Reductive cross-coupling of primary amines and alkyl halides goes through a radical change.

Abstract

The reductive cross-coupling of sp3-hybridized carbon centers represents great synthetic values and insurmountable challenges. In this work, we report a nickel-catalyzed deaminative cross-electrophile coupling reaction to construct C(sp)─C(sp3), C(sp2)─C(sp3), and C(sp3)─C(sp3) bonds. A wide range of coupling partners including aryl iodides, bromoalkynes, or alkyl bromides are stitched with alkylpyridinium salts that derived from the corresponding primary amines. The advantages of this methodology are showcased in the two-step synthesis of the key lactonic moiety of (+)-compactin and (+)-mevinolin. The one-pot procedure without isolation of alkylpyridinium tetrafluoroborate salt is also proven to be successful. This cross-coupling strategy of two electrophiles provides a highly valuable vista for the convenient installation of alkyl substituents and late functionalizations of sp3 carbons.

INTRODUCTION

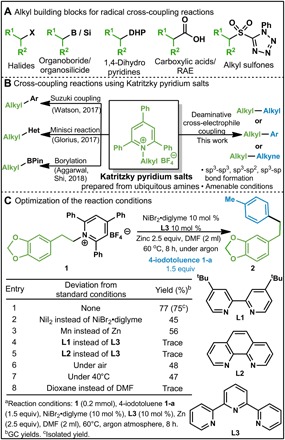

Transition metal–catalyzed radical cross-coupling has become one of the most fundamental transformations in materials science, biology, and organic chemistry. Remarkable progress has been made in this research area during the past several decades, providing a complementary technique to the venerable Heck, Suzuki, and Negishi reactions (1–3). However, forging sp3-hybridized carbon centers remains a great challenge mainly due to the weak nucleophilic reactivity of sp3 carbon centers and their innate difficulties in coordination with metals (4–7). In recent years, various alkyl radical precursors including halides (4, 8–11), silicones (12), dihydropyridine (13), carboxylic acids (14–16), sulfones (17), and others (18–20) have been used for radical cross-coupling reactions (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Electrophiles for cross-coupling reactions.

(A) Sources of alkyl electrophiles for radical cross-coupling reactions. RAE, redox-active esters. (B) Examples of redox-active Katritzky salts in recent years. (C) Optimization of deaminative cross-electrophile coupling with 1-a.

Primary amines are prevalent in biologically active natural products and drug molecules. As inexpensive and abundant building blocks, amines are broadly used in synthetic chemistry (21, 22). However, the use of amines as alkyl electrophile precursors for radical cross-electrophile coupling transformations is yet to be described. Notably, Watson and co-workers (23, 24) recently reported elegant Suzuki-Miyaura and Negishi cross-coupling reactions using primary amines as alkyl sources through C─N activation. Their strategy consisted of conversion of primary amines to redox-active alkylpyridinium salts (Katritzky pyridium salts), which were reacted with arylboronic acids or organozinc reagents via a single-electron transfer process (Fig. 1B). The redox-active alkylpyridinium salts were subsequently used as alkyl halide surrogates in a photo-induced Minisci reaction by Glorious and co-workers (25). Recently, Aggarwal, Shi, and Glorious (26–28) reported deaminative borylation of Katritzky pyridium salts using bis-(catecholato)diboron. Gryko (29) have developed a Giese-type deaminative alkynylation and alkenylation using the corresponding sulfones. Xiao and co-workers (30) developed a visible light–initiated deaminative alkyl-Heck–type reaction between Katritzky salts derived from aliphatic primary amines and alkenes, which afforded the products in good yields. In these examples, bond formation is achieved by the reaction between nucleophilic reagents with the Katritzky salts derived from primary amines. However, the use of amines as alkyl electrophile precursors for radical cross-electrophile coupling transformations is yet to be described, especially direct construction of C(sp3)─C(sp3) and C(sp3)─C(sp) bonds. On the other hand, the Doyle group developed a Ni-catalyzed enantioselective cross-electrophile coupling reaction of styrenyl aziridines with aryl iodides (31). Following our keen interest in cross-electrophile coupling reactions (32), we envisaged whether the coupling of primary amines with electrophilic halides could be achieved by the mediation of the corresponding Katritzky salts. Such approach occupies a clear edge over conventional cross-coupling procedures in avoiding air- and moisture-sensitive organometallic reagents. Here, we report the first Ni-catalyzed cross-electrophile coupling between alkylpyridinium salts and halides through C─N bond activation (Fig. 1B).

