Abstract

Introduction

Evidence indicates a bidirectional relationship between poor sleep and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). While AD may lead to disruption of normal sleep, poor sleep in itself may play a causal role in the development of AD by influencing the production and/or clearance of the amyloid-beta (Aβ) protein. This led to the hypothesis that extended periods (>10 years) of sleep loss could lead to Aβ accumulation with subsequent cognitive AD-related decline. This manuscript describes the methodology of the SCHIP study, a cohort study in maritime pilots that aims at investigating the relationship between prolonged work-related sleep loss, cognitive function and amyloid accumulation among healthy middle-aged maritime pilots, to test the hypothesis that prolonged sleep loss increases the risk of AD-related cognitive decline.

Methods

Our study sample consists of a group of healthy middle-aged maritime pilots (n=20), who have been exposed to highly irregular work schedules for more than 15 years. The maritime pilots will be compared to a group of healthy, age and education-matched controls (n=20) with normal sleep. Participants will complete 10 days of actigraphy (Actiwatch 2, Philips Respironics) combined with a sleep-wake diary. They will undergo one night of polysomnography, followed by comprehensive assessment of cognitive function. Additionally, participants will undergo amyloid positron emission tomography-CT to measure brain amyloid accumulation and MRI to investigate atrophy and vascular changes.

Analysis

All analyses will be performed using IBM SPSS V.20.0 (SPSS). We will perform independent samples t-tests to compare all outcome parameters.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol was approved by our institutional ethical review board (NL55712.091.16, file number 2016–2337) and will be performed according to Good Clinical Practice rules. Data and results will be published in 2020.

Keywords: alzheimer’s disease, amyloid accumulation, neurodegeneration, cognitive function, sleep

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The unique cohort of maritime pilots allows the prospective assessment of the effect of chronic exposure to irregular maritime work schedules on cognitive functioning and amyloid accumulation; the unique cohort might also be a limitation to the study, because they might not be comparable to the control group to some extent (eg, IQ, work environment, personality).

Since we include participants up to 60 years, we will have to take possible ageing effects on sleep into account while interpreting our results.

In addition to imaging techniques (positron emission tomography-CT and MRI), we use sensitive and well-validated neuropsychological tests to measure different domains of cognitive function (reaction time, visual memory, executive function, semantic memory and episodic memory).

We will make use of four different instruments to obtain a comprehensive measure of sleeping patterns (two subjective and two objective ones).

Our results could give rise to new treatment opportunities, that aim at sleep improvement and management in order to prevent or reduce amyloid accumulation and in turn delay or even prevent the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent cause of dementia and currently affects approximately 36 million people worldwide.1 Thus far, no successful treatment is available. One of the major contributors to the neurodegeneration seen in the brains of AD patients is amyloid-beta (Aβ).2 The amyloid cascade hypothesis characterises amyloid accumulation as the fundamental initiating pathway for the development of AD.3 The reason why amyloid accumulates, however, is not clear yet. Recent evidence suggests that poor sleep might be one of the risk factors for amyloid accumulation and thereby increases the risk of AD development.4 Elderly people suffering from insomnia are more likely to develop AD compared with controls without insomnia.4 Furthermore, disrupted circadian rhythm among otherwise healthy individuals5 and sleep-disordered breathing disorders6 increase the chance of developing AD later in life. Poor sleep quality specifically has been shown to increase the risk of AD among older individuals.7–11 A recent meta-analysis of epidemiological studies found that poor sleep increased AD risk and that approximately 15% of cases of AD in the population might be attributable to sleep problems.12

The effect of acute sleep deprivation on AD has been shown in both rodent and human studies, which investigated the effect of sleep and sleep deprivation on Aβ levels. Rodents and humans show fluctuations in Aβ levels over a 24-hour rhythm, where levels rise during wakefulness and decrease during sleep.13 14 Following acute sleep deprivation, the drop in Aβ levels that would normally occur after sufficient sleep the following morning, was absent. Based on this evidence, chronic sleep disturbances might lead to a pronounced accumulation of Aβ in the brain, which in turn increases the risk to develop AD.

