Abstract

Transdifferentiation is a complete and stable change in cell identity that serves as an alternative to stem-cell-mediated organ regeneration. In adult mammals, findings of transdifferentiation have been limited to the replenishment of cells lost from preexisting structures, i.e., in the presence of a fully developed scaffold and niche1. Here we show that transdifferentiation of hepatocytes in the liver can build a structure that failed to form in development—the biliary system in mice that mimic the hepatic phenotype of human Alagille syndrome (ALGS)2. In these mice, hepatocytes convert into mature cholangiocytes and form bile ducts that are effective in draining bile and persist after the cholestatic liver injury is reversed, consistent with transdifferentiation. These findings redefine hepatocyte plasticity, which appeared to be limited to metaplasia, i.e., incomplete and transient biliary differentiation as an adaptation to cell injury, based on previous studies in mice with a fully developed biliary system3–6. We show that, in contrast to bile duct development7–9, de novo bile duct formation by hepatocyte transdifferentiation is independent of NOTCH signaling. We identify TGFβ signaling as the driver of this compensatory mechanism and show that it is active in some patients with ALGS. We also show that TGFβ signaling can be targeted to enhance the formation of the biliary system from hepatocytes, and that the transdifferentiation-inducing signals and remodeling capacity of the bile-duct-deficient liver can be harnessed with transplanted hepatocytes. Our results define the regenerative potential of mammalian transdifferentiation and reveal opportunities for therapy of ALGS and other cholestatic liver diseases.

In regenerating organs of adult mammals, differentiated cells can replenish other types of differentiated cells by transdifferentiation, as in the pancreatic islet10, gastric gland11, lung alveolus12 and intestinal crypt13. Whether mammalian transdifferentiation can build these or other structures de novo is unknown. In the liver, hepatocytes can undergo biliary differentiation to form reactive ductules both in humans14–17 and animals with cholestatic liver injury3–6,18–21. However, hepatocyte-derived biliary cells exhibit incomplete biliary and residual hepatocyte differentiation, i.e., are not mature cholangiocytes, and revert back to their original identity after the injury is reversed3–6. Moreover, hepatocyte-derived ductules do not contribute to bile drainage5. These findings are consistent with metaplasia, but not transdifferentiation, and call into question the functional significance of hepatocyte plasticity. However, all studies of hepatocyte plasticity published to date used animals with a fully developed biliary system in which residual cholangiocytes are available to regenerate injured bile ducts, likely leading to insufficient pressure for transdifferentiation. To determine the full extent of hepatocyte plasticity, we used mice lacking the intrahepatic biliary system.

Specifically, we used mice that mimic the hepatic phenotype of ALGS—a human disease caused by impaired NOTCH signaling22–24—generated by deletion of floxed alleles of the NOTCH signaling effector RBPJ and, to prevent compensation25, the transcription factor HNF6 (also known as ONECUT1) in embryonic liver progenitors using Cre expressed from an albumin promoter (Alb)2. These Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice are severely cholestatic because they lack peripheral bile ducts (pBDs), the branches of the intrahepatic biliary tree, at birth; however, >90% of the mice survive and form pBDs and a functional biliary tree by postnatal day (P) 12026 (Fig. 1a). Although Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice have hilar bile ducts (hBDs), the trunk of the biliary tree, we hypothesized that the new pBDs originate from hepatocytes because the livers of Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice contain hybrid cells expressing hepatocyte and biliary markers2,26. To test this hypothesis, we developed Cre-independent hepatocyte fate tracing. For this, we activated the Flp-reporter GFP gene in R26ZG+/+ mice specifically in hepatocytes by intravenous injection of an adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 8 vector expressing Flp from the transthyretin (Ttr) promoter (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1a–g).

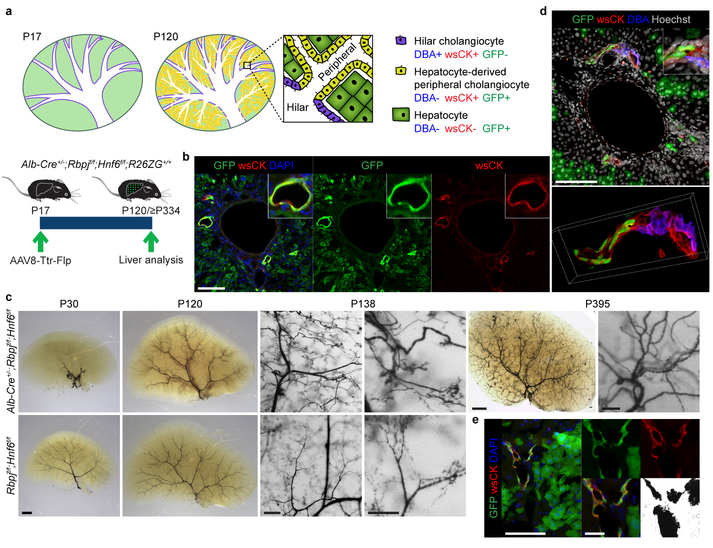

Figure 1: Hepatocytes can convert into peripheral cholangiocytes and form pBDs contiguous with preexisting hBDs.

a, De novo pBD formation and hepatocyte fate tracing in Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice. Cells identified by dolichos biflorus agglutinin (DBA) lectin labeling and wide-spectrum (ws) cytokeratin (CK) and GFP immunofluorescence (IF). b, IF of hepatocyte-fate-traced P120 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mouse liver (n=7). c, Biliary tree visualized by retrograde ink injection into the common bile duct of P30 (n=6), P120-P138 (n=6) and ≥P334 (n=6) Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f and P30 (n=3) and P120-P138 (n=5) Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice. d, Maximum projection (top) and 3D reconstruction (bottom) of z-stack image of hepatocyte-fate-traced P120 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mouse liver (n=2). e, IF and brightfield of hepatocyte-fate-traced P468 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mouse liver after retrograde ink injection into the common bile duct (≥P334, n=3). Scale bars, 2 mm (c, P30, P395 left), 500 μm (c, P138 left), 250 μm (c, P138 right), 100 μm (b, c, P395 right, d, e, left), 25 μm (e, middle).

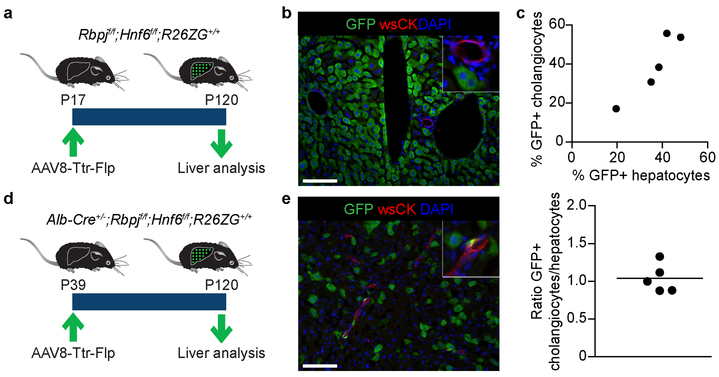

To trace hepatocytes during pBD formation, we intravenously injected Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice with AAV8-Ttr-Flp at P17, i.e., before cells expressing biliary markers emerge in the liver periphery2,26. At P120, the newly formed pBDs—identified by wsCK IF—were GFP positive, indicating hepatocyte origin (Fig. 1a, b). In contrast, pBDs that formed normally during liver development in Cre-negative littermates were GFP negative (Extended Data Fig. 2a, b). In many pBDs of Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice all cells were GFP positive, while the overall labeling efficiency of peripheral cholangiocytes was 39.2 ± 7.2% (mean ± SEM); however, this number correlated well with the hepatocyte labeling efficiency (36.6 ± 4.8%; paired 2-sided Student’s t-test; P=0.48) (Extended Data Fig. 2c), indicating that all peripheral cholangiocytes originated from hepatocytes. We also observed hepatocyte-derived peripheral cholangiocytes in mice in which hepatocytes were labeled after weaning (P39) (Extended Data Fig. 2d, e). These results show that hepatocytes can form pBDs de novo.

