Abstract

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a common and life-threatening hematological disorder, affecting approximately 400,000 newborns annually worldwide. Most SCD births occur in low-resource countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where limited access to accurate diagnostics results in early mortality. We evaluated a prototype immunoassay as a novel, rapid, and low-cost point-of-care (POC) diagnostic device (Sickle SCAN™) designed to identify HbA, HbS, and HbC. A total of 139 blood samples were scored by three masked observers and compared to results using capillary zone electrophoresis. The sensitivity (98.3–100%) and specificity (92.5–100%) to detect the presence of HbA, HbS, and HbS were excellent. The test demonstrated 98.4% sensitivity and 98.6% specificity for the diagnosis of HbSS disease and 100% sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of HbSC disease. Most variant hemoglobins, including samples with high concentrations of HbF, did not interfere with the ability to detect HbS or HbC. Additionally, HbS and HbC were accurately detected at concentrations as low as 1–2%. Dried blood spot samples yielded clear positive bands, without loss of sensitivity or specificity, and devices stored at 37°C gave reliable results. These analyses indicate that the Sickle SCAN POC device is simple, rapid, and robust with high sensitivity and specificity for the detection of HbA, HbS, and HbC. The ability to obtain rapid and accurate results with both liquid blood and dried blood spots, including those with newborn high-HbF phenotypes, suggests that this POC device is suitable for large-scale screening and potentially for accurate diagnosis of SCD in limited resource settings.

Introduction

Inherited disorders of hemoglobin, primarily sickle cell disease (SCD) and the β-thalassemias, represent an enormous and unaddressed global public health problem [1,2]. Conservative estimates suggest that approximately 400,000 infants are born with SCD each year worldwide [1,3–5]. The most common and severe form is homozygous hemoglobin SS (HbSS) disease, which represents over 75% of annual SCD births and occurs most frequently in sub-Saharan Africa and India. The second most common form of SCD is compound heterozygous hemoglobin SC (HbSC) disease, which is found mostly in West Africa and the Americas. Over 90% of SCD births occur in low- and middle-income countries, and over 9 million women who are carriers for a significant hemoglobin disorder become pregnant each year [1,6]. In the vast majority of these cases, the pregnant women and their partners are not aware of the type or significance of the hemoglobin variants that they carry, and outside of Europe and the United States, neonatal screening programs are usually not available to identify affected infants.

The lack of appropriate and timely diagnosis of SCD has life-threatening consequences for affected infants and young children. In North America and many European countries, neonatal screening for hemoglobinopathies provides early diagnosis of SCD, and allows provision of parental SCD education and early initiation of life-saving preventive care [7,8]. Without the availability of early diagnosis, most children born with SCD in limited-resource settings will die within the first several years of life, usually before a diagnosis is even made, presumably due to severe anemia or infection [9]. WHO estimates that SCD contributes the equivalent of 5% of all under-five mortality on the African continent and up to 16% in some high-prevalence African countries [10]. The importance of early diagnosis of SCD is beginning to be recognized and several pilot newborn screening programs have been developed across sub-Saharan Africa [11–16]. While most laboratory methods that diagnose SCD are accurate, such as hemoglobin electrophoresis by isoelectric focusing (IEF), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE), these techniques require expensive equipment, reagents, and electricity, as well as specialized technology with training, and typically provide results several days after blood collection. In limited-resource settings with unreliable telephone service and no definitive street addresses, it can be difficult to track and inform families of infants with positive screening results [11]. For these reasons, the development and implementation of a simple, rapid, inexpensive, and accurate point-of-care (POC) diagnostic tool for SCD is urgently needed. Within the United States, the National Institutes of Health has recognized the importance of POC diagnostics for SCD through a recent Request for Applications for the development of such assays [17]. Due to the importance of timely diagnosis and early intervention, the development of a simple, robust, accurate, reliable, and affordable POC device could be transformative for the identification and management of SCD in low-resource settings such as sub-Saharan Africa.