To date, observational and epidemiological studies have identified a relationship between poor sleep and the risk of developing AD. Experimental research has found that sleep deprivation and Aβ levels are related in both animals and humans. However, the direct effect of chronic partial sleep deprivation and its consequences on cognitive functioning, particularly the risk to develop AD later in life, has not been studied before.

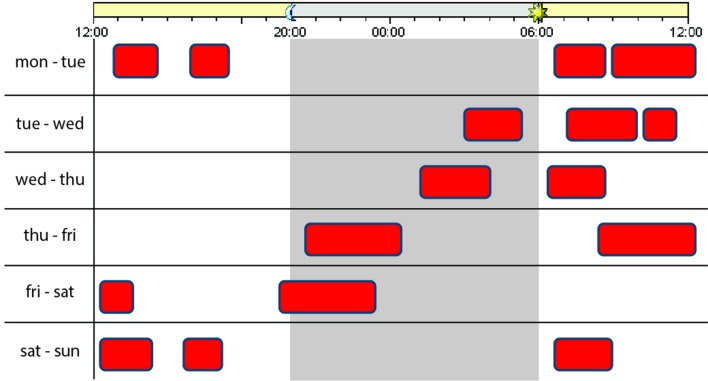

In this article, we describe the methodology and the participant cohort of the Sleep-Cognition Hypothesis In maritime Pilots (SCHIP) study. We designed the SCHIP study in order to investigate the effect of long-term work-related sleep loss on cognitive function, structural brain changes and amyloid accumulation by using a unique cohort of healthy subjects with highly irregular shift work as maritime pilots. Because of the bidirectional nature of the relationship between sleep and AD, in which poor sleep is a symptom of the disease that precedes the clinical manifestation of AD, but might also be a risk factor that potentially contributes to the development of the disease, it is especially important to investigate the effects of sleep loss, caused by an external factor (work) and not by an intrinsic sleeping disorder (such as insomnia) that could be AD related. Therefore, participants in this study were selected based on their prolonged exposure to irregular maritime work schedules. In this maritime pilot group, sleep loss is characterised as a combination of sleep deprivation, sleep restriction and sleep fragmentation or disruption. We will refer to these using the umbrella term ‘sleep loss’ throughout. An example of an individual working schedule from maritime pilot is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example maritime pilot working schedule. Working hours indicated in red.

Results and insights born from the SCHIP study could shed more light on sleep disturbance as one of the risk factors to develop AD and contribute to new and improved treatment strategies. In the SCHIP study, we will investigate whether maritime pilots perform worse on cognitive assessment in comparison to a healthy control group and whether they have evidence of elevated brain amyloid concentrations and structural brain changes.

Methods and analysis

Participants

Considering that this study is a proof-of-principle study, it is not possible to establish the exact effect size of the change in cognitive function we expect to see between the maritime pilots and the healthy controls.

To account for possible 10% withdrawal, we chose to have n=20 participants in each arm.

In order to reach enough power to detect clinically relevant differences regarding the results of the positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) scan, we performed a sample size power calculation using G Power (V.3.1.9.3).15 Reported normal values (mean and SD) for this age group in the literature vary between studies but are in the order of a mean standard uptake value (SUV) between 0.9 and 1.1 with SDs in the range of 0.05–0.2. We define a relevant difference between maritime pilots and normal values to be 0.2 or more (an SUV of 1.3 or higher is considered as abnormal in most studies). This results in a large expected effect size (>0.8). The precise number of age-matched and education-matched subjects in the database is not known yet but is estimated to be at least 50 (between 50 and 100). We have applied a one-tailed test (it is not possible to have an SUV lower than normal values). With an alpha of 0.05 and n=20, our power is 0.95 or higher (depending on the number of normal subjects). The lower level for power (0.85) is reached with 13–15 pilots.