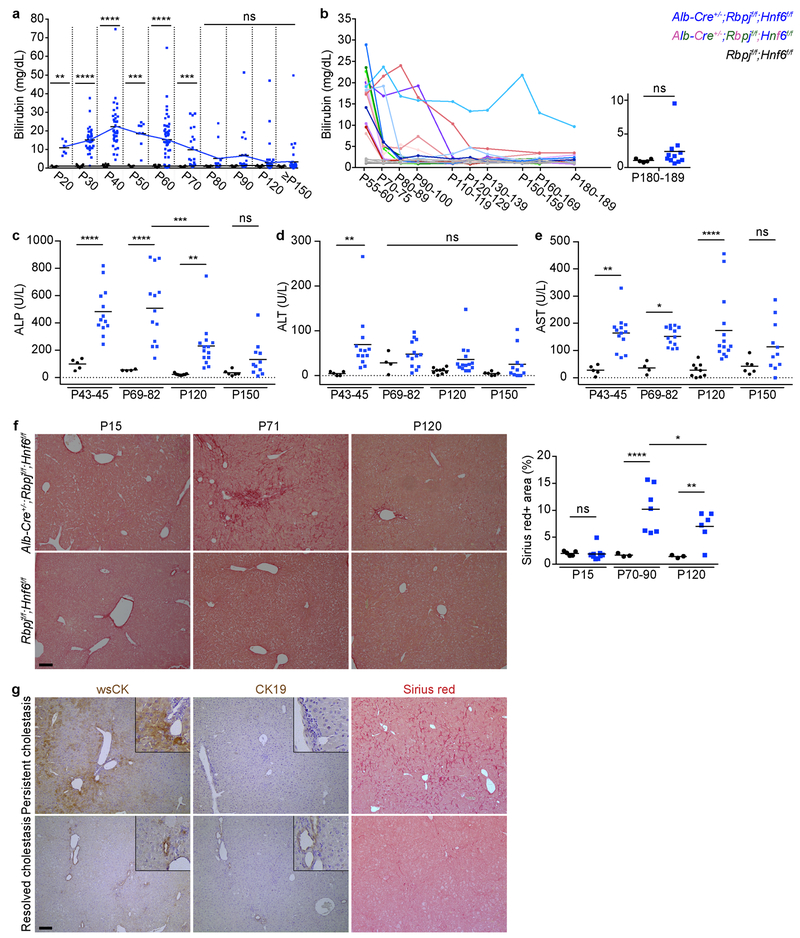

To investigate the function of the hepatocyte-derived pBDs (HpBDs), we determined if they are contiguous with the extrahepatic biliary system. At P30, retrograde ink injection into the common bile duct filled only hBDs, reflecting a severely truncated biliary tree lacking pBDs; however, ink injection at ≥P120 revealed a biliary tree of normal dimensions, demonstrating that HpBDs are connected to and patent with hBDs (Fig. 1c). 3D reconstruction of confocal imaging confirmed that HpBDs form contiguous lumens with DBA-labeled hBDs (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Video 1). Accordingly, HpBDs were effective in draining bile, as evidenced by normalization of serum markers of cholestasis (total bilirubin and ALP; Extended Data Fig. 3a–c) and hepatocyte injury (ALT and AST; Extended Data Fig. 3d, e) and resolution of cholestasis-induced liver fibrosis (Sirius-red staining; Extended Data Fig. 3f). A few mice that continued to have elevated serum total bilirubin and liver fibrosis showed abundant wsCK-positive hepatocytes but no HpBDs (Extended Data Fig. 3a, b, g). In contrast to the transient hepatocyte-derived ductules observed in other mouse models of cholestatic liver injury3–6, HpBDs were stable beyond the time when cholestasis and liver injury were resolved and were maintained for life (≥P334) (Fig. 1c, e). These results show that HpBDs provide normal and stable biliary function.

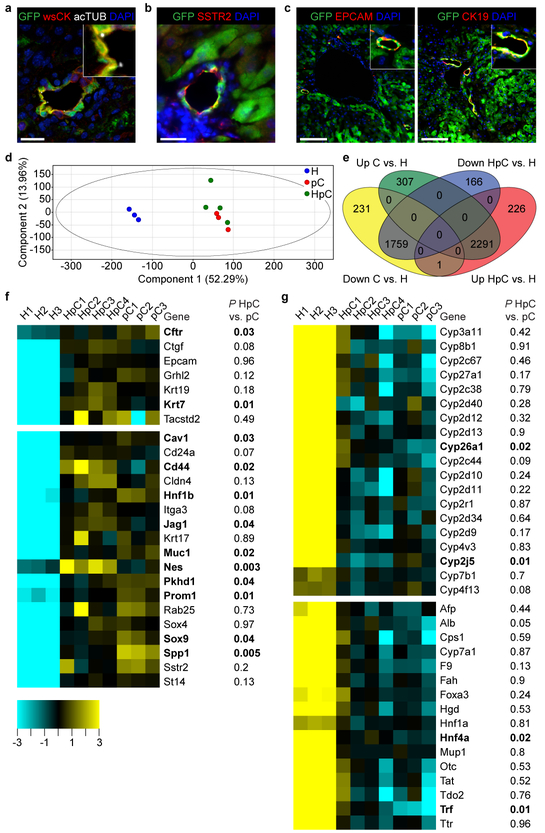

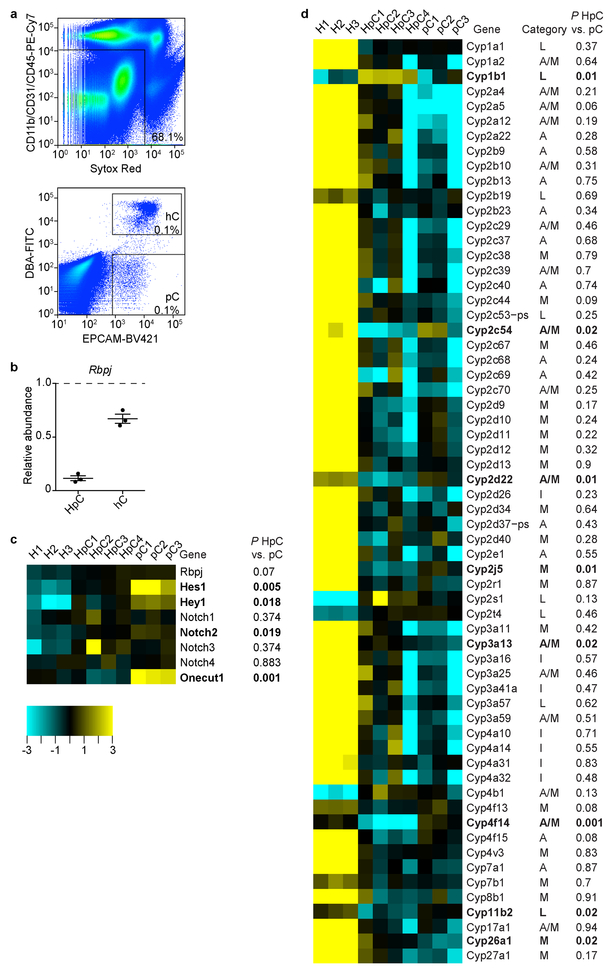

We also investigated the authenticity and maturity of the cholangiocytes forming the HpBDs. The cells displayed acetylated tubulin (acTUB)-marked primary cilia (Fig. 2a), indicating a switch from hepatocyte to biliary fate19, and somatostatin receptor 2 (SSTR2) (Fig. 2b), a marker of biliary function27. They also expressed the mature biliary markers EPCAM and CK19 (Fig. 2c), which are lacking or expressed at low levels in hepatocyte-derived metaplastic biliary cells3,5. To substantiate these results, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on hepatocyte-derived peripheral cholangiocytes isolated as EPCAM-positive DBA-negative cells by FACS from >P115 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Rbpj and Hnf6 were deleted in these cells (Extended Data Fig. 4b, c), which was expected because Alb-Cre is active in embryonic liver progenitors before they commit to hepatocyte or biliary fate2,9. Principal-component analysis showed that hepatocyte-derived peripheral cholangiocytes cluster closely with normal peripheral cholangiocytes isolated from Cre-negative littermates, but not with parental hepatocytes (Fig. 2d, e and Supplementary Table 1). Accordingly, hepatocyte-derived peripheral cholangiocytes expressed normal levels of mature biliary markers that are virtually undetectable in 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC) diet-induced hepatocyte-derived metaplastic biliary cells3, except for CFTR, which is less enriched in cholangiocytes than the other markers (Fig. 2f). Hepatocyte-derived peripheral cholangiocytes also expressed other commonly used markers of biliary differentiation3,5,20,25,27,28 at normal or near-normal levels (Fig. 2f), and showed virtually no memory of hepatocyte differentiation3,29,30 (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 4d). These results show that hepatocyte-derived peripheral cholangiocytes are authentic and mature peripheral cholangiocytes.

Figure 2: Hepatocyte-derived peripheral cholangiocytes are equivalent to normal mature peripheral cholangiocytes.

a-c, IF of hepatocyte-fate-traced P120 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mouse liver (n=3 each). Scale bars, 100 μm (c), 20 μm (a, b). d-g, RNA-seq analysis of normal peripheral cholangiocytes (pC, n=3 mice), hepatocyte-derived peripheral cholangiocytes (HpC, n=4 mice) and RBPJ- and HNF6-deficient hepatocytes (H, n=3 mice). Principal-component analysis (d). Venn diagram showing number of genes significantly differentially up- and down-regulated in pC or HpC vs. H (e). Heatmaps of genes reflecting cholangiocyte differentiation, including genes lacking in DDC diet-induced hepatocyte-derived metaplastic biliary cells (top) and other marker genes (bottom) (f). Heatmaps of genes reflecting hepatocyte differentiation, including all differentially expressed CYP genes enriched in adult mouse liver (top) and other marker genes (bottom) (g). 1-way ANOVA, FDR-corrected P<0.05; fold change > 3 (e-g). 2-sided Student’s t-test; bold genes P<0.05 for HpC vs. pC (f, g).