RESULTS

We began our study with evaluation of the conditions for this envisioned cross-coupling reaction between 4-iodotoluene 1-a and pyridinium salts 1 derived from 2-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)ethan-1-amine and 2,4,6-triphenylpyrylium tetrafluoroborate. The desired product was obtained in 77% yield with 10 mole percent (mol %) NiBr2•diglyme catalyst and 10 mol % tridentate ligand L3 in the presence of 2.5 equivalents (equiv) of zinc at 60°C under argon atmosphere (entry 1; Fig. 1C). When NiI2 instead of NiBr2•diglyme was used as a catalyst, the yield decreased markedly to 45% (entry 2). Reductive metal species were found to be important for this transformation, as evidenced by the low yield (56%) obtained when using Mn as reducing reagent (entry 3). Bidentate ligands L1 and L2 led to only trace amount of product 3a, indicating that the additional coordinating site of L3 was crucial for achieving reactivity (entries 4 and 5). Further evaluation of the reaction conditions by lowering the reaction temperature, performing the reaction under air or changing the solvent to dioxane did not result in any improvement on the yield (entries 6 to 8).

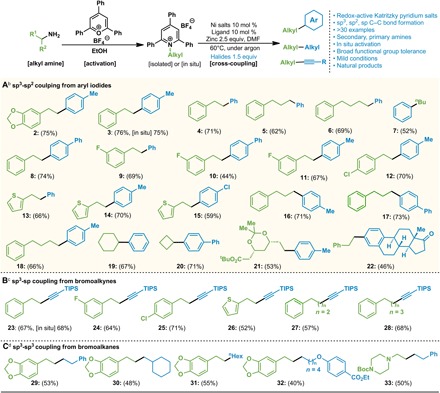

Under the optimized reaction conditions, we explored the substrate generality of this cross-electrophile coupling with various aryl iodides and tetrafluoroborate pyridinium salts (Fig. 2). Aryl iodides with electron-withdrawing and electron-donating substituents were tolerated in the reaction. The methyl (2 and 3)–, phenyl (8)–, and p-Cl-phenyl (15)–substituted coupling products were obtained in good yields. Different alkyl substituents on the pyridinium salts performed equally well, and the desired products were obtained in 44 to 70% yields (9 to 12). Thiophene-substituted pyridinium salts also proceeded smoothly (13 to 15). Extending the alkyl chains did not influence the reaction performance (5, 16, 17 and 6, 18). Secondary amines such as cyclohexyl amine and cyclobutyl amine could serve as electrophiles (19 and 20) to afford the secondary alkyl-substituted arenes in 67 and 71% yields, respectively. Benzylamine did not react under the optimized conditions, presumably due to the stability of benzyl radical. During the preparation of pyridinium tetrafluoroborate salts, we could not obtain several substrates by simple filtration and an additional purification step was required. This limitation prompted us to investigate the reaction in a one-pot manner without isolation of Katritzky salts. When the primary amine was activated in situ and treated to the standard conditions, the cross-coupled product 3 was achieved in 75% yield by in situ reaction and 76% yield by the standard conditions.

