Abstract

Background and Aims:

Safe medication is an important part of anesthesia practice. Even though anesthesia practice has become safer with various patient safety initiatives, it is not completely secure from errors which can sometimes lead to devastating complications. Multiple reports on medication errors have been published; yet, there exists a lacuna regarding the quantum of these events occurring in our country or the preventive measures taken. Hence, we conducted a survey to study the occurrence of medication errors, incident reporting, and preventive measures taken by anesthesiologists in our country.

Material and Methods:

A self-reporting survey questionnaire (24 questions, 4 parts) was mailed to 9000 anesthesiologists registered in Indian Society of Anaesthesiologists via Survey Monkey Website.

Results:

A total of 978 completed surveys were returned for analysis (response rate = 9.2%). More than two-thirds (75.6%, n = 740) had experienced drug administration error and 7.7% (57) of respondents faced major morbidity and complications. Haste/Hurry (23.4%) was identified as the most common contributor to medication errors in the operation theater. Loading and double-checking of drugs before administration by concerned anesthesiologist were identified as safety measures to reduce drug errors.

Conclusion:

Majority of our respondents have experienced drug administration error at some point in their career. A small yet important proportion of these errors have caused morbidity/mortality to patients. The critical incident reporting system should be established for regular audits, an effective root cause analysis of critical events, and to propose measures to prevent the same in future.

Keywords: Anesthesiology, burden, drug administration, medication error

Introduction

Medication errors are a major cause of iatrogenic harm in health-care system and also the common reason for malpractice claim against anesthesiologists.[1,2] Anesthesia and critical care medicine are at high risk for medication errors due to the increased use of highly potent, fast-acting, narrow dose range drugs in a relatively short time period. Errors, if occurred in this situation, can lead to disastrous complication. Studies done in western countries like Canada (85%), South Africa (93.5%), and New Zealand (94%) showed high incidence of drug errors related to anesthesia.[3,4,5] It has been estimated that for every 133 anesthetics administered, there is one medication error and 1% of them cause harm to the patient.[6]

In our country, such incidents are often left undocumented or presented as case reports. To our knowledge, no studies have been done in our country to assess the magnitude of drug errors. Hence, we conducted a survey to study the occurrence of medication errors, associated factors, and incident reporting and preventive measures taken by anesthesiologist in our country.

Material and Methods

A self-reporting questionnaire was prepared to suit the objectives of this study.[3,4] The questionnaire was divided into four parts. The first part consisted questions regarding professional data and job characteristics, and the second asked their experience on medication errors and its related factors. The third part consisted of critical incident reporting and its implications, and the final part was the respondent's opinion on preventive measures for drug administration errors. A preliminary questionnaire was prepared and distributed among three senior faculties in our department (not involved in the study); they were asked to rate the question based on unipolar Likert scale (1 = not at all important, 2 = somewhat important, 3 = important, 4 = very important, 5 = extremely important). Questions which received a score of 3 and above, from all three faculties, were chosen to be included in the final survey questionnaire.[7]

After obtaining institutional ethics committee approval, the questionnaire (24 questions, 4 parts) was mailed to 9000 anesthesiologists registered in Indian Society of Anaesthesiologists via Survey Monkey Website. The survey was kept open for responses for a period of 5 months from October 2017 to February 2018. Data were recorded in Microsoft® Excel (2013) and analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics for Windows version 22, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Descriptive data are expressed as percentages and numbers.

Results

The survey questionnaire was mailed to 9000 email IDs obtained from Indian Society of Anaesthesiologists. A total of 978 completed surveys were returned for analysis (response rate = 9.2%). Majority of our responders were practicing anesthesiologist (n = 918, 93.8%) working in corporate hospitals (n = 316, 32.2%) while only 6% (60) were postgraduate students. Seven hundred and forty respondents (75.6%) admitted to having experienced drug administration error at some point in their career. Of which, 45% (324) experienced at least 1 incidence per year and 42.8% (308) experienced only once till date in their career.

