Abstract

As the largest and among the most behaviourally complex extant terrestrial mammals, proboscideans (elephants and their extinct relatives) are iconic representatives of the modern megafauna. The timing of the evolution of large brain size and above average encephalization quotient remains poorly understood due to the paucity of described endocranial casts. Here we created the most complete dataset on proboscidean endocranial capacity and analysed it using phylogenetic comparative methods and ancestral character states reconstruction using maximum likelihood. Our analyses support that, in general, brain size and body mass co-evolved in proboscideans across the Cenozoic; however, this pattern appears disrupted by two instances of specific increases in relative brain size in the late Oligocene and early Miocene. These increases in encephalization quotients seem to correspond to intervals of important climatic, environmental and faunal changes in Africa that may have positively selected for larger brain size or body mass.

Subject terms: Palaeontology, Neuroscience, Palaeontology

Introduction

In mammals, brains larger than 700 g have evolved infrequently, being found primarily in extant humans, cetaceans and elephants1. The temporal/evolutionary history of human brain size and shape has been studied in detail2–5, with the 700 g barrier on brain size evolution being surpassed with the appearance of Homo ergaster/erectus, approximately 1.8 million years ago1. The suborder Cetacea has many species that also exhibit large brains, both absolute and relative to body mass6,7. It has been established that large cetacean brains emerged with the evolution of the Neoceti approximately 32 million years ago8,9. In contrast to humans and cetaceans, the temporal and evolutionary history of brain size in Proboscidea is poorly understood1,10.

Elephants are the largest and among the most behaviourally complex terrestrial mammals. They are known for their extensive long-term memory, problem-solving abilities, behavioural adaptability, their ability to recognize themselves in a mirror, to manipulate their environment, and to manufacture tools with their trunk11,12. On the one hand, given that the metabolic cost of brain tissue is high13, and following the assumption that natural selection would not maintain a costly organ that brings no benefit, the presence of a large brain in elephants suggests there is some adaptive value, potentially related to their cognitive capacities. It has been proposed that evolutionary selective pressures requiring increased intelligence (e.g. cognitive and sensory processing, memory, behavioural flexibility) to cope with a variety of environmental variables (e.g. sociality, gregariousness, diet, habitat) has driven the evolution of large brains in both Primates and ‘ungulates’14–17. This is based on the retrospective assignation of implied cognitive needs centred on the apparent behavioural flexibility and intelligence of extant species. Similarly, this retrospectively applied cognitive explanatory paradigm has been argued to apply to the evolution of a large brain in cetaceans18–20, and elephants10,12; however, alternative explanations of brain size evolution have been forwarded, focussing on features such as the structural laws of form linking body and brain mass over evolutionary time1,7,21,22. Under this assumption, the elephantine brain is a typical mammalian brain that appears “to scale consistently with the scaling laws governing brain and body mass relationships across mammals”1. In parallel, the assumption that complex cognition requires an increase in brain size has been heavily criticized1,21,23,24. Therefore whether the evolution of a large brain is an adaptive trait (e.g.)10, or simply accompanied the increase in body mass in proboscideans (e.g.)1, remains an open question.

While proboscidean evolution is well documented and understood25–30, studies of the brains and endocranial casts of extinct proboscidean genera are limited10,12,31–35. These studies have indicated that brain size, both in absolute and relative terms, appears to have increased dramatically in Elephantiformes, sometime between the Oligocene and Pliocene, a poorly constrained interval of more than 30 million years10. Thus, the timing and rate of changes in brain size, and the taxa involved in the evolution of a large brain during proboscidean evolution remains unclear. Building on the database of Benoit10, by adding data from three key taxa, Zygolophodon (Mammut) borsoni, Palaeomastodon beadnelli and Stegodon insignis, we apply statistical and phylogenetic comparative methodology to changes in brain size in proboscideans throughout their evolutionary history. To address whether a large brain in proboscideans evolved as an adaptation or as a consequence of increased body mass, we examined the temporal scaling relationships of brain with body size and with associated environmental changes that have occurred during proboscidean evolutionary history.

Methods

Data collection

Data analysed (endocranial volume and body mass) are summarized in Table 1. Data for extant species of elephants are from Benoit et al.36 (note that this dataset contained two duplicated lines that are removed here) and those for extinct species are from Benoit10. The body masses of some extinct taxa were updated using the recent estimates of Larramendi and Palombo32 and Larramendi37 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Endocast, calculated brain size and Manger’s EQ7 for the proboscideans used in the analyses.

| Endocast volume (cm3) | Brain size (g) | Body mass (g) | EQ Manger | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elephas maximus | 4550b | 4181 | 2267430b | 1,83 |

