Abstract

Introduction:

Self-management support (SMS) is a key factor in diabetes care, but true SMS has not been widely adopted by primary care practices. Interactive behavior-change technology (IBCT) can provide efficient methods for adoption of SMS in primary care. Practice facilitation has been effective in assisting practices in implementing complex evidence-based interventions, such as SMS. This study was designed to study the incremental impact of practice education, the Connection to Health (CTH) IBCT tool, and practice facilitation as approaches to enhance the translation of SMS for patients with diabetes in primary care practices.

Methods:

A cluster-randomized trial compared the effectiveness of three implementation strategies for enhancing SMS for patients with diabetes in 36 primary care practices: 1) SMS education (SMS-ED); 2) SMS education plus CTH availability (CTH); and 3) SMS education, CTH availability, plus brief practice facilitation (CTH+PF). Outcomes including hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels and SMS activities were assessed at 18 months post study initiation in a random sample of patients through medical record reviews.

Results:

A total of 488 patients enrolled in the CTH system (141 CTH, 347 CTH+PF). In the intent-to-treat analysis of patients with medical record reviews, HbA1c slopes did not differ between study arms (CTH vs SMS-ED: p=.2243, CTH=PF vs SMS-ED: p=.8601). However, patients from practices in the CTH+PF arm who used CTH showed significantly improved HbA1c trajectories over time compared to patients from SMS-ED practices (p=.0422). SMS activities were significantly increased in CTH and CTH+PF study arms compared to SMS-ED (CTH vs SMS-ED: p=.0223, CTH+PF vs SMS-ED: p=.0013). The impact of CTH on SMS activities was a significant mediator of the impact of the CTH and CTH+PF interventions on HbA1c.

Conclusion:

An interactive behavior change technology tool such as Connection to Health can increase primary care practice SMS activities and improve patient HbA1c levels. Even brief practice facilitation assists practices in implementing SMS.

Introduction

Most patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in the U.S. receive diabetes care in primary care settings. Self-management support (SMS) is a key factor in diabetes care, focusing on the central role of patients in managing their illness[1–4]. SMS provides tools and skills for patients to manage their care, typically with a focus on medication adherence, diet, exercise, chronic disease management, and other risk-related behaviors. This includes shared decision making, goal setting, and action planning around key health issues. However, while some forms of patient education are made available, true SMS has not been widely or effectively adopted by primary care practices[5 6], and SMS activities vary according to certain practice demographics and other characteristics [7]. Lack of SMS support for patients with diabetes or other chronic illnesses has been attributed to a range of system-level barriers, including a lack of training in the appropriate skills, poor reimbursement for SMS activities, and the chaos and competing demands of primary care[8–10]. Also, few tools are available to assist practices with self-management support.

Interactive behavior-change technology (IBCT) can provide efficient methods for the adoption of SMS interventions in primary care for patients with diabetes and related health risk behaviors[11 12], as they can provide a convenient, time-efficient way to provide tailored, individualized support and resources for patients[11 13 14]. The major goals of IBCT are to: 1) detect and then monitor patient needs for self-management support over time, 2) prompt clinician/patient discussions to engage patients in behavior change, 3) establish individualized priorities for identified problems, 4) provide options for intervention at the point of care, and 5) monitor success over time and prompt follow-ups[11 13]. There is strong evidence that automated and Web-based programs can effectively support diabetes self-management[15], including healthful eating/weight management[16–19], increasing physical activity[20–22], reducing depression symptoms, and smoking cessation[23 24]. Randomized trials have been conducted using IBCT programs for diabetes self-management with positive results[25 26]. However, to our knowledge no comprehensive system exists that includes prevention and multiple chronic disease monitoring and intervention that is based on practical, well-documented measures and directly tied to actionable resources and recommendations for clinicians and patients[6 27–33]. Most current IBCT SMS programs are largely informational, require high literacy, are limited to health-risk assessment without goal setting, action planning or follow-up, and do not emphasize patient-physician collaboration[34 35].

Connection to Health (CTH) is a comprehensive, evidence-based SMS program that assists practices with the implementation of SMS for diabetes and other chronic illnesses through IBCT. CTH has the potential of providing practices with a systematized, structured, and streamlined SMS program for practice teams and patients to use across multiple chronic illnesses and health behaviors. Patients complete an initial automated online assessment covering multiple issues related to diabetes and co-morbid conditions using abbreviated versions of state-of-the-art measures, each with cut-points defining a flagged area for concern. Patients automatically receive a scored summary report, which they are asked to review and identify potential priority areas. A separate clinician report includes decision support tools and intervention options for the clinician for each flagged area on the profile. These reports lead to a clinical discussion, with action planning, goal setting, and problem solving[36] structured through the same CTH program. CTH also includes online patient resources and tips to improve diabetes management.

Implementation of SMS, especially in a real world practice setting, involves relatively complex changes in workflow and process and can be difficult for practices without support. Practice facilitation has been effective in assisting practices in implementing organizational changes and evidence-based interventions[37–42]. A facilitator uses sound quality improvement processes and tools to assist a practice in tailoring a program to fit their unique practice situation, resources, and culture, improving its implementation and its sustainability over time.

