Abstract

Evidence derived from social information theories support the existence of different underlying cognitive mechanisms guiding violent behavior through life. However, a few studies have examined the contribution of school variables to those cognitive mechanisms, which may help explain violent behavior later in life. The present study examines the relationship between school attachment, violent attitudes, and violent behavior over time in a sample of urban adolescents from the U.S. Midwest. We evaluated the influence of school attachment on violent attitudes and subsequent violent behavior. We used structural equation modeling to test our hypothesis in a sample of 579 participants (54.9% female, 81.3% African American). After controlling for gender and race, our results indicated that the relationship between school attachment and violent behavior over time is mediated by violent attitudes. The instrumentalization of the school context as a learning environment aiming to prevent future violent behavior is also discussed.

Keywords: mental health, violence, violent offenders, youth violence

Violent behavior is a public health concern due to its negative consequences upon young individuals and their families and social network (Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg, & Zwi, 2002). Within this context, interpersonal violence among peers is one of the expressions of violent behavior that requires special attention (Haegerich & Dahlberg, 2011). The purpose of this article is to examine the role of school attachment and violent attitude during high school as significant predictors of violent behavior across time. We hypothesize that violent attitude will be a mediator between these variables.

Violent behavior can be defined in several ways (Suris et al., 2004). Some authors describe violent behavior as the expression of aggression, causing extreme physical harm resulting in injury or even death (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). This definition may include self-inflicted, interpersonal, collective, direct or indirect, hostile or instrumental, reactive, physical, psychological, or sexual aggression. Despite its specific definition, most researchers agree that the intent to harm another person or property is behind the aggressive behavior (Berkowitz, 1993; Krug et al., 2002; Tolan, 2007).

Furthermore, school violence can also be a predictor for violent behavior later in life. For instance, Ttofi, Farrington, and Lösel (2012) conducted a systematic review that included 28 longitudinal studies assessing the effects of school bullying on students, as a victim or a perpetrator, upon the prediction of violence. Authors found that being a victim or perpetrator of bullying contributed to subsequent violent behavior, even after adjusting for other childhood risk factors.

Researchers have also found that violent experiences at school were associated with internalizing and externalizing problematic behaviors (M. Kim, Catalano, Haggerty, & Abbott, 2011; Y. Kim, Leventhal, Koh, Hubbard, & Boyce, 2006). Arseneault and colleagues (2006) examined a national sample of 2,232 children from the Environmental Risk Longitudinal Twin Study and found that bullying victims experienced more internalizing problems compared with control children. Similarly, Farmer et al. (2015) assessed internalizing and externalizing behaviors in a group of 533 students during their transition to middle school and found that these behaviors were associated with bullying.

Several studies have consistently demonstrated that schools are a significant context in which youth experience or perpetrate violent behavior (Benbenishty & Astor, 2005; Furlong & Morrison, 2000; Hong & Espelage, 2012). Violent experiences in this context, including bullying, are significant predictors for antisocial and violent behavior later in life, even after adjusting for other contextual variables, such as family risk (Bender & Lösel, 2011). Although previous studies highlight the long-term negative effects of school violence (Farrington & Ttofi, 2011; Renda, Vassallo, & Edwards, 2011), only a few studies have examined these long-term negative consequences in more detail by considering protective factors, such as school attachment and cognitive mechanisms.

Several theories have been elaborated to explain youth violence; some of these are based on underlining cognitive mechanisms (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Huesmann, 1988). All these models are underlined by the basic principles of human behavior that establish representations of cognition, highlighting the importance of individual processes such as attitudes or beliefs in the development of violent behavior (Huesmann, 1988). Consequently, attitudes can be assessed as a relevant individual mechanism for the study of violent behavior. Despite this, a few researchers have examined this variable by considering factors related to school experience, including school attachment, and its effects on violent behavior over time and on the transition into young adulthood.

Violent Attitude

Cognitive factors implicated in the development and maintenance of aggression are also predictors of risk for violent behavior and aggression (Lösel & Farrington, 2012). A relevant cognitive schema for these models involves normative beliefs, or violent attitude, which are internalized cognitions about what is appropriate behavior for a person regarding aggressive behavior in the real word. Moreover, once these cognitions are crystallized, they produce stable aggressive tendencies over an individual’s life span (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Huesmann & Guerra, 1997). Gellman and Delucia-Waack (2006) compared a sample of 45 males defined as violent against 45 nonviolent age-matched adolescent counterparts to examine potential predictors of violence. Some of the considered factors included exposure to violence, violent attitude, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptomatology. Although the study did not find significant differences for violent attitudes in both groups, violent attitude was a strong predictor for violent males.

Other studies demonstrate similar patterns; Gendron, Williams, and Guerra (2011) analyzed a sample of 7,299 students that included fifth to 11th graders and found that normative beliefs, among other variables, is a predictor for violent behavior, after adjusting for previous levels of violence. Moreover, school violence victims can develop positive attitudes toward the use of violence, which can increase the risk and the exposure to more violent behaviors (Brockenbrough, Cornell, & Loper, 2002). Thus, violent attitudes predict violent behaviors, highlighting the importance of identifying variables that influence the development of violent attitudes.

