SUMMARY

Linker histone H1 has been correlated with transcriptional inhibition, but the mechanistic basis of the inhibition and its reversal during gene activation has remained enigmatic. We report that H1-compacted chromatin, reconstituted in vitro, blocks transcription by abrogating core histone modifications by p300 but not activator and p300 binding. Transcription from H1-bound chromatin is elicited by H1 chaperone NAP1, which is recruited in a gene-specific manner through direct interactions with activator-bound p300 that facilitate core histone acetylation (by p300) and concomitant eviction of H1 and H2A/H2B. An analysis in B cells confirms the strong dependency on NAP1-mediated H1 eviction for induction of the silent CD40 gene and further demonstrates that H1 eviction, seeded by activator-p300-NAP1 interactions, is propagated over a CTCF-demarcated region through a distinct mechanism that also involves NAP1. Our results confirm direct transcriptional inhibition by H1 and establish a gene-specific H1 eviction mechanism through an activator-p300-NAP1-H1 pathway.

Shimada et al. report that H1 eviction during transcription entails NAP1 recruitment by activator-bound p300, leading to histone acetylation and simultaneous removal of H1 and H2A/H2B. A B-cell maturation model further demonstrates that H1 eviction is seeded by activator-p300-NAP1 and continues in a wave to the nearest CTCF binding sites.

INTRODUCTION

In eukaryotes, genomic DNA is hierarchically folded into chromatin structures through interactions with histones. The fundamental unit of chromatin is the nucleosome, consisting of 146 bp of DNA wrapped almost twice around a histone octamer core (comprised of an (H3-H4)2 tetramer and two H2A-H2B dimers). A fifth histone, the linker histone H1, binds to the entry and exit points of the nucleosome, organizing an additional 20 bp of DNA and further compacting nucleosomes into higher order chromatin (Fyodorov et al., 2017; Robinson et al., 2006). As revealed by early biochemical (reviewed in (Laybourn and Kadonaga, 1991)) and genetic (Han and Grunstein, 1988) studies, chromatin formation serves to repress the intrinsic ability of the general transcription machinery (RNA polymerases and general initiation factors) to accurately transcribe cell-specific genes in the absence of bound histones or regulatory factors (Luse and Roeder, 1980; Weil et al., 1979). Transcriptional activation is then governed by gene-specific DNA-binding factors acting in conjunction with two broad groups of co-activators: one, including the Mediator and cell-specific cofactors, that facilitates direct communication between activators and the general transcription machinery (Roeder, 2003) and another, including ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers and histone modifying factors, that facilitate DNA interactions and functions of the regulatory and general transcription machineries (Li et al., 2007). That core histone modifications, which are strongly correlated with changes in transcription, are actually causal for transcription was demonstrated by biochemical analyses with chromatin templates reconstituted with mutant and pre-modified histones (An et al., 2002; An and Roeder, 2004; Tang et al., 2013). Although numerous studies have established mechanisms underlying core histone modifications and chromatin remodeling during transcription (Li et al., 2007), corresponding H1 mechanisms are less well understood.

It has long been known that H1 influences the degree of chromatin compaction and is required for formation of the “30nm fiber” (Finch and Klug, 1976; Robinson and Rhodes, 2006). This makes H1 instantly relevant to gene regulation because transcriptionally active regions have both a more open chromatin state (Gilbert et al., 2004) and lower H1 densities than transcriptionally inactive regions (Braunschweig et al., 2009; Cao et al., 2013; Izzo et al., 2013). More recently, advanced microscopic studies (Ricci et al., 2015; Ou et al., 2017) also indicated that transcriptionally inactive genomic regions contain higher H1 densities and more dense chromatin clusters than do transcriptionally inactive regions and, further, identified small, variably sized compact clusters of nucleosomes in H1-associated chromatin. Although an early genetic study of triple H1 knockout ES cells found minimal effects on transcription (Fan et al., 2005), likely due to H1 variant redundancy and compensatory increases in total H1, a later study showed a deficiency in repression of pluripotency genes during differentiation of these cells (Zhang et al., 2012). Beyond these correlations, in vitro transcription assays with reconstituted chromatin templates have provided more direct proof of a role for H1 in transcriptional repression (Laybourn and Kadonaga, 1991; Li et al., 2010). However, mechanistic details underlying the transcription inhibition remain unclear. Chromatin compaction by H1 has long been thought to repress transcription by restricting transcription factor interactions (Fyodorov et al., 2017), but whether chromatin compaction is sufficient to preclude factor association, whether other repression mechanisms are involved and how repression is reversed has not been clear.

Another key question regarding de-repression is whether H1 eviction is a prerequisite for transcription, rather than a consequence of transcription, and how it is attained. In one exemplary case, the pioneer factor FOXA was shown to evict H1 by competitive binding and thereby facilitate the binding of downstream activators that play a more direct role in transcription (Iwafuchi-Doi et al., 2016). However, the possible selectivity of this mechanism for DNA regulatory elements with FOXA sites and the tissue specificity of FOXA raise the possibility of other mechanisms for H1 eviction at non-FOXA sites and on other genes. Possibilities include other pioneer factors (Iwafuchi-Doi and Zaret, 2016), the more general HMG and PARP1 proteins that show competitive binding to nucleosomes in vitro and/or mutually exclusive genomic occupancies (Krishnakumar and Kraus, 2010; Postnikov and Bustin, 2016), and ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers and histone chaperones that have been shown to promote transcription from H1-bound templates in vitro (Li et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2015). H1 eviction has also been reported for transcriptional activation by retinoic acid and progesterone receptors, apparent pioneer factors capable of recognizing binding sites in H1-compacted chromatin (Li et al., 2010; Vicent et al., 2011). These studies have suggested an H1 eviction mechanism related to transcriptional activation, but the mechanism(s) directly responsible for H1 eviction, and whether it constitutes a discreet step prior to transcription, were not established.

Here, biochemical assays with recombinant H1-containing chromatin templates establish a direct role for H1 in transcription repression, the molecular basis of the repression, and a mechanism, through specific coactivator-H1 chaperone interactions and core histone modifications, for H1 eviction leading to activation. A complementary analysis of the activation of a silent H1-associated gene during B cell differentiation provides strong support for the physiological relevance of the model deduced from the biochemical analyses.

RESULTS

An H1-compacted chromatin structure inhibits activator-dependent transcription and associated p300-dependent histone acetylation

To investigate the mechanisms of H1-related repression and subsequent transcriptional activation of H1 chromatin, we used a model system (Robinson et al., 2008) to generate a highly compacted H1-containing “30 nm” chromatin on a DNA template containing 50 repeats of the 197 bp 601 nucleosome positioning sequence and an embedded promoter with multiple activator binding sites. (Fig. S1A and S1B). Electron micrographs showed a typical beads-on-a-string conformation for the H1-free chromatin, commensurate with an 11-nm chromatin fiber (Fig. 1A, panels a and b), whereas chromatins optimally reconstituted (Fig. S1C-E) with chicken H5 or human H1.4 (hereafter H1) appeared as small 30-40 nm diameter particles indicative of highly compacted chromatin (Fig. 1A, panels c-f).

Figure 1. H1 compaction represses chromatin transcription and acetylation.

(A) EM analysis of H1-free chromatin (a and b) and chromatin containing H5 (c and d) or H1 (e and f) at an equimolar octamer:linker ratio. Low (upper panels) and high (lower panels) magnifications with 50 nm black scale bars. (B) In vitro ChIP of FLAG:Gal4-VP16 on chromatin templates with (p601G5HM) or without (p601) Gal4 sites. FLAG:Gal4-VP16 values normalized to no FLAG:Gal4-VP16 values (n=3), mean±SD. (C) In vitro transcription assay. Additions as indicated with H1 absent or present at H1:octamer molar ratios of 0.5 and 1.0. (D) In vitro HAT assay. Free histone (100 ng, lane 1) or chromatin (100 ng, lanes 2-7) substrate with additions as indicated. Acetylation detected by autoradiography (upper panel) or by immunoblot (H3K18 or H4K16 in lower panel). See also Fig. S1.

Whereas a highly compacted chromatin, in principle, could functionally counteract transcription by hindering access of transcription factors (Fyodorov et al., 2017), an in vitro ChIP assay indicated binding of Gal4-VP16 to the promoter on both the H1-free and H1-compacted chromatins (Fig. 1B, columns 2 and 4), but not to 601 array chromatins without the Gal4-binding sites (Fig.1B, columns 6 and 8). These results indicate that a highly compacted chromatin does not necessarily block activator binding, consistent with several earlier studies (Iwafuchi-Doi and Zaret, 2016; Li et al., 2010; Vicent et al., 2011).

Subsequent in vitro transcription assays (An et al., 2002) (Fig. S1F) revealed robust Gal4-VP16- and p300-dependent transcription from the H1-free chromatin (Fig. 1C, lane 2) but almost no transcription from the fully compacted H1 chromatin (Fig. 1C, lane 6). These results are in accord with earlier studies (An and Roeder, 2004; Laybourn and Kadonaga, 1991; Li et al., 2010) and confirm a functional (inhibitory) H1 association with the template (including the non-601 repeat promoter-containing region). Similarly, HAT assays showed Gal4-VP16–dependent acetylation of H3 and H4 by p300 on H1-free chromatin (Fig. 1D, lane 3), as observed previously (An et al., 2002), but not on the H1 chromatin (Fig. 1D, lane 7). Given that H3 and H4 acetylation is essential for Gal4-VP16- and p300-mediated transcription of recombinant chromatin (An et al., 2002), it appears that the H1-mediated compaction of chromatin represses transcription, at least in part, by suppressing these acetylation events.