| Elephas maximus | 5220b | 4798 | 3216000b | 1,62 |

| Elephas maximus | 5000b | 4595 | 3450400b | 1,48 |

| Elephas maximus | 6075b | 5584 | 3190098b | 1,90 |

| Loxodonta africana | 5712b | 5250 | 6654000b | 1,05 |

| Loxodonta africana | 9000b | 8274 | 4380000b | 2,23 |

| Loxodonta africana | 4000b | 3676 | 5174400b | 0,88 |

| Loxodonta africana | 4050b | 3722 | 1793300b | 1,93 |

| Loxodonta africana | 4420b | 4062 | 3505000b | 1,29 |

| Loxodonta africana | 5300b | 4871 | 5550000b | 1,11 |

| Loxodonta africana | 4480b | 4117 | 2750000b | 1,56 |

| Loxodonta africana | 4210b | 3869 | 4000000b | 1,12 |

| Loxodonta africana | 4100b | 3768 | 2160000b | 1,70 |

| Loxodonta africana | 4000b | 3676 | 2537000b | 1,48 |

| Palaeoloxodon falconeri | 1800a | 1652 | 1680004 | 4,81 |

| Palaeoloxodon antiquus | 5446a | 5005 | 3649880a | 1,54 |

| Palaeoloxodon antiquus | 9000a | 8274 | 11000000c | 1,14 |

| Mammuthus primigenius | 4687a | 4307 | 6000000d | 0,92 |

| Mammuthus meridionalis | 5828a | 5357 | 11000000d | 0,74 |

| Mammuthus columbi | 6232a | 5728 | 9800000d | 0,86 |

| Mammut americanum | 3862a | 3549 | 6384056a | 0,73 |

| Mammut americanum | 4630a | 4255 | 8000000d | 0,74 |

| Stegodon insignis | 3838 | 3527 | 2000000d | 1,69 |

| Zygolophodon borsoni | 5133 | 4718 | 16000000d | 0,50 |

| Palaeomastodon beadnelli | 771 | 706 | 2500000d | 0,29 |

| Moeritherium lyonsi | 240a | 218 | 810000d | 0,20 |

| Prorastomus sirenoides | 87b | 90 | 98156b | 0,39 |

| Seggeurius amourensis | 5b | 5 | 2932b | 0,29 |

This dataset was also updated with the addition of endocranial volume and body mass of three taxa: Zygolophodon (Mammut) borsoni (MCFFM-CLB-1), from the Pliocene (Mammal Neogene zone 15) of Otman Hill (Moldova)38, Stegodon insignis (MNHN-A952) from an unknown Miocene locality in the Himalayas39, and Palaeomastodon beadnelli (NHMUK PV M 8464) from the early Oligocene of the Fayum deposits (Egypt)40. As one of the largest proboscideans that existed37, Z. borsoni is important for discussing the effect of body mass on the evolution of brain mass in proboscideans. Stegodontids may be the possible outgroup of modern elephantids, and Palaeomastodon beadnelli is the basal-most known elephantiform and the closest relative of the clade Elephantimorpha in the dataset26,28–30,41. For this study, the braincase of P. beadnelli (NHMUK PV M 8464), which is partially exposed40, was carefully examined and drawn by a palaeo-artist (Sophie Vrard) in dorsal and ventral views under the supervision of J.B. (Supplementary Fig. 1). The endocranial volume was estimated to 771 cm3 using double-graphic integration on the drawings31. Radinsky (ref.42, p. 84) performed comparisons with the water displacement technique that validated the accuracy of double graphic integration and suggested that this method should be preferred in case of incomplete preservation or when direct measurement is impossible, as is the case here with NHMUK PV M 8464. As originally described, specimen MNHN-A952 is the cast of the right side of the braincase of a Stegodon insignis skull assembled with the left endocast of a modern elephant to enable Gervais39 to reconstruct a complete endocranial cast (Supplementary Fig. 2). The endocranial size of Zygolophodon (Mammut) borsoni is based on a latex endocranial cast of specimen MCFFM-CLB-1 (Fossil Fauna Complex Museum of Moldova, Chisinau) (Supplementary Fig. 3). To measure its volume, the endocast was digitized using photogrammetry AgiSoft PhotoScan Professional Version 1.3.2), a method that has proven as accurate as CT scanning43 and sometimes more accurate than laser-scanning44,45. The volume of the resulting mesh was then measured using Avizo (FEI VSG, Hillsboro OR, USA). The resulting volume is 5133 cm3 (the Zygolophodon endocast was also measured at 4910 cm3 using water displacement, but the digital measure was preferred as it less prone to errors)2. To measure the volume of the endocast of Stegodon insignis, the complete endocast was digitized using photogrammetry, its right half isolated digitally, and the volume of the resulting mesh was measured using the same software programs. The resulting volume, 1919 cm3, was then multiplied by two to obtain the volume of a complete endocast. Body masses for these three taxa are from Larramendi37. The encephalization quotient (EQ) used is that of Manger7, which is very similar to Eisenberg’s EQ46, although it excludes outliers such as cetaceans and primates. Brain volumes used to calculate EQ are based on endocranial volumes corrected for meningeal thickness using Benoit’s10 method. This is a necessary step as the thick meninges in proboscideans occupy some 14% of the endocranial cavity with non-neural tissue on average10. The resulting brain volumes were then multiplied by 1.036, which represents the average specific gravity of brain tissue32,47.

Ancestral character state reconstruction

In order to analyse temporal patterns of endocranial volume, body mass and EQ changes across proboscidean phylogenetic history, an ancestral character state reconstruction using maximum likelihood (ACSRML) was performed using the function fastAnc in the R package ‘phytools’48 (excluding the sirenian Prorastomus and the hyracoid Seggeurius). The phylogeny used for the ACSRML was assembled following the current consensus28–30,41 (Supplementary Fig. 4). The resulting dates are consistent with the recently published palaeogenomic study by Palkopoulou et al.49. There have been many discrepancies concerning the phylogenetic placement of the genus Palaeoloxodon. Palaeogenomic studies have consistently placed P. antiquus within the African elephant genus Loxodonta49,50, whereas studies of the mitochondrial DNA have suggested that P. falconeri belongs to the Asian elephant genus Elephas51,52. Given the morphological support for the validity of the genus Palaeoloxodon25,53,54 and the burden of evidence in favour of a direct ancestor to descendant relationship between P. antiquus and P. falconeri respectively29,55,56, we preferred to remain conservative and preserved the monophyly of the genus Palaeoloxodon. Nevertheless, the branch leading to Palaeoloxodon is in an unresolved position within Elephantida in order to reflect these phylogenetic inconsistencies (Supplementary Fig. 4). Divergence ages and branch lengths were determined based on published literature29,57.