Studies on the development of violent attitude have mainly focused on predictors of risk, such as exposure to violence (Guerra, Huesmann, & Spindler, 2003), injunctive classroom norms (D. Henry et al., 2000), negative experiences with peers (Mesch, Fishman, & Eisikovits, 2003). Yet protective factors can also play a significant role on the development of violent attitude. Chung-Do, Goebert, Hamagani, Chang, and Hishinuma (2015) found that school connectedness has a negative effect upon violent attitudes, as an expression of violent behavior. We could conceptualize these associations based on the social development model (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996). Hence, according to this model school bonding operates by external constrains; demographics and personal variables influence the opportunities and skills reinforcing student bonding to the school. Within this dynamic, school attachment may influence moral order beliefs and (anti)-social behavior (Maddox & Prinz, 2003). Moreover, according to the social control theory (Hirschi, 1998) when individuals establish connections with formal institutions, such as schools, they are more likely to incorporate norms of behavior, preventing violent behavior.

Researchers have described that certain attitudes can operate as mediators of different predictors. For instance, Spaccarelli, Coatsworth, and Bowden (1995) describe how violent attitudes mediate the positive effect of violence in the family to predict aggressive behavior. Guerra et al. (2003) established a mediated model that involved exposure to violence, aggressive behavior, and normative beliefs supporting aggression. In this model, normative beliefs mediated the relationship between exposure to violence in fourth and fifth grades and subsequent aggressive behavior (sixth grade).

Children spend a significant amount of time at school; consequently, variables related to their experiences at school may be useful but can also contribute to the development of aggression (Meyer-Adams & Conner, 2008). Humans develop at multiple levels, and these do not operate independently; on the contrary, they display reciprocal influences (Lerner, 2006). Thereby, different features acquired or derived from the school can play a role against violent behavior and violent attitudes. In this case, violent attitudes are a crucial lens for youth to process social cues and incorporate information to understand appropriate behavior from the school context (Huesmann & Guerra, 1997). For example, students exposed to a violent school context are more likely to develop violent scripts and attitudes that will lead them to engage in violent behavior, limiting positive social interactions (Huesmann, 1988). Conversely, when the school provides opportunities for positive interactions among students, they are more likely to develop a sense of belonging, increasing attachment to the school (Smith & Sandhu, 2004). A positive school context also contributes to promote positive beliefs. To illustrate this point, Cunningham (2007) examined the levels of bonding and bullying behavior in a sample of 517 preadolescents and found that students at lower levels of bullying (either as a perpetrator or as a victim) reported higher levels of school bonding and prosocial beliefs. Moreover, a positive climate at school can prevent the development of negative attitudes, especially those related to violent behavior among students (Dessel, 2010). Despite the number of studies examining violent behavior, few authors have assessed school experiences and their relation to these variables to understand how violent attitudes may contribute to subsequent violent behavior. Indeed, a few researchers have considered how the effects of school attachment on violent behavior could be mediated by violent attitudes.

School Attachment

The influence of school attachment on violent behavior has been extensively studied. Lösel and Farrington (2012) summarize the role of protective factors for youth violence at different levels of human development including schools. In the school context, school bonding may play a role as a protective factor for violent behavior. Moreover, an individual negative attitude at school is commonly associated with violent behavior (K. L. Henry, Knight, & Thornberry, 2012). Conversely, a positive relationship with the school, and school satisfaction are negatively associated with violent behavior. Logan-Greene et al. (2011) examined a sample of 849 youngsters at a high risk of dropping out of school ranging from ninth to 12th grades to explore the contribution of different predictors on violent behavior and found that high levels of prosocial engagement, including school satisfaction and belonging among other variables, were negatively associated with violent behavior. Although, these results evidence the importance of protective factors, mediation models that could highlight other underlying mechanisms, especially over time, were not included in the abovementioned studies.

School bonding degree reported by students, a proxy of school attachment, is also related to violent behavior (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Catalano et al., 2004; Fleming et al., 2010). Using a sample of 6,397 adolescents from 125 schools, Brookmeyer, Fanti, and Henrich (2006) found that a better connection with the school and overall school climate can influence the development of violent behavior. Although they used multilevel methods to control for the nested effect of the school, other individual variables like violent attitudes that could explain this effect in the school context were excluded. In addition, school disengagement is related to higher levels of violent behavior during adolescence and early adulthood (K. L. Henry et al., 2012). Interestingly, school disengagement was measured on a sample of 911 participants from the Rochester Youth Development Study. The researchers measured disengagement based on standardized test scores, attendance, failing core courses, suspensions, and grade retention. The study by K. L. Henry et al. (2012) found that early school disengagement was related to subsequent violent behavior that manifested after dropping out of high school. Although these results highlight the importance of the school context and youth engagement with an institution, other underlying processes, such as violent attitudes among participants, that could help explain the effect over time are not mentioned.