Based on these calculations, we will aim to recruit 20 pilots, allowing for drop-out of 5–7 pilots (either due to withdrawal of consent or artefacts in the PET-CT).

Participants will be recruited within the national organisation of Dutch Maritime Pilots (Nederlands Loodswezen). We selected the maritime pilots as a suitable study population because of their unique irregular working schedule. They are called to work depending on the number and kind of ships that arrive. In a typical 7-day work week, they have to be available 24 hours per day during which they can be called several times. This results in multiple divided short sleep periods over 24 hours during a work week, this is followed by a week off. An example of a workday of a maritime pilot is illustrated in figure 1.

The responsibility of a maritime pilot is to handle large international ships arriving by sea and to manoeuvre them into their final docking position in one of the Dutch harbours. This profession carries high responsibilities and requires accurate knowledge of the dimensions of the harbour and the ships besides technical knowledge and navigational skills. This results in irregular working schedules because guiding the ships is a time-intensive procedure, which can take hours to complete. Maintaining this schedule for more than 15 years will result in chronic exposure to sleep loss, either due to partial sleep deprivation (missing a full night of sleep due to work), sleep restriction (a much shorter night of sleep than normal) or sleep fragmentation or disruption (short periods of sleep interrupted by calls to work).

We will reach out to the whole maritime pilot community, in order to recruit pilots who are approximately 50–60 years old, with at least 15 years of uninterrupted work history as a maritime pilot.

Additional inclusion criteria are not using neuroactive medications or psychostimulants, consumption of <14 alcoholic beverages per week, a body mass index of 18–30 kg/m2 and no subjective cognitive complaints (Cognitive Failure Questionnaire (CFQ <43)). As control group, we will recruit 20 age, sex and education matched healthy adults with normal sleep indicated by a score of >5 on a subjective sleep questionnaire (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, PSQI). Inclusion of participants started in August 2018 and we expect to complete the analysis of all data in August 2020.