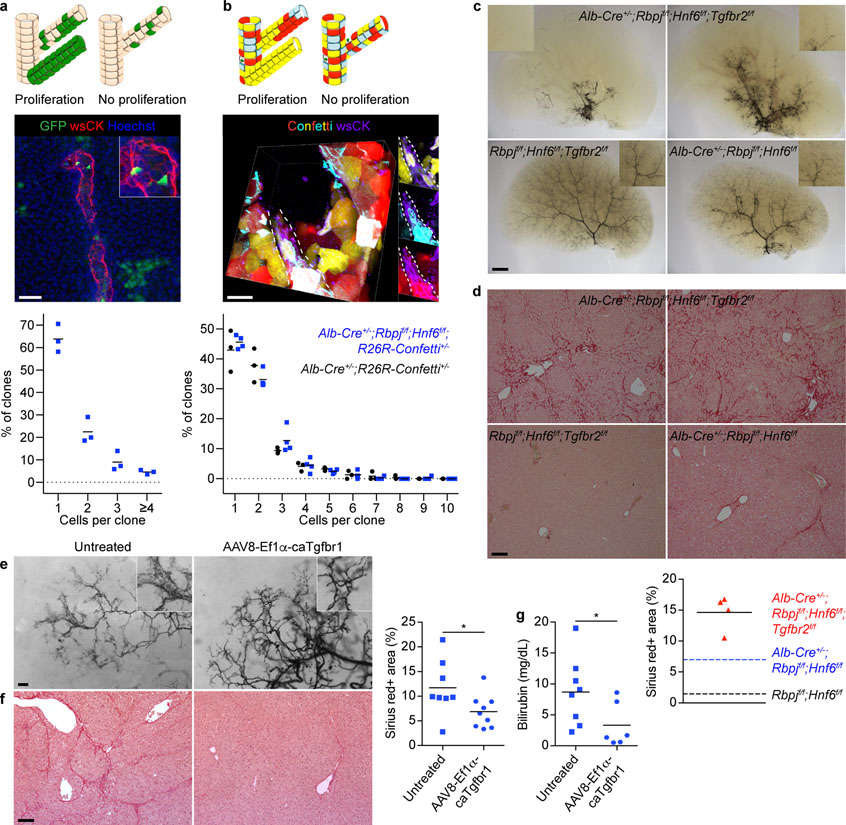

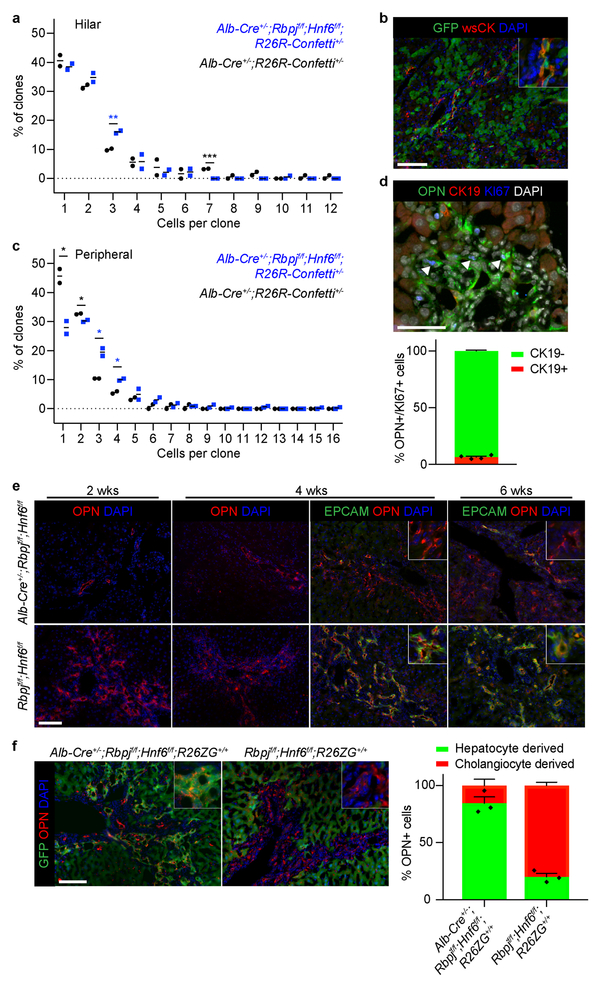

Next, we investigated the contribution of proliferation to HpBD formation, i.e., whether a few hepatocytes proliferate extensively after transdifferentiation, or whether many hepatocytes transdifferentiate. For this, we measured clonal expansion in HpBDs by sparsely labeling hepatocytes in Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice with low-dose AAV8-Ttr-Flp at P18 and quantifying the cells in GFP-positive clones at P120 (Fig. 3a). Surprisingly, we found only 1.56 ± 0.05 cells/clone in HpBDs, with 1-cell clones accounting for 63.8 ± 3.6% of clones. To exclude that the nonintegrating AAV vector missed proliferating hepatocytes, we analyzed clone size in Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26R-Confetti+/− mice in which hepatocytes and hilar cholangiocytes are stochastically labeled with 1 of 4 fluorescent proteins (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Video 2). We found 1.91 ± 0.06 cells/clone and 45.6 ± 1.1% 1-cell clones in HpBDs at P150. In addition, the number of cells per clone in hBDs was similar between these mice and Alb-Cre+/−;R26R-Confetti+/− control mice at P90 (2.08 ± 0.08 and 2.41 ± 0.01; 2-sided Student’s t-test; P=0.060) (Extended Data Fig. 5a). These results show that HpBDs are polyclonal, i.e., form with little proliferation, and confirm that hilar cholangiocytes do not contribute to HpBD formation.

Figure 3: HpBD formation entails little proliferation and is driven by TGFβ signaling.

a, Possible outcomes, maximum projection image and size distribution of clones in hepatocyte-fate-traced P120 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice (n=3). b, Possible outcomes, image stack volume projection and size distribution of clones in P150 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26R-Confetti+/− (n=4) and Alb-Cre+/−;R26R-Confetti+/− (n=3) mice. c, Ink visualization of biliary tree of >P120 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;Tgfbr2f/f (n=16), Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;Tgfbr2f/f (n=4) and Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f (n=1) mice. d, Sirius-red staining with quantification in >P120 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;Tgfbr2f/f (n=4), Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;Tgfbr2f/f (n=2) and Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f (n=2) mice. Dotted lines represent the means of the indicated P120 mice from Extended Data Fig. 3f. e, f, Ink visualization of biliary tree and Sirius-red staining with quantification in P100 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice that did (n=9) or did not (n=8) receive AAV8-Ef1α-caTgfbr1. 2-sided Student’s t-test; *P=0.045. g, Serum total bilirubin in P36 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice that did (n=6) or did not (n=8) receive AAV8-Ef1α-caTgfbr1. 2-sided Welch’s t-test; *P=0.047. Measure of center is mean (a, b, d, f, g). Scale bars, 2 mm (c), 500 μm (e), 100 μm (d, f), 50 μm (a), 20 μm (b).

Unlike in HpBDs, we found significant proliferation in hepatocyte-derived reactive ductules, which are detectable in Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice during cholestasis (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Clonal analysis showed 2.70 ± 0.08 cells/clone in reactive ductules in P90 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26R-Confetti+/− mice, with more 3- and 4-cell clones than in pBDs in Alb-Cre+/−;R26R-Confetti+/− mice (Extended Data Fig. 5c). Because HpBDs form with little proliferation, we reasoned that these proliferating cells are hepatocyte-derived metaplastic biliary cells3–6. Indeed, we found that 93.51 ± 0.81% of the proliferating biliary cells identified by KI67 and osteopontin (OPN) IF in Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice near the peak of cholestasis (P54) were CK19 negative (Extended Data Fig. 5d).

We also investigated proliferation in established HpBDs by inducing cholestatic liver injury with DDC diet in >P120 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice. Reactive ductules formed 2 weeks later than in Cre-negative littermates and consisted mainly of OPN-positive EPCAM-negative cells, indicative of hepatocyte metaplasia (Extended Data Fig. 5e). Indeed, after feeding DDC diet to Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice in which hepatocyte fate tracing was induced at >P120, we found that 84.5 ± 5.6% of the cells in reactive ductules originated from hepatocytes, in contrast to 20.1 ± 3.0% in Cre-negative littermates (Extended Data Fig. 5f). These results confirm that NOTCH signaling is important for cholangiocyte proliferation31, which explains our finding of a limited role of proliferation in HpBD formation and underscores the authenticity of hepatocyte-derived peripheral cholangiocytes.

