Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the utility of a novel discharge tool adapted for heart failure (HF) on patient experience.

Design

Semistructured interviews assessed the utility of a novel discharge tool adapted for HF; patient-oriented discharge summary (PODS-HF) at 72 hours and 30 days after leaving hospital. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Three investigators used directed content analysis to determine themes and subthemes from the narrative data.

Setting

The cardiology ward of an urban academic institution in Canada.

Participants

13 patients and caregivers completed 24 interviews. Eligible patients were >18 years and admitted with a diagnosis of HF.

Results

Analysis revealed six interconnected themes: (1) Utility of discharge instructions: how patients perceive and use written and verbal instructions. Patients receiving PODS-HF identified value in the patient-centred summarised content. (2) Adherence: strategies used by patients to enhance adherence to medications, diet and lifestyle changes. PODS-HF provides a strong visual reminder, particularly early postdischarge. (3) Adaptation: how patients incorporate changes into ‘new norms’. This was more evident by 30 days, and those using PODS-HF had less unscheduled visits and readmissions. (4) Relationships with healthcare providers: patients’ perceptions of the roles of family physicians and specialists in follow-up care. (5) Role of family and caregivers: the pivotal role of caregivers in supporting adherence and adaptation. (6) Follow-up phone calls: the utility of follow-up calls, particularly early after discharge as a means of providing clarification, reassurance and education.

Conclusion

PODS-HF is a useful tool that increases patients’ confidence to self-manage and facilitates adherence by providing relevant written information to reference after discharge.

Keywords: heart failure, quality in health care, cardiology, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study explores patient experiences following discharge using a novel patient-centred discharge instruction tool; the patient-oriented discharge summary for heart failure (PODS-HF) using directed content analysis.

The original PODS tool was cocreated with patients and families and adapted for HF.

Our study presents a unique insight into how patients and caregivers perceive and use discharge instructions.

Our study highlights the potential limitations of written instructions and what modifications may be needed to the PODS-HF tool to meet the needs of the HF population.

The study was conducted with patients discharged from a cardiology ward in an urban academic hospital in Canada, thus, generalisability to the wider HF population may be limited.

Introduction

There are over 5 million Canadians living with heart failure (HF) and 50 000 new diagnoses each year.1 Of the patients with HF discharged from hospital, 25% will be readmitted within 30 days and 50% within 6 months. Unplanned readmissions cost the Canadian healthcare service around CAD$35m annually and it is estimated that up to a quarter may be preventable.2 3 Much has been invested in interventions to improve the management and uptake of evidence-based therapies for HF, both in the inpatient and outpatient setting.4–6 While mortality benefits and modest reductions in hospitalisations have been realised over time, they have plateaued and the focus is shifting to improve transitions of care and new models of service delivery following discharge.

Canadian, American and European HF guidelines recommend teaching patients self-management strategies to control sodium and fluid intake, weigh themselves daily and recognise symptoms of worsening HF.7–9 However, patients are vulnerable during transitions of care and have poor recall of verbal instructions.10 11 Moreover, discharge summary quality has been found to impact adherence to discharge instructions.12 More recently, efforts to understand readmissions have shifted to a more patient-centric approach for understanding the experiences of patients and their families as they transition from hospital to home.13 14 Government incentives to reduce readmissions, length of stay and improve follow-up care, have formed part of health system funding reform.15 Such incentives, alongside research studies, have led to the development of discharge tools designed with patients and caregivers to improve patient experience. While patient engagement and self-efficacy can be improved through the use of media or visual aids, few studies have examined the impact of such interventions on adherence, healthcare utilisation and patient experience.16

A Canadian group recently partnered with patients and caregivers to codesign an individualised, freely available, written discharge instruction tool, the patient-oriented discharge summary (PODS), which can be used to engage patients when reviewing discharge instructions.17 An early adopter study demonstrated usability and feasibility with PODS currently in use across healthcare institutions in Ontario.18 The utility of PODS to improve transitions of care for patients with HF, however, is still not known. We adapted PODS for HF and in this paper, describe the utility of this tool based on patient experiences in a 30-day period following a hospitalisation for HF.