This study was designed to study the incremental impact of practice education, the Connection to Health SMS tool, and practice facilitation as approaches to enhance the translation of SMS for patients with T2DM in diverse primary care practices. We used the RE-AIM framework to guide our evaluation. RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) is designed to enhance the quality, speed, and public health impact of efforts to translate research into practice. [43–48] In this study we place particular emphasis on the Reach, Effectiveness, and Implementation domains of RE-AIM. The hypotheses were that 1) practices with only a practice SMS educational intervention would potentially improve SMS activities, but not substantially; 2) Connection to Health would be an effective tool for improving SMS activities and potentially patient outcomes; and 3) practice facilitation would increase the uptake and effectiveness of both SMS and CTH.

Methods/Design

Design

We designed a three-arm, cluster-randomized trial to compare the effectiveness of three implementation strategies for enhancing SMS for patients with T2DM in primary care practices using CTH. Outcomes were assessed at 18 months post study initiation. The details of the study protocol have been described elsewhere[49] and are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Approaches to Implementing Self-Management Support for Type 2 Diabetes – Program Elements across Project Arms (2012 – 2018)

| Program Element | SMS-ED | CTH | CTH+F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connection to Health (CTH) computerized intervention program | No | Yes | Yes |

| Technical assistance with CTH implementation | No | Yes | Yes |

| Basic instructions on use of CTH | No | Yes | Yes |

| Assessment of baseline self-management support (SMS) and diabetes care activities | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Feedback of assessment and recommendations for practice | No | No | Yes |

| SMS education sessions with practice | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Website with SMS resources | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Practice facilitation: • Improvement team meetings – 4 over approximately 3 mos. • Workflow revision to implement CTH • Email contacts, other assistance between improvement team meetings and after 3 months as needed • Ongoing feedback of data regarding CTH usage |

No | No | Yes |

SMS-ED = Self-Management Support Education, CTH = Connection to Health, CTH+PF = Connection to Health with Practice Facilitation

Sample

We recruited 36 primary care practices, 18 each in Colorado and California to assure a wide diversity of practices. Inclusion criteria were family medicine or general internal medicine practices with a minimum of 80 patients with T2DM, with all clinicians agreeing to participate. Covariate constrained randomization procedures were used[50 51] to ensure acceptable study arm balance on key practice characteristics (number of providers, % Medicaid, % uninsured, number of diabetic patients, % of diabetic patients with HbA1c>9) that might impact the outcomes.

Interventions (see Table 1)

SMS Education (SMS-Ed) Arm:

The SMS-ED arm served as an attention control. Project staff met onsite with practice clinicians and staff members for two one-hour sessions to discuss key aspects of SMS. These SMS sessions were standardized across all study arms and topics included describing the differences between SMS and patient education, the evidence for providing SMS in primary care, and patient-centered counseling techniques. Practices also had access to a website with SMS resources for both patients and the practice, but they did not have access to the CTH program nor to any further SMS implementation support.

Connection to Health (CTH) Arm:

In addition to educational sessions on SMS and the web-based resources, practices in this arm received the full use of the CTH program, with basic technical assistance on program operation. The technical assistance covered instruction on CTH, assistance for any technical problems in incorporating the CTH platform into the practice’s computer systems, and answering any questions regarding the on use of CTH. Practices did not, however, receive any practice facilitation to assist with CTH adoption and implementation.

Connection to Health plus Facilitation (CTH+PF) Arm:

This arm included the same intervention components as CTH, but added short-term practice facilitation by a trained practice facilitator that focused on CTH adoption and implementation. The active practice facilitation phase included four practice facilitation meetings, to assist in developing a CTH adoption plan. Active facilitation was followed by monthly calls by the facilitator to review data regarding the practice’s use of CTH. A brief “booster” facilitation session could also be scheduled to address subsequent problems.

Patient Samples

Medical record reviews were conducted by research staff separate from the intervention team on a random sample of patients with type 2 diabetes who had received care in each practice for at least one year at baseline. Since allocation of patients occurred at the level of the practice, all patients within a practice were assigned to the same treatment condition, regardless of the extent to which the individual patient used the tools provided. Although the intervention could potentially impact the entire population of patients with T2DM, each practice in the CTH and CTH+PF arms selectively utilized CTH with patients. Therefore, practices in each of the two arms with CTH had patients who were and were not exposed to CTH. To preserve intent-to-treat approaches, evaluate the reach of CTH (CTH and CTH + PF arms only), and alleviate potential selection bias at the level of individual patient recruitment [52–55] (i.e. providers may selectively recommend CTH to some patients and not others, based on patient characteristics such as blood glucose control, perceived patient motivation, etc.), we evaluated two overlapping patient samples in each practice. The first was a random sample from the population of all patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who had a HbA1c done during the 18 months prior to the practice baseline date and at least one visit to the practice from baseline to 12 months after baseline, whether or not they participated in CTH – the “Intent to Treat Sample” (ITT). This sample enabled us to examine the reach of CTH as well as the effectiveness of each practice-based intervention on the primary outcome variables in the population of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A second sample in each practice was comprised of only those patients with diabetes who completed the CTH assessment – the “CTH Per Protocol Sample.” It should be noted that these two samples were not independent of each other; e.g., many in the CTH Per Protocol sample were included randomly in the intent to treat sample.

Measures

Primary Outcomes, including HbA1c, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and body mass index (BMI), were abstracted via medical record reviews covering 18 months prior to baseline through 18 months post-baseline. For each, the last measure prior to baseline was used as the baseline measure.

