Abstract

Multi-energy CT acquires simultaneous multiple x-ray attenuation measurements from different energy spectra which facilitates the computation of virtual monoenergetic images (VMI) at a specific photon energy (keV). Since the contrast between iodine attenuation and the attenuation of surrounding soft tissues increases at lower x-ray energies, VMIs in the range of 40–70 keV can be used to improve iodine visualization. However, at lower energy levels, image noise in VMIs is substantially increased, which counteracts the benefits from the increased iodine contrast, resulting in a decreased iodine contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR). There exists considerable data redundancy between multi-energy CT images created from the same acquisition. Similarly, a substantial spatio-spectral data redundancy exists between multi-energy CT images and the corresponding VMIs. In this work, we develop a denoising framework that exploits this data redundancy to improve iodine CNR in the VMIs. We accomplish this by applying prior-knowledge-aware iterative denoising to low-energy VMIs; we refer to the denoised images as mono-PKAID images. The proposed framework was evaluated using phantom and in vivo data acquired on a research whole-body photon-counting-detector CT, as well as using data from a commercial dual-source dual-energy CT system. The results of phantom experiments show that the proposed framework can preserve image resolution and noise texture compared to the original VMIs, while reducing noise to improve iodine CNR. Quantitative measurements show that the iodine CNR of 50 keV VMI is improved by 1.8-fold using the proposed method, relative to the VMI produced using commercial software (Mono+). With mono-PKAID, VMIs at lower keV take full advantage of higher iodine contrast without substantially increasing image noise. These observations were confirmed using patient data sets, which demonstrated that mono-PKAID reduced image noise, improved CNR in anatomical regions with iodine perfusion by 1.8-fold, and potentially enhanced the visibility of focal liver lesions.

Keywords: virtual monoenergetic imaging, virtual monochromatic imaging, photon counting detector, spectral CT, noise reduction

1. Introduction

Compared to conventional single-energy CT, multi-energy CT acquires two or more x-ray attenuation measurements with different energy spectra, which allows materials of different elemental composition to be differentiated (Coursey et al 2010, McCollough et al 2015). Various technical solutions have been developed to acquire multi-energy data sets, such as fast kV switching (Kalender et al 1986, Xu et al 2009), multilayer detector (Carmi et al 2005), split beam filtration (Almeida et al 2017), and dual-source dual-energy approach (Flohr et al 2006). Photon counting detector (PCD) is another promising technique that has gained considerable research attention recently (Kappler et al 2010, 2012, McCollough et al 2015, Gutjahr et al 2016, Pourmorteza et al 2016, Yu et al 2016a, Muenzel et al 2017, Willemink et al 2018). Being able to differentiate the energy of each incident photon, PCD-CT is an appealing technique suitable for multi-energy CT.

Since its introduction, multi-energy CT has demonstrated its unique value in various clinical applications such as calcified plaque removal (Korn et al 2011), urinary stone characterization (Primak et al 2007), virtual unenhanced imaging (Ferda et al 2009), and gout characterization (Glazebrook et al 2011). In addition, multi-energy data sets can also be used to synthesize virtual monoenergetic (or monochromatic) images (VMI) at a distinct photon energy (keV) (Matsumoto et al 2011, Yu et al 2012, Grant et al 2014, Leng et al 2015, Chang et al 2018). The synthesized VMIs can then be utilized for clinical diagnosis, similar to the conventional CT images acquired with a single poly-energetic spectrum. Depending on the technique used to acquire multi-energy CT data, the VMIs can be synthesized via projection domain or image domain approach (Yu et al 2012). The projection domain approach is typically used when coincident multi-energy projection data are available, such as for systems using dual-layer detectors. Recently, VMI obtained from a dual-layer detector-based spectral CT using anti-correlated noise reduction in the reconstruction has been demonstrated (Kalisz et al 2018). For dual-source, dual-energy CT systems, image-domain post-processing is adopted since the projection data acquired on different sub-systems are not spatially well-registered.

The photon energy at which the VMI is synthesized can be adjusted to suit the needs of various clinical applications. At lower energies (40–70 keV), iodine attenuation increases markedly compared to the surrounding tissues. This is due to the increased photoelectric effect above k-edge of iodine at 33 keV (McCollough et al 2015). Hence, VMIs around 40–70 keV can be used to improve iodine contrast, which can assist with clinical tasks such as CT angiography (Albrecht et al 2016a, 2016b), liver lesion and renal mass characterization (Shuman et al 2014, Caruso et al 2017, Patel et al 2018), and detection of pulmonary embolism with suboptimal contrast attenuation (Leithner et al 2017). However, the increased iodine contrast comes with a noise penalty. At lower x-ray energy levels, the noise in VMIs is substantially increased, which may compromise the benefit from increased image contrast, and consequently result in a decreased iodine contrast to noise ratio (CNR). Various methods have been developed to reduce image noise in VMI, such as that based on a spatial frequency-split technique (Grant et al 2014, Frellesen et al 2016), anti-correlated noise reduction (Kalisz et al 2018), edge-preserving filter-based denoising (Li et al 2014), as well as techniques based on learned dictionary (Mechlem et al 2017, Xie et al 2018).

Within the multi-energy CT data set, there exists a considerable amount of data redundancy. In the case of PCD-CT, for example, the energy-bin images generated from photons within a specific energy window are highly correlated with the energy-threshold images generated from all the available photons (Leng et al 2011). Such data redundancy can be utilized to reconstruct low noise, energy-bin images from projection data acquired on a PCD-CT (Yu et al 2016c), as well as to perform quantitative material decomposition (Tao et al 2018). In addition to PCD-CT, this data redundancy is observed for other multi-energy CT implementations, such as between the images acquired with each individual sub-system on a dual-source, dual-energy CT system, or with the mixed images formed by combining the low- and high-energy images (Leng et al 2011).

Similarly, a substantial spatio-spectral data redundancy also exists between the multi-energy CT images and the associated VMIs (Leng et al 2011, Leng et al 2015). This is no surprise, as multi-energy CT data sets are used to synthesize the VMIs. In this work, we exploit this data redundancy to improve iodine CNR in the VMIs. This is accomplished by applying prior-knowledge-aware iterative denoising to the VMIs. As we will demonstrate, the proposed technique can preserve the spatial resolution and noise texture of the source VMIs while improving the iodine CNR. We refer to this method as virtual monoenergetic imaging with prior-knowledge-aware iterative denoising (mono-PKAID).

In this paper, we first describe how the spatio-spectral data redundancy between the multi-energy CT images and the VMIs can be exploited using mono-PKAID to improve iodine CNR. We then quantify the performance of mono-PKAID using a series of phantom experiments. Finally, in vivo patient data sets acquired on a research whole-body PDC-CT system, and a clinical dual-source, dual-energy CT system were evaluated to demonstrate the clinical feasibility of the proposed technique.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mono energetic imaging with prior knowledge aware iterative denoising (mono-PKAID)

The proposed method is inspired by an established CT reconstruction strategy called prior image constrained compressed sensing (PICCS) (Chen et al 2008). The PICCS framework was originally developed for reconstruction of dynamic CT images from highly undersampled projection data sets. With PICCS, a prior image reconstructed from fully sampled projection data at a given time point is compared to the image reconstructed from limited projections at another time point of interest. The temporal data redundancy between the two data sets is then exploited via the use of compressed sensing technique to suppress undersampling-induced artifacts. Later, the PICCS technique was extended to other CT applications such as dose reduction (Leng et al 2008, Chen et al 2009, Qi et al 2010, Lauzier et al 2012, Yu et al 2016c).

