Abstract

Introduction

S47445 is a novel positive allosteric modulator of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid receptors that may emerge as a favorable candidate for the symptomatic treatment of cognitive and depressive disorders in patients suffering from Alzheimer's disease (AD) of mild to moderate severity and with depressive symptoms.

Methods

For this double-blind, placebo-controlled 24-week phase II trial, 520 outpatients aged between 55 and 85 years, with probable AD at mild to moderate stages (a Mini-Mental State Examination score of 24-15 inclusive) and exhibiting depressive symptoms (Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia [CSDD] ≥ 8) were recruited in twelve countries and randomized to 3 doses of S47445 (5-15-50 mg) or placebo. The primary end point was the change from baseline in the 11-item Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) total score at week 24. Secondary measures included the Disability Assessment for Dementia, Mini-Mental State Examination, ADAS-Cog 13-item, CSDD, Clinical Global Impression of Change (Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study-CGIC), Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), and safety criteria.

Results

Baseline characteristics were comparable between the 4 groups. After 24 weeks, no statistically significant treatment difference was demonstrated between S47445 (5, 15 or 50 mg/d) and placebo on cognition (ADAS-Cog), function (Disability Assessment for Dementia), or depressive symptoms (CSDD). An improvement on neuropsychiatric symptoms assessed by NPI was evidenced at the lower dose 5 mg/d (Δ -2.55, P = .023, post hoc analysis) compared to placebo. CSDD and total NPI scores improved in all groups including placebo. There were no specific and/or unexpected safety signals observed with any of the S47445 doses.

Discussion

S47445 administered for 24 weeks was safe and well tolerated by patients with mild to moderate AD; the compound did not show significant benefits over placebo on cognition, function, or depressive symptoms.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Positive allosteric AMPA modulator, Glutamate, Depressive symptoms, Neuropsychiatric symptoms

1. Introduction

Patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD) present with a progressive cognitive decline leading to functional impact. Besides cognitive deficits, neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) are highly prevalent in patients with AD as up to 90% of patients will experience significant NPS in the course of their disease [1]. Among them, depressive symptoms are present in approximately 50% of patients [2]. They are common in mild to moderate dementia and seem less prevalent in severe dementia, possibly reflecting the difficulty in assessing depressive symptoms at a later stage [3].

Depression in dementia has been associated with a greater decline in cognition, quality of life and disability in daily life activities, earlier institutionalization, and increased risk of mortality [2], [4], [5].

Diagnosis of depression in AD (dAD) is complex due to not only deficits in verbal expression and other cognitive alterations but also other common symptoms such as sleep disturbances and apathy. dAD may differ from other depressive disorders [6] and is diagnosed in the presence of three or more symptoms of major depression, including additional nonsomatic symptoms (irritability, social withdrawal) but without including the difficulty to concentrate [7]. The National Institute of Mental Health dAD criteria identify a greater proportion of patients with AD as depressed than several other established tools [8], [9].

There is an urgent need for treatments for AD patients with NPS, in particular depressive symptoms. Patients are often treated with antidepressants, despite scarce evidence of their efficacy [3], [10], [11], [12], [13]. Antidepressants and/or antipsychotics are often prescribed off label for the management of these symptoms [14], [15].

Most clinical trials evaluating treatments for cognition in AD often excluded patients with depression, limiting data on these patients. Progress in diagnostic criteria allowing inclusion in a clinical trial of the appropriate population is an essential step for testing drugs that may improve such symptoms and consequently quality of life of patients and caregivers [16].

S47445 is a selective positive allosteric modulator of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors (AMPA-PAM) that emerged as a favorable candidate for the treatment of memory deficits, depressive symptoms, and synaptic dysfunction associated with AD. S47445 demonstrated both procognitive and antidepressant-like properties in animal models [17], [18]. Furthermore, S47445 modulates synaptic plasticity by enhancing long-term potentiation, preserving age-dependent loss of synaptic markers, and increasing neurotrophic factor expression in aged rodents [19], [20]. In healthy elderly volunteers, S47445 was safe and well tolerated, enhanced functional connectivity between brain networks involved in cognition (working memory, attention and Default Mode Networks), and increased glutamate concentration in posterior cingulate cortex [21]. Collectively, functional magnetic resonance imaging results and cerebrospinal fluid levels of S47445 showed that the drug crossed the blood–brain barrier.

The objectives of this phase 2 study were (1) to describe baseline characteristics of an AD population at mild to moderate stage with depressive symptoms and (2) to evaluate the safety and efficacy on cognition and activities of daily living (primary and key secondary objectives, respectively), and depression, global impression of change, and neuropsychiatric symptoms of three doses of S47445 administered for 6 months (secondary objectives) vs. placebo.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This was a 6-month, double-blind, randomized, fixed dose, placebo-controlled study, conducted in AD patients enrolled from 75 sites in twelve countries. The study was conducted in compliance with the protocol, good clinical practice, and the applicable regulatory requirements. Eligible patients, their legal representative if applicable, and the informant provided written informed consent before participating in the study.