Recently, there have been several reports of POC devices that quickly establish the diagnosis of SCD based on differential characteristics between HbAA and HbSS erythrocytes, including a paper-based test that quantifies sickle hemoglobin and a density-based rapid test using aqueous multiphase systems [18–21]. A third POC immunoassay test was recently described, reporting near perfect sensitivity and specificity for the identification of HbA, HbS, and HbC in normal, trait, and disease samples [22]. We designed and performed simultaneous experiments using the same POC device, prior to knowledge of this publication; however, with several important differences. Our work included rigorous experiments designed to carefully evaluate multiple important performance aspects of the POC assay from an unbiased perspective, with an overall objective of determining whether this test is likely to be an effective and reliable diagnostic or screening test.

Methods

Description of the device.

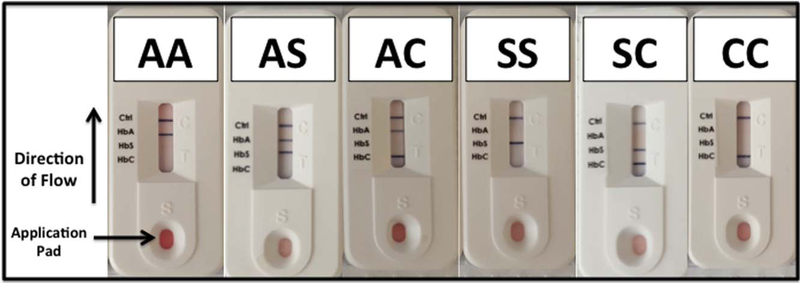

The Sickle SCAN™ (Biomedomics, Inc., Research Triangle Park, NC) device is a lateral flow chromographic qualitative immunoassay for the rapid determination of the presence or absence of HbA, HbS, and HbC that is intended to diagnose the common forms of SCD [22]. The testing cartridge has four detection bands, including a distal control band that appears when the sample has flowed to the end of the testing strip (Fig. 1). The presence of normal (HbA) or variant (HbS or HbC) hemoglobins is indicated by a dark blue line in the specific region indicated on the device.

Figure 1.

POC device and results for common hemoglobin patterns. The Sickle SCAN POC device is an immunoassay that utilizes lateral-flow technology to identify the presence of HbA, HbS, and HbC. The sample is applied on the pad at the bottom of the device, and the liquid flows toward the final control band (Ctrl), with individual bands for HbC, HbS, and HbA spaced equally along the testing strip. The six common combinations of HbA, HbS, and HbC are illustrated.

Study objectives.

The main objectives of this study included a determination of the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and ease of using the Sickle SCAN device to identify the presence of HbA, HbS, and HbC using blood samples from pediatric and adult patients with known or suspected hemoglobin disorders. All experiments were performed using deidentified blood samples previously tested at the Erythrocyte Diagnostic Laboratory at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, using a research protocol approved by the local Institutional Review Board. Additional study objectives included (1) analysis of samples containing high fetal hemoglobin (HbF) and other variant hemoglobins; (2) comparison of liquid blood samples to dried blood spot (DBS) cards; and (3) reliability of the results after storing the devices at warm temperatures.

Blood samples.

This study included the analysis of the following types of blood specimens: (1) venous samples collected in EDTA and stored at 4°C until analysis;(2) venous samples transferred to filter paper (Whatman FTA™ Classic Cards, GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) to create DBS; and (3) artificial “spiked” samples with low fixed percentages of HbA, HbS, and HbC. The majority of samples included combinations of HbA, HbS, or HbC, but in order to identify potential interference by hemoglobin variants, some samples included both common and uncommon variants that were available for testing. POC devices were kept at room temperature, except for some experiments that involved storage at 37°C for 30 days, to evaluate the effects of elevated temperature.

Sample analysis.