SMS activities: process of care elements were also assessed in medical record review, including evidence of SMS-related discussions, collaborative goal setting, action planning around patient goals, collaborative problem-solving regarding the action planning process, use of community resources to assist in goal attainment, and ongoing monitoring of progress on identified goals. SMS-related discussions were grouped into diabetes-related (medication management, nutrition, exercise, and diabetes management) and other behavioral health discussions (mental health, social problems, alcohol or substance abuse). The total number of SMS activities noted in the chart were summed for the 18-month periods prior to and following baseline. This does not include SMS activities that occurred out of the medical practice and were not noted in the chart.

Practice Characteristics were described and examined as potential confounders and moderators in analyses, including level of quality improvement experience, level of PCMH implementation, practice size, setting (rural/urban), type of practice organization, baseline performance characteristics related to diabetes, percentage of minority patients in the practice, and percentage of Medicaid or uninsured patients.

Data Analysis:

For this cluster randomized trial, descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, and one-way ANOVAs were computed for baseline patient and practice characteristics, initially testing for differences between: (1) intervention arms and (2) CTH participants vs. non-participants. The reach (from RE-AIM) of CTH was assessed in the CTH and CTH+PF arms as the proportion of patients in the ITT sample who were enrolled in CTH. A continuity-corrected chi-square test was used to assess differences in reach between the CTH and CTH+PF arms. Patient-level covariates were screened in bivariate analyses and included in multivariate analysis if they were sociodemographic variables (age, gender), related to the outcome at p<.2, or differed between treatment arms. Patient-level covariates screened in all analyses included age, gender, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, comorbid diagnoses (hypertension (HTN), hyperlipidemia, pulmonary, cardiovascular disease, depression, medications [HTN, lipids, oral diabetic, insulin]). We employed methods that utilized all available data, assuming ignorable missingness[56–59]. We used general (or generalized, i.e. Poisson) linear mixed models with random effects for patient and practice to incorporate both hierarchical (patients within practices) and longitudinal (repeated measures on patients over time) data structures [52–55 60–62]. For longitudinal analysis of patient-level outcomes, baseline is defined as the day of the first training meeting the practice had with the study team and is the same for all patients in that practice. For clinical measures, time is coded as days since baseline, converted to year for interpretability. For SMS activities, time is coded as pre (time=0) or post-baseline (time=1). Hypothesis tests were two-sided with alpha=.05 or p values reported. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C.).

RESULTS

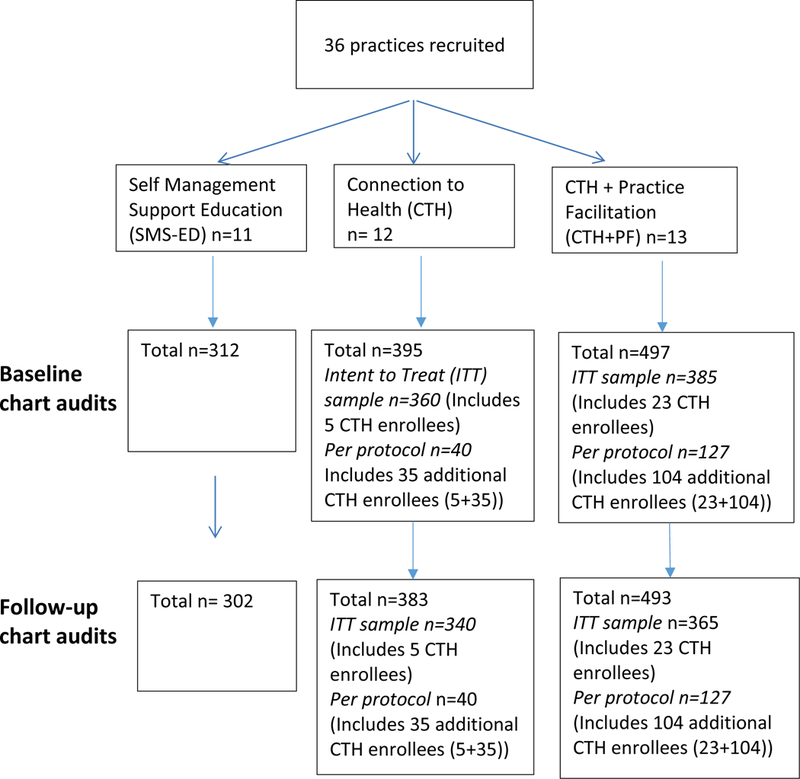

The CONSORT diagram of practice and patient flow in the study is shown in Figure 1. All 36 practices completed the study.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram of Practices and Chart Audits

Intent-To-Treat and Reach.

From practice-generated lists of patients with diabetes, a random sample of 1057 charts were audited for diabetes processes of care and outcomes as part of the intent-to-treat (ITT) sample. Of the total patients in the ITT sample, 5 of 360 (1.4%) patients from the CTH arm were enrolled in the CTH system, and 23 of 385 (6.0%) patients from the CTH + PF arm were enrolled in the CTH system (p=.002).

Per Protocol.