The study comprised a 3- to 6-week selection period without study treatment followed by a 24-week double-blind treatment period with 4-parallel groups. Eligible patients were randomized to receive S47445 5 mg, 15 mg, 50 mg, or placebo. Treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine was not allowed. Stratification on severity of the disease (mild/moderate) according to the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) total score at inclusion visit was performed. After 24 weeks of treatment, patients had the possibility to participate in an optional extension period of 28 weeks. During this period, patients continued to take their study treatment in coadministration with donepezil. The objective was to evaluate the safety of the combination of both drugs during the second period.

2.2. Patients

Patients were male or female, 55–85 years old, with probable AD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, text revision criteria for Dementia of Alzheimer's Type and depressive symptoms according to National Institute of Mental Health provisional criteria for dAD. Patients were required to have a MMSE score of 15-24 included and a Cornell Scale for Depression of Dementia (CSDD) score of at least 8 at screening and randomization visits. Patients were required to have no significant abnormalities on brain magnetic resonance imaging, electrocardiogram (ECG), physical examination, and laboratory tests; they had never been treated with acetylcholine esterase inhibitors and memantine or had discontinued treatment (for whatever the reason) 8 weeks before inclusion. Patients were not currently treated with an antidepressant or had been treated with an antidepressant at the recommended dose for at least 8 weeks without clinical efficacy. In all cases, the antidepressant treatment was discontinued at least 3 weeks before the randomization visit.

Exclusion criteria included dementia due to any condition other than AD or any condition not associated with AD that may currently or during the course of the study impair cognition or functioning; depressive symptoms due to any other conditions than AD; medical history of major depressive disorder treated with antidepressive drugs or electroconvulsive therapy >3 years before onset of the disease; high suicidal risk; a history of epilepsy or solitary seizure.

2.3. Training

All raters received training and/or qualification for all scales, and a clinical training focused on the study population.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary end point was the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) 11-item total score at week 24, expressed as change from baseline. A key secondary end point was the Disability Assessment for Dementia (DAD) total score, expressed as change from baseline. Secondary efficacy end points at week 24 assessed cognition using MMSE and ADAS-Cog 13-item, depressive symptoms using CSDD, neuropsychiatric symptoms using Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), and global effects using the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study-Clinical Global Impression of Change. The raters who assessed patients using the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study-Clinical Global Impression of Change were blinded for any other patient safety and cognitive assessments.

Safety was evaluated by recording of adverse events, vital signs, laboratory tests, ECGs, physical examination findings, and suicide risk (CSDD, item 16).

All safety measures were performed at each visit and the end of the study or end of treatment in cases of premature withdrawal.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The efficacy analyses were performed in the full analysis set (FAS) (intention-to-treat principle).

In order to meet the primary and key secondary objectives of the study, the superiority of at least one dose of S45447 was assessed in the FAS on the cognitive performance from the 11-item ADAS-Cog total score and on daily living from the DAD total score expressed in terms of change from baseline to week 24 compared to placebo (primary analysis and key secondary analysis, respectively).

In order to take into account the multiplicity of comparisons, a Holm-based gatekeeping procedure with two families of null hypotheses was used [22]. A fixed sequence test procedure per dose was used, meaning that the key secondary null hypothesis for one dose is tested only if the primary null hypothesis associated to the same dose is rejected before.

A mixed-effect model repeated measures analysis using all the postbaseline visits' observations was used for the primary and key secondary analyses, including the fixed effects of treatment, severity of the disease (mild/moderate), visit and treatment-by-visit and severity-by-visit interactions, as well as covariates of baseline and visit-by-baseline interaction. The analyses fitted an unstructured covariance matrix.

For other secondary end points, the difference between the three S45447 doses and placebo was analyzed through inferential statistics using the same model as the primary analysis (without adjustment to control the type I error) or descriptive statistics, on all secondary efficacy endpoints.

For every safety measurement, descriptive statistics were provided by the treatment group in the safety set (all included patients having taken at least one dose of medication).

The sample size was determined considering the primary end point for a difference between at least one S45447 dose and placebo in the FAS, based on a two-sided Student's t-test for independent samples and using the Bonferroni correction in order to maintain the familywise type I error at 5% (bilateral situation). Per treatment group, 125 patients would allow demonstration that at least one S45447 dose is superior to placebo with a power of around 90% if the true difference is 2.8 points with a standard deviation of 6 points.

3. Results

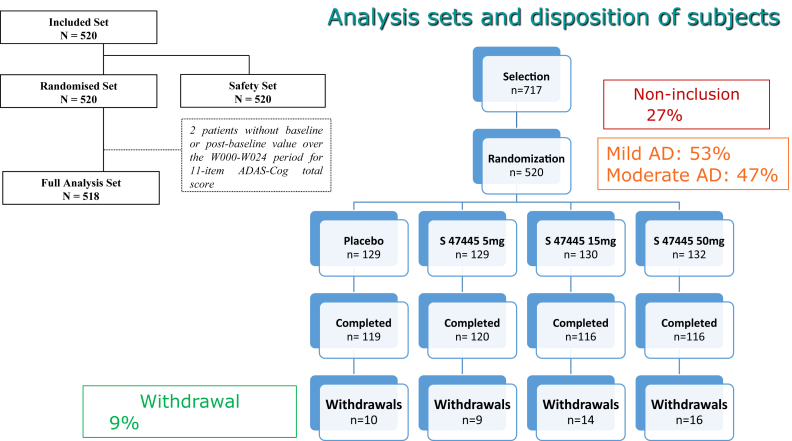

We screened 717 patients, of whom 520 were included and randomized: 129 in the placebo group and 391 in the S47445 groups, 53% were mild (MMSE score ≥ 20) and 47% at a moderate (MMSE score ≤ 19) stage of the disease (Fig. 1). During the 24-week period, 9.4% of the randomized patients were withdrawn from the study (7.75% in placebo, 6.97% in 5 mg, 10.7% in 15 mg, and 12.1% in 50 mg); the main reasons were nonmedical (4.2%) and adverse events (3.8%) without a significant difference between groups.