Experimental design

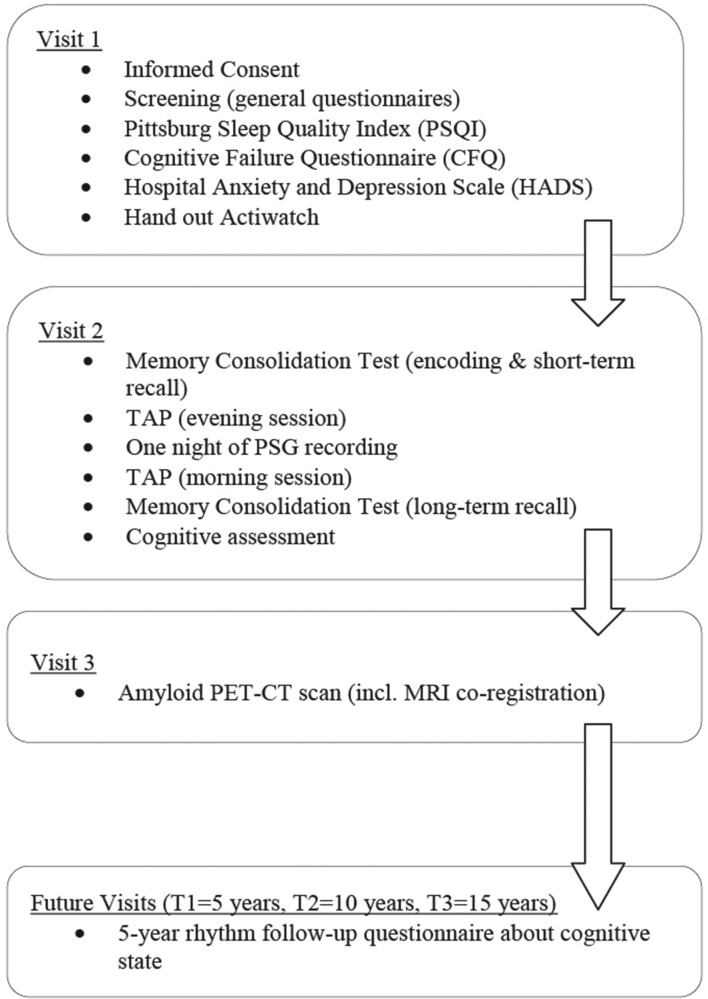

The aim of the SCHIP study is to investigate the relationship between long-term work exposure to irregular working schedules, cognitive function and amyloid accumulation among healthy middle-aged men to test the hypothesis that work-related prolonged sleep loss increases the risk of AD-related cognitive decline. In order to test this hypothesis, maritime pilots will have three visits and controls will have two visits (figure 2). During the first visit, participants will complete general questionnaires about medical history, sleeping habits and cognitive state. Approximately 10 days after the first visit has taken place, participants are invited to the sleep centre Kempenhaeghe (Heeze, The Netherlands) for the second visit. They will arrive at the sleep centre at 19:00 hours and complete a memory consolidation test (modified ‘Doors Test’) and a test for attentional performance (TAP 2.3),16 followed by overnight polysomnography (PSG). Participants wake up at their normal wake time and complete a neuropsychological assessment after breakfast around 09:00 hours.

Figure 2.

Overview experimental design. PET, positron emission tomography; PSG, polysomnography; TAP, test for attentional performance.

Visit 3 (only for the maritime pilots) will be performed at the Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen (The Netherlands), where participants will undergo a standard amyloid PET-CT to measure brain amyloid accumulation and a 3T-MRI for coregistration. Participants are scheduled in their week off in order to prevent short term effects of sleep disruption on amyloid concentrations in the brain.17 They are instructed not to eat or drink anything except from water 3 hours prior to the scan.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in this study because this study involves healthy participants.

However, the participants’ organisation contacted us due to recent evidence from the literature on the relationship between sleep and AD. They expressed their worries about their health and their own risk of developing AD considering their irregular sleep. They reported feeling very tired at the end of a work week and speculated that within their group of maritime pilots (including already retired pilots), cases of dementia occurred more frequently than expected.

Participants were also tightly involved in the design, realisation and feasibility of the study. For example, they were involved in choosing the technique to measure amyloid and expressed the preference for a PET-CT scan over cerebrospinal fluid measurements of amyloid.

Dissemination of results to participants

Results from the PSG measurements will be reported only to participants if we find abnormalities such as apnoea or sleeping disorders. This will be done by one of our sleep clinicians via telephone. Results from the PET-CT scan will be disclosed via telephone by one of our clinicians as well. This is according to the protocol that has been approved by the local ethical committee. Any incidental findings on the PET-CT and/or MRI will be disseminated as well.

Sleep measurements

In order to obtain a comprehensive measure of sleeping patterns, we will use the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) with questions about average sleeping behaviour, including the report of bedtime, get-up time, sleep latency, total sleep time, sleep disturbances (pain, breathing, etc) and use of sleep medication. The maritime pilots will be instructed to fill in the questionnaire twice, once with regard to a work week and once with regard to a week off. Additionally, all participants are asked to maintain a sleep-wake diary on a daily basis. In this diary, they have to keep track of their bedtimes, the time it took to fall asleep (sleep latency), the number of awakenings and their get up times. Furthermore, they will receive an accelerometer, the Actiwatch 2 (Philips Respironics; Eindhoven, The Netherlands), in order to obtain more objective measurements of sleeping behaviour. The Actiwatch is worn around the wrist and measures total sleep time and number of awakenings during sleep automatically based on movement. Participants are instructed to fill in the sleep diary and to wear the Actiwatch for 10 days preceding the second visit.