All patients enrolled in the CTH system were identified by medical record number in each practice. An additional random sample of these patients (up to 30 per practice, if available) was drawn to examine the effectiveness of CTH among enrolled patients (per protocol). Thus, charts from an additional 139 patients (35 CTH, 104 CTH + PF) who were enrolled in the CTH system were audited and added to the CTH-enrolled patients from the ITT sample to provide a total of 479 patients for the CTH per protocol sample to examine the effectiveness of the CTH program (312 SMS education as a comparison group, 40 CTH (35/40, 87.5% additional patients), 127 CTH + PF (104/127, 81.9% additional patients) among enrolled patients. A total of 488 patients enrolled in the CTH system - 141 (78 with self-reported diabetes) from CTH practices and 347 (223 with self-reported diabetes) from CTH+PF practices.

Practice and Patient Characteristics.

Baseline practice characteristics were very similar across the three arms (Table 2, all p>.2). It should be noted that 27 of the 36 practices (9 in each arm) were community health centers. Patient characteristics are also described in Table 2. Most baseline characteristics were similar across study arms. Interestingly, Table 2 shows that (compared to the respective ITT sample) the CTH+PF per protocol sample had higher levels of renal disease, cardiovascular disease, depression, and baseline BMI, less oral diabetic medicine and more insulin compared to the CTH per protocol sample. Thus, CTH-enrolled patients were more likely to have additional complications or risk factors. Also, while baseline HbA1c was similar across arms for the intent to treat (ITT) analyses (as would be anticipated due to that being one of the balancing criteria used in the randomization), it was higher in the CTH+PF group for the CTH per protocol group. This would indicate that the CTH+PF practices selectively enrolled patients with higher HbA1c levels and possibly more risk factors in CTH.

Table 2.

Baseline Practice and Patient Characteristics

| Practice Characteristics | Self Management Support Education (SMS-ED) N=11 |

Connection to Health (CTH) N=12 |

Connection to Health + Practice Facilitation (CTH+PF) N=13 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice Type Federally Qualified Health Center, n (%) | 9 (81.8%) | 9 (75%) | 9 (69.2%) | ||

| Number of clinicians, mean (sd) | 7.4 (3.4) | 7.3 (4.1) | 6.1 (4.3) | ||

| % Medicaid, mean (sd) | 41.5 (21.5) | 35.1 (22.0) | 38.7 (18.4) | ||

| % Uninsured, mean (sd) | 27.3 (17.9 | 28.2 (19.1) | 25.6 (21.2) | ||

| % Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) > 9, mean (sd) | 28.4 (11.1) | 22.9 (9.1) | 28.5 (5.6) | ||

| Number of diabetic patients, mean (sd) | 589.8 (392.4 | 541.3 (385.2) | 408.9 (309.0) | ||

|

PCMH Status

Some implementation, but not recognition, n (%) PCMH recognition, n (%) |

1 (9.1%) 8 (72.7%) |

3 (25.0%) 8 (66.7%) |

4 (30.8%) 8 (61.5%) |

||

| Patient Characteristics (From Chart Audits) | |||||

| SMS ED Arm: Intent to Treat and Per Protocol Samples N=312 |

CTH Arm: Intent to Treat Sample N=360 |

CTH Arm:

CTH Per Protocol Sample N=40 |

CTH+PF Arm: Intent to Treat Sample N=385 |

CTH+PF Arm:

CTH Per Protocol Sample N=127 |

|

| Variable | Mean (sd) or % | Mean (sd) or % | Mean (sd) or % | Mean (sd) or % | Mean (sd) or % |

| Gender, % female | 54.5% | 60.6% | 62.5% | 57.4% | 60.6% |

| Age (years) | 58.3 (12.8) | 60.0 (12.6) | 58.3 (12.5) | 60.8 (11.5) | 58.3 (11.6) |

| Number of medical co-morbidities | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.4 (.9) | 1.8 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.0) |

| Comorbid conditions Hypertension Pulmonary Diabetic nephropathy Renal disease Cardiovascular disease Depression |

73.4% 13.1% 11.5% 10.9% 7.4% 18.9% |

66.1% 10.8% 12.8% 8.1% 6.9% 20.0% |

65.0% 7.5% 5.0% 5.0% 0.0% 17.5% |

70.1% 15.3% 10.7% 3.6% 10.9% 19.2% |

72.4% 15.8% 10.2% 11.8% 11.8% 23.6% |

| Current smoker | 19.6% | 14.4% | 10.0% | 15.1% | 13.4% |

| Baseline HbA1c | 8.1 (2.2) | 7.9 (2.0) | 7.9 (2.0) | 7.8 (1.9) | 8.5 (1.9) |

| Baseline Body Mass Index | 32.6 (7.6) | 32.1 (7.3) | 32.4 (5.3) | 33.3 (7.2) | 34.7 (7.9) |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure (BP) | 129.7 (16.1) | 130.9 (16.9) | 130.9 (17.6) | 128.7 (13.5) | 129.6 (16.4) |

| Baseline diastolic BP | 76.6 (9.0) | 77.6 (9.3) | 78.2 (7.8) | 76.6 (8.5) | 78.9 (9.7) |

| Medications Lipid lowering med Anti-hypertensive Anti-depressant Oral diabetic med Insulin |

61.4% 75.2% 21.6% 74.3% 34.3% |

65.2% 74.4% 34.1% 81.1% 33.6% |

77.5% 77.5% 22.5% 85.0% 25.0% |

68.5% 78.9% 36.5% 81.3% 28.6% |

71.7% 78.0% 22.8% 72.2% 41.7% |

SMS-ED = Self-Management Support Education, CTH = Connection to Health, CTH+PF = Connection to Health with Practice Facilitation

Clinical Outcomes.