Fig. 2. Substrate scope of the reaction.

aIsolated yields. bCondition A: Pyridinium salts (0.2 mmol), NiBr2•diglyme (0.02 mmol), L3 (0.02 mmol), zinc flake (−325 mesh, 99.9%) (0.5 mmol), aryl iodide 2 (0.3 mmol), and DMF (2.0 ml), 60°C. cCondition B: Pyridinium salts (0.2 mmol), Ni(acac)2 (0.02 mmol), L1 (0.02 mmol), zinc flake (−325 mesh, 99.9%) (0.5 mmol), bromoalkynes (0.3 mmol), and DMF (1.0 ml), 60°C. dCondition C: Pyridinium salts (0.2 mmol), Ni(COD)2 (0.04 mmol), L1 (0.04 mmol), tetrabutylammonium iodide (0.1 mmol), zinc flake (−325 mesh, 99.9%) (0.5 mmol), bromoalkanes (0.8 mmol), and dimethylamine (1.0 ml), 60°C.

Next, we examined whether alkynyl halides could also participate in this Ni-catalyzed cross-electrophile coupling reaction to construct C(sp3)─C(sp) bonds. Such transformations have never been explored with primary amines (23–30). After careful screening of the nickel catalysts and ligands, we found that the reaction of (bromoethynyl)triisopropylsilane and 1-phenethyl-2,4,6-triphenylpyridinium tetrafluoroborate with the combination of Ni(acac)2/dtbpy L1 as catalyst afforded alkyne 23 in 67% yield (68% from the in situ reaction). Unlike the reaction of iodobenzene electrophiles, bidentate bipyridyl ligand exhibited good catalytic activity for this reaction. We also attempted introducing additives in the reaction mixture, and no improvement was observed (see the Supplementary Materials for the details of the optimization of the reaction conditions). As shown in Fig. 2B, triisopropylsilyl (TIPS)–substituted bromoethyne reacted smoothly with a series of tetrafluoroborate pyridinium salts under standard conditions to afford the corresponding alkyl-substituted alkynes in 52 to 71% yields. Note that 2-arylethylamine–, 3-phenylpropylamine–, 4-phenylbutylamine–, and 2-theinylethylamine–derived pyridinium salts were suitable substrates for this reaction.

Despite the coupling of aryl iodides, alkyl bromides were tested with alkylpyridinium salts to form the C(sp3)─C(sp3) bond (Fig. 2C). Phenylethyl bromide reacted smoothly to furnish the corresponding product 29 in 53% yield. The reaction between phenylethyl bromide and the salt of piperazine proceeded to give the product 33 in 50% yield. The substrates bearing long alkyl chain and cyclohexyl also afforded the desired products 30 and 31 in 48 and 55% yield, respectively. Notably, a linear alkyl bromide bearing an ester was tolerated in this reaction to afford the product 32 in moderate yield (40%). To further demonstrate the utility of the Ni-catalyzed cross-electrophile coupling reaction, we attempted Katritzky pyridinium salts derived from several natural bioactive amines. The amine derivative of atorvastatin precursor was coupled with 4-iodotoluene under the standard conditions to afford 21 in 53% yield. Moreover, we demonstrated that the estrone surrogate aryl iodide was converted to 22 in 46% yield.

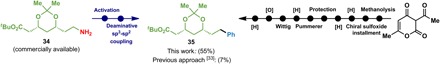

In addition, this strategy has been applied to the synthesis of the lactonic moiety of (+)-compactin and (+)-mevinolin, which previously required 10 steps to synthesize (Fig. 3) (33). Starting from commercially available 34, a two-step sequence was developed to install the phenyl group to furnish the key intermediate 35 in 55% yield.

Fig. 3. Synthesis of the precursor to the key lactonic moiety in (+)-compactin and (+)-mevinolin.