Fig. 1.

Analysis sets and disposition of subjects. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; ADAS-Cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale.

Baseline characteristics between the four groups were comparable for age, ratio of male/female, education level, AD duration, duration of the current depressive symptoms, and score on scales (Table 1). Patients presented depression with a mean CSDD total score of 11.9 corresponding to a probable major depression and neuropsychiatric symptoms with a mean NPI 12-item total score of 22.4. Most patients had the following NPI items: depression, anxiety, apathy, irritability, sleep, and appetite disorders.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics (FAS)

| All | S47445 5 mg | 15 mg | 50 mg | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients (FAS) | 518 | 129 | 130 | 130 | 129 |

| Age (years) | 71.7 (7.3) | 72.2 (7.3) | 71.7 (7.7) | 71.7 (6.5) | 71.4 (7.7) |

| Male/female (%) | 30.3/69.7 | 36.4/63.6 | 26.1/73.9 | 28.5/71.5 | 30.2/69.8 |

| ApoE4 carriers (%) | 47.2 | 56.6 | 38.2 | 47.2 | 46.9 |

| School education (years) | 11.1 (3.3) | 11.2 (3.4) | 10.9 (3.3) | 11.2 (3.4) | 11.0 (3.3) |

| Disease duration of AD (years) | 3.6 (2.2) | 3.4 (1.7) | 3.8 (2.3) | 3.7 (2.4) | 3.6 (2.2) |

| Duration of the current depressive symptoms (years) | 1.3 (2.0) | 1.1 (1.0) | 1.3 (1.7) | 1.6 (2.8) | 1.3 (2.1) |

| MMSE | 19.7 ± 2.8 | 19.7 ± 2.9 | 19.7 ± 2.7 | 19.6 ± 2.8 | 19.7 ± 2.8 |

| ADAS-Cog 11-item | 23.56 ± 8.98 | 23.76 ± 9.50 | 23.00 ± 8.72 | 24.22 ± 8.88 | 23.26 ± 8.84 |

| ADAS-Cog 13-item | 34.86 ± 10.68 | 35.21 ± 11.09 | 34.25 ± 10.54 | 35.41 ± 10.61 | 34.54 ± 10.57 |

| DAD | 68.04 ± 18.61 | 67.87 ± 18.74 | 68.13 ± 19.19 | 68.11 ± 18.09 | 68.04 ± 18.62 |

| CSDD | 11.98 ± 3.52 | 11.68 ± 3.31 | 11.92 ± 3.55 | 12.36 ± 3.55 | 11.94 ± 3.66 |

| NPI 12-item | 22.4 ± 13.4 | 23.0 ± 12.7 | 20.8 ± 12.5 | 24.5 ± 15.8 | 21.1 ± 12.0 |

NOTE. Data are presented as mean (standard deviation) or n (%).

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; ADAS-Cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale; CSDD, Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; DAD, Disability Assessment for Dementia; FAS, full analysis set; MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Examination; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

About 20% of patients had previously been treated with AChEI or memantine, and 18% of patients had previously received antidepressant treatment.

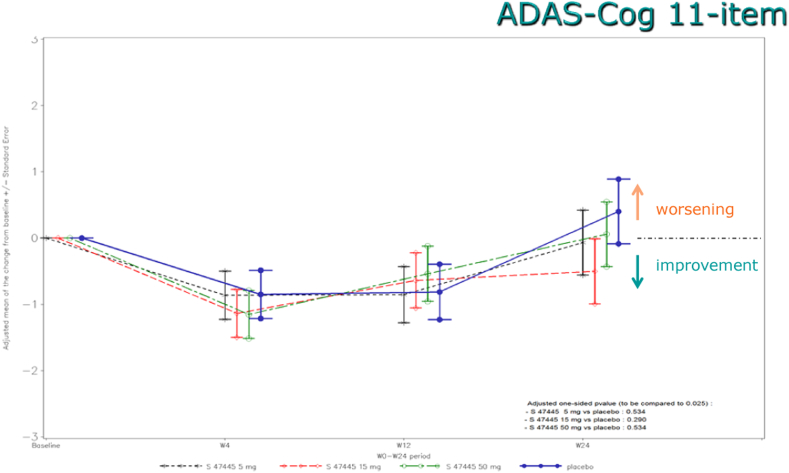

3.1. Primary outcome

After 24 weeks, there were no significant differences between S47445 groups and placebo on cognition (ADAS-Cog 11-item) (Fig. 2). The highest difference compared to placebo on ADAS-Cog 11-item total scores was observed with the S47445 15 mg group (−0.90 point; P value = .290). The adjusted mean changes from baseline to week 24 in ADAS-Cog total score were 0.35 (standard deviation 5.53) with placebo and −0.20 (4.91), −0.74 (5.43), and −0.05 (5.82) with S47445 5, 15, and 50 mg, respectively. Similar results were observed for the sensitivity analyses.