Cognitive assessment

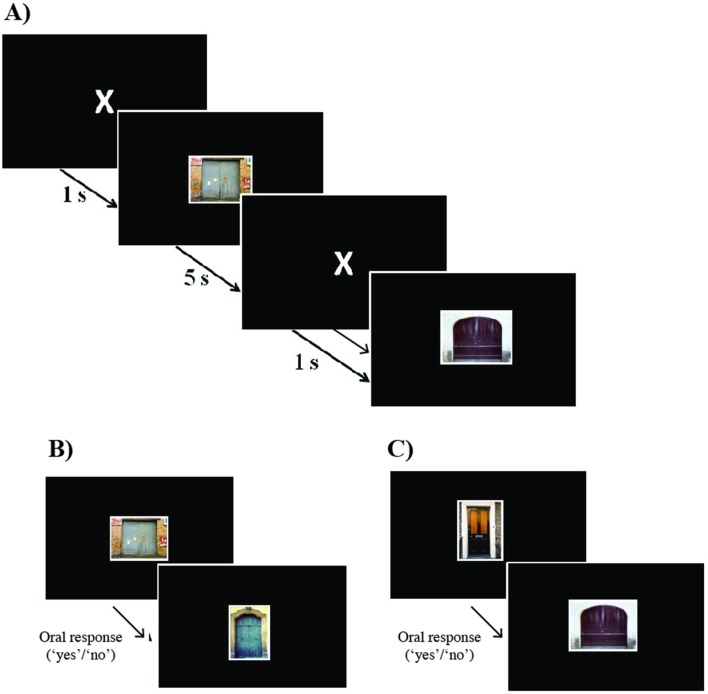

The neuropsychological assessment has been designed to measure the following cognitive domains, using validated Dutch versions of widely used neuropsychological tests. Episodic memory is assessed using the Wechsler Memory Scale-IV (WMS-IV) Logical Memory and the Rey-Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT). Working memory and executive function are measured by WAIS-IV Digit Span, Trail Making Test (TMT-A, TMT-B) and WAIS-IV digit symbol test. Semantic memory and language are assessed by letter fluency (D-A-T), semantic fluency (animal/profession naming) and the Boston Naming Test.18 Attentional performance is studied using the alertness test of the Test of Attentional Performance (TAP 2.3).16 This test is conducted twice, once in the evening around 19:00 hours and once in the morning around 09.00 hours. In order to test overnight memory consolidation, a novel paradigm was developed based on the Doors Test, a visual recognition task developed by Baddeley et al 19 and extended using a validated database of 2000 pictures of doors.20 During the encoding trial, we present 120 pictures of doors that participants are instructed to remember. All targets (doors) are presented twice in a different, pseudo-randomised order. Targets are shown for 5 s each, separated by a fixation cross presented for 1 s (figure 3). Approximately 10 min after the encoding trial, participants are presented with 30 of the original doors and 15 distracters (new pictures of doors, not presented before) that are randomly mixed. During this short-term recognition test, the task is to indicate whether the door had been presented before (oral response with ‘yes’) or not (oral response ‘no’). For the long-term delayed recall, the same procedure is applied in the morning, using the other 90 original pictures, plus 45 new distracters (figure 3). Calculating the hits and false alarms, we compute the sensitivity (A′) for short-term and for long-term delayed recall (A′=0.5+((hit-rate – false alarm rate)×(1+hit rate–false alarm rate))/(4×hit rate×(1–false alarm rate)).

Figure 3.

Memory consolidation task design. (A) Example of encoding trials—120 doors separated by fixation cross. (B) Example of short-term recognition trials (after approx. 10 min)—oral response (pressing space-bar to move to next stimulus), 30 targets and 15 distracters. (C) Example of long-term recognition trials (after one night)—oral response (pressing space-bar to move to next stimulus), 90 targets and 45 distracters.