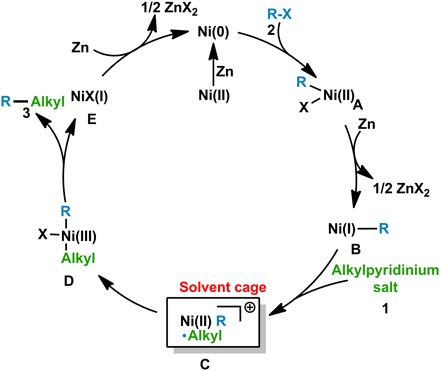

We carried out further mechanistic studies to gain insight into this transformation. A mixture of iodobenzene and zinc flake (325 mesh) in N,N′-dimethylformamide (DMF) was heated to 60°C for 8 hours, and no reaction occurred (see the Supplementary Materials). The full recovery of iodobenzene suggested that the reaction may proceed through a single-electron transfer process rather than generating organozinc species. The reaction of 2-phenylethylamine trifluoromethanesulfonate with iodobenzene did not occur under the standard conditions, indicating that tetrafluoroborate pyridinium salt is irreplaceable in the reaction. The addition of 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO) suppressed this reaction, and only 27% yield of product 2 was obtained (71% under the standard conditions). In addition, the trapped alkyl radical TEMPO adduct was detected by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), which indicates that a radical process is involved (see the Supplementary Materials).

DISCUSSION

On the basis of the above control experiments and previous reports (23–30, 34), a radical cross-coupling pathway via C─N bond cleavage and reductive elimination was proposed for this reaction (Fig. 4). Initially, reduction of the Ni(II) salt by Zn affords the active Ni(0) catalyst, which underdoes oxidative addition into the C─X bond of halide 2 to give the intermediate R-Ni(II)X A (35). A is subsequently reduced by zinc to R-Ni(I) intermediate B, which undergoes a second oxidative addition step to pyridinium 1. This step may proceed via stepwise single-electron transfer with the possibility of radical trapping within a solvent cage to afford intermediate C before generation of R-Ni(III)(alkyl)X intermediate D (36). Reductive elimination from D forms the desired product 3 and nickel(I) specie E, which is reduced by zinc to facilitate the next catalytic cycle (35).

Fig. 4. Proposed mechanism of the Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction.

In summary, we have described a new cross-electrophile coupling reaction using alkyl amine–derived alkylpyridinium tetrafluoroborate salts as a coupling partner. The reaction was conducted under mild conditions and tolerated a wide range of substrates including highly reactive alkynyl bromides. Furthermore, an in situ reaction without isolation of alkylpyridinium tetrafluoroborate salt proved to be successful, underscoring the great value of this reaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General information

All manipulations were carried out under argon atmosphere. Commercially available reagents were used as received without purification. Column chromatography was carried out on silica gel (300 to 400 mesh). Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on glass plates of Silica Gel GF254 with detection by ultraviolet. 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE 400 MHz/500 MHz spectrometer with trimethylsilyl (TMS) as reference. Infrared spectra were obtained on an Agilent Cary 630 instrument on a diamond plate using attenuated total reflection. High-resolution MS was conducted on an Agilent 6540 Q-TOF LC-MS equipped with an ESI probe operating in positive ion mode.

General procedure for the Ni-catalyzed cross-electrophile coupling of pyridinium salts with aryl iodides

An oven-dried 25-ml Schlenk tube equipped with a stir bar was charged with redox-active pyridinium salts 1 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), NiBr2•diglyme (0.02 mmol), 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine (0.02 mmol), zinc flake (−325 mesh, 99.9%) (0.5 mmol), and aryl iodide (0.3 mmol) (if solid). The tube was then evacuated and back-filled with argon (three times). Aryl iodide (0.3 mmol; if liquid) and anhydrous DMF (2 ml) were added under argon. The resulting mixture was allowed to stir for 8 hours under argon atmosphere at 60°C (oil bath). The reaction mixture was quenched with 1 M HCl and extracted with EtOAc. The organic layer was washed with water and brine and dried over Na2SO4. The organic layer was concentrated under vacuum by rotary evaporator in a water bath at 45°C. Flash column chromatography or preparative TLC provided the product.