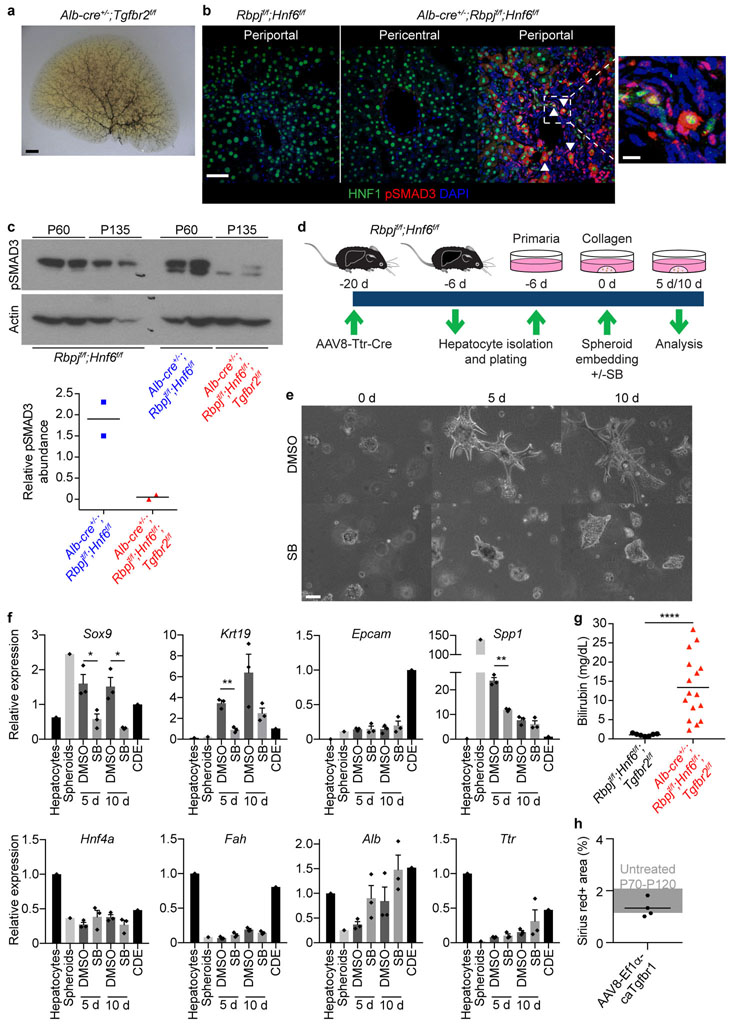

As illustrated by lack of pBDs in Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice (Fig. 1c), NOTCH signaling is needed for bile duct development7–9, raising the question of which signaling pathway drives HpBD formation in its absence (Extended Data Fig. 4b, c). We focused on TGFβ signaling because it promotes biliary differentiation and morphogenesis in development32, although it is not essential, as shown by development of a normal biliary tree in mice lacking the TGFβ type II receptor (TGFBR2) in embryonic liver progenitors (Extended Data Fig. 6a). We reasoned that TGFβ signaling is induced in hepatocytes of Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice because of the paradoxical role of HNF6 in liver development—it activates the biliary transcription factors HNF1β and SOX925,33, but inhibits TGFBR232,34. Indeed, gene ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis of our RNA-seq data suggested active TGFβ signaling in hepatocyte-derived peripheral cholangiocytes, but not in normal peripheral cholangiocytes (Supplementary Table 1, Down pC vs. HpC). Moreover, we found high levels of phosphorylated SMAD3 (pSMAD3) in nuclei of periportal HNF1-positive epithelial liver cells and in whole-liver nuclear extracts in Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice at P60 (Extended Data Fig. 6b, c).

We functionally validated these findings by showing that the TGFβ inhibitor SB-431542 blocks biliary differentiation and morphogenesis of hepatocytes lacking RBPJ and HNF6 in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 6d–f). Moreover, at >P120, HpBDs were still absent or severely truncated, and liver fibrosis persisted, in 14/16 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;Tgfbr2f/f mice that, like Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice, were cholestatic at P34–53 (Fig. 3c, d and Extended Data Fig. 6c, g).

These findings led us to investigate whether activating TGFβ signaling in hepatocytes enhances HpBD formation. We intravenously injected P19–24 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice with an AAV8 vector expressing constitutively active (ca) TGFBR1 from the elongation factor 1α (Ef1α) promoter. At P80–100, 9/11 treated mice had a mature hierarchical biliary network, whereas 9/9 untreated mice still had an immature homogeneous biliary network35 (Fig. 3e). Reflecting improved bile drainage, cholestasis and liver fibrosis resolved faster in treated mice (Fig. 3f, g). We excluded that AAV8-Ef1α-caTgfbr1 is fibrogenic in Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice (Extended Data Fig. 6h). These results identify TGFβ signaling as the driver of transdifferentiation and morphogenesis in HpBD formation.

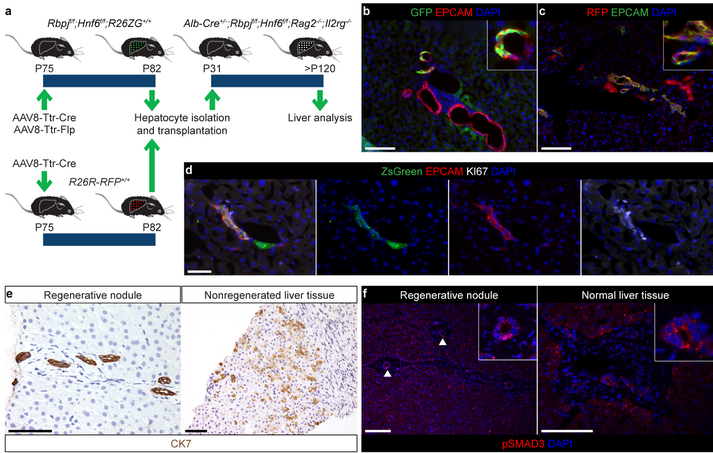

To exclude that transdifferentiation is limited to immature hepatocytes, we investigated whether adult hepatocytes can form HpBDs. To bypass potential adaptive processes in development, we deleted Rbpj and Hnf6 and activated GFP in hepatocytes of P75 Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice by co-injecting AAV8-Ttr-Cre and AAV8-Ttr-Flp and transplanted the cells 1 week later into P31 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;Rag2−/−;Il2rg−/− mice (Fig. 4a). After P120, we found donor hepatocyte-derived mature peripheral cholangiocytes in 5.2 ± 0.8% of the portal areas containing donor cells (Fig. 4b). We also transplanted NOTCH signaling-competent wildtype hepatocytes, which produced donor-derived HpBDs in 78.3 ± 13.9% of such portal areas because 31.6 ± 7.9% of the transplanted cells proliferated after transdifferentiation into cholangiocytes (Fig. 4a, c, d). These results show that adult hepatocytes, and transplanted hepatocytes, respond to the transdifferentiation-inducing and morphogenetic signals in the bile-duct-deficient liver and form HpBDs.

Figure 4: Clinical relevance and therapeutic potential of HpBD formation.

a, Experimental design for hepatocyte transplantation. b, IF of P127 mouse (n=5) transplanted with adult GFP-expressing RBPJ- and HNF6-deficient hepatocytes. c, IF of P152 mouse (n=4) transplanted with adult RFP-expressing hepatocytes. d, IF of liver of P72 mouse (n=2) transplanted at P43 with hepatocytes isolated from P287 Alb-Cre+/−;R26R-ZsGreen+/+ mouse. e, f, Immunohistochemistry and IF of ALGS (n=2) and normal (n=1) human livers. Arrowheads indicate nuclear pSMAD3 in pBDs. Scale bars, 100 μm (b, c, e, f), 50 μm (d).

To determine whether our findings are relevant for human ALGS, we obtained liver samples from 2 patients who developed regenerative nodules containing pBDs36 (Extended Data Table 1). The regenerative nodules contained CK7-positive pBDs, whereas nonregenerated liver tissue from the same patients showed abundant CK7-positive cells with hepatocyte morphology, indicative of metaplasia14–17 (Fig. 4e). To determine if TGFβ signaling is active in the new pBDs, we used pSMAD3 IF. We found nuclear localization of pSMAD3 in 56.1 ± 6.1% of the pBDs in regenerative nodules, but not in pBDs in normal human liver (Fig. 4f). These results suggest that the TGFβ-mediated mechanism of HpBD formation identified in Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice is also active in some patients with ALGS.

In conclusion, by showing that hepatocytes can convert into mature cholangiocytes and form a functional and stable biliary system, our findings establish that hepatocyte plasticity extends beyond metaplasia to transdifferentiation and provide the first example of mammalian transdifferentiation building an organ structure de novo. Although hilar cholangiocytes are present in our mice, they fail to expand, resulting in severe cholestatic liver injury and strong pressure for hepatocytes to transdifferentiate into peripheral cholangiocytes. Analogously, cholangiocytes transdifferentiate into hepatocytes only if hepatocyte proliferation is completely suppressed37. The failure of hilar cholangiocytes to proliferate is likely caused by high TGFβ signaling in the cholestatic liver38. Accordingly, we identified TGFβ signaling as the driver of hepatocyte transdifferentiation and HpBD formation in our mice and potentially also in patients with ALGS. Unlike for bile duct development7–9, NOTCH signaling is not needed. Using clinically established AAV vectors and hepatocyte transplantation we show that our findings are potentially translatable into therapies for ALGS and other diseases associated with lack of bile ducts.

Methods

Mice.

Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice (mixed background) were previously reported2,26. R26R-RFP+/+39 (C57BL/6) and R26NZG+/+40 (FVB) mice were used. Flp-reporter mice were generated by crossing R26NZG+/+ mice with EIIa-Cre+/+41 mice (C57BL/6) to remove the Cre-reporter element and then crossing out the EIIa-Cre. These R26ZG+/+ mice were crossed with Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice to generate Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice. R26R-Confetti+/+42 mice (C57BL/6) were crossed with Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice to generate Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26R-Confetti+/− mice. Tgfbr2f/f43 mice (C57BL/6) were crossed with Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice to generate Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;Tgfbr2f/f mice. Because Tgfbr2 (68.39 cM) and Hnf6 (41.93 cM) are both on chromosome 9, recombinants were generated at 0.1356 (35/258 mice) observed frequency (0.26 expected frequency). Different founder recombinants were intercrossed to generate Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;Tgfbr2f/f mice. R26R-ZsGreen+/+44 mice (C57BL/6) were crossed with Alb-Cre+/− mice to generate Alb-Cre+/−;R26R-ZsGreen+/+ mice. Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice were crossed with Rag2−/−45;Il2rg−/−46 mice (mixed background) to generate Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;Rag2−/−;Il2rg−/− mice. Male and female mice of the indicated age and genotype were chosen randomly for inclusion in experiments. The mouse used as a positive control for biliary gene expression was a C57BL/6 wildtype mouse fed choline-deficient diet (MP Biomedicals) and given 0.15% (w/v) ethionine (Sigma-Aldrich) in the drinking water (CDE diet) for 3 weeks. All mice were kept under barrier conditions. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at UCSF or CCHMC.