Noting the spatio-spectral data redundancy between multi-energy CT images and VMIs, we propose to denoise the VMI and improve iodine CNR using prior-knowledge-aware iterative denoising in image domain. The proposed mono-PKAID framework generates the desired VMI at a certain keV, x0, by minimizing the following objective function:

| (1) |

where the operator ‖·‖TV calculates the total-variation (TV) of an image; x represents the VMI of interest; xseed denotes the seed image, which is the original image output of any VMI package, such as Mono + (Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Forchheim, Germany). xprior is the low-noise, spectral prior image associated with the same imaging object. On the PCD-CT, the low-energy threshold (TL) image can be used as the prior image, since it contains all available photons from a single scan and has the lowest noise level. On the dual-source dual-energy CT, the mixed image between the low- and high-energy images is generated using all radiation dose applied to the patient, therefore has a lower noise level and is used as the prior.

The objective function in equation (1) contains a data fidelity term and a PKAID regularization term c‖x‖TV + (1 – c) ‖x − xprior‖TV, with λ controlling the relative contribution of the two terms. The value of λ is determined empirically based on the noise level of source images. The PKAID regularization term can be further separated into two components. The first component ‖x‖TV is the conventional TV regularization of the target image itself. The second component ‖x − xprior‖TV promotes spatiospectral sparsity by applying TV transform to the difference image between the VMI, x, and its corresponding spectral prior image, xprior. The second component exploits the spatio-spectral data redundancy to facilitate denoising by exerting spatiospectral sparsity regularization on x. Note that, since the VMI is (virtually) monoenergetic and the prior image is poly energetic, their difference image contains spectral information, and promoting image sparsity in the difference image simultaneously utilizes the spatial and spectral information. Finally, c is the PKAID parameter (0 ≤ c ≤ 1) that controls the relative weighting placed on one term versus the other. In this work, we used c = 0.1 for all cases.

The optimization problems shown in equation (1) can be solved using a standard iterative solver such as gradient descent algorithm (Nocedal and Wright 2006). Denote f (x) as the objective function shown in equation (1), i.e.

| (2) |

and further denote xi as the value of x in the ith iteration. The gradient descent algorithm then calculates the update of x according to the following iteration:

| (3) |

where the step size α can be determined via back tracking line search (Nocedal and Wright 2006).

2.2. Phantom Experiments

To quantitatively evaluate the proposed technique, phantom experiments were performed on a research, whole-body PCD-CT scanner (Somatom CounT, Siemens Healthcare GmbH) (Yu et al 2016a). This system was built using a second generation, dual-source dual-energy CT system (Somatom Definition Flash, Siemens Healthcare GmbH), with the second energy integrating detector (EID) replaced by a PCD unit. The PCD subsystem operates independently from the remaining EID sub-system; it has a 275 mm in-plane scan field-of-view (FOV). For scan objects exceeding the FOV of PCD, the EID subsystem, which has a 500 mm scan FOV, can be used to perform data completion scan and prevent truncation artifacts (Yu et al 2016b). The x-ray tube used for the PCD subsystem is identical to that used in the EID. Details on the design and technical performance of this system can be found elsewhere (Yu et al 2016a, Leng et al 2018). In this work, two scan modes, named Macro and Sharp, were used in the phantom and the patient scans. These two modes operated similarly in multi-energy processing, which was the focus of this study. Both Macro and Sharp modes allow two energy thresholds, i.e. threshold-low (TL) and threshold-high (TH), which can be used to create two energy bin data sets for multi-energy CT processing such as VMI. The main differences between Macro and Sharp modes are the effective pixel size and longitudinal collimation, as detailed in a previous work (Leng et al 2018). Despite these differences, their performances are expected to be similar for dual-energy processing such as VMI when medium or smooth reconstruction kernels are typically used.

For all data used in this work, the VMIs were generated using Mono + VMI toolbox by Siemens (Grant et al 2014). Note that, despite using Mono + as an example, the proposed strategy can be also adapted to other VMI packages. Further, it should be noted that Mono + uses a frequency-band filtration technique to reduce image noise relative to the first-generation VMI technique, i.e. ‘Mono’ (Grant et al 2014).

All the phantom and in vivo experiments performed on the PCD-CT system were reconstructed using a weighted filtered back projection (wFBP) algorithm (Stierstorfer et al 2004) with a medium-smooth, quantitative D30 kernel (image matrix = 512 × 512, FOV = 250 mm, slice thickness = 3 mm). For each PCD-CT data set, the corresponding TL images were used as the prior image for mono-PKAID. The mono-PKAID results were obtained by iteratively solving equation (1) using gradient descent algorithm with a fixed number of iterations (n = 500), which was found to be sufficient to ensure convergence for all cases. The parameter λ is used to control the relative preference between the data fidelity term and the regularization term. The value of λ should be determined based on desired image appearance. We used λ = 500 for all the data acquired on the experimental whole-body PCD-CT system, which was found to yield satisfactory denoising performance.

2.2.1. Modulation transfer function analysis

We evaluated the spatial resolution of images before and after mono-PKAID processing using the modulation transfer function (MTF) derived from edge spread function. The MTF analysis was performed on data acquired using a water phantom with cylindrical iodine inserts of different concentrations, therefore different contrast levels. Three cylindrical iodine inserts (30 mm diameter) (Gammex Inc., Middletown, WI, USA), with concentrations of 2, 5 and 10 mg ml−1, respectively, were submerged into a 300 mm × 250 mm (in the in-plane dimension) abdomen-shaped water tank and scanned on the PCD-CT system. The inserts were placed perpendicular to the axial acquisition plane. The axial scan was performed using a Macro mode abdomen protocol, with a 140 kV tube potential and a tube current time product of 100 mAs. The energy thresholds were set as 25 and 75 keV for TL and TH, respectively.

The MTF was determined for a 50 keV VMI before and after mono-PKAID processing. The 50 keV was chosen because it is routinely used in our clinical practice (Hanson et al 2018). To generate an MTF, edge spread functions across the boundary of a circular iodine insert were extracted and differentiated to yield line spread functions. The line spread functions were then averaged radially, and Fourier transformed to yield the MTFs. This process was repeated for all three iodine inserts of different concentrations (2, 5, 10 mg ml−1) to evaluate MTF for different contrast levels.

2.2.2. Noise power spectra analysis

The noise power spectrum (NPS) was used to compare the noise texture before and after mono-PKAID processing. The 50 keV VMIs generated from a water phantom scan were used for this analysis. For this test, a cylindrical, liquid water phantom with a diameter of 200 mm was scanned on the PCD-CT system using the same acquisition setting as the other scans (Macro mode, sequential scan, 140 kV tube potential, 25/75 keV for TL and TH, 74 mAs exposure). To calculate NPS, a total of 36 square-shaped ROIs (8 × 8 mm2) located on a 120 mm-diameter circle was extracted from the water phantom VMIs before and after mono-PKAID processing. The NPS for each ROI was then calculated using the method presented by Siewerdsen et al (2002), and averaged to yield the final NPS curve.

2.2.3. Noise and CNR measurement

To demonstrate the effect of mono-PKAID on image noise and iodine CNR, an abdominal multi-energy CT phantom (Gammex Inc., Middletown, WI, USA) was scanned on the PCD-CT system (Macro mode, axial scan, tube potential = 140 kV, 25/75 keV for TL/TH, tube current time product = 176 mAs), together with iodine inserts with various concentrations (2, 5, 10, 15 mg ml−1, respectively). The phantom was made from water-equivalent materials (solid water), and measured 400 mm × 300 mm in the in-plane dimension (figure 1), which mimics a medium-large patient size typically encountered in clinical practice. The VMIs at different energy levels ranging from 40 to 80 keV (with 10 keV increment) were generated from the abdominal phantom images, and processed using mono-PKAID. The iodine CNR values before and after mono-PKAID processing were measured, which is defined as the difference between mean ROI measurements of iodine and solid water background regions divided by the background noise.

Figure 1.