Often, school attachment represents a positive dimension of school climate and teacher–student relationships (Thapa, Cohen, Guffey, & Higgins-D’Alessandro, 2013). The latter are important for classroom climate by supporting socioemotional development of students (Eccles & Roeser, 2010; Pianta, 1999). Cillessen and Mayeux (2004) also suggest that teacher may serve as positive behavior models, contributing to children’s social development. In line with this, Hurd, Hussain, and Bradshaw (2018) described that the presence of a supportive adult in high school reduced the effects of school disorder upon externalizing behaviors. Positive relationships and school attachment are also associated with lower levels of aggressive beliefs (Frey, Ruchkin, Martin, & Schwab-Stone, 2009). Yet the evidence from longitudinal studies evaluating school attachment along with violent attitudes and behavior aiming to understand direct/indirect effects is somewhat limited. Consequently, the aim of the present study is to assess the potential predictors of violent behavior associated with previous violent attitudes and school attachment. As pointed, only a handful of studies have considered these early-measured attitudinal variables together to explain later violent behavior. This approach could prove useful to capture these effects starting at adolescence in the transition into young adulthood. Via the identification of early key factors that may contribute to interrupting/maladaptive developmental pathways, our hypothesis seeks to highlight the importance of school attachment for future behavior and preventive initiatives at younger ages.

In summary, here we tested a longitudinal model of the effects of school attachment and violent attitude upon violent behavior of high school students in their transition into young adulthood. We hypothesize that school attachment during high school will display long-term effects upon violent behavior into early adulthood of individuals. We hypothesize these effects will be mediated by violent attitudes manifested during high school. In particular, we hypothesize that school attachment will have a direct effect on violent behavior at Waves 4 and 8, but that effect will be mediated by violent attitude as an indirect effect, after adjusting for race and gender.

Method

Sample

The present study was designed as a longitudinal study starting at high school age and extending into adulthood, with 12 waves of data. Participants were recruited from four public high schools in the area of Flint, Michigan, a city with a population of about 100,000 that has experienced a significant economic decline over the last half century. Adolescents with a grade point average (GPA) ≤3.0 or lower in eighth grade, with no emotional or developmental impairments (defined by each school), were recruited into the study. Data were collected from 850 adolescents. Our study only considered data from Waves 2, 3, 4, and 8. These waves represent the participants’ sophomore, junior, and senior years in high school, as well as when they were 23.1 years old on average. The final sample included 579 participants; the majority were African American participants (81.34%) and females (54.92%). We obtained a 71.3% response rate from the original Wave 2 sample to Wave 8. Missing data were handled using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimator in Mplus 6.0 (Byrne, 2012).

Data Collection

Participants were given yearly structured face-to-face interviews starting at the ninth and through the 12th grades (Waves 1–4). Waves 5 to 8 were collected annually beginning 2 years after Wave 4 was completed. The interviews lasted 60 min on average and were applied at each participant’s school or in a community setting.

Measures

Table 1 summarizes descriptive information and correlations of the studied variables. The means of violent behavior and attitudes are low as expected. Conversely, the mean of school attachment was relatively high. All four study measures have acceptable internal consistency. Violent behavior measures are correlated in both waves and with violent attitudes. School attachment is negatively correlated with violent attitudes and Wave 4 violent behavior.

Table 1.

Descriptive and Correlations Among Latent Factors.

| Latent Factors | M | SD | N | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violent behavior (w8) | 1.23 | .51 | 579 | .73 |

| Violent behavior (w4) | 1.33 | .60 | 555 | .76 |

| Violent attitude (w3) | 1.47 | .62 | 555 | .78 |

| School attachment (w2) | 2.84 | .62 | 559 | .78 |

| Correlation Matrix | Violent Behavior (w8) | Violent Behavior (w4) | Violent Attitude (w3) | School Attachment (w2) |

| Violent behavior (w8) | 1.00 | |||

| Violent behavior (w4) | .31** | 1.00 | ||

| Violent attitude (w3) | .24** | .31** | 1.00 | |

| School attachment (w2) | −.05 | −.16** | −.25** | 1.00 |

p < .01.

Violent behavior.

Violent behavior was measured using six items in Wave 4 and Wave 8. The scale assessed the level of engagement of the participants in different types of aggressive behavior, such as carrying guns or knives, getting involved in fights, and hurting someone badly. The responses from the participants ranged from 1 (0 times) to 5 (4 or more times). Higher scores indicated more violent behavior. The Cronbach’s α was .76 for Wave 4 and α =.73 for Wave 8.

Violent attitudes.

Violent attitudes were measured with four items that captured different beliefs that justify the use of violence, such as “Fighting is the best way to solve problems” and “It is ok to fight to so others students don’t think you are weak.” The scale was measured with a 4-point Likert-type scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). Higher scores indicated more agreement that violent behavior was justified. The Cronbach’s α was .75 (Wave 3).

School attachment.

The school attachment contained 7 items that measured how much the students like school and their teachers, and their level of commitment to the academic activities. Example items include the following: “I do extra work on my own in class,” “I like school,” “I like my English teacher,” and “Most mornings, I look forward to going to school.” The scale was measured with a 4-point Likert-type scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). Higher scores indicated stronger school attachment. The Cronbach’s α was .76 (Wave 2).

