Abstract

Objective:

Food insecurity is associated with childhood obesity possibly mediated through caregiver feeding practices and beliefs. We examined if caregiver feeding practices differed by household food security status in a diverse sample of infants. We hypothesize feeding practices differ based on food security status.

Patients and Methods:

Baseline cross-sectional analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial to prevent obesity. Included in the analysis was 842 caregivers of 2-month-old infants presenting for well-child care at 4 academic institutions. Food insecurity exposure was based on an affirmative answer to one of two items in a 2-item validated questionnaire. Chi-square tests examined the association between parent feeding practices and food security status. Logistic regression adjusted for covariates. Differences in caregiver feeding practices by food security status and race/ethnicity were explored with an interaction term (food security status x race/ethnicity).

Results:

43% of families screened as food insecure. In adjusted logistic regression, parents from food-insecure households were more likely to endorse that “the best way to make an infant stop crying is to feed him/her” (aOR: 1.72, 95% CI: 1.28-2.29); and “When my baby cries, I immediately feed him/her” (aOR: 1.40, 95%CI: 1.06-1.83). Food insecure caregivers less frequently endorsed paying attention to their baby when s/he is full or hungry (OR 0.57 95%CI: 0.34-0.96). Racial/ethnic differences in beliefs and behaviors were observed by food security status.

Conclusions:

During early infancy, feeding practices differed among caregivers by household food security status. Further research is needed to examine whether these practices are associated with increased risk of obesity and obesity-related morbidity.

Keywords: Food Insecurity, infants, obesity

INTRODUCTION

Household food insecurity, defined as a household where “access to adequate food is limited by a lack of money or other resource” affects many families in the US1. In 2015, 6.4 million households with children did not have reliable access to healthy foods, affecting approximately 13.1 million children or more than 1 out of 6 children living in the United States2. Children raised in food insecure households are more likely to suffer from iron deficiency anemia3,4, poor school performance5,6, and developmental delay6-8. While several studies have found that food insecurity is associated with childhood obesity,9-11 other studies have not found this association12. One possible explanation for why food insecurity might contribute to obesity is that food insecurity may lead to increased consumption of poor quality foods that tend to be less expensive yet higher in fat and sugar content13,14.

In addition to affecting diet quality during childhood, the influence of food insecurity on obesity may also be explained by parental feeding behaviors during childhood. For caregivers living in food insecure households, feelings of worry and vulnerability surrounding their limited household food supply may affect not only what they feed their children but also how they feed their children. Feeding practices during childhood could play a role in establishing feeding habits and cardiovascular health, and, potentially, weight later in adulthood15-17. In studies conducted among affluent, mostly white children, parental feeding practices were associated with weight-for-age later in adolescence and adulthood18-21.

Among mainly immigrant Hispanic mothers living in New York, food insecurity is associated with parental restrictive and controlling feeding behaviors of infants22. Food insecurity has also been associated with pressured and restrictive feeding behaviors of preschool children as well as the use of high energy supplements in preschool aged children. 23. In addition, despite evidence that exclusive breastfeeding is associated with decreased risk of childhood obesity24 few studies have compared breastfeeding practices among mothers differentially affected by food insecurity.. However, further information derived from a diverse sample of caregivers is warranted to explore specific beliefs and practices surrounding infant feeding, including breastfeeding prevalence and solid food introduction25, among food-insecure caregivers.

Greenlight, a multi-site randomized trial designed to prevent childhood obesity, has been described earlier 26 and surveys parents of 2-month-old infants residing in four low-income communities across the US with detailed assessment of feeding behaviors at age 2 months27, the study’s baseline Greenlight provided an umbrella study for the research described here with the following aims: (1) to assess the association between household food security status and caregiver feeding practices and beliefs and (2) to examine the association between household food security status and infant exposure to exclusive breastfeeding status and solid food introduction.

METHODS

Study Population and Data Collection

The sample included caregivers enrolled in a multisite randomized cluster trial of a previously described26 obesity prevention intervention for infants from 2-24 months, recruited from pediatric continuity clinics based in academic teaching hospitals in four US cities: Nashville, TN; New York City, NY; Miami, FL; and Chapel Hill, NC. Interviews of caregivers were conducted in-person at the clinic visit when possible or by telephone using a standardized questionnaire. For the purposes of the primary study, eligible participants were enrolled if caregivers spoke fluent English or Spanish, the child was 6 to 16 weeks of age, and was presenting for a 2-month well child visit with plans to return for all well-child visits until age two years. Children older than 2 months were eligible for inclusion in study as long as they were presenting for a 2 month well child visit.

Caregivers were excluded if they were less than 18 years old, if they had significant mental or neurological illness or poor visual acuity thereby limiting their ability to participate in some portions of the study questionnaire. Potential subjects were also excluded if their infants were born at less than 34 weeks gestational age, with birth weight of less than 1.5kg, if the infant was a multiple birth, if there were provider concerns about their current weight (<3th percentile at 2 month visit), or if there were any known medical problems that might interfere with healthy weight gain. All study documents were translated into Spanish and reviewed by an advisory committee of native speakers from four countries in Latin America to ensure materials were culturally competent26 Informed consent was obtained from caregivers prior to collection of information. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at all the respective institutions.

