Abstract

Introduction

There is an increasing demand for multi-organ donors for organ transplantation programmes. This study protocol describes the Donation Network to Optimise Organ Recovery Study, a planned cluster randomised controlled trial that aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the implementation of an evidence-based, goal-directed checklist for brain-dead potential organ donor management in intensive care units (ICUs) in reducing the loss of potential donors due to cardiac arrest.

Methods and analysis

The study will include ICUs of at least 60 Brazilian sites with an average of ≥10 annual notifications of valid potential organ donors. Hospitals will be randomly assigned (with a 1:1 allocation ratio) to the intervention group, which will involve the implementation of an evidence-based, goal-directed checklist for potential organ donor maintenance, or the control group, which will maintain the usual care practices of the ICU. Team members from all participating ICUs will receive training on how to conduct family interviews for organ donation. The primary outcome will be loss of potential donors due to cardiac arrest. Secondary outcomes will include the number of actual organ donors and the number of organs recovered per actual donor.

Ethics and dissemination

The institutional review board (IRB) of the coordinating centre and of each participating site individually approved the study. We requested a waiver of informed consent for the IRB of each site. Study results will be disseminated to the general medical community through publications in peer-reviewed medical journals.

Trial registration number

NCT03179020; Pre-results.

Keywords: brain death, cardiac arrest, organ donation, checklist, quality improvement

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first randomised trial to evaluate whether a goal-directed checklist for the management of brain-dead potential organ donors may be useful in reducing cardiac arrests and contributing to increase organ availability for transplants.

The preparation of the goal-directed checklist was preceded by the review of a clinical practice guideline following the Grades of Recommendation Assessment, Development and Evaluation system.

Brazil is a country with a wide spectrum of demographic and socioeconomic scenarios; the diversity of institutions to be included in Donation Network to Optimise Organ Recovery Study will allow us to provide results in a broad range of demographic and socioeconomic scenarios.

Main study limitations are the unblinded design and the high heterogeneity of care and outcomes expected among centres in the study.

Introduction

Organ transplantation is the only treatment option for many patients affected by end-stage organ failure. Despite advances in the field of organ donation, the disparity between the number of patients on transplant waiting lists and the availability of organs for transplantation is increasing. Several parameters determine the availability of suitable organs for donation, and many of these depend on a successful sequence of actions by several healthcare professionals, starting with the identification of a potential multi-organ donor and ending with surgical organ procurement.1–5 In this process, important factors contributing to the gap between organ supply and demand include failure to identify and report brain death, lack of family consent for organ donation, inaccurate perceptions of contraindications to organ donation and haemodynamic instability that may compromise the quality of organs or even lead to loss of donors due to cardiac arrest.1–3 A systematic application of clinical management strategies aimed at the haemodynamic stabilisation of brain-dead donors may contribute to an increase in the number of organs for transplantation by improving the quality of organs and reducing the loss of potential donors due to cardiac arrest.1 2 4 In addition, other measures such as optimal ventilatory support and temperature control may improve the quality of organs, resulting in a higher organ recovery rate and better clinical outcomes for transplant recipients.6 7

Checklists have an established role in healthcare to prevent omissions while performing complex procedures. A series of studies have shown that the use of a goal-directed checklist may help the systematic application of clinical guidelines, leading to greater adherence to evidence-based clinical interventions and improving clinical outcomes. Examples include the World Health Organization (WHO) surgical safety checklist, the Keystone intensive care unit (ICU) project checklist to prevent catheter-related bloodstream infection and clinical checklists to ensure patient safety in the ICU.8–11

There is a lack of evidence for the use of checklists regarding the clinical aspects of improving organ availability for transplantation of brain-dead donors. Some observational studies have reported that the application of a goal-directed checklist to guide the management of brain-dead potential organ donors may reduce the rate of cardiac arrest and increase the number of organs recovered per donor.12–19 However, given the relatively small number of studies, their observational design and inconsistency of findings, often related with barriers to carrying out studies in this scenario,5 this literature cannot yet support the use of a goal-directed checklist in the current management of brain-dead potential organ donors.20

Our hypothesis is that supporting the management of potential organ donors with the use of an evidence-based bedside checklist may reduce the loss of potential organ donors due to cardiac arrest and increase the number of donors and organs recovered per donor. In this protocol, we describe the methods to be used in the Donation Network to Optimise Organ Recovery Study (DONORS).

Objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective is to evaluate the effectiveness of the implementation of an evidence-based bedside checklist, containing goals and recommendations of care as guidance for the management of brain-dead potential organ donors, in reducing potential organ donor losses due to cardiac arrest.

Secondary objectives

Secondary objectives are to assess whether the evidence-based, goal-directed checklist is effective in (a) increasing the number of actual organ donors and (b) increasing the number of organs recovered per actual donor.

Methods and analysis

The protocol is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03179020) and the present manuscript provides additional details regarding study design and methodology. The items from the WHO trial registration data set are described in the online supplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2018-028570supp001.pdf (37.3KB, pdf)

Study design

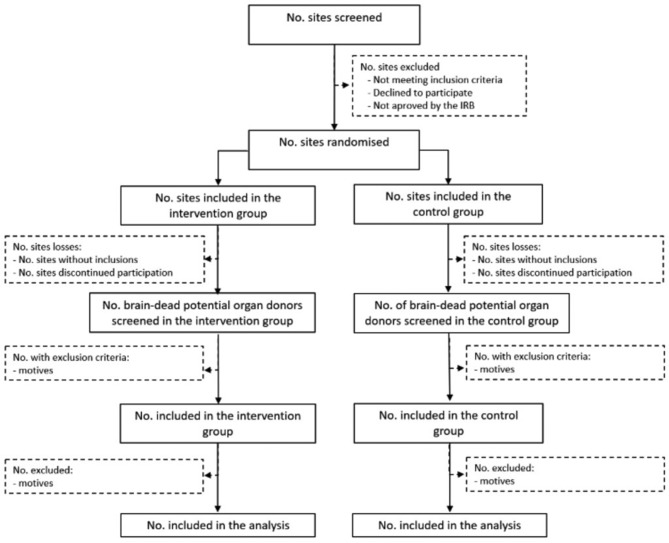

DONORS is a parallel cluster randomised controlled trial involving ICUs of Brazilian hospitals. We will randomly assign hospitals to the intervention group, comprising the checklist implementation, or the control group, consisting of usual care in each ICU (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. IRB, Institutional Review Board; No., number.

Participants

Cluster eligibility, recruitment and exclusion criteria

We will invite adult ICUs with an average of at least 10 annual notifications of potential organ donors in the prior 2 years. Information regarding notifications is provided by the Brazilian National Transplantation System.

Coronary care units, intermediate care units and emergency departments will not be included. We will also exclude institutions that already systematically use checklists as guidance for the management of potential organ donors supported by implementation tools, such as guidelines and clinical decision algorithms for bedside use, in print or digital form.

Patient eligibility and exclusion criteria

We will screen and include consecutive brain-dead potential organ donors, as confirmed by the first clinical examination consistent with having brain death, within the age range of 14 to 90 years. Only ICU patients will be included; potential donors outside the ICU will be included in the study if admitted to ICU within 3 hours of initial assessment.