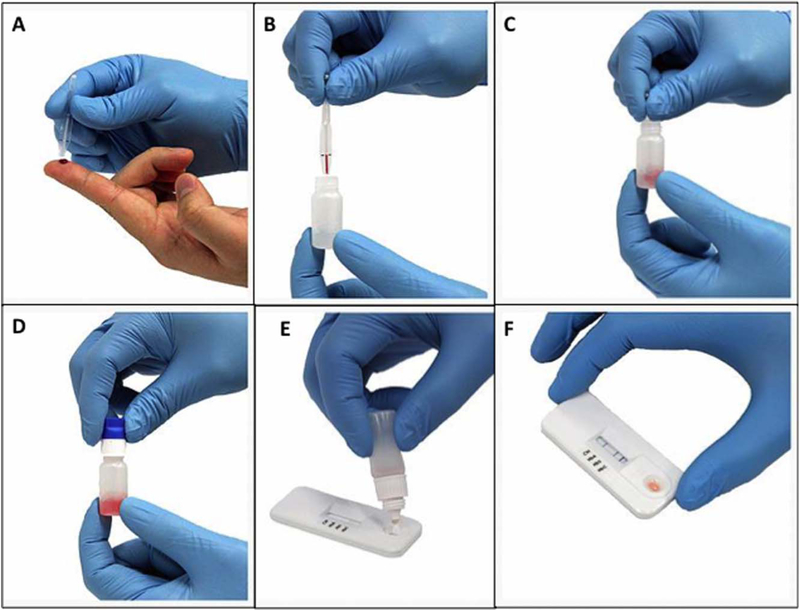

Blood samples collected in EDTA were analyzed by CZE to determine the types and percentages of normal and abnormal hemoglobins in each sample; these results were used to identify samples for testing by the POC device and served as the reference value. Variants detected by CZE were confirmed by a second method (citrate agar electrophoresis or isoelectric focusing). Neither the results nor the types of hemoglobins were discussed with the investigators evaluating the device, so that all scoring was performed by masked observers. These three naïve observers read the instructions in the package insert but received no formal training or hands-on experience with the test prior to the results presented here. The Sickle SCAN kit includes tubes prefilled with 1.0 mL of buffer, which lyses erythrocytes and releases hemoglobin. As per the manufacturer’s recommendation, whole blood samples were tested by adding 5 μL of blood from the EDTA tube to the prefilled buffer container, mixing by inverting the tube three times, discarding the first 3 drops of the lysate, and then applying 5 drops to the testing cartridge. For DBS samples, a 3 mm punch from the card was dropped into the prefilled buffer container, and then the same procedure was followed. Five minutes after sample application, the three observers visually scored each sample independently for the presence or absence of all 4 potential bands (HbA, HbS, HbC, and control). Figure 2 illustrates the individual steps of the assay and the Supplemental Video demonstrates the assay procedures and result interpretation in real time.

Figure 2.

Steps of the point-of-care assay. The Sickle SCAN assay is a rapid and point-of-care device performed easily in several minutes. First, 5 μL of blood (either from the finger as depicted in Panel A or pipetted from a previously collected sample) is added to 1.0 mL of prefilled buffer solution (Panels B and C). The tube containing the sample and buffer solution is mixed well by inverting three times (Panel D) and after discarding 3 drops, 5 drops of the lysate are added to the application pad on the Sickle SCAN cartridge (Panel E). The result is often visible within 1 min, but the final result is scored after 5 min with a darkened blue band indicating the presence of each hemoglobin (Panel F).

Study design.

The study was designed to assess multiple characteristics of this POC assay and to evaluate its potential utility as a screening and diagnostic test for SCD in clinical settings. The specific objectives of this study included the following determinations: (1) sensitivity and specificity of the POC test to detect HbA, HbS, and HbC in both typical homozygous and heterozygous states; (2) accuracy in establishing the diagnosis of sickle cell disease; (3) specificity of the assay for HbA, HbS, and HbC by including samples containing many common and variant hemoglobins that might cross-react in the immunoassay; (4) sensitivity to detect low concentrations of HbA, HbS, and HbC using artificial “spiked” samples; (5) feasibility of testing DBS samples, analogous to heel stick samples from neonatal screening or finger stick samples from older children and adults; (6) stability of the POC reagents and cartridge at 37°C to simulate the climate of sub-Saharan Africa; (7) consistency of results interpretation over time; and (8) interobserver agreement of scoring and interpretation using three observers.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. For all calculations, the presence or absence of HbA, HbS, and HbC as detected on the POC assay was compared to the gold standard result obtained by CZE. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated for each individual observer and also in aggregate, such that the score by each observer was counted as a single experiment. The 95% confidence intervals for the sensitivity and specificity were calculated using the exact Clopper–Pearson method. Interobserver agreement was calculated using Fleiss’ kappa statistic.