Adeno-associated virus.

The AAV-Ttr-Flp plasmid was generated by removing Cre from AAV-Ttr-Cre47 and replacing it with Flpo48 from pPGKFlpobpA (Addgene 13793); viruses were produced by Vector Biolabs and used at a high dose of 1–3 × 1012 vgs or low dose of 4 × 1011 vgs. The AAV-Ef1α-caTgfbr1 plasmid was built by VectorBuilder to contain the activating T204D49 mutation; virus was produced by Vector Biolabs and used at a dose of 1 × 1011 vgs. Titers were determined using qPCR. Viruses were delivered by tail vein injection in volumes ≤100 μL to prevent hydrodynamic effects.

Tissue collection.

Livers from Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+, R26R-Confetti+/− and transplanted mice were perfused with ice-cold PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Samples were cut into slices and fixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4°C. Livers from R26R-RFP+/+, Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f, Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f and Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice were fixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4°C. For thin sectioning, samples were moved to 30% sucrose overnight at 4°C to cryopreserve and then embedded in OCT (Tissue-Tek) or processed for paraffin embedding and sectioning. A Leica CM3050 S cryostat was used to cut 6 μm cryosections for staining and imaging. For 3D and sparse-labeling clonal analysis, liver samples were embedded in 4% agarose and sectioned on a Leica VT100 S vibratome. For clonal analysis in R26R-Confetti+/− mice, liver samples were cut into 1 mm slivers, immunostained, washed in PBS, equilibrated in 30% sucrose and embedded in OCT. The 1 mm slivers were then cryosectioned at 100 μm, stained with Hoechst and mounted in PBS for confocal imaging. For analysis of Flp-based hepatocyte fate tracing in R26ZG+/+ mice, liver samples were fixed in neutral-buffered formalin containing zinc (Z-Fix, Anatech), embedded in paraffin and sectioned to 5 μm.

Human liver tissue.

Explant samples from the regenerative nodule and nonregenerated liver tissue of a 3-year-old male patient with ALGS were previously described; regenerative nodule and nonregenerated liver tissue contained the same heterozygous JAG1 exon 1–26 deletion36. Samples were obtained with patient consent and approval from the Commission Cantonale d’Ethique de la Recherché CCER. Biopsy samples from the regenerative nodule and nonregenerated liver tissue of a 15-year-old male patient with ALGS caused by a heterozygous c.499T>A (p.W167R) JAG1 mutation and resection samples from a histologically normal region of the liver of a 35-year-old male undergoing surgery for metastasis of rectal adenocarcinoma were obtained with patient consent and approval from the UCSF Institutional Review Board.

Immunostaining and histology.

Cryosections were blocked in 10% normal serum and permeabilized in 0.3% Triton-X before staining with primary and secondary antibodies listed in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. Paraffin-embedded samples were deparaffinized and underwent antigen retrieval in sodium citrate buffer (Bio-Genex or Vector Labs) or Tris EDTA buffer (10mM Tris Base, 1mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 9.0) in a steamer or pressure cooker for 15 minutes before blocking and permeabilization. Thin sections were mounted in FluorSave (MilliporeSigma) or 50% glycerol. Vibratome sections were stained free-floating in 12-well dishes and cleared in Focus Clear (Cedarlane Laboratories) before being mounted in Mount Clear (Cedarlane Laboratories) for confocal imaging. All samples stained with anti-wsCK antibody underwent antigen retrieval in 100 mM Tris buffer (pH 9.5) at 55°C for 2 hours before blocking. Staining with anti-pSMAD3 antibody used a biotinylated secondary antibody followed by avidin/biotin-based peroxidase and tyramide amplification. Staining with anti-SSTR2 antibody used an HRP secondary antibody followed by tyramide-based amplification. M.O.M. Kit (Vector Laboratories) was used for antibodies raised in mice. DAPI or Hoechst was used to stain nuclear DNA. Chromogenic detection used an HRP secondary antibody followed by avidin/biotin-based peroxidase amplification and DAB substrate exposure. Sirius-red staining was performed on deparaffinized and rehydrated samples using a 0.1% Picrosirius-red solution (Dudley Corporation and Newcomer Supply) and 0.5% acetic acid water washes or was done at Peninsula Histopathology Laboratory.

Imaging.

Thin sections were imaged on an Olympus BX51 upright microscope and cultured cells were imaged on an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope using Openlab software (PerkinElmer). Chromogenic stains were imaged on a Leica DM 1000 LED. Fiji50 and/or Photoshop (Adobe) were used to process (brightness, contrast and gamma) and merge channels. Thick sections for 3D analysis of connectivity and clonal analysis were imaged on a Leica upright AOBS confocal microscope and processed and analyzed using Imaris (Bitplane) or Volocity (PerkinElmer) software. For R26R-Confetti+/− mouse and pSMAD3 analysis, images were acquired using a Nikon A1R GaAsP inverted SP confocal microscope and NIS elements software and processed and analyzed using Imaris software. Sirius-red-stained sections were imaged using a Cytation 5 cell imaging multi-mode reader (BioTek).

Ink injection.

A catheter was inserted in a retrograde fashion into the common bile duct of postmortem mice and waterproof ink (Higgins) was slowly injected. Left liver lobes were dehydrated in 1:1 methanol:water followed by 100% methanol. Ink was visualized by tissue clearing in 1:2 benzyl alcohol:benzyl benzoate (BABB) solution and imaged on a Leica M205A or Nikon SMZ800 stereoscope.

Cholangiocyte isolation.

Nonparenchymal liver cells were isolated from >P115 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f and Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice as previously described51. Cells were resuspended at 1 × 107 cells/mL in DMEM/2% FBS and blocked with Mouse Fc Block (BD Biosciences) for 30 minutes. Cells were incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (Supplementary Table 2) and DBA-FITC (Vector Laboratories) for 30 minutes, washed with cold DPBS 3 times and resuspended in DMEM/2% FBS. Sytox Red (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to label dead cells prior to sorting. Unstained and single-stained cells were used for compensation. Specificity of DBA binding was verified with a GalNAc (Sigma)-blocked control as previously described52. Cells were analyzed and sorted on a FACSAria III using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). From the CD11b–CD31–CD45– population, EPCAM+DBA– cells were collected as peripheral cholangiocytes and EPCAM+DBA+ as hilar cholangiocytes. FlowJo (FlowJo, LLC) was used to analyze data and generate charts. Cells were either sorted into DMEM/2% FBS, pelleted and snap frozen, or sorted directly into extraction buffer for RNA purification.

Hepatocyte isolation.

Hepatocytes were isolated from >P115 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice by 2-step collagenase (Worthington) perfusion followed by purification through a Percoll gradient. Cells were resuspended at 1 × 106 cells/100 μL in Hanks Buffer with 10% FBS and incubated with OC2–2F8 antibody (Supplementary Table 2) for 1 hour on ice. Cells were washed with cold DPBS 2 times and resuspended in Hanks/10% FBS. Fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibody (Supplementary Table 3) was added and cells were incubated for 30 minutes on ice followed by 2 washes with cold DPBS. Cells were blocked with 5% normal rat serum (Jackson Immuno) in Hanks Buffer for 10 minutes on ice. Cells were then incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (Supplementary Table 2) for 30 minutes on ice. Cells were then washed in cold DPBS 3 times and resuspended in Williams E medium/2% FBS. Sytox Red (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to label dead cells prior to sorting. Unstained and single-stained cells were used for compensation. Cells were analyzed and sorted on a FACSAria III using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). From the CD11b–CD31–CD45–EPCAM– population, OC2–2F8+ cells were collected as hepatocytes (Supplementary Fig. 2). Cells were either sorted into DMEM/2% FBS, pelleted and snap frozen, or sorted directly into extraction buffer for RNA purification.

Hepatocyte transplantation.

Hepatocytes were isolated from donor mice by 2-step collagenase perfusion followed by purification through a Percoll gradient. 1 × 106 viable cells were resuspended in 80–100 μl of Williams E Medium with glutamine. Transplantation was performed by transdermal intrasplenic injection of the cell suspension under isoflurane anesthesia.

DDC diet feeding.

Mice received PicoLab Mouse Diet 20, 5058 (LabDiet) with 0.1% 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC; Sigma-Aldrich) for the indicated durations.

qPCR and gene expression analysis.

Genomic DNA was isolated from cells using QIAamp DNA Micro Kit or DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen). RNA was extracted using Trizol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and purified by isopropanol precipitation (cells in collagen gel) or purified using RNAeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) (liver tissue). Reverse transcription was performed using qScript cDNA Supermix (Quanta Biosciences). qPCR was performed using SYBR green reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a ViiA 7 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reactions were performed in triplicate, and expression was normalized to an Rbpj (genotyping) or Gapdh (gene expression) reference and quantified using the ΔΔCt method. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

RNA-seq.