The abdominal phantom used in this work. The phantom is made from water equivalent material, and measures 40 × 30 cm in dimension, which mimics a medium-large patient size typically encountered in clinical practice.

The same phantom was also scanned using the same setup and different tube current time products (176, 154, 132, 110, 88, 66, 44 mAs) to evaluate the performance of mono-PKAID at different radiation dose levels.

2.3. In vivo studies on PCD-CT and dual-energy CT

The in vivo study was approved by our institutional review board. After written informed consent, a patient with liver metastasis was scanned on the PCD-CT using a contrast enhanced abdominal CT protocol. Data were acquired in the hepatic phase of enhancement after injecting 50 ml of iodinated contrast (Omnipaque 300; GE Healthcare; Milwaukee, WI, USA) using the Sharp acquisition mode with a 140 kV tube potential, 110 effective mAs, 1.0 spiral pitch, and 0.5 s rotation time. The energy thresholds were the same as those of the phantom experiments (25/75 keV for TL/TH). The tube potential and energy threshold setup used here was intended to strike a balance between spectral separation (between low- and high-energy bin data sets) and number of photons in each energy bin. Images were reconstructed using the same setting as the phantom scans (D30 kernel, image matrix = 512 × 512, FOV = 250 mm, slice thickness = 3 mm). The 50 keV VMIs were generated and processed using mono-PKAID. The iodine CNR values were measured from the VMIs before and after mono-PKAID processing, and compared with that of the corresponding TL image. The line profiles across the abdominal aorta in the images before and after mono-PKAID processing were extracted for comparison of spatial resolution.

To demonstrate the compatibility of the proposed technique with the conventional dual-energy CT platform, patient data from an abdominal contrast-enhanced exam was acquired on a clinical dual-source, dual-energy CT system (Somatom Definition Flash, Siemens Healthcare GmbH). The scan was performed using a clinical, late arterial-phase liver enhancement protocol after injecting 100 ml of iodinated contrast (Omnipaque 300, GE Healthcare), with a 32 × 0.6 mm collimation, 1.1 spiral pitch, 100/Sn140 kV tube potential (tube A/B), and a reference mAs = 210/162 mAs. Data were reconstructed using the Sinogram Affirmed Iteration Reconstruction (SAFIRE, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Forchheim, Germany) with a quantitative smooth kernel Q30, 512 × 512 matrix size, 380 mm FOV, and 3 mm slice thickness. The mixed images between Tube A and Tube B with a mixed ratio of 0.6 (Tube A) versus 0.4 (Tube B) were used as the spectral prior image for mono-PKAID. A λ = 1000 was used for this case. A higher value of λ was used here compared to the research PCD-CT images due to lower noise in these images and higher iodine contrast dose administrated in the clinical exam. Note that iterative reconstruction was used in this clinical example, while wFBP was used for the PCD-CT images. The 50 keV VMIs before and after mono-PKAID were generated for comparison.

3. Results

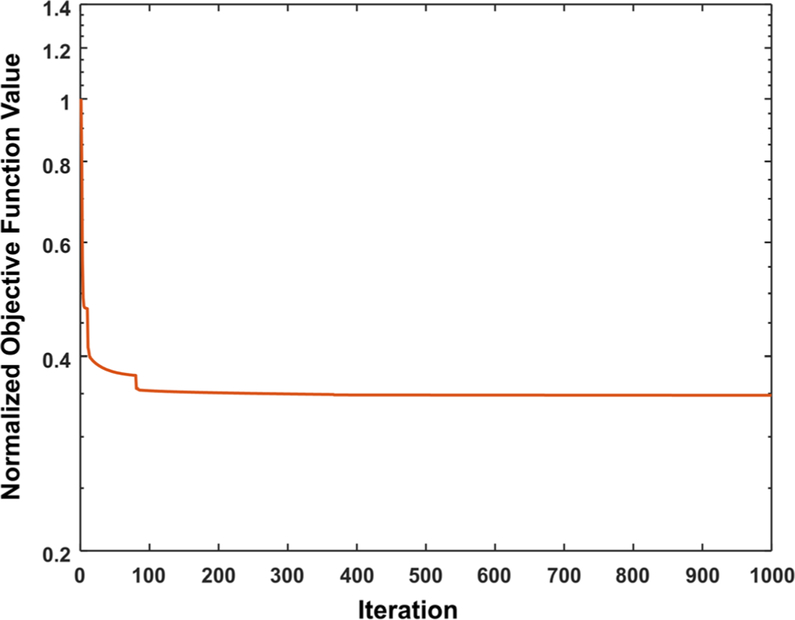

We first examined the convergence of the proposed algorithm. Figure 2 shows the normalized objective function values at different gradient-descent iterations ranging from 100 to 5000 for the phantom data set (λ = 500). The objective function value gradually decreased and stabilized progressively with increasing iteration. An iteration number of 500 was found to be sufficient for the algorithm to converge, and this value was used for the remainder of this work.

Figure 2.

Objective function values of the proposed mono-PKAID at each gradient descent iteration (λ = 500), showing convergence of the proposed algorithm after 500 iterations.

The MTFs of the original and mono-PKAID processed 50 keV VMIs are shown in figure 3. Figures 3(a)–(c) show the MTF curves measured using iodine phantom inserts with a concentration of 10 mg ml−1 (a), 5 mg ml−1 (b) and 2 mg ml−1 (c), respectively. Table 1 summarizes the widths of MTF curves at their 50% and 10% peak values for the 2 mg ml−1 iodine insert. The MTF curves measured from the original VMIs using different iodine inserts are comparable to that measured from the mono-PKAID images, suggesting that the spatial resolution of the original images is preserved after mono-PKAID processing. Table 1 shows that the widths of MTF curves at 50% and 10% peak values in VMIs after mono-PKAID processing are the same as those of the original VMIs.

Figure 3.

Modulation transfer function (MTF) measured using the iodine phantom inserts with a concentration of 10 mg ml−1 (a), 5 mg ml−1 (b), and 2 mg ml−1 (c) from the original virtual monoenergetic images (VMI) at 50 keV and the VMIs after mono-PKAID processing.

Table 1.

Widths of modulation transfer function (MTF) curves at 50% and 10% peak value measured from the original 50 keV virtual monoenergetic images (VMI) and 50 keV VMI after mono-PKAID processing. The values are measured based on the 10, 5, 2 mg ml−1 iodine inserts.

| Original VMI | Mono-PKAID | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iodine | Iodine | Iodine | Iodine | Iodine | Iodine | |

| 10 mg ml−1 | 5 mg ml−1 | 2 mg ml−1 | 10 mg ml−1 | 5 mg ml−1 | 2 mg ml−1 | |

| 50% MTF (mm−1) | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.29 |

| 10% MTF (mm−1) | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.53 |

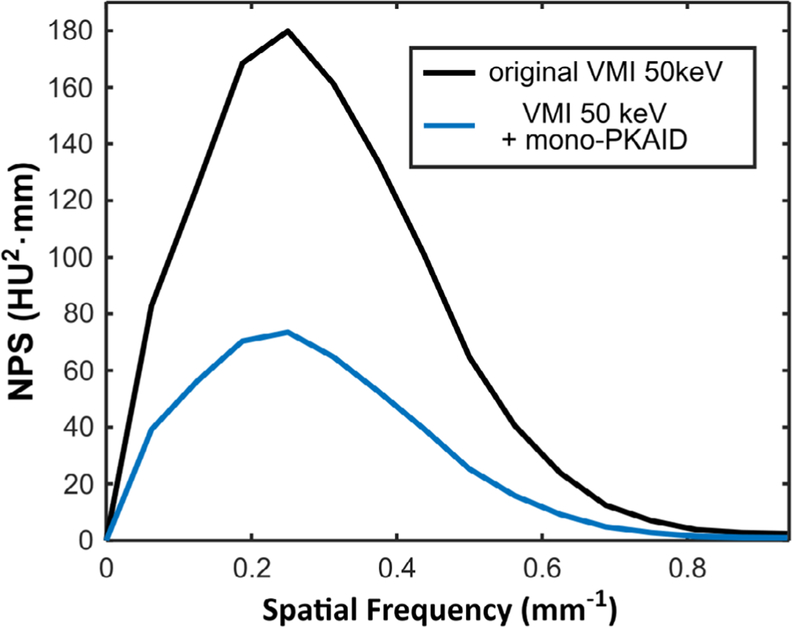

The NPS of the original VMIs at 50 keV and that after mono-PKAID processing are shown in figure 4. As shown, mono-PKAID retains the peak and shape of the NPS curve compared to the original VMIs while reducing the area under the curve, which suggests that the noise texture of the original images is preserved while the noise magnitude is decreased. The results in figures 3 and 4 confirm that the proposed mono-PKAID can retain both image resolution and noise texture while denoising.