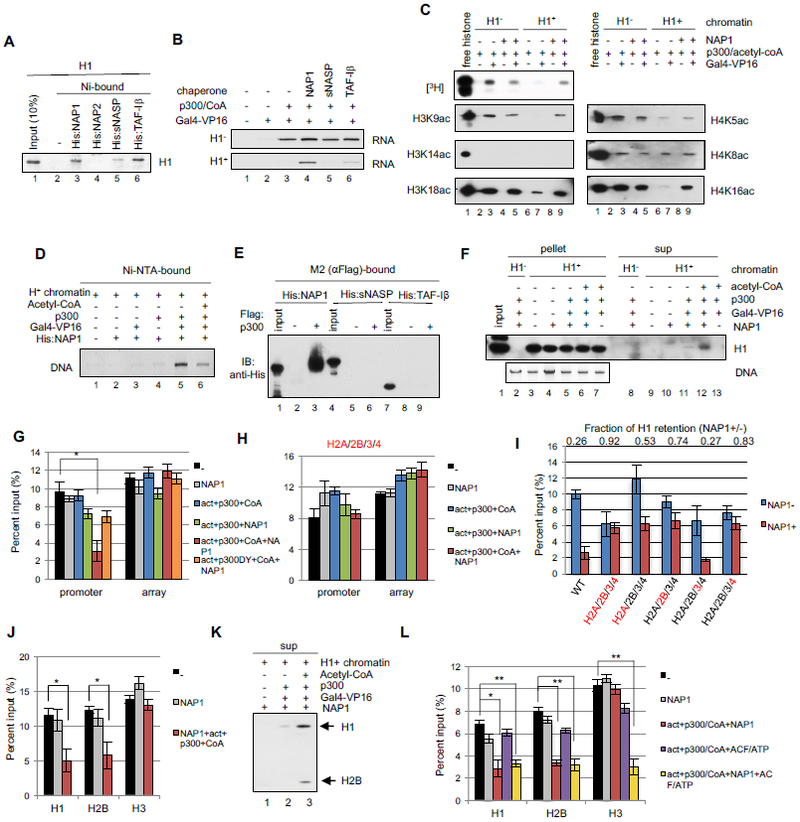

NAP1 restores core histone acetylation and transcription from H1-compacted chromatin

To restore transcription from H1-compacted chromatin, and following H1 proteomic analyses (data not shown), we focused on specific histone chaperones (NAP1, sNASP and TAF-1β) reported both to interact with linker histones and to promote changes in chromatin architecture (Flanagan and Brown, 2016). In assays with purified proteins (Fig. S2A) that showed chromatin assembly activity (Fig. S2B), and under stringent conditions, H1 bound strongly to NAP1 and TAF-1β and weakly to sNASP, but not to NAP2 (Fig. 2A). In functional assays, none of the H1 chaperones had any effect on transcription from H1-free chromatin (Fig. 2B, lanes 4-6 in upper panel). Notably, however, NAP1 markedly enhanced Gal4-VP16- and p300-dependent transcription of the H1 chromatin while TAF-1β had only a small effect and sNASP had no effect (Fig. 2B, lanes 4-6 in lower panel). Consistent with these results, NAP1 had no effect on Gal4-VP16/p300-mediated histone acetylation on H1-free chromatin but restored overall acetylation (Fig. 2C, upper panel), including acetylation of selected H3 and H4 residues (e.g., H3K9, H3K18 and H4K16), on the H1 chromatin to levels approximating those observed for H1-free chromatin (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the limited acetylation levels in both H1-free chromatin and H1 chromatin relative to free histones, as well as the activator dependence of the histone acetylation, strongly support the view that acetylation is activator-dependent and occurs in the vicinity of the activator binding sites. These results demonstrate that NAP1 facilitates transcription by restoring core histone acetylation levels in H1 chromatin.

Figure 2. NAP1 restores transcription and acetylation of H1-compacted chromatin via H1 removal.

(A) H1 binding to His-tagged H1 chaperones. Bound H1 monitored by CBB staining. (B) In vitro transcription assay with H1 chaperones. Additions as indicated with H1− (upper) and H1+ (lower) chromatin templates. (C) HAT assays with NAP1. Additions as indicated with acetylation monitored by autoradiography or immunoblot. (D) NAP1 binding to H1+ chromatin. After incubation of indicated components, the NAP1-chromatin interaction was monitored by EtBr staining of DNA bound to Ni-NTA agarose-bound His:NAP1. (E) p300-chaperone binding assays. M2-agarose beads without or with bound FLAG:p300 were incubated with His-tagged chaperones that were detected with anti-His antibody. (F) Immobilized template assay for H1 release. After incubation of H1− and H1+ chromatin templates with indicated components (at 300 mM KCl) and capture on streptavidin beads, template-bound (pellet) and unbound (sup) fractions were probed for H1 by immunoblot and for pellet DNA by EtBr. (G) In vitro ChIP assay for H1. H1+ chromatin templates were incubated with the indicated components, captured on streptavidin beads, and subjected to ChIP-qPCR with promoter or array region primers (Table S2). Signals were normalized to input. n=4, mean±SD. *p<0.001. act: Gal4-VP16; CoA: acetyl-CoA. p300DY: HAT activity defective p300 (Fig. S2D-F). (H) In vitro ChIP assay for H1. Analysis as in (G) but with mutations (Fig. S2G) in all four core histones. n=3, mean±SD. (I) In vitro ChIP for H1. Analysis as in (G) but with mutations (Fig. S2G) in individual histones (indicated in red). Reactions contained Gal4-VP16, p300, and acetyl-CoA without (blue bars) or with (red bars) NAP1. n=5, mean±SD. Fractional reduction of H1 retention with addition of NAP1 (NAP1+/−) is shown for each mutant histone chromatin at the top of the graph. (J) In vitro ChIP assay for H1, H2B and H3 release. Analysis as in (G). n=3, mean±SD, *p<0.03 (K) Immobilized template assay for H1 and H2B release. Analysis as in (F). (L) In vitro ChIP assay for H1, H2B and H3 release. Analysis as in (G) but with ACF and ATP addition. n=4, mean±SD, *p<0.005, **p<0.001. See also Figs. S2 and S3.

Activator and p300 facilitate recruitment of NAP1 to H1-compacted chromatin and subsequent H1 release is dependent on the p300 HAT activity

To further analyze the mechanism underlying NAP1-mediated transcription of H1 chromatin, we examined NAP1 interactions with H1 chromatin using an immobilized His-tagged NAP1 binding assay. When incubated alone with NAP1, the H1 chromatin (monitored by DNA) failed to bind to Ni-NTA agarose-immobilized His-NAP1 (Fig. 2D, lane 2). This result indicates that whereas NAP1 can bind to free histone octamers and to H1 (Figs. S2C and 3B below), it does not bind independently to H1 chromatin. Notably, whereas the addition of either Gal4-VP16 or p300 was without effect (Fig. 2D, lanes 3 and 4), their joint addition resulted in a strong association of NAP1 and the H1 chromatin (Fig. 2D, lane 5). These results suggest that a Gal4-VP16–dependent recruitment of p300 facilitates association of NAP1 with H1 chromatin. Interestingly, the further addition of acetyl-CoA to the reaction greatly reduced the NAP1 chromatin association (Fig. 2D, lane 6). These results suggest that NAP1 is recruited to H1 chromatin by activator and p300, but that subsequent acetylation events result in release of NAP1, potentially with H1. Notably, and in agreement with a report of NAP1 binding to p300 (Shikama et al., 2000), we observed direct binding of NAP1, but not sNASP or TAF-1β, to p300 (Fig. 2E). Together with our earlier demonstration of Gal4-VP16–mediated recruitment of p300 to H1-free chromatin (An et al., 2002), these results indicate an activator-mediated recruitment of p300 that in turn recruits NAP1 to facilitate histone acetylation and transcription of H1 chromatin.

Figure 3. NAP1 requires multiple factor interactions for transcriptional activation.

(A) NAP1 architecture and deletion mutants. N-terminal (NTD), middle (MD) and C-terminal (CTD) regions are shown as white, blue and red boxes, respectively; and dimerization and acidic domains are indicated. Purified His-NAP1 mutants (stained by CBB) are shown in the right panel. (B) Binding of H1 and core histones (octamer) to immobilized His-NAP1 mutants. Bound proteins were monitored by CBB staining. (C) Binding of His-NAP1 mutants to immobilized FLAG-p300. Bound proteins were monitored by immunoblot. (D) Gal4-VP16 and p300-dependent binding of NAP1 mutants to H1+ chromatin. After incubation of indicated components, His-NAP1-bound chromatin was monitored by EtBr staining of DNA. (E) In vitro transcription assay with mutant NAP1 proteins. Assay with H1+ chromatin and indicated components. (F) Diagram of NAP1, TAF-1 β and NAP1–TAF-1β fusion proteins. (G) Binding of H1 chaperones to immobilized FLAG-p300. His-tagged wt and hybrid H1 chaperones detected by immunoblot. (H) In vitro transcription assay with wt and hybrid H1 chaperones. Assays with indicated components. See also Fig. S4.