Phylogenetic regressions

In order to test for the presence of a functional relationship between brain mass and body mass, linear regressions were performed on our datasets (excluding the sirenian Prorastomus and the hyracoid Seggeurius). In such statistical analyses, there are several assumptions made about the data, such as normality, homoscedasticity and independence of observations. When comparing traits of different species, independence is considered potentially violated because of the evolutionary relationships of species to each other, and thus phylogeny needs to be considered as part of the analysis58. All analyses were performed in R v. 3.5.3 (R Core Team, 2019).

Phylogenetic generalized least squares (PGLS)59 are a very well-known and frequently used phylogenetic comparative method (see Garamszegi60, for an extensive review), designed to consider the influence of evolutionary relationships between species (i.e., phylogenetic signal sensu Blomberg and Garland)61 in a generalized linear model, using a regression of one or more continuous predictors over a response variable. After a log-conversion to better approximate the allometric relationship between variables of interest62,63, endocranial volume was regressed on body mass using a calibrated phylogeny of Proboscidea in the dataset (Supplementary Fig. 4; Supplementary Material 5). Since the evolutionary model followed by this regression is not known, the analysis was performed several times using different evolutionary models, and the goodness of fit of each model determined from their AICc score, i.e., the Akaike Information Criterion corrected for finite sample size64. Using the R package ‘AICcmodavg’65, AICc scores were compared for five different evolutionary models: Brownian motion, i.e., a purely neutral model of evolution66; Ornstein-Uhlenbeck, i.e., a model with selective optima along the branches67; lambda model, i.e. modified Brownian motion model with all branch lengths weighted using Pagel’s lambda, a common estimator of phylogenetic signal68, here estimated from the dataset through maximum likelihood; Early Burst, i.e., model with high initial evolutionary rates that decelerate through time after a cladogenesis event69; and Ordinary Least Squares (i.e simple, non-phylogenetic least squares regression). The model with the lowest AICc score was found to be the lambda model (AICc = −18.2, vs a range of −6.8–10.11 for other evolutionary models), with λ = 0.90, indicating a strong phylogenetic signal in the regression. Thus, the lambda model was selected to perform further analyzes on the dataset. PGLS were performed using the function gls in the R package ‘nlme’70, and the phylogenetic correlation structure corPagel (for the lambda model) specified in the package ‘ape’71.

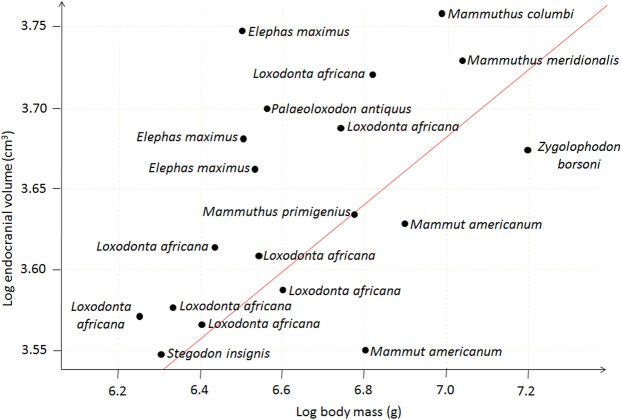

Normality and homoscedasticity of the residuals in the model were assessed using a Lilliefors test in the package ‘nortest’72, as well as graphically checked through plotting against corresponding fitted values, to conform to the parametric assumptions of PGLS73. Residuals were found to be non-normal, and seven outliers were graphically detected and removed from the dataset (Supplementary Material 6). These outliers consist of Moeritherium lyonsi, Palaeomastodon beadnelli, Palaeoloxodon falconeri, one specimen of Palaeoloxodon antiquus as well as one specimen of Elephas maximus and two of Loxondonta africana. After pruning the corresponding branches in the tree, regression analyses were performed again, and the new residuals were found to be normal and homoscedastic (Fig. 1), allowing for a straightforward interpretation of the new results.

Figure 1.

Regressions of log brain mass over log body corrected for phylogeny excluding outliers.