Fig. 2.

Adjusted mean of the change from Baseline in ADAS-Cog 11-item total score (FAS) during the 24-week follow-up. Abbreviations: ADAS-Cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale; FAS, full analysis set.

3.2. Secondary outcomes

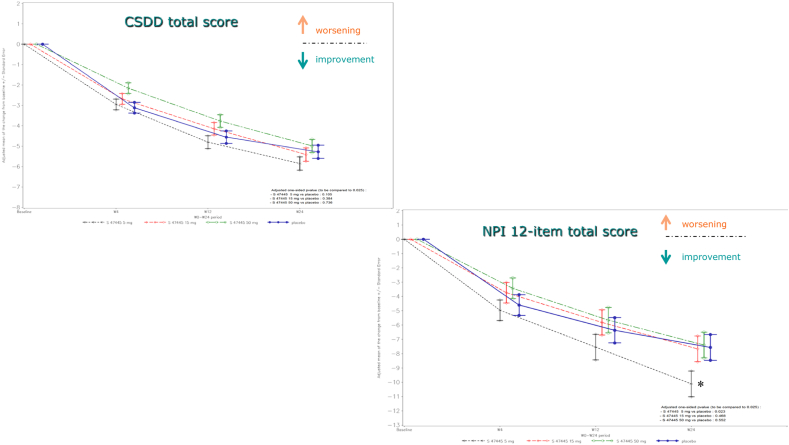

None of the effects of S47445 on key (DAD) and secondary efficacy end points was statistically significantly different from placebo, except on neuropsychiatric symptoms. The difference between S47445 5 mg and placebo on NPI 12-item total score was meaningful (−2.55 points [standard deviation = 1.27]; 95% confidence interval −5.06 to −0.05; P = .023; post hoc analysis), consistent with an improvement of neuropsychiatric symptoms in this group, compared to placebo. Domains which improved were agitation, depression, anxiety, apathy, irritability, and sleep disorders.

Over the 24-week period, CSDD and NPI 12-item total scores were decreased in all treatment groups over time including the placebo group (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Adjusted mean of the change from Baseline in CSDD total score and in NPI 12-item total score (FAS) during the 24-week follow-up. *P < .05. Abbreviations: CSDD, Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; FAS, full analysis set; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

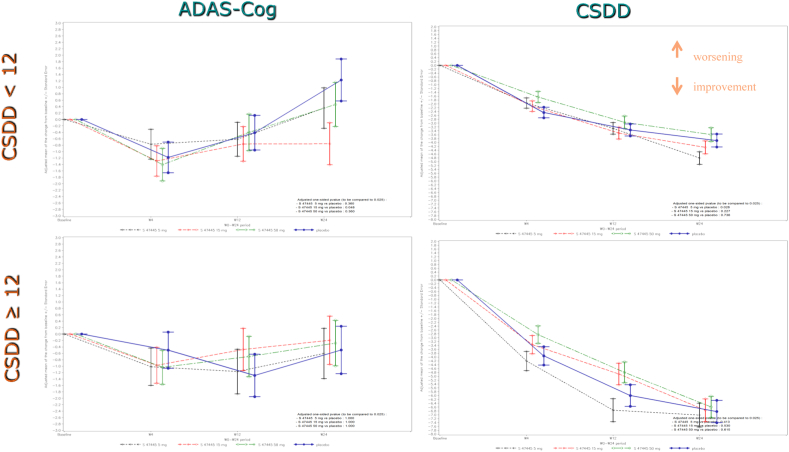

In the placebo group, patients (46%) exhibiting a higher score in depression at baseline (CSDD ≥12) showed a greater improvement on depressive symptoms (CSDD total score) and no worsening on cognition (ADAS-Cog 11-item score) over time compared to patients with fewer depressive symptoms (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Adjused mean for the change from Baseline in ADAS-Cog 11-item and CSDD total score (FAS) during the 24-week follow-up for subjects with CSDD < 12 and with CSDD ≥12. Abbreviations: ADAS-Cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale; CSDD, Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; FAS, full analysis set.

3.3. Safety

The number of patients who had at least one emergent adverse event (EAE) at week 26 was higher in the placebo group (50.4%, 65/129 patients) than in the total S47445 group (45.3%, 177/391 patients; 46.5% in the S47445 5-mg group, 37.7% in the 15-mg group, and 51.5% in the 50-mg group). Most EAEs in the S47445 groups were of mild (64.2%) or moderate (30.4%) intensity, resolved spontaneously or with an appropriate treatment (79.9%), and did not lead to treatment discontinuation (4.6% EAE that led to treatment withdrawal vs. 3.9% in placebo group).