Figure 4.

Noise power spectra (NPS) derived from water phantom data for the original virtual monoenergetic image (VMI) at 50 keV and the 50 keV VMI after mono-PKAID processing.

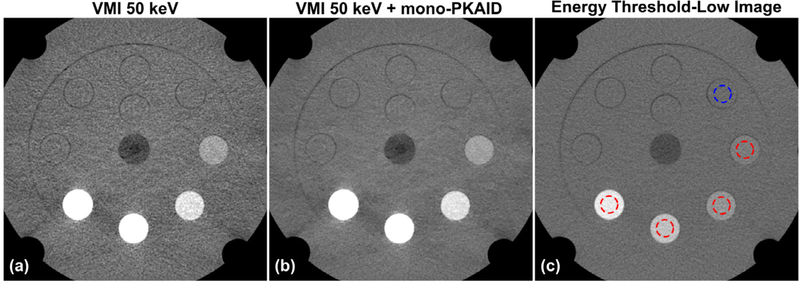

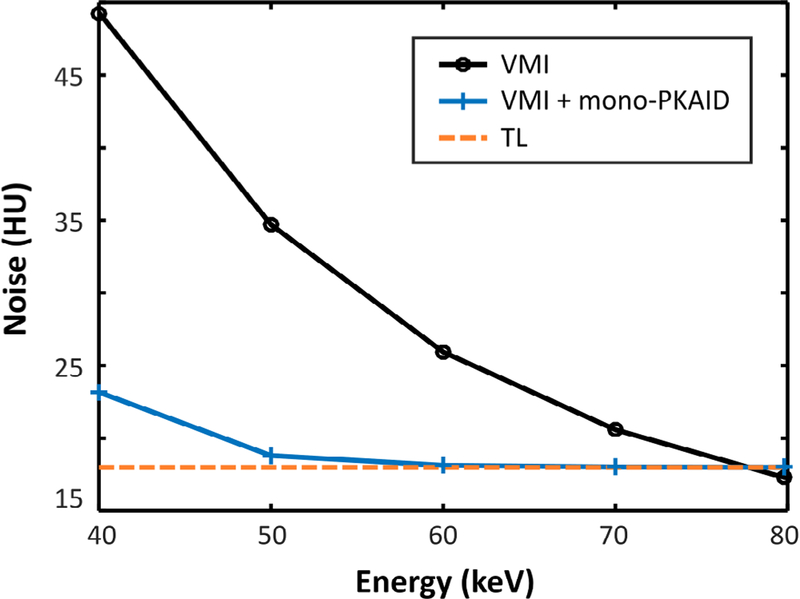

Figure 5 shows the 50 keV VMIs generated from the phantom data set before (a) and after (b) mono-PKAID processing, as well as the corresponding TL image. Note the enhanced iodine contrast in the 50 keV images compared to the TL image. The image noise in 50 keV images processed using mono-PKAID is visibly reduced compared to that of the original 50 keV VMIs. The image noise at different energy levels (keV) ranging from 40 to 80 keV measured from a circular ROI within the solid water phantom insert (blue circle in figure 5(c)) are summarized in figure 6. The image noise is reduced in the energy range of 40–70 keV, which is typically utilized for improving iodine contrast. At 50 keV, which is the energy level used in our clinical practice, the noise level is reduced from 35 HU to 19 HU. Since the mono-PKAID uses the TL image as the spectral prior, the image noise level of the mono-PKAID processed VMIs is similar to that of the TL image (18 HU).

Figure 5.

Virtual monoenergetic images (VMI) at 50 keV generated from the phantom data set before (a) and after (b) mono-PKAID processing. Figure (c) shows the corresponding energy threshold-low image. The image noise is evaluated based on the circular ROI located in the solid water inserts marked as the blue circle in (c), while the red circles show the ROIs used for iodine contrast measurements. The image artifacts in the VMI images such as the beam hardening were inherited from the vendor-provided VMI processing (Mono+), but not introduced by denoising. Window level/width (WL/WW) = 50/600 HU.

Figure 6.

Image noise levels measured from the virtual monoenergetic images (VMI) at different keVs generated using the abdominal phantom data set before and after processing with mono-PKAID. The noise level of the energy threshold-low (TL) images (keV independent) is also included. Mono-PKAID reduces image noise in the lower energy range (40–70 keV) VMIs compared to the original VMIs. This energy range is especially relevant for improving iodine contrast.

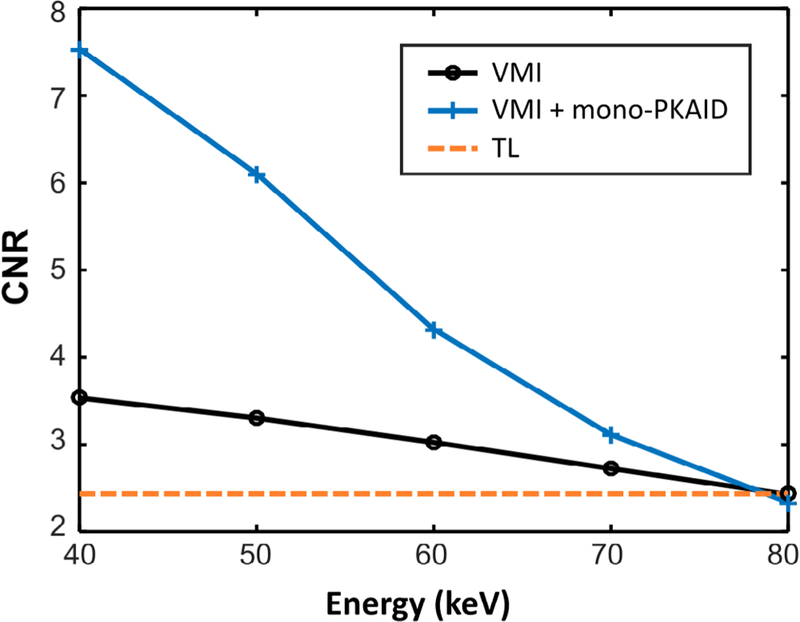

The iodine CNR values for different keV images before and after mono-PKAID processing are calculated based on circular iodine inserts of different concentrations and are shown in figure 7. As expected, the iodine CNR for different inserts gradually increases with decreased energy level. Table 2 lists the mean value and standard deviation measured from different ROIs (circles in figure 5(c)) in the 50 keV VMIs before and after mono-PKAID processing, as well as that of TL images. As shown in table 2, mono-PKAID is able to preserve the mean value of different iodine ROIs while reducing the standard deviations. This results in improved iodine CNR, especially for lower energy levels, as demonstrated in figure 7. At 50 keV, for example, the iodine CNR is increased from 3.3 to 6.1 for the 2 mg ml−1 iodine insert using mono-PKAID, yielding a 1.8 fold improvement.