Results

Sensitivity and specificity for the detection of HbA, HbS, and HbC

A total of 139 whole blood samples were systematically analyzed with Sickle SCAN by three independent masked clinicians and compared to CZE results as a reference. The samples had both normal and abnormal hemoglobin patterns, including sickle cell trait (HbAS), sickle cell disease (HbSS and HbSC), both homozygous and heterozygous HbC (CC and AC), and several samples from transfused sickle cell patients. As shown in Table I, the presence of HbA, HbS, and HbC was easily detected in both heterozygous and homozygous samples. Both HbS and HbC were correctly identified by all 3 observers every time they were present in a sample, except for one patient with HbSβ+-thalassemia, for which a single observer did not identify the presence of HbA. The sensitivity (99.5%) and specificity (92.5%) for the detection of HbS were excellent. There were no false-positive or false-negative results for the detection of HbC, with sensitivity and specificity of 100%. For HbA, the sensitivity (98.3%) and specificity (94.0%) were also excellent. Table II details the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for the detection of each hemoglobin band with the associated 95% confidence intervals. The table provides data for each individual observer and also in aggregate.

TABLE I.

Performance of point-of-care Sickle SCAN test

| Sample type | No. of Samples | Result by reference method | Expected Sickle SCAN pattern | No. of samples correctly scored by 3 observers | No. of samples incorrectly scored by at least 1 observer (incorrect scored result) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 38 | A or FA | A | 36 | 2 (A, S) |

| Sickle Cell Disease | 38 | ||||

| Hb SS | 21 | S or FS | S | 20 | 1 (A, S) |

| Hb SC | 11 | SC or FSC | S, C | 11 | 0 |

| Hb Sβ+-thalassemia | 1 | SA | A, S | 0 | 1 (S only) |

| Hb SD | 1 | SD | S | 0 | 1 (A, S) |

| On transfusions | 5 | SA or SDA | A, S | 4 | 1 (S only) |

| Sickle cell trait | 34 | AS or FAS | A, S | 32 | 2 (S only) |

| Hb C disease | 9 | ||||

| Hb CC | 5 | C | C | 5 | 0 |

| Hb C trait | 4 | AC | A,C | 4 | 0 |

| Hb variants | 19 | ||||

| Hb Bart’s | 4 | A, Bart’s | A | 4 | 0 |

| Hb G-Philadelphia | 3 | AG | A | 1 | 2 (A, S) |

| Hb D Trait | 3 | AD | A | 3 | 0 |

| Hb E Trait | 2 | AE | A | 2 | 0 |

| Hb Lepore | 1 | A, Lepore | A | 0 | 1 (A, S) |

| Hb Hope | 1 | A, Hope | A | I | 0 |

| Hb I-Texas | 1 | A, I | A | 0 | 1 (A, S) |

| Hb O | 1 | A, 0 | A | I | 0 |

| Hb EE | 1 | FE | No bands | 0 | 1 (A, S) |

| Thalassemia major (on transfusions) | 2 | AF | A | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 139 | 126 | 13 |

TABLE II.

Sensitivity and Specificity for the Detection of HbA, HbS, and HbC

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA | Observer 1 | 99.0 | 92.3 | 97.1 | 97.3 |

| Observer 2 | 97.0 | 94.9 | 98.0 | 92.5 | |

| Observer 3 | 99.0 | 94.9 | 98.0 | 97.4 | |

| Cumulative: | 98.3 | 94.0 | 97.7 | 95.7 | |

| (95% Cl) | (96.2–99.5) | (88.1–97.6) | (95.3–99.1) | (90.1–98.6) | |

| HbS | Observer 1 | 100 | 92.4 | 93.6 | 100 |

| Observer 2 | 98.6 | 92.4 | 93.5 | 98.4 | |

| Observer 3 | 100 | 92.5 | 93.5 | 100 | |

| Cumulative: | 99.5 | 92.5 | 93.5 | 99.5 | |

| (95% Cl) | (97.5–100) | (87.9–95.7) | (89.6–96.3) | (97.0–100) | |

| HbC | Observer 1 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Observer 2 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Observer 3 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Cumulative: | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| (95% Cl) | (92.1–100) | (99.0–100) | (92.1–100) | (99–100) |