Data Analytic Strategy

Structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis was conducted to test the plausibility of the hypothesized conceptual model using Mplus 6.0. Mplus allows all regression equations in a mediation model to be estimated simultaneously. The model suggests that the relationship between school attachment and violent behavior is mediated by violent attitudes. The classic approach of Baron and Kenny (1986) point out that mediation requires the following conditions: (a) the predictor (school attachment) must have an effect in the hypothesized mediator (violent attitude), (b) an effect of the mediator on the dependent variable (violent behavior), (c) controlling for paths a and b, the effect of the predictor (school attachment) on the dependent variable (violent behavior) is no longer significant, which account for a full mediation process. We calculate the mediated effect as an indirect effect as the product of two coefficients (a × b) evaluating it significant on the basis of 95% confidence interval (CI) bias-corrected using bootstrapping (Hayes, 2009). In addition, the plausible models were assessed based on chi-square (χ2), the relative fit measures of normed fit index (NFI) and comparative fit index (CFI), and the estimated root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its 90% CI. As a reference, RMSEA values close to .05 indicate good fit. CFI and NFI values larger than .95 reflect a good fit, as well (Kline, 2011).

Results

Descriptive and Correlation Analysis

The Little’s Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) test gave a chi-square value = 311.83 (df = 294; p<.227), providing evidence that data are missing completely at random. Moreover, the percentage of missing values for the sample at Wave 8 represents less than 5% in the study variables.

Attrition Analysis

From the original sample (n = 850), 38 adolescents (4.5%) did not participate at Wave 2 (24 male, 14 female). Leaving the study was not associated with gender, χ2(1) = 2.8, ns. In the following year, 67 subjects did not participate (7.9%) and more males than females (45 versus 22) left the study, χ2(1) = 8.6, p = .003. By the end of High School (Wave 4), a total of 80 students did not participate (9.4%) and males (n = 54) were more likely than females (n = 26) to leave the study, χ2(1) = 10.8, p = .001. In the final wave of the study (Wave 8), 271 young adults did not participate (31.9%), and again males (n = 164) were more likely to be in the attrition group (n = 107) than females, χ2(1) = 16.6, p = .001. In addition, no differences were found between who did not participate in Waves 2 and 8 in the main study variables.

Measurement Model

The measurement model describes the factor loading coefficients for the latent constructs in the model. All factor loadings are significant and in the expected direction.

Structural Model

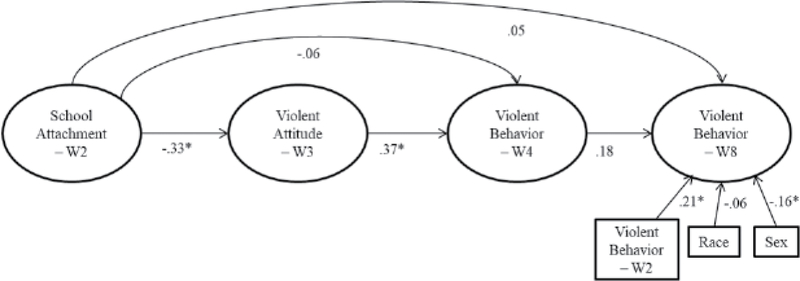

Results of the final structural model analysis controlling for sex, race, and violent behavior at Wave 2 provided acceptable fit to the data, χ2(282, N = 562) = 626.87, p < .01, and with NFI = 0.846, CFI = 0.908, RMSEA = 0.047, within 90% CI. Results are depicted in Figure 1 and Table 2. School attachment has an indirect effect on violent behavior at Wave 4 (β = −.12, p = .001; 95% biased-corrected CI for indirect effects: [−.43, −.12]), but no indirect effect on violent behavior at Wave 8 (β = −.02, p =.01, 95% biased-corrected CI for indirect effects: [−.05, .01]).

Figure 1.

Structural equation model results of school attachment effects on violent behavior mediated by violent attitudes.

Note. All path coefficients are standardized.

*p < .05.

Table 2.

Results From Mediation Model Examining School Attachment, Violent Attitude, and Violent Behavior.

| Outcome | R2 | Predictor | Unstandardized [95% CI] | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect [95% CI] | Total Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violent attitude | .11 | School attachment | −.54 [−.86, −.33] | −.33 | ||

| Violent behavior (Wave 4) | .16 | School attachment | −.11 [−.35, .13] | −.06 | −.12 [−.43, −.12] | −.18 |

| Violent attitude | .42 [.26, .61] | .37 | ||||

| Violent behavior (Wave 8) | .17 | School attachment | .05 [−.07, .20] | .05 | −.02 [−.05, .01] | .21 |

| Violent attitude | .11 [.04, .20] | .18 | ||||

| Violent behavior (Wave 4) | .01 [.00, .24] | .18 |

Discussion

Our findings provide evidence that school attachment and violent attitudes during high school are associated with subsequent violent behavior at the end of the schooling period. Moreover, violent attitudes mediate the effect of school attachment on violent behavior, which reinforces the importance of school variables to prevent violent behavior in the future. This study adds to the literature providing more specific links among school variables aiming at adolescent well-being beyond the academic performance. The unique influence of the school setting upon violent behavior (Birnbaum et al., 2003; McEvoy & Welker, 2000) highlights the importance of school attachment in preventing violent behavior.