Diagnosis of brain death will be made according to the Brazilian Federal Board of Medicine guidance, consisting of: two clinical examinations performed by two different physicians, in an interval of at least 1 hour between the examinations, and one apnoea test followed by neuro-imaging (transcranial Doppler, cerebral arteriography, electroencephalography or brain scintigraphy).21 22 We will exclude brain-dead patients who are not candidates for organ donation (online supplementary file 2).

bmjopen-2018-028570supp002.pdf (46.7KB, pdf)

Interventions

Checklist for brain-dead potential organ donors management

After a preliminary prospective study13 that found a positive impact of a clinical goal-directed protocol on reducing irreversible cardiac arrests in brain-dead potential organ donors, an updated checklist was generated after drawing up a clinical practice guideline (CPG) for brain-dead potential organ donor management. The CPG recommendations were developed from July 2016 to March 2017, as a joint initiative of the Brazilian Ministry of Health, Brazilian Association of Intensive Care Medicine (AMIB), Brazilian Association of Organ Transplantation (ABTO)23, and Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network (BRICNet). The recommendations were developed using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation system.24 The following criteria were considered in the decision-making process: the risks and benefits of interventions, the quality of evidence for risks and benefits, resource use and costs and acceptability by healthcare professionals.

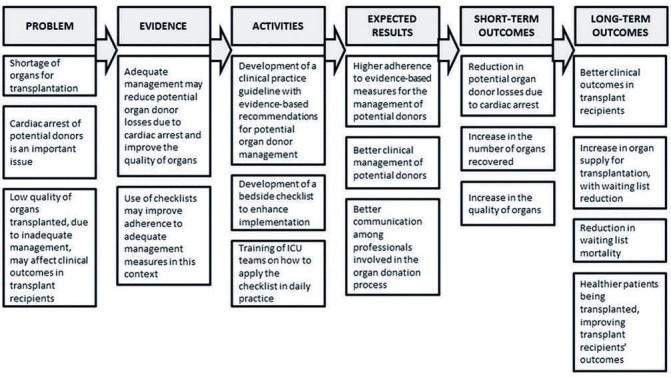

The checklist was designed to address CPG goals and recommendations that involve temperature control, mechanical ventilation, haemodynamic control, endocrine and metabolic control and use of antibiotics and blood products, as required, and hormone administration (hydrocortisone, vasopressin and/or desmopressin, insulin). Thyroid hormone was not recommended due to lack of evidence to confirm the benefit of its use.25 26 We tested the checklist in four ICUs with high volume in brain death notifications that participated in the preliminary study13 and make minimal adjustments suggested by the professionals that tested the tool. The full checklist is available in online supplementary file 3. Figure 2 describes the logical model for the intervention to be tested in this study. We will provide on-site training in each ICU for healthcare professionals to inform how to implement the checklist and how to apply the intended recommendations.

Figure 2.

Logical model for the checklist intervention. ICU, intensive care unit.

bmjopen-2018-028570supp003.pdf (93.5KB, pdf)

The checklist will be bedside applied immediately after the time of potential donor inclusion in the study and repeated every 6 hours until organ recovery or loss of the potential donor. A member of the intrahospital transplant coordination (IHTC) or a designated ICU professional will apply the paper-based checklist at the bedside. The same individual will be responsible for personally prompting the medical team to modify medical management if any inappropriate aspect of care is noted.

Usual care

ICUs in the control group will continue with their usual management of potential organ donors. They will not be informed of the items assessed in the goal-directed checklist or the strategies to enhance compliance.

Co-interventions

All ICU teams and IHTC members of the participating institutions will receive training in family interviews for organ donation. The training and interview process have been based primarily on the Spanish model of communication in critical situations (online supplementary file 4).27–31 Training consists of two components: (1) face-to-face training of one ICU team representative and one IHTC member of each institution and (2) provision of an online, self-instructional course for all ICU team members and IHTC members participating in the study. These co-interventions aim to standardise ICU strategies in relation to family interviews, reducing variability between participating sites. This is important for the trial due to three main reasons: (a) inadequate interviews may result in a lower rate of effective donation (secondary outcomes of the study), independently of potential donor management; (b) reducing variability between participating sites may have an impact on reducing the intracluster correlation of the study, increasing its power and (c) training strategies might enhance the engagement of the participating sites, especially those in the control group, thereby balancing a potential Hawthorne effect. Table 1 shows the strategies to promote effective implementation of intervention and co-intervention.

Table 1.

Strategies to maximise adherence to study interventions and co-interventions

| Strategies | |

| 1. | In-person training of two representatives (study coordinators) from each participating site on the conduct of family interviews. |

| 2. | Provision of an online course for the training of all ICU team members and IHTC members on how to prepare for and conduct a family interview. A family interview support guide will also be made available. |

| 3. | On-site training of ICU team members and IHTC members of all hospitals in the intervention group. The training aims to provide guidance on the methods for administration of the goal-directed checklist for the management of potential organ donors to as many ICU and IHTC professionals as possible. |

| 4. | Monthly reports with the number of potential donors screened and included will be sent by electronic message, in the form of a newsletter, to all members of the health team comprising of professionals from the ICU and IHTC. |

| 5. | The local co-ordinators of the participating sites will be contacted by the study central office co-ordinators whenever there is a failure to adhere to the protocol or to complete the patient’s clinical record form. |

| 6. | The local coordinators of the participating sites will receive, whenever a patient is included, electronic messages to remind them of the need to administer the bedside goal-directed checklist and prompt the medical team on management during the stay of potential organ donors in the ICU. |

| 7. | Remote support from the study coordinators and central office will be made available to all local coordinators for any questions related to the study. |

ICU, intensive care unit; IHTC, intrahospital transplant coordination.

bmjopen-2018-028570supp004.pdf (100.3KB, pdf)

Sample size

With 60 ICUs, we will need to include 19 brain-dead potential organ donors per site (1140 potential donors) to detect an absolute reduction of donor losses due to cardiac arrests of 10% (from 28% in the control group to 18% in the intervention group),13 considering an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05, power of 80%, and a two-sided alpha level of 5%. Therefore, considering a possible variation in cluster size and its impact on statistical power, we intend to include a minimum of 60 ICUs with at least 1200 potential organ donors, not allowing more than 30 participants in each cluster.

Randomisation

We will randomly assign ICUs to the intervention group or control group with a 1:1 allocation ratio using blocks of variable sizes (2 and 4) and stratified by the estimated annual number of notifications of brain death in each site (sites with ≤29 and >29). ICUs from the same institution are not considered independent clusters to avoid contamination. We will randomise the ICUs consecutively as per the date of authorisation of the principal investigator to implement the study in the institution, obtained after the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. To ensure allocation concealment, a statistician from the study coordinating office will be responsible for the randomisation process, with all researchers involved in the trial blinded to the allocation sequence.

Outcomes

The primary outcome will be the number of brain-dead potential organ donor losses due to cardiac arrest, defined as any loss of brain-dead potential organ donors from irreversible or unreversed cardiac arrest that occurs after patient enrolment, while the subject remains eligible for organ donation (no contraindications, family approval or waiting family decision for donation). Losses of potential donors due to other factors (eg, family refusal or contraindication to organ donation after patient inclusion) will not be considered for this outcome.

The secondary outcomes will be:

Number of actual organ donors, indexed to brain-dead potential donors, defined as donors for whom the surgical procedure for organ recovery has been initiated (irrespective of organ recovery)3;

Number of solid organs recovered per actual donor (ranging from zero to seven organs per donor, as follows: liver, heart, pancreas, two lungs and two kidneys).