Results

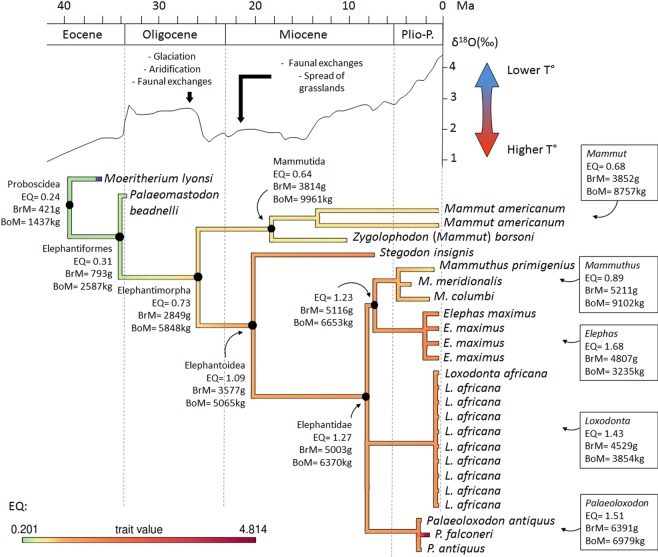

According to the ACSRML, which was performed on the whole dataset (Fig. 2), the EQ in the last common ancestor (LCA) of Moeritherium and Elephantiformes is 0.24. It increases slightly in the next node to reach 0.3 in the LCA of Elephantiformes (Palaeomastodon and more derived proboscideans). The reconstructed brain and body masses at this node are about 1.8 times larger than in the previous node, while the EQ remains similar, which indicates that during the Paleogene, increases in brain mass were proportional to increases in body mass in basal proboscideans (Fig. 2). The reconstructed EQ doubles in the node corresponding to the common ancestor of Elephantimorpha that lived some 26 Ma ago in the late Oligocene, where it reaches a value of 0.73. At this node, the ACSRML indicates that body mass has increased by 2.3 times while brain mass has increased by 3.6 times compared to the previous node (Fig. 2). The reconstructed EQ then decreases slightly in the lineage leading to Mammutida and Mammut (0.64 and 0.68 respectively) in which the reconstructed body mass exceeds 8 tons while brain mass gains only 1 kg (Fig. 2). In contrast, the EQ is nearly doubled again in the LCA of the Elephantoidea that lived some 20 Ma ago in the Early Miocene, to reach 1.09. At this node, the reconstructed body mass decreases slightly while brain mass is reconstructed as being about 1.2 times larger than in the previous node (Fig. 2). Reconstructed ancestral EQs, and brain and body masses then remain relatively stable across Elephantoidea and Elephantidae phylogeny (Fig. 2). Reconstructed ancestral body masses vary between about 4 and 7 tons, while brain masses vary between 4.5 and 6.4 kg in Elephantidae (Fig. 2). Reconstructed variations in the EQ nevertheless appear mostly due to variations in body mass. In the Mammuthus clade, the elevated reconstructed body mass (9.1 tons) coincides with a decrease in the reconstructed EQ compared to the ancestral value in the LCA of Elephantoidea to 0.89 (Fig. 2). In contrast, the increase in EQ to 1.68 in the Elephas clade is accompanied by a decrease in ancestral body mass to 3.2 tons (Fig. 2). The ancestral value for the Palaeoloxodon clade is surprisingly close to that for the LCA of Elephantidae (1.51).

Figure 2.

Results of the Ancestral Character State Reconstruction using Maximum Likelihood. Geological time scale and δ18O curve after Zachos et al.84. Abbreviations: BoM, body mass; BrM, brain mass; EQ, encephalization quotient.

The EQ varies around 1.47 ± 0.76 among all Elephantimorpha except in two taxa that display extreme EQ values. On one end of the spectrum is the small bodied and highly encephalized dwarf elephant of Sicily, Palaeoloxodon falconeri, which displays an EQ of 4.81 (Table 1). This species is well studied and its large EQ has been extensively discussed in the literature10,32,34. Its body size is between one tenth and one hundredth that of its close relative, Palaeoloxodon antiquus, whereas its endocast volume is about one half to one quarter that of P. antiquus10,32,34 (Table 1). On the opposite end of the spectrum is Zygolophodon (Mammut) borsoni which, with an estimated body mass of 16 tons37, is the heaviest species in the dataset. The Zygolophodon EQ of 0.50 also makes it the least encephalized of all Elephantimorpha, although the clade to which it belongs, the Mammutida, ancestrally display a low EQ value (0.64) similar to that reconstructed for the ancestral Elephantimorpha (Fig. 2).

The regression of brain mass over body mass corrected for phylogeny and excluding outliers (Fig. 1) shows that the relationship between the two variables is significant (p-value = 0.0004), but their correlation is relatively weak (R² = 0.50) and the slope of the regression line is low (0.20). This indicates that brain and body mass are significantly correlated, but this correlation and the effect of the brain and body mass on each other are moderate.

When outliers are included (Supplementary Material 6), the correlation between the two variables is slightly higher (R² = 0.61) and remains significant (P-value < 0.0001); however, since the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity of the sample are not met for this analysis, this result is of dubious reliability73.

Discussion

The oldest known endocranial cast of a proboscidean belongs to Moeritherium lyonsi from the late Eocene Qasr el Sagha Formation of the Fayum, Egypt40. The EQ of Moeritherium equals 0.2 (Table 1), which is an order of magnitude smaller than in any Elephantimorpha (Table 1). A comparably low EQ value is also found in Palaeomastodon (EQ = 0.29), which was contemporaneous with Moeritherium, and in the paenungulates Seggeurius (EQ = 0.29) and Prorastomus (EQ = 0.39), the basal-most hyracoid and sirenian respectively, and the closest relatives of proboscideans that lived during the early Eocene (~50 Ma)36 (Table 1). As a consequence, it is not surprising that a rather small EQ is reconstructed as primitive for Proboscidea and Elephantiformes by the ancestral character state analysis (Fig. 2). The relatively small brain cavity of Phosphatherium, a stem proboscidean from the early Eocene (−55 Ma)74 supports this assumption.

The analysis also suggests that brain mass evolved proportionally to body size in non-elephantimorph proboscideans (‘Plesielephantiformes’) and among more derived elephantids (Fig. 2), which is supported by the significant correlation between brain and body mass in the dataset (p-value = 0.0004). This would support the idea that brain mass evolved as a ‘simple passenger’ of body mass in these two groups, as hypothesized by Manger1. Given the relationship between brain and body mass variation, it can be predicted that non-elephantimorph taxa with body masses already approaching or exceeding two tons, such as Barytherium and the Deinotheriidae27,34,75,76 would have had an absolutely larger brain than the basal most proboscideans. This assumption might be addressed in the future, when more data on the endocasts of Barytherium and the Deinotheriidae becomes available.