General procedure for the Ni-catalyzed cross-electrophile coupling of pyridinium salts with bromoalkynes

An oven-dried 25-ml Schlenk tube equipped with a stir bar was charged with redox-active pyridinium salts 1 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), Ni(acac)2 (0.02 mmol), 4-4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine (0.02 mmol), and zinc flake (−325 mesh, 99.9%) (0.5 mmol). The tube was then evacuated and back-filled with argon (three times). Anhydrous DMF (1 ml) and bromoalkynes (0.3 mmol) were added under argon. The resulting mixture was allowed to stir for 8 hours under argon atmosphere at 60°C (oil bath). The reaction mixture was quenched with water and extracted with EtOAc. The organic layer was washed with water and brine and dried over Na2SO4. The organic layer was concentrated under vacuum by rotary evaporator in a water bath at 45°C. Flash column chromatography provided the product.

General procedure for the Ni-catalyzed cross-electrophile coupling of pyridinium salts with bromoalkanes

An oven-dried 25-ml Schlenk tube equipped with a stir bar was charged with redox-active pyridinium salts 1 (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), Ni(cod)2 (0.04 mmol), 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine (0.04 mmol), tetra-n-butylammonium iodide (0.1 mmol), and zinc flake (−325 mesh, 99.9%) (0.5 mmol). The tube was then evacuated and back-filled with argon (three times). Anhydrous dimethylamine (1 ml) and bromoalkanes (0.8 mmol) were added under argon. The resulting mixture was allowed to stir for 8 hours under argon atmosphere at 60°C (oil bath). The reaction mixture was quenched with water and extracted with EtOAc. The organic layer was washed with water and brine and dried over Na2SO4. The organic layer was concentrated under vacuum by rotary evaporator in a water bath at 45°C. Flash column chromatography provided the product.

General procedure for the in situ activation of primary amines

Cross-coupling with iodobenzene

A culture tube was charged with primary amines (0.1 mmol) and 2,4,6-triphenylpyrylium tetrafluoroborate (1.2 equiv). EtOH (1.0 ml) was added, and the culture tube was sealed. The mixture was stirred at 100°C overnight. After that, EtOH was removed under vacuum. NiBr2•diglyme (0.02 mmol), 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine (0.02 mmol), zinc flake (−325 mesh, 99.9%) (0.5 mmol), iodobenzene (0.3 mmol), and anhydrous DMF (2 ml) were added under argon. The resulting mixture was allowed to stir for 8 hours under argon atmosphere at 60°C (oil bath). The reaction mixture was quenched with 1 M HCl and extracted with EtOAc. The organic layer was washed with water and brine and dried over Na2SO4. The organic layer was concentrated under vacuum by rotary evaporator in a water bath at 45°C. Flash column chromatography or preparative TLC provided the product.

Cross-coupling with bromoalkynes

A culture tube was charged with 0.1 mmol primary amines (1.0 equiv) and 2,4,6-triphenylpyrylium tetrafluoroborate (1.2 equiv). EtOH (1.0 ml) was added, and the mixture was refluxed overnight. After that, EtOH was removed under vacuum. Ni(acac)2 (0.02 mmol), 4-4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine (0.02 mmol), and zinc flake (−325 mesh, 99.9%) (0.5 mmol) were added. The tube was then evacuated and back-filled with argon (three times). Anhydrous DMF (1 ml) and bromoalkynes (0.3 mmol) were added under argon. The resulting mixture was allowed to stir for 8 hours under argon atmosphere at 60°C (oil bath). The reaction mixture was quenched with water and extracted with EtOAc. The organic layer was washed with water and brine and dried over Na2SO4. The organic layer was concentrated under vacuum by rotary evaporator in a water bath at 45°C. Flash column chromatography provided the product.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Collaborative Innovation Center of Advanced Microstructures and the Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Photonic and Electronic Materials at Nanjing University for support. Funding: We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 21761132021, 21772085, 21531004, and 21820102004). Author contributions: Methodology: S.N.; investigation: S.N., C.-X.L., and Y.M.; writing, reviewing, and editing: S.N., J.H., and Y.W.; supervision: J.H., Y.W., H.Y., and Y.P. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/6/eaaw9516/DC1

Table S1. Optimization of cross-coupling with bromoalkynes.