The tertiary outcomes will include:

The proportion of potential donors with adequate respiratory parameters (defined as arterial PaO2 of oxygen/fraction of inspired oxygen ratio ≥200);

The proportion of potential donors with adequate body temperature (defined as body temperature between 34°C and 35°C if haemodynamically stable and >35°C if mean arterial pressure (MAP) <65 mm Hg or use of norepinephrine or dopamine);

The proportion of potential donors with adequate circulatory parameters (inadequate parameters defined as MAP <65 mm Hg or dose of norepinephrine ≥0.1 mc/kg/min or dose of dopamine ≥15 mcg/kg/min);

Organ dysfunction score, assessed by the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score.

Blinding

Due to the nature of the intervention, it will not be possible to blind investigators or healthcare providers in this study. However, we will not disclose details of the content of the checklist to the control group.

Data collection

An ICU healthcare professional or an IHTC member will collect the data, which will be recorded at the patient’s bedside using a printed case report form and subsequently transferred into an electronic data capture system (REDCap, Vanderbilt University, Tennessee, USA).32 Investigators will receive training for these activities during the study initiation meeting.

Data monitoring

The study statistician will be responsible for reviewing weekly data on all inclusions, checking data consistency and checking whether all forms have been completed correctly. Clinical research monitors will review all data collected and may require supplementation or correction of inconsistent data according to the Good Clinical Practices (GCP) recommended by the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH).33 On-site monitoring visits will take place after the fifth patient inclusion in the site and when 100% of the projected number of inclusions for the site has been achieved. Additional monitoring visits will be performed as needed, based on the detection of data inconsistencies, errors in completing the forms or suspected fraud. Periodic remote follow-up will be performed via telephone or electronic messages with the participating sites according to patient recruitment. The data to be collected from each subject are summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Data to be entered in the clinical record form of all potential organ donors included in the study

| 1. | Identification of the potential donor: research centre code and patient’s hospital registration number, sex and date of birth. |

| 2. | Screening: inclusion and exclusion criteria for definition of eligibility. |

| 3. | History: date and time of hospital admission, date and time of ICU admission, reported and estimated weight, height, SAPS 3 on ICU admission, comorbidities prior to hospitalisation, cause of brain death, date and time of first clinical examination for the diagnosis of brain death. |

| 4. | Respiratory variables: tidal volume, mL; respiratory rate, mpm; PEEP, cm H2O; plateau pressure, cm H2O; peak pressure, cm H2O (if volume is controlled); FiO2, % Blood gas variables: PaO2, mm Hg; SaO2, %; PaCO2, mm Hg; base excess, mmol/dL; PcvO2, mm Hg; ScvO2, %; PcvCO2, mm Hg; lactate, mmol/dL. |

| 5. | Temperature and haemodynamic variables: temperature, °C; heart rate, bpm; systolic blood pressure, mm Hg; diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg; CVP, mm Hg and/or ΔPp, % and/or ΔSV, % and/or IVCCI, %; cardiac arrhythmias. |

| 6. | Diuresis and fluid balance: infused volume; diuresis and fluid balance at different time intervals. |

| 7. | Laboratory variables: haemoglobin, g/dL; creatinine, mg/dL; platelets, /mm3; bilirubin, mg/dL; sodium, mEq/L; potassium, mEq/L; magnesium, mEq/L; phosphorus, mEq/L; calcium, mEq/L. |

| 8. | Drug use: norepinephrine, dopamine, vasopressin, desmopressin, corticosteroids, antibiotics. |

| 9. | Family interview: time, place and name of the professional communicating the establishment of a brain death protocol to the family; time, place and name of the professional communicating the death to the family; time, place and name of the professional conducting the family interview with the request for organ donation; experience and qualification of the professional conducting the family interview with the request for organ donation; family authorisation for organ donation; loss of potential donor due to family refusal; causes of family refusal. |

| 10. | Protocol completion: date and time of second clinical examination for the diagnosis of brain death; date and time of a complementary test for the diagnosis of brain death; complementary test performed for the diagnosis of brain death. |

| 11. | Occurrence of cardiac arrest, loss of potential donor due to cardiac arrest, completion of organ harvesting, number and type of organs recovered. |

CVP, central venous pressure; FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; ICU, intensive care unit; IVCCI, Inferior Vena Cava Collapsibility Index; PaCO2, arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2, arterial partial pressure of oxygen; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; PcvCO2, central venous partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PcvO2, central venous partial pressure of oxygen; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation; SAPS 3, Simplified Acute Physiology Score 3; ScvO2, venous oxygen saturation; ΔPp, pulse pressure respiratory variation; ΔSV, stroke volume respiratory variation.

Statistical analysis

We will prepare a detailed statistical analysis plan before data analysis, which is intended to be published or made available online. We will perform the statistical analysis following the intention-to-treat principle, accounting for cluster design, with observations of the ICUs analysed according to the group to which they have been allocated. We will examine the normality of data by visual inspection of histograms and using the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality. Baseline characteristics of both the ICUs and potential organ donors will be presented as frequencies and percentages, means and SD and medians and IQR, whenever appropriate, for the intervention group and control group.

For the primary outcome, we will calculate HRs considering the time to the outcome, since patients will be subjected to management at different time intervals in the institutions. Patients will be considered at risk for the occurrence of the outcome of interest while under consideration as potential donors. If the outcome of interest does not occur, patients’ follow-up will be considered to have ended at the time their management has been discontinued (family refusal or contraindication to donation). We will conduct predefined subgroup analyses, considering the following variables: age >60 years, cause of the injury leading to potential brain death (traumatic or non-traumatic) and patient severity on ICU admission defined by the Simplified Acute Physiology Score 3 (SAPS 3) with a cut-off determined by its median. We will conduct sensitivity analyses of adherence to the intervention (compliance with checklist proposed measures) and of the time interval between the first clinical examination consistent with having brain death and inclusion in the study.

For secondary and tertiary outcomes, we will use models for correlated data, considering the ICU as a cluster and each outcome with its own probability distribution. We will conduct a sensitivity analysis of the outcome ‘number of solid organs recovered per actual donor’, considering the number of kidneys harvested. We will analyse secondary outcomes by adjusting for multiple hypothesis testing. For all statistical comparisons, we will adopt a statistical significance level of 0.05. An up-to-date version of the R programme (R Development Core Team) will be used to conduct analyses.

Study planning and implementation schedule

We finalised the study design and protocol in March 2016. The National Study Investigators Meetings were held in two parts: 9 to 10 March 2017 and 8 to 9 June 2017. At the time of manuscript preparation, 63 ICUs representative of the Brazilian geopolitical territory are currently recruiting study subjects (figure 3). On-site training started on 1 June, 2017. We expect that the recruitment will be completed in December 2019. The list of sites included is available at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03179020).

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of the participating intensive care units in Brazil. (map base copyright obtained from www.gettyimages.pt).