RNA was purified from FACS-isolated cells using PicoPure Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA quality was assessed using RNA 6000 Pico Kit on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent). Samples with RIN ≥ 7.7 and at least 15 ng of RNA were used to construct sequencing libraries using Clontech Low Input Library Prep Kit v2. Libraries were sequenced on a HiSeq 3000, 10 samples per lane, with single-end 50 bp reads. Raw reads were aligned to the mm10 mouse genome with annotations provided by UCSC using CobWEB, a proprietary Burrows-Wheeler Transform method. Reads per kb per million (RPKM) were calculated from aligned reads using the expectation-maximization algorithm. RPKM was thresholded at 1, log2 transformed, normalized using the DESeq algorithm and baselined to the median of all samples. Analyses were performed on transcripts with RPKM > 5 in all samples of at least 1 experimental condition (n=17,793 transcripts). These reasonably expressed transcripts were used in principle-component analysis. All transcripts with fold change > 3 in at least 1 of the 3 possible pairwise comparisons (n=6,464) were selected, and a 1-way ANOVA was performed to identify significantly differential genes with FDR-corrected P<0.05 (n=4,997). Venn diagrams were used to identify unique and shared gene signatures. Gene sets were submitted to ToppGene.cchmc.org for identification of pathway and biological process enrichments.

Western blot.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were generated from whole liver using previously described buffers with protease and phosphatase inhibitors53. Samples were run on SDS-PAGE 4–20% Tris-Glycine gradient gels, electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and probed with antibodies. Signals were detected by ECL Western blotting substrate (GE Healthcare). The membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-actin antibody to verify and normalize protein loading using densitometry. Quantification was performed using ImageJ software.

Serum chemistry.

Blood was collected from postmortem Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice and controls of ages P20 to ≥P150 and tested for serum total bilirubin (TecoDiagnostics) and ALP, ALT and AST (ADVIA XPT clinical chemistry system, Siemens). For serial bilirubin measurements, blood was collected by retro-orbital venipuncture and tested for total bilirubin every 2 weeks from P60 to P189 from 4 different litters. Blood was collected from Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;Tgfbr2f/f mice and controls by retro-orbital venipuncture and tested for serum total bilirubin (TecoDiagnostics). Blood was collected from Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice intravenously injected with AAV8-Ef1α-caTgfbr1 and controls by retro-orbital venipuncture and serum total bilirubin was measured as previously reported54 using a Synergy 2 microplate reader (BioTek). Serum absorbance at 540 nm was subtracted from serum absorbance at 450 nm. A linear trendline equation of serum absorbance vs. serum total bilirubin was determined by independently measuring absorbance and total bilirubin (TecoDiagnostics) of known cholestatic and noncholestatic serum samples. This equation was used to convert absorbance readings to serum total bilirubin levels.

In vitro conversion assay.

In vitro 3D culture of hepatocytes to induce biliary conversion was carried out as previously reported21 with the following modifications. Hepatocytes were isolated from 8–10-week-old Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice injected with 1 × 1012 vgs of AAV8-Ttr-Cre 2 weeks prior to delete Rbpj and Hnf6. Hepatocytes were isolated by 2-step collagenase perfusion followed by purification through a Percoll gradient, all in the absence of serum. Cells were grown on Primaria plates for 6 days to form spheroids. Spheroids were cultured in collagen gels (Cultrex Rat Collagen I, Lower Viscosity, Trevigen) in the presence of 10 μM SB-431542 (Selleckchem) or vehicle (DMSO). The medium was changed every other day.

Quantification and statistics.

For sparse-labeling clonal analysis, 8 liver regions from each of 3 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice were analyzed. GFP-positive cells in all clones within 100 μm-thick sections were manually counted using Imaris software for visualization. GFP-positive cells in direct contact were considered clones. Clones that extended to and potentially beyond the x, y or z boundaries were excluded. For clonal analysis in R26R-Confetti+/− mice, 30–40 μm z-stack images of wsCK-positive DBA-negative pBDs and wsCK-positive DBA-positive hBDs were visualized in 3D with Imaris software. The module Surfaces within Imaris was used to render a 3D surface created on an intensity value on a per channel basis. The rendered surface-per-channel was masked to the Hoechst nuclear stain. 3D pBD masks were used to manually count cells per clone. Multiple portal regions were analyzed for clones at P90 (14 and 17 per Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26R-Confetti+/− and 8 and 9 per Alb-Cre+/−;R26R-Confetti+/− mouse) and P150 (7–10 per Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26R-Confetti+/− and 8–10 per Alb-Cre+/−;R26R-Confetti+/− mouse). To determine labeling efficiencies in Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice, for each mouse, 20 random fields were analyzed for wsCK-positive DBA-negative peripheral cholangiocytes (~350 cells) and 5 random fields were analyzed for hepatocytes (~1,500 cells). For proliferation analysis, OPN-positive cells in 4 random portal fields from each of 4 mice were analyzed for KI67 and CK19 staining. For hepatocyte-fate-tracing analysis in DDC diet-fed mice, 10 random portal fields from 4 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ and 3 Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice were analyzed. For quantification in transplantation experiments, all portal areas with donor-derived cells in a section from at least 3 lobes per mouse were examined and scored for the presence or absence of donor hepatocyte-derived EPCAM-positive cholangiocytes. For human samples, 63 bile ducts between the 2 patient samples and 45 bile ducts in the control sample were scored for the presence of nuclear pSMAD3. For Sirius-red-staining quantification, liver samples were stained in batches and sections of whole lobes were imaged at equal exposure. Using Fiji software, a threshold was set for Sirius-red-positive area within each lobe and the percent of the total area that was Sirius red positive was measured and is reported. Charts were generated in Prism 6 or 7 (GraphPad). Researchers were not blinded when analyzing results. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Experiments were replicated independently once (Fig. 2a, b, d–g; Fig. 3a, b, d, g; Extended Data Fig. 1c–g; Extended Data Fig. 2c, e; Extended Data Fig. 3a–g; Extended Data Fig. 4b–d; Extended Data Fig. 5a, c, d, f; Extended Data Fig. 6c, g; Supplementary Table 1), at least twice (Fig. 1d, e; Fig. 2c; Fig. 3f; Fig. 4b–f; Extended Data Fig. 5b, e; Extended Data Fig. 6a, b, e, f, h; Supplementary Video 1) or at least thrice (Fig. 1b, c; Fig. 3c, e; Extended Data Fig. 2b; Extended Data Fig. 4a; Supplementary Video 2). No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size.

Data availability.

The Gene Expression Omnibus accession number for the RNA-seq data is GSE108315. Additional data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Extended Data

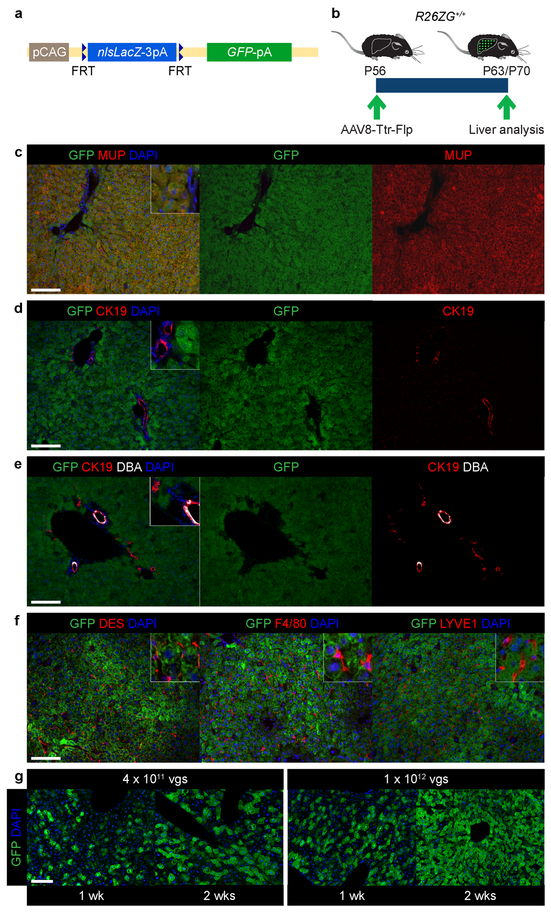

Extended Data Figure 1: Flp-based hepatocyte fate tracing.

a, R26ZG allele. b, Experimental design for establishing efficient, specific and constitutive labeling of hepatocytes in normal adult R26ZG+/+ mice. c-f, IF of R26ZG+/+ mouse liver (n=2) for GFP and the hepatocyte marker major urinary protein (MUP) (c), peripheral and hilar cholangiocyte marker CK19 (d, e), hilar-cholangiocyte-specific marker DBA (e), hepatic stellate cell marker desmin (DES), macrophage marker F4/80 and endothelial cell marker LYVE1 (f) 2 weeks (wks) after intravenous injection of 1 × 1012 viral genomes (vgs) of AAV8-Ttr-Flp. g, Reporter activation in R26ZG+/+ mice 1 and 2 weeks after intravenous injection of the indicated dose of AAV8-Ttr-Flp (n=1 for each dose and time point). Scale bars, 100 μm.