We next utilized an immobilized template assay to assess whether H1 is removed from H1 chromatin when it is rendered permissible for transcription. Incubation of the H1 chromatin with NAP1 alone failed to release any detectable amounts of H1 into the supernatant (Fig. 2F, lane 10), consistent with the Fig. 2D results showing that NAP1 does not associate with H1 chromatin by itself. Notably, whereas inclusion of p300 with Gal4-VP16 and NAP1 resulted in release of a small amount of H1 (Fig. 2F, lane 11), the additional inclusion of acetyl-CoA markedly increased the release of H1 (Fig. 2F, lane 12). Combined with the results of Fig. 2D, these results suggest that NAP1 is recruited by p300 to H1 chromatin and subsequently, with p300-mediated acetylation of histones, enhances removal of H1 from chromatin.

It is of note that the NAP1-released H1 represents less than 5% of total H1 initially present on the chromatin, indicating that only a limited region of the chromatin is depleted of H1 under these conditions (Fig. 2F, lane 12). To test whether H1 is selectively removed from the promoter and the proximal activator binding regions (Fig. S1A; hereafter promoter), we assessed occupancy at the promoter and 601 nucleosome array regions by in vitro ChIP assays. Notably, H1 remained bound at both promoter and array regions in the presence of Gal4-VP16, p300 and NAP1 (Fig. 2G, black versus green bars), consistent with the Fig. 2F results, whereas the-further addition of acetyl-CoA significantly reduced H1 occupancy at the promoter region relative to the array region (Fig. 2G, red bar). As a further control, a mutant p300 (p300DY) that lacks HAT activity but retains the ability to bind NAP1 (Fig. S2D-F) failed to elicit H1 release in the presence of acetyl-CoA (Fig. 2G, orange bars). These results indicate that the release of H1 (~ 5% total) is centered at the activator binding/promoter region, rather than occurring globally across the template, and is dependent on the HAT activity of p300.

NAP1-dependent removal of H1 is dependent on core histone acetylation

To identify essential p300 HAT targets for H1 removal by NAP1, we focused on core histones in view of earlier reports that core histone acetylation correlates with their NAP1-dependent release from H1-free chromatin (Ito et al., 2000; Sharma and Nyborg, 2008) and, especially, that H4 acetylation inhibits chromatin condensation (Robinson et al., 2008; Shogren-Knaak et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2017). We first assembled chromatin templates with combinations of wt and core histones bearing K to R mutations in histone tail acetylation sites (Fig. S2G) and monitored compaction by native gel electrophoresis (Fig. S2H). Notably, the various wt and mutant templates showed comparable mobilities, indicating that the mutations do not generally affect formation of H1 compacted chromatin. However, and importantly, in vitro ChIP assays showed that NAP1 could not remove H1 from chromatin with acetylation site mutations in all four core histones (Fig, 2H), suggesting that acetylation of tail lysines is essential for H1 removal by NAP1. Next, to identify individual histone acetylation events important for H1 removal, we analyzed chromatin templates with mutations only in individual histones. Notably, independent mutations in H4 (83% H1 retention) and H2B (74% H1 retention) were nearly as effective as mutations in all core histones (92% retention) in preventing H1 removal, while H2A and H3 mutations showed lesser (H2A) or no (H3) effects (Fig. 2I). These results, indicating key roles for H4 and H2B acetylation in H1 removal, are consistent with previous reports that acetylation of H2B and H4 regulates compaction of nucleosomal arrays containing (Robinson et al., 2008) or lacking (Dorigo et al., 2003; Shogren-Knaak et al., 2006; Wang and Hayes, 2008) H1.

NAP1 mediates dissociation of H2A/H2B and H1, whereas subsequent dissociation of H3/H4 is facilitated by an ATP-dependent remodeling factor

Because the H2A/H2B chaperone activity of NAP1 (Park et al., 2005) is facilitated by p300, we conducted in vitro ChIP assays to assess whether core histones are also released from the promoter (Fig. S1A) along with H1. Indeed, under comparable conditions H1 and H2A/H2B dimers (monitored through H2B) were lost from the promoter at comparable levels (Fig. 2J) as further evidenced by detection in the supernatant (Fig. 2K). It is likely that H1 and H2A/H2B bind to NAP1 simultaneously since they bind to NAP1 through distinct domains (Fig. 3B below). Notably, under the minimal conditions that elicited H2A/H2B removal, the levels of H3/H4 (monitored through H3) remained unchanged at the promoter (Fig. 2J), in agreement with the reported preferential binding of NAP1 to H2A/2B relative to H3/H4 (Park et al., 2005). In further analyses, the ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler ACF, which was previously implicated in activator/p300 dependent histone acetylation (Ito et al., 2000; Sharma and Nyborg, 2008) and transcription (An et al., 2002) of chromatin templates, as well as in nucleosome movements in H1-containing nucleosome arrays (Maier et al., 2008), was found to release H3/H4 (Fig. 2L, yellow bar). Similar results were observed with SWI/SNF, which has also been implicated in transcription of H1 chromatin (Li et al., 2010; Vicent et al., 2011) (Fig. S3). These results lead to the definition of an ordered pathway for H1 and core histone removal at the activator binding/promoter regions and, together with the results of Figs. 2H and 2I, suggest that H2B and H4 acetylation may facilitate dissociation, respectively, of the H2A-H2B dimers and the (H3-H4)2 tetramer.

NAP1 requires multiple interactions with histones and p300 for transcriptional activation of H1-compacted chromatin

Although NAP1 can bind to the histone octamer, H1 and p300 (Fig. 2, Fig.S2 and (Asahara et al., 2002)), the roles for these different interactions remain unknown -- especially in the context of chromatin disassembly. Based on its three-dimensional structure (Park and Luger, 2006), NAP1 is broadly divided into a non-conserved N-terminal extension region (NTD) composed of three α-helices that mediate dimerization, a middle domain (MD), and an acidic C-terminal domain (CTD) that is the putative histone binding region (Fig. 3A). Binding assays with purified NAP1 deletion mutants (Fig. 3A) indicated (i) that the MD is the binding domain for H1 (Fig. 3B, upper panel), (ii) that the CTD, with some contribution from the MD, is indeed the major octamer binding site (Fig. 3B, lower panel) and (iii) that the NTD, but not the MD and CTD domains, binds to p300 (Fig. 3C). These results, indicating distinct interaction domains within NAP1, raise the possibility that NAP1 can bind simultaneously to H1, histone octamer and p300 and support our observation (Fig. 2J and K) that NAP1 facilitates the joint removal of H1 and H2A/H2B from chromatin.

We next utilized the NAP1 mutants to assess the NAP1 domain(s) required for NAP1 recruitment to chromatin and for NAP1 functions in H1-removal, histone acetylation and transcription. With respect to NAP1 recruitment, NAP1(1-312), which can bind to p300 and to H1, bound chromatin in the presence of Gal4-VP16 and p300 (Fig. 3D, lane 7). However, NAP1(160-312) and NAP1(160-392), which bind, respectively, to H1 and H1 plus histone octamer, but not to p300, showed no binding to H1 chromatin under the same conditions (Fig. 3D, lanes 9 and 11). These results indicate that NAP1 binding to p300 (and possibly H1), but not to H1 and histone octamer, is required for NAP1 recruitment to chromatin. With respect to NAP1 functions on the H1 chromatin template in conjunction with Gal4-VP16 and p300, none of the NAP1 mutants, including the NAP1(1-312) mutant that binds both p300 and H1, showed any of the normal NAP1-dependent core histone acetylation (Fig. S4A), H1 dissociation (Fig. S4B) or transcription activities (Fig. 3E, lanes 6, 8 and 10). Our results overall suggest that NAP1 function in histone octamer acetylation/dissociation, H1 dissociation, and transcription requires interactions with at least three factors (p300, H1 and octamer) -- with an initial recruitment of NAP1 being mediated by a direct interaction with activator-bound p300.

Our mapping of the p300 interaction site to the N-terminus of NAP1 suggested that this non-conserved domain could be the basis for selectivity of NAP1, relative to sNASP and the structurally related TAF-1β (Fig. 3F), for strong p300 interactions and associated functions. In support of this hypothesis, fusion of the non-conserved N-terminal NAP1 fragment to TAF-1β conferred both p300 binding and transcriptional activity on H1 chromatin to TAF-1β (Fig. 3G and H).

Correlations of H1 loss and p300 and NAP1 recruitment with gene induction in a B-cell differentiation model

To gain support for the physiological relevance of our in vitro model for activation of H1-repressed genes, we utilized human leukemic 697 cells that can be induced to differentiate from the pre-B to mature B-cell stage by TPA (LeBien, 2000). We first categorized gene expression patterns into inducible, constitutively active, and constitutively silent based on RNA-seq analysis before and after TPA treatment (Fig. 4A and Table S1). Most of the 492 inducible genes were mature-B cell stage-specific genes (Table S1) that included the dramatically (>100-fold) induced MS4A1 (CD20) and CD40 genes (Figs. 4B and S5A). Analyses of H1 occupancy on promoter regions of selected genes by ChIP-qPCR (Figs. 4C and 4D) revealed significant TPA-induced decreases in the H1 levels on the inducible genes (including CD40 and MS4A1), but no changes in the H1 levels on the constitutively silent genes (high H1) or the constitutively active genes (low H1). These strong correlations of H1 presence with repression and H1 loss with activation suggest an important role for H1 in gene regulation during B-cell differentiation.

Figure 4. Linker histone H1 localization is correlated with gene expression during B cell differentiation.