In contrast, the ACSRML suggests that brain mass increases much faster than body mass in Elephantimorpha, resulting in two pulses of increase in the EQ: (i) the EQ doubles in the LCA of Elephantimorpha and (ii) it almost doubles again in the LCA of Elephantoidea (Fig. 2). Subsequently, the EQ essentially remains the same among Elephantoidea, including modern proboscideans (Fig. 2). According to the ACSRML (Fig. 2), brain mass began increasing in the basal-most elephantimorphs, the Mammutida (M. americanum and Z. borsoni), where the EQ is about twice that of Moeritherium and Palaeomastodon (Table 1). A brain mass equivalent to that of most modern elephants is achieved in the LCA of the Elephantoidea (Fig. 2). These two pulses suggest that, at least in the LCA of Elephantimorpha and Elephantoidea, increases in brain mass were decoupled from increases in body mass, and that an increase in EQ was positively selected for.

What could have driven such increases in EQ? According to both the fossil record and molecular studies, the LCA of Elephantimorpha lived some 26 million years ago in the late Oligocene28,29,57,77, and the LCA of the Elephantoidea lived around 20 million years ago in the early Miocene28,29. These time points are contemporaneous with two periods of increased aridity on the African continent, accompanied by glaciations, arrival of invasive faunal elements from Eurasia, dispersal of proboscideans out of Africa and the spread of C4 plants28,78–84 (Fig. 2). Gregariousness17,85, greater behavioural flexibility86 and the ability to produce complex long distance, infrasonic calls12,25,87,88 have been documented in Miocene elephantiforms and may have played a role in increasing the fitness of relatively larger brained individuals in the context of ecological changes10,14,15. An enhanced long term memory may have facilitated the recalling of the location of distant water holes during increasingly frequent droughts11, though evidence from the fossil record is lacking10. A shift in proboscidean diets (as a result of the advent of the conveyor-belt type of dental replacement and increasing hypsodonty)77,86 seems an unlikely driver for the evolution of a higher EQ because (i) proboscideans remained primarily browsers until elephantids became grazers some 7 million years ago86,89,90, and (ii) no undisputable correlation is evident between diet and brain size in ‘ungulates’14,15.

Alternatively, given that brain and body size variations appear significantly correlated in proboscideans (Fig. 1), it is possible that body mass, not brain mass, could have been the main trait under selective pressure during these two time intervals. Positive selection for larger body size could have provided early elephantimorphs with protection against the novel invasive predators and competitors from Eurasia, and large herbivores are known to be less sensitive to droughts and increased seasonality as they can store more fat and water, and can subsist on lower quality food (e.g. grasslands) due to their larger digestive tract and lower metabolic rate75,91,92. In this respect, it is noteworthy that other ‘ungulate’ taxa contemporaneously show an overall increase of their brain and body mass in the early Neogene1,93,94. This would make the increase in EQ merely a correlate of the increase of body mass, as already hypothesized by Manger et al.1. However, brain mass increases faster than body mass in this portion of the tree, and the latter even decreases slightly in the LCA of Elephantoidea compared to the LCA of Elephantimorpha (Fig. 2), which does not match what would be expected under the assumption that body mass was the main driver of EQ increase.

Conclusion

Overall, there does not seem to be one single hypothesis accounting for the complete evolution of the brain in proboscideans. Part of the evolution of a larger absolute brain mass may be explained by the co-evolution of brain and body mass (in ‘plesielephantiforms’ and elephantids) and part of this process seems to better explained by potential selective pressures (in the LCAs of Elephantoidea and Elephantimorpha), perhaps as a result of climatic and environmental changes in Africa, as well as with dispersal events. Despite this, brain size evolution remains significantly correlated to body size in proboscideans, which cautions against an explanatory scenario involving intelligence alone as the main focus of natural selection. The precise timing of the two identified pulsed increases in relative brain size remains poorly temporally constrained due to the small sample size that makes it difficult to obtain reasonable phylogenetic resolution. Considerable effort will have to be put into collecting data for key taxa that will fill the temporal voids in the current data set. The inclusion of Barytheriidae and Deinotheriidae - as some of the closest relatives to Elephantiformes and the earliest large proboscideans- and investigation of whether they evolved a larger brain independently of other ‘Plesielephantiformes’ will prove crucial in this respect1.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank S. Vrard, C. Bibal, M.R. Palombo, P. Tassy, P. Brewer, C. Argot, M. Cazenave, C. Hendrickx; and to the financial support of the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Palaeosciences, the Claude Leon Foundation and the des Treilles Foundation (Paris): “La Fondation des Treilles, créée par Anne Gruner Schlumberger, a notamment pour vocation d’ouvrir et de nourrir le dialogue entre les sciences et les arts afin de faire progresser la création et la recherche contemporaines. Elle accueille également des chercheurs et des écrivains dans le domaine des Treilles (Var, France). www.les treilles.com”.

Author Contributions

All authors had full access to all the data in the study and gave final approval for publication. Study concept and design: J.B. and P.M. Acquisition of data: J.B., R.T., T.O. and V.M. Analysis and interpretation of data: J.B. and L.J.L. Drafting of the manuscript: J.B., L.J.L., R.T. and P.M. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: T.O., R.T. and P.M. Obtained funding: J.B.

Data Availability

All the data necessary to reproduce this research are provided with the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-45888-4.