Study Measures

Exposure variable: Household food security.

Household food insecurity was assessed using a validated 2-item screening questionnaire28. The items pertained to whether, over the previous 12 months, caregivers: 1) worried that food would run out before they got money to buy more; 2) thought the food that was bought did not last and there was no money to buy more. Caregivers were asked to report if the statements were “often true”, “sometimes true” or “never true”. As done in prior studies, a family was classified as food insecure if they had an affirmative response (sometimes and often true) to at least one of the two questions.1,22,28

Outcome variables: Infant Feeding Beliefs and Practices.

Caregivers reported on infant nutrition, specifically with regards to any breastfeeding, volume of formula fed to bottle-fed infants at each meal, and solid food introduction in response to the following questions: “How much formula do you usually give [your child] at each feeding?”(open-ended); and “Is [your child] eating solid foods yet or do you put any solid foods in the bottle?”(yes or no),

Caregiver feeding beliefs and practices were assessed using 15 items selected from the Infant Feeding Style Questionnaire (IFSQ), an instrument validated among a sample of low-income, African American caregivers and their infants ranging in age from 3-20 months29. The IFSQ has 83 individual questions loading onto 5 feeding style model constructs: laissez-faire, pressuring/overfeeding, restrictive, indulgent and responsive29. The use of individual IFSQ items has been reported previously in children less than 3 months of age27. The items selected for the study were chosen during study design as they represent caregiver feeding behaviors and beliefs that were hypothesized to be modifiable by the planned intervention within the aims of the randomized trial26 . This approached has been used in previously published studies27,30. Of the 15 items selected 2 loaded onto the restrictive domain; 4 responsive, 6 pressuring and 3 LF Caregivers responded to these derived statements on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘always’ to ‘never’ for feeding practices or ‘agree’ to ‘disagree’ for feeding beliefs of individual items.

Covariates

Caregivers also were asked to provide socio-demographic information, such as their annual household income and participation in federal food assistance programs including Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women Infants and Children (WIC).

Anthropometric data on each infant was also gathered at the clinic well visit by practice nurses or nursing assistants.

Data analysis

Characteristics of the study population and features of infant nutrition and feeding practices/beliefs were described by food insecurity status using means and standard deviations for continuous variables, frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and compared using the Chi-squared test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test as appropriate. The cohort included in analyses was restricted to subjects with the food insecurity variable available.

To assess for the independent association of food insecurity status with feeding practices and beliefs we performed multivariable analysis using proportional odds logistic regression models. Separate proportional odds ordinal logistic regression models were conducted, with each feeding practice and belief treated as an ordered response dependent variable, to estimate the adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of the exposure of food insecurity vs. food secure (referent). We included the following list of covariates, chosen a priori, for adjustment: infant gender, number of children in the home, caregiver race/ethnicity, income, caregiver education, study site and WIC enrollment status.

Finally, we tested for interaction between race/ethnicity and food security status and association with feeding practices and beliefs. A cross product term with between race/ethnicity and food security status (race/ethnicity x food security status) was created. The interaction was explored based on prior research which showed differences in feeding behaviors and beliefs by race and ethnicity27. The interaction term allows for exploration of differences in caregiver feeding behaviors by race/ethnicity and food security status. For example: do food secure Hispanic caregivers feed their infant the same as food insecure Hispanic caregivers? For those dependent variables that had statistically significant interaction with ethnicity, caregiver mean score of affirmation of these statements is presented.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata/IC 14.2 for Windows (http://www.stata.com). Two-sided P values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 842 parent-child dyads were included. Socio-demographic characteristics of the caregiver sample are summarized in Table 1. The majority of caregivers (96%) were mothers of the enrolled infants. The sample was racially and ethnically diverse, 28%, Black (non-Hispanic), 18% White, 50% Hispanic and 4% as other. The average age of the enrolled infant was 2.3 months. A large majority of the sample (85%) was enrolled in WIC, and 32% reported a very low annual household income of less than $10,000. Overall, 377 (45%) of caregivers lived in households that met the definition of food insecurity.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of Greenlight Cohort by Food Insecurity Status

| Characteristics | Overall (n=842) |

Food Secure (n=465) |

Food Insecure (n=377) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant age (mean months (SD)) | 2.3 (0.4) | 2.33(0.4) | 2.3(0.5) | 0.78a |