(A-F) Analyses in 697 cells. (A) RNA-seq analysis without (grey bars) or with (red bars) TPA treatment. Numbers of inducible, constitutively active, and constitutively silent genes are based on RPKMs (Table S1). Values are represented as mean ± SD. (B) RT-qPCR analysis of selected genes without (grey bars) or with (red bars) TPA treatment. Signals were normalized to the HPRT mRNA level. n=4, mean±SD. (C) ChIP-qPCR for H1 on select genes without (grey bars) or with (red bars) TPA treatment. n=3, mean±SD. (D) Average of ChIP-qPCR results based on data in (C). mean±SD, *P<0.001. (E) ChIP-qPCR assays following TPA treatment. Assays at the CD40 promoter were performed at the indicated times with antibodies to NF-κB/p65, p300, HA (for FLAG-HA:NAP1), H1, acetyl-H4, or RNAPII. n=3, mean±SD. (F) RT-qPCR analysis of CD40 mRNA following TPA treatment. (G) In vitro transcription of H1− and H1+ chromatin templates containing the native human CD40 promoter with indicated components. The template structure is also shown. See also Fig. S5.

Given our demonstration of the role of activators, p300 and NAP1, as well as core histone acetylation, in the in vitro activation of an H1 chromatin template, we analyzed occupancy of these factors on the CD40 promoter/proximal enhancer region (hereafter promoter) following TPA-induced B-cell differentiation. One of the known CD40 activators (NF-κB p65) and p300 were recruited to the CD40 promoter after 15 min and remained bound to the promoter thereafter (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, NAP1 occupancy reached a peak at 30 min and decreased immediately thereafter (Fig. 4E), whereas H1 occupancy decreased by 60-80% at 45min, coincident with the NAP1 decrease, and remained at a low level thereafter (Fig. 4E). H4 acetylation showed a significant increase at 15 min, coincident with the earliest increase in p300, but continued to increase thereafter (Fig. 4E). RNA polymerase II (Fig. 4E) and mRNA accumulation (Fig. 4F) showed small but significant increases by 60 min and larger (>5-fold) increases only after several hours. Notably, the prior recruitment of p300 and the coincident release of H1 and the transiently bound NAP1 support the in vitro model.

In a further exploration of the role of NAP1 in CD40 activation, we analyzed transcription in vitro from H1-free and H1 chromatin templates containing the natural CD40 promoter (−530 to −3) with three NF-κB and two SP1 binding sites (Fig. 4G upper). These factors synergistically activate transcription from the CD40 promoter in a DNA template-based assay (Fig. S5B) and, in the case of NF-κB, interact directly with p300 (Fig. S5C) to recruit NAP1 to the H1 chromatin together with p300 (Fig. S5D, lane 4). As anticipated, NF-κB/SP1 and p300 activated transcription from the H1-free chromatin template equally well in the presence or absence of NAP1 (Fig. 4G, upper panel). In contrast, transcription from the H1 chromatin was completely dependent upon NAP1 as well as NF-κB/SP1 and p300 (Fig. 4G, lower panel). A further in vitro ChIP-qPCR analysis revealed that H1 removal is similarly dependent upon NAP1, NF-κB/SP1, p300 and acetyl-CoA (Fig. S5E). These results strongly support the idea that the biochemically defined activator→p300→NAP1→H1 model for transcription activation of H1-repressed genes initiates CD40 induction in vivo.

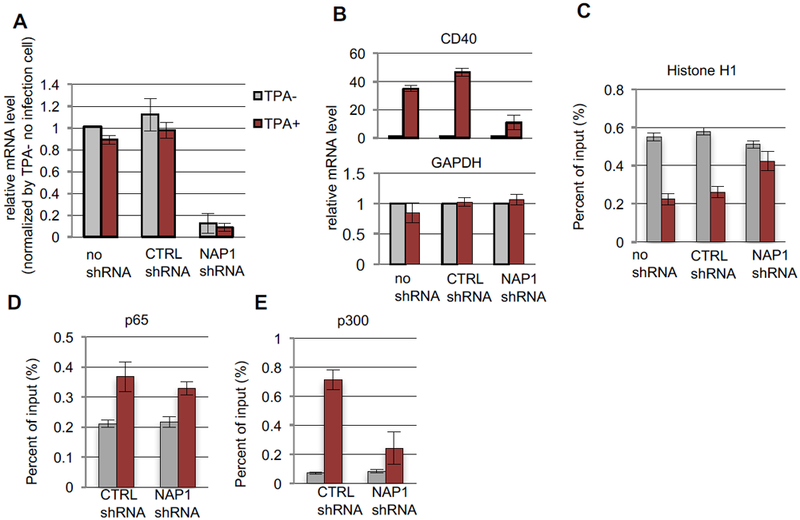

NAP1 disruption inhibits H1 removal and TPA-induced CD40 expression

To further confirm the key role of NAP1 in the cellular activation of CD40 in H1 chromatin, we used an shRNA to deplete NAP1 in 697 cells prior to TPA treatment (Fig. 5A). NAP1 depletion had no effect on expression of the active GAPDH gene that lacks H1 (Fig. 5B, lower panel) but dramatically reduced (by 80%) CD40 expression (Fig. 5B, upper panel) and, as well, significantly inhibited H1 eviction (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, H1 occupancy prior to TPA treatment was unchanged in NAP1 knockdown cells (Fig. 5C), suggesting that NAP1 may function mainly in H1 dissociation, rather than H1 association. While without any effect on p65 occupancy (Fig. 5D), NAP1 depletion did result in reduced p300 occupancy at the promoter (Fig. 5E). Thus, once recruited by activators in the cell, NAP1 and p300 appear to bind to the chromatin cooperatively, while the absence of NAP1 does not influence the binding of the activator to chromatin. This result is consistent with our earlier observation (Fig.1) that H1 does not preclude activator binding to chromatin. As expected, the knockdown of p65 precluded CD40 induction (Fig. S6A-C), efficient p300 recruitment and H1 removal (Fig. S6D, E). These results suggest that activators can directly bind chromatin for subsequent recruitment of p300 and NAP1 to facilitate H1 dissociation.

Figure 5. NAP1 depletion affects H1 loss and induction of the CD40 gene.

697 cells were either not transduced (no shRNA) or transduced with scramble (CTRL) or NAP1 shRNAs and treated without (gray bars) or with (red bars) TPA. (A) Knockdown of NAP1 mRNA. RT-qPCR values normalized to the no transfection/no TPA value. n=3, mean±SD. (B) CD40 (upper) and GAPDH (lower) mRNA levels n=3, mean±SD. (C-E) ChlP-qPCR assays on the CD40 promoter. n=3, mean±SD. Standard assays employed anti-H1 (C), anti-p65 (D) and anti-p300 (E) antibodies. See also Fig. S6.

NAP1 localization and H1 eviction spread bi-directionally from the NF-κB binding site in CD40

To better characterize H1 eviction during gene activation, we analyzed the extent of H1 eviction and core histone modifications (H4 acetylation) on the CD40 locus at different time points after TPA treatment. ChIP assays showed that at 24 hrs H1 was evicted from the entire CD40 locus, including the gene body and the upstream non-coding region (Fig. 6A upper panel and Fig. S7), whereas H4 acetylation was constrained to the NF-κB binding site near the promoter region (Fig. 6A lower panel). Interestingly, H1 eviction was initiated at the NF-κB binding site in the CD40 promoter region within 30 min after TPA-treatment (Fig. 6B, green line) and then extended to both the upstream non-coding and downstream coding regions within one hour (Fig. 6B, orange and red lines). Furthermore, a ChIP assay showed that NAP1 recruitment begins at the NF-κB binding site in the CD40 promoter after 15-30 min of TPA-treatment and then spreads to regions upstream and downstream of the NF-κB binding site (Fig. 6C). The temporal expansion of NAP1 binding, which may be transient, correlates well with the loss of H1 from these regions. These observations strongly suggest that after the initial NAP1 recruitment and subsequent p300-dependent H1 eviction at the activator binding site, H1 eviction spreads to the entire locus through a distinct mechanism that involves NAP1 but is potentially independent of p300 or p300-mediated acetylation.

Figure 6. NAP1 moves from both sides of the CD40 promoter and expands the H1-free region following TPA-induced transcription.

(A) H1 (upper panel) and H4ac (lower panel) occupancies on the CD40 locus. ChIP-qPCR in 697 cells. Primer positions (X-axis) and H1 and H4ac occupancies (Y-axis) are shown as symbols in gray (no TPA) or red (24 hr TPA). Gene positions are shown at the bottom and numbers are averages from two independent experiments. (B) Temporal spreading of H1 loss at the NCOA5-CD40 locus after TPA treatment. ChIP-qPCR for H1 with the X-axis indicating primer positions. (C) Temporal induction of NAP1 association and spreading at the CD40 locus after TPA treatment. ChIP-qPCR for FLAG-HA-NAP1 on CD40. X-axis indicates time after TPA and numbers are averages from two independent experiments. Primer sites (red arrows) and promoter NF-kB/SP1 sites on CD40 are shown at the top. (D) Gene expression at the CD40 locus after TPA treatment. Intergenic distances are shown at the top and mRNA levels (RT-qPCR) at the bottom. n=3, mean±SD. (E) H1 occupancy at the CD40 locus after TPA treatment. Results of ChIP-qPCR without (grey) or with (red) TPA. n=3, mean±SD. (F) CTCF binding sites at the CD40 locus. ChIP-seq with (lower) and without (upper) TPA treatment. (G) CTCF knockdown. mRNA levels (RT-qPCR) are shown for cells transduced with no, scrambled (CTRL) or CTCF shRNAs. (H) H1 loss at the CD40 locus after CTCF knockdown. ChIP-qPCR for cells transduced with scrambled (scr) or CTCF shRNAs with or without TPA treatment. Symbols indicate H1 values on the y-axis and primer positions on the x-axis relative to the NCOA5 and CD40 genes at the bottom. (I) CD40 mRNA levels following CTCF knockdown. RT-qPCR assays in cells transduced with scrambled (CTRL) or CTCF shRNAs with or without TPA treatment. n=3 mean ± SD See also Fig. S7.

