Abstract

Global and disease-group genetic testing is replacing single-gene molecular diagnostics. Bullich et al. demonstrate that gene panel analysis can result in a high yield of genetic diagnoses in cystic and familial glomerular populations. As the complexity of defining specific inherited kidney diseases becomes more apparent, a broader role for panel-based genomic testing in nephrology is now warranted. The resulting firm diagnosis can inform family planning decisions and aid prognostics and patient management.

Next-generation sequencing methods have revolutionized genetic analysis in the past decade or so, moving from Sanger-based single-gene analysis to screening of disease panels, whole-exome sequencing, and even whole-genome analysis. These methodologies are the basis of a new generation of clinical molecular testing. The advantages offered by this broader testing approach have been embraced by pediatricians and some other specialties (e.g., neurology), but the approach has been slow to take root in adult nephrology. In this light it is helpful to note that inherited disorders, many individually rare, account for the majority of end-stage renal disease cases that present in infants, at least 25% of those presenting in children, and more that 10% presenting in adults.1

A growing number of cohorts have been described recently that illustrate the utility of a more global genetic screening approach in adult and pediatric nephrology, as illustrated in the study by Bullich et al.2 (2018) in this issue of Kidney International. The focus of this study is inherited cystic and glomerular diseases and includes screening with a 140 candidate gene panel. A very high level of sensitivity (99%) is found in the validation cohort (116 patients). The diagnostic cohort consists of cystic (n = 207) and glomerular (n = 98) cases over aage range, with wide most of the glomerular cases having a positive family history. Overall, in 78% of the cystic and 62% of the glomerular cases a genetic cause was identified; including 80%, 72%, and 80% of the cystic and 100%, 52%, and 70% of the glomerular in the infantile, childhood, and adult age groups, respectively. In the non-adult cystic populations, 8 NPHP-related ciliopathy genes, plus PAX2, the tuberous sclerosis genes TSC1 and TSC2, the autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease gene PKHD1, the autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) genes PKD1 and PKD2, and HNF1B are implicated. In the adult cases, as well as the expected PKD1 and PKD2, mutations to PKHD1, the ciliopathy gene WDR19, HNF1B, TSC1, TSC2, the orofaciodigital syndrome gene OFD1, and the autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease gene PRKCSH are detected. The range of disease genes, even in adults, indicates the value of the broad gene panel approach. In the glomerular group, the steroid resistant nephrotic syndrome genes NPHS1, WT1, LMX1B, CUBN, and NUP93 are detected, plus X-linked, dominant, and recessive Alport syndrome genes and mutations to PAX2, COL4A1, and MYH9. Evidence of possible digenic disease, due to a PKD1 plus PKD2 mutation, or combinations of the Alport syndrome genes COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5 or biallelic ADPKD,3 also highlight the value of screening multiple genes. The ability to detect larger rearrangements, without additional testing, and mosaicism further emphasize the advantages of the next-generation sequencing gene panel approach.

Much debate presently focuses on the best format for screening patients for inherited (kidney) diseases. While whole-genome analysis provides data on all genomic changes (exonic, intronic, and intergenic), the sequencing costs and complexity of data analysis and storage mean that it is generally not favored for diagnostics, although this may change in the not too distant future. Whole-exome sequencing, in which just the coding of 1% to 2% of the genome is captured and sequenced, reduces sequencing costs, and analysis can be simplified by focusing on a set of genes implicated in a disease state. However, there may still be advantages of the smaller gene-panel approach2 in terms of cost reductions due to greater sample multiplexing at the capture and sequencing stages. A specifically designed panel, rather than whole-exome sequencing, may also more effectively screen difficult genes, such as the segmentally duplicated PKD1.4,5 In addition, as the genes analyzed are associated with kidney disease, complications of detecting and reporting changes unrelated to the phenotype are reduced.