Figure 7.

Iodine contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) measured from an iodine insert of 2 mg ml−1 in the virtual monoenergetic images (VMI) at different energy levels (i.e. keV) before and after mono-PKAID processing. The iodine CNR of the threshold-low (TL) images is also shown. Note the improved iodine CNR in the lower energy VMIs (40–70 keV) using mono-PKAID compared to the original VMIs.

Table 2.

Mean value and standard deviation measured from iodine inserts of different concentrations, as well as solid water insert, in the original 50 keV VMI, the 50 keV VMI after mono-PKAID processing, as well as the energy threshold-low images. The calculated iodine CNR values are also shown.

| Iodine | Iodine | Iodine | Iodine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (15 mg ml−1) | (10 mg ml−1) | (5 mg ml−1) | (2 mg ml−1) | Solid water | ||

| Original VMI 50 keV | ROI measurement (HU) | 797 ± 48 | 564 ± 48 | 286 ± 41 | 126 ± 36 | 11 ± 35 |

| Iodine CNR | 22.5 | 15.8 | 7.9 | 3.3 | — | |

| 50 keV + mono-PKAID | ROI measurement (HU) | 797 ± 26 | 563 ± 25 | 286 ± 25 | 126 ± 20 | 11 ± 19 |

| Iodine CNR | 41.4 | 29.1 | 14.5 | 6.1 | — | |

| Energy threshold-low | ROI measurement (HU) | 290 ± 19 | 197 ± 21 | 98 ± 21 | 40 ± 19 | −3 ± 18 |

| Iodine CNR | 16.3 | 11.1 | 5.6 | 2.4 | — |

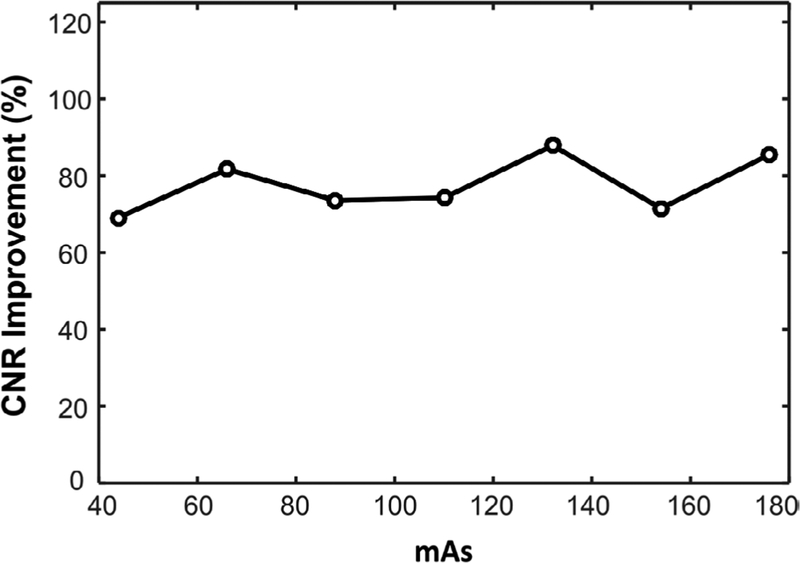

Figure 8 shows the iodine CNR improvement of the mono-PKAID processed 50 keV VMI compared to the original VMI measured from phantom images acquired using different radiation doses. The iodine CNR was measured from the 2 mg ml−1 iodine insert. These results demonstrate that mono-PKAID yielded consistent CNR improvement of 70% to 90% compared to the original VMI for different radiation dose levels.

Figure 8.

Improvement of iodine contrast-to-noise ratios (CNR) of mono-PKAID processed 50 keV virtual monoenergetic images (VMI) compared to the original VMI measured from images acquired using different current-time products (mAs).

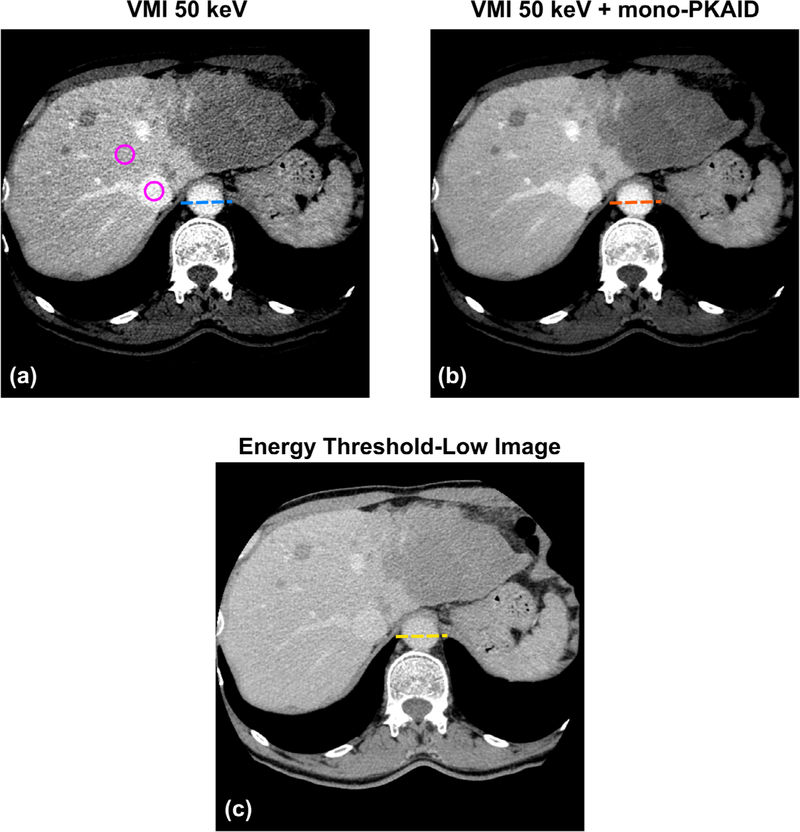

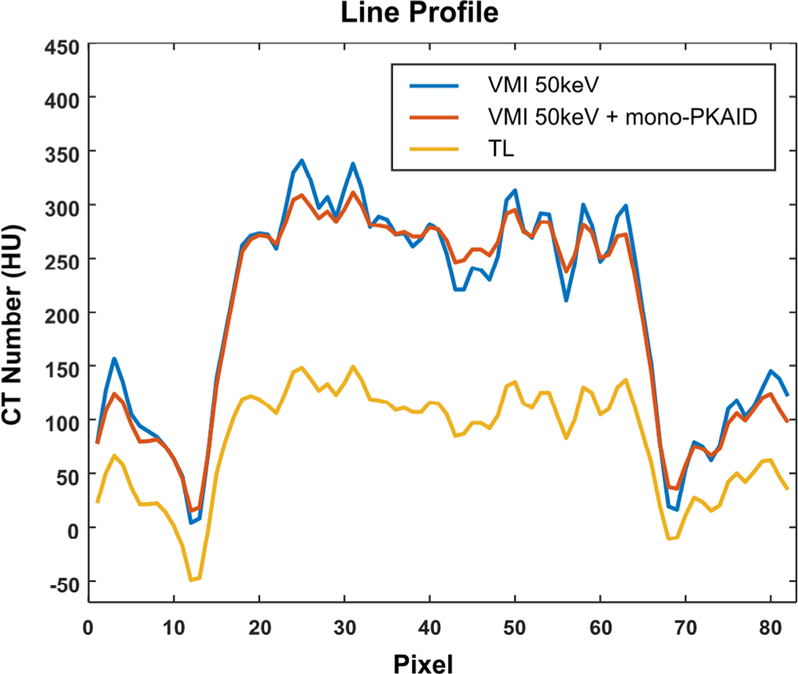

Examples of the 50 keV VMIs generated from the patient data acquired on the PCD-CT system before and after mono-PKAID processing are shown in figure 9, together with the corresponding TL image. Comparison between the 50 keV VMI (a) and TL image (c) shows that the 50 keV image improves iodine contrast, and consequently the visualization of anatomical regions perfused with iodine. However, it also suffers from noticeable noise amplification. In comparison, mono-PKAID is able to retain image contrast while reducing image noise. Table 3 lists the mean value and standard deviation measured from the ROIs located in liver parenchyma and inferior vena cava (circular ROI in figure 9). As shown in table 3, the mono-PKAID preserves the mean values of ROI measurements, while reducing the noise to a level comparable to the TL images. Table 3 also shows the iodine CNRs calculated from the original 50 keV image, the 50 keV VMI after mono-PKAID, and the TL images. The CNR was improved from 2.6 to 4.6 using mono-PKAID. For comparison, the CNR of the TL images was 0.9. Figure 10 compares the line profiles across the abdominal aorta in the original 50 keV image and that in the results of mono-PKAID. As shown in figure 10, the mono-PKAID reduces the image noise and preserves the boundary of abdominal aorta.