Organisational aspects of the study

The study is sponsored and co-ordinated by the Moinhos de Vento Hospital, Brazil, in partnership with the Brazilian Ministry of Health through the Programme of Institutional Development of the Brazilian Unified Health System and in association with the General Co-ordination Office of the National Transplant System and the Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network. The study is supported by the AMIB Committee for Organ Donation for Transplant, ABTO, the Spanish National Transplant Organisation and the organ procurement organisations of the states of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul. The study steering committee consists of intensivists, transplant coordinators and epidemiologists with expertise in conducting multi-centre studies. The committee is involved in the conception and design of the study, supervision of progress and procedures during the study and writing of the study report and any resulting study manuscript.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was designed in accordance with resolution No. 466/2012 of the Brazilian National Health Council/Ministry of Health, the Declaration of Helsinki, the Document of the Americas and the ICH/GCP E6(R2) 2016.33 The study was approved by the IRB of the coordinating centre (No. 53999616.0.1001.5330) and by the IRB of each participating site (online supplementary file 5). Participating in the intervention or control groups does not imply any risk for the subjects included, since the groups will not be deprived of the application of the most up-to-date recommendations. Because obtaining written informed consent from patients’ family members entails operational and methodological difficulties, and would have a potential negative impact on organ donation as well, we requested a waiver of informed consent for the IRB of each participating site.

bmjopen-2018-028570supp005.pdf (99KB, pdf)

This trial, regardless of the results, will be published in a peer-reviewed medical journal and presented in scientific conferences and scientific meetings involving the representatives of each participating hospital, of each Brazilian state transplant centre and of the Brazilian Ministry of Health.

Patient and public involvement

Considering the characteristics of the study population, the patients were not directly involved in the research question, study design, study participants recruitment and study conduction.

Discussion

Despite the existence of CPGs that currently provide recommendations for a ‘standard of care’ in the management of potential organ donors,23 29 they are not always implemented, resulting in the risk of loss of specific organs due to management failures or even multiple organ loss due to cardiac arrest of the potential donor.1–4 23 34 CPGs usually do not have an impact on bedside practice in the short-term, as they rarely take into account clinical applicability.35 Therefore, a CPG-based goal-directed checklist associated with a clinician prompting system may be an effective approach to improve physician adherence to CPG recommendations. Physician-centred healthcare can be associated with non-adherence to basic recommendations of care, especially in highly complex processes, such as the management of potential organ donors.34 In this context, we expect that these organisational adjustments, supported by a checklist-based management strategy, will have a positive impact on organ donation.

Patel et al 19 published the results of 671 multi-organ donors managed using a goal-directed checklist in the USA. The predetermined goals were met in 45% of cases prior to organ recovery, and the use of the goal-directed checklist significantly increased the number of organs transplanted per donor.19 Recently, we published a prospective observational study that involved 27 ICUs in a southern Brazilian state demonstrating that the use of a goal-directed checklist to guide the management of deceased donors reduces brain-dead potential organ donor losses due to cardiac arrest.13Compliance with the checklist increased after the start of the study from 52.1% to 85.8% (p<0.001). The use of the checklist was associated with a lower likelihood of occurrence of cardiac arrest (OR: 0.30, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.49, p<0.001) and an increase in the number of organs recovered per donor.13 Although these results are encouraging and reproduce the observations of other authors, the observational nature of the studies provides only weak evidence on the subject.14–19

The study design and basis for the implementation of DONORS may provide new insights that can help overcome the weaknesses of previous observational studies, often related with barriers to conduct studies in deceased organ donors.5 The cluster randomisation design will limit selection biases, and we will count on a large number of ICUs, which are responsible for a significant amount of brain death notifications throughout Brazil. The DONORS design will include the evaluation of the effectiveness of a goal-directed checklist strategy in different socioeconomic scenarios in Brazil, allowing us to provide real-world evidence to support the practical clinical applicability of the study findings. In addition, the trial is testing the effectiveness of the proposed intervention by means of an implementation strategy that may be considered feasible to replicate in different settings. Finally, the characteristics of the institutional quality improvement programme of this protocol will allow the potential benefits generated by the proposed study model to be incorporated into ICUs and ultimately transferred to other clinical areas for the care of critically ill patients.

The implementation of a goal-directed checklist for the management of potential donors is a complex intervention, with multiple components. It is important to state that, as in most quality improvement studies, how the intervention is implemented is crucial to the interpretation of the results. In this respect, through this protocol, we aimed to describe in detail all the interventions and co-interventions proposed in the study in order to allow reproducibility of our procedures in other settings. In addition, the logical model presented in the study (figure 2) is intended to explore the relationships between the activities proposed in the intervention and the mediators of the effect, such as improved clinical management of potential donors and enhanced communication with the ICU team about the expected outcomes. Also important is that, although the study focuses on assessing short-term outcomes in potential donors (eg, cardiac arrest and number of organs recovered), potential beneficial outcomes are expected for transplant recipients, such as improved graft function, survival and quality of life.

Our study has some limitations. First, high variability in care and outcomes among institutions is expected. Although the chosen ICC may be considered conservative, there are no estimates in the literature for the proposed intervention, which may result in lack of power if the actual ICC is larger than the estimate. In spite of the procedures to avoid the transfer of information about the checklist to ICUs in the control group, although with low probability this possibility should be considered, thereby exposing the details of the content of the goal-directed checklist for the control group. Furthermore, although stratified randomisation is planned for this study, we must take into consideration the differences in the number of brain death notifications among ICUs, which will recruit patients at different rates, which in turn may generate learning curves that may have an impact on the final cluster randomisation trial results. In order to minimise this problem, we are allowing a maximum of 30 patients to be recruited per each study site; however, some ICUs may recruit a small number of patients. Inadequate adherence to the checklist may have an impact on the results observed in the intervention group, showing no effect that may be either due to lack of efficacy of the intervention or due to its suboptimal implementation. Another important aspect to highlight is that, although we expect to see an improvement in the quality of organs with the use of the checklist, therefore improving outcomes for organ-transplant recipients, we are limiting the data collection and study procedures to potential donors, not allowing direct assumptions about its possible effects. Finally, a possible variability in the care of patients with catastrophic brain injury (CBI), before its evolution to brain death, may occur among the study sites. On the other hand, the results may contribute as an indirect evidence for the management of patients who have a CBI.