Table 3 shows the results of the intent-to-treat (ITT) and CTH per protocol longitudinal analyses of patient-level clinical outcomes over time by study arm, adjusted for patient level covariates in multivariable models. Practice level covariates were not significant and were not included in final models. CTH per protocol analyses compare patients in the CTH and CTH+PF arms who enrolled in the CTH program and were randomly selected for the CTH per protocol sample to all patients in the SMS-ED arm.

Table 3.

Intent to Treat and Connection to Health Per Protocol Comparisons of Impact on Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) over Time

| Outcome is HbA1c over time | Intent To Treat, N=1022 |

Connection to Health Per Protocol, N=458 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adjusted models Coef (SE) |

p-value | Adjusted models Coef (SE) |

p-value |

| Intercept | 7.5385 (.1941) | <.0001 | 6.6848 (.2368) | <.0001 |

| Age group 17 to 49 50 to 64 65 or greater |

ref .8017 (.1368) −1.2746 (.1449) |

--- <.0001 <.0001 |

Ref .8571 (.1956) −1.057 (.2199) |

--- <.0001 <.0001 |

| Gender - Female | .0881 (.1034) | .3942 | .2259 (.1572) | .1509 |

| BMI (at baseline, centered) | −.0232 (.0070) | .0010 | −0.0436 (.0105) | <.0001 |

| Pulmonary | −.4775 (.2289) | .0371 | ||

| Diabetic retinopathy | .3368 (.1595) | .0348 | ||

| Renal | .4531 (.2587) | .0801 | ||

| Oral diabetic medications | .7150 (.1287) | <.0001 | 0.6452 (.1817) | .0004 |

| Insulin | 1.7418 (.1117) | <.0001 | 1.7147 (.1663) | <.0001 |

| Intervention vs SMS-ED (at baseline) CTH vs SMS-ED CTH + PF vs SMS-ED |

−.0987 (.1551) .0160 (.1524) |

.5245 .9164 |

−0.049 (.3530) 0.6519 (.2300) |

.8891 .0047 |

| HbA1c change per 12 months (slope) SMS-ED CTH CTH + PF |

.1638 (.0853) .3022 (.0756) .1441 (.0721) |

Compared to SMS-ED --- .2243 .8601 |

0.1546 (.0920) 0.0671 (.2255) −0.1640 (.1269) |

Compared to SMS-ED --- .7193 .0422 |

SMS-ED = Self-Management Support Education, CTH = Connection to Health, CTH+PF = Connection to Health with Practice Facilitation

Overall p-value for group x time: .2724. The overall group x time effect is used to determine whether there are differences in slopes between the three study arms. The coefficients in the table show the actual slopes (SE) for each study arm, along with the p-value for the differences for CTH vs SMS-ED, and CTH+PF vs SMS-ED.

HbA1c.

Examining slopes (change per year) for each study arm, ITT analyses suggest that patients’ HbA1c levels tended to increase over time, but slopes did not differ between study arms (CTH vs SMS-ED: p=.2243, CTH=PF vs SMS-ED: p=.8601) (See table 3).

However, in the CTH per protocol sample, patients in the CTH+PF arm showed significantly improved HbA1c trajectories over time compared to patients in the SMS-ED arm (p=.0422). HbA1c (measured as %) trajectories for patients in the CTH arm did not differ significantly from patients in the SMS-ED arm (p=.7193) or between the CTH and CTH+PF arms (p=.3718). On average, HbA1c increased by .1546% per year in the SMS arm (e.g. 8.0% vs 8.1546%) and .0671 in the CTH arm (e.g. 8.0% vs 8.0671%). In contrast, in the CTH+PF arm, HbA1c decreased by .1640% per year on average (e.g. 8.0% vs 7.836%).

Blood Pressure.

Adjusted ITT analysis of systolic BP suggested that BP remained stable over time in SMS-ED (slope=0.3474, p=.8248), and BP slopes did not differ by study arm (CTH slope=−1.3276, CTH vs SMS-ED: p=.4383; CTH+PF slope=−0.7788, CTH+PF vs SMS-ED: p=.8380). Results were similar for CTH per protocol analyses examining CTH enrolled patients compared to SMS-ED (SMS-ED slope=−0.1147, p=.8802, CTH slope=0.5599, CTH vs SMS-ED: p=.7384, CTH+PF slope=−.2733, CTH+PF vs SMS-ED: p=.9042).

BMI.

Adjusted ITT analysis of BMI over time indicated a decline in BMI in SMS-ED: (slope= −0.4006, p=.0005), but slopes did not differ for CTH (slope=−0.1554, CTH vs SMS-ED: p=.1173) or CTH+PF (slope=−0.3115, CTH+PF vs SMS-ED: p=.5613). Results were similar in CTH per protocol analyses, with significant decline in BMI in SMS-ED (slope=−0.4014, p<.0001), but similar slopes among study arms (CTH slope=−.2638, CTH vs SMS-ED: p=.6352, CTH+PF: slope=−0.3313, CTH+PF vs SMS-ED: p=.7050).

Process of Care Outcomes.