Amyloid PET-CT scan with co-registered MRI

Brain amyloid PET-CT scan will be performed to measure amyloid load. Participants will be scanned at the Radboudumc department of Radiology and Nuclear medicine on a PET scanner (Biograph mCT, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Subjects will receive an intravenous bolus of the well-validated PET tracer 18F-flutemetamol, and static brain images will be acquired from 90 to 110 min postinjection (frames of 5 min), as recommended (see SPC; http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002557/WC500172950.pdf). The individual reconstructed PET images will be coregistered with individual structural T1 MRI scans.

The PET scans will be rated visually as positive or negative by an experienced nuclear medicine physician for the presence of amyloid depositions typical of AD. Scores will be expressed as a global SUV, which will be compared against population normative values, as earlier described.21 For quantitative purposes, grey matter volumes of interest will be defined on the individual MRIs (eg, frontal brain areas, the precuneus and hippocampus) as well as for cerebella grey matter (to assess non-specific uptake). The amyloid burden will be quantified using the standardised uptake value ratio, since it has been validated that this analysis method has comparable agreement with full kinetic modelling.22 Brain MRI will be performed on a 3 Tesla system (Magnetom Trio, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The structural T1-weighted images will be used for coregistration purposes, and to define grey matter in the volumes of interest. In addition, these scans will be used to perform volumetric measurements (eg, of the hippocampus). Also, arterial spin labelling (ASL) will be performed to measure global and regional cerebral blood flow (CBF), since reduced regional CBF is an early marker of AD. Individual anatomic MRI scans will be coregistered with the individual PET scans using the image processing platform FLS (fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk) to calculate SUV ratios. The PET-CT data will be expressed in Centiloid units to evaluate our data with historical control data as was recently validated by Battle et al.23

Future follow-up visits

Because of the insufficient knowledge about the correlation between amyloid accumulation in the brain and the actual development of AD, we decided to follow the maritime pilots in a 5-year cycle in order to monitor any cognitive changes. We will contact them three times in total, which leaves us with a maximum follow-up period of 15 years. At each time point, they will be asked to answer three questions online:

Did you develop cognitive complaints over the last 5 years? This question will be further elaborated on with the CFQ. The CFQ is a validated questionnaire that aims at detecting daily disruptions of cognitive functions. Participants are confronted with 25 statements and have to indicate how often they experience the situation that is described in the statements with a score between 0 (never) and 4 (very often).

Were you diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment during the last 5 years? If yes, when and what was the precise diagnosis?

Were you diagnosed with dementia in the past 5 years? If yes, when and what was the precise diagnosis?

If the answer is ‘yes’ to one of these questions, we will reach out to the participants for clarification.

Statistical analysis

All analyses will be performed using IBM SPSS V.20.0 (SPSS). Statistical significance is set at p<0.05, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons when appropriate, combined with reports of effect size and 95% CIs. All continuous variables will be assessed for normal distribution by inspection of histograms and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Levene’s test will be used to assess equality of variances. We will perform an independent samples t-test to compare all outcome parameters. The primary outcome for cognitive function will be the score on each test, respectively, adjusted for age and education. Regarding imaging, the primary outcome measure will be the visual read of the amyloid PET scans (positive or negative PET). Secondary outcome measurements will be quantitative PET (SUV ratios), brain volume (MRI) and CBF measurements (MRI-ASL).

Dissemination

Written informed consent will be obtained from all participants. We are planning to publish the data and results of the SCHIP study in two or three articles in 2019 and 2020.

Discussion

In this article, we presented the design and methodology of the SCHIP study. The main aim of the SCHIP study is to investigate the effect of long-term work-related sleep loss on cognition and amyloid accumulation. Since previous studies assessed sleep deprivation for only one or a few days, the SCHIP study extends these studies by investigating the effect of long term sleep loss on cognitive function and amyloid accumulation. We expect that the maritime pilots have had long-term (>15 years) exposure to work-related sleep loss, because of their work schedules and that this exposure has led to reduction in slow-wave sleep (SWS). Every slow wave observed on an electroencephalography is a pause in synaptic activity.24 Synaptic activity and Aβ levels appear strongly related, as Aβ levels increase due to synaptic activity.25 More synaptic activity is observed during wakefulness, especially in the default mode network or other highly interconnected brain areas.25 During sleep, synaptic activity is reduced, which could result in a decrease in Aβ levels in the brain.25 Therefore, sleep loss (especially poor SWS) over the course of many years could increase Aβ concentrations, which in turn could trigger AD-associated neurodegeneration and loss of cognitive function.