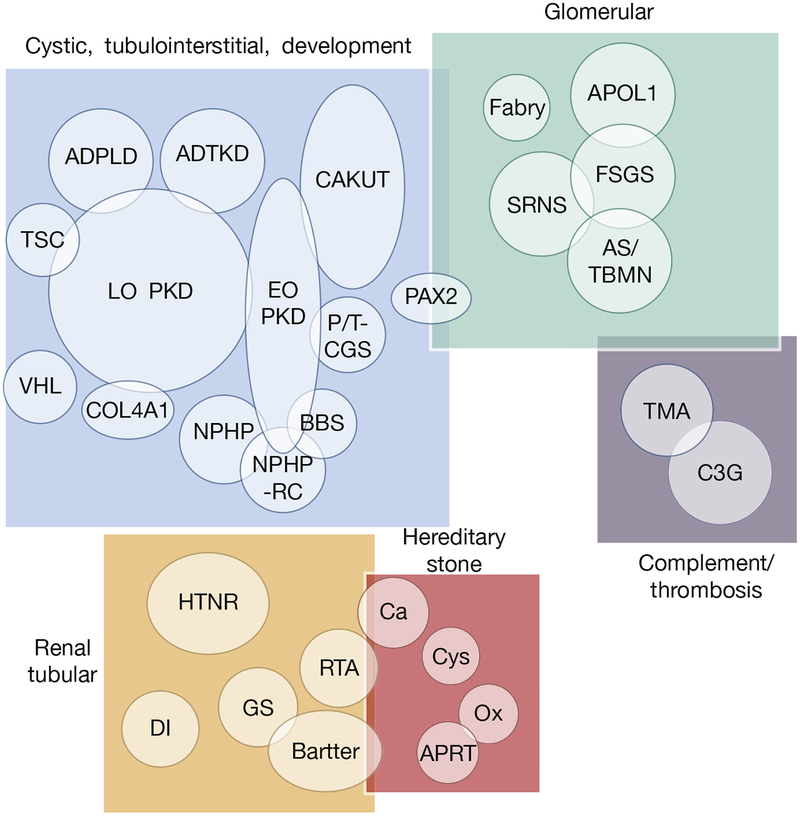

So, if gene panel analysis is of some value, what is the ideal size? The finding of Pax2 mutations in both the cystic and glomerular phenotypic groups2 illustrates genic overlap, which is often observed between different kidney disease subgroups.3 Additional renal diseases, such as early-onset stone disease,6 tubular disorders, tubulointerstitial diseases, and complement and/or thrombosis disorders,7 can have a monogenic etiology; thus, a broad panel of known renal disease genes appears to make sense (Figure 1). The Iowa Institute of Medical Genetics offers such a kidney disease panel, with the present iteration having 246 genes. Obviously, this number is a moving target, with new renal disease genes constantly being identified, but periodic updating of the panel is relatively straightforward. Because the cost of such genetic analysis is now often no more than that of comprehensive radiological imaging, nephrologists may consider adding it more often to their diagnostic armamentarium.

Figure 1 |. Diagram showing kidney diseases and disease groupings in which genetic testing can be of value.

Overlap between disease groupings and diseases in terms of shared genes is illustrated. ADPLD, autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease; ADTKD, autosomal dominant tubulointerstisial kidney disease; APOL1, apolipoprotein L1; APRT, adenine phosphoribosyltransferase; AS/TBMN, Alport syndrome and thin basement membrane disease; BBS, Bardet–Biedl syndrome; Bartter, Bartter syndrome; C3G, C3 glomulopathies; Ca, calcium stone; CAKUT, congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract; COL4A1, alpha-1 subunit of collagen type IV; Cys, cystine stone disease; DI, diabetes insipidus; EO PKD, early-onset polycystic kidney disease, including ARPKD; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; Fabry, Fabry disease; GS, Gitelman syndrome; HTNR, hypertension related; LO PKD, late-onset polycystic kidney disease, including ADPKD; NPHP, nephronophthisis; NPHP-RC, nephronophthisis-related ciliopathies; Ox, oxalate stonedisease; P/T-CGS, PKD1/TSC2 contiguous genesyndrome; RTA, renal tubular acidosis; SRNS, steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome; TMA, thrombotic microangiopathies; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; VHL, von Hippel-Lindau syndrome.