Methods

Design

Directed content analysis was used to determine themes from transcripts of telephone interviews conducted with patients discharged after an admission with HF. Directed content analysis draws on existing theory or research to develop an initial coding scheme prior to analysis and then the scheme is refined by adding additional codes and themes as the analysis proceeds. In this way, existing theory can be supported and extended.19 Three independent researchers participated in an iterative process of coding, reviewing and analysing the interviews.

This manuscript is prepared in accordance with the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.20

Patient and public involvement

Patients and caregivers were involved in the design process of the original PODS content and in the adaptation of PODS-HF; the categories it contained; colours and the timing of its delivery. All participants consented in writing to the study, including the publication of findings.

Approach

This qualitative analysis is part of a larger mixed-methods project which took place between December 2016 and June 2017 which used the model for improvement to adapt and implement PODS for HF.21 Only the qualitative results are presented in this paper and the descriptive analyses comparing preintervention and postintervention quantitative data are described in detail elsewhere. (TS: ’Feasibility and performance of a patient-oriented discharge instruction tool' Article under review). The first author (TS) was a cardiology fellow undergoing graduate level studies in quality improvement. Other authors are experts in care transitions (KO), qualitative research (SH-G, CY) and complex care models and improvement (RSB). Two of the authors were involved in the original PODS design and evaluation for usability and feasibility (KO and SH-G).16 18 Eligible patients were unknown to all study authors and only TS had contact with participants.

Participants

A purposeful sampling strategy was used where study participants who met eligibility criteria were identified and approached face to face by the study lead (TS). Eligible participants included patients >18 years with a primary diagnosis of HF admitted to the general cardiology ward of an academic institution. Patients were excluded if they had cognitive impairment, did not speak English, did not have a telephone, were transferred to another ward, service or facility or had a survival prognosis less than 3 months.

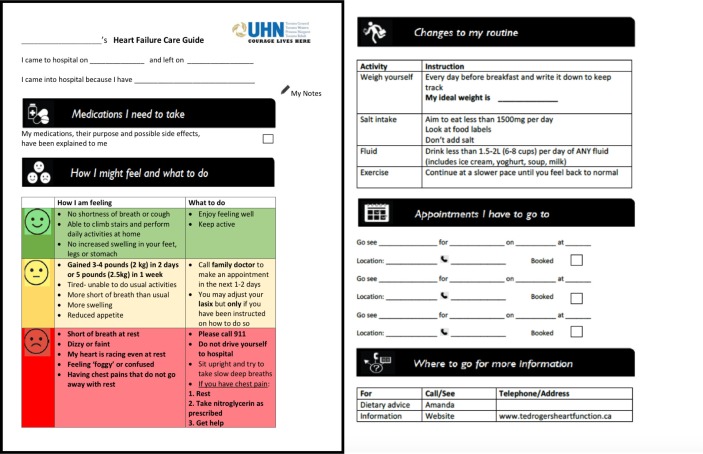

All participants received a copy of PODS-HF (figure 1) on admission and follow-up telephone calls were performed at 72 hours and 30 days following discharge by TS. The electronic patient record was accessed for missing outcome data when patients could not be reached.

Figure 1.

Final PODS-HF design (front on left, back on right).

Patient demographics included age, sex, date of admission, education level, who they live with, use of homecare services and a measure of health literacy based on a patient’s capacity to understand health information and fill out health-related forms.22

The telephone calls consisted of a structured and semistructured qualitative interview component at 72 hours and 30 days following discharge. Questions were designed in accordance with a previous care transition study.23 The structured interview collected for use in the quantitative study assessed items related to the delivery of PODS-HF; patients’ understanding of instructions given at time of discharge as well as a subjective Likert scale of satisfaction. The semistructured questions used for the qualitative piece of this study elicited experiences related to understanding and use of discharge instructions with the PODS-HF. All telephone interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. Initial and emerging themes from the interviews were analysed using directed content analysis.19 The research team met to discuss themes emerging from the transcripts and modified the interview guide iteratively to provide more directed focus on these themes. Two investigators (TS and CY) independently reviewed transcripts to develop a coding scheme and a secondary analysis was performed to determine consistency and breadth before coding all interviews to determine recurrent and emerging subthemes. Quotations within the transcripts highlighting each theme and subtheme were coded, reviewed and analysed. Triple coding of the data with a third investigator (KO) with all original transcripts ensured agreement of major themes and subthemes. All investigators used a process of manual coding. As a final step to decrease bias, inter-rater reliability was achieved using investigator triangulation by cross-comparison of themes for all team members at each meeting.24