Our results support a social cognitive process, evidenced by the direct effect of violent attitudes on violent behavior. This is consistent with previous studies that demonstrated violent attitude is a risk predictor of later violent behavior (Ali, Swahn, & Sterling, 2011; Gudjonsson, Sigurdsson, Skaptadottir, & Helgadottir, 2011; Lösel & Farrington, 2012). A social cognitive approach defines violent attitudes as self-regulating beliefs, assimilated by observation, that guide various types of behavior. These beliefs are highly correlated with aggressive behavior (Huesmann & Guerra, 1997). Here we provide evidence on how those violent attitudes guide later violent behavior over time. Our work also builds on the literature incorporating the role of school attachment as a previous step in the development of violent attitudes and violent behavior, highlighting the key role of protective factors on the development of violent attitude. As pointed, school connectedness has a negative effect on violent attitude confirming this relationship.

School attachment can be defined by the level of involvement and the general positive attitudes of students toward their school (Hill & Werner, 2006; Libbey, 2004; O’Farrell & Morrison, 2003). School attachment measurements capture students’ level of engagement and their participation in academic and social activities, leading to better school adjustment and achievement providing the opportunity to establish significant relationships (Atwool, 1999; Marcus & Sanders-Reio, 2001; Somers & Gizzi, 2001). Studies demonstrate a positive relationship between school attachment and achievement (Bergin & Bergin, 2009; Bryan et al., 2012), and our results suggest that low levels of school attachment can also play a role in adolescent problem behavior including violence. The social control theory establishes that attachment is increased when students are rewarded for positive involvement in school (Hirchi, 1998), and our findings confirm the importance of school attachment on risk behaviors over time (Hawkins, Guo, Hill, Battin-Pearson, & Abbott, 2001). This school feature may offer alternatives to build more positive relationships within the context of schools. Indeed, a more positive student–teacher relationship can provide significant support for emotional development of students during their high school (Eccles & Roeser, 2010; Pianta, 1999).

Several studies (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Catalano et al., 2004; Fleming et al., 2010; K. L. Henry et al., 2012; Logan-Greene et al., 2011; Lösel & Farrington, 2012) highlight the important role of school personnel to improve student connections with the school and with their peers. Hence, prevention and intervention programs should focus on these variables aiming to prevent violent behavior, improving healthy development. Our study adds to the understanding of the role of schools in the prevention of violent behavior, confirming the importance of school attachment and the school attachment/violent attitude link as a mediating mechanism. Our findings support this notion, suggesting that subsequent violent behavior of students could be explained by the way they feel connected to their school. Subsequently, violent behavior may develop via violent attitudes. Our results also provide evidence for mechanisms described on the social development model that explain antisocial behavior among young individuals (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996) and reinforce the importance of protective school context factors strengthening bonding, and the role of normative beliefs and attitudes that guide later behavior.

Regarding the time line of events, we found that the effects of violent attitudes on violent behavior were manifested predominantly at the end of high school, suggesting these are consequences of the events occurred during adolescence at school. As an example, prospective longitudinal studies postulate a protective role of academic success against the negative effects of being a perpetrator of bullying on externalization of problem behaviors later in life (Ttofi, Bowes, Farrington, & Lösel, 2014). Here we provide evidence that emphasizes the role of school context, setting the stage for behavioral outcomes, some of these well past the school-ages for adolescents (Ttofi & Farrington, 2012).

Our results suggest that limited school attachment contributes to violent attitudes, and while this may not be the only or most significant contributor to forming violent attitudes, our results suggest that school attachment does play a role. Given that violent attitudes predict future violent behavior, anything school officials can do to help reduce the probability of violent behavior is likely to make our schools and communities safer. Our results suggest whatever educators can do to help students feel more attached to school may help contribute to reductions in violence through the effects attachment has on violent attitudes.

Evidently, several questions still persist and should be further addressed in future studies, particularly regarding the interaction of school attachment, violent attitudes, and violent behaviors. First of all, although we did not examine in this in our study, it is quite possible that relationships are different in males versus females. Indeed, in a previous analysis of our sample, we found attitudes toward the use of violence to solve problems during adolescence; these attitudes were associated with violent behavior in the adulthood in males but not in females (Stoddard, Heinze, Choe, & Zimmerman, 2015). Furthermore, future educational aspirations were indirectly associated with subsequent violent behavior also in males. In principle, we expect school connectedness to be a gender-neutral protective factor for males and females; however, exploring the effects of school attachment (or school connections) on later violent attitudes and behaviors may reveal the necessity for differential interventions on males and females. Indeed, future studies should explore variations in these relationships according to race and/or ethnicity, or geographic regions aiming to understand these differences. As pointed, our study population was mostly African Americans (81.34%), limiting the extent of our conclusions especially in terms of race. Undoubtedly, the elaboration of effective interventions requires an understanding and consideration of these differences. Finally, future studies that consider of the moderating effects of school attachment on the violent attitudes and behavior association may provide additional insights into the role that schools may play in reducing violent behavior.