To test this hypothesis, we will perform extensive cognitive testing, using tests that are sensitive to subtle decline in episodic memory, which is affected early in AD. Additionally, amyloid positivity will be measured using amyloid PET-CT scans in order to explore the effect of work-related sleep loss on amyloid concentration in the brain. CBF and cerebrovascular resistance will be investigated, as reductions in blood flow and increases in resistance occur early in the AD process.26 Finally, global grey matter volume and hippocampal volume will be measured.

The unique cohort of maritime pilots will allow the prospective assessment of prolonged work-related sleep loss and its consequences for cognitive functioning and amyloid accumulation. The design of the SCHIP study presents a number of strengths. No other previous investigation has looked into the effect of chronic partial sleep deprivation on cognition in healthy men to this extent. Since sleep disorders might also be early symptoms of preclinical AD, it is especially important in this age group to investigate the effect of sleep loss due to an external factor and not due to intrinsic sleep disorders. All enrolled maritime pilots did not have any sleeping disorders and did not use sleep medication as confirmed by a general health questionnaire that was filled in on screening for participation. Furthermore, we measure different domains of cognitive function (reaction time, visual memory, executive function, semantic memory and episodic memory) using sensitive and well-validated neuropsychological tasks. In addition to testing cognitive functions, we will perform brain imaging to detect amyloid accumulation as potential consequence of sleep loss. We will make use of four different instruments to get a comprehensive measure of sleeping patterns, two subjective and two objective ones. The subjective measurements consist of the PSQI and the maintenance of the sleep-wake diary. The objective assessments include the data from the Actiwatch 2 (Philips Respironics) in addition to a night of PSG. The data from the Actiwatch can be compared with the sleep-wake diary entries. These data can then be used to verify the sleeping behaviour of participants, making sure they maintain regularity and consistency in their sleeping habits.