Figure 9.

(a) Example of 50 keV virtual mono-energetic images (VMI) from a patient with liver metastasis who underwent contrast enhanced CT exam on a whole-body PCD-CT system. (b) 50 keV VMI after processing using the proposed mono-PKAID. (c) The corresponding energy threshold-low (TL) image. Note the reduced image noise but preserved iodine contrast, sharpness and image texture in the results of mono-PKAID in (b) compared to the original VMI 50 keV image in (a). The circular ROIs used for CNR evaluation are also shown in (a). Window level/width (WL/WW) are adjusted to optimize the image contrast, with WL/WW = 40/300 HU for the TL image, WL/WW = 150/300 HU for VMIs.

Table 3.

ROI measurements from 50 keV VMI, before and after mono-PKAID processing, generated from the patient images acquired on a research whole-body PCD-CT system, as well as that from energy threshold-low images. The iodine CNR values for each case are also shown.

| Original VMI 50 keV | 50 keV + mono-PKAID | Energy threshold-low | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROI (liver parenchyma) | 203 ± 28 | 203 ± 16 | 103 ± 16 |

| ROI (inferior vena cava) | 277 ± 28 | 276 ± 15 | 118 ± 15 |

| Iodine CNR | 2.6 | 4.6 | 0.9 |

Figure 10.

Line profile across the abdominal aorta in the original 50 keV VMI generated from the patient data set acquired on PCD-CT and that in the 50 keV VMI after mono-PKAID. The line profile of the energy threshold low (TL) image is also shown, which is used as prior image for mono-PKAID. The location of the line profiles is indicated in figures 9(a)–(c).

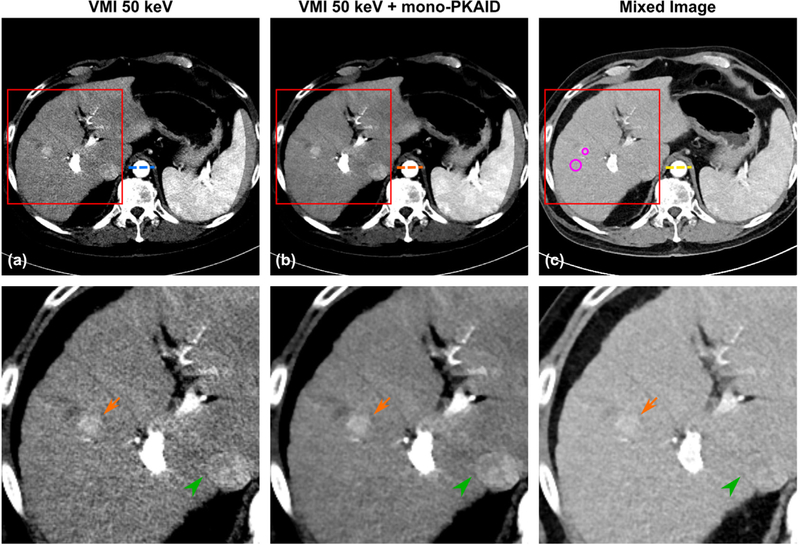

To demonstrate the compatibility of mono-PKAID with the conventional dual-energy CT systems, figure 11 shows an example of 50 keV VMI generated from a patient scan performed using a clinical abdominal dual-source dual-energy CT protocol, before and after processing with mono-PKAID. Figure 11 also shows the mixed image between tube A and tube B, which is used as the spectral prior image by mono-PKAID. Similar to the previous observations, the original 50 keV VMI (figure 11(a)) improves iodine contrast at the cost of increased image noise, compared to the mixed image in figure 11(c). The proposed mono-PKAID is able to reduce image noise while preserving iodine contrast. Note the better defined hyper-attenuating lesion and inferior vena cava (see arrows) in the results of mono-PKAID. The CNR of the hyper-enhancing lesion in each case was calculated from the ROI in figure 11 (see table 4 for ROI measurements), and are 3.0 for the original 50 keV image, 5.5 for the 50 keV with mono-PKAID, and 2.6 for the mixed image. The mono-PKAID improves CNR by 1.8-fold. The line profiles across the abdominal aorta before and after mono-PKAID are shown in figure 12, which shows reduced image noise and preserved object boundaries.

Figure 11.

Examples of 50 keV virtual monoenergetic images (VMI) generated from an abdominal patient scan performed on the clinical dual-source dual-energy CT system before (a) and after (b) mono-PKAID processing, as well as the mixed image between tube A and tube B (c). The ROIs used for CNR evaluation are shown as circles in (c). Note the reduced image noise in liver parenchyma region in (b) compared to the original 50 keV in (a), as well as the improved visibility of the hyper-enhancing lesion (arrow) and better defined inferior vena cava (arrow head). Window level/width (WL/WW) are adjusted to optimize image contrast, with WL/WW = 40/300 HU for the mixed image, WL/WW = 150/300 HU for VMIs.

Table 4.

ROI measurements from 50 keV VMI, before and after mono-PKAID processing, generated from the in vivo patient images acquired on a clinical dual-source dual-energy CT system, as well as that from the mixed image between tube A and tube B.

| Original VMI 50 keV | 50 keV + mono-PKAID | Mixed image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROI (liver parenchyma) | 145 ± 19 | 145 ± 10 | 92 ± 9 |

| ROI (liver lesion) | 202 ± 23 | 200 ± 14 | 115 ± 11 |

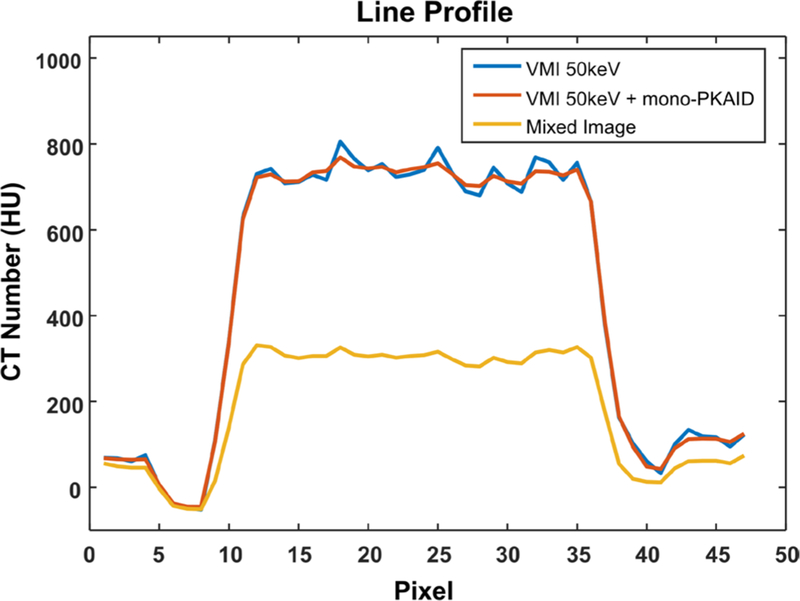

Figure 12.