Conclusions

We expect that the results from DONORS will provide information regarding the practical use of checklist-guided management interventions for potential multi-organ donors that may contribute to reducing potential donor losses due to cardiac arrest or other relevant outcomes. At this time, with the increasing demand for organs for transplantation, standardised, evidence-based guidelines that may be adopted globally by ICUs and by transplant coordinators are needed to improve the availability and quality of organs available for donation. The evidence generated by this trial will have great potential to contribute positively to the donation of organs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the data collection team of each participating ICU, as well as the Moinhos de Vento Hospital (the Coordinating Centre), the Brazilian Ministry of Health, the Brazilian Research in Intensive Care Network (BRICNet), the General Coordination Office of the National Transplant System (CGSNT), the Committee for Organ Donation for Transplant of the Brazilian Association of Intensive Care Medicine (AMIB), the Brazilian Association of Organ Transplantation (ABTO) for their support in conducting the study and the professionals who provided the training in family interviews for organ donation: Aline Ghellere, Charlene Verusa da Silva, Dagoberto Franca da Rocha, Eduardo Jardim Berbigier, Edvaldo Leal de Moraes, Felipe Pfuetzenreiter, Leonardo Borges de Barros e Silva, Luana Cristina Heberle dos Santos, Luana Tannous, Lucia Maria Del Carmen Segovia Gomes, Miriam Machado, Neide da Silva Knihs, and Paulo Ricardo Cardoso.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study design and revised this manuscript: GAW, CCR, ABC, FRM, RGR, CT, JA, CAF, LCPA, FAB, CMG, DBS, DS, DZP, ICM, AIR, SSS, NEG, LVA, PSB, FRR, MFRBM, TBP, CMCG, PCD, JFPO, GCM, FACA, RBM, VN, LSH, MOM, RRN and MF. Additionally, GAW, FRM and ABC conceived the study, RGR, CT, LCPA, FAB, LSH and MF also helped with the study design and GAW drafted the first version of the article. JA, CAF and RRN, helped with centre recruitment and with the co-intervention aspects. GAW, JA, CMG and DBS coordinated educational actions for the intervention. NEG, DS, MF, RGR, CCR and ABC planned epidemiological and statistical aspects of the study; CMG, ICM and DZP designed the study manuals and study tools; ICM and CMG led site management; ICM, LAV, CMG, AIR and SSS visited all sites to provide training and CCR, ICM, CMG, PSB and DZP organised the study meetings. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Health through the Programme of Institutional Development of the Brazilian Unified Health System (PROADI-SUS).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: DONORS (Donation Network to Optimise Organ Recovery Study) Investigators and the BRICNet: Jose Luis Toribio Cuadra, Caroline Luciane de Oliveira, Gabriela Rech and Bruna dos Passos Gimenes. Hospital de Urgência e Emergência de Rio Branco (AC): Iris de Lima Ferraz Siqueira, Aldo Damian Chambi Garrido, Gigliane Maria Angelim de Albuquerque, and Régis Augusto Hashimoto. Hospital das Clínicas de Rio Branco (AC): Mateus Roza Teles, Rosely Barreiros Cruz, and Nelson Antônio Carneiro Pinheiro Júnior. Hospital Geral Prof. Osvaldo Brandão Vilela (AL): Janaína Maria Miranda Ferreira de Moraes, Claudete Maria Balzan, Lúcia Regina Arana Leite, and Lis Daniela Pinto Oliveira. Hospital de Pronto Socorro João Paulo II (RO):Edwin Fanola Novillo, Maxwendell Gomes Batista, and Silvecler Cortijo de Campos. Hospital de Pronto Socorro Dr. João Lúcio Pereira Machado (AM): Marcelo Souza Ferreira, Helen Figueiredo, Nathalia Cristina Moraes, and Paulo Henrique Lira Matos. Hospital de Urgência de Sergipe (SE): Janaína Feijó, Dernivania de Andrade Ferreira, Ana Paula Rocha Barrel Machado, and Poliana Nunes Santos. Hospital Geral Cleriston Andrade (BA): Lúcio Couto de Oliveira Júnior, Felipe Ferreira Ribeiro de Souza, Daniela Cunha de Oliveira, and Graças de Maria Dias Reis. Hospital Instituto Dr. José Frota (CE): Ana Virgínia Rolim, Lisiane Paiva Alencar, Samira Rocha Magalhães, and Eliana Regia Barbosa de Almeida. Hospital Geral de Fortaleza (CE): Joel Isidoro Costa, Larissa Salles Pontes Carneiro, and Márcia Maria Vitorino Sampaio Passos. Hospital Regional do Cariri (CE): Gustavo Martins dos Santos, José Wagner Brito de Souza, and Bruna Bandeira Oliveira Marinho. Irmandade Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Sobral (CE): Luiz Derwal Salles Júnior, José Henrique Gurgel, Iranildo Passos Fontenele, and Layanny Teles Linhares Bezerra. Hospital Regional Norte (CE): Francisco Olon Leite Júnior, Israel Ferreira da Costa, Diego Bruno Santos Pinheiro, and Denise Martins de Moura. Hospital Regional Tarcísio de Vasconcelos Maia (RN): Fernando Albuerne Bezerra, Suzana Cantidio, Jéssica Patrícia Saraiva Medeiros Lima Moreira, and Bruna de Sousa Carvalho. Hospital Alberto Urquiza Wanderley (PB): Ciro Leite Mendes, Igor Mendonça do Nascimento, and Juliana Sousa Dias. Hospital Municipal Djalma Marques (MA): Alexandre Augusto Gomes Alves, Heloisa Rosário Furtado Oliveira Lima, Silvia Helena Cardoso de Araújo Carvalho, and Clayton Aragão Magalhães. Hospital Dr. Carlos Macieira (MA): Marko Antônio Santos, Luiza Maria de Novoa Moraes, Lea Barroso Coutinho Pereira, and Henrique Lott Carvalho Novaes Sobrinho. Hospital da Restauração (PE): Sylvia Helena Araújo Lima Siqueira, and Janaína Rodrigues da Silva. Hospital de Ensino Doutor Washington Antônio de Barros (PE): Samyra Pereira de Moraes, Janaína Correia Walfredo Carvalho, and Kátia Regina de Oliveira. Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (DF): Luiz Hamilton da Silva, Viviane Marçal da Silva, and Camila Vieira Hirata. Hospital Estadual de Urgência e Emergência de Vitória (ES): Jander Pissinate Fornaciari, Ana Paula Neves Curty, Ivens Guimarães Soares, and Leandro de Oliveira Ferreira. Hospital de Urgência de Goiânia (GO): Alexandre Amaral, Guilherme Ono de Gouvêa, and Ana Paula Cordeiro de Menezes Silveira. Hospital João XXIII (MG): Frederico Bruzzi de Carvalho, Natasha Preis Ferreira, Sylmara Jenifer Zandona Freitas, Fernanda Coura Pena de Sousa, and Chen Laura. Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (MG): Christiane de Freitas Morrão Helt Mantuano Pereira, and Amélia Cristina Gomes. Hospital Universitário Ciências Médicas (MG): Jeova Ferreira de Oliveira, Marcela Leandro Baldow, and Rodrigo Santana Dutra. Irmandade Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Belo Horizonte (MG): Mara Rubia de Moura, Claudio Dornas de Oliveira, Andressa Siuves Moreira, and Marina Ferreira de Oliveira. Santa Casa de Campo Grande (MS): Patrícia Berg Gonçalves Pereira Leal, Ana Paula Silva das Neves, Rodrigo Correa Gomes da Silva, and Márcia Heloisa Flores. Hospital Municipal Padre Germano Lauck (PR): Roberto de Almeida, Karin Aline Zili Couto, Alexsandro José dos Santos Fernandes, and Carla Fabíola Carvalho. Hospital Evangélico de Londrina (PR): Elizabeth Regina de Jesus Capelo Frois, Ana Luiza Mezaroba, and Josiane Festti. Hospital Universitário Regional dos Campos Gerais (PR): Thomas Markus Dhaese, Simone Macedo Hanke, and Guilherme Arcaro. Hospital Bom Jesus de Ponta Grossa (PR): Maikel Ramthun, Jullye Christine Pereira Tomacheski, César Flores, and Patrícia Bertoncini Cwiertnia. Hospital Universitário de Cascavel do Oeste do Paraná (PR): Péricles Duarte, Elaine Fátima Padilha, Cleber Tchaicka, and Lizandra de Oliveira Ayres. Hospital Universitário Regional do Norte do Paraná (PR): Sheila Esteves Farias, Marcos Toshyiuki Tanita, and Lucienne Tibery Queiroz Cardoso. Hospital Universitário de Maringá (PR): Almir Germano, Catia Milene Dell’Agnolo, and Rosane Almeida de Freitas. Irmandade Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Maringá (PR): Ellen Sotti Barbosa, Vanessa Martim Mezzavila, and Pedro Rigon Junior. Hospital Bom Jesus de Toledo (PR): Itamar Weiwanko, Cristiano Mroginski, and Waldir Antonio Pasa Junior. Hospital Nossa Senhora do Rocio de Campo Largo (PR): Ricardo Gustavo Zill Risson, Fernanda Gabriella Barbosa Santos, and Mayara Ferreira Vieira. Hospital e Maternidade Angelina Caron (PR): Tatiana Euclydes Cassolli, Mariana Pramio Singer, Rosiane de Oliveira Pereira, and Jaciara Ribeiro de Oliveira. Hospital Santa Rita de Maringá (PR): Melina Almeida Slemer Lemos, Vivianne Cristina Boaretto Toniol, and Mariza Aparecida de Souza. Hospital Norte Paranaense (PR): Ângelo Yassushi Hayashi, Priscila Lisane de Lima de Paula, and Elza de Lara Bezerra. Hospital São Vicente de Paulo Guarapuava (PR): Fernanda Grossmann Ziger Borges, Elaine Silva Ramos, Cibele Aparecida Marochi, and Jessyca Braga. Hospital Geral de Nova Iguaçu (RJ): Alexander de Oliveira Sodré, Letícia Alves Pereira Entrago, Thiago Matos Barcelos, and Roberta Carvalho de Jesus. Hospital Estadual Getúlio Vargas (RJ): Vitor Montez, Mônica Silvina França da Silva de Melo, Tais Cristina Benites Vaz, and Vladimir dos Santos. Hospital Bruno Born (RS): Fábio Fernandes Cardoso, Lucas Mallmann, Adriana Calvi, and Nelson Barbosa Franco Neto. Hospital Cristo Redentor (RS): Manoel Nelson de Oliveira Silveira, Deisi Fonseca, and Susana Santini. Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre (RS): Edison Moraes Rodrigues Filho, Fernanda Paiva Bonow, Ruth Susin, and Kellen Patrícia Mayer Machado. Hospital de Pronto Socorro Nelson Marchezan (RS): Danielle Molardi de Aguiar, Caroline Salim Scheneider, Lidiane Couto Braz, and Carlos Francisco Pereira do Bem. Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (RS): Tatiana Helena Rech, and Edison Moraes Rodrigues Filho. Hospital de Pronto Socorro de Porto Alegre (RS): Vivian Wuerges de Aquino, Fernando Bourscheit, Luciano Marini. Hospital Universitário São Francisco de Paula (RS): Bianca Rodrigues Orlando, Luciano de Oliveira Teixeira, Silvia Zluhan Bizarro, and Viviani Aspirot Mendonça. Hospital São Vicente de Paulo (RS): José Oliveira Calvete, Lina Maito, Sabrina Frighetto Henrich, and Larissa Assunta Pellizzaro. Hospital Universitário São Francisco da Providência de Deus de Bragança Paulista (SP): Thiago Corsi Filiponi, Felipe Fernandes Pires Barbosa, and Flávia Gozzoli. Casa de Saúde de Santos (SP): André Scazufka Ribeiro, Paulo Henrique Penha Rosateli, Zeher Mohamad Waked, and Ana Paula Quintal. Hospital de Base de São José do Rio Preto (SP): Suzana Margareth Ajeje Lobo, Regiane Sampaio, Marcos Morais, James da Luz Rol, and Luciana da Silva Ferreira. Hospital das Clínicas de Botucatu (SP): Laercio Martins de Stefano, Marina Acosta Cleto, Silvia Eduara Kenrnely, and Cintia Banin. Hospital Municipal Irmã Dulce (SP): Maria Odila Gomes Douglas, Renato Luis Borba, Daniela Boni, and Eliza Maria Prado Monteiro. Hospital Paulistano (SP): Airton Leonardo de Oliveira Manoel, Ciro Parioto Neto, and Siderleny Casari Martins. Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto (SP): Wilson José Lovato, Marcelo Bonvento, Rodrigo Barbosa Cerantola, and Leonardo Carvalho Palma. Hospital Beneficência Portuguesa de São Paulo (SP): Salomon Ordinola Rojas, Viviane Cordeiro Veiga, Raquel Telles, and Phillipe Travassos. Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo (SP): Roberto Marco, Fabiano Hirata, Cinthia Consolin Vieira, and Ligia Peraza. Hospital São Paulo (SP): Miriam Jackiu, Flávio Geraldo Resende Freitas, and Alessandra Duarte Santiago. Irmandade Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Sorocaba (SP): Márcia Rosangela Bertin, Luiz Otsubo, and Ana Laura Pinatti Marques. Hospital Geral de Taipas (SP): Martha Pereira Torres and Gileade Gomes dos Santos. Hospital Regional do Vale do Paraíba (SP): Márcia Christina Gomes, Caio Lúcio Soubhia Nunes, and Felipe Alves Moreira. Central Estadual de Transplantes (AC): Regiane Clelia Ferrari. Central Estadual de Transplantes (AL): Daniela Barbosa Ramos. Central Estadual de Transplantes (AM): Leny Nascimento Motta Passos. Central Estadual de Transplantes (BA): América Carolina Brandão de Melo Sodré and Rita de Cassia Martins Pinto Pedosa. Central Estadual de Transplantes (CE): Eliana Regia Barbosa de Almeida. Central Estadual de Transplantes (DF): Daniela Ferreira Salomão Pontes. Central Estadual de Transplantes (ES): Raquel Duarte Correa Matiello and Maria dos Santos Machado. Central Estadual de Transplantes (GO): Fernando Castro and Gustavo Prudente Gonçalves. Central Estadual de Transplantes (MA): Maria Ines Gomes de Oliveira. Central Estadual de Transplantes (MG): Omar Lopes Cancado Junior. Central Estadual de Transplantes (MS): Claire Carmen Miozzo. Central Estadual de Transplantes (PB): Gyanna Lys Melo Moreira Montenegro. Central Estadual de Transplantes (PE): Noemy Alencar de Carvalho Gomes. Central Estadual de Transplantes (PR): Arlene Teresinha Cagol Garcia Badoch. Central Estadual de Transplantes (RJ): Rodrigo Alves Sarlo and Gabriel Teixeira e Mello Pereira. Central Estadual de Transplantes (RN): Raissa de Medeiros Marques. Central Estadual de Transplantes (RO): Suely Lima Araújo Toledo. Central Estadual de Transplantes (RS): Cristiano Franke and Ricardo Klein Ruhling. Central Estadual de Transplantes (SE): Benito Oliveira Fernandez. Central Estadual de Transplantes (SP): Agenor Spalini and Marizete Peixoto Medeiros. Sistema Nacional de Transplantes: Brena Pinheiro Coelho and Joselio Emar de Araújo.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Contributor Information