Accuracy for the diagnosis of sickle cell disease

After determining the specificity and sensitivity to detect individual hemoglobin bands (HbA, HbS, and HbC), the POC test was next evaluated to establish the diagnosis of SCD, either homozygous HbSS or compound heterozygous HbSC disease. For the accurate diagnosis of homozygous HbSS disease, the test demonstrated a cumulative sensitivity of 98.4% (95% CI 91.5–100%) with individual observer sensitivity ranging from 95.2% to 100%. Cumulative specificity for the diagnosis of HbSS disease was 98.6% (95% CI 96.7–99.5%) with individual observer specificity ranging from 97.5% to 99.2% for each of the three observers. For the diagnosis of HbSC disease, both sensitivity and specificity were 100%. There was only one “missed” HbSS diagnosis, i.e., a false-negative result, by a single observer in the initial batch of samples, when the observer questioned the presence of a faint HbA band and scored the sample SA. The other two observers accurately identified HbSS in all 21 samples (Table I). Supporting Information, Figure 2 illustrates the aggregate results for the accurate diagnosis of the most common abnormal hemoglobin patterns.

Test performance with variant hemoglobins

In addition to HbA, HbS, and HbC, samples included several common and uncommon variant hemoglobins, in order to determine the specificity of the HbS and HbC band detection. Variant hemoglobins included Hb Bart’s, HbD-Los Angeles, HbE, HbG-Philadelphia, Hb Hope, Hb Lepore, Hb I-Texas, Hb Lepore, and HbO (Table I). HbF was present at >50% in 24 samples (including 11 newborn samples with >80% HbF), with accurate scoring for the presence of HbA, HbS, and HbC in all cases, with no obvious interference from HbF. The majority of samples were scored correctly without interference from other variant hemoglobins, but six samples were incorrectly scored by at least one observer (Table I). Two samples (Hb FE and Hb SDF) were incorrectly scored by all three observers since HbA was incorrectly identified, while two observers labeled a positive HbS band for another sample with reported HbAF 1 G-Philadelphia pattern. Other hemoglobin variants that produced incorrect results included Hb I-Texas and Hb Lepore, with a “false-positive” identification of a very faint HbS band when HbS was not present in the sample.

The likely reason for these errors was related to the fact that prior to adding the liquid sample, a faint blue line is present at each band location on the test strip (Supporting Information, Fig. 1A) and as the sample flows across the strip, the line usually fades if the hemoglobin type is not present and the faint blue line becomes nearly invisible, although a naïve observer may still visualize a very faint band when HbS is not present (Supporting Information, Fig. 1B). When hemoglobin S is actually present, the band is quite intense, a technical aspect of the test that was learned quickly after hands-on experience.

Sensitivity for low concentrations of HbA, HbS, and HbC

Spiked samples containing titrated amounts of HbA, HbS, or HbC were included in the blinded testing. Hemoglobin S was detected down to concentrations of <1% by one observer and reliably to approximately 3–4% by all three observers. Hemoglobin C was reliably detected down to concentrations of <1% by two observers and to approximately 3–4% by all three observers. These results indicate excellent sensitivity for detecting both abnormal hemoglobins critical for the diagnosis of SCD. HbA, which produces a less-intense band, was reliably detected by all three observers down to concentrations of approximately 5–10%.

Feasibility of dried blood spots

To evaluate the potential utility for analyzing DBS in a newborn screening setting, whole blood was spotted onto DBS for seven different samples. These DBS samples included all relevant hemoglobin patterns for the diagnosis of SCD, including homozygous SS and SC, heterozygous hemoglobin S and C trait, and three samples had >80% HbF. All seven DBS samples yielded clear positive bands and the correct hemoglobin patterns were accurately identified in all cases, without loss of sensitivity or specificity.

Effect of storage conditions

The manufacturer recommendations suggest that the devices and reagents be stored between 2 and 30°C, but the conditions in sub-Saharan Africa often reach temperatures above 30°C. In order to investigate the effects of high temperature, three devices (including reagents) were stored at 37°C for 1 month. After exposure to this high temperature, these devices all gave identical results to those stored at room temperature. Similarly, blood samples stored at 4°C for up to 1 month still gave accurate bands, compared to fresh samples (Supporting Information, Fig. 3).