The demographic details of the respondents and their practice of anesthetic drug preparation in operation theater are presented in Table 1. Experience of medication errors and its influencing factors are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic profile and practice of anesthetic drug preparation in operation theater

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Designation | |

| PG | 60 (6.1) |

| Practicing anesthesiologist | 918 (93.8) |

| Workplace | |

| Corporate hospital | 316 (32.2) |

| Government medical college | 226 (23.1) |

| Freelance practice | 188 (19.2) |

| Government hospital | 116 (11.8) |

| Private medical college | 132 (13.4) |

| Who usually loads anesthetic drugs into the syringe in your hospital? | |

| Anesthesia technician | 316 (32.3) |

| Staff nurse | 28 (2.8) |

| Junior anesthetist (resident) | 323 (33) |

| Anesthesiologist | 311 (31.7) |

| How often do you read the drug name on the syringe/ampoule/vial before administering a drug | |

| Never | 0 (0) |

| Infrequently | 47 (4.8) |

| Most of the time | 286 (29.2) |

| Always | 645 (65.9) |

| Do you/your hospital have the practice of using color-coded labels for syringes? | |

| Yes | 312 (31.9) |

| No | 666 (68.1) |

| How do you draw the drug into the syringe? | |

| Label the syringes first and then withdraw the appropriate drug | 259 (26.4) |

| Withdraw the drug and then label the syringes | 719 (73.5) |

Table 2.

Experience of medication errors in respondents and influencing factors

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Have you ever experienced drug administration error in your anesthesia practice | |

| Yes | 740 (75.6) |

| No | 238 (24.3) |

| Has any of your patients experienced major morbidity/mortality due to medication errors? | |

| Yes | 57 (7.7) |

| No | 656 (88.6) |

| Not willing to divulge | 27 (3.6) |

| What is the approximate frequency of errors? | |

| Few times a month | 17 (2.3) |

| Once a month | 7 (0.9) |

| Once every 3 months | 63 (8.7) |

| Once a year | 324 (45) |

| Only once till date | 308 (42.8) |

| When have you experienced more incidence of medication errors? | |

| Daytime | 162 (21.8) |

| Night duties | 206 (27.8) |

| Incident not related to day–night time | 372 (50.2) |

| In your perspective, what do you think is the most common reason behind not reporting drug administration errors by anesthesia personnel? | |

| Concerned person is not sure whom or where to report the incident | 188 (20.2) |

| Fear of medicolegal issues | 403 (43.3) |

| Unwillingness to reveal details | 125 (13.4) |

| Fear of judgment by colleagues | 214 (23) |

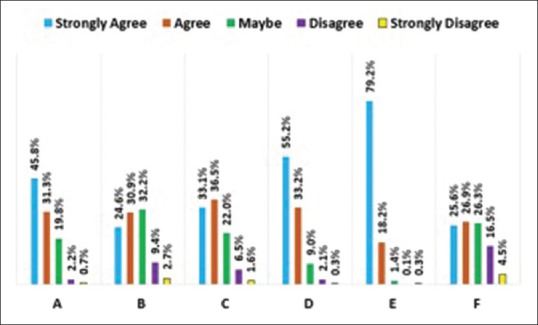

Haste/Hurry (23.4%) followed by excessive dependency on other personnel/juniors (15.6%) were identified as common contributors to medication errors in the operation theater [Figure 1]. Only 58% of them have a critical incident reporting system in their institution, which is audited every month (37.8%) for reforms and policies [Table 3]. The respondent's opinion on various strategies which can reduce drug administration errors is given in Figure 2. When asked if the color coding of syringes in operation theater would decrease drug errors, 77.1% (n = 685) “agreed” or “strongly agreed.” A similar proportion “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that loading and administration of the drugs by the concerned anesthesiologist (n = 790, 88.4%) and double-checking of medications before administration (n = 871, 97.4%) would decrease the incidence of medication error. But only half of the respondents felt that using prefilled syringes (n = 467, 52.5%) or decreasing night shifts (n = 619, 69.6%) could lower drug errors in anesthesia practice.

Figure 1.

Factors which play major roles in causing errors in drug administration

Table 3.

Critical incident reporting

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Presence critical incident reporting system | |

| Yes | 573 (58.7) |

| No | 405 (41.4) |

| If yes, how often do your institute/hospital audit incident reports? | |

| Monthly | 217 (37.8) |

| Once in 3 months | 122 (21.2) |

| Once in 6 months | 68 (11.8) |

| Once in a year | 166 (28.9) |

| If no, what is your mode of reporting a drug error? | |

| Report to a senior anesthesiologist in the hospital | 215 (53) |

| Anonymous entry of critical incidents into a computer | 48 (11.8) |

| Both | 11 (2.7) |

| None | 131 (32.3) |

| It is important to have national critical incident reporting registry for anesthesiology? | |

| Yes | 848 (93.9) |

| No | 55 (6.01) |

Figure 2.