The value of comprehensive genetic testing certainly varies from disease to disease, but overall a firm diagnosis is an important consideration. For instance, tubular interstitial disease can be rather nonspecific, but a finding of mutations in an autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease gene8 provides a diagnosis with implications for other family members and possibly family planning. In the case of early-onset cystic disease, a firm determination of etiology can aid future family planning choices, including the possibility of preimplantation genetic diagnoses. In this case, via in vitro fertilization, embryos can be tested for the disease gene and only unaffected embryos implanted. In ADPKD, while genetic testing is presently rarely used for diagnostics in at-risk individuals because of the ease of imagebased methods, cheaper and more reliable molecular testing would make it more attractive. When clarifying the risk of a potential kidney donor with 1 or 2 cysts, a panel-based analysis could not only determine the status of the familial mutation but could test whether another significant variant (hypomorphic ADPKD, autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease, HNF1B, or other cystogene) is present. Genetic testing of suspected ADPKD patients with early-onset polycystic kidney disease or mild disease, with a negative family history, or atypical radiological presentations can also clarify the diagnosis.3 As therapies become available for ADPKD, identifying the specific causative gene and allele can help determine the disease prognosis, along with imaging, clinical, and family history data, and so influence treatment decisions. Detection of biallelic pathogenic APOL1 alleles may also be significant in the transplant setting.

Obtaining a genetic diagnosis can change disease management, leading to the initiation or change of treatment. In atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and other complement-and/or thrombosis-related disorders with many different genes involved,7 gene panel–based diagnostics can determine whether expensive treatments many be of value. Genetic analysis is the gold standard for diagnosing hereditary kidney stone diseases, and in the case of adenine phosphoribosyl-transferase deficiency can lead to starting appropriate treatment. In the case of primary hyper-oxaluria, genetic analysis can provide a firm diagnosis with detection of mutations in one of the known genes, AGXT, GRHPR, or HOGA1, and finding mis-targeting AGXT mutations may indicate specific treatment options. Due to recurrent disease after transplantation, a positive diagnosis can help determine whether liver plus kidney transplants are indicated.

Genetic analysis via a gene panel does not always result in a firm diagnosis. Some areas, especially guanine-and cytosine-rich ones, may not be well captured and sequenced (see PKD1 exon 12), mutations to the complex autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease gene, MUC1, are not detected by gene-panel screening, and the disease gene may not have been included on the panel. Interpretation of the pathogenicity of in-frame changes (variants of unknown significance) can sometime be difficult. The presence of large databases displaying the frequency of variants on more than 100,000 “normal” alleles of different ethnicity (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) are invaluable, because alleles associated with monogenic disease are rare. Variant evaluation programs, assessing the chemical difference of a substitution, and the conservation of the residue in orthogs and domain structures can be helpful, especially if multiple programs are tested (http://marrvel.org/). Another aid to interpretation is sufficient clinical data to describe the phenotype, and data-bases of detected pathogenic variants, including for specific diseases, can also be of value. Ultimately, it is important to report results using developed criteria, with an emphasis on not over-interpreting the available data, while trying to provide a clear diagnosis.9 Finally, it is important to remember that a genetic diagnosis, despite legislative progress, may result in discrimination, so appropriate genetic counseling and patient agreement are important before such testing.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The author declared no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Devuyst O, Knoers NV, Remuzzi G, et al. Rare inherited kidney diseases: challenges, opportunities and perspectives. Lancet. 2014;383:1844–1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bullich G, Domingo-Gallego A, Vargas I, et al. A kidney-disease gene panel allows a comprehensive genetic diagnosis of cystic and glomerular inherited kidney diseases. Kidney Int. 2018;94:363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornec-Le Gall E, Torres VE, Harris PC. Genetic complexity of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney and liver diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trujillano D, Bullich G, Ossowski S, et al. Diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease using efficient PKD1 and PKD2 targeted next-generation sequencing. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2014;2:412–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisenberger T, Decker C, Hiersche M, et al. An efficient and comprehensive strategy for genetic diagnostics of polycystic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daga A, Majmundar AJ, Braun DA, et al. Whole exome sequencing frequently detects a monogenic cause in early onset nephrolithiasis and nephrocalcinosis. Kidney Int. 2018;93:204–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bu F, Borsa NG, Jones MB, et al. High-throughput genetic testing for thrombotic microangiopathies and C3 glomerulopathies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:1245–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckardt KU, Alper SL, Antignac C, et al. Autosomal dominant tubulointerstitial kidney disease: diagnosis, classification, and management–A KDIGO consensus report. Kidney Int. 2015;88:676–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]