Across all doses of S47445, the AE profiles were close to placebo. Treatment-emergent AEs occurring in at least 3% of the patients in either group are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of emergent adverse events (safety data set) for main period∗

| Placebo, N = 129 |

S47445 dose groups |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S47445 5 mg, N = 129 | S47445 15 mg, N = 130 | S47445 50 mg, N = 132 | Overall, N = 391 | ||

| Total EAEs, n (%) | 65 (50.4) | 60 (46.5) | 49 (37.7) | 68 (51.5) | 177 (45.3) |

| Serious EAEs, n (%) | 7 (5.4) | 4 (3.1) | 12 (9.2) | 6 (4.5) | 22 (5.6) |

| Premature withdrawal due to EAE, n (%) | 5 (3.9) | 2 (1.6) | 7 (5.4) | 9 (6.8) | 18 (4.6) |

| Most common EAEs at week 26† | |||||

| Nasopharyngitis | 6 (4.7%) | 4 (3.1%) | 3 (2.3%) | 7 (5.3%) | 14 (3.6) |

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increased | 4 (3.1%) | 2 (1.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | 6 (4.5%) | 9 (2.3) |

| Diarrhea | 4 (3.1%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (1.0) |

| Fall | 2 (1.6%) | 4 (3.1%) | 4 (3.1%) | 3 (2.3%) | 11 (2.8) |

| Headache | 5 (3.9%) | 3 (2.3%) | 4 (3.1%) | 4 (3.0%) | 11 (2.8) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (3.1%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) | 6 (1.5) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 0 | 2 (1.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (3.0%) | 7 (1.8) |

NOTE. N is the number of patients per group and n is the number of patients with at least one EAE; %: (n/N)*100.

Abbreviation: EAE, emergent adverse event.

Adverse events are listed according to the preferred terms in the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA), version 19.1.

Treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in at least 3% of patients in either group.

Serious EAEs were reported by 22 patients in the S47445 groups (5.6%) versus 7 patients in the placebo group (5.4%). Serious events reported by more than 1 patient in either group were fall, aggression, delirium, and chronic cardiac failure. No seizure was reported in any of the groups.

Two patients died during the first period of the study: one in the S47445 50-mg group and the other one in the placebo group.

There were no significant differences between groups in clinical laboratory values, blood pressure, weight, temperature, or ECG, including QT interval.

During the 28-week extension period with coadministration of donepezil, there was no relevant difference between S47445 groups and placebo regarding the frequency of EAEs. Four patients died: 2 patients in the S47445 15- and 50-mg groups and 2 patients in the placebo group.

In summary, this study showed a good safety profile of S47445 alone and in association with donepezil.

4. Discussion

AMPA-PAMs have been studied as potential therapeutics for the cognitive component of neurological disorders [23] and have been studied more intensively in the last decade [24], [25], [26]. Among drugs developed for AD [27], S47445 is the only agent to target the AMPA receptor through its allosteric modulation. Based on preclinical findings and human phase I studies [17], [18], we conducted a 24-week, phase II randomized controlled trial of S47445, a positive AMPA modulator. The trial outcomes demonstrate that a six-month course of three daily doses of the compound has no significant efficacy over placebo on the primary outcome, the ADAS-Cog. In addition, there were no significant differences between S47445 groups and placebo on functionality (DAD) and depressive symptoms (CSDD) of these patients.

In order to avoid an erroneous differential diagnosis for depression and AD, specific training for investigators was conducted before and during the study. As a result, the AD study population presented the expected depression profile. Onset of the current depressive symptoms was after AD diagnosis without a medical story of major depressive disorder, suggesting that the depression was linked to the neurodegenerative process. Depression often precedes or occurs early in the course of AD patients [28]. If a depressive episode occurs within 3 years before the diagnosis of AD, it is likely that these depressive symptoms were already linked to AD and not to recurrent or late-onset major depressive disorder. There is a consensus on the negative impacts of depression in AD patients and their caregivers.

Little is known about the natural history of depression in AD patients; it has been suggested that depression is more common as dementia progresses, except in severe dementia [29]. Others showed no association between severity of dementia and risk of depression [30], [31]. In the present study, we showed no correlation between AD severity (mild vs. moderate) and depression. The difficulty of evaluating depression and the inability of the patient to express their feelings could explain why depression severity remains unchanged while AD worsens.

Depression in AD is commonly comorbid with other neuropsychiatric symptoms. The study population also presented other neuropsychiatric symptoms (high NPI total score at baseline). These symptoms included apathy, anxiety, irritability, sleep, and appetite disorders. Depression and apathy are often present concomitantly [32]. The high prevalence of the association of both syndromes could be due to the overlap of signs such as fatigue, withdrawal, loss of interest, cognitive worsening, and irritability. Both apathy and depression relate to the patients' performance in individual activities, motivation and affect. However, core symptoms are different. Patients with depression present emotional change (depressed mood), and patients with apathy present primarily with diminished motivation.

In the present study, a placebo effect on cognition was observed, especially on the first 3 months and to a greater extent on depression and neuropsychiatric symptoms throughout the study [10], [11]. On the subset of subjects with “probable major depression” (baseline CSDD score ≥12), these patients may be more sensitive to the placebo effect of the study. Finally, the lack of accurate reporting by the patient/informant, overlap of symptoms of depression and dementia, inadequate sensitization of clinicians to data collection, and limitations of tools may have led to difficulties in diagnosis and assessment of treatment.