| Infant sex | ||||

| Female | 430 (51%) | 231(50%) | 199(53%) | 0.37b |

| Child Insurance | ||||

| Medicaid | 726(86%) | 371(79%) | 355(94%) | <0.001b |

| Private Insurance | 90(11%) | 82(17%) | 8(2%) | |

| None | 26(3%) | 12(3%) | 14(4%) | |

| No. Adults(>18yrs) in Household | 0.02b | |||

| 1 | 85(10%) | 39(8%) | 46(12%) | |

| 2 | 480(57%) | 284(61%) | 196(51%) | |

| 3 or more | 277(33%) | 142(31%) | 135(36%) | |

| No. Children (=<18yrs) in Household | ||||

| 1 | 335 (40%) | 194 (42%) | 141 (37%) | 0.08b |

| 2 | 254 (30%) | 146 (31%) | 108 (29%) | |

| 3 or more | 253 (30%) | 125 (27%) | 128 (34%) | |

| Caregiver relationship to child | ||||

| Mother | 806 (96%) | 447 (96%) | 359 (96%) | 0.77b |

| Father | 34 (4%) | 18 (4%) | 16 (4%) | |

| Caregiver Ethnicity | <0.001b | |||

| Hispanic | 417 (50%) | 194 (42%) | 223 (60%) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 152 (18%) | 106 (23%) | 46 (12%) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 236 (28%) | 140 (30%) | 96 (25%) | |

| Other | 37 (4%) | 25 (5%) | 12 (3%) | |

| Caregiver Education | <0.001b | |||

| Less than High School | 218 (26%) | 80 (17%) | 138 (37%) | |

| High School graduate | 277 (33%) | 145 (31%) | 132 (35%) | |

| Partial College | 196 (23%) | 130 (28%) | 66 (18%) | |

| College or Higher | 151 (18%) | 110 (24%) | 41 (11%) | |

| Household Income N=812 | <0.001b | |||

| Less than $10,000 | 259 (32%) | 104 (23%) | 155 (43%) | |

| $10,000-19,999 | 223 (27%) | 118 (26%) | 105 (29%) | |

| $20,000-39,999 | 200 (25%) | 117 (26%) | 83 (23%) | |

| $40,000 or more | 130 (16%) | 109 (24%) | 21 (6%) | |

| WIC enrollment (% yes) | 714 (85%) | 361 (78%) | 353 (94%) | <0.001b |

| Study Site | 0.004b | |||

| Miami, FL | 141 (17%) | 68 (15%) | 73 (16%) | |

| Chapel Hill, NC | 250 (30%) | 161 (35%) | 89 (24%) | |

| Nashville, TN | 224 (27%) | 113 (26%) | 111 (28%) | |

| New York, NY | 227 (27%) | 123 (24%) | 104 (29%) |

T-test

Pearson Chi-square test

In bivariate analysis, food insecurity was strongly associated with financial resources; those with a household income less than $10,000/year had the highest prevalence of food insecurity with 43% of such families identifying as food insecure (p-value <0.001). The prevalence of food insecurity was also higher among those of Hispanic ethnicity, 60%, compared with those self-identified as Black, White, or other race, 25%, 12%, and 3% respectively (p-vale <0.001). More food-insecure caregivers had not completed high school (37%) when compared to those who were food-secure (17%) (Overall p-value for food insecurity by education <0.001).

Unadjusted association between food security status and individual items from the infant feeding questionnaire is shown Table 2. Fewer food insecure caregivers reported exclusive breast-feeding at the time of discharge from the hospital (43% vs. 35%) as shown in Table 3; however, this difference was not statistically significant. No difference was noted in volume of formula fed to infant between food secure and food insecure caregivers. No difference between the two groups was observed in percent of caregivers who reported feeding their child any breast milk (54% for food secure vs 56% for food insecure).

Table 2.

Infant Feeding Practices and Beliefs by Household Food Insecurity

| Characteristics | Overall (n=842) |

Food Secure (n =465) |

Food Insecure (n=377) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restrictive | ||||

| Amount (Behaviors) | ||||

| I carefully control how much my child eats | 0.09a | |||

| Never | 121 (14%) | 78 (17%) | 43 (11%) | |

| Seldom or infrequently | 52 (6%) | 33 (7%) | 19 (5%) | |

| Half of the time | 57 (7%) | 32 (7%) | 25 (7%) | |

| Most of the time | 159 (19%) | 88 (19%) | 71 (19%) | |

| Always | 453 (54%) | 234 (50%) | 219 (58%) | |

| I am very careful not to feed my child too much | 0.27a | |||

| Never | 101 (12%) | 64 (14%) | 37 (10%) | |

| Seldom or infrequently | 50 (6%) | 29 (6%) | 21 (6%) | |

| Half of the time | 43 (5%) | 19 (4%) | 24 (6%) | |

| Most of the time | 142 (17%) | 78 (17%) | 64 (17%) | |

| Always | 506 (60%) | 275 (59%) | 231 (61%) | |

| Responsive | ||||

| Satiety (Behavior) | ||||

| My child lets me know when s/he is full | 0.61a | |||

| Never | 19 (2%) | 13 (3%) | 6 (2%) | |

| Seldom or infrequently | 23 (3%) | 12 (3%) | 11 (3%) | |

| Half of the time | 35 (4%) | 17 (4%) | 18 (5%) | |

| Most of the time | 125 (15%) | 65 (14%) | 60 (16%) | |

| Always | 640 (76%) | 358 (77%) | 282 (75%) | |

| My child lets me know when she is hungry | 0.54a | |||

| Never | 6 (1%) | 2 (0%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Seldom or infrequently | 10 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 5 (1%) | |