Results

Participant characteristics

Overall, 24 telephone interviews were conducted with 13 patients recruited to the study (5 patients in the preintervention group and 8 in the postintervention group). One patient underwent cardiac transplantation before 30 days and another could not be contacted for the 72 hours interview. Interviews conducted within 72 hours following discharge were undertaken a mean of 3.8±1.4 days following discharge and 30-day interviews were conducted on average 33±4.8 days following discharge. One set of interviews were conducted with a caregiver. Three patients received a new diagnosis of HF, the majority had a pre-existing diagnosis. Respondents were predominantly male (85%), young (average 58 years) and mostly educated at a college or university level. Only two of the postintervention cohort lived alone, the remainder lived with spouses and described themselves as independent (80% of the pre-PODS and 75% of the post-PODS group).

Importantly, postintervention patients reported a higher rate of having received information in writing about signs and symptoms to watch out for and what to do about them (100% vs 40% preintervention, p=0.045). The postintervention group also reported higher rates of adherence with diet (100% vs 60%) and exercise (100% vs 67%) at 30 days and the need for unscheduled visits also reduced in the postintervention group (29% vs 40%) but were not statistically significant.

Qualitative themes

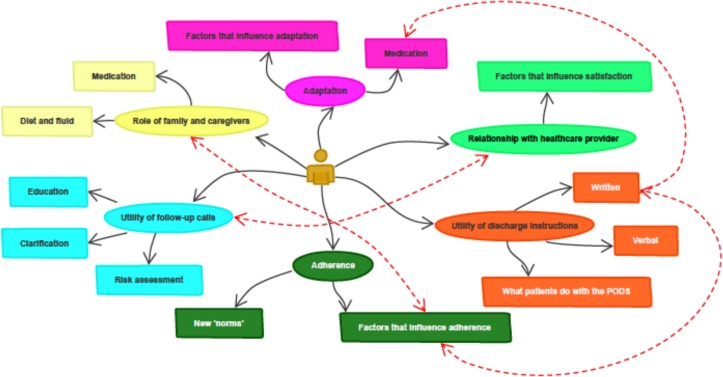

The narrative dataset from the semistructured interview questions revealed six key interconnected themes (in italics) and subthemes (in bold) in relation to the utility of discharge instructions for patients with HF (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Interconnected themes derived from the narrative data.

Utility of discharge instructions

The first theme refers to the utility of discharge instructions during usual care (pre-PODS-HF) in comparison to the utility of the PODS-HF instructions. Verbal instructions at our institution are not standardised and delivered at the discretion of the healthcare provider, on the day of discharge. Written instructions consist of a printed electronic discharge summary created from an electronic template, which can ‘pull’ laboratory investigations and imaging results directly from the reporting software. There is a section for patient instructions, however, this is buried within a detailed 5–7-page document containing acronyms and medical jargon. In contrast, the PODS-HF is a short document with instructions directed to the patient.