Respondents opinion on strategies which can reduce drug errors. A = Color coding of syringes, B = reducing daytime working hours of anesthesiologist, C = reducing the number of night shifts, D = loading and administration of drugs by the concerned anesthesiologist, E = double-checking of medications before administration, F = use of prefilled syringes in operation theater

Discussion

An error is “the unintentional use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim or failure to carry out a planned action as intended.”[8] World Health Organization reported that every year millions of people are dying due to medical errors and infections associated with health-care system. About 500,000 deaths can be prevented worldwide, if a proper checklist was used.[9] Stages of medication consist of (1) requesting, (2) dispensing, (3) preparing, (4) administering, (5) documenting, and (6) monitoring, and an error can occur at any point in this process.[10] Anesthesiologists are most often involved from preparation up to the monitoring stage of medication process. Induction and maintenance phases are identified as an error-prone phase during anesthesia.[11] Studies have shown that critical incidents/errors occur more frequently during the maintenance phase of anesthesia (42%), compared to either induction (26%) or at the beginning of the surgery (17%).[12]

In our survey, more than two-third of our respondents (75.6%) have admitted to have experienced drug administration error at some point in their career. Our results are similar to studies done in various countries previously. Osler et al. audited drug errors among Canadian anesthesiologists and found that 85% of them experienced drug error or “near miss” at least once in their career with a total of 1038 adverse drug events in the study period. Though drug errors have been inconsequential, some have led to major morbidity/mortality in the patients.[3] This can cause significant psychological and emotional stress to the anesthetist involved. Our results showed that 7.7% of our respondents faced major morbidity and complications in their patients. Our data are similar to the report from the National Reporting and Learning System formed by the National Patient Safety Agency. Their audit on reports over a 2-year period showed 12,606 cases of error of which 2842 (22.5%) caused minimal harm, while 269 (2.1%) resulted in severe harm or death.[13] Though errors are common, severe or harmful errors are less prevalent or prevented by immediate action.

Drug errors can be error of commission or error of omission.[14,15] Error in commission can be wrong drug, wrong dose, wrong time, and wrong route while omission is failure to administer the drug at the appropriate time or failure to record/monitor accurately the drug administered.[16] Drugs, personnel, and equipment can all be causes for drug error. “Syringe swap” or wrong identification of a syringe was the most common error in operation theater.[3] Errors due to look-alike or sound-alike drugs, mislabel of ampoules/syringes or unlabeled syringes, have all been reported in the past. Majority of our respondents identified haste/hurry (23.4%) followed by excessive dependency on other personnel/junior (15.6%) as a factor which played major role in drug error. Haste or inattention can decrease the ability of a person to control their action, in which they may be otherwise well versed. Contrary to our finding, Cooper et al. found that maximum errors were due to inadequate experience (16%) or inadequate familiarity to equipment or device (9.3%) whereas haste and inattention each caused 5.6% of errors during anesthesia.[17] Time of the day and its correlation to drug errors is not completely proven. Our study showed that drug errors were not related to day or night duty (n = 372, 50.2%) while only one third experienced incidents during night shift. Hendey et al. showed a higher incidence of medication order errors in overnight and post-call physicians and 42% of the error was a change of dose or route,[18] whereas Erdmann et al. described higher incidence in the morning (32.7%), followed by afternoon (21.8%), and lower in the evening (16.3%).[19]

Process of drug preparation can have major influence on the occurrence of drug error in the operation theater. Formal arrangement of drug ampoules/vials in the drawers based on their groups with special attention to similar looking drugs is an important step to prevent drug swaps. The person preparing the drug for anesthesia should have adequate knowledge of each drug, its action, and possible complications. In our study, junior anesthetist/resident (33%) or anesthesia technician (32.3%) regularly prepares the drugs for anesthesia procedures. Cooper et al. showed a twofold increase in error rates by anesthesia-in-training providers compared to experienced provider.[20] Increased years of experience can lead to better familiarity with drug preparation and administration. Jain and Katiyar summarized (1) use of distinct and colored labels, (2) label on any drug ampoule or syringe should be carefully read and double checked before a drug is drawn up or injected, and (3) standardize drug preparation technique and the layout of drug workspace in OT, for an effective error reduction strategy.[21] When asked “how often they read the drug label before administering,” only 65.9% replied “always” while 29.2% said “most of the time.” Improper communication to juniors/staff or distractions in operation theater can also contribute to drug errors. Attention to medication orders and proper monitoring during drug administration is very important to prevent mishaps.

