Abstract

TLRs are a class of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect invading microbes by recognizing pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Upon PAMP engagement, TLRs activate a signaling cascade that leads to the production of inflammatory mediators. The localization of TLRs, either on the plasma membrane or in the endolysosomal compartment, has been considered to be a fundamental aspect to determine to which ligands the receptors bind, and which transduction pathways are induced. However, new observations have challenged this view by identifying complex trafficking events that occur upon TLR‐ligand binding. These findings have highlighted the central role that endocytosis and receptor trafficking play in the regulation of the innate immune response. Here, we review the TLR4 and TLR9 transduction pathways and the importance of their different subcellular localization during the inflammatory response. Finally, we discuss the implications of TLR9 subcellular localization in autoimmunity.

Keywords: innate immunity, autoimmunity, intracellular signaling, receptors trafficking, inflammation

Review on the importance of TLR4 and TLR9 dynamic subcellular localization in the inflammatory responses.

Abbreviations

- ALRs

AIM2‐like receptors

- AP‐1

activator protein 1

- BAD‐LAMP

brain and DC‐associated LAMP‐like molecule

- BLOC

biogenesis of lysosome‐related organelles complex

- BMDC

bone marrow‐derived dendritic cells

- BMDM

bone marrow‐derived macrophages

- cDC

conventional dendritic cells

- CIA

collagen‐induced arthritis

- CLRs

C‐type lectin receptors

- COPII

coat‐protein complex II

- DAP12

DNAX‐activating protein of 12 kDa

- DCs

dendritic cells

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FHOD1

forming‐homology‐domain‐containing protein 1

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- HMGB

high‐mobility group box

- HPS

Hermansky‐Pudlack syndrome

- IKK

IκB kinase

- IP3Rs

inositol trisphosphate receptors

- IRAKs

IL‐1 receptor‐associated kinases

- IRAP

insulin‐responsive aminopeptidase

- IRF

IFN‐regulatory factor

- LAMPs

lysosome‐associated membrane proteins

- LPB

LPS‐binding protein

- LROs

lysosome‐related organelles

- MD‐2

myeloid‐differentiation protein 2

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NLRs

NOD‐like receptors

- OPN

osteopontin

- PAMPs

pathogen‐associated molecular patterns

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- pDCs

plasmacytoid DCs

- PI3K

phosphoinositol 3‐OH kinase

- PIKfive

phosphoinositide 3‐phosphate 5‐kinase

- PIs

phosphoinositides

- PPRs

pattern‐recognition receptors

- PRAT4A

protein associated with TLR4

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- RIG

retinoic acid‐inducible gene

- RIPK1

receptor‐interacting serine/threonine kinase 1

- RLRs

RIG‐I‐like receptors

- Slc15a4

solute‐carrier protein superfamily member

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- SS

Sjögren's syndrome

- SSc

systemic sclerosis

- Syk

spleen tyrosine kinase

- TAB

TAK‐binding protein

- TAK

TGF‐β‐activated kinase

- TANK

TRAF family member‐associated NF‐κB activator

- TBK

TANK‐binding kinase‐1

- TIR

Toll/IL‐1 receptor

- TIRAP

TIR‐containing adaptor protein

- TRADD

TNF receptor‐1‐associated death‐domain protein

- TRAF

TNF receptor‐associated factors

- TRAM

TRIF‐related adaptor molecule

- TRIF

TIR‐domain‐containing adaptor inducing IFN‐β

- TRPM7

transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 7

- UNC93B1

unc‐93 homolog B1

- UPEC

uropathogenic Escherichia Coli

- VAMPs

vesicle‐associated membrane proteins

1. INTRODUCTION

The innate immune system uses pattern‐recognition receptors (PRRs) to sense the presence of invading microbes. PRRs recognize endogenous and exogenous ligands, including pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are conserved chemical motifs expressed by microorganisms. According to the model proposed by Janeway, the recognition of PAMPs by PRRs is the primary strategy for self‐ versus nonself‐discrimination.1 Antigen‐presenting cells express high levels of PRRs that, upon ligand binding, transduce an intracellular signal, leading to the production of several factors involved in the initiation of the immune response. Ultimately, these events induce the activation of adaptive immunity and the formation of memory cells.2

Dysregulation of PRR‐mediated responses may compromise immunologic self‐tolerance. For example, aberrant activation triggered by host‐derived nucleic acids causes autoimmune disorders, such as Sjögren's syndrome (SS),3 systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE),4 multiple sclerosis (MS),5 systemic sclerosis (SSc),6 rheumatoid arthritis (RA),7 and psoriasis.8

PRRs are classified into 5 families: TLRs, C‐type lectin receptors (CTLs), NOD‐like receptors (NLRs), retinoic acid‐inducible gene (RIG)‐I‐like receptors (RLRs), and AIM2‐like receptors (ALRs). TLRs are the best‐characterized PPRs and are essential modulators of the innate immune response, as they survey both the intracellular and extracellular space.9 The widespread cellular localization of TLRs confirms their central role in recognizing potential threats and, indeed, some receptors are able to initiate signaling cascades from either the plasma membrane or endosomes.

Here, we provide an overview of the transduction pathways triggered by intracellular TLRs, with a particular focus on the signaling cascades elicited by TLR9 and the intracellular pathways of TLR4. We also discuss how TLR9 signaling may be involved in autoimmunity.

2. INTRACELLULAR TLRS

TLRs are glycoproteins that consist of 3 domains: a transmembrane domain, an amino‐terminal ectodomain, and a cytoplasmic carboxy‐terminal Toll IL1‐1R homology (TIR) domain.10, 11 To activate downstream signaling pathways, TLRs recruit a variety of adaptor proteins, including the TIR‐containing adaptor protein (TIRAP), MyD88, the TIR domain‐containing adaptor inducing IFN‐β (TRIF), and the TRIF‐related adaptor molecule (TRAM).12 Intracellular TLRs (TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9, TLR11, TLR12, and TLR13) are expressed in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), endosomes, multivesicular bodies, and lysosomes; their localization to endosomes and lysosomes, where self‐DNA is rarely present, is important to prevent autoimmunity and inappropriate immune responses. Intracellular TLRs recognize either nucleic acids (TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9, and TLR13) or microbial components (TLR11‐TLR12), both derived from the hydrolytic degradation of microorganisms in the endolysosomal compartment.13

The ligand of TLR3 is double‐stranded RNA, such as that of HSV‐1, which causes encephalitis,14 small interfering RNAs,15 and self RNAs from damaged cells (e.g., RNA damaged by ultraviolet B irradiation).16 Similarly, TLR7 in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) recognizes viral single‐stranded RNA, whereas it binds to the RNA of streptococcus B bacteria in conventional dendritic cells (cDCs).17 In addition, human TLR8 recognizes viral and bacterial RNA and is preferentially activated by ssRNA rich in AU.18, 19 On the other hand, TLR9 primarily binds unmethylated CpG DNA motifs, which are common in bacterial and viral DNA; it can also recognize hemozoin, an iron‐porphyrin‐proteinoid complex derived from the degradation of hemoglobin by malaria parasites.20 Parroche et al., however, proposed that hemozoin is itself immunologically inert and that its inflammatory activity is due to the presence of parasite DNA in the hemozoin crystal.21 Another nucleic acid‐sensing TLR, TLR13, senses bacterial 23S rRNA22 and vesicular stomatitis virus.23

Among the TLRs that recognize microbial components, TLR11 binds to an unknown proteinaceous component of uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC)24 and a profilin‐like molecule derived from Toxoplasma gondii.25 TLR12 shares many similarities with TLR11: they both recognize Toxoplasma gondii, can form homo‐ and heterodimers, and can cooperate to recognize their ligands in cDCs and macrophages.26

Upon ligand binding, intracellular TLRs initiate various signaling pathways. TLR3 induces the expression of inflammatory cytokines and type I IFNs by activating TRIF‐dependent signaling through a high‐affinity interaction between its TIR domain and the TRIF domain. Notably, this binding is completely TRAM independent.27 On the other hand, TLR7 and TLR9 activate the transcription factor IRF7 through the MyD88‐dependent signaling pathway.28, 29 TLR3, 7, and 9 become active and trigger downstream signaling following internalization of their ectodomains into endosomes, where they undergo proteolytic cleavage. This process requires endosomal proteases and is an additional regulatory mechanism that avoids recognition of self‐molecules by strengthening the compartmentalization of intracellular TLRs.

The trafficking of intracellular TLRs from the ER to endolysosomes must be strictly controlled to ensure correct signaling cascades. Indeed, intracellular TLRs require the multimembrane protein unc‐93 homolog B1 (UNC93B1) to exit the ER and enter the secretory pathway.30 UNC93B1 controls the packaging of TLRs into coat protein complex II (COPII) vesicles, which then shuttle the TLRs from the ER to the Golgi.31 The role that UNC93B1 plays in the trafficking of TLRs is different for each receptor.32 Several chaperone proteins, such as glycoprotein 96 and the protein associated with TLR4 A (PRAT4A), also interact with TLRs and are important for shuttling from the ER.33, 34 Notably, nucleic acids may enter the cell through different types of endosomes and the specific site of signaling defines the final outcome of the pathway.