Line profile across the abdominal aorta in the original VMI 50 keV images and that in the results of mono-PKAID. Images were generated from a patient data set acquired on a clinical dual-source dual-energy CT system. The line profile of the mixed image between tube A and tube B is also shown, which is used as prior image for mono-PKAID. The location of the line profiles is indicated in figures 11(a)–(c).

4. Discussion

In this work, we described a denoising framework (mono-PKAID) that utilizes the spatio-spectral data redundancy between the multi-energy CT images and the VMIs to improve the iodine CNR in the low-energy VMIs. Phantom and patient data demonstrate that the mono-PKAID framework does not cause deviation of CT number from the original VMI, and is able to preserve spatial resolution and noise texture while denoising the low-energy VMIs and improving iodine CNR. With the proposed method, VMIs at lower keV take full advantage of higher contrast without substantially increasing image noise. These observations are confirmed in patient data acquired on a research whole-body PCD-CT and a clinical dual-source dual-energy CT system, which demonstrate that mono-PKAID can reduce image noise, improve CNR in anatomical regions with iodine perfusion, potentially enhancing visibility of focal liver lesions.

We have demonstrated the proposed method using Mono + (Siemens Healthcare GmbH) in this work. However, the mono-PKAID is a generic approach that directly works with image data and does not require access to raw projection data. It can be applied to images generated from any VMI tool, either supplied by commercial vendors or research labs. It can also be applied to different multi-energy CT implementations, such as split-beam, dual-layer detector, or fast kV switching multi-energy CT, in addition to the two platforms (dual source CT and PCD-CT) investigated in this study. The compatibility of the proposed method with commercially available processing packages makes it a versatile technique that can be used in a clinical environment. Although some vendor-supplied VMI tools such as Mono + already apply certain noise reduction algorithm (Grant et al 2014), the application of the proposed mono-PKAID can further improve iodine CNR by ~1.8 times through exploiting the spatiospectral data redundancy, as demonstrated with various phantom and patient results in this work.

Although the 40 keV VMIs exhibit higher iodine CNR compared to the other higher keV images, they usually suffer from more noticeable image artifacts and patchy appearance. Therefore, they are not currently used in our practice (Hanson et al 2018). Applying mono-PKAID to these images would preserve the undesirable artifacts and appearance. On the other hand, the 50 keV VMIs offer improved iodine CNR compared to the conventional single energy CT, while suppressing these artifacts. They are more favored by radiologists in general, and are therefore the focus of this study. Since the proposed mono-PKAID focuses on noise reduction and iodine CNR improvement but does not attempt to correct for artifacts due to multi-energy processing, the existing image artifacts inherited from the original VMIs are not eliminated using mono-PKAID. Another limitation of this technique is that it relies on the noise properties of the prior image, and therefore achieving noise levels lower than the prior image is not straightforward. In cases of noisy prior, an edge-preserving spatial filter could be employed to minimize noise in the prior image volume, before incorporating it in the mono-PKAID workflow (Lauzier and Chen 2013).

Mono-PKAID may be beneficial for clinical applications where higher iodine CNR is desirable, such as visualization and diagnosis of liver lesions, detection of carotid stenosis in CT angiography, and pulmonary circulation imaging and detection of pulmonary embolism. In addition, the improved CNR offered by mono-PKAID for VMIs can potentially allow a reduction in the amount of contrast media administrated in patients with chronic renal insufficiency or undergoing intra-arterial vascular procedures.

The proposed framework is compatible with parallel processing and can potentially be accelerated via the use of high-performance graphic processing units (GPU). The current implementation on Matlab environment (Matlab 9.1, MathWorks, Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, USA) takes about 2 min to process a single 512 × 512 image matrix on a personal computer with a 6-core 3.4 GHz CPU and 16 GB memory. The current Matlab implementation based on CPU is relatively slow, which is a limitation of this method. We expect the computation time to be considerably reduced by implementing it on GPU platform.

5. Conclusion

In this work, we developed an image-domain noise-reduction framework called mono-PKAID that exploits the spatio-spectral data redundancy between the multi-energy CT image and VMIs to denoise the low-energy VMIs. Various phantom and in vivo experiments demonstrated that the proposed technique was able to improve iodine CNR compared to the original low-energy VMIs, while preserving spatial resolution and noise texture.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this article was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 EB016966 and C06 RR018898. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

References

- Albrecht MH et al. 2016a. Advanced image-based virtual monoenergetic dual-energy CT angiography of the abdomen: optimization of kiloelectron volt settings to improve image contrast Eur. Radiol 26 1863–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht MH, Trommer J, Wichmann JL, Scholtz JE, Martin SS, Lehnert T, Vogl TJ and Bodelle B 2016b. Comprehensive comparison of virtual monoenergetic and linearly blended reconstruction techniques in third-generation dual-source dual-energy computed tomography angiography of the thorax and abdomen Invest. Radiol 51 582–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida IP, Schyns LE, Ollers MC, van Elmpt W, Parodi K, Landry G and Verhaegen F 2017. Dual-energy CT quantitative imaging: a comparison study between twin-beam and dual-source CT scanners Med. Phys 44 171–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmi R, Naveh G and Altman A 2005. Material separation with dual-layer CT IEEE Nuclear Science Symp. 4 1876–8 [Google Scholar]

- Caruso D, De Cecco CN, Schoepf UJ, Schaefer AR, Leland PW, Johnson D, Laghi A and Hardie AD 2017. Can dual-energy computed tomography improve visualization of hypoenhancing liver lesions in portal venous phase? Assessment of advanced image-based virtual monoenergetic images Clin. Imaging 41 118–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S et al. 2018. Utility of dual-energy CT-based monochromatic imaging in the assessment of myocardial delayed enhancement in patients with cardiomyopathy Radiology 287 442–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GH, Tang J and Hsieh J 2009. Temporal resolution improvement using PICCS in MDCT cardiac imaging Med. Phys 36 2130–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GH, Tang J and Leng S 2008. Prior image constrained compressed sensing (PICCS): a method to accurately reconstruct dynamic CT images from highly undersampled projection data sets Med. Phys 35 660–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coursey CA, Nelson RC, Boll DT, Paulson EK, Ho LM, Neville AM, Marin D, Gupta RT and Schindera ST 2010. Dual-energy multidetector CT: how does it work, what can it tell us, and when can we use it in abdominopelvic imaging? Radiographics 30 1037–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferda J, Novak M, Mirka H, Baxa J, Ferdova E, Bednarova A, Flohr T, Schmidt B, Klotz E and Kreuzberg B 2009. The assessment of intracranial bleeding with virtual unenhanced imaging by means of dual-energy CT angiography Eur. Radiol 19 2518–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flohr TG et al. 2006. First performance evaluation of a dual-source CT (DSCT) system Eur. Radiol 16 256–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frellesen C et al. 2016. Noise-optimized advanced image-based virtual monoenergetic imaging for improved visualization of lung cancer: comparison with traditional virtual monoenergetic imaging Eur. J. Radiol 85 665–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook KN, Guimaraes LS, Murthy NS, Black DF, Bongartz T, Manek NJ, Leng S, Fletcher JG and McCollough CH 2011. Identification of intraarticular and periarticular uric acid crystals with dual-energy CT: initial evaluation Radiology 261 516–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KL, Flohr TG, Krauss B, Sedlmair M, Thomas C and Schmidt B 2014. Assessment of an advanced image-based technique to calculate virtual monoenergetic computed tomographic images from a dual-energy examination to improve contrast-to-noise ratio in examinations using iodinated contrast media Invest. Radiol 49 586–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutjahr R, Halaweish AF, Yu Z, Leng S, Yu L, Li Z, Jorgensen SM, Ritman EL, Kappler S and McCollough CH 2016. Human imaging with photon counting-based computed tomography at clinical dose levels: contrast-to-noise ratio and cadaver studies Invest. Radiol 51 421–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson GJ et al. 2018. Low kV versus dual-energy virtual monoenergetic CT imaging for proven liver lesions: what are the advantages and trade-offs in conspicuity and image quality? A pilot study Abdom. Radiol 43 1404–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalender WA, Perman WH, Vetter JR and Klotz E 1986. Evaluation of a prototype dual-energy computed tomographic apparatus. 1. Phantom studies Med. Phys 13 334–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisz K, Rassouli N, Dhanantwari A, Jordan D and Rajiah P 2018. Noise characteristics of virtual monoenergetic images from a novel detector-based spectral CT scanner Eur. J. Radiol 98 118–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappler S, Glasser F, Janssen S, Kraft E and Reinwand M 2010. A research prototype system for quantum-counting clinical CT Proc. SPIE 7622 76221Z [Google Scholar]