| Half of the time | 16 (2%) | 10 (2%) | 6 (2%) | |

| Most of the time | 112 (13%) | 56 (12%) | 56 (14%) | |

| Always | 698 (83%) | 392 (84%) | 306 (81%) | |

| I let my child decide how much to eat | 0.74a | |||

| Never | 181 (22%) | 107 (23%) | 74 (20%) | |

| Seldom or infrequently | 61 (7%) | 32 (7%) | 29 (8%) | |

| Half of the time | 69 (8%) | 35 (8%) | 34 (9%) | |

| Most of the time | 136 (16%) | 73 (16%) | 63 (17%) | |

| Always | 395 (47%) | 218 (47%) | 177 (47%) | |

| I pay attention when my baby seems to be telling me he/she is full or hungry | 0.30a | |||

| Never | 2 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) | |

| Seldom or infrequently | 2 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Half of the time | 13 (2%) | 5 (1%) | 8 (2%) | |

| Most of the time | 64 (8%) | 32 (7%) | 32 (8%) | |

| Always | 761 (90%) | 427 (92%) | 334 (89%) | |

| Pressuring | ||||

| Finishing (Behavior) | ||||

| I try to get my child to finish her breast milk or formula | 0.05a | |||

| Never | 209 (25%) | 130 (28%) | 79 (21%) | |

| Seldom or infrequently | 102 (12%) | 62 (13%) | 40 (11%) | |

| Half of the time | 73 (9%) | 41 (9%) | 32 (8%) | |

| Most of the time | 140 (17%) | 69 (15%) | 71 (19%) | |

| Always | 318 (38%) | 163 (35%) | 155 (41%) | |

| Finishing (Beliefs) | ||||

| It is important an infant finish all of the milk in his or her bottle | 0.05 | |||

| Disagree | 300(36%) | 184 (40%) | 116 (31%) | |

| Slightly Disagree | 99 (12%) | 55 (12%) | 44 (12%) | |

| Neutral | 121 (14%) | 67 (15% | 54 (14%) | |

| Slightly Agree | 127 (15%) | 65 (14%) | 62 (17%) | |

| Agree | 188 (23%) | 90 (20%) | 98 (26%) | |

| Soothing (Behavior) | ||||

| When my baby cries, I immediately feed him/her | 0.003a | |||

| Never | 203 (24%) | 131 (28%) | 72 (19%) | |

| Seldom or infrequently | 169 (20%) | 96 (21%) | 73 (19%) | |

| Half of the time | 181 (22%) | 103 (22%) | 78 (21%) | |

| Most of the time | 116 (14%) | 58 (12%) | 58 (15%) | |

| Always | 172 (20%) | 77 (17%) | 95 (25%) | |

| Soothing (Belief) | ||||

| The best way to make an infant stop crying is to feed him/her | <0.001 | |||

| Disagree | 447 (53%) | 276 (59%) | 171 (45%) | |

| Slightly disagree | 109 (13%) | 61 (13%) | 48 (13%) | |

| Neutral | 90 (11%) | 46 (10% | 44 (12%) | |

| Slightly Agree | 110 (13%) | 50 (11%) | 60 (16%) | |

| Agree | 86 (10%) | 32 (7%) | 54 (14%) | |

| Cereal (Behavior) | ||||

| I give my baby cereal in the bottle, N=826 | 0.92a | |||

| Never | 734 (89%) | 408 (89%) | 326 (89%) | |

| Seldom or infrequently | 53 (6%) | 31 (7%) | 22 (6%) | |

| Half of the time | 15 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 8 (2%) | |

| Most of the time | 6 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) | |

| Always | 18 (2%) | 9 (2%) | 9(2%) | |

| Cereal (Belief) | ||||

| Cereal in the bottle helps infants sleep through the night, N=840 | 0.61a | |||

| Disagree | 390 (46%) | 214 (46%) | 176 (47%) | |

| Slightly disagree | 47 (6%) | 26 (6%) | 21 (6%) | |

| Neutral | 212 (25%) | 112 (24%) | 100 (27%) | |

| Slightly Agree | 72 (9%) | 46 (10%) | 26 (7%) | |

| Agree | 119 (14%) | 66 (14%) | 53 (14%) | |

| Always | 69 (8%) | 33 (7%) | 36 (10%) | |

| Laissez-Faire | ||||

| Attention (Behaviors) | ||||

| I watch TV while feeding | 0.51a | |||

| Never | 208 (25%) | 115 (25% | 93 (25% | |

| Seldom or infrequently | 248 (29%) | 134 (29%) | 114 (30%) | |

| Half of the time | 217 (26% | 129 (28% | 88 (23%) | |

| Most of the time | 100 (12%) | 54 (12%) | 46 (12% | |

| Always | 69 (8%) | 33 (7%) | 36 (10%) | |

| When my child has a bottle, I prop it up, N=817 | 0.09a | |||

| Never | 626 (77%) | 351 (78%) | 275(76%) | |

| Seldom or infrequently | 101 (12%) | 55 (12%) | 46 (13%) | |

| Half of the time | 37 (5%) | 18 (4%) | 19 (5%) | |

| Most of the time | 24 (3%) | 18 (4%) | 6 (2%) | |

| Attention (Beliefs) | ||||

| I think it is ok to prop an infant's bottle to hold it in place, N=840 | 0.26a | |||