References

- 1.Manger PR, Spocter MA, Patzke N. The Evolutions of Large Brain Size in Mammals: The ‘Over-700-Gram Club Quartet’. Brain Behav. Evol. 2013;82:68–78. doi: 10.1159/000352056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holloway, R. L. On the Making of Endocasts: The New and the Old in Paleoneurology in Digital Endocasts (eds Bruner, E., Ogihara, N. & Tanabe, H.), 1–8. (Springer Japan KK, 2018).

- 3.Carlson KJ, et al. The Endocast of MH1, Australopithecus sediba. Science. 2011;333:1402–1407. doi: 10.1126/science.1203922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zollikofer CPE, De León MSP. Pandora’s growing box: Inferring the evolution and development of hominin brains from endocasts. Evol. Anthropol. 2013;22:20–33. doi: 10.1002/evan.21333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaudet A, et al. The endocast of StW 573 (‘Little Foot’) and hominin brain evolution. J Hum Evol. 2019;126:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marino L. A Comparison of Encephalization between Odontocete Cetaceans and Anthropoid Primates. Brain Behav. Evol. 1998;51:230–238. doi: 10.1159/000006540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manger PR. An examination of cetacean brain structure with a novel hypothesis correlating thermogenesis to the evolution of a big brain. Biol. Rev. 2006;81:293. doi: 10.1017/S1464793106007019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marino L, McShea DW, Uhen MD. Origin and evolution of large brains in toothed whales. Anat. Rec. 2004;281A:1247–1255. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montgomery SH, et al. The evolutionary history of Cetacean brain and body size. Evol. 2013;67:3339–3353. doi: 10.1111/evo.12197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benoit J. A new method of estimating brain mass through cranial capacity in extinct proboscideans to account for the non-neural tissues surrounding their brain. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2015;35:e991021. doi: 10.1080/02724634.2014.991021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hart BL, Hart LA, Pinter-Wollman N. Large brains and cognition: Where do elephants fit in? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2007;32:86–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shoshani J, Kupsky WJ, Marchant GH. Elephant brain. Brain Res. Bull. 2006;70:124–157. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aiello LC, Wheeler P. The expensive-tissue hypothesis: The brain and the digestive system in human and primate evolution. Curr. Anthropol. 1995;36:199–221. doi: 10.1086/204350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shultz S, Dunbar RIM. Both social and ecological factors predict ungulate brain size. Proc. Roy. Soc. B. 2006;273:207–215. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pérez-Barbería FJ, Gordon IJ. Gregariousness increases brain size in ungulates. Oecologia. 2005;145:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeCasien AR, Williams SA, Higham JP. Primate brain size is predicted by diet but not sociality. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017;1(5):112. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell LE, Isler K, Barton RA. Re-evaluating the link between brain size and behavioural ecology in primates. Proc.Roy. Soc. B. 2017;284:20171765. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marino L, et al. A claim in search of evidence: reply to Manger’s thermogenesis hypothesis of cetacean brain structure. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2008;83:417–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox KCR, Muthukrishna M, Shultz S. The social and cultural roots of whale and dolphin brains. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017;1:1699–1705. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0336-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu S, et al. Genetic basis of brain size evolution in cetaceans: insights from adaptive evolution of seven primary microcephaly (MCPH) genes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017;17(1):206. doi: 10.1186/s12862-017-1051-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manger PR. Questioning the interpretations of behavioral observations of cetaceans: Is there really support for a special intellectual status for this mammalian order? Neurosci. 2013;250:664–696. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manger, P. R., Hemingway, J., Spocter, M. A. & Gallagher, A. The mass of the human brain: is it a spandrel? In African Genesis (eds Reynolds, S. C., Gallagher, A.), 181–204. (Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- 23.Deacon TW. Fallacies of progression in theories of brain-size evolution. Int. J. Primatol. 1990;11:193–236. doi: 10.1007/BF02192869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Healy SD, Rowe C. A critique of comparative studies of brain size. Proc. Roy. Soc. B. 2012;274(1609):453–464. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shoshani J, Tassy P. Advances in proboscidean taxonomy & classification, anatomy & physiology, and ecology & behavior. Quat. Int. 2005;126–128:5–20. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gheerbrant E, Tassy P. L’origine et l’évolution des éléphants. C. R. Palevol. 2009;8:281–294. doi: 10.1016/j.crpv.2008.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanders, W. J., Gheerbrant, E., Harris, J. M., Saegusa, H. & Delmer, C. Proboscidea. In Cenozoic Mammals of Africa (eds Werdelin, L., Sanders, W. J.), 161–251 (University of California Press, 2010).

- 28.Van Der Made, J. The evolution of elephants and their relatives in the context of a changing climate and geography in Elefantenreich – Eine Fossilwelt in Europa (ed. Meller, H.), 341–360. (Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt & Landesmuseum Vorgeschichte, 2010).

- 29.Shauer, K. Commentary and sources for the evolutionary diagram of the Proboscidea in Africa and Eurasia in Elefantenreich – Eine Fossilwelt in Europa (ed. Meller, H.), 631–650 (Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt & Landesmuseum Vorgeschichte, 2010).

- 30.Fisher DC. Paleobiology of Pleistocene Proboscideans. Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 2018;46:229–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev-earth-060115-012437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jerison, H. J. Evolution of the Brain and Intelligence (Academic Press, 1973).