3. TLR4

Among all PRRs, TLR4 is the best characterized, as it was the first to be discovered in mammalian innate immune cells.35 Despite TLR4 mainly residing in the plasma membrane, it can also be considered as an intracellular TLR, because it can be internalized and stimulate intracellular pathways.36 Moreover, although still controversial, it has been proposed that TLR2 also activates NF‐kB from endosomes in human monocytes37 and induces the production of type I IFN in mouse Ly6Chigh inflammatory monocytes in response to viral ligands.38 Thus, the endocytic machinery assumes a pivotal role in the regulation of pathways elicited by TLR4 and perhaps TLR2.

The main ligand of TLR4 is LPS, the major component of the outer membrane of Gram‐negative bacteria. LPS is composed of lipids and carbohydrates, with a high level of structural complexity, and consists of 3 different components: the O antigen, an O‐polysaccharide chain of variable length; the core oligosaccharide; and lipid A, which contributes to most of the immunostimulatory activity of the molecule.39 The O antigen is specific for each bacterial strain and affects colony morphology; microbial variants with full‐length O‐polysaccharide chains form smooth colonies, whereas those lacking or carrying reduced chains form rough colonies.40

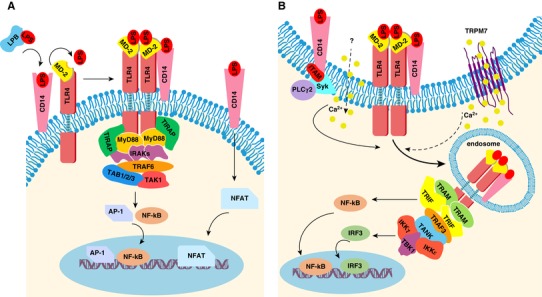

Despite TLR4 being the central mediator of innate and adaptive immune responses induced by LPS, endotoxin recognition also requires other surface molecules. Indeed, TLR4 forms the LPS multi‐receptor complex with LPS binding protein (LPB), glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)‐anchored protein CD14, and myeloid differentiation 2 (MD‐2).12 LPB is a soluble protein that binds large LPS aggregates on the bacterial cell wall,41 leading to LPS disaggregation and the presentation of monomers to CD14.42 Upon LPS stimulation, CD14 promotes re‐localization of the TLR4‐MD‐2 complex to lipid rafts, which are enriched in PIP2 (phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐bisphosphate).43, 44 At this point, TLR4 dimerizes and can initiate signal transduction from both the plasma membrane and the endosome; on the plasma membrane, PIP2 binds to TIRAP and mediates the activation of the Myd88 pathway45 (Fig. 1A), whereas TLR4 activates the TRAM‐TRIF pathway upon internalization into the endosome (Fig. 1B).36 The coordinated actions of all the proteins of the LPS multi‐receptor complex, combined with the ability of CD14 and MD‐2 to sense and bind LPS, even at picomolar concentrations, ensures the detection of bacteria with high sensitivity.46

Figure 1.

TLR4 plasma membrane and endosome signaling. A) LPB protein extracts LPS from the bacterial cell wall and transfers it to CD14. In the presence of LPS, CD14 allows the translocation of the TLR4‐MD‐2 complex to lipid rafts, where it dimerizes. Then the formation of the “myddosome” complex (containing TIRAP, MyD88, and IRAKs) occurs. IRAKs recruit TRAF6, which interacts with TAB1/2/3 and TAK1 for the activation of NF‐κB and AP‐1. CD14 binds directly to LPS and induces a signal that leads to the activation of NFAT transcription factors. B) The LPS receptor complex is internalized through a CD14‐dependent mechanism, involving ITAM‐bearing molecules, Syk tyrosine kinase, and PLCγ2. Calcium mobilization from the extracellular space via TRPM7 is also required, at least in part. In the endosome, TRAM‐TRIF adaptor molecules bind to TRAF3, which interacts with TANK to recruit IKKs and TBK1, which activate IRF3

Recent data have shown that not only TLR4 but also CD14 can sense LPS. Indeed, the surface molecule CD14 alone is able to activate a signaling cascade in response to LPS, leading to activation of the NFAT in DCs (Fig. 1A).47 Moreover, several studies have demonstrated that intracellular LPS activates the formation of a caspase‐11‐dependent noncanonic inflammasome.48, 49, 50 More recently, Shi et al. have identified the receptors for intracellular LPS by showing that caspase‐11 in mice and caspase‐4 and ‐5 in humans directly bind LPS.51

4. TLR4 PLASMA MEMBRANE AND ENDOSOMAL SIGNALING

TLR4 activates 2 signaling pathways. From the plasma membrane, the receptor induces the TIRAP‐MyD88 pathway, which activates NF‐κB and AP‐1. From the endosome, TLR4 initiates the TRAM‐TRIF pathway, leading to the activation of IRF3, the production of type I IFNs, and a late wave of NF‐κB activation.36

As recently reviewed by Brubaker et al.,12 upon TLR4 activation, TIRAP facilitates the interaction of MyD88 with TLR4 via its TIR domain, leading to the formation of the so‐called “myddosome,” a large molecular platform composed of MyD88, TIRAP, and IRAK proteins.52, 53 IRAK4 activates both IRAK1 and IRAK2, which, in turn, recruit TRAF6. TRAF6 interacts with TAB1, TAB2, TAB3, and TAK1, regulating the activation of NF‐κB and AP‐1 via IKKs and MAPK, respectively (Fig. 1A).12

After the first wave of NF‐κB and AP‐1 activation, the bipartite sorting signal of the adaptor protein TRAM controls trafficking of the entire LPS receptor complex to the endosomal compartment.36 During internalization, the TIRAP‐MyD88 complex is released from the invaginating plasma membrane, allowing TRAM‐TRIF to engage the TIR domain of TLR4.36 The first step for TRIF‐dependent IRF3 activation entails the recruitment of TRAF3 to TRIF. In turn, TRAF3, by interacting with TANK, recruits TBK1 and IKK‐ε; this complex then activates IRF3 and induces the production of type I IFNs (Fig. 1B).54, 55 It has become clear over the last 10 yr that both plasma‐membrane and endosome signaling of TLR4 are required for the full response to LPS, highlighting the importance of both the internalization process and the molecules involved. In addition to the 2 main signaling pathways of TLR4, TLR4 intracellular signaling boosts micropinocytosis and antigen presentation56, 57 and, recently, it has also been shown to be involved in the recognition and uptake of apoptotic cells.58

5. ENDOCYTOSIS OF TLR4

After the first wave of NF‐κB activation, the LPS receptor complex is internalized and redirected to the endosome. A series of studies have underlined the central role of CD14 in this process and have demonstrated that the production of type I IFN depends on CD14, highlighting the essential role of CD14 in the induction of the type I IFN‐mediated response against Gram‐negative bacteria. In particular, it has been shown that the TLR4‐CD14‐TRAM‐TRIF pathway is required for the induction of IFN‐γ production in NK cells during Gram‐negative bacterial infections.59 Jiang et al. demonstrated that CD14 is absolutely required for both activation of the TRAM‐TRIF pathway and the production of type I IFN in response to smooth and rough LPS, despite its being dispensable for the detection of high doses of LPS by the complex.60

Two studies have described how CD14 orchestrates endosomal re‐localization of the LPS complex: CD14‐dependent TLR4 endocytosis, called “inflammatory endocytosis,” is mediated by the activation of the tyrosine kinase Syk and phospholipase Cγ2, of which the activation is regulated by ITAM and the adaptors DAP12 and FcεRγ (Fig. 1B).56, 61

A recent study has proposed that the chanzyme TRPM7 (transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily M, member 7) is involved in LPS‐induced TLR4 endocytosis in macrophages by mediating calcium influx (Fig. 1B).59 Indeed, the authors showed that both genetic deletion of trpm7 and pharmacologic inhibition of the channel abolish, at least partially, the calcium influx in response to LPS, preventing TLR4 internalization.62 However, TRPM7 may control the recycling of TLR4 rather than its internalization.63 Further research is needed to clarify the mechanism by which TRPM7 regulates TLR4 endocytosis.

Recently, a study has clarified how TLR4 is selected as cargo for endocytosis.64 Starting from the observation that the endocytosis of CD14 occurs constitutively in resting cells, the authors hypothesized that the tail of TLR4 is dispensable for the initiation of TLR4 internalization. As a TLR4 mutant lacking intracellular domain did not abrogate the process, the authors inferred that the cargo‐selection agent resided in the extracellular portion and hypothesized the involvement of the interaction between TLR4 and MD‐2. Indeed, they discovered that both direct binding of MD‐2 to the TLR4 ectodomain and MD‐2‐dependent TLR4 dimerization promote TLR4 endocytosis.61 Thus, MD‐2 plays a key role in TLR4 signaling by coordinating both signal transduction and endocytosis.