| Disagree | 616 (73%) | 349 (75%) | 267 (71%) | |

| Slight Disagree | 50 (6%) | 29 (6%) | 21 (6%) | |

| Neutral | 49 (6%) | 27 (6%) | 22 (6%) | |

| Slightly Agree | 62 (7%) | 26 (6%) | 36 (10%) | |

| Agree | 63 (8%) | 33 (7% | 30 (8%) | |

Pearson Chi-square test

Table 3.

Infant Feeding Behaviors at Discharge and 2 months of Age by Household Food Security Status.

| Characteristics | Combined (n= 842) |

Food Secure (n = 465) |

Food Insecure (n = 377) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant feeding at time of hospital discharge | ||||

| Breast milk only (%) | 40 | 43 | 35 | 0.05a |

| Formula only | 22 | 22 | 23 | |

| Both breast milk and formula | 38 | 35 | 42 | |

| Infant feeding at 2 months, % any breast milk | 55% | 54% | 56% | 0.60a |

| Volume of formula fed each feed at 2 months (oz.) | 4 (1.3) | 4 (1.3) | 3.9(1.3) | 0.18 b |

| Early Solid food introduction , % yes | 6.7 % | 7.5 % | 5.8 | 0.33 a |

Pearson Chi-Square test

student t-test

The results of the multivariate analysis between feeding beliefs and behaviors with food insecurity are shown in Table 4. Food insecure households had increased odds of agreeing with immediately feeding a baby when s/he cries (OR 1.40; 95% CI: 1.06-1.83). Food insecure households also had increased odds of believing that the best way to stop an infant from crying is by feeding (OR 1.72 95%CI: 1.28-2.29). Food insecure caregivers less frequently endorsed paying attention when their baby seems to be telling them s/he is full or hungry (OR 0.57 95%CI: 0.34-0.96).

Table 4.

Unadjusted and Adjusted POLR Odds Rations and 95% CI of Infant Feeding Practices and Beliefs by Household Food Security Status

| Parental Feeding Behaviors and/or Belief | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OP (95% CI)_ |

|---|---|---|

| Restrictive Behaviors | ||

| Amount (Behaviors) | ||

| I carefully control how much my child eats | 1.41 (1.10, 1.84) | 1.15 (0.86, 1.54) |

| I am very careful not to feed my child too much | 1.14 (0.87, 1.49) | 0.87 (0.65, 1.17) |

| Responsive | ||

| Satiety (Behavior) | ||

| My child lets me know when s/he is full | 0.90 (0.65, 1.24) | 0.81 (0.58, 1.16) |

| My child lets me know when she is hungry | 0.81 (0.56, 1.15) | 0.73 (0.49, 1.09) |

| I let my child decide how much to eat | 1.06 (0.82, 1.36) | 1.15 (0.87, 1.52) |

| I pay attention when my baby seems to be telling me he/she is full or hungry | 0.68 (0.43, 1.08) | 0.57 (0.34, 0.96) |

| Pressuring | ||

| Finishing (Behavior) | ||

| I try to get my child to finish her breast milk or formula | 1.4 (1.10, 1.80) | 1.01 (0.77 1.33) |

| Finishing (Belief) | ||

| It’s important that an infant finish all of the milk in his or her bottle | 1.47 (1.14, 1.87) | 1.04 (0.80, 1.38) |

| Soothing (Behavior) | ||

| When my baby cries, I immediately feed him/her | 1.62 (1.27, 2.07) | 1.40 (1.06, 1.83) |

| Soothing (Belief) | ||

| The best way to make an infant stop crying is to feed him/her | 1.86 (1.43, 2.40) | 1.72 (1.28, 2.29) |

| Cereal (Behavior) | ||

| I give my baby cereal in the bottle, | 1.06 (0.69, 1.64) | 1.26 (0.77, 2.1) |

| Cereal (Belief) | ||

| Cereal in the bottle helps infants sleep through the night | 0.95 (0.73, 1.21) | 0.97 (0.73, 1.28) |

| Finishing (Belief) | ||

| Laissez-Faire | ||

| Attention (Beliefs) | ||

| I think it is ok to prop an infant's bottle to hold it in place, | 1.26 (0.91, 1.70) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.97) |

| Attention (Feeding Behaviors) | ||

| I watch TV while feeding | 1.02 (0.81, 1.31) | 1.14 (0.87, 1.49) |

| When my child has a bottle, I prop it up, | 1.12 (0.81, 1.55) | 1.06 (0.74, 1.52 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio

Proportional Odds ordinal Logistic Regression

Adjusted for patient sex, WIC status, no. children in home, caregiver race/ethnicity, caregiver education, household income, and study site

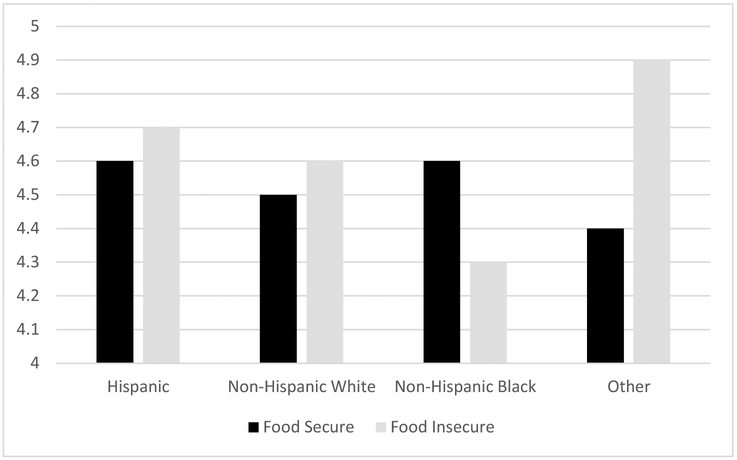

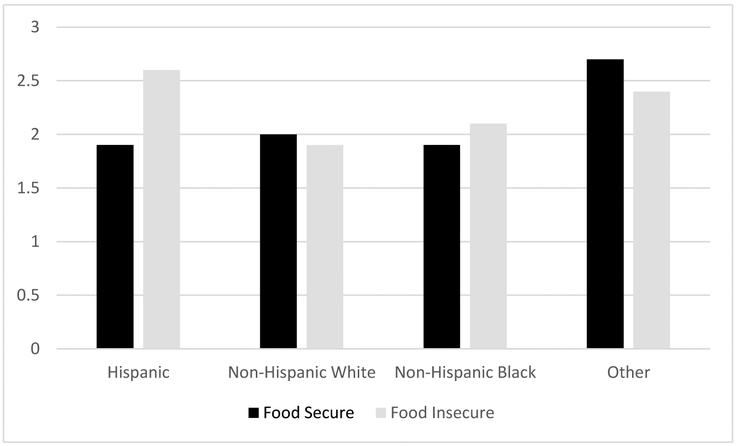

Finally, differential associations were found in the relationships between infant feeding practices and food insecurity by race/ethnicity (Figure 1a and 1b). Response to the question “My child lets me know she s/he is full” varied by race/ethnicity and food insecurity status (Figure 1a, global p-interaction=0.03). The difference observed between food secure non-Hispanic Black and food insecure non-Hispanic Black caregivers was 4.6 and 4.4, respectively and the difference was statistically significant (p=0.04). The differences observed among Hispanic, non-Hispanic whites and those who identified as Other was not statistically significant. Response to the question “The best way to make an infant stop crying is to feed her/him” varied by race/ethnicity and food security status (Figure 1b, p-value for interaction 0.01). The difference observed among Hispanic caregivers by food security status was statistically significant (p <0.001).

Figure 1a.

Agreement with My Child Lets me Know when s/he is Full by Race/Ethnicity and Food Security Status

Figure 2.

Agreement with belief the best way to stop an infant from crying is to feed him/her by Race/Ethnicity and Food Security Status

There were no statistically significant differences in weight-for-length z-score at two months for the children enrolled by food insecurity status.

DISCUSSION

Our study found differences in feeding practices and beliefs between food-secure and food-insecure households. Families from food-insecure homes had increased odds of immediately feeding their child when s/he cried. Food-insecure caregivers also had increased odds of believing the best way to stop an infant from crying is to immediately feed her/him. Food insecure households had decreased odds of endorsing paying attention when the child seems to be telling the caregiver that he/she is hungry. No differences between food-insecure and food-secure households were observed in odds of encouraging their child to finish their milk or formula or believing that it is important that a child finish all the milk or formula. Differences between feeding beliefs and practices were also seen based on race/ethnicity: Food insecure non-Hispanic Black caregivers reported less agreement with their child letting the caregiver know when s/he is full compared to food secure non-Hispanic black caregivers. Food-insecure Hispanic families were more likely to agree the best way to stop an infant from crying is to feed her/him compared to food secure Hispanic caregivers. Additionally, food-insecure Hispanic families are more likely to endorse immediately feeding their child when s/he cries relative to non-Hispanic food insecure households.

During early infancy, children living in food-insecure homes may be exposed to infant-feeding practices that compound the negative effects of a nutritionally deprived environment, such as diluting formula31. Caregivers who are concerned about their family’s food supply appear more likely to employ infant-feeding practices that are unique to their stressed environment. This study adds to a growing body of evidence that describes the relationship between food insecurity and feeding practices in caregivers of very young infants22. In one study, Hispanic mothers who were food-insecure were found to have more controlling feeding styles and, thus, were more likely to pressure their infants to eat when they were not hungry22. Because of the geographic and ethnic diversity of our sample, our study adds to these findings an appreciation for differential expression of infant-feeding behaviors in Hispanic and non-Hispanic families, as well as an understanding of the influence of family health beliefs.