There is always something to learn from errors occurred. For a proper management of errors and prevention of future mishaps, we must have a dedicated system to identify these events, analyze the cause, and form protocols for changes.[22] Despite the need for critical incident reporting system in each institute or hospital, only half of our respondents (58.8%) have a formal reporting system. Among the respondents who did not have a reporting system, 53% reported to a senior faculty in their workplace and others did not report or register the event at all (32.3%). Although reporting an adverse event is important, there are various obstacles for a physician to do so. In our study, fear of medicolegal issues (43.3%, n = 403), fear of judgment from colleagues (23%, n = 214), and unavailability of a system or an authorized person to report (20.2% n = 188) were expressed as reasons for not reporting errors. “Culture of blame,” and a notion that an error can be a sign of incompetence or inability on the part of the physician were identified as barriers to incident reporting in various studies.[23,24] The system should not only channelize critical incident reporting but also maintain anonymity, breakdown fears or negative opinion on reporting an error, and encourage the physicians to report better.

Medication error is a preventable error and various strategies have been recommended to reduce the same. Color-coded syringes or standardized color code for different anesthetic drugs has been recommended by Institute for Safe Medication Practices and American Society for Testing and Materials. Two-third of our respondents “agreed”/“strongly agreed” that color coding could reduce errors, but only 32% use color-coded syringes in daily practice. Even though color-coded syringes have shown high speed and accuracy of drug administration, the color label is for a drug group and not a specific drug which can lead to drug mix-up within the same group.[25] Majority of our respondents considered that loading double checking prior to administration of drug by concerned anesthesiologist will help to reduce drug errors.

Apart from various recommendations by previous studies, we suggest that loading anesthetic drugs in specific size syringes, for example, anticholinergic/succinyl choline – 2 ml, vasopressors/muscle relaxants – 5 ml, induction agents/opioids – 10 ml, can also play a part to prevent errors. “Call out” the drug name and dosage, especially by trainees or technicians when they are administering the drug can reinforce correct medication. Closed-loop communication is a well-proven transmission model in ACLS and trauma care and can be useful in operation theater setup. It involves the sender and receiver, wherein the sender calls out the message and the receiver acknowledges the command and checks back. The model helps in an effective transfer of information and prevents miscommunication between team members.[26] In operation theaters where color-coded syringes are unavailable, the regular syringe containing “high alert drugs” like muscle relaxants and opioids can be flashed with a red sticker on the pistol which can demarcate them from other drugs. The user-applied drug label should be in alignment with the graduations on the syringes such that while administering the drug, one should see the drug details on the label and the volume being injected, all in one line [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Color labeling of syringe pistol containing high alert drugs

Our study has several limitations. Our sample size is small and may not represent the entire population of anesthesiologist in India. Second, the questionnaire was validated with an expert panel of only 3 members which was a small group to review and validate 24 questions. Our data are collected by self-reporting replies which may have responder bias and the recollection of events occurred in the past could have been difficult. The incidence of error was not estimated as the number of anesthetics administered is unknown.

Conclusion

Majority of the anesthesiologists in our study have experienced drug administration errors at some point in their career and a small yet important proportion of these errors caused morbidity/mortality to patients. A dedicated system to report these errors should be established both at the institutional and national level to analyze the causes and provide measures to reduce the same. Utmost vigilance and precaution should be taken at every step for a safe conduct of anesthesia.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Questionnaire

(A) Professional data:

-

I am a

-

(a)Postgraduate trainee in anesthesiology

-

(b)practicing anesthesiologist.

-

(a)

-

I have been in anesthesia practice for

-

(a)<5 years

-

(b)5–10 years

-

(c)10–15 years

-

(d)15–20 years

-

(e)20–25 years.