Some limitations in our study must be taken into consideration before we can analyze the implications of our findings. First, although this was a longitudinal study, childhood data were not collected. In general, the bases for violent behavior may take shape very early in human life (Tremblay et al., 1992; Tremblay et al., 2004). Despite this, our study includes a developmental framework, adding to our understanding of violent behavior developed over time and into young adulthood. Future studies should explore the mechanisms that operate in childhood that may affect both school attachment and violent attitudes. Such studies may provide useful insights for primary prevention of violent behavior in adolescence and even forward in life. Second, our study did not discriminate among different types of violent behavior. Our dependent variable of the study is a general measure of violent behavior that does not account for weighting offenses based on being more minor behaviors (e.g., hitting someone) to more serious violent behaviors (e.g., hurting someone badly enough to require medical attention; Sweeten, Pyrooz, & Piquero, 2013). Distinguishing types of violent behavior may identify different paths for more serious versus less serious violent behavior. Although we focused on common elements of violence such as hitting someone and hurting people physically, future research that examines pathways for different types of violent behavior may help to determine whether school attachment has similar effects for various forms of violent behavior. A third limitation was our study population that consisted of a relatively narrow urban sample. Hence, the results may not be extrapolated to the general population within this age segment. Nevertheless, our findings may be particularly relevant for young individuals living in a high-violence context such as the city of Flint. Fourth, our school factors measurements were limited to school attachment. Although similar studies have not examined this factor and its relation with violent attitudes/behavior, other school context variables should be considered in future studies; these include measures of school climate and school satisfaction. Finally, the exclusion of students with emotional or developmental delays may have caused an underrepresentation of an increasingly large proportion of these students (13% of all students in 2014–2015; National Center for Education Statistics, 2017). In fact, students with disabilities are at disproportionate risk for experiencing victimization, low school engagement, and high dropout rates; these are all related to school attachment. Consequently, interventions designed to improve attachment as a prevention strategy may not apply equally to that particular population. Indeed, the examination of these mechanisms in learning or emotionally delayed populations may also be an important direction for future studies. Despite all these limitations, our study contributes to the understanding of violent behavior and adds to our knowledge on adolescent violence in several ways: First, it highlights the relevance of school attachment for preventing violence behavior over time. Second, the effect of school attachment on violent behavior can be explained by the development of violent attitudes during high school. Third, we establish that the effect of school attachment and violent attitudes seems to remain stable during early adulthood. Finally, the school setting can become an important context for the prevention of violent behavior, in that school personnel can develop positive ways to solve problems and prevent the development of attitudes that lead to violent behavior. Thus, the study supports the notion that interventions designed to promote school importance and enhance school experiences may help reduce both adolescent and young adult violent behavior by eliminating attitudes that support violence as a problem-solving strategy.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Biographies

Jorge J. Varela. Ph.D., in Education and Psychology, University of Michigan. Assitant professor and researcher at the Center for Research and Improvement of Education (CIME), Universidad del Desarrollo, Chile.

Marc A. Zimmerman. Ph.D., Psychology, Personality, and Social Ecology, University of Illinois. Marshall H. Becker Collegiate Professor of Public Health, University of Michigan. Director of the Prevention Research Center of Michigan and the Youth Violence Prevention Center.

Allison M. Ryan. Ph.D., Combined Program in Education and Psychology, University of Michigan. Professor, School of Education, University of Michigan. Chair, Combined Program in Education and Psychology.

Sarah A. Stoddard, Ph.D., University of Minnesota. Assistant Professor University of Michigan School of Nursing.