Table S2. Optimization of cross-coupling with alkyl bromides.

Characterization data and NMR spectra of the cross-coupling products 2 to 35.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Yan M., Lo J. C., Edwards J. T., Baran P. S., Radicals: Reactive intermediates with translational potential. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12692–12714 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yi H., Zhong G., Wang H., Huang Z., Wang J., Singh A. K., Lei A., Recent advances in radical C–H activation/radical cross-coupling. Chem. Rev. 117, 9016–9085 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaga A., Chiba S., Engaging radicals in transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling with alkyl electrophiles: Recent advances. ACS Catal. 7, 4697–4706 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudolph A., Lautens M., Secondary alkyl halides in transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 2656–2670 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jana R., Pathak T. P., Sigman M. S., Advances in transition metal (Pd,Ni,Fe)-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions using alkyl-organometallics as reaction partners. Chem. Rev. 111, 1417–1492 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu G. C., Transition-metal catalysis of nucleophilic substitution reactions: A radical alternative to SN1 and SN2 processes. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 692–700 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frisch A. C., Beller M., Catalysts for cross-coupling reactions with non-activated alkyl halides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 674–688 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Netherton M. R., Fu G. C., Nickel-catalyzed cross-couplings of unactivated alkyl halides and pseudohalides with organometallic compounds. Adv. Synth. Catal. 346, 1525–1532 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dudnik A. S., Fu G. C., Nickel-catalyzed coupling reactions of alkyl electrophiles, including unactivated tertiary halides, to generate carbon-boron bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 10693–10697 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang Y., Fu G. C., Stereoconvergent Negishi arylations of racemic secondary alkyl electrophiles: Differentiating between a CF3 and an alkyl group. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 9523–9526 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bose S. K., Fucke K., Liu L., Steel P. G., Marder T. B., Zinc-catalyzed borylation of primary, secondary and tertiary alkyl halides with alkoxy diboron reagents at room temperature. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 1799–1803 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jouffroy M., Primer D. N., Molander G. A., Base-free photoredox/nickel dual-catalytic cross-coupling of ammonium alkylsilicates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 475–478 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakajima K., Nojima S., Nishibayashi Y., Nickel-and photoredox-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of aryl halides with 4-alkyl-1,4-dihydropyridines as formal nucleophilic alkylation reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 14106–14110 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston C. P., Smith R. T., Allmendinger S., MacMillan D. W. C., Metallaphotoredox-catalysed sp3-sp3 cross-coupling of carboxylic acids with alkyl halides. Nature 536, 322–325 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qin T., Cornella J., Li C., Malins L. R., Edwards J. T., Kawamura S., Maxwell B. D., Eastgate M. D., Baran P. S., A general alkyl-alkyl cross-coupling enabled by redox-active esters and alkylzinc reagents. Science 352, 801–805 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ni S., Garrido-Castro A. F., Merchant R. R., de Gruyter J. N., Schmitt D. C., Mousseau J. J., Gallego G. M., Yang S., Collins M. R., Qiao J. X., Yeung K. S., Langley D. R., Poss M. A., Scola P. M., Qin T., Baran P. S., A general amino acid synthesis enabled by innate radical cross-coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 14560–14565 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merchant R. R., Edwards J. T., Qin T., Kruszyk M. M., Bi C., Che G., Bao D. H., Qiao W., Sun L., Collins M. R., Fadeyi O. O., Gallego G. M., Mousseau J. J., Nuhant P., Baran P. S., Modular radical cross-coupling with sulfones enables access to sp3-rich (fluoro)alkylated scaffolds. Science 360, 75–80 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green S. A., Matos J. L. M., Yagi A., Shenvi R. A., Branch-selective hydroarylation: Iodoarene-olefin cross-coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12779–12782 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo J. C., Kim D., Pan C.