Abstract

Mutations in the LMNA gene are associated with a wide spectrum of disease phenotypes, ranging from neuromuscular, cardiac and metabolic disorders to premature aging syndromes. Skeletal muscle involvement may present with different phenotypes: limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 1B or LMNA-related dystrophy; autosomal dominant Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy; and a congenital form of muscular dystrophy, frequently associated with early onset of arrhythmias. Heart involvement may occur as part of the muscle involvement or independently, regardless of the presence of the myopathy. Notably conduction defects and dilated cardiomyopathy may exist without a muscle disease.

This paper will focus on cardiac diseases presenting as the first manifestation of skeletal muscle hereditary disorders such as laminopathies, inspired by two large families with cardiovascular problems long followed by conventional cardiologists who did not suspect a genetic muscle disorder underlying these events. Furthermore it underlines the need for a multidisciplinary approach in these disorders and how the figure of the cardio-myo-geneticist may play a key role in facilitating the diagnostic process, and addressing the adoption of appropriate prevention measures.

Key words: laminopathies, risk stratification, genetic counselling

Introduction

Muscular dystrophies (MD) are a heterogeneous group of inherited disorders that share similar clinical features and dystrophic changes on muscle biopsy, associated with progressive weakness (1-4). Weakness may be noted at birth or develop in late adult life. Some patients manifest with myalgias, rhabdomyolysis, or only raised serum creatine kinase (CK) levels without any symptoms or signs of weakness.

Early- or childhood-onset muscular dystrophies may be associated with profound loss of muscle function affecting ambulation, posture, and cardiac and respiratory function. Late-onset muscular dystrophies may be mild and associated with slight weakness and inability to increase muscle mass (3, 4). A better understanding of the molecular bases of MD has led to more accurate definitions of the clinical features and a new classification.

Knowledge of disease-specific complications, implementation of anticipatory care, and medical advances have changed the standard of care, with an overall improvement in the clinical course, survival, and quality of life of affected people (5-9).

Muscular dystrophies can present an autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or a X-linked pattern of inheritance and can result from mutations affecting structural proteins localizable to the sarcolemma, nuclear or basement membrane, sarcomere, or non-structural enzymatic proteins (1, 2).

In recent years, cardiac involvement has been observed in a growing number of genetic muscle diseases, and considerable progress has been made in understanding the relationships between disease skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle disease (5-9). Significant advances in respiratory care have only recently unmasked cardiomyopathy as a significant cause of death in MD (10-15).

In several forms of MD, cardiac disease may even be the predominant manifestation of the underlying genetic myopathy and precede of many years the onset of skeletal muscle involvement. Unfortunately “conventional” cardiologists may be unfamiliar with these diseases due to their low incidence, while an early detection of MD-associated cardiomyopathy is of considerable importance, as a prompt institution of cardio-protective medical or supportive therapies may slow adverse cardiac remodeling and attenuate heart failure symptoms or avoid the occurrence of sudden cardiac death in these patients (16-18).

Standard and dynamic electrocardiography (ECG and ECG Holter) and echocardiography are typically advocated for screening, although very recently, cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) has shown promise in revealing early cardiac involvement when standard cardiac evaluation is still unremarkable (15-17).

This paper will focus on cardiac diseases presenting as the first manifestation of skeletal muscle hereditary disorders such as laminopathies, inspired by two large families with cardiovascular problems long followed by conventional cardiologists who did not suspect a genetic muscle disorder underlying these events.

Patients

Family 1

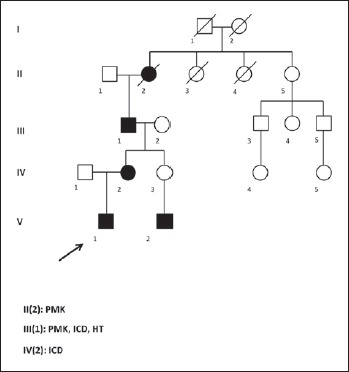

In the first family, the proband was a 15 years old young boy who underwent heart surgery for aortic coarctation. He had a bicuspid aortic valve, present in his cousin too. Family history revealed that the maternal grandfather had been implanted with a pacemaker (PMK) at the age of 50 years upgraded to an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator ICD for severe systolic dysfunction 5 years later, and received heart transplantation (HT) for severe dilated cardiomyopathy, at 60 years. Unfortunately he did not survive post-transplant complications. The great grandmother underwent PMK implantation too (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Genealogical tree of the 1st family.

During a genetic counselling, requested to investigate a possible genetic background explanining the familial occurrence of aortic valve defects, a cardiomyopathy associated genes NGS panel was performed, that unexpectedly revealed the c.673C > T (p.Arg225Ter) mutation in LMNA gene, maternally inherited. The mother, asymptomatic carrier of the mutation, underwent cardiological checks which showed a dilated cardiomyopathy and the presence of a first degree atrio-ventricular block, requiring ICD implantation.

