greater health disparities than sexual minority men across many other dimensions of health, including obesity, mental health problems, and alcohol abuse (Gonzales, Przedworski, & Henning-Smith, 2016; Hsieh & Ruther, 2016; Ward, Dahlhamer, Galinsky, & Joestl, 2014; Ward, Joestl, Galinsky, & Dahlhamer, 2015). On top of this, the present study demonstrates that sexual minority youth, especially female youth, are a growing part of the national population with substantial diversity. However, the vast majority of federal dollars allocated to SGM research are directed towards HIV/AIDS, which primarily affects populations such as men who have sex with men (MSM) (National Institutes of Health Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office, 2018). More work should focus on the health needs of sexual minority women, particularly non-White sexual minority women, and funding agencies should consider expanding available capital to address their unique health needs. Additional research should also aim to explore the drivers of sexual identity formation among youth and whether or not these are influenced by cultural context. Finally, health researchers, advocates, and policy makers must consider and address the national implications of increasing numbers of U.S. youth who report a sexual minority identity and/or non-heterosexual behavior.

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA024409)

The authors would like to acknowledge the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for their role in developing the YRBSS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

In the 2007 survey, Delaware changed option 2 from “Gay or lesbian” to “Homosexual (gay or lesbian).”

In the 2005 survey, Boston and Massachusetts asked “During your life, the person(s) with whom you have had sexual contact is (are)” and the response options were “I have not had sexual contact with anyone,” “Female(s),” “Male(s),” or “Female(s) and male(s).” In the 2005 survey, Maine asked “The person(s) with whom you have had sexual contact during your life is (are)” and the response options were “I have never had sexual contact,” “Female,” “Male,” or “Male and female.”

REFERENCES

- Bostwick WB, Boyd CJ, Hughes TL, & McCabe SE (2010). Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 100(3), 468–475. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2008.152942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Meyer I, Aranda F, Russell S, Hughes T, Birkett M, & Mustanski B (2014). Mental health and suicidality among racially/ethnically diverse sexual minority youths. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), 1129–1136. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Kann L, Shanklin S, Kinchen S, Eaton DK, Hawkins J, & Flint KH (2013). Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system—2013. MMWR Recommendations and Reports, 62(1), 1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputi TL, Smith D, & Ayers JW (2017). Suicide risk behaviors among sexual minority adolescents in the United States, 2015. Journal of the American Medical Association, 318(23), 2349–2351. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). 2015 YRBS Data User’s Guide. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2015/2015_yrbs-data-users-guide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Mosher WD, Copen C, & Sionean C (2011). Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States: Data from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports (36), 1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivers ML (2017). The specificity of women’s sexual response and its relationship with sexual orientations: A review and ten hypotheses. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(5), 1161–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copen CE, Chandra A, & Febo-Vazquez I (2016). Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual orientation among adults aged 18–44 in the United States: Data from the 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Reports (88), 1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Rosario M, Birkett MA, Newcomb ME, Buchting FO, & Matthews AK (2014). Sexual orientation disparities in adolescent cigarette smoking: Intersections with race/ethnicity, gender, and age. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), 1137–1147. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter RW, Kenst KS, Bowen DJ, & Scout. (2014). Research funded by the National Institutes of Health on the health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), e105–112. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan DT, & Hatzenbuehler ML (2014). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender hate crimes and suicidality among a population-based sample of sexual-minority adolescents in Boston. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 272–278. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esser MB, Clayton H, Demissie Z, Kanny D, & Brewer RD (2017). Current and binge drinking among high school students—United States, 1991–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(18), 474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett B (2015). Sexual orientation identity change and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 56(1), 37–58. doi: 10.1177/0022146514568349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett BG, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Hughes TL (2016). The impact of civil union legislation on minority stress, depression, and hazardous drinking in a diverse sample of sexual-minority women: A quasi-natural experiment. Social Science & Medicine, 169, 180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett BG, Schnarrs PW, Rosario M, Garofalo R, & Mustanski B (2014). Sexual orientation disparities in sexually transmitted infection risk behaviors and risk determinants among sexually active adolescent males: Results from a school-based sample. American Journal of Public Health, 104(6), 1107–1112. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley MM, Stephens DS, Harvey RC, Sikes RK, & Wenger JD (1992). Incidence and clinical characteristics of invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease in adults. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 165(Supplement_1), S42–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer GW, Bucholz KK, Flick LH, Burroughs TE, & Bowen DJ (2013). CVD risk among men participating in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2001 to 2010: Differences by sexual minority status. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67(9), 772–778. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-202658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MR, Dodge B, Schick V, Herbenick D, Hubach R, Bowling J, … Reece M (2014). From bias to bisexual health disparities: Attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. LGBT Health, 1(4), 309–318. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates GJ (2011). How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender? Retrieved from The Williams Institute: http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Gates-How-Many-People-LGBT-Apr-2011.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gates GJ (2017). In US, more adults identifying as LGBT. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/201731/lgbt-identification-rises.aspx