Verbal discharge instructions make up the first subtheme on this topic and were frequently perceived as rushed, overwhelming or incomplete. Several patients in the preintervention group reported feeling as though staff could take extra time to explain things more fully at the time of discharge, as illustrated in this excerpt:

’maybe if somebody would kind of sit down and spend 5 or 10 min to go through the things, sort of separately, that would be a good thing.' (72 hours Pre-PODS-HF)

The second subtheme of written instructions was perceived by 60% of preintervention patients as being more directed at the next healthcare provider, with several patients commenting that the written content was not relevant to them or contained things they could not understand:

’There’s a lot of stuff they put on here that’s stuff I don’t understand, but it’s for someone else to look at like my doctor so…?' (72 hours pre-PODS-HF)

This perceived lack of relevance was reflected in a third subtheme of how patients use the written discharge instructions. Patients reported filing their paperwork away once home. In contrast, in the group receiving PODS-HF, particularly, the two patients with a new diagnosis of HF, found the PODS format of written discharge instructions particularly useful, as is illustrated by this excerpt:

’you know the best piece of paper they gave me, the one that is colourful. That’s very important for people who never had any kind of heart failure, who don’t even know what symptoms to look out for, when to call 911 when you’re not doing well…. Because if people never had any kind of heart failure, then they don’t know…, so it’s what you gave me it’s very helpful for someone who leaves the hospital, in one piece of paper, they can see.' (72 hours post-PODS-HF)

This subtheme links to the themes of adherence and adaptation discussed below. Patients in both groups reported keeping written materials, though often did not refer to them within the first few days. By 30 days, the majority of patients had looked over their discharge papers. Patients in the PODS-HF group more often described using them as a visual reminder, particularly within 72 hours; placing the sheet in a prominent place, such as on a refrigerator, a bedside table or kitchen bench. Additionally, two patients in the PODS-HF group planned to take the sheet with them to their family doctor to facilitate the visit, anticipating, that the doctor would not have received a copy of the discharge information.

Adherence

This theme highlights the ways in which patients use and follow-through with discharge instructions and links to the next theme of adaptation. Though PODS-HF provides an additional area for notes on medications to be written, this area was not used frequently. It was the additional medication chart provided (routinely) to patients that was most often commented on in aiding in postdischarge adherence. The majority of patients reported using this medication list, particularly in the early post-discharge period, while they are in the process of adapting their routine. By 30 days, however, the reliance on this visual reminder for medication adherence was less:

’I know what to take, I don’t really have to look at the chart anymore.'

Changes to diet and fluid intake are key principles in the non-pharmacological management of HF, and are arguably, the elements most under the influence of the patient and caregiver. All patients in both preintervention and postintervention groups discussed dietary modifications at length in the early follow-up calls, and it dominated the narrative of newly diagnosed patients. It was also a frequent topic in the 30-day calls, but from a more reflective standpoint. Our data suggests it was the individual teaching received on the ward which had the greatest influence on dietary adherence, with a strong visual reminder provided by PODS-HF of the maximum recommended total daily sodium intake and overall daily fluid restriction. Patients recalled the group or individual teaching they received on the ward and became more aware of the salt content of foods they consumed as illustrated in this excerpt:

’it’s just opened my eyes to the amount of sodium and places I used to go like X…and I was just appalled when I saw that their nutrition information, this breaded chicken patty had like, 2000 mg of salt, which to me is unbelievable.' (72 hours post PODS-HF)

Patients voiced difficulties with food preparation because most of the packaged food they previously relied on as being too salty and have learnt to cook from ‘scratch’. Others reported avoiding some foods completely in order to reduce salt intake. This theme also links to the Role of family and Caregivers theme discussed below. Patients with support often drew on them in early stages after discharge to help with medications and dietary modifications. Moreover, younger patients reported feeling antisocial effects of dietary restriction more readily. A patient reported avoiding recreational events after discharge, because of the temptation, and feeling socially isolated as a consequence. Frequently reflected in our cohort, was a desire to be compliant with the recommendations provided by the hospital, with all patients detailing the concessions they were making at the early interviews and proudly reflecting on the sustainable changes they had discovered by trial and error at the 30 day calls:

’I enjoy it, I guess you could say, looking for recipes that are within it and finding ways of making things tasty without the salt…I see it as a bit of a challenge and I like to do it. I’ve got my husband on board there to eating similarly, as it’s a good diet for anybody really.' (30 day pre-PODS-HF)

Adaptation

Newly diagnosed patients and preintervention patients reflected a sense of anxiety around going home, as illustrated in the excerpt below:

’that’s the one thing I knew about being in the hospital, as yukky as I was feeling, I always knew that help was just…you know…pressing the button… So, I was kind of nervous about going home, because I thought what if that happens and there’s no medical staff around. That was the first day or so after, and then I started to feel a little better. I started to worry about that less.' (72 hours pre-PODS-HF)

Adapting to new routines was most challenging for newly diagnosed patients, as they have to make the most accommodations. The subtheme of factors that influence patients’ ability to make these shifts in routine, included things such as the support of family and caregivers and time off work to establish new routines. Early in transitions, patients described being busy adjusting to being home. Often, they had not looked over their discharge papers, instead making arrangements for medications and resting after their hospital stay. Several patients related how sleeping patterns had shifted as they caught up on sleep once home:

’I’m sleeping really well, I haven’t really slept well in 6 months!'

Most patients described needing to change their routine to accommodate medication schedules, either due to altered sleeping habits (improvement in HF symptoms, catching up on sleep lost in hospital) or by returning to work:

'…I’m taking my medications, but I don’t take them exactly on time…I was up half the night…because I just couldn’t sleep and then I was sleeping ‘til noon and I just took my medications at that time…and I only just took my weight…' (72 hours pre-PODS-HF)

At 30 days, many patients reflected how they had adapted their routines to support necessary changes, by developing new norms which emerged as a second subtheme. One patient described how he now walks to a pharmacy every day in order to check his blood pressure and weight while simultaneously getting the exercise recommended by his physician:

'… it gives me a reason to go out walking…it’s a good thing. And then I can email the result to my computer and keep it.' (30 days post PODS-HF)

Patients who were most successful in making changes and developing new norms had a sense of gravity about their condition:

’what choice do I have? Half my heart is dead…' (30 days post PODS-HF)

Role of family and caregivers

None of our patient population received publicly funded homecare and the majority (11 of 13) of patients lived with spouses or other family members. These informal caregivers play an integral role supporting the other themes of adaptation and adherence by helping to obtain, dispense and supervise medications; helping to prepare salt restricted meals; coaching and reassurance, as illustrated in the following excerpts:

’I feel very fortunate, because I’ve got my husband here all the time and he’s just, picked up the slack when I just couldn’t do it.' (72 hours pre-PODS-HF)

'…basically, …cooking… …washing my clothes, you know, keeping an eye on me, making sure I’m ok. Sometimes I’m in the washroom and she’ll come and check on me, make sure I’m ok, something like that.' (72 hours post PODS-HF)

Caregivers have a pivotal role in helping patients get to follow-up appointments and providing another set of ears while listening to verbal instructions. The caregiver we interviewed supported a role for PODS-HF as an important reference for the caregiver:

’I know that you can be quite scattered when you get home and you’ve been in a structured environment, and someone else has been looking after all the meds and looking after everything, and if it’s a first experience for you it could be quite un-nerving…. I could quite see how something like this, where you could jot it down, you would need a little info, you know, when you got out of there' (72 hours post PODS-HF caregiver)

Caregivers also play a crucial and active role early on in ‘picking up the slack’ in the first few days postdischarge, and subsequently have a more supportive role towards 30 days.

Relationship with healthcare providers

When asked about adherence to postdischarge follow-up many patients in our study perceived their specialist to be the most important person to follow-up with, as opposed to other scheduled or recommended providers in the patients’ circle of care, as illustrated by this statement:

'…he’s not really specialised in the stuff (the cardiologist) are specialised in, you know, he’s specialised in general stuff…'

Several patients reported in the early postdischarge period if they were not feeling well, that the first point of contact would be their specialist. Other patients expressed feelings of dissatisfaction with postdischarge primary care, either with their ability to get a timely appointment, or obtain a family doctor after a period of good health:

’to follow-up with my family doctor is not the easiest thing,'

’He told me I can’t really visit, as I am not a patient anymore. I went there once 4 years ago to follow up on shots.'

Or of greater concern, regarding a poor relationship;

’I’m kind of fed up with my family doctor…he doesn’t care about anything, I don’t know why I bother going to see him.'