DONORS (Donation Network to Optimise Organ Recovery Study) Investigators and the BRICNet:

Jose Luis Toribio Cuadra, Caroline Luciane De Oliveira, Gabriela Rech, Bruna Dos Passos Gimenes, Iris De Lima Ferraz Siqueira, Aldo Damian Chambi Garrido, Gigliane Maria Angelim de Albuquerque, Régis Augusto Hashimoto, Mateus Roza Teles, Rosely Barreiros Cruz, Nelson Antônio Carneiro Pinheiro Júnior, Janaína Maria Miranda Ferreira de Moraes, Claudete Maria Balzan, Lúcia Regina Arana Leite, Lis Daniela Pinto Oliveira, Edwin Fanola Novillo, Maxwendell Gomes Batista, Silvecler Cortijo De Campos, Marcelo Souza Ferreira, Helen Figueiredo, Nathalia Cristina Moraes, Paulo Henrique Lira Matos, Janaína Feijó, Dernivania De Andrade Ferreira, Ana Paula Rocha Barrel machado, Poliana Nunes Santos, Lúcio Couto De oliveira Júnior, Felipe Ferreira Ribeiro de Souza, Daniela Cunha De Oliveira, Graças De Maria Dias Reis, Ana Virgínia Rolim, Lisiane Paiva Alencar, Samira Rocha Magalhães, Eliana Regia Barbosa de Almeida, Joel Isidoro Costa, Larissa Salles Pontes Carneiro, Márcia Maria Vitorino Sampaio Passos, Gustavo Martins Dos Santos, José Wagner Brito de Souza, Bruna Bandeira Oliveira Marinho, Luiz Derwal Salles Júnior, José Henrique Gurgel, Iranildo Passos Fontenele, Layanny Teles Linhares bezerra, Francisco Olon Leite Júnior, Israel Ferreira Da Costa, Diego Bruno Santos Pinheiro, Denise Martins De Moura, Fernando Albuerne Bezerra, Suzana Cantidio, Jéssica Patrícia Saraiva Medeiros Lima Moreira, Bruna De Sousa Carvalho, Ciro Leite Mendes, Igor Mendonça Do Nascimento, Juliana Sousa Dias, Alexandre Augusto Gomes Alves, Heloisa Rosário Furtado Oliveira Lima, Silvia Helena Cardoso de Araújo Carvalho, Clayton Aragão Magalhães, Marko Antônio Santos, Luiza Maria De Novoa Moraes, Lea Barroso Coutinho Pereira, Henrique Lott Carvalho Novaes Sobrinho, Sylvia Helena Araújo Lima Siqueira, Janaína Rodrigues Da Silva, Samyra Pereira De Moraes, Janaína Correia Walfredo Carvalho, Kátia Regina De Oliveira, Luiz Hamilton Da Silva, Daniela Ferreira Salomão Pontes, Viviane Marçal Da Silva, Camila Vieira Hirata, Jander Pissinate Fornaciari, Ana Paula Neves Curty, Ivens Guimarães Soares, Leandro De Oliveira Ferreira, Alexandre Amaral, Guilherme Ono De Gouvêa, Ana Paula Cordeiro de Menezes Silveira, Frederico Bruzzi De Carvalho, Natasha Preis Ferreira, Sylmara Jenifer Zandona Freitas, Fernanda Coura Pena de Sousa, Laura Chen, Christiane De Freitas Morrão Helt Mantuano Pereira, Amélia Cristina Gomes, Jeova Ferreira De Oliveira, Marcela Leandro Baldow, Rodrigo Santana Dutra, Mara Rubia De Moura, Claudio Dornas De Oliveira, Andressa Siuves Moreira, Marina Ferreira De Oliveira, Patrícia Berg Gonçalves Pereira Leal, Ana Paula Silva das Neves, Rodrigo Correa Gomes da Silva, Márcia Heloisa Flores, Roberto De Almeida, Karin Aline Zili Couto, Alexsandro José Dos Santos Fernandes, Carla Fabíola Carvalho, Elizabeth Regina De Jesus Capelo Frois, Ana Luiza Mezaroba, Josiane Festti, Thomas Markus Dhaese, Simone Macedo Hanke, Guilherme Arcaro, Maikel Ramthun, Jullye Christine Pereira Tomacheski, César Flores, Patrícia Bertoncini Cwiertnia, Péricles Duarte, Elaine Fátima Padilha, Cleber Tchaicka, Lizandra De Oliveira Ayres, Sheila Esteves Farias, Marcos Toshyiuki Tanita, Lucienne Tibery Queiroz Cardoso, Almir Germano, Catia Milene Dell’Agnolo, Rosane Almeida De Freitas, Ellen Sotti Barbosa, Vanessa Martim Mezzavila, Pedro Rigon Junior, Itamar Weiwanko, Cristiano Morginski, Waldir Antonio Pasa Junior, Ricardo Gustavo Zill Risson, Fernanda Gabriella Barbosa santos, Mayara Ferreira Vieira, Tatiana Euclydes Cassolli, Mariana Pramio Singer, Rosiane De Oliveira Pereira, Jaciara Ribeiro De Oliveira, Melina Almeida Slemer Lemos, Vivianne Cristina Boaretto Toniol, Mariza Aparecida De Souza, Ângelo Yassushi Hayashi, Priscila Lisane De lima de Paula, Elza De Lara Bezerra, Fernanda Grossmann Ziger Borges, Elaine Silva Ramos, Cibele Aparecida Marochi, Jessyca Braga, Alexander De Oliveira Sodré, Letícia Alves Pereira Entrago, Thiago Matos Barcelos, Roberta Carvalho De Jesus, Vitor Montez, Mônica Silvina França da Silva de Melo, Tais Cristina Benites vaz, Vladimir Dos Santos, Fábio Fernandes Cardoso, Lucas Mallmann, Adriana Calvi, Nelson Barbosa Franco Neto, Manoel Nelson De Oliveira Silveira, Deisi Fonseca, Susana Santini, Fernanda Paiva Bonow, Ruth Susin, Kellen Patrícia Mayer Machado, Danielle Molardi De Aguiar, Caroline Salim Scheneider, Lidiane Couto Braz, Carlos Francisco Pereira do Bem, Tatiana Helena Rech, Edison Moraes Rodrigues Filho, Vivian Wuerges De Aquino, Fernando Bourscheit, Luciano Marini, Bianca Rodrigues Orlando, Luciano De Oliveira Teixeira, Silvia Zluhan Bizarro, Viviani Aspirot Mendonça, José Oliveira Calvete, Lina Maito, Sabrina Frighetto Henrich, Larissa Assunta Pellizzaro, Thiago Corsi Filiponi, Felipe Fernandes Pires Barbosa, Flávia Gozzoli, André Scazufka Ribeiro, Paulo Henrique Penha Rosateli, Zeher Mohamad Waked, Ana Paula Quintal, Suzana Margareth Ajeje lobo, Regiane Sampaio, Marcos Morais, James Da Luz Rol, Luciana Da Silva Ferreira, Laercio Martins De Stefano, Marina Acosta Cleto, Silvia Eduara Kenrnely, Cintia Banin, Maria Odila Gomes Douglas, Renato Luis Borba, Daniela Boni, Eliza Maria Prado Monteiro, Airton Leonardo De oliveira Manoel, Ciro Parioto Neto, Siderleny Casari Martins, Wilson José Lovato, Marcelo Bonvento, Rodrigo Barbosa Cerantola, Leonardo Carvalho Palma, Salomon Ordinola Rojas, Viviane Cordeiro Veiga, Raquel Telles, Phillipe Travassos, Roberto Marco, Fabiano Hirata, Cinthia Consolin Vieira, Ligia Peraza, Miriam Jackiu, Flávio Geraldo Resende Freitas, Alessandra Duarte Santiago, Márcia Rosangela Bertin, Luiz Otsubo, Ana Laura Pinatti Marques, Martha Pereira Torres, Gileade Gomes Dos Santos, Márcia Christina Gomes, Caio Lúcio Soubhia Nunes, Felipe Alves Moreira, Regiane Clelia Ferrari, Daniela Barbosa Ramos, Leny Nascimento Motta Passos, América Carolina Brandão de Melo Sodré, Rita De Cassia Martins Pinto Pedosa, Eliana Regia Barbosa de Almeida, Raquel Duarte Correa Matiello, Maria Dos Santos Machado, Fernando Castro, Gustavo Prudente Gonçalves, Maria Ines Gomes de Oliveira, Omar Lopes Cancado Junior, Claire Carmen Miozzo, Gyanna Lys Melo Moreira Montenegro, Noemy Alencar De Carvalho Gomes, Arlene Teresinha Cagol Garcia Badoch, Rodrigo Alves Sarlo, Gabriel Teixeira E Mello Pereira, Raissa De Medeiros Marques, Suely Lima Araújo Toledo, Ricardo Klein Ruhling, Benito Oliveira Fernandez, Agenor Spalini, Marizete Peixoto Medeiros, Brena Pinheiro Coelho, and Joselio Emar De Araújo