Depending on the cell type, the endocytosis of TLR4 involves different players. For example, a specific role for CD11b in promoting the endocytosis of TLR4 has been found in DCs but not in macrophages, as the absence of the integrin affects the process only in DCs.65 Notably, CD11b is required for the correct internalization of TLR4 only in cells with low levels of CD14.69 Indeed, the treatment of CD11b‐deficient DCs with CpG DNA leads to higher levels of expression of CD14 that compensate the TLR4 internalization defect of the cells. However, CpG treatment does not rectify the defect that the cells have in the TRIF/IRF3 pathway, showing that CD11b plays another role in addition to the modulation of TLR4 trafficking.65

The endocytosis of TLR4 is negatively regulated by the metallopeptidase CD13. CD13 is up‐regulated in the presence of LPS and inhibits TRIF signaling in DCs, as shown by higher levels of TLR internalization in CD13‐deficient cells.66 How CD13 negatively regulates TLR4 trafficking is not yet clear, but neither the inhibition of MD‐2 nor the inhibition of CD14 seem to be involved.66

Perkins et al. described a new negative‐feedback loop driven by the PGE2‐EP4 axis that specifically inhibits TLR4‐mediated TRIF‐dependent type I IFN production by regulating TLR4 trafficking. Specifically, PGE2 is rapidly secreted and acts in an autocrine‐paracrine regulatory loop in response to bacterial LPS.67

Finally, it is worth noting that pathogenic and commensal bacteria prevent TLR4 endocytosis by producing dephosphorylated LPS to evade detection and CD14‐mediated transport to the endosome.64

6. IT IS ALL ABOUT TRAFFICKING: THE PATH OF TLR9 INTO THE ENDOLYSOSOMAL SYSTEM

The complexity of the endosomal system fine‐tunes the immune response by ensuring the correct compartmentalization of intracellular TLRs and their ligands.

In resting cells, TLR9 is localized to the ER30, 68, 69 and requires endosomal shuttling to initiate signal transduction. TLR9 engagement can culminate in 2 outcomes: the activation of IRF in the IRF‐signaling endosomes (IRF‐SE) and the activation of NF‐κB in the NF‐κB‐signaling endosomes (NF‐κB‐SE). Thus, the TLR9 signaling pathway has been defined as “bifurcated.”70 Specifically, the trafficking of TLR9 and its ligand to the IRF‐SE leads to the production of type I IFN, whereas localization to the NF‐κB‐SE induces the expression of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, via IRF and NF‐κB, respectively (see Fig. 2).

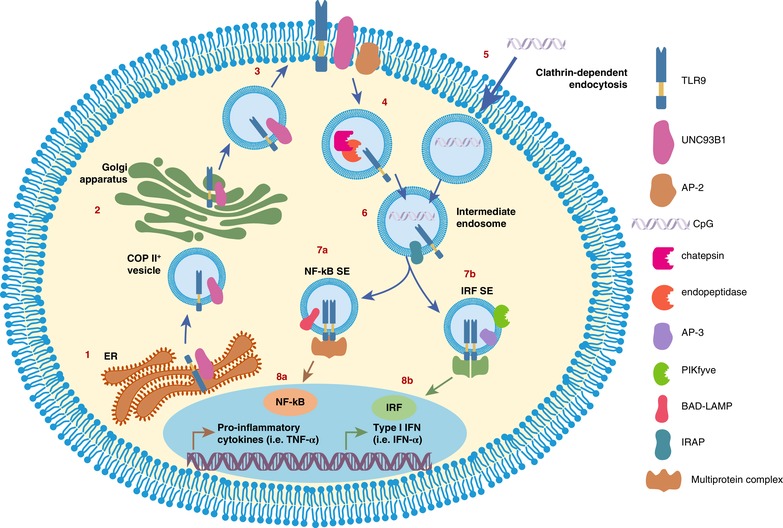

Figure 2.

TLR9 intracellular trafficking and pathway. At steady state, TLR9 co‐localizes to the ER with UNC93B1 (1). TLR9 follows the secretory pathway through the Golgi (2) to reach the plasma membrane (3) via COPII+ vesicles. TLR9 is endocytosed in a clathrin‐dependent manner via AP‐2 to enter the endolysosomal system, where acidification of the endosomes allows proteolytic cleavage of TLR9 by cathepsins and endopeptidases (4). In parallel, the TLR9 ligand, CpG, is endocytosed in a clathrin‐dependent manner (5) and meets its cognate receptor (6). Here, the pathway bifurcates. IRAP+ early endosomes carry both TLR9 and CpG, and the presence of this aminopeptidase results in reduced immune activation, as IRAP interacts with actin‐nucleation factors to slow TLR9 trafficking to the late endosomes. In human pDCs, BAD‐LAMP facilitates the trafficking of TLR9 and CpG

Several checkpoints control TLR9 shuttling through vesicles and involve several membrane and adaptor proteins,70 actin‐nucleation factors, cytoskeletal remodeling proteins,71 lysosome‐ or vesicle‐associated membrane proteins (LAMPs and VAMPs),72 and folding chaperones. For example, UNC93B1 facilitates TLR9 trafficking from the ER to the Golgi32 and then controls the loading of TLR9 into COP II+ vesicles, which deliver the receptor to the plasma membrane.31 At the cell membrane, UNC93B1 recruits the adaptor protein AP‐2 via its C‐terminal YxxΦ motif and mediates clathrin‐dependent internalization of TLR9, leading to localization of the receptor to early endosomal compartments.68, 69 The early endosomes that contain TLR9 and its ligand are still poorly characterized.

The brain and DC‐associated LAMP‐like molecule (BAD‐LAMP) is a member of the lysosome‐associated membrane glycoproteins and controls, together with UNC93B1, the trafficking of TLR9.72 It is expressed by pDCs, which produce the largest amount of type I IFNs in response to viral infections.73, 74 Indeed, in human pDCs, BAD‐LAMP co‐localizes with UNC93B1 from the ER to an endosomal hybrid compartment, the IRF‐SE, which expresses both VAMP3 and LAMP2. From the IRF‐SE, BAD‐LAMP directs and promotes the trafficking of TLR9 to a LAMP1+ late endosome, the NF‐κB‐SE, leading to the production of pro‐inflammatory cytokines.72

In murine bone marrow‐derived DCs (BMDCs), the intermediate VAMP3+ endosome contains insulin‐responsive aminopeptidase (IRAP), a type II transmembrane protein. IRAP is involved in antigen processing for cross‐presentation via MHC I,75, 76, 77 but recently a new role in TLR9 trafficking has been proposed, as TLR9 and its ligand are cargo of IRAP+ intermediate endosomes.71 In IRAP+ endosomes, IRAP interacts with forming‐homology‐domain‐containing protein 4 (FHOD4), a protein that promotes actin assembly on endosomes; their interaction delays TLR9 trafficking and limits the shuttling of TLR9 to LAMP+ lysosomes by enhancing endosome retention. Accordingly, IRAP‐deficient DCs show higher levels of IRF7 and NF‐κB activation than wild‐type DCs (see Fig. 2).71

6.1. The game changer: AP‐3

The signaling cascade triggered by TLR9 depends on intracellular trafficking of the receptor. APs select the cargo in the vesicles and, specifically, AP‐3 determines whether TLR9 is addressed to IRF‐SE to promote type I IFN production.70 Indeed, AP‐3 is required for the formation of lysosome‐related organelles (LROs),78, 79 in which one of the two TLR9 signaling cascades occurs, depending on the origin of the cell.

Iwasaki et al. have proposed that TLR9 from the Golgi enters NF‐κB‐SEs (characterized by the expression of VAMP3 and PI(3,5)P2 and the lack of LAMP2 expression), where it promotes the transcription of pro‐inflammatory cytokines in murine bone marrow‐derived pDCs. In NF‐κB‐SEs, AP‐3 interacts with TLR9 and induces shuttling of the receptor to LAMP2+ LROs (IRF‐SEs), resulting in the production of type I IFN.70

Consistent with Iwasaki's model, Blasius et al. found that AP‐3 is essential for the induction of type I INF production, specifically in pDCs.78 They observed that pDCs derived from mice with mutations in AP‐3b1 (Ap3b1 pearl/pearl and Ap3b1 bullet gray/bullet gray 80) fail to produce both type I IFNs and TNF‐α upon TLR9 activation. However, the release of cytokines in cDCs isolated from the same animals was unaffected,78 confirming the intrinsic difference between pDCs and cDCs. In accordance with these results, the pDCs of Hermansky‐Pudlack syndrome (HPS) type 2 patients, with AP‐3 defects, exhibit reduced IFN‐α production upon challenge with HSV‐1.81

Conversely, Combes et al. reported that the production of type I IFNs was unaffected by silencing of AP‐3 in a human pDC cell line (CAL‐1). However, they demonstrated that the AP‐3 complex contributes to shifting endosomal compartments by promoting TLR9 and BAD‐LAMP access to late endosomes for the activation of the NF‐κB pathway.72

Finally, several studies have suggested that AP‐3 is regulated by the phosphoinositide 3‐phosphate 5‐kinase (PIKfive), a kinase that controls the status of the phosphorylated derivatives of phosphatidylinositol (PI), key components of cell membranes.82 It has been shown that PIKfive and phosphorylated PIs regulate TLR signaling by orchestrating their intracellular pathways.83, 84 Specifically, in NF‐κB endosomes, PIKive converts PI(3)P to PI(3,5)P2,85 which recruits and interacts with AP‐3.86 Thus, PIKfive ensures the correct trafficking of TLR9 and CpG to type I IFNs‐SE87 by guaranteeing both the recruitment of AP‐3 and the generation of LROs.88 Moreover, an additional role of PIKfive in pDCs has been suggested, as its inhibition suppresses both IRF7 and NF‐κB pathways in pDCs, whereas it abrogates only type I IFN production in cDCs.88 The role of AP‐3 in generating LROs thus appears to be clear, although the signaling cascade that is triggered from the LROs is still a matter of debate.