We next focused on the genomic regions surrounding the CD40 locus to assess the extent of the wave of H1 eviction. In contrast to the TPA-inducible CD40 gene, the upstream NCOA5 gene is constitutively active with a low level of H1 that is unchanged by TPA treatment and the downstream CDH22 gene is constitutively silent with a high level of H1 that also is unchanged by TPA treatment (Figs. 6D and 6E). Thus, TPA-induced H1 eviction is constrained to the CD40 locus (Fig. 6A and Fig. S7).

As a growing number of reports have implicated CTCF in the establishment of distinct chromosomal domains (Denker and de Laat, 2016; Merkenschlager and Nora, 2016), we hypothesized that H1 eviction might be regulated, at least in part, by chromatin boundaries demarcated by CTCF. Consistent with this idea, a ChIP-seq analysis revealed CTCF binding sites between NCOA5, CD40, and CDH22 loci (Fig. 6F) that largely coincide with the borders of H1 eviction (Fig. S7). In a further test of our hypothesis, CTCF knockdown (Fig. 6G) in the absence of TPA treatment reduced H1 occupancy at the CD40 locus to a (low) level comparable to that of the NCOA5 locus and to that of the CD40 locus after TPA treatment (Fig. 6H). Notably, and whereas CTCF knockdown did lead to a modest induction of CD40 expression, full induction was observed only after TPA treatment (Fig. 6I). These results implicate CTCF in maintaining barriers to H1 eviction mechanisms at the CD40 locus and, further, show that H1 eviction is insufficient for normal activation of CD40.

DISCUSSION

Although transcriptional inhibition by linker histone H1 is a well-studied phenomenon, how H1 imposes its transcriptional inhibition and, especially, how it is evicted during transcription has been unclear. Factors previously implicated in H1 eviction, such as HMG proteins, PARP1 and FOXA, were reported to compete with H1 for binding to nucleosomes (Iwafuchi-Doi et al., 2016; Krishnakumar and Kraus, 2010; Postnikov and Bustin, 2016). These observations suggested that H1 eviction is a prerequisite for, but potentially disconnected from, the actual transcriptional functions of gene-specific activators. Related, with respect to the need for gene-specific H1 removal in cells, it has not been clear whether, in general, H1 can be actively evicted as part of an integral mechanistic step in gene-specific transcription activation. Here, through biochemical assays with recombinant chromatin templates, we elucidate a mechanistic basis of H1 repression and demonstrate that H1, and subsequently core histones, are indeed actively evicted by the collective action of an activator, the acetyltransferase p300 and histone chaperone NAP1. The corresponding model is presented in Figure 7 and, along with results establishing physiological relevance, discussed further below.

Figure 7.

Model for transcriptional activation of H1-compacted chromatin by the activator→p300→NAP1→H1 pathway. The model depicts only the initial promoter-associated H1 eviction, chromatin modification and transcription events, and not the subsequent spreading of H1 loss by a complementary mechanism (see Discussion for details). ACT, activator; Ac, acetylated histone lysines.

Linker histone inhibits transcription through inhibition of p300 acetylation

Our studies utilized the H1.4 variant based both on its high affinity for nucleosomes (relative to other H1 variants) and ability to effectively compact chromatin in vitro (Clausell et al., 2009) and on correlations of chromatin occupancy with gene repression (Braunschweig et al., 2009; Izzo et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2012). The compaction of nucleosomal arrays, generating circa 30nm particles, blocked activator/p300-dependent transcription, as reported earlier (Laybourn and Kadonaga, 1991; Li et al., 2010). Notably, but possibly reflective of multiple binding sites, the H1-compacted chromatin was still permissive for activator and p300 binding (as also seen in vivo for NF-κB, below). However, core histone acetylation by activator-bound p300, both globally and at specific H3 and H4 sites, was selectively blocked in H1 chromatin relative to H1-free chromatin, consistent with reports of H1 inhibition of other acetytransferase activities on nucleosomal substrates (Herrera et al., 2000; Stutzer et al., 2016). Since H3 and H4 acetylation are jointly required for transcription in this assay with H1-free templates (An et al., 2002), our data strongly suggest that the transcriptional inhibition by H1 is achieved by blocking chromatin remodeling (chiefly, core histone acetylation), rather than by blocking (co)factor binding to chromatin. Our demonstration that CD40 transcription in B cells is abrogated upon NAP1 knockdown, despite recruitment of cognate activator NF-κB, further demonstrates that H1 can pose a significant barrier to transcription without affecting activator accessibility and that subsequent transcriptional activation requires active removal of H1 dependent on p300 and NAP1.

It also is noteworthy that H1 removal is reciprocally dependent on acetylation of core histones H4 and H2B. This result is consistent with our previous demonstration that the H4 tail is essential for H1-dependent chromatin compaction and that H4K16 acetylation inhibits this compaction (Robinson et al., 2008). Since the profound effect of H4K16 acetylation cannot be explained by simple charge neutralization, it has been suggested that it may cause conformational changes within the H4 tail that lead to disruption of inter-nucleosomal interactions important for chromatin folding (Robinson et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2017).

Interaction with p300 determines the specificity of H1 chaperones in H1 eviction and provides a basis for activated gene-specific H1 removal

Several H1 chaperones have been identified previously (Flanagan et al., 2016) and also implicated in transcriptional regulation (Kadota and Nagata, 2014; Zhang et al., 2015). Among the well-documented H1 chaperones NAP1, NAP2, TAF1-β, and NASP, our analyses established the unique ability of NAP1 to promote robust H1 eviction in an activator- and p300-dependent fashion and, further, identified the non-conserved NAP1 N-terminus as the mechanistic basis for the chaperone specificity. Although NAP1 has been described mainly as a chaperone for core histones H2A/H2B (Park et al., 2005), its complementary function as an H1 chaperone is well documented (Mazurkiewicz et al., 2006). On a cautionary note, NAP1 has been shown to deposit and remove H1 non-specifically from chromatin in vitro depending on its concentration (Zhang et al., 2015). We also observed global removal of H1 from chromatin at a high (0.15μM) NAP1 concentration but, importantly, found that the direct p300 interaction is critical for achieving H1 eviction specifically at activator-bound promoters under a low, more physiologically relevant, NAP1 concentration. Most importantly, this ability of NAP1 to interact with p300 through the non-conserved N-terminus gives NAP1 the unique ability, among various H1 chaperones, to remove H1 in an activator-dependent manner. This in turn provides a clear basis for the selective removal of H1 at active gene loci.

Linker histone eviction may be directly linked to core histone modifications

Core histone acetylation by p300 is a well-studied initial step in activator-dependent transcription that facilitates nucleosome disruption (Ito et al., 2000; Sharma and Nyborg, 2008) and is essential for pre-initiation complex assembly on the promoter (An et al., 2002). Our observation that p300 directly recruits NAP1, and that p300-mediated acetylation of H4 and H2B is critical for H1 eviction, suggested that the p300/NAP1-dependent H1 eviction may also be linked to core histone modifications associated with nucleosome disruption. Consistent with this possibility, and the dual function of NAP1 as a chaperone for both H1 and the H2A-H2B dimer (Mazurkiewicz et al., 2006), we demonstrated (i) distinct H1, H2A/H2B, and p300 binding domains within NAP1, raising the possibility that NAP1 can bind simultaneously to these components, (ii) simultaneous p300/NAP1-mediated loss of H1 and H2A-H2B without further addition of other factors, and (iii) subsequent H3/H4 loss in the presence of an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler. These observations support a model (Figure 7) in which H1 eviction by p300-NAP1 occurs concomitantly with H2A-H2B loss from the nucleosome, and thus facilitates subsequent H3/H4 acetylation by p300 and ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler-dependent loss of H3/ and H4.

Different modes of linker histone eviction on a developmentally activated gene

The physiological significance of our biochemically established activator→p300→NAP1→H1 interaction pathway for H1 eviction was validated in a B cell differentiation model in which TPA-induced CD40 gene activation was shown (i) to involve coincident recruitment of NF-κB, p300 and NAP1 followed by coincident loss of NAP1 with H1 and (ii) to be dependent on NAP1. Consistent with these results, NF-κB–mediated in vitro transcription of an H1-compacted chromatin template containing the CD40 promoter by NF-κB was dependent upon both p300 and NAP1. Thus, these results establish an activator, p300 and NAP1 requirement for H1 eviction for a specific gene activation event. They further indicate that other factors (e.g., FOXA, HMGs, PARP1) variably implicated in H1 eviction in other assays (Fyodorov et al., 2017) cannot substitute for the p300-NAP1 pathway -- although they might well contribute to it during later steps. We also observed that H1 eviction on the CD40 gene originates at the NF-κB binding site and continues to spread, coincident with NAP1 recruitment, both upstream and downstream. This observation suggests that H1 eviction upon gene activation is achieved through at least two modes: an initial step in which activator-p300-NAP1 interactions evict H1 from the activator binding region and a second, currently undefined, step that propagates a wave of H1 eviction throughout the entire gene locus and that may involve NAP1 recruitment through other mechanisms. In this regard, we previously showed that a 30% level of H4K16 acetylation was sufficient to completely counter H1-dependent chromatin compaction (Robinson et al., 2008) -- raising the possibility of a similar type of cooperativity in the propagation of H1 eviction following local seeding events through the activator-p300-NAP1 pathway and driven by the disruption of inter-nucleosomal interactions (see above). It also appears that the wave of H1 eviction ends at the nearest CTCF-bound sites, consistent with reports of CTCF as boundary elements that segment chromatin into distinct structural and functional units (Denker and de Laat, 2016; Merkenschlager and Nora, 2016).