Collaborators: DONORS (Donation Network to Optimise Organ Recovery Study) Investigators and the BRICNet

References

- 1. The Madrid resolution on organ donation and transplantation: national responsibility in meeting the needs of patients, guided by the WHO principles. Transplantation 2011;91(Suppl 11):S29–31. 10.1097/01.tp.0000399131.74618.a5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tullius SG, Rabb H. Improving the Supply and Quality of Deceased-Donor Organs for Transplantation. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1920–9. 10.1056/NEJMra1507080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Domínguez-Gil B, Delmonico FL, Shaheen FA, et al. . The critical pathway for deceased donation: reportable uniformity in the approach to deceased donation. Transpl Int 2011;24:373–8. 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01243.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. DuBose J, Salim A. Aggressive organ donor management protocol. J Intensive Care Med 2008;23:367–75. 10.1177/0885066608324208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Opportunities for organ donor intervention research: Saving lives by improving the quality and quantity of organs for transplantation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mascia L, Pasero D, Slutsky AS, et al. . Effect of a lung protective strategy for organ donors on eligibility and availability of lungs for transplantation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;304:2620–7. 10.1001/jama.2010.1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Niemann CU, Feiner J, Swain S, et al. . Therapeutic Hypothermia in Deceased Organ Donors and Kidney-Graft Function. N Engl J Med 2015;373:405–14. 10.1056/NEJMoa1501969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. . A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med 2009;360:491–9. 10.1056/NEJMsa0810119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. . An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2725–32. 10.1056/NEJMoa061115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weiss CH, Moazed F, McEvoy CA, et al. . Prompting physicians to address a daily checklist and process of care and clinical outcomes: a single-site study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:680–6. 10.1164/rccm.201101-0037OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cavalcanti AB, Bozza FA, Machado FR, et al. . Effect of a Quality Improvement Intervention With Daily Round Checklists, Goal Setting, and Clinician Prompting on Mortality of Critically Ill Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;315:1480–90. 10.1001/jama.2016.3463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Westphal GA, Zaclikevis VR, Vieira KD, et al. . A managed protocol for treatment of deceased potential donors reduces the incidence of cardiac arrest before organ explant. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 2012;24:334–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Westphal GA, Coll E, de Souza RL, et al. . Positive impact of a clinical goal-directed protocol on reducing cardiac arrests during potential brain-dead donor maintenance. Crit Care 2016;20:323 10.1186/s13054-016-1484-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Helms AK, Torbey MT, Hacein-Bey L, et al. . Standardized protocols increase organ and tissue donation rates in the neurocritical care unit. Neurology 2004;63:1955–7. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000144197.06562.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Franklin GA, Santos AP, Smith JW, et al. . Optimization of donor management goals yields increased organ use. Am Surg 2010;76:587–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Malinoski DJ, Daly MC, Patel MS, et al. . Achieving donor management goals before deceased donor procurement is associated with more organs transplanted per donor. J Trauma 2011;71:990–6. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31822779e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salim A, Velmahos GC, Brown C, et al. . Aggressive organ donor management significantly increases the number of organs available for transplantation. J Trauma 2005;58:991–4. 10.1097/01.TA.0000168708.78049.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malinoski DJ, Patel MS, Daly MC, et al. . The impact of meeting donor management goals on the number of organs transplanted per donor: results from the United Network for Organ Sharing Region 5 prospective donor management goals study. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2773–80. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825b252a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patel MS, Zatarain J, De La Cruz S, et al. . The impact of meeting donor management goals on the number of organs transplanted per expanded criteria donor: a prospective study from the UNOS Region 5 Donor Management Goals Workgroup. JAMA Surg 2014;149:969–75. 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. . SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wijdicks EF, Varelas PN, Gronseth GS, et al. . Evidence-based guideline update: determining brain death in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2010;74:1911–8. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e242a8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brasil. Conselho Federal de Medicina. Resolução CFM 2.173, 15/12/2017. http://www.saude.rs.gov.br/upload/arquivos/carga20171205/19140504-resolucao-do-conselho-federal-de-medicina-2173-2017.pdf (Cited 24 Jul 2018).

- 23. Westphal GA, Caldeira Filho M, Fiorelli A, et al. . Guidelines for maintenance of adult patients with brain death and potential for multiple organ donations: the Task Force of the Brazilian Association of Intensive Medicine the Brazilian Association of Organs Transplantation, and the Transplantation Center of Santa Catarina. Transplant Proc 2012;44:2260–7. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. . GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:383–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Macdonald PS, Aneman A, Bhonagiri D, et al. . A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of thyroid hormone administration to brain dead potential organ donors. Crit Care Med 2012;40:1635–44. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182416ee7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rech TH, Moraes RB, Crispim D, et al. . Management of the brain-dead organ donor: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation 2013;95:966–74. 10.1097/TP.0b013e318283298e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rech TH, Rodrigues Filho EM. [Family approach and consent for organ donation]. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 2007;19:85–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vincent A, Logan L. Consent for organ donation. Br J Anaesth 2012;108(Suppl 1):i80–7. 10.1093/bja/aer353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gobierno de España. Organización Nacional de Trasplantes. Comunicación en situaciones críticas. http://agora.ceem.org.es/wp-content/uploads/documentos/bioetica/comunicacionensituacionescriticasONT.pdf (Cited 24 Jul 2018).

- 30. Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. . A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2007;356:469–78. 10.1056/NEJMoa063446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Shannon SE, et al. . The family conference as a focus to improve communication about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: opportunities for improvement. Crit Care Med 2001;29:N26–33. 10.1097/00003246-200102001-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. International conference on harmonisation of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Guideline for good clinical practice. E6(R1). 2018. https://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E6/E6_R1_Guideline.pdf.

- 34. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. . Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999;282:1458–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shemie SD, Ross H, Pagliarello J, et al. . Organ donor management in Canada: recommendations of the forum on Medical Management to Optimize Donor Organ Potential. CMAJ 2006;174:S13–30. 10.1503/cmaj.045131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028570supp001.pdf (37.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028570supp002.pdf (46.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028570supp003.pdf (93.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028570supp004.pdf (100.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028570supp005.pdf (99KB, pdf)