-

(a)

-

I work in a

-

(a)Corporate hospital

-

(b)Government medical college

-

(c)Private medical college

-

(d)Government hospital

-

(e)Freelance practice.

-

(a)

-

Which other fields do you practice apart from anesthesia services?

-

(a)No, only exclusively anesthesia practice

-

(b)Critical care

-

(c)Chronic pain management

-

(d)Teaching and academics

-

(e)Administrative responsibilities.

-

(a)

(B) Patient medication and medication error data:

-

5.

Who usually loads anesthetic drugs into the syringe in your hospital?

-

(a)Anesthesia technician

-

(b)Junior anesthetist (resident)

-

(c)Staff nurse

-

(d)Anesthesiologist (OT consultant).

-

(a)

-

6.

How often do you read the drug name on the syringe/ampoule/vial before administering a drug when you are working in your usual workplace?

-

(a)Never

-

(b)Infrequently

-

(c)Most of the time

-

(d)Always.

-

(a)

-

7.

Do you/your hospital have the practice of using color-coded labels for syringes?

-

(a)Yes

-

(b)No.

-

(a)

-

8.

How do you draw the drug into the syringe?

-

(a)Label the syringes first and then withdraw the appropriate drug

-

(b)Withdraw the drug and then label the syringes.

-

(a)

-

9.

Have you ever experienced drug administration error in your anesthesia practice till date?

-

(a)Yes

-

(b)No.

-

(a)

-

10.

If yes,

(10.1) What is the approximate frequency of errors?

-

(a)Few times a month

-

(b)Once a month

-

(c)Once every 3 months

-

(d)Once a year

-

(e)Only once till date(10.2) When have you experienced more incidences of medication errors?

-

(a)Daytime working hours

-

(b)Night duties

-

(c)Not related time of work(10.3) Have you experienced any major morbidities in your patient (cardiac arrest, permanent neurological damage, etc.) due to drug errors?

-

(a)Yes

-

(b)No

-

(c)Not willing to divulge information.

-

(a)

-

11.

In your perspective, select the factors (multiple) which you think play major roles in causing errors in drug administration?

-

(a)Inadequate experience in anesthesia practice

-

(b)Inadequate familiarity with drug/dosing

-

(c)Poor communication to peers

-

(d)Haste/Hurry

-

(e)Excessive dependency on other personnel/juniors

-

(f)Poor labeling of drug

-

(g)Fatigue/lack of sleep

-

(h)Heavy work load/long hours of work.

-

(a)

(C) Critical incident reporting:

-

12.

Does your hospital have a mandatory critical incidents reporting system?

-

(a)Yes

-

(b)No.

-

(a)

-

13.

If yes, how often does you/your department audit the critical incident registry?

-

(a)Monthly

-

(b)Once in 3 months

-

(c)Once in 6 months

-

(d)Once in a year.

-

(a)

-

14.

If No, what is your mode of reporting a drug error?

-

(a)Report to a senior anesthesiologist in the hospital

-

(b)Anonymous entry of critical incidents into a computer

-

(c)Both

-

(d)None.

-

(a)

-

15.

Do you think it is important to have national critical incident reporting registry for anesthesiology?

-

(a)Yes

-

(b)No.

-

(a)

-

16.

In your perspective, what do you think is the most common reason behind not reporting drug administration errors by an anesthesia personnel?

-

(a)Concerned person is not sure whom or where to report the incident

-

(b)Fear of medicolegal issues

-

(c)Unwillingness to reveal details

-

(d)Fear for judgment by colleagues.

-

(a)

(D) Preventive measures:

-

17.

Color coding of syringe labels reduces drug errors:

-

(a)Strongly agree

-

(b)Agree

-

(c)Maybe

-

(d)Disagree

-

(e)Strongly disagree.

-

(a)

-

18.

Reducing daytime working hours of anesthesiologists would reduce drug errors:

-

(a)Strongly agree

-

(b)Agree

-

(c)Maybe

-

(d)Disagree

-

(e)Strongly disagree.

-

(a)

-

19.

Reducing the number of night shifts would reduce drug errors:

-

(a)Strongly agree

-

(b)Agree

-

(c)Maybe

-

(d)Disagree

-

(e)Strongly disagree.

-

(a)

-

20.

Loading and administration of the drugs by the concerned anesthesiologist would reduce drug errors:

-

(a)Strongly agree

-

(b)Agree

-

(c)Maybe

-

(d)Disagree

-

(e)Strongly disagree.