-M., Edwards J. T., Yabe Y., Gui J., Qin T., Gutiérrez S., Giacoboni J., Smith M. W., Holland P. L., Baran P. S., Fe-catalyzed C–C bond construction from olefins via radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 2484–2503 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tellis J. C., Primer D. N., Molander G. A., Single-electron transmetalation in organoboron cross-coupling by photoredox/nickel dual catalysis. Science 345, 433–436 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz-Castillo P., Buchwald S. L., Applications of palladium-catalyzed C–N cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Rev. 116, 12564–12649 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu C., Szoszak M., Twisted Amides: From obscurity to broadly useful transition-metal-catalyzed reactions by N−C amide bond activation. Chem. - Eur. J. 23, 7157–7173 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basch C. H., Liao J., Xu J., Piane J. J., Watson M. P., Harnessing alkyl amines as electrophiles for nickel-catalyzed cross- couplings via C–N bond activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 5313–5316 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plunkett S., Basch C. H., Santana S. O., Watson M. P., Harnessing alkylpyridinium salts as electrophiles in deaminative alkyl−alkyl cross-couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2257–2262 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klauck F. J. R., James M. J., Glorius F., Deaminative strategy for the visible-light-mdiated generation of alkyl radicals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 12336–12339 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu J., He L., Noble A., Aggarwal V. K., Photoinduced deaminative borylation of alkylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10700–10704 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu J., Wang G., Li S., Shi Z., Selective C−N borylation of alkyl amines promoted by Lewis base. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 15227–15231 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandfort F., Strieth-Kalthoff F., Klauck F. J. R., James M. J., Glorius F., Deaminative borylation of aliphatic amines enabled by visible light excitation of an electron donor–acceptor complex. Chem. -Eur. J. 24, 17210–17214 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ociepa M., Turkowska J., Gryko D., Redox-activated amines in C(sp3)–C(sp) and C(sp3)–C(sp2) bond formation enabled by metal-free photoredox catalysis. ACS Catal. 8, 11362–11367 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang X., Zhang M. M., Xiong W., Lu L. Q., Xiao W. J., Deaminative (carbonylative) Alkyl–Heck-type reactions enabled by photocatalytic C−N bond activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 2402–2406 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woods B. P., Orland M., Huang C. Y., Sigman M. S., Doyle A. G., Nickel-catalyzed enantioselective reductive cross-coupling of styrenyl aziridines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 5688–5691 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ni S., Zhang W., Mei H., Han J. L., Pan Y., Ni-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling of amides with aryl iodide electrophiles via C–N bond activation. Org. Lett. 19, 2536–2539 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solladie G., Bauder C., Rossi L., Chiral sulfoxides in asymmetric synthesis: Enantioselective synthesis of the lactonic moiety of (+)-Compactin and (+)-Mevinolin. Application to a compactin analog. J. Org. Chem. 60, 7774–7777 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi S., Meng G., Szostak M., Synthesis of biaryls through nickel-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura coupling of amides by carbon–nitrogen bond cleavage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 6959–6963 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weix D. J., Methods and mechanisms for cross-electrophile coupling of Csp2 halides with alkyl electrophiles. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 1767–1775 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tasker S. Z., Standley E. A., Jamison T. F., Recent advances in homogeneous nickel catalysis. Nature 509, 299–309 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/5/6/eaaw9516/DC1

Table S1. Optimization of cross-coupling with bromoalkynes.

Table S2. Optimization of cross-coupling with alkyl bromides.

Characterization data and NMR spectra of the cross-coupling products 2 to 35.