Family 2

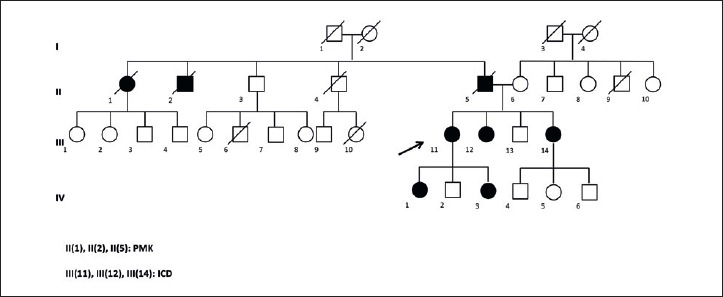

In the second family, the index case – a female aged 58y – was referred to our service in May 2016 for an apparently asymptomatic hyperCKemia (2x). An accurate reconstruction of the family history revealed a high frequency of pacemaker (4 sibling) and sudden cardiac death associated to presence of conduction anomalies in her father (Fig. 2). A diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy following an acute myocarditis had been previously made because an episode of pneumonia. As during the hospitalization a new cardiological assessment revealed a second degree atrio-ventricular block, the patient was promptly referred to our arrhythmologic Unit to be implanted with an ICD. Based on family history of multiple cardiac devices implantation, a diagnosis of laminopathy was first suspected and subsequently confirmed by LMNA gene analysis that showed the mutation c.207delG (p.Val70Ser fs X26) in both the proband and her two sisters. In one of them, previously implanted with a PMK for conduction anomalies, an upgrading to an ICD-R was necessary due to the presence of a dilated cardiomyopathy with progressive reduction of the ejection fraction (< 35%). The cardiological assessment of the third sister showed a first degree atrio-ventricular block and a not sustained ventricular tachycardia on the ECG Holter, requiring an ICD implantation.

Figure 2.

Genealogical tree of the 2nd family.

Discussion

Laminopathies or LMNA-related disorders are rare genetic diseases caused by mutations in LMNA gene, which encodes, via alternative splicing, for lamins A and C, structural proteins of the nuclear envelope. These proteins play a role in several cellular processes, and mutations in the LMNA gene are associated with a wide range of disease phenotypes, ranging from neuromuscular, cardiac and metabolic disorders to premature aging syndromes (19-27). Skeletal muscle involvement may present as autosomal dominant/recessive Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, LGMD type 1B or LMNA-related congenital muscular dystrophy (LMNA-CMD).

Lamin A/C gene mutations can be associated with cardiac diseases, usually referred to as ‘cardio-laminopathies’ mainly characterized by arrhythmic disorders and less frequently by left ventricular or biventricular dysfunction up to an overt heart failure (28-32). Heart involvement shows a high penetrance, and almost all patients after the seventh decade of life show cardiac disease, regardless of the presence of the myopathy. On the contrary, conduction tissue defects and dilated cardiomyopathy may exist without muscle disease, although subtle muscle involvement may be present and underestimated (29, 31).

Phenotypic penetrance is age-related but the expression of the disease is extremely heterogeneous, so that muscular and arrhythmic disease can be present in combination in the same patient, or in an independent way or remain hidden for a long time. Moreover, both the severity of the disease and its progression may have a marked inter- and intra-familial variability. Sudden cardiac death may be the only manifestation of the disease (31).

Conclusions

From a cardiological point of view, characterization of patients affected by “cardio-laminopathy” is of crucial importance, since clinical and prognostic implications, as well as specific management strategies, can be different, particularly with regard to prevention of sudden cardiac death (33-39).

A specific diagnosis – based on an accurate familial/personal anamnesis and/or family pedigree and genetic testing – is currently needed in patients affected by the various manifestations of these diseases. Furthermore, an appropriate risk stratification with referral to expert centres involving a multidisciplinary team for a proper decision-making is recommended.

In this context the medical geneticist can play a key role in reconstructing the family history and addressing the access to NGS sequencing or the appropriate single-gene analysis, ultimately facilitating the diagnostic process.

In addition we hope for a closer cooperation among cardiologists, experts in cardio-myopathies and geneticists to create a new professional figure, the cardio-myo-geneticist, with specific expertise and knowledge in all the diagnostic aspects of heart muscle disorders, to improve the management of patients.