-

(a)

-

21.

Double-checking of medications before administration would reduce drug errors:

-

(a)Strongly agree

-

(b)Agree

-

(c)Maybe

-

(d)Disagree

-

(e)Strongly disagree.

-

(a)

-

22.

Use of prefilled syringes in OT would reduce drug errors:

-

(a)Strongly agree

-

(b)Agree

-

(c)Maybe

-

(d)Disagree

-

(e)Strongly disagree.

-

(a)

References

- 1.Glavin RJ. Drug errors: Consequences, mechanisms, and avoidance. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:76–82. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orser BA, Byrick R. Anesthesia-related medication error: Time to take action. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:756–60. doi: 10.1007/BF03018447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orser BA, Chen RJ, Yee DA. Medication errors in anesthetic practice: A survey of 687 practitioners. Can J Anaesth. 2001;48:139–46. doi: 10.1007/BF03019726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon P, Llewellyn R, James M. Drug administration errors by South African anaesthetists – A survey. South Afr J Anaesth Analg. 2006;12:40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merry AF, Peck DJ. Anaesthetists, errors in drug administration and the law. N Z Med J. 1995;108:185–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webster CS, Merry AF, Larsson L, McGrath KA, Weller J. The frequency and nature of drug administration error during anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2001;29:494–500. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0102900508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan T, Kreuter F, Tourangeau R. Evaluating survey questions: A comparision of methods. J Official Stat. 2012;28:503–29. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Runciman WB, Merry AF, Tito F. Error, blame, and the law in health care– An antipodean perspective. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:974–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-12-200306170-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Millions of People Die Each Year Due to Medical Errors: Red Orbit. World Health Organization; 2011. Jul 22, [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nanji KC, Patel A, Shaikh S, Seger DL, Bates DW. Evaluation of perioperative medication errors and adverse drug events. Anesthesiology. 2016;124:25–34. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan FA, Hoda MQ. A prospective survey of intra-operative critical incidents in a teaching hospital in a developing country. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:177–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.01528-3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper JB, Newbower RS, Long CD, McPeek B. Preventable anesthesia mishaps: A study of human factors. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:399–406. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197812000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catchpole K, Bell MD, Johnson S. Safety in anaesthesia: A study of 12,606 reported incidents from the UK national reporting and learning system. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:340–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pronovost PJ, Thompson DA, Holzmueller CG, Lubomski LH, Morlock LL. Defining and measuring patient safety. Crit Care Clin. 2005;21:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2004.07.006. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kothari D, Gupta S, Sharma C, Kothari S. Medication error in anaesthesia and critical care: A cause for concern. Indian J Anaesth. 2010;54:187–92. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.65351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merry AF, Shipp DH, Lowinger JS. The contribution of labelling to safe medication administration in anaesthetic practice. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2011;25:145–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper L, DiGiovanni N, Schultz L, Taylor RN, Nossaman B. Human factors contributing to medication errors in anaesthesia practice. ASA. 2009:A614. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendey GW, Barth BE, Soliz T. Overnight and postcall errors in medication orders. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:629–34. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erdmann TR, Garcia JH, Loureiro ML, Monteiro MP, Brunharo GM. Profile of drug administration errors in anesthesia among anesthesiologists from Santa Catarina. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2016;66:105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper L, DiGiovanni N, Schultz L, Taylor AM, Nossaman B. Influences observed on incidence and reporting of medication errors in anesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59:562–70. doi: 10.1007/s12630-012-9696-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain RK, Katiyar S. Drug errors in anaesthesiology. Indian J Anaesth. 2009;53:539–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reason J. Human error: Models and management. BMJ. 2000;320:768–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waring JJ. Beyond blame: Cultural barriers to medical incident reporting. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1927–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brubacher JR, Hunte GS, Hamilton L, Taylor A. Barriers to and incentives for safety event reporting in emergency departments. Healthc Q. 2011;14:57–65. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2011.22491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grissinger M. Color-coded syringes for anesthesia drugs-use with care. P T. 2012;37:199–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Härgestam M, Lindkvist M, Brulin C, Jacobsson M, Hultin M. Communication in interdisciplinary teams: Exploring closed-loop communication during in situ trauma team training. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003525. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]