- 32.Palombo MR, Giovinazzo C. Elephas falconeri from Spinagallo Cave (South-Eastern Sicily, Hyblean Plateau, Siracusa): brain to body weight comparison. Monogr. Soc. Hist. Nat. Balears. 2005;12:255–264A. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fisher DC, et al. X-ray computed tomography of two mammoth calf mummies. J. Paleontol. 2014;88:664–675. doi: 10.1666/13-092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larramendi A, Palombo MR. Body size, biology and encephalization quotient of Palaeoloxodon ex gr. P. falconeri from Spinagallo Cave (Hyblean plateau, Sicily) Hystrix Ital. J. Mammal. 2015;26:102–109. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kharlamova AS, et al. The mummified brain of a Pleistocene woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) compared with the brain of the extant African elephant (Loxodonta africana) J. Comp. Neurol. 2015;523:2326–2343. doi: 10.1002/cne.23817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benoit J, Crumpton N, Mérigeaud S, Tabuce R. A Memory Already like an Elephant’s? The Advanced Brain Morphology of the Last Common Ancestor of Afrotheria (Mammalia) Brain Behav. Evol. 2013;81:154–169. doi: 10.1159/000348481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larramendi A. Shoulder height, body mass, and shape of proboscideans. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 2016;61:537–574. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obada T. Preliminary data on the Mammut borsoni (Hays, 1834) from Otman Hill (Colibaşi, Republic of Moldova) Abstract Book of the VIth International Conference on Mammoths and their Relatives. S.A.S.G. 2014;102:143–144. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gervais P. Mémoire sur les formes cérébrales propres à différents groupes de mammifères. J. Zool. 1872;1:425–469. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrews, C. W. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Tertiary Vertebrata of Fayum, Egypt. (British Museum Natural History press, 1906).

- 41.Tassy P. The classification of Proboscidea: How many cladistic classifications? Cladistics. 1988;4:43–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1988.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radinsky L. Early primate brains: Facts and fiction. J. Hum. Evol. 1977;6:79–86. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2484(77)80043-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fahlke JM, Autenrieth M. Photogrammetry vs. Micro-CT scanning for 3D surface generation of a typical vertebrate fossil – A case study. J. Paleontol. Tech. 2016;14:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutton M, Rahman I, Garwood R. Virtual paleontology — an overview. Paleontol. Soc. Pap. 2016;22:1–20. doi: 10.1017/scs.2017.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evin A, et al. The use of close-range photogrammetry in zooarchaeology: Creating accurate 3D models of wolf crania to study dog domestication. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2016;9:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eisenberg, J. F. The mammalian radiations (University of Chicago Press, 1981).

- 47.Stephan H, Frahm H, Baron G. New and revised data on volumes of brain structures in insectivores and primates. Folia Primatol. 1981;35:1–29. doi: 10.1159/000155963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Revell LJ. phytools: an R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things) Meth. Ecol. Evol. 2011;3:217–223. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00169.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palkopoulou E, et al. A comprehensive genomic history of extinct and living elephants. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2018;115:E2566–E2574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720554115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyer M, et al. Palaeogenomes of Eurasian straight-tusked elephants challenge the current view of elephant evolution. eLife. 2017;6:e25413. doi: 10.7554/eLife.25413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poulakakis N, Theodorou GE, Zouros E, Mylonas M. Molecular Phylogeny of the Extinct Pleistocene Dwarf Elephant Palaeoloxodon antiquus falconeri from Tilos Island, Dodekanisa, Greece. J. Mol. Evol. 2002;55:364–374. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2337-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Poulakakis N, et al. Ancient DNA forces reconsideration of evolutionary history of Mediterranean pygmy elephantids. Biol. Lett. 2006;2:451–454. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Osborn HF. Palaeoloxodon antiquus italicus sp. nov., final stage in the ‘Elephas antiquus’ phylum. Am. Mus. Novit. 1931;460:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Osborn, H. F. Proboscidea: a monograph of the discovery, evolution, migration and extinction of the mastodonts and elephants of the world. Vol. II: Stegodontoidea, Elephantoidea (The American Museum Press, 1942).

- 55.Palombo, M. R. Paedomorphic features and allometric growth in the skull of Elephas falconeri from Spinagallo (Middle Pleistocene, Sicily) in Proceedings of the 1st International Congress of “La Terra degli Elefanti”, The World of Elephants (eds Cavarretta, G., Gioia, P., Mussi, M., Palombo, M. R.), 492–496 (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, 2001).

- 56.Palombo MR, Giovinazzo C. Elephas falconeri from Spinagallo Cave (south-eastern Sicily, Hyblean Plateau, Siracusa): A preliminary report on brain to body weight comparison. Monogr. Soc. Hist. Nat. Balears. 2005;12:255–264. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rohland N, et al. Proboscidean Mitogenomics: Chronology and Mode of Elephant Evolution Using Mastodon as Outgroup. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Felsenstein J. Phylogenies and the Comparative Method. Am. Nat. 1985;125:1–15. doi: 10.1086/284325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grafen A. The phylogenetic regression. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. B. 1989;326:119–157. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1989.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garamszegi, L. Z. & Mundry, R. Multimodel-inference in comparative analyses in Modern Phylogenetic Comparative Methods and Their Application in Evolutionary Biology (ed. Garamszegi, L. Z.), 305–331 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014).