In this study, we found that food insecure caregivers had increased odds of endorsing strong affirmation of the belief that feeding was the best way to make an infant stop crying. This result suggests that caregivers affected by food insecurity may place higher value in food’s ability to relieve any perceived discomfort regardless of hunger cues from the infant. Within the context of limited financial means to maintain a reliable source of food, these specific beliefs make intuitive sense. Another hypothesis is that the lack of a sense of control, inherent to having an unreliable source of food, may prompt caregivers to use pressuring behaviors during infant feeding. The research into using food to soothe is sparse but suggests that this behavior is related to maternal self-efficacy and maternal rating of their child’s negative temperament19.

Although early solid food introduction is known to be associated with increased odds of obesity in childhood32, we did not find any evidence of a relationship between food insecurity and early solid food introduction in our study sample. Likewise, we did not find any differences in the amount of formula fed to infants who are bottle-fed. These findings are notable, particularly when considering that food-insecure caregivers in this sample showed increased odds of using food to soothe.

The coping mechanisms that caregivers employ to manage the stress of food insecurity may be predicated by their socio-cultural contexts. Our findings are consistent with other work which demonstrated differences in feeding practices by race/ethnicity of infants27 as well as preschool age children33. This study highlights the importance of understanding how a family’s culture influences feeding strategies during times of food insecurity and its impact on health.

There are limitations to this study. With a cross-sectional design, this study cannot make any inference on the direct influence of these caregiver behaviors during child infancy on the incidence of heavier weight status in toddlerhood. Further, although surveys were completed under conditions of privacy, food-insecure caregivers may have been influenced by social desirability to under-report food insecurity or over-report behaviors they may perceive as positive, limiting the quality of data gathered. Our analysis of early food introduction is also limited because we only analyzed 2-month data. Our study does not explore the differences in caregiver feeding behaviors and beliefs by acculturation and food security; however, this would be an interesting future study. Prior work from the Greenlight has explored the association between feeding behaviors and acculturation among a Latino population34.

Our analytical approach carries the risk of spurious associations due to multiple testing. The questions included in this analysis were selected from a validated tool (IFSQ)based on clinical relevance and importance to the main outcome of the umbrella study; however , we did not use the whole scale or even complete subscales for specific feeding styles due to concern of respondent burden from the overall study measures An additional study limitation is the use of the IFSQ in children younger than 3 months. The use of individual IFSQ questions and in samples younger than 3 months age has been previously reported27.

We did not analyze caregiver perception of child temperament within the context of food insecurity for this study so this influence needs further evaluation. Finally, caregivers may have been prone to under- or over-report the exact amounts of formula consumed by their infants, instead reporting approximate amounts based on the quantity of milk that was prepared.

While the prevalence of food insecurity has decreased since the 2008 recession, a large number of children are still affected by food insecurity2. More pediatricians are becoming aware of the childhood food insecurity35, and the American Academy of Pediatrics recently issued a policy statement advocating for the promotion of food security as a modifiable social determinant of life-course health1. Some have advocated that screening for food insecurity may be appropriate among vulnerable populations28. Our findings help provide better context for providing culturally-sensitive, anticipatory guidance about feeding practices to the families of infants and young children. For child advocates and public health leaders – including regional and national directors of the agencies that administer the WIC and SNAP programs -- this understanding can help frame community-based solutions to the twin public-health problems of food insecurity and obesity.

CONCLUSION

During early infancy, feeding practices and beliefs different among caregivers by household food security status. Further research is needed to examine whether these practices are associated with increased risk of obesity and obesity-related morbidity in food insecure households. Future studies should also focus on how health impact of food insecurity differ by a child’s race/ethnicity.

What’s New:

This study examines how caregivers living in households affected by food insecurity feed their infants. Several feeding practices, including the use of food to soothe differ by food insecurity and, in some cases, vary by ethnicity.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source Acknowledgement: Dr. Ben-Davies and Dr. Orr were funded by a postdoctoral fellowship grant from the National Research Service Award T32-14001-24 and supported by UNC CTSA grant U54 RR023499. The Greenlight Study is funded by a National Institute of Health grant R01 HD059794. The funding source did not have a role in study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Clinical Trial Registration: This trial has been registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01040897)