7. IT IS ALL ABOUT TRAFFICKING: CPG IS LOOKING FOR A RECEPTOR

The trafficking of TLR9 to endosomal compartments is of utmost importance for the initiation of signaling cascades (see Fig. 2). However, CpG also requires controlled shuttling to endolysosomes to encounter TLR9 and activate the pathways. Indeed, upon CpG stimulation of human DCs, the DNA undergoes rapid clathrin‐dependent and caveolin‐independent internalization into vesicles that localize in juxtanuclear areas.68 Then, TLR9 is actively shuttled to CpG‐rich compartments because of the recruitment of MyD88 in the vesicles. Two studies have also shown that CpG trafficking affects the efficiency of TLR9 signaling, as the abrogation of CpG trafficking to the LAMP+ late compartment impairs TLR9 pathways.87, 88

Some of the molecules involved in the shuttling of CpG to the endolysosomal system are discussed below.

7.1. Granulin

CpG interacts with a co‐receptor that delivers it to the endolysosomes: granulin.89, 90 Granulin coordinates CpG trafficking to TLR9‐rich vesicles, where it promotes the interaction between the ligand and the C‐terminal domain of TLR9, guaranteeing activation of the signaling cascade.89

Granulin is a cysteine‐rich protein91 involved in several biologic processes, such as wound healing,92 embryonic development, and cell growth.93, 94 Park et al. first identified granulin in RAW macrophages by mass spectrometry, as it was among the polypeptides that co‐immunoprecipitated with TLR9 in protease‐inhibited RAW macrophages.90 This study also confirmed the importance of granulin for the activation of TLR9 signaling. The addition of granulin to the macrophage culture increased TNF‐α production only upon CpG stimulation, whereas the removal of secreted granulin reduced the amount of TNF‐α released by the cells.90 Moreover, BMDMs and pDCs isolated from granulin‐deficient mice exhibit impaired TNF‐α and IL‐6 production upon CpG treatment.

Several studies have also suggested that granulin plays a role in autoimmunity. Tanaka et al. found high levels of granulin in the serum of patients with SLE95; Xiong et al. later confirmed the same result in a mouse model of SLE and linked the increased amount of granulin to an aggravation of lupus nephritis, a clinical manifestation of SLE.96, 97 Therefore, granulin appears to worsen the autoimmune status of both humans and mice. Indeed, Xiong et al. demonstrated that granulin promotes the shifting of macrophage polarization toward an M2b phenotype, leading to increased production of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF‐α, IL‐6, and IL‐1β.96 As TLR9 pathway activation in macrophages induces M1 polarizing signaling,98 it is likely that granulin‐mediated M2b polarization involves an additional receptor or an alternative mechanism. In addition, Chen et al. focused on macrophages, excluding pDCs and B cells from the scenario of activated lymphocyte‐derived DNA‐induced lupus nephritis.96 Hence, the role of granulin in autoimmunity appears to be poorly characterized, in particular regarding type I IFN production upon TLR9 engagement in pDCs. Overall, these results highlight the unclear role of granulin in both the TLR9 pathway and autoimmune diseases.

7.2. HMGB1

Another co‐factor that facilitates DNA sensing is high‐mobility group box 1 (HMGB1). HMGB1 is a multifunctional protein that resides in the nucleus and regulates chromatin structure,99, 100, 101 V(D)J recombination,102, 103 and gene transcription.104 Upon tissue damage, HMGB1 is secreted by necrotic cells,105 whereas immune cells actively release it during infections and when stimulated by inflammatory mediators.106

To date, only a few studies have investigated the role of HMGB1 in the immune response. Tian et al. showed that HMBG1 binds to bacterial and mammalian DNA, as well as CpG by treating peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with sera from SLE patients.107 The authors suggested that HMBG1 may catalyze the TLR9‐mediated response to DNA, as it enhances the stimulatory effect of CpG on pDCs by increasing the production of both IFN‐α and TNF.107 In addition, the authors demonstrated that, in pDCs, the HMGB1‐DNA complex binds to the receptor for advanced glycation end‐products (RAGE), which in turn interacts with TLR9, increasing the production of type I IFN production by pDCs via the internalization of DNA.107 The crucial role of the HMGB1‐RAGE axis in TLR9 regulation has also been confirmed by Tian et al., who treated PBMCs with sera collected from SLE patients and necrotic cell supernatants, showing that DNA complexes in the sera induced type I IFN production. This induction was abrogated by treating necrotic cells with inhibitors of HMGB1 or RAGE.107

Accordingly, Ivanov et al. demonstrated that HMGB1 binds to CpG in BMDCs and BMDMs and plays an essential role in enhancing the release of pro‐inflammatory cytokines.108 The authors showed that the augmented response was not due to increased internalization of HMGB1‐CpG, but to a more rapid interaction between TLR9 and CpG. Indeed, HMGB1 already co‐localizes with TLR9 in early vesicles in BMDMs prior to CpG stimulation and accelerates TLR9 redistribution to early endosomes in response to CpG‐ODN.108 As HMGB1 secretion increases when BMDMs and BMDCs are treated with CpG, it is likely that HMGB1 acts at 2 levels: in the extracellular space by binding to CpG and in the intracellular space by hastening TLR9 shuttling and, thus, catalyzing the TLR9 signaling cascade.107, 108

8. THE CONTROVERSIAL ROLE OF TLR9 PROTEOLYTIC CLEAVAGE EVENTS

An additional mechanism that limits TLR9 activation involves a multistep proteolytic cleavage that is required for MyD88 recruitment and the triggering of both signaling cascades.109 The cleavage of TLR9 occurs in endolysosomal compartments as an evolutionary strategy to prevent aberrant self‐recognition, such that the 150 kDa full‐length receptor on the plasma membrane, which is potentially in contact with self‐DNA, remains nonfunctional.

In the endolysosomes of macrophages, lysosomal cathepsins and endopeptidases, which function only at acidic pH, cleave the TLR9 ectodomain between LRR14 and 15 into an 80 kDa protein.109, 110, 111 Additional proteolytic events that involve asparagine endopeptidase occur in both myeloid and plasmacytoid DCs, showing that different cell types may activate specific proteolytic pathways.112, 113

Other studies have shown how TLR9 proteolysis fine‐tunes downstream signaling, by showing that alternative cleavage of endogenous TLR9 negatively regulates its signal transduction. Specifically, Chockalingam et al. described a novel proteolytic cleavage that results in the formation of soluble TLR9 (sTLR9), which binds to CpG DNA and hinders TLR9 transduction. The authors showed that the neutralization of endosomal pH had no effect on TLR9 formation, suggesting that the alternative cleavage may depend on cathepsin S, a protease active at both acidic and neutral pH.114

Similarly, another study found an N‐terminal cleavage product of TLR9 that negatively regulates its signaling; by binding to the C‐terminal fragment, the N‐terminal product accelerates the dissociation of C‐terminal homodimers and promotes its aspartic protease‐mediated degradation. This autoregulatory negative‐feedback mechanism may prevent excessive TLR9 signaling.115 In contrast, Onji et al. showed that the N‐terminal cleavage product of TLR9 is required for signaling.116 These discordant results highlight the complex regulation of TLR9 signaling controlled by its own processing and cleavage products.

Finally, Sinha et al. showed that the cleaved and mature form of TLR9 (the C‐terminal fragment TLR9471‐1032) is by itself unable to respond to CpG DNA when transfected into TLR9‐deficient macrophages or DCs. Moreover, its activity was not rescued either by the co‐expression of the N‐terminal fragment, which fails to restore the native glycosylation pattern of TLR9471‐1032, or inclusion of the cleavage site.117 These data suggest that TLR9471‐1032 is generated from full‐length TLR9 in the endosome in the presence of its ligand; if these conditions are not met, the active form is not properly glycosylated and may act as a negative regulator.117

9. DOWNSTREAM TLR9 ENGAGEMENT

Signal transduction begins once TLR9 and its ligand enter the endolysosomal system. TLR9 engagement leads to the recruitment of different players, depending on the cell type. In cDCs, macrophages, and pDCs, TLR9 activates the signaling cascade that culminates with the production of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF‐α, IL‐6, and IL‐12. Instead, the receptor initiates the pathway that leads to type I IFN release primarily, but not exclusively, in pDCs. These 2 signaling cascades are discussed in detail below.