- Gonzales G, Przedworski J, & Henning-Smith C (2016). Comparison of health and health risk factors between lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults and heterosexual adults in the United States: Results from the National Health Interview Survey. Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine, 176(9), 1344–1351. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, O’Cleirigh C, Grasso C, Mayer K, Safren S, & Bradford J (2012). Effect of same-sex marriage saws on health care use and expenditures in sexual minority men: A quasi-natural experiment. American Journal of Public Health, 102(2), 285–291. doi: 10.2105/Ajph.2011.300382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, & Link BG (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 813–821. doi: 10.2105/Ajph.2012.301069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms JL, & Waters AM (2016). Attitudes toward bisexual men and women. Journal of Bisexuality, 16(4), 454–467. doi: 10.1080/15299716.2016.1242104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM (2002). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. Journal of Sex Research, 39(4), 264–274. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, & McLemore KA (2013). Sexual prejudice. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 309–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh N, & Ruther M (2016). Sexual minority health and health risk factors: Intersection effects of gender, race, and sexual identity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 50(6), 746–755. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu YQ, Xu YS, & Tornello SL (2016). Stability of self-reported same-sex and both-sex attraction from adolescence to young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(3), 651–659. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0541-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington (DC). [Google Scholar]

- Johns MM, Zimmerman M, & Bauermeister JA (2013). Sexual attraction, sexual identity, and psychosocial wellbeing in a national sample of young women during emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(1), 82–95. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9795-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, … Zaza S (2016a). Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in Grades 9–12--United States and Selected Sites, 2015. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 65(9), 1–202. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, … Zaza S (2016b). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance--United States, 2015. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 65(6), 1–174. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6506a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, Kinchen S, Chyen D, Harris WA, & Wechsler H (2011). Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-risk behaviors among students in grades 9–12--Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance, selected sites, United States, 2001–2009. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 60(7), 1–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL, Calzo JP, Li G, & Pollitt A (2015). Same data, different perspectives: What is at stake? Response to Savin-Williams and Joyner (2014a) [Letter to the Editor]. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(1), 15–19. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0434-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindley LL, Walsemann KM, & Carter JW (2012). The association of sexual orientation measures with young adults’ health-related outcomes. American Journal of Public Health, 102(6), 1177–1185. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn MR, Obedin-Maliver J, & Bibbins-Domingo K (2017). Estimating the prevalence of sexual minority adolescents. Journal of the American Medical Association, 317(16), 1691–1692. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle MC, De Luca SM, & Blosnich JR (2014). The influence of intersecting identities on self-harm, suicidal behaviors, and depression among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44(4), 384–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dermody SS, Cheong J, Burton CM, Friedman MS, Aranda F, & Hughes TL (2013). Trajectories of depressive symptoms and suicidality among heterosexual and sexual minority youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(8), 1243–1256. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9970-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K, Ryan MJ (2011). Design, development and testing of the NHIS Sexual Identity Question. Questionnaire Design Research Laboratory, Office of Research Methodology, National Center for Health Statistics; Retrieved from https://wwwn.cdc.gov/QBANK/report/Miller_NCHS_2011_NHIS%20Sexual%20Identity.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Birkett M, Greene GJ, Rosario M, Bostwick W, & Everett BG (2014). The association between sexual orientation identity and behavior across race/ethnicity, sex, and age in a probability sample of high school students. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 237–244. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2013.301451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office. (2018). Sexual and Gender Minority Research Portfolio Analysis, FY 2016. Retrieved from https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/SGMRO_2016_Portfolio_Analysis_Final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Needham BL (2012). Sexual attraction and trajectories of mental health and substance use during the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(2), 179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott MQ, Wypij D, Corliss HL, Rosario M, Reisner SL, Gordon AR, & Austin SB (2013). Repeated changes in reported sexual orientation identity linked to substance use behaviors in youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52(4), 465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JG, Jabson JM, & Bowen DJ (2017). Measuring sexual and gender minority populations in health surveillance. LGBT Health, 4(2), 82–105. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penman-Aguilar A, Bouye K, & Liburd L (2016). Background and rationale. MMWR Supplement, 65(1), 2–3. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6501a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe G, & Svedin CG (2013). Operationalization of three dimensions of sexual orientation in a national survey of late adolescents. Journal of Sex Research, 50(8), 727–738. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.713147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remafedi G, Resnick M, Blum R, & Harris L (1992). Demography of sexual orientation in adolescents. Pediatrics, 89(4 Pt 2), 714–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson RE, Tran FW, Lewark LN, & Epstein R (2017). Estimates of non-heterosexual prevalence: The roles of anonymity and privacy in survey methodology. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(4), 1069–1084. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-1044-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-Cimpian JP (2014). Inaccurate estimation of disparities due to mischievous responders: Several suggestions to assess conclusions. Educational Researcher, 43(4), 171–185. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, & Joyner K (2014). The dubious assessment of gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents of Add Health. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(3), 413–422. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0219-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Joyner K, & Rieger G (2012). Prevalence and stability of self-reported sexual orientation identity during young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(1), 103–110. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9913-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, & Ream GL (2007). Prevalence and stability of sexual orientation components during adolescence and young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(3), 385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9088-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Walker T, & Figueroa A (2017). CDC-funded HIV testing, HIV positivity, and linkage to HIV medical care in non-health care settings among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) in the United States. AIDS Care, 29(7), 823–827. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1271104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau R, & Yan T (2007). Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin, 133(5), 859–883. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troiden RR (1988). Homosexual identity development. Journal of Adolescent Health Care, 9(2), 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Sherman RA, & Wells BE (2015). Changes in American adults’ sexual behavior and attitudes, 1972–2012. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(8), 2273–2285.doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0540-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward BW, Dahlhamer JM, Galinsky AM, & Joestl SS (2014). Sexual orientation and health among US adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr077.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]