Justin E. Heinze, Ph.D., Educational Psychology, University of Illinois-Chicago. Assistant Professor, Health Behavior & Health Education, University of Michigan.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ali B, Swahn MH, & Sterling KL (2011). Attitudes about violence and involvement in peer violence among youth: Findings from a high-risk community. Journal of Urban Health, 88, 1158–1174. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9601-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, & Bushman BJ (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 27–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Bushman BJ, & Anderson BCA (2001). Effects of violent video games on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: A meta-analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychological Science, 12, 353–359. doi: 10.2307/40063648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L, Walsh E, Trzesniewski K, Newcombe R, Caspi A, & Moffitt TE (2006). Bullying victimization uniquely contributes to adjustment problems in young children: A nationally representative cohort study. Pediatrics, 118, 130–138. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwool N (1999). Attachment in the school setting. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 34, 309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benbenishty R, & Astor RA (2005). School violence in context: Culture, neighborhood, family, school, and gender New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bergin C, & Bergin D (2009). Attachment in the classroom. Educational Psychology Review, 21, 141–170. doi: 10.1007/s10648-009-9104-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bender D, & Lösel F (2011). Bullying at school as a predictor of delinquency, violence and other anti-social behaviour in adulthood. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 21(2), 99–106. 10.1002/cbm.799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L (1993). Aggression: It causes, consequences, and control New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum AS, Lytle LA, Hannan PJ, Murray DM, Perry CL, & Forster JL (2003). School functioning and violent behavior among young adolescents: A contextual analysis. Health Education Research, 18, 389–403. doi: 10.1093/her/cyf036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockenbrough KK, Cornell DG, & Loper AB (2002). Aggressive attitudes among victims of violence at school. Education and Treatment of Children, 25, 273–287. [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer KA, Fanti KA, & Henrich CC (2006). Schools, parents, and youth violence: A multilevel, ecological analysis. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 35, 504–514. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan J, Moore-thomas C, Gaenzle S, Kim J, Lin C, & Na G (2012). The effects of school bonding on high school seniors’ academic achievement. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90, 467–480. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM (2012). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, & Hawkins JD (1996). The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In Hawkins JD (Ed.), Delinquency and crime: Current theories (pp. 149–197). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Oesterle S, Fleming CB, & Hawkins JD (2004). The importance of bonding to school for healthy development: Findings from the Social Development Research Group. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 252–261. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08281.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung-Do JJ, Goebert DA, Hamagani F, Chang JY, & Hishinuma ES (2015). Understanding the role of school connectedness and its association with violent attitudes and behaviors among an ethnically diverse sample of youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32, 1421–1446. doi: 10.1177/0886260515588923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen T, & Mayeux L (2004). From censure to reinforcement: Developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Development, 75, 147–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00660.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham NJ (2007). Level of bonding to school and perception of the school environment by bullies, victims, and bully victims. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 27(4), 457–478. 10.1177/0272431607302940 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dessel A (2010). Prejudice in schools: Promotion of an inclusive culture and climate. Education and Urban Society, 42, 407–429. doi: 10.1177/0013124510361852 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, & Roeser RW (2010). An ecological view of schools and development. In Meece JL & Eccles JS (Eds.), Handbook of research on schools, schooling, and human development (pp. 6–21). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer TW, Irvin MJ, Motoca LM, Leung M-C, Hutchins BC, Brooks DS, & Hall CM (2015). Externalizing and internalizing behavior problems, peer affiliations, and bullying involvement across the transition to middle school. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 23, 3–16. doi: 10.1177/1063426613491286 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, & Ttofi MM (2011). Bullying as a predictor of offending, violence and later life outcomes. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 21, 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey A, Ruchkin V, Martin A, & Schwab-Stone M (2009). Adolescents in transition: School and family characteristics in the development of violent behaviors entering high school. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 40, 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10578-008-0105-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong M, & Morrison G (2000). The school in school violence: Definitions and facts. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 8, 71–82. doi: 10.1177/106342660000800203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gellman RA, & Delucia-Waack JL (2006). Predicting school violence: A comparison of violent and nonviolent male students on attitudes toward violence, exposure level to violence, and PTSD symptomatology. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 591–598. doi: 10.1002/pits.20172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron BP, Williams KR, & Guerra NG (2011). An analysis of bullying among students within schools: Estimating the effects of individual normative beliefs, self-esteem, and school climate. Journal of School Violence, 10, 150–164. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2010.539166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gudjonsson G, Sigurdsson JF, Skaptadottir SL, & Helgadottir Þ (2011). The relationship of violent attitudes with self-reported offending and antisocial personality traits. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 22, 371–380. doi: 10.1080/14789949.2011.562913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Huesmann LR, & Spindler A (2003). Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children. Child Development, 74, 1561–1576. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haegerich TM, & Dahlberg LL (2011). Violence as a public health risk. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 5, 392–406. doi: 10.1177/1559827611409127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Guo J, Hill KG, Battin-Pearson S, & Abbott RD (2001). Long-term effects of the Seattle social development intervention on school bonding trajectories. Applied Developmental Science, 5, 225–236. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0504_04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henry D, Guerra N, Huesmann R, Tolan P, VanAcker R, & Eron L (2000). Normative influences on aggression in urban elementary school classrooms. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28(1), 59–81. doi: 10.1023/a:1005142429725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Knight KE, & Thornberry TP (2012). School disengagement as a predictor of dropout, delinquency, and problem substance use during adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 156–166. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9665-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill LG, & Werner NE (2006). Affiliative motivation, school attachment, and aggression in school. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 231–246. doi: 10.1002/pits.20140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T (1998). A control theory of delinquency. In Williams FP & McShane MD (Eds.), Criminology theory: Selected classic readings (pp. 289–305). Cincinnati, OH: Anderson Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hong JS, & Espelage DL (2012). A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: An ecological system analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17, 311–322. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR (1988). An information processing model for the development of aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 14, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR, & Guerra NG (1997). Children’s normative beliefs about aggression and aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 408–419. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.2.408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd NM, Hussain S, & Bradshaw CP (2018). School disorder, school connectedness, and psychosocial outcomes: Moderation by a supportive figure in the school. Youth & Society, 50(3), 328–350. doi: 10.1177/0044118X15598029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Catalano R, Haggerty KP, & Abbott RD (2011). Bullying at elementary school and problem in young adulthood: A study of bullying, violence and substance use from age 11 to age 21. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 21, 136–144. doi: 10.1002/cbm.804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Leventhal B, Koh Y, Hubbard A, & Boyce T (2006). School bullying and youth violence: Causes or consequences of psychopathologic behavior? Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 1035–1041. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling New York, NY: Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, & Zwi AB (2002). The world report on violence and health. The Lancet, 360, 1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM (2006). Developmental science, developmental systems, and contemporary theories of human development. In Lerner RA (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 1–17). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Libbey HP (2004). Measuring student relationships to school: Attachment, bonding, connectedness, and engagement. The Journal of School Health, 74, 274–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08284.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan-Greene P, Nurius P, Herting J, Hooven C, Walsh E, & Thompson E (2011). Multi-domain risk and protective factor predictors of violent behavior among at-risk youth. Journal of Youth Studies, 14, 413–429. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2010.538044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lösel F, & Farrington DP (2012). Direct protective and buffering protective factors in the development of youth violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(2, Suppl. 1), S8–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics (2017). The condition of education, 2017 Retrieved March 1, 2017, from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2017/2017144.pdf