Analysis of total SMS activities during the 18-month pre and post periods are shown in Table 4. Both ITT and CTH per protocol analyses indicated that pre-post change in the number of SMS activities was significantly greater for patients in CTH and CTH+PF study arms, compared to SMS-ED (ITT: CTH vs SMS-ED: 6.82 vs 4.58, p=.0223, CTH+PF vs SMS-ED: 7.68 vs 4.58, p=.0013; CTH per protocol: CTH vs SMS-ED: 15.63 vs 4.56, p<.0001, CTH+PF vs SMS-ED: 14.94 vs 4.56, p<.0001).

Table 4.

Intent to Treat and Connection to Health Per Protocol Comparisons of Self Management Support Activities over Time

| Outcome is Hemoglobin A1c over time | Intent To Treat N=1054 |

CTH Per Protocol N=479 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adjusted models Coef (SE) |

p-value | Adjusted models Coef (SE) |

p-value |

| Intercept | 3.94 (1.32) | ---- | 3.04 (2.87) | ----- |

| Age group 17 to 49 50 to 64 65 or greater |

ref .47 (.61) −1.34 (.66) |

--- .4463 .0412 |

Ref .98 (.94) −1.16 (1.04) |

--- .2984 .2673 |

| Gender - Female | . 0.39 (.46) | .4008 | 1.53 (.73) | .0376 |

| Depression | 3.28 (.58) | <.0001 | ||

| Insulin | 3.39 (.50) | <.0001 | 5.03 (.80) | <.0001 |

| Intervention vs SMS-ED (at baseline) CTH vs SMS-ED CTH + PF vs SMS-ED |

−.27 (1.67) 0.81 (1.63) |

.8705 .6221 |

1.81 (4.73) 4.87 (3.96) |

.7026 .2192 |

| Pre-post change SMS-ED CTH CTH + PF |

4.58 (.72) 6.82 (.66) 7.68 (.64) |

Compared to SMS-ED --- .0223 .0013 |

4.56 (.84) 15.63 (2.32) 14.94 (1.30) |

Compared to SMS-ED --- <.0001 <.0001 |

SMS-ED = Self-Management Support Education, CTH = Connection to Health, CTH+PF = Connection to Health with Practice Facilitation

Finally, we examined the potential mediational effects of total number of SMS activities in the CTH per protocol sample on improvement in HbA1c by adding the total number of diabetes-related discussions during the post-intervention period to the overall model, along with an interaction term (time x discussions) to adjust for the effect of discussions on change in HbA1c. In this model the difference in slopes for CTH and CTH+PF becomes non-significant (CTH vs SMS-ED: p=.9028, CTH+PF vs SMS-ED: p=.2113) and the adjusted slopes increase (SMS-ED: 0.2206, CTH: 0.1905, CTH+PF: 0.0047), suggesting that total SMS activities may partially mediate improvement in HbA1c over time.

Discussion

While patient self-management is frequently highlighted as a cornerstone of disease management, steep barriers exist for primary care practices to engage in SMS. This trial of methods for supporting the implementation of SMS for diabetes in primary care practices produced some fascinating results that add to our understanding of how to improve this important practice-level behavior. This real-life study did not require practices in the CTH or CTH+PF arms to enroll patients in Connection to Health, but rather observed practice SMS behaviors and the resulting impacts on patient clinical outcomes as a result of these brief interventions. Relatively few patients were enrolled in Connection to Health, but practices in the CTH+PF arm enrolled more patients and used Connection to Health more effectively as a tool. In particular, they appear to have targeted patients with more risk factors and comorbid conditions and more poorly controlled diabetes for use of Connection to Health. This demonstrates that even a brief practice facilitation intervention can increase the effective uptake of this type of IBCT tool. We believe that a more robust practice facilitation intervention could have resulted in greater and improved use of both SMS and CTH. The relatively small numbers of patients enrolled in Connection to Health limited the ITT impact on HbA1c and other patient outcomes. However, the significant differences seen in the CTH per protocol analyses indicate that where Connection to Health is used with patients with diabetes, it can have a positive impact on patient HbA1c, particularly when coupled with practice facilitation to assist practices with CTH implementation.

Furthermore, both the ITT and CTH per protocol analyses showed a positive increase in the number of SMS activities in the CTH and CTH+PF arms compared to the SMS-ED arm, along with a positive increase in other behavioral health discussions in the CTH and CTH+PF arms in the CTH per protocol analysis. The provision to practices and use of the SMS tools available in Connection to Health significantly improved practices’ implementation of SMS activities, and the impact on SMS activities appears to have mediated the impact of the CTH and CTH+PF interventions on HbA1c. It is notable that SMS activities increased more in the two CTH arms even where CTH was not specifically used. The structured approach to SMS represented in CTH may have provided practices with a model for SMS that they followed even when not using CTH specifically.

Limitations to this study include the disproportionate number of federally qualified health centers in the sample compared to the general practice population of the United States. Engaged practices were from two Western states and may not be representative of all practices. Since some of the practices utilized CTH as a method for recording SMS activities and did not capture that data in their EHR, the total number of SMS activities may be under-represented in the chart audits, and the overall impact of CTH on SMS activities may be underestimated. Also, since this was a real life study, practices may have had other initiatives going on that impacted these results.