Results of the SCHIP study will give us more insights into the consequences of long-term work-related sleep loss on cognitive function and amyloid accumulation in an AD-related context. Our results could give rise to new treatment opportunities that aim at sleep improvement and management in order to prevent or reduce amyloid accumulation and in turn delay or even prevent the development of AD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JT was involved in setting up the study, recruiting participants, gathering baseline characteristics, analysing of first data and writing this manuscript. SO helped with setting up the study, recruitment and design of the project and writing the first draft of the manuscript. MV contributed to the design of the study. JB and MR were major contributors in choosing and designing the right PET-CT/MRI procedure and wrote part of the manuscript. RPCK contributed to selecting the right neuropsychological tests, helped with the statistical analyses of the first data and contributed to the revision of this manuscript. SO was a major contributor in setting up a collaboration with the sleeping center Kempenhaeghe (Heeze, The Netherlands) and helped revising the manuscript. JC was a major contributor in obtaining funding, setting up the study, designing the project and was extensively involved in writing and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The SCHIP study is funded by ISAO (Internationale Stichting Alzheimer Onderzoek) (grant number 15040). Additional financial resources were provided by the Radboud University Medical Center (Nijmegen, The Netherlands).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by our institutional review board (NL55712.091.16, file number 2016–2337) and will be performed according to Good Clinical Practice (GCP) rules.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, et al. . The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement 2013;9:63–75. 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jagust WJ, Mormino EC. Lifespan brain activity, β-amyloid, and Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Cogn Sci 2011;15:520–6. 10.1016/j.tics.2011.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Korczyn AD. The amyloid cascade hypothesis. Alzheimers Dement 2008;4:176–8. 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Osorio RS, Pirraglia E, Agüera-Ortiz LF, et al. . Greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease in older adults with insomnia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:559–62. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03288.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tranah GJ, Blackwell T, Stone KL, et al. . Circadian activity rhythms and risk of incident dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older women. Ann Neurol 2011;70:722–32. 10.1002/ana.22468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yaffe K, Laffan AM, Harrison SL, et al. . Sleep-disordered breathing, hypoxia, and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older women. JAMA 2011;306:613–9. 10.1001/jama.2011.1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Benedict C, Byberg L, Cedernaes J, et al. . Self-reported sleep disturbance is associated with Alzheimer’s disease risk in men. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:1090–7. 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.08.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sterniczuk R, Theou O, Rusak B, et al. . Sleep disturbance is associated with incident dementia and mortality. Curr Alzheimer Res 2013;10:767–75. 10.2174/15672050113109990134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hahn EA, Wang HX, Andel R, et al. . A change in sleep pattern may predict Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;22:1262–71. 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Potvin O, Lorrain D, Forget H, et al. . Sleep quality and 1-year incident cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults. Sleep 2012;35:491–9. 10.5665/sleep.1732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ju YE, McLeland JS, Toedebusch CD, et al. . Sleep quality and preclinical Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 2013;70:587–93. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.2334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bubu OM, Brannick M, Mortimer J, et al. . Sleep, cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep 2016;40:zsw032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kang JE, Lim MM, Bateman RJ, et al. . Amyloid-beta dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep-wake cycle. Science 2009;326:1005–7. 10.1126/science.1180962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ooms S, Overeem S, Besse K, et al. . Effect of 1 night of total sleep deprivation on cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid 42 in healthy middle-aged men: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 2014;71:971–7. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. . G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zimmermann P, Fimm B. A test battery for attentional performance. Applied neuropsychology of attention Theory, diagnosis and rehabilitation, 2002:110–51. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shokri-Kojori E, Wang G-J, Wiers CE, et al. . β-Amyloid accumulation in the human brain after one night of sleep deprivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018;115:4483–8. 10.1073/pnas.1721694115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bigler ED. Symptom validity testing, effort, and neuropsychological assessment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2012;18:632–40. 10.1017/S1355617712000252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baddeley A, Emslie H, Nimmo-Smith I. Doors and People: A Test of Visual and Verbal Recall and Recognition. Bury St, Edmunds, UK: Thames Valley Test Company, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baddeley AD, Hitch GJ, Quinlan PT, et al. . Doors for memory: A searchable database. Q J Exp Psychol 2016;69:2111–8. 10.1080/17470218.2015.1087582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frings L, Hellwig S, Bormann T, et al. . Amyloid load but not regional glucose metabolism predicts conversion to Alzheimer’s dementia in a memory clinic population. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2018;45:1442–8. 10.1007/s00259-018-3983-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cecchin D, Barthel H, Poggiali D, et al. . A new integrated dual time-point amyloid PET/MRI data analysis method. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2017;44:2060–72. 10.1007/s00259-017-3750-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Battle MR, Pillay LC, Lowe VJ, et al. . Centiloid scaling for quantification of brain amyloid with [18F]flutemetamol using multiple processing methods. EJNMMI Res 2018;8:107 10.1186/s13550-018-0456-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nir Y, Staba RJ, Andrillon T, et al. . Regional slow waves and spindles in human sleep. Neuron 2011;70:153–69. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kang D, Lim HK, Jung WS, et al. . Sleep and alzheimer’s disease. Sleep Med Res 2015;6:1–9. 10.17241/smr.2015.6.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. de Heus RAA, de Jong DLK, Sanders ML, et al. . Dynamic regulation of cerebral blood flow in patients with alzheimer disease. Hypertension 2018;72:139–50. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.10900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.