- Maddox SJ, & Prinz RJ (2003). School bonding in children and adolescents: Conceptualization, assessment, and associated variables. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6, 31–49. doi: 10.1023/A:1022214022478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus RF, & Sanders-Reio J (2001). The influence of attachment on school completion. School Psychology Quarterly, 16, 427–444. doi: 10.1521/scpq.16.4.427.19894 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy A, & Welker R (2000). Antisocial behavior, academic failure, and school climate: A critical review. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 8, 130–140. doi: 10.1177/106342660000800301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mesch GS, Fishman G, & Eisikovits Z (2003). Attitudes supporting violence and aggressive behavior among adolescents in Israel: The role of family and peers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18, 1132–1148. doi: 10.1177/0886260503255552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Adams N, & Conner BT (2008). School violence: Bullying behaviors and the psychosocial school environment in middle schools. Children & Schools, 30, 211–221. doi: 10.1093/cs/30.4.211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell SL, & Morrison GM (2003). A factor analysis exploring school bonding and related constructs among upper elementary students. The California School Psychologist, 8, 53–72. doi: 10.1007/BF03340896 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC (1999). Enhancing relationships between children and teachers Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Renda J, Vassallo S, & Edwards B (2011). Bullying in early adolescence and its association with anti-social behaviour, criminality and violence 6 and 10 years later. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 21, 117–127. doi: 10.1002/cbm.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DC, & Sandhu DS (2004). Toward a positive perspective on violence prevention in schools: Building connections. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82, 287–293. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00312.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Somers C, & Gizzi T (2001). Predicting adolescents risky behaviours: The influence of future orientation, school involvement, and school attachment. Adolescent & Family Health, 2(1), 3–11. doi: 10.1177/1063426613491286 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spaccarelli S, Coatsworth JD, & Bowden BS (1995). Exposure to serious family violence among incarcerated boys: Its association with violent offending and potential mediating variables. Violence and Victims, 10, 163–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard SA, Heinze JE, Choe DE, & Zimmerman MA (2015). Predicting violent behavior: The role of violence exposure and future educational aspirations during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 44, 191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suris A, Lind L, Emmett G, Borman PD, Kashner M, & Barratt ES (2004). Measures of aggressive behavior: Overview of clinical and research instruments. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9, 165–227. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00012-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeten G, Pyrooz DC, & Piquero AR (2013). Disengaging from gangs and desistance from crime. Justice Quarterly, 30, 469–500. doi: 10.1080/07418825.2012.723033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa A, Cohen J, Guffey S, & Higgins-D’Alessandro A (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of Educational Research, 83, 357–385. doi: 10.3102/0034654313483907 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan P (2007). Understanding violence. In Flannery D, Vazsonyi A, & Waldman I (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of violent behavior and aggression (pp. 5–18). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE, Masse B, Perron D, Leblanc M, Schwartzman AE, & Ledingham JE (1992). Early disruptive behavior, poor school achievement, delinquent behavior, and delinquent personality: Longitudinal analyses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 64–72. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.60.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE, Nagin DS, Séguin JR, Zoccolillo M, Zelazo PD, Boivin M, … Japel C (2004). Physical aggression during early childhood: Trajectories and predictors. Pediatrics, 114, e43–e50. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi MM, Bowes L, Farrington DP, & Lösel F (2014). Protective factors interrupting the continuity from school bullying to later internalizing and externalizing problems: A systematic review of prospective longitudinal studies. Journal of School Violence, 13, 5–38. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2013.857345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi MM, & Farrington DP (2012). Risk and protective factors, longitudinal research, and bullying prevention. New Directions for Youth Development, (133), 85–98. 10.1002/yd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ttofi MM, Farrington DP, & Lösel F (2012). School bullying as a predictor of violence later in life: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective longitudinal studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17, 405–418. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]