There was a mild cognitive decline of the placebo group which was particularly evident during the last 3 months of the study. These observations raise questions on the duration of the clinical trial for a symptomatic treatment, the care given to patient and informant, and the standard assessment tools used on this population. Recent studies show that up to 30% of patients with the clinical phenotype of AD do not have brain amyloidosis when studied with amyloid positron emission tomography or cerebrospinal fluid amyloid studies and do not have the clinico-biological syndrome of AD [33]. The modest rate of apolipoprotein e4 carriers (47% compared to 65% of biologically confirmed AD) suggests that some non-AD patients were included in this trial. The trajectory and treatment response profile of the non-AD patients included in trials is unknown. In addition, the exclusion of patients on cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine may have resulted in recruiting a somewhat atypical AD population into the trial. These factors may have contributed to the negative outcome of this trial and represent issues to be considered in other trials of symptomatic agents.

Our findings are similar to those obtained in AD patients with another AMPA-PAM (LY451395, mibampator) which did not show statistically significant effects on the ADAS-Cog following 8 weeks of treatment [34]. The only positive effect of the drug was obtained at the 5-mg dose on the mean NPI 12-item total score, with improvements of agitation, depression, anxiety, apathy, irritability, and sleep disorders. Interestingly, this effect was observed at a dose that demonstrated an enhancement of functional connectivity between brain networks in healthy elderly subjects, which may give support to the use of functional imaging in early clinical development phase for the choice of drug dosing [35]. This specific effect on NPI has been also reported in the study by Chappell et al. [34] with an 8-week treatment period with mibampator. However, upon longer treatment duration, mibampator failed to separate from placebo, when a focus was made on agitation/aggression symptoms measured by a subscale of the NPI [36]. Together, these findings suggest that AMPA-PAMs can exert effects on neuropsychiatric symptoms of AD patients, but the effect is not dose related and the effect size seems insufficient compared to antidementia drugs (AChE inhibitors, memantine) used to improve both cognitive functions and behavioral symptoms [27], [37].

S47445 was well tolerated in this population with no significant difference from placebo for EAEs, SAEs, and withdrawals. It is important to note that despite the study population, few withdrawals were recorded. Despite the fact that treatments such as antidementia agents, antidepressants, neuroleptics, and anxiolytics/hypnotics (except benzodiazepine with a short/medium half-lives) were forbidden, patients were relatively well managed and remained in the study.

Given its procognitive and antidepressant properties, S47445 was considered as a promising candidate for the symptomatic treatment of memory deficits in patients who have a clinical diagnosis of both depression and probable AD of mild to moderate severity, even if animal models of AD presented a very poor predictive validity for the sporadic form of the human disease [38]. The study failed to demonstrate cognitive benefit on the primary outcome, although behavior improved. Knowledge about the effects of AMPA-PAMs effects on human memory is limited, and our findings add more weight to the assumption that these agents do not exert a clear benefit [39], [40], [41]. Null findings advance the field, and the information gained from this study can inform future clinical trials involving AMPA modulation for both cognitive and behavior outcomes.

Research in context.

-

1.

Systematic review: This paper described the results of a phase 2 clinical trial performed in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. The tested drug is a positive modulator of AMPA receptors, S47445, which presented both procognitive and antidepressant properties. Alzheimer’s patients, who presented depressive symptoms, were included in this study.

-

2.

Interpretation: The study failed to demonstrate a cognitive benefit, although a slight behavioural positive effect was observed. Null findings advance the AD field, a domain that knows a high failure rate in drug development.

-

3.

Future directions: The information gained from this study can inform future clinical trials involving AMPA modulation for both cognitive and behaviour outcomes, and by increasing data in this population which is often excluding from clinical trial assessing treatments for cognition.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Vanessa Mourlhon for her helpful assistance during all the study and thank all patients, informants, sites and their staff, principal investigators, and national coordinators.

List of principal investigators on each country:

BRG: Pr Latchezar Traykov, Pr Ivan Milanov, Dr Penka Atanassova, Pr Ara Kaprelyan, Pr Lyubomir Haralanov. BRA: Pr Paulo Henrique Ferreira Bertolucci, Dr Paulo Brito, Dr Marcia Lorena Fagundes Chaves, Dr Hamilton Grabowski, Pr Acioly L T Lacerda, Dr José Ibiapina Siqueira Neto, Dr Viviane Zetola, Dr Antonio Carlos da Silva. CHL: Dr Manuel Lavados, Dr Sergio Gloger, Dr Luis Barra Ahumada, Dr Jaime Solis, Dr Alberto Mario Vargas Cañas. CZE: Dr Michal Bajacek, Dr Ilona Divacka, Dr Jiri Pisvejc, Dr Petra Votypkova, Dr Klaudia Vodickova-Borzova, Dr Michaela Klabusayova. DEU: Pr Matthias Riemenschneider, Dr Heike Benes, Pr Joerg Berrouschot, Dr Ralf Bodenschatz, Dr Joerg Peltz, Dr Joachim Springub, Pr Georg Adler. HUN: Pr Janos Kalman, Dr Attila Valikovics, Dr Tibor Kovacs, Dr Maria Satori, Pr Sandor Fekete, Dr Gabor Feller, Dr Robert Karpati, Dr Alexander Kancsev, Dr Eva Mathe. JPN: Dr Tomofumi Shinozaki, Dr Satoshi Nakamura, Dr Shuta Toru, Dr Takashi Asada. MEX: Pr Santiago Ramirez Diaz, Dr Ricardo Salinas Martinez, Dr Abraham Vazquez Garcia, Mario Valdés Dávila. POL: Dr Maciej Czarnecki, Dr Andrzej Fidor, Pr Andrzej Szczudlik, Dr Dorota Ussorowska, Dr Izabela Halina Winkel, Pr Catalina Tudose, Dr Rita Ioana Platona. RUS: Pr Svetlana Gavrilova, Dr Yaroslav Kalyn, Dr Tatiana Safarova, Dr Nadezhda Korobeynikova, Pr Miroslav Odinak, Pr Vladimir Parfenov, Pr Sofia Sluchevskaya, Dr Inna Kiseleva, Pr Dina Khasanova, Pr Oleg Shiryaev. SVK: Dr Livia Vavrusova, Dr Jana Greskova, Dr Ivan Doci. ZAF: Dr Felix Potocnik, Dr Gert Bosch, Dr Jaco Cilliers, Dr Christo Coetzee, Dr Jannie van der Westhuizen, Dr Chris Verster.