Interestingly, knockdown of CTCF led to H1 depletion from the CD40 locus in the absence of the inducer, likely reflecting encroachment of the H1-free region of the neighboring NCoA5 locus and supporting a model in which different modes of H1 eviction establish and maintain the H1 landscapes unique to each cell type. Within such a model, H1 eviction through activator-p300-NAP1-H1 interactions appears to represent a primary (“pioneer”) mechanism for the signal- and gene-specific acute H1 eviction, while H1 eviction by an alternate mechanism (e.g., by HMG or PARP1 competition) may facilitate maintenance of a low H1 density at transcriptionally active loci. Notably, CTCF knockdown resulted in a modest (but significant) de-repression of CD40 gene in the absence of inducer, although the full-scale activation was still dependent on the inducer. These results suggest a multi-step mechanism for CD40 activation involving H1 removal/chromatin decompaction and subsequent transcriptional activation. The results also are consistent with recent reports that CTCF degradation has minimal immediate effect on transcription (Rao et al., 2017; Zuin et al., 2014) and that H1 loss can have significant effects on chromosome organization without major transcriptional changes (Geeven et al., 2015).

Implications and future studies

Our study has defined a fundamental pathway for H1 removal in which gene specificity is governed by gene-specific activators that ultimately, through an associated coactivator, lead to essential core histone acetylation events. However, it remains possible that this pathway can be facilitated by more general factors (e.g., HMGs and PARP1) implicated in H1 removal or (at least for some genes) by pioneer factors that may be necessary for gene-specific activator binding (Iwafuchi-Doi and Zaret, 2016). Other important questions related to this mechanism are its specificity for different classes of genes, its specificity for the various linker histone variants with different nucleosome affinities (Clausell et al., 2009), and potential effects of (or requirements for) the various linker histone modifications (Fyodorov et al., 2017). In addition, there are intriguing reports of (i) positive transcription functions of linker histones following specific covalent modification (Kamieniarz et al., 2012) or interactions with other transcription (co)factors (Kim et al., 2013), (ii) stabilizing effects of specific core histone modifications on H1 binding (Kim et al., 2015) and (iii) functions of H1 in recruitment of diverse epigenetic factors (Fyodorov et al., 2017). The biochemical assays that we have described, and which can be extended to a fully defined system (An et al., 2002; Guermah et al., 2009), provide a powerful approach to address such questions and associated mechanisms of transcriptional regulation.

STAR METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Robert Roeder (roeder@rockefeller.edu)

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Protein Purification

E.coli BL21(DE3)pLysS cells were transformed with expression vectors and grown in LB broth (Invitrogen) supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin (Sigma) at 37°C. Protein expression was induced at OD 0.5 with 0.2 mM IPTG (Sigma) and grown at 37°C for 3 hr to overnight. Baculoviruses were produced and amplified in Sf9 cells grown in Grace’s Insect Medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.1% Poloxamer 188 (Sigma), and 10 μg/ml gentamicin (Gibco) at 27°C. For protein expression, High Five cells were infected with baculoviruses at the density of 5 X 105 cells/ml and grown in Grace’s Insect Medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.1% Poloxamer 188 (Sigma), and 10 μg/ml gentamicin (Gibco) for 2 days at 27°C.

Growth and manipulation of 697 cells.

The human pre-B leukemia 697 cell line was grown in RPMI1640 (Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C. For cell differentiation, cells were treated with 0.5 ug/ml TPA (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate, Sigma) for 24 hr unless stated otherwise. The stable 697 cell line that inducibly expresses FLAG-HA-NAP1, designated 697(FH-NAP1) was established by co-infection with lentiviruses that contain, respectively, a 5xTetO2-miniCMV promoter-driven FLAG-HA-NAP1 cassette and an EF1a promoter-driven rtTA3-IRES-puromycin cassette, clonal cell selection by treatment with 1 μg/mL puromycin for 2 weeks in MethoCult Medium supplemented with 10% FBS, and screening for positive clones by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody.

METHOD DETAILS

Construction of the Widom 601 array-promoter DNA template

Two 25-repeat arrays of 197 bp Widom 601 sequences (Robinson et al., 2006) were cloned in tandem (total 50 repeats) in pUC18. For the Gal4-VP16–activated template, a DNA fragment containing 5 Gal4 binding sites, HIV TATA and Ad2 ML INR (core promoter) elements and a G-less cassette) was excised from pG5HML (Malik et al., 2002) and cloned between the arrays (Fig. S1A). For the NF-κB/SP1–activated template, the CD40 enhancer (−530 to −85) was cloned from 697 cells and inserted upstream of the HIV TATA–Ad2ML INR–G-less cassette sequences in place of the Gal4 binding sites (Fig. 4G). For chromatin assembly, the array DNA templates were excised from pUC18 plasmids by restriction enzyme digestion of both array ends. For immobilized template assays (see below), digested linear DNA templates were 5’-biotinylated by Klenow enzyme with biotin-14-dATP (Thermo Fisher).

Assembly of H1-compacted chromatin

Chromatin was assembled by mixing the linear array DNA template (Figs. 4G and S1A), carrier DNA (amplified segment of the pUC18 vector using the PCR primers in Table S2), recombinant histone octamer and linker histone in a 2 M NaCl solution followed by dialysis to 10 mM NaCl. The arrays then were folded into compact structures by dialysis into 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM triethanolamine hydrochloride (TEA) (pH 7.4) (Robinson et al., 2008). The reconstitution and folding of nucleosome arrays was monitored by electrophoresis in native agarose gels and by electron microscopy of negatively stained samples (Robinson et al., 2008).

Electron microscopy

For visualization by negative stain, chromatin samples at a concentration of 50 μg/ml were gently fixed on ice in 0.1% (v/v) glutaraldehyde for 30 min. Drops (4 μl) were applied to a continuous carbon layer covering an air discharge-treated 200-mesh copper/palladium grid. After 1 min, grids were washed with 40 μl of 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate, blotted and left to air dry. Images were recorded on a FEI TECNAI G2 Spirit BioTwin Transmission Electron Microscope.

Purification of recombinant proteins

Xenopus histone octamers were purified following expression in BL21 E.coli as described (An et al., 2002). Human linker histone H1 was cloned into pET11a vector, expressed in BL21 E.coli, and, after removal of other proteins from the extract by HCl-precipitation, purified from the supernatant by SP-Sepharose (GE healthcare) and Bio-gel HT hydroxyapatite (Bio-Rad) chromatography. FLAG-tagged Gal4-VP16, NF-κB (p50/p65), SP1 and p300 were purified as described (An et al., 2002; Guermah et al., 2009). His-tagged p300 and p300DY were expressed from baculovirus vectors in High Five cells and affinity purified on TALON beads (Clontech). His-tagged human H1 chaperones (NAP1, TAF-1β and NASPs) were cloned into pET15b, expressed in BL21 E. coli, and purified from derived extracts by HiTrap Q HP ion exchange chromatography (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) followed by TALON binding. His-tagged NAP1 deletion mutants were expressed in BL21 E. coli and purified on TALON beads. Drosophila Acf1 and ISWI (which together comprise ACF) were co-expressed from baculovirus vectors in Sf9 cells and purified by HiTrap SP and Q HP ion exchange chromatography. The human SWI-SNF complex was purified as described (Sif et al., 1998).

In vitro transcription assays

Except for minor modifications, assays were performed as detailed in (An and Roeder, 2004) and outlined in Fig. S1F. In the first step (activator binding), chromatin template (100 ng) and activator (20 ng) were incubated in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 4 mM MgCl2 and 60 mM KCl for 10 min at 30°C. In the second step (chromatin modification), p300 (10 ng), H1 chaperone (0.05 μM), and acetyl-CoA (5 μM) were added and incubation continued for 10 min at 30°C. In the third step (PIC formation) HeLa extract (30 μg protein) was added and incubation continued for 10 min at 30°C. In the fourth step, ATP, UTP, 32P-CTP, RNasin (Promega), and 3’-O-methyl GTP (0.05 mM) were added and incubation continued for 60 min at 30°C. Reactions were stopped and processed as described (An and Roeder, 2004) and RNA monitored by autoradiography. Note that factor additions and omissions were as indicated in individual figures.

In vitro HAT assays

HAT reactions contained, as indicated in individual figures, chromatin or free octamer (150 ng), activator (20 ng), p300 (10 ng), NAP1 (0.05 μM) where indicated, and either unlabeled acetyl-CoA (10 uM) or 3H-acetyl-CoA (Perkin Elmer) in HEGK100 buffer (10 mM HEPES pH7.6, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 10 mM KCl, 100 mM NaCl). After 1 hr incubation at 30 °C, polyethyleneimine was added to a final concentration of 0.8% and the chromatin was precipitated and washed in BC100 buffer (10 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.9, 10% glycerol, and 100 mM KCl). The precipitate was suspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, boiled, and separated by SDS-PAGE. Acetylated histones were detected either by autoradiography or by immunoblotting with antibodies to specific acetylated histone marks (see KEY RESOURCES TABLE).