Extended Data Figure 2: Efficiency of hepatocyte fate tracing in mice born with or without pBDs.

a, b, Experimental design for hepatocyte fate tracing at P17 and IF at P120 in Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice (n=4). c, Correlation of GFP labeling efficiency between hepatocytes and peripheral cholangiocytes in hepatocyte-fate-traced P120 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice (n=5, top and bottom). Measure of center is mean. d, e, Experimental design for hepatocyte fate tracing at P39 and IF at P120 in Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mice (n=3). Scale bars, 100 μm.

Extended Data Figure 3: HpBDs relieve cholestasis and liver injury.

a, Serum total bilirubin levels in P20–29 (n=6), P30–39 (n=33), P40–49 (n=35), P50–59 (n=8), P60–69 (n=46), P70–79 (n=22), P80–89 (n=13), P90–119 (n=20), P120–149 (n=52) and ≥P150 (n=40) Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f and P20–29 (n=5), P30–39 (n=24), P40–49 (n=19), P50–59 (n=7), P60–69 (n=27), P70–79 (n=10), P80–89 (n=11), P90–119 (n=10), P120–149 (n=41) and ≥P150 (n=25) Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice. 2-sided Welch’s t-test; **P=0.0011 at P20–29, ****P=1.7E-13 at P30–39, ****P=8.2E-12 at P40–49, ***P=0.00019 at P50–59, ****P=8.4E-10 at P60–69, ***P=0.00055 at P70–79, nsP=0.090 at P80–89, nsP=0.050 at P90–119, nsP=0.052 at P120–149 and nsP=0.064 at ≥P150. b, Serial measurements of serum total bilirubin levels in Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f (n=14) and Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f (n=5) mice. 2-sided Welch’s t-test; nsP=0.11. c-e, Serum ALP, ALT and AST levels in P43–45 (n=13), P69–82 (n=13), P120 (n=14) and P150 (n=11) Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f and P43–45 (n=5), P69–82 (n=4), P120 (n=9) and P150 (n=6) Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice. 2-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test; ****P=0.000058 at P43–45, ****P=0.000019 at P69–82, **P=0.0064 at P120, nsP=0.22 at P150 and ***P=0.00010 at P120 vs. P69–82 (c); **P=0.0050 at P43–45, nsP=0.47 at P69–82, nsP=0.30 at P120 and nsP=0.47 at P150 (d); **P=0.0024 at P43–45, *P=0.015 at P69–82, ****P=0.000073 at P120 and nsP=0.061 at P150 (e). f, Sirius-red staining in P15 (n=9), P70–90 (n=7) and P120 (n=6) Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f and P15 (n=5), P70–90 (n=3) and P120 (n=3) Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice with quantification. 2-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test; nsP=0.94 at P15, ****P=0.000095 at P70–90, **P=0.0074 at P120 and *P=0.027 at P120 vs. P70–90. g, Immunohistochemistry and Sirius-red staining in P313 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice with persistent or resolved cholestasis (n=1 each). Measure of center is mean (a-f). Scale bars, 100 μm.

Extended Data Figure 4: Isolation and gene expression profiling of hepatocyte-derived peripheral cholangiocytes.

a, FACS gates for peripheral cholangiocyte (pC, EPCAM+DBA–) and hilar cholangiocyte (hC, EPCAM+DBA+) isolation from Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f and Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice. b, qPCR analysis of Rbpj floxed genomic DNA in hepatocyte-derived pC (HpC) and hC isolated from Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice relative to hepatocytes isolated from Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice (dashed line, n=3 each). Data were normalized to a downstream genomic region of Rbpj to control for gene copy number. Measure of center is mean ± SEM. c, d, RNA-seq analysis of normal pC (n=3 mice), HpC (n=4 mice) and RBPJ- and HNF6-deficient hepatocytes (H, n=3 mice). Heatmap of genes reflecting deletion of Rbpj and Hnf6 (Onecut1) (c). Rbpj mRNA is present in this knockout mouse as a truncated transcript that does not produce a functional protein26. Heatmap of all differentially expressed CYP genes distinguishing genes associated with mature (M), adolescent (A) and immature (I) hepatocyte differentiation or low expression in the liver (L)29 (d). 1-way ANOVA, FDR-corrected P<0.05; fold change > 3 (c, d, except Rbpj and Notch1–4). 2-sided Student’s t-test; bold genes P<0.05 for HpC vs. pC (c, d).

Extended Data Figure 5: Proliferation in HpBDs and reactive ductules.

a, Size distribution of wsCK-positive DBA-positive hilar cholangiocyte clones in P90 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26R-Confetti+/− (n=2) and Alb-Cre+/−;R26R-Confetti+/− (n=2) mouse livers. 2-sided Student’s t-test; **P=0.0079 for 3 cells and ***P=0.00092 for 7 cells. b, IF of reactive ductules in hepatocyte-fate-traced P32 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ mouse liver (n=3). c, Size distribution of wsCK-positive DBA-negative peripheral cholangiocyte clones in P90 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26R-Confetti+/− (n=2) and Alb-Cre+/−;R26R-Confetti+/− (n=2) mouse livers. 2-sided Student’s t-test; *P=0.032 for 1 cell, *P=0.024 for 2 cells, *P=0.020 for 3 cells and *P=0.014 for 4 cells. d, IF and breakdown of OPN-positive KI67-positive cells based on CK19 expression in P54 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mouse liver (n=4). Arrowheads indicate OPN-positive KI67-positive CK19-negative cells. e, IF of liver of >P120 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f and Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice after DDC diet feeding for 2 (n=1 each), 4 (n=3 each) and 6 (n=1 each) weeks (wks). f, IF of liver and breakdown of OPN-positive cells based on hepatocyte fate tracing in >P120 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ (n=4) and Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;R26ZG+/+ (n=3) mice fed DDC diet for 5 weeks starting 1 week after hepatocyte fate tracing was induced. Measure of center is mean (a, c, d, f) ± SEM (d, f). Scale bars, 100 μm (b, e, f), 50 μm (d).

Extended Data Figure 6: TGFβ signaling in hepatocyte transdifferentiation.

a, Ink visualization of biliary tree of P32 Alb-Cre+/−;Tgfbr2f/f mouse (n=2). b, IF of P60 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f and Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mouse livers (n=2 each). Arrowheads indicate pSMAD3-positive HNF1-positive nuclei. c, Western blot with quantification of pSMAD3 in nuclear extracts from Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f, Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f and Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;Tgfbr2f/f mouse livers (n=2 each). Source data are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. d-f, Experimental design (d) and results of analysis of the effect of TGFβ signaling on biliary differentiation of adult RBPJ- and HNF6-deficient hepatocytes in 3D culture. Phase-contrast images of RPBJ- and HNF6-deficient hepatocyte spheroids embedded in collagen gels and cultured in the presence or absence of the TGFβ inhibitor SB-431542 (SB) for the indicated number of days (d) (e). Relative expression levels of cholangiocyte and hepatocyte genes in freshly isolated hepatocytes and spheroids before and after embedding in collagen gels (f). Gene expression in the liver of a mouse fed choline-deficient ethionine-supplemented (CDE) diet was used as a positive control. Data are from 3 independent cultures per treatment in a representative experiment (n=2). 2-sided Welch’s t-test; *P=0.038 for Sox9 5 d, *P=0.044 for Sox9 10 d, **P=0.0034 for Krt19 5 d and **P=0.0071 for Spp1 5 d. g, Serum total bilirubin levels in P34–53 Alb-Cre+/−;Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;Tgfbr2f/f (n=16) and Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f;Tgfbr2f/f (n=7) mice. 2-sided Welch’s t-test; ****P=0.000024. h, Quantification of Sirius-red staining in P58–100 Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice after intravenous injection of AAV8-Ef1α-caTgfbr1 at P20 (n=4). Gray area represents the range of liver collagen in the indicated Rbpjf/f;Hnf6f/f mice from Extended Data Fig. 3f. Measure of center is mean (c, f, g, h) ± SEM (f). Scale bars, 2 mm (a), 100 μm (e), 50 μm (b), 10 μm (b, inset).

Extended Data Table 1:

Characterization of human subjects and samples.