9.1. TIRAP: An adaptor only for the TLRs on the plasma membrane?

Several studies have investigated whether intracellular TLRs require sorting adaptor molecules, such as TIRAP, to signal. The sorting capacity of TIRAP relies on its amino‐terminal localization domain, which was initially believed to strictly localize TIRAP at the plasma membrane, in association with PI(4,5)P2.84, 118 However, the group of Jonathan Kagan shed new light on the role of TIRAP in TLR9 signaling.119 They challenged wild‐type and TIRAP‐knockout BMDMs and pDCs with either CpG or specific HSV‐1 strains that are sensed only by TLR9, as reported by Sato et al.120 Intriguingly, IL‐1β and IL‐6 production was impaired only in TIRAP‐knockout BMDMs stimulated with HSV‐1. Their results suggest that TIRAP plays a crucial role in sensing natural TLR9 ligands, such as HSV‐1.119 Conversely, Piao et al. reported less production of TNF‐α and IL‐6 after CpG stimulation of primary macrophages treated with 2R9, a peptide that binds TIRAP, inhibiting its binding to TIR domains. Thus, the role of TIRAP in macrophage activation upon TLR9 challenge may depend on the stimulus and may enhance myddosome formation.121

Bonham et al. also investigated how TIRAP influences the signaling of intracellular TLRs by stimulating wild‐type and TIRAP‐knockout pDCs. The authors chose pDCs as their in vitro model because these cells respond to infections exclusively via endosomal TLRs119 and allow investigation of the functions of TIRAP in the various endosome populations that generate the bifurcated pathway.70 Intriguingly, upon HSV stimulation, TIRAP knockout pDCs were unable to produce IFN‐α but not IL‐12p40.119 These results suggest that TIRAP is essential for the signaling that begins from late endosomal compartments.70 Finally, the authors confirmed that TIRAP can bind to multiple lipids122 and showed that its interaction with 3′ PIs and phosphatidylserine (PS) in the endosome is sufficient to promote the TLR9 signaling that leads to type I IFN production.119 Recently, Ve et al. proposed a sequential and cooperative model for the assembly of TIR‐signaling complexes. Their structural and kinetic data demonstrate that sequential monomer addition, rather than dimerization and trimerization, is more favorable, providing a more sensitive response.123 Javmen et al. also investigated the role of TIRAP in TLR9 signaling by screening a peptide library derived from TLR9 TIR. They uncovered inhibitory peptides that block TLR9 signaling in vitro and in vivo. In particular, they showed that the 9R34‐ΔN peptide can bind to both TLR9 TIR and TIRAP TIR, suggesting a common mode of TIR domain interaction in the primary receptor complex.124

9.2. The production of pro‐inflammatory cytokines

Once the ligand binds to the leucine‐rich repeats in the ectodomain of TLR9, the receptor undergoes a conformational change that allows the formation of homodimers and association of the TIR domains.125 Depending on the cell type and stimulus, the juxtaposed TIR domains recruit TIRAP119, 120 and the adaptor molecule MyD88, which interacts with IRAK4 through its N‐terminal death domain (DD).126 IRAK4 phosphorylates and activates IRAK1 and IRAK2, which then activate the E3 ubiquitin ligase TRAF6.127, 128 TRAF6 mediates the formation of K63‐linked polyubiquitin chains on NF‐κB essential modulator (NEMO or IKK‐γ) and itself.129 These chains create a scaffold for the recruitment of TAB2 and allow the formation of a multiprotein complex composed of TRAF6,130 NEMO, TAB2, TAB1, and TAK1.131 In parallel, the NEMO recruits IKK‐β, which is phosphorylated by TAK1.132, 133 Activation of the IKK proteins134 results in the phosphorylation of IκBs,135 which leads to their degradation and the translocation of NF‐κB to the nucleus. At the same time, TAK1 mediates the activation of the MAPK‐signaling cascade, resulting in the nuclear translocation of AP‐1.136 Simultaneously, IRF1 and IRF5 are directly activated by MyD88.137, 138 Finally, the activated IRFs, NF‐κB, and AP‐1 induce the expression of pro‐inflammatory cytokines (TNF‐α, IL‐6, and IL‐12).

9.3. The production of type I IFN

Several studies have shown that only pDCs produce type I IFN following TLR9 engagement; however, cDCs and macrophages can also release IFNs upon TLR9 challenge.139, 140 Here, we describe the signaling pathway in pDCs, the major producers of type I IFN.

9.4. pDCs and type I IFN production

Type I IFN production by pDCs is essential to protect the host against viral infections.141 Whether the signal from the IRF‐SE occurs sequentially or simultaneously to that triggered from the NF‐κB‐SE is still under discussion. Once AP‐3 interacts with TLR9 and shuttles from the NF‐κB‐SE to the LROs, the pathway forks.70 At this point, TIRAP acts as a sorting adaptor and is required for the formation of the myddosome, a multiprotein complex. MyD88 recruits IRAK4,141, 142 which then interacts with TRAF6, TRAF3,143, 144 and IRAK 1.145 Once this multiprotein complex has formed, IRF7 association with MyD88 and TRAF6 promotes IFN‐α production.28, 29, 146 In addition, IKK‐α enhances IFN‐α release via IRF7 phosphorylation.147 Hence, IRF7 disassociation from the complex and its translocation to the nucleus induces type I IFN transcription.

An additional player in the pathway is osteopontin (OPN), which contributes to the induction of IFN‐α production, specifically in pDCs, because they express intracellular OPN, as opposed to cDCs, which do not. Although the precise mechanism by which OPN supports type I IFN release is still unknown, it is considered to be a functional member of the multiprotein complex. Indeed, upon TLR9 engagement, it localizes near TLR9 and MyD88, favoring the IRF7 pathway.148 The importance of OPN in TLR9 signaling has also been confirmed by the fact that OPN‐deficient animals produce reduced levels of IFN‐α when challenged with inactivated HSV.148

Another pathway that supports type I IFN release is phosphoinositol 3‐OH kinase (PI3K)‐mTOR signaling. The pharmacologic inhibition of the kinase or mTOR reduces the interaction between TLR9 and MyD88 and impairs the production of type I IFN.149 The mechanism by which PI3K promotes IRF7 activation and translocation into the nucleus in human pDCs has not yet been fully dissected,143 but it is likely that PI3K acts together with other regulatory elements of the pathway.

Finally, type I IFN is a positive regulator of its own pathway; it enhances the expression of TLR9 and MyD88, further increasing its production.72

10. AUTOIMMUNITY: THE CASE OF TLR9

The etiopathogenesis of most autoimmune diseases is still unclear, as several factors may contribute to their onset, such as the presence of autoantibodies, high serum levels of type I IFNs,150 or increased cell death, which trigger diseases such as RA and system lupus erythematosus (SLE).145 As the insufficient clearance of necrotic cells in RA and SLE results in the accumulation of nucleic‐acid containing material,151 researchers have investigated whether TLR9 is involved in these autoimmune responses. Indeed, in contrast to TLR4, the dysregulation of TLR9 signaling has been associated with autoimmunity, even though its precise role is still a subject of debate. A study has shown that the receptors for the Fc region of IgG (FcγR) sense immune complexes and induce their entry into the endosomal system, where self‐DNA encounters TLR9. This leads to higher production of both pro‐inflammatory cytokines and type I IFNs.152 Accordingly, the activation of the TLR9 pathway in pDCs and autoreactive B cells has been associated with SLE and RA.4, 153, 154 Below, we provide a brief overview of the findings that have suggested how TLR9 may be involved in specific autoimmune diseases

10.1. Systemic lupus erythematosus

Several lines of evidence support the involvement of TLR9 in the onset of SLE. First, SLE patients exhibit an altered balance in the circulating subtypes of DCs, as their pDC compartment, specialized in the production of type I IFN, is more prominant than normal.155 Second, B cells and monocytes from SLE patients are characterized by increased levels of TLR9 expression, which correlate with higher levels of autoantibodies against dsDNA.154, 156 Moreover, aside from the crucial role of TLR7 in the pathogenesis of SLE, it appears that only TLR9 is required for one of the hallmarks of SLE: the production of anti‐DNA antibodies.157

Despite these results, other studies support the hypothesis that TLR9 has a protective role in the pathogenesis of SLE. For example, TLR9‐deficient mice exhibit clear lupus‐like clinical manifestations158 and TLR9−/− autoimmune‐prone MRL/lpr animals have a shorter lifespan due to severe SLE and glomerulonephritis.4 Consistent with these results, another study has proposed that TLR9 acts as a negative regulator of TLR7, the main culprit of SLE pathogenesis,158 by competing for UNC93B1 in the ER.159, 160 Indeed, a point mutation in UNC93B1 (D34A) facilitates the association with TLR7 and dampens TLR9 activity, leading to severe systemic inflammation in Unc93b1D34A/D34A mice.160