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-FLAG M2 antibody | Sigma | F1804; RRID: AB_262044 |

| anti-His tag antibody | Qiagen | 34660; RRID: AB_2619735 |

| anti-HA tag antibody | Abcam | ab9110; RRID: AB_307019 |

| anti-H1 antibody | Millipore | 05-457; RRID:AB_310843 |

| anti-H1.2 antibody | Abcam | ab4086; RRID:AB_2117983 |

| anti-H2B antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-8650; RRID:AB_2118153 |

| anti-Histone H3 antibody | Abcam | ab1791; RRID: AB_302613 |

| anti-H3K9ac antibody | Abcam | ab4441; RRID:AB_2118292 |

| anti-H3K14ac antibody | Millipore | 06-911; RRID:AB_310294 |

| anti-H3K18ac antibody | Abcam | ab1191; RRID:AB_298692 |

| anti-H4ac antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-377521 |

| anti-H4K5ac antibody | Abcam | ab51997; RRID:AB_2264109 |

| anti-H4K8ac antibody | Millipore | 07-328; RRID:AB_11213282 |

| anti-H4K16ac antibody | Upstate | 07-329; RRID:AB_310525 |

| anti-p65 antibody | Abcam | ab7970; RRID:AB_306184 |

| anti-p300 antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-585; RRID: AB_2231120 |

| anti-RNAP1I | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-899; RRID:AB_632359 |

| anti-CTCF | Millipore | 17-10044;RRID:AB_10732951 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Biological Samples | ||

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| TPA (12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate) | Sigma | P8139 |

| Acetyl-CoA | Sigma | A2056 |

| 3x FLAG peptide | Sigma | F4799 |

| Glutathione Sepharose 4B | GE Healthcare | 17075601 |

| Bio-gel HT hydroxyapatite | Bio-Rad | 130-0520 |

| Anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel | Sigma | A2220 |

| TALON-beads | Clontech | 635501 |

| Dynabeads M-280 streptavidin | Invitrogen | 11205D |

| Dynabeads Protein A | Invitrogen | 10001D |

| SP sepharose | GE healthcare | 17108703 |

| HiTrap SP HP | GE healthcare | 17115201 |

| HiTrap Q HP | GE healthcare | 17115401 |

| ATP | Sigma | A2383 |

| ATP (for transcription) | GE healthcare | 27205601 |

| UTP (for transcription) | GE healthcare | 27208601 |

| CTP (for transcription) | GE healthcare | 27206601 |

| 3’-O-methyl GTP (for transcription) | TriLink | N1058 |

| 32P-CTP (for transcription) | Perkin Elmer | Blu008H001MC |

| 3H-acetyl-CoA | Perkin Elmer | NET290050UC |

| MNase | TAKARA Bio | 2910A |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| ChIP assay kit | Millipore | 17-295 |

| QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit | Qiagen | 28106 |

| RNeasy Mini Kit | Qiagen | 74104 |

| qScript cDNA SuperMix | Quant BioSciences | 95048 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| ChIP-seq RNA-seq datasets and files | This study | GSE126083 |

| Raw Data | Mendeley | http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/9r3grs3xfn.1 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Sf9 cells | ATCC | CRL-1711 |

| High Five cells | Thermo Fisher Sc. | B85502 |

| Human pre-B leukemic 697 cells | DSMZ | ACC42 |

| 697 (FH-NAP1) | This study | |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| BL21(DE3)pLysS competent cells | Merck | 69451 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| ChIP primers | This study (Fisher Sci) | See TableS2 |

| qPCR primers | This study (Fisher Sci) | See TableS2 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| p601 | Robinson et al., 2006 | |

| p601G5HM | This study | |

| p601CD40HM | This study | |

| pLKO.1-puro-NAP1L1-shRNA | Sigma | TRCN0000148741 |

| pLKO.1-puro-CTCF-shRNA | Sigma | TRCN0000218498 |

| pLKO.1-puro-p65-shRNA | Sigma | TRCN0000014684 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| TOPHAT | Trapnell et al., 2009 | https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml |

| HOMER | Heinz et al., 2010 | http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/ |

| Bowtie | Langmead et al., 2009 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/index.shtml |

| SAMtools | Li et al., 2009 | http://www.htslib.org/ |

| Integrative Genomics Viewer | Broad Institute, Robinson et al., 2011 | http://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/ |

| Igvtools | Broad Institute | https://software.broadinstitute.org/software/igv/igvtools |

| Other | ||

In vitro binding assay

To detect recruitment of factors to chromatin templates, 25 ng tagged protein (FLAG-Gal4-VP16 or His-NAP1) was incubated with 100 ng chromatin template and then conjugated with an affinity resin. The resin was washed with BC300 buffer (10 mM HEPES pH7.9, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 300 mM KCl and 0.1% triton X-100) and the DNA template in bound chromatin was isolated by proteinase K and phenol/chloroform procedures and monitored by agarose gel electrophoresis. For pull-down assays, GST-, His-, FLAG-tagged proteins were conjugated, respectively, to Glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare), TALON (Clontech), or M2-agarose (Sigma), followed by incubation with purified proteins (generally 100 ng) in BC300 buffer. After washing of affinity resins, bound proteins were eluted in SDS-sample buffer and monitored by immunoblotting.

Supercoiling assay

Supercoiling and MNase-digestion assays were performed as described (An and Roeder, 2004).

Immobilized template assay

Biotinylated DNA was assembled into chromatin and 1 μg of chromatin template was mixed with factors (activator, p300, NAP1 and acetyl-CoA) in BC100 buffer containing 0.2 mg/ml BSA. After 1 hr incubation at 30 °C, the chromatin template was conjugated to Dynabeads M-280 Streptavidin (Invitrogen) and separated from the unbound fraction (sup). Proteins in unbound fraction was precipitated by TCA and resuspended in SDS-sample buffer. The beads were washed with BC300 buffer containing 0.1% NP-40 and 1 mM DTT and bound proteins were extracted in SDS-sample buffer (pellet). H1 protein was detected by immunoblotting with anti-H1.2 antibody (Abcam). The DNA template in the Dynabeads-bound chromatin was extracted (from 10% of the sample) and detected by agarose gel electrophoresis.

In vitro ChIP-qPCR assay

Biotinylated DNA was assembled into chromatin as described above and 0.2 ug of the resulting chromatin template was mixed with indicated factors in HEGK100 buffer containing 0.2 mg/ml BSA. Activator, p300, acetyl-CoA, and NAP1 concentrations were as indicated in transcription assays and ACF and ATP concentrations were 0.01 mM and 0.5 μM, respectively. After 1 hr incubation at 30 °C, the chromatin template was conjugated to a Dynabeads M-280 Streptavidin and washed with HEGK100 buffer containing 0.1% NP-40 and 1 mM DTT. The bead-bound chromatin template was digested with MNase to generate 2-3 nucleosome arrays and isolated arrays were incubated overnight at 4 °C with Dynabeads Protein A (Invitrogen)-conjugated antibody (against H1, H2B or H3). After washing the beads with HEGK100 buffer containing 0.1% NP-40 and 1 mM DTT, DNA was extracted and analyzed by qPCR using primers that amplified the activator binding/promoter region indicated in Table S2.

shRNA knockdown of NAP1

For knockdown, 1 × 107 697 cells were infected with NAP1 shRNA lentivirus plus 8 ug/ml polybrene in RPMI1640 medium for 12 hr. After culture for 2 days in normal medium, cells were treated with 1μg/ml puromycin for 2 days and the NAP1 mRNA level was then measured by RT-qPCR.

RNA-seq

Total RNA from 697 cells was extracted using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) and subjected to high-throughput sequencing. Illumina multiplexing library construction with TruSeq RNA-seq Library Prep kit, HiSeq 2000 SR50 sequencing, and raw data generation were performed by the Epigenomics Core Facility at Weill Cornell Medical College (New York, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Raw image data were converted into base calls and fastq files via the Illumina pipeline CASAVA version 1.8 with default parameters. All 50-base reads were mapped to the reference HG19 human genome sequence using TopHat with the default parameters (Trapnell et al., 2009). The mRNA level for each expressed gene/transcript was analyzed by HOMER software (Heinz et al., 2010) with default parameters and represented as RPKM (reads per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped).

ChIP-seq and ChIP-qPCR

697 or 697(FH-NAP1) cells were treated with 0.5 μg/ml TPA (Sigma) for 0-24 hrs. ChIP assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Upstate) with specific antibodies (see KEY RESOURCES TABLE). For ChIP-seq analyses, 10 ng ChIP products were submitted to Epigenomics Core Facility at Weill Cornell Medical College for high-throughput sequencing. ChIP-seq reads (50-mer) were aligned to HG19 human genome assembly using Bowtie (Langmead et al., 2009), with parameters "−n 2 −m 1 −l 36 --best". Potential PCR duplicates were removed using samtools rmdup command (Li et al., 2009). Tiled data files (TDF) were generated by igvtools with parameters "−z 5 −w 10 −e 200" and visualized using Integrative Genomics Viewer (Robinson et al., 2011). For ChIP-qPCR, ChIP products were analyzed by qPCR using the primers probing the promoter regions of the target genes as indicated in Table S2.

DATA RESOURCES

The RNA-seq and ChIP-seq data have been deposited in the GEO databases (see KEY RESOURCES TABLE).

Supplementary Material

Table S1 (Related to Fig 4) RNA-sequence data

Table S2 (Related to METHOD DETAILS) primer sequence

Highlights.