A subtheme of factors that influence satisfaction with healthcare providers emerged and included topics such as ease of communication and ability to make appointments in a timely fashion. In addition, clinicians who took the time to explain medical terms and provide additional information were highly valued. Patients were highly satisfied with their hospital care, as reflected in the consistently high satisfaction scores (>8 on a scale of 1–10). Patients benefited from the in-house dietician and education sessions and appreciated the one-on-one pharmacist teaching and medication lists. Continuity of care appeared to be a factor associated with satisfaction. This was particularly true for patients who had follow-up clearly arranged and written down before leaving the hospital and in those who received follow-up calls.

Follow-up calls

The additional role of a telephone call for conducting interviews for data collection was not identified a priori, but emerged as an important major theme in our HF cohort. Three subthemes emerged from the transcribed data on this theme: clarification, education and risk assessment. The interviewer was a cardiologist with expertise in HF who was asked to clarify medical terminology and educate during the majority of calls, as illustrated in this excerpt discussing the implications of a reduced ejection fraction and subsequent follow-up written on the discharge summary:

’Oh, that’s kind of what I needed, someone to explain how long it will take (for heart function to recover), It’s nice to have somebody explain that to me. The medical team was too busy by the time I go' (72 hours post PODS-HF and new diagnosis)

There were also opportunities to clarify instructions for follow-up. In several instances, details of scheduled follow-up on the electronic system were confirmed during the call and clarification given to clinic and investigation locations. In one case, this averted a potential clinic no-show. Some issues that arose with clarification provided opportunity for process improvement:

on the discharge paper, there is the number to call back. But I called that number and it is not in service…

Additionally, there were many opportunities for real-time medication reconciliation and to clarify and educate around fluid restrictions. Follow-up calls also had the effect of providing additional information and in several cases enabled a risk assessment to be carried out for symptoms of recurrent HF.

Follow-up calls also provided reassurance and coaching for patients, linking with other themes of adaptation, adherence and relationship with healthcare providers. Though the interviewer introduced the interview as being for data collection purposes, all patients expressed that they found the phone call useful:

’Yes! I am very glad we had this conversation with you and talking to you and the tips and the advice, you know, and the questions themselves, I am really glad you called it was great' (30 day post PODS-HF and new diagnosis)

There was a temporal distinction between the type of information being provided during the calls. At the 72 hours call, more clarification was being provided as to discharge instructions, follow-up plans and medication, as well as reinforcement of dietary and fluid restrictions. The need for such reinforcement was less at the 30-day call.

Discussion

Our study revealed six interconnected themes, which highlight the utility and limitations of PODS-HF for patients transitioning home from an admission for HF. This study identifies and supports themes which have been previously described to influence a successful transition, including the role of written information, adaptation, family or caregivers and the relationship with healthcare providers.13 14 23 Our results provide insight into the needs of patients with HF as they adjust to life outside the hospital and how they acquire the necessary self-management skills using information they are provided with at, or just after, discharge.

The content and quality of discharge information has been shown to be crucial, and its perceived relevance can impact adherence and readmission rates.12 25 The day of discharge is busy and often overwhelming for patients and a significant proportion of verbal information provided at the time of discharge is poorly retained.11 Our first theme, ‘utility of written discharge instructions’, supports the use of written, summarised discharge instructions for HF, that are patient centred, individualised and relevant to issues faced by patients after discharge; namely those of managing medications, assessing symptoms and deciding what to do about them, organising follow-up and navigating the health system.14 Guidelines, such as the American Heart Association (AHA) statement on transitions of care in HF, highlight the importance of education, self-management strategies, sodium restriction, medication and timely follow-up in the context of more individualised management programs.26 Patients in our cohort liked the coloured single page summary and used PODS-HF along with their medication chart as visual aids to help them adhere to discharge instructions, as reflected in our second theme. The use of PODS-HF for improving self-reported adherence to diet and exercise recommendations and confidence to self-manage may facilitate successful and early adaptation to new norms. ‘Adaptation’, and ‘role of family and caregivers’, our third and fourth major themes, have been previously reported as important steps facilitating self-management for patients with HF.27 28