- Kappler S, Hannemann T, Kraft E, Kreisler B, Niederloehner D, Stierstorfer K and Flohr T 2012. First results from a hybrid prototype CT scanner for exploring benefits of quantum-counting in clinical CT Proc. SPIE 8313 83130X [Google Scholar]

- Korn A, Bender B, Thomas C, Danz S, Fenchel M, Nagele T, Heuschmid M, Ernemann U and Hauser TK 2011. Dual energy CTA of the carotid bifurcation: advantage of plaque subtraction for assessment of grade of the stenosis and morphology Eur. J. Radiol 80 E120–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauzier PT and Chen GH 2013. Characterization of statistical prior image constrained compressed sensing (PICCS): II. Application to dose reduction Med. Phys 40 021902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauzier PT, Tang J and Chen GH 2012. Prior image constrained compressed sensing: implementation and performance evaluation Med. Phys 39 66–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leithner D et al. 2017. Virtual monoenergetic imaging and iodine perfusion maps improve diagnostic accuracy of dual-energy computed tomography pulmonary angiography with suboptimal contrast attenuation Investigative Radiol. 52 659–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng S, Rajendran K, Gong H, Zhou W, Halaweish AF, Henning A, Kappler S, Baer M, Fletcher JG and McCollough CH 2018. 150 μm spatial resolution using photon-counting detector computed tomography technology: technical performance and first patient images Invest. Radiol 53 655–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng S, Tang J, Zambelli J, Nett B, Tolakanahalli R and Chen GH 2008. High temporal resolution and streak-free four-dimensional cone-beam computed tomography Phys. Med. Biol 53 5653–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng S, Yu L, Fletcher JG and McCollough CH 2015. Maximizing iodine contrast-to-noise ratios in abdominal CT imaging through use of energy domain noise reduction and virtual monoenergetic dual-energy CT Radiology 276 562–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng S, Yu L, Wang J, Fletcher JG, Mistretta CA and McCollough CH 2011. Noise reduction in spectral CT: reducing dose and breaking the trade-off between image noise and energy bin selection Med. Phys 38 4946–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Yu L, Trzasko JD, Lake DS, Blezek DJ, Fletcher JG, McCollough CH and Manduca A 2014. Adaptive nonlocal means filtering based on local noise level for CT denoising Med. Phys 41 011908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Jinzaki M, Tanami Y, Ueno A, Yamada M and Kuribayashi S 2011. Virtual monochromatic spectral imaging with fast kilovoltage switching: improved image quality as compared with that obtained with conventional 120 kVp CT Radiology 259 257–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollough C, Leng S, Yu L and Fletcher JG 2015. Dual-and multi-energy computed tomography: principles, technical approaches, and clinical applications Radiology 276 637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechlem K, Allner S, Ehn S, Mei K, Braig E, Munzel D, Pfeiffer F and Noel PB 2017. A post-processing algorithm for spectral CT material selective images using learned dictionaries Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 3 025009 [Google Scholar]

- Muenzel D et al. 2017. Spectral photon-counting CT: initial experience with dual-contrast agent K-edge colonography Radiology 283 723–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocedal J and Wright SJ 2006. Numerical Optimization (New York: Springer; ) [Google Scholar]

- Patel BN, Farjat A, Schabel C, Duvnjak P, Mileto A, Ramirez-Giraldo JC and Marin D 2018. Energy-specific optimization of attenuation thresholds for low-energy virtual monoenergetic images in renal lesion evaluation Am. J. Roentgenol 210 W205–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourmorteza A, Symons R, Sandfort V, Mallek M, Fuld MK, Henderson G, Jones EC, Malayeri AA, Folio LR and Bluemke DA 2016. Abdominal imaging with contrast-enhanced photon-counting CT: first human experience Radiology 279 239–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primak AN, Fletcher JG, Vrtiska TJ, Dzyubak OP, Lieske JC, Jackson ME, Williams JC and McCollough CH 2007. Noninvasive differentiation of uric acid versus non-uric acid kidney stones using dual-energy CT Acad. Radiol. 14 1441–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Z, Huang S, Nett B, Tang J, Yang K, Boone J and Chen G 2010. Dramatic noise reduction and potential radiation dose reduction in breast cone-beam CT imaging using prior image constrained compressed sensing (PICCS) Med. Phys 37 3443 [Google Scholar]

- Shuman WP, Green DE, Busey JM, Mitsumori LM, Choi E, Koprowicz KM and Kanal KM 2014. Dual-energy liver CT: effect of monochromatic imaging on lesion detection, conspicuity, and contrast-to-noise ratio of hypervascular lesions on late arterial phase Am. J. Roentgenol 203 601–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siewerdsen JH, Cunningham IA and Jaffray DA 2002. A framework for noise-power spectrum analysis of multidimensional images Med. Phys 29 2655–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stierstorfer K, Rauscher A, Boese J, Bruder H, Schaller S and Flohr T 2004. Weighted FBP—a simple approximate 3D FBP algorithm for multislice spiral CT with good dose usage for arbitrary pitch Phys. Med. Biol 49 2209–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao S, Rajendran K, McCollough CH and Leng S 2018. Material decomposition with prior knowledge aware iterative denoising (MD-PKAID) Phys. Med. Biol 63 195003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemink MJ, Persson M, Pourmorteza A, Pelc NJ and Fleischmann D 2018. Photon-counting CT: technical principles and clinical prospects Radiology 289 293–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Niu T, Tang S, Yang X, Kadom N and Tang X 2018. Content-oriented sparse representation (COSR) for CT denoising with preservation of texture and edge Med. Phys 45 4942–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Langan DA, Wu X, Pack JD, Benson TM, Tkaczky JE and Schmitz AM 2009. Dual energy CT via fast kVp switching spectrum estimation SPIE Medical Imaging (International Society for Optics and Photonics) p 72583T [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Leng S and McCollough CH 2012. Dual-energy CT-based monochromatic imaging Am. J. Roentgenol 199 S9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu ZC et al. 2016a. Evaluation of conventional imaging performance in a research whole-body CT system with a photon-counting detector array Phys. Med. Biol 61 1572–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, Leng S, Li Z, Halaweish AF, Kappler S, Ritman EL and McCollough CH 2016b. How low can we go in radiation dose for the data-completion scan on a research whole-body photon-counting computed tomography system J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr 40 663–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu ZC, Leng S, Li ZB and McCollough CH 2016c. Spectral prior image constrained compressed sensing (spectral PICCS) for photon-counting computed tomography Phys. Med. Biol 61 6707–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]