10.2. Rheumatoid arthritis

The role of TLR9 in RA is still a subject of debate. On the one hand, some studies have proposed that TLR9 worsens the severity of RA.161 For example, Asagiri et al. showed that the treatment of adjuvant‐induced arthritic rats with an inhibitor of cathepsin K led to defective TLR9 signaling and improvement of their pathologic state, even though the role of this protease in the TLR9 signaling pathway is still poorly understood.153 On the other hand, Miles et al. reported that the administration of apoptotic cells in a murine model of collagen‐induced arthritis led to a TLR9‐dependent anti‐inflammatory effect, supporting the hypothesis that TLR9 signaling is protective against RA.162

10.3. Psoriasis

Another molecule that promotes aberrant activation of TLR9, thus inducing autoimmune diseases, is the anti‐microbial cathelicidin LL37, a hallmark of psoriasis also found in synovial membranes of arthritis patients.163 Human LL37 is a carboxy‐terminal peptide fragment derived from the cathelicidin precursor (human cationic antibacterial protein of 18 kDa orhCAP18) and has many anti‐microbial properties.164 Upon tissue damage, LL37 binds covalently to self‐DNA in pDCs and facilitates DNA internalization into the endolysosomal system; once in the endosome, TLR9 may bind to self‐DNA, inducing type I IFN production and triggering the onset of psoriasis.165, 166 Also, LL37 in keratinocytes contributes to the exacerbation of psoriasis via the activation of TLR9 and the production of type I IFN.167, 168

10.4. Intracellular TLRs and other autoimmune diseases

Aside from the aberrant sensing of self‐DNA by TLR9, autoimmune diseases may also result from the misregulation of intracellular TLR9 trafficking. Indeed, it has recently been demonstrated that improper trafficking may be related to autoimmunity via perturbation of intracellular TLR pathways.169 For example, mice lacking one of the components of the SWC complex (a protein complex involved in autophagy and endocytosis and composed of Smith‐Magenis syndrome chromosome region candidate 8 SMCR8, WD repeat domain 41 WDR41, and C9ORF72) exhibit impaired intracellular TLR signaling that leads to autoimmunity reactions and systemic inflammation.170 Indeed, SMCR8 negatively regulates endosomal TLR signaling, and the entire complex contributes to the vesicle acidification required to degrade TLR ligands and avoid persistent stimulation.169 A study has also suggested that amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) in humans could be caused by C9ORF72 repeat expansion because it generates a loss‐of‐function SWC complex.171 Thus, the role of TLR9 in distinct autoimmune disorders is still unclear and further insights are required to shed light on the context‐dependent effects of the engagement of this receptor.

11. CONCLUDING REMARKS

Over the last few years, a more comprehensive picture of the plasma membrane and intracellular signaling cascades, networks, transcriptional regulation, and other processes associated with the TLR response has emerged. In this review, we have discussed up‐to‐date knowledge of the regulation of the pathways elicited by TLR4 and TLR9 and their roles in host defense and autoimmunity.

Endocytosis and protein trafficking in TLR4 signaling are recently identified regulatory mechanisms of innate immunity and many studies have focused on the identification of the molecules involved in their modulation, leading to the discovery of new players and functions. For example, CD14 and MD‐2 are now considered to comprise a novel category of regulators of innate immunity, called transporter associated with the execution of inflammation (TAXI), rather than “classic” chaperone proteins.172

The trafficking of TLR9 has also emerged as a crucial checkpoint of its pathway, as adaptor proteins, LAMPs, cytoskeleton stabilizers, and PI kinases contribute to guiding TLR9 signal transduction. However, some of the mechanisms behind TLR9 trafficking are still poorly understood.

Further studies are needed to fully understand the regulation of TLR9 and TLR4 signaling. An in‐depth understanding of the regulatory mechanisms would allow, for example, steering the TLR9 pathway toward a specific immune response. Moreover, TAXI and trafficking regulators may become novel targets to prevent overt inflammation and potentiate vaccines and cancer therapies.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORSHIP

L.M. wrote the introduction and the chapters on TLR4 and TLR9 cleavage, corrected the manuscript, and drew Fig. 1. L.G. wrote the TLR9 chapter and drew Fig. 2. I.A. wrote the section on intracellular TLRs. I.Z. revised the review and made suggestions. F.G. supervised the drafting of the manuscript and performed the final editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I.Z. is supported by NIH grant 1R01AI121066‐01A1, grant HDDC P30 DK034854, the Harvard Medical School Milton Fund, CCFA Senior Research Awards, and the Cariplo Foundation. F.G. is supported by the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (IG 2016Id.18842), the Cariplo Foundation (Grant 2014‐0655), and the Fondazione Regionale per la Ricerca Biomedica, FRRB.

Marongiu L, Gornati L, Artuso I, Zanoni I, Granucci F. Below the surface: The inner lives of TLR4 and TLR9. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;106:147–160. 10.1002/JLB.3MIR1218-483RR