The results of this study show that an interactive behavior change technology and SMS tool such as Connection to Health can increase aspects of primary care practice SMS activities and improve patient HbA1c levels. This is true despite a relatively low implementation of CTH in the practices. A brief practice facilitation intervention increased effective use of CTH, but more robust practice facilitation may be needed to fully and sustainably implement an IBCT tool of this type. Further studies of approaches for implementing and delivering more efficient and effective SMS for patients with diabetes and other chronic conditions are needed, including how to best target patients for SMS interventions. As alternative, value-based payment models continue to move forward, practices are increasingly motivated to improve patient self-management support, and Connection to Health and other IBCT tools can be of assistance if implemented effectively.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: Funding for this work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK Award Number 1R18DK096387; W. Perry Dickinson, Principal Investigator), 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20892, Telephone: 1-800-860-8747

Footnotes

Competing Interests: All authors state that they have no competing interests

References

- 1.Berenson RA, Hammons T, Gans DN, et al. A house is not a home: keeping patients at the center of practice redesign. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2008;27(5):1219–30 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1219[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riley KM, Glasgow RE, Eakin EG. Resources for Health: A Social-Ecological Intervention for Supporting Self-management of Chronic Conditions. Journal of health psychology 2001;6(6):693–705 doi: 10.1177/135910530100600607[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glasgow RE, Toobert DJ, Hampson SE. Effects of a brief office-based intervention to facilitate diabetes dietary self-management. Diabetes care 1996;19(8):835–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrera M Jr., Toobert DJ, Angell KL, Glasgow RE, Mackinnon DP. Social support and social-ecological resources as mediators of lifestyle intervention effects for type 2 diabetes. Journal of health psychology 2006;11(3):483–95 doi: 10.1177/1359105306063321[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schillinger D, Handley M, Wang F, Hammer H. Effects of self-management support on structure, process, and outcomes among vulnerable patients with diabetes: a three-arm practical clinical trial. Diabetes care 2009;32(4):559–66 doi: 10.2337/dc08-0787[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes care 2001;24(3):561–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jortberg BT, Fernald DH, Hessler DM, Dickinson LM, Wearner R, Connelly L, Holtrop JS, Fisher L, Dickinson WP. Baseline Practice Characteristics for Connection to Health: A Cluster-Randomized Trial Translating Self-Management Support into Primary Care Practices. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tallia AF, Stange KC, McDaniel RR Jr., Aita VA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Understanding organizational designs of primary care practices. Journal of healthcare management / American College of Healthcare Executives 2003;48(1):45–59; discussion 60–1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solberg LI, Brekke ML, Fazio CJ, et al. Lessons from experienced guideline implementers: attend to many factors and use multiple strategies. The Joint Commission journal on quality improvement 2000;26(4):171–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaen CR. Successful health information technology implementation requires practice and health care system transformation. Annals of family medicine 2011;9(5):388–9 doi: 10.1370/afm.1307[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Redding C, et al. Stage-based expert systems to guide a population of primary care patients to quit smoking, eat healthier, prevent skin cancer, and receive regular mammograms. Preventive medicine 2005;41(2):406–16 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.050[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glasgow RE, Bull SS, Piette JD, Steiner JF. Interactive behavior change technology. A partial solution to the competing demands of primary care. American journal of preventive medicine 2004;27(2 Suppl):80–7 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.026[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vandelanotte C, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Brug J. Two-year follow-up of sequential and simultaneous interactive computer-tailored interventions for increasing physical activity and decreasing fat intake. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine 2007;33(2):213–9 doi: 10.1080/08836610701310086[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glasgow RE, Edwards LL, Whitesides H, Carroll N, Sanders TJ, McCray BL. Reach and effectiveness of DVD and in-person diabetes self-management education. Chronic illness 2009;5(4):243–9 doi: 10.1177/1742395309343978[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabin BA, Glasgow RE. Dissemination and implementation of interactive health communication applications. New York, NY: Routledge, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brug J, Oenema A, Campbell M. Past, present, and future of computer-tailored nutrition education. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2003;77(4 Suppl):1028s–34s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tate DF, Jackvony EH, Wing RR. Effects of Internet behavioral counseling on weight loss in adults at risk for type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Jama 2003;289(14):1833–6 doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1833[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oenema A, Brug J, Lechner L. Web-based tailored nutrition education: results of a randomized controlled trial. Health education research 2001;16(6):647–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vandelanotte C, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Brug J. Acceptability and feasibility of an interactive computer-tailored fat intake intervention in Belgium. Health promotion international 2004;19(4):463–70 doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah408[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wanner M, Martin-Diener E, Braun-Fahrlander C, Bauer G, Martin BW. Effectiveness of active-online, an individually tailored physical activity intervention, in a real-life setting: randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research 2009;11(3):e23 doi: 10.2196/jmir.1179[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spittaels H, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Brug J, Vandelanotte C. Effectiveness of an online computer-tailored physical activity intervention in a real-life setting. Health education research 2007;22(3):385–96 doi: 10.1093/her/cyl096[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steele R, Mummery WK, Dwyer T. Using the Internet to promote physical activity: a randomized trial of intervention delivery modes. Journal of physical activity & health 2007;4(3):245–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strecher VJ, McClure J, Alexander G, et al. The role of engagement in a tailored web-based smoking cessation program: randomized controlled trial. Journal of medical Internet research 2008;10(5):e36 doi: 10.2196/jmir.1002[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strecher VJ, McClure JB, Alexander GL, et al. Web-based smoking-cessation programs: results of a randomized trial. American journal of preventive medicine 2008;34(5):373–81 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.024[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin Boren S, Gunlock TL, Krishna S, Kramer TC. Computer-aided diabetes education: a synthesis of randomized controlled trials. AMIA … Annual Symposium proceedings. AMIA Symposium 2006:51–5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welch G, Weinger K, Anderson B, Polonsky WH. Responsiveness of the Problem Areas In Diabetes (PAID) questionnaire. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association 2003;20(1):69–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glasgow RE, Hiss RG, Anderson RM, et al. Report of the health care delivery work group: behavioral research related to the establishment of a chronic disease model for diabetes care. Diabetes care 2001;24(1):124–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hiss RG. Barriers to care in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Michigan experience. Annals of internal medicine 1996;124(1 Pt 2):146–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner EH, Davis C, Schaefer J, Von Korff M, Austin B. A survey of leading chronic disease management programs: are they consistent with the literature? Managed care quarterly 1999;7(3):56–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. Jama 1999;282(15):1458–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polonsky WH, Earles J, Smith S, et al. Integrating medical management with diabetes self-management training: a randomized control trial of the Diabetes Outpatient Intensive Treatment program. Diabetes care 2003;26(11):3048–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norris SL, Nichols PJ, Caspersen CJ, et al. Increasing diabetes self-management education in community settings. A systematic review. American journal of preventive medicine 2002;22(4 Suppl ):39–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark NM, Becker MH, Lorig K, Rakowski W, Anderson L. Self-management of chronic disease by older adults: A review and questions for research. J Aging Health 1991;3(1):3–27 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bennett GG, Glasgow RE. The delivery of public health interventions via the Internet: actualizing their potential. Annual review of public health 2009;30:273–92 doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100235[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strecher V Internet methods for delivering behavioral and health-related interventions (eHealth). Annual review of clinical psychology 2007;3:53–76 doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091428[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE. Problem solving and diabetes self-care. Journal of behavioral medicine 1991;14(1):71–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Aspy CB. Practice facilitators: a review of the literature. Family medicine 2005;37(8):581–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, Zronek S, et al. A clinical trial of tailored office systems for preventive service delivery. The Study to Enhance Prevention by Understanding Practice (STEP-UP). American journal of preventive medicine 2001;21(1):20–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stange KC, Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, Dietrich AJ. Sustainability of a practice-individualized preventive service delivery intervention. American journal of preventive medicine 2003;25(4):296–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hogg W, Baskerville N, Nykiforuk C, Mallen D. Improved preventive care in family practices with outreach facilitation: understanding success and failure. Journal of health services research & policy 2002;7(4):195–201 doi: 10.1258/135581902320432714[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buscaj E, Hall T, Montgomery L, et al. Practice facilitation for PCMH implementation in residency practices. Family medicine 2016;48(10):795–800 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Annals of Family Medicine. 2012;10(1):63–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glasgow RE, Dickinson WP, Fisher L, et al. Patient-Centered Assessment, communication, and Outcomes in the Primary Care Medical Home: Use of RE-AIM to Develop a Multi-Media Facilitation Tool. Implementation Science. 2011;6:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glasgow RE, McKay HG, Piette JD, Reynolds KD. The RE-AIM framework for evaluating interventions: what can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management? Patient Educ Couns 2001;44(2):119–27 doi: 10.S0738/3991(00)00186-5 [pii][published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glasgow RE, Linnan LA. Evaluation of theory-based interventions In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4th ed San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2008:487–508. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaglio B, Glasgow RE. Evaluation Approaches for Dissemination and Implementation Research In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, eds. Dissemination and implementation research in health : translating science to practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Belza B, Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE. RE-AIM for program planning: Overview and applications. Center for Healthy Aging Issue Brief., 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toobert DJ. RE-AIM: Application to AoA evidence-based demonstration projects. 3rd Annual Agency on Aging Grantees Conference Washington, D.C., 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dickinson WP, Dickinson LM, Jortberg BT, Hessler DM, Fernald DH, Fisher L. A protocol for a cluster randomized trial comparing strategies for translating self-management support into primary care practices. BMC Fam Pract 2018;19(1):126 doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0810-x[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dickinson LM, Beaty B, Fox C, et al. Pragmatic Cluster Randomized Trials Using Covariate Constrained Randomization: A Method for Practice-based Research Networks (PBRNs). J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28(5):663–72 doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.05.150001[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li F, Lokhnygina Y, Murray DM, Heagerty PJ, DeLong ER. An evaluation of constrained randomization for the design and analysis of group-randomized trials. Statistics in medicine 2016;35(10):1565–79 doi: 10.1002/sim.6813[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giraudeau B, Ravaud P. Preventing bias in cluster randomised trials. PLoS medicine 2009;6(5):e1000065 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000065[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Puffer S, Torgerson D, Watson J. Evidence for risk of bias in cluster randomised trials: review of recent trials published in three general medical journals. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2003;327(7418):785–9 doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7418.785[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG. CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2004;328(7441):702–8 doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7441.702[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murray D, editor. Design and Analysis of Group-Randomized Trials. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood estimation from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol 1977(Series B):1–38 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. New York: Wiley, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fairclough D, editor. Design and Analysis of Quality of Life Studies in Clinical Trials. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diggle P, Kenward MG. Informative drop-out in longitudinal data-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat 1994(43):49–93 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Littell R, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, editors. SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Longitudinal Data Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW, editors. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. 2nd ed Newbury Park: Sage Publications, 2000. [Google Scholar]