Follow-up telephone calls, though not intended as part of the PODS-HF intervention, emerged as an important and potentially therapeutic adjunct to postdischarge follow-up. The calls provided additional clarification and education and afforded an opportunity to provide additional resources or conduct risk assessment for patients still experiencing symptoms. The effect of follow-up calls in fostering the relationship with healthcare providers, providing early access and enhancing continuity of care and adherence has been previously described,29 30 however, their impact on health outcomes has been inconclusive and not well described in patients transitioning home with HF.31 Additionally, the calls highlighted opportunities for process improvement, for example, the provision of out of service telephone numbers, and issues with medication dispensation that could be more patient centred. This links with the shift to patient-centric care models that mandate patient and family feedback to refine and improve healthcare delivery. This theme, along with the other five themes, suggests that the usefulness of PODS-HF may be influenced by individual adaptation, the role of family or other caregivers, healthcare provider relationship and access to postdischarge care.

Previous studies have examined the quality of discharge summaries from the limited perspective of the healthcare provider.12 32 A particular strength of this study is that we looked specifically at the utility of written discharge instructions from the patient and caregiver perspective. Moreover, the intervention is a novel tool designed and improved on with patients and caregivers, which is a limitation of prior studies.16 17 Lastly, themes identified strengthen previous quantitative studies by adding important context as to why patient-centred interventions may improve postdischarge outcomes.

Limitations of the study include its non-randomised design, small size and implementation on one specialised ward. This may have led to the recruitment of patients more likely to succeed after a hospitalisation, limiting generalisability to patients who may stand to benefit even more from the intervention, for example, those with cognitive impairment or requiring additional support to transition home. In addition, the follow-up call was provided by a specialist thus introducing a potential source of bias to the participants’ responses. Further study should clarify the independent effect of the postdischarge phone call among participants receiving the PODS-HF.

Conclusion

Themes identified in this paper support previous findings and highlight new insights into the challenges, adaptive behaviours and opportunities to improve transitional care for patients and families living with HF, particularly through the use of individualised written instructions. PODS-HF provides patients and caregivers with patient-centred relevant information to reference for HF. Further study with a larger and broader range of patients with HF is required to determine PODS-HF ability to reduce postdischarge healthcare utilisation when compared with usual discharge processes. Together with early follow-up calls, PODS-HF may help patients to make changes that are timely, sustainable and effective.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Heather Ross and the staff and patients of the Peter Munk cardiac center for their support of this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: TS is a HF cardiologist who obtained, analysed and interpreted data and participated in study design. CY is a research assistant who participated in data analysis and interpretation of narrative transcripts. KO is a general internist who provided substantial contribution to the conception and design of the study, analysed data and was involved in the drafting and revision of the manuscript. SH-G is a researcher who participated in data analysis and drafting and revision of the manuscript. RSB is a cardiologist who provided substantial contribution to the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript and was involved in the study design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Formal research ethics approval was waived by the University Hospital Network Research Ethics Board in December 2016 and patient data stored in accordance with institutional policies.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Foundation HaS. Report on the health of canadians. 2016. http://www.heartandstroke.ca/-/media/pdf-files/canada/2017-heart-month/heartandstroke-reportonhealth-2016.ashx?la=en; (Accessed 13 Apr 2017).