- 61.Blomberg SP, Garland T., Jr. Tempo and mode in evolution: phylogenetic inertia, adaptation and comparative methods. J. Evol. Biol. 2002;15:899–910. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00472.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mascaro J, Litton CM, Hughes RF, Uowolo A, Schnitzer SA. Is logarithmic transformation necessary in allometry? Ten, one-hundred, one-thousand-times yes. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2014;111:230–233. doi: 10.1111/bij.12177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Montgomery SH, Mundy NI, Barton RA. Brain evolution and development: adaptation, allometry and constraint. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. B. 2016;283:20160433. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.0433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burnham KP, Anderson DR, Huyvaert KP. AIC model selection and multimodel inference in behavioral ecology: some background, observations, and comparisons. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2010;65:23–35. doi: 10.1007/s00265-010-1029-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mazerolle, M. J. AICcmodavg: Model selection and multimodel inference based on (Q)AIC(c). R package version 2.1-1 (2017).

- 66.Felsenstein J. Maximum likelihood estimation of volutionary trees from continuous characters. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1973;25:471–492. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Butler MA, King AA. Phylogenetic Comparative Analysis: A Modeling Approach for Adaptive Evolution. Am. Nat. 2004;164:683–695. doi: 10.1086/426002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pagel M. Inferring the historical patterns of biological evolution. Nature. 1999;401:877–884. doi: 10.1038/44766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harmon LJ, et al. Early bursts of body size and shape evolution are rare in comparative data. Evol. 2010;64(8):2385–2396. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S., Sarkar, D. & R. Core Team. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1-137 (2018).

- 71.Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K. Bioinform. 2004. APE: Analyses of Phylogenetics and Evolution in R language; pp. 289–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gross, J. & Ligges, U. nortest: Tests for Normality. R package version 1.0-3 (2015).

- 73.Mundry Roger. Modern Phylogenetic Comparative Methods and Their Application in Evolutionary Biology. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2014. Statistical Issues and Assumptions of Phylogenetic Generalized Least Squares; pp. 131–153. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gheerbrant E, et al. Nouvelles données sur Phosphatherium escuilliei (Mammalia, Proboscidea) de l’Éocène inférieur du Maroc, apports à la phylogénie des Proboscidea et des ongulés lophodontes. Geodiversitas. 2005;27:239–333. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Christiansen P. Body size in proboscideans, with notes on elephant metabolism. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2004;140:523–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2004.00113.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Evans AR, et al. The maximum rate of mammal evolution. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:4187–4190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120774109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shoshani J, et al. A proboscidean from the late Oligocene of Eritrea, a ‘missing link’ between early Elephantiformes and Elephantimorpha, and biogeographic implications. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:17296–17301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603689103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kappelman J, et al. Oligocene mammals from Ethiopia and faunal exchange between Afro-Arabia and Eurasia. Nature. 2003;426:549–552. doi: 10.1038/nature02102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Antoine P-O, et al. First record of Paleogene Elephantoidea (Mammalia, Proboscidea) from the Bugti Hills of Pakistan. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 2003;23:977–980. doi: 10.1671/2453-25. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Feakins, S. J. & Demenocal, P. B. Global and African Regional Climate during the Cenozoic in Cenozoic Mammals of Africa (eds Werdelin, L., Sanders, J. S.), 45–56. (University of California Press, 2010).

- 81.Jacobs, B. F., Pan, A. D. & Scotese, C. R. A Review of the Cenozoic Vegetation History of Africa in Cenozoic Mammals of Africa (eds Werdelin, L. & Sanders, J. S.), 57–72. (University of California Press, 2010).

- 82.Sen S. Dispersal of African mammals in Eurasia during the Cenozoic: Ways and whys. Geobios. 2013;46:159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.geobios.2012.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tabuce R, Marivaux L. Mammalian interchanges between Africa and Eurasia: an analysis of temporal constraints on plausible anthropoid dispersals during the Paleogene. Anthropol. Sci. 2005;113:27–32. doi: 10.1537/ase.04S004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zachos J. Trends, Rhythms, and Aberrations in Global Climate 65 Ma to Present. Science. 2001;292:686–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1059412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bibi F, et al. Early evidence for complex social structure in Proboscidea from a late Miocene trackway site in the United Arab Emirates. Biol. Let. 2012;8:670–673. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lister AM. The role of behaviour in adaptive morphological evolution of African proboscideans. Nature. 2013;500:331–334. doi: 10.1038/nature12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.O’Connell-Rodwell CE. Keeping an ‘ear’ to the ground: seismic communication in elephants. Physiology. 2007;22:287–294. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00008.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Benoit J, Merigeaud S, Tabuce R. Homoplasy in the ear region of Tethytheria and the systematic position of Embrithopoda (Mammalia, Afrotheria) Geobios. 2013;46:357–370. doi: 10.1016/j.geobios.2013.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cerling TE, Harris JM, Leaky MG. Browsing and Grazing in Elephants: The Isotope Record of Modern and Fossil Proboscideans. Oecologia. 1999;120:364–374. doi: 10.1007/s004420050869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cerling, T. E., Harris, J. M. & Leaky, M. G. Environmentally Driven Dietary Adaptations in African Mammals in A History of Atmospheric CO2 and its Effects on Plants, Animals, and Ecosystems. Ecological Studies (eds Ehleringer, J. R. et al.), 258–272 (Springer, New York, 2005).

- 91.Peters, R. H. The Ecological Implications of Body Size (Cambridge University Press, 1983).

- 92.Sander PM, et al. Biology of the sauropod dinosaurs: the evolution of gigantism. Biol. Rev. 2010;86:117–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Radinsky L. Evolution of Brain Size in Carnivores and Ungulates. Am. Nat. 1978;112(987):815–831. doi: 10.1086/283325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huang S, et al. Mammal body size evolution in North America and Europe over 20 Myr: similar trends generated by different processes. Proc. Roy. Soc. B. 2017;284:20162361. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data necessary to reproduce this research are provided with the manuscript.