| Human subject | Gender | ALGS genotype | ALGS phenotype | Age at liver analysis | Liver samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALGS patient | Male | Heterozygous JAG1 exon 1–26 deletion | Neonatal cholestasis, bile duct paucity, liver fibrosis, portal hypertension, hepatocellular carcinoma, liver transplantation; left pulmonary artery stenosis; butterfly vertebrae; facial features | 3 years | Regenerative nodule and nonregenerated tissue (segment 5 of right lobe and segment 8 of right lobe of explanted liver, respectively) |

| ALGS patient | Male | Heterozygous JAG1 exon 4 mutation (c.499T>A; p.W167R) | Failure to thrive; hepatomegaly, bile duct paucity, cholestasis, liver fibrosis; left pulmonary artery stenosis; facial features | 15 years | Regenerative nodule and nonregenerated tissue (biopsies of segment 3 of left liver lobe and segment 5 of right liver lobe, respectively) |

| Normal control | Male | Normal JAG1 and N0TCH2 sequences | None | 35 years | Histologically normal tissue (resection of segment 4 of left liver lobe for metastasis of rectal adenocarcinoma) |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors received the following support: H.W.: NIH R01 DK107553, CIRM DISC1–08792, NIH P30 DK26743. S.S.H.: NIH R01 DK078640, NIH R01 DK107553, NIH P30 DK078392. J.R.S.: NIH T32 DK060414, A. P. Giannini Foundation. S.N.T.K. and B.Y.H.: NIH T32 GM008568. M.R.: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft RE 3749/1–1. F.C.: NIH T32 DK060414, Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund. H.Y.L.: Eli and Edythe Broad Regeneration Medicine and Stem Cell Fellowship. The authors thank Donghui Wang (UCSF Preclinical Therapeutics Core), Chris Her (UCSF Liver Center Cell Biology Core), Vinh Nguyen (UCSF Flow Cytometry Core) and Matt Kofron and Mike Muntifering (CCHMC Nikon Center of Excellence Confocal Imaging Core) for technical support, Nick Timchenko, Maria Shrower and Abigail Roebker (CCHMC) for reagents and technical assistance, Rik Derynck (UCSF) for advice and Pamela Derish (UCSF) for manuscript editing.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Merrell AJ & Stanger BZ Adult cell plasticity in vivo: de-differentiation and transdifferentiation are back in style. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17, 413–425 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vanderpool C et al. Genetic interactions between hepatocyte nuclear factor-6 and Notch signaling regulate mouse intrahepatic bile duct development in vivo. Hepatology 55, 233–243 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarlow BD et al. Bipotential adult liver progenitors are derived from chronically injured mature hepatocytes. Cell Stem Cell 15, 605–618 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sekiya S & Suzuki A Hepatocytes, rather than cholangiocytes, can be the major source of primitive ductules in the chronically injured mouse liver. Am J Pathol 184, 1468–1478 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamimoto K et al. Heterogeneity and stochastic growth regulation of biliary epithelial cells dictate dynamic epithelial tissue remodeling. Elife 5, e15034 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanimizu N et al. Progressive induction of hepatocyte progenitor cells in chronically injured liver. Sci Rep 7, 39990 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zong Y et al. Notch signaling controls liver development by regulating biliary differentiation. Development 136, 1727–1739 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sparks EE, Huppert KA, Brown MA, Washington MK & Huppert SS Notch signaling regulates formation of the three-dimensional architecture of intrahepatic bile ducts in mice. Hepatology 51, 1391–1400 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeliazkova P et al. Canonical Notch2 signaling determines biliary cell fates of embryonic hepatoblasts and adult hepatocytes independent of Hes1. Hepatology 57, 2469–2479 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thorel F et al. Conversion of adult pancreatic alpha-cells to beta-cells after extreme beta-cell loss. Nature 464, 1149–1154 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stange DE et al. Differentiated Troy+ chief cells act as reserve stem cells to generate all lineages of the stomach epithelium. Cell 155, 357–368 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain R et al. Plasticity of Hopx(+) type I alveolar cells to regenerate type II cells in the lung. Nat Commun 6, 6727 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tetteh PW et al. Replacement of lost Lgr5-positive stem cells through plasticity of their enterocyte-lineage daughters. Cell Stem Cell 18, 203–213 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Eyken P, Sciot R & Desmet VJ A cytokeratin immunohistochemical study of cholestatic liver disease: evidence that hepatocytes can express ‘bile duct-type’ cytokeratins. Histopathology 15, 125–135 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Libbrecht L et al. Peripheral bile duct paucity and cholestasis in the liver of a patient with Alagille syndrome: further evidence supporting a lack of postnatal bile duct branching and elongation. Am J Surg Pathol 29, 820–826 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ernst LM, Spinner NB, Piccoli DA, Mauger J & Russo P Interlobular bile duct loss in pediatric cholestatic disease is associated with aberrant cytokeratin 7 expression by hepatocytes. Pediatr Dev Pathol 10, 383–390 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabris L et al. Analysis of liver repair mechanisms in Alagille syndrome and biliary atresia reveals a role for notch signaling. Am J Pathol 171, 641–653 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michalopoulos GK, Barua L & Bowen WC Transdifferentiation of rat hepatocytes into biliary cells after bile duct ligation and toxic biliary injury. Hepatology 41, 535–544 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yanger K et al. Robust cellular reprogramming occurs spontaneously during liver regeneration. Genes Dev 27, 719–724 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanimizu N, Nishikawa Y, Ichinohe N, Akiyama H & Mitaka T Sry HMG box protein 9-positive (Sox9+) epithelial cell adhesion molecule-negative (EpCAM-) biphenotypic cells derived from hepatocytes are involved in mouse liver regeneration. J Biol Chem 289, 7589–7598 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagahama Y et al. Contributions of hepatocytes and bile ductular cells in ductular reactions and remodeling of the biliary system after chronic liver injury. Am J Pathol 184, 3001–3012 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li L et al. Alagille syndrome is caused by mutations in human Jagged1, which encodes a ligand for Notch1. Nat Genet 16, 243–251 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oda T et al. Mutations in the human Jagged1 gene are responsible for Alagille syndrome. Nat Genet 16, 235–242 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDaniell R et al. NOTCH2 mutations cause Alagille syndrome, a heterogeneous disorder of the notch signaling pathway. Am J Hum Genet 79, 169–173 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poncy A et al. Transcription factors SOX4 and SOX9 cooperatively control development of bile ducts. Dev Biol 404, 136–148 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walter TJ, Vanderpool C, Cast AE & Huppert SS Intrahepatic bile duct regeneration in mice does not require Hnf6 or Notch signaling through Rbpj. Am J Pathol 184, 1479–1488 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gong AY et al. Somatostatin stimulates ductal bile absorption and inhibits ductal bile secretion in mice via SSTR2 on cholangiocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284, C1205–1214 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li B et al. Adult mouse liver contains two distinct populations of cholangiocytes. Stem Cell Reports 9, 478–489 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng L et al. RNA sequencing reveals dynamic changes of mRNA abundance of cytochromes P450 and their alternative transcripts during mouse liver development. Drug Metab Dispos 40, 1198–1209 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rezvani M et al. In vivo hepatic reprogramming of myofibroblasts with AAV vectors as a therapeutic strategy for liver fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell 18, 809–816 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiorotto R et al. Notch signaling regulates tubular morphogenesis during repair from biliary damage in mice. J Hepatol 59, 124–130 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clotman F et al. Control of liver cell fate decision by a gradient of TGF beta signaling modulated by Onecut transcription factors. Genes Dev 19, 1849–1854 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clotman F et al. The onecut transcription factor HNF6 is required for normal development of the biliary tract. Development 129, 1819–1828 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plumb-Rudewiez N et al. Transcription factor HNF-6/OC-1 inhibits the stimulation of the HNF-3alpha/Foxa1 gene by TGF-beta in mouse liver. Hepatology 40, 1266–1274 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanimizu N et al. Intrahepatic bile ducts are developed through formation of homogeneous continuous luminal network and its dynamic rearrangement in mice. Hepatology 64, 175–188 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rougemont AL et al. Bile ducts in regenerative liver nodules of Alagille patients are not the result of genetic mosaicism. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 61, 91–93 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raven A et al. Cholangiocytes act as facultative liver stem cells during impaired hepatocyte regeneration. Nature 547, 350–354 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mu X et al. Epithelial transforming growth factor-beta signaling does not contribute to liver fibrosis but protects mice from cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 150, 720–733 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luche H, Weber O, Nageswara Rao T, Blum C & Fehling HJ Faithful activation of an extra-bright red fluorescent protein in “knock-in” Cre-reporter mice ideally suited for lineage tracing studies. Eur J Immunol 37, 43–53 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto M et al. A multifunctional reporter mouse line for Cre- and FLP-dependent lineage analysis. Genesis 47, 107–114 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lakso M et al. Efficient in vivo manipulation of mouse genomic sequences at the zygote stage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93, 5860–5865 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snippert HJ et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell 143, 134–144 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levéen P et al. Induced disruption of the transforming growth factor beta type II receptor gene in mice causes a lethal inflammatory disorder that is transplantable. Blood 100, 560–568 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madisen L et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci 13, 133–140 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shinkai Y et al. RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell 68, 855–867 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao X et al. Defective lymphoid development in mice lacking expression of the common cytokine receptor gamma chain. Immunity 2, 223–238 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malato Y et al. Fate tracing of mature hepatocytes in mouse liver homeostasis and regeneration. J Clin Invest 121, 4850–4860 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raymond CS & Soriano P High-efficiency FLP and PhiC31 site-specific recombination in mammalian cells. PLoS One 2, e162 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wieser R, Wrana JL & Massagué J GS domain mutations that constitutively activate T beta R-I, the downstream signaling component in the TGF-beta receptor complex. EMBO J 14, 2199–2208 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schindelin J et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dorrell C et al. Prospective isolation of a bipotential clonogenic liver progenitor cell in adult mice. Genes Dev 25, 1193–1203 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Z, Wang M, Xiang Q, Sun Z & Zhang R The lectin of Dolichos biflorus agglutinin recognises glycan epitopes on the surface of a subset of cardiac progenitor cells. Cell Biol Int 37, 1238–1245 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orellana D et al. Calmodulin controls liver proliferation via interactions with C/EBPbeta-LAP and C/EBPbeta-LIP. J Biol Chem 285, 23444–23456 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siggs OM, Schnabl B, Webb B & Beutler B X-linked cholestasis in mouse due to mutations of the P4-ATPase ATP11C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 7890–7895 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Gene Expression Omnibus accession number for the RNA-seq data is GSE108315. Additional data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.