References

- 1.Council On Community P, Committee On N. Promoting Food Security for All Children. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1431–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alisha Coleman-Jensen MPR, Christian A. Gregory Anita Singh. Household Food Security in the United States in 2015. In: Agriculture USDo, ed. www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err215.aspx Economic Research Service; 2016:44. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eicher-Miller HA, Mason AC, Weaver CM, McCabe GP, Boushey CJ. Food insecurity is associated with iron deficiency anemia in US adolescents. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2009;90(5):1358–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park K, Kersey M, Geppert J, Story M, Cutts D, Himes JH. Household food insecurity is a risk factor for iron-deficiency anaemia in a multi-ethnic, low-income sample of infants and toddlers. Public health nutrition. 2009;12(11):2120–2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo EA Jr., Food insufficiency and American school-aged children's cognitive, academic, and psychosocial development. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jyoti DF, Frongillo EA, Jones SJ. Food insecurity affects school children's academic performance, weight gain, and social skills. J Nutr. 2005;135(12):2831–2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shankar P, Chung R, Frank DA. Association of Food Insecurity with Children's Behavioral, Emotional, and Academic Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2017;38(2):135–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose-Jacobs R, Black MM, Casey PH, et al. Household food insecurity: associations with at-risk infant and toddler development. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casey PH, Simpson PM, Gossett JM, et al. The association of child and household food insecurity with childhood overweight status. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):e1406–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larson NI, Story MT. Food insecurity and weight status among U.S. children and families: a review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(2):166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metallinos-Katsaras E, Must A, Gorman K. A longitudinal study of food insecurity on obesity in preschool children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(12):1949–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trapp CM, Burke G, Gorin AA, et al. The relationship between dietary patterns, body mass index percentile, and household food security in young urban children. Childhood obesity (Print). 2015;11(2):148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruening M, MacLehose R, Loth K, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Feeding a family in a recession: food insecurity among Minnesota parents. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(3):520–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dietz WH. Does hunger cause obesity? Pediatrics. 1995;95(5):766–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spruijt-Metz D, Li C, Cohen E, Birch L, Goran M. Longitudinal influence of mother's child-feeding practices on adiposity in children. J Pediatr. 2006;148(3):314–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saiz AM Jr., Aul AM, Malecki KM, et al. Food insecurity and cardiovascular health: Findings from a statewide population health survey in Wisconsin. Prev Med. 2016;93:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faith MS, Heshka S, Keller KL, et al. Maternal-child feeding patterns and child body weight: findings from a population-based sample. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(9):926–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faith MS, Scanlon KS, Birch LL, Francis LA, Sherry B. Parent-child feeding strategies and their relationships to child eating and weight status. Obes Res. 2004;12(11):1711–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stifter CA, Anzman-Frasca S, Birch LL, Voegtline K. Parent use of food to soothe infant/toddler distress and child weight status. An exploratory study. Appetite. 2011;57(3):693–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, McIntosh WA. Children's weight status and maternal and paternal feeding practices. J Child Health Care. 2011;15(4):389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murashima M, Hoerr SL, Hughes SO, Kattelmann KK, Phillips BW. Maternal parenting behaviors during childhood relate to weight status and fruit and vegetable intake of college students. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(6):556–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross RS, Mendelsohn AL, Fierman AH, Racine AD, Messito MJ. Food insecurity and obesogenic maternal infant feeding styles and practices in low-income families. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2):254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feinberg E, Kavanagh PL, Young RL, Prudent N. Food insecurity and compensatory feeding practices among urban black families. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):e854–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L, Collins C, Ratliff M, Xie B, Wang Y. Breastfeeding Reduces Childhood Obesity Risks. Childhood obesity (Print). 2017;13(3):197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun C, Foskey RJ, Allen KJ, et al. The Impact of Timing of Introduction of Solids on Infant Body Mass Index. J Pediatr. 2016;179:104–110 e101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders LM, Perrin EM, Yin HS, Bronaugh A, Rothman RL, Greenlight Study T. "Greenlight study": a controlled trial of low-literacy, early childhood obesity prevention. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1724–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perrin EM, Rothman RL, Sanders LM, et al. Racial and ethnic differences associated with feeding- and activity-related behaviors in infants. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):e857–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):e26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson AL, Mendez MA, Borja JB, Adair LS, Zimmer CR, Bentley ME. Development and validation of the Infant Feeding Style Questionnaire. Appetite. 2009;53(2):210–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taveras EM, Blackburn K, Gillman MW, et al. First steps for mommy and me: a pilot intervention to improve nutrition and physical activity behaviors of postpartum mothers and their infants. Maternal and child health journal. 2011;15(8):1217–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burkhardt MC, Beck AF, Kahn RS, Klein MD. Are our babies hungry? Food insecurity among infants in urban clinics. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51(3):238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huh SY, Rifas-Shiman SL, Taveras EM, Oken E, Gillman MW. Timing of solid food introduction and risk of obesity in preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):e544–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans A, Seth JG, Smith S, et al. Parental feeding practices and concerns related to child underweight, picky eating, and using food to calm differ according to ethnicity/race, acculturation, and income. Maternal and child health journal. 2011;15(7):899–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dancel LD, Perrin E, Yin SH, et al. The relationship between acculturation and infant feeding styles in a Latino population. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2015;23(4):840–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Malley JA, Peltier CB, Klein MD. Obese and hungry in the suburbs: the hidden faces of food insecurity. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(3):163–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]