REFERENCES

- 1. Janeway CA, Jr . Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1989;54(Pt 1):1‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Joffre O, Nolte MA, Sporri R, Reis e Sousa C. Inflammatory signals in dendritic cell activation and the induction of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:234‐247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fox RI, Kang HI. Pathogenesis of Sjogren's syndrome. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1992;18:517‐538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Christensen SR, Shupe J, Nickerson K, Kashgarian M, Flavell RA, Shlomchik MJ. Toll‐like receptor 7 and TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus. Immunity. 2006;25:417‐428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Krishnamoorthy G, Saxena A, Mars LT, et al. Myelin‐specific T cells also recognize neuronal autoantigen in a transgenic mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 2009;15:626‐632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ntelis K, Solomou EE, Sakkas L, Liossis SN, Daoussis D. The role of platelets in autoimmunity, vasculopathy, and fibrosis: implications for systemic sclerosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47:409‐417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nielen MM, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink HW, et al. Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:380‐386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Conrad C, Boyman O, Tonel G, et al. Alpha1beta1 integrin is crucial for accumulation of epidermal T cells and the development of psoriasis. Nat Med. 2007;13:836‐842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O'Neill LA, Golenbock D, Bowie AG. The history of Toll‐like receptors—redefining innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:453‐460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bell JK, Mullen GE, Leifer CA, Mazzoni A, Davies DR, Segal DM. Leucine‐rich repeats and pathogen recognition in Toll‐like receptors. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:528‐533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O'Neill LA, Bowie AG. The family of five: tIR‐domain‐containing adaptors in Toll‐like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:353‐364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brubaker SW, Bonham KS, Zanoni I, Kagan JC. Innate immune pattern recognition: a cell biological perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:257‐290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783‐801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang SY, Jouanguy E, Ugolini S, et al. TLR3 deficiency in patients with herpes simplex encephalitis. Science. 2007;317:1522‐1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kleinman ME, Yamada K, Takeda A, et al. Sequence‐ and target‐independent angiogenesis suppression by siRNA via TLR3. Nature. 2008;452:591‐597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bernard JJ, Cowing‐Zitron C, Nakatsuji T, et al. Ultraviolet radiation damages self noncoding RNA and is detected by TLR3. Nat Med. 2012;18:1286‐1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mancuso G, Gambuzza M, Midiri A, et al. Bacterial recognition by TLR7 in the lysosomes of conventional dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:587‐594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guiducci C, Gong M, Cepika AM, et al. RNA recognition by human TLR8 can lead to autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2903‐2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Forsbach A, Nemorin JG, Montino C, et al. Identification of RNA sequence motifs stimulating sequence‐specific TLR8‐dependent immune responses. J Immunol. 2008;180:3729‐3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Coban C, Igari Y, Yagi M, et al. Immunogenicity of whole‐parasite vaccines against Plasmodium falciparum involves malarial hemozoin and host TLR9. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:50‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parroche P, Lauw FN, Goutagny N, et al. Malaria hemozoin is immunologically inert but radically enhances innate responses by presenting malaria DNA to Toll‐like receptor 9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1919‐1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li XD, Chen ZJ. Sequence specific detection of bacterial 23S ribosomal RNA by TLR13. Elife 2012;1:e00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shi Z, Cai Z, Sanchez A, et al. A novel Toll‐like receptor that recognizes vesicular stomatitis virus. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:4517‐4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mathur R, Oh H, Zhang D, et al. A mouse model of Salmonella typhi infection. Cell. 2012;151:590‐602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yarovinsky F, Zhang D, Andersen JF, et al. TLR11 activation of dendritic cells by a protozoan profilin‐like protein. Science. 2005;308:1626‐1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koblansky AA, Jankovic D, Oh H, et al. Recognition of profilin by Toll‐like receptor 12 is critical for host resistance to Toxoplasma gondii . Immunity. 2013;38:119‐130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, et al. TRAM is specifically involved in the Toll‐like receptor 4‐mediated MyD88‐independent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1144‐1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Honda K, Yanai H, Negishi H, et al. IRF‐7 is the master regulator of type‐I interferon‐dependent immune responses. Nature. 2005;434:772‐777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Honda K, Ohba Y, Yanai H, et al. Spatiotemporal regulation of MyD88‐IRF‐7 signalling for robust type‐I interferon induction. Nature. 2005;434:1035‐1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim YM, Brinkmann MM, Paquet ME, Ploegh HL. UNC93B1 delivers nucleotide‐sensing toll‐like receptors to endolysosomes. Nature. 2008;452:234‐238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee BL, Moon JE, Shu JH, et al. UNC93B1 mediates differential trafficking of endosomal TLRs. Elife. 2013;2:e00291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pelka K, Bertheloot D, Reimer E, et al. The chaperone UNC93B1 regulates Toll‐like receptor stability independently of endosomal TLR transport. Immunity. 2018;48:911‐922. e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yang Y, Liu B, Dai J, et al. Heat shock protein gp96 is a master chaperone for toll‐like receptors and is important in the innate function of macrophages. Immunity. 2007;26:215‐226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Takahashi K, Shibata T, Akashi‐Takamura S, et al. A protein associated with Toll‐like receptor (TLR) 4 (PRAT4A) is required for TLR‐dependent immune responses. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2963‐2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Medzhitov R, Preston‐Hurlburt P. A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature. 1997;388:394‐397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kagan JC, Su T, Horng T, Chow A, Akira S, Medzhitov R. TRAM couples endocytosis of Toll‐like receptor 4 to the induction of interferon‐beta. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:361‐368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brandt KJ, Fickentscher C, Kruithof EK, de Moerloose P. TLR2 ligands induce NF‐kappaB activation from endosomal compartments of human monocytes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barbalat R, Lau L, Locksley RM, Barton GM. Toll‐like receptor 2 on inflammatory monocytes induces type I interferon in response to viral but not bacterial ligands. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1200‐1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steimle A, Autenrieth IB, Frick JS. Structure and function: lipid A modifications in commensals and pathogens. Int J Med Microbiol. 2016;306:290‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rittig MG, Kaufmann A, Robins A, et al. Smooth and rough lipopolysaccharide phenotypes of Brucella induce different intracellular trafficking and cytokine/chemokine release in human monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:1045‐1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mathison JC, Tobias PS, Wolfson E, Ulevitch RJ. Plasma lipopolysaccharide (LPS)‐binding protein. A key component in macrophage recognition of gram‐negative LPS. J Immunol. 1992;149:200‐206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tsukamoto H, Fukudome K, Takao S, Tsuneyoshi N, Kimoto M. Lipopolysaccharide‐binding protein‐mediated Toll‐like receptor 4 dimerization enables rapid signal transduction against lipopolysaccharide stimulation on membrane‐associated CD14‐expressing cells. Int Immunol. 2010;22:271‐280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. da Silva Correia J, Soldau K, Christen U, Tobias PS, Ulevitch RJ. Lipopolysaccharide is in close proximity to each of the proteins in its membrane receptor complex. transfer from CD14 to TLR4 and MD‐2. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21129‐21135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schmitz G, Orso E. CD14 signalling in lipid rafts: new ligands and co‐receptors. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:513‐521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Park BS, Song DH, Kim HM, Choi BS, Lee H, Lee JO. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4‐MD‐2 complex. Nature. 2009;458:1191‐1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gioannini TL, Teghanemt A, Zhang D, et al. Isolation of an endotoxin‐MD‐2 complex that produces Toll‐like receptor 4‐dependent cell activation at picomolar concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4186‐4191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zanoni I, Ostuni R, Capuano G, et al. CD14 regulates the dendritic cell life cycle after LPS exposure through NFAT activation. Nature. 2009;460:264‐268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hagar JA, Powell DA, Aachoui Y, Ernst RK, Miao EA. Cytoplasmic LPS activates caspase‐11: implications in TLR4‐independent endotoxic shock. Science. 2013;341:1250‐1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kayagaki N, Wong MT, Stowe IB, et al. Noncanonical inflammasome activation by intracellular LPS independent of TLR4. Science. 2013;341:1246‐1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Broz P, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes: mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:407‐420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang Y, et al. Inflammatory caspases are innate immune receptors for intracellular LPS. Nature. 2014;514:187‐192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Medzhitov R. Toll‐like receptors and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:135‐145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Motshwene PG, Moncrieffe MC, Grossmann JG, et al. An oligomeric signaling platform formed by the Toll‐like receptor signal transducers MyD88 and IRAK‐4. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:25404‐25411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Piao W, Ru LW, Piepenbrink KH, Sundberg EJ, Vogel SN, Toshchakov VY. Recruitment of TLR adapter TRIF to TLR4 signaling complex is mediated by the second helical region of TRIF TIR domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:19036‐19041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fitzgerald KA, McWhirter SM, Faia KL, et al. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:491‐496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zanoni I, Ostuni R, Marek LR, et al. CD14 controls the LPS‐induced endocytosis of Toll‐like receptor 4. Cell. 2011;147:868‐880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. West MA, Wallin RP, Matthews SP, et al. Enhanced dendritic cell antigen capture via toll‐like receptor‐induced actin remodeling. Science. 2004;305:1153‐1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thomas L, Bielemeier A, Lambert PA, Darveau RP, Marshall LJ, Devitt A. The N‐terminus of CD14 acts to bind apoptotic cells and confers rapid‐tethering capabilities on non‐myeloid cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zanoni I, Spreafico R, Bodio C, et al. IL‐15 cis presentation is required for optimal NK cell activation in lipopolysaccharide‐mediated inflammatory conditions. Cell Rep. 2013;4:1235‐1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jiang Z, Georgel P, Du X, et al. CD14 is required for MyD88‐independent LPS signaling. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:565‐570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chiang CY, Veckman V, Limmer K, David M. Phospholipase Cgamma‐2 and intracellular calcium are required for lipopolysaccharide‐induced Toll‐like receptor 4 (TLR4) endocytosis and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) activation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:3704‐3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schappe MS, Szteyn K, Stremska ME, et al. Chanzyme TRPM7 mediates the Ca(2+) influx essential for lipopolysaccharide‐induced Toll‐like receptor 4 endocytosis and macrophage activation. Immunity. 2018;48:59‐74. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Granucci F. The family of LPS signal transducers increases: the arrival of chanzymes. Immunity. 2018;48:4‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tan Y, Zanoni I, Cullen TW, Goodman AL, Kagan JC. Mechanisms of Toll‐like receptor 4 endocytosis reveal a common immune‐evasion strategy used by pathogenic and commensal bacteria. Immunity. 2015;43:909‐922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ling GS, Bennett J, Woollard KJ, et al. Integrin CD11b positively regulates TLR4‐induced signalling pathways in dendritic cells but not in macrophages. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ghosh M, Subramani J, Rahman MM, Shapiro LH. CD13 restricts TLR4 endocytic signal transduction in inflammation. J Immunol. 2015;194:4466‐4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Perkins DJ, Richard K, Hansen AM, et al. Autocrine‐paracrine prostaglandin E2 signaling restricts TLR4 internalization and TRIF signaling. Nat Immunol. 2018;19:1309‐1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Latz E, Schoenemeyer A, Visintin A, et al. TLR9 signals after translocating from the ER to CpG DNA in the lysosome. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:190‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Barton GM, Kagan JC, Medzhitov R. Intracellular localization of Toll‐like receptor 9 prevents recognition of self DNA but facilitates access to viral DNA. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:49‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sasai M, Linehan MM, Iwasaki A. Bifurcation of Toll‐like receptor 9 signaling by adaptor protein 3. Science. 2010;329:1530‐1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Babdor J, Descamps D, Adiko AC, et al. IRAP(+) endosomes restrict TLR9 activation and signaling. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:509‐518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Combes A, Camosseto V, N'Guessan P, et al. BAD‐LAMP controls TLR9 trafficking and signalling in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Webster B, Werneke SW, Zafirova B, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells control dengue and Chikungunya virus infections via IRF7‐regulated interferon responses. Elife. 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Swiecki M, Gilfillan S, Vermi W, Wang Y, Colonna M. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell ablation impacts early interferon responses and antiviral NK and CD8(+) T cell accrual. Immunity. 2010;33:955‐966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Saveanu L, Carroll O, Weimershaus M, et al. IRAP identifies an endosomal compartment required for MHC class I cross‐presentation. Science. 2009;325:213‐217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Weimershaus M, Maschalidi S, Sepulveda F, Manoury B, van Endert P, Saveanu L. Conventional dendritic cells require IRAP‐Rab14 endosomes for efficient cross‐presentation. J Immunol. 2012;188:1840‐1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Weimershaus M, Mauvais FX, Saveanu L, et al. Innate immune signals induce anterograde endosome transport promoting MHC class I cross‐presentation. Cell Rep. 2018;24:3568‐3581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Blasius AL, Arnold CN, Georgel P, et al. Slc15a4, AP‐3, and Hermansky‐Pudlak syndrome proteins are required for Toll‐like receptor signaling in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:19973‐19978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Bultema JJ, Ambrosio AL, Burek CL, Pietro D, BLOC‐2 SM. AP‐3, and AP‐1 proteins function in concert with Rab38 and Rab32 proteins to mediate protein trafficking to lysosome‐related organelles. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:19550‐19563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Feng L, Seymour AB, Jiang S, et al. The beta3A subunit gene (Ap3b1) of the AP‐3 adaptor complex is altered in the mouse hypopigmentation mutant pearl, a model for Hermansky‐Pudlak syndrome and night blindness. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:323‐330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Prandini A, Salvi V, Colombo F, et al. Impairment of dendritic cell functions in patients with adaptor protein‐3 complex deficiency. Blood. 2016;127:3382‐3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. De Matteis MA, Godi A. PI‐loting membrane traffic. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:487‐492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kutateladze TG. Translation of the phosphoinositide code by PI effectors. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:507‐513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kagan JC, Medzhitov R. Phosphoinositide‐mediated adaptor recruitment controls Toll‐like receptor signaling. Cell. 2006;125:943‐955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Catimel B, Schieber C, Condron M, et al. The PI(3,5)P2 and PI(4,5)P2 interactomes. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:5295‐5313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Shisheva A. PIKfyve: partners, significance, debates and paradoxes. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32:591‐604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hazeki K, Uehara M, Nigorikawa K, Hazeki O. PIKfyve regulates the endosomal localization of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides to elicit TLR9‐dependent cellular responses. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hayashi K, Sasai M, Iwasaki A. Toll‐like receptor 9 trafficking and signaling for type I interferons requires PIKfyve activity. Int Immunol. 2015;27:435‐445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Moresco EM, Beutler B. Special delivery: granulin brings CpG DNA to Toll‐like receptor 9. Immunity. 2011;34:453‐455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Park B, Buti L, Lee S, et al. Granulin is a soluble cofactor for toll‐like receptor 9 signaling. Immunity. 2011;34:505‐513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bateman A, Belcourt D, Bennett H, Lazure C, Solomon S. Granulins, a novel class of peptide from leukocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:1161‐1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Zhu J, Nathan C, Jin W, et al. Conversion of proepithelin to epithelins: roles of SLPI and elastase in host defense and wound repair. Cell. 2002;111:867‐878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Plowman GD, Green JM, Neubauer MG, et al. The epithelin precursor encodes two proteins with opposing activities on epithelial cell growth. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13073‐13078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Shoyab M, McDonald VL, Byles C, Todaro GJ, Plowman GD. Epithelins 1 and 2: isolation and characterization of two cysteine‐rich growth‐modulating proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:7912‐7916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Tanaka A, Tsukamoto H, Mitoma H, et al. Serum progranulin levels are elevated in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, reflecting disease activity. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Chen X, Wen Z, Xu W, Xiong S. Granulin exacerbates lupus nephritis via enhancing macrophage M2b polarization. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Qiao B, Wu J, Chu YW, et al. Induction of systemic lupus erythematosus‐like syndrome in syngeneic mice by immunization with activated lymphocyte‐derived DNA. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44:1108‐1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Wu J, Su W, Powner MB, et al. Pleiotropic action of CpG‐ODN on endothelium and macrophages attenuates angiogenesis through distinct pathways. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Nightingale K, Dimitrov S, Reeves R, Wolffe AP. Evidence for a shared structural role for HMG1 and linker histones B4 and H1 in organizing chromatin. Embo j. 1996;15:548‐561. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Agresti A, Scaffidi P, Riva A, Caiolfa VR, Bianchi ME. GR and HMGB1 interact only within chromatin and influence each other's residence time. Mol Cell. 2005;18:109‐121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Lange SS, Mitchell DL, Vasquez KM. High mobility group protein B1 enhances DNA repair and chromatin modification after DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10320‐10325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. van Gent DC, Hiom K, Paull TT, Gellert M. Stimulation of V(D)J cleavage by high mobility group proteins. Embo j. 1997;16:2665‐2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Little AJ, Corbett E, Ortega F, Schatz DG. Cooperative recruitment of HMGB1 during V(D)J recombination through interactions with RAG1 and DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:3289‐3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Boonyaratanakornkit V, Melvin V, Prendergast P, et al. High‐mobility group chromatin proteins 1 and 2 functionally interact with steroid hormone receptors to enhance their DNA binding in vitro and transcriptional activity in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4471‐4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;418:191‐195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Qin S, Wang H, Yuan R, et al. Role of HMGB1 in apoptosis‐mediated sepsis lethality. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1637‐1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Tian J, Avalos AM, Mao SY, et al. Toll‐like receptor 9‐dependent activation by DNA‐containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:487‐496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Ivanov S, Dragoi AM, Wang X, et al. A novel role for HMGB1 in TLR9‐mediated inflammatory responses to CpG‐DNA. Blood. 2007;110:1970‐1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Ewald SE, Lee BL, Lau L, et al. The ectodomain of Toll‐like receptor 9 is cleaved to generate a functional receptor. Nature. 2008;456:658‐662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Park B, Brinkmann MM, Spooner E, Lee CC, Kim YM, Ploegh HL. Proteolytic cleavage in an endolysosomal compartment is required for activation of Toll‐like receptor 9. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1407‐1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Seya T, Shingai M, Matsumoto M. [Toll‐like receptors that sense viral infection]. Uirusu. 2004;54:1‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Sepulveda FE, Maschalidi S, Colisson R, et al. Critical role for asparagine endopeptidase in endocytic Toll‐like receptor signaling in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2009;31:737‐748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Ewald SE, Engel A, Lee J, Wang M, Bogyo M, Barton GM. Nucleic acid recognition by Toll‐like receptors is coupled to stepwise processing by cathepsins and asparagine endopeptidase. J Exp Med. 2011;208:643‐651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Chockalingam A, Cameron JL, Brooks JC, Leifer CA. Negative regulation of signaling by a soluble form of toll‐like receptor 9. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2176‐2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Lee S, Kang D, Ra EA, Lee TA, Ploegh HL, Park B. Negative self‐regulation of TLR9 signaling by its N‐terminal proteolytic cleavage product. J Immunol. 2014;193:3726‐3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Onji M, Kanno A, Saitoh S, et al. An essential role for the N‐terminal fragment of Toll‐like receptor 9 in DNA sensing. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Sinha SS, Cameron J, Brooks JC, Leifer CA. Complex negative regulation of TLR9 by multiple proteolytic cleavage events. J Immunol. 2016;197:1343‐1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Aksoy E, Taboubi S, Torres D, et al. The p110delta isoform of the kinase PI(3)K controls the subcellular compartmentalization of TLR4 signaling and protects from endotoxic shock. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1045‐1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Bonham KS, Orzalli MH, Hayashi K, et al. A promiscuous lipid‐binding protein diversifies the subcellular sites of toll‐like receptor signal transduction. Cell. 2014;156:705‐716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Sato A, Linehan MM, Iwasaki A. Dual recognition of herpes simplex viruses by TLR2 and TLR9 in dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17343‐17348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Piao W, Shirey KA, Ru LW, et al. A decoy peptide that disrupts TIRAP recruitment to TLRs is protective in a murine model of influenza. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1941‐1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Kavran JM, Klein DE, Lee A, et al. Specificity and promiscuity in phosphoinositide binding by pleckstrin homology domains. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30497‐30508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Ve T, Vajjhala PR, Hedger A, et al. Structural basis of TIR‐domain‐assembly formation in MAL‐ and MyD88‐dependent TLR4 signaling. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017;24:743‐751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Javmen A, Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR, Toshchakov VY. Blocking TIR domain interactions in TLR9 signaling. J Immunol. 2018;201:995‐1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Latz E, Verma A, Visintin A, et al. Ligand‐induced conformational changes allosterically activate Toll‐like receptor 9. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:772‐779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Suzuki N, Suzuki S, Duncan GS, et al. Severe impairment of interleukin‐1 and Toll‐like receptor signalling in mice lacking IRAK‐4. Nature. 2002;416:750‐756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Kawagoe T, Sato S, Matsushita K, et al. Sequential control of Toll‐like receptor‐dependent responses by IRAK1 and IRAK2. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:684‐691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Hacker H, Vabulas RM, Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Akira S, Wagner H. Immune cell activation by bacterial CpG‐DNA through myeloid differentiation marker 88 and tumor necrosis factor receptor‐associated factor (TRAF)6. J Exp Med. 2000;192:595‐600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Siggs OM, Berger M, Krebs P, et al. A mutation of Ikbkg causes immune deficiency without impairing degradation of IkappaB alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3046‐3051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Min Y, Kim MJ, Lee S, Chun E, Lee KY. Inhibition of TRAF6 ubiquitin‐ligase activity by PRDX1 leads to inhibition of NFKB activation and autophagy activation. Autophagy. 2018;14:1347‐1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Scheidereit C. IkappaB kinase complexes: gateways to NF‐kappaB activation and transcription. Oncogene. 2006;25:6685‐6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Takaesu G, Surabhi RM, Park KJ, Ninomiya‐Tsuji J, Matsumoto K, Gaynor RB. TAK1 is critical for IkappaB kinase‐mediated activation of the NF‐kappaB pathway. J Mol Biol. 2003;326:105‐115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Bonizzi G, Bebien M, Otero DC, et al. Activation of IKKalpha target genes depends on recognition of specific kappaB binding sites by RelB:p52 dimers. Embo j. 2004;23:4202‐4210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]