H1 blocks transcription, in part, by blocking core histone acetylation by p300

An activator-p300-NAP1 pathway evicts H1 in a gene- and activator-specific manner

Gene activation in cells leads to a wave of H1 eviction from activator binding sites

The wave of H1 eviction ends at the nearest CTCF binding site

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank K. Uryu in the Rockefeller University EM resource center for help with EM, and the Epigenomics Core Facility at Weill Cornell Medical College for the use of the NGS services and facilities. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (CA129325, DK071900, CA178765) and the Starr Cancer Consortium (I9-89-062) to R.G.R, and by a grant to W.Y.C from MOST (107-2320-B-010-024-MY3). W.Y.C. is also supported by the Cancer Progression Research Center, National Yang-Ming University from the Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan. T.O. was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Rockefeller University and is a Junior Fellow of the Simons Foundation (#527795).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- An W, Palhan VB, Karymov MA, Leuba SH, and Roeder RG (2002). Selective requirements for histone H3 and H4 N termini in p300-dependent transcriptional activation from chromatin. Mol Cell 9, 811–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An W, and Roeder RG (2004). Reconstitution and transcriptional analysis of chromatin in vitro. Methods Enzymol 377, 460–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara H, Tartare-Deckert S, Nakagawa T, Ikehara T, Hirose F, Hunter T, Ito T, and Montminy M (2002). Dual roles of p300 in chromatin assembly and transcriptional activation in cooperation with nucleosome assembly protein 1 in vitro. Mol Cell Biol 22, 2974–2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunschweig U, Hogan GJ, Pagie L, and van Steensel B (2009). Histone H1 binding is inhibited by histone variant H3.3. EMBO J 28, 3635–3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao K, Lailler N, Zhang Y, Kumar A, Uppal K, Liu Z, Lee EK, Wu H, Medrzycki M, Pan C, et al. (2013). High-resolution mapping of h1 linker histone variants in embryonic stem cells. PLoS Genet 9, e1003417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausell J, Happel N, Hale TK, Doenecke D, and Beato M (2009). Histone H1 subtypes differentially modulate chromatin condensation without preventing ATP-dependent remodeling by SWI/SNF or NURF. PLoS One 4, e0007243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denker A, and de Laat W (2016). The second decade of 3C technologies: detailed insights into nuclear organization. Genes Dev 30, 1357–1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorigo B, Schalch T, Bystricky K, and Richmond TJ (2003). Chromatin fiber folding: requirement for the histone H4 N-terminal tail. Journal of molecular biology 327, 85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Nikitina T, Zhao J, Fleury TJ, Bhattacharyya R, Bouhassira EE, Stein A, Woodcock CL, and Skoultchi AI (2005). Histone H1 depletion in mammals alters global chromatin structure but causes specific changes in gene regulation. Cell 123, 1199–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch JT, and Klug A (1976). Solenoidal model for superstructure in chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 73, 1897–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan TW, and Brown DT (2016). Molecular dynamics of histone H1. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1859, 468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan TW, Files JK, Casano KR, George EM, and Brown DT (2016). Photobleaching studies reveal that a single amino acid polymorphism is responsible for the differential binding affinities of linker histone subtypes H1.1 and H1.5. Biol Open 5, 372–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyodorov DV, Zhou BR, Skoultchi AI, and Bai Y (2017). Emerging roles of linker histones in regulating chromatin structure and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeven G, Zhu Y, Kim BJ, Bartholdy BA, Yang SM, Macfarlan TS, Gifford WD, Pfaff SL, Verstegen MJ, Pinto H, et al. (2015). Local compartment changes and regulatory landscape alterations in histone H1-depleted cells. Genome Biol 16, 289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert N, Boyle S, Fiegler H, Woodfine K, Carter NP, and Bickmore WA (2004). Chromatin architecture of the human genome: gene-rich domains are enriched in open chromatin fibers. Cell 118, 555–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guermah M, Kim J, and Roeder RG (2009). Transcription of in vitro assembled chromatin templates in a highly purified RNA polymerase II system. Methods 48, 353–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, and Grunstein M (1988). Nucleosome loss activates yeast downstream promoters in vivo. Cell 55, 1137–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, and Glass CK (2010). Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell 38, 576–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera JE, West KL, Schiltz RL, Nakatani Y, and Bustin M (2000). Histone H1 is a specific repressor of core histone acetylation in chromatin. Mol Cell Biol 20, 523–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Ikehara T, Nakagawa T, Kraus WL, and Muramatsu M (2000). p300-mediated acetylation facilitates the transfer of histone H2A-H2B dimers from nucleosomes to a histone chaperone. Genes Dev 14, 1899–1907. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwafuchi-Doi M, Donahue G, Kakumanu A, Watts JA, Mahony S, Pugh BF, Lee D, Kaestner KH, and Zaret KS (2016). The Pioneer Transcription Factor FoxA Maintains an Accessible Nucleosome Configuration at Enhancers for Tissue-Specific Gene Activation. Molecular cell 62, 79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwafuchi-Doi M, and Zaret KS (2016). Cell fate control by pioneer transcription factors. Development 143, 1833–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo A, Kamieniarz-Gdula K, Ramirez F, Noureen N, Kind J, Manke T, van Steensel B, and Schneider R (2013). The genomic landscape of the somatic linker histone subtypes H1.1 to H1.5 in human cells. Cell Rep 3, 2142–2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadota S, and Nagata K (2014). Silencing of IFN-stimulated gene transcription is regulated by histone H1 and its chaperone TAF-I. Nucleic Acids Res 42, 7642–7653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamieniarz K, Izzo A, Dundr M, Tropberger P, Ozretic L, Kirfel J, Scheer E, Tropel P, Wisniewski JR, Tora L, et al. (2012). A dual role of linker histone H1.4 Lys 34 acetylation in transcriptional activation. Genes Dev 26, 797–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, Kim K, Punj V, Liang G, Ulmer TS, Lu W, and An W (2015). Linker histone H1.2 establishes chromatin compaction and gene silencing through recognition of H3K27me3. Sci Rep 5, 16714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Lee B, Kim J, Choi J, Kim JM, Xiong Y, Roeder RG, and An W (2013). Linker Histone H1.2 cooperates with Cul4A and PAF1 to drive H4K31 ubiquitylation-mediated transactivation. Cell Rep 5, 1690–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar R, and Kraus WL (2010). PARP-1 regulates chromatin structure and transcription through a KDM5B-dependent pathway. Mol Cell 39, 736–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, and Salzberg SL (2009). Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10, R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laybourn PJ, and Kadonaga JT (1991). Role of nucleosomal cores and histone H1 in regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II. Science 254, 238–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBien TW (2000). Fates of human B-cell precursors. Blood 96, 9–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Carey M, and Workman JL (2007). The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 128, 707–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Margueron R, Hu G, Stokes D, Wang YH, and Reinberg D (2010). Highly compacted chromatin formed in vitro reflects the dynamics of transcription activation in vivo. Mol Cell 38, 41–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, and Durbin R (2009). The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 25, 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luse DS, and Roeder RG (1980). Accurate transcription initiation on a purified mouse beta-globin DNA fragment in a cell-free system. Cell 20, 691–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier VK, Chioda M, Rhodes D, and Becker PB (2008). ACF catalyses chromatosome movements in chromatin fibres. Embo j 27, 817–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Wallberg AE, Kang YK, and Roeder RG (2002). TRAP/SMCC/mediator-dependent transcriptional activation from DNA and chromatin templates by orphan nuclear receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4. Mol Cell Biol 22, 5626–5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurkiewicz J, Kepert JF, and Rippe K (2006). On the mechanism of nucleosome assembly by histone chaperone NAP1. J Biol Chem 281, 16462–16472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkenschlager M, and Nora EP (2016). CTCF and Cohesin in Genome Folding and Transcriptional Gene Regulation. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 17, 17–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou HD, Phan S, Deerinck TJ, Thor A, Ellisman MH, and O'Shea CC (2017). ChromEMT: Visualizing 3D chromatin structure and compaction in interphase and mitotic cells. Science 357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YJ, Chodaparambil JV, Bao Y, McBryant SJ, and Luger K (2005). Nucleosome assembly protein 1 exchanges histone H2A-H2B dimers and assists nucleosome sliding. J Biol Chem 280, 1817–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YJ, and Luger K (2006). The structure of nucleosome assembly protein 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103, 1248–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postnikov YV, and Bustin M (2016). Functional interplay between histone H1 and HMG proteins in chromatin. Biochim Biophys Acta 1859, 462–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SSP, Huang SC, Glenn St Hilaire B, Engreitz JM, Perez EM, Kieffer-Kwon KR, Sanborn AL, Johnstone SE, Bascom GD, Bochkov ID, et al. (2017). Cohesin Loss Eliminates All Loop Domains. Cell 171, 305–320 e324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci MA, Manzo C, Garcia-Parajo MF, Lakadamyali M, and Cosma MP (2015). Chromatin fibers are formed by heterogeneous groups of nucleosomes in vivo. Cell 160, 1145–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, and Mesirov JP (2011). Integrative genomics viewer. Nature biotechnology 29, 24–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PJ, An W, Routh A, Martino F, Chapman L, Roeder RG, and Rhodes D (2008). 30 nm chromatin fibre decompaction requires both H4-K16 acetylation and linker histone eviction. J Mol Biol 381, 816–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PJ, Fairall L, Huynh VA, and Rhodes D (2006). EM measurements define the dimensions of the "30-nm" chromatin fiber: evidence for a compact, interdigitated structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 6506–6511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PJ, and Rhodes D (2006). Structure of the '30 nm' chromatin fibre: a key role for the linker histone. Current opinion in structural biology 16, 336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]