Figures and tables

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The Authors declare to have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Emery AE. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet 2002;359:687-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNally EM, Pytel P. Muscle diseases: the muscular dystrophies. Annu Rev Pathol 2007;2:87-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sewry CA. Muscular dystrophies: an update on pathology and diagnosis. Acta Neuropathol 2010;120:343-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amato AA, Griggs RC. Overview of the muscular dystrophies. Handb Clin Neurol 2011;101:1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouhouch R, Elhouari T, Oukerraj L, et al. Management of cardiac involvement in neuromuscular diseases: review. Open Cardiovasc Med J 2008;2:93-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arbustini E, Di Toro A, Giuliani L, et al. Cardiac phenotypes in hereditary muscle disorders: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am CollCardiol 2018;72:2485-506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silvestri NJ, Ismail H, Zimetbaum P, et al. Cardiac involvement in the muscular dystrophies. Muscle Nerve 2018;57:707-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sommerville RB, Vincenti MG, Winborn K, et al. Diagnosis and management of adult hereditary cardio-neuromuscular disorders: a model for the multidisciplinary care of complex genetic disorders. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2017;27:51-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finsterer J, Stöllberger C, Wahbi K. Cardiomyopathy in neurological disorders. Cardiovasc Pathol 2013;22:389-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naddaf E, Milone M. Hereditary myopathies with early respiratory insufficiency in adults. Muscle Nerve 2017;56:881-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinnear W, Colt J, Watson L, et al. Long-term non-invasive ventilation in muscular dystrophy. Chron Respir Dis 2017;14:33-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawai M. Neuromuscular disease and sleep disturbance. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 2014;54:984-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simonds AK. Respiratory support for the severely handicapped child with neuromuscular disease: ethics and practicality. SeminRespir Crit Care Med 2007;28:342-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalra M, Amin RS. Pulmonary management of the patient with muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Ann 2005;34:539-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Visser M, Oliver DJ. Palliative care in neuromuscular diseases. Curr Opin Neurol 2017;30:686-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva MC, Meira ZM, Gurgel Giannetti J, et al. Myocardial delayed enhancement by magnetic resonance imaging in patients with muscular dystrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:1874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verhaert D, Richards K, Rafael-Fortney JA, et al. Cardiac involvementbin patients with muscular dystrophies: magnetic resonance imaging phenotype and genotypic considerations. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:67-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otto RK, Ferguson MR, Friedman SD. Cardiac MRI in muscular dystrophy: an overview and future directions. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2012;23:123-32, xi-xii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonne G, Di Barletta MR, Varnous S, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding lamin A/C cause autosomal dominant Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet 1999;21:285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brull A, Morales Rodriguez B, Bonne G, et al. The pathogenesis and therapies of striated muscle laminopathies. Front Physiol 2018;9:1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lattanzi G, Benedetti S, Bertini E, et al. Laminopathies: many diseases, one gene. Report of the first Italian Meeting Course on Laminopathies. Acta Myol 2011;30:138-43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Politano L, Carboni N, Madej-Pilarczyk A, et al. Advances in basic and clinical research in laminopathies. Acta Myol 2013;32:18-22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carboni N, Politano L, Floris M, et al. Overlapping syndromes in laminopathies: a meta-analysis of the reported literature. Acta Myol 2013;32:7-17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maggi L, D’Amico A, Pini A, et al. LMNA-associated myopathies: the Italian experience in a large cohort of patients. Neurology 2014;83:1634-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petillo R, D’Ambrosio P, Torella A, et al. Novel mutations in LMNA A/C gene and associated phenotypes. Acta Myol 2015;34:116-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maggi L, Carboni N, Bernasconi P. Skeletal muscle laminopathies: a review of clinical and molecular features. Cells 2016;5(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang SM, Yoon MH, Park BJ. Laminopathies; mutations on single gene and various human genetic diseases. BMB Rep 2018;51:327-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vytopil M, Benedetti S, Ricci E, et al. Mutation analysis of the lamin A/C gene (LMNA) among patients with different cardiomuscular phenotypes. J Med Genet 2003;40:e132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Captur G, Arbustini E, Bonne G, et al. Lamin and the heart. Heart 2018;104:468-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cattin ME, Muchir A, Bonne G. ‘State-of-the-heart’ of cardiac laminopathies. Curr Opin Cardiol 2013;28:297-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Captur G, Arbustini E, Syrris P, et al. Lamin mutation location predicts cardiac phenotype severity: combined analysis of the published literature. Open Heart 2018;5:e000915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narula N, Favalli V, Tarantino P, et al. Quantitative expression of the mutated lamin A/C gene in patients with cardiolaminopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1916-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peretto G, Sala S, Benedetti S, et al. Updated clinical overview on cardiac laminopathies: an electrical and mechanical disease. Nucleus 2018;9:380-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fayssoil A. Risk stratification in laminopathies and Emery Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Neurol Int 2018;10:7468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pasotti M, Klersy C, Pilotto A, et al. Long-term outcome and risk stratification in dilated cardiolaminopathies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1250-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russo V, Nigro G. ICD role in preventing sudden cardiac death in Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy with preserved myocardial function: 2013 ESC Guidelines on Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. Europace 2015;17:337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russo V, Rago A, Nigro G. Sudden cardiac death in neuromuscolar disorders: time to establish shared protocols for cardiac pacing. Int J Cardiol 2016;207:284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X, Zabell A, Koh W, et al. Lamin A/C cardiomyopathies: current understanding and novel treatment strategies. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2017;19:21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boriani G, Biagini E, Ziacchi M, et al. Cardiolaminopathies from bench to bedside: challenges in clinical decision-making with focus on arrhythmia-related outcomes. Nucleus 2018;9:442-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]