- 2. Tran DT, Ohinmaa A, Thanh NX, et al. The current and future financial burden of hospital admissions for heart failure in Canada: a cost analysis. CMAJ Open 2016;4:E365–E70. 10.9778/cmajo.20150130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Walraven C, Bennett C, Jennings A, et al. Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: a systematic review. CMAJ 2011;183:E391–402. 10.1503/cmaj.101860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff 2001;20:64–78. 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fonarow GC. Strategies to improve the use of evidence-based heart failure therapies: OPTIMIZE-HF. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2004;5(Suppl 1):S45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fonarow GC, Albert NM, Curtis AB, et al. Improving evidence-based care for heart failure in outpatient cardiology practices: primary results of the Registry to Improve the Use of Evidence-Based Heart Failure Therapies in the Outpatient Setting (IMPROVE HF). Circulation 2010;122:585–96. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.934471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:e147–239. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2129–200. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Howlett JG, McKelvie RS, Costigan J, et al. The 2010 Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure update: Heart failure in ethnic minority populations, heart failure and pregnancy, disease management, and quality improvement/assurance programs. Can J Cardiol 2010;26:185–202. 10.1016/S0828-282X(10)70367-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome--an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med 2013;368:100–2. 10.1056/NEJMp1212324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rao M, Fogarty P. What did the doctor say? J Obstet Gynaecol 2007;27:479–80. 10.1080/01443610701405853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Al-Damluji MS, Dzara K, Hodshon B, et al. Hospital variation in quality of discharge summaries for patients hospitalized with heart failure exacerbation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2015;8:77–86. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cain CH, Neuwirth E, Bellows J, et al. Patient experiences of transitioning from hospital to home: an ethnographic quality improvement project. J Hosp Med 2012;7:382–7. 10.1002/jhm.1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cawthon C, Walia S, Osborn CY, et al. Improving care transitions: the patient perspective. J Health Commun 2012;17(Suppl 3):312–24. 10.1080/10810730.2012.712619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Health.gov. Health system funding reform ontario ministry for health and long term care 2017. 2019. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ecfa/funding/hs_funding.aspx

- 16. Okrainec K, Lau D, Abrams HB, et al. Impact of patient-centered discharge tools: a systematic review. J Hosp Med 2017;12:110–7. 10.12788/jhm.2692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hahn-Goldberg S, Okrainec K, Huynh T, et al. Co-creating patient-oriented discharge instructions with patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers. J Hosp Med 2015;10:804–7. 10.1002/jhm.2444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hahn-Goldberg S, Okrainec K, Damba C, et al. Implementing patient-oriented discharge summaries (PODS): a multisite pilot across early adopter hospitals. Healthc Q 2016;19:42–8. 10.12927/hcq.2016.24610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014;89:1245–51. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berwick DM. A primer on leading the improvement of systems. BMJ 1996;312:619–22. 10.1136/bmj.312.7031.619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Powers BJ, Trinh JV, Bosworth HB. Can this patient read and understand written health information? JAMA 2010;304:76–84. 10.1001/jama.2010.896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hahn-Goldberg S, Jeffs L, Troup A, et al. "We are doing it together"; The integral role of caregivers in a patients' transition home from the medicine unit. PLoS One 2018;13:e0197831 10.1371/journal.pone.0197831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ. An array of qualitative data analysis tools: a call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly 2007;22:557–84. 10.1037/1045-3830.22.4.557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Albrecht JS, Gruber-Baldini AL, Hirshon JM, et al. Hospital discharge instructions: comprehension and compliance among older adults. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:1491–8. 10.1007/s11606-014-2956-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Albert NM, Barnason S, Deswal A, et al. Transitions of care in heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:384–409. 10.1161/HHF.0000000000000006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schulman-Green D, Jaser SS, Park C, et al. A metasynthesis of factors affecting self-management of chronic illness. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:1469–89. 10.1111/jan.12902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sayers SL, Riegel B, Pawlowski S, et al. Social support and self-care of patients with heart failure. Ann Behav Med 2008;35:70–9. 10.1007/s12160-007-9003-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cochran VY, Blair B, Wissinger L, et al. Lessons learned from implementation of postdischarge telephone calls at Baylor Health Care System. J Nurs Adm 2012;42:40–6. 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31823c18c9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nelson JR. The importance of postdischarge telephone follow-up for hospitalists: a view from the trenches. Am J Med 2001;111:43–4. 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00970-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mistiaen P, Poot E. Telephone follow-up, initiated by a hospital-based health professional, for postdischarge problems in patients discharged from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;4:CD004510 10.1002/14651858.CD004510.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Horwitz LI, Jenq GY, Brewster UC, et al. Comprehensive quality of discharge summaries at an academic medical center. J Hosp Med 2013;8:436–43. 10.1002/jhm.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.