Consistency of results over time

The Sickle SCAN assay is designed to be a POC assay with results available immediately at the time of testing, but durability of the visual result interpretation over time was also assessed. In general, the test result was clear within 1 min after application to the cartridge, but scoring was performed after 5 min per manufacturer’s recommendations to allow complete wicking of the sample and accurate scoring. Over time, the result indicator bands demonstrated some mild discoloration when left at room temperature, but the interpretation of the results remained easy to read and interpret for many days. Used devices were stored at −20°C with repeat interpretation after 4 days for 60 samples, and after 90 days for 26 samples; the scoring was identical (60/60) after 96 hr and nearly identical (25/26) after 90 days, indicating substantial stability of the results over time.

Interobserver agreement

The test demonstrated excellent interobserver agreement with a kappa value of 0.93 (z 5 33.17, P < 0.0001) based upon the final hemoglobin pattern. The kappa values for the detection of HbA, HbS, and HbC were 0.96 (z 5 19.69, P < 0.0001), 0.95 (Z 5 19.43, P < 0.0001), and 1.00 (Z 5 20.42, P < 0.0001), respectively.

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrates the ease, sensitivity, specificity, and reliability of the prototype Sickle SCAN POC device to diagnose both sickle cell trait and disease. A recently published report using the same device, performed in collaboration with the manufacturer, evaluated 137 samples and demonstrated 100% sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of all HbA, HbS, and HbC disorders [22]. In that report, however, the diagnosis of a positive or negative band was determined by scanning the assay strip, analyzing the color intensity using a custom-coded algorithm, and using preset intensity cutoffs for each band. Testing also included an additional 71 patients at the POC with known HbA, HbS, and HBC genotypes with near-perfect sensitivity and specificity for these samples [22]. Our experiments were performed simultaneous to, and without knowledge of, this recently published work. We confirm that the POC device has great promise, but our carefully designed experiments demonstrate some important differences from this recent publication. Specifically, two important differences in our report are (1) the sensitivity and specificity are very good but not perfect and (2) there is a substantial variability in the intensity of the HbA band with the potential of missing the presence of HbA. We identified several additional strengths of this POC device, including a high degree of accuracy in the presence of high HbF, using DBS samples, and in hot conditions, along with excellent interobserver agreement in result interpretation. We also identified limitations of this new assay including potential interference by abnormal hemoglobins, variable intensity of the HbA band, and a small but real learning curve for those interpreting the test.

Our data purposefully included all tested and scored samples without any “training period,” in order to report on potential errors in assay performance and interpretation of results that could be made by truly naïve and untrained observers. The observers were instructed to follow the manufacturer’s direction and score any potential bands visible at 5 min, even if faint. The scoring of individual HbA, HbS, and HbC bands did not always correlate with the actual percentages, indicating that this prototype is qualitatively accurate, but should not be used for quantitative assessments. In general, HbS and HbC bands were much stronger than the HbA band, regardless of the actual percentages present in the sample. Even a faint HbA band indicated that HbA was likely present, compared to stronger bands when either HbS or HbC was present. Importantly, however, HbS and HbC in both homozygous (disease) and heterozygous (trait) samples were accurately reported, although our findings suggest ways for improving the device and identifying clinical settings where the device may have limitations.

The results of this study are encouraging, but several limitations of the Sickle SCAN device were noted with potential areas for improvement following hands-on use. The most problematic issue was inconsistency in the intensity of the HbA band. As per the package insert, the current prototype uses polyclonal antibodies to detect each hemoglobin type. After evaluation of the POC device through these experiments, a potential area of improvement is to either improve the affinity or concentration of the HbA antibody or to use monoclonal instead of polyclonal antibodies. Our results were still encouraging and mostly accurate despite the faint HbA band, but the quality of the test would be greatly improved with a stronger and more consistent HbA signal. Since this test would be especially useful for screening neonatal samples, where the presence of a small (<10%) amount of HbA can make the difference between a disease and carrier state, this improvement would greatly improve the utility of the Sickle SCAN assay. However, even in this prototype, the presence of HbS and HbC was always indicated by a strong band and was not missed in any of our samples. Another limitation of this device was the potential cross-reactivity of some important Hb variants with the HbA band, notably HbD and HbE. The reason for this cross-reactivity is presumably retention of HbA epitopes around the Glu residue at position 6, but critically no tested variant had cross-reactivity with HbS or HbC. However, the possibility of a false-positive HbA band suggests that the appearance of HbA and HbS on the test strip may not always mean sickle cell trait. Variants such as Hb D-Los Angeles (beta 121 Glu > Gln, HBB:c.364G > C), HbE (beta 26 Glu > Lys, HBB:c.79G > A), and Hb O-Arab (beta 121 Glu > Lys, HBB:c.364G > A) that are pathological in the compound heterozygous state with HbS, but retain the HbA epitope at position 6, may be incorrectly identified as HbAS. A third potential limitation is that HbSb1-thalassemia may be difficult or impossible to differentiate from the HbAS carrier state, depending on the limits of detection for HbA. In these experiments, the strength and sensitivity of the HbA band appeared to vary with different lots of reagents and test cartridges. Finally, a fourth potential limitation is that our results were interpreted in a laboratory setting by pediatric hematologists. An important follow-up study will include evaluating the accuracy of this device when used in actual limited-resource settings by local laboratory technicians or healthcare providers.

The utility of a rapid and accurate POC diagnostic device for SCD as described here is twofold: (1) to accurately identify persons (primarily infants and young children) affected by SCD and (2) to screen large populations to identify carriers for abnormal and disease-causing hemoglobin variants such as HbS and HbC. The primary benefit of such an assay for the screening of infants and young children is that the result is accurate and available immediately after sample collection and testing, even in the newborn setting, and does not require finding persons with positive results. As a screening test for older populations, such as adolescents or young adults, this POC assay would be able to identify carriers of HbS or HbC accurately, and allow education regarding the genetic basis of SCD and the risks associated with the carrier state. These two primary potential uses of this POC assay could directly reduce the morbidity and mortality of SCD, and also could potentially decrease the number of SCD births due to improved awareness by those who carry these hemoglobin variants.

In addition to Sickle SCAN [22], there are several recently published reports of other POC assays that also may have clinical utility for identifying SCD [18–21]. One paper-based assay identifies the presence of HbS by measuring the separation of HbS from non-HbS using differential wicking in a paper matrix [18,19]. This test has the benefit of providing semiquantitative %HbS, but does not specifically identify the presence or absence of HbA, HbC, or other hemoglobin types. In addition, the time to complete this assay is reportedly 35 min, which is significantly longer than both the Sickle SCAN device and even more advanced laboratory techniques such as HPLC and CZE. A second recently described POC assay separates erythrocytes by density using aqueous multiphase systems in order to diagnose SCD [20,21]. This test is simple and rapid (12 min), but requires at least a basic centrifuge and some training. This test is able to identify HbSS accurately, but cannot differentiate HbAS from HbAA, and thus cannot identify the HbS or HbC carrier state or homozygous HbCC [20,21]. Also, because dense cells are not present in newborns with SCD due to high percentages of HbF, the density gradient device is likely not suitable for neonatal screening [20,21]. However, this visual test was recently evaluated in a clinical setting in Zambia, and demonstrated sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 60% for the diagnosis of homozygous HbSS disease [21]. In contrast to these two published POC assays, the Sickle SCAN device has the benefits of quickly identifying the presence or absence of HbA, HbS, and HbC, and yields rapid and accurate results even in high-HbF samples. Its reliability after prolonged exposure to high temperatures further suggests that it may be suitable for screening newborns, young children, or adults in hot climates for sickle cell disease and carrier states, including the compound heterozygous HbSC disease commonly found in West Africa.

Together, our analyses indicate that the Sickle SCAN POC device is simple, robust, and highly sensitive for detecting HbA, HbS, and HbC, even in very low percentages. The device has been designed as a low-cost test to be used in resource poor settings such as sub-Saharan Africa and India. The device easily and rapidly detected common hemoglobins, but was not quantitative. Specificity was excellent even in the presence of high HbF and unusual hemoglobin variants, with the possible exception of hemoglobin variants that share some cross-reactivity with HbA. The ability to obtain rapid and accurate results for both sickle cell disease and trait, using either liquid blood or dried blood spots, including those with newborn high-HbF phenotypes, suggests that this device has great potential for use in large-scale sickle cell screening programs in limited-resource settings.

It remains to be seen whether this test, with the potential for occasional inaccurate results due to rare and abnormal hemoglobin patterns, should be offered primarily as a screening tool to identify patients who need further testing by standard techniques like IEF or CZE, or can be considered a diagnostic tool that establishes an accurate Hb result at the time of testing. Since our data demonstrate that the assay reliably and easily detects the presence of pathological HbS and HbC, even in very low percentages, we believe this test could be used as a standalone diagnostic test in settings where confirmatory or advanced testing is not available. Although two-phased testing and subsequent confirmation is routine in the US and other developed countries, it may be time for a paradigm shift to think more practically at the cost-effectiveness of a single rapid and accurate diagnostic test such as Sickle SCAN, even admitting a small chance of missing rare conditions such as HbSD or HbSE disease. Future studies with POC devices should focus on such “real-world” applications of these assays, with evaluations and direct feedback from the end-users and policy-makers from limited-resource settings where the need for such testing is the greatest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Biomedomics for providing the POC test cartridges free of charge for testing, and allowing all results to be published without any prior review of the data or the written manuscript.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Modell B, Darlison M. Global epidemiology of haemoglobin disorders and derived service indicators. Bull World Health Organ 2008; 86:480–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGann PT. Sickle cell anemia: An underappreciated and unaddressed contributor to global childhood mortality. J Pediatr 2014; 165:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weatherall DJ. The inherited diseases of hemoglobin are an emerging global health burden. Blood 2010; 115:4331–4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ware RE. Is sickle cell anemia a neglected tropical disease? PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7:e2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams TN, Weatherall DJ. World distribution, population genetics, and health burden of the hemoglobinopathies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012; 2:a011692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christianson A, Howson CP. March of Dimes: Global Report on Birth Defects. New York, NY: March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, et al. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010; 115:3447–3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King L, Fraser R, Forbes M, et al. Newborn sickle cell disease screening: The Jamaican experience (1995–2006). J Med Screen 2007; 14:117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grosse SD, Odame I, Atrash HK, et al. Sickle cell disease in Africa: A neglected cause of early childhood mortality. Am J Prev Med 2011; 41: S398–S405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sickle-Cell Anaemia: Report by the Secretariat. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2006. Contract No.: A59/9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGann PT, Ferris MG, Ramamurthy U, et al. A prospective newborn screening and treatment program for sickle cell anemia in Luanda, Angola. Am J Hematol 2013; 88:984–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tshilolo L, Kafando E, Sawadogo M, et al. Neonatal screening and clinical care programmes for sickle cell disorders in sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from pilot studies. Pub Health 2008; 122:933–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tshilolo L, Aissi LM, Lukusa D, et al. Neonatal screening for sickle cell anaemia in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Experience from a pioneer project on 31 204 newborns. J Clin Pathol 2009; 62:35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odunvbun ME, Okolo AA, Rahimy CM. Newborn screening for sickle cell disease in a Nigerian hospital. Pub Health 2008; 122:1111–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahimy MC, Gangbo A, Ahouignan G, et al. Newborn screening for sickle cell disease in the Republic of Benin. J Clin Pathol 2009; 62:46–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohene-Frempong K, Oduro J, Tetteh H, et al. Screening newborns for sickle cell disease in Ghana. Pediatrics. 2008; 2008:S120–S121. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Developing a Point-of-Care Device for the Diagnosis of Sickle Cell Disease in Low Resource Settings SBIR. National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang X, Kanter J, Piety NZ, et al. A simple, rapid, low-cost diagnostic test for sickle cell disease. Lab Chip 2013; 13:1464–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piety NZ, Yang X, Lezzar D, et al. A rapid paper-based test for quantifying sickle hemoglobin in blood samples from patients with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol 2015; 90:478–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar AA, Patton MR, Hennek JW, et al. Density-based separation in multiphase systems provides a simple method to identify sickle cell disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2014; 111:14864–14869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar AA, Chunda-Liyoka C, Hennek JW, et al. Evaluation of a density-based rapid diagnostic test for sickle cell disease in a clinical setting in Zambia. PLoS One 2014; 9:e114540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanter J, Telen MJ, Hoppe C, Roberts CL, Kim JS, Yang X. Validation of a novel point of care testing device for sickle cell disease. BMC Med 2015; 13:225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.