Funding for this study was provided by Institut de Recherches Internationales Servier (Suresnes, France).

Footnotes

Trial registration number: NCT02626572.

Dr. Cummings has provided consultation to Acadia, Accera, Actinogen, Alkahest, Allergan, Alzheon, Avanir, Axsome, BiOasis, Biogen, Bracket, Denali, Diadem, EIP Pharma, Eisai, Forum, Genentech, Green Valley, Grifols, Hisun, Kyowa Kirin, Lilly, Lundbeck, Medavante, Merck, Otsuka, Pain Therapeutics, Proclera, QR, Resverlogix, Roche, Samus, Takeda, Teva and United Neuroscience pharmaceutical and assessment companies. Dr. Cummings has stock options in Prana, Neurokos, ADAMAS, MedAvante, QR Pharma, Samus, Green Valley, BiOasis. Dr. Cummings owns the copyright of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. K. Bernard, S. Gouttefangeas, S. Bretin, S. Galtier, and M. Pueyo are employees of Institut de Recherches Internationales Servier.

References

- 1.Robert P.H., Verhey F.R., Byrne E.J., Hurt C., De Deyn P.P., Nobili F. Grouping for behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia: clinical and biological aspects. Consensus paper of the European Alzheimer disease consortium. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:490–496. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyketsos C.G., Olin J. Depression in Alzheimer's disease: overview and treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyketsos C.G., Steinberg M., Tschanz J.T., Norton M.C., Steffens D.C., Breitner J.C. Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:708–714. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez-Martinez M., Castro J., Molano A., Zarranz J.J., Rodrigo R.M., Ortega R. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008;5:61–69. doi: 10.2174/156720508783884585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barca M.L., Persson K., Eldholm R., Benth J.S., Kersten H., Knapskog A.B. Trajectories of depressive symptoms and their relationship to the progression of dementia. J Affect Disord. 2017;222:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee H.B., Lyketsos C.G. Depression in Alzheimer's disease: heterogeneity and related issues. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:353–362. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00543-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olin J.T., Schneider L.S., Katz I.R., Meyers B.S., Alexopoulos G.S., Breitner J.C. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:125–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teng E., Ringman J.M., Ross L.K., Mulnard R.A., Dick M.B., Bartzokis G. Diagnosing depression in Alzheimer disease with the national institute of mental health provisional criteria. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:469–477. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318165dbae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sepehry A.A., Lee P.E., Hsiung G.R., Beattie B.L., Feldman H.H., Jacova C. The 2002 NIMH Provisional Diagnostic Criteria for Depression of Alzheimer's Disease (PDC-dAD): Gauging their Validity over a Decade Later. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58:449–462. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.An H., Choi B., Park K.W., Kim D.H., Yang D.W., Hong C.H. The Effect of Escitalopram on Mood and Cognition in Depressive Alzheimer's Disease Subjects. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55:727–735. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banerjee S., Hellier J., Dewey M., Romeo R., Ballard C., Baldwin R. Sertraline or mirtazapine for depression in dementia (HTA-SADD): a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:403–411. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60830-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munro C.A., Longmire C.F., Drye L.T., Martin B.K., Frangakis C.E., Meinert C.L. Cognitive outcomes after sertaline treatment in patients with depression of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:1036–1044. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31826ce4c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rao V., Spiro J.R., Rosenberg P.B., Lee H.B., Rosenblatt A., Lyketsos C.G. An open-label study of escitalopram (Lexapro) for the treatment of 'Depression of Alzheimer's disease' (dAD) Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:273–274. doi: 10.1002/gps.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sepehry A.A., Lee P.E., Hsiung G.Y., Jacova C. Stay the course--is it justified? Lancet. 2012;379:220. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harding R., Peel E. 'He was like a zombie': off-label prescription of antipsychotic drugs in dementia. Med L Rev. Mar. 2013;21:243–277. doi: 10.1093/medlaw/fws029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cummings J., Zhong K. Trial design innovations: Clinical trials for treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's Disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;98:483–485. doi: 10.1002/cpt.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bretin S., Louis C., Seguin L., Wagner S., Thomas J.Y., Challal S. Pharmacological characterisation of S47445, a novel positive allosteric modulator of AMPA receptors. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendez-David I., Guilloux J.P., Papp M., Tritschler L., Mocaer E., Gardier A.M. S47445 Produces Antidepressant- and Anxiolytic-Like Effects through Neurogenesis Dependent and Independent Mechanisms. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:462. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calabrese F., Savino E., Mocaer E., Bretin S., Racagni G., Riva M.A. Upregulation of neurotrophins by S47445, a novel positive allosteric modulator of AMPA receptors in aged rats. Pharmacol Res. 2017;121:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giralt A., Gomez-Climent M.A., Alcala R., Bretin S., Bertrand D., Maria Delgado-Garcia J. The AMPA receptor positive allosteric modulator S47445 rescues in vivo CA3-CA1 long-term potentiation and structural synaptic changes in old mice. Neuropharmacology. 2017;123:395–409. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciuciu P., Bougacha S., Boumezbeur F., Desmidt S., Ginistry C., Laurier L. Effect of S47445 on functional connectivity at rest and during a task, and on glutamate concentrations in elderly subjects. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2016;3:S274–S275. 9th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer's Disease (CTAD), San Diego, CA (08/12/2016 - 10/12/2016) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dmitrienko A., Tamhane A.C. Mixtures of multiple testing procedures for gatekeeping applications in clinical trials. Stat Med. 2011;30:1473–1488. doi: 10.1002/sim.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee K., Goodman L., Fourie C., Schenk S., Leitch B., Montgomery J.M. AMPA Receptors as Therapeutic Targets for Neurological Disorders. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2016;103:203–261. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrow J.A., Maclean J.K., Jamieson C. Recent advances in positive allosteric modulators of the AMPA receptor. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2006;9:571–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pirotte B., Francotte P., Goffin E., de T.P. AMPA receptor positive allosteric modulators: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2013;23:615–628. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2013.770840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ward S.E., Bax B.D., Harries M. Challenges for and current status of research into positive modulators of AMPA receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cummings J.L., Morstorf T., Lee G. Alzheimer's drug-development pipeline: 2016. Alzheimer Demen. 2016;2:222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saczynski J.S., Beiser A., Seshadi S., Auerbach S., Wolf P.A., Au R. Depressive symptoms and risk of dementia. Neurology. 2010;75:35–41. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e62138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinberg M., Shao H., Zandi P., Lyketsos C.G., Welsh-Bohmer K.A., Norton M.C. Point and 5-year period prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:170–177. doi: 10.1002/gps.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Craig D., Mirakhur A., Hart D.J., McIlroy S.P., Passmore A.P. A cross-sectional study of neuropsychiatric symptoms in 435 patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:460–468. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.6.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benoit M., Staccini P., Brocker P., Benhamidat T., Bertogliati C., Lechowski L. [Behavioral and psychologic symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: results of the REAL.FR study] Rev Med Interne. 2003;24(Suppl 3):319s–324s. doi: 10.1016/s0248-8663(03)80690-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benoit M., Berrut G., Doussaint J., Bakchine S., Bonin-Guillaume S., Frémont P. Apathy and depression in mild Alzheimer's disease: a cross-sectional study using diagnostic criteria. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;31:325–334. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-112003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sevigny J., Suhy J., Chiao P., Chen T., Klein G., Purcell D. Amyloid PET screening for enrichment of early-stage Alzheimer disease clinical trials: experience in a Phase 1b clinical trial. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2016;30:1–7. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chappell A.S., Gonzales C., Williams J., Witte M.M., Mohs R.C., Sperling R. AMPA potentiator treatment of cognitive deficits in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2007;68:1008–1012. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260240.46070.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borsook D., Becerra L., Fava M. Use of functional imaging across clinical phases in CNS drug development. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e282. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trzepacz P.T., Cummings J., Konechnik T., Forrester T.D., Chang C., Dennehy E.B. Mibampator (LY451395) randomized clinical trial for agitation/aggression in Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:707–719. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212002141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuronen M., Koponen H., Nykanen I., Karppi P., Hartikainen S. Use of anti-dementia drugs in home care and residential care and associations with neuropsychiatric symptoms: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:100. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0102-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mullane K., Williams M. Preclinical Models of Alzheimer's Disease: Relevance and Translational Validity. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2019;84:e57. doi: 10.1002/cpph.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson S.A., Simmon V.F. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled international clinical trial of the Ampakine CX516 in elderly participants with mild cognitive impairment: a progress report. J Mol Neurosci. 2002;19:197–200. doi: 10.1007/s12031-002-0032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lynch G., Granger R., Ambros-Ingerson J., Davis C.M., Kessler M., Schehr R. Evidence that a positive modulator of AMPA-type glutamate receptors improves delayed recall in aged humans. Exp Neurol. 1997;145:89–92. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wezenberg E., Verkes R.J., Ruigt G.S., Hulstijn W., Sabbe B.G. Acute effects of the ampakine farampator on memory and information processing